Abstract

Objective:

The main objective of this review was to map the literature on the characteristics of patient navigation programs for people with dementia, their caregivers, and members of the care team across all settings. The secondary objective was to map the literature on the barriers and facilitators for implementing and delivering such patient navigation programs.

Introduction:

People with dementia have individualized needs that change according to the stage of their condition. They often face fragmented and uncoordinated care when seeking support to address these needs. Patient navigation may be one way to help people with dementia access better care. Patient navigation is a model of care that aims to guide people through the health care system, matching their unmet needs to appropriate resources, services, and programs. Organizing the available information on this topic will present a clearer picture of how patient navigation programs work.

Inclusion criteria:

This review focused on the characteristics of patient navigation programs for people living with dementia, their caregivers, and the members of the care team. It excluded programs not explicitly focused on dementia. It included patient navigation across all settings, delivered in all formats, and administered by all types of navigators if the programs aligned with this review’s definition of patient navigation. This review excluded case management programs.

Methods:

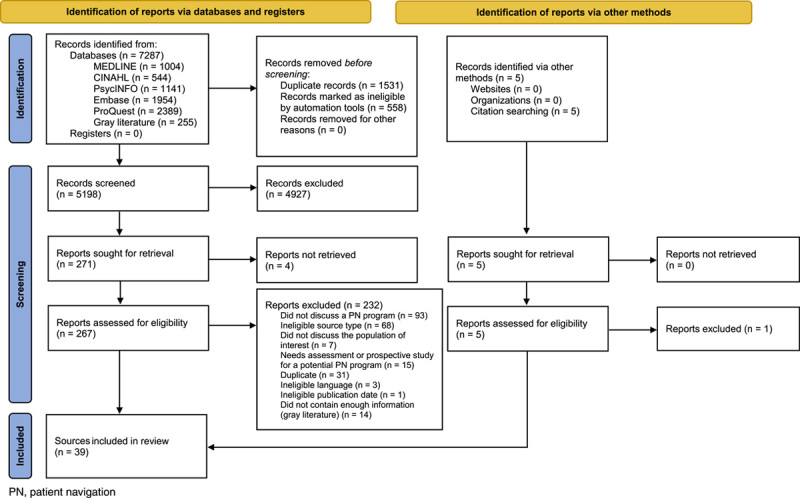

This review was conducted in accordance with JBI methodology for scoping reviews. MEDLINE, CINAHL, APA PsycINFO, Embase, and ProQuest Nursing and Allied Health databases were searched for published full-text articles. A gray literature search was also conducted. Two independent reviewers screened articles for relevance against the inclusion criteria. The results are presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram, and the extracted data are presented narratively and in tabular format.

Results:

Thirty-nine articles describing 20 programs were included in this review. The majority of these articles were published between 2015 and 2020, and based out of the United States. The types of sources included randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, and qualitative exploratory studies, among others. All programs provided some form of referral or linkage to other services or resources. Most dementia navigation programs included an interdisciplinary team, and most programs were community-based. There was no consistent patient navigator title or standard delivery method. Commonly reported barriers to implementing and delivering these programs were navigator burnout and a lack of coordination between stakeholders. Commonly reported facilitators were collaboration, communication, and formal partnerships between key stakeholders, as well as accessible and flexible program delivery models.

Conclusions:

This review demonstrates variety and flexibility in the types of services patient navigation programs provided, as well as in the modes of service delivery and in navigator title. This information may be useful for individuals and organizations looking to implement their own programs in the future. It also provides a framework for future systematic reviews that seek to evaluate the effectiveness or efficacy of dementia navigation programs.

Keywords: caregivers, dementia, health care delivery, patient navigation, scoping review

Introduction

Dementia is an umbrella term covering a collection of syndromes characterized by chronic cognitive impairment.1 Dementia commonly results in degenerative brain function, causing memory loss, communication difficulties, and declines in reasoning or other thinking skills that interfere with daily life.1,2 The most common type of dementia is Alzheimer’s disease.2 Other types include, but are not limited to, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and mixed dementia.2 According to the World Health Organization, there are 50 million people living with dementia around the world, with nearly 10 million new cases diagnosed every year.3

Dementia is a progressive condition, and people with dementia often have individualized needs that change according to the different stages of their condition.4 As a result, they often require care from multiple health and social care services and providers across diverse settings; because of this, they experience transitions in care over the duration of their illness.4–6 Unfortunately, dementia care is often characterized as fragmented, uncoordinated, and difficult to navigate.4–6 People with dementia and their caregivers report a lack of knowledge and information about dementia and available support services, as well as limited access to relevant health and social care.1,4,7 As expected, these challenges can have negative repercussions for people with dementia, contributing to poor care transitions and extended hospital stays.6 These challenges can also have a negative impact on caregivers of people with dementia, who tend to report poor mental health, high rates of burnout and social isolation, and financial strain.1,8–10

Patient navigation is one way to address the care needs of people with dementia and their caregivers. Patient navigation is a model of care designed to guide and support people through health and social care systems to help them meet their care needs. It seeks to reduce the fragmentation of programs and services, improve access to care, and integrate care across settings and sectors.11–13 This process is facilitated by patient navigators. Patient navigators perform many tasks, such as providing tailored information and advice to patients and caregivers, assisting with goal-setting and decision-making, and connecting patients to social and health care providers and relevant support groups.6,11 Navigators may have backgrounds as health care professionals, laypersons, or persons with lived experience as either patients or caregivers. However, the term “patient navigator” is not used consistently in literature or practice.14,15 These individuals may also be referred to as care coordinators, system navigators, or peer navigators, among other titles. Patient navigators often work across a range of settings, including in the community, clinics, or hospitals.14,15

Implemented by Dr. Harold Freeman in New York City in the 1990s, the first patient navigation program was designed to support patients with cancer through the emotional, physical, and financial challenges associated with diagnosis and treatment.16 Patient navigation has since been adapted to assist people with other health issues and illnesses, such as diabetes,17,18 epilepsy,19 kidney disease,20 and mental health and addiction.21 There is some research to support patient navigation as a feasible model for people with dementia and their caregivers.22 Patient navigation can benefit this population because it operates across the continuum of care, can be adapted as dementia progresses, and is efficient and scalable.23 Moreover, patient navigators can be added to existing health systems without significant changes to the system or extensive care provider training. As more people develop dementia every year, patient navigation programs are one way to help meet the resulting challenges. However, there have been limited studies or reports related to the characteristics of patient navigation programs for this population.

This scoping review mapped the literature on the characteristics of patient navigation programs—a relatively new approach to care—for people with dementia, their caregivers, and members of the care team. We chose to conduct a scoping review to organize all available information on this topic, as well as to build a picture of how patient navigation programs work. A preliminary search of the PubMed database, JBI Evidence Synthesis, and PROSPERO confirmed that there were no current or ongoing reviews on this topic. An a priori scoping review protocol was registered and published.24

The main objective of this review was to map the literature on the characteristics of patient navigation programs for people with dementia, their caregivers, and members of the care team across all settings. The secondary objective was to map the literature on the barriers and facilitators for implementing and delivering these patient navigation programs.

Review question

What are the characteristics, barriers, and facilitators of patient navigation programs that have been reported in the literature to support people with dementia, their caregivers, and/or members of the care team?

Inclusion criteria

Participants

This scoping review focused on patient navigation programs for people with dementia, their caregivers, and/or members of the care team. People with dementia were defined as people who had received a dementia diagnosis. Types of dementia included, but were not limited to, Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, traumatic brain injury, untreated HIV infection, and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome. Programs for people with Huntington’s disease, cognitive dysfunction, or cognitive impairment were also considered for inclusion. Caregivers were defined as people who provide unpaid care or support for individuals but who may receive a pension or government allowance to help them in this caregiving role. Caregivers may or may not live with the person they are supporting and could be a family member, friend, or neighbor. Members of the care team were defined as those who work in the health or social care systems and provide services for people with dementia and/or their caregivers. These individuals can be either professionals or non-professionals.

Concept

The main concept covered in this review was the characteristics of patient navigation programs that support people living with dementia, their caregivers, and/or members of the care team. This review defined patient navigation programs as one or more interventions or services that target people with dementia, their caregivers, and/or members of the care team with the goal of improving navigation of services and resources for this population. A navigator, whether a professional or lay navigator, provided the services.15,25,26 Patient navigator support could be educational, emotional, or logistical. It could be used to navigate services, treatments, programs, or resources. To cast a wide net across potentially relevant sources, our search strategy used different terms related to patient navigators (eg, peer navigator, nurse navigator), as well as terms synonymous with patient navigation (eg, health navigation, care coordination, system navigation). The determination of what qualified as a patient navigation program was based on information such as program description, services provided, or program goals.

This review excluded patient navigation programs that do not explicitly focus on people with dementia, their caregivers, and/or members of their care team. This review also excluded case management programs. There is overlap between case management and patient navigation,27 as both types of programs employ health care workers to provide individualized assistance to patients and caregivers.26,27 However, case managers are typically individuals with professional experience (eg, nurses, social workers), whereas patient navigators can be individuals with or without professional experience (eg, knowledgeable peers). Moreover, patient navigators provide support rather than clinical care, and work to help patients navigate existing systems and services.26 Case managers, on the other hand, can provide clinical care (eg, psychosocial treatment) when confronted with gaps in services and programs. Finally, patient navigation programs are usually more accessible to patients and caregivers than case management programs, which often involve eligibility requirements.26

The secondary concept included in this review was barriers and facilitators for the implementation and delivery of patient navigation programs for people with dementia, their caregivers, and/or the care team. We widened the definition of our secondary concept to include delivery, which is a deviation from the protocol. We did this to more fully capture the barriers and facilitators patient navigation programs encounter when providing services and to avoid limiting the data we captured to implementation. Articles did not need to mention barriers or facilitators to be included. However, it was a requirement for articles to describe the characteristics of dementia navigation programs because it was the central concept of this review.

Context

This review included patient navigation in all settings, such as clinics, hospitals, long-term care centers, and community spaces, as well as services offered in person or remotely. There were no geographic limits placed on this review. The review was limited to publications published in or after 1990, because that was the year patient navigation was conceptualized.28

Types of sources

This scoping review included peer-reviewed published papers and gray literature. The peer-reviewed literature could include any type of study design (eg, qualitative studies, quasi-experimental studies, mixed methods studies). Descriptive reports and study protocols were also considered. We excluded all reviews, such as systematic and scoping reviews; however, the reference lists of relevant reviews were hand-searched for additional articles. Gray literature, such as unpublished papers or evaluation reports, were included.

Methods

This review was conducted using the JBI methodology for scoping reviews 29 and followed an a priori protocol.24

Search strategy

The search strategy aimed to locate both published and unpublished material. A multi-step approach was implemented by a JBI-trained librarian (AG) to develop the search strategies for this review. First, an exploratory search was performed in MEDLINE (Ovid) and CINAHL (EBSCOhost) and an analysis of the text words contained in the titles, abstracts, and subject descriptors was undertaken. Second, the search terms identified in step 1 were grouped into 2 concept blocks (patient navigation and dementia), and a search strategy was drafted in MEDLINE by testing these terms to ensure the results reflected the scope of research available on the topic. At this stage, the draft search strategy was reviewed by a second librarian (RW) using the Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) guidelines30 and finalized. Third, the search strategy was adapted and implemented by AG in December 2020 across the following databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), CINAHL (EBSCOhost), APA PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), Embase (Elsevier), and ProQuest Nursing and Allied Health. Databases were searched from inception to December 2020. See Appendix I for the full search strategies. The reference lists of reviews were screened for additional papers, as were the reference lists of included articles.

Language and date limits were used as screening criteria and therefore were not applied to the search strategies. Only full-text articles published in English or French were included because those are the languages spoken fluently by the 2 independent reviewers.

The process of locating sources of unpublished studies and gray literature included searching ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, Google Scholar, and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) database, as well as targeted searching in Google and websites of known patient navigation or dementia organizations and programs (eg, Alzheimer’s Association website). We added CADTH, a specialized health care database, after the publication of the protocol to expand our gray literature search. For each search, the first 100 results per source were examined. The search took place between May and June 2021.

Source of evidence selection

Following the search, all identified records were collated and uploaded into EndNote v.X8.2 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) and duplicates were removed. The results were then transferred to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia), where any duplicates missed by EndNote were removed. Two independent reviewers (GA and KJK) screened the titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. Any disagreements about the eligibility of a paper were resolved through discussion. Next, the 2 reviewers screened the full texts of the articles against the inclusion criteria. Once again, any disagreements about the eligibility of a paper were resolved through discussion. When agreement was not reached, the reviewers consulted a third reviewer (AL or SD). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Figure 1) shows the search strategy and study inclusion process. The decisions for exclusion are reported according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews checklist (PRISMA-ScR).31 Full-text studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, and reasons for their exclusion are provided in Supplemental Digital Content 1: http://links.lww.com/SRX/A3.

Figure 1.

Search results and source selection and inclusion process31

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (GA and KJK) used a data extraction tool developed for this review (see Appendix II) to extract data from papers included in the scoping review.24 The data extraction tool presented in the protocol was modified and revised during the process of data extraction. It was adapted to remove the row for program services because of the overlap with the column on program description.

Extracted data included i) author and year of publication; ii) type of source or study design (where applicable); iii) program characteristics (including geographic location, setting, delivery format, population and condition type), team composition, and navigator title; iv) barriers where applicable; and v) facilitators where applicable. The designation of what was a barrier or facilitator was based on the attributions by the authors of the included studies. The reviewers used Google Sheets to manage the extracted data. Any disagreements that arose between reviewers were resolved through discussion or with a third reviewer (AL).

Data analysis and presentation

A narrative summary describes how the results relate to the objectives of the scoping review. The full results of the search are reported in 2 tables that align with the objectives and question of this scoping review. The tables report specific details about patient navigation programs that serve people with dementia, their caregivers, and/or the care team. Appendix III includes author and year of publication; the type of source or study design; geographic location; setting; delivery format; population and condition type; team composition; and navigator title. Appendix IV contains the program description and services, barriers, and facilitators.

Results

Study inclusion

A total of 7287 records were retrieved through the search strategy (7032 from the database searches and 255 from the gray literature search). From the 7032 database records, EndNote identified and removed 1531 duplicates. A total of 5501 database sources were then uploaded to Covidence, where an additional 496 duplicates were identified and removed. When the 255 records from the gray literature search were uploaded to Covidence, 62 duplicates were removed. The reviewers thus screened a total of 5198 titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria. Of the potentially relevant reports, we sought 271 full-text citations, but were unable to retrieve 4. We assessed 267 reports in detail against the inclusion criteria. Reasons for excluding 232 full-text papers are presented in Supplemental Digital Content 1: http://links.lww.com/SRX/A3. The majority of reports excluded at full-text screening did not describe a patient navigation program or were ineligible source types (eg, conference abstracts). Hand-searches of relevant reviews and the reference lists of included sources produced an additional 4 articles. A total of 39 sources were included in this scoping review. Figure 1 shows the search strategy and source selection and inclusion process.31

Characteristics of included sources

A majority of the sources (n=28) were published between 2015 and 2020. Notably, 7 sources were published in 2020, and 8 sources were published in 2019. These sources included randomized controlled trials (n=9), quasi-experimental studies (n=3), qualitative exploratory studies (n=8), cross-sectional research studies (n=2), editorials (n=2), descriptive studies (n=2), mixed methods studies (n=4), cost analyses (n=2), protocols (n=3), reports (n=2), a brochure (n=1), and an information sheet (n=1).

Review findings

Across the 39 articles, there were 20 different patient navigation programs. Seven articles reported on the program Maximizing Independence (MIND) at Home, based out of Maryland, United States.32–38 Seven articles reported on Care Ecosystem, a program based in California, Nevada, and Iowa in the United States.22,39–44 Six articles reported on the Partners in Dementia Care program organized by US Department of Veterans Affairs and the Alzheimer’s Association.45–50 Two reports discussed the Dementia Navigator Service in Islington, a borough in London, United Kingdom.51,52 Two articles described LIVE@Home.Path, a program based in three municipalities in Norway.53,54 The remainder of the 15 programs were the subject of a single article each.

Programs were based in the United States (n=12), the United Kingdom (n=2), Australia (n=2), Canada (n=2), Norway (n=1), and New Zealand (n=1). In the United States, programs were based in California, the District of Columbia, Florida, Iowa, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, and Virginia.22,32–50,55–59 Programs in the United States were either statewide initiatives22,39–50,56,58 or concentrated in specific cities, such as Miami, Cleveland, or Baltimore.32–38,55,57,59 In Canada, programs were based in the provinces of Ontario and Saskatchewan.60,61 In the United Kingdom, programs were based out of Gateshead, Halton, and the Islington borough of London.51,52,62 In Australia, one program was based in Adelaide, South Australia, while the other was in Melbourne, Victoria.63,64

Program descriptions and services

All the patient navigation programs provided some form of referral and/or linkage to other services, resources, or care. They linked clients to community resources and services according to their region and/or socioeconomic background, assisted clients on how best to use these services to meet their needs, and sometimes contacted service agencies for clients or caregivers. Resources included information on dementia, behavior management, or respite (eg, adult day programs). Most of the programs (n=12) included the provision of education for people with dementia and their caregivers, either in the form of courses or tailored educational and informational resources.32,33,37,39,40,48,53–59,64–67 Ten programs involved assessments to evaluate and respond to clients’ needs during intake.32,35,41,45,47,48,56,59–61,64,68 Four programs used protocols to assess clients and their needs.37,40,42,47,59 Two other programs included resource libraries to benefit clients.55,62

Some programs (n=7) reported providing and supporting individualized care planning.22,32,54,59,61,63,66 Care coordination and liaising with primary care was another common service (n=9).33,37,40,41,47,48,56–58,61,64,65,68 Three programs provided emotional support or coaching to clients.40,42,45,48,54,57 Four programs assisted with needs related to legal issues or providing tools or resources to navigate legal issues.22,32,56 Three programs helped clients to develop coping and communication skills,39,56,61 and another provided behavioral management skills training.32

Team composition

Among the articles that reported on team composition, most (n=13) were delivered by an interdisciplinary team, such as nurses, pharmacists, or lay navigators.22,32,33,45,49–52,55–57,61,64,66–69 Three programs were delivered exclusively by clinicians, which were made up of either a mix of clinicians (ie, nurses, physicians) or only nurses.53,62,63 There were 2 teams made up of trained, nonclinical lay workers (ie, unlicensed coordinators).59,60 Notably, even programs that did not have clinical or licensed workers as team or staff members (eg, the First Link program) provided navigational support to individuals who had been referred to them by physicians.60 As such, all programs had some involvement of care providers.

Program setting

A majority (n=19) of programs were community-based.22,32,36,38,40,42,45,48,49,51,53,54,56–68 Community settings included municipal resource centers, memory clinics, and urban academic health centers based in the community. One program did not specify where it was based.55

Mode of delivery

There was no standard or universal mode of delivery for patient navigation programs. Modes of delivery included in person, telephone-based, web-based, or a combination. The most common approach was a combination of service delivery by phone and in person (n=9).51,53,54,56,62,63,65,66,68 Two programs delivered services by telephone, email, mail, and in person.40,42,46,47 Three programs were delivered only by telephone,57,59,60 and 2 programs were delivered only in person.58,61 One program provided services in person, by telephone, and by email.33 Within each program, communication methods were not uniform to all clients, but were adapted according to client needs. For example, a care team navigator from the Care Ecosystem program initially met the family in person, but follow-up services were typically delivered by telephone, email, mail, or a combination of these.40,41

Patient navigator titles

There was no standard professional title for individuals providing patient navigation services across programs. The most commonly used title was “care coordinator,” which 4 programs used,46,47,55,57,64 while 2 programs used “care consultant”58,59 and 2 programs used “dementia navigator.”52,68 Many of the titles were variations on the term “coordinator.” These included clinic coordinator,61 First Link Coordinator,60 memory care coordinator,36 support coordinator,66 Project Learn MORE coordinator,56 dementia care coordinator,67 service coordinator,65 or simply coordinator.53 Other titles incorporated the term “navigator,” such as care team navigator,22 Alzheimer’s patient navigator,69 and primary care navigator.62 One program was operated by specialist dementia nurses.63 There was no apparent relationship between the title of the navigators and the settings; coordinator and navigator titles were both used in community and clinical settings.

Target population

Most programs (n=16) served only people with dementia,40,42,45,50,52,57–59,64–67,69 whereas 4 programs served patients with dementia and people with cognitive impairment or a cognitive disorder.33,37,61,63,68 Five programs had age requirements, which varied from program to program.22,36,45,57,59 Age requirements included 45 years and older,39 50 years and older,45 60 years and older,57 and 70 years and older.34 Five programs required that clients be living at home and in the community to be eligible to receive services, because the goal of those programs was to help people to stay in the community longer.34,53,57,59,64 Seven programs required a diagnosis of dementia to be eligible for the program.37,42,45,53,54,56,57,60,66 Six programs required that clients, in this case people with dementia and their caregivers, be served together as dyads.34,42,47,48,53,57,64 One program was only for caregivers.67 The Partners in Dementia Care, Telephone-Linked Care, and Veterans Affairs Dementia Care Coordinator programs had the additional requirement that people with dementia also be veterans.46,57,67 No programs reported targeting the care team.

Barriers

Two articles that described the same program listed burnout and stress among patient navigators as barriers.22,41 Four articles describing 4 programs reported initial and ongoing difficulties coordinating with primary care providers or with key partners and partnering organizations, showing a lack of coordination across team members or stakeholders.32,48,56,61 Two articles describing 2 programs reported difficulty using referrals to recruit clients.56,60 This represented a barrier because it demonstrated the referring physicians’ lack of understanding of the program’s services. Organizations that operated exclusively or mainly through referrals to the program (First Link and MIND at Home) faced difficulties with recruitment.34,60 One of these programs also required a diagnosis,60 which can act as a barrier because dementia is often underdiagnosed.70,71 One article described identifying resources for people who are on a low income, do not speak English, or live in rural areas as barriers.39 Initial barriers to implementation included an absence of clear communication between all team members,61 and coordination between primary care providers and other team members.32,39

Facilitators

Twelve articles describing 7 programs listed collaboration and communication between key stakeholders, as well as formal partnerships between health care and community organizations, as facilitators for the development and implementation of patient navigation programs.22,32,34,38,45–48,57,59–61 These facilitators included linkages between organizations and key players,47,48,61 such as embedding representatives of the local Alzheimer Society chapters into memory clinics.61 It is also beneficial if program organizers, caregivers, and program site partners demonstrate an equal willingness to actively support and participate in the programs.48

Another commonly reported facilitator was a flexible and adaptable delivery model, which encouraged frequent and flexible communication with clients. Ten articles describing 7 programs listed this facilitator.32,39,40,42,44,45,48,56,60,68 Four articles describing 2 programs identified working closely with caregivers and coaching caregivers as facilitators for implementing program activities.22,39,47,48 Four sources describing 3 programs identified navigators’ listening skills and ability to form positive relationships with clients as facilitators.22,44,51,63

Several articles discussed logistical and administrative tools that facilitated program implementation. For example, 4 articles describing 3 programs reported a shared computer system or a specialized database for providing coordination, access to information, and information-sharing between key players. These key players included the navigator and members of the care team, sometimes across multiple organizations such as the Alzheimer’s Association chapters and Veterans Affairs.47,48,56,57 Six articles describing 4 programs reported tools and protocols for security of data and personal information, as well as program implementation (eg, implementation handbook, needs assessment).36,37,48,56,63,64 One article discussed the need for adequate space and necessary administrative support for documentation and records systems.61

An additional facilitator of program implementation that was identified in multiple articles was funding and the affordability of navigation programs. For example, 5 articles describing 3 programs listed affordability of programs and cost-effectiveness as facilitators.37,38,41,45,48 One article reported cost to be an initial barrier to implementation, although the patient navigation program may save money in the long term.33 For one program, a factor that helped ensure the program’s affordability was the employment of lay navigators. Opting not to employ specialized health professionals ensured these programs were more affordable.41 One article reported that costs decreased substantially during the implementation period and depended on caseload.43

Discussion

The results of this review provide considerable insight into the characteristics, barriers, and facilitators of patient navigation programs for people with dementia and their caregivers. Although characteristics varied across the 20 programs, most programs were located in the community, had interdisciplinary care teams, and delivered a variety of services, mainly through a combination of telephone and in-person mechanisms. Barriers and facilitators also varied across programs. The most reported barriers were navigator burnout and stress, as well as a lack of coordination between internal and external stakeholders. Conversely, the most reported facilitator was coordination between internal and external stakeholders.

Some of the defining characteristics of patient navigation are the combination of care coordination interventions, such as facilitating access to services and resources, and building and developing a relationship between the navigator and client.72,73 In line with this understanding of patient navigation, all of the programs included in this review connected people with dementia and their caregivers to appropriate services and resources within the health care system and/or the community. While the specific services and supports provided by patient navigation programs varied, these programs all focused on improving the coordination of care and access to services across providers and settings. More specifically, programs offered logistical and care coordination support, such as providing individualized care planning, needs assessments, educational training or resources, and referrals and/or linkages to other services, resources, or care. This range of services across programs demonstrates a more general trend of how patient navigation programs can adapt based on context and client needs, which is often cited as an advantage of patient navigation programs.74,75 This flexibility in the provision of services benefits both the clients, who have specific and individualized needs, as well as the institutions and organizations that administer the programs, which can tailor the program to their own needs and goals as well.74

Although there is flexibility in where patient navigators can be based, a majority of the patient navigation programs in this review were based in the community. These programs were accessed via clinics, referrals from primary care providers, referrals from service organizations with staff trained in dementia case-finding, letters from service providers to their clients, and general community outreach. Community-based programs can benefit people with dementia by filling social needs, as well as by reducing stigma associated with dementia.76 For people with mild or moderate dementia, these community-based programs can have positive effects on cognitive functioning and improve communication and quality of life.77,78 Moreover, community-based programs can also decrease depression, stress, social isolation, and burden among caregivers,79–81 while increasing their quality of life.79,82 Community-based programs can also help support aging in place, a common desire among older persons.83 This review showed that there is an absence of patient navigation programs for people with dementia in hospital settings in the literature. Because people with dementia often have other comorbidities and difficulties with their health, hospital-based programs can still be beneficial.84,85

While eligibility requirements varied, most programs targeted people with dementia and their caregivers, but none targeted the care team. Many programs had broad eligibility requirements, whereas others had requirements around age, diagnosis, living in the community, and enrolling with a caregiver. Considering that patient navigation started as a way to facilitate care for people who face significant barriers related to factors such as poverty, broad eligibility requirements are in line with the principles of patient navigation. Programs with specific requirements, such as a diagnosis of dementia, can be challenging to access, because it can be difficult to get a timely appointment with a doctor to receive a dementia diagnosis or to obtain a diagnosis once the initial contact with a doctor is made.86–89 This is one of the reasons why dementia is often underdiagnosed.90

There are also cases of people with dementia (or their caregivers) mistaking symptoms for normal aging or experiencing stigma, which may also delay their attempts to seek support.91,92 Furthermore, there are inequalities to receiving a dementia diagnosis, and many groups face significant delays, particularly in immigrant communities (eg, African, Asian, and Anglo-European Americans; British South-Asian communities).93 Therefore, populations that face increased barriers can benefit from patient navigation programs with broad eligibility criteria. In our review, the programs with the most requirements (eg, age requirements, inclusion of caregivers as dyads, diagnosis requirements) were funded as research studies and thus had stricter inclusion criteria.32,40 Similarly, the programs requiring clients to be veterans were organized by the US Department of Veterans Affairs.42,57

For patient navigation programs in general, regardless of conditions and populations, navigators can work independently or within a team.14 This scoping review found that the majority of teams were interdisciplinary and included clinical and nonclinical staff. According to the core principles of patient navigation, the integration of navigators into health care teams optimizes patient care.12 Indeed, the programs captured by this review were all connected to care providers, either as team members or through program referrals from care providers. Generally speaking, patient navigation programs administered by health care professionals or interdisciplinary teams tend to focus on patient populations with complex health and social care needs.14,94 Programs that are integrated into the health care system may be most appropriate for people with dementia, as they often present with complex care needs and comorbidities.95,96 Notably, not everyone has access to care providers or an interdisciplinary care team. Patient navigators could help people with dementia gain access to a care team so that they can receive a diagnosis and postdiagnostic supports. Moreover, patient navigation programs can help patients and caregivers better understand the diagnostic process. Research has shown that interdisciplinary care teams can benefit older patients with complex care needs because they provide specialized knowledge and expertise from multiple disciplines.97 Interdisciplinary care can benefit people with dementia specifically by improving care and well-being, improving care outcomes, and decreasing the risk of hospital readmission.98,99

Not surprisingly, there was a lack of consistency in the professional titles of individuals implementing patient navigator programs. However, most programs used variations of the terms “coordinator” and “navigator.” This variation in titles is consistent with findings from other studies and reviews that have examined patient navigation programs.14,26,100 Despite the inconsistent terminology, the recurrence of “navigator” and “coordinator” represents the main purposes of patient navigators; that is, the assistance with coordination and navigation of available care, services, and resources. These professional titles also demonstrate one of patient navigation’s core functions: eliminating barriers to ensure that patients receive timely care.12 Our review found that the services provided across all position titles overlapped. Coordinators and navigators alike provided referrals and linkages, education, emotional support, and care coordination.22,46,55,57,69

This review found no standard mode of delivery for patient navigation programs presented in the literature. Patient navigation programs were delivered in person, using telephone-based or web-based communication, or some combination. The range of contact methods for patient navigation programs for people with dementia and their caregivers is consistent with patient navigation programs for other populations and other conditions, such as cancer and diabetes. For example, clients with other conditions contact patient navigators by telephone,11,18,26,27,101 by email,26 in person,26,101 or a combination.102 The lack of standard mode of delivery across programs and, in some cases, even within programs, suggests that communication is personalized according to client needs. This flexibility in communication for people with dementia reflects another strength of patient navigation: flexibility based on the context of the program and client needs.74,75 Indeed, a successful relationship between a client and a patient navigator requires flexibility on the part of the navigator.72 This flexibility also ensures that patient navigation remains a patient-centric approach, which is central to this model of care.12

Barriers to developing patient navigation programs for people with dementia are consistent with the difficulties encountered during the development of other types of patient navigation programs. For example, programs in the current review noted difficulty locating resources for individuals who were low-income, did not speak English, or lived in rural areas, which fits with previous studies in other areas.21,103,104 This finding also reflects dementia care more generally, as there are limited dementia-related support and education services in rural communities.105,106 Our review found that burnout was the primary barrier associated with the delivery of patient navigation programs for people with dementia. Navigator burnout is a commonly cited barrier to patient navigation programs serving other populations as well.107,108 Due to the frequently adaptable nature of patient navigation, navigators may not have clearly defined roles and tasks. As such, in responding to client needs, they often take on tasks beyond their role.107,109 According to research in other areas, setting boundaries and fostering social support by creating support networks with other patient navigators, either within the organization or across multiple organizations, can be one solution to burnout.107,109 Support from supervisors or managers can also be useful for establishing boundaries.107 Standardized training and skill development is another way to help navigators set boundaries in their professional lives and build resilience to avoid burnout.109

The most common facilitators for the development and implementation of patient navigation programs for people with dementia were collaboration and communication between key stakeholders. This included formal partnerships between health care and community organizations. This finding is consistent with patient navigation programs for other populations and conditions, such as mental health and vulnerable populations.21,75,110–112 It is also consistent with literature showing that collaboration facilitates the successful integration of dementia care more generally.6

The availability of specialized computer systems was another common facilitator for patient navigation programs identified in this review. This is also a facilitator for programs serving other populations.75,110,113–115 Although we found that cost was presented as a facilitator, this was not always reflected in the literature. This review, as well as research on patient navigation in general, found that it mainly depended on the availability of funding for the patient navigation program. Programs serving other populations have listed “maintaining funding for navigators” as a challenge.21,75,116 Notably, many of the programs included in this scoping review secured funding through a research grant, through the Department of Veterans Affairs, or through a community partnership, such as with the local or provincial Alzheimer Society chapter. A recommendation repeated across articles on navigation programs for other conditions was partnering with agencies or community partners.21,75,110 Community-based programs can also reduce costs because they can help people live at home longer, which costs less than long-term care in either a nursing home or a hospital. Community-based programs can also support caregivers by precluding their need to retire early or change working hours.79,117 This fits with one of the primary principles of patient navigation; namely, that it should be cost-effective.12

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review provides important knowledge on the characteristics, the barriers, and facilitators of patient navigation programs for people with dementia and their caregivers. The strengths of this scoping review include the comprehensiveness of the search strategy and the strict inclusion criteria that allowed the selection of sources. Notably, this scoping review did not locate any programs from South America, Asia, or Africa. The evidence related to those countries and continents may have been missed due to the language limits of the reviewers, who only spoke English and French. It is also possible that patient navigation programs may be less common in these regions. Furthermore, the literature search was limited to 1990 and beyond, 5 databases, and a gray literature search. It is possible that the search strategies may not have identified some relevant publications. Finally, this review did not report on outcomes of patient navigation programs. Although reporting on outcomes was not our purpose, it would have provided insight into the effectiveness of the patient navigation programs.

Conclusions

In recent years, rates of dementia around the world have increased, resulting in a greater need for dementia care. People with dementia and their caregivers continue to face many barriers to care. Initiatives such as patient navigation programs, which provide individualized and flexible support to people with dementia, their caregivers, and members of the care team, are one way to overcome barriers to care within health and social care systems. The purpose of this scoping review was to learn about the patient navigation programs and map the literature on their characteristics, barriers, and facilitators. Results showed that most programs are intended for people with dementia and their caregivers rather than care team members, are based in the community, involve interdisciplinary teams, and have variety and flexibility in terms of their characteristics. This was reflected in the range of services the programs provided, the modes of service delivery, navigator titles, and eligibility requirements. Barriers and facilitators for program development and implementation also varied. Program barriers included navigator burnout and locating resources to address specific needs. Common facilitators were collaboration between health care and community organizations, flexible delivery models, program affordability, and logistical and administrative tools.

Implications for research

This information may be useful for individuals and organizations looking to implement their own dementia navigation programs. It will also provide a framework for future systematic reviews that seek to evaluate the effectiveness of dementia navigation programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Richelle Witherspoon reviewed the search strategy. Katherine J. Kelly contributed to data collection by acting as an independent reviewer for the search of published materials. Hannah Trites and Matt Douglas contributed to data collection by acting as an independent reviewer for the gray literature review.

Funding

This project is supported by Healthcare Excellence Canada (formerly the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement) and the New Brunswick Innovation Foundation. Neither funder had any input into this review.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to designing the methodology for this review and approved the final manuscript. GA wrote and edited the manuscript. AL, ALM, LM, and SD contributed to the writing and editing. AG created the search strategy, co-wrote and edited a section of this review, and edited the appendices. SD and AL are also co-leading the larger research study.

Appendix I: Search strategy

| Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, in Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R) 1946 to December 15, 2020 – Searched December 17, 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|

| # | Search string | Records retrieved |

| 1 | exp Patient Navigation/ | 790 |

| 2 | "Navigat*".ab,ti,kf,kw. | 42,982 |

| 3 | (coordinat* adj2 care).ab,kf,kw,ti. | 9594 |

| 4 | 1 OR 2 OR 3 | 52,361 |

| 5 | exp Dementia/ | 169,851 |

| 6 | exp Cognitive Dysfunction/ | 19,764 |

| 7 | "Dement*".ab,ti,kf,kw. | 120,702 |

| 8 | "Alzheimer*".ab,ti,kf,kw. | 154,083 |

| 9 | cognitive impairment.ab,kf,kw,ti. | 61,781 |

| 10 | Cognitive dysfunction.ab,kf,kw,ti. | 14,842 |

| 11 | "Huntington*".ab,kf,kw,ti. | 18,414 |

| 12 | "cognitive decline".ab,kf,kw,ti. | 23,756 |

| 13 | 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 OR 12 | 322,350 |

| 14 | 4 and 13 | 1004 |

| CINAHL Full-Text (EBSCOhost) – Searched December 17, 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|

| # | Search string | Records retrieved |

| 1 | (MH "Patient Navigation") | 1419 |

| 2 | Navigat* | 16,723 |

| 3 | coordinat* N2 care | 8400 |

| 4 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 | 24,738 |

| 5 | (MH "Dementia+") | 74,546 |

| 6 | Dement* | 66,578 |

| 7 | Alzheimer* | 43,816 |

| 8 | cognitive impairment | 43,533 |

| 9 | Cognitive dysfunction | 26,303 |

| 10 | cognitive decline | 12,746 |

| 11 | Huntington* | 2511 |

| 12 | S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 | 132,997 |

| 13 | S4 AND S12 | 544 |

| APA PsycINFO (EBSCOhost) – Searched December 17, 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|

| # | Search string | Records retrieved |

| 1 | Navigat* | 23,672 |

| 2 | coordinat* N2 care | 3292 |

| 3 | S1 OR S2 | 26,832 |

| 4 | DE "Dementia" OR DE "AIDS Dementia Complex" OR DE "Dementia with Lewy Bodies" OR DE "Presenile Dementia" OR DE "Pseudodementia" OR DE "Semantic Dementia" OR DE "Senile Dementia" OR DE "Vascular Dementia" | 46,821 |

| 5 | DE "Alzheimer's Disease" | 47,661 |

| 6 | DE "Cognitive Impairment" | 37,902 |

| 7 | DE "Huntingtons Disease" | 3273 |

| 8 | DE "Presenile Dementia" OR DE "Alzheimer's Disease" OR DE "Creutzfeldt Jakob Syndrome" OR DE "Picks Disease" | 48,711 |

| 9 | DE "Memory Disorders" | 13,602 |

| 10 | dement* | 81,645 |

| 11 | alzheimer* | 70,975 |

| 12 | cognitive impairment | 83,458 |

| 13 | Cognitive dysfunction | 49,360 |

| 14 | cognitive decline | 24,402 |

| 15 | Huntington* | 6079 |

| 16 | S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 | 199,248 |

| 17 | S3 OR S16 | 1141 |

| Embase – Searched December 17, 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|

| # | Search string | Records retrieved |

| 1 | 'patient navigator'/exp | 15 |

| 2 | 'patient navigator program'/exp | 11 |

| 3 | 'care coordinator'/exp | 274 |

| 4 | 'care coordination'/exp | 53 |

| 5 | navigat*:ti,ab,kw | 57,100 |

| 6 | (coordinat* NEAR/2 care):ti,ab,kw | 14,172 |

| 7 | #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 | 70,636 |

| 8 | 'dementia'/exp | 372,932 |

| 9 | 'cognitive defect'/de | 173,185 |

| 10 | dement*:ti,ab,kw | 177,834 |

| 11 | alzheimer*:ti,ab,kw | 214,737 |

| 12 | 'cognitive impairment':ti,ab,kw | 97,617 |

| 14 | 'cognitive decline':ti,ab,kw | 37,140 |

| 15 | 'cognitive dysfunction':ti,ab,kw | 22,488 |

| 16 | huntington*:ti,ab,kw | 25,183 |

| 17 | #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 | 580,809 |

| 18 | #7 AND #17 | 1954 |

| ProQuest Nursing & Allied Health – Searched December 18, 2020 | ||

|---|---|---|

| # | Search string | Records retrieved |

| 1 | MESH.EXACT.EXPLODE("Patient Navigation") | 34 |

| 2 | navigat* | 92,030 |

| 3 | coordinat* NEAR/2 care | 42,338 |

| 4 | 1 OR 2 OR 3 | 128,739 |

| 5 | MESH.EXACT.EXPLODE("Dementia”) | 9314 |

| 6 | ((ab(dementia) OR ti(dementia)) | 32,807 |

| 7 | ((ab(Alzheimer*) OR ti(Alzheimer*)) | 27,572 |

| 8 | ((ab(cognitive NEAR/1 (impairment OR dysfunction OR decline)) OR ti(cognitive NEAR/1 (impairment OR dysfunction OR decline))) | 21,164 |

| 9 | ((ab(Huntington*) OR ti(Huntington*)) | 3197 |

| 10 | 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 | 66,767 |

| 11 | 4 AND 10 | 2389 |

Gray literature search

We searched keywords based on those found in our database search strategies. The searches were iterative, which is typical for gray literature searching. We limited the searches to the English language. For each search, we examined the first 100 results per source (some searches had fewer than 100 results). The gray literature review was conducted between May and June 2021.

https://www.google.com/ terms searched

Navigation Programs Dementia

Dementia Navigator

Patient Navigation Dementia

Patient Coordinator Dementia

Cognitive Dysfunction Patient Navigation

Cognitive Impairment Patient Navigation

Dementia Navigation

Dementia Coordination

Alzheimer’s Patient Navigation

Alzheimer’s Patient Coordination

Dementia Care Coordinator Programs

Dementia UK

Patient Navigators UK

Dementia Australia

Health Navigator Australia

Dementia Navigators Australia

Dementia Navigators United States

Dementia Europe

Dementia Navigators Europe

Dementia Navigators Africa

https://scholar.google.com/ terms searched

Navigation Programs Dementia

Dementia Navigator

Patient Navigation Dementia

Patient Coordinator Dementia

Cognitive Dysfunction Patient Navigation

Cognitive Impairment Patient Navigation

Dementia Navigation

Dementia Coordination

Alzheimer’s Patient Navigation

Alzheimer’s Patient Coordination

Dementia Care Coordinator Programs

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses terms searched

Navigation Programs Dementia

Dementia Navigator

Patient Navigation Dementia

Patient Coordinator Dementia

Cognitive Dysfunction Patient Navigation

Cognitive Impairment Patient Navigation

Dementia Navigation

Dementia Coordination

Alzheimer’s Patient Navigation

Alzheimer’s Patient Coordination

Dementia Care Coordinator Programs

https://www.cadth.ca/ terms searched

Navigation Programs Dementia

Dementia Navigator

Patient Navigation Dementia

Patient Coordinator Dementia

Cognitive Dysfunction Patient Navigation

Cognitive Impairment Patient Navigation

Dementia Navigation

Dementia Coordination

Alzheimer’s Patient Navigation

Alzheimer’s Patient Coordination

Dementia Care Coordinator Programs

For dementia-specific organizations, we hand-searched websites using key terms. We examined the first 100 results per site (some searches had fewer than 100 results). These terms were: Navigation Programs, Dementia Navigator, Patient Navigation, Patient Coordinator Dementia, Cognitive Dysfunction Patient Navigation, Cognitive Impairment Patient Navigation, Dementia Navigation, Dementia Coordination, Alzheimer’s Patient Navigation, Alzheimer’s Patient Coordination, Dementia Care Coordinator Programs.

We searched the following organization websites:

Dementia UK: https://www.dementiauk.org/

Dementia Australia: https://www.dementia.org.au/

Alzheimer Society of Canada: https://alzheimer.ca/en

Alzheimer’s Association (United States): https://www.alz.org/

Appendix II: Data extraction instrument

| Author/year | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type of source/study design where applicable | |||

| Geographic location | |||

| Setting | |||

| Delivery format | |||

| Population/condition type | |||

| Team composition | |||

| Navigator title | |||

| Program description and services | |||

| Program barriers (where applicable) | |||

| Program facilitators (where applicable) |

Appendix III: Characteristics of included studies

| Author, year | Title | Type of source/study design (where applicable) | Geographic location | Setting | Delivery format | Population/condition | Team composition | Navigator title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amjad et al.,32 2018 | Health services utilization in older adults with dementia receiving care coordination: the MIND at Home trial | Randomized controlled trial | Baltimore, Maryland, US | Home and community | Phone and in person | 70 years and older, English-speaking, community residing in northwest Baltimore (28 postal codes), with a reliable study partner (ie, dyad); met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) criteria for dementia or cognitive disorder not otherwise specified, and had one or more unmet care needs on the Johns Hopkins Dementia Care Needs Assessment | Interdisciplinary team of nonclinical memory care coordinators linked to a registered nurse and a geriatric psychiatrist | Care coordinator |

| Bass et al.,59 2003 | The Cleveland Alzheimer’s managed care demonstration: outcomes after 12 months of implementation | Randomized controlled trial | Cleveland, Ohio, US | Home and community | Phone | People with memory problems and people with dementia (pre-diagnosis); 55 years and older; living in the community | Lay team of care consultants and trained volunteers | Care consultant |

| Bass et al.,45 2013 | Caregiver outcomes of Partners in Dementia Care: effect of a care coordination program for veterans with dementia and their family members and friends | Quasi-experimental study (participants were not randomized to intervention or control) | US (Boston, Massachusetts; Providence, Rhode Island; Houston, Texas; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; and Beaumont, Texas) | Home and community (based out of a Veterans Affairs center) | Phone, email, and mail | Veterans with dementia (aged 50 years and older) and their caregivers | Interdisciplinary team of care coordinators from Veterans Affairs and Alzheimer’s Association | Care coordinator |

| Bass et al.,46 2014 | A controlled trial of Partners in Dementia Care: veteran outcomes after six and twelve months | Randomized controlled trial | 5 regions in the US | Home and community (based out of a Veterans Affairs center) | Phone, email, mail, and in person | Veterans with dementia and their caregivers | Interdisciplinary team of care coordinators from Veterans Affairs and Alzheimer’s Association with administrative support | Care coordinator |

| Bass et al.,47 2015 | Impact of the care coordination program “Partners in Dementia Care” on veterans’ hospital admissions and emergency department visits | Randomized controlled trial | US (Boston, Massachusetts; Providence, Rhode Island; Houston, Texas; Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; and Beaumont, Texas) | Home and community | Phone, email, and mail | Veterans with dementia and their caregivers | Interdisciplinary team of care coordinators from Veterans Affairs and Alzheimer’s Association | Care coordinator |

| Bernstein et al.,22 2019 | The role of care navigators working with people with dementia and their caregivers | Qualitative exploratory study | California, Nebraska, and Iowa, US | Home and community | Phone and web-based | Dyads made up of people with dementia and their caregivers; with a diagnosis, speaking English, Spanish, or Cantonese | Interdisciplinary team of care team navigators, advanced practice clinical nurse, a social worker, and a pharmacist | Care team navigator |

| Bernstein et al.,39 2020 | Using care navigation to address caregiver burden in dementia: a qualitative case study analysis | Qualitative exploratory study | California and Nebraska, US | Home and community (based out of urban academic health centers) | Phone and web-based | Dyads made up of people with dementia and their caregivers; with a diagnosis, speaking English, Spanish, or Cantonese | Interdisciplinary team of care team navigators, advanced practice clinical nurse, a social worker, and a pharmacist | Care team navigator |

| Chen et al.,55 2020 | Effect of care coordination on patients with Alzheimer disease and their caregivers | Quasi-experimental study | Greenville, South Carolina, US | N/A | N/A | People with dementia and their caregivers | Interdisciplinary team included care coordinator and licensed social worker | Care coordinator |

| Dang et al.,57 2008 | Care coordination assisted by technology for multiethnic caregivers of persons with dementia: a pilot clinical demonstration project on caregiver burden and depression | Qualitative study | Miami, Florida, US | Home and community | Phone | Home-dwelling veterans over the age of 60 years, with a diagnosis of dementia or related disorders; caregivers were required to live with the veteran | Interdisciplinary team of nurse care coordinator and a support person, who also communicated with the care recipients’ providers | Care coordinator |

| Dementia Waikato,66 2017 | Dementia navigator service | Brochure | Waikato, New Zealand | Home and community | Phone and in person | People with dementia and caregivers, residing in the Waikato District Health Board area, dementia diagnosis required, must be eligible for public health services | Interdisciplinary team of registered nurses, occupational therapists, social workers, and dementia navigator | Support coordinator |

| Department of Veterans Affairs,67 2020 | Rural Interdisciplinary Team Training (RITT) dementia care coordinator program | Information sheet | US | Home and community | Phone and email | Caregivers of veterans with dementia | Interdisciplinary team of licensed clinical social workers and volunteers | Dementia care coordinator |

| Fæø et al.,53 2020 | The compound role of a coordinator for home-dwelling persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: qualitative study | Qualitative study | Norway | Home and community | Phone and in person | Dyads made up of people with dementia and their care partners, who lived at home | Clinical team of 2 specialist nurses acting as coordinators | Coordinator |

| Fortinsky et al.,65 2002 | Helping family caregivers by linking primary care physicians with community-based dementia care services: the Alzheimer’s Service Coordination Program | Mixed methods | Cleveland, Ohio, US | Home and community | Phone and in person | People with dementia and their caregivers | N/A | Service coordinator |

| Galik and Stefanacci,69 2019 | Improving care for patients with dementia: what to do before, during, and after a transition | Editorial | US | Home and community | N/A | People with dementia and their caregivers | Interdisciplinary team | Alzheimer’s patient navigation |

| Galvin et al.,56 2014 | Public–private partnerships improve health outcomes in individuals with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease | Cross-sectional, non-randomized research study | Missouri, US | Home and community | Phone and in person | People with dementia and their caregivers, diagnosis required | Interdisciplinary team of New York University researchers, the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, Area Agencies on Aging, and local Alzheimer’s Association Chapters | Project Learn MORE (Missouri Outreach and Referral Expanded) coordinator |

| Goeman et al.,63 2016 | Development of a model of dementia support and pathway for culturally and linguistically diverse communities using co-creation and participatory action research | Qualitative study using a co-creation and participatory action research approach | Australia | Home and community | Phone and in person | Culturally and linguistically diverse community members with cognitive impairment living in the community and their family or caregiver | Clinical team of nurses | Specialist dementia nurse |

| Husebo et al.,54 2020 | LIVE@Home.Path—innovating the clinical pathway for home-dwelling people with dementia and their caregivers: study protocol for a mixed methods, stepped-wedge, randomized controlled trial | Study protocol | 3 municipalities in Norway | Home and community | Phone and in person | Dyads made up of people with dementia and their care partners, who lived at home | Clinical team of 2 specialist nurses, acting as coordinators | Coordinator |

| Joels and van Pol,51 2014 | How to manage follow-up patients: Dementia Navigators | Report/presentation slides | Islington borough of London, UK | Home and community | Phone and in person | People with dementia and their informal caregivers | Interdisciplinary team of a full-time team leader with clinical and managerial responsibilities and 3 dementia navigators | Dementia navigator |

| Judge et al.,48 2011 | Partners in Dementia Care: a care coordination intervention for individuals with dementia and their family caregivers | Qualitative descriptive analysis | Huston, Texas and Boston, Massachusetts, US | Home and community | Phone | Veterans with dementia and their primary caregivers | Interdisciplinary team included the VA Dementia Care Coordinator who worked in the Veterans Affairs, and the Alzheimer’s Association Care Consultant who worked in the Alzheimer’s Association chapter | Care coordinator |

| Lee et al.,61 2014 | Integrating community services into primary care: improving the quality of dementia care | Qualitative exploratory study | Ontario, Canada | Community (based out of primary care clinic) | In person | People with mild cognitive impairment or dementia and their caregivers | Interdisciplinary team included a physician, nurse practitioner, registered nurse, social worker, occupational therapist, and pharmacist | Clinic coordinator |

| Liu et al.,68 2019 | Patient and caregiver outcomes and experiences with team-based memory care: a mixed methods study | Mixed methods | Southeastern US | Community (based out of memory clinic) | Phone and in person | People with dementia and other memory issues and their caregivers | Interdisciplinary team made up of a geriatric physician, nurse, nurse practitioner, and social worker who functioned as the dementia navigator | Dementia navigator |

| McAiney et al.,60 2012 | ‘Throwing a lifeline’: the role of First Link™ in enhancing support for individuals with dementia and their caregivers | Mixed methods | Ontario and Saskatchewan, Canada | Home and community | Phone | People with dementia and their caregiver | Lay team made up of First Link Coordinator who worked with Alzheimer Society and the family | First Link coordinator |

| Merrilees et al.,40 2020 | The Care Ecosystem: promoting self-efficacy among dementia family caregivers | Qualitative exploratory study | California, Nebraska, and Iowa, US | Home and community | Phone, email, mail, and in person | Dyads made up of people with dementia and caregivers | Interdisciplinary team made up of care team navigators, advanced practice nurse, social worker, and pharmacist | Care team navigator |

| Morgan et al.,49 2015 | A break-even analysis for dementia care collaboration: Partners in Dementia Care | Cost analysis | US | Home and community | Phone and email | Veterans with dementia and their caregivers | Interdisciplinary team made up of Veterans Health Administration Coordinator and Alzheimer’s Association coordinator | Alzheimer’s Association care coordinator |

| Morgan et al.,50 2019 | Does care consultation affect use of VHA versus non-VHA care? | Cross-sectional research study | 5 regions in the US | Home and community | Phone | Veterans with dementia and their primary caregivers | Interdisciplinary team made up of half-time Veterans Health Administration dementia care coordinator and a half-time Alzheimer’s Association care consultant | Alzheimer’s Association care coordinator |

| Possin et al.,41 2017 | Development of an adaptive, personalized, and scalable dementia care program: early findings from the Care Ecosystem | Pragmatic randomized controlled trial | US | Home and community | Phone, email, and in person | People diagnosed with dementia of any type by any medical provider; 45 years and older; Medicare- or Medicaid-enrolled or pending; residing in California, Nebraska, or Iowa; a caregiver who may or may not reside with the patient; and fluency in English, Spanish, or Cantonese | Interdisciplinary team made up of care team navigators, dementia specialist nurse, social worker, and pharmacist | Care team navigator |

| Possin et al.,42 2019 | Effect of collaborative dementia care via telephone and internet on quality of life, caregiver well-being, and health care use: the Care Ecosystem randomized clinical trial | Randomized controlled trial | California, Nebraska, and Iowa, US | Home and community (based out of urban academic health centers) | Phone, email, and mail | Dyads made up of people with dementia and their caregiver; diagnosis required; speaking either English, Spanish, or Cantonese, residing in Iowa, California, or Nebraska | Interdisciplinary team consisting of a care team navigator, advanced practice nurse, social worker, and pharmacist | Care team navigators |

| Rosa et al.,43 2019 | Variations in costs of a collaborative care model for dementia | Cost analysis | California, Nebraska, and Iowa, US | Home and community (based out of urban academic health centers) | Phone, email, and in person | Dyads of persons with dementia and their caregiver; diagnosis required; speaking either English, Spanish, or Cantonese, residing in Iowa, California, or Nebraska | Interdisciplinary team consisting of a care team navigator, advanced practice clinical nurse, social worker, and pharmacist | Care team navigators |

| Samus et al.,33 2014 | A multidimensional home-based care coordination intervention for elders with memory disorders: the Maximizing Independence at Home (MIND) pilot randomized trial | Randomized controlled trial | Baltimore, Maryland, US | Home and community | Phone, email, and in person | People with cognitive disorder, 70 years and older, English-speaking, living in the community, had a reliable study partner (dyad) | Interdisciplinary team made up of community workers (coordinators), registered nurse, and geriatric psychiatrist | Memory care coordinator |

| Samus et al.,34 2015 | A multipronged, adaptive approach for the recruitment of diverse community-residing elders with memory impairment: The MIND at Home experience | Descriptive analysis | Baltimore, Maryland, US | Home and community | Phone and in person | Community-residing people in northwest Baltimore (28 postal codes), 70 years and older, English-speaking, met criteria for dementia or cognitive disorder, and had a reliable study partner (dyad) | Interdisciplinary team made up of trained nonclinical community workers (ie, memory care coordinator), nurses, physicians (ie, geriatric psychiatrists), and occupational therapists | Memory care coordinator |

| Samus et al.,35 2017 | Comprehensive home-based care coordination for vulnerable elders with dementia: Maximizing Independence at Home-Plus—study protocol | Protocol for randomized controlled trial | US | Home and community | Phone and in person | People with dementia and their caregivers | Interdisciplinary made up of geriatric psychiatrist, registered nurse, occupational therapist, memory care coordinator | Memory care coordinator |

| Samus et al.,36 2018 | MIND at Home-streamlined: study protocol for a randomized trial of home-based care coordination for persons with dementia and their caregivers | Protocol for randomized controlled trial | Baltimore, Maryland, US | Home and community | Phone and in person | Community-residing people in northwest Baltimore (28 postal codes), 70 years and older, English-speaking, met criteria for dementia or cognitive disorder, and had a reliable study partner (dyad) | Interdisciplinary team made up of geriatric psychiatrist, registered nurse, occupational therapist, memory care coordinator | Memory care coordinator |

| Silverstein et al.,58 2015 | The Alzheimer’s Association Dementia Care Coordination program: a process evaluation, executive summary | Mixed methods | Massachusetts and New Hampshire, US | Community | In person | People with dementia and their families | N/A | Care consultant |

| Tanner et al.,37 2015 | A randomized controlled trial of a community-based dementia care coordination intervention: effects of MIND at Home on caregiver outcome | Randomized controlled trial | Baltimore, Maryland, US | Home and community | Phone and in person | Community-residing people in northwest Baltimore (28 postal codes), 70 years and older, English-speaking, met criteria for dementia or cognitive disorder, and had a reliable study partner (dyad) | Interdisciplinary team made up of geriatric psychiatrist, registered nurse, occupational therapist, memory care coordinator | Memory care coordinator |

| Taylor et al.,62 2015 | The Primary Care Navigator programme for dementia: benefits of alternative working models | Report using qualitative assessment | Gateshead and Halton, UK | Community (based out of a general practitioner practice and a well-being enterprises community interest company) | Phone and in person | People with dementia, pre- and post-diagnosis | Clinical; each site organized differently. At Gateshead, 2 people shared the primary care navigator role, switching roles as health care assistant and primary care navigator weekly. They worked with a clinical team, which included doctors, a registrar, nurse practitioners, and a nursing team. At Halton, 10 community well-being officers acted as primary care navigators. They had clinical backgrounds. They partnered with 17 practices. | Primary care navigator |

| Tjia,44 2019 | A telephone-based dementia care management intervention-finding the time to listen | Editorial/ invited commentary | California, Nebraska, and Iowa, US | Home and community (based out of urban academic health centers) | Phone and email | Dyads made up of people with dementia and their caregivers; diagnosis required, speaking English, Spanish or Cantonese, and residing in Iowa, California, or Nebraska | Interdisciplinary team made up of a care team navigator, dementia specialist nurse, social worker, and pharmacist | Care team navigators |

| Willink et al.,38 2020 | Cost-effective care coordination for people with dementia at home | Prospective, quasi-experimental intervention trial design | Baltimore and Maryland suburban District of Columbia, US | Home and community | Phone and in person | Community-residing people in northwest Baltimore (28 postal codes), 70 years and older, English-speaking, met criteria for dementia or cognitive disorder, and had a reliable study partner (dyad) | Interdisciplinary team made up of geriatric psychiatrist, registered nurse, occupational therapist, memory care coordinator | Memory care coordinator |

| Wood et al.,52 2017 | A holistic service for everyone with a dementia diagnosis (innovative practice) | Report | Islington borough of London, UK | Home and community | Phone, mail, and in person | People with dementia and their caregivers | Interdisciplinary team made up of dementia navigators, 3 full-time assistant practitioners, and specialist practitioner as team leader | Dementia navigators |

| Xiao et al.,64 2016 | The effect of a personalized dementia care intervention for caregivers from Australian minority groups | Randomized controlled trial | Adelaide, South Australia | Home and community | Phone and in person | Dyads made up of people with dementia and their caregivers; caregivers were from a minority group, living at home | Interdisciplinary team made up of 8 care coordinators, which included a registered nurse, a social worker, and 6 Community Home Care Certificate holders | Care coordinator |

N/A, not applicable.

Appendix IV: Barriers, facilitators, and descriptions of included studies

| Author, year | Title | Program description and services | Program barriers (barriers to implementation or delivery) | Program facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amjad et al.,32 2018 | Health services utilization in older adults with dementia receiving care coordination: the MIND at Home trial | Maximizing Independence (MIND) at Home’s primary goals were to delay transition from the home and to reduce unmet care needs. The secondary goals included improving quality of life, decreasing neuropsychiatric symptoms, and reducing depression. The program provided services to clients, such as resource referrals, identifying and addressing potential environmental safety hazards, dementia care education, behavior management skills training, informal counseling, and problem-solving. They handled care needs, such as evaluation/diagnosis (primary care provider or specialist referral for dementia evaluation), treatment of cognitive symptoms and behavior management, referral to Alzheimer’s Association, medication administration, general medical/health care and safety, assistance with daily activities, legal issues/advance care planning, caregiver education, caregiver referrals, caregiver mental health care, and caregiver general medical/health care. | MIND care coordinators had difficulties establishing contacts with the respective health providers on behalf of intervention participants. | Integration, communication, and collaboration between the MIND care team and clients’ health providers. |

| Bass et al.,59 2003 | The Cleveland Alzheimer’s managed care demonstration: outcomes after 12 months of implementation | Care consultants worked with families to help identify personal strengths and resources within the family system, health plan, and community to make an individual care plan. Often this included using other association services, such as education and training programs, support groups, a respite reimbursement program, and a nationwide program to return wanderers safely home. The program’s goal was to provide tools to enhance patients’ and caregivers’ competence and self-efficacy. Consultants also provided information about available community services, facilitated decisions about how to best utilize and apply for these services, and contacted service agencies on behalf of patients and caregivers. Standardized protocol for service delivery included conducting a structured initial assessment, identifying problems or challenges, and developing strategies for using personal, family, and community resources. | — | Collaboration and partnership with Alzheimer’s Association. |