Abstract

Diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) affects a significant number of postpartum women, while its treatments are still under debate. This study aimed to systematically evaluate the effectiveness of rehabilitation training programs for postpartum DRA treatment. Four databases were systematically searched to identify eligible studies published up to February 1, 2023. We followed the PRISMA for scoping reviews guideline in this study. The characteristics and the main findings of the included studies were extracted. Sixteen studies enrolling 1129 women during the ante- and/or postnatal period were included. The common rehabilitation training for DRA included physical exercise, non-exercise physical therapy, acupuncture, and electrotherapy. The presence of DRA could be diagnosed by ultrasound, caliper, or palpation, of which ultrasound had the best reliability. Besides, these assessments could also be used for evaluating the therapeutic efficacy after the rehabilitation training programs. Several studies concluded that patients with DRA could be effectively improved by specific interventions. But a few included studies revealed rehabilitation training might be not more effective than no interventions when treating DRA. For example, some investigators did not recommend physical exercise for DRA patients due to this intervention during pregnancy kept the linea alba less stressed by maintaining abdominal tone, strength, and control, and therefore might aggravate DRA. However, it should be noted that this evidence was derived from limited studies (16/60, 27 % papers) with small samples. To some extent, women with postpartum DRA can benefit from the specific rehabilitation regimen by alleviating postpartum inter-rectus distance. Further research is still warranted to propose strategies for improving postpartum DRA.

Keywords: Diastasis recti abdominis, Postpartum, Rehabilitation training, Pelvic floor muscle, Treatment

1. Introduction

Diastasis rectus abdominis (DRA), a common disease affecting numerous postpartum women, induces by the stretching of the abdominal muscles and adjacent connective tissue as the fetus grows [1]. Separation occurs along the linea alba (LA) between the rectus abdominis muscles due to increased pressure in the abdomen. A widening of the linea alba that is greater than 2 cm is referred to as rectus diastasis (RA) [2]. This condition is widespread in both pregnant and postpartum women, with a prevalence rate of 70 % in the final trimester of pregnancy, 60 % at 6 weeks after delivery, and 30 % at 12 months [3,4]. Though the prevalence of DRA is high, its precise pathogenesis is yet unknown. The abdominal wall plays a crucial role in posture, breathing, trunk and pelvic stability, and support of the abdominal viscera. These processes are jeopardized by an increase in the inter-recti distance, which can also weaken the abdominal muscles and affect their functions [5,6]. Changes in trunk mechanics, decreased pelvic stability, and altered posture can lead to injury of the lumbar spine and pelvis [6,7]. Numerous research findings addressing the effects of DRA have been published. When women are in the early postpartum phase, stomach discomfort is strongly correlated with DRA [8,9]. Physical symptoms in women at various times following birth include lower back pain, pelvic floor dysfunction, and alternations in abdominal muscle function. Incontinence of the urine, fecal incontinence, and pelvic organ prolapse are all common pelvic floor dysfunctions. It has a significant impact on postpartum women's lives [10].

Although DRA is gradually discovered as a common clinical problem, its management and prevention are still little known. Some risk factors such as maternal age, multiparity, and childcare obligations have been related to DRA. Surgical treatment of DRA has been demonstrated to lower some of the negative symptoms of a broad diastasis such as back pain [11]. Even after a patient has had surgery, the occurrence of DRA is still a possibility. There aren't many studies in the literature that mention a negligible recurrence rate [12,13]. Conservative therapy is regarded as one of the primary treatments for DRA. Although only a small number of studies have investigated the effects of exercise therapy in treating DRA, the main advantage of exercise therapy is that it is a non-invasive management [14]. Interestingly, regular exercise before pregnancy appears to reduce the risk of DRA and narrow the inter-rectus distance [15]. Abdominal exercises are also routinely offered to postnatal women who have DRA. Other common non-surgical treatments for women with DRA include aerobic exercise, instruction in proper posture and back care, and external support such as a corset or Tubigrip [16,17].

At present, it is unknown which types of non-surgical interventions (i.e., exercise) are effective in preventing and/or reducing DRA. In a systematic review of the effects of abdominal training on DRA reported by Benjamin et al. [18], little high-quality literature on this subject was presented. The authors summarized the outcomes of abdominal training in preventing or treating DRA. Gluppe et al. [19] published a meta-analysis of abdominal and pelvic floor muscle training for managing with postpartum DRA in 2021. The authors found that there was very little high-quality scientific evidence supporting specific exercise regimens for the treatment of postpartum DRA. In 2022, Radhakrishnan et al. [14] summarized the etiology, diagnosis, treatment of DRA, and rehabilitative benefits of abdominal therapeutic exercise. To determine which exercises were most effective for speeding up problem-solving, further investigation and experimentation were strongly recommended.

Since DRA is a concerning public health problem, it has not been given enough attention, especially for its management. Therefore, the purpose of this review was to summarize the current evidence of rehabilitative training programs for treating postpartum DRA.

2. Methods

2.1. Data sources and searches

We have systematically searched four electronic databases, including the MEDLINE (PubMed), the Embase databases., the Cochrane Library databases, the PsychINFO, the Scopus, and the Web of science to find eligible studies. The timeframe spanned from the inception of these databases to February 1, 2023. We only included human participant research that acknowledged utilizing the English language. The PRISMA scoping review checklist was listed in Supplementary Table 1. The following search terms were used in different combinations in PubMed: (((((((rehabilitation) OR (physiotherapy’)) OR (exercises')) OR (abdominal exercises)) OR (Physical therapy)) OR (treatment)) AND (((diastasis abdominis) OR (Diastasis Recti Abdominis)) OR (linea alba))) AND ((postpartum) OR (pregnance)). Also, reference lists and related studies were manually searched for detecting eligible studies. The keywords for searching included ‘Diastasis Recti Abdominis’, ‘postpartum women’, ‘abdominal exercises’, ‘physiotherapy’, ‘exercises’, ‘Physical therapy’, ‘pregnancy’, ‘treatment’, ‘linea alba’, and ‘rehabilitation’.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

The criteria for the selection of the eligible studies included: 1) participants (articles including a population of postpartum women with DRA; 2) the design of the studies (observational or interventional studies, any study design); 3) the type and definition of intervention (i.e., physiotherapy, exercise, conservative management, and other interventions); 4) comparative group (with or without a control group); 5) outcomes (IRD, quality of life, and urogynecological symptoms). According to the inclusion criteria, the screening and eligibility process were independently performed by two authors. For the ambiguities between the two authors during these processes, they would be resolved by the corresponding author or the third author.

2.3. Data extractions

We extracted data on training dose interventions (intervention style, intervention duration, frequency, training volume, and adherence), measurement methods, and primary and secondary outcome indicators. Besides, we also listed the name of the first author, publication year, geographic distribution, study design, number of study groups and controls, and IRD measurements for each included study.

2.4. Quality assessment

The methodological quality of the RCTs was evaluated by the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing the risk of bias, while that of other included studies were assessed by the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS). The NOS checklist contains nine items. The gaining scores of 0–3, 4–6, and 7–9 represent low quality, moderate quality, and high quality, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Literature search

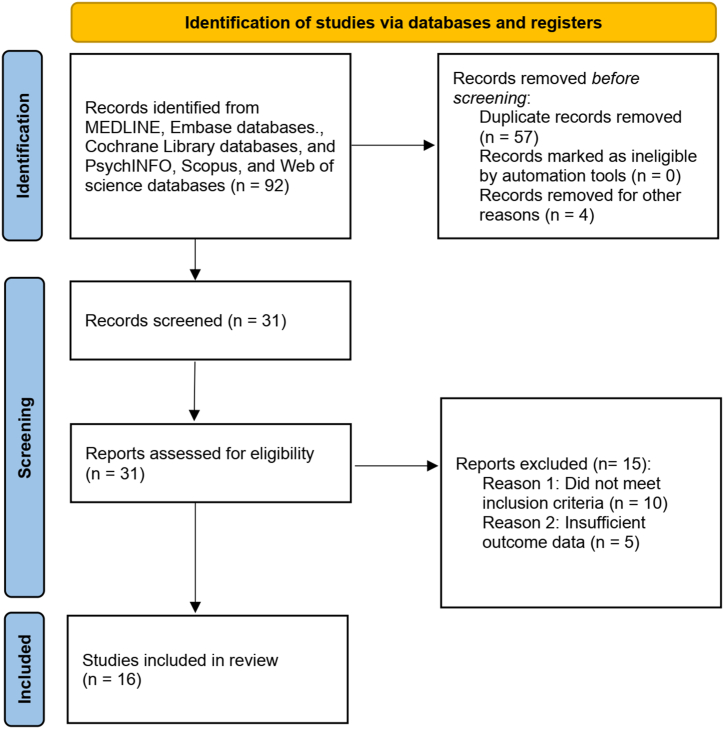

The selection procedure for screening the potentially included studies depended on a common selection strategy. As shown in Fig. 1, in total, 92 studies were found in the four databases during the initial search. Sixty-one publications were removed after being removed of duplicates, studies unrelated to the research topic, non-clinical studies, reviews, comments, and case reports. The remaining 31 studies were then obtained for full-text analysis. Of these potential studies, eleven papers were eliminated because they did not address the research issue, and four studies did not satisfy the inclusion requirements. In the end, sixteen studies were considered eligible and thus used for further analysis.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study selection.

3.2. Study characteristic

Table 1 listed the sixteen eligible studies on the topic of rehabilitation training in DRA. The study design in the 16 included studies was RCT, cohort, or case series. There were seven [[20], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25], [26]] RCT studies and nine studies were cohort or case series. These studies were published between 2017 and 2023. Studies were conducted in the United States (1 study), Norway (1 study), Canada (1 study), China (5 studies), New Zealand (2 studies), Iran (1 study), South Korea (2 studies), Egypt (1 study), and Spain (1 study). The sample sizes in each of the independent study ranged from 3 to 294. Rectus abdominis spacing was evaluated mainly by the finger widths (3 studies), digital nylon calipers (4 studies), and ultrasound (10 studies) measurements. Variables might be the confounding factors for the efficiencies of rehabilitative treatments. The variables reported in the 16 included were listed in Table 1. These variables included age, BMI, child's birth weight, hypermobility, physical activity, parity, height, weight, the numbers of pregnancies, physical activity, abdominal exercises, IRD, pain, disability, and proprioception.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Study/Reference | Assessments | Interventions | Sample size | Duration of Treatment protocol | Main findings | Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kamel et al. [27] 2017 Egypt | Ultrasound | Group A received NMES in addition to abdominal exercises; Group B received only abdominal exercises. |

60 women | NMES (34 ± 5 mA) and then followed by the abdominal exercises; 8 weeks: three times per week |

In postnatal women, NMES reduces DRAM; if combined with abdominal exercises, its effect is amplified. | NA |

| Gluppe et al. [20] 2018 Norway |

Finger widths | PFM, combined with strengthening exercises. | Intervention group: n = 85; Control group: n = 88 |

PFM exercises: 5 different positions and 8–12 attempts of maximal contraction; 16 weeks, the intervention lasted for 45 min in each time. |

There were 55.2 % and 54.5 % of participants in the intervention and control groups with diastasis at 6 weeks postpartum, respectively. At baseline, there was no significant difference in prevalence between groups (RR = 1.01, 95%CI: 0.77–1.32), as well as at 6 months postpartum (RR = 0.99, 95%CT: 0.71–1.38), or at 12 months postpartum (RR = 1.04, 95%CI: 0.73–1.49). There were no significant reductions in DRA prevalence with a weekly comprehensive exercise program focusing on PFM strength training and home training. | Age, BMI, Child's birth weight, hypermobility, physical activity |

| Thabet et al. [28] 2019 Egypt | Digital nylon calipers | Deep core stability strengthening program (+ traditional exercises). Group A: application of abdominal binding, breathing maneuvers, PFM exercises, planks, and isometric abdominal contractions. Deep core stability strengthening program (+ traditional exercises). Group B: Traditional abdominal exercises static abdominal contractions, posterior pelvic tilt, reverse sit-up, trunk twist and reverse trunk. |

40 women: two groups (n = 20 in each group) | Deep core stability-strengthening program: abdominal bracing, diaphragmatic breathing, pelvic floor contraction, plank, and isometric abdominal contraction; 8 weeks, 3 times a week |

There is a significant difference between the group doing Deep Core Training and the group doing Traditional exercises (P = 0.0001). Women with diastasis recti can benefit from deep core stability exercises that improve their quality of life postpartum. | NA |

| Depledge et al. [21] 2021 New Zealand | Ultrasound | Exercises performed: 1): abdominal drawing in with pelvic floor activation; 2): trunk curl up with scapula just off the plinth; 3): Sahrmann leg raise with hip flexion to 90°; 4): modified McGill side lying plank. |

32 women | NA 3 weeks |

Among the exercises tested, curl-ups were most effective in reducing the inter-rectus distance. In the absence of any exercises that induced diastasis of the rectus muscle, they could not be considered potentially harmful. In these exercises, both tuggrip and taping did not enhance results. | Age, BMI, height, parity |

| Hu et al. [29] 2021 China |

Ultrasound | Standardized rehabilitation group (SR) and non-standardized rehabilitation group (non-SR) | 294 women: SR group (n = 171) and non-SR group (n = 123) | 20 days: including 40 min of manual massage (Part 1) and 30 min of treatment with electrophysiological equipment (Part 2). Once every other day, and 10 times. | SR experienced significant reductions in rectus abdominis separation compared to non-SR (P < 0.0001). An analysis of multiple linear regression models showed that standardized rehabilitation had an independent effect on parturients' prognosis for DRA (p < 0.0001). Furthermore, the quality of life of the study group (SR) was significantly improved (p < 0.0001). | Age, BMI, numbers of pregnancies |

| Laframboise et al. [30] 2021 USA |

Nylon calipers | ‘Virtually’ exercise intervention | 8 women | A wide range of exercise variations: glute bridges, lying supine, lift glutes while shoulders stay planted, etc. 12 weeks: three exercise sessions per week |

Two sites measuring DRA width showed a significant interaction between group and time, 2 inches above navel (rest) (P = 0.007, d = 0.67) and 2 inches above navel (active) (P = 0.005, d = 0.69). Postpartum women may benefit from virtual exercise interventions to decrease DRA severity. | NA |

| Liu et al. [31] 2021 China |

Ultrasound | Acupuncture and physical training | 144 women (three group, n = 48 in each): Acupuncture and physical training, the sham group received sham acupuncture and physical training, and the physical training group received physical training | Acupuncture group: 7 acupoints were selected; 2 weeks: 30 min once/day, five times a week. Physical training group: abdominal breathing, leg rotation, stretch legs, and ventral flat training; 10 times on each side. |

This is a Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial study protocol, thus no results on the effectiveness were presented. | NA |

| Keshwani et al. [23] 2021 Canada | Ultrasound | 1) exercise therapy alone; 2) abdominal binding alone; 3) combination therapy: both exercise therapy and abdominal binding; 4) control: no intervention) | 32 women: four groups (8 women in each) | Weekly individualized sessions were provided by a registered physiotherapist. Total 12 weeks: 8 to 12 sessions, first session 1 h, subsequent sessions 30–45 min. | Both abdominal binding alone and combination therapy had positive effects on body image (Cohen's d (d) = 0.2–0.5). The combination therapy group showed a positive effect on trunk flexion strength (d = 0.7). Combining abdominal binding with exercise therapy has been associated with positive, clinically meaningful effects not only on body image outcomes but also on trunk flexion strength. Urogynecological symptoms or overall function did not appear to be affected by any of the interventions, positive or negative. | Weight, BMI, physical activity |

| Kirk et al. [32] 2021 USA |

Finger-width | Manual therapy: e.g. visceral manipulation (VM), myofascial release, muscle energy technique, and trigger point release therapies. | 3 women | Each patient received over four treatments of visceral manipulation. Case one:18 weeks once every three to four weeks; Case two: 12 sessions of physical therapy more than 36 weeks. Case three: six sessions of physical therapy that lasting over 26 weeks. |

Three women with DRA experienced a reduction in IRD, a decrease in numeric pain rating scores, and an improvement in functional activities by the use of VM. Additionally, bladder and bowel symptoms also improved. | NA |

| Depledge et al. [22] 2022 New Zealand | Ultrasound | Wearing either Tubigrip or a rigid abdominal belt | 62 women | Wear the Tubigrip for as many hours as a patient was comfortable during the day; Record the hours the Tubigrip was worn each day. A total of 8 weeks |

As a result of the eight weeks intervention, the mean RA diastasis reduced by 46 % to 2.5 cm, but the difference was not statistically significant across groups (P > 0.05). Compared to the belt group (median: 81 h), the Tubigrip group wore them for significantly more hours (p < 0.05) than the belt group (median: 275 h). Neither Tubigrip nor the belt were associated with a percentage reduction of RA diastasis among women who wore them for a specific period of time (P > 0.05). Baseline diastasis levels did not differ significantly between vaginal delivery and Caesarean section. A significant difference was found in the percent reduction of the RA diastasis between interventions (vaginal delivery mean: 48 % vs C-section: 40 %, P < 0.05). | NA |

| Liang et al. [33] 2022 China | Ultrasound | Study group: BAPFMT and NMES; Control group: NMES | 66 women (n = 33 in each): study group and control group | BAPFMT sessions: the MLD B8Plus Pelvic Floor Biofeedback Rehabilitation System; NMES: electrode probe was placed intra-vaginally, with two surface patch electrodes on the abdomen. A total of 6 weeks |

At 6 weeks, there was a significant reduction in IRD in the study group. After 6 weeks, the study group showed a significant improvement on the physical component summary, which is an integral part of the SF-36 questionnaire. It is feasible to implement a postpartum programme including BAPFMT for women with RD and to improve the physical quality of life of those women. | Abdominal exercises |

| Liu et al. [34] 2022 China | Ultrasound | Electro-acupuncture (EA) combined with physical exercise compared to only physical exercise | 110 women: control group (n = 55) and EA group (n = 55). | EA intervention: 6 acupoints, with vertical acupuncture of 25–40 mm; Physical exercise: fascial abdominal breathing, supine head training, left and right-side leg rotation, and supine cycling. 2 weeks: the treatment was for 30 min once/day, five times a week |

Based on the difference between baseline and week 2 and 26 of IRD in both groups, both groups showed statistically significant reductions compared to before treatment (P < 0.05). At week 2, the EA group had a smaller mean IRD at the horizontal line of the umbilicus than the control group, but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05). As compared to the control group, the EA group had a significantly smaller mean IRD at the horizontal line of the umbilicus in head-up and flexed knee states (P < 0.05) at week 26. There were five (9.1 %) and thirteen (23.64 %) adverse events reported in the EA and control groups, respectively. | NA |

| Kim et al. [35] 2022 Korea |

Ultrasound | Online exercise intervention; a real-time video conferencing platform (ZOOM) | 37 women: the online (n = 19) and offline (n = 18) groups | 6 weeks:40 min trunk stabilization exercise sessions twice a week for six weeks | A significant improvement was observed in both groups in terms of inter-recti distance between the rectus abdominis, abdominal muscle thickness, and static trunk endurance, as well as maternal quality of life (all P < 0.001); In the offline group, improvements were more significant. Videoconferencing-based exercise interventions improved various parameters, including the interrecti distance, trunk stability, and the quality of life of the sufferers. It might be an alternate to face-to-face intervention for those postpartum women with DRA. | NA |

| Wei et al. [36] 2022 China |

Finger measurement and ultrasound | Electrical stimulation and strengthening exercises of oblique muscles | 32 women in two groups (n = 16 in each group): control group and the intervention group | Referred to the published protocols. 6 weeks: once a day, each lasting 5 s, followed by a 10-s rest; and repeating 20 times for each. |

After six weeks of intervention, both areas of the rectus abdominis muscle in the experimental group showed significant reductions in distance between the two blocks (above the umbilicus = 0.001 and below the umbilicus P = 0.03), while this distance in the control group did not had a significant change (P > 0.05). Also, During the intervention, there were significant differences between two groups in the distance between the rectus abdominis muscle blocks in the upper part of the umbilicus (P = 0.04). In women with rectal diastasis, electrical stimulation coupled with strengthening exercises of internal and external oblique muscles could reduce the condition and increase the thickness of these muscles. | Age, BMI, number of children |

| Yalfani et al. [37] 2022 Iran | Digital caliper | 1): STS group 2): ISoM-ISoT group 3): Control group |

36 women: three groups (n = 12 in each) | Both STS and ISoM-ISoT training programs in 24 sessions. 8 weeks: 3 sessions a week; exercises were performed for 50 min in 1 session. |

The results of the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) and minimal detectable change (MDC) suggested that the STS exercises outperformed ISoM-ISoT training regarding IRD, pain, disability, and proprioception, whereas ISoM-ISoT training had a better effect in lumbopelvic control and balance. | IRD, pain, disability, proprioception |

| Ramirez-Jimenez et al. [38] 2023 Spain | Stainless steel caliper | Therapeutic Exercise Interventions. | 12 women | Hypopressive exercise program: hypopressive breathing, axial auto-elongation, cervical elongation, forward displacement of the body's gravity axis, activation of the shoulder girdle, slight knee flexion, and ankle dorsiflexion. 4 weeks; The entire protocol lasted four consecutive weeks, three sessions per week (12 sessions in total), each of which lasted 30 min. |

A reduction in IRD was observed among participants (P < 0.05); some participants no longer showed AD following the intervention. A median of 2 cm of decrease in thoracic respiratory expansion was observed at follow-up, while the abdominal circumference increased primarily at follow-up. When assessed at 3 and 6 cm supraumbilical, the LA's tension and stiffness decreased. Finally, there was a decrease in tension and elasticity in TA/IO and the PF after the intervention, as well as a decrease in PF elasticity. | NA |

Note: DRA: Diastasis rectus abdominis; IRD: inter-rectus distance; STS: suspension training system; ISoM-ISoT: isometric-isotonic; PFM: pelvic floor muscle; HE: hypopressive exercises; AD: Abdominal diastasis; LA: linea alba; SR: standardized rehabilitation; non-SR: non-standardized rehabilitation group; BAPFMT: electromyographic-biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle training; NMES: neuromuscular electrical stimulation; ZOOM: a real-time video conferencing platform; VM: visceral manipulation; TrA: transversus abdominis.

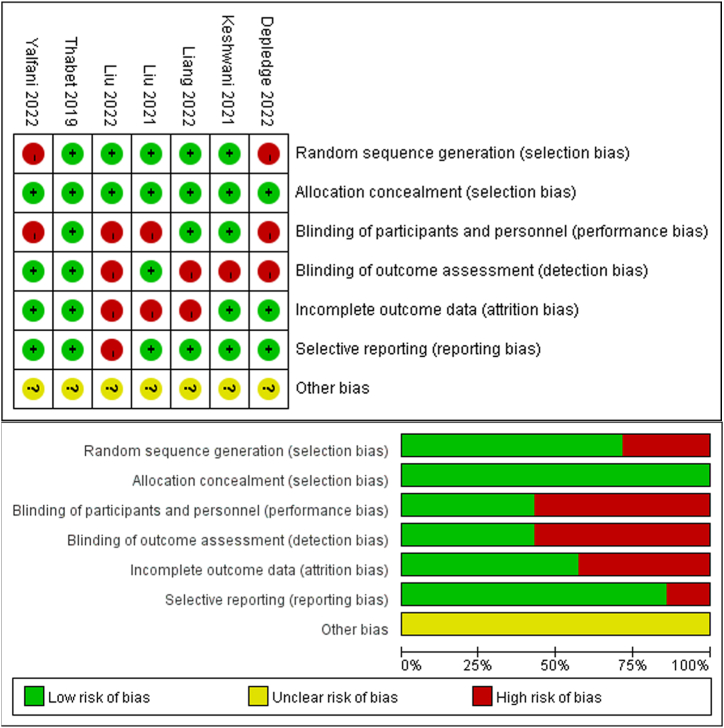

3.3. Study quality

The seven RCTs, except for Thabet et al.’s study, were assessed as low risk of bias, and the remaining six studies were assessed as high risk of bias overall (Fig. 2). According to the NOS, four studies were judged to be of moderate quality and the remaining five studies were of high quality. In all, 56 % (5/9) of the included studies were considered to have high methodological quality. Supplementary Table 2 showed a detailed scoring of the study quality.

Fig. 2.

Risk of bias in the study of RCT.

3.4. Brief summary of the 16 included studies

The majority of these studies revealed that postpartum DRA (other relevant biomechanical variables, i.e., the tension on the linea alba, abdominal function, trunk flexion strength, and abdominal muscle thickness) and its harmful consequences (i.e., quality of life, body image, urogynecological symptoms, and bowel symptoms) on the body could be improved by using an abdominal rehabilitation training program. Pelvic floor muscle exercise was shown to be ineffective in lowering the risk of DRA in one included study [28]. One study found that the use of Tubigrip and tape did not enhance the effectiveness of these exercises [32]. According to one piece of research, women's time wearing Tubigrip or a belt was not related to the percentage reduction in RA separation (P > 0.05) [25]. Another study concluded that urogynecological symptoms or overall function did not appear to be affected by any of the interventions [22]. According to the above evidence, it is still controversial with regard to the effects of these specific interventions among different included studies.

This scoping review analyzed sixteen studies containing several diverse designs that examined intervention strategies to prevent and/or improve DRA. Each study included specific kind of exercise as a treatment option, either on its own or in combination with instruction and/or external support clothing. According to the 16 included studies, rehabilitation programs, i.e., physical exercise, non-exercise physical therapy, acupuncture, and electrotherapy, could effectively protect against the onset (in the early postnatal period) and/or progression (DRA level turned to more severe) of DRA. These findings supported the earlier concept that highlighted the importance of testing for DRA after the childbearing year [39]. DRA's rehabilitation included an abdominal exercise program (to strengthen the transverse abdominis or rectus abdominis), methods to strengthen the transverse abdominis (functional training, pilates, Tupler technique exercises, with or without abdominal splints), posture training, noble technique (manual approach to the rectus abdominis during partial situps), education and training in proper mobility and lifting techniques, manipulative therapy (soft tissue mobilization, myofascial release), the Tubigrip or a corset.

4. Discussion

Since rehabilitations are a broad category of treatment, the discussion section was unfolded by specific rehabilitation methods for treating DRA with clinical details. The modalities of treatment mainly included physical exercise therapy, non-exercise physical therapy, neuromuscular electrical stimulation, and online intervention. The duration of rehabilitation treatment was varied among different included studies, between 2 and 36 weeks with a frequency of 3–5 times per week. The measuring techniques included finger width assessment, calipers, palpation, and ultrasonography. Online intervention is an emerging option for DRA treatment. Specific rehabilitation appeared to improve the quality of life of the sufferers, but more research will be necessary to confirm this finding.

4.1. Physical exercise therapy

Effective abdominal exercises are advised by therapists during pregnancy and postpartum. During the postpartum period, the aims of exercise was to reduce or improve IRD [14]. But until now, there hasn't been a universal therapeutic exercise regimen. The approach for a therapist's choice depends on the experience and results they have gained. The exercise training mentioned in the literature was based on the theory of the transversal and rectus abdominis muscles, which had the power to affect the LA, and might assist to prevent or minimize AD and speed up recovery [18]. In skeletal muscles, therapeutic exercise activated both slow (ST) and fast (FT) muscle fibers, and muscle strength rose as FT fiber concentration rose [40]. During exercise, adding core movement in addition to abdominal support can effectively treat and help turn off DRA, while also potentially reducing back discomfort caused by DRA. A recent study developed by Rastislav Dudič et al. [41] demonstrated that physical exercise might help to reduce the diastasis of the direct abdominal muscle in postpartum women. The objectification methods included activation of pelvic floor muscles, postural adjustment, and modification of breathing stereotype and quality. The recommended duration of exercise was 5 days per week, for 12 weeks. The dosage of exercise was 15 min per day, 20 min per day, and 30 min per day, in the 1st, 2–4 weeks of treatment, and 5–12 weeks of treatment, respectively. Intriguingly, Gluppe et al. [33] indicated that curl-up exercises (10 min per day, 5 days a week for 12 weeks) could not improve or worsen IRD (95 % CI: 1 to 4) but significantly increase abdominal muscle strength and thickness. Since the exercise programs could increase abdominal muscle strength and rectus abdominis thickness, parous women with mild to moderate DRA should not be discouraged from doing the exercises of head-lift, curl-up, and twisted curl-up.

However, we must take into consideration of the possibility that exercise could enhance IRD. It was because exercising during pregnancy keeps the linea alba less stressed by maintaining abdominal tone, strength, and control. Women who exercise throughout pregnancy typically exercise before being pregnant, so they might be fitter and had better-conditioned abdominal muscles than those who did not exercise while they were pregnant. Similar to this finding, the type of exercise implemented might be account for the decrease in DRA breadth and faster recovery of DRA seen with exercise [18].

4.2. Non-exercise physical therapy

Although other studies found that a supervised exercise program, including pelvic floor and abdominal strength training, did not reduce the prevalence of DRA [28]. The basic rehabilitation training included in the literature in this study was based on sports training. The study found that a supported abdominal exercise program could reduce DRA in the early postpartum period [42]. Non-exercise physical therapy includes abdominal adhesives, exercise tape, electrical stimulation, and manual therapy. Therapists frequently treat patients with exercise and abdominal binders from various techniques. The most popular method therapists employ to treat DRA is exercise. Keshwani et al. [22] conducted a pilot RCT to compare the effects of abdominal binding and exercise therapy on 32 primiparous women. Three groups of these women had abdominal binding, exercise therapy, or a combination of the two. After six months, abdominal binding alone and in combination with the other treatment produced favorable results. Thabet et al. [20]. used abdominal binding, and respiratory maneuvers in the group of Deep core train. And came to the same conclusion. The elastic tape serves as an adjunct to the means of a physical therapy program. It was suggested that physical therapy combined with tape (once a week) significantly reduced the IRD than that of minimal intervention (−1.28, 95 % CI: 1.60, −0.69) [19]. Of note, tape alone might have no remarkable therapeutic effect on DRA.

Manual therapy is also one of the rehabilitation programs for DRA. Visceral manipulation (VM), muscle energy technique, myofascial release, and trigger point release are the common methods of manual therapy.VM was recently introduced for the treatment of DRA for its characteristics of recreating, harmonizing, and increasing proprioceptive communication [43]. It is possible that VM helps to increase the flexibility along the parietal peritoneum, assisting that the parietal peritoneum and abdominal musculature to return to their normal resting position [43]. Three women who were diagnosed with DRA underwent a retrospective chart review by Kirk et al. All three patients had four VM treatments, and each one showed a reduction in IRD [43]. One case study used external support garments, such as Tubigrip and corsets, in addition to exercise to reduce DRA [25]. By simulating the transversus abdominis muscle's facial tension, external support garments might compress and support the abdominal and lumbopelvic region. They might ay also offer the transversus abdominis muscle biofeedback to help it become more active. In addition to transversus abdominis muscle workouts, these external supports might be employed, however, there was little data to support their usage in the treatment of DRA, necessitating additional research.

5. 3 neuromuscular electrical stimulation

Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), one of the common methods in rehabilitation medicine, is the application of electricity to cause muscle contraction. This conservative treatment was found to strengthen muscles and promote neurological rehabilitation in orthopedic treatment [34,27]. The principle of the NMES in treating DRA might be associated with the improvement of tissue excitability and adjustments of the mechanical balance of the postpartum abdominal muscle [26,36]. Besides, NMES can recruit deep muscle fibers at lower training intensities due to the stimulated nerves are distributed throughout the muscle [31]. In addition, electrical stimulation can induce the muscle contractions, activating a larger proportion of type II muscle fibers [30]. Electrical stimulation techniques have recently been used by therapists to help DRA patients with IRD. The concept of biofeedback-assisted pelvic floor muscle training (BAPFMT) is the application of surface electromyography (EMG) technology and intravaginal probe registration, which was commonly combined with biofeedback and illegal electromyography muscle activation [37]. The reason BAPFMT has gained popularity recently was that it enabled patients and therapists to monitor the proper PFM contraction, which facilitated neuromuscular learning or readjustment during the intervention. In the study of Liang et al. [24], patients in the study group underwent BAPFMT in addition to rectus abdominis neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES), while those in the control group only underwent rectus abdominis NMES. At six weeks, the IRD of the study group was significantly lower than that of the control group (1.6 ± 0.3 vs. 2.0 ± 0.3 cm, mean difference: 0.4, 95 % confidence interval: 0.59 to - 0.26). It demonstrated how BAPFMT could raise the quality of life and lower maternal IRD. Electrical stimulation of acupuncture needles could improve tissue excitability and regulated the mechanical balance of the postpartum abdominal muscle group [36,38]. Liu et al. [26] gave 55 women in DRA 10 times of Electro-acupuncture (EA) combined with physical exercise for 2 weeks. The results showed that this combined approach improved symptoms of IRD, body mass index (BMI), LA elasticity, paraumbilical subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT), and DRA, with lasting effects at 26 weeks. Kamel et al.'s study [44] confirmed that NMES helped to reduce IRD (MD = −0.65, 95 % CI: 0.85, −0.46) in postpartum women. If NMES was combined with abdominal exercises, the effect could be enhanced as compared to abdominal exercises only.

Wei et al. [45] also performed a comparative study on the topic of the roles of electrical muscle stimulation in treating DRA. After six weeks of intervention, the authors found that both areas of the rectus abdominis muscle in the experimental group showed significant reductions in distance between the two blocks (above the umbilicus = 0.001 and below the umbilicus P = 0.03), while this distance in the control group did not had a significant change (P > 0.05). During the intervention, there were significant differences between the two groups in the distance between the rectus abdominis muscle blocks in the upper part of the umbilicus (P = 0.04). The authors concluded that electrical stimulation coupled with strengthening exercises of internal and external oblique muscles could reduce the condition and increase the thickness of these muscles in women with rectal diastasis.

5.1. Time of rehabilitation intervention

The duration of the intervention is also one of the significant aspects impacting the effectiveness of rehabilitation efficacy. A case study of a visceral manipulation intervention was included in this study [20], in which protocol was limited although the quality of the method was good. For example, the intervention time was 18, 26, and 36 weeks in three independent cases, respectively. In other studies, the duration of intervention was between 2 weeks and 16 weeks, with the most frequent interventions at 4 weeks and 8 weeks. The intervention time of electroacupuncture was usually 2 weeks, and the frequency of increase was 5 times per week [21,26]. The rest of the rehabilitation training with an exercise intervention generally requires 3 training per week [20,23,44,46,47].

5.2. Measuring method (diagnostic and efficacy evaluation)

The measurement is carried out to detect the presence of DRA or to track the results of various treatment options for DRA. Researchers and practitioners applied a variety of measurement techniques in the literature. The measurement techniques included finger width assessment, calipers, and ultrasonography in addition to palpation, while magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computer tomography (CT) measurements could not be found in the literature. The most often employed assessment technique in clinical practice was abdominal palpation. Separation is most common in the umbilical cord. The IRD cut-off value of finger width, greater than or equal to 2 cm, was employed as the diagnostic criteria for DRA across investigations conducted in the literature [29]. In Gluppe et al.'s study [28], the interrectus muscle distance was palpated with finger width, and the cut-off point of separation was ≥2 finger widths. Measures were taken 4.5 cm above, at, and 4.5 cm below the umbilicus. DRA is diagnosed if the palpation separation along the white line is greater than 2 finger widths at the above 3 locations, or if there was a protrusion along the white line even if the palpation was <2 finger widths. According to the number of finger widths, they were classified as normal (<2), mild (2–3), moderate (3–4), and severe (≥4). However, the reliability of abdominal palpation has been debated. In this scoping review, there were four studies measured using digital nylon calipers. Rectal separation distance was measured at 4.5 cm above the umbilicus in 2 cases [20,23]. Laframboise et al. [46] used nylon digital calipers to determine the DRA width of white lines. The width of the DRA is measured in two stages: at the navel, 2 inches/4.5 cm above, and 2 inches/4.5 cm below. Ramirez-Jimenez et al. [47] measured the DRA through a digital 150 mm hardened stainless steel caliper (accuracy: ±1 mm), at four specific supraumbilical points (3, 6, 9, and 12 cm). In addition to DRA measurements, the abdominal muscle strength could be assessed by specific devices, such as Isokinetic (Biodex Multi-Joint System Pro, New York, NY, USA).

Studies, however, differed based on a number of factors, including the location of the test, the patient's position, and the job they had to do before the assessment [39,35,48]. Most studies have shown higher accuracy and effectiveness with imaging tools compared to palpation [5,48]. In recent years, ultrasound imaging has been increasingly applied to evaluate physiological and pathological muscle behavior due to its non-invasive, high precision, user-friendliness, and availability of commercial ultrasound scanners [49]. Therefore, ten included studies used ultrasonic measurement of IRD as a diagnostic method. A noninvasive imaging method called ultrasound imaging (USI) was used to see within the body's organs. According to European Hernia Society recommendations, ultrasound imaging should be used 3 cm above the umbilicus for a more accurate measurement [2]. In Liu et al.'s study [26], three measuring points were selected (midpoint between umbilicus and xiphoid process, midpoint between umbilicus and pubic symphysis at rest). Take the average of the three results of each group as the reference value. The distance between the inner margin of the rectus abdominis and the upper/lower umbilicus was measured by a B-ultrasound probe at an umbilical level by Hu et al. [50]. According to this evidence, there is still inconsistency in the location taken by B-ultrasound measurement. Due to the lack of a unified evaluation process, the results from each independent study are relatively random and inconsistent. In the future, a widely acknowledged and efficient measurement tool may be greatly assisted to diagnose DRA and evaluate the therapeutic efficacy of different rehabilitation training programs.

5.3. Online intervention

Since the current treatments were mostly designed for postpartum women (out of the hospital), many studies of physical training take place at home. Past activity, walking, and sitting were measured using a self-assessment questionnaire, and total times of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity were calculated. Two of the sixteen studies used online monitoring. According to Laframboise et al.'s study [46], this online survey does had unique advantages. Campaign interventions are "virtual" (online), which might be key to widespread dissemination. Moreover, the variety of postpartum months among participants (i.e., 6–24 months) indicated a wide spectrum of postpartum ages that might have benefitted clinically with this type of program. Kim et al. [51] conducted an exercise intervention in women with postpartum rectus abdominals dissociation on a real-time video conferencing platform. It was found that this method was effective in improving the trunk stability, distance between the rectum, and quality of life of postpartum women. It was suggested that there was a need to creat an appropriate environment for urging patients to frequently participate in exercise [52]. As a result, online exercise might help to improve health-related physical strength through regular exercise participation at home [51]. On the other hand, online interventions had the advantage of easily recruiting postpartum participants due to it was expediently conducted through an online community. However, could be an alternative to face-to-face intervention still merits further consideration. In today's fast pace of life, virtual intervention is worth considering in the rehabilitation training program for postpartum women with abdomenal dissociation. Therefore, a completely online exercise program may be an effective option for treating postpartum women with DRA.

5.4. Quality of life

DRA is a common prenatal and postpartum health problem that can cause a variety of health complications, e.g. lower back pain, decreased function, and reduced quality of life. The negative body image caused by these complications resulted in a subsequent poor quality of life. Hu et al. [50] investigated standardized rehabilitation (SR) and non-standardized rehabilitation (non-SR) interventions in 294 patients with DRA. SR is an independent factor affecting the prognosis of maternal DRA, which can improve the quality of life of parturients. This finding was consistent with Liang et al.’s study [24]. The two studies suggested that elevated IRD might be correlated to poorer postural control but better colorectal function in patients with DRA. Thabet et al. [20] demonstrated that the deep core stability exercise program (3 times per week, for 8 weeks) could significantly improve the quality of life of postpartum women. Nevertheless, IRD was also found to be not significantly correlated to abdominal muscle endurance, pelvic floor function, or respiratory muscle strength [53]. Therefore, the way we think about DRA needs to be rethought. More comprehensive assessments, such as objective measurements and biopsychosocial knowledge, are still warranted to guide further postpartum rehabilitation.

5.5. Limitations and Perspectives

Though the above findings were important in clinical practice, the design and quality of the included studies were variable, thus caution was required in interpreting and applying the results of this review. The format of investigations varied among the included studies (e.g., case studies, retrospective studies, RCTS). Intervention strategies and techniques vary as well. Because of this, the scoping review was unable to draw strong conclusions regarding which interventions were more effective. As described in summary, there is currently no universal rehabilitation training program for DRA that includes recommendations for exercise kind, dose, duration of interventions, etc. The method that therapists employ was determined by their experience and the outcomes they have attained. Despite studies showing a beneficial effect of exercise on DRA, the proof was scant. The rectus abdominis and/or transverse abdominis muscles were primarily targeted by the training techniques. Since there is no consensus regarding these techniques' efficacy in the literature, analyses of them are necessary.

Additionally, in terms of the review's secondary outcomes, core instability, and poor body image seem to be the most commonly reported symptoms. According to the literature, abdominal binding along with exercise therapy was linked to favorable, clinically significant benefits on both body image outcomes as well as trunk flexion strength [22]. Therefore, it is suggested that future studies should concentrate on core instability and body image, which may contribute to the development of specific interventions for the sufferers.

Currently, the key challenge in clinical practice is a subject for debate: “Is physiotherapy effective in treating DRA?” Commonly, DRA is prevalent in late pregnancy and declines during postpartum. However, DRA is constant and persistent in some postpartum women. Physiotherapeutic exercise training is recommended to be a first-line treatment for DRA, which may be attributed to it being an effective noninvasive treatment as compared to surgery. Many studies implied that abdominal exercise during pregnancy and postpartum could effectively prevent DRA. But some investigators indicated that rehabilitation training might be not more effective than no interventions when treating DRA. They even observed that exercises might increase the distortion of the linea alba in some cases. These varied results suggested that rehabilitation training played an essential role in restoring the tension of the linea alba rather than reducing the IRD. As a result, further research is still warranted to find an optimal strategy for treating DRA, in both functional and cosmetic aspects.

6. Conclusion

Based on the above evidence, it is currently controversial whether women with postpartum DRA can benefit from specific exercise regimens, but rehabilitation training can effectively improve postpartum inter-rectus distance in these sufferers. In the near future, high-quality prospective randomized controlled trials targeting specific non-surgical management strategies are still warranted to validate the exact roles of rehabilitation training in treating DRA.

Funding statement

This work was supported by the grants from Hangzhou Agricultural and Social Development Research Guidance Project (Hangzhou Bureau of Science and Technology, No. 20220919Y027, for Beibei Chen) and the Science and Technology Planning Project of Taizhou City, Zhejiang Province (ID: 23ywb34, for Yan Hu)..

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Beibei Chen: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Xiumin Zhao: Formal analysis, Data curation. Yan Hu: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Not Applicable.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e20956.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Akram J., Matzen S.H. Rectus abdominis diastasis. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2014;48:163–169. doi: 10.3109/2000656X.2013.859145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hernandez-Granados P., Henriksen N.A., Berrevoet F., Cuccurullo D., Lopez-Cano M., Nienhuijs S., Ross D., Montgomery A. European Hernia Society guidelines on management of rectus diastasis. Br. J. Surg. 2021;108:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znab128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperstad J.B., Tennfjord M.K., Hilde G., Ellstrom-Engh M., Bo K. Diastasis recti abdominis during pregnancy and 12 months after childbirth: prevalence, risk factors and report of lumbopelvic pain. Br. J. Sports Med. 2016;50:1092–1096. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandes D.M.P., Pascoal A.G., Carita A.I., Bo K. Prevalence and risk factors of diastasis recti abdominis from late pregnancy to 6 months postpartum, and relationship with lumbo-pelvic pain. Man. Ther. 2015;20:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liaw L.J., Hsu M.J., Liao C.F., Liu M.F., Hsu A.T. The relationships between inter-recti distance measured by ultrasound imaging and abdominal muscle function in postpartum women: a 6-month follow-up study. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2011;41:435–443. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2011.3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee D.G., Lee L.J., McLaughlin L. Stability, continence and breathing: the role of fascia following pregnancy and delivery. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2008;12:333–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilleard W.L., Brown J.M. Structure and function of the abdominal muscles in primigravid subjects during pregnancy and the immediate postbirth period. Phys. Ther. 1996;76:750–762. doi: 10.1093/ptj/76.7.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keshwani N., Mathur S., McLean L. Relationship between interrectus distance and symptom severity in women with diastasis recti abdominis in the early postpartum period. Phys. Ther. 2018;98:182–190. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzx117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Starzec-Proserpio M., Lipa D., Szymanski J., Szymanska A., Kajdy A., Baranowska B. Association among pelvic girdle pain, diastasis recti abdominis, pubic symphysis width, and pain catastrophizing: a matched case-control study. Phys. Ther. 2022;102 doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzab311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gluppe S.B., Engh M.E., Bo K. Immediate effect of abdominal and pelvic floor muscle exercises on interrecti distance in women with diastasis recti abdominis who were parous. Phys. Ther. 2020;100:1372–1383. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzaa070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Temel M., Turkmen A., Berberoglu O. Improvements in vertebral-column angles and psychological metrics after abdominoplasty with rectus plication. Aesthet Surg J. 2016;36:577–587. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjv257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claus C., Malcher F., Cavazzola L.T., Furtado M., Morrell A., Azevedo M., Meirelles L.G., Santos H., Garcia R. Subcutaneous onlay laparoscopic approach (scola) for ventral hernia and rectus abdominis diastasis repair: technical description and initial results. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2018;31:e1399. doi: 10.1590/0102-672020180001e1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nahas F.X., Ferreira L.M., Mendes J.A. An efficient way to correct recurrent rectus diastasis. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2004;28:189–196. doi: 10.1007/s00266-003-0097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Radhakrishnan M., Ramamurthy K. Efficacy and challenges in the treatment of diastasis recti abdominis-A scoping review on the current trends and future perspectives. Diagnostics. 2022;12 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12092044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keshwani N., McLean L. Ultrasound imaging in postpartum women with diastasis recti: intrarater between-session reliability. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015;45:713–718. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2015.5879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheppard S. The role of transversus abdominus in post partum correction of gross divarication recti. Man. Ther. 1996;1:214–216. doi: 10.1054/math.1996.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernandez-Granados P., Henriksen N.A., Berrevoet F., Cuccurullo D., Lopez-Cano M., Nienhuijs S., Ross D., Montgomery A. European Hernia Society guidelines on management of rectus diastasis. Br. J. Surg. 2021;108:1189–1191. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znab128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benjamin D.R., van de Water A.T., Peiris C.L. Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2014;100:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gluppe S., Engh M.E., Bo K. What is the evidence for abdominal and pelvic floor muscle training to treat diastasis recti abdominis postpartum? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2021;25:664–675. doi: 10.1016/j.bjpt.2021.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thabet A.A., Alshehri M.A. Efficacy of deep core stability exercise program in postpartum women with diastasis recti abdominis: a randomised controlled trial. J. Musculoskelet. Neuronal Interact. 2019;19:62–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y., Zhu Y., Jiang L., Lu C., Xiao L., Chen J., Wang T., Deng L., Zhang H., Shi Y., Zheng T., Feng M., Ye T., Wang J. Efficacy of acupuncture in post-partum with diastasis recti abdominis: a randomized controlled clinical trial study protocol. Front. Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.722572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keshwani N., Mathur S., McLean L. The impact of exercise therapy and abdominal binding in the management of diastasis recti abdominis in the early post-partum period: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2021;37:1018–1033. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2019.1675207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yalfani A., Bigdeli N., Gandomi F. Comparing the effects of suspension and isometric-isotonic training on postural stability, lumbopelvic control, and proprioception in women with diastasis recti abdominis: a randomized, single-blinded, controlled trial. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2022:1–13. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2022.2100300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liang P., Liang M., Shi S., Liu Y., Xiong R. Rehabilitation programme including EMG-biofeedback- assisted pelvic floor muscle training for rectus diastasis after childbirth: a randomised controlled trial. Physiotherapy. 2022;117:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2022.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Depledge J., McNair P., Ellis R. The effect of Tubigrip and a rigid belt on rectus abdominus diastasis immediately postpartum_ A randomised clinical trial. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2022.102712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y., Zhu Y., Jiang L., Lu C., Xiao L., Wang T., Chen J., Sun L., Deng L., Gu M., Zheng T., Feng M., Shi Y. Efficacy of electro-acupuncture in postpartum with diastasis recti abdominis: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Front. Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.1003361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yun G.J., Chun M.H., Park J.Y., Kim B.R. The synergic effects of mirror therapy and neuromuscular electrical stimulation for hand function in stroke patients. Ann Rehabil Med. 2011;35:316–321. doi: 10.5535/arm.2011.35.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gluppe S.L., Hilde G., Tennfjord M.K., Engh M.E., Bo K. Effect of a postpartum training program on the prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in postpartum primiparous women: a randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. 2018;98:260–268. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzy008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q., Yu X., Chen G., Sun X., Wang J. Does diastasis recti abdominis weaken pelvic floor function? A cross-sectional study. Int Urogynecol J. 2020;31:277–283. doi: 10.1007/s00192-019-04005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sinacore D.R., Delitto A., King D.S., Rose S.J. Type II fiber activation with electrical stimulation: a preliminary report. Phys. Ther. 1990;70:416–422. doi: 10.1093/ptj/70.7.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevens-Lapsley J.E., Balter J.E., Wolfe P., Eckhoff D.G., Kohrt W.M. Early neuromuscular electrical stimulation to improve quadriceps muscle strength after total knee arthroplasty: a randomized controlled trial. Phys. Ther. 2012;92:210–226. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20110124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Depledge J., McNair P., Ellis R. Exercises, Tubigrip and taping: can they reduce rectus abdominis diastasis measured three weeks post-partum? Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2021;53 doi: 10.1016/j.msksp.2021.102381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gluppe S.B., Ellstrom E.M., Bo K. Curl-up exercises improve abdominal muscle strength without worsening inter-recti distance in women with diastasis recti abdominis postpartum: a randomised controlled trial. J. Physiother. 2023;69:160–167. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2023.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walls R.J., McHugh G., O'Gorman D.J., Moyna N.M., O'Byrne J.M. Effects of preoperative neuromuscular electrical stimulation on quadriceps strength and functional recovery in total knee arthroplasty. A pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2010;11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bursch S.G. Interrater reliability of diastasis recti abdominis measurement. Phys. Ther. 1987;67:1077–1079. doi: 10.1093/ptj/67.7.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langevin H.M., Schnyer R., MacPherson H., Davis R., Harris R.E., Napadow V., Wayne P.M., Milley R.J., Lao L., Stener-Victorin E., Kong J.T., Hammerschlag R. Manual and electrical needle stimulation in acupuncture research: pitfalls and challenges of heterogeneity. J Altern Complement Med. 2015;21:113–128. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Voorham J.C., De Wachter S., Van den Bos T., Putter H., Lycklama A.N.G., Voorham-van D.Z.P. The effect of EMG biofeedback assisted pelvic floor muscle therapy on symptoms of the overactive bladder syndrome in women: a randomized controlled trial. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2017;36:1796–1803. doi: 10.1002/nau.23180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi X.H., Wang Y.K., Li T., Liu H.Y., Wang X.T., Wang Z.H., Mang J., Xu Z.X. Gender-related difference in altered fractional amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations after electroacupuncture on primary insomnia patients: a resting-state fMRI study. Brain Behav. 2021;11 doi: 10.1002/brb3.1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boissonnault J.S., Blaschak M.J. Incidence of diastasis recti abdominis during the childbearing year. Phys. Ther. 1988;68:1082–1086. doi: 10.1093/ptj/68.7.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Snijders T., Verdijk L.B., Beelen M., McKay B.R., Parise G., Kadi F., van Loon L.J. A single bout of exercise activates skeletal muscle satellite cells during subsequent overnight recovery. Exp. Physiol. 2012;97:762–773. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2011.063313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dudic R., Vaska E. Physiotherapy in a patient with diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle after childbirth. Ceska Gynekol. 2023;88:180–185. doi: 10.48095/cccg2023180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spitznagle T.M., Leong F.C., Van Dillen L.R. Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in a urogynecological patient population. Int. UrogynEcol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:321–328. doi: 10.1007/s00192-006-0143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kirk B., Elliott-Burke T. The effect of visceral manipulation on Diastasis Recti Abdominis (DRA): a case series. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2021;26:471–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kamel D.M., Yousif A.M. Neuromuscular electrical stimulation and strength recovery of postnatal diastasis recti abdominis muscles. Ann Rehabil Med. 2017;41:465–474. doi: 10.5535/arm.2017.41.3.465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei R., Yu F., Ju H., Jiang Q. Effect of electrical stimulation followed by exercises in postnatal diastasis recti abdominis via MMP2 gene expression. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2022;67:82–88. doi: 10.14715/cmb/2021.67.5.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laframboise F.C., Schlaff R.A., Baruth M. Postpartum exercise intervention targeting diastasis recti abdominis. Int J Exerc Sci. 2021;14:400–409. doi: 10.70252/GARZ3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramirez-Jimenez M., Alburquerque-Sendin F., Garrido-Castro J.L., Rodrigues-de-Souza D. Effects of hypopressive exercises on post-partum abdominal diastasis, trunk circumference, and mechanical properties of abdominopelvic tissues: a case series. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2023;39:49–60. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2021.2004630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mota P., Pascoal A.G., Sancho F., Carita A.I., Bo K. Reliability of the inter-rectus distance measured by palpation. Comparison of palpation and ultrasound measurements. Man. Ther. 2013;18:294–298. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.He K., Zhou X., Zhu Y., Wang B., Fu X., Yao Q., Chen H., Wang X. Muscle elasticity is different in individuals with diastasis recti abdominis than healthy volunteers. Insights Imaging. 2021;12:87. doi: 10.1186/s13244-021-01021-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu J., Gu J., Yu Z., Yang X., Fan J., You L., Hua Q., Zhao Y., Yan Y., Bai W., Xu Z., You L., Chen C. Efficacy of standardized rehabilitation in the treatment of diastasis rectus abdominis in postpartum women. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021;14:10373–10383. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S348135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim S., Yi D., Yim J. The effect of core exercise using online videoconferencing platform and offline-based intervention in postpartum woman with diastasis recti abdominis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19 doi: 10.3390/ijerph19127031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aarts H., Paulussen T., Schaalma H. Physical exercise habit: on the conceptualization and formation of habitual health behaviours. Health Educ. Res. 1997;12:363–374. doi: 10.1093/her/12.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Denizoglu K.H., Gurses H.N. Relationship between inter-recti distance, abdominal muscle endurance, pelvic floor functions, respiratory muscle strength, and postural control in women with diastasis recti abdominis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2022;279:40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2022.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.