This cohort study investigates whether white matter hyperintensity in individuals with Alzheimer disease is more likely to be associated with neurodegeneration and parenchymal and vessel amyloidosis than with systemic vascular risk.

Key Points

Question

Is magnetic resonance imaging–visible white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume in Alzheimer disease (AD) more likely to be associated with neurodegenerative processes or systemic vascular risk factors?

Findings

In this cohort study using cross-sectional and longitudinal data from cohorts with autosomal dominant and late-onset AD (1141 individuals; 3960 MRI sessions), AD-intrinsic processes of gray matter atrophy and parenchymal and vessel amyloidosis were more likely to be associated with WMH volume compared with systemic vascular risk factors.

Meaning

The findings suggest that in adults with AD, WMH volume may not reflect mixed vascular pathology secondary to elevated systemic vascular risk but might be associated with amyloidosis and neurodegeneration.

Abstract

Importance

Increased white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume is a common magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) finding in both autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease (ADAD) and late-onset Alzheimer disease (LOAD), but it remains unclear whether increased WMH along the AD continuum is reflective of AD-intrinsic processes or secondary to elevated systemic vascular risk factors.

Objective

To estimate the associations of neurodegeneration and parenchymal and vessel amyloidosis with WMH accumulation and investigate whether systemic vascular risk is associated with WMH beyond these AD-intrinsic processes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study used data from 3 longitudinal cohort studies conducted in tertiary and community-based medical centers—the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN; February 2010 to March 2020), the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI; July 2007 to September 2021), and the Harvard Aging Brain Study (HABS; September 2010 to December 2019).

Main Outcome and Measures

The main outcomes were the independent associations of neurodegeneration (decreases in gray matter volume), parenchymal amyloidosis (assessed by amyloid positron emission tomography), and vessel amyloidosis (evidenced by cerebral microbleeds [CMBs]) with cross-sectional and longitudinal WMH.

Results

Data from 3960 MRI sessions among 1141 participants were included: 252 pathogenic variant carriers from DIAN (mean [SD] age, 38.4 [11.2] years; 137 [54%] female), 571 older adults from ADNI (mean [SD] age, 72.8 [7.3] years; 274 [48%] female), and 318 older adults from HABS (mean [SD] age, 72.4 [7.6] years; 194 [61%] female). Longitudinal increases in WMH volume were greater in individuals with CMBs compared with those without (DIAN: t = 3.2 [P = .001]; ADNI: t = 2.7 [P = .008]), associated with longitudinal decreases in gray matter volume (DIAN: t = −3.1 [P = .002]; ADNI: t = −5.6 [P < .001]; HABS: t = −2.2 [P = .03]), greater in older individuals (DIAN: t = 6.8 [P < .001]; ADNI: t = 9.1 [P < .001]; HABS: t = 5.4 [P < .001]), and not associated with systemic vascular risk (DIAN: t = 0.7 [P = .40]; ADNI: t = 0.6 [P = .50]; HABS: t = 1.8 [P = .06]) in individuals with ADAD and LOAD after accounting for age, gray matter volume, CMB presence, and amyloid burden. In older adults without CMBs at baseline, greater WMH volume was associated with CMB development during longitudinal follow-up (Cox proportional hazards regression model hazard ratio, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.72-4.03; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings suggest that increased WMH volume in AD is associated with neurodegeneration and parenchymal and vessel amyloidosis but not with elevated systemic vascular risk. Additionally, increased WMH volume may represent an early sign of vessel amyloidosis preceding the emergence of CMBs.

Introduction

The finding of increased white matter hyperintensity (WMH) volume on routine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in individuals being evaluated for Alzheimer disease (AD) is both common and nonspecific.1,2,3 Increased WMH in the absence of MR-visible strokes or hemorrhage is observed in a wide variety of conditions ranging from neurodegenerative to inflammatory and cerebrovascular syndromes, reflecting the broad set of possible etiologies underlying WMH appearance and accumulation. White matter hyperintensities are often presumed to represent small-vessel ischemic brain injury due to underlying vascular risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia.4 White matter hyperintensities are also commonly seen in individuals diagnosed with both sporadic, late-onset Alzheimer disease (LOAD) and autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease (ADAD).5,6,7 However, despite the consistent finding that many individuals with AD have elevations in WMH volume compared with age-matched control individuals,8,9 the interpretation of WMH in AD remains controversial. The presence of periventricular WMH is often attributed to traditional cardiovascular risk factors.10 In older adults and people with LOAD, the presence or absence of WMH is used to support or argue against a diagnosis of mixed vascular and neurodegenerative pathologies. This interpretation of WMH as a sequela of elevated systemic vascular risk has been influential, forming the basis of clinical recommendations and informing diagnostic criteria for vascular dementia and vascular cognitive impairment.11

More recent studies suggest that WMH may also be associated with amyloid accumulation and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA),12,13 though simultaneous assessment of both of these possible causes of WMH has rarely been performed. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy is clinically diagnosed by detecting hemorrhagic lesions—most commonly, cerebral microbleeds (CMBs).14 However, these hemorrhagic lesions (including CMBs) are a relatively late consequence of vessel amyloidosis, and detection of CAA physiology in the pre-CMB phase of the disease remains challenging. A study15 of autosomal dominant forms of CAA, in which the disease manifests in relatively young adults with lower levels of systemic vascular risk, showed that white matter injury began early in the course of the disease, with WMH growth evident more than a decade prior to the appearance of CMBs or other hemorrhagic lesions. It has also been hypothesized that WMH partly represents a consequence of cortical atrophy and the resultant downstream axonal loss it generates.2,3,16

A major challenge in assessing the etiology of WMH is that multiple potential causes of WMH growth are often present within an individual, especially in older individuals on the AD continuum. Simultaneously assessing these causes of WMH growth requires comprehensive imaging and clinical data to be available, including clinical data on vascular risk factors, AD biomarkers, MRI, and positron emission tomography (PET). In the present study, we leveraged multimodal data from 3 large ADAD and LOAD cohorts that prospectively collected longitudinal measures of vascular, neurodegenerative, and amyloid-related processes to test the hypothesis that AD-intrinsic processes may be more likely to be associated with WMH in AD compared with traditional systemic vascular risk factors.

Methods

Participants

Participants in this cohort study provided written informed consent prior to the performance of any study procedures, as mandated by human participants research committees at each participating tertiary and community-based medical center. The study was approved by all participating sites. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Study

We evaluated participants in the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN) observational study using previously described clinical, neuropsychological, and imaging assessments17 with data from the 12th DIAN Data Freeze (February 2010 to March 2020). Individuals bearing the APP E693Q (Dutch-type CAA) sequence variation were excluded. Carriers of all other APP, PSEN1, and PSEN2 pathogenic variants with available neuroimaging and clinical data were included. Longitudinal analyses were performed in ADAD carriers with at least 1 follow-up MRI and clinical visit.

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Study

We evaluated individuals from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI 1, ADNI GO, ADNI 2, and ADNI 3 phases) with available clinical and neuroimaging data from July 2007 to September 2021. All included ADNI participants had at least 1 follow-up MRI visit and clinical data.

Harvard Aging Brain Study

We evaluated individuals from the Harvard Aging Brain Study (HABS) with available clinical and neuroimaging data (September 2010 to December 2019). All participants did not have cognitive impairment at study entry and had at least 1 available follow-up visit.

Image Acquisition and Processing

MRI

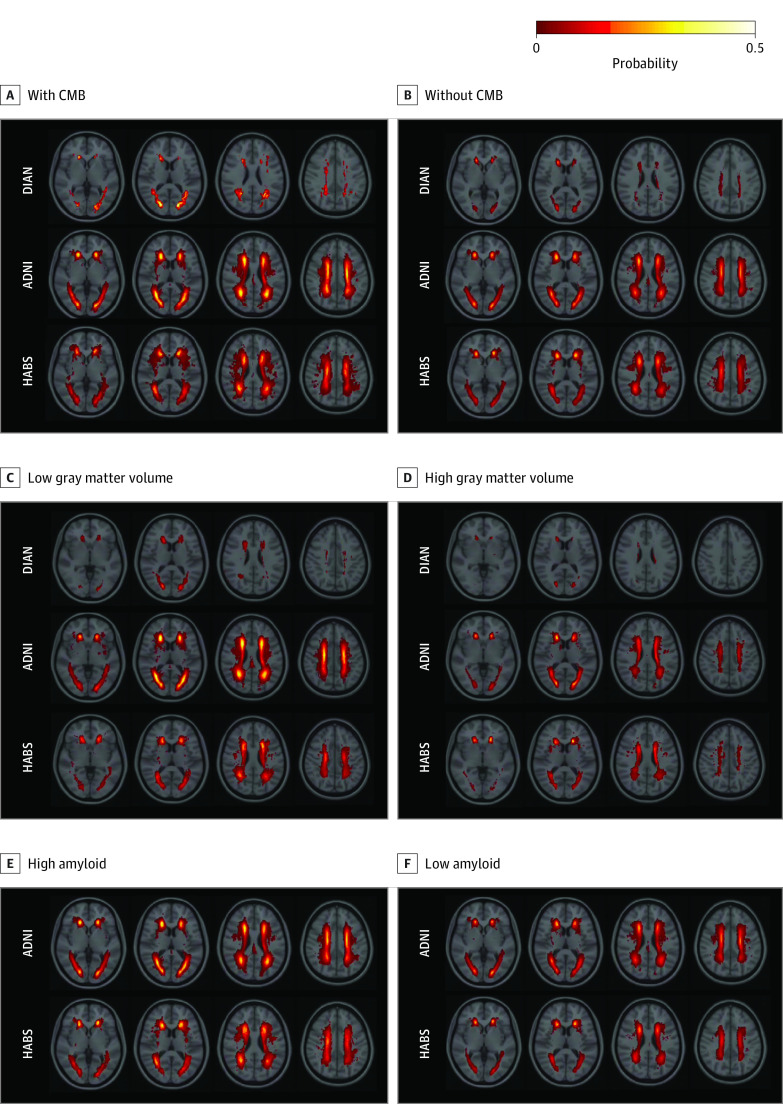

The following MRIs (3T) were used: T1-weighted magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), and susceptibility-weighted MRI or T2*-weighted gradient echo images. We segmented WMH on FLAIR images using the HyperMapp3r algorithm.18,19 For illustration purposes, WMH masks were coregistered to the MNI standard space using the FLIRT tool, version FSL6.0.1.20 Subsequently, a map indicating the probability of recognizing WMH in a given voxel was generated using baseline data (WMH probability map) to visualize the patterns and volume of WMH in different groups.

Gray matter (GM) volume and intracranial volume were assessed using FreeSurfer.21 White matter hyperintensity and GM volume were normalized to intracranial volume prior to entry into models. Normalized WMH volume was log transformed to reduce skewness. Lobar CMB burden was assessed visually on susceptibility-weighted or T2*-weighted gradient echo images by experienced radiologists (including K.K., G.M.P., and C.R.J.) at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, for DIAN and ADNI22 and at Massachusetts General Hospital for HABS.23 Small lesions (≤10 mm) that were dissociable from small vessels were counted as definite microbleeds.

Amyloid PET

Detailed amyloid PET protocols have been previously described for DIAN,24 ADNI,25 and HABS.26 Amyloid PET was performed using 11C–Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) in DIAN and HABS and 18F–florbetapir in ADNI. In ADNI, florbetapir measurements were represented as a cortical summary standard uptake value ratio (SUVr) across a composite of lateral and medial frontal, anterior, and posterior cingulate, lateral parietal, and lateral temporal regions. The whole cerebellum served as the reference region. Data were downloaded from the University of Southern California’s Laboratory for Neuroimaging website for ADNI participants.27 As in prior work from HABS,28 PiB PET measurements were represented as a distribution volume ratio across a composite of frontal, lateral temporal, parietal, and retrosplenial regions, with cerebellar GM serving as the reference region. As in ADNI, HABS participants were grouped into high and low amyloid groups using previously described, cohort-specific cutoff values. Similar processing was performed in DIAN, and we obtained cortical mean SUVr values from PiB PET. As the application of LOAD-based thresholds for amyloid positivity in ADAD may be complicated by variant-level differences in amyloid PET signal, PiB SUVr was used as a continuous variable in DIAN analyses.29

Statistical Analysis

Statistical testing was conducted in R, version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Cross-sectional models used linear regression to examine the association of CMBs (presence or absence), GM volume, and age with WMH volume at baseline. Interactions of amyloid group with GM volume were examined and retained only if statistically significant. Follow-up sensitivity analyses examined the potentially additive effect of an algorithmic vascular risk score (Framingham Heart Study cardiovascular disease [FHS-CVD] risk score30) in the model. To assess whether associations of CMBs, GM, and age with WMH volumes changed in the higher ranges of systemic vascular risk, cross-sectional models were rerun in the highest tertile of FHS-CVD risk scores for each cohort. Lastly, we performed separate analyses in which a 3-level, pseudoordinal approach to categorizing CMB burden—no CMBs, 1 recognized CMB (consistent with possible CAA), and 2 or more recognized CMBs (consistent with probable CAA)—was used in lieu of CMB presence or absence in statistical models.

For longitudinal analyses, WMH and GM volume rates of change were extracted from linear mixed-effects models (lme4 package), and associations of CMBs (presence or absence), GM volume rate of change, and age with the WMH volume rate of change were assessed. As in cross-sectional analyses, the interaction of amyloid group and GM volume was assessed and retained if significant. Paralleling cross-sectional analyses, follow-up sensitivity analyses were performed to assess pseudoordinal CMB scaling and the baseline FHS-CVD risk score as a factor associated with WMH rate of change as well as analyses restricted to the highest tertile of FHS-CVD risk scores in each cohort. Lastly, to assess the association between baseline WMH burden and the development of CMBs during longitudinal follow-up, a survival analysis (survival package) was performed. Survival curves were depicted using the Kaplan-Meier method. Two-sided P < .05 was considered significant.

Results

Data from 3960 MRI sessions among 1141 participants were included: 252 participants in the DIAN cohort (mean [SD] age, 38.4 [11.2] years; 137 [54%] female and 115 [46%] male; mean [SD] follow-up, 2.7 [2.5] years), 571 in the ADNI cohort (mean [SD] age, 72.8 [7.3] years; 274 [48%] female and 297 [52%] male; mean [SD] follow-up, 3.7 [2.8] years), and 318 in the HABS cohort (mean [SD] age, 72.4 [7.6] years; 194 [61%] female and 124 [39%] male; mean [SD] follow-up, 5.2 [3.7] years). In the ADNI cohort, baseline clinical diagnoses included cognitive unimpairment (140 [25%]), subjective memory complaint (27 [5%]), early mild cognitive impairment (202 [35%]), late mild cognitive impairment (128 [22%]), and dementia (74 [13%]). The Table summarizes the clinical characteristics of the DIAN, ADNI, and HABS cohorts used in primary analyses. eTable 1 in Supplement 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the groups with the highest-tertile FHS-CVD risk scores in DIAN, ADNI, and HABS—a subgroup used in sensitivity analyses (eTables 2-7 in Supplement 1).

Table. Participant Demographics and Study Information for the DIAN, ADNI, and HABS Baseline Data.

| Characteristic | Participantsa | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| DIAN (n = 252) | ADNI (n = 571) | HABS (n = 318) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 38.4 (11.2) | 72.8 (7.3) | 72.4 (7.6) |

| Estimated time to symptom onset, mean (SD), y | −8.3 (11.3) | NA | NA |

| APOE4 | 74 (29) | 270 (47) | 87 (28) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 137 (54) | 274 (48) | 194 (61) |

| Male | 115 (46) | 297 (52) | 124 (39) |

| Educational level, mean (SD), y | 14 (3) | 16 (3) | 16 (3) |

| Cerebral microbleeds | 24 (10) | 44 (8) | 74 (27) |

| CDR score ≥1 | 78 (31) | 328 (57) | 3 (1) |

| Dementia diagnostic group | 46 (18) | 74 (13) | 0 |

| High amyloid burden | NA | 274 (50) | 119 (38) |

| WMH volume, mean (SD)b | 2 (6) | 9 (9) | 5 (9) |

| GM volume, mean (SD)b | 534 (46) | 360 (29) | 500 (27) |

| Follow-up time, mean (SD), y | 2.7 (2.5) | 3.7 (2.8) | 5.2 (3.7) |

| FHS-CVD risk score, mean (SD) | 5 (5) | 38 (22) | 30 (18) |

Abbreviations: ADNI, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; APOE4, apolipoprotein E4; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; DIAN, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network; FHS-CVD, Framingham Heart Study cardiovascular disease; GM, gray matter; HABS, Harvard Aging Brain Study; NA, not applicable; WMH, white matter hyperintensity.

Data are presented as the number (percentage) of patients unless otherwise indicated.

Normalized to intracranial volume = 1300 cm3.

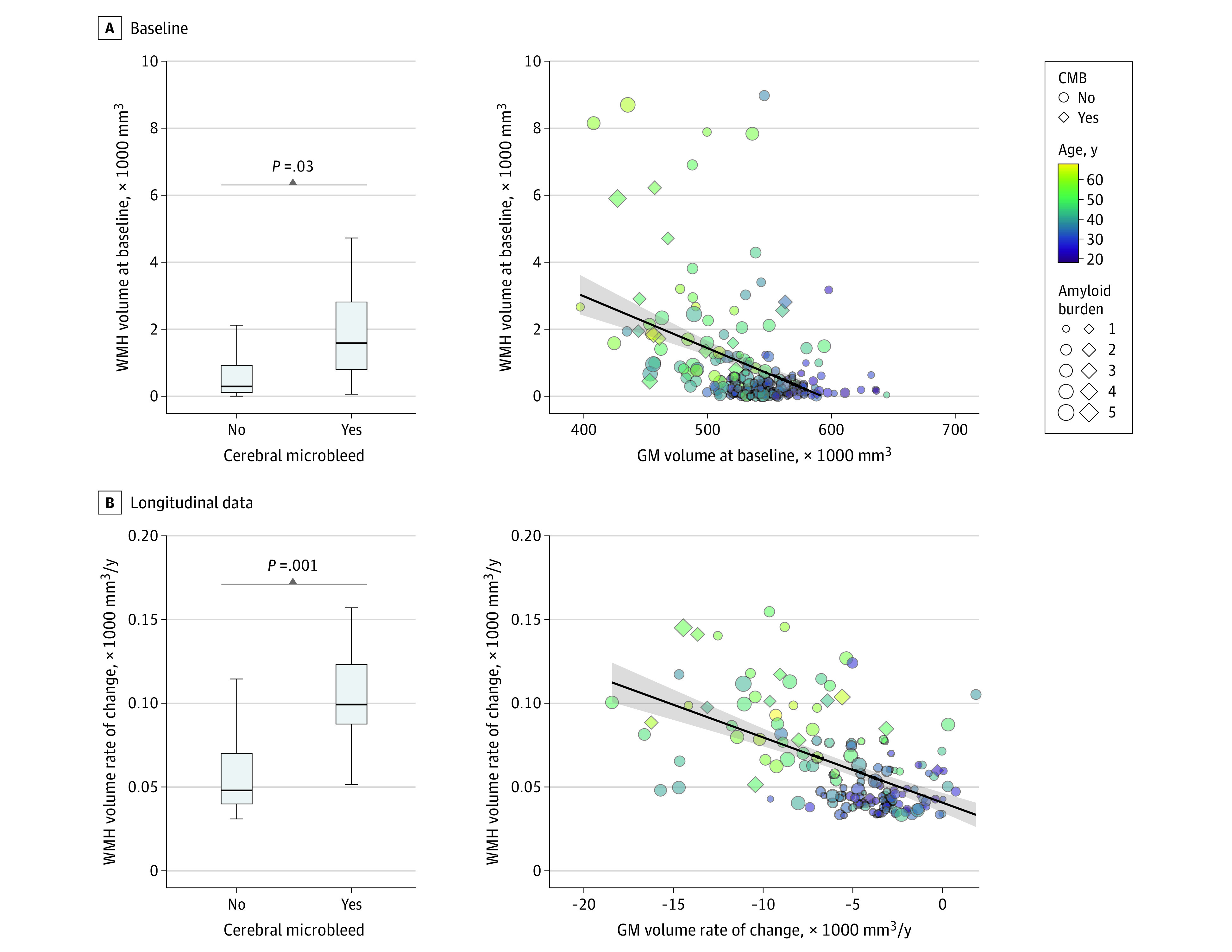

DIAN Study

Baseline WMH volume was greater in ADAD pathogenic variant carriers who had at least 1 baseline CMB (t = 2.1; P = .03) (Figure 1A and B), were older (ie, closer to their estimated age of symptom onset) (t = 4.7; P < .001), and had lower GM volume (t = −2.3; P = .02) (Figure 1C and D and Figure 2A). Sensitivity analyses indicated that including the FHS-CVD risk score as a factor did not change the associations between WMH, age, and GM volume, but there was no longer an association of CMB with WMH volume (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). The FHS-CVD risk score was not associated with cross-sectional WMH volume (t = 0.9; P = .30). Similarly, an association between GM volume and WMH was observed when restricting analyses to participants with higher levels of vascular risk (eTable 2 in Supplement 1).

Figure 1. Probability Maps of White Matter Hyperintensities for Individuals With or Without Cerebral Microbleeds (CMBs), With Low or High Gray Matter Volume, and With Low or High Amyloid Burden.

Individual white matter hyperintensity maps were coregistered to the MNI space to generate these probability maps.20 ADNI indicates Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; DIAN, Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network; and HABS, Harvard Aging Brain Study.

Figure 2. Association of Cerebral Microbleeds (CMBs) and Gray Matter (GM) Volume With White Matter Hyperintensity (WMH) Volume in Carriers of Autosomal Dominant Alzheimer Disease Sequence Variations.

In the box and whisker plots, the horizontal bar inside the box indicates the median, the box starts at the first quartile (bottom) and ends at the third (top), and the limit lines indicate minimum (lower line) and maximum (upper line) values. Amyloid burden indicates the composite amyloid positron emission tomography standard uptake value ratio.

Longitudinal increases in WMH among ADAD pathogenic variant carriers with CMBs were greater than among carriers of pathogenic variants without CMBs (t = 3.2; P = .001). In addition, a higher GM volume rate of change (t = −3.1; P = .002) and older age (t = 6.8; P < .001) were associated with increasing WMH volume in longitudinal MRI data (Figure 2B). The FHS-CVD risk score (t = 0.7; P = .40) did not alter the associations of CMB and GM atrophy with longitudinal WMH volume (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Associations of age and GM volume rate of change with WMH rate of change remained similar when restricting the analysis to participants in the highest tertile of FHS-CVD risk scores for the cohort, but CMB associations with WMH rate of change were not present (eTable 3 in Supplement 1). Follow-up sensitivity analyses were also performed to assess whether CMB associations with WMH were different in individuals with no CMBs, 1 CMB (possible CAA), or 2 or more recognized CMBs (probable CAA). In both cross-sectional and longitudinal neuroimaging data from DIAN, presence of 1 CMB was not associated with WMH but presence of 2 or more recognized CMBs was associated with WMH (probable CAA) (eTables 2 and 3 in Supplement 1).

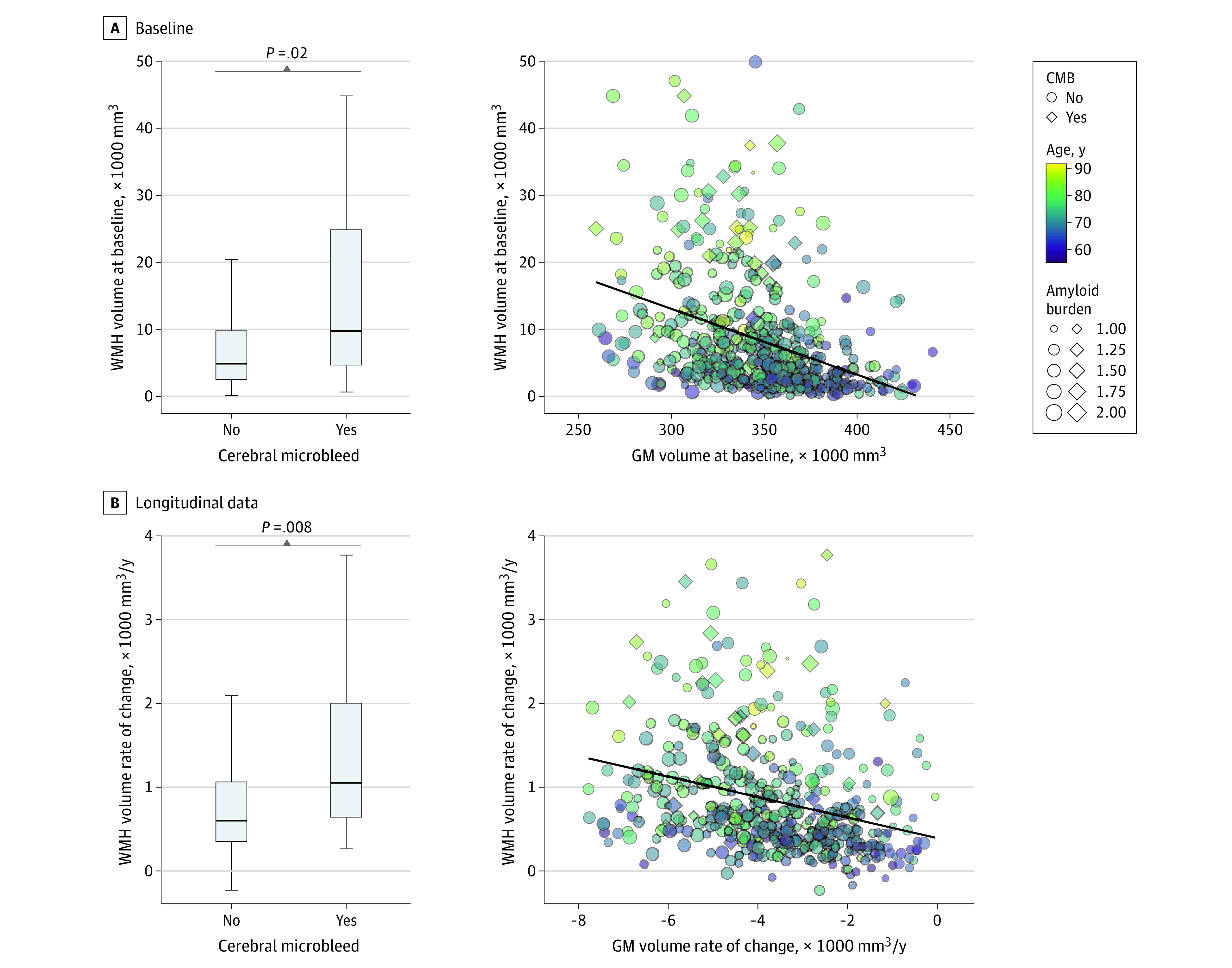

ADNI Study

We next examined whether similar associations between amyloidosis and GM volume with WMH volume were observable in older adults from ADNI. Similar to results for ADAD, cross-sectional WMH volume was greater in older adults with CMB than in those without (t = 2.3; P = .02) (Figure 1A and B). We also observed that WMH volume was associated with GM volume (t = −6.8; P < .001) (Figure 1C and D), older age (t = 10.5; P < .001) (Figure 3A), and higher levels of amyloid positivity (t = 2.2; P = .03) (Figure 1E and F). Including FHS-CVD risk scores in cross-sectional models did not alter the associations of GM volume and age with WMH, but there were no associations of CMB and amyloid group with cross-sectional WMH in these models. The FHS-CVD risk score was not associated with cross-sectional WMH (t = 1.6; P = .10) after accounting for GM volume, CMB, and age. We observed similar results when analyses were restricted to ADNI participants in the highest tertile of FHS-CVD risk scores (eTable 4 in Supplement 1).

Figure 3. Association of Cerebral Microbleeds (CMBs) and Gray Matter (GM) Volume With White Matter Hyperintensity (WMH) Volume in Older Adults From the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative.

In the box and whisker plots, the horizontal bar inside the box indicates the median, the box starts at the first quartile (bottom) and ends at the third (top), and the limit lines indicate minimum (lower line) and maximum (upper line) values. Amyloid burden indicates the composite amyloid positron emission tomography standard uptake value ratio.

Consonant patterns of association were observed in longitudinal data from ADNI. Specifically, older adults with CMB demonstrated greater longitudinal increases in WMH volume compared with those without CMB (t = 2.7; P = .008). Longitudinal WMH growth was associated with progressive GM atrophy (t = −5.6; P < .001), older age (t = 9.1; P < .001), and amyloid positivity (t = 2.3; P = .02) (Figure 3B). When including FHS-CVD risk score as a factor or restricting the analysis to only individuals in the highest tertile of FHS-CVD risk scores, there was no association between amyloid grouping and WMH rate of change but there were associations of CMB, GMV rate of change, and age with WMH rate of change. Additionally, the FHS-CVD risk score was not associated with WMH volume rate of change (t = 0.6; P = .50) (eTable 5 in Supplement 1). In both cross-sectional and longitudinal neuroimaging data from ADNI, presence of 1 CMB was not associated with WMH but presence of 2 or more recognized CMBs was associated with WMH (eTables 4 and 5 in Supplement 1).

HABS

Similar to results in ADNI and DIAN, WMH volume in HABS participants was greater in older adults with CMBs than in those without (t = 2.2; P = .02) (Figure 1A and B); WMH volume was also associated with the interaction of GM volume and amyloid group (t = −2.1; P = .04) (Figure 1C through F) and older age (t = 5.4; P < .001) (eFigure in Supplement 1). Including the FHS-CVD risk score (t = 1.6; P = .10) did not alter the associations of GM volume and age with WMH but there was no longer an association of CMB with WMH (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). When restricting the analysis to the highest FHS-CVD tertile group from HABS, cross-sectional WMH volume was associated only with older age (eTable 6 in Supplement 1). Lastly, presence of 1 CMB was not associated with WMH, but presence of 2 or more recognized CMBs was associated with WMH (eTable 6 in Supplement 1).

Similar to the cross-sectional analyses, the interaction of amyloid group with GM volume rate of change (t = −2.2; P = .03) and older age (t = 5.4; P < .001) were significantly associated with WMH rate of change (eFigure in Supplement 1) in longitudinal analyses. Follow-up sensitivity analyses including FHS-CVD risk score as a factor demonstrated no association between baseline FHS-CVD risk score and WMH rate of change (t = 1.8; P = .06), with other outcomes unchanged. Restricting the analysis to HABS participants in the highest tertile of FHS-CVD risk scores, WMH volume rate of change was significantly associated with older age only (eTable 7 in Supplement 1). Notably, the association with CMBs was omitted in longitudinal analyses from HABS because longitudinal data on CMBs in HABS participants (beyond the study baseline) were not available.

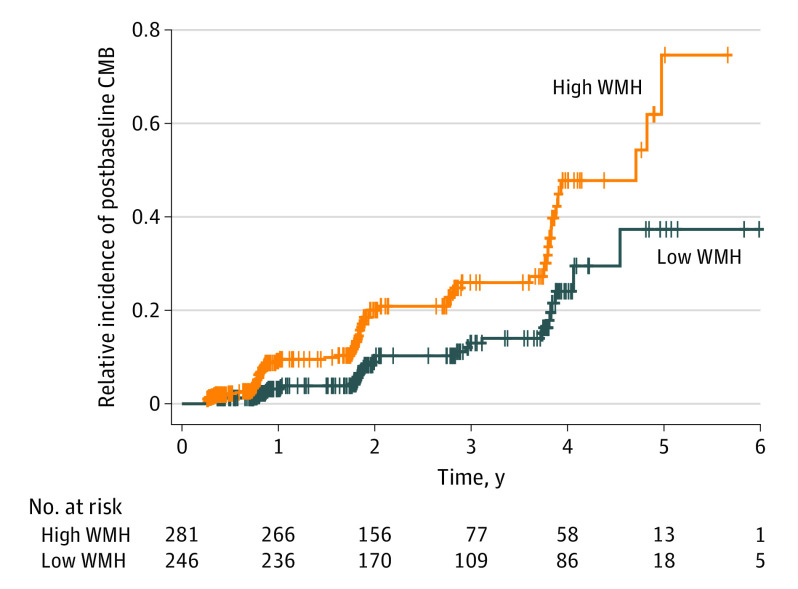

Emergence of CMBs in ADNI

Lastly, building on the observation that individuals with increased WMH volume were more likely to have CMBs at study entry, we examined whether a higher baseline WMH burden was associated with the emergence of CMBs during longitudinal follow-up in the 527 ADNI participants (92%) who did not have CMBs at baseline. Of these 527 participants, 100 individuals (19%) developed at least 1 CMB during follow-up visits (CMB-emergent group) (eTable 8 in Supplement 1). Individuals with a WMH volume above the median at baseline had a higher risk of developing CMBs during follow-up visits (hazard ratio, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.72-4.03; P < .001) (Figure 4) after controlling for age and GM volume. Including FHS-CVD risk score and amyloid burden did not alter these findings (eTable 9 in Supplement 1).

Figure 4. Emergence of Cerebral Microbleeds (CMBs) for Alzheimer's DIsease Neuroimaging Initiative Participants Without CMBs at Baseline.

Cox proportional hazards regression model hazard ratio, 2.63; 95% CI, 1.72-4.03; P < .001. WMH indicates white matter hyperintensity.

Discussion

While increased WMH volume is a common MRI finding in individuals on an AD trajectory, the interpretation and diagnostic implications of elevated WMH volume in AD remain ambiguous due to the potential influence of a broad set of vascular and neurodegenerative factors on WMH growth. Though WMH in AD is often interpreted in the context of small-vessel ischemic changes secondary to systemic vascular risk factors (mixed vascular pathology), the findings of this study suggest that WMH is more likely to be associated with the AD-intrinsic processes of parenchymal and vessel amyloidosis (ie, CAA) and degeneration of cerebral GM than with traditional systemic vascular risk factors. These findings were supported by the examination of 3 complementary data sets with available AD biomarkers, clinical data, and longitudinal neuroimaging data: a relatively young cohort with high rates of AD-related GM atrophy and CAA, low vascular risk, and limited potential for other, non-AD age-related pathologies (ADAD carriers in the DIAN cohort) and 2 cohorts of older adults with roughly average levels of vascular risk for their age (some with preclinical or symptomatic LOAD) and higher potential for comorbid, non-AD pathologies31 (ADNI and HABS). Together, these findings suggest that elevated WMH volume in ADAD and LOAD should be considered in the larger context of neurodegeneration and as a possible reflection of CAA progression even in individuals without manifest CMBs. Conversely, these findings also suggest that the absence of elevated WMH in older adults with elevated systemic vascular risk should not necessarily decrease suspicion of vascular contributions to cognitive decline.

The observation that progressive CAA pathophysiology may be associated with worsening WMH is consistent with recent work from our group15 that examined white matter disruption in individuals with autosomal dominant, Dutch-type CAA due to the APP E693Q missense sequence variation. This prior work in Dutch-type CAA demonstrated that white matter injury was readily observable a decade or more prior to the emergence of CMBs or symptomatic hemorrhage in this population.15 This was seen in both cross-sectional and longitudinal data from Dutch-type CAA carriers, similar to what was observed in the current study for both ADAD and LOAD.

In this study, systemic vascular risk was not significantly associated with cross-sectional or longitudinal WMH volume after accounting for age, the presence of CMBs, amyloid burden, and GM atrophy. Though the lack of independent associations between vascular risk and WMH burden is somewhat surprising, this result is consistent with prior reports that vascular risk factors explain only 1% to 2% of the variance in WMH.32,33 The presence and progression of WMH in individuals with ADAD and Dutch-type CAA7,15—both relatively young populations with low levels of vascular risk—provides a unique channel of evidence suggesting that amyloid-related disease processes are associated with higher WMH volume even in the relative absence of elevated systemic vascular risk. Notably, the pattern of results seen in this study is also consistent with neuropathological studies demonstrating lesser likelihood of an association of WMH volume with vascular risk factors but greater likelihood of an association with AD pathology, especially prior work showing that WMH is associated with elevated amyloid burden in older adults.13,34

Limitations

This study has limitations. Importantly, the difference in effect sizes for the associations of age, GM atrophy, amyloid burden, and CMB with WMH volume accumulation needs to be interpreted with caution as CMBs (and amyloid in ADNI and HABS) were modeled as categorical variables, diminishing their statistical power relative to GM volume, which was modeled as a continuous variable. More importantly, since the emergence of CMBs is a relatively late and stochastic event in the progression of CAA, it is likely that many individuals in the CMB-negative group had latent CAA physiology that had not (yet) manifested as CMBs or symptomatic hemorrhage. We observed that 19% of the individuals from ADNI who did not have CMBs at baseline developed CMBs during longitudinal follow-up (mean, 3.7 years). The potential for latent CAA physiology in the CMB-negative group cannot account for the association between CMBs and WMH seen in this study, but it may have led to diminished effect sizes.

Certain additional limitations need to be considered in interpreting the results of this study. We did not include tau burden in our analyses, as baseline tau PET imaging was not available for many participants. Although cross-sectional data have shown no associations between WMH and tau burden,34 future research is needed to investigate the role of tau accumulation in WMH accumulation given the association between tau accumulation and GM atrophy.35,36 Importantly, these results and conclusions need to be considered in the context of the study populations included. As expected, the relatively young participants in DIAN (mean age, 38.4 years) had low levels of vascular risk.37 Older participants in ADNI and HABS had roughly average vascular risk for their age38 and therefore had a substantial potential to show correlations between systemic vascular risk and WMH. However, both ADNI and HABS likely underrepresent individuals in the highest range of vascular risk. This is an issue common to many longitudinal studies of cognitive aging and AD as advanced or unstable cardiac conditions, symptomatic stroke, and poorly controlled diabetes are often considered exclusionary for long-term, AD-focused longitudinal studies. While we partially addressed this limitation by performing follow-up sensitivity analyses in which only individuals in the highest tertile of vascular risk were included (thereby enriching for high levels of vascular risk), we acknowledge that these analyses will need to be repeated in longitudinal cohorts with AD selected to have high vascular risk, especially higher rates of type 2 diabetes. Similarly, both the ADNI and HABS cohorts are composed largely of White individuals,39 and therefore, it remains possible that associations between WMH and systemic vascular risk factors will be seen more clearly in study populations with greater representation of certain ethnic or racial groups. On a related note, further work is needed to address the possibility that certain spatial patterns of WMH (eg, juxtacortical) will demonstrate stronger correlations with vascular risk as opposed to AD-intrinsic processes. Accordingly, the results of the present study are best interpreted in the context of AD and may not generalize to populations without AD, including those with very high vascular risk.

Conclusions

The results of this cohort study suggest that the AD-related processes of brain amyloidosis and neurodegeneration are more likely to be associated with increased white matter changes that have been consistently described in ADAD and LOAD compared with vascular risk factors. After accounting for these AD-related processes, the lack of association between vascular risk and WMH further suggests that caution should be used in interpreting the presence or absence of increased WMH volume in patients with AD as evidence for or against the presence of mixed cerebrovascular pathology. Importantly, these data support the further development of white matter–centric measures to serve as biomarkers in both AD and CAA. Optimized white matter injury biomarkers may be particularly useful as measures of vessel amyloidosis in the pre-CMB and prehemorrhage phases of CAA, as tools for the study of this early phase of CAA-related pathologic change are largely lacking.

eTable 1. Participants’ Demographics and Study Information for the DIAN, ADNI, and HABS Baseline Data for the Highest FHS-CVD Tertile Group

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analyses Using Cross-Sectional (Baseline) DIAN Data

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analyses Using Longitudinal DIAN Data

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analyses Using Cross-Sectional (Baseline) ADNI Data

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analyses Using Longitudinal ADNI Data

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analyses Using Cross-Sectional (Baseline) HABS Data

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analyses Using Longitudinal HABS Data

eTable 8. Sample Characteristics for ADNI Participants Without Baseline CMB

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analysis for Hazard Ratios

eFigure. Association of Cerebral Microbleeds and Gray Matter Volume With WMH Volume in Older Adults From HABS at Baseline and Follow-up

Nonauthor Collaborators. Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Smith EE. What turns the white matter white? metabolomic clues to the origin of age-related cerebral white matter hyperintensities. Circulation. 2022;145(14):1053-1055. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.059281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McAleese KE, Miah M, Graham S, et al. Frontal white matter lesions in Alzheimer’s disease are associated with both small vessel disease and AD-associated cortical pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2021;142(6):937-950. doi: 10.1007/s00401-021-02376-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McAleese KE, Walker L, Graham S, et al. Parietal white matter lesions in Alzheimer’s disease are associated with cortical neurodegenerative pathology, but not with small vessel disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134(3):459-473. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1738-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ungvari Z, Toth P, Tarantini S, et al. Hypertension-induced cognitive impairment: from pathophysiology to public health. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2021;17(10):639-654. doi: 10.1038/s41581-021-00430-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schoemaker D, Zanon Zotin MC, Chen K, et al. White matter hyperintensities are a prominent feature of autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease that emerge prior to dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2022;14(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s13195-022-01030-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Araque Caballero MÁ, Suárez-Calvet M, Duering M, et al. White matter diffusion alterations precede symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2018;141(10):3065-3080. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S, Viqar F, Zimmerman ME, et al. ; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network . White matter hyperintensities are a core feature of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence from the dominantly inherited Alzheimer network. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(6):929-939. doi: 10.1002/ana.24647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAleese KE, Firbank M, Dey M, et al. Cortical tau load is associated with white matter hyperintensities. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2015;3:60. doi: 10.1186/s40478-015-0240-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshita M, Fletcher E, Harvey D, et al. Extent and distribution of white matter hyperintensities in normal aging, MCI, and AD. Neurology. 2006;67(12):2192-2198. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000249119.95747.1f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma R, Sekhon S, Cascella M. White matter lesions. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wardlaw JM, Valdés Hernández MC, Muñoz-Maniega S. What are white matter hyperintensities made of? relevance to vascular cognitive impairment. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(6):001140. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Orantes M, Wiestler OD. Vascular pathology in Alzheimer disease: correlation of cerebral amyloid angiopathy and arteriosclerosis/lipohyalinosis with cognitive decline. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62(12):1287-1301. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.12.1287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pålhaugen L, Sudre CH, Tecelao S, et al. Brain amyloid and vascular risk are related to distinct white matter hyperintensity patterns. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2021;41(5):1162-1174. doi: 10.1177/0271678X20957604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caetano A, Ladeira F, Barbosa R, Calado S, Viana-Baptista M. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy—the modified Boston criteria in clinical practice. J Neurol Sci. 2018;384:55-57. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shirzadi Z, Yau WW, Schultz SA, et al. ; DIAN Investigators . progressive white matter injury in preclinical Dutch cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Ann Neurol. 2022;92(3):358-363. doi: 10.1002/ana.26429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leys D, Pruvo JP, Parent M, et al. Could Wallerian degeneration contribute to “leuko-araiosis” in subjects free of any vascular disorder? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54(1):46-50. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.54.1.46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris JC, Aisen PS, Bateman RJ, et al. Developing an international network for Alzheimer research: the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network. Clin Investig (Lond). 2012;2(10):975-984. doi: 10.4155/cli.12.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mojiri Forooshani P, Biparva M, Ntiri EE, et al. Deep Bayesian networks for uncertainty estimation and adversarial resistance of white matter hyperintensity segmentation. Hum Brain Mapp. 2022;43(7):2089-2108. doi: 10.1002/hbm.25784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.AICONSLab . Welcome to HyperMapp3r’s documentation! 2020. Accessed September 2, 2023. https://hypermapp3r.readthedocs.io/en/latest/

- 20.Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5(2):143-156. doi: 10.1016/S1361-8415(01)00036-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reuter M, Schmansky NJ, Rosas HD, Fischl B. Within-subject template estimation for unbiased longitudinal image analysis. Neuroimage. 2012;61(4):1402-1418. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kantarci K, Gunter JL, Tosakulwong N, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Focal hemosiderin deposits and β-amyloid load in the ADNI cohort. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(5)(suppl):S116-S123. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fotiadis P, van Rooden S, van der Grond J, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Cortical atrophy in patients with cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a case-control study. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(8):811-819. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30030-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su Y, Blazey TM, Owen CJ, et al. ; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network . Quantitative amyloid imaging in autosomal dominant alzheimer’s disease: results from the DIAN study group. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0152082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jagust WJ, Landau SM, Koeppe RA, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 2 PET Core: 2015. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(7):757-771. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabin JS, Schultz AP, Hedden T, et al. Interactive associations of vascular risk and β-amyloid burden with cognitive decline in clinically normal elderly individuals: findings from the Harvard Aging Brain Study. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(9):1124-1131. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . 2017. Accessed December 6, 2022. https://adni.loni.usc.edu/

- 28.Yau WW, Shirzadi Z, Yang HS, et al. Tau mediates synergistic influence of vascular risk and Aβ on cognitive decline. Ann Neurol. 2022;92(5):745-755. doi: 10.1002/ana.26460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chhatwal JP, Schultz SA, McDade E, et al. ; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network Investigators . Variant-dependent heterogeneity in amyloid β burden in autosomal dominant Alzheimer’s disease: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses of an observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(2):140-152. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00375-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Agostino RB Sr, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, et al. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117(6):743-753. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.699579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cairns NJ, Perrin RJ, Franklin EE, et al. ; Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network . Neuropathologic assessment of participants in two multi-center longitudinal observational studies: the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) and the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network (DIAN). Neuropathology. 2015;35(4):390-400. doi: 10.1111/neup.12205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sliz E, Shin J, Ahmad S, et al. ; NeuroCHARGE Working Group . Circulating metabolome and white matter hyperintensities in women and men. Circulation. 2022;145(14):1040-1052. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wardlaw JM, Allerhand M, Doubal FN, et al. Vascular risk factors, large-artery atheroma, and brain white matter hyperintensities. Neurology. 2014;82(15):1331-1338. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Graff-Radford J, Arenaza-Urquijo EM, Knopman DS, et al. White matter hyperintensities: relationship to amyloid and tau burden. Brain. 2019;142(8):2483-2491. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scott MR, Hampton OL, Buckley RF, et al. Inferior temporal tau is associated with accelerated prospective cortical thinning in clinically normal older adults. Neuroimage. 2020;220:116991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sepulcre J, Schultz AP, Sabuncu M, et al. In vivo tau, amyloid, and gray matter profiles in the aging brain. J Neurosci. 2016;36(28):7364-7374. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0639-16.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joseph-Mathurin N, Wang G, Kantarci K, et al. ; Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network . Longitudinal accumulation of cerebral microhemorrhages in dominantly inherited Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2021;96(12):e1632-e1645. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000011542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marma AK, Lloyd-Jones DM. Systematic examination of the updated Framingham Heart Study general cardiovascular risk profile. Circulation. 2009;120(5):384-390. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.835470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ashford MT, Raman R, Miller G, et al. ; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Screening and enrollment of underrepresented ethnocultural and educational populations in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Alzheimers Dement. 2022;18(12):2603-2613. doi: 10.1002/alz.12640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Participants’ Demographics and Study Information for the DIAN, ADNI, and HABS Baseline Data for the Highest FHS-CVD Tertile Group

eTable 2. Sensitivity Analyses Using Cross-Sectional (Baseline) DIAN Data

eTable 3. Sensitivity Analyses Using Longitudinal DIAN Data

eTable 4. Sensitivity Analyses Using Cross-Sectional (Baseline) ADNI Data

eTable 5. Sensitivity Analyses Using Longitudinal ADNI Data

eTable 6. Sensitivity Analyses Using Cross-Sectional (Baseline) HABS Data

eTable 7. Sensitivity Analyses Using Longitudinal HABS Data

eTable 8. Sample Characteristics for ADNI Participants Without Baseline CMB

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analysis for Hazard Ratios

eFigure. Association of Cerebral Microbleeds and Gray Matter Volume With WMH Volume in Older Adults From HABS at Baseline and Follow-up

Nonauthor Collaborators. Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative

Data Sharing Statement