Abstract

Background

There is a significant research gap in the field of universal, selective, and indicated prevention interventions for mental health promotion and the prevention of mental disorders. Barriers to closing the research gap include scarcity of skilled human resources, large inequities in resource distribution and utilization, and stigma.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of delivery by primary workers of interventions for the promotion of mental health and universal prevention, and for the selective and indicated prevention of mental disorders or symptoms of mental illness in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs). To examine the impact of intervention delivery by primary workers on resource use and costs.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, Global Index Medicus, PsycInfo, WHO ICTRP, and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to 29 November 2021.

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of primary‐level and/or community health worker interventions for promoting mental health and/or preventing mental disorders versus any control conditions in adults and children in LMICs.

Data collection and analysis

Standardized mean differences (SMD) or mean differences (MD) were used for continuous outcomes, and risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous data, using a random‐effects model. We analyzed data at 0 to 1, 1 to 6, and 7 to 24 months post‐intervention. For SMDs, 0.20 to 0.49 represented small, 0.50 to 0.79 moderate, and ≥ 0.80 large clinical effects. We evaluated the risk of bias (RoB) using Cochrane RoB2.

Main results

Description of studies

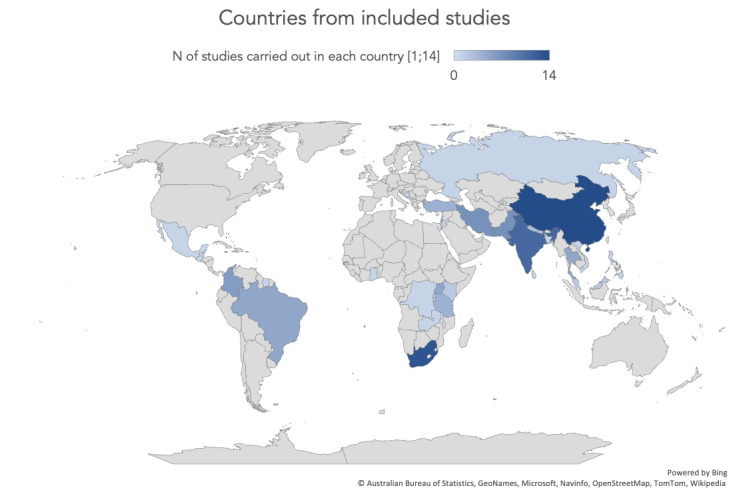

We identified 113 studies with 32,992 participants (97 RCTs, 19,570 participants in meta‐analyses) for inclusion. Nineteen RCTs were conducted in low‐income countries, 27 in low‐middle‐income countries, 2 in middle‐income countries, 58 in upper‐middle‐income countries and 7 in mixed settings. Eighty‐three RCTs included adults and 30 RCTs included children. Cadres of primary‐level workers employed primary care health workers (38 studies), community workers (71 studies), both (2 studies), and not reported (2 studies). Interventions were universal prevention/promotion in 22 studies, selective in 36, and indicated prevention in 55 RCTs.

Risk of bias

The most common concerns over risk of bias were performance bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias.

Intervention effects

'Probably', 'may', or 'uncertain' indicates 'moderate‐', 'low‐', or 'very low‐'certainty evidence.

*Certainty of the evidence (using GRADE) was assessed at 0 to 1 month post‐intervention as specified in the review protocol. In the abstract, we did not report results for outcomes for which evidence was missing or very uncertain.

Adults

Promotion/universal prevention, compared to usual care:

‐ probably slightly reduced anxiety symptoms (MD ‐0.14, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.27 to ‐0.01; 1 trial, 158 participants)

‐ may slightly reduce distress/PTSD symptoms (SMD ‐0.24, 95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.08; 4 trials, 722 participants)

Selective prevention, compared to usual care:

‐ probably slightly reduced depressive symptoms (SMD ‐0.69, 95% CI ‐1.08 to ‐0.30; 4 trials, 223 participants)

Indicated prevention, compared to usual care:

‐ may reduce adverse events (1 trial, 547 participants)

‐ probably slightly reduced functional impairment (SMD ‐0.12, 95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.15; 4 trials, 663 participants)

Children

Promotion/universal prevention, compared to usual care:

‐ may improve the quality of life (SMD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.11; 2 trials, 803 participants)

‐ may reduce adverse events (1 trial, 694 participants)

‐ may slightly reduce depressive symptoms (MD ‐3.04, 95% CI ‐6 to ‐0.08; 1 trial, 160 participants)

‐ may slightly reduce anxiety symptoms (MD ‐2.27, 95% CI ‐3.13 to ‐1.41; 1 trial, 183 participants)

Selective prevention, compared to usual care:

‐ probably slightly reduced depressive symptoms (SMD 0, 95% CI ‐0.16 to ‐0.15; 2 trials, 638 participants)

‐ may slightly reduce anxiety symptoms (MD 4.50, 95% CI ‐12.05 to 21.05; 1 trial, 28 participants)

‐ probably slightly reduced distress/PTSD symptoms (MD ‐2.14, 95% CI ‐3.77 to ‐0.51; 1 trial, 159 participants)

Indicated prevention, compared to usual care:

‐ decreased slightly functional impairment (SMD ‐0.29, 95% CI ‐0.47 to ‐0.10; 2 trials, 448 participants)

‐ decreased slightly depressive symptoms (SMD ‐0.18, 95% CI ‐0.32 to ‐0.04; 4 trials, 771 participants)

‐ may slightly reduce distress/PTSD symptoms (SMD 0.24, 95% CI ‐1.28 to 1.76; 2 trials, 448 participants).

Authors' conclusions

The evidence indicated that prevention interventions delivered through primary workers ‐ a form of task‐shifting ‐ may improve mental health outcomes. Certainty in the evidence was influenced by the risk of bias and by substantial levels of heterogeneity. A supportive network of infrastructure and research would enhance and reinforce this delivery modality across LMICs.

Keywords: Humans, Anxiety, Anxiety/diagnosis, Developing Countries, Health Promotion, Mental Disorders, Mental Disorders/prevention & control, Mental Health, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Primary‐level and community worker interventions for the prevention of mental disorders and the promotion of well‐being in low‐ and middle‐income countries

What is the main aim of this review? The aim of this Cochrane Review was to assess the effects of involving people in primary services and the community, such as nurses, midwives, teachers or caregivers, to promote mental health. The review focused on children and adults living in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

Key messages

The employment use of primary‐level and community workers may improve the mental health of adults and children living in low‐ and middle‐income countries. However, more evidence is needed.

What was studied in this review? Many people who would benefit from mental health support cannot access these services. One reason for this is a lack of specialized mental healthcare staff. This is especially true in low‐ and middle‐income countries. To overcome this barrier, people without a professional background in mental health, such as nurses or teachers, can be trained to deliver some mental health services. In our review, we investigated whether this strategy helps to promote mental health and prevent mental disorders amongst adults and children. We also assessed its costs.

What are the main results of this review?

We included 113 studies from a range of low‐ and middle‐income countries.

The studies assessed the effects of services carried out by primary‐level and community workers on people's mental health, quality of life, and social outcomes.

We grouped interventions depending on their overall objectives. Specifically, we refer to those targeting the whole population as 'promotion/universal prevention', those targeting people at risk for developing a mental disorder as 'selective prevention', and those designed for already presenting some sign of mental disorders as 'indicated prevention'. Below we report evidence of the results of low to moderate‐certainty, directly after the intervention. We did not present results for outcomes for which there was no or very uncertain evidence.

Promotion/universal prevention interventions, compared to usual care:

‐ probably slightly reduced anxiety symptoms in adults

‐ may slightly reduce distress/PTSD symptoms in adults

‐ may improve the quality of life of children

‐ may reduce adverse events in children

‐ may slightly reduce depression symptoms in children

‐ may slightly reduce anxiety symptoms in children

Selective prevention interventions, compared to usual care:

‐ probably slightly reduced depressive symptoms in adults

‐ may slightly reduce functional impairment in children

‐ probably slightly reduced depressive symptoms in children

‐ may slightly reduce anxiety symptoms in children

‐ probably slightly reduced distress/PTSD symptoms in children

Indicated prevention interventions,compared to usual care:

‐ may reduce adverse events in adults

‐ probably slightly reduced functional impairment in adults

‐ decreased slightly functional impairment in children

‐ decreased slightly depressive symptoms in children

‐ may slightly reduce distress/PTSD symptoms in children

Indicated prevention interventions delivered through task‐shifting may improve mental health outcomes.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

The limitations of the evidence in this review stem from the absence of assessments related to the reduction in the incidence of mental disorders in the prevention studies, and the lack of discernible differences in acceptability. Furthermore, the limited number of randomized controlled trials reporting our secondary outcomes, and their low quality, failed to demonstrate clinically significant advantageous effects of the studied prevention interventions for some outcomes in both child and adult populations.

How up‐to‐date is the review?

Review authors searched databases up to November 2021 to find and include all relevant published and unpublished trials.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table ‐ Promotion/universal prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in adults.

| Promotion/universal prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: preventing mental disorders Setting: low‐and middle‐income countries (China (1 study), Suriname (1 study), Malaysia (1 study), Jamaica (1 study), South Africa (1 study), Pakistan (1 study), Grenada (1 study)) Intervention: promotion/universal prevention interventions Comparison: control group | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control group | Risk with promotion/universal prevention interventions | |||||

| Diagnosis of mental disorders at study endpoint | No studies that measured this outcome were identified. | (0 studies) | ‐ | |||

| Quality of life at study endpoint (higher score = better quality of life) | ‐ | SMD 0.23 SD lower (0.51 lower to 0.04 higher) | ‐ | 684 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.23 (95% CI ‐0.51 to 0.04). It is uncertain whether promotion/universal prevention interventions have any effect on quality of life among adults without risk factors for mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared with usual care [there is a small effect according to Cohen 1992].1 |

| Adverse events at study endpoint | No studies that measured this outcome were identified. | (0 studies) | ‐ | |||

| Psychological functioning and impairment at study endpoint | No studies that measured this outcome were identified. | (0 studies) | ‐ | |||

| Depressive symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity ) | ‐ | SMD 0.31 SD lower (0.78 lower to 0.15 higher) | ‐ | 349 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd,e,f | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.31 (95% CI ‐0.78 to 0.15). It is uncertain whether promotion/universal prevention interventions have any effect on depressive symptoms in adults without risk factors for mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care [this is a small effect according to Cohen 1992].1 |

| Anxiety symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | The mean anxiety symptoms at study endpoint was 0 | MD 0.14 lower (0.27 lower to 0.01 lower) | ‐ | 158 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateg | Promotion/universal prevention interventions for adults without risk factors for mental disorders probably slightly reduce anxiety symptoms (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care [there is a small effect according to Cohen 1992].1 |

| Distress/PTSD symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | ‐ | SMD 0.24 SD lower (0.41 lower to 0.08 lower) | ‐ | 722 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowh,i | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.24 (95% CI ‐0.41 to ‐0.08). Promotion/universal prevention interventions may slightly reduce distress/PTSD symptoms in adults without risk factors for mental disorders (at post‐intervention) comparedto usual care [there is a small effect according to Cohen 1992].1 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_429913845297007331. | ||||||

a Downgraded 2 levels owing to study limitations (over 30% of RCTs have overall high risk of bias) b Downgraded 1 level owing to inconsistency (I2 between 50% and 75% (P = 0.05)) c Downgraded 2 levels owing to indirectness (participants with 17‐20 years of age for Duan 2019; outcome measures as proxy of quality of life for Duan 2019 and Hendricks 2019) d Downgraded 1 level owing to study limitations (23% of RCTs had overall high risk of bias. Over 30% of RCTs had overall some concerns.) e Downgraded 2 levels owing to inconsistency (I2 was 75%, point estimates vary across studies) f Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (participants with 17‐20 years of age for Duan 2019; unclear age for Yusoff 2015) g Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (outcome based on a small number of participants, less than 200) h Downgraded 1 level owing to study limitations (over 30% of studies had some concerns due to deviations from intended interventions and in selection of the reported result) i Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (participants with 17‐20 years of age for Duan 2019; outcome measures as proxy of distress for Baker‐Henningham 2019) 1 J, Cohen. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin ; 1992.

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table ‐ Selective prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in adults.

| Selective prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: preventing mental disorders Setting: low‐ and middle‐income countries (Thailand (1 study), Lebanon (1 study), Iran (2 studies), Jamaica (1 study), Pakistan (1 study), The Gambia (1 study)) Intervention: selective prevention interventions Comparison: control group | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control group | Risk with selective prevention interventions | |||||

| Diagnosis of mental disorders at study endpoint | No studies that measured this outcome were identified. | (0 studies) | ‐ | |||

| Quality of life at study endpoint (higher score = better quality of life) | ‐ | SMD 1.64 lower (2.97 lower to 0.31 lower) | ‐ | 229 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐1.64 (95% CI ‐2.97 to ‐0.31). It is uncertain whether selective prevention interventions have any effect on quality of life among adults with risk factors for mental disorders/lack of protective factors (at post‐intervention) compared with usual care. [There is a large effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Adverse events at study endpoint | No studies that measured this outcome were identified. | (0 studies) | ‐ | |||

| Psychological functioning and impairment at study endpoint | No studies that measured this outcome were identified. | (0 studies) | ‐ | |||

| Depressive symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | ‐ | SMD 0.69 lower (1.08 lower to 0.3 lower) | ‐ | 223 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderated | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.69 (95% CI ‐1.08 to ‐0.3). Selective prevention interventions for adults with risk factors for mental disorders/lack of protective factors probably slightly reduce depressive symptoms (at post‐intervention)compared to usual care. [There is a medium effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Anxiety symptoms at study endpoint | No studies that measured this outcome were identified. | (0 studies) | ‐ | |||

| Distress/PTSD symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | ‐ | SMD 0.9 lower (1.44 lower to 0.36 lower) | ‐ | 535 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,e | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.90 (95% CI ‐1.44 to ‐0.36). It is uncertain whether selective prevention interventions have any effect on distress/PTSD symptoms in adults with risk factors for mental disorders/lack of protective factors (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a large effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_429913907887557578. | ||||||

a Downgraded 2 level owing to inconsistency (I2 was higher than 75%, P < 0.00001) b Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of quality of life) c Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (outcome based on a small number of participants) d Downgraded 1 level owing to study limitations (over 20% of RCTs have overall high risk of bias, and all others RCTs have overall some concerns) e Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of distress) 1 J, Cohen. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin ; 1992.

Summary of findings 3. Summary of findings table ‐ Indicated prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in adults.

| Indicated prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in adults | ||||||

| Patient or population: preventing mental disorders Setting: low‐ and middle‐income countries (Turkey, Iran (2 studies), China (4 studies), Malaysia, Guatemala, India (3 studies), Bosnia and Herzegovina, Brazil (3 studies), Vietnam, South Africa (3 studies), Tanzania, Kenya, Nepal, Burundi, Jamaica (2 studies), Ghana, Philippines) Intervention: indicated prevention interventions Comparison: control group | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control group | Risk with indicated prevention interventions | |||||

| Diagnosis of mental disorders at study endpoint (RR < 1 denotes lower risk of mental diagnosis) | 170 per 1000 | 51 per 1000 (10 to 267) | RR 0.30 (0.06 to 1.57) | 843 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c,d | It is uncertain whether indicated prevention interventions have any effect on the risk of mental disorders in adults with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. |

| Quality of life at study endpoint (higher score = better quality of life) | ‐ | SMD 0.36 lower (0.61 lower to 0.12 lower) | ‐ | 1136 (8 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowe,f | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.36 (95% CI ‐0.61 to ‐0.12). It is uncertain whether indicated prevention interventions have any effect on quality of life among adults with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared with usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Adverse events at study endpoint | Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowg,h | Indicated prevention interventions may reduce adverse events in adults with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. |

| Psychological functioning and impairment at study endpoint (higher score = higher disability) | ‐ | SMD 0.12 lower (0.39 lower to 0.15 higher) | ‐ | 663 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatei | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.12 (95% CI ‐0.39 to 0.15). Indicated prevention interventions for adults with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders probably slightly reduce functional impairment (at post‐intervention)compared to usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Depressive symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | ‐ | SMD 0.16 lower (0.3 lower to 0.03 lower) | ‐ | 2341 (18 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowj,k,l | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.16 (95% CI ‐0.3 to ‐0.03). It is uncertain whether indicated prevention interventions have any effect on depressive symptoms in adults with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Anxiety symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | ‐ | SMD 1.19 lower (2.02 lower to 0.35 lower) | ‐ | 250 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowm,n | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐1.19 (95% CI ‐2.02 to ‐0.035). It is uncertain whether indicated prevention interventions have any effect on depressive symptoms in adults with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a large effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Distress/PTSD symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | ‐ | SMD 0.54 lower (0.95 lower to 0.14 lower) | ‐ | 2536 (19 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowl,n | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.54 (95% CI ‐0.95 to ‐0.14). It is uncertain whether indicated prevention interventions have any effect on distress/PTSD symptoms in adults with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a medium effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_429913973563280333. | ||||||

a Downgraded 2 levels owing to study limitations (over 30% of RCTs had high risk of bias due to missing outcome data and in selection of the reported result) b Downgraded 2 levels owing to inconsistency (I2 was higher than 75%, point estimates vary widely across studies) c Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of diagnosis of mental disorders) d Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (outcome based on wide confidence interval ranged from favouring Indicated Prevention Intervention to no clinical effect) e Downgraded 2 levels owing to inconsistency (I2 was higher than 75%, P = 0.003) f Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of quality of life) g Downgraded 1 level owing to publication bias (only 1 "negative" RCT) h Downgraded 1 level owing to study limitations i Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of psychological functioning and impairment) j Downgraded 1 level owing to study limitations (all RCTs had some concerns in measurement of the outcome; over 10% of studies had high concerns due to deviations from intended interventions) k Downgraded 1 level owing to inconsistency (I2 between 50% and 75%, P = 0.002) l Downgraded 1 level owing to publication bias (funnel plot suggests high asymmetry: RCTs expected in the bottom right quadrant are missing) m Downgraded 1 level owing to study limitations (over 30% of RCTs had some concerns due to deviations from intended interventions and in measurement of the outcome) n Downgraded 2 levels owing to study limitations (over 30% of RCTs had some concerns due to deviations from intended interventions and in measurement of the outcome) 1 J, Cohen. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin ; 1992.

Summary of findings 4. Summary of findings table ‐ Promotion/universal prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in children.

| Promotion/universal prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in children | ||||||

| Patient or population: preventing mental disorders Setting: low‐ and middle‐income countries (Brazil (1 study), Uganda (1 study), Mexico (1 study), Tanzania (1 study), Mauritius (1 study), Iran (1 study)) Intervention: promotion/universal prevention interventions Comparison: control group | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control group | Risk with promotion/universal prevention interventions | |||||

| Diagnosis of mental disorders at study endpoint | No studies that measured this outcome were identified. | (0 studies) | ‐ | |||

| Quality of life at study endpoint (higher score = better quality of life) | ‐ | SMD 0.25 SD lower (0.39 lower to 0.11 lower) | ‐ | 803 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.25 (95% CI ‐0.39 to ‐0.11). Promotion/universal prevention interventions may improve the quality of life of children without risk factors for mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Adverse events at study endpoint (RR < 1 indicates lower risk of adverse events) | Not pooled | Not pooled | Not pooled | (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,d | Promotion/universal prevention interventions may reduce adverse events in children without risk factors for mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care |

| Psychological functioning and impairment at study endpoint (higher score = higher disability) | ‐ | SMD 0.04 higher (0.9 lower to 0.98 higher) | ‐ | 212 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,e,f,g | Scores estimated based on an SMD of 0.04 (95% CI ‐0.9 to 0.98). It is uncertain whether promotion/universal prevention interventions have any effect on functional impairment in children without risk factors for mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Depressive symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | MD 3.04 SD lower (6 lower to 0.08 lower) | ‐ | 160 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,h | Promotion/universal prevention interventions may slightly reduce depression symptoms in children without risk factors for mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a large effect according to Cohen 1992]1 | |

| Anxiety symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | MD 2.77 higher (3.13 lower to 1.41 lower) | ‐ | 183 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,h | Promotion/universal prevention interventions may slightly reduce anxiety symptoms in children without risk factors for mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a medium effect according to Cohen 1992]1 | |

| Distress/PTSD symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | ‐ | SMD 0.83 SD lower (2.48 lower to 0.82 higher) | ‐ | 800 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowi,j,k,l | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.83 (95% CI ‐2.48 to 0.82). It is uncertain whether promotion/universal prevention interventions have any effect on distress/PTSD symptoms in children without risk factors for mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a large effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_429913294102284283. | ||||||

a Downgraded 1 level owing to study limitations (all RCTs had some concerns for the deviations from the intended interventions and in measurement of the outcome) b Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of quality of life) c Downgraded 1 level owing to study limitations (RCT had some concerns for the deviations from the intended interventions and in measurement of the outcome) d Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (0 total events) e Downgraded 2 levels owing to inconsistency (I2 was higher than 75%, point estimates vary widely across RCTs, and CIs show minimal overlap) f Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of psychological functioning and impairment) g Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (outcome based on wide confidence interval that included no effect and appreciable benefit and harm) h Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (outcome based on a small number of participants, less than 200) i Downgraded 2 level owing to study limitations (over 30% of RCTs had high risk of bias due to deviations from the intended interventions and missing outcome data) j Downgraded 2 levels owing to inconsistency (I2 was higher than 75%, P < 0.00001, point estimates vary widely across studies, and CIs show no overlap) k Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of distress) l Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (wide confidence interval ranged from favouring promotion/prevention intervention to no clinical effect) 1 J, Cohen. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin ; 1992.

Summary of findings 5. Summary of findings table ‐ Selective prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in children.

| Selective prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in children | ||||||

| Patient or population: preventing mental disorders Setting: low‐ and middle‐income countries (Uganda (1 study), Thailand (1 study), Democratic Republic of Congo (1 study), Brazil (1 study)) Intervention: selective prevention interventions Comparison: control group | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control group | Risk with selective prevention interventions | |||||

| Diagnosis of mental disorders at study endpoint | No studies that measured this outcome were identified. | (0 studies) | ‐ | |||

| Quality of life at study endpoint (higher score = better quality of life) | MD 1.1 higher (3.32 lower to 1.12 higher) | ‐ | 115 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b | It is uncertain whether selective prevention interventions have any effect on quality of life among children with risk factors for mental disorders/lack of protective factors (at post‐intervention) compared with usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 | |

| Adverse events at study endpoint | No studies that measured this outcome were identified. | (0 studies) | ‐ | |||

| Psychological functioning and impairment at study endpoint (higher score = higher disability) | MD 0.02 higher (0.09 lower to 0.05 higher) | ‐ | 479 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowc,d | There is no evidence that selective prevention interventions improve functional impairment in children with risk factors for mental disorders/lack of protective factors (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. 1 | |

| Depressive symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | ‐ | SMD 0 SD (0.16 lower to 0.15 higher) | ‐ | 638 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderated | Scores estimated based on an SMD of 0.0 (95% CI ‐0.16 to 0.15). Selective prevention interventions for children with risk factors for mental disorders/lack of protective factors probably slightly reduce depressive symptoms (at post‐intervention)compared to usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Anxiety symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | MD 4.5 higher (12.05 lower to 21.05 higher) | ‐ | 28 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowe | Selective prevention interventions may make little or no difference to anxiety symptoms in children with risk factors for mental disorders/lack of protective factors (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. 1 | |

| Distress/PTSD symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | MD 2.14 lower (3.77 lower to 0.51 lower) | ‐ | 159 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderateb | Selective prevention interventions for children with risk factors for mental disorders/ lack of protective factors probably slightly reduce distress/PTSD symptoms (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; MD: mean difference; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_429913697396673091. | ||||||

a Downgraded 2 levels owing to study limitations (over 30% of RCTs had high risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions and missing outcome data, in measurement of the outcome, and in selection of the reported result) b Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (outcome based on a small number of participants, less than 200) c Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of psychological functioning and impairment) d Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (confidence interval ranged from favouring selective prevention intervention to no clinical effect) e Downgraded 2 levels owing to imprecision (outcome based on a small number of participants, less than 200, and confidence interval ranged from favouring selective prevention intervention to no clinical effect) 1 J, Cohen. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin ; 1992.

Summary of findings 6. Summary of findings table ‐ Indicated prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in children.

| Indicated prevention interventions compared to control group in preventing mental disorders in children | ||||||

| Patient or population: preventing mental disorders Setting: low‐ and middle‐income countries (China (1 study), Tanzania (1 study), Kenya (1 study), Sri Lanka (1 study), Belize (1 study)) Intervention: indicated prevention interventions Comparison: control group | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with control group | Risk with indicated prevention interventions | |||||

| Diagnosis of mental disorders at study endpoint (RR < 1 denotes lower risk of mental diagnosis) | 336 per 1000 | 259 per 1000 (171 to 393) | RR 0.77 (0.51 to 1.17) | 220 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | It is uncertain whether indicated prevention interventions have any effect on the risk of mental disorders in children with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. |

| Quality of life at study endpoint (higher score = better quality of life) | ‐ | SMD 0.65 SD lower (2.09 lower to 0.79 higher) | ‐ | 152 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowd,e,f | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.65 (95% CI ‐2.09 to 0.79). It is uncertain whether indicated prevention interventions have any effect on quality of life among children with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared with usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Adverse events at study endpoint | No studies that measured this outcome were identified. | (0 studies) | ‐ | |||

| Psychological functioning and impairment at study endpoint (higher score = higher disability) | ‐ | SMD 0.29 SD lower (0.47 lower to 0.1 lower) | ‐ | 448 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.29 (95% CI ‐0.47 to ‐0.1). Indicated prevention interventions decrease slightly functional impairment in children with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is [a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Depressive symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | ‐ | SMD 0.18 SD lower (0.32 lower to 0.04 lower) | ‐ | 771 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.18 (95% CI ‐0.32 to ‐0.04). Indicated prevention interventions decrease slightly depressive symptoms in children with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Anxiety symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | ‐ | SMD 0.09 lower (0.22 lower to 0.04 higher) | ‐ | 888 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowg,h | Scores estimated based on an SMD of ‐0.09 (95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.04). It is uncertain whether indicated prevention interventions have any effect on anxiety symptoms in children with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| Distress/PTSD symptoms at study endpoint (higher score = higher severity) | ‐ | SMD 0.24 SD higher (1.28 lower to 1.76 higher) | ‐ | 448 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowi,j | Scores estimated based on an SMD of 0.24 (95% CI ‐1.28 to 1.76). Indicated prevention interventions may slightlyreduce distress/PTSD symptoms in children with a high vulnerability to develop mental disorders (at post‐intervention) compared to usual care. [There is a small effect according to Cohen 1992]1 |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_429913780370754267. | ||||||

a Downgraded 1 level owing to study limitations (RCT did not provided information about allocation concealment, and outcome assessment was not described as masked) b Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of depression) c Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (outcome based on wide confidence interval ranging from favouring indicated prevention intervention to no clinical effect) d Downgraded 2 levels owing to study limitations (over 30% of RCTs had high risk in selection of the reported result) e Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of quality of life) f Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (outcome based on a small number of participants, less than 200) g Downgraded 2 levels owing to study limitations (over 30% of RCTs had high risk of bias due to deviations from intended interventions and missing outcome data) h Downgraded 1 level owing to indirectness (outcome measures as proxy of anxiety) i Downgraded 1 level owing to inconsistency (point estimates vary widely across studies) j Downgraded 1 level owing to imprecision (outcome based on wide confidence interval that included no effect and appreciable benefit and harm) 1 J, Cohen. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin ; 1992.

Background

Description of the condition

Worldwide, the global burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders is high. The latest global burden of disease studies estimated that mental, behavioural, and neuropsychiatric disorders are amongst the top 30 causes of all years lived with disability; the highest contributors are anxiety and depressive disorders, drug use disorders, and alcohol use disorders (Kyu 2018; Murray 2020; Santomauro 2021). Mental health and behavioural disorders contribute 7.4% of the global burden of disease in the world ‐ more than, for example, tuberculosis (2%), HIV/AIDS (3.3%), or malaria (4.6%) (Whiteford 2013). The contribution of major depressive disorders alone to worldwide disability‐adjusted life‐years (DALYs) increased by 37% between 1990 and 2010 and is predicted to rise further (Murray 2012; Prince 2007). In addition, self‐inflicted injuries and alcohol‐related disorders are likely to increase in the ranking of disease burden due to the decline in communicable diseases and because of a predicted increase in war and violence. The disease burden due to Alzheimer’s disease is also increasing; this is linked to the demographic transition towards an ageing population (Vos 2012). Despite these figures, levels of public expenditure on mental health are still low (a global median of 2.1% of government health expenditure) and particularly meagre in lower resource settings. Data from official WHO reports highlight persistent gaps in the availability of mental health resources, significant variation between high‐ and low‐income countries and across regions, and the need for continued country‐level investment in policies, plans, health services, and monitoring systems for mental health care (WHO 2021a).

Political instability, war, and natural disasters disproportionally affect populations living in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) (Guha‐Sapir 2014). In addition, people living in these contexts, are more prone to experiencing extreme chronic poverty (less than 1.90 international dollars per day), which causes about 385 million of children under the age of 18 years to experience severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, water, sanitation, health, and education. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that the prevalence of post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and mixed anxiety disorders in conflict settings is at 22% (Charlson 2019), which is, conservatively, around five times higher than the general population. The COVID‐19 pandemic is an additional public health emergency that occurred against an already complex backdrop of psychological suffering. It further affected social determinants of mental health, also rasing concerns about the deprioritization of the psychological needs of people in LMICs. Risk factors for mental disorders and increased symptomatology can include community‐level risk factors (e.g. neighbourhood disadvantages, high levels of community violence, community‐level gender inequitable norms), family‐level risk factors (e.g. intimate partner violence, harsh parenting), or individual‐level risk factors (e.g. low self‐esteem, maladaptive coping strategies). Similarly, protective factors can operate at multiple levels of the social environment. Promotion interventions may target promotive factors (i.e. factors associated with an increased chance of achieving positive mental health states).

These illnesses also imply substantial economic costs. One recent report on the global economic burden of non‐communicable diseases (NCDs) suggests that, by the early 2030s, mental health conditions alone will account for the loss of an additional USD 16.1 trillion, with a dramatic impact on productivity and quality of life (Bloom 2011). Data on the macroeconomic costs for LMIC settings remain uncertain (Hu 2006). However, the economic and social costs for individuals and families are substantial. High direct costs are incurred in countries where health spending is met largely through private, as opposed to public, spending, and where health insurance and employer‐met health payments are insubstantial (Patel 2007b). High indirect costs are incurred as the result of informal caregiving and lost work opportunities, as well as untreated disorders and their associated disabilities (Chisholm 2000).

All over the world, the gap between individuals in need of mental health interventions and those who actually receive such care is very large (WHO 2018). Previous estimates suggest that more than 56% of people with depression (De Silva 2014; Kohn 2004; Lora 2012; Patel 2010), along with 78% of persons with alcohol use disorders (Kohn 2004), do not receive care. A study of 21 countries via the WHO Mental Health Surveys found that 52.6% of persons with depressive disorders in LMICs had received no treatment in the past 12 months, and only 20.5% of persons with depressive disorders had received minimally adequate treatment (Thronicroft 2016). Major barriers to closing the treatment gap include scarcity of skilled human resources, large inequities and inefficiencies in resource distribution and utilization, and the significant stigma associated with mental health conditions (Barber 2019). Recent studies report the existence of a range of cost‐effective interventions in mental health care available that can be implemented in LMICs (Barbui 2020; Purgato 2018a). The global mental health community, therefore, advocates for the scaling‐up of these evidence‐based services, that focus on task‐shifting as a mean to bridge the treatment gap (Patel 2018).

Description of the intervention

A recent Lancet Commission sought to align global mental health efforts with sustainable development goals, and emphasized the importance of efforts to prevent mental health disorders and promote mental health, in addition to scaling‐up treatments (Patel 2018). Prevention and promotion of mental health have previously been advocated as critical by the WHO (WHO 2002), and prevention is part of the WHO Mental Health Action Plan (WHO 2013). Prevention and promotion efforts are an important complementary focus, in addition to the treatment of mental disorders, given that (1) many mental disorders have risk factors in the social environment (e.g. gender‐based violence, poverty) that can be effectively addressed; (2) there are limitations to the extent that treatments alone can reduce the burden associated with mental disorders (Freeman 2016); and (3) cost‐effective prevention and promotion interventions are available (Knapp 2011).

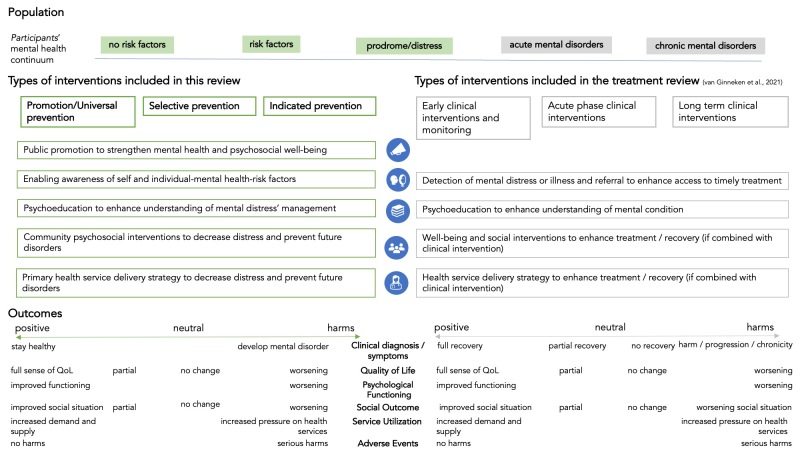

In the present review, we followed the classification of promotion and prevention interventions described by the Institute of Medicine (IOM) report on preventing mental disorders (Institute of Medicine 1994; Institute of Medicine 2009; National Academies of Sciences 2019).

Promotion is an approach aimed at strengthening positive aspects of mental health and psychosocial well‐being; it includes, for example, intervention components that foster pro‐social behaviour, self‐esteem, positive coping with stress, and decision‐making capacity (Table 7) (WHO 2014). The definition of promotion has been recently updated to include a wider set of interventions provided at societal, community, individual, and family levels. These updates reflect important trends in research in the field of public mental health and reveal the enduring importance of a spectrum of key tools for fostering mental health (National Academies of Sciences 2019).

1. Definitions.

| Adults | Participants who were ≥ 18 years old. If some studies had an age range from, for example, 16 years upwards, and a majority of participants (≥ 80%) were over 18 years of age, we included these study participants as adults. |

| Children and adolescents | Children (from birth to 18 years) were considered as a separate group of participants, as they have: • different patterns of psychopathology/mental disorders; and • different help‐seeking behaviours that would, therefore, require different interventions, in different settings (e.g. schools), and a different approach to interventions (e.g. worker interventions such as teacher‐led interventions). |

| Promotion | Promotion is an approach aimed at strengthening positive aspects of mental health and psychosocial well‐being; it includes, for example, components to foster prosocial behaviour, self‐esteem, positive coping with stress, and decision‐making capacity (National Academies of Sciences 2019; WHO 2014). Prevention is an approach aimed at reducing the likelihood of future disorder within the general population or amongst people who are identified as being at risk for developing a full‐blown disorder (Eaton 2012; Tol 2015a). |

| Universal prevention | Universal prevention includes strategies that can be offered to the whole population, based on evidence that prevention strategies are likely to provide some benefit to all (i.e. reduce the probability of a disorder), which clearly outweighs the costs and risks of negative consequences. Examples of common universal prevention interventions include:

|

| Selective prevention | Selective prevention refers to strategies that are targeted to subpopulations identified as being at elevated risk for a disorder; it includes:

|

| Indicated prevention | Indicated prevention includes strategies that are targeted to individuals who are identified (or individually screened) as having increased vulnerability for a disorder based on some individual assessment. These interventions include:

|

| First‐level care, primary care, and community care | First‐level contact with formal health services consists of community‐based interventions or primary care interventions (or both), on their own or attached to hospital settings, provided they had no specialist input apart from supervision (modified from Wiley‐Exley 2007). This would include promotion or prevention programmes in outpatient clinics or primary care practices. This would not include programmes in hospitals unless these programmes were providing prevention interventions to outpatients. Community programmes involve detection of mental disorders in all age groups, often done outside the health facility, for example, through school, training, and other community settings. |

| Low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs) | Any country that has ever been an LMIC, as defined by the World Bank lists of LMICs |

| Primary care health workers (PHWs) | Health workers who are not specializing in mental disorders or have not received in‐depth professional specialist training in this clinical area. They work in primary care centres or in the community. These individuals include doctors, nurses, auxiliary nurses, lay health workers, and allied health personnel such as social workers and occupational therapists. This category does not include professional specialist health workers such as psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, or mental health social workers. For inclusion, PHWs received some training in mental conditions (in the control group or in the intervention group), but this would not constitute a professional category. Study authors made a judgement of what constitutes ‘some training’. Examples of ‘some training’ may include an undergraduate module or a short course in mental health. |

| Community workers (CWs) | People involved as community‐level workers but who are not within the health sector, as many people, particularly adolescents and young adults, have limited contact with health workers. This category includes teachers/trainers/support workers from schools and colleges, along with other volunteers or workers within community‐based networks or nongovernmental organisations. These CWs have an important role, particularly in promotion of mental health and detection of mental disorders (Patel 2007b; Patel 2008). We excluded from this review studies that looked at informal care provided by family members or that extended care only to members of their own family (i.e. who were unavailable to other members of the community). As was previously highlighted in Lewin’s Cochrane Review, “these interventions are qualitatively different from other LHW [lay health worker] interventions included in this review given that parents or spouses have an established close relationship with those receiving care, which could affect the process and effects of the intervention” (Lewin 2010). |

| Primary‐level workers (PWs) | Broad term to encompass both CWs and PHWs |

CW: community worker LMIC: low‐ and middle‐income country PHW: primary‐level health worker PW: primary‐level worker

Prevention is an approach aimed at reducing the likelihood of future mental disorders in the general population or amongst people who are identified as being at risk for developing a full‐blown mental disorder (Eaton 2012; Purgato 2020; Tol 2015a). Prevention is further subdivided on the basis of the targeted population.

-

Universal prevention includes strategies that can be offered to the whole population based on evidence that prevention strategies are likely to provide some benefit to all (i.e. reduce the probability of disorder), which clearly outweighs the costs and risks of negative consequences. Examples of common universal prevention interventions include:

community‐wide provision of information on the negative effects of specific behaviours;

protection against human rights violations in the whole population (e.g. community mobilization to reduce gender‐based violence); and

community‐wide efforts to improve livelihood as a key protective factor for mental health (e.g. working on lifting restrictions on movement and employment for everyone in a refugee camp).

-

Selective prevention refers to strategies that target subpopulations identified as being at elevated risk for a disorder because they have known risk factors or lack protective factors. Examples include:

support for children whose parents have a mental illness;

strengthening of community networks for vulnerable families by activating social networks and supportive communication; and

stress management training in communities affected by chronic poverty.

-

Indicated prevention includes strategies that are targeted to individuals who are identified (or individually screened) as having increased vulnerability for a disorder based on some individual assessment of symptoms experienced but not meeting criteria for a full‐blown mental disorder. These interventions include but are not limited to:

mentoring programmes aimed at teachers and caregivers of children with behavioural problems; and

-

prevention of postnatal depression amongst women with heightened levels of prenatal symptoms (Institute of Medicine 2009) or interventions to prevent intimate partner violence (Turner 2020).

These interventions may be delivered at an individual level or at a group level and include antenatal and postnatal classes, parenthood classes, group interventions for managing distress, and continuity of care (home visits, follow‐ups) (O'Connor 2019; US Preventive Services Task Force 2019).

Primary healthcare workers (PHWs) are first‐level providers who have received general health rather than specialist training in mental health and can be based in a primary care clinic or in the community. It has been suggested that PWs (primary‐level workers) could deliver general and mental health interventions that are at least as effective and acceptable as those delivered by specialist health workers (Chatterjee 2003). In addition, PW interventions often have lower up‐front costs compared with those provided by professional specialist health workers. However, it is possible that these savings may be cancelled out by higher downstream resource use (Chisholm 2000). To address this concern, we aimed to include data on the costs and cost‐effectiveness of PW interventions. PHWs include professionals (mainly nurses, midwives, and other general health professionals) and para‐professionals (such as trained lay health providers, e.g. traditional birth attendants). PHWs do not include those with specialist mental health training, for example, psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, or mental health social workers with formal training. Community workers (CWs) are individuals who work in the community but not within the health sector. These might include teachers, trainers, support workers at schools and colleges, and other volunteers or workers within community‐based networks or non‐governmental organizations (NGOs). CWs are an additional human resource that can be widely deployed in delivering promotion and prevention interventions (Patel 2007a). In this review, both these categories of providers (PHWs and CWs) are referred to under the umbrella heading of primary‐level workers (PWs).

PWs have been deployed for a variety of services, including those delivered in governmental organizations, private clinics, halfway homes, schools, and other community settings. For example, PWs have been involved in supporting and befriending carers and in ensuring intervention adherence (Tol 2020). Nurses, social workers, and CWs may also take on follow‐up or educational/promotive roles (Araya 2003; Chatterjee 2003; Patel 2008). In addition, doctors with general mental health training have been involved in the identification, diagnosis, treatment, and referral of complex cases (Patel 2008).

A summary of the main definitions adopted in this review is provided in Table 7.

How the intervention might work

Prevention interventions commonly target known modifiable risk and protective factors for mental disorders.

Although a vast array of interventions can be implemented to meet a population's psychosocial needs, there are some common elements, especially when interventions target smaller groups or families. Many interventions include techniques from cognitive‐behavioural therapy (CBT) which work at stopping negative cycles, breaking down feelings and problems that generate psychological suffering, anxiety or depression into separate parts. This mechanism facilitates problem management and changes negative thought patterns, improving the way people feel (Hofmann 2017). CBT may comprise, for example, facilitated discussion, strengthening of social networks, space provided for sharing personal experiences and exchange of peer support, and opportunities to practice coping skills to manage adversity. Sessions on problem‐solving skills and emotional support Interventions may work by challenging participants to replace negative or critical self‐talk with compassionate, more constructive self‐talk, and to consider different viewpoints for managing problems (Hofmann 2017). Interventions may also consist of sessions with psychoeducational contents, strategies for stress management, enhanced insight and relationship/rapport building, networking support, communication skills, self‐help interventions, and motivational enhancement (Buntrock 2016; Panter‐Brick 2018).

In many LMICs, training and retaining sufficient numbers of mental health specialists to meet current needs is not feasible. Therefore, it is important in these settings to consider options for expanding access to mental health promotion and disorder prevention services. Given that they are far more numerous and often more accessible than mental health specialists, the deployment of PWs for this purpose is one option that could prove to be of value in LMICs. This review, therefore, focused on the evaluation of a task‐shifting model as a possible implementation modality for prevention and promotive interventions in LMICs.

Why it is important to do this review

This review is limited to LMICs, where the need for PWs is greater than in high‐income settings. Far fewer mental health professionals are present in LMICs (the median number of psychiatrists is 172 times lower in low‐income countries (LICs) than in high‐income countries (HICs)) (Kakuma 2011; WHO 2011b). These differences in the organization of mental health services between LMICs and HICs, with poorer countries having few or no mental health service structures in primary care or in the community, mean that the problem of providing mental health interventions, especially in preventing mental disorders or promoting psychological well‐being, is different in such settings. PWs may need to work with little or no support from specialist mental health services. Consequently, PW interventions might be expected to function differently in LMICs as compared to HICs (Cuijpers 2018; Purgato 2019a).

The paucity of mental health professionals and the abundance of challenges for mental health systems in LMICs make it imperative to focus attention on prevention and promotion strategies via a public health approach (Tol 2015a). To address current shortages of mental health workers, prevention interventions in LMICs have been conceived as short, simple, and mostly delivered through a task‐shifting approach that includes different forms of intervention delivery. Delivery strategies range from informal delivery of simple interventions to more complex and longer strategies, as stepped‐care models. Task‐shifting is increasingly emphasized in global mental health and holds promise for improving access to mental health interventions (Jensen 2018; Patel 2018).

However, reviews on the task‐shifting approach to mental health interventions in LMICs have tended to focus more on treatment interventions (Akhtar 2022; Purgato 2018a; Singla 2017; Van Ginneken 2021). Evidence on the effectiveness of mental health prevention and promotion interventions in LMICs is scarce. Systematic reviews have focused mainly on populations living in high‐income settings, raising applicability concerns related to contextual factors and resource availability, including, for example, the lack of professionals in low‐resource contexts (i.e. psychiatrists, and psychologists) (Barbui 2020). In addition, LMICs differ from HICs with regard to social determinants of mental health, e.g. exposure to conflicts and wars, poverty, and gender‐based violence may be more frequent in LMICs (Lund 2018).

Populations in LMICs can conceptualize and seek assistance for mental health problems and mental health promotion in a wide variety of ways; these approaches may differ from conceptualizations and help‐seeking patterns seen in high‐income industrialized countries. Thus, evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions implemented in HICs may not directly apply or be relevant to LMICs. For the reasons mentioned above, we expect that interventions might be applied differently in LMICs (Abdulmalik 2019).

The aim of this review is therefore to bridge this gap by assessing the effectiveness of delivery by primary workers of interventions for the promotion of mental health and for prevention of mental disorders or symptoms of mental illness in LMICs. Through this work, we aim to provide a picture of the characteristics and quality of the promotive and preventative research initiatives that have been carried out in lower resource settings. In addition, we strive to provide insights on what type of promotion strategies (universal, selective, and indicated) work best for whom (children and adults). This is overall in line with the WHO principle of integrating mental health into primary care and with the specific prevention objective of the WHO Action Plan for global mental health (WHO 2008; WHO 2021b).

This review has been conducted in parallel with an update of the Cochrane Review focused on treatment interventions in LMICs (Van Ginneken 2013; Van Ginneken 2021).

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of delivery by primary workers of interventions for the promotion of mental health and for prevention of mental disorders or symptoms of mental illness in LMICs.

To examine the impact of intervention delivery by primary workers on resource use and costs associated with the provision of mental health care in LMICs.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included RCTs. We included trials that employed a cross‐over design ‐ whilst we acknowledge that this design is rarely used in intervention studies ‐ and we used data from the first randomized stage only. We excluded quasi‐randomized trials, such as those that allocate participants by using alternate days of the week. We considered both individual and cluster‐randomized trials as eligible for inclusion.

We included economic studies conducted as part of included effectiveness studies. We considered full economic evaluations (cost‐effectiveness analyses, cost‐utility analyses, or cost‐benefit analyses), cost analyses, and comparative resource utilization studies. We planned to report only cost and resource usage outcomes from these studies.

Types of participants

Participants

We included participants of any age, gender, ethnicity, and religion. We conducted two separate meta‐analyses on the different outcomes ‐ one for children and adolescents (younger than 18 years) and one for adults (18 years of age and older). Studies with mixed population groups (children and adolescents; adults) were allocated according to the proportion of participants belonging to the child and adolescent age range, or to the adult age range. When the intervention was designed and directed to a specific population group (i.e. children and adolescents or adults), we entered outcome data on efficacy for the specific target group for which the intervention was designed and delivered. For each of these two populations, we conducted meta‐analyses by different outcomes. We included studies focused on the prevention of any common mental disorder. Carers of study participants were included in meta‐analyses on adults, as some interventions may be directed at carers rather than at participants themselves, and consequently, mental health outcomes were measured in carers.

Settings

We considered studies conducted in LMICs. We used the World Bank criteria for categorizing a country as low‐ or middle‐income (World Bank 2020); these criteria provide a historical date of when countries were LMICs. If a country was an LMIC at some point during the recruitment of study participants, we included the study. We excluded studies undertaken in high‐income countries (at the time of study recruitment).

We included mental health promotion and/or prevention interventions delivered in primary care or community settings, refugee camps, schools, communities, survivors’ homes, and detention facilities. We excluded studies evaluating mental health promotion and/or prevention interventions undertaken outside of primary or community settings.

Diagnoses

Given the focus on interventions for the promotion of mental health and prevention of mental disorders, we restricted this review to participants without any formal diagnosis at the time the trial was undertaken. However, because many studies screened on the basis of a risk factor or heightened symptoms (without excluding people with diagnosed mental disorders), we could not exclude trial participants who might have fulfilled the criteria for an actual psychiatric diagnosis that remained unobserved because it was not investigated when the trial was undertaken. For example, we included populations who left their homes due to a sudden impact, threat, or conflict; populations exposed to political violence/armed conflicts/natural and industrial disasters; those with major losses or in poverty; and those belonging to a group (i.e. discriminated against or marginalized) experiencing political oppression, family separation, disruption of social networks, destruction of community structures and resources and trust, increased gender‐based violence, and undermined community structures or traditional support mechanisms (IASC 2007).

Comorbidities

We included studies that recruited participants with physical disorders and studies that focused on the prevention of multiple mental disorders.

Types of interventions

Included interventions

We included trials of primary‐level and/or community health worker interventions for promoting mental health and/or preventing mental disorders. Included mental health promotion or prevention interventions were delivered by primary‐level and/or community workers. Primary‐level health workers (PHWs) are first‐level providers who have received general health rather than specialist mental health training and can be based in a primary care clinic or in the community. PHWs include professionals (doctors, nurses, midwives, and other general health professionals) and para‐professionals (such as trained lay health providers, e.g. traditional birth attendants). PHWs do not include those with specialist mental health training, for example, psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurses, or mental health social workers. Community workers (CWs) are individuals who work in the community but not within the health sector. These might include teachers, trainers, support workers from schools and colleges, and other volunteers or workers within community‐based networks or non‐governmental organizations (NGOs). These CWs are not trained health workers but have a mental health role. They represent a further human resource employed in the delivery of promotion and prevention interventions (Patel 2007a). In this review, both of these categories of providers (PHWs and CWs) were referred to under the umbrella heading of 'primary‐level workers' (PWs).

This review aimed to include the following comparisons.

Provision of promotion and/or prevention interventions by primary‐level health workers and/or community workers versus usual care (little prevention or promotion strategy).

Provision of promotion and/or prevention interventions by primary‐level health workers and/or community workers versus no prevention or promotion strategy.

Provision of promotion and/or prevention interventions by primary‐level health workers and/or community workers versus interventions delivered by professionals with specialist mental health training.

We grouped the interventions as follows.

Promotion of mental health (e.g. interventions with a mental health or psychological component aimed at creating living conditions and environments that support mental health and encourage healthy lifestyles). We included any types of promotion interventions with a mental health component, delivered at individual, group, family, community, and/or societal levels (National Academies of Sciences 2019).

Universal prevention (e.g. community‐wide provision of information on positive coping methods to help people feel safe and hopeful; to protect against human rights violations; and to support community‐wide efforts to reduce poverty as a key risk for mental illness) (IASC 2007).

Selective prevention (e.g. psychological first aid for people with heightened levels of psychological distress after exposure to severe stressors, loss, or bereavement). These interventions involve human, supportive, and practical help covering both a social and a psychological dimension. They work through communication (asking about people's needs and concerns; listening to people; and helping them to feel calm), practical support (i.e. providing meals or water); a psychological approach (including teaching stress management skills and helping people cope with problems) (WHO 2011a); facilitation of community support for vulnerable individuals by activating social networks and communication; and structured cultural and recreational activities supporting the development of resilience (Institute of Medicine 2009), such as traditional dancing, artwork, sports, and puppetry (Tol 2011).

Indicated prevention (e.g. mentoring programmes aimed at children with behavioural problems; psychosocial support for school children with subclinical levels of post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, depression, or somatic symptoms and related disorders; prevention of postnatal depression in women with heightened levels of prenatal symptoms) (Institute of Medicine 2009).

Interventions were delivered through any means, including, for example, face‐to‐face meetings, digital tools, radio, telephone, or self‐help booklets, between participants and PHWs. Both individual and group interventions were included, with no limit on the number of sessions.

As this review was conducted in parallel with the update of the Cochrane Review on treatment interventions (Van Ginneken 2013; Van Ginneken 2021), we looked at the aim of the study and decided whether the aim was prevention or treatment, and we looked at the inclusion criteria for participants (these criteria must include specific mental distress/prodromal symptoms or a diagnosable disorder). When there was no clear distinction between prevention and treatment groups, we made a pragmatic decision on whether these trials were primarily about well‐being/prevention or about treatment and then allocated them to the appropriate review, or included them in both reviews.

Excluded interventions

We excluded interventions aimed at treating people with a diagnosed mental disorder. We also excluded studies that included participants on the basis of scoring above a cut‐off on a symptom checklist, with the explicit authors' stated intention to identify people with mental disorders. We excluded interventions aimed at treating people with a diagnosed disorder (Van Ginneken 2021).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Diagnosis (or a proxy thereof, as assessed by scoring above a cut‐off for a screening tool) of mental disorders at study endpoint, determined according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) III (APA 1980), DSM‐III‐R (APA 1987), DSM‐IV‐TR (APA 2000), DSM‐V (APA 2013), International Classification of Diseases (ICD)‐10 (WHO 1992), or any other standardized criteria.

Diagnosis (or a proxy thereof, as assessed by scoring above a cut‐off for a screening tool) of mental disorders at 1 to 6 months post‐intervention.

Diagnosis (or a proxy thereof, as assessed by scoring above a cut‐off for a screening tool) of mental disorders at 7 to 24 months post‐intervention.

Quality of life.

Adverse events experienced during the intervention.

Secondary outcomes

Psychological functioning and impairment.

Changes in service utilisation and contact coverage, including admission rates to hospital whether related to mental disorder or not; attendance rates in regard to utilization of primary or community services; or increased demand and/or referral rates from the primary/community setting to a mental health specialist.

Changes in mental health symptoms captured on rating scales (i.e. depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, distress/PTSD symptoms).

Social outcomes (e.g. perception of social inclusion).

Resource use (for health services: personnel time allocated/number of consultations, other opportunity costs of the intervention, or other aspects of the health service; for participants: extra costs of travel, lost productivity, employment status, income, work absenteeism, retention, educational attainment).