Abstract

Objectives:

Immunization programs in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) are faced with an ever-growing number of vaccines of public health importance recommended by the World Health Organization, while also financing a greater proportion of the program through domestic resources. More than ever, national immunization programs must be equipped to contextualize global guidance and make choices that are best suited to their setting. The CAPACITI decision-support tool has been developed in collaboration with national immunization program decision makers in LMICs to structure and document an evidence-based, context-specific process for prioritizing or selecting among multiple vaccination products, services, or strategies.

Methods:

The CAPACITI decision-support tool is based on multi-criteria decision analysis, as a structured way to incorporate multiple sources of evidence and stakeholder perspectives. The tool has been developed iteratively in consultation with 12 countries across Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

Results:

The tool is flexible to existing country processes and can follow any type of multi-criteria decision analysis or a hybrid approach. It is structured into 5 sections: decision question, criteria for decision making, evidence assessment, appraisal, and recommendation. The Excel-based tool guides the user through the steps and document discussions in a transparent manner, with an emphasis on stakeholder engagement and country ownership.

Conclusions:

Pilot countries valued the CAPACITI decision-support tool as a means to consider multiple criteria and stakeholder perspectives and to evaluate trade-offs and the impact of data quality. With use, it is expected that LMICs will tailor steps to their context and streamline the tool for decision making.

Keywords: decision-support, HTA, immunization, LMIC, MCDA, priority setting, vaccine

Introduction

Achieving the goals set out in the 2012 United Nations resolution on universal health coverage will require countries to set context-specific priorities through an explicit, transparent, and accountable process.1 Traditionally, decisions on the introduction of new vaccines in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs) have been guided by global recommendations and facilitated by global financing and supply agencies.2 Nevertheless, as more countries transition toward domestic financing of immunization programs and as the range of available vaccines and vaccine products grows, it is increasingly important to strengthen the capacity of national immunization programs to contextualize global guidance as they choose among vaccination products, services, and strategies.

The World Health Organization (WHO) 3D approach to priority setting outlines 3 components for evidence-informed decision making: data (information, analysis, and criteria for decisions), dialog (stakeholder participation and engagement in the recommendation process), and decision (organizational structures, governance, and legal frameworks).3 In the Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) report on good practices in health technology assessment (HTA), the data component of the 3D approach is concerned with evidence synthesis, whereas dialog is concerned with evidence-based decision making, requiring contextualization and deliberation of a broad range of considerations, including affordability, feasibility, and socio-ethical factors.4

The previous decade has seen considerable progress toward improving immunization decision-making capacity in LMICs on the data and decision components of the 3D approach. In many countries, national immunization technical advisory groups (NITAGs) have been established as independent advisory bodies to the immunization program, and an increasing number of tools and information databases are available to support evidence collection and synthesis.5 Nevertheless, many countries lack a strong, legitimate process for structured dialog and interpretation of evidence to compare among multiple interventions.4,6,7

This article describes the development of the CAPACITI decision-support tool as a means to explicitly structure and document the process for prioritizing across vaccination products, services, or strategies. We describe how the structure of the tool has been informed by best practice in the fields of HTA and multi-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) and how the tool balances best practice with practicality and how this has been informed by country pilots.

Purpose and Scope of the CAPACITI Decision-Support Tool

The decision-support tool structures and documents an evidence-based, context-specific process for prioritizing or selecting among multiple vaccination products, services, or strategies.8 The target audience is the immunization program or advisory bodies in LMICs, to address decisions devolved to the immunization program by the Ministry of Health.

Similar to the GRADE Evidence to Recommendation (EtR) framework, the decision-support tool supports panels to use evidence in a structured and transparent way to inform decisions.9 Nevertheless, the GRADE EtR framework is designed to evaluate a single intervention in relation to a comparator, whereas the CAPACITI decision-support tool is designed for choices among multiple options (Table 1). Accordingly, the decision-support tool is based on MCDA, as a structured way to incorporate different types of evidence (such as clinical trial data, economic analysis, and expert opinion) and stakeholder perspectives (eg, clinicians, budget holders, logisticians, and disease program managers). Most relevant for immunization programs, MCDA can incorporate criteria which cannot be fully measured, such as alignment of a proposed new vaccine,services,or strategies with the existing immunization program or ease of administration, alongside measurable considerations, such as reduction in morbidity.10

Table 1.

A comparison between the types of policy questions addressed by the GRADE EtR framework and those addressed by the CAPACITI decision-support framework.

| Example of policy questions addressed by GRADE EtR framework | Example of policy questions addressed by CAPACITI decision-support framework | |

|---|---|---|

| New vaccine introduction | ||

| 1 | Should rotavirus vaccination be introduced into the NIP? | Which new vaccine(s) should be prioritized for introduction into the NIP (eg, comparison between HPV, PCV, rotavirus vaccines)? |

| Vaccine product procurement | ||

| 2 | Should the immunization program switch procurement from the quadrivalent HPV vaccine to the nine-valent HPV vaccine? | Which of the available HPV vaccine products should be procured for the NIP? |

| Vaccine delivery strategy | ||

| 3 | Should hepatitis B birth dose be delivered under CTC conditions? | Under which scenarios should CTC delivery be recommended for birth dose hepatitis B vaccination? |

CTC indicates controlled temperature chain; EtR, Evidence to Recommendation; HPV, human papillomavirus; NIP, national immunization program; PCV, pneumococcal conjugate vaccine.

The CAPACITI decision-support tool is oriented toward national advisory and decision-making bodies in LMICs, with a practical, stepwise, Excel-based tool that explicitly outlines mechanisms for stakeholder involvement, allows consideration of operational and social/political aspects (including guidance to incorporate expert opinion), and transparently documents the recommendation process. Typically, the recommendation process using the CAPACITI decision-support tool would be expected to take around 6 months, but timelines are highly dependent on country context and complexity of the decision question. The full process could foreseeably be condensed to 1 week for urgent decisions or may take more than a year for complex decisions. The main determinants of time are data collection and analysis requirements, personnel availability, and number of in-person meetings. It is expected that countries using the tool for the first time and those with weaker priority-setting infrastructure may take longer to complete the process, because many of the steps will be completed de novo.

Development of the CAPACITI Decision-Support Tool

The CAPACITI decision-support tool and the underlying methodology have been developed through an iterative approach from 2018 to 2020, in consultation with 13 countries across the WHO regions of Africa, the Americas, Southeast Asia, and the Western Pacific and technical agencies and advisory committees to WHO.6 Table 2 lists the countries involved and the pilot topics examined using the CAPACITI tool. This section summarizes iterations of the tool and lessons learned, before presenting a description of the final tool in the results.

Table 2.

An overview of iterations in the development of the CAPACITI decision-support framework.

| Version of the decision-support framework | Version 2018 | Version 2019 | Version 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | Selection of rotavirus vaccine products | Prioritization of 2–5 immunization interventions | Prioritization of 2–5 immunization interventions |

| Output | Ranking of vaccines at national and subnational level | Document process and rationale for final recommendation | Document process and rationale for final recommendation |

| Elements set by the framework | Quantitative MCDA, criteria, data inputs, scoring scales | Quantitative MCDA, 0–10 range for scoring scale, separation of cost and non-cost criteria | Minimal elements set by the framework, with flexibility for the user to choose which steps are important for their recommendation |

| Elements set by the user | Weights, groups for equity analysis | Stakeholders, options, criteria, weights, scoring scale definition, outcome measures, and data sources | Stakeholders, options, type of MCDA, criteria, weights (if relevant), scoring scale and/or rules to interpret evidence (if relevant), outcome measures, and data sources |

| Countries providing input (WHO country office, NITAG, NIP, and/or technical agency) | Indonesia, Thailand | Mali (full pilot), Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Indonesia, Nigeria |

Indonesia (full pilot—ongoing), Cuba, Ethiopia (pilot ongoing), Nigeria, Vietnam, Zambia |

MCDA indicates multi-criteria decision analysis; NIP, national immunization program; NITAG, national immunization technical advisory group; WHO, World Health Organization.

Version 2018: quantitative MCDA model for evidence assessment with fixed criteria

In response to calls to look beyond the traditional measures of efficacy and cost-effectiveness,11 an Excel tool was developed to analyze vaccine products across 5 criteria determined through global consultations (health impact, coverage and equity, safety, delivery cost, procurement cost), incorporate country-specific weights, and aggregate the output into a ranking of options.6 Piloting found that a greater emphasis was needed on the social aspects of MCDA—namely, stakeholder engagement and guiding discussions to interpret the output—and greater flexibility to incorporate country criteria and data. This is in line with a consensus development article on the use of MCDA in HTA, which underlines the importance of incorporating deliberation.12

Version 2019: tool for quantitative MCDA incorporating procedural aspects

A revised tool was developed based on the ISPOR best practice checklist for MCDA.13 The tool was developed through 2 in-person workshops: 1 workshop for criteria selection, followed by a period of evidence collection, and a second workshop for interpreting evidence to come to a recommendation. In this revised approach, the tool and accompanying Excel tool did not determine the output at any stage: country users defined the options, criteria, and evidence requirements. There is no minimum set of evidence requirements. The tool supports the committee to understand limitations in available evidence and whether better quality data would change the final recommendation (eg, a committee may lack data on acceptability, but determine that such data are unlikely to change their recommendation). Users attached weights to criteria and scores to options, using scales fixed to a 1 to 5 and a 0 to 10 absolute scale, respectively, because early testing suggested that more extensive scales gave the committee a false sense of precision. During the appraisal stage, aggregate scores for each option were calculated and presented graphically, and users adjusted weights or scores in real time to examine the implications of data uncertainty. In line with best practice,12 “cost” and “cost-effectiveness” criteria were excluded from the value measurement model and considered during a separate value for money step, which compared the total cost with the total (aggregate) score of each option.

This version was well received during orientation workshops in 8 African countries and was successfully piloted in Mali to support the NITAG recommendation on human papillomavirus (HPV) product choice. Nevertheless, there was concern around sustainability of using the tool and approach because many advisory bodies in LMICs are severely resource constrained, in terms of funding, secretariat function, and time. Moreover, the tool took a one-off approach, in which members of the committee, criteria, and evidence requirements are newly defined with each use. It was highlighted that this may become burdensome over a series of recommendations, and a one-off approach may lead to poor consistency and transparency in settings with weak governance.14

Many policy makers found it counterintuitive to separate cost from other criteria. It was also highlighted that, from an economic perspective, all constraints (including, for example, cold chain capacity and health worker time) should be separated along with budget. Policy makers requested greater flexibility in assigning scores, with the possibility of using more qualitative scores instead of the 0 to 10 scale mandated in the tool. Finally, while there was a greater focus on stakeholder engagement and discussion in this iteration, there was still a tendency to focus on total scores as opposed to evidence during appraisal.

Version 2020: tool for deliberative decision making

The current version of the CAPACITI decision-support tool (v2.0) incorporates elements of the Public Health England prioritization tool as a user-friendly tool to simply convey the concepts behind MCDA15; the evidence-informed deliberative processes as a sequential overview of procedural aspects for making recommendations16; the AGREE II instrument to ensure documentation of important aspects during the recommendation process17; and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline development methods, for specific guidance on evidence assessment.18 Because NITAGs are a potential end user, the tool seeks to align with the GRADE EtR tool, which is frequently used by NITAGs.

The tool has been reviewed by teams in Cuba, Indonesia, and Zambia and technical agencies supporting immunization priority setting. The Excel tool was circulated to focal points based on national immunization programs, NITAGs, or WHO country offices (5 countries) and WHO regional offices (Central Africa, the Americas, West Africa, Western Pacific) for beta testing (Table 2). Feedback was that the tool is very useful, especially for new vaccine introduction and product choice decisions, because it is responsive to country context and brings stakeholders together. Guidance to streamline the process will be important, and the tool should be provided alongside existing resources for interpreting evidence and data quality.

Structure of the CAPACITI Decision-Support Tool

The tool is based in Excel and structured into 5 sections: decision question, criteria for decision making, evidence assessment, appraisal, and recommendation (Table 3). The tool seeks to adhere to principles set out in the ISPOR reports on good practices in MCDA and HTA,4,13 while allowing flexibility to different decision-making processes within countries.

Table 3.

Steps in the CAPACITI decision-support framework.

| Step of the decision-support framework | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Decision question | |

| 1.1 Framing the objectives | Specifies the recommendation objectives, why a recommendation is needed, how it will be used and by whom |

| 1.2 Context | Describes the current situation in the country, relevant background, and potential implications of the recommendation |

| 1.3 Scope | Identifies possible options and uses quick procedures to shortlist 2–5 options to evaluate |

| 1.4 Participation | Maps important stakeholder perspectives and identifies mechanisms for participation |

| 1.5 Priority-setting process | Considers which MCDA approach to follow and the group techniques/discussion forums that will be used |

| 2. Criteria for decision making | |

| 2.1 Criteria | Documents the criteria and outcome measures by which to evaluate options |

| 2.2 Rules | Determines whether all criteria will be considered simultaneously, or whether certain criteria will be considered before/after others |

| 2.3 Weights | Assigns weights to each criterion to indicate their relative importance |

| 2.4 Scoring scale | Defines how options will be scored against each criterion. |

| 3. Evidence assessment | |

| 3.1 Evidence collection | Identifies and gathers available evidence |

| 3.2 Evidence statements | Provides a concise overview of available evidence and its limitations |

| 3.3 Performance matrix | Summarizes the performance of each option against each criterion, for simple comparison across options |

| 4. Appraisal | |

| 4.1 Comparison by criterion | Reviews how the options compare on a criterion-by-criterion basis |

| 4.2 Comparison across criteria | Examines which option(s) perform best across all criteria and the extent to which this may be affected by data quality |

| 5. Recommendation | |

| 5.1 Formulating the recommendation | Makes a preliminary recommendation and considers howto deal with data uncertainty |

| 5.2 Supplemental considerations | Considers any negative implications of the preliminary recommendation and how these could be addressed |

| 5.3 Final recommendation | Finalizes and rationalizes the recommendation |

| 5.4 Audit, monitoring, and evaluation | Considers how the recommendation will be monitored and evaluated, and howto improve the recommendation process |

| 5.5 Communication | Drafts the final report and describes the communication plan and appeal process |

Note. The framework outlines key considerations and questions under each step, but the fields in each step of the tool are left blank. Not all steps have to be completed. It is anticipated that certain steps will (and should) be prefilled at the country level to tailor to country context, streamline the process, and ensure consistency and accountability of recommendations.

MCDA indicates multi-criteria decision analysis.

Figure 1 summarizes the differences between each type of MCDA. All types of MCDA follow common steps to define the decision problem, select decision criteria, and assemble data to construct a performance matrix that compares, using selected criteria, among the options being evaluated.12 In qualitative MCDA, the committee deliberates on the performance matrix. Compared with using no explicit decision criteria, this improves the quality, consistency, and transparency of recommendations. In contrast, quantitative MCDA employs a value measurement model (using weighting and scoring) to interpret the performance matrix before deliberation, reducing cognitive burden on the committee and domination by vocal committee members, and improving consistency and transparency of recommendations. Nevertheless, it can be difficult to construct scales and capture opportunity costs, and the committee may overly focus on weights and scores, instead of the evidence.

Figure 1.

A summary of the key differences among quantitative, qualitative, and rule-based MCDAs.12 The CAPACITI decision-support framework (right side) allows the user to follow any of these 3 approaches or to follow a hybrid-based approach. Specific details are in the text.

MCDA indicates multi-criteria decision analysis.

In the tool, users can follow any of the 3 MCDA approaches or a hybrid-based approach. A strong focus of the tool and training materials is supporting countries to identify the MCDA and stakeholder engagement techniques that work best for their setting. The tool thereby covers a significant part of the decision-making continuum outlined by Ultsch et al.19 Over time, country users will tailor and prefill certain steps to streamline the tool for future use and to improve transparency and consistency of recommendations. For example, criteria, weights, and scoring scales may be preset for similar types of decision questions.

Decision question

The purpose of this step is to articulate the recommendation objectives and to outline how the recommendation process will be conducted. It is completed by focal points coordinating the recommendation process.

The step includes a review of the decision context and country-specific background to the question, before defining the scope of the recommendation by shortlisting between 2 and 8 options to compare. To ensure transparent documentation, any excluded options are noted with the reason. There is a maximum of 8 options because it can be challenging for a committee to keep track of performance across multiple criteria when comparing many options.

Next, the committee considers which stakeholders to engage. Policy bodies, their mandates, and guidelines vary across countries. Therefore, the focal points determine where the recommendation sits within the existing policy infrastructure and identifies how best to engage relevant stakeholders, whether through participation on the committee or other means. In line with Fung’s principles for effectively structured participation, it is advised to include stakeholders that will bring necessary expertise and knowledge, enhance legitimacy of the recommendation, or ensure ownership for successful implementation of the recommendation.20 The tool recommends including between 6 and 15 members for the recommendation committee, to ensure a sufficiently diverse range of perspectives, while also allowing all members to actively contribute to discussions, in order to foster shared understanding and ownership of the final recommendation.21

The final part of this step is to consider how the evidence appraisal will be structured. The focal points outline the approach to be followed and techniques to support committee deliberations, and develop a briefing document for the committee outlining the policy and program context to the decision question.

Criteria for decision making

The purpose of this step is to articulate how options will be compared and evaluated, according to local values and the decision question. This step is completed by the recommendation committee.

First, the committee selects the criteria that will form the basis for choosing or prioritizing among options. Although it is important to be comprehensive, it is recommended not to exceed 8 criteria, so that the committee can keep track of all criteria during discussions.14 To enhance legitimacy of the recommendation, it is encouraged to use a generic set of criteria, which are applicable across different decision questions, because this enhances consistency in decision making. Generic criteria can be supplemented by context-specific criteria, which depend on the specific options being compared. In many countries, the NITAG or HTA agency may already have defined generic criteria. If an established list of criteria exists, this step reviews whether the criteria are fit for purpose (eg, criteria developed for new vaccine introduction decisions may be less relevant for selecting between delivery strategies) and whether there are any question-specific modifications to the list (eg, valency is important when considering HPV vaccine product choice but less relevant for rotavirus vaccine product choice). If there is not an established list of criteria or if the list is not fit for purpose, the committee develops and comes to an agreement on criteria for the recommendation. Although a bottom-up approach, in which the criteria are selected according to the question, may be appropriate for single uses of the tool, it is recommended to establish country-specific generic criteria through a top-down approach based on the health sector strategic plan and national immunization strategy. Criteria are not preset, because piloting found that countries wish to select criteria themselves,6 but it is suggested to consider criteria across the domains of health impact, economic impact and sustainability, operational (programmatic and supply) and socio-ethical factors.8

The committee indicates whether certain criteria are more important than others by assigning weights. It is possible to weight all criteria equally. In qualitative MCDA, weights are not normally assigned. Nevertheless, weighting is encouraged in the decision-support tool so that the committee comes to an agreement on the relative importance of criteria, increasing transparency and streamlining the appraisal step.

The committee then sets out the scoring scale that will be used to assess the evidence across criteria on a common scale. Although scoring is normally only used for quantitative MCDA, this step is recommended in the decision-support tool to improve consistency in the committee’s interpretation of the evidence and to reduce bias in interpreting the evidence. In the Excel tool, the maximum scoring scale range is 10. The scale can either be numerical (eg, assigning scores between 0 and 5) or descriptive (eg, assigning “poor,” “average,” “good”). In countries with stronger analytical capabilities, it is important to consider how the value of quantitative criteria maps to the scoring scale, because some criteria have ratio properties and should not be mapped linearly.

Within this step, it is possible to define decision rules, either in the sense of rules-based MCDA, in which the priority order for criteria is defined, or to separate interdependent criteria and “constraints” for quantitative MCDA. Constraints are criteria reflecting fixed capacity, such as budget and cold chain space, and should not be combined with other criteria to calculate the aggregate score in quantitative MCDA. Because piloting found it counterintuitive to separate constraints from other criteria, the tool recommends that the committee set the weight of constraints to zero and state whether they will be considered before other criteria, to shortlist options, or after other criteria, to consider feasibility of top-ranking options during appraisal.

Evidence assessment

During this step, a technical team (which may comprise members of the committee in resource-constrained settings) collects, synthesizes, and assesses the quality of available evidence. Because there are many existing resources for collecting and analyzing data,6 the tool focuses on succinctly summarizing the main findings for the committee and reviewing confidence in the data. Across all types of evidence, it is recommended to consider risk of bias, quantity and consistency of results, applicability for the decision question and local context, and precision. This follows the principles set out in the GRADE system for assessing evidence quality,22 but allows comparison across different criteria (eg, to compare across clinical data, economic analyses, legal or ethical judgments, market data, and cold chain analyses). The team then completes a performance matrix, summarizing the main data points by criterion for each option, together with uncertainty bounds. It is essential that the performance matrix is complementary to, and does not replace, the summary of evidence.

Appraisal

In the appraisal step, the committee comes to a shared understanding of the evidence and its limitations, to jointly assess the advantages and disadvantages of each option. Contrary to standard MCDA practice, the tool first involves a comparison of options by criterion, to encourage a detailed review of the evidence. This ensures that committees following a quantitative MCDA approach do not overly focus on the total score and that all criteria are duly taken into consideration for a qualitative MCDA approach. The committee considers whether there are significant differences among the options for each criterion, the impact of data uncertainty on relative performance, and whether any option performs unacceptably poorly.

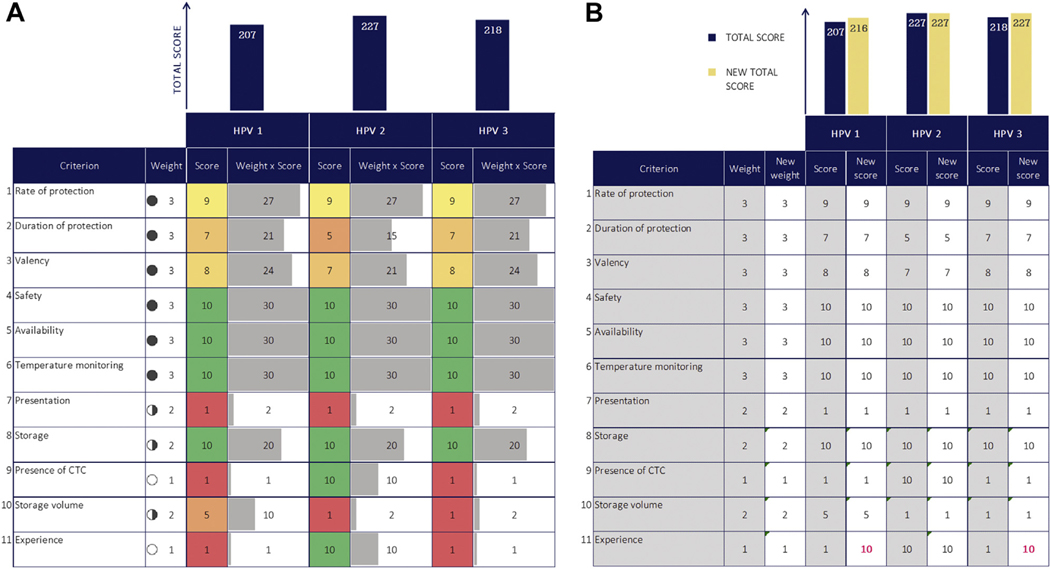

The committee then evaluates the performance of the options across all criteria and considers whether there are additional factors that may influence the recommendation (“contextualized criteria”). If using decision rules, the committee considers the criteria in the specified order. For quantitative MCDA, interactive graphics in the tool guide discussions and committee understanding of the factors influencing the total score (Fig. 2A,B). Although there is no mathematical constraints optimization step, the committee deals with constraints implicitly through their deliberations.

Figure 2.

(A) For quantitative MCDA, the tool produces a visual aid to guide committee discussion around factors driving the total scores. This figure is an illustrative example from a pilot country workshop to compare 3 HPV vaccine products. Workshop participants defined the criteria. Filled circles indicates weight (full circle is higher weight); gray horizontal bars, weighted score; green to red scale, higher scores are green and lower scores are red; navy vertical bars, total score. (B) For quantitative MCDA, there is also an interactive sheet in which the committee can view the effect of changing scores and weights on the final result, to support discussions around confidence to proceed with a recommendation and the impact of data uncertainty or disagreement on weights. This figure is an illustrative example from a pilot country workshop to compare 3 HPV vaccine products, in which the score for the “experience” criterion has been modified to examine the impact of missing data. Navy bars indicate original total score; yellow bars, new total score in the uncertainty analysis; pink text, scores that have been modified in the uncertainty analysis.

CTC indicates controlled temperature chain; HPV, human papillomavirus; MCDA, multi-criteria decision analysis.

Recommendation

The purpose of this step is to finalize and communicate the recommendation. After considering whether there is sufficient evidence quality to proceed with a recommendation, the committee comes to a consensus on the final recommendation and documents the rationale, noting any supplemental or research recommendations. Focal points specify the timing to next review the recommendation, steps to monitor impact of the recommendation (eg, to determine whether assumptions around health impact or coverage are realized), and evaluate the recommendation process itself. The final component of this step is drafting the final report and outlining the communication and appeal process.

Discussion

For implementation, it is essential to embed the CAPACITI decision-support tool within the existing decision-making architecture of countries. To strengthen capabilities across all components of the WHO 3D approach (data, dialog, decision), the decision-support tool should be implemented in tandem with other initiatives to build capacity for data analysis and evidence synthesis (moving toward the generation of country-specific reference cases),23 provision of training on facilitation techniques, and establishment of adequate legal capacity and accountability mechanisms. It is encouraged to implement the tool within a system for routine horizon scanning by public health agencies, such that there is foresight and planning of decision questions.

The tool provides guidance on MCDA approaches and stakeholder engagement techniques, but ultimately the implementation of the tool should be a learning process driven by national teams, who adapt the tool for their needs. The role of global and regional actors should be to provide technical support on functionality; countries themselves should choose the decision-making approach that works best for them.

As identified through piloting, the main value of the CAPACITI decision-support tool is in structuring dialog across stakeholders to come to a context-specific recommendation. Although several MCDA software tools exist, including PriorityVax for immunization, these tools are limited to a quantitative MCDA approach and tend to provide less support for deliberation and country-led contextualization—they allow adaptation of fixed stages but not the overall process.24,25 These tools are more appropriate in settings with strong processes for stakeholder engagement and deliberation; the CAPACITI decision-support tool supports other countries to build such processes.

Recent outbreaks, such as the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and other responses have brought to the forefront the increasingly complex decisions facing immunization programs. These include deciding which immunization services to continue, identifying strategies to deliver non–COVID-19 vaccines given local restrictions, prioritization of interventions with increasingly constrained government budgets and healthcare resources, and conducting early evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine candidates to support procurement negotiations and vaccine preparedness planning.26–28 There is a rapidly evolving landscape of data from surveillance, modeling, and clinical trials, with expectations for immunization programs and advisory bodies to continuously incorporate new data and analyses to update recommendations. It has been argued that recommendation processes must adapt from static to agile, with “living” recommendations and guidance.29 The CAPACITI decision-support tool is well suited to promote this shift: transparent documentation of each step in the process means it is simple to update and recommunicate recommendations, and the focus on evidence limitations supports policy makers to iteratively prioritize and address evidence needs with local researchers. Accompanied with resources to make data and modeling available and adaptable to country policy makers, the CAPACITI decision-support tool could be a valuable resource in supporting immunization programs to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and other such public health emergencies.

Conclusion

The CAPACITI decision-support tool strengthens priority setting in LMICs, by structuring the process for stakeholders to contextualize evidence across disciplines. Piloting across 12 countries has identified the need for, and benefits associated with using, the tool as part of a comprehensive package for LMICs to strengthen their decision-making processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

The authors thank the pilot country teams in Cuba, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Mali, Thailand, and Zambia for their valuable contributions. The authors gratefully acknowledge the input from the CAPACITI Steering Committee (Ijeoma Edoka, Jerome Kim, Debra Kristensen, Marion Menozzi-Arnaud, Murat Ozturk), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Health Economics and Modeling Unit, So Yoon Sim, Veronica Denti, Julia Roper, Ado Bwaka, Pamela Mitula, Sidy Ndiaye, Gilson Paluku, Dijana Spasenoska, Don Ananda Chandralal Amarasinghe, Andrew Mirelman, and Alec Morton.

Funding/Support:

This work was supported by grant OPP1174807 from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor:

The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the article; and decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures:

Dr Giersing reported receiving grants to support the development of the CAPACITI decision support tool from World Health Organization during the conduct of the study. Dr Moore reported receiving personal fees from Pfizer and Sanofi Pasteur for service on external advisory boards regarding US-based vaccines, and personal fees for service on an external advisory board regarding US-based influenza vaccine from Seqirus outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chalkidou K, Glassman A, Marten R, et al. Priority-setting for achieving universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(6):462–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Revill P, Glassman A, eds. Understanding the Opportunity Cost, Seizing the Opportunity: Report of the Working Group on Incorporating Economics and Modelling in Global Health Goals and Guidelines. Washington, DC: Center for Global Development; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. In: From value for money to value-based health services: a twenty-first century shift. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021:WHO Policy Brief. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kristensen F, Husereau D, Huic M, et al. Identifying the need for good practices in health technology assessment: summary of the ISPOR HTA council working group report on good practices in HTA. Value Health. 2019;22(1):13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steffen C, Henaff L, Durupt A, et al. Evidence-informed vaccination decision-making in countries: Progress, challenges and opportunities. Vaccine. 2021. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.055. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Botwright S, Kahn A, Hutubessy R, et al. How can we evaluate the potential of innovative vaccine products and technologies in resource constrained settings? A total systems effectiveness (TSE) approach to decision-making. Vaccine X. 2020;6:100078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Oliveira L, Toscano C, Sanwogou N, et al. Systematic documentation of new vaccine introduction in selected countries of the Latin American Region. Vaccine. 2013;31(suppl 3):C114–C122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Immunization Analysis and Insights. Vaccine prioritization (CAPACITI). World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccinesand-biologicals/immunization-analysis-and-insights/vaccine-impact-value/economic-assets/vaccine-prioritization/. Accessed January 22, 2021.

- 9.Alonso-Coello P, Schünemann H, Moberg J, et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. BMJ. 2016;353:i2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phelps C, Lakdawalla D, Basu A, Drummond M, Towse A, Danzon P. Approaches to aggregation and decision making—a health economics approach: an ISPOR Special Task Force Report:[5]. Value Health. 2018;21(2):146–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilder-Smith A, Longini I, Zuber PL, et al. The public health value of vaccines beyond efficacy: methods, measures and outcomes. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baltussen R, Marsh K, Thokala P, et al. Multicriteria decision analysis to support health technology assessment agencies: benefits, limitations, and the way forward. Value Health. 2019;22(11):1283–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marsh K, IJzerman M, Thokala P, et al. Multiple criteria decision analysis for health care decision making—emerging good practices Report 2 of the ISPOR MCDA Emerging Good Practices Task Force. Value Health. 2016;19(2):125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inotai A, Nguyen H, Hidayat B, et al. Guidance toward the implementation of multicriteria decision analysis framework in developing countries. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;18(6):585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The prioritisation framework: making the most of your budget. Public Health England. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-prioritisationframework-making-the-most-of-your-budget. Accessed May 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oortwijn W, Jansen M, Baltussen R. Evidence-Informed Deliberative Processes. A Practical Guide for HTA Agencies to Enhance Legitimate Decision-Making. Version 1.0. Nijmegen: Radboud University Medical Centre, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences; 2019. http://www.radboudumc.nl/en/research/research-groups/global-health-priorities. Accessed May 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brouwers M, Kho M, Browman G, et al. AGREE II: Advancing guideline development, reporting, and evaluation in health care. Prev Med. 2010;51(5):421–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Methods for the Development of NICE Public Health Guidance. 3rd ed. Process and methods [PMG4]. NICE. http://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg4/chapter/developing-recommendations. Accessed May 23, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ultsch B, Damm O, Beutels P, et al. Methods for health economic evaluation of vaccines and immunization decision frameworks: A consensus framework from a European Vaccine Economics Community. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;34(3):227–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fung A. Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Admin Rev. 2006;66(s1):66–75. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phillips L, Phillips M. Facilitated Work Groups. Theory and practice. J Oper Res Soc. 1993;44(6):533. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guyatt G, Oxman A, Vist G, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson T, Sculpher M, Claxton K, et al. The international decision support initiative reference case for economic evaluation: an aid to thought. Value Health. 2016;19(8):921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreno-Calderón A, Tong T, Thokala P. Multi-criteria decision analysis software in healthcare priority setting: a systematic review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2019;38(3):269–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCormick BJJ, Waiswa P, Nalwadda C, Sewankambo N, Knobler S. SMART Vaccines 2.0 decision-support platform: a tool to facilitate and promote priority setting for sustainable vaccination in resource-limited settings. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(11):e003587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adamu A, Jalo R, Habonimana D, Wiysonge C. COVID-19 and routine childhood immunization in Africa: leveraging systems thinking and implementation science to improve immunization system performance. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:161–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gheorghe A, Chalkidou K, Glassman A, Lievens T, McDonnell A. COVID-19 and budgetary space for health in developing economies. Center for Global Development. http://www.cgdev.org/sites/default/files/GheorgheChalkidou-COVID-Budgetary-Space.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 28.WHO SAGE. WHO SAGE road map for prioritizing uses of COVID-19 vaccines in the context of limited supply. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/docs/default-source/immunization/sage/covid/sage-prioritizationroadmap-covid19-vaccines.pdf?Status=Temp&sfvrsn=bf227443_2&ua=1. Accessed September 30, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munn Z, Twaddle S, Service D, et al. Developing guidelines before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(12):1012–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.