Abstract

Background and Aims

To evaluate the effect of mirikizumab, a p19-targeted anti-interleukin-23, on histological and/or endoscopic outcomes in moderately-to-severely active ulcerative colitis [UC].

Methods

Endoscopic remission [ER], histological improvement [HI], histological remission [HR], histological-endoscopic mucosal improvement [HEMI], and histological-endoscopic mucosal remission [HEMR] were assessed at Week [W]12 [LUCENT-1: N = 1162, induction] and W40 [LUCENT-2: N = 544, maintenance] for patients randomised to mirikizumab or placebo. Analyses were performed to evaluate predictors of: HEMI at W12 with mirikizumab and HEMR at W40 in patients re-randomised to subcutaneous [SC] mirikizumab; associations between W12 histological/endoscopic endpoints and W40 outcomes in mirikizumab responders re-randomised to mirikizumab SC; and associations between W40 endoscopic normalisation [EN] with/without HR.

Results

Significantly more patients treated with mirikizumab achieved HI, HR, ER, HEMI, and HEMR vs placebo [p <0.001], irrespective of prior biologic/tofacitinib failure [p <0.05]. Lower clinical baseline disease activity, female sex, no baseline immunomodulator use, and no prior biologic/tofacitinib failure were predictors of HEMI at W12 [p <0.05]. Corticosteroid use and longer disease duration were negative predictors of achieving HEMR at W40 [p <0.05]. W12 HI, HR, or ER was associated with W40 HEMI or HEMR [p <0.05]; ER at W12 was associated with clinical remission [CR] [p <0.05] and corticosteroid-free remission [CSFR] at W40 [p = 0.052]. HR and HEMR at W12 were associated with CSFR, CR, and symptomatic remission at W40. Alternate HEMR [EN + HR] at W40 was associated with bowel urgency remission at W40 [p <0.05].

Conclusions

Early resolution of endoscopic and histological inflammation with mirikizumab is associated with better UC outcomes. Clinicaltrials.gov: LUCENT-1, NCT03518086; LUCENT-2, NCT03524092.

Keywords: Histological remission, mirikizumab, ulcerative colitis

1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis [UC] is a chronic disease with a relapsing-remitting course, characterised by inflammation of the colon and rectum.1 Goals in the management of UC include induction and maintenance of remission and reduction in steroid use2; however, advances in therapeutics for management of UC have altered treatment targets.3–5 Current consensus guidelines for clinical practice and trial endpoints recommend striving beyond resolution of clinical symptoms, namely achieving endoscopic and histological improvement and/or histological remission.6 The validity of this recommendation is derived from observational data showing that patients who achieved endoscopic remission, defined as a Mayo endoscopic subscore [ES] of 0 or 1, had lower rates of clinical relapse, corticosteroid use, and colectomy compared with patients who did not achieve this outcome.7,8 However, endoscopic remission alone may not be enough to predict treatment outcomes, and histological assessment of the colonic mucosa may provide a more accurate assessment of the disease. Histological remission has been correlated with reductions in corticosteroid use, surgery, or disease progression,9,10 and more recently, a combination of histological and endoscopic endpoints was associated with clinical remission and corticosteroid-free remission.11,12

Current treatments for UC are limited by an incomplete or non-response over time.13,14 Therefore, there remains an unmet need for treatments with novel mechanisms of action. Mirikizumab is a humanised immunoglobulin G4 variant monoclonal antibody that is directed against the p19 subunit of interleukin [IL]-23,15 a key mediator in the pathogenesis of UC.16 In two phase 3 clinical trials [LUCENT-1 induction and LUCENT-2 maintenance], clinical remission was achieved in mirikizumab-treated patients at 12 weeks and was maintained through 40 weeks of maintenance treatment [ie, 52 weeks of continuous treatment with mirikizumab].17 Here we evaluated the efficacy of mirikizumab on histological and combined histological-endoscopic endpoints from LUCENT-1 and LUCENT-2 in patients with moderately-to-severely active UC who received mirikizumab treatment through Week 52. The baseline predictors for histological-endoscopic mucosal improvement [HEMI] and histological-endoscopic mucosal remission [HEMR], and the predictive value of histological and/or endoscopic endpoints in relation to maintenance outcomes, were assessed.

2. Materials And Methods

2.1. Study design

The full study designs and treatment protocols of LUCENT-1 and LUCENT-2 have been previously described.17 LUCENT-1 was a phase 3, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-arm, placebo-controlled trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of mirikizumab over a 12-week induction period in patients with moderately-to-severely active UC. The study was conducted from June 2018 to January 2021. LUCENT-2 was a phase 3, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-arm, placebo-controlled trial that evaluated the safety and efficacy of mirikizumab over a 40-week maintenance period in patients who completed LUCENT-1. The study was conducted from October 2018 to November 2021.

Both studies were conducted in compliance with the consensus ethics principles derived from international ethics guidelines, including the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation, and applicable laws and regulations. All patients provided written informed consent before participating in the study. Both studies were registered at clinicaltrials.gov [LUCENT-1, NCT03518086; LUCENT-2, NCT03524092].

2.2. Study population

The full eligibility criteria for LUCENT-1 and LUCENT-2 have been previously described.17 For LUCENT-1, eligible patients were between 18 and 80 years of age and had had a diagnosis of UC for at least 3 months. All patients had to have endoscopic evidence of UC, a histopathology report that supported a diagnosis of UC, UC beyond the rectum, and a modified Mayo score [MMS] of 4 to 9 with an ES ≥2 within 14 days of study start. A specified histopathological score was not required for inclusion and UC evidence was based on endoscopy alone. To enter LUCENT-1, patients were required to have had an inadequate response, loss of response, or intolerance to ≥1 corticosteroid or immunomodulator therapies for UC [non-biologic or tofacitinib failed], or inadequate response, loss of response, or intolerance to biologic therapy or to Janus kinase inhibitors for UC [biologic or tofacitinib failed].

To enter LUCENT-2, eligible patients must have completed LUCENT-1 and had all necessary evaluations to assess MMS at the end of LUCENT-1. Stable doses of oral 5-aminosalicylic acid therapy, azathioprine, mercaptopurine, and methotrexate were permitted during both studies. In LUCENT-1, stable doses of corticosteroids [≤20 mg of prednisone] were permitted, whereas corticosteroid tapering was required in LUCENT-2.

2.3. Treatment protocol

The full treatment protocols for LUCENT-1 and LUCENT-2 have been previously described.17 Briefly, at Week 0 of LUCENT-1, patients were randomised in a 3:1 ratio to 300 mg mirikizumab intravenously [IV] every 4 weeks [Q4W] or placebo IV Q4W. Patients who achieved a clinical response with mirikizumab at Week 12 in LUCENT-1, defined as a decrease in MMS of ≥2 points and ≥30% decrease from baseline, and a decrease of ≥1 point in the rectal bleeding [RB] subscore from baseline, or an RB subscore of 0 or 1, and who chose to enter the LUCENT-2 maintenance trial, were re-randomised 2:1 to 200 mg mirikizumab subcutaneously [SC] Q4W or withdrawal to placebo SC Q4W for 40 weeks [total of 52 weeks of continuous therapy]. Patients who experienced secondary loss of response to 200 mg mirikizumab SC Q4W or to placebo SC Q4W at or after Week 12 of LUCENT-2, received rescue therapy with open-label 300 mg mirikizumab IV Q4W for three doses. Patients who completed Week 40 of LUCENT-2 or received rescue therapy due to loss of response entered the long-term extension study LUCENT-3.

2.4. Outcome measures

2.4.1. Clinical outcomes

The primary endpoints and major secondary endpoints for LUCENT-1 and LUCENT-2 have been previously reported.17 For LUCENT-1, the primary endpoint was the proportion of patients in clinical remission at Week 12 based on the MMS, defined as an MMS stool frequency [SF] subscore of 0, an SF subscore of 1 with a ≥1-point decrease from baseline, an RB subscore of 0, and an ES of 0 or 1 [excluding friability]. For LUCENT-2, the primary endpoint was the proportion of patients in clinical remission at Week 40.

Corticosteroid-free remission was defined as: clinical remission at Week 40; symptomatic remission at Week 28; and no corticosteroid use for ≥12 weeks prior to Week 40. The patient-reported Urgency Numeric Rating Scale [NRS], an 11-point scale, was used to assess improvement in the severity of patients’ bowel movement urgency. Bowel urgency remission, or no-to-minimal bowel urgency, was defined as achieving an Urgency NRS score of 0 or 1. The Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire [IBDQ] is a 32-item patient-completed questionnaire that measures four domains of patients’ lives: bowel symptoms, systemic symptoms, emotional function, and social function. Responses are graded on a 7-point Likert scale, in which 7 denotes ‘not a problem at all’ and 1 denotes ‘a very severe problem’, and a total score ≥170 constitutes IBDQ remission.

2.4.2. Histological-endoscopic endpoints

The endpoints of interest in this manuscript are the proportions of patients with histological improvement, histological improvement only [without endoscopic remission], histological remission, histological remission only [without endoscopic normalisation], endoscopic remission, endoscopic remission only [without histological improvement], endoscopic normalisation, endoscopic normalisation only [without histological remission], HEMI [histological improvement and endoscopic remission], HEMR [histological remission and endoscopic remission], and alternate HEMR [histological remission and endoscopic normalisation] at Week 12 of LUCENT-1 and Week 40 of LUCENT-2. Full definitions of these outcomes are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Histological and endoscopic endpoints assessed at Week 12 of LUCENT-1 and/or Week 40 of LUCENT-2

| Endpoint | Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Histological improvement | HI | Geboes score ≤3.1: neutrophil infiltration in <5% of crypts; no crypt destruction; and no erosions, ulcerations, or granulation tissue |

| Histological remission | HR | Geboes score ≤2B.0: no lamina propria neutrophils; no neutrophils in the surface or crypt epithelium; no crypt destruction; and no erosions, ulcerations, or granulation tissue |

| Endoscopic remission | ER | Mayo ES = 0 or 1 [excluding friability] |

| Endoscopic normalisation | EN | Mayo ES = 0 |

| Histological improvement onlya | HI only | HI without ER |

| Histological remission onlya | HR only | HR without EN |

| Endoscopic remission onlya | ER only | ER without HI |

| Endoscopic normalisation onlya | EN only | EN without HR |

| Histological-endoscopic mucosal improvement | HEMI | HI and ER: Geboes score ≤3.1 plus Mayo ES = 0 or 1 [excluding friability] |

| Histological-endoscopic mucosal remission | HEMR | HR and ER: Geboes score ≤2B.0 plus Mayo ES = 0 or 1 [excluding friability] |

| Alternate histological-endoscopic mucosal remission | Alternate HEMR | HR and EN: Geboes score ≤2B.0 plus Mayo ES = 0 |

HI, histological improvement; HEMI, histological-endoscopic improvement; HR, histological remission; ER, endoscopic remission; EN, endoscopic normalisation; HEMR, histological-endoscopic remisssion; ES, endoscopic subscore.

aIncludes patients who only met the endpoints described.

2.5. Endoscopic assessment

Endoscopists were instructed to assess Mayo ES from the colonic segment with the highest grade of visible mucosal inflammation. Endoscopy was used to determine the ES by both site and blinded central reading of endoscopies. The blinded central reader who assessed the screening endoscopy video in LUCENT-1 for an individual patient was assigned to read all subsequent follow-up videos for that patient. If the site-read and central-read ES matched, then that was the final modified Mayo ES for the patient at that time point; however, if there was disagreement between the site and central readers, a second independent central reader read the endoscopy video, without knowledge of the scores. If the second central reader confirmed one of the previous ES, then that was the final modified Mayo ES for the patient at the time point; however, if none of the modified Mayo ESs matched, a median of all three scores was taken as the final modified Mayo ES for the patient at that time point.

2.6. Biopsy collection and processing

Endoscopists were instructed to collect five biopsies at each sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy [three for histological assessment and two as backup] from the colonic segment with the highest grade of visible mucosal inflammation. No topical treatment was allowed. When active disease was present and if discrete mucosal lesions were present [eg, ulcers or erosions], endoscopists were instructed to obtain biopsies at the edge of the lesions; however, if discrete mucosal lesions were not present, biopsy collection was spaced throughout the affected mucosa and the most affected area was targeted. When active disease was absent, where possible, biopsies were obtained from the same location as the segment biopsied in previous endoscopy procedures. Histopathological scoring of the biopsies was performed by a blinded central reader, according to the most severe features across the three samples presented on each slide. Where possible, the central reader who assessed the histology slides from the endoscopy conducted at screening in LUCENT-1 for an individual patient, was assigned to read all subsequent follow-up biopsies for that patient.

2.7. Geboes scoring

For histological assessment, Geboes scoring, an instrument for the standardisation of histological assessment in UC,18 was used [Supplementary Table 1]. The Geboes scoring system comprises seven grades and degrees of subscores that indicate the degree of abnormality: grade 0 [evidence of structural or architectural change], grade 1 [presence of chronic inflammatory infiltrate], grade 2a [presence of lamina propria eosinophils], grade 2b [presence of lamina propria neutrophils], grade 3 [presence of neutrophils in the epithelium], grade 4 [evidence of crypt destruction], or grade 5 [evidence of surface epithelial injury].

2.8. Statistical analysis

Rates of patients achieving histological and/or endoscopic endpoints were calculated for LUCENT-1 in the modified intention-to-treat [mITT] population, which included all randomised patients who received any amount of study treatment.17 Endpoints were assessed in LUCENT-2 among mirikizumab responders at Week 12 who were re-randomised to mirikizumab or placebo in LUCENT-2. For comparison of histological and histological-endoscopic endpoints between treatment groups, the Mantel-Haenszel test of common risk difference was used adjusting for confounding factors. Patients who had missing data for histological and histological-endoscopic outcomes were classified as not having achieved the endpoint. Comparisons between mirikizumab and placebo were also conducted, for all histological and histological-endoscopic endpoints at Week 12 in LUCENT-1 and Week 40 in LUCENT-2, in subgroups of patients who had failed prior biologic (anti-tumour necrosis factor [TNF] or vedolizumab) or tofacitinib [Janus kinase inhibitor] treatment and those who had not failed prior biologic or tofacitinib treatment at baseline.

Associations between baseline prognostic factors and HEMI, at Week 12 of LUCENT-1 and HEMR at Week 40 of LUCENT-2, were evaluated: among patients randomised to mirikizumab 300 mg IV in LUCENT-1; and among mirikizumab induction responders at Week 12 in LUCENT-1 who were re-randomised to mirikizumab 200 mg SC in LUCENT-2, respectively. Univariable logistic regression models were fitted to evaluate marginal associations, and multivariable logistic regression models were fitted to identify a parsimonious subset of important baseline prognostic factors that were associated with the outcome of interest. For multivariable models, a stepwise model selection approach with an entry p-value of 0.05 and a stay p-value of 0.05 was used for variable selection. Non-responder imputation was used for missing binary outcome data.

Logistic regression was used to assess whether histological endpoints at Week 12 in LUCENT-1 could independently predict Week 40 outcomes in LUCENT-2, after adjusting for endoscopic endpoints. These analyses were conducted in mirikizumab induction responders who were re-randomised to mirikizumab 200 mg SC in LUCENT-2, and included a Week-40 outcome analysed with a Week-12 histological outcome and a Week-12 endoscopic outcome as predictors.

Associations between histological, endoscopic, and composite histological-endoscopic mucosal endpoints at Week 12 in LUCENT-1, with clinical and symptomatic outcomes at Week 40 in LUCENT-2, were evaluated among mirikizumab induction responders who were re-randomised to mirikizumab 200 mg SC in LUCENT-2, by comparing odds ratios [ORs] and associated 95% confidence intervals [CIs]. Rates for patients achieving each of the Week 40 clinical outcomes were calculated for patients who achieved HEMI, histological improvement only [without endoscopic remission], endoscopic remission only [without histological improvement], and neither histological improvement nor histological remission at Week 12. Pairwise comparisons between the Week-12 groups were made using Fisher’s exact tests.

Associations between histological, endoscopic, and composite histological-endoscopic mucosal endpoints at Week 40 in LUCENT-2, with clinical and symptomatic outcomes at Week 40 in LUCENT-2, were evaluated among mirikizumab induction responders who were re-randomised to mirikizumab 200 mg SC in LUCENT-2. Rates for patients achieving each of the Week-40 clinical outcomes were calculated for patients who achieved alternate HEMR, histological remission only [without endoscopic normalisation], endoscopic normalisation only [without histological remission], and neither histological remission nor endoscopic normalisation at Week 40. Pairwise comparisons between the Week-40 histological and endoscopic groups were made using Fisher’s exact tests.

3. Results

3.1. Patient disposition and characteristics

A detailed description of the patient disposition and baseline disease characteristics has been reported previously.17 In LUCENT-1, there were 1162 patients [294 placebo, 868 mirikizumab IV Q4W] in the mITT population, of whom 1082 patients [257 placebo, 825 mirikizumab] completed the study. In LUCENT-2, 544 patients who achieved a clinical response to mirikizumab at Week 12 in LUCENT-1 were randomised to placebo [N = 179] or 200 mg mirikizumab SC Q4W [N = 365].

Overall, patient demographics and disease characteristics were generally similar across trial groups in LUCENT-1 and LUCENT-2. In LUCENT-1, patients had a mean duration of UC of 6.9 years in the placebo group and 7.2 years in the mirikizumab group.

Severe UC, defined as an MMS of 7 to 9, was reported by 53% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, whereas an ES of 3 was reported by 68% and 66% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, respectively. More than 50% of patients were biologic or tofacitinib treatment naïve and approximately 40% of patients had failed at least one biologic or tofacitinib treatment.

In LUCENT-2, the mean duration of UC was 6.8 years for mirikizumab induction responders. Severe UC, defined as an MMS of 7 to 9, was reported by 53% of mirikizumab induction responders, whereas an ES of 3 was reported by 63% of mirikizumab induction responders. For mirikizumab induction responders, 63% of patients were biologic or tofacitinib treatment naïve and approximately 35% of patients had failed at least one biologic or tofacitinib treatment.

3.2. Histological, endoscopic, and histological-endoscopic induction and maintenance outcomes

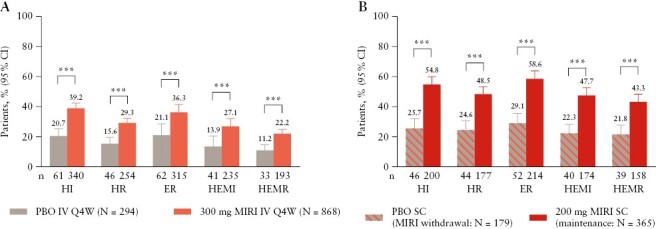

At Week 12 of LUCENT-1, significantly greater proportions of patients achieved histological improvement, histological remission, endoscopic remission, HEMI, and HEMR with mirikizumab compared with placebo [p <0.001 each] [Figure 1A]. Histological improvement was achieved by 21% and 39% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, respectively [common risk difference 18.5%; p <0.001], whereas histological remission was achieved by 16% and 29% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, respectively [common risk difference 13.7%; p <0.001]. Endoscopic remission was achieved by 21% and 36% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, respectively [common risk difference 15.4%; p <0.00001]. HEMI was achieved by 14% and 27% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, respectively [common risk difference 13.4%; p <0.00001], and HEMR was achieved by 11% and 22% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, respectively [common risk difference 11.3%; p <0.001].

Figure 1.

Proportion of patients with histological improvement [HI], histological remission [HR], endoscopic remission [ER], histological-endoscopic mucosal improvement [HEMI], and histological-endoscopic mucosal remission [HEMR] at Week 12 in LUCENT-1 induction [A] and at Week 40 in LUCENT-2 mirikizumab [MIRI] induction responders [B]. HI was defined using the Geboes scoring system: neutrophil infiltration of <5% of crypts; no crypt destruction; and no erosions, ulcerations, or granulation tissue [Geboes score ≤3.1]. HR was defined using the Geboes scoring system, with no lamina propria neutrophils; no neutrophils in the surface or crypt epithelium; no crypt destruction; and no erosions, ulcerations, or granulation tissue [Geboes score ≤2B.0]. ER was defined as endoscopic subscore = 0 or 1 [excluding friability]. HEMI was defined as achieving both HI and ER [defined above]. ***p <0.001 vs placebo [PBO]. CI, confidence interval; IV, intravenous; Q4W, every 4 weeks; SC, subcutaneous.

At Week 40 of LUCENT-2, significantly greater proportions of patients who received maintenance therapy with mirikizumab 200 mg SC achieved histological improvement, histological remission, endoscopic remission, HEMI, and HEMR, compared with placebo [Figure 1B]. Histological improvement was achieved by 26% and 55% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, respectively [common risk difference 28.0%; p <0.001], whereas histological remission was achieved by 25% and 49% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, respectively [common risk difference 22.5%; p <0.001]. Endoscopic remission was achieved by 29% and 59% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, respectively [common risk difference 28.5%; p <0.001]. HEMI was achieved by 22% and 48% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, respectively [common risk difference vs placebo 23.9%; p <0.001], and HEMR was achieved by 22% and 43% of patients in the placebo and mirikizumab groups, respectively [common risk difference 19.9%; p <0.001].

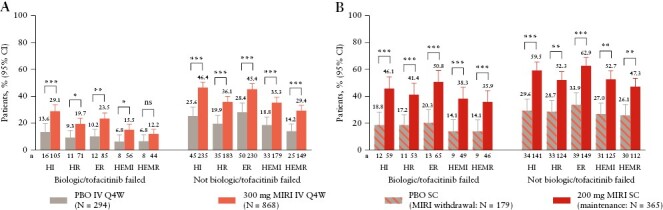

The treatment effect of mirikizumab was consistently and significantly demonstrated regardless of prior biologic or tofacitinib failure for most outcomes [Figure 2]. In LUCENT-1 at Week 12, significantly greater proportions of patients achieved histological improvement, histological remission, endoscopic remission, and HEMI with mirikizumab compared with placebo, in patients with [p <0.05] and without [p <0.001] prior biologic or tofacitinib failure at baseline [Figure 2A]. The proportion of patients who achieved HEMR at Week 12 was not statistically significant between mirikizumab and placebo in patients with prior biologic or tofacitinib failure [p = 0.113] but was significant in patients with no prior biologic or tofacitinib failure [p <0.0001]. At Week 40 of LUCENT-2, significantly greater proportions of patients achieved histological improvement, histological remission, endoscopic remission, HEMI, and HEMR with mirikizumab compared with placebo in patients with [all common risk differences ≥19.2%; p <0.01] and without [all common risk differences ≥20.8%; p <0.001] prior biologic or tofacitinib failure at baseline [Figure 2B].

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients with or without prior biologic or tofacitinib failure who achieved histological improvement [HI], histological remission [HR], endoscopic remission [ER], histological-endoscopic mucosal improvement [HEMI], and histological-endoscopic mucosal remission [HEMR] at Week 12 in LUCENT-1 induction [A] and at Week 40 in LUCENT-2 mirikizumab [MIRI] induction responders [B]. HI was defined using the Geboes scoring system: neutrophil infiltration of <5% of crypts; no crypt destruction; and no erosions, ulcerations, or granulation tissue [Geboes score ≤3.1]. HR was defined using the Geboes scoring system, with no lamina propria neutrophils; no neutrophils in the surface or crypt epithelium; no crypt destruction; and no erosions, ulcerations, or granulation tissue [Geboes score ≤2B.0]. ER was defined as endoscopic subscore = 0 or 1 [excluding friability]. HEMI was defined as achieving HI and ER [defined above]. HEMR was defined as achieving HR and ER [defined above]. *p <0.05, **p <0.01; ***p <0.001 vs placebo [PBO]. CI, confidence interval; IV, intravenous; ns, not significant; Q4W, every 4 weeks; SC, subcutaneous.

3.3. Baseline factors associated with HEMI at Week 12 and HEMR at Week 40

Associations between demographic and disease characteristics at induction baseline and HEMI at Week 12 were analysed in patients randomised to mirikizumab 300 mg IV in LUCENT-1. In LUCENT-1, age <40 years, female sex, left-sided colitis, faecal calprotectin ≤250 μg/g, C-reactive protein [CRP] ≤6 mg/L, moderate MMS, ES = 2, SF subscore <3, and no prior biologic or tofacitinib failure were significantly associated with HEMI at Week 12 in the univariable analysis [Table 2]. Of these, female sex, CRP ≤6 mg/L, ES ≤2, SF subscore <3, and no prior biologic or tofacitinib failure, as well as no baseline immunomodulator use, were significant in the multivariable model [all p <0.05] and were positively associated with achieving HEMI at Week 12.

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis of associations between patient demographics and baseline characteristics and HEMI at Week 12 of LUCENT-1 [NRI] in patients randomised to mirikizumab 300 mg IV in LUCENT-1

| Parameter | Category | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | p-value | OR [95% CI] | p-value | ||

| Age | <40 vs > 40 years | 1.44 [1.07-1.95] | 0.0169 | ||

| Sex | Female vs male | 1.60 [1.18-2.17] | 0.0024 | 1.60 [1.11-2.30] | 0.0108 |

| Ethnicitya | Hispanic/Latino vs non-Hispanic/non-Latino | 0.64 [NA-NA] | 0.2611 | ||

| Not reported vs non-Hispanic/non-Latino | 8.05 [0.41 to > 999] | ||||

| Race | American Indian/Alaska Native vs White | 0.83 [NA-NA] | 0.8652 | ||

| Asian vs White | 1.25 [NA-NA] | ||||

| Black vs White | 0.83 [NA-NA] | ||||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander vs White | 0.90 [NA-NA] | ||||

| Multiple vs White | 0.90 [NA-NA] | ||||

| Geographical region | Europe vs North America | 1.10 [0.70-1.76] | 0.4164 | ||

| Other vs North America | 1.29 [0.84-2.04] | ||||

| Weight | <100 vs ≥ 100 kg | 0.89 [0.51-1.59] | 0.6805 | ||

| BMI | Underweight [<18.5 kg/m2] vs normal [≥18.5 and < 25 kg/m2] | 1.02 [0.54-1.84] | 0.2863 | ||

| Overweight [≥25 and < 30 kg/m2] vs normal [≥18.5 and 25 kg/m2] | 0.71 [0.49-1.02] | ||||

| Obese [≥30 and < 40 kg/m2] vs normal [≥18.5 and < 25 kg/m2] | 0.88 [0.55-1.38] | ||||

| Extreme obese [≥40 kg/m2] vs normal [≥18.5 and < 25 kg/m2] | 1.79 [0.55-5.45] | ||||

| Tobacco use | Current vs never | 1.02 [0.50-1.97] | 0.6381 | ||

| Former vs never | 0.85 [0.60-1.19] | ||||

| Baseline corticosteroid use | No vs yes | 1.34 [0.99-1.83] | 0.0613 | ||

| Baseline immunomodulator use | No vs yes | 1.39 [0.97-2.02] | 0.0715 | 1.67 [1.08-2.57] | 0.0199 |

| Duration of UC | <3 vs ≥ 7 years | 1.23 [0.87-1.75] | 0.4986 | ||

| ≥3 to < 7 vs ≥ 7 years | 1.09 [0.74-1.58] | ||||

| Baseline disease locationb | Left-sided colitis vs pancolitis | 1.40 [1.02-1.93] | 0.0377 | ||

| Baseline faecal calprotectin | ≤250 vs > 250 μg/g | 2.46 [1.49-4.04] | 0.0005 | ||

| Baseline CRP | ≤6 vs 6 mg/L | 2.35 [1.69-3.31] | <0.0001 | 1.95 [1.31-2.91] | 0.0011 |

| Baseline MMS | Moderate [4–6] vs severe [7–9] | 2.05 [1.51-2.78] | <0.0001 | ||

| Baseline ES | 2 vs 3 | 3.11 [2.28-4.25] | <0.0001 | 2.04 [1.41-2.94] | 0.0002 |

| Baseline SF subscore | <3 vs 3 | 2.37 [1.75-3.23] | <0.0001 | 2.28 [1.59-3.28] | <0.0001 |

| Baseline RB subscore | <2 vs ≥ 2 | 0.95 [0.70-1.28] | 0.7250 | ||

| Prior biologic or tofacitinib failure | Not failed vs failed | 2.95 [2.12-4.17] | <0.0001 | 2.63 [1.77-3.91] | <0.0001 |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; ES, endoscopic score; HEMI, histological-endoscopic mucosal improvement; IV, intravenous; MMS, modified Mayo score; NA, not applicable; NRI, non-responder imputation; OR, odds ratio; RB, rectal bleeding; SF, stool frequency; UC, ulcerative colitis.

aOnly includes responses from US sites.

bEight patients with proctitis were combined with left-sided colitis when examining disease location.

Associations between demographic and disease characteristics at induction baseline and HEMR at Week 40 were analysed among mirikizumab induction responders re-randomised to mirikizumab. The analysis showed that weight <100 kg, left-sided colitis, between 3 and 7 years of UC duration, and no prior biologic or tofacitinib failure were significantly associated with HEMR at Week 40 in the univariable analysis [Table 3]. No baseline corticosteroid use was significantly associated with HEMR at Week 40 of LUCENT-2 in the multivariable analysis. In addition, shorter durations of UC, both <3 years [OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.10-3.34] and ≥ 3 to < 7 years [OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.28-4.23], were positively associated with HEMR at Week 40 compared with patients with longer disease duration [≥7 years].

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis of associations between patient demographics and baseline characteristics and HEMR at Week 40 of LUCENT-2 [NRI] in patients who achieved clinical response to mirikizumab at Week 12 in LUCENT-1 and were re-randomised to mirikizumab 200 mg SC in LUCENT-2

| Parameter | Category | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | p-value | OR [95% CI] | p-value | ||

| Age | <40 vs > 40 years | 1.35 [0.89-2.05] | 0.1598 | ||

| Sex | Female vs male | 1.18 [0.78-1.80] | 0.4356 | ||

| Ethnicitya | Hispanic/Latino vs non-Hispanic/non-Latino | 0.39 [0.09-1.49] | 0.1726 | ||

| Race | American Indian/Alaska Native vs White | 0.76 [0.07-5.80] | 0.9502 | ||

| Asian vs White | 0.92 [0.57-1.48] | ||||

| Black vs White | 0.70 [0.12-3.24] | ||||

| Geographical region | Europe vs North America | 1.07 [0.56-2.07] | 0.7245 | ||

| Other vs North America | 0.89 [0.48-1.68] | ||||

| Weight | <100 vs ≥ 100 kg | 2.43 [1.02-6.54] | 0.0442 | ||

| BMI | Underweight [<18.5 kg/m2] vs normal [≥18.5 and < 25 kg/m2] | 0.67 [0.28-1.51] | 0.8551 | ||

| Overweight [≥25 and < 30 kg/m2] vs normal [≥18.5 and 25 kg/m2] | 0.98 [0.60-1.59] | ||||

| Obese [≥30 and < 40 kg/m2] vs normal [≥18.5 and < 25 kg/m2] | 0.78 [0.38-1.54] | ||||

| Extreme obese [≥40 kg/m2] vs normal [≥18.5 and < 25 kg/m2] | 0.95 [0.21-4.02] | ||||

| Tobacco use | Current vs never | 1.71 [0.70-4.30] | 0.4352 | ||

| Former vs never | 1.18 [0.74-1.86] | ||||

| Baseline corticosteroid use | No vs yes | 1.43 [0.93-2.21] | 0.1045 | 1.71 [1.05-2.80] | 0.0441 |

| Baseline immunomodulator use | No vs yes | 0.86 [0.52-1.43] | 0.5607 | ||

| Duration of UC | <3 vs ≥ 7 years | 1.74 [1.07-2.85] | 0.0307 | 1.92 [1.10-3.34] | 0.0128 |

| ≥3 to < 7 vs ≥ 7 years | 1.88 [1.10-3.24] | 2.32 [1.28-4.23] | |||

| Baseline disease locationb | Left-sided colitis vs pancolitis | 1.85 [1.19-2.91] | 0.0059 | ||

| Baseline faecal calprotectin | ≤250 vs > 250 μg/g | 1.63 [0.82-3.25] | 0.1600 | ||

| Baseline CRP | ≤6 vs 6 mg/L | 1.45 [0.93-2.27] | 0.1036 | ||

| Baseline MMS | Moderate [4–6] vs severe [7–9] | 0.79 [0.52-1.19] | 0.2595 | ||

| Baseline ES | 2 vs 3 | 0.99 [0.64-1.52] | 0.9553 | ||

| Baseline SF subscore | <3 vs 3 | 0.98 [0.65-1.49] | 0.9412 | ||

| Baseline RB subscore | <2 vs ≥ 2 | 0.87 [0.57-1.32] | 0.5106 | ||

| Prior biologic or tofacitinib failure | Not failed vs failed | 1.59 [1.03-2.48] | 0.0375 | ||

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; ES, endoscopic score; HEMR, histological-endoscopic mucosal remission; MMS, modified Mayo Score; NA, not applicable; NRI, non-responder imputation; OR, odds ratio; RB, rectal bleeding; SC, subcutaneous; SF, stool frequency; UC, ulcerative colitis.

aOnly includes responses from US sites.

bThree patients with proctitis were combined with left-sided colitis when examining disease location.

3.4 Predictive value of histological, endoscopic, and histological-endoscopic induction endpoints

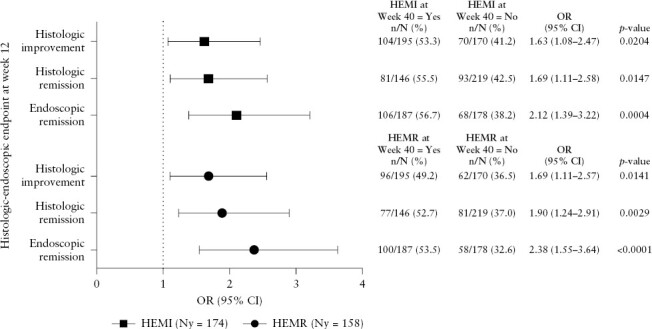

Achievement of histological improvement, histological remission, or endoscopic remission at Week 12 was significantly associated with achievement of composite histological-endoscopic endpoints [HEMI and HEMR] after 40 weeks of maintenance mirikizumab therapy [all p <0.05] [Figure 3]. When comparing the magnitude of the effect, a stronger association was seen for endoscopic remission at Week 12 compared with either histological endpoint [histological improvement or histological remission] at Week 12 among patients achieving HEMI [OR 2.12] or HEMR [2.38] at Week 40 [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Association between histological or endoscopic outcomes at Week 12 in LUCENT-1 and histological-endoscopic mucosal improvement [HEMI] or histological-endoscopic mucosal remission [HEMR] at Week 40 in mirikizumab induction responders re-randomised to mirikizumab 200 mg SC. Histological improvement was defined using the Geboes scoring system: neutrophil infiltration of <5% of crypts; no crypt destruction; and no erosions, ulcerations, or granulation tissue [Geboes score ≤3.1]. Histological remission was defined using the Geboes scoring system, with no lamina propria neutrophils; no neutrophils in the surface or crypt epithelium; no crypt destruction; and no erosions, ulcerations, or granulation tissue [Geboes score ≤2B.0]. Endoscopic remission was defined as Mayo endoscopic subscore = 0 or 1 [excluding friability]. HEMI was defined as achieving histological improvement and endoscopic remission. HEMR was defined as achieving histological remission and endoscopic remission. p-value for the OR of the binary outcomes was calculated by chi square test. CI, confidence interval; Ny, number of patients achieving the histological-endoscopic endpoint among mirikizumab induction responders re-randomised to mirikizumab 200 mg SC at Week 40 in LUCENT-2; OR, odds ratio; SC, subcutaneous.

Evaluation of the associations between histological, endoscopic, and histological-endoscopic endpoints at Week 12 with clinical outcomes at Week 40 [Supplementary Table 2] showed that endoscopic remission at Week 12 was significantly associated with clinical remission and corticosteroid-free remission at Week 40, and that histological remission, HEMI, and HEMR at Week 12 were associated with corticosteroid-free remission, clinical remission, and symptomatic remission at Week 40. Histological improvement at Week 12 was significantly associated with clinical remission and symptomatic remission at Week 40.

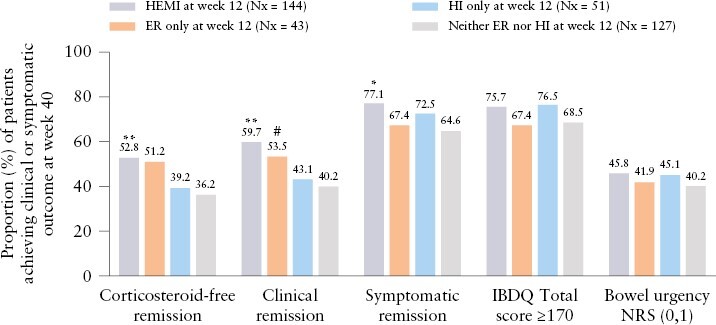

The proportions of patients achieving clinical or symptomatic endpoints [corticosteroid-free remission, clinical remission, symptomatic remission, IBDQ remission, and bowel urgency remission] at Week 40 in LUCENT-2 were compared among patients who were re-randomised to receive mirikizumab 200 mg SC and had achieved HEMI [N = 144], endoscopic remission only [N = 43], histological improvement only [N = 51], and neither histological improvement nor endoscopic remission [N = 127] at Week 12 in LUCENT-1 [Figure 4]. Patients who achieved HEMI at Week 12 had significantly greater rates of corticosteroid-free remission, clinical remission, or symptomatic remission at Week 40 compared with those who did not achieve histological improvement or endoscopic remission [all p <0.05]. Patients who achieved histological improvement only or endoscopic remission only at Week 12 had numerically greater rates of corticosteroid-free remission, clinical remission, or symptomatic remission at Week 40 compared with patients achieving neither histological improvement nor endoscopic remission, but these comparisons were not statistically significant. In addition, patients who achieved HEMI at Week 12 had significantly greater rates of clinical remission at Week 40 compared with patients who achieved histological improvement only at Week 40 [p = 0.049]. The rates of IBDQ remission [IBDQ score ≥170] and bowel urgency remission at Week 40 were numerically higher among patients who achieved histological improvement only or HEMI at Week 12, compared with patients achieving neither histological improvement nor endoscopic remission at Week 12, but these differences were not statistically significant. Overall, these results are consistent with the predictive benefit of a composite histological-endoscopic mucosal endpoint over endoscopic or histological endpoints alone for longer-term clinical outcomes.

Figure 4.

Proportion of patients achieving clinical or symptomatic outcomes at Week 40 based on Week 12 histological-endoscopic outcomes. Histological-endoscopic mucosal improvement [HEMI] was defined as histological improvement [HI, neutrophil infiltration of <5% of crypts; no crypt destruction; and no erosions, ulcerations, or granulation tissue [Geboes score ≤3.1]] and endoscopic remission (ER, Mayo endoscopic subscore = 0 or 1 [excluding friability]). ER only was defined as ER without HI. HI only was defined as HI without ER. IBDQ remission was defined as IBDQ score ≥170. Pairwise comparisons by Fisher’s exact test. *p <0.05, **p <0.01 vs neither HI nor ER; #p <0.05 vs HI only. IBDQ, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; IV, intravenous; NRS, numerical rating scale; Nx, number of patients achieving the histological-endoscopic endpoint among patients randomised to mirikizumab 300 mg IV at Week 12 in LUCENT-1.

Separate logistic regression analyses were conducted which included histological improvement and endoscopic remission at Week 12 as independent variables, and clinical remission and corticosteroid-free remission at Week 40 as outcomes, to assess whether histology at Week 12 was independently predictive of clinical outcomes at Week 40 after controlling for endoscopy. Endoscopic remission at Week 12 was the only statistically significant predictor for both clinical remission and corticosteroid-free remission at Week 40 [p <0.05] [Table 4]. After adjusting for endoscopic remission at Week 12, histological improvement at Week 12 was numerically improved, but the association between histological improvement at Week 12 and Week 40 outcomes was not statistically significant. Similar results were seen when endoscopic normalisation at Week 12 and histological remission at Week 12 were included as independent variables to predict clinical remission [p <0.05] and corticosteroid-free remission at Week 40 [p = 0.052] [Table 5]. Therefore, the independent prognostic value of histology over endoscopy was not demonstrated in these analyses.

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of the association between histological improvement and endoscopic remission at Week 12 in LUCENT-1 and dependent variables of corticosteroid-free remission and clinical remission at Week 40 in LUCENT-2 in mirikizumab induction responders who were re-randomised to mirikizumab 200 mg SC in LUCENT-2

| Variable | Corticosteroid-free remission at Week 40 | Clinical remission at Week 40 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | p-value | OR [95% CI] | p-value | |

| Histological improvement at Week 12 | 1.19 [0.71-1.99] | 0.5070 | 1.33 [0.79-2.23] | 0.2905 |

| Endoscopic remission at Week 12 | 1.71 [1.03-2.87] | 0.0414 | 1.78 [1.06-3.00] | 0.0304 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SC, subcutaneous.

Table 5.

Logistic regression analysis of the association between histological remission and endoscopic normalisation at Week 12 in LUCENT-1 and dependent variables of corticosteroid-free remission and clinical remission at Week 40 in LUCENT-2 in mirikizumab induction responders who were re-randomised to mirikizumab 200 mg SC in LUCENT-2

| Variable | Corticosteroid-free remission at Week 40 of LUCENT-2 | Clinical remission at Week 40 of LUCENT-2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | p-value | OR [95% CI] | p-value | |

| Histological remission at Week 12 | 1.38 [0.86-2.22] | 0.1908 | 1.37 [0.85-2.23] | 0.1986 |

| Endoscopic normalisation at Week 12 | 2.18 [1.03-4.93] | 0.0517 | 2.82 [1.25-7.10] | 0.0193 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; SC, subcutaneous.

3.5 Correlations between histological and/or endoscopic outcomes and clinical outcomes at Week 40

At Week 40 of LUCENT-2, 22.2% [81/365] of patients had achieved endoscopic normalisation, and twice as many [48.5%, 177/365] had achieved histological remission [ie, absence of neutrophils in the mucosa]; 84% [68/81] of patients who achieved endoscopic normalisation had also achieved histological remission.

The proportion of patients re-randomised to receive mirikizumab 200 mg SC, who achieved corticosteroid-free remission, clinical remission, symptomatic remission, IBDQ remission, and bowel urgency remission at Week 40, was compared among those who achieved alternate HEMR [ie, histological remission and endoscopic normalisation] [N = 68], endoscopic normalisation only [N = 13], histological remission only [N = 109], and neither histological remission nor endoscopic normalisation [N = 175] at Week 40 in LUCENT-2 [Figure 5]. Patients who achieved alternate HEMR at Week 40 were significantly more likely to also achieve all clinical and symptomatic outcomes at Week 40 than patients who achieved neither histological remission nor endoscopic normalisation. Similarly, patients who achieved histological remission only were significantly more likely to achieve most clinical outcomes and had numerically higher rates of bowel urgency remission than patients who achieved neither histological remission nor endoscopic normalisation. Patients who achieved endoscopic normalisation only were significantly more likely to achieve corticosteroid-free remission and clinical remission at Week 40 compared with those who achieved neither histological remission nor endoscopic normalisation, and had numerically higher rates of symptomatic remission, IBDQ remission, and bowel urgency remission. However, only 13 patients achieved endoscopic normalisation only [ie, without histological remission], which limits the interpretation of the comparisons in this group. Patients who achieved alternate HEMR also had significantly higher rates of corticosteroid-free remission and clinical remission compared with patients who achieved histological remission only, and alternate HEMR was the only endpoint that was significantly associated with bowel urgency remission at Week 40. These results suggest that a composite histological-endoscopic endpoint at Week 40 is more closely associated with clinical, symptomatic, and quality-of-life endpoints than a histological endpoint only. However, the sample sizes were too small to make valid comparisons between alternate HEMR and endoscopic normalisation only.

Figure 5.

Proportion of patients achieving clinical or symptomatic outcomes at Week 40 based on Week 40 histological-endoscopic outcomes. Alternate histological-endoscopic mucosal remission [HEMR] was defined as histological remission [HR, Geboes score ≤2B] and endoscopic normalisation [EN, Mayo endoscopic subscore = 0]. EN only was defined as EN without HR, and HR only was defined as HR without EN. IBDQ remission was defined as IBDQ score ≥170. Pairwise comparisons by Fisher’s exact test. *p <0.05, **p <0.01, ***p <0.001 vs neither HR nor EN; #p <0.05 vs HR only. IBDQ, Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire; NRS, numerical rating scale; Ny, number of patients achieving the histological-endoscopic endpoint among mirikizumab induction responders randomised to mirikizumab 200 mg SC at Week 40 in LUCENT-2; SC, subcutaneous.

4. Discussion

This is the first analysis of phase 3 data of a humanised monoclonal antibody directed against the p19 subunit of IL-23, to report histological and histological-endoscopic outcomes in UC. A greater proportion of patients treated with mirikizumab achieved histological improvement, histological remission, endoscopic remission, HEMI, or HEMR compared with placebo in the Week-12 induction [LUCENT-1] and Week-40 maintenance [LUCENT-2] periods. These results are consistent with superior clinical, endoscopic, and symptomatic outcomes for mirikizumab-treated patients from the LUCENT-1 and -2 trials17 and were achieved regardless of previous biologic or tofacitinib treatment.

Neutrophilic inflammation has consistently been identified as a determinant of UC disease activity,19 and patients who achieve targeted absence of neutrophils have improved longer-term outcomes.6,20–22 In several studies, only the complete absence of mucosal neutrophilic inflammation, assessed by histology, predicted reduced rates of corticosteroid use, hospitalisation, and colectomy in patients with UC.19,20,22 Histological remission [determined by Geboes score ≤2B.0] represents the complete absence of mucosal neutrophilic inflammation and, because neutrophils are not normally present in healthy colon mucosa, the absence of intra-epithelial neutrophils has also been recommended as a minimum requirement for defining histological remission, in a European Crohn’s Colitis Organisation position paper and other recent literature.6,19 Improvement and/or resolution of inflammation in UC, measured by histological assessment and endoscopic measures, compared with endoscopic measures alone, is strongly associated with lower rates of clinical relapse, corticosteroid use, hospitalisation, and colectomy.7,9,11 LUCENT-1 and LUCENT-2 included treatment endpoints that combined histology and endoscopy assessments [HEMI and HEMR] as well as histology outcomes alone [histological improvement and histological remission].

Patients who received mirikizumab in LUCENT-1 or LUCENT-2 achieved higher rates of histological improvement, histological remission, HEMI, or HEMR compared with placebo, indicating that mirikizumab was effective in reducing and/or resolving microscopic inflammation in UC. This effect was observed at Week 12 and was maintained over 40 weeks of maintenance treatment, and was also observed in patients who had previously failed biologic or tofacitinib therapy and in those who had no prior biologic or tofacitinib therapy failure. In LUCENT-1 at Week 12, statistically significant improvements were observed in histological endpoints in patients with and without prior biologic or tofacitinib failure. In LUCENT-2 at Week 40, a large effect size [common risk difference vs placebo >20%] was observed for all histological and histological-endoscopic endpoints in patients with and without prior biologic or tofacitinib failure. This shows that mirikizumab is effective in inducing and maintaining a treatment response even in patients who are generally difficult to treat and require additional treatments.13 Histological assessment in UC is a relatively new concept, and additional long-term outcome studies will help to promote consensus on criteria defining histological mucosal healing. Data from the ongoing LUCENT-3 long-term extension study [NCT03519945] will allow additional analyses, including associations and prognostic value of histological and histological-endoscopic endpoints with longer-term outcomes, including corticosteroid use, hospitalisations, and surgery.

In LUCENT-1, univariable analysis identified lower age, female sex, left-sided colitis, low faecal calprotectin, low CRP, moderate MMS, low ES, low SF subscore, and no prior biologic or tofacitinib failure as candidate predictors of patients achieving HEMI at Week 12. From multivariable analysis, female sex, lower disease activity [low CRP, ES, and SF subscore], and no prior biologic or tofacitinib failure were significant prognostic factors of achieving HEMI at Week 12 among mirikizumab patients. In addition, no immunomodulator use was a significant prognostic factor in achieving HEMI at Week 12 in the multivariable analysis. This indicates that concomitant immunomodulator use was not associated with improvements in mirikizumab induction treatment efficacy, which is consistent with studies on non anti-TNF biologic agents.23,24 Whereas this study did not identify factors that were significantly predictive of mirikizumab efficacy over placebo, the multivariable analyses suggest baseline disease inflammatory activity is prognostic of mirikizumab patients achieving HEMI at Week 12.

Consistent with the univariable analysis conducted for HEMI in LUCENT-1, similar baseline factors [lower weight, no baseline corticosteroid use, left-sided colitis, low faecal calprotectin, low CRP, and no prior biologic or tofacitinib failure] were identified as candidate predictors of achieving HEMR at Week 40 of LUCENT-2. From multivariable analysis, baseline corticosteroid use and duration of UC were significant baseline prognostic factors. Multivariable analysis identified that patients who had <3 years’ and between 3 and 7 years’ duration of UC were positively associated with achieving HEMR after 40 weeks of maintenance treatment with mirikizumab, compared with patients with >7 years’ disease duration. This finding may suggest that longer disease duration [≥7 years] is a negative predictor of achieving HEMR and could be related to the need for early biologic therapy. Furthermore, our analysis showed that for mirikizumab induction responders at Week 12 who continued mirikizumab treatment for an additional 40 weeks, the probability of achieving HEMR at Week 40 of LUCENT-2 was not strongly associated with baseline disease severity or prior biologic or tofacitinib treatment.

Analyses to determine the prognostic value of histological, endoscopic, and composite histological-endoscopic endpoints at Week 12 in LUCENT-1, with clinical and symptomatic endpoints at Week 40 in LUCENT-2, support HEMI as a clinically meaningful endpoint. Early achievement of HEMI at the end of induction therapy in LUCENT-1 was a numerically better prognostic indicator for clinical and symptomatic outcomes at the end of maintenance therapy in LUCENT-2 than histological improvement alone or endoscopic remission alone. Although HEMR may be a better predictor of even longer-term health outcomes, the current data do not allow comparisons of the associations beyond 52 weeks of treatment.

To determine the clinical relevance of histological, endoscopic, and composite histological-endoscopic endpoints, we also evaluated outcomes at Week 40 of LUCENT-2 in patients randomly assigned to mirikizumab 200 mg SC for 40 weeks, who had or had not achieved these endpoints after mirikizumab induction at Week 12. Patients who achieved histological or endoscopic improvement and remission after mirikizumab induction treatment were more likely to achieve the composite histological-endoscopic endpoints [HEMI and HEMR] at maintenance. In addition, endoscopic remission at induction had a stronger association with achievement of clinical remission and corticosteroid-free remission at Week 40 [Supplementary Table 2]. This may be because clinical remission and corticosteroid-free remission, which are composite endpoints that include an endoscopic component, have overlapping endpoint definitions that may have confounded the results. Interestingly, endoscopic remission at the end of induction therapy in LUCENT-1 was not statistically associated with achievement of symptomatic remission [p = 0.090], whereas histological improvement [p = 0.026], histological remission [p = 0.014], HEMI [p = 0.038], and HEMR [p = 0.024] at the end of induction therapy were significantly associated with symptomatic remission [Supplementary Table 2]. The importance of achieving histological remission, HEMI, and HEMR at the end of induction therapy at Week 12 was also demonstrated by the positive associations with corticosteroid-free remission, clinical remission, and symptomatic remission after 40 weeks of mirikizumab maintenance therapy, compared with those who did not achieve these endpoints after mirikizumab treatment.

Furthermore, most patients who achieved endoscopic normalisation after continuous treatment with mirikizumab also achieved histological remission. Achieving both endoscopic normalisation and histological remission [alternate HEMR] at Week 40 was associated with the best clinical, symptomatic, and quality-of-life outcomes.

Some key strengths of this analysis are that LUCENT-1 comprises a large dataset and that histological samples were blindly collected and centrally read. In addition, in order to capture the progression of treatment benefit from Week 12 through Week 52 of continous mirikizumab treatment, HEMR, which is a more stringent outcome than HEMI, was included as a major secondary objective in LUCENT-2. This approach was taken in recognition of the importance of the absence of neutrophils as minimum criterion for achieving histological remission, which has been shown to be more clinically relevant and predictive of longer-term outcomes.11,19,20,22 However, interpretation of the findings is limited by the duration of the study, a total of 52 weeks, which is a short period in which to show histological remission and HEMR, especially in patients who are difficult to treat. A long-term extension study, LUCENT-3, is currently ongoing, and additional studies are likely needed to determine the association between histological remission and histological-endoscopic mucosal healing with long-term, health-related quality-of-life outcomes in patients with UC. Furthermore, because the multivariable analysis for prediction of achieving HEMR focused on mirikizumab induction responders randomised to mirikizumab 200 mg SC in LUCENT-2, the findings may not be generalisable to other patient populations. Finally, because the associations in this study were derived from post hoc analyses, the findings are hypothesis-generating only, and caution is needed when interpreting the results.

In conclusion, mirikizumab, the first p19-targeted anti-IL-23 to be developed for UC, was more effective than placebo in reducing colonic inflammation as assessed by histological and histological-endoscopic outcomes. Overall, patients who achieved resolution of active colonic inflammation with absence of neutrophils in the mucosa at induction sustained this effect with continued mirikizumab treatment. Early resolution of endoscopic, histological, and histological-endoscopic inflammation with mirikizumab at induction was associated with improved clinical, symptomatic, and quality-of-life outcomes during maintenance. Incorporation of histological and histological-endoscopic outcomes as a potential endpoint or treatment target could improve current treatment strategies in UC. Combining targets in UC could be a strategy to improve patient outcomes, and histological remission could be used as an adjunct to endoscopic remission to represent a deeper level of healing.5,6

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all study participants.

Contributor Information

Fernando Magro, Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital São João, Porto, Portugal; CINTESIS@RISE - Health Research Network, Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal.

Rish K Pai, Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathology, Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, AZ, USA.

Taku Kobayashi, Center for Advanced IBD Research and Treatment, Kitasato University Kitasato Institute Hospital, Minato-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

Vipul Jairath, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Western University, London, ON, Canada; Alimentiv Inc., London, ON, Canada; Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Western University, London, ON, Canada.

Florian Rieder, Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Digestive Diseases and Surgery Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH, USA; Department of Inflammation and Immunity, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Isabel Redondo, Eli Lilly Portugal, Produtos Farmacêuticos Lda., Lisbon, Portugal.

Trevor Lissoos, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Nathan Morris, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Mingyang Shan, Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA.

Meekyong Park, TechData Service Company LLC, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet, University of Lorraine, Inserm, NGERE, Nancy, and Groupe Hospitalier Privé Ambroise Paré - Hartmann, Paris IBD Center, Neuilly sur Seine, France.

Funding

This work was supported by Eli Lilly and Company, manufacturer of mirikizumab. Medical writing assistance was provided by Joanna Best, PhD, and Serina Stretton, PhD, CMPP, of ProScribe—Envision Pharma Group, and was funded by Eli Lilly and Company. ProScribe’s services complied with international guidelines for Good Publication Practice. This manuscript, including related data, figures, and tables, has not been previously published and is not under consideration elsewhere.

Conflict of Interest

FM has served as a speaker and received honoraria from: AbbVie, Biogen, Falk, Ferring, Hospira, Laboratórios Vitória, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Vifor. RKP has receiving consulting fees from: AbbVie, Alimentiv, Allergan, Eli Lilly, Genentech, and PathAI. TK has received grants and/or contracts from: AbbVie, Activaid, Alfresa Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, EA Pharma, Eli Lilly Japan, Gilead Sciences, Google Asia Pacific, Janssen Japan, JIMRO, JMDC, Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Nippon Kayaku, Otsuka Holdings, Pfizer Japan, Takeda, and Zeria Pharmaceutical; has received lecture payments or honoraria from: AbbVie, Activaid, Alfresa Pharma, Galapagos, Janssen Japan, JIMRO, Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Nippon Kayaku, Pfizer Japan, Takeda, ThermoFisher Diagnostics, Zeria Pharmaceutical; has received payment for expert testimony from: AbbVie, Activaid, Alfresa Pharma, EA Pharma, Janssen Japan, KISSEI Pharmaceutical, Kyorin Pharmaceutical, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Nippon Kayaku, Pfizer Japan, and Takeda; and has participated on data safety monitoring boards or advisory boards for: Bristol-Myers Squibb, EA Pharma, Eli Lilly, and Janssen. VJ has received grants or contracts from: AbbVie, Adare, Atlantic, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene/Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Seres, Takeda, UCB Pharma, and VH Squared; has received consulting fees from: AbbVie, Alimentiv, Arena, Asahi, Asieris, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Ferring, Fresenius, Galapagos, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Kabi, Kasei Pharma, Landos Biopharma, Merck, Mylan, Organon Pandion, Pendopharm, Pfizer, Prometheus Biosciences, Protagonist Therapeutics, Reistone Biopharma, Roche, Sandoz, Second Genome, Takeda, Teva, Ventyx Biosciences, and Vividion Therapeutics; has received payments or honoraria from: AbbVie, Ferring, Galapagos, Janssen, Pfizer, and Takeda; and has participated on data safety monitoring or advisory boards for: AbbVie, Arena, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Fresenius, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Kabi, Mylan, Roche, and Takeda. FR has received consulting or advisory board fees from: AbbVie, Adnovate, Agomab, Allergan, Arena, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene/BMS, CDISC, Celsius, Cowen, Ferring, Galapagos, Galmed, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Gossamer, Guidepoint, Helmsley, Horizon Therapeutics, Image Analysis, Index Pharma, Jannsen, Koutif, Mestag, Metacrine, Mopac, Morphic, Organovo, Origo, Pfizer, Pliant, Prometheus Biosciences, Receptos, RedX, Roche, Samsung, Surmodics, Surrozen, Takeda, Techlab, Theravance, Thetis, UCB Pharma, Ysios, and 89Bio. IR, TL, NM, and MS are employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company. MP has nothing to disclose. LPB has received consulting fees from: AbbVie, Abivax, Alimentiv, Alma Bio Therapeutics, Amgen, Applied Molecular Transport, Arena, Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion, Connect Biopharma, Cytoki Pharma, Eli Lilly, Enthera, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Fresenius Kabi, Galapagos, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Gossamer Bio, H.A.C. Pharma, IAG, InDex Pharmaceuticals, Inotrem, Janssen, Medac, Mopac, Morphic, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Norgine, Novartis, OM Pharma, Ono Pharmaceutical, OSE Immunotherapeutics, Pandion Therapeutics, Pfizer, Prometheus Biosciences, Protagonist Therapeutics, Roche, Sandoz, Takeda, Theravance, ThermoFisher Diagnostics, TiGenix, Tillotts Pharma, Viatris, Vifor, and YSOPIA Bioscience; has received grants from: Celltrion, Fresenius Kabi, and Takeda; and has received lecture fees from: AbbVie, Amgen, Arena, Biogen, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Galapagos, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Medac, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Sandoz, Takeda, Tillotts Pharma, Viatris, and Vifor.

Author Contributions

All authors participated in the interpretation of study results and in the drafting, critical revision, and approval of the final version of the manuscript. IR and TL were involved in the study design and data analyses. FM, RKP, TK, VJ, FR, and LBP were investigators in the study. NM, MS, and MP conducted the statistical analysis. Eli Lilly and Company was involved in the study design, data collection, data analysis, and preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

Eli Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymisation, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the USA and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data-sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at [www.vivli.org].

References

- 1. Kobayashi T, Siegmund B, Le Berre C, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6:74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ho EY, Cominelli F, Katz J.. Ulcerative colitis: what is the optimal treatment goal and how do we achieve it? Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2015;13:130–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. D’Haens G, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. A review of activity indices and efficacy end points for clinical trials of medical therapy in adults with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2007;132:763–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Travis SP, Higgins PDR, Orchard T, et al. Review article: defining remission in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;34:113–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, et al.; International Organization for the Study of IBD. STRIDE-II: an update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease [STRIDE] initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD [IOIBD]: determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021;160:1570–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Magro F, Doherty G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. ECCO position paper: harmonisation of the approach to ulcerative colitis histopathology. J Crohns Colitis 2020;14:1503–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Christensen B, Hanauer SB, Erlich J, et al. Histologic normalization occurs in ulcerative colitis and is associated with improved clinical outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1557–64.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Colombel JF, Rutgeerts P, Reinisch W, et al. Early mucosal healing with infliximab is associated with improved long-term clinical outcomes in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2011;141:1194–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bryant RV, Burger DC, Delo J, et al. Beyond endoscopic mucosal healing in UC: histological remission better predicts corticosteroid use and hospitalisation over 6 years of follow-up. Gut 2016;65:408–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Magro F, Alves C, Lopes J, et al. Histologic features of colon biopsies [Geboes Score] associated with progression of ulcerative colitis for the first 36 months after biopsy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:2567–76.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li K, Marano C, Zhang H, et al. Relationship between combined histologic and endoscopic endpoints and efficacy of ustekinumab treatment in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2020;159:2052–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yoon H, Jangi S, Dulai PS, et al. Incremental benefit of achieving endoscopic and histologic remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2020;159:1262–75.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gordon JP, McEwan PC, Maguire A, Sugrue DM, Puelles J.. Characterizing unmet medical need and the potential role of new biologic treatment options in patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and clinician surveys. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;27:804–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baki E, Zwickel P, Zawierucha A, et al. Real-life outcome of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha in the ambulatory treatment of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2015;21:3282–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sandborn WJ, Ferrante M, Bhandari BR, et al. Efficacy and safety of mirikizumab in a randomized phase 2 study of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2020;158:537–49.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Monteleone I, Pallone F, Monteleone G.. Interleukin-23 and Th17 cells in the control of gut inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 2009;2009:297645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. D’Haens G, Dubinsky M, Kobayashi T, et al. Mirikizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2022; Submitted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jauregui-Amezaga A, Geerits A, Das Y, et al. A simplified Geboes score for ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:305–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pai RK, Hartman DJ, Rivers CR, et al. Complete resolution of mucosal neutrophils associates with improved long-term clinical outcomes of patients with ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;18:2510–7.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Estevinho MM, Magro F.. Epithelial neutrophilic infiltrate: the rising star in ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;20:e1509–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ma C, Sedano R, Almradi A, et al. An international consensus to standardize integration of histopathology in ulcerative colitis clinical trials. Gastroenterology 2021;160:2291–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Narula N, Wong ECL, Colombel JF, et al. Early change in epithelial neutrophilic infiltrate predicts long-term response to biologics in ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;20:1095–104.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hu A, Kotze PG, Burgevin A, et al. Combination therapy does not improve rate of clinical or endoscopic remission in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases treated with vedolizumab or ustekinumab. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:1366–76.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yzet C, Diouf M, Singh S, et al. No benefit of concomitant immunomodulator therapy on efficacy of biologics that are not tumor necrosis factor antagonists in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;19:668–79.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Eli Lilly provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymisation, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the USA and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data-sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at [www.vivli.org].