Abstract

In cancer patients, dendritic cells (DCs) in tumor-draining lymph nodes can present antigens to naive T cells in ways that break immunological tolerance. The clonally expanded progeny of primed T cells are further regulated by DCs at tumor sites. Intra-tumoral DCs can both provide survival signals to and drive effector differentiation of incoming T cells, thereby locally enhancing antitumor immunity; however, the paucity of intra-tumoral DCs or their expression of immunoregulatory molecules often limits anti-tumor T cell responses. Here we review the current understanding of DC-T cell interactions at both priming and effector sites of immune responses. We place emerging insights into DC functions in tumor immunity in the context of DC development, ontogeny, and functions in other settings, and propose that DCs control at least two T-cell-associated checkpoints of the cancer immunity cycle. Our understanding of both checkpoints has implications for the development of new approaches to cancer immunotherapy.

eTOC blurb

Pittet and colleagues review the current knowledge of DC-T cell interactions at both priming and effector sites of immune responses, and discuss how insights from DC development, ontogeny and function in various settings inform our understanding of anti-tumor immunity and cancer immunotherapy.

Introduction

Tumor antigenicity is largely determined by non-synonymous mutations, aberrant protein expression and/or post-translational modifications in tumor cells1,2. These alterations result in the formation of peptide:MHC complexes recognizable as non-self-derived by T cells. While features such as tumor mutational burden (TMB) and neoantigen content can factor into overall checkpoint immunotherapy response3 4, antigenic content alone does not explain differences in T cell inflamed “hot” and T-cell non-inflamed “cold” tumors5. Rather, tumor T cell inflammation is better correlated with dendritic cell (DC) gene signatures6–8, suggesting that antigen processing and presentation are key bottlenecks of tumor immune recognition.

At the time of the original incarnation of the Cancer Immunity Cycle 10 years ago9, most knowledge of T cell:DC interactions was derived from studies of antigenic priming in lymph nodes (LNs) in experimental mouse models based on sterile or infectious antigens. On the assumption that the biology of T-cell responses in these settings is recapitulated in cancer, the Cancer Immunity Cycle emphasized the interplay between DCs and T cells at priming sites. This model has been incredibly fruitful in shaping our concept of the tumor-immune system interactions and responses to immunotherapy. However, an important insight only recently gained is that T:DC interactions do not only govern T-cell priming in the LN. Rather, we now know that T:DC interactions are critical throughout the Cancer Immunity Cycle, including key reactions within the tumor microenvironment that promote anti-tumor effector responses. A growing body of evidence supports the concept that mutualism between DCs and T-cells, based on reciprocal signals exchanged during physical interactions, is essential for tumor control and successful cancer immunotherapy. Although DCs are not known to have direct antitumor activity, they nonetheless shepherd tumor control through a mutualistic relationship with T cells. In other words, DCs are the “best supporting actors” of antitumor immunity.

Here we review the involvement of DCs in antitumor immunity. We first discuss DC ontogeny, activation, and trafficking patterns, as well as their role in Tcell activation in lymph nodes (LNs) in the context of health and homeostasis, where DCs are best understood, but with references to the cancer context wherever this has been explored. We then examine how the memory and effector progeny of naive tumor-specific T cells continue to be shaped by DCs once they enter the tumor microenvironment (TME) and discuss the various ways in which tumors can evade immunity by blocking DC function. Finally, we present a roadmap for next-generation immunotherapeutic approaches, which must be able to activate tumor-associated DCs to enable effective cancer control in more patients.

DC ontogeny, subsets and states, and migration routes

Since their discovery in mice some 50 years ago as a distinct cell type in secondary lymphoid organs10, DCs have been of interest to immunologists because of their capacity to act as sentinels of the immune system by sampling and storing soluble and cell-associated antigens, while at the same time assessing their tissue environment for indicators of cell stress or the presence of microbes. DCs then present antigenic peptides to T-cells expressing cognate T-cell receptors (TCRs) and, after integrating the information received about the tissue state, produce cytokines as well as co-stimulatory and/or co-inhibitory cues that collectively control the quality and quantity of T-cells produced. As a result, DCs can promote tolerance or, alternatively, stimulate different types of T-cell responses associated with so-called type-I immunity (e.g. against viruses and intracellular bacteria), type-II immunity (e.g. against parasites), or type-III immunity (e.g. against extracellular bacteria and fungi). How dendritic cells shape T cell responses in these settings has been discussed elsewhere and the reader is referred to these review articles11,12.

DCs can also limit tumor growth, for example by stimulating CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells that recognize tumor-derived neo-antigens. Ontogenic studies and, more recently, transcriptomic analyses have identified several DC subsets and states that are well conserved between mouse and human, between tissues, and between cancer types13. The cell subsets that likely best match the originally discovered DCs are the so-called classical or conventional cDC1s and cDC2s, which can be found not only in secondary lymphoid organs, such as tumor-draining lymph nodes (tdLNs), but also at tumor sites. These cells are the main focus of this review, and we will only briefly touch upon the potential roles of monocyte-derived DCs (MoDCs), which can adopt some phenotypic and functional features of cDCs14, and interferon-producing cells (IPCs) often also referred to as plasmacytoid DCs.

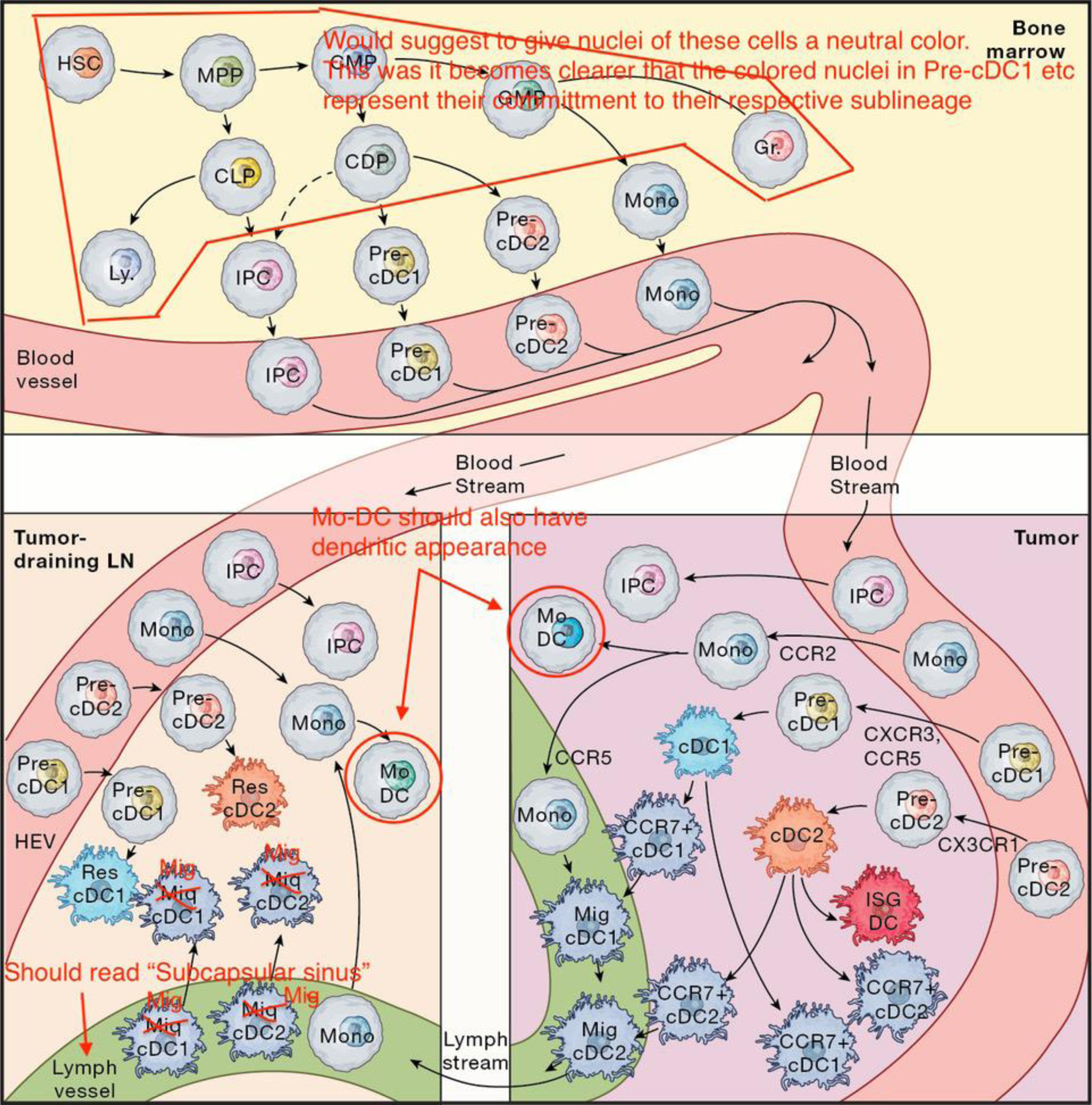

Both cDC1s and cDC2s develop in response to Flt3L from common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) which, via common DC precursors (CDPs), give rise to pre-cDC1s and pre-cDC2s (Figure 1). Pre-cDCs leave the bone marrow and traffic via the bloodstream to lymphoid and healthy non-lymphoid tissues, where, in mice, they undergo limited proliferative expansion and complete their development into fully differentiated cDCs15–17. In humans, fully differentiated cDC1s and cDC2s are also found in peripheral blood13,18, but it remains unclear if these cells have re-entered the bloodstream after completing their development in tissue, or if human cDCs can already complete their development in the bone marrow before trafficking to tissues via the bloodstream.

Figure 1. Cellular origins of tumor and lymph node DCs.

DCs are derived from myeloid progenitor cells in the bone marrow that traffic through blood to tumors and lymph nodes. In tumors they can adopt activated cell states such as CCR7+ DCs or interferon stimulated gene (ISG) DCs. CCR7+ DCs can either cluster around blood vessels to interact with blood extravasating T-cells, or move to lymphatics and become migratory DCs that traffic antigens to draining lymph nodes. Upon entering lymph nodes, migratory DCs initiate T-cell responses by priming naïve T-cells; setting off a complex interplay of antigen handoff to lymph node-resident DCs, and coordination of both cDC1 and cDC2 responses for successful antitumor immunity. HSC: hematopoietic stem cell; MPP: multipotent progenitor; CLP: common lymphoid progenitor; Ly: lymphocyte; IPC: interferon-producing cell; CMP: common myeloid progenitor; GMP: granulocyte monocyte progenitor; Gr: granulocyte; CDP: common dendritic progenitor; Mono: monocyte; MoDC: monocyte derived DC; migDC: migratory DC; resDC: resident DC; HEV: high endothelial venule.

Circulating pre-cDCs can migrate to lymphoid tissue to form so-called resident cDCs19. Alternatively, they may, like monocytes, traffic to non-lymphoid tissues, both at steady-state and, at an enhanced rate, during inflammation15–17. Here pre-cDCs complete development during their final rounds of cell division. Whereas fully differentiated cDC1s are fairly homogenous, cDC2s can be further subdivided, for instance based on expression of CD301b20 or other marker genes21,22. At present, however, there is insufficient evidence to distinguish whether cDC2 heterogeneity reflects distinct states (e.g., activation status) or subsets of cells with distinct ontogenies. Some cDCs eventually traffic to the draining LNs via lymphatic vessels as migratory cDCs. In LNs, they cooperate with resident cDCs in priming T-cells, as detailed later.

Circulating monocytes can give rise to either macrophages or MoDCs once recruited to non-lymphoid tissues, including solid tumors. This recruitment depends primarily on the chemokine receptor CCR223, followed by CCR6 for specific localization of MoDCs to epithelial compartments of certain tissues24,25. The signals that guide pre-cDC migration to tissues are less well understood. In mice, pre-cDC1s exhibit higher expression of CCR5 and CXCR3, whereas CX3CR1 is highly expressed by pre-cDC2s26. There is reduced accumulation of CXCR3-deficient cDC1s in melanoma tissue, but not in healthy skin or tdLNs, suggesting a role for CXCR3 in pre-cDC1 trafficking to the TME or, alternatively, in cDC1 survival and proliferation. Cancer cell expression of the CCR5 ligand CCL4 supports cDC1 recruitment to melanoma7. However, much remains to be learned about the factors that recruit pre-cDCs to healthy and tumor tissues.

While positioned in non-lymphoid tissues, cDCs use different scavenger receptors to sample cell-free or cell-associated antigens, including CD205 (DEC-205), CD209 (DC-SIGN), or CLEC9A (DNGR1). The latter receptor may be of particular interest for antitumor immunity; it binds to actin filaments released from dead cells, and thus also to actin-associated proteins, which potentially include mutational neoantigens in cancer cells. In addition to its role in cargo uptake, CLEC9A can activate SYK signals that promote phagosome rupture in cDC1s, allowing release of phagocytosed antigenic cargo into the cytosol to promote the cross-presentation of exogenous cell-associated antigens on MHC I proteins to CD8+ T-cells27.

Concomitant with antigen sampling, cDCs can be exposed to pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs and DAMPs) as well as inflammatory cytokines. These cues activate a migratory program that promotes CCR7-mediated cDC egress into lymphatic vessels and trafficking to draining LNs. The same cues can also increase cDC presentation of captured antigens on MHC I and II proteins, as well as the expression of the above-mentioned co-stimulatory factors and cytokines that regulate T-cell activation and differentiation. Although these different activation programs have traditionally been viewed as linked (and broadly referred to as “DC maturation”), it appears that the abilities of cDCs to activate T-cells and to migrate to draining LNs are at least to some extent controlled separately. For example, cDCs in inflamed tissues or tumors can show signs of exposure to type I or II IFNs (for example characterized by expression of Isg15 or Cxcl9) without activating their migratory program (characterized by expression of Fascin1 and Ccr7)28–30 31 32.

Interestingly, not all CCR7+ cDCs in tumors migrate to draining LNs. Instead, some of these cells densely accumulate around stromal blood vessels, where they interact with extravasating T-cells33. Intratumoral CCR7+ cDCs, which were initially described as DC3s34 35, and later as LAMP3+ DCs and mregDCs29,33,35,36, can likely derive from cDC1s or cDC2s36. A direct comparison of intratumoral DCs identified across different studies revealed that DC3s, LAMP3+ DCs and mregDCs are all transcriptionally similar and should therefore correspond to the same cell state13, referred to here as CCR7+ DCs.

Irrespective of the fact that some CCR7-expressing DCs can be retained in the TME, expression of this chemokine receptor allows some intratumoral cDC1s and cDC2s to sense CCL21 gradients generated by lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs), thereby promoting cDC entry into lymphatic vessels and migration to tdLNs37. Both subsets of cDCs carry cancer cell-expressed antigens to tdLNs20 where can either present these antigens directly to T-cells or pass them on to other cells, including resident cDC subsets (Figure 1)38. Monocytes do not express CCR7 but may use CCR5 to migrate from tissues to LNs. In a mouse model of lung inflammation, CCR5 expression by monocytes enabled these cells to follow CCL5-secreting migratory cDCs en route to draining LNs, where they give rise to MoDCs39. Because tumor-associated migratory cDCs express CCL533, they may also pave the way for tumor-infiltrating monocytes to form MoDCs in tdLNs.

During skin inflammation, CXCR4 can guide the migration of dermal DCs to draining LNs40. CXCR4 can also be used by T-cells to sense LEC-produced CXCL12 and migrate from tumors to tdLNs41; thus, it is plausible that this chemokine axis also facilitates the migration of intratumoral monocytes or DCs to tdLNs. In the context of allergic inflammation, dermal CD301b+ cDC2s only weakly upregulate CCR7 and require the synergistic effects of CCR8 to exit the subcapsular sinus of draining LNs to reach the interfollicular cortex42. However, the roles of both CXCR4 and CCR8 in DC migration from the TME to tdLNs need further exploration.

Besides cDCs, other DC subsets that populate the TME include MoDCs and IPCs. MoDCs arise at steady-state, but especially during inflammatory responses; they are derived from circulating monocytes, which themselves originate from CMPs via granulocyte-macrophage progenitors (GMPs) in response to macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF)43 (Figure 1). Despite their distinct ontogenies, MoDCs and CD301b+ cDC2s can adopt similar transcriptional states in mouse tdLNs20. Similarly, a meta-analysis of DC states in human tumors showed that MoDCs and some cDC2s have similar transcriptomes13. Yet, whether the phenotypic similarity of these cDC2s and MoDCs translates into functional redundancy remains to be fully defined. Also, the overall role of MoDCs in T-cell activation in the cancer context requires study.

IPCs are a heterogeneous subset of cells, which can derive from CDPs or, more commonly, from B-cell-biased common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) (Figure 1)44. IPCs can produce large amounts of type-I interferons (IFN-I)45, for example in response to TLR7 and TLR9 ligands produced during viral infections. They can also (cross-)present soluble antigens to T-cells in vitro, but their importance for antigen presentation in vivo remains a matter of debate46,47. IPC-derived IFN-I can help activate cDCs in LNs during viral infection48. In this way, IPCs may also play a role in antitumor immunity, although immune-regulatory factors in the TME may subdue their IFN-I expression49.

Coordinated T-cell priming by DC subsets

Once lymph-borne migratory cDCs arrive in the draining LNs, they penetrate the floor of the subcapsular sinus and migrate via interfollicular areas to the superficial and deep LN cortex, which are rich in the CCR7-ligands CCL19 and CCL2150. These regions are continually surveyed by motile naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells that enter LNs from the bloodstream via high endothelial venules. T-cells use the LN stromal cell network as a guidance scaffold to efficiently scan cDCs for cognate peptide-MHC ligands through short-lived, dynamic interactions. If they recognize a peptide-MHC complex with sufficiently high avidity in the context of the co-stimulatory proteins CD80 and CD86, TCR- and CD28-dependent signals not only induce a transcriptional response, but also trigger a transition to more long-lived and stable adhesive contacts with DCs. T cell:DC contact stability promotes sustained co-localization and the efficient reciprocal exchange of cytokine signals (e.g. via IL-12 and IFN-γ) that are also required for the initiation of full-fledged effector T-cell responses. This paradigm was initially established in experimental mouse models that relied on the injection of purified, fluorescently labeled DCs and T-cells to visualize their antigen-dependent clustering in LNs51 and was subsequently extended by dynamic imaging studies first in explanted intact LNs52–54 and later in vivo using intravital microscopy55–57. Collectively, these studies illuminated how the microanatomical organization of LNs guides the migration of DCs and T-cells in ways that maximize the likelihood that a rare antigen-specific T-cell will come in physical contact with DCs presenting their cognate antigen. The pace at which short-lived antigen-independent T-cell-DC contacts transition into stable, longer-lasting interactions following initial antigen recognition depends on the avidity of the peptide/MHC:TCR interaction56,58–60 and formation of stable contacts correlates with the induction of T-cell immunity while unstable contacts are associated with immunological tolerance61–63.

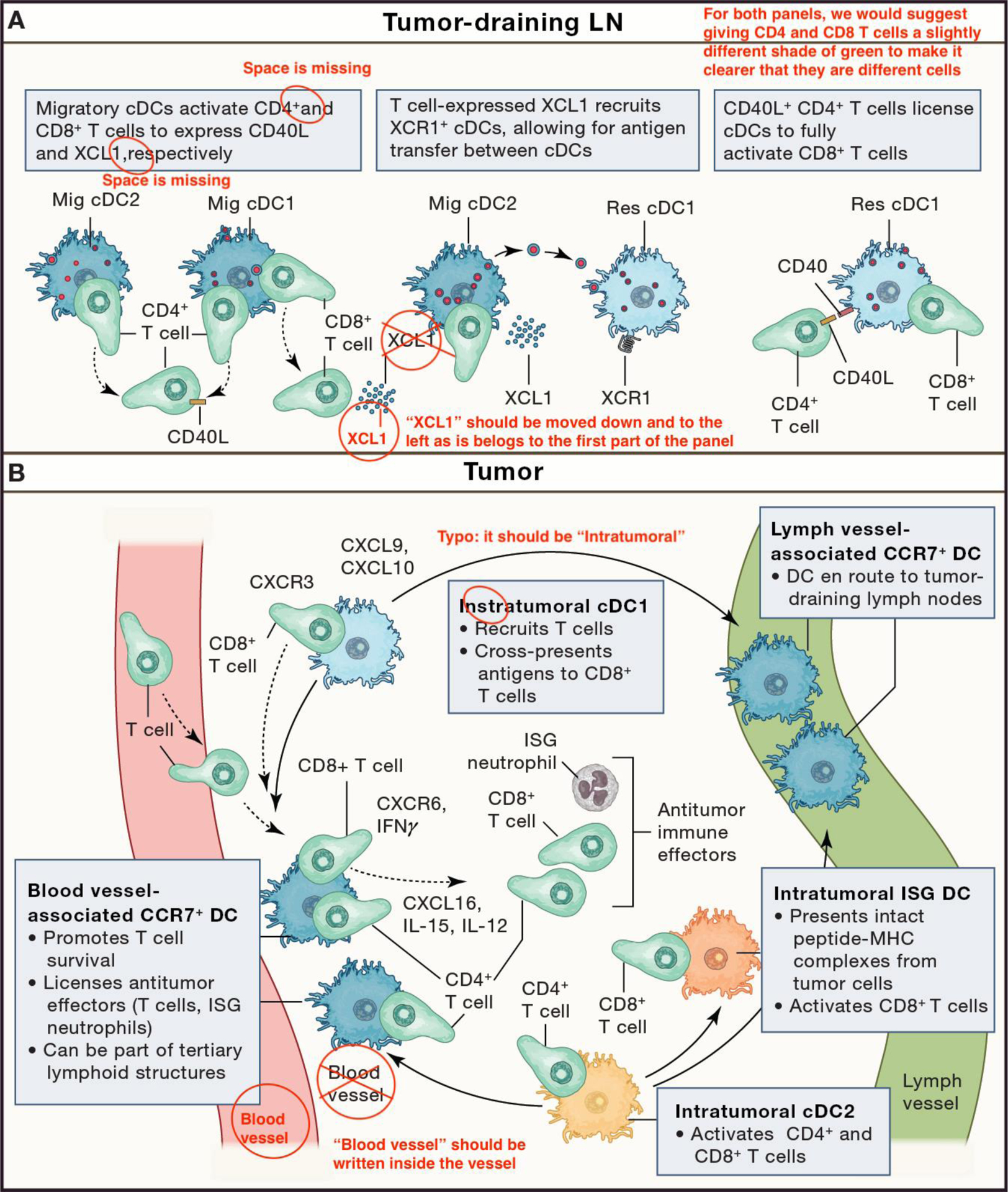

Following the identification of migratory and LN-resident cDC subsets, their division of labor and their cooperativity during the priming of T-cell responses was first appreciated with the observation that early presentation of lymph-borne free antigen by resident DCs can initiate T-cell activation, but that migratory DCs are required to induce fully functional T-cell responses64. Furthermore, resident cDC1s and cDC2s can independently activate CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells in response to lymph-borne free antigen, owing to cDC1 and cDC2 positioning in the deep and superficial paracortex, respectively65. Subsequent studies, building on the availability of reporter mouse strains to identify DC subsets and of genetic models to delete them, confirmed that optimal CD8+ T-cell activation depends on antigen presentation by both migratory cDC1s and cDC2s, in part due to the requirement for CD4+ T-cells to activate cDCs and enhance their priming capacity for CD8+ T-cells (‘T-cell help’) (Figure 2A). A model emerged whereby CD4+ T-cells are at first preferentially activated by migratory cDC2s, whereas CD8+ T-cells are activated by antigen cross-presenting migratory cDC1s (or, in certain infectious settings, by infected cDC1s). Initially activated CD8+ T-cells secrete the chemokine XCL1, which attracts additional XCR1-expressing cDC1s, including LN-resident cDC1s. Migratory DCs can then transfer antigen to nearby resident cDC1s, expanding the number and diversity of cDCs that participate in T-cell activation. Initially activated CD4+ T cells, meanwhile, start to express CD40L and provide ‘help’ to CD40+ cDC1s to license them for optimal priming of CD8+ T-cells, leading to robust effector and memory differentiation66–68.

Figure 2. Licensing of T-cell immunity by DCs in draining lymph nodes and tumors.

(A) Lymph Node: Migratory DCs interact with T-cells upon entering the lymph node from tumor-draining lymphatics. These interactions coordinate CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses and provide the basis for CD4+ T-cell “help”, such as through CD40L:CD40 stimulation, for CD8+ T-cell immune responses. T-cell-derived XCL1 can trigger recruitment of lymph node-resident cDC1s, enabling antigen transfer between migratory and resident DCs. CD4+ T-cell-“helped” DCs are fully licensed to robustly activate CD8+ T-cells. (B) Tumor: Intratumoral cDC1s (light blue) and cDC2s (orange) can profoundly influence the fate of incoming CD8+ and CD4+ T-cells and have distinct fates. For instance, some activated cDC1s and cDC2s can migrate via lymphatic vessels to tumor-draining lymph nodes, where they also contribute to T-cell responses. Other activated cDC1s and cDC2s remain in the tumor, where they can for example accumulate in perivascular niches near post-capillary venules of the tumor stroma and provide effector and survival signals to incoming T-cells. Some activated cDC2s can also acquire an interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) phenotype capable of activating CD8+ T-cells. The inserts illustrate some of the main functions ascribed to intratumoral cDCs. Key T-cell-derived immune signals (CXCR6, CXCR3, IFN-g), respond to and potentiate DC-derived signals (CXCL16, CXCL9, CXCL10, IL-12, and IL-15), resulting in the mutualistic support of T:DC interactions and sustained antitumor responses by multiple effector cells.

The roles of different DC subsets or states in the priming of tumor antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells is of great interest in light of potential strategies to target DCs to enhance antitumor immunity. There is general agreement on a critical role of cDC1s for the induction of CD8+ T-cell-mediated immunity to tumors based on studies in mice with genetic deletion of either Batf3 or Irf8, transcription factors required for the development of the cDC1 lineage69,70. In addition, using cancer cell lines expressing pH-insensitive fluorescent proteins to track tumor antigen transport, a dominant role for CCR7+ migratory cDC1s in tumor antigen delivery to draining LNs was suggested, although migratory cDC2s also played a role. The requirement for CCR7 was not absolute37, implying some redundance with other chemokine receptors, such as potentially CXCR4, as discussed above.

The roles of cDC1s in CD4+ T-cell activation and of cDC2s in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation are less clear. Conflicting results may to some extent be based on the model systems, and especially the nature of the tumor antigen studied. In a setting wherein tumors express a soluble form of the model tumor antigen chicken ovalbumin (Ova), cDC1s from tdLNs poorly activate OT-II TCR transgenic, Ova-specific CD4+ T-cells ex vivo and CD4+ T-cell activation is intact in tdLNs in cDC1-deficient mice. cDC2s, on the other hand, potently activate OT-II cells ex vivo and CD4+ T-cell activation is strongly impaired in IRF4-deficient animals, in which LN migration of cDC2s is largely abrogated20. In contrast to these observations, OT-II proliferation was impaired in cDC1-deficient animals when a membrane-targeted form of ovalbumin thought to replicate the properties of cancer cell-associated tumor antigens, was used as a model tumor antigen71. Importantly, using selective deletion of either MHC II genes or of CD40 in cDC1s, they further established that cDC1s not only serve to transport cell-associated tumor antigens to tdLNs for hand-off to other DCs, but also present antigens directly to CD4+ T-cells via MHC II and in return receive CD40 helper signals from these cells, allowing them to optimally activate both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses against the tumor. On the other hand, preventing antigen presentation on MHC I by cDC1 reduces, but does not abolish, the priming of tumor-reactive CD8+ T-cells, indicating that cDC2s or other antigen-presenting cells can compensate partially.

These earlier studies did not discriminate between migratory and resident cDCs. Recent experiments to monitor CD40L-CD40 interactions between T-cells and DCs in tdLNs in vivo using LIPSTIC, a technology based on cell contact-dependent biotinylation of CD40+ acceptor cells by CD40L+ donor cells, suggest that tumor antigen-specific CD4+ as well as CD8+ T-cells interact to a similar extent with migratory cDC1s and cDC2s, but not with resident cDCs72. Collectively, these studies point to a central role for migratory cDC1s in CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell activation. In addition, cDC1s may serve as a cellular platform for CD4+ T-cell help, while cDC2s contribute but their specific roles will require further study. It is possible that the respective actions of migratory and resident cDCs, and of cDC1s and cDC2s will vary according to the nature of the tumor antigen and the mechanisms used by DCs for its uptake.

Licensing of T-cell immunity by DCs in tumors

Our knowledge of tumor-infiltrating DC functions comes primarily from studies in experimental mouse models. However, the conservation of tumor-infiltrating DC states in humans and mice13 underscores the value of these models in studying DC functions. Furthermore, because tumor-infiltrating DC states are largely conserved across cancer types13, results obtained in the context of a given cancer may be generalized.

Intratumoral cDC1s can produce various chemokines, including CXCL9 and CXCL1073,74, which facilitate cDC1 interactions with, and local activation of, CD8+ T-cells (Figure 2B). Accordingly, gene expression signatures of cDC1s in human tumors often correlate with T-cell infiltration and improved patient survival8,35,75. Intratumoral natural killer (NK) cells can also play a positive role by producing Flt3L and XCL1, which promote cDC1 accumulation8,75. Some intratumoral cDC1s acquire activated phenotypes. A prominent one is identified as the CCR7+ DC state introduced earlier, which is characterized by a profound change in transcriptional activity, including the loss of canonical cDC1 markers such as Clec9a and Xcr135,36. Consequently, experimental systems using Batf3-, Clec9a-, or Xcr1- deficient mice to manipulate the cDC1 lineage will affect activated cDC1s that no longer express canonical cDC1 markers. Current experimental tools make it difficult to discern the functions of cDC1s before or after activation.

Intratumoral cDC2s remain less well understood than cDC1s but are also thought to shape T-cell immunity locally. In patients with melanoma, the density of intratumoral cDC2s is linked to the abundance of conventional CD4+ T-cells and responsiveness to anti-PD-1 therapy, but only in tumors with low regulatory T-cell abundance20. These data suggest that cDC2s can be suppressed by regulatory T-cells but otherwise promote antitumor CD4+ T-cell functions. Interestingly, tumors with high abundance of cDC2s and who responded to anti-PD-1 therapy not only had more conventional CD4+ T-cells but also less CD8+ T-cells, suggesting that intratumoral cDC2s can unleash effective antitumor CD4+ T-cell immune responses with minimal CD8+ T-cell involvement. Like cDC1s, intratumoral cDC2s may acquire an activated CCR7+ phenotype36; however, defining the relative contributions of cDC1- and cDC2-derived CCR7+ DCs will require further study. Intratumoral cDC2s may also express interferon-stimulated genes30. These cells, named ISG+ DCs, are Batf3-independent and distinct from CCR7+ DCs. In mice, ISG+ DCs acquire and present intact tumor-derived peptide-MHC complexes to stimulate CD8+ T-cells30. This process, referred to as MHC-dressing76 77, can promote effective antitumor CD8+ T-cell immunity even in absence of cDC1s30. ISG+ DCs can also be found in human tumors29. Tumor-infiltrating cDC2s probably comprise several states, which may have distinct capacities to promote CD4+ and/or CD8+ T-cell responses, as is the case for their counterparts in LNs71.

CCR7+ DCs that remain in the TME33–35 and which may derive from cDC1s or cDC2s36, can promote antitumor immunity in several ways (Figure 2B). In mice, CCR7+ DCs can densely populate a perivascular niche near post-capillary venules of the tumor stroma. By expressing high levels of the chemokine CXCL16 they attract or retain incoming effector T-cells expressing CXCR6, the receptor for CXCL16, in that niche. By trans-presenting the cytokine interleukin-15 (IL-15), CCR7+ DCs also promote the local survival and proliferative expansion of these T-cells at the transitory effector stage, before these become irreversibly dysfunctional or die33. Some CCR7+ DCs in this tumor perivascular niche also produce interleukin-12 (IL-12), a cytokine that stimulates CD8+ T-cells34 and NK cells78 to produce IFN-γ. These IL-12+ CCR7+ DCs likely derive from cDC1s, whose maturation may depend on the transcription factor IRF179. We still lack understanding of the relative importance of cDC1 abundance versus functional maturation; critical to this would be to identify molecular regulators that specifically block DC maturation and among these, IRF1 is one of possibly many candidates. In any case, IFN-γ produced by lymphocytes not only has antitumor effects, but also enhances IL-12 production by intratumoral CCR7+ DCs. It follows that these CCR7+ DCs are the defining element of a type-I immunity-promoting feedback loop, which involves IFN-γ and IL-12, and is required to license antitumor T-cell responses. This mechanism has been identified in several experimental cancer models, for example in response to PD-1- or CD40-targeted therapies34,80. Overall, the findings accord with a model whereby local DCs educate incoming circulating T-cells for effector differentiation81. In mice, Batf3-dependent cells and IL-12 (probably from cDC1-derived CCR7+ DCs) are required not only for an effector T-cell response, but also for the deployment of antitumor neutrophils82. These cells are recruited from the circulation and need to be licensed at the tumor site to mediate a successful antitumor response.

An increased abundance of intratumoral CCR7+ DCs is generally also beneficial in cancer patients. Indeed, increased expression of CCR7+ DC marker genes in tumors has been associated with improved patient survival in NSCLC and colorectal cancer35,83. Furthermore, the abundance of intratumoral CCR7+ DCs has been directly or indirectly linked to an improved response to immunotherapy in several cases: CCR7+ DCs were enriched in microsatellite instability (MSI)-high colorectal cancer83, which responds better to immune checkpoint blockade (ICB) therapy than its MSI-low counterpart; CCR7+ DCs were also enriched in pretreatment biopsy samples from patients with breast cancer whose tumor-infiltrating T-cells expanded after treatment84 and in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who responded to neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 therapy85. In the latter case, CCR7+ DCs from responders were identified in niches that included CXCL13+ CD4+ helper T-cells and effector CD8+ T-cells. These data suggest that the physical proximity between these cells within tumors promotes the differentiation of CD8+ T-cells into effector cells. These data also reinforce the notion that CCR7+ DCs, because of their strategic positioning near blood vessels, can not only physically interact with various types of hematopoietic cells entering tumors, but also actively control the fate of these cells. Overall, it is tempting to speculate that the basic principles of T-cell activation by DCs in LNs86 also apply to ectopic immune aggregates, and that CD4+ T-cell help allows intratumoral CCR7+ DCs to promote effector responses mediated by CD8+ T-cells. It remains unclear to what extent CCR7+ DC signatures correlate with tertiary lymphoid structure (TLS) features, which also involve interactions with B cells and mesenchyme87. Since both TLSs and CCR7+ DCs portend positive prognoses for many cancer patients, it will be important to investigate the similarities and differences between these two important immune features of cancer. Optimal cancer control may depend on interactions between CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells71, however it is not yet clear whether these interactions need to occur both in the tdLN and the tumor. It is also important to recognize that a better understanding of the possible functional heterogeneity of CCR7+ DCs may refine our understanding of this pivotal DC state in cancer.

DC impairment in cancer

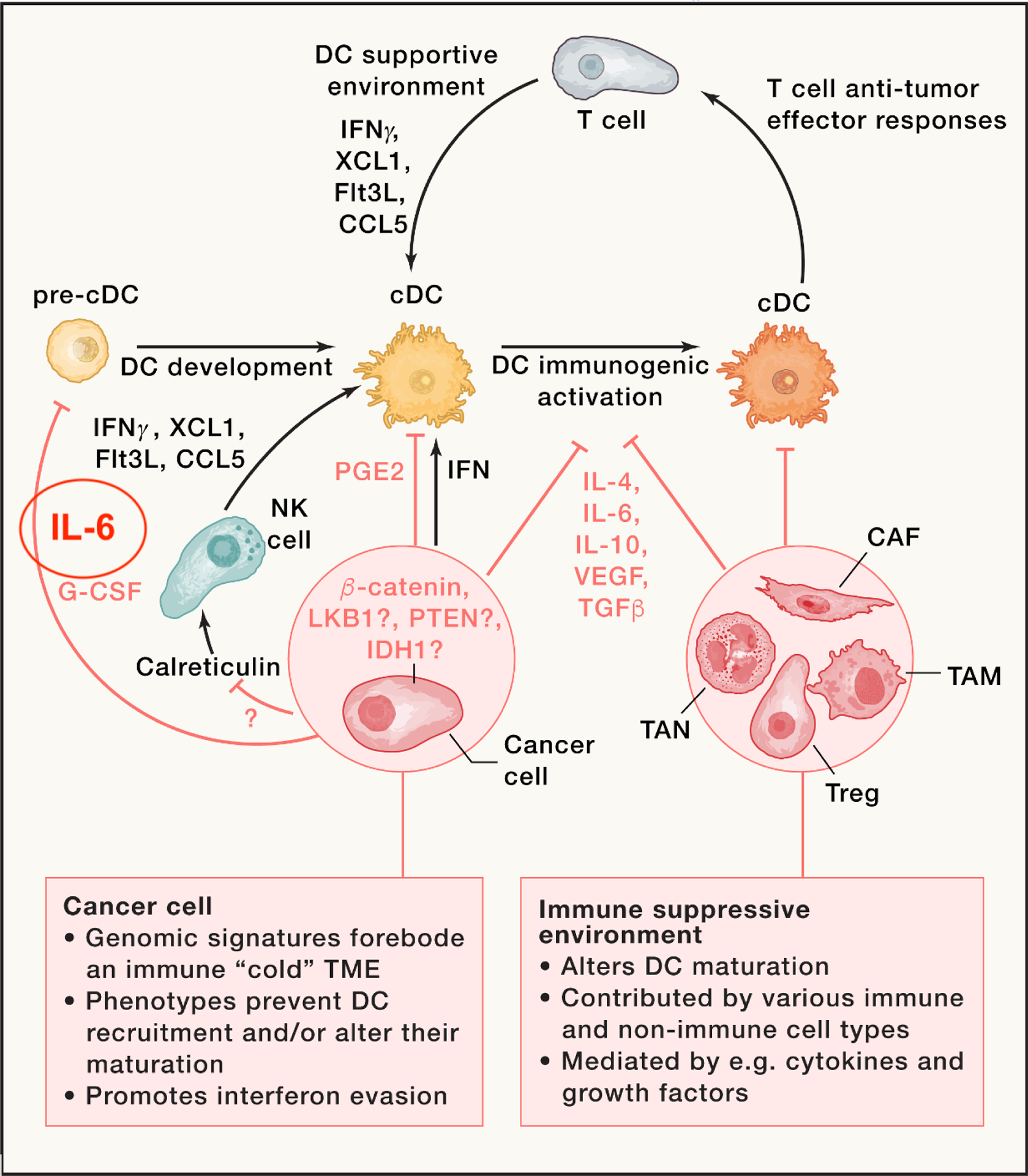

Layering genomic data onto transcriptomic characterization of TMEs has revealed immune cell parameters linked to tumor genotype, and involving DCs and T-cells. One of the earliest efforts to correlate genomic data with immune response compared the genomic signatures of non-T-cell inflamed and T-cell inflamed tumors and showed that tumor-intrinsic beta-catenin signaling leads to the exclusion of cDC1s from the TME7. Adoptive transfer of DCs induced by FLT3L treatment restored immune responses against tumors in pre-clinical models, suggesting that successful recovery of these DCs may be sufficient to promote antitumor immunity. This work set forth a model in which immune “cold” TMEs can result from inhibition of DC infiltration and be driven by defined oncogenic mutations (Figure 3). Paucity of DCs in the TME has also been linked to resistance to immunotherapy in models of mismatch repair proficient (pMMR) colorectal cancer, melanoma, and pancreatic cancer88–90.

Figure 3. Suppression of DC immunogenic maturation by tumors.

DC development within tumors requires a supportive environment, which is driven at least in part by Flt3L, XCL1, CCL5, and IFN-g, which can be produced by various cell types, including natural killer (NK) cells. The latter can be activated by calreticulin following immunogenic tumor cell death. The release of type I interferons can also trigger DC-supportive environments. However, tumors can suppress these environments, for example, by suppressing NK cell activation or type I interferon production, or by releasing factors such as prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), interleukin-6, or granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) that block DC progenitor development. Tumor-derived factors can also condition an immunosuppressive microenvironment consisting of T regulatory (Treg) cells, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs). Together, these mechanisms block T:DC mutualistic interactions and promote evasion of antitumor immunity.

Other cancer genotypes associated with “cold” TMEs, such as LKB1 or PTEN deficiency, or isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mutations, may involve the control of DC function. First, LKB1-deficient lung cancers show high TMB - and possibly high neoantigen content - but low response rates to immunotherapy91, exemplifying that these parameters are not necessarily linked. Normally, cells with genomic instability and DNA damage are detected by the cGAS-STING innate immune pathway, which triggers interferon signaling92 and stimulates DCs and adaptive immune recognition. In contrast, LKB1-deficient tumor cells can silence STING expression91, likely preventing the downstream DC response. In mice, immune evasion of Lkb1-deficient tumors can be reversed by neutralizing IL-6, an inhibitor of DC function91. These data suggest that loss of LKB1 promotes immune evasion at least in part by controlling DC function through an IL-6-dependent mechanism. Second, PTEN-deficient melanomas are associated with poor T-cell infiltration and immunotherapy response. Critically, PTEN-deficient TMEs show decreased CXCL10 and increased VEGF expression, indicative of a DC-suppressive milieu93. Treatment with a PI3K-beta inhibitor in mice can enhance tumor T-cell infiltration and response to checkpoint immunotherapy94, but its effects on DC phenotypes in the TME remain unknown. Third, IDH1-mutant gliomas show fewer IFNg-inducible chemokine and cytotoxic T-cell associated gene signatures compared to IDH-WT gliomas95. Mutant IDH enzymes produce the metabolite R-2-hydroxyglutarate (2-HG), which suppresses CXCL10 and STAT1, leading to T-cell exclusion from tumors. Mutant IDH tumors did not show elevated IL-10, but rather bore defects of IFNg sensing with impairments in STAT1 and IRF1 signaling, which are both critical mediators of DC activation and immunogenic maturation. Still, ongoing studies have yet to directly implicate DCs as core mediators of immune exclusion in IDH1 cancers. Additional investigations are needed to map the associations between cancer genotypes and impaired DC functions.

Beyond genetic alterations in tumor cells, suppression of intratumoral DC responses are linked to aberrant production of certain factors by tumor cells and/or other cell types in the TME (Figure 3). These factors include IL-1096, VEGF97, TGF-beta98, IL-694 99, IL-436, RANKL100, G-CSF101, Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2)102 103 and lipid mediators104,105. Several of these factors - especially IL-6 and IL-10 - likely converge on activating the STAT3 signaling pathway, which has long been implicated in DC dysfunction in the TME106, although it remains unclear how and when STAT3 blocks DCs during their maturation. IL-6 likely has multiple DC inhibitory effects, including its ability to induce C/EBPβ in common dendritic cell precursors (CDPs), which activates Zeb2 and blocks cDC1 development99. Cancer cells can also remotely interfere with DC function through secretion of G-CSF, which shifts bone marrow myelopoiesis toward the production of granulocytes at the expense of cDC1s by inhibiting the expression of IRF8, a transcription factor that is critical for cDC1 commitment of DC precursors101. PGE2 can inhibit cDC1s directly through the decreased expression of IRF8103 and/or by counteracting the effects of Flt3L-producing NK cells that support the development of cDC1s within tumors75. Specific signals mediating NK cell activation in the tumor microenvironment remain unclear; however, calreticulin, long implicated in immunogenic cell death mechanisms107, and found on the surface of ER stressed cells including cancer cells, may mediate NK activation through NKp46108. By extension, factors that disrupt niches supporting DC recruitment, differentiation and/or maturation may all allow tumors to escape antitumor immunity.

Many of the factors that suppress intratumoral DC responses share the capacity to inhibit IL-12 production by DCs, suggesting that DC-derived IL-12 is critical for antitumor immunity. While IL-12 production is generally enriched in CCR7+ DCs, such cells retained in tumors may produce less IL-12 than their counterparts that migrated to tdLNs36; this finding supports the concept that inherent suppression of IL-12 signaling is a common mechanism of dysfunction in tumor DCs. Importantly, CCR7+ DCs also express immunoregulatory molecules, such as PDL136. It is possible that distinct subsets of CCR7+ DCs promote tolerance versus immunity, or that CCR7+ DCs are inherently immunogenic (or tolerogenic) and acquire expression of factors to switch their effector instructions to T-cells. This requires further study.

Collectively, these findings support a model whereby tumors can evade immunity by blocking DC activity. Predictors of tumor antigenicity must factor in the antigen-presenting cells in the TME; indeed, the absence or functional suppression of these cells are important bottlenecks in immune recognition of tumors. The very nature of cancer is rooted in genetic damage. It is possible that tumor intrinsic innate immune sensing of nucleic acids plays an early role in cancer immunogenicity, and that cellular adaptations to suppress interferon responses lie at the core of impaired DC activation and, ultimately, impaired adaptive immunity. As we and others have found, tumor-associated DCs can engage in different activation pathways locally (e.g. becoming CCR7+ DCs that migrate to draining LNs, CCR7+ DCs that accumulate near the tumor vasculature, or ISG+ DCs), providing tumors with many points of interference.

Therapeutic approaches to activate tumor-associated DCs

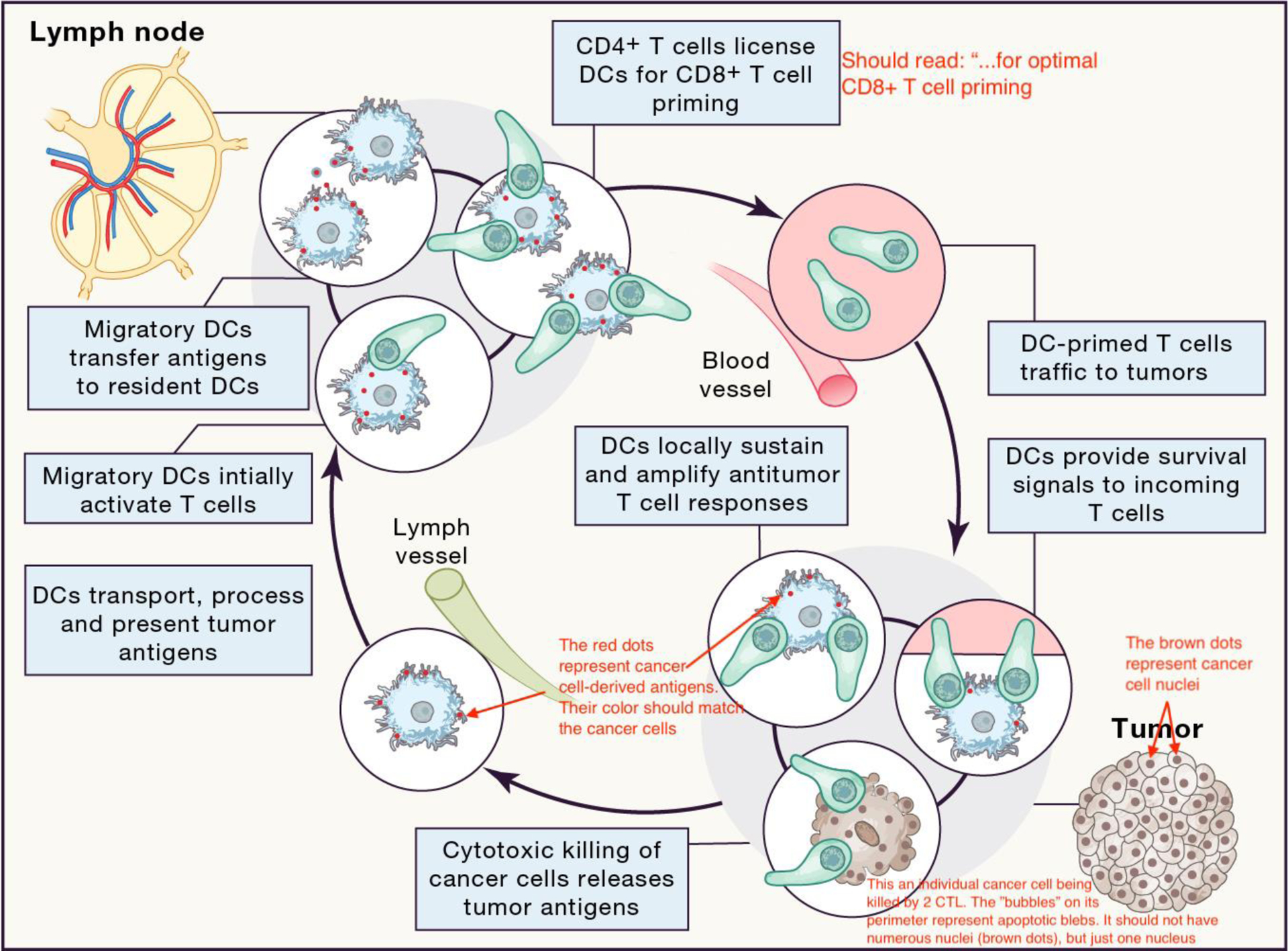

As discussed above, DCs participate in T cell-associated checkpoints throughout the cancer immunity cycle, not only in tumor-draining lymph nodes where they prime naive antitumor T cells, but also in tumors where they drive effector differentiation and survival of incoming T cells. All these processes associated with DCs are necessary for successful antitumor immunity (Figure 4). DCs have been viewed as an attractive therapeutic target in cancer for over two decades. The current understanding opens opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Based on current knowledge of DC biology in cancer, DC therapeutics should aspire to at least two goals. One, to increase the abundance of DCs in both the tumor and tdLNs; and two, to augment DC immunogenic functions, again in both the tumor and tdLNs.

Figure 4. DCs participate in multiple T-cell-associated checkpoints in the cancer immunity cycle.

The original version of the cancer immunity cycle9, which indicated the self-propagating generation of cancer immunity, was divided into several steps, starting with the release of tumor antigens from dying cancer cells and ending with the elimination of cancer cells by antitumor immune cells. Here, we further indicate that DCs participate in T-cell-associated checkpoints in ‘sub-circuits’ throughout the cancer immunity cycle, i.e. not only in tumor-draining lymph nodes where they prime naive antitumor T cells, but also in tumors where they drive effector differentiation and survival of incoming T cells. All these processes associated with DCs are necessary for successful antitumor immunity. Exploiting these checkpoints could be critical in the development of more effective cancer immunotherapies. Blue: DCs; green: T cells; light pink: tumor cells; red dots: tumor antigens.

DC-based vaccination strategies have been employed in humans, but have had varying degrees of success109. The FDA-approved treatment Provenge utilizes DC vaccination with a prostate tumor antigen and GM-CSF-programmed DCs that are derived principally from MoDCs. This treatment yields an average increase of survival of ~4 months110. Perhaps this approach can be enhanced by combination therapies, or the use of bona fide cDC1s as opposed to MoDCs. MoDCs are impaired in antigen presentation and LN migratory features compared to cDC1s111, which could explain the suboptimal effects seen in first-generation DC vaccines. Next-generation DC vaccines likely need to enhance DC abundance and functionality in tdLNs and tumors, so that full-fledged antitumor T-cell responses can occur. Advances in cellular engineering should help to solve these challenges111. For instance, a lentivirus-encoded chimeric receptor named EVIR can enhance DC MHC dressing with tumor antigens112. Furthermore, DC functions exhibit circadian oscillations, resulting in maximized vaccination and immunotherapy responses in the evening in mice, and possibly in the morning in humans113. This suggests that the time of day could be a critical variable in DC vaccination treatments.

Another approach relies on the administration of Flt3L, which has been successfully used in several mouse models to expand cDC1s and achieve enhanced tumor control89. A clinical trial in patients with indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma showed that in situ vaccination with a combination of Flt3L and poly I:C (TLR3 ligand) can induce expansion of intratumoral DCs and promote antitumor immunity114. The degree of T-cell clonality resulting from DC agonistic treatment remains unclear, and further studies are needed to critically examine the T-cell phenotypes elicited by in situ vaccination approaches. Furthermore, while systemic administration of Flt3L likely influences the abundance of DCs in both the tumor and tumor-draining LNs, the effects of in situ vaccination on tumor-draining LNs are currently unknown.

CD40 agonism has also long been employed in efforts to activate DCs and enhance antitumor immunity115. These approaches, which have relied upon agonistic antibodies, have delivered mostly modest single agent activity in clinical trials. However, use of these agents increases tumor T-cell infiltration in human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma116. Following the insight that the degree of agonism of CD40 antibodies depends upon Fc-FcR interactions117,118, second-generation, Fc-engineered variants have now entered clinical testing in solid cancers (NCT04059588), gliomas (NCT04547777), and bladder cancer (NCT05126472). Approaches to target CD40 agonists to DCs specifically with engineered bispecific antibodies are also underway119. Again, with these therapies it is still unclear whether local DC activation at the tumor site, or responses in the tdLNs are required for therapeutic efficacy – underscoring the importance of spatial investigation of DCs in immunotherapy.

Finally, increasingly refined definitions and characterization of tumor DC states from scRNAseq studies are beginning to reveal molecular targets to leverage DC biology for therapy. For example, numerous sequencing studies show enrichment of the non-canonical NFkB signaling pathway genes in CCR7+ DCs34–36. This pathway is associated with cross-presentation of antigen and response to CD40 agonism, and is increased at peak DC circadian response time113,120,121. Inhibition of cellular inhibitor of apoptosis (cIAPs) can activate DCs and trigger antitumor immunity6,34,122,123. Furthermore, combination of cIAP inhibition with TLR7/8 agonism could potently enhance IL-12 responses and eradicate tumors in pre-clinical mouse models of immunologically “cold” glioblastoma124. scRNAseq-based profiling has also identified the role of IL-4 signaling on suppressing immunogenic functions of CCR7+ DCs in mice36. It would be interesting to examine whether IL-4 neutralizing antibodies (e.g. Duxipent)125 or traditional antiallergic drugs have antitumor properties in humans.

Concluding remarks

The original model of the Cancer Immunity Cycle, published in 2013, was primarily based on non-tumor observations, but nonetheless proved to be particularly instructive. It is now clear that DCs play a role not only in LNs, but also in the TME. During the past years, the widespread adoption of single cell transcriptomic technologies has produced an explosion of information on the molecular states of all cells found in solid tumors, not only in mouse models of cancer, but also in cancer patients. DCs and T-cells have been repeatedly rediscovered in these studies for their contribution to signatures that predict immunotherapy success and favorable disease outcome. This highlights the central importance of these two cell lineages, whose fates are inextricably linked, even beyond our prior conception of DC:T cell communication restricted to LNs. While the search for predictive biomarkers of disease progression has been a major driver of these studies, new biological insights have also been obtained into the diversity of cell subsets and states, leading to hypotheses about how immune, stromal and cancer cells interact and integrate their activities. In some cases, these hypotheses have been tested in mouse models, leading to new mechanistic insights into the nature of antitumor immune responses. It will be important to embed this new knowledge into our overall understanding of immune cell development, activation and differentiation, and how immune responses are orchestrated. This will eventually allow us to harvest the fruits of the omics revolution and hopefully better leverage DCs in therapy to robustly control cancer.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the ISREC Foundation (to M.J.P.), Ludwig Cancer Research (to M.J.P.), NIH grant P01-CA240239 (to M.J.P. and T.R.M.) and R01 AI123349 (to T.R.M.), CPRIT RR210017 (to M.D.P), Melanoma SPORE P50CA221703 (to M.D.P), the Karin Grunebaum Foundation (to C.G.), and the Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network Research Innovation Award (to C.G).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Competing Interests

M.J.P. has served as consultant for Acthera, AstraZeneca, Debiopharm, Elstar Therapeutics, ImmuneOncia, KSQ Therapeutics, MaxiVax, Merck, Molecular Partners, Siamab Therapeutics, Third Rock Ventures, Tidal. T.R.M. is a co-founder and consultant and M.D.P. is a consultant for Monopteros Therapeutics. C.G. has served as a consultant for Cellino Biotech.

References

- 1.Schumacher TN, and Schreiber RD (2015). Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 348, 69–74. 10.1126/science.aaa4971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finn OJ (2017). Human Tumor Antigens Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. Cancer Immunol Res 5, 347–354. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, Kvistborg P, Makarov V, Havel JJ, Lee W, Yuan J, Wong P, Ho TS, et al. (2015). Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science 348, 124–128. 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samstein RM, Lee CH, Shoushtari AN, Hellmann MD, Shen R, Janjigian YY, Barron DA, Zehir A, Jordan EJ, Omuro A, et al. (2019). Tumor mutational load predicts survival after immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. Nat Genet 51, 202–206. 10.1038/s41588-018-0312-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spranger S, Luke JJ, Bao R, Zha Y, Hernandez KM, Li Y, Gajewski AP, Andrade J, and Gajewski TF (2016). Density of immunogenic antigens does not explain the presence or absence of the T-cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment in melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, E7759–E7768. 10.1073/pnas.1609376113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoefsmit EP, van Royen PT, Rao D, Stunnenberg JA, Dimitriadis P, Lieftink C, Morris B, Rozeman EA, Reijers ILM, Lacroix R, et al. (2023). Inhibitor of Apoptosis Proteins Antagonist Induces T-cell Proliferation after Cross-Presentation by Dendritic Cells. Cancer Immunol Res 11, 450–465. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-22-0494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spranger S, Bao R, and Gajewski TF (2015). Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature 523, 231–235. 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barry KC, Hsu J, Broz ML, Cueto FJ, Binnewies M, Combes AJ, Nelson AE, Loo K, Kumar R, Rosenblum MD, et al. (2018). A natural killer-dendritic cell axis defines checkpoint therapy-responsive tumor microenvironments. Nat Med 24, 1178–1191. 10.1038/s41591-018-0085-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen DS, and Mellman I (2013). Oncology meets immunology: the cancer-immunity cycle. Immunity 39, 1–10. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinman RM, and Cohn ZA (1973). Identification of a novel cell type in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice. I. Morphology, quantitation, tissue distribution. J Exp Med 137, 1142–1162. 10.1084/jem.137.5.1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iwasaki A, and Medzhitov R (2015). Control of adaptive immunity by the innate immune system. Nat Immunol 16, 343–353. 10.1038/ni.3123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yin X, Chen S, and Eisenbarth SC (2021). Dendritic Cell Regulation of T Helper Cells. Annu Rev Immunol 39, 759–790. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-101819-025146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerhard GM, Bill R, Messemaker M, Klein AM, and Pittet MJ (2021). Tumor-infiltrating dendritic cell states are conserved across solid human cancers. J Exp Med 218. 10.1084/jem.20200264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlitzer A, McGovern N, and Ginhoux F (2015). Dendritic cells and monocyte-derived cells: Two complementary and integrated functional systems. Semin Cell Dev Biol 41, 9–22. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu K, Victora GD, Schwickert TA, Guermonprez P, Meredith MM, Yao K, Chu FF, Randolph GJ, Rudensky AY, and Nussenzweig M (2009). In vivo analysis of dendritic cell development and homeostasis. Science 324, 392–397. 10.1126/science.1170540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, van Blijswijk J, Wienert S, Heim D, Jenkins RP, Chakravarty P, Rogers N, Frederico B, Acton S, Beerling E, et al. (2019). Tissue clonality of dendritic cell subsets and emergency DCpoiesis revealed by multicolor fate mapping of DC progenitors. Sci Immunol 4. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaw1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, Minutti CM, da Costa MP, Cardoso A, Jenkins RP, Kulikauskaite J, Buck MD, Piot C, Rogers N, Crotta S, et al. (2021). Recruitment of dendritic cell progenitors to foci of influenza A virus infection sustains immunity. Sci Immunol 6, eabi9331. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abi9331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Villani AC, Satija R, Reynolds G, Sarkizova S, Shekhar K, Fletcher J, Griesbeck M, Butler A, Zheng S, Lazo S, et al. (2017). Single-cell RNA-seq reveals new types of human blood dendritic cells, monocytes, and progenitors. Science 356. 10.1126/science.aah4573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ugur M, Labios RJ, Fenton C, Knopper K, Jobin K, Imdahl F, Golda G, Hoh K, Grafen A, Kaisho T, et al. (2023). Lymph node medulla regulates the spatiotemporal unfolding of resident dendritic cell networks. Immunity. 10.1016/j.immuni.2023.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Binnewies M, Mujal AM, Pollack JL, Combes AJ, Hardison EA, Barry KC, Tsui J, Ruhland MK, Kersten K, Abushawish MA, et al. (2019). Unleashing Type-2 Dendritic Cells to Drive Protective Antitumor CD4(+) T Cell Immunity. Cell 177, 556–571 e516. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown CC, Gudjonson H, Pritykin Y, Deep D, Lavallee VP, Mendoza A, Fromme R, Mazutis L, Ariyan C, Leslie C, et al. (2019). Transcriptional Basis of Mouse and Human Dendritic Cell Heterogeneity. Cell 179, 846–863 e824. 10.1016/j.cell.2019.09.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dutertre CA, Becht E, Irac SE, Khalilnezhad A, Narang V, Khalilnezhad S, Ng PY, van den Hoogen LL, Leong JY, Lee B, et al. (2019). Single-Cell Analysis of Human Mononuclear Phagocytes Reveals Subset-Defining Markers and Identifies Circulating Inflammatory Dendritic Cells. Immunity 51, 573–589 e578. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qian BZ, Li J, Zhang H, Kitamura T, Zhang J, Campion LR, Kaiser EA, Snyder LA, and Pollard JW (2011). CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature 475, 222–225. 10.1038/nature10138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dieu MC, Vanbervliet B, Vicari A, Bridon JM, Oldham E, Ait-Yahia S, Briere F, Zlotnik A, Lebecque S, and Caux C (1998). Selective recruitment of immature and mature dendritic cells by distinct chemokines expressed in different anatomic sites. J Exp Med 188, 373–386. 10.1084/jem.188.2.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Borgne M, Etchart N, Goubier A, Lira SA, Sirard JC, van Rooijen N, Caux C, Ait-Yahia S, Vicari A, Kaiserlian D, and Dubois B (2006). Dendritic cells rapidly recruited into epithelial tissues via CCR6/CCL20 are responsible for CD8+ T cell crosspriming in vivo. Immunity 24, 191–201. 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cook SJ, Lee Q, Wong AC, Spann BC, Vincent JN, Wong JJ, Schlitzer A, Gorrell MD, Weninger W, and Roediger B (2018). Differential chemokine receptor expression and usage by pre-cDC1 and pre-cDC2. Immunol Cell Biol 96, 1131–1139. 10.1111/imcb.12186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canton J, Blees H, Henry CM, Buck MD, Schulz O, Rogers NC, Childs E, Zelenay S, Rhys H, Domart MC, et al. (2021). The receptor DNGR-1 signals for phagosomal rupture to promote cross-presentation of dead-cell-associated antigens. Nat Immunol 22, 140–153. 10.1038/s41590-020-00824-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosteels C, Neyt K, Vanheerswynghels M, van Helden MJ, Sichien D, Debeuf N, De Prijck S, Bosteels V, Vandamme N, Martens L, et al. (2020). Inflammatory Type 2 cDCs Acquire Features of cDC1s and Macrophages to Orchestrate Immunity to Respiratory Virus Infection. Immunity 52, 1039–1056 e1039. 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng S, Li Z, Gao R, Xing B, Gao Y, Yang Y, Qin S, Zhang L, Ouyang H, Du P, et al. (2021). A pan-cancer single-cell transcriptional atlas of tumor infiltrating myeloid cells. Cell 184, 792–809 e723. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duong E, Fessenden TB, Lutz E, Dinter T, Yim L, Blatt S, Bhutkar A, Wittrup KD, and Spranger S (2022). Type I interferon activates MHC class I-dressed CD11b(+) conventional dendritic cells to promote protective anti-tumor CD8(+) T cell immunity. Immunity 55, 308–323 e309. 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kagan L.C.a.J. (2023). Targeting Innate Immune Pathways for Cancer Immunotherapy. Immunity. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.To Tsun Ki Jerrick, D. S, Folkert Ian W., Zhai Li, Lobel Graham P., Haldar Malay (2022). Single-cell transcriptomics reveal distinct subsets of activated dendritic cells in the tumor microenvironment. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.09.13.507746. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Di Pilato M, Kfuri-Rubens R, Pruessmann JN, Ozga AJ, Messemaker M, Cadilha BL, Sivakumar R, Cianciaruso C, Warner RD, Marangoni F, et al. (2021). CXCR6 positions cytotoxic T cells to receive critical survival signals in the tumor microenvironment. Cell 184, 4512–4530 e4522. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garris CS, Arlauckas SP, Kohler RH, Trefny MP, Garren S, Piot C, Engblom C, Pfirschke C, Siwicki M, Gungabeesoon J, et al. (2018). Successful Anti-PD-1 Cancer Immunotherapy Requires T Cell-Dendritic Cell Crosstalk Involving the Cytokines IFN-gamma and IL-12. Immunity 49, 1148–1161 e1147. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zilionis R, Engblom C, Pfirschke C, Savova V, Zemmour D, Saatcioglu HD, Krishnan I, Maroni G, Meyerovitz CV, Kerwin CM, et al. (2019). Single-Cell Transcriptomics of Human and Mouse Lung Cancers Reveals Conserved Myeloid Populations across Individuals and Species. Immunity 50, 1317–1334 e1310. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maier B, Leader AM, Chen ST, Tung N, Chang C, LeBerichel J, Chudnovskiy A, Maskey S, Walker L, Finnigan JP, et al. (2020). A conserved dendritic-cell regulatory program limits antitumour immunity. Nature 580, 257–262. 10.1038/s41586-020-2134-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts EW, Broz ML, Binnewies M, Headley MB, Nelson AE, Wolf DM, Kaisho T, Bogunovic D, Bhardwaj N, and Krummel MF (2016). Critical Role for CD103(+)/CD141(+) Dendritic Cells Bearing CCR7 for Tumor Antigen Trafficking and Priming of T Cell Immunity in Melanoma. Cancer Cell 30, 324–336. 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruhland MK, Roberts EW, Cai E, Mujal AM, Marchuk K, Beppler C, Nam D, Serwas NK, Binnewies M, and Krummel MF (2020). Visualizing Synaptic Transfer of Tumor Antigens among Dendritic Cells. Cancer Cell 37, 786–799 e785. 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rawat K, Tewari A, Li X, Mara AB, King WT, Gibbings SL, Nnam CF, Kolling FW, Lambrecht BN, and Jakubzick CV (2023). CCL5-producing migratory dendritic cells guide CCR5+ monocytes into the draining lymph nodes. J Exp Med 220. 10.1084/jem.20222129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kabashima K, Shiraishi N, Sugita K, Mori T, Onoue A, Kobayashi M, Sakabe J, Yoshiki R, Tamamura H, Fujii N, et al. (2007). CXCL12-CXCR4 engagement is required for migration of cutaneous dendritic cells. Am J Pathol 171, 1249–1257. 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Steele MM, Jaiswal A, Delclaux I, Dryg ID, Murugan D, Femel J, Son S, du Bois H, Hill C, Leachman SA, et al. (2023). T cell egress via lymphatic vessels is tuned by antigen encounter and limits tumor control. Nat Immunol 24, 664–675. 10.1038/s41590-023-01443-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sokol CL, Camire RB, Jones MC, and Luster AD (2018). The Chemokine Receptor CCR8 Promotes the Migration of Dendritic Cells into the Lymph Node Parenchyma to Initiate the Allergic Immune Response. Immunity 49, 449–463 e446. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greter M, Helft J, Chow A, Hashimoto D, Mortha A, Agudo-Cantero J, Bogunovic M, Gautier EL, Miller J, Leboeuf M, et al. (2012). GM-CSF controls nonlymphoid tissue dendritic cell homeostasis but is dispensable for the differentiation of inflammatory dendritic cells. Immunity 36, 1031–1046. 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rodrigues PF, Alberti-Servera L, Eremin A, Grajales-Reyes GE, Ivanek R, and Tussiwand R (2018). Distinct progenitor lineages contribute to the heterogeneity of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 19, 711–722. 10.1038/s41590-018-0136-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cella M, Jarrossay D, Facchetti F, Alebardi O, Nakajima H, Lanzavecchia A, and Colonna M (1999). Plasmacytoid monocytes migrate to inflamed lymph nodes and produce large amounts of type I interferon. Nat Med 5, 919–923. 10.1038/11360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Villadangos JA, and Young L (2008). Antigen-presentation properties of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Immunity 29, 352–361. 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Ohteki T, Ginhoux F, Shortman K, and Spits H (2023). Reclassifying plasmacytoid dendritic cells as innate lymphocytes. Nat Rev Immunol 23, 1–2. 10.1038/s41577-022-00806-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brewitz A, Eickhoff S, Dahling S, Quast T, Bedoui S, Kroczek RA, Kurts C, Garbi N, Barchet W, Iannacone M, et al. (2017). CD8(+) T Cells Orchestrate pDC-XCR1(+) Dendritic Cell Spatial and Functional Cooperativity to Optimize Priming. Immunity 46, 205–219. 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kvedaraite E, and Ginhoux F (2022). Human dendritic cells in cancer. Sci Immunol 7, eabm9409. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abm9409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Braun A, Worbs T, Moschovakis GL, Halle S, Hoffmann K, Bolter J, Munk A, and Forster R (2011). Afferent lymph-derived T cells and DCs use different chemokine receptor CCR7-dependent routes for entry into the lymph node and intranodal migration. Nat Immunol 12, 879–887. 10.1038/ni.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ingulli E, Ulman DR, Lucido MM, and Jenkins MK (2002). In situ analysis reveals physical interactions between CD11b+ dendritic cells and antigen-specific CD4 T cells after subcutaneous injection of antigen. J Immunol 169, 2247–2252. 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stoll S, Delon J, Brotz TM, and Germain RN (2002). Dynamic imaging of T cell-dendritic cell interactions in lymph nodes. Science 296, 1873–1876. 10.1126/science.1071065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller MJ, Wei SH, Parker I, and Cahalan MD (2002). Two-photon imaging of lymphocyte motility and antigen response in intact lymph node. Science 296, 1869–1873. 10.1126/science.1070051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bousso P, and Robey E (2003). Dynamics of CD8+ T cell priming by dendritic cells in intact lymph nodes. Nat Immunol 4, 579–585. 10.1038/ni928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miller MJ, Wei SH, Cahalan MD, and Parker I (2003). Autonomous T cell trafficking examined in vivo with intravital two-photon microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100, 2604–2609. 10.1073/pnas.2628040100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mempel TR, Henrickson SE, and Von Andrian UH (2004). T-cell priming by dendritic cells in lymph nodes occurs in three distinct phases. Nature 427, 154–159. 10.1038/nature02238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shakhar G, Lindquist RL, Skokos D, Dudziak D, Huang JH, Nussenzweig MC, and Dustin ML (2005). Stable T cell-dendritic cell interactions precede the development of both tolerance and immunity in vivo. Nat Immunol 6, 707–714. 10.1038/ni1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller MJ, Safrina O, Parker I, and Cahalan MD (2004). Imaging the single cell dynamics of CD4+ T cell activation by dendritic cells in lymph nodes. J Exp Med 200, 847–856. 10.1084/jem.20041236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Henrickson SE, Mempel TR, Mazo IB, Liu B, Artyomov MN, Zheng H, Peixoto A, Flynn MP, Senman B, Junt T, et al. (2008). T cell sensing of antigen dose governs interactive behavior with dendritic cells and sets a threshold for T cell activation. Nat Immunol 9, 282–291. 10.1038/ni1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Henrickson SE, Perro M, Loughhead SM, Senman B, Stutte S, Quigley M, Alexe G, Iannacone M, Flynn MP, Omid S, et al. (2013). Antigen availability determines CD8(+) T cell-dendritic cell interaction kinetics and memory fate decisions. Immunity 39, 496–507. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hugues S, Fetler L, Bonifaz L, Helft J, Amblard F, and Amigorena S (2004). Distinct T cell dynamics in lymph nodes during the induction of tolerance and immunity. Nat Immunol 5, 1235–1242. 10.1038/ni1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fife BT, Pauken KE, Eagar TN, Obu T, Wu J, Tang Q, Azuma M, Krummel MF, and Bluestone JA (2009). Interactions between PD-1 and PD-L1 promote tolerance by blocking the TCR-induced stop signal. Nat Immunol 10, 1185–1192. 10.1038/ni.1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tadokoro CE, Shakhar G, Shen S, Ding Y, Lino AC, Maraver A, Lafaille JJ, and Dustin ML (2006). Regulatory T cells inhibit stable contacts between CD4+ T cells and dendritic cells in vivo. J Exp Med 203, 505–511. 10.1084/jem.20050783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Itano AA, McSorley SJ, Reinhardt RL, Ehst BD, Ingulli E, Rudensky AY, and Jenkins MK (2003). Distinct dendritic cell populations sequentially present antigen to CD4 T cells and stimulate different aspects of cell-mediated immunity. Immunity 19, 47–57. 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gerner MY, Casey KA, Kastenmuller W, and Germain RN (2017). Dendritic cell and antigen dispersal landscapes regulate T cell immunity. J Exp Med 214, 3105–3122. 10.1084/jem.20170335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hor JL, Whitney PG, Zaid A, Brooks AG, Heath WR, and Mueller SN (2015). Spatiotemporally Distinct Interactions with Dendritic Cell Subsets Facilitates CD4+ and CD8+ T Cell Activation to Localized Viral Infection. Immunity 43, 554–565. 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kitano M, Yamazaki C, Takumi A, Ikeno T, Hemmi H, Takahashi N, Shimizu K, Fraser SE, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, and Okada T (2016). Imaging of the cross-presenting dendritic cell subsets in the skin-draining lymph node. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 113, 1044–1049. 10.1073/pnas.1513607113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eickhoff S, Brewitz A, Gerner MY, Klauschen F, Komander K, Hemmi H, Garbi N, Kaisho T, Germain RN, and Kastenmuller W (2015). Robust Anti-viral Immunity Requires Multiple Distinct T Cell-Dendritic Cell Interactions. Cell 162, 1322–1337. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hildner K, Edelson BT, Purtha WE, Diamond M, Matsushita H, Kohyama M, Calderon B, Schraml BU, Unanue ER, Diamond MS, et al. (2008). Batf3 deficiency reveals a critical role for CD8alpha+ dendritic cells in cytotoxic T cell immunity. Science 322, 1097–1100. 10.1126/science.1164206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Broz ML, Binnewies M, Boldajipour B, Nelson AE, Pollack JL, Erle DJ, Barczak A, Rosenblum MD, Daud A, Barber DL, et al. (2014). Dissecting the Tumor Myeloid Compartment Reveals Rare Activating Antigen-Presenting Cells Critical for T Cell Immunity. Cancer Cell 26, 938. 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferris ST, Durai V, Wu R, Theisen DJ, Ward JP, Bern MD, Davidson J.T.t., Bagadia P, Liu T, Briseno CG, et al. (2020). cDC1 prime and are licensed by CD4(+) T cells to induce anti-tumour immunity. Nature 584, 624–629. 10.1038/s41586-020-2611-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chudnovskiy Aleksey, N.-H. S, Castro Tiago BR, Cui Ang, Lin Chia-Hao, Sade-Feldman Moshe, Phillips Brooke K., Pae Juhee, Mesin Luka, Bortolatto Juliana, Schweitzer Lawrence D., Pasqual Giulia, Lu Li-Fan, Hacohen Nir, Victora Gabriel D. (2022). Proximity-dependent labeling identifies dendritic cells that prime the antitumor CD4+ T cell response. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2022.10.25.513771. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spranger S, Dai D, Horton B, and Gajewski TF (2017). Tumor-Residing Batf3 Dendritic Cells Are Required for Effector T Cell Trafficking and Adoptive T Cell Therapy. Cancer Cell 31, 711–723 e714. 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chow MT, Ozga AJ, Servis RL, Frederick DT, Lo JA, Fisher DE, Freeman GJ, Boland GM, and Luster AD (2019). Intratumoral Activity of the CXCR3 Chemokine System Is Required for the Efficacy of Anti-PD-1 Therapy. Immunity 50, 1498–1512 e1495. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bottcher JP, Bonavita E, Chakravarty P, Blees H, Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, Sammicheli S, Rogers NC, Sahai E, Zelenay S, and Reis e Sousa C (2018). NK Cells Stimulate Recruitment of cDC1 into the Tumor Microenvironment Promoting Cancer Immune Control. Cell 172, 1022–1037 e1014. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Martinez-Usatorre A, and De Palma M (2022). Dendritic cell cross-dressing and tumor immunity. EMBO Mol Med 14, e16523. 10.15252/emmm.202216523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.MacNabb BW, Chen X, Tumuluru S, Godfrey J, Kasal DN, Yu J, Jongsma MLM, Spaapen RM, Kline DE, and Kline J (2022). Dendritic cells can prime anti-tumor CD8(+) T cell responses through major histocompatibility complex cross-dressing. Immunity 55, 2206–2208. 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mittal D, Vijayan D, Putz EM, Aguilera AR, Markey KA, Straube J, Kazakoff S, Nutt SL, Takeda K, Hill GR, et al. (2017). Interleukin-12 from CD103(+) Batf3-Dependent Dendritic Cells Required for NK-Cell Suppression of Metastasis. Cancer Immunol Res 5, 1098–1108. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ghislat G, Cheema AS, Baudoin E, Verthuy C, Ballester PJ, Crozat K, Attaf N, Dong C, Milpied P, Malissen B, et al. (2021). NF-kappaB-dependent IRF1 activation programs cDC1 dendritic cells to drive antitumor immunity. Sci Immunol 6. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abg3570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pfirschke C, Zilionis R, Engblom C, Messemaker M, Zou AE, Rickelt S, Gort-Freitas NA, Lin Y, Bill R, Siwicki M, et al. (2022). Macrophage-Targeted Therapy Unlocks Antitumoral Cross-talk between IFNgamma-Secreting Lymphocytes and IL12-Producing Dendritic Cells. Cancer Immunol Res 10, 40–55. 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-21-0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prokhnevska N, Cardenas MA, Valanparambil RM, Sobierajska E, Barwick BG, Jansen C, Reyes Moon A, Gregorova P, delBalzo L, Greenwald R, et al. (2023). CD8(+) T cell activation in cancer comprises an initial activation phase in lymph nodes followed by effector differentiation within the tumor. Immunity 56, 107–124 e105. 10.1016/j.immuni.2022.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gungabeesoon J, Gort-Freitas NA, Kiss M, Bolli E, Messemaker M, Siwicki M, Hicham M, Bill R, Koch P, Cianciaruso C, et al. (2023). A neutrophil response linked to tumor control in immunotherapy. Cell 186, 1448–1464 e1420. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.02.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zhang L, Li Z, Skrzypczynska KM, Fang Q, Zhang W, O’Brien SA, He Y, Wang L, Zhang Q, Kim A, et al. (2020). Single-Cell Analyses Inform Mechanisms of Myeloid-Targeted Therapies in Colon Cancer. Cell 181, 442–459 e429. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bassez A, Vos H, Van Dyck L, Floris G, Arijs I, Desmedt C, Boeckx B, Vanden Bempt M, Nevelsteen I, Lambein K, et al. (2021). A single-cell map of intratumoral changes during anti-PD1 treatment of patients with breast cancer. Nat Med 27, 820–832. 10.1038/s41591-021-01323-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Magen A, Hamon P, Fiaschi N, Soong BY, Park MD, Mattiuz R, Humblin E, Troncoso L, D’Souza D, Dawson T, et al. (2023). Intratumoral dendritic cell-CD4(+) T helper cell niches enable CD8(+) T cell differentiation following PD-1 blockade in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Med. 10.1038/s41591-023-02345-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Borst J, Ahrends T, Babala N, Melief CJM, and Kastenmuller W (2018). CD4(+) T cell help in cancer immunology and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 18, 635–647. 10.1038/s41577-018-0044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schumacher TN, and Thommen DS (2022). Tertiary lymphoid structures in cancer. Science 375, eabf9419. 10.1126/science.abf9419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ho WW, Gomes-Santos IL, Aoki S, Datta M, Kawaguchi K, Talele NP, Roberge S, Ren J, Liu H, Chen IX, et al. (2021). Dendritic cell paucity in mismatch repair-proficient colorectal cancer liver metastases limits immune checkpoint blockade efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118. 10.1073/pnas.2105323118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Salmon H, Idoyaga J, Rahman A, Leboeuf M, Remark R, Jordan S, Casanova-Acebes M, Khudoynazarova M, Agudo J, Tung N, et al. (2016). Expansion and Activation of CD103(+) Dendritic Cell Progenitors at the Tumor Site Enhances Tumor Responses to Therapeutic PD-L1 and BRAF Inhibition. Immunity 44, 924–938. 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hegde S, Krisnawan VE, Herzog BH, Zuo C, Breden MA, Knolhoff BL, Hogg GD, Tang JP, Baer JM, Mpoy C, et al. (2020). Dendritic Cell Paucity Leads to Dysfunctional Immune Surveillance in Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer Cell 37, 289–307 e289. 10.1016/j.ccell.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kitajima S, Ivanova E, Guo S, Yoshida R, Campisi M, Sundararaman SK, Tange S, Mitsuishi Y, Thai TC, Masuda S, et al. (2019). Suppression of STING Associated with LKB1 Loss in KRAS-Driven Lung Cancer. Cancer Discov 9, 34–45. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mackenzie KJ, Carroll P, Martin CA, Murina O, Fluteau A, Simpson DJ, Olova N, Sutcliffe H, Rainger JK, Leitch A, et al. (2017). cGAS surveillance of micronuclei links genome instability to innate immunity. Nature 548, 461–465. 10.1038/nature23449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Peng W, Chen JQ, Liu C, Malu S, Creasy C, Tetzlaff MT, Xu C, McKenzie JA, Zhang C, Liang X, et al. (2016). Loss of PTEN Promotes Resistance to T Cell-Mediated Immunotherapy. Cancer Discov 6, 202–216. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Park SJ, Nakagawa T, Kitamura H, Atsumi T, Kamon H, Sawa S, Kamimura D, Ueda N, Iwakura Y, Ishihara K, et al. (2004). IL-6 regulates in vivo dendritic cell differentiation through STAT3 activation. J Immunol 173, 3844–3854. 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.3844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kohanbash G, Carrera DA, Shrivastav S, Ahn BJ, Jahan N, Mazor T, Chheda ZS, Downey KM, Watchmaker PB, Beppler C, et al. (2017). Isocitrate dehydrogenase mutations suppress STAT1 and CD8+ T cell accumulation in gliomas. J Clin Invest 127, 1425–1437. 10.1172/JCI90644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ruffell B, Chang-Strachan D, Chan V, Rosenbusch A, Ho CM, Pryer N, Daniel D, Hwang ES, Rugo HS, and Coussens LM (2014). Macrophage IL-10 blocks CD8+ T cell-dependent responses to chemotherapy by suppressing IL-12 expression in intratumoral dendritic cells. Cancer Cell 26, 623–637. 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Osada T, Chong G, Tansik R, Hong T, Spector N, Kumar R, Hurwitz HI, Dev I, Nixon AB, Lyerly HK, et al. (2008). The effect of anti-VEGF therapy on immature myeloid cell and dendritic cells in cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother 57, 1115–1124. 10.1007/s00262-007-0441-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kobie JJ, Wu RS, Kurt RA, Lou S, Adelman MK, Whitesell LJ, Ramanathapuram LV, Arteaga CL, and Akporiaye ET (2003). Transforming growth factor beta inhibits the antigen-presenting functions and antitumor activity of dendritic cell vaccines. Cancer Res 63, 1860–1864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim S, Chen J, Jo S, Ou F, Ferris ST, Liu TT, Ohara RA, Anderson DA, Wu R, Chen MY, et al. (2023). IL-6 selectively suppresses cDC1 specification via C/EBPbeta. J Exp Med 220. 10.1084/jem.20221757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ahern E, Smyth MJ, Dougall WC, and Teng MWL (2018). Roles of the RANKL-RANK axis in antitumour immunity - implications for therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15, 676–693. 10.1038/s41571-018-0095-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Meyer MA, Baer JM, Knolhoff BL, Nywening TM, Panni RZ, Su X, Weilbaecher KN, Hawkins WG, Ma C, Fields RC, et al. (2018). Breast and pancreatic cancer interrupt IRF8-dependent dendritic cell development to overcome immune surveillance. Nat Commun 9, 1250. 10.1038/s41467-018-03600-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zelenay S, van der Veen AG, Bottcher JP, Snelgrove KJ, Rogers N, Acton SE, Chakravarty P, Girotti MR, Marais R, Quezada SA, et al. (2015). Cyclooxygenase-Dependent Tumor Growth through Evasion of Immunity. Cell 162, 1257–1270. 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bayerl F, Meiser P, Donakonda S, Hirschberger A, Lacher SB, Pedde AM, Hermann CD, Elewaut A, Knolle M, Ramsauer L, et al. (2023). Tumor-derived prostaglandin E2 programs cDC1 dysfunction to impair intratumoral orchestration of anti-cancer T cell responses. Immunity 56, 1341–1358 e1311. 10.1016/j.immuni.2023.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]