Abstract

Objective:

This pilot open trial examined the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness of Written Exposure Therapy (WET), a 5-session evidence-based intervention for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during pregnancy. Participants were pregnant women with comorbid PTSD and substance use disorder (SUD) receiving prenatal care in a high risk obstetrics-addictions clinic.

Methods:

A total of 18 participants with probable PTSD engaged in the intervention, and 10 completed the intervention and were included in outcome analyses. Wilcoxon’s Signed-Rank analyses were used to evaluate PTSD and depression symptoms and craving at pre-intervention to post-intervention and pre-intervention to the 6-month postpartum follow-up. Engagement and retention in WET and therapist fidelity to the intervention manual were used to assess feasibility. Quantitative and qualitative measures of patient satisfaction were used to assess acceptability.

Results:

PTSD symptoms significantly decreased from pre-intervention to post-intervention (S = 26.6, p = 0.006) which sustained at the 6-month postpartum follow-up (S = 10.5, p = 0.031). Participant satisfaction at post-intervention was high. Therapists demonstrated high adherence to the intervention and excellent competence.

Conclusions:

WET was a feasible and acceptable treatment for PTSD in this sample. Randomized clinical trial studies with a general group of pregnant women are needed to expand upon these findings and perform a full-scale test of effectiveness of this intervention.

Keywords: Posttraumatic stress disorder, Written exposure therapy, Depression, Pregnancy, Substance use disorder

1. Introduction

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) during pregnancy is highly prevalent, particularly among racial and ethnic minoritized and low-income individuals. While PTSD affects 8% of pregnant individuals in the general U.S. population [1], PTSD affects up to 30% of pregnant individuals seen in low-resource settings [2], where many low-income and minoritized groups receive care (vs. 3% observed in high-resource settings) [1]. PTSD during pregnancy is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, including preterm birth, low infant birthweight, postpartum depression, and impaired maternal-infant bonding [3–5]. These adverse peritnatal outcomes affect long-term cognitive, social, emotional, and physical development [6,7]. Despite the strong association between PTSD and adverse perinatal outcomes, screening and treatment during pregnancy is largely unavailable in usual care, and there is a lack of PTSD treatment in the perinatal period [8].

Pregnant individuals with comorbid PTSD and Substance Use Disorder (PTSD/SUD) are a subgroup that is at especially high risk for adverse perinatal outcomes [4,9]. Substance use during pregnancy is increasing [10], with a particular increase observed for opiate use during pregnancy (127% increase from 1998 to 2011) [10]. An estimated 63% of pregnant individuals in a substance use residential program have PTSD [11]. Pregnant individuals with co-occurring PTSD/SUD have higher rates of suicide attempts compared to those with SUD alone [12], suggesting the increased risk posed by PTSD among pregnant individuals with SUD. Studies have found that most individuals (83%) abstain from at least one problematic substance (primarily alcohol, cocaine, and/or marijuana, but not cigarettes) during pregnancy [13]. Yet, 80% of individuals relapse in the first few months postpartum [13], and overdose risk is highest 7–12 months post-delivery [14]. Marked by increased engagement in care, reduced or halted substance use, and increased motivation for psychosocial treatment [15], pregnancy presents an ideal PTSD treatment window for this vulnerable and otherwise difficult-to-engage population. However, there has been limited research on treatment of PTSD during pregnancy for this population. To our knowledge there has been only one previous study examining a one session psychoeducation intervention for pregnant women with PTSD/SUD [16], and none examining a trauma-focused intervention for PTSD.

The current study aims to examine the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effectiveness of Written Exposure Therapy (WET) for PTSD [17] for pregnant individuals receiving care in a high risk obstetrics-addictions clinic. We chose WET due to it’s brevity, low therapist and patient burden, and documented efficacy and non-inferiority against more time-intensive first-line evidence-based treatments for PTSD [18–21]. As a hybrid 1 nonrandomized effectiveness-implementation pilot trial [22], the study aims to test feasibility and acceptability of WET in a real-world obstetrics setting while gathering information on implementation.

2. Methods

2.1. Participant recruitment and screening procedures

Individuals being seen for pregnancy care in Project Recovery, Empowerment, Social Services, Prenatal care, Education, Community and Treatment (RESPECT), a specialized obstetrics-addictions clinic, from October 2019 to June 2021 were screened for PTSD as part of their initial prenatal appointment using the Primary Care PTSD Screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5) [23]. The PC-PTSD-5 assesses for probable PTSD based on endorsement of trauma exposure and five symptom items (i.e., intrusions, avoidance, hyperarousal, and cognitive/mood symptoms). Women who screened positive for probable PTSD (i.e., score ≥ 3 on PC-PTSD-5) were informed of the study by clinic staff and, if interested, given a warm handoff to research staff for a study screening visit to assess full study eligibility. Clinic-wide screening and enrollment was paused from March–September 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the study screening visit, participants completed the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5) [24] to identify lifetime traumatic event exposures and select an index Criterion A event, and then completed the past month PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) [25] to assess all 20 symptoms of PTSD. Inclusion criteria included pregnant women who: a) were 18 years of age or older, b) able to read, write, and speak English, c) identified a Criterion A traumatic event exposure, and d) had probable PTSD diagnosis based on either a PCL-5 score ≥ 33 [26] or clinical judgement. Clinical exceptions were made to enroll three women whose PCL scores were below 33 based on clinical judgement that they were underreporting symptoms due to high levels of PTSD avoidance, and therefore, WET was appropriate. Women were not referred to the study if clinic staff determined that a higher level of care was needed at the time (i.e., treatment in detox or inpatient settings).

2.2. Study procedures

Eligible and interested participants completed a pre-intervention study visit, where they completed written informed consent, self-report measures, and were assigned a study therapist. Then, they received five, 50-min individual WET sessions. An additional session for clinically indicated reasons relevant to the trauma-focused therapy (e.g., change in index Criterion A event mid-treatment) was allowed. WET was offered within usual care at the time, which included in-person or video telehealth. Follow-up study visits occurred at post-intervention and at 6-months postpartum, where participants completed self-report measures and an audio-recorded interview with the research assistant (RA). All research procedures were approved by the institutional review board.

2.3. Recruitment flow

See Fig. 1 for a detailed flowchart of participant recruitment, attrition, and inclusion. Clinic-wide screening yielded 52 (50.4% positive rate) potentially eligible women, which is consistent with previous literature regarding rate of PTSD/SUD comorbidity [27]. Of these, 25 were deemed eligible and enrolled. Seven women were lost to follow-up prior to starting WET and 18 initiated WET. Of these, 10 completed WET and 8 dropped out of WET. Despite contact attempts, we were unable to collect follow-up assessments on the 8 women who dropped out of WET.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram.

CONSORT diagram detailing the flow of participant recruitment, attrition, and inclusion. Abbreviations: PC-PTSD-5 = Primary Care PTSD Screen for the DSM-5; TAB = therapeutic abortion; SAB = spontaneous abortion; LTFU = lost to follow-up.

2.4. WET treatment

WET is an effective treatment for PTSD and is noninferior to other gold standard PTSD treatments (e.g., Cognitive Processing Therapy) and has lower dropout rates [18–21]. As such, WET is now included, along with Cognitive Processing Therapy and Prolonged Exposure, on the list of expert-recommended PTSD treatments [28], and its implementation advantages (i.e., brevity, low therapist and patient time burden) suggest the promise of this intervention for usual care in obstetrics (OB) settings. WET consisted of five, 45–60-min individual therapy sessions that cover treatment rationale, PTSD psychoeducation, and 30-min writing assignments [17]. The writing assignments begin with a focus on describing the most distressing trauma event, with the incorporation of emotions and thoughts experienced during the event, and evolve over the sessions to a focus on describing the impact of the event on one’s life. After each writing assignment, therapists spent approximately 10 min checking in with the participant. Check-ins focused on participants’ reactions to the writing process. Although unstructured, a variety of techniques were used as appropriate, including socratic questioning to challenge thoughts the patient brought up, validation/support, and/or reflection on new insights. Per protocol, writings were collected, read, and reviewed by the clinician between sessions and therapist provided feedback at the beginning of each session regarding how well participants followed instructions in the prior session. Although WET does not include between session assignments, patients were encouraged to allow themselves to experience thoughts and feelings that arise related to the trauma rather than trying to avoid them. Therapists would also frequently remind participants of the treatment rationale to motivate participants (i.e., confronting trauma memories is necessary in order to facilitate recovery).

2.5. Study therapists, training, and consultation

Study therapists were three embedded clinical social workers in OB and one trainee in a mental health counseling Master’s program. All study therapists completed the same 5-h pre-recorded presentation by the co-developer of WET, which focused on providing background information on WET development and testing, and a session-by-session overview. Study therapists then completed a 2-h in-person study-specific training with two of the study authors (first and last authors) with a focus on clinical and study procedures and applying WET in this setting (e.g., case demonstrations). Study therapists received weekly group consultation with audio review and written feedback from these two study authors. Individual consultation was also available as needed. Consultation meetings focused on reviewing the writing assignments and discussing what feedback to provide to the patient at the next session, problem-solving clinical challenges, combating patient avoidance, and troubleshooting implementation barriers. The original objective was for the embedded clinical staff in OB to deliver WET. However, the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily shifted the clinical duties of study therapists to pandemic response. This required that the PIs served as study therapists for three participants actively engaged in WET.

2.6. Measures

2.6.1. Demographic information

At the pre-intervention visit, participants reported demographic information, including age, race, ethnicity, educational status, relationship status, housing situation, employment status, and household income. We used this information to characterize the sample.

2.6.2. Lifetime trauma exposure

At the pre-intervention visit, participants completed the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale (ACES) [29], a 10-item self-report measure assessing exposure to stressful events occurring prior to the age of 18, including domestic violence, parental separation/divorce, parental mental health condition, parental substance use problem, parental imprisonment, or physical, emotional, and/or sexual abuse. The number of endorsed items were summed (range 0–10) and used to characterize the sample. Participants also completed the LEC-5 [24] at pre-intervention to assess lifetime exposure to 16 potentially traumatic events. For each event, participants noted whether the event “happened to them,” “witnessed it,” “learned about it,” “part of my job,” “not sure,” and/or “doesn’t apply.” We used the LEC-5 to characterize the sample and select an index Criterion A event to focus on during WET.

2.6.3. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms

PTSD symptoms were assessed at each study visit using the PCL-5 [25], a 20-item measure which assesses the severity of PTSD symptoms anchored to the Criterion A event (i.e., worst/index event). Participants rated the extent to which each symptom (e.g., “repeated, disturbing, and unwanted memories of the stressful experience”) has bothered them in the past week from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Scores were summed and range from 0 to 80. The PCL-5 has demonstrated sound psychometric properties [30] and has identified a cut-off score of ≥33 to indicate a probable PTSD diagnosis [26]. Further, the PCL-5 has yielded similar estimates of PTSD symptoms following treatment to a gold standard clinician-administered assessment [31].

2.6.4. Depression symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed at each study visit using two measures: the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [32] and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) [33]. The PHQ-9 assesses each diagnostic symptoms of depression, whereas the EPDS assesses a broader subset of symptoms, including both depressive and anxiety symptoms relevant to assessment of perinatal depression. The EPDS is a 10-item measure with satisfactory sensitivity and specificity [32]. For each item, participants indicated how they felt within the past 7 days (e.g., “I have felt sad or miserable”) from 0 (not at all) to 3 (yes, most of the time). Scores were summed and range from 0 to 30. A conservative cut-off score of ≥13 has been determined to identify those with possible postpartum depression (PPD) [34].

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item measure of depressive symptoms that has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of depression severity [33]. Participants rated each of the nine DSM-5 [35] depression diagnostic criteria (e.g., “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless”) from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Scores were summed and range from 0 to 27 with scores of ≥10 indicating moderate to severe depressive symptoms.

2.6.5. Craving

The intensity of substance use cravings was assessed at all study visits using the 3-item version [36] of the craving scale developed by Weiss and colleagues [37,38]. The craving scale was initially developed to assess cravings related to cocaine use with high internal consistency and validity [36] and has displayed adequate internal consistency and validity when adapted for other substances [39,40]. We only used the first craving item (i.e., “how much do you currently crave your substance of choice”), scored on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely) in analyses.

2.6.6. Feasibility

Feasibility was examined based on engagement and retention in WET, and intervention fidelity. This included examining the proportion of women who engaged (i.e., the number of women who initiated treatment divided by the number of women who were eligible and agreed to participate) and the proportion of women who completed treatment (i.e., the number of women who completed at least four WET sessions divided by the total number of women who engaged in at least one WET session). To determine fidelity, 20% of therapy recordings were reviewed by two raters (who were not the therapist for that session) for adherence (0–100%) and competence, defined as how skillfully each component was delivered (1 = poor to 7 = excellent) across various domains using established WET fidelity checklists.

2.6.7. Acceptability

Participant satisfaction with WET (i.e., acceptability) was assessed during the post-intervention visit using the 8-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) [41,42]. The CSQ-8 shows high internal consistency [41,42]. Items were scored on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (low satisfaction) to 4 (high satisfaction). Total scores ranged from 8 to 32, with higher scores indicating greater overall satisfaction.

Acceptability was also assessed with 30-min semi-structured interviews at the post-intervention and 6-month postpartum visits. Participants were asked open-ended questions pertaining to satisfaction with the intervention, changes in functioning, barriers/facilitators to engagement, and recommendations to improve WET. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed by study staff, and de-identified for qualitative analysis.

2.6.8. Perinatal outcomes

Perinatal outcomes were extracted from the medical chart to characterize the sample, including maternal (hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes) and child (intrauterine growth restriction, gestational age at delivery, and birthweight) medical information.

2.7. Data analytic plan

2.7.1. Quantitative

Treatment outcome was assessed by examining changes in PTSD symptoms (primary outcome), depression symptoms, and craving from pre-intervention to post-intervention and 6-months postpartum. Only women who completed WET were included in these analyses as there was no follow-up data available for those that dropped out. Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.4 [43]. The data were not normally distributed for all the mental health symptom measures. Given the small sample size and lack of normality, we utilized non-parametric Wilcoxon’s Signed-Rank tests to compare assessments between pre-intervention vs. post-intervention and pre-intervention vs. 6-months postpartum.

2.7.2. Qualitative

Participant interviews (n = 8) were coded using content analysis [44]. The coding team consisted of five study staff, including two doctoral-level psychologists, one Master’s-level research coordinator, one Bachelor’s-level RA, and one undergraduate RA. The coding team reviewed the same set of transcripts to develop preliminary themes and continued to meet weekly to discuss discrepancies and refine the codebook as necessary until saturation was reached (n = 3). Three members of the coding team applied the codebook to the same transcripts and achieved inter-rater reliability of 95.4% across 25% of transcripts (n = 2) prior to double-coding the remaining transcripts. NVivo 10 (QSR International) was used to manage qualitative data.

3. Results

3.1. Participant characteristics

See Table 1 for sample characteristics (N = 18). Completers (n = 10) were mostly non-Hispanic White (70%), not married (100%), living in a substance use residential program (70%), not currently working (70%), and had a household income of less than $15,000 (80%). Their mean ACES score was 6.6 (SD = 1.99), and they reported an average of 6.5 lifetime potentially traumatic events, with 90% reporting a physical assault, assault with a weapon, and sexual assault. In terms of obstetrics characteristics among completers, 70% had a maternal medical condition such as hypertension during pregnancy, 20% experienced a preterm delivery (i.e., delivery <37 weeks gestational age), and 30% had a baby born at low infant birthweight (i.e., infant birthweight <2500 g). Completers were more likely to have a maternal obstetrical medical condition during pregnancy as compared to non-completers (70% vs. 25%) and were more likely to report higher craving at pre-intervention (M = 3.60, SD = 2.99) as compared to non-completers (M = 0.75, SD = 1.17). Of note, the demographics of the study sample are reflective of the obstetrics-addiction clinic where the study took place.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by Total Intent to Treat Sample, Completers, and Non-completers.

| Intent To Treat Sample (n = 18) | Completed WET (n = 10) | Did not complete WET (n = 8) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | X2 | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity/Race | 4.65 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 11 (61.11%) | 7 (70.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | |

| Hispanic White | 1 (5.55%) | 1 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4 (22.22%) | 1 (10.0%) | 3 (37.50%) | |

| Hispanic Black | 1 (5.55%) | 1 (10.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Other | 1 (5.55%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (12.50%) | |

| Minority Status | 0.748 | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 11 (61.11%) | 7 (70%) | 4 (50%) | |

| Minority | 7 (38.88%) | 3 (30%) | 4 (50%) | |

| Education | 2.306 | |||

| Some high school, no diploma | 5 (27.77%) | 3 (30%) | 2 (25.00%) | |

| High School | 5 (27.77%) | 4 (40%) | 1 (12.50%) | |

| Some college/associates degree | 8 (44.44%) | 3 (30%) | 5 (62.50%) | |

| Relationship Status | 5.625 | |||

| Single | 6 (33.33%) | 3 (30%) | 3 (37.50%) | |

| In a relationship but living separately | 9 (50.0% | 7 (70%) | 2 (25%) | |

| Married or cohabitating | 3 (16.66%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (37.50%) | |

| Living Situation | 2.41 | |||

| Rent or own house/apartment | 4 (22.22%) | 1 (10%) | 3 (37.50%) | |

| Live with friend and not paying rent | 4 (22.22%) | 2 (20%) | 2 (25%) | |

| Substance use residential program | 10 (55.6%) | 7 (70%) | 3 (37.50%) | |

| Employment Status | 0.382 | |||

| Working full or part time | 4 (22.22%) | 3 (30%) | 1 (12.50%) | |

| Not working | 14 (77.77%) | 7 (70%) | 7 (87.50%) | |

| Household Income | 0.310 | |||

| Less than $15,000 | 12 (66.66%) | 8 (80%) | 4 (50%) | |

| $15,000 - $35,000 | 5 (27.77%) | 2 (20%) | 3 (37.50%) | |

| $35,000 - $45,000 | 1 (5.55%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (12.50%) | |

| Potentially Traumatic | ||||

| Events (PTE) | ||||

| Fire or explosion | 4 (22.2%) | 2 (20.0%) | 2 (25%) | 0.064 |

| Transportation accident | 15 (83.3%) | 7 (70.0%) | 8 (100.0%) | 2.880 |

| Serious accident at work/home, or during recreational activity | 4 (22.2%) | 1 (10.0%) | 3 (37.5%) | 1.945 |

| Physical assault | 17 (94.4%) | 9 (90.0%) | 8 (100.0%) | 0.847 |

| Assault with a weapon | 14 (77.8%) | 9 (90.0%) | 5 (62.50%) | 1.945 |

| Sexual assault | 15 (83.3%) | 9 (90.0%) | 6 (75.0%) | 0.720 |

| Other unwanted sexual experience | 16 (88.9%) | 9 (90.0%) | 7 (87.5%) | 0.028 |

| Captivity | 4 (22.2%) | 4 (40.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 4.114+ |

| Life threatening illness or injury | 5 (27.8%) | 3 (30.0%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0.055 |

| Sudden violent deatha | 7 (38.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (12.50%) | 1.32 |

| Sudden accidental deatha | 10 (55.6%) | 4 (40.0%) | 3 (37.50%) | 0.012 |

| Severe human suffering | 1 (5.6%) | 6 (60.0%) | 4 (50.0%) | 0.180 |

| Serious injury, harm, or death you caused to someone else | 2 (11.1%) | 2 (20.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.80 |

| Stayed engaged in Project RESPECT | 15 (83.33%) | 9 (90.0%) | 6 (75.0%) | 0.720 |

| Any relapse during study period | 8 (44.4%) | 5 (50.0%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0.281 |

| Perinatal Outcomes | ||||

| Maternal obstetrical medical condition (e. g., hypertension) | 9 (50.0%) | 7 (70.0%) | 2 (25.0%) | 3.60+ |

| Intrauterine growth restriction | 7 (38.9%) | 4 (40.0%) | 3 (37.50%) | 0.012 |

| Pre-term delivery (gestational age < 37 weeks) | 4 (22.22%) | 2 (20%) | 2 (25.0%) | 0.064 |

| Low infant birthweight (infant birthweight <2500 g) | 6 (33.3%) | 3 (30%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0.113 |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | t | |

| Age | 29.17 (4.26) | 29.70 (4.19) | 28.50 (4.53) | − 0.582 |

| Time 1 PCL-5 Total Score | 51.00 (17.30) | 47.10 (18.94) | 55.88 (14.73) | 1.074 |

| Time 1 EPDS Total Score | 15.39 (3.74) | 15.40 (4.60) | 15.38 (2.62) | − 0.014 |

| Time 1 PHQ-9 Total Score | 13.00 (4.34) | 12.40 (4.83) | 13.75 (4.83) | 0.645 |

| Time 1 Craving | 2.33 (2.72) | 3.60 (2.99) | 0.75 (1.17) | − 2.54* |

| Number of unique PTEs endorsed | 6.87 (1.82) | 6.50 (1.78) | 6.13 (1.64) | − 0.459 |

| ACES total score | 7.0 (2.03) | 6.63 (1.99) | 7.50 (2.17) | 0.783 |

| Number of unplanned visits to OB clinic | 5.72 (2.85) | 5.00 (2.36) | 6.63 (3.29) | 1.22 |

PTE exposure is based on participant endorsement of directly experiencing an event on the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). PCL-5 = PTSD Symptom Checklist for DSM-5; EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; ACES = Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale.

Includes participant endorsement of witnessing item.

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05.

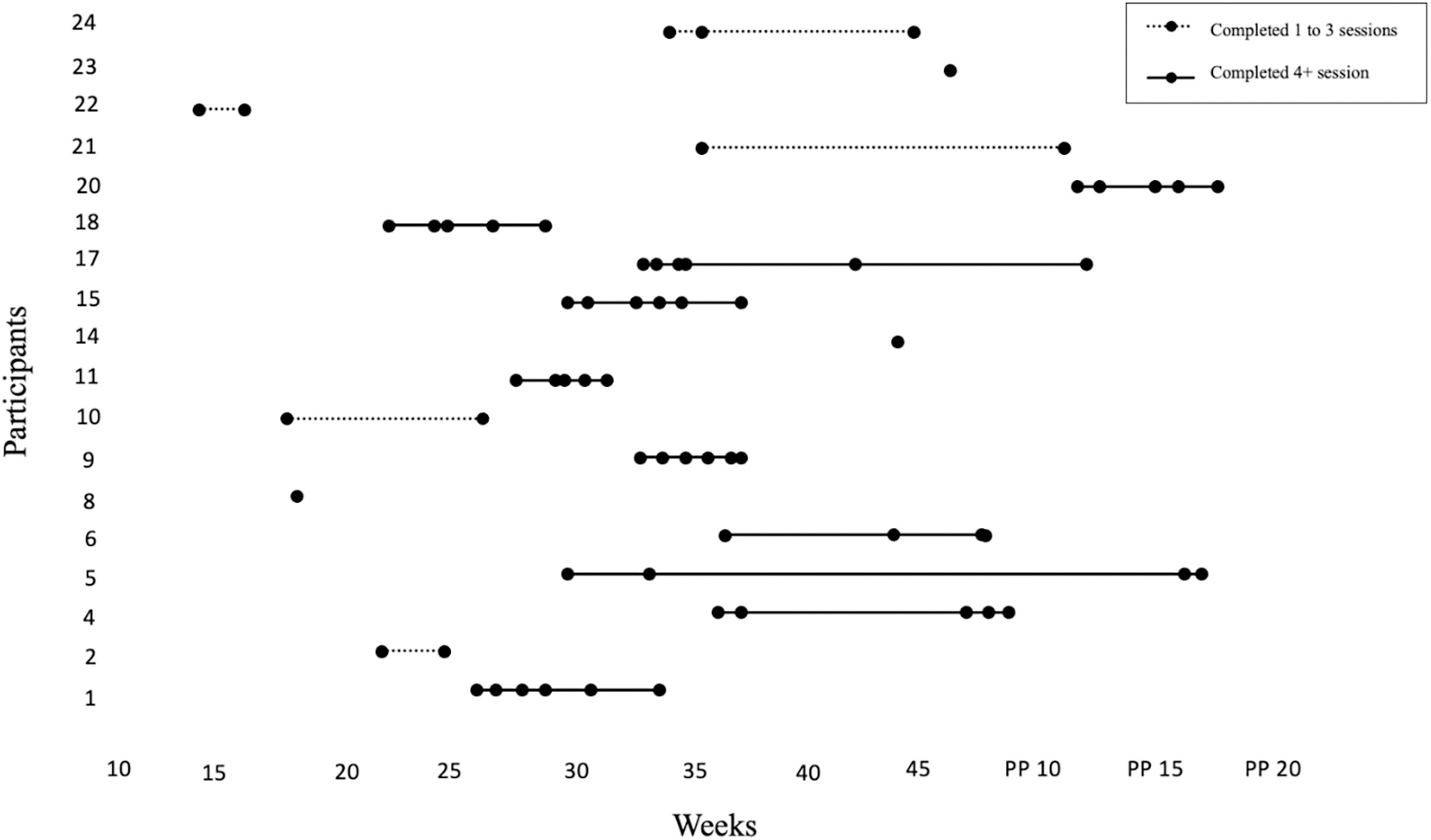

3.2. Feasibility

Of those approached, 72% expressed interest in the treatment. A total of 10 (55.6%) women who initiated WET completed at least four sessions (Fig. 1). Fig. 2 displays the timeline of WET sessions by gestational or postpartum week. Participants had their first WET session between 17.0 and 35.6 weeks of gestational age with two women not starting until postpartum (i.e., 3.5 weeks and 10 weeks postpartum). Most participants initiated the treatment in the third trimester, and three had their treatment course interrupted by the delivery of their baby and had to complete WET in the early postpartum period. Among the completers, it took an average of 8.26 (SD = 3.40) weeks to complete the five-session intervention (range in weeks 4–15). Four participants required an additional treatment session due to avoidance during the writing (writing refusal) or changing the trauma event that was the focus of the treatment. Overall, therapists demonstrated high fidelity, as measured by adherence (95.9%) to the study protocol and competence (M = 6.7 out of 7.0 maximum).

Fig. 2.

Timeline of WET Sessions Throughout Perinatal Period.

Timeline illustrating when each WET session took place by gestational age or weeks postpartum for each participant. The vertical axis represents participant number, and the horizontal axis represents weeks (either gestational age or postpartum).

3.3. Acceptability

Participant satisfaction at post-intervention was high as indicated by an average score on the CSQ-8 of 30.3 (SD = 2.4) out of a maximum possible score of 32. Qualitative analyses affirmed that WET was an acceptable treatment. Participants described how WET led to increased insight into their PTSD symptoms and connection with their SUD.

“[Before WET], I would have a lot of feelings and not know why I was having them, and now they make sense, and especially if I start talking about an experience – a traumatic experience – knowing that I may have other feelings come up – like being extra vigilant or being super scared or being depressed and stuff like that. So, it did impact the way I see life, the way I view life, the way certain things may affect me and stuff like that.”

“A lot of people have a trauma and they don’t want to think about that trauma so they just kind of block it and cover it up with drug use or something else. For me I self-medicated so I would forget, and it’s not something you can forget. It sticks with you for the rest of your life.”

Participants also described the initial increase of distress when confronting the trauma memory as the most challenging component yet emphasized the importance of persevering for their recovery.

“I would tell them that in the beginning it’s a little rough because you’re gonna do something, if you don’t like journaling, you’re gonna do something that you really don’t like. But I guarantee you, by the time you’re done doing it, you’re gonna be like ‘damn, I’m glad I did that’ or ‘damn, I feel good today, I feel so good after doing that’ or ‘damn, that was the best half hour of my day!’ That’s how I always see it.”

“The first session was really intense and it brought back a lot of feelings, but the fact that [therapist name] told me that that was normal and it was part of the therapy, you know, like letting those feelings go and learning that those feelings will come and not only during the therapy, that they can come at any time around the anniversary or a smell or scent or stuff like that. It changed me for the better though because I got over that. I got past that.”

“I would tell them to do it, but understand that it gets harder before it gets easier and to not really give up because once you start you really have to finish.”

Participants described how WET helped them shift cognitions such as self-blame.

“I have a really hard time with believing that it was my fault and blaming myself, thinking I could have stopped it, but now learning that it happened and there’s nothing I can do about it now and that I have the strength to get through it.”

Participants also described the benefits of completing WET within the integrated addiction-obstetrics program.

“I think it was good [completing WET in the obstetrics-addiction clinic] because I have other supports through [the obstetrics-addiction clinic] so they were able to connect with one another and touch base, so I didn’t have to consistently repeat what I was going through or how I was feeling. I feel like I was constantly experiencing trauma. I think they did a good job at just really connecting with one another.”

Notably, participants also found telemedicine acceptable. One participant described how telemedicine made it “easier for me to open up about certain things because I felt safe because I was home in my safe area.” However, remote delivery of WET also introduced unique challenges, including difficulty responding to in-session avoidance and obtaining writings.

3.4. Treatment outcome

See Table 2 for a summary of Wilcoxon’s Signed-Rank analyses examining change from pre- to post-intervention and pre-intervention to 6-months postpartum in PTSD symptoms, depression symptoms, and craving. PTSD symptom severity significantly decreased from pre-intervention (Mdn = 50) to post-intervention (Mdn = 16.5; S = 26.6, p = 0.006) and from pre-intervention to 6-months postpartum (Mdn = 21; S = 10.5, p = 0.031) with 73% of women no longer meeting probable diagnosis for PTSD (i.e., PCL-5 score ≥ 33) at post-intervention and 78% of women not meeting probable PTSD diagnosis at 6-months postpartum. The majority of women (70%) experienced a clinically significant reduction in PTSD symptoms [45] from pre- to post-intervention. In terms of depression symptom outcome, there was a significant decrease on the EPDS from pre-intervention (Mdn = 13) to 6-months postpartum (Mdn = 8.5; S = 14, p = 0.016). In addition, the PHQ-9 scores at post-intervention (Mdn = 7) were significantly lower than at pre-intervention (Mdn = 12; S = 17, p = 0.016). However, PHQ-9 scores at 6-months postpartum (Mdn = 8) were not significantly different from pre-intervention (S = 7, p = 0.19). Craving decreased at a trend level from pre-intervention (Mdn = 3) to post-intervention (Mdn = 1) and 6-months postpartum (Mdn = 0; S = 14.5, p = 0.052). Of note, post-intervention PCL-5 scores were not significantly different between participants who completed WET continuously (M = 26.83, SD = 13.93) versus those whose treatment course was disrupted by labor and delivery (M = 24.25, SD = 19.92; t(8) = −0.243, p = 0.81).

Table 2.

Summary of Wilcoxon’s Signed-Rank analyses examining change from pre-intervention to post-intervention and pre-intervention to follow-up in PTSD symptoms, depressive symptoms, and craving.

| Pre-Intervention (n = 10) | Post-Intervention (n = 10) | 6-Month PP Follow-up (n = 9) | Pre vs. Post | Pre vs. Follow-up | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| M (SD) | Median | M (SD) | Median | M (SD) | Median | S | p-value | Median Diff | S | p-value | Median Diff | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PCL-5 | 47.1 (18.9) | 50 | 25.8 (15.5) | 16.5 | 27.6 (8.9) | 21 | 26.6 | 0.0059 | 17.5 | 10.5 | 0.0313 | 20 |

| PHQ-9 | 12.4 (4.1) | 12 | 6.4 (3.1) | 7 | 8.4 (5.1) | 8 | 17 | 0.0156 | 6 | 7 | 0.1875 | 2.5 |

| EPDS | 15.4 (4.6) | 13 | 10.7 (3.7) | 11 | 9.9 (5.3) | 8.5 | 15.5 | 0.0703 | 3 | 14 | 0.0156 | 6 |

| Craving | 3.6 (3) | 3 | 1.9 (2.5) | 1 | 1.9 (2.4) | 0 | 14.5 | 0.052 | 1 | 14.5 | 0.052 | 1.5 |

PP = Postpartum; PCL-5 = PTSD Symptom Checklist for DSM-5; EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire.

4. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate WET’s feasibility, acceptability, and promise as an effective treatment of perinatal PTSD among pregnant women with comorbid PTSD/SUD in a usual care setting. Our findings also confirm the critical need to provide PTSD treatment in this population, given that half of women in this OB-addictions clinic screened positive for probable PTSD. Low access to PTSD treatment is a major concern, evidenced by the fact that all our participants reported they had never been offered or received any PTSD-specific treatment, despite high contact with SUD programs. Completers were highly satisfied with WET and experienced a significant reduction of PTSD symptoms from pre- to post-intervention that was sustained at 6-months postpartum. They also experienced a reduction in depressive symptoms and craving. Further, providers who were new to manualized treatments, delivered WET with excellent fidelity.

This study also highlighted successes and challenges related to recruitment and retention among pregnant women with PTSD/SUD. Successes included the ability to implement a clinic-wide screening for PTSD and utilize embedded clinical social workers. We observed a low retention rate, with only 56% completers. However, this is consistent with previous trials of first-line PTSD treatments [19] and in routine clinical care settings [46] and, importantly, higher than what is seen in a PTSD exposure-based treatment trial with a PTSD/SUD population [47]. Since women who dropped out of WET were also lost to follow-up for all study assessments, reasons for dropout are unknown. Post-hoc examination of demographic differences between completers and non-completers revealed that completers were more likely to have an obstetrical medical condition during the current pregnancy (e.g., preeclampsia) and report higher cravings at baseline. It is possible that these risk factors increased contact with the healthcare system and the treatment team, which may have assisted with retention in WET.

The timeline of WET delivery also revealed unique challenges related to the treatment delivery window in this population. Because many women in this clinic entered prenatal care later in pregnancy and were more likely to deliver early, the window to deliver this brief 5-session treatment was shorter than anticipated. Despite the variability in WET delivery with regard to length to completion or timing of treatment during the perinatal period, all women experienced a significant reduction in symptoms. Furthermore, the mean PTSD symptoms at post-intervention was similar between women who completed WET continuously as compared to women who took longer to complete WET due to the delivery of their baby during the middle of treatment. Given that that treatment disruption by labor and delivery did not impact outcomes in this study, it is possible that delivery in the early postpartum period could also be appropriate. It is difficult to ascertain if this issue of optimal timing of WET in the perinatal period is unique to this subpopulation of women with comorbid SUD, or if this issue may persist in a general OB population. Future research that investigates WET among a broad range of pregnant women is needed. Additionally, further research that aims to understand patient preferences in treatment delivery (e.g., massed vs. during pregnancy vs. during postpartum; provider type, setting, etc.) may enhance engagement and retention.

Our observed decrease in cravings after intervention is consistent with research which finds that reductions in PTSD symptoms during treatment lead to improvements in SUD symptoms [48]. Historically, misperceptions that distress related to exposure-based PTSD treatments will increase the risk for substance use have led to low adoption among usual care providers [49,50]. Similarly, there is a misperception that exposure-based PTSD treatments may lead to adverse perinatal outcomes [51]. It is also notable that adverse perinatal outcomes such as preterm birth in our study sample were equivalent among women who completed or dropped out of WET and cravings actually decreased pre-post intervention, thus refuting the notion that exposure-based treatments for PTSD are harmful to pregnant women with SUD histories.

This study provides the first examination of WET for the treatment of PTSD among pregnant women with comorbid PTSD/SUD. Although results are promising and strengthened by the 6-month postpartum follow-up assessment, this study is limited by the small sample size and lack of control condition. It also focused on a specifically at-risk subpopulation of women who experienced more medical, mental health, and social needs than what is typically seen in the general OB clinic, and are majority White compared to the racially diverse broader patient population, which may limit generalizability. Given our results, it would be likely that WET would be successful with other less severe clinical presentations although additional research is needed, particularly among diverse pregnant populations. Further, due to the need to respond to urgent staffing changes during the COVID-19 pandemic, two of the study authors needed be interventionists for a few cases, which may have introduced potential bias. Another limitation is the reliance on self-report measures to examine treatment outcome. Given the involvement of the Department of Child and Family Services in this sample of women, there may have been increased social desirability in responding to self-report measures, particularly craving, given the potential custody consequences.

5. Conclusion

In sum, this study demonstrated that delivery of WET in an OB setting among pregnant women with comorbid PTSD/SUD is feasible and acceptable. Furthermore, decreases in PTSD, depressive symptoms, and craving supports the safety of this intervention for pregnant women with PTSD/SUD. Given the promising findings of this preliminary study, additional investigation of the effectiveness of WET among pregnant women with PTSD should be pursued.

Acknowledgments and declaration of interest statement

Denise Sloan receives royalties for the published treatment manual for Written Exposure Therapy. There are no other conflicts of interest to disclose. This study was funded by an internal pilot grant by the Grayken Center for Addiction awarded to Drs. Nillni and Valentine (PIs).

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yael I. Nillni: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Tithi D. Baul: Data curation, Formal analysis, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Emilie Paul: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Laura B. Godfrey: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Denise M. Sloan: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Sarah E. Valentine: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- [1].Seng JS, Low LK, Sperlich M, Ronis DL, Liberzon I. Prevalence, trauma history, and risk for posttraumatic stress disorder among nulliparous women in maternity care. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114(4):839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Powers A, Woods-Jaeger B, Stevens JS, Bradley B, Patel MB, Joyner A, et al. Trauma, psychiatric disorders, and treatment history among pregnant African American women. Psychol Trauma 2020;12(2):138–46. 10.1037/tra0000507 [Epub 2019 Aug 29]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Muzik M, McGinnis EW, Bocknek E, Morelen D, Rosenblum KL, Liberzon I, et al. PTSD symptoms across pregnancy and early postpartum among women with lifetime ptsd diagnosis. Depress Anxiety 2016;33(7):584–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Seng JS, Low LK, Sperlich M, Ronis DL, Liberzon I. Post-traumatic stress disorder, child abuse history, birthweight and gestational age: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2011;118(11):1329–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Yonkers KA, Smith MV, Forray A, Epperson CN, Costello D, Lin H, et al. Pregnant women with posttraumatic stress disorder and risk of preterm birth. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71(8):897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Saigal S, Doyle LW. An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet Lond Engl 2008;371(9608):261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Grace SL, Evindar A, Stewart DE. The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: a review and critical analysis of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health 2003;6(4):263–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Nillni YI, Mehralizade A, Mayer L, Milanovic S. Treatment of depression, anxiety, and trauma-related disorders during the perinatal period: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2018;66:136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kotelchuck M, Cheng ER, Belanoff C, Cabral HJ, Babakhanlou-Chase H, Derrington TM, et al. The prevalence and impact of substance use disorder and treatment on maternal obstetric experiences and birth outcomes among singleton deliveries in Massachusetts. Matern Child Health J 2017;21(4):893–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Maeda A, Bateman BT, Clancy CR, Creanga AA, Leffert LR. Opioid abuse and dependence during pregnancy: temporal trends and obstetrical outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2014;121(6):1158–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Thompson MP, Kingree JB. The frequency and impact of violent traumaAmong pregnant substance abusers. Addict Behav 1998;23(2):257–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Moylan PL, Jones HE, Haug NA, Kissin WB, Svikis DS. Clinical and psychosocial characteristics of substance-dependent pregnant women with and without PTSD. Addict Behav 2001;26(3):469–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Forray A, Merry B, Lin H, Ruger JP, Yonkers KA. Perinatal substance use: a prospective evaluation of abstinence and relapse. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;1 (150):147–55. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.02.027 [Epub 2015 Mar 3]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Terplan M, Hood M, Bernson D, Diop H, et al. Fatal and nonfatal overdose among pregnant and postpartum women in Massachusetts. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132(2):466–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Frazer Z, McConnell K, Jansson LM. Treatment for substance use disorders in pregnant women: motivators and barriers. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;1(205):107652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Shenai N, Gopalan P, Glance J. Integrated brief intervention for PTSD and substance use in an antepartum unit. Matern Child Health J 2019;23(5):592–6. 10.1007/s10995-018-2686-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Sloan DM, Marx BP. Written exposure therapy for PTSD: A brief treatment approach for mental health professionals. Available from: https://www.apa.org/pubs/books/4317524; 2019.

- [18].Sloan DM, Marx BP, Bovin MJ, Feinstein BA, Gallagher MW. Written exposure as an intervention for PTSD: a randomized clinical trial with motor vehicle accident survivors. Behav Res Ther 2012;50(10):627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sloan DM, Marx BP, Lee DJ, Resick PA. A brief exposure-based treatment vs cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2018;75(3):233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Sloan DM, Marx BP, Resick PA, Young-Mccaughan S, Dondanville KA, Straud CL, et al. Effect of written exposure therapy vs cognitive processing therapy on increasing treatment efficiency among military service members with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized noninferiority trial. JAMA Netw Open 2022;5(1):e2140911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].LoSavio ST, Worley CB, Aajmain ST, Rosen CS, Stirman SW, Sloan DM. Effectiveness of written exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy [Internet] 2021. [cited 2022 Sep 13]; Available from: /record/2021-98451-001]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 2012;50(3):217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Prins A, Bovin MJ, Smolenski DJ, Marx BP, Kimerling R, Jenkins-Guarnieri MA, et al. The primary care PTSD screen for DSM-5 (PC-PTSD-5): development and evaluation within a veteran primary care sample. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31(10):1206–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Weathers F, Blake D, Schnurr P, Kaloupek D, Marx BP, Keane T. The life events checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Available from: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/te-measures/life_events_checklist.asp; 2013.

- [25].Weathers F, Litz BT, Keane T, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. PTSD checklist for the DSM-5. Available from: https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp; 2013.

- [26].Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, et al. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess 2016;28(11):1379–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Pietrzak RH, Goldstein RB, Southwick SM, Grant BF. Prevalence and Axis I comorbidity of full and partial posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from Wave 2 of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Anxiety Disord 2011;25(3):456–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defense. VA/DOD Clinical Practice Guideline For The Management Of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder And Acute Stress Disorder. Available from, https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal.pdf; 2017.

- [29].Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med 1998;14(4):245–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, Domino JL. The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): development and initial psychometric evaluation. J Trauma Stress 2015;28(6):489–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Lee DJ, Weathers FW, Thompson-Hollands J, Sloan DM, Marx BP. Concordance in PTSD symptom change between DSM-5 versions of the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5) and PTSD Checklist (PCL-5). Psychol Assess 2022;34(6):604–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci 1987;150:782–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9):606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Matthey S, Henshaw C, Elliott S, Barnett B. Variability in use of cut-off scores and formats on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: implications for clinical and research practice. Arch Womens Ment Health 2006;9(6):309–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Mazurick C, Berkman B, Gastfriend DR, Frank A, et al. The relationship between cocaine craving, psychosocial treatment, and subsequent cocaine use. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(7):1320–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Hufford C. Craving in hospitalized cocaine abusers as a predictor of outcome. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1995;21:289–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Hufford C, Muenz LR, Najavits LM, Jansson SB, et al. Early prediction of initiation of abstinence from cocaine: use of a craving questionnaire. Am J Addict 1997;6:224–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].McHugh RK, Fitzmaurice GM, Carroll KM, Griffin ML, Hill KP, Wasan AD, et al. Assessing craving and its relationship to subsequent prescription opioid use among treatment-seeking prescription opioid dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;1(145):121–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].McHugh RK, Fitzmaurice GM, Griffin ML, Anton RF, Weiss RD. Association between a brief alcohol craving measure and drinking in the following week. Addict Abingdon Engl 2016;111(6):1004–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann 1982;5(3):233–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Larsen DL, Attkisson CC, Hargreaves WA, Nguyen TD. Assessment of client/patient satisfaction: development of a general scale. Eval Program Plann 1979;2(3):197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].SAS Institute Inc. SAS 9.4 Users Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15(9):1277–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Marx BP, Lee DJ, Norman SB, Bovin MJ, Sloan DM, Weathers FW, et al. Reliable and clinically significant change in the clinician-administered PTSD scale for DSM-5 and PTSD checklist for DSM-5 among male veterans. Psychol Assess 2022;34(2):197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Kehle-Forbes SM, Meis LA, Spoont MR, Polusny MA. Treatment initiation and dropout from prolonged exposure and cognitive processing therapy in a VA outpatient clinic. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy 2016;8(1):107–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Belleau EL, Chin EG, Wanklyn SG, Zambrano-Vazquez L, Schumacher JA, Coffey SF. Pre-treatment predictors of dropout from prolonged exposure therapy in patients with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid substance use disorders. Behav Res Ther 2017;91:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Hien DA, Jiang H, Campbell ANC, Hu MC, Miele GM, Cohen LR, et al. Do treatment improvements in PTSD severity affect substance use outcomes? A secondary analysis from a randomized clinical trial in NIDA’s Clinical Trials Network. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167(1):95–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Back SE, Waldrop AE, Brady KT. Treatment challenges associated with comorbid substance use and posttraumatic stress disorder: Clinicians’ perspectives. Am J Addict 2009;18:15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Becker CB, Zayfert C, Anderson E. A survey of psychologists’ attitudes towards and utilization of exposure therapy for PTSD. Behav Res Ther 2004;42(3):277–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Hendrix YMGA, Sier MAT, Baas MAM, van Pampus MG. Therapist perceptions of treating posttraumatic stress disorder in pregnancy: the VIP study. J Trauma Stress 2022;35(5):1420–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.