Abstract

In this article, we explore the experiences of people who carry monetary sanction (or penal) debt across eight U.S. states. Using 519 interviews with people sentenced to fines and fees, we analyze the mental and emotional aspects of their experiences. Situating our analysis within research on the social determinants of health and the stress universe, we suggest that monetary sanctions create an overwhelmingly palpable sense of fear, frustration, anxiety, and despair. We theorize the ways in which monetary sanctions function as both acute and chronic health stressors for people who are unable to pay off their debts, highlight the mechanisms linking penal debt with mental and emotional burdens, and generalize our findings using national data from the U.S. Federal Reserve. We find that the system of monetary sanctions generates a great deal of stress and strain that becomes an internalized punishment affecting many realms of people’s lives.

Keywords: health, stress, criminal legal system, monetary sanctions, fines and fees

Monetary sanctions lead to long-term criminal legal entanglement, supervision, and punishment for people who are unable to afford them. These fiscal penalties, also called legal financial obligations (LFOs), include court sanctioned fines, fees, restitution, and surcharges as well as various cost points and hidden costs related to the completion of mandated sentences (Harris 2016; Harris, Smith, and Obara 2019; O’Neil and Strellman 2020). Monetary sanctions can affect people’s behavioral transitions to adulthood, influence their self-identities, and limit their abilities to move into successful life paths (Harris 2016). Current research outlines the “piling on” (Uggen and Stewart 2015) of monetary sanctions as it puts strain on family networks and takes away resources for housing and employment stability (Pattillo et al. 2022, this volume). The inability to pay monetary sanctions creates a palpable sense of fear, frustration, anger, and resignation (Harris 2016; Cadigan and Kirk 2020; Pattillo and Kirk 2020). In other words, monetary sanctions lead to a great deal of stress and strain for those who are unable to pay.

This article examines the role that monetary sanctions have in creating stress, mental strain, and emotional exhaustion for people who have experienced criminal legal contact. We frame our analysis using the stress process paradigm (Pearlin 1989; Wheaton 1994), which emphasizes how “social factors bear on the kinds of stressors to which people are exposed, the personal and social resources to which people have access, and the emotional, behavioral, and physical disorders through which stress is manifested” (Pearlin 1989, 254). We specifically ask how monetary sanctions create both acute and chronic stressors in people’s lives. We frame the sentencing of monetary sanctions as the primary stressor, and related criminal legal contact—due to nonpayment and remaining penal debt—as secondary stressors. Acute stress refers to the specific, stress-inducing moments that generally result from this criminal legal contact. For our participants, these moments included the sentencing of monetary sanctions themselves, summons to court to explain their financial circumstances, warrants issued for their arrest, the loss of driver’s licenses, and even incarceration. In addition to these specific moments of stress, participants also described an ongoing experience of anxiety due to their inability to fully pay court-ordered fiscal penalties. Individuals felt this chronic stress daily as they balanced paying their LFOs with the costs of their basic needs and the basic needs of their families. They also worried about the constant possibility of criminal legal intervention and how that intervention could further disrupt their lives. As Michele Cadigan and Gabriela Kirk (2020) illustrate, individuals with court debt face and endure a recurring cycle of procedural pressure points that leave many on “thin ice.” This study further demonstrates how court debt remains persistent for long periods and includes ongoing negative experiences related to people’s reduced economic means and fiscal liability.1

We also show how the stress and strain of monetary sanctions could lead to negative health outcomes. Many respondents suggested that their stress led to mental health concerns, particularly severe anxiety and depressive symptoms. In addition, several of our respondents indicated how monetary sanctions might decrease physical health by influencing their daily choices of travel, food consumption, and health decisions. We bolster these findings using a nationally representative sample, showing that individuals who have household legal debt are more likely to have lower overall health than individuals who do not. Although the scope of our original study does not allow us to draw a definitive conclusion about health impacts, these preliminary results suggest such a relationship. Further, although we do not attempt to argue causality, we do draw out the possible associations between penal debt, extreme stress, and health outcomes.

Our findings reveal that court-imposed monetary sanctions—to those who have no ability to pay and even those struggling to make monthly payments—function as an underexamined mechanism that further associates criminal legal engagement with negative outcomes such as stress and anxiety. We argue that the stress and cumulative disadvantages generated by the system of monetary sanctions could exacerbate existing anxieties or create new disorders that further exacerbate economic and racial health inequities. We follow the arguments of scholars who suggest that the criminal legal system serves as a key social determinant of health, especially for people of color and those from poor communities. By understanding monetary sanctions as a form of legally and socially produced stress, we outline the context for future research to explore the association between criminal legal debt and poorer health outcomes for individuals, families, and their communities.

THE STRESS PROCESS MODEL

Research, public discourse, and policy discussions increasingly cite a set of social determinants that affect individual, family, community, and population health (Warren and Hernandez 2007; Williams et al. 1997; CSDH 2008). Scholars of health outcomes encourage examinations of how economic and social resources are organized and distributed within social contexts versus only behavioral and medical factors (Amick et al. 1995; Tarlov 1996; Raphael 2006). This framework recognizes that people are situated within not only individual biology and lifestyle choices but also social contexts that shape health outcomes.

An important question is then raised about why certain institutional and societal pressures produce such dramatic negative health outcomes. A central association arises in the experience of stress. Stress can be produced by life pressures, including those relating to workplace burdens, poor health, financial vulnerability, and relationship tensions (Hammen et al. 2009). In response to these perceived stressors, our bodies attempt to adapt with various chemical and psychological reactions (McEwen 2012). “The way a person can anticipate a certain stressor and then control it, largely defines the resulting stress response” (Mariotti 2015, 1). Long-term emotional pressure can thus lead to ongoing or chronic “cognitive, emotional, and behavioral dysfunctions” (Mariotti 2015, 2). Studies find that chronic stress can lead to immune dysfunction, depression, serious disease, and hypertension, and can even promote cancer development (Lucassen et al. 2014; Glaser and Kiecolt-Glaser 2005; Dantzer et al. 2008; Rosenthal and Alter 2012; Lundgren et al. 2011; Heidt et al. 2014). In contrast to chronic stress, acute stress is pressure experienced by a terrifying or traumatic event such as the death of a family member, car accident, or assault. Such events can lead to similar biological and behavioral responses as those of chronic stress (Shors, Gallegos, and Breindl 1997; Barton, Blanchard, and Hickling 1996). In short, the stress that people cannot manage or control, either acute or chronic, leads to poor health outcomes.

This interaction between social circumstances, stress, and health disparities has led scholars to suggest a more robust “sociological study of stress” (Pearlin 1989). Leonard Pearlin’s stress process model emphasizes the importance of social structures in determining how stress may be produced and how it will affect an individual’s well-being. He describes two distinct types of stress that may result from social circumstances. First are primary stressors, which are specific life events, circumstances, or trauma that are generally unwanted and disruptive. These moments may be thought of as “the first to occur in people’s experiences” and the origin of many types of socially produced stress (1989, 248). A host of secondary stressors may flow from these primary stressors. Secondary stressors are events or circumstances that occur as a direct result of the primary stressor but are also independently stress producing. The key point Pearlin emphasizes is that a single primary stress event often does not occur in isolation, but instead “one event leads to another event or triggers chronic strains; strains, for their part, beget other strains or events” (247). From this perspective, we can see how primary and secondary stressors can produce both acute and chronic stress. Both primary and secondary stressors may result in specific, highly stressful events (acute stress) and may result in more prolonged feelings of anxiety that occur in relation to those events (chronic stress).

Scholars refer to this complex interaction between stress, health, and context as the “stress process paradigm” to emphasize that stress is not simply an internally produced state, but that it is caused and reproduced by an interaction with the institutional environment (Pearlin et al. 2005).2 Studies that examine the stress process should focus on the social and economic circumstances in which people are embedded and how these dimensions of social organization lead to varying exposure to stress, the ways in which it manifests, and the resources people have to manage it. Thus, to understand the social determinants of health we must understanding the social determinants of stress itself.

CRIMINAL LEGAL CONTACT AND HEALTH OUTCOMES

How might the criminal legal system influence the stress process paradigm for people under its control? Sadly, one of the most salient institutions in the lives of disadvantaged individuals is that of the criminal legal system. Over the last forty-five years, the United States incarceration rate has increased by 500 percent to over 6.6 million people in 2016, leaving the United States with the highest incarceration rate in the world (Kaeble and Cowhig 2018; The Sentencing Project 2019). Comparatively, the United States has created a truly exceptional criminal legal system in terms of raw numbers and in the disparate rates by which people of color are surveilled, arrested, convicted, and incarcerated. In 2017 for example, Black people made up 13.4 percent of the U.S. population but 33.1 percent of the people housed in state and federal prisons. Latinx people made up 18.5 percent of the U.S. population but 23.4 percent of the incarcerated population. Black women have an imprisonment rate of ninety-two, Latina women of sixty-seven, and White women of forty-nine per hundred thousand people. The rate of imprisonment for Black men is 2,330, Latino men 1,054, and White men 397 per hundred thousand (Bronson and Carson 2019). Not only are large numbers of people in the United States ensnared in the criminal legal system, but this entanglement and control is also performed disproportionately on racially and ethnically marginalized people.

These overwhelming statistics sketch the broad collection of people, their families, and communities who have had criminal legal entanglement. A developing subfield within the study of the criminal legal system is the disparate health outcomes observed for people arrested, convicted, and incarcerated (Binswanger et al. 2011). Consistent with the findings that social status affects health outcomes, contact with the criminal legal system often decreases the well-being of individuals, their families, and their communities (for a review, see Massoglia and Pridemore 2015). To varying degrees, criminal legal events such as police surveillance, arrest, conviction, and incarceration affect people’s psychological well-being, rates of hypertension, and exposure to infectious diseases (Schnittker et al. 2015; Hirschfield et al. 2006; Massoglia 2008a). This research clearly demonstrates that entanglement with the criminal legal system at all levels has a negative effect on health.

An important mechanism likely linking criminal legal contact and health outcomes is the production of stress. In an examination of neighborhood-level frisk and use of force proportions, Alyasah Sewell, Kevin Jefferson, and Hedwig Lee find higher levels of psychological distress among men living in neighborhoods with intense police surveillance (2016, 9). Other studies find associations between current and recent incarceration and depression for those confined; although the role of stress was not often clear (Sykes 2007; Goffman 1961; Massoglia 2008a; Schnittker et al. 2015; Steadman et al. 2009). In an analysis of recently incarcerated fathers, Kristin Turney, Christopher Wildeman, and Jason Schnittker (2012) attempt to disentangle the effects of current and recent incarceration on mental well-being and find that both currently and recently incarcerated fathers have higher rates of depression than their counterparts. Using Pearlin’s stress process framework, they suggest that incarceration creates a “fundamental shift in the life course” generating economic insecurity and disrupted romantic, family, and friendship networks (477). These strained life dimensions collectively function as secondary stressors resulting from incarceration, which their analysis suggests could be a cause of the higher rates of depression.

Although these studies have begun to sketch the connection between the stress of criminal legal contact and health outcomes, significant gaps remain. Specifically, little research has explored the production and impact of stress through sanctions outside of arrests and incarceration. In this article, we turn attention to the latent anxiety created by the ongoing punishment of monetary sanctions. This stress is independent of the usual focus of contacts with the criminal legal system. Although we can envision how visible points of contact (such as arrest and incarceration) can lead to stress, it is more difficult to see the anxiety and emotional trauma generated from the enduring and invisible force of the system of monetary sanctions. Just as they experience a chronic illness, people who owe monetary sanctions experience chronic stress and acute moments of anxiety as they move through their lives and are constantly confronted by the criminal legal system and its representatives. Our research suggests that it is important to understand how individuals manage the anxiety of meeting their legal obligations while also trying to navigate both the legal system and their daily lives.

MONETARY SANCTIONS AS STRESS PRODUCER

We suggest that the system of monetary sanctions is an important mechanism connecting criminal legal contact with stress, strain, and anxiety for individuals and their families. Court-imposed monetary sanctions, also called legal financial obligations, are fines, fees, surcharges, costs, and restitution that people entangled with legal systems must pay to become completely free (Pattillo and Kirk 2021). Every state in the United States sentences some form of these monetary sanctions on traffic citation, misdemeanor, juvenile, and felony convictions (Harris 2016; Kohler-Hausmann 2018; Natapoff 2018; Paik 2020). People remain under court supervision until their debt is paid. They are also subject to court summons to explain their fiscal circumstances, warrants if they do not show up to court, loss of driver’s licenses for nonpayment, and even incarceration. Furthermore, in many states, as highlighted recently with Florida’s Amendment 4, until one pays their fines and fees in full, they are unable to vote, serve on juries, or run for elected office (see Morse 2021).

No national statistics cite the total number of people who have unpaid monetary sanctions. One recent report, however, did find that of twenty-five states, at least $27.6 billion in fines and fees is owed to state and local jurisdictions (Hammons 2021). Taking this known amount, along with the numbers of people currently under some form of criminal legal control (6.6 million), and those estimated to have a felony conviction (3 percent), we can safely assume that a large segment of the U.S. population has been charged with monetary sanctions at some point in their lifetime (Kaeble and Cowhig 2018; Shannon et al. 2017). Further, this debt burden is borne disproportionately by African American men, 33 percent of whom are estimated to have a felony conviction (Shannon et al. 2017). Monetary sanction debt is a significant component to criminal legal entanglement, disparately so, and an obvious dimension that could influence the well-being of individuals and their families.

The burgeoning subfield studying monetary sanctions highlights the negative effects of these sanctions and links them to economic instability, neighborhood debt burden, difficulty with community reentry, and social disintegration (Cadigan and Kirk 2020; Harris 2016; Pattillo and Kirk 2020; Friedman and Pattillo 2019; O’Neill et al. forthcoming; Shannon et al. 2020; Cadigan and Smith 2021; Sebastian, Lang, and Short 2020; Link et al. 2021). Although this research has yet to examine the relationship between long-term court-imposed monetary sanctions and health outcomes, research suggests that extreme pressure is put on debtors by courts and other legal agents to make regular payments even in instances of poverty (Harris 2016). Using interview and court observational data, Cadigan and Kirk (2020) illustrate the powerful pressure and anxiety people feel because of their inability to make full or regular payments toward their monetary sanctions. Similarly, Mary Pattillo and Kirk (2020) describe how interview respondents process the court-imposed debt as an injustice that serves as a “double punishment” that feels like “extortion” (64, 66). The cumulative body of research on monetary sanctions clearly illustrates a punishment schema that puts undo pressure and strain on individuals who are “too poor to pay” (62) and leads to feelings of perpetual stress and frustration.

THIS STUDY

This analysis examines how monetary sanctions extend the experience of conviction and incarceration into the community and exacerbate economic and psychological stressors for people unable to pay their court debts. Adapting Pearlin’s stress universe framework to assess interview data with people who owe monetary sanctions, we examine how the sentencing of monetary sanctions served as a primary stressor associated with acute moments of fear, anxiety, and stress, as well as long-term chronic emotional distress. Further, we illustrate how nonpayment or irregular payments lead to secondary stressors as further legal entanglements and punishments ensue. As a result, additional stress fomented and accumulated. The related chronic and acute stress, as interviewees explained, become a form of internalized social control that dictated their behaviors and constricted their abilities to engage in their lives. The interview data illustrate how people embody this stress, creating an indeterminate punishment served outside of the courtrooms and jail cells of the criminal legal system. In sum, our analysis indicates ways in which these monetary sanctions are associated with conditions of severe stress and emotional strain. We also situate our findings using a national survey of household economics to show that this association between legal debt and negative household outcomes is likely generalizable.

DATA AND METHODS

Our analysis is set within the context of a broader national study of monetary sanctions. The aim of the Multi-State Study of Monetary Sanctions was to examine the systems, practices, and related consequences of court sentenced fines, fees, and related court costs in eight states.3 For this analysis, we wanted to explore the topic of stress and strain as it relates to the punishment of monetary sanctions. We were interested in how interviewees talked about their anxiety and how monetary sanctions might generate stress or other related health problems. At the outset of our analysis, we expected to find discussions about physical health problems, but were surprised and overwhelmed that the interviewees spent a great amount of time describing their stress and anxiety.

Our analysis here relies on interviews with people sentenced to monetary sanctions in all eight states. To begin, we pulled all the excerpts regarding health from the Washington State interviews and coded inductively using NVivo software. For our larger project, we did not ask a direct question in our open-ended interview protocol about health; however, respondents regularly discussed issues related to their mental and emotional well-being during the interviews. As outlined in the introduction to this volume (Harris, Pattillo, and Sykes 2022), the full research team developed a codebook for reviewing all interview transcripts. Regarding health, these codes included a section on emotions, health, and substance use. For this analysis, we used these codes to pull excerpts from the interview transcripts and then recoded the data for further detail. We identified the following sets of codes as important: financial drain, multiple ways they create stress, hard to pay all monthly bills and pay LFOs, related disability and illnesses, impact on personal relationships, criminal conviction and monetary sanction, consequences for employment. We then began writing memos using these codes to explore how respondents described their stress and where, why, and when monetary sanctions increased (or decreased) their anxiety. We then read the interview transcripts for the same questions across the other seven states while looking for both similar and outlying sentiments to build on the outline we had developed.

The resulting analysis walks through these dimensions, first examining the sentencing of monetary sanctions as a primary stressor and then outlining the resulting secondary stressors related to nonpayment or ongoing penal debt. We use the concepts of chronic and acute stress to illustrate the relationship between wellness and monetary sanctions and show how the feelings of anxiety ebb and flow depending on moments of contact with the criminal legal system.

To preface these findings from our interview data, we use national survey data provided by the Federal Reserve Bank for 2019 (Federal Reserve 2020). These nationally representative data provide a broader view for illustrating the relationship between legal debt and health outcomes. The Survey of Household Economic and Decisionmaking (SHED) is an annual national survey that measures the economic well-being and risk factors of households in the United States. It is one of the only national surveys to include a question asking about court debt: “do you, or someone in your immediate family, currently have unpaid legal expenses, fines, fees, or court costs?” We use this question to compare differences in general health and health-related issues between people with legal debt and those without such debt. This question is not ideal in that it potentially represents household legal debt instead of personal debt, but we believe that it is a useful tool for exploring the relationship between personal or household debt and health-related outcomes. Table 1 lists the questions we selected from the SHED data that related to health outcomes and the descriptive composition of the sample.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Selected Questions

| Question | n | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you or someone in your immediate family currently have any unpaid legal expenses, fines, fees, or court costs? (Y/N) | 12,135 | 0.06 | 0.23 |

| In general, would you say your physical health is… ? (1 = Excellent; 5 = Poor) | 10,794 | 3.43 | 0.94 |

| Did health limitations or disability contribute to you not working/not working as much as you wanted? (Y/N) | 7,118 | 0.25 | 0.43 |

| Was illness or health a reason you did not attend college? (Y/N) | 503 | 0.12 | 0.33 |

| In the past twelve months, was there a time you needed mental health services but went without because you couldn’t afford it? (Y/N) | 12,085 | 0.07 | 0.25 |

| In the past twelve months, was there a time you needed dental health services but went without because you couldn’t afford it? (Y/N) | 12,110 | 0.18 | 0.38 |

| In the past twelve months, was there a time you needed follow-up care but went without because you couldn’t afford it? (Y/N) | 12,101 | 0.08 | 0.27 |

| In the past twelve months, have you had any unexpected major medical expenses that you had to pay for out of pocket? | 12,114 | 0.24 | 0.43 |

Source: Authors’ tabulation based on SHED data (Federal Reserve 2020).

The purpose of supplementing our qualitative work with a national sample is important. We do not intend to directly compare our interview data analysis with the SHED data. Instead, we offer a broad and simple statistical analysis that shows a significant relationship between health and legal debt. These findings provide increased justification for the in-depth exploration of this relationship in our interview data and suggests that these findings may be generalizable to a sample beyond the states in our study. It is also likely that the national data are understated, in that most likely our population of interest (people with legal debt and criminal legal entanglements) are underreported in the SHED data (see Pettit 2012).4 Our aim is to highlight the overall association between monetary sanctions and anxiety and stress outcomes, without ascribing any directionality.

FINDINGS

The system of monetary sanctions generates a great deal of stress and strain that becomes an internalized punishment affecting many realms of people’s lives.

CONNECTING LEGAL DEBT WITH HEALTH OUTCOMES

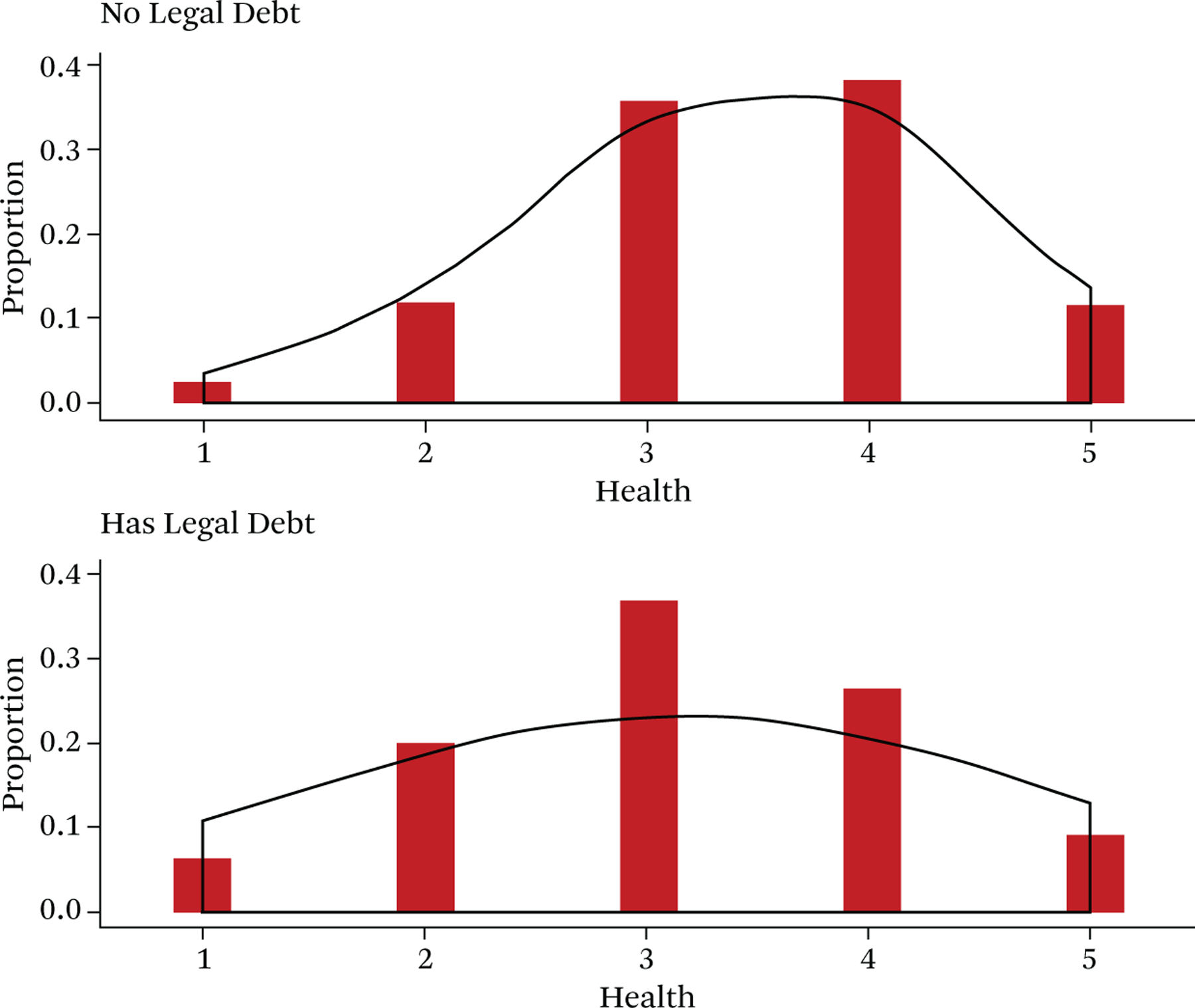

In the Federal Reserve’s national dataset, individuals were asked to rate their general health (a score of 1 being poor and 5 being excellent). Figure 1 shows the distribution of answers of individuals who had legal debt against those who did not. Individuals who have legal debt are more likely to indicate that their health falls into the lower range. A one-sided t-test confirms a significant difference between the average rating of individuals with legal debt and those without ( = 3.12 and 3.44, respectively; t = 7.19, p < .001).

Figure 1.

Ratings of General Health for Individuals in Households

Source: Authors’ tabulation.

We also explored associations between legal debt, structural impacts, and health-care consequences of having legal debt using Pearson’s chi-square tests. These tests revealed a significant association between carrying legal debt and working less due to health concerns (χ2 = 56.28, p < .001), although we did not find an association between legal debt and not attending college due to health concerns (χ2 = .06, p = .80). Further, we found that individuals with debt were more likely to indicate that they did not receive mental health care (χ2 = 149.3, p < .001), dental health care (χ2 = 349.22, p < .001), or follow-up care (χ2 = 243.93, p < .001) because of cost. Finally, individuals who had legal debt more often indicated that they had also accrued some form of medical debt within the past twelve months (χ2 = 18.16, p < .001). The proportions associated with these findings are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Average Percentage of Individuals Indicating Health-Related Outcomes

| Question | No Legal Debt | Has Legal Debt |

|---|---|---|

| Did health limitations or disability contribute to you not working or not working as much as you wanted? | 23.7 | 38.9 |

| Was illness or health a reason you did not attend college? | 11.9 | 14.0 |

| In the past twelve months, was there a time you needed mental health services but went without because you couldn’t afford it? | 6.0 | 18.1 |

| In the past twelve months, was there a time you needed dental health services but went without because you couldn’t afford it? | 16.3 | 44.5 |

| In the past twelve months, was there a time you needed follow-up care but went without because you couldn’t afford it? | 6.1 | 23.5 |

| In the past twelve months, have you had any unexpected major medical expenses that you had to pay for out of pocket? | 23.3 | 30.4 |

Source: Authors’ tabulation based on SHED data (Federal Reserve 2020).

In sum, the survey data illustrate significant differences between people who live with household court related debt and those who do not. Individuals in households with legal debt were less healthy, worked less because of health concerns, and were less likely to receive health-care services because of cost. We present this nationally sampled data in our findings as a preliminary indication that LFOs may have serious impacts on long-term health. This suggests that court debt can lead to differential health outcomes and serves as a springboard for exploring stress as a possible linking mechanism.

HOW PEOPLE DESCRIBED THEIR STRESS

We use the stress universe framework to analyze our participants’ experiences with LFOs in the greater context of economic precarity, limited financial resources, and constant pressure from the criminal legal system. We suggest that the sentencing of monetary sanctions is a primary stressor for people sentenced within the criminal legal system. We find a secondary set of stressors that revolved around being summoned to court, having their driver’s license suspended, and experiencing police encounters that could end in incarceration. Within this framework, we outline the ways in which interviewees described the constant feelings of stress and anxiety associated with their monthly budgets and living expenses, in addition to their court-ordered payments. Much of this stress is chronic and ongoing, but acute stress would arise from intense interactions either in courtrooms or during potential encounters with police during traffic stops. A summary of these stress processes as they relate to LFOs is outlined in table 3.

Table 3.

Sources of Stress from Monetary Sanctions

| Acute Stress | Chronic Stress | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary stressor | sentencing of LFOS | anxiety over ability to pay balancing payments and basic needs |

| Secondary stressors | court summons loss of driver’s license arrest on warrants incarceration | fear of criminal legal intervention lack of transportation |

Source: Authors’ tabulation.

PRIMARY STRESSOR: PUNISHMENT OF MONETARY SANCTIONS

For many people, the sentence of fines and fees functions as a primary stressor that triggers chronic stress related to attempting to balance budgets and manage day-to-day living. Many of our respondents described constantly thinking about their monetary sanctions as they went about their daily lives. A key concern was whether they would be able to balance the cost of basic needs with their monthly payments. Several respondents talked about making daily calculations about their spending to make sure that they would have enough money left over to pay their LFOs. Jacob, a Native American man from a rural county in Washington State, described his thinking process when calculating his daily expenses.

There’s times that I went without eating and without buying…. Up to this day I’ve never bought anything for myself…. I always sold my socks. My underwear I sold. I would buy those, but I’d wear them till they were falling apart, and I’d still sell them…. Even getting in my car and how much gas am I gonna waste to go to this place, and should I walk to here and park here. I’d have to analyze every move, everything I did to cent amounts. From waking up till going to bed. Should I eat this? No, ‘cause then I’m gonna have to buy this tomorrow. Or should I just eat half? When I was paying fines like that it was worse. It was like that’s the first thing that you paid off, and then the next thing was like how am I gonna do it for next month? And it was constantly like that for a lot of years, man. Like I tell you, up to this day I still budget myself. I still stress … that extra bill killed us man. Killed me.

Jacob described how the chronic strain of debt to the courts shaped every economic decision he made—he regularly policed his spending to stay compliant with his court-ordered debt, but also to stretch what money he had to live. He explained that he was already living in precarious economic situations and that the added court bill owed to the state strained his finances even further. His description of how he adapted his life to living in debt is interesting. “Up to this day,” he said, illustrating how the punishment of monetary sanctions constrained even his current behaviors and orientation toward money in that he had internalized this economic pressure and continued to live with the sense of punishment even after he completed his payments.

One of the main concerns that respondents expressed in interviews was just this—how their required monthly payments interrupted their ability to meet other financial needs. Respondents frequently related how stressful this fiscal balancing act made them feel. As Mark, an African American man from Washington State, remarked, “[LFO payments] take money out of my pocket to pay, that I could be paying for rent, that I could be paying for food, and supplies, and health … then it’s still costing me. It’s still affecting my debt. It’s still a debt. It’s still a burden.”

Here Mark made an important point, that even when making regular payments, people sentenced to court costs are burdened and constrained in their living circumstances. It is not just that being unable to pay that is a hardship, but also that paying down these debts is difficult even for those with a bit of extra money to make regular monthly payments. Like Mark, respondents were concerned that the court-mandated monetary sanctions could cause them to lose their housing or be unable to afford food and basic supplies.5 Even people who said they had stable employment related how required payments influenced their ability to provide for both themselves and their family members. Individuals talked about how it was already difficult to get steady employment because they had a criminal record and that LFOs further burdened their earning capabilities. As indicated by the project’s survey statistics (Harris, Pattillo, and Sykes 2022, this volume), many people were also unemployed or had serious illnesses that prevented them from working. However, these individuals were still sentenced to monetary sanctions. Within these precarious contexts, many people expressed a sense of hopelessness about being able to pay. Rachel, a white woman from California, explained her anxiety: “Stress is the biggest factor. It’s always constantly on the back of your mind that you’re not free. You have to keep paying. Every cent you earn, it’s owed to the state, to a judge, to the county, to somewhere that you’re never going to get.”

Several respondents said that they made daily calculations about their spending to make sure that they had enough left over to be able to pay their LFOs. They needed to be able to both afford their basic needs and pay their debts to retain their freedom from the courts and incarceration. This constant calculation could be incredibly stressful. Kyle from Seattle described the types of calculations he would make every week: “So this week I didn’t get as many hours of overtime as I wanted, so that means there’s going to be this much out of my check, that means, so the motorcycle payments, I still have to do that, and I still have to put this much in savings. Well, that leaves me with a smaller amount to work with. Well, I still have to give these people money for my LFO’s otherwise they’re going to put a warrant out.”

Frequently the interviewees described every economic transaction as tinged with anxiety and concern over balancing necessities with financial legal obligations. “It was daily stress,” Richard from Georgia said, “making sure I had the money at the end of every month to pay.” Sarah from Missouri expressed the same sentiment when asked if she worried about money, stating that she worried “all day, every day where the next dollar was going to come from.”

In response to these pressures, people described important life necessities as being traded off to pay the court the minimum amount due. Brady, a biracial man from New York, compared this daily balance to playing a game of Jenga: “Start piling on, on the top of each other. Whatever one you decide to handle first, it might seem to the most to be important to you, but the other thing turns out to be the most important. Then the whole tower come falling down. And then you have to catch everything else at once.”

Having to pay LFOs took money directly out of their hands that would otherwise go to meeting their basic needs. This constant money management down to the last cent generated a palpable sense of urgency, strain, and anxiety. The sentence of monetary sanctions then can be seen as a primary stressor that induced a great deal of chronic stress and anxiety for people.

SUPPORTING FAMILY AND CHILDREN

Meeting family responsibilities became an additional source of chronic stress for many who owed monetary sanctions. Some respondents expressed anxiety over being able to provide for their significant others and children, or to meet the responsibilities that they had to other family members while also paying their LFOs. Many interviewees who were parents expressed their guilt in telling their children that they could not take them out to eat or to activities that might cost money. Annalise from Texas talked about how difficult it was to explain to her children why she could not buy them the items they needed:

It’s just like I said, [LFOs] made it hard or impossible to be able to do certain things that my kids really needed if it was clothes or something they really, really needed. Like, “Okay well, they gonna have to wait because I have to pay this so I don’t get in trouble so I can get this cleared and then maybe we can try to get it later on.” Even though they really, really, really needed it. And, of course they don’t understand because it’s like, “Hey, I need this,” and I’m like, “Hey, mom doesn’t want to get in trouble. We have to take care of this first, it’s priority.”

Annalise described her penal debt as a constant reminder of the court’s control and power over her life: if she did not make her monthly payments she would “get in trouble.” She tried to avoid this consequence at all cost, even if it meant her children had to go without.

Interviewees gave example after example of the tension and disappointment they and their family members felt because of their legal debt. Jacob from Washington spoke of taking care of his nieces and nephews: “[The LFO] took money away from them that I could [have used] taking care of them. Diapers, food, clothes.” Another man from Washington State, Jerry, described the stress from “so many responsibilities” on his shoulders for not just himself, but also for his family members. These constant considerations over spending money were a clear source of anxiety and emotional stress that was ever-present in the lives of these individuals.

Owing monetary sanctions can lead to family members’ stress as well. Many interviewees described how penal debt brought a shadow to people’s immediate and extended family networks. During the court observations conducted for the larger project, court officials would tell people to ask their partners, parents, and even friends for money to pay toward their legal debt. As Daniel Boches and his colleagues (2022, this volume) illustrate in detail, penal debt became a burden and stressor for all household members and beyond. At times, people described having to ask family for money to directly pay their LFO bills; at other times, they described instances of being unable to pay their share of other household bills. These findings are echoed by other studies in this volume. Beth Huebner and Sarah Shannon (2022, this volume) illustrate how some probation officers required the inclusion of all household members’ income in paperwork calculating minimum payments and ability to pay. Mary Pattillo and her colleagues (2022, this volume) also illustrate the recursive relationship between housing insecurity and penal debt and show how the debt undermines the stability of the entire family. Monetary sanctions thus cause stress and anxiety not only for people charged, but also for the people they love.

SECURING STRUCTURAL STABILITY

Respondents were also concerned about how paying their LFOs influenced their opportunities for structural stability. One concern was that paying their LFOs would not leave them enough for rent and they could lose their housing because of it. Jerry told us that he usually had enough to pay his rent, but that at times recently he had come up “short and behind” with his income and that often did not have money left over to pay his court costs. Mitchell from Washington State, who had been living with his parents to save money, talked about how paying LFOs drained his ability to buy a home or a car. “I’m still struggling,” he said, “because that money that I’m putting towards my fines could go to a house, you know, an apartment, a car. It’s not easy, it’s not easy. I’ll tell you that right now.” Others told us that they prioritized paying for their housing as a basic need, even if it meant that they had to delay their LFO payments. As Geoff, a Native American welder from Washington State, described it, “it’s another bill I have to pay. Something I can’t afford to pay, so it’s just going to have to go on the back burner. Housing, food, and then electricity. And then anything else after that.” The people we spoke with made difficult choices—some prioritized making regular payments, others prioritized paying to secure their basic needs. Either way, people sentenced to monetary sanctions faced extremely difficult choices that generated a great deal of stress.

Other interviewees spoke about how LFO debt affected their credit, making it hard for them to get loans or approval for apartment rental contracts. Delinquent debt that the courts trade to collections agencies will appear on credit scores as negative marks. Having this legal debt on one’s credit score was, as Geoff described it, like putting “a bad mark on your whole application process.” In a similar way, Lindsey from Minnesota summed up her anxiety about being able to get ahead of her payments: “Well first of all it gives me anxiety. Because I know that it’s there. And I have an anxiety disorder, just in general. It just stresses me out thinking about all this money. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to get a loan to buy a house or even a car. That alone debilitates me sometimes. I don’t think I’ll ever be able to get ahead because I can’t get credit.”

Again we see how the siphoning of financial resources leads to stress—and even debilitating anxiety—over whether individuals can make enough income to cover their daily expenses.

We see the ways in which the burden of LFO debt can exacerbate the restricted employment opportunities of those already discriminated against because of their criminal record. However, LFOs are even more frequently assessed to individuals found guilty of misdemeanor-level crimes (Kohler-Hausmann 2018). Thus the financial burden is spread over an even greater number of individuals who contact the criminal legal system than those “marked” by a felony conviction (Pager 2003). The interviewees illustrate how this unpayable debt leads to a constant pressure and balancing act of household budgets, takes resources away from children and destabilizes access to housing, credit, and food. This chronic stress functions as an additional punishment that strains relationships, affects the ability to be safe and healthy, and invades people’s constant thoughts.

SECONDARY STRESSORS: CONSEQUENCES OF PENAL DEPT

Several secondary stressors arouse for people who did not or could not pay their monetary sanctions regularly. These stressors included acute moments of stress, such as mandatory court summons to explain why they were not making payments, suspension of a driver’s license for nonpayment, and being arrested on warrants. Individuals also expressed chronic anxiety in relation to these stressors. For example, not being able to drive caused many interviewees chronic stress when they attempted to search for transportation for themselves or their children. Individuals also lived with a palpable fear of criminal legal surveillance and concerns over how criminal legal intervention might affect their lives. We outline these secondary stressors and their consequences in the following sections.

MANDATED COURT APPEARANCES

Variability is considerable across and within the states in terms of how courts monitor people, collect LFO debt, and sanction people for nonpayment. In most jurisdictions, people who owed debt were still required to appear in court hearings for review to explain why they had not been making payments and not showing up to these hearings could lead to serious consequences.6 Patricia, an African American woman from Illinois, described this cycle of review hearings as a matter-of-fact process for individuals who had trouble paying their court debt, pointing out that “if you don’t have stuff paid, then you have to keep coming to court. Don’t miss court or you’ll have a warrant.”

Kate, a respondent from Washington State, said that she missed her court date because she worked multiple jobs. She went to court to reschedule the date after missing her first appearance and was promptly arrested for failure to appear.

Honestly just missed the court date and when I went to go have it rescheduled, which was within reason, the DA [district attorney] was just like, “No she missed it.” I had a warrant for the failure to appear at the time because I missed my court date. I went immediately—the very next day—to my attorney and they rescheduled the court date by the end of the week. Say I missed my court date on Monday, I went the next day, which was Tuesday. She was able to get me back into the courtroom on Friday, to be able to try to have that court date rescheduled. The district attorney was there, had already issued a warrant for me for my failure to appear, and arrested me on it.

Moments like these, when the criminal legal system intervenes in the lives of people who owe debt can lead to acute moments of stress and anxiety: Will I get arrested? Will I go to jail? Beth Huebner and Sarah Shannon (2022, this volume) highlight a court observation when a person was threatened by a judge, who told them that if they did not complete their payment, they would not need to worry about their fine but would instead need to bring their “toothbrush” to court—meaning that they would be sent to jail. People described such instances with powerful emotions, which included fear and anxiety.

Many interviewees described an ongoing anxiety from being under such intensive criminal legal system surveillance. Court supervision remains in effect until people pay their penal debts in full. Respondents said that judges would frequently summon them into court to review payments even when they had no viable way of getting to court without relying on others or public transit. In many cases, participants had to take time off work to attend review hearings to discuss their LFO payments. Even when people did not have resources to make payments, they were mandated by the courts to attend hearings to explain their reasons for nonpayment—essentially, they were forced to display or perform their accountability to the court via their explanations (Martin et al. 2022, this volume; Harris 2016). Individuals faced not only specific moments of stress during these summoned court reviews, but also a perpetual sense of stress over when these reviews might happen, how responding to summons might affect their day-to-day lives, and the potential consequences if they cannot meet these obligations.

LOSING A DRIVER’S LICENSE

Another common concern was automatic driver’s license suspension.7 Suspension for nonpayment on court fines and fees is a regular practice across the states studied (Stewart et al. 2022, this volume; Martin et al. 2022, this volume). These policies had severe impacts on the ability of individuals to go to work, bring their children to school and childcare, make appointments, and go about their daily lives. Many people said they abided by their suspensions, doing their best to manage their inability to travel. Such decisions left many with ongoing stress about transportation needs. Others believed that their needs for transportation were too great, leading to anxious moments when they chose to drive with a suspended license.

For Jerry in Washington State, the suspension of his license meant that he had to rely on his fiancé to get him to and from work. Often when he was scheduled for double shifts at his job, he would need to call in to cancel his shift because he had no way of getting there. Sometimes he would drive himself regardless, even though his license was suspended. Jerry expressed his frustration at appearing before the court hours away from his home:

“Yeah, [the court is] like five hours away. I don’t have a license, like you said on top of it I work a full-time job. I’m not going to be able to come out here. They’re just like really fixated on me coming out here. It’s really inconvenient because I feel like, like today I had to drive five hours just to sit in a court room … Just for them to tell me that I have to come back for another hearing. This is a hearing I had to call off work.”

Jerry continued to describe his circumstances as a sort of “frogger” game trying to get on and off the freeway to work without getting stopped by the police:

“It’s basically me trying to get from my apartment across the I-205 into Oregon. It’s a short-ass drive. It’s only like a five-minute drive, whatever. But it’s like that long-ass drive is any moment I can get pulled up on by the police. They run my name or whatever, of course they’re going to see I’m on probation for driving without a license. And then that’s automatic pull over and automatic go to jail. So, that’s the only thing really hindering me from doing anything—leaving the house and trying to get to Portland.”

He concluded by describing his aim of paying off all his monetary sanctions so the anxiety could be alleviated:

“I can’t do anything without a license. So I’m trying to get all these court fees and court fines situated and out the way so I can get my license back and actually not have to worry about am I going to get pulled over today and go to jail and lose my job.”

Jerry’s story is similar to the distressing and demoralizing cycles other people described once they fell behind in making payments on their monetary sanctions. Interviewees frequently spoke of losing their driver’s licenses, which prevented them from getting to work or made it more difficult to maintain employment. Robert Stewart and his colleagues (2022, this volume) examine how LFOs exacerbate spatial and political inequalities and find that people described a great deal of limited resources and access to transportation. As a result, many people, particularly in rural locations, felt forced to drive their cars even when their licenses were suspended, constantly worrying about the repercussions if police caught them.

Overall, the anxiety of being sentenced LFOs was amplified by secondary stressors, which included criminal legal consequences related to not being able to pay the monetary sanctions off in full or regularly. These stressors brought both chronic stress about related issues such as transportation, warrants, and the potential of incarceration, and acute moments of anxiety from interactions with court officials and police. Many interviewees worried that if they did not meet their financial obligations they would have their driver’s licenses suspended, and be arrested, and put into jail. Incarceration for nonpayment could lead them to losing their jobs, putting their already precarious employment circumstances at even greater risk. Caught in this vicious cycle of nonpayment and further legal repercussions exacerbated the strain that many of the interviewees experienced.

SUMMARY: “I FEEL LIKE I WASN’T FREE”

These findings demonstrate the ways in which the inability to pay monetary sanctions can cause stress, anxiety, fear, and apprehension. The constant financial burden forced people to consider their penal debt daily, the financial drain threatened their structural stability and that of those close to them, and the looming possibility of criminal legal intervention injected fear and uncertainty into their lives. This stress and strain generated a feeling that LFOs were an intense and enduring punishment. As a result, many people described a kind of internalized punishment, whereby they were constantly policing their own behaviors so that they would remain fiscally compliant with the court.

This feeling was embodied and manifested as severe anxiety and mental exhaustion. These feelings limited respondent’s abilities to engage fully with their lives and the lives of their families without feeling constrained by their legal debt. Mark from Washington described feelings of sluggishness and being “slowed down” by the weight of his debts. The sentence of monetary sanctions punishment “trained” his mind to constantly focus on his finances and budgeting. Others, like Mitchell from Washington, said they would avoid leaving the house or performing regular activities with their families” “Yes. I didn’t want to go out … I didn’t want to do nothing with my kids. I don’t want to go. I don’t want to drive. I don’t want to do this. So, I stayed home. Slept a lot. I think that that has a lot to do with it, because I didn’t have no money.” Mitchell also put into words what other respondents had told us as well, that their legal debts made them feel like they were not actually free: “I feel like I wasn’t free because I owed. I didn’t have no income, my health and everything. It still stresses me … Well one, my kids. Saying to my kids that I couldn’t take them out, or do nothing with them. Emotionally, I was bad. I was a wreck. Now I feel a little bit more free, because I started to make payments. At least I’m trying, because if they arrest me, they can see now that I’m making payments, or progress.”

Although he had his physical freedom and was not incarcerated, Mitchell felt a kind of a mental confinement that was filled with anxiety, stress, and fear of criminal legal consequences. These feelings were intensified for many who felt like they would never be able to escape their punishment. Jacob from Washington described how the pressure of court debt affected all aspects of his life and became a heavy emotional burden:

“My health, my food, my housing, my employment. [My payments are] taken money out of that…. That budget, by paying for something like that. It affects me in emotional ways, personal ways, because I know there are other people in this situation. I met someone that has a substantial amount of debt that could never, ever get paid. $1.5 million.” Respondents like Jacob repeatedly described the frustration and pain they felt by being trapped in a debt world they saw as a never-ending punishment.

In part because of the unrelenting nature of this sentence, in addition to the economic and legal strain, the punishment of monetary sanctions becomes internalized and limits people’s visions of their possible “future selves” (Markus and Nurius 1986). This sense of angst impeded some interviewees from ever envisioning lives without fiscal debt; instead, they could only see their futures tethered to the criminal legal system (Harris 2016). The punishment became embodied affecting people’s life orientations and abilities to envision economically, physically, and mentally free lives. In essence, penal debt takes away the opportunities for people to have “clean dreams” (Harris 2011) and hope for their futures. The chronic and acute stress this sentence brings, and the internalization of the punishment, is one that differently punishes poor people from people with financial means and diminishes people’s overall well-being.

The punishment of monetary sanctions is a unique punishment option. Fines and fees are like probation in that they accompany constant court supervision until paid in full. However, the unique fiscal damage associated with monetary sanctions creates an additional cumulative and indeterminate punishment. Unlike incarceration or probation, monetary sanctions do not have a determinate release date by which they will be forgiven. The policy directives guiding incarcerative sentences purposefully shifted forty years ago to discrete determinate sentences to avoid, in part, racial disparities in outcome (Engen 2009; Miethe and Moore 1985). The perpetual nature of legal debt, the uncertainty of when the punishment and control will end, and the constant trade-off with securing basic living accommodations—such as food, housing, and health care—makes monetary sanctions a particularly egregious and excessive punishment.

DISCUSSION

In this article, we use the analysis of the nationally representative SHED data to introduce the potential connection between court debt and health in general. We find preliminary evidence that individuals with household court related debt both tend to have worse overall health than those who do not and are less able to afford their health-care needs. We used this evidence as additional motivation for exploring the role of stress as a possible contributing factor. We then analyzed interview data to illustrate the palpable emotional experiences that people face when they owe monetary sanctions. In discussions of their mental and emotional orientations to their debt, people described fear, constant stress, and anxiety about their inability to make complete or regular payments. Daily choices to save money for payment to the courts lead to chronically stressful environments for people having to choose between food, health care, and other needs. Although the sentencing of monetary sanctions was a primary stressor for many interviewees, most also faced tangible secondary stressors related to the legal consequences of their inability to pay. Because of their poverty, people faced moments of acute stress with court or police intervention that questioned and sanctioned nonpayment or from driving with licenses suspended related to the debt.8 This sense of urgency, to make regular payments, to drive to work, and to get out of debt, created a constant burden in their lives.

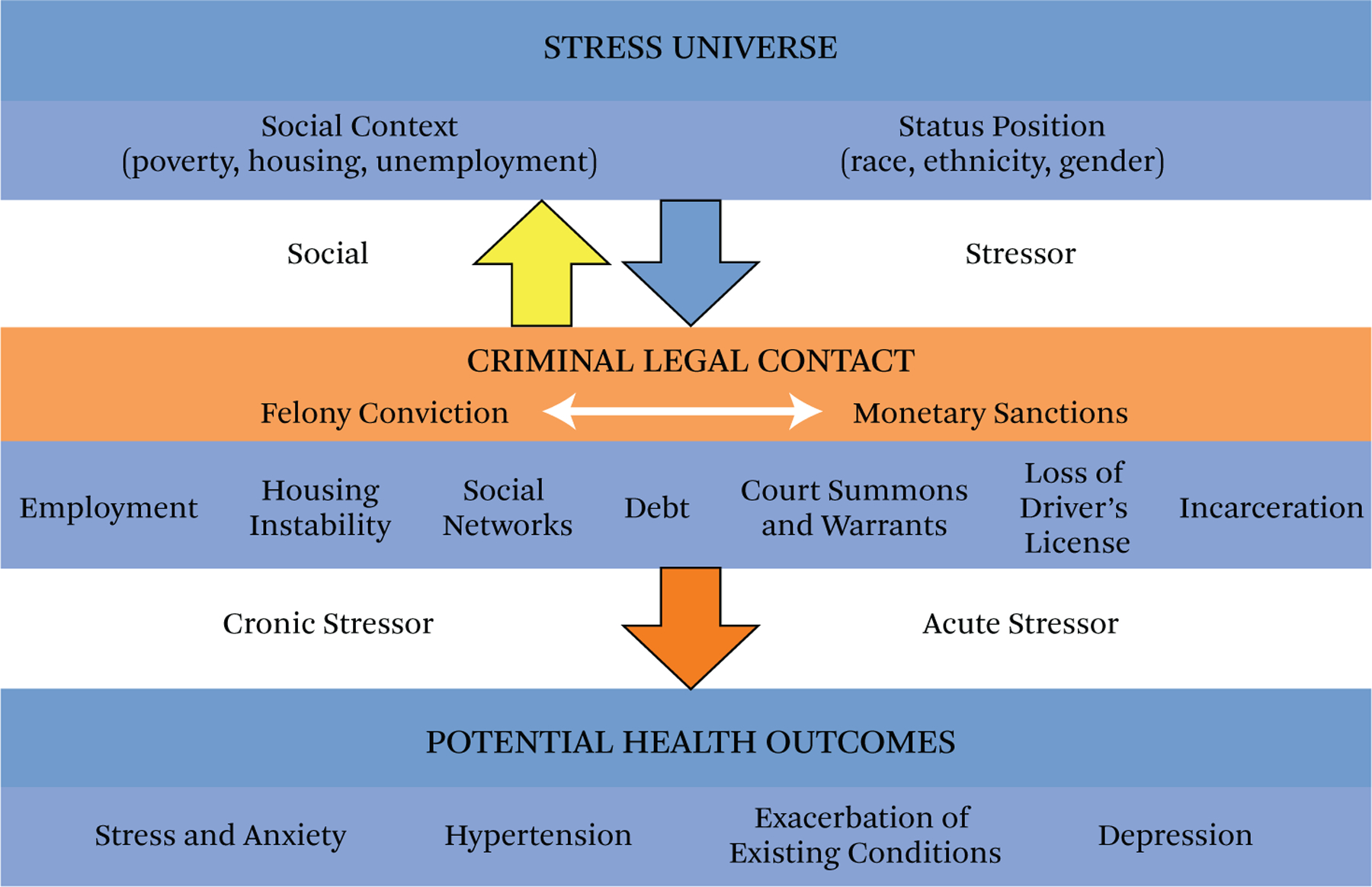

In figure 2, we illustrate how LFOs fit into the stress process of criminal legal entanglement. First, it is important to situate the findings within the broader context of the concept of a stress process—which is influenced by social context, such as income and employment characteristics—and is coupled with status positions, such as racial, ethnic, and gender categories. Second, a host of life dimensions are affected when individuals experience criminal legal contact, including their employment and income (Pager 2007; Western 2006), social networks (Comfort 2008), and affordable and quality housing (Remster 2019). Imposition of monetary sanctions also means that people face debt and strained finances (Harris 2016), loss of driver’s licenses (Shannon et al. 2020; Garrett, Modjadidi, and Crozier 2020), court summons and warrants (Cadigan and Kirk 2020), and even incarceration (Harris 2016). Added to this context are the racial disparities: Black, Native American, and Latino/a people face from police stops, arrests, prosecution, conviction, and incarceration. This is the stress universe for many people who are saddled with legal debt: they are poor and perpetually entangled within the U.S. criminal legal system.

Figure 2.

The Stress Universe Process and Criminal Legal Contact

Source: Authors’ tabulation.

We find that fines, fees, and other legal costs function as an institutional intervention that inhibits people’s ability to be emotionally healthy and stress free. It is important to note the bidirectionality of these factors. We do not presume directionality involving monetary sanctions, economic insecurity, and acute and chronic stress. We merely describe an association among these factors. In fact, as a wealth of research illustrates, criminal legal entanglement of other kinds may negatively influence individuals’ housing, employment, and income stability. In turn, owing monetary sanctions can negatively influence individuals’ legal status within the criminal system. What is clear is that, for most interviewees, this fiscal punishment is cumulative, adding to their already difficult circumstances. In this way, monetary sanctions add to the amassed disadvantage that poor and racialized people face, leading to mountains of palpable anxiety and stress. We argue that the cumulative effects of these structural forces, coupled with monetary sanctions, intensify the social determinants of health for people in these situations.

Furthermore, we find that the stress people feel related to penal debt became internalized, generating a constant form of social control for people too poor to pay. This internalized punishment leads to people continuously monitoring their own behaviors, including purchases for food, items for children, and where and when they travel within their local cities and towns. The chronic stress becomes its own punishment, one that will not dissipate until people can fully pay their legal debt. In other words, they felt like they could not be free until they had enough money to purchase their freedom (Pattillo and Kirk 2021). Thus the punishment of legal debt functions as a kind of dignity harm that affected individuals’ views of their worth as humans and free citizens.

An important limitation to our study is that we did not ask specifically about individuals’ health. Instead, we asked generally about potential stress related to the fiscal sanctions. This was deliberate because we did not want to assume negative health impacts or lead respondents to certain statements. That said, future work using surveys could include standardized health questions and questions about court debt in order to examine potential differences monetary sanctions create for people entangled in the criminal legal system. Future research could also conduct more analyses with the SHED data, such as multivariate analyses examining legal debt and health outcomes. Finally, an attempt should be made to disentangle the effects of felony conviction from monetary sanction debt. Larger samples of people convicted could compare and contrast those without monetary sanctions, those sentenced but were able to pay off, and those who carry debt.

An interesting future line of inquiry would be to examine interviews with people who did not find their monetary sanctions to be stressful. Some people in our study, albeit few, did describe their outstanding debt as too large to pay so they tried to ignore it and the related consequences. We could interpret these comments as flippant or in disregard to their obligation to the criminal legal system. We could also think of this orientation as being resilient—as self-protection mechanisms to cope and not internalize the stress and strain. Moreover, they may have experienced less anxiety and depression related to the penal debt they had no control over. We could also think of the relationship between penal debt and stress as curvilinear. People with small monetary sanctions may not feel much stress; however, as the amounts increase, the anxiety and pressure intensifies. When the amounts become insurmountable, people might then release the stress and try to ignore the debt or not think about it. Future research could pay attention to similarities and differences of people’s orientation to their outstanding debt in relation to the owed amounts and their abilities to make payments.

The policy implications are clear: sentencing people who have no ability to pay, or who are living in situations where payment would mean forgoing food, housing, transportation, medical care, and childcare necessities, to financial penalties is unjust and excessive.9 Doing so clearly increases their perceived stress and anxiety. Scholars have established that people who experience chronic and acute stress, with little or no ability to control that stress, have reduced health outcomes. As the World Health Organization states in a report on health equity, “This unequal distribution of health-damaging experiences is not in any sense a ‘natural’ phenomenon but is the result of a toxic combination of poor social policies and programs, unfair economic arrangements, and bad politics” (CSDH 2008, 1).

At the very least, states should reconsider statutes governing monetary sanctions to ensure that people who are unemployed (including children), eligible for state or federal assistance programs, or making barely enough money to pay other monthly living expenses should not be sentenced to fiscal penalties. Further, the secondary stressors related to the sentencing of monetary sanctions, such as regular court summons and suspension of driver’s licenses for people too poor to pay, are egregious and never-ending punishments. States should desist from attaching such pernicious consequences, which for the most part become a punishment for only the poor to serve. If used, monetary sanctions should not be excessive and should be proportionate to what people can pay to avoid the triggering of chronic and acute stress and should end within a certain period (as is incarceration and probation).

Our aim was to outline an agenda for examining how the punishment of monetary sanctions may be a pivotal legal intervention that negatively affects the emotional health of people entangled in the criminal legal system. We argue that the system of monetary sanctions is clearly an underexamined dimension to the social determinants of health. A pioneer in studying the social determinants of health, David Williams writes, “inequalities in health are created by larger inequalities in society. Their existence reflects the successful implementation of social policies. Eliminating them requires political will and a commitment to comprehensive and sustained approaches to improve living and working conditions” (2012, 13). Until our society and lawmakers develop the will to address the disparities created by the criminal legal system, the stress and related anxiety associated with criminal legal entanglement, including the sentencing of monetary sanctions, will endure.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to the reviewers for their substantive and theoretical suggestions for strengthening our analysis. This research was funded by a grant to the University of Washington from Arnold Ventures (Alexes Harris, PI). We thank the faculty and graduate student collaborators of the Multi-State Study of Monetary Sanctions for their intellectual contributions to the project. Partial support for this research came from a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant, P2C HD042828, to the Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology at the University of Washington.

Footnotes

1. The inability of individuals to pay their LFOs, as well as laws that do not allow for unpayable LFOs to be waived, means that legal debt could represent a permanent punishment for many people (Harris 2016).

2. Others have expanded the model to develop a family stress model to better understand inequality between families (Turney and Sugie 2021). We do not explore this expanded model here, but the connection between monetary sanctions and familial health dynamics is an important avenue for future research (see Boches et al. 2022, this volume).

3. Washington, California, Texas, New York, Minnesota, Illinois, Georgia and Missouri (for a description of study sites, see Harris, Pattillo, Sykes 2022, this volume).

4. Many people who are marginalized through poverty and criminal legal contact are underrepresented in national survey data.

5. For a detailed examination of the connection between monetary sanctions and housing difficulties, see Pattillo, Harris, and Sykes 2022, this volume.

6. For example, during the Washington State court observations, nearly every individual reviewed was found nonwillful because of indigency or some other barrier to payment. Individuals are rarely found to have willfully chosen not to pay court debt, but are still frequently called in to court to have their ability to pay reviewed.

7. Many traffic and driving under the influence convictions in Washington result in the automatic suspension of an individual’s driver’s license. Individuals may not have their license reinstated until all LFOs are paid off. See Washington State Department of Licensing, “Types of Suspensions,” https://www.dol.wa.gov/driverslicense/suspensions.html (accessed August 12, 2021).

8. Regardless of whether their decisions to drive on suspended licenses was morally right, many of the people we interviewed felt they had no other options. To be complicit with their fiscal sentences, they felt they needed to drive to get to work to make payments.

9. For further discussion of the policy implications of this research, see Friedman et al. 2022, this volume.

Contributor Information

ALEXES HARRIS, University of Washington, United States.

TYLER SMITH, Department of Sociology at the University of Washington, United States..

REFERENCES

- Amick Benjamin III, Levine Sol, Tarlov Alvin R., and Walsh Diana Chapman, eds. 1995. Society and Health Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barton Kristine A, Blanchard Edward B, and Hickling Edward J.. 1996. “Antecedents and Consequences of Acute Stress Disorder Among Motor Vehicle Accident Victims.” Behaviour Research and Therapy 34(10): 805–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger Ingrid A., Redmond Nicole, Steiner John F., and Hicks LeRoi S.. 2011. “Health Disparities and the Criminal Justice System: An Agenda for Further Research and Action.” Journal of Urban Health 89(1): 98–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boches Daniel J., Martin Brittany T., Giuffre Andrea, Sanchez Amairini, Sutherland Aubrianne L., and Shannon Sarah K.S.. 2022. “Monetary Sanction and Symbiotic Harms” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 8(2): 98–115. DOI: 10.7758/RSF.2022.8.2.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronson Jennifer, and E. Ann Carson. 2019. “Prisoners in 2017.” BJS Bulletin NCJ 252156. Washington: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics

- Cadigan Michele, and Kirk Gabriella. 2020. “On Thin Ice: Bureaucratic Processes of Monetary Sanctions and Job Insecurity.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 5(1): 113–31. DOI: 10.7758/RSF.2020.6.1.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadigan Michele, and Smith Tyler. 2021. “‘Are You Able-Bodied?’ Embodying Accountability in the Modern Criminal Justice System.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 37(1): 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comfort Megan. 2008. Doing Time Together: Love and Family in the Shadow of the Prison Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva (CSDH). 2008. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer Robert, O’Connor Jason C., Freund Gregory G., Johnson Rodney W, and Kelley Keith W. 2008. “From Inflammation to Sickness and Depression: When the Immune System Subjugates the Brain.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9(1): 46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engen Rodney L. 2009. “Assessing Determinate and Presumptive Sentencing-Making Research Relevant.” Criminology and Public Policy 8(2): 323–36. [Google Scholar]

- Reserve Federal. 2020. “Survey of Household Economics and Decision Making.” Washington, DC: Federal Reserve Board. Accessed May 17th, 2021. https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/shed_data.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Brittney, and Patillo Mary. 2019. “Statutory Inequality: The Logics of Monetary Sanctions in State Law. “ RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 5(1): 174–96. DOI: 10.7758/RSF.2019.5.1.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Brittany, Harris Alexes, Huebner Beth M., Martin Karin D., Pettit Becky, Shannon Sarah K.S, and Sykes Bryan L.. 2022. “What Is Wrong with Monetary Sanctions? Directions for Policy, Practice, and Research.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 8(1): 221–43. DOI: 10.7758/RSF.2022.8.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett Brandon L., Modjadidi Karima, and Crozier William E.. 2020. “Undeliverable: Suspended Driver’s Licenses and the Problem of Notice.” UCLA Criminal Justice Law Review 4(1). Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5fv5m8pm. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser Ronald, and Kiecolt-Glaser Janice K. 2005. “Stress-Induced Immune Dysfunction: Implications for Health.” Nature Reviews Immunology 5(3): 243–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman Erving. 1961. Asylums: Essays on the Social Situation of Mental Patients and Other Inmates Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hammen Constance, Kim Eunice Y., Eberhart Nicole K., and Brennan Patricia A.. 2009. “Chronic and Acute Stress and the Prediction of Major Depression in Women.” Depress Anxiety 26(8): 718–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammons Brianna. 2021. “Tip of the Iceberg: How Much Criminal Justice Debt Does the U.S. Really Have?” New York: Fines and Fees Justice Center. Accessed August 12, 2021. https://finesandfeesjusticecenter.org/content/uploads/2021/04/Tip-of-the-Iceberg_Criminal_Justice_Debt_BH1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Harris Alexes. 2011. “Constructing Clean Dreams: Accounts, Future Selves, and Social and Structural Support as Desistance Work.” Symbolic Interaction 34(1): 63–85. [Google Scholar]

- <au>———</au>. 2016. A Pound of Flesh: Monetary Sanctions as a Punishment for Poor People New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Harris Alexes, Pattillo Mary, and Sykes Bryan L.. 2022. “Studying the System of Monetary Sanctions.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 8(1): 1–33. DOI: 10.7758/RSF.2022.8.1.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Alexes, Smith Tyler, and Obara Emmi. 2019. “Justice ‘Cost Points’: Examination of Privatization Within Public Systems of Justice.” Crime and Public Policy 18(2): 343–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidt Timo, Sager Hendrik B., Courties Gabriel, Dutta Partha, Iwamoto Yoshiko, Zaltsman Alex, Muhlen Constantin von Zur, Bode Christoph, Fricchione Gregory L, Denninger John, Lin Charles P, Vinegoni Claudio, Libby Peter, Swirski Filip K, Weissleder Ralph, and Nahrendorf Matthias. 2014. “Chronic Variable Stress Activates Hematopoietic Stem Cells.” Nature Medicine 20(7): 754–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfield Paul, Maschi Tina, Raskin Helene, White Leah Goldman, and Loeber Traub Rolf. 2006. “Mental Health and Juvenile Arrests: Criminality, Criminalization, or Compassion?” Criminology 44(30): 593–630. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner Beth M., and Shannon Sarah K.S. 2022. “Private Probation Costs, Compliance, and the Proportionality of Punishment: Evidence from Georgia and Missouri.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 8(1): 179–99. DOI: 10.7758/RSF.2022.8.1.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaeble Danielle, and Cowhig Mary. 2018. “Correctional Populations in the United States, 2016.” Key Statistics: Total Correctional Population. NCJ 251211 Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- Kohler-Hausmann Issa. 2018. Misdemenorland: Criminal Courts and Social Control in the Age of Broken Windows Policing Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Link Nathan W., Powell Kathleen, Hyatt Jordan M. and Ruhland Ebony L.. 2021. “Considering the Process of Debt Collection in Community Corrections: The Case of the Monetary Compliance Unit.” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 37(1): 128–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lucassen Paul J., Pruessner Jens, Sousa Nuno, Almeida Osborne F.X, Dam Anne Marie Van, Rjkowska Grazyna, Swaab Dick F, and Czéh Boldizsár. 2014. “Neuropathology of Stress.” Acta Neuropathologica 127(1): 109–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariotti Agnese. 2015. “The Effects of Chronic Stress on Health: New Insights into the Molecular Mechanisms of Brain-Body Communication.” Future Science OA 1(3): FSO23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus Hazel, and Nurius Paula. 1986. “Possible Selves.” American Psychologist 41(9): 954–69. [Google Scholar]

- Martin Karin D., Spencer-Suarez Kimberly, and Kirk Gabriela. 2022. “Pay or Display: Monetary Sanctions and Performance of Accountability and Procedural Integrity in New York and Illinois Courts.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 8(1): 128–47. DOI: 10.7758/RSF.2022.8.1.06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Massoglia Michael. 2008a. “Incarceration as Exposure: The Prison, Infectious Disease, and Other Stress-Related Illnesses.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 49(1): 56–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoglia Michael, and Pridemore William Alex. 2015. “Incarceration and Health.” Annual Review of Sociology 4(1): 291–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]