Abstract

The PDCD1-encoded immune checkpoint receptor PD-1 is a key tumor suppressor in T cells that is recurrently inactivated in T cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (T-NHLs). The highest frequencies of PDCD1 deletions are detected in advanced disease, predicting inferior prognosis. However, the tumor-suppressive mechanisms of PD-1 signaling remain unknown. Here, using tractable mouse models for T-NHL and primary patient samples, we demonstrate that PD-1 signaling suppresses T cell malignancy by restricting glycolytic energy and acetyl coenzyme A (CoA) production. In addition, PD-1 inactivation enforces ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) activity, which generates extramitochondrial acetyl-CoA for histone acetylation to enable hyperactivity of activating protein 1 (AP-1) transcription factors. Conversely, pharmacological ACLY inhibition impedes aberrant AP-1 signaling in PD-1-deficient T-NHLs and is toxic to these cancers. Our data uncover genotype-specific vulnerabilities in PDCD1-mutated T-NHL and identify PD-1 as regulator of AP-1 activity.

Subject terms: Haematological cancer, Signal transduction, Cancer, Cancer metabolism

Wartewig et al. show that PDCD1 in T cell lymphoma restricts glycolytic energy and acetyl-CoA production. Inhibition of PD-1 signaling enforces ACLY activity and generates extramitochondrial acetyl-CoA for histone acetylation to enable AP-1 hyperactivation.

Main

T cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas (T-NHLs) represent a heterogeneous group of highly aggressive cancers that typically originate from mature CD4+ T cells1. The therapeutic options for these malignancies are limited, which is largely due to their ill-defined molecular pathogenesis1. However, recent genomic analyses of large cohorts of patients with T-NHL revealed numerous oncogenic, gain-of-function alterations in T cell antigen receptor (TCR) signaling pathways. In addition, PDCD1, which encodes the inhibitory immune receptor PD-1, emerged as a key tumor suppressor in T-NHL2. Inactivating mutations in PDCD1 predict an aggressive clinical phenotype, and they portend poor overall survival in patients2. In addition, anti-PD-1 checkpoint inhibitors have been correlated with the emergence of secondary T-NHLs in patients with other primary malignancies3,4. Moreover, clinical trials in patients with T-NHL have reported hyperprogression of individual T cell lymphomas, which were apparently still under PD-1 control, after anti-PD-1 treatment (NCT02631746 (refs. 5,6), NCT03075553 (ref. 7)). While all these clinical observations highlight the critical importance of inhibitory PD-1 signaling in T cell malignancies, the tumor-suppressive mechanisms of PD-1 remain unknown.

In non-transformed T cells, acute PD-1 engagement leads to inhibition of the (phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K))–AKT axis8, and persistent PD-1 signaling triggers T cell exhaustion, a dysfunctional state with specific metabolic and epigenetic characteristics9,10. In addition, RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis from primary human and murine PD-1-deficient T-NHLs2 demonstrates that these tumors are characterized by distinct gene expression that is presumably also shaped by epigenetic mechanisms. Nevertheless, the molecular link between PD-1 signaling and metabolic and epigenetic reprogramming during lymphomagenesis remains unclear.

Here, we identify PD-1 as a major gatekeeper for the oncogene-triggered metabolic switch to glycolysis. We show that PDCD1 mutations enforce the induction of key metabolic molecules for glucose uptake, metabolization and generation of energy carriers. In addition, PD-1 regulates ACLY, which uses extramitochondrial citrate to fuel acetyl-CoA pools for histone acetylation and enables aberrant AP-1 activity in the tumor cells. These AP-1-inducing mechanisms are hijacked in aggressive PD-1-deficient lymphomas but not in their PD-1-competent counterparts and link PD-1 signaling to epigenetic reprogramming in T-NHL.

Results

To dissect T cell lymphoma pathogenesis, we previously engineered a genetically controllable murine model of human T-NHL based on tamoxifen-inducible irreversible expression of the T-NHL oncogene ITK-SYK, which enforces strong oncogenic TCR signaling11, together with an enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) reporter in individual mature CD4+ T cells in vivo (ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 mice; for the experimental system, see Fig. 1a,b)11,12. While acute expression of interleukin (IL)-2-inducible T cell kinase (ITK)–spleen-associated tyrosine kinase (SYK) (together with eGFP) in otherwise unperturbed primary T cells can trigger lymphocyte proliferation for a few days, it is unable to induce overt malignancy, which requires the acquisition of additional genetic hits (Extended Data Fig. 1a)11,12. However, loss of the tumor-suppressor gene Pdcd1 is sufficient to enable immediate unrestricted clonal expansion of lymphomatous T cells upon single oncogene expression that is lethal to the host (Extended Data Fig. 1a)12. These cells can transmit the malignant disease to secondary recipients12. We leveraged this genetically tractable mouse model for human T-NHL to investigate the very early events of T cell transformation.

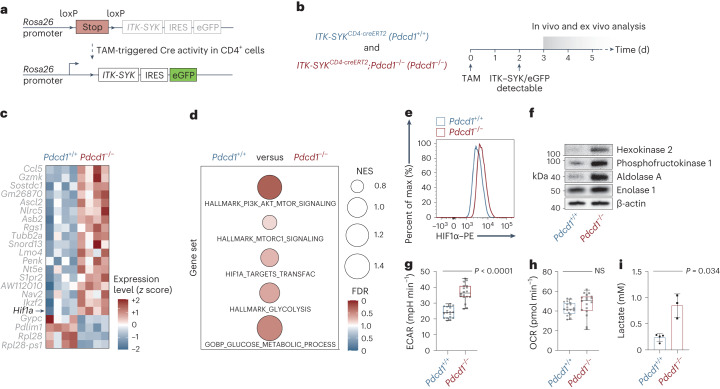

Fig. 1. Loss of Pdcd1 enables oncogene-enforced glycolysis in T cells.

a, Transgenic ITK-SYK allele with eGFP reporter sequence and Cre-induced excision of the stop cassette. IRES, internal ribosome entry site; TAM, tamoxifen. b, Experimental strategy to explore early molecular events upon ITK–SYK induction in the presence or absence of Pdcd1. c, Top 20 differentially expressed genes between ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 (‘Pdcd1+/+’)- and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− (‘Pdcd1−/−’)-derived ITK–SYK-expressing T cells. RNA-seq was performed using spleen-derived eGFP+ T cells, sorted by flow cytometry on day 5 after tamoxifen injection (n = 4 mice per group). Expression values are normalized z scores. d, GSEA of the indicated signatures. FDR, color intensity of circles; NES, circle diameter. Blue and red indicate the group in which the signature was positively enriched; NES, normalized enrichment score; FDR, false discovery rate. e, Flow cytometry for HIF1α in ITK–SYK-expressing T cells. Spleen-derived single-cell suspensions were generated from ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection. Max, maximum. f, Western blot analysis from lysates of ITK–SYK-expressing eGFP+ T cells, sorted by flow cytometry from ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection. g, ECAR metabolic flux analysis of ITK–SYK-expressing CD4+ T cells isolated from ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection (n = 3 biological replicates per group). Data were normalized using total cellular protein. P, two-sided Student’s t-test. Middle line denotes the median, the top and bottom box edges denote 0.25 and 0.75 quantiles, respectively, and the whiskers denote the minimum and maximum values. h, OCR metabolic flux analysis from the same experiment as in g. P, two-sided Student’s t-test. i, Lactate concentration in cell culture supernatants. ITK–SYK-expressing eGFP+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry from ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection and incubated overnight in vitro (n = 3 and n = 4 biological replicates per group). Data were normalized using viable cell numbers. P, two-sided Student’s t-test. Shown are the mean ± s.d. and individual data points. c,d, Data from one experiment. e,f, Representative data from two independent experiments with two biological replicates per group. g,h, Representative data from two independent experiments with three biological replicates per group. i, Representative data from two independent experiments.

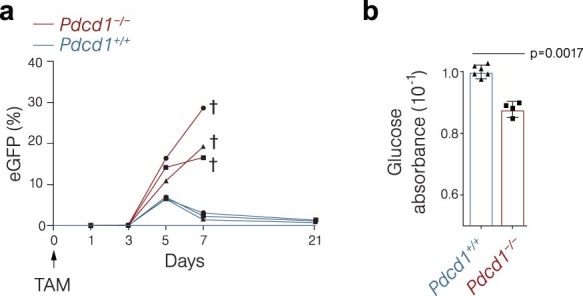

Extended Data Fig. 1. Increased glucose uptake upon Pdcd1 loss.

a, Percentage of eGFP-expressing cells as determined by flow cytometric analysis of peripheral blood. A cross indicates death of the animal. Individual data points are shown (n = 3 mice per genotype). TAM, tamoxifen. b, Remaining glucose in cell culture supernatants. ITK-SYK-expressing T cells were sorted by FACS for eGFP+ from the spleens of acutely induced ITK-SYKCD4-creERT2 (‘Pdcd1+/+’) and ITK-SYKCD4-creERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice (‘Pdcd1−/−‘) and cultured in vitro for four hours. Next, the cell culture supernatants were harvested, and glucose concentrations were determined by colorimetric measurements. All animals received single-dose intraperitoneal injections of tamoxifen five days before the experiment (n = 6 and n = 4 mice per genotype). Data was normalized to viable cell number. P=two-sided Student’s t-test. Shown are the mean ± SD and individual data points. a, Representative results from 8 independent experiments with three biological replicates per group. b, Representative results from 2 independent experiments.

Loss of Pdcd1 enables oncogene-enforced glycolysis

To identify the potent PD-1-controlled tumor-suppressor programs that prevent T cell transformation upon oncogenic T cell signaling, we induced ITK–SYK expression in vivo in primary CD4+ T cells with and without Pdcd1 by injecting tamoxifen into ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice. Three days after ITK–SYK expression, we purified oncogene-expressing cells by flow cytometry for RNA-seq. Among the top 20 differentially expressed genes, Hif1a, encoding a master regulator of cellular metabolism, was specifically upregulated in the absence of Pdcd1 (Fig. 1c; adjusted P < 0.0001). In addition, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed an enrichment of multiple gene expression signatures that indicate global activation of the PI3K–AKT–mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)–hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)1α axis13 upon PD-1 loss. Furthermore, enrichment of multiple gene expression signatures suggests enhanced glucose metabolism in the PD-1-deficient lymphoma cells compared to their premalignant ITK–SYK+PD-1+ counterparts (Fig. 1d). These gene expression data were corroborated by protein expression analysis of HIF1α and several enzymes that mediate glycolysis, including hexokinase 2, phosphofructokinase 1, aldolase A and enolase 1 in ex vivo isolated, acute oncogene-expressing T cells from tamoxifen-injected ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice (Fig. 1e,f)14,15.

Based on these findings, we next performed direct ex vivo functional analyses of glucose metabolism of acute ITK–SYK-expressing T cells with and without PD-1 function. Upon oncogenic T cell signaling, we detected enhanced glucose uptake in PD-1-deficient T cells compared to that of wild-type cells (Extended Data Fig. 1b; P = 0.0017). Moreover, extracellular flux analysis revealed a greater extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) in transformed ITK–SYK+PD-1− T cells than in their premalignant ITK–SYK+PD-1+ T cell counterparts, whereas the oxygen-consumption rate (OCR) remained unchanged (Fig. 1g,h; P < 0.0001 and P, not significant (NS)). Because the increase in ECAR implies aerobic glycolytic conversion of pyruvate to lactate, we next measured the production of this metabolite. Lactate generation was enhanced in the transformed ITK–SYK+PD-1− T cells compared to in their premalignant counterparts (Fig. 1i; P = 0.034). To study glucose metabolism in vivo, we used the glucose analog tracer [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]FDG) and positron emission tomography (PET). The maximum [18F]FDG uptake in individual mice was measured in the spleens of both ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 2a). The overall [18F]FDG uptake and maximum uptake in single voxels was significantly higher in ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− animals than in PD-1-proficient ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 mice, demonstrating augmented glucose uptake in vivo (Fig. 2b; P = 0.005). To measure glycolytic conversion, we infused hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate intravenously into tamoxifen-injected animals and compared [1-13C]lactate/[1-13C]pyruvate signal ratios in the spleens using hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRI)16. The [1-13C]lactate/[1-13C]pyruvate signal ratio was substantially higher in oncogene-expressing ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− animals than in ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 mice, confirming enhanced lactate production in vivo (Fig. 2c,d and Extended Data Fig. 2a,b; P = 0.0284).

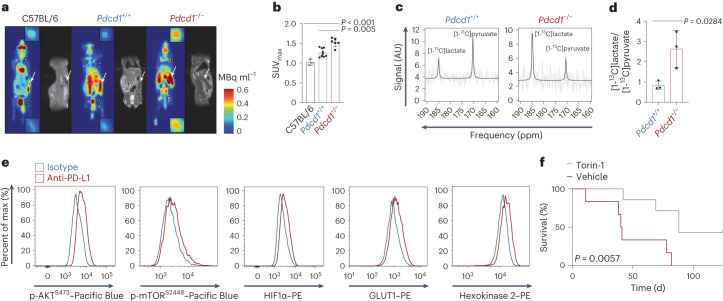

Fig. 2. PD-1 represses mTOR and HIF1α in premalignant cells.

a, Whole-body standardized uptake value (SUV) maps from [18F]FDG PET measurements of C57BL/6 mice, ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice together with anatomical MRI acquisition. The [18F]FDG PET measurements were conducted on day 5 after tamoxifen application. Magnified [18F]FDG PET signals from lymph nodes are shown (insets). White arrows indicate spleens. Color intensity represents the calculated uptake of [18F]FDG in units of MBq ml−1. b, SUVmax for the indicated genotypes (n = 3 for C57BL/6, n = 9 for Pdcd1+/+ and n = 6 for Pdcd1−/− mice) from the experiment shown in a. SUVmax denotes the maximum signal found in a single voxel across the entire tumor lesion. P, one-way ANOVA and two-sided Student’s t-test. Shown are the mean ± s.e.m. and individual data points. c, Exemplary 7-T MRI chemical shift imaging (CSI)-derived 13C magnetic resonance spectra showing [1-13C]pyruvate and [1-13C]lactate amplitudes in the splenic region of interest of ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice following injection of hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate on day 5 after tamoxifen injection. AU, arbitrary units. d, Ratio of [1-13C]pyruvate and [1-13C]lactate amplitudes in spleens measured by 7-T MRI in ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection (n = 3 mice per genotype). P, two-sided Student’s t-test. Shown are the mean ± s.d. and individual data points. e, Flow cytometry for p-AKTS473, p-mTORS2448, HIF1α, GLUT1 and hexokinase 2 in ITK–SYK-expressing T cells. Spleen-derived single-cell suspensions were generated from ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection. Before fixation, anti-PD-L1 or control antibodies were added for 4 h in vitro. f, Survival of ITK–SYK+PD-1− lymphoma-bearing NSG mice treated with torin-1 or vehicle. On day 0, NSG mice received 1,000 ITK–SYK-expressing eGFP+ cells from an ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mouse, sorted by flow cytometry on day 5 after tamoxifen injection. Mice received 6 mg per kg torin-1 or vehicle daily via intraperitoneal injection (n = 6 mice per group) from day 3 post tamoxifen on. P, two-sided log-rank test. a, Representative mice from two independent experiments. b, Pooled data from two independent experiments. c, Representative amplitudes from one experiment. d, Pooled data from two independent experiments. e, Representative data from two independent experiments with two biological replicates per group. f, Pooled data from two independent experiments.

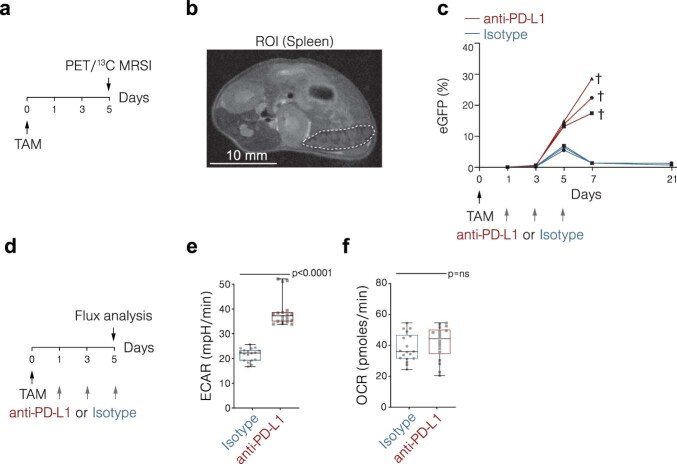

Extended Data Fig. 2. PD-1 inactivation enables oncogene-enforced glycolysis in vivo.

a, Schematic outline of metabolic imaging analysis experiment. b, Exemplary splenic T1-weighted sequence of an acutely induced ITK-SYKCD4-creERT2;Pdcd1−/− animals with indicated ROI used for 7T-MRI [1-13C]pyruvate and [1-13C]lactate measurements. ROI, region of interest. c, Percentage of viable lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of anti-PD-L1 or isotype control antibodies treated ITK-SYKCD4-creERT2 mice. All animals received a single dose of tamoxifen on day zero. Cross indicates death of the animal (n = 3 mice per genotype). d, Schematic outline of metabolic flux analysis experiment. e, ECAR metabolic flux analysis of ITK-SYK-expressing T cells FACS sorted for eGFP+ from the spleens of acutely induced ITK-SYKCD4-creERT2 mice. As indicated in (d), the mice received anti-PD-L1 or isotype control antibodies on days one, three and five via intraperitoneal injection (n = 3 biological replicates per group). Data was normalized using total cellular protein. ECAR, extracellular acidification rate. P=two-sided Student’s t-test. The data are shown as box plots, in which the middle line denotes the median, the top and bottom box edges denote the 0.25 and 0.75 quantiles, respectively, and the whiskers denote the minimum and maximum values. f, OCR metabolic flux analysis from the same experiment as in (e) OCR, oxygen consumption rate. P=two-sided Student’s t-test. b, Representative data from a single mouse within the experiment shown in Fig. 2c, d. c, Representative results from 5 independent experiments with three biological replicates per group. e,f, Representative data from two independent experiments with three biological replicates per group.

Altogether, these sets of genetically controlled in vivo and ex vivo experiments demonstrate that deficiency in PD-1 forces T cells with oncogenic signaling to adapt their metabolism to aerobic glycolysis. This is characteristic of the Warburg effect that promotes the initiation and progression of most cancer types17–19.

PD-1 represses mTOR and HIF1α in premalignant cells

To determine how PD-1 inactivation promotes glycolysis, we acutely blocked PD-1 function in ITK–SYK-expressing T cells with anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) checkpoint inhibitors as experimental tools in vivo or ex vivo. This strategy allowed us to control the inactivation of PD-1 signaling in oncogene-expressing T cells in a time-dependent manner. Similar to genetic deletion of Pdcd1, injection of anti-PD-L1 antibody into tamoxifen-treated ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 mice induced unrestricted expansion of oncogene-expressing T cells, which rapidly killed the host (Extended Data Fig. 2c)12. These acutely PD-1-inhibited cells also switched to glycolysis with an increase in ECAR and no change in their basal OCR (Extended Data Fig. 2d–f; P < 0.0001 and P, NS). Intracellular flow cytometric analysis directly after acute PD-1 blockade demonstrated that inactivation of the PD-1 signal resulted in prompt activation of the AKT and mTOR pathways within oncogene-expressing T cells (Fig. 2e) and in direct upregulation of HIF1α expression20. Furthermore, we observed an induction of HIF1α transcriptional targets, including the glucose transporter GLUT1 and hexokinase 2, which are rate-limiting factors for glucose uptake and glucose utilization, respectively, in normal and malignant lymphocytes (Fig. 2e)21. Thus, these key metabolic switches in premalignant cells are under the direct negative control of PD-1 tumor-suppressor signaling.

To test the dependency of fully transformed lymphomas with Pdcd1 deletion on the released mTOR–HIF1α–glycolysis cascade, we incubated ITK–SYK+PD-1− cells with small-molecule inhibitors of mTOR, HIF1α or glycolysis22,23. Direct inhibition of glycolysis with 2-deoxy-d-glucose (2-DG) reduced the production of lactate, similar results were observed with the inhibition of mTOR or HIF1α (Extended Data Fig. 3a–c), and all three treatments were toxic to PD-1-deficient lymphoma cells (Extended Data Fig. 3d–f). Moreover, treatment of ITK–SYK+PD-1− lymphoma-bearing mice with the mTOR inhibitor torin-1, which blocks mTOR activity within tumor cells in vivo (Extended Data Fig. 3g), significantly prolonged survival (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 3h; P = 0.0057). Together, these pharmacological studies demonstrate that glycolytic reprogramming is key for the transformation and survival of oncogene-expressing PD-1-deficient T cells.

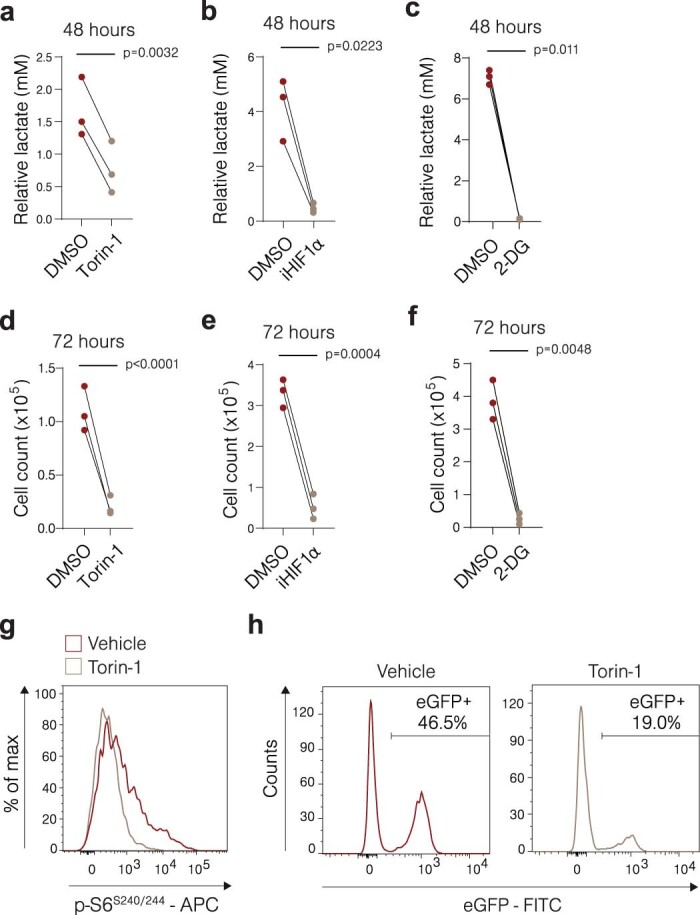

Extended Data Fig. 3. Transformed T cells with Pdcd1 deletion depend on the mTOR-HIF1α-glycolysis cascade.

a,b,c, Lactate concentrations in the cell culture supernatants of eGFP+ FACS sorted cells derived from the spleens of acutely induced ITK-SYKCD4-creERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice and incubated in vitro for 48 h in the presence of the mTOR inhibitor Torin-1 (a; 0.1 μM), HIF1α inhibitor PX-478 (b; iHIF1α, 5 μM) or glycolysis inhibitor 2-DG (c; 1 mM) or DMSO as a control (n = 3 biological replicates). Lactate concentrations were normalized to the viable cell numbers. P=paired two-sided Student’s t-test. d,e,f, Number of viable ITK-SYK+PD-1- cells cultured in vitro for 72 h with the mTOR inhibitor Torin-1 (d; 0.1 μM), HIF1α inhibitor PX-478 (e; iHIF1α, 5 μM) or glycolysis inhibitor 2-DG (f; 1 mM) or DMSO as a control (n = 3 biological replicates). eGFP+ T cells were sorted by FACS from acutely induced ITK-SYKCD4-creERT2;Pdcd1−/− animals (n = 3 biological replicates). P=paired two-sided Student’s t-test. g, Phosflow analysis of serine 240/244 of S6 ribosomal protein in ITK-SYK+PD-1- cells isolated from NSG mice treated with Torin-1 or vehicle. Cells were fixed and permeabilized immediately after isolation. h, eGFP percentage of viable lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of Torin-1 or vehicle-treated NSG mice, which were transplanted with 1,000 eGFP+ FACS-sorted ITK-SYK+PD-1- cells isolated from acutely induced ITK-SYKCD4-creERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice. Blood was taken seven days after initiation of treatment. a,b,c,d,e,f, Representative results from 2 independent experiments with three biological replicates per group. g, Representative results from two out of the six animals analyzed. h, Representative results from two out of the thirteen animals analyzed.

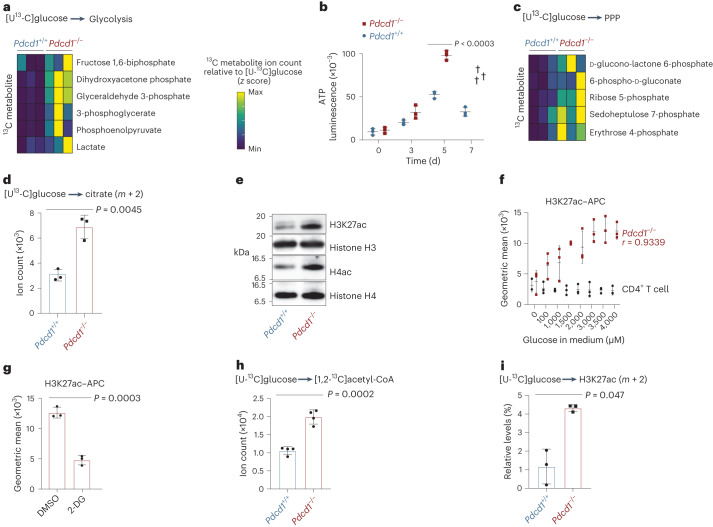

PD-1 limits oncogene-triggered energy metabolism

In general, cancer cells use the metabolism of glucose to generate ATP for energy supply, rapidly assimilate biomass and generate signaling molecules that can regulate gene expression18. To identify glycolysis-dependent lymphoma-enabling mechanisms in an unbiased manner, we incubated acute oncogene-expressing ITK–SYK+PD-1− T cells and their premalignant ITK–SYK+PD-1+ counterparts with uniformly labeled [U-13C]glucose ex vivo and performed LC–MS/MS analysis to trace [U-13C]glucose-derived metabolites24. The amount of 13C-labeled glycolysis intermediates, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate, dihydroxyacetone phosphate, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, 3-phosphoglycerate, phosphoenolpyruvate and lactate, was elevated in PD-1-deficient lymphoma cells (Fig. 3a), indicating enhanced glucose usage within the canonical upper glycolytic pathway. This pathway is particularly important for energy production25. Indeed, inactivation of PD-1 signaling boosts ATP levels (Fig. 3b; P < 0.0003), indicating that loss of PD-1 function can overcome the energy deficit in premalignant T cells that is required to fuel overt malignancy.

Fig. 3. PD-1 facilitates glycolysis-dependent histone acetylation.

a, Intracellular 13C abundance within the glycolysis pathways detected by targeted LC–MS/MS relative to intracellular [U-13C]glucose in ITK–SYK+ T cells with or without PD-1, cultured with uniformly labeled [U-13C]glucose for 3 h in vitro. Data are normalized to viable cell number and z scores per metabolite. Min, minimum. b, Time-dependent ATP measurement in ITK–SYK+ T cells with or without PD-1. P, two-sided Student’s t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. and individual data points for each animal. The cross indicates death of the animal. c, Ion count for intracellular 13C-labeled metabolites in the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP). d, Ion count for intracellular 13C-citrate (m + 2) isotopomers. P, two-sided Student’s t-test. Shown are the mean ± s.d. and individual data points. e, Western blot analysis of acetylated histones in ITK–SYK+ T cells with or without PD-1. H4ac, H4 acetylation. f, Flow cytometry for H3K27ac in wild-type CD4+ or ITK–SYK+ T cells after a 4-h in vitro incubation with different glucose concentrations. r, Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. and individual data points. g, Flow cytometry for H3K27ac in ITK–SYK+PD-1− cells after a 4-h in vitro culture with 2-DG (1 mM) or DMSO. P, paired two-sided Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. h, Levels of [U-13C]glucose-derived intracellular [1,2-13C]acetyl-CoA determined by targeted LC–MS/MS in ITK–SYK+ T cells with or without PD-1 cultured with uniformly labeled [U-13C]glucose (11 mM) for 4 h in vitro (n = 4 mice per genotype). Data were normalized as in a. P, two-sided Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. i, Levels of [U-13C]glucose-derived 13C-H3K27ac (m + 2) determined by orbitrap LC–MS/MS. Experiment as in h (with n = 3 mice per genotype). Data were normalized as in a. P, two-sided Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. a–d, Representative data from two independent experiments with n = 3 biological replicates per group. e, Representative data from two independent experiments with two biological replicates per group. f, Representative data from two independent experiments. g, Representative data from two independent experiments with three biological replicates per group. h, Representative data from one experiment with four biological replicates per group. i, Representative data from one experiment with three biological replicates per group.

In addition, we detected increased glucose utilization in the pentose phosphate pathway in ITK–SYK+PD-1− lymphoma cells, with augmented generation of [U-13C]glucose-derived glucono-lactone 6-phosphate, 6-phospho-d-gluconate, ribose 5-phosphate, sedoheptulose 7-phosphate and erythrose 4-phosphate (Fig. 3c). The overall abundance of [U-13C]glucose-derived tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) metabolites only slightly differed between transformed ITK–SYK+PD-1− T cells and their premalignant ITK–SYK+PD-1+ counterparts, although the specific levels of citrate (m + 2) showed a more than twofold increase in the absence of PD-1 (Fig. 3d; P = 0.0045).

PD-1 facilitates glycolysis-dependent histone acetylation

There is increasing evidence that metabolite abundance is also highly relevant for regulation of the tumor epigenome26,27. In particular, histone acetylation is extremely sensitive to the availability of extramitochondrial acetyl-CoA28. In this context, glucose-derived citrate, after export from the mitochondrion, is converted by ACLY to oxalacetate and cytosolic acetyl-CoA, which is subsequently used by acetyltransferases to mediate the acetylation of target proteins. After entering the nucleus, this pool of acetyl-CoA is critical for histone acetyltransferases to mediate histone acetylation for chromatin opening29,30. Because these pathways can link glucose metabolism to epigenetic regulation, which is frequently altered in T cell malignancy1, we next studied the effects of PD-1 inactivation on histone acetylation in ITK–SYK oncogene-expressing primary CD4+ T cells. Intriguingly, upon oncogenic T cell signaling, both the genetic deletion of Pdcd1 and acute pharmacological blockade of PD-1 triggered a significant increase in histone H4 and H3 lysine 27 (H3K27) acetylation (H3K27ac; Fig. 3e and Extended Data Fig. 4a). Ex vivo incubation of ITK–SYK+PD-1− lymphoma cells with glucose at increasing concentrations demonstrated that the level of H3K27ac depends directly on glucose availability (Fig. 3f; r = 0.9339)31. Conversely, inhibition of glycolysis with 2-DG resulted in a reduction in H3K27ac in PD-1-deficient lymphoma cells (Fig. 3g; P = 0.0003)32, demonstrating a link between PD-1 inactivation and glucose-dependent histone acetylation in oncogene-expressing T cells.

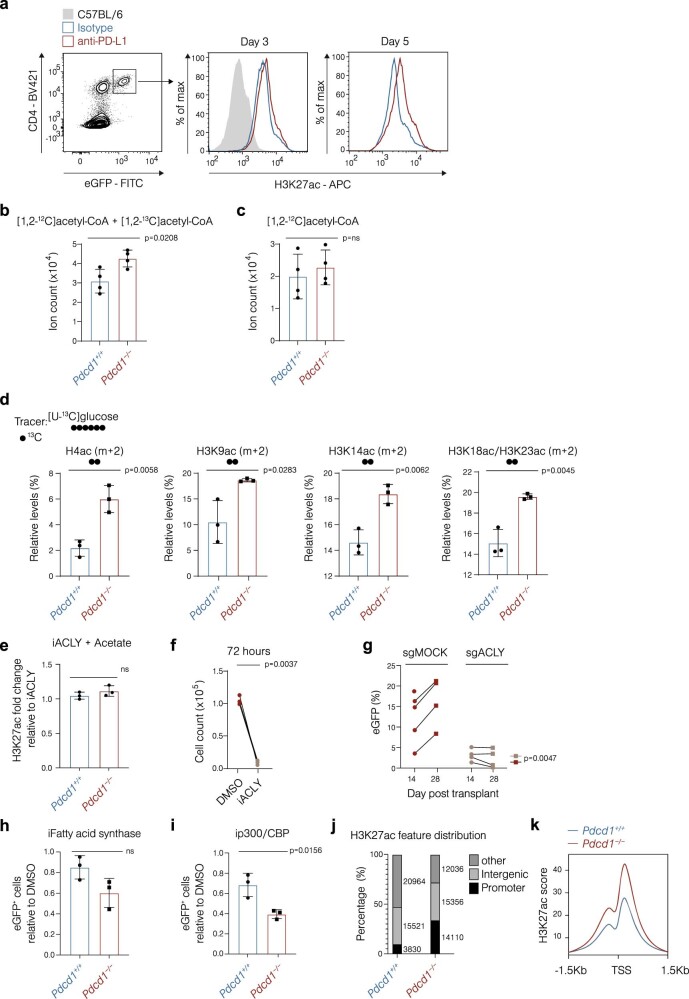

Extended Data Fig. 4. PD-1 controls ACLY-dependent epigenetic reprogramming.

a, H3K27ac in CD4 + GFP + T cells of ITK-SYKCD4-creERT2 or C57BL/6 mice on d5 after TAM +/− anti-PD-L1 antibody treatment. b, c, Non-labeled (b) and labeled (c) acetyl-CoA determined by targeted LC-MS/MS in ITK-SYK+ T cells +/− PD-1 cultured with uniformly labeled [U-13C]glucose (11 mM) for 4 h in vitro (n = 4 mice genotype). Normalization to viable cell numbers. P=two-sided Student’s t-test; mean ± SEM. d, [U-13C]glucose-derived 13C-acetyl groups on histones determined by orbitrap LC-MS/MS in ITK-SYK+ T cells +/− PD-1 cultured with uniformly labeled [U-13C]glucose (11 mM) for 4 h in vitro (n = 3 mice genotype). Normalization as in (b, c). P=two-sided Student’s t-test; mean ± SD. e, H3K27ac in ITK-SYK+ T cells +/− PD-1 after 3 h in vitro incubation with BMS-303141 (‘iACLY’, 15 μM) +/− acetate (100 μM; n = 3 biological replicates). P=paired two-sided Student’s t-test; mean ± SD. f, Viable ITK-SYK+PD-1- cells after 72 h in vitro culture with BMS-303141 (‘iACLY,’ 5 μM) or DMSO (n = 3 biological replicates). P=paired two-sided Student’s t-test. g, Viable ITK-SYK+ cells in the blood of sgACLY or sgMOCK-injected mice (n = 4 per group). P=two-sided Student’s t-test. h, Viable ITK-SYK+ cells +/− PD-1 after 3-day in vitro incubation with FT113 (1 μM) or DMSO (n = 3 biological replicates). P=two-sided Student’s t-test; mean ± SD. i, Viable ITK-SYK+ cells in presence of NEO2734 (50 nM). Experiment as in (e). P=two-sided Student’s t-test; mean ± SD. j, Percentage of H3K27ac ChIP-seq peak distribution over different genomic features as determined from the experiment in (d). k, Genome-wide average H3K27ac scores in a 3 Kb window around the TSS. ChIP-seq was performed as indicated in Fig. 4h. ChIP-seq, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing; TSS, transcription start site. a, Representative data from two independent experiments with n = 3 biological replicates per genotype. b, c, one experiment, n = 4 biological replicates. d, Data from one experiment. e, Representative data from one experiment with n = 3 biological replicates per genotype. f, Representative data from two independent experiments. g, Data from a single experiment. h,i, Representative data from three independent experiments with n = 3 biological replicates per genotype. j,k, Data from one experiment.

To explore whether this link involves glycolysis-dependent de novo generation of acetyl-CoA, we directly incubated ITK–SYK-expressing T cells from tamoxifen-injected ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice ex vivo with [U-13C]glucose and studied acetyl-CoA production by targeted LC–MS/MS analysis. Indeed, in the transformed ITK–SYK+PD-1− T cells, there was a significant increase in [1,2-13C]acetyl-CoA and total acetyl-CoA ([1,2-12C]acetyl-CoA + [1,2-13C]acetyl-CoA) generation (Fig. 3h and Extended Data Fig. 4c; P = 0.0002 and P = 0.0206), whereas the levels of [1,2-12C]acetyl-CoA did not differ (Extended Data Fig. 4b; P, NS). Next, we isolated histones from these oncogene-expressing primary T cells incubated with [U-13C]glucose for high-resolution LC–MS/MS analysis. We observed higher de novo acetylation of histones H3 and H4 with [U-13C]glucose-derived [13C]acetyl marks at H3K27, H3 lysine 9 (H3K9), H3 lysine 14 (H3K14), H3 lysine 18 (H3K18) and H3 lysine 23 (H3K23) in transformed ITK–SYK+PD-1− T cells than in PD-1-proficient ITK–SYK+PD-1+ cells (Fig. 3i and Extended Data Fig. 4d; P = 0.047)33. These data indicate that histone acetylation requires glycolysis-dependent acetyl-CoA synthesis after PD-1 inactivation in T cells with oncogenic T cell signaling.

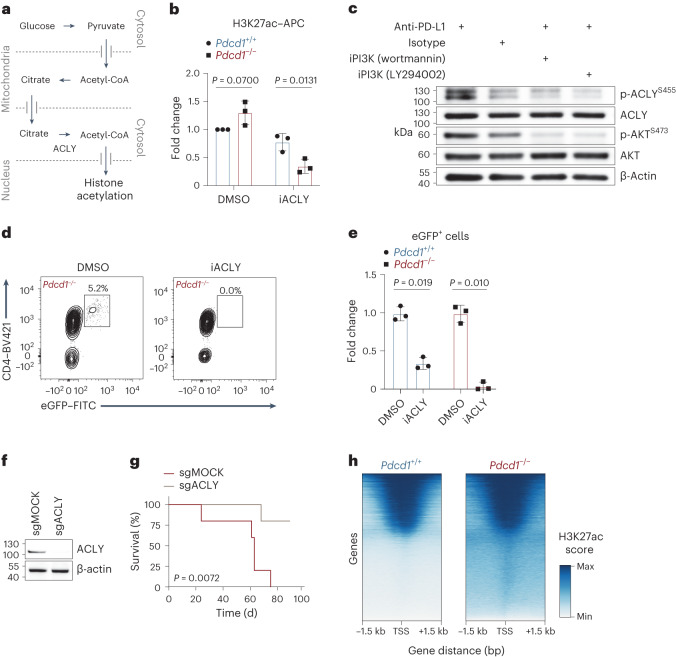

ACLY is a critical effector molecule downstream of PD-1

As indicated above, ACLY is the key enzyme that mediates the generation of glucose-derived extramitochondrial acetyl-CoA (Fig. 4a)34. To explore the function of ACLY in PD-1-regulated histone acetylation, we treated tamoxifen-injected ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 mice with anti-PD-L1 or isotype control antibodies and isolated oncogene-expressing CD4+ T cells. Next, we incubated these cells in vitro with the small-molecule ACLY inhibitor BMS-303141 for 3 h32. This treatment reduced histone acetylation in ITK–SYK+ cells in comparison to the dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) vehicle control (Fig. 4b). Notably, the dependence of H3K27ac on ACLY function was significantly higher in ITK–SYK-expressing cells with pharmacologically inactivated PD-1 pathway (Fig. 4b; P = 0.0131). Consistent with published results, exogenous supplementation of acetate at physiological levels (100 µM) could not restore decreased H3K27ac signals in ACLY inhibitor-treated lymphoma cells (Extended Data Fig. 4e).

Fig. 4. ACLY is a critical effector molecule downstream of PD-1.

a, Schematic of glucose flux to histone acetyl groups. b, Flow cytometry for H3K27ac in ITK–SYK+ cells after 4 h of in vitro culture with the ACLY inhibitor BMS-303141 (‘iACLY’, 15 μM) or DMSO. ITK-SYK+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry from ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection and 12 h of anti-PD-L1 or isotype control antibody treatment (intraperitoneal, 200 μg). P, paired two-sided Student’s t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± s.d. c, Western blot analysis in lysates from ITK–SYK+PD-1+ cells. Spleen-derived single-cell suspensions were sorted by flow cytometry from ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection and cultured in vitro overnight with anti-PD-L1 or isotype control antibodies and the PI3K inhibitors (‘iPI3K’) wortmannin (20 nM), LY294002 (20 μM) or DMSO. d, Flow cytometry for CD4 and eGFP in viable lymphocytes derived from spleens of acutely induced ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice after 3 d of in vitro culture with BMS-303141 (5 μM) or DMSO. e, Fold change in viable ITK–SYK-expressing eGFP+ cells in medium supplemented with BMS-303141 (5 μM) or DMSO. Spleen-derived lymphocytes, sorted by flow cytometry from ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection, were incubated for 3 d in vitro. P, two-sided Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. f, Western blot for ACLY in ITK–SYK+PD-1− cells electroporated with Acly-targeting (sgACLY) or non-targeting control (sgMOCK)RNP complexes. Protein lysates were generated after 48 h of in vitro culture. g, Survival of recipient mice transplanted with Acly (‘sgACLY’) or mock-edited (‘sgMOCK’) ITK–SYK+PD-1− cells. P, two-sided log-rank test. h, Gene-wise global H3K27ac scores from anti-H3K27ac ChIP–seq in a 1.5-kb window around the TSS. ITK–SYK+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry from ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection, fixed and processed for anti-H3K27ac ChIP–seq analysis. b, Representative data from three independent experiments with three biological replicates per group. c, Representative data from two independent experiments with two biological replicates. d,e, Representative data from three independent experiments. f,g, Data from one experiment with n = 5 mice per group. h, Data from a single experiment with two biological replicates per group.

The activity of ACLY itself can in principle be regulated by AKT, which can phosphorylate ACLY at serine 455, a key point of control for this enzyme35–39. As PD-1 inactivation results in (PI3K)–AKT signaling in oncogene-expressing T cells (Fig. 2e), we hypothesized that these events could additionally trigger ACLY activation39. To test this hypothesis, we induced ITK–SYK expression in CD4+ cells by injecting tamoxifen into ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 mice and acutely blocked PD-1 function with anti-PD-L1 treatment. Inactivation of PD-1 signaling resulted in direct activation of ACLY, as measured by phosphospecific phosphorylated (p)-ACLYS455 antibodies (Fig. 4c), and this phosphorylation could be reversed by PI3K inhibition with wortmannin or LY294002 (Fig. 4c)40.

To determine whether ACLY activity is required for PD-1-deficient lymphoma cell survival, we next incubated transformed ITK–SYK+PD-1− T cells from tamoxifen-injected ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice with an ACLY inhibitor. This treatment killed ITK–SYK+PD-1− lymphoma cells (Extended Data Fig. 4f; P = 0.0037). Importantly, co-cultures with splenocytes demonstrated that ITK–SYK+PD-1− T cells were highly sensitive to ACLY inhibition, whereas ITK–SYK+PD-1+ T cells and normal T cells were less affected (Fig. 4e,f; P = 0.019 and P = 0.010).

To genetically define whether ACLY is necessary for PD-1-deficient lymphoma growth in vivo, we disrupted Acly in transformed ITK–SYK+PD-1− T cells using CRISPR–Cas9-mediated gene editing and transplanted these cells into syngeneic wild-type hosts (Fig. 4f). While the control-edited ITK–SYK+PD-1− cells proliferated rapidly in vivo, as measured by eGFP monitoring, and killed all recipient animals as expected in less than 80 d, ACLY-deficient ITK–SYK+PD-1− T cells were unable to expand (Extended Data Fig. 4g and Fig. 4i; P = 0.0072). The acetyl-CoA pool can be used for both histone acetylation and other acetyl-CoA dependent pathways such as fatty acid synthesis. To distinguish the importance of these pathways, we used pharmacological inhibitors. Our experiments demonstrated that ITK–SYK+PD-1− cells were more sensitive to direct inhibition of histone acetylation with inhibitors of histone acetyltransferases p300 and CBP than their PD-1-competent counterparts. By contrast, inhibition of fatty acid synthase did not reveal a significant difference (Extended Data Fig. 4h,i; P = 0.0156).

Together, these functional and genetic data demonstrate that loss of PD-1 tumor-suppressor function results in enhanced ACLY activity via enforced (PI3K)–AKT signaling and that this mechanism is critical for both glucose-dependent histone acetylation and the malignant expansion of PD-1-deficient lymphomatous T cells.

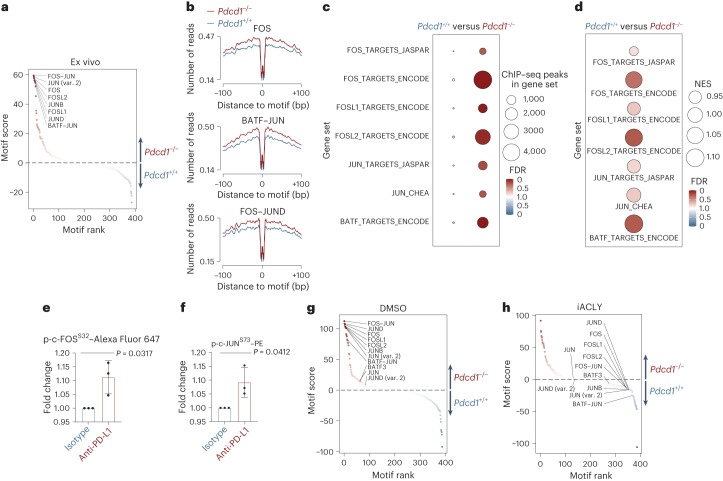

PD-1 controls epigenetic reprogramming and AP-1 activity

After establishing enhanced histone acetylation as a consequence of Pdcd1 inactivation in oncogene-expressing T cells, we next tested the epigenetic effects of this mechanism on genome regulation using genome-wide assays. Because H3K27 showed the greatest dependence on glucose-dependent de novo acetylation, we immunoprecipitated H3K27-acetylated histones from ITK–SYK-expressing T cells with or without PD-1 activity and performed high-throughput chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP–seq41). Overall, deletion of Pdcd1 increased H3K27ac in oncogene-expressing T cells, particularly within promoter regions and around gene transcription start sites (TSS), indicating direct effects on transcriptional regulation (Fig. 4h and Extended Data Fig. 4j,k)42,43. To assess how these events would affect chromatin accessibility for transcription factor occupancy, we conducted a genome-wide assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (ATAC-seq44) and performed transcription factor footprint analysis45–47. Intriguingly, in PD-1-deficient ITK–SYK-expressing T cells, we observed increased activity scores for the AP-1 family transcription factors c-FOS, FOSL1, FOSL2, c-JUN, JUNB and BATF (Fig. 5a,b). Next, we tested whether the histones at the AP-1 family target gene sequences are hyperacetylated in PD-1-deficient ITK–SYK-expressing T cells by performing GSEA using the H3K27ac ChIP–seq dataset (Fig. 4h; ChIP-Enrich analysis48) and the transcription factor target gene sets from the ENCODE, JASPAR and ChEA databases46,49–51. We detected a significant enrichment of c-FOS, FOSL1, FOSL2, c-JUN, and BATF target genes in H3K27ac ChIP–seq peaks upregulated in ITK–SYK+PD-1− lymphoma cells compared to their premalignant ITK–SYK+PD-1+ counterparts (Fig. 5c). Furthermore, global expression of AP-1 target mRNA species also increased with positive enrichment of the c-FOS, FOSL1, FOSL2, c-JUN and BATF gene sets in transformed ITK–SYK+PD-1− cells (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5. PD-1 controls AP-1 activity in an acetyl-CoA-dependent manner.

a, Differential transcription factor footprint analysis of ATAC-seq data. ITK–SYK+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry from ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection and immediately processed for ATAC-seq. JASPAR database motif names for the selected AP-1 family transcription factors are indicated. Enrichment of a transcription factor motif is indicated by motif score, motif rank and color. b, Binding profiles of selected transcription factors for the indicated genotypes from the experiment shown in a. c, ChIP-Enrich analysis of ChIP–seq data shown in Fig. 4h for the indicated gene sets. FDR, color intensity of the circles; ChIP–seq peaks in gene set, circle diameter. Blue and red indicate the genotype in which a signature was positively enriched. d, GSEA for the indicated gene sets. FDR, color intensity of circles; NES, circle diameter. Blue and red indicate the group in which a signature was positively enriched. e, Phosflow analysis of p-c-FOSS32 in ITK–SYK+ cells. Single-cell suspensions were generated from lymph nodes of ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection and 12 h of anti-PD-L1 or isotype control antibody treatment (intraperitoneal, 200 μg). P, paired two-sided Student’s t-test. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. f, Phosflow analysis of p-c-JUNS73. Same experiment as in e. g,h, Differential transcription factor footprint analysis of ATAC-seq data from ITK–SYK+PD-1+ and ITK–SYK+PD-1- cells after 3 h of in vitro incubation with BMS-303141 (5 μM, h) or DMSO (g). Spleen-derived eGFP+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry from ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice on day 5 after tamoxifen injection, incubated in iACLY- or DMSO-containing medium and processed for ATAC-seq. Legend as in a. a,b, Data from a single experiment with three biological replicates per genotype. c, Data from one experiment with two biological replicates per group. d, Data from a single experiment with four biological replicates per genotype. e,f, Representative data from two independent experiments with three biological replicates per group. g,h, Data from one experiment with three biological replicates per genotype. var., variant.

To investigate the underlying mechanism for AP-1 hyperactivation, we focused on the top-ranking motif in PD-1-deficient lymphoma cells, which was the c-FOS–c-JUN heterodimer (Fig. 5a). We performed additional ex vivo experiments to determine the PD-1-dependent phosphorylation status of c-FOS at serine 32 and of c-JUN at serine 73, respectively. These post-translational modifications are known to increase protein stability, nuclear localization and transcriptional activity52,53. To capture immediate changes upon PD-1 pathway inactivation, we used pharmacological blockade of PD-1 as introduced above (Fig. 2e). Our Phosflow data revealed a significant increase in p-c-FOSS32 and p-c-JUNS73 signals in ITK–SYK-expressing cells isolated from animals that had been treated with anti-PD-L1 checkpoint inhibition, suggesting that PD-1 indeed controls the transduction of oncogenic signals to AP-1 family members (Fig. 5e,f; P = 0.0317 and P = 0.0412).

We asked whether AP-1 hyperactivity in ITK–SYK+PD-1− lymphoma cells is induced by ACLY activity and subsequently inflated acetyl-CoA pools. To address this question, we again isolated ITK–SYK+PD-1+ and ITK–SYK+PD-1− cells from tamoxifen-treated ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− animals. This time, we incubated the cells in vitro in the presence of the ACLY inhibitor BMS-303141 or DMSO for 3 h. Next, we sorted eGFP+ cells by flow cytometry and performed ATAC-seq and transcription factor footprint analysis. In agreement with the ex vivo results (Fig. 5a), we detected AP-1 family members as top motifs enriched in PD-1-deficient cells (Fig. 5g). Strikingly, upon pharmacological inhibition of ACLY, AP-1 footprints were de-enriched in Pdcd1-deleted cells in comparison to their counterparts with intact PD-1 pathway (Fig. 5h).

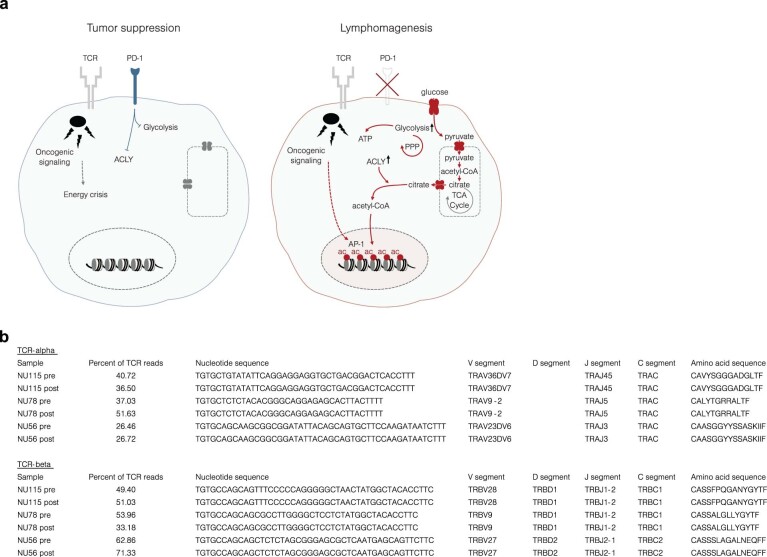

Altogether, these results from our genetically defined mouse models demonstrate that the loss of PD-1 signaling unleashes ACLY activity and thereby triggers glucose-dependent production of extramitochondrial acetyl-CoA to mediate de novo acetylation of histones to open chromatin and enable the enhanced activity of oncogenic AP-1 family transcription factors. Importantly, AP-1 hyperactivation in Pdcd1-deleted lymphoma cells was critically dependent on ACLY activity. Thus, our results indicate a link between glucose-derived acetyl-CoA availability and selective opening of compact chromatin at AP-1-binding sites, which is mediated by the PD-1 pathway (for a schematic model, see Extended Data Fig. 5a).

Extended Data Fig. 5. PD-1 tumor suppressor function.

a, Schematic model: Loss of PD-1 tumor suppressor function enables enhanced glucose uptake and glycolytic remodeling upon oncogenic T cell signaling. These events are critical for energy production in pre-malignant cells, for providing building blocks for rapid proliferation and preserving redox balance during T cell transformation and lymphoma progression. In addition, loss of PD-1 signaling unleashes ACLY activity and thereby triggers glucose-dependent production of extramitochondrial acetyl-CoA to mediate the de novo acetylation of histones to open chromatin and enhance the activity of oncogenic AP-1 family transcription factors. b, T-cell receptor sequence analysis of three CTCL patients with hyperprogressive disease. The nucleotide sequence, V-D-J-C segments, amino acid sequence, and percentage of T-cell receptor reads are shown for each sample before (‘pre’) and after (‘post’) hyperprogression. b, Data from one experiment.

Glycolysis and AP-1 activation in human PDCD1-mutated T-NHL

To elucidate whether these PD-1-dependent metabolic and epigenetic changes are also present in human T cell lymphoma, we analyzed leukemic stage primary patient samples from cohorts of clinically annotated T-NHLs of cutaneous origin by isolating malignant lymphoma cells by flow cytometry. We first examined a cohort of patients who experienced rapid disease progression, where the blood tumor burden increased by >400% in less than a 1-month period, which we termed ‘hyperprogression’ (Fig. 6a). TCR clonotyping confirmed that post-hyperprogression samples originated from identical T cell clones as the pre-hyperprogression samples (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Intriguingly, in all three instances, hyperprogressive disease was associated with profound downregulation of PDCD1 transcripts (Fig. 6b,c; P = 4.6 × 10−4, log2 (fold change) = −3.3). Notably, one of these cancers acquired a genetic deletion of PDCD1 upon disease progression (Fig. 6d), whereas the others lost PDCD1 expression by still uncharacterized mechanisms. These pre- and post-hyperprogression lymphomas were used for comparative RNA-seq and GSEA analysis. Consistent with our mouse model, we detected a significant enrichment of all signatures that represent enhanced activity of the (PI3K)–AKT–mTOR pathway, enforced HIF1α activity and increased glucose metabolism in post-hyperprogression samples with impaired PDCD1 expression compared to pre-hyperprogression samples (Fig. 6e).

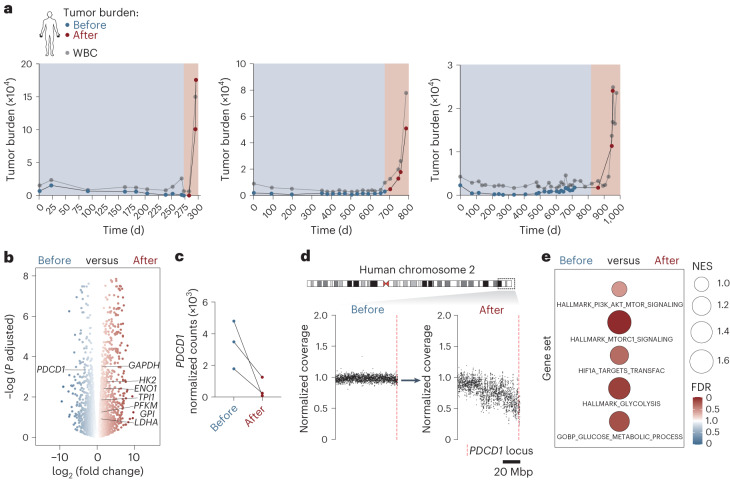

Fig. 6. PD-1 inactivation and glycolytic switch in hyperprogressive T-NHLs.

a, Serial longitudinal analysis of the tumor burden index and white blood cell (WBC) count for three individual patients with CTCL and hyperprogressive disease. Hyperprogression, rapid increase in tumor burden index (‘after’, shaded in red) after an extended period of stable disease course (‘before’, shaded in blue). b, Differential gene expression analysis of RNA-seq data derived from the three patients with CTCL in a before and after hyperprogression. Data points for selected glycolysis-related genes and PDCD1 are indicated. P, two-sided Wald test. c, RNA-seq read count of PDCD1 transcripts before and after hyperprogression shown for each patient individually. d, Whole-genome sequencing-based copy number aberration analysis of PDCD1-containing chromosomal region 2q36.3–2q37.3. The time point of genomic DNA isolation relative to hyperprogression is indicated (‘before’ versus ‘after’). The patient shown corresponds to the first patient in a. Top: the dashed box indicates the genomic region on human chromosome 2 that is shown in detail at the bottom. Bottom: copy number aberration analysis. The location of the PDCD1 locus is shown. e, GSEA for the indicated gene sets based on RNA-seq data derived from three patients with hyperprogression (a). The time point of RNA extraction relative to hyperprogression is indicated (‘before’ versus ‘after’). FDR, color intensity of circles; NES, circle diameter. Blue and red indicate the group in which a signature was positively enriched. a, Longitudinally collected data from three individual patients. b–e, Data from a single experiment with three patients.

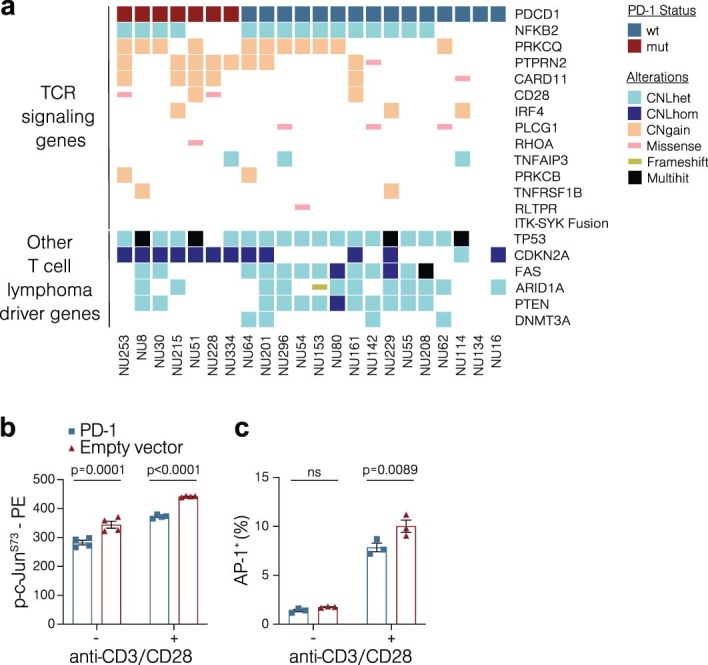

In addition, we studied a second cohort of patients with cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) that were either PDCD1 wild type or PDCD1 mutant at initial diagnosis. In line with previously reported frequencies2,12, we detected PDCD1 deletions in seven of the 21 specimens (Fig. 7a). RNA-seq and GSEA revealed a significant enrichment of the key gene sets for (PI3K)–AKT–mTOR signaling and HIF1α activation (Fig. 7b) in PDCD1-mutant patients. Again, we also observed enhanced activity of glycolysis gene sets in PDCD1-mutant lymphomas compared to PDCD1-wild-type lymphomas (Fig. 7b). None of the analyzed primary patient samples harbored the rare ITK–SYK fusion oncogene that we used in the mouse to model oncogenic TCR signaling. Instead, PDCD1-mutant human tumors harbored diverse and numerous oncogenic TCR signaling mutations including in CD28, PLCG1 and RHOA, suggesting that transcriptional effects are not tied to the identity of the oncogene (Extended Data Fig. 6a). Interestingly, multiple PDCD1-mutant lymphomas carried mutations in another tumor suppressor encoded by CDKN2A (Extended Data Fig. 6a).

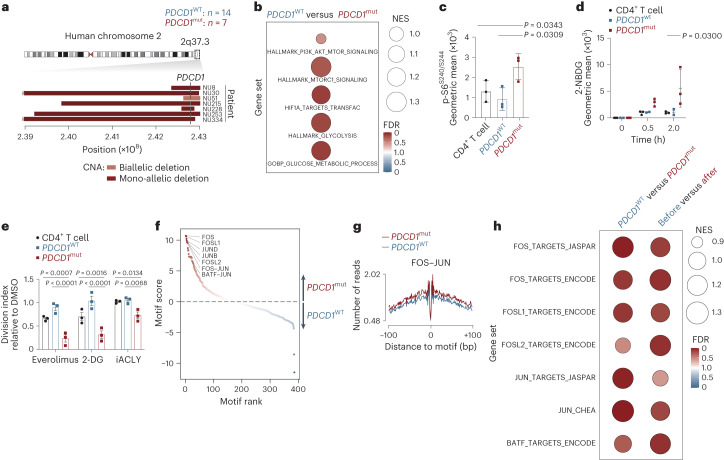

Fig. 7. ACLY dependence and AP-1 activation in human PD-1-defective T-NHL.

a, Genomic region within q37.3 on chromosome 2 in 21 patients with CTCL. CNA, copy number aberrations. PDCD1mut, PDCD1 mutant; PDCD1WT, PDCD1 wild type. b, GSEA for the indicated gene sets based on RNA-seq data from the 21 patients with CTCL shown in a. c, Phosflow analysis of serine 240 and 244 of S6 ribosomal protein in PDCD1-mutant (n = 3) and PDCD1-wild-type (n = 3) primary CTCL cells and in CD4+ T cells from healthy donors (n = 3). P, one-way ANOVA and two-sided Student’s t-test. Shown are the mean ± s.d. and individual data points. d, Uptake of the glucose analog 2-NBDG in PDCD1-mutant (n = 3) and PDCD1-wild-type (n = 3) primary CTCL cells and in CD4+ T cells from healthy donors (n = 3). Malignant cells sorted by flow cytometry were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 beads, and 2-NBDG uptake was determined at the indicated time points. P, two-sided Student’s t-test. Shown are the mean ± s.e.m. and individual data points. e, Relative division index of malignant T cells from three patients with mutated PDCD1 or reduced PD-1 expression after hyperprogression compared to three PDCD1-wild-type samples and healthy CD4+ T cells (n = 3) in the presence of 2-DG (1 mM), everolimus (0.1 μM) or BMS-303141 (iACLY, 10 μM). P, two-sided Student’s t-test. Data are presented as the mean ± s.e.m. and individual data points. f, Differential transcription factor footprint analysis of ATAC-seq data from three patients with CTCL with (‘PDCD1mut’) and three patients without (‘PDCD1WT’) mutated PDCD1. Legend as in Fig. 5a. g, Binding profile for the JASPAR FOS–JUN heterodimer motif for the indicated genotypes from the experiment shown in f. h, GSEA for the indicated gene sets with RNA-seq data from 21 patients with CTCL who were PDCD1 mutant or PDCD1 wild type and three patients with hyperprogression. a,b, Data from a single experiment with 21 patients. c,d, Data from one experiment with three patients per group and three healthy donors. e, Data from one experiment with three patients and three healthy donors. f,g, Data from one experiment with three patients per group. h, Data from a single experiment.

Extended Data Fig. 6. PD-1 controls post-translational AP-1 activation and transcriptional activity.

a, Oncoplot depicting mutation in T cell receptor (TCR) signaling pathway or other pathways detected in CTCL. Samples are grouped by PD-1 status, either wild-type (‘wt’) or mutant (‘mut’). b,c, MFI of p-c-JunS73 (b, n = 4) and percentage of cells positive for AP-1 reporter (c, n = 3) in Jurkat cells co-cultured with PD-L1 overexpressing Raji cells, with or without anti-CD3/CD28 beads. Jurkat cells were transduced with a lentivirus encoding either PD-1 or an empty vector control. In b, cells were co-cultured for 1 hour prior to analysis. In c, cells were co-cultured for 24 hours prior to analysis. P = 2-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparison test. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity. The data are presented as the mean ± SEM and individual data points are shown. a, Data from one experiment. b,c, Representative data from 2 independent experiments.

Next, we used viable primary patient samples from these two cohorts to functionally assess our findings on the (PI3K)–AKT–mTOR axis, which is under PD-1 control in normal and malignant T cells, and our discovery of ACLY as a PD-1 target molecule in T-NHL. First, we probed the impact of PDCD1 deletions on (PI3K)–AKT–mTOR signaling and glucose uptake based on six individual patients, three with mutant PDCD1 and three with wild-type PDCD1. In line with our findings in the murine model, PDCD1-mutant lymphoma cells exhibited a significant increase in S6 ribosomal protein phosphorylation, demonstrating enhanced mTOR activity compared to PDCD1-wild-type cells (Fig. 7c; P = 0.0309)54. Moreover, uptake of the fluorescent glucose analog 2-NBDG was also significantly increased in PDCD1-mutant lymphoma cells (Fig. 7d; P = 0.03)55. To perturb (PI3K)–AKT–mTOR signaling, glycolysis or ACLY activity in viable PDCD1-wild-type and PDCD1-mutant lymphoma cells, we incubated the six primary patient samples with respective small-molecule inhibitors of these pathways. Treatment with the mTORC1 inhibitor everolimus, which is currently in clinical trials for T-NHL therapy (NCT00918333 and NCT01075321), reduced viability and division of PDCD1-mutant cancer cells (Fig. 7e). Similarly, inhibition of glycolysis with 2-DG or ACLY blockage with BMS-303141 also significantly impaired cell proliferation in PD-1-deficient lymphomas (Fig. 7e). Importantly, stage-matched PD-1-wild-type tumors were resistant to everolimus, 2-DG and inhibition of ACLY. These data suggest that PD-1 loss confers therapeutic vulnerability to these inhibitors (Fig. 7e).

Finally, we assessed chromatin accessibility in primary cells from three PDCD1-wild-type and three PDCD1-mutant CTCLs by ATAC-seq and performed transcription factor footprint analysis (Fig. 7f,g). Similar to the murine model, the top transcription factor motifs most enriched in the PDCD1 mutant compared to the wild type were AP-1 family members, including c-FOS, FOSL1, FOSL2, c-JUN, JUNB and BATF, which we corroborated with functional in vitro assays (Fig. 7f,g and Extended Data Fig. 6b,c). Furthermore, at the global transcript level, both PDCD1-mutant and post-hyperprogression T-NHL samples showed a significant enrichment in c-FOS, FOSL1, FOSL2, c-JUN and BATF target genes (Fig. 7h).

Discussion

Here, we identified the key components of the PD-1 tumor-suppressor program in T cell lymphoma. Using a combination of genetic mouse models and primary human T-NHL samples, our results highlight the role of PD-1 as a critical gatekeeper molecule curtailing the glycolytic switch during neoplastic transformation of a T cell. We provide evidence that metabolic reprogramming via the (PI3K)–AKT–mTOR–HIF1α axis leads to induction of rate-limiting factors for glucose uptake and metabolization to enforce tumor cell energy production. This tumor-suppressive activity of PD-1 specifically suppresses glycolytic reprogramming but not oxidative phosphorylation.

Interestingly, our data presented here and previous work2 indicate that PD-1-mutation status could serve as a potential biomarker for genotype-specific vulnerabilities in T cell lymphomas. For example, mTOR is currently being evaluated as a target in T-NHL with heterogeneous clinical results56. We provide evidence that molecular stratification based on genetic PDCD1 status could help to identify patients who will likely respond to mTOR pathway inhibition. Moreover, our data suggest enhanced ACLY activity as a selective vulnerability in PDCD1-mutant T-NHLs. Furthermore, we describe a previously unknown link between PD-1 signaling and metabolite-controlled epigenetic reprogramming. Upon PD-1 loss, increased pools of glycolysis-derived citrate permit enhanced acetyl-CoA production. This in turn enforces opening of compact chromatin at AP-1-binding sites and enhanced transcription of AP-1 target genes. Conversely, pharmacological inhibition of ACLY curtails AP-1 hyperactivation and is toxic to PDCD1-mutant lymphomas. Notably, antigenic stimulation of non-transformed T cells also induces AP-1 activity and enforces AP-1-directed chromatin remodeling57. However, in contrast to oncogenic AP-1 activation in T-NHL, this process strictly depends on external induction of co-stimulatory pathways such as CD28 (ref. 57) through still ill-defined mechanisms.

While our results identify PD-1 as a metabolic gatekeeper for T-NHL energy metabolism and induction of the epigenetic ACLY–AP-1 axis, several questions remain open. On the one hand, it is unclear whether unleashed ACLY activity in PDCD1-mutant lymphomas regulates acetyl-CoA-dependent metabolic pathways apart from histone acetylation, similar to de novo generation of lipids. On the other hand, it is undefined how PD-1 signaling regulates individual AP-1 family members. While our data show enhanced phosphorylation of key serine residues within the transactivation domains of c-JUN and c-FOS in the absence of PD-1 signaling, the precise mechanisms that underlie these effects remain to be uncovered. In this context, it will also be critical to elucidate how acetyl-CoA abundance can selectively enhance recruitment of AP-1 factors to AP-1–DNA binding sites and whether related pathways are also active in non-transformed T cells and during T cell exhaustion, which is frequently associated with chronic PD-1 signaling and dysregulated AP-1 activity58.

In sum, our findings establish PD-1 as a central regulator for tumor cell energy metabolism and AP-1 activity in T-NHL. We demonstrate that PD-1 restricts glycolysis, glucose-derived acetyl-CoA production and chromatin remodeling. PD-1-deficient T-NHLs acquire epigenetic changes that increase access for AP-1 factors in otherwise compact DNA. This mechanism is highly conserved between human and murine lymphomas. Our results link PD-1 mutations with AP-1 hyperactivation, which has been demonstrated to be a hallmark of aggressive, drug-resistant T-NHLs59. Moreover, our data highlight the (PI3K)–AKT–mTOR–HIF1α–ACLY-axis as a genotype-specific therapeutic vulnerability in aggressive T cell lymphomas with defective PD-1 function, which should be tested in future clinical interventions.

Methods

We confirm that all experiments with mice and human patient-derived material were performed in accordance with local animal-protection guidelines (Regierung von Oberbayern, Munich, Germany) or after approval by the Northwestern University Institutional Review Board, respectively.

Mice

Mice of both sexes aged 6–12 weeks were used for all experiments. Littermate controls were used whenever possible. Randomization and blinding were not performed. ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− animals were described earlier and maintained on a C57BL/6 genetic background12. Pdcd1−/− (028276), B6J.129(Cg)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm1.1(CAG-cas9*,-EGFP)Fezh/J (Cas9, 026179) and NOD.CG-Prkdcscid IL2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NOD–SCID gamma (NSG), 005557) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with local guidelines (Regierung von Oberbayern, Munich, Germany). Mice were euthanized if they exhibited signs of lymphoma (lymph node enlargement, palpable tumor, labored breathing, ascites) or if they lost 20% or more of their body weight. None of the approved thresholds were exceeded at any time. Mice were kept in greenline cages (Tecniplast Typ I superlong) at temperatures between 20 and 24 °C and at 45–60% humidity, receiving pelleted food (1324SP, Altromin) and autoclaved water ad libitum. A light–dark rhythm changed every 12 h with included dimming phases. For peripheral T cell lymphomas, both sexes showed nearly identical trends in survival, although incidence rates were higher in males than in females (https://seer.cancer.gov). In accordance with this, we used both female and male mice. We indicate also that our mouse models did not reveal any differences in PD-1 expression and survival after PD-1 inactivation based upon sex. We used the same numbers of male and female mice in each experiment whenever possible.

Induction of spontaneous ITK–SYK expression in peripheral T cells

Tamoxifen (T5648, Sigma) was dissolved in pure ethanol (with heating) and subsequently diluted in migliol (3274, Caesar & Loretz) to a final concentration of 10 mg ml−1. To induce expression of ITK–SYK in peripheral CD4+ T cells, ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with tamoxifen at the indicated concentrations.

RNA-seq of mouse samples

ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 or ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice received a single dose of 2 mg tamoxifen. Five days later, spleens were collected, and 1,000 eGFP+ ITK–SYK-expressing CD4+ T cells from both genotypes were directly sorted (FACSAria Fusion, BD Biosciences) into a 96-well PCR plate prefilled with 10 µl of 1× TCL buffer (1070498, Qiagen) containing 1% (vol/vol) β-mercaptoethanol (M6250, Sigma). Library preparation for bulk 3′ sequencing of poly(A) RNA was performed as outlined earlier60. Briefly, for each sample, barcoded full-length complementary DNA (cDNA) was generated with Maxima RT polymerase (EP0742, Thermo) using oligonucleotide-dT primer-containing barcodes, unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) and an adaptor. The addition of a template switch oligonucleotide resulted in extension of the 5′ ends of the cDNA, and full-length cDNA was amplified with a primer binding to the template switch oligonucleotide site and the adaptor. cDNA was fragmented using the Nextera XT kit (FC-131-1096, Illumina), and only the 3′ end fragments were amplified using primers with Illumina P5 and P7 overhangs. Compared to ref. 60, the P5 and P7 sites were exchanged to allow sequencing of the cDNA in read 1 and barcodes and UMIs in read 2 to achieve better cluster recognition. The library was sequenced on the NextSeq 500 platform (Illumina) with 75 cycles for cDNA and 16 cycles for barcodes and UMIs. Raw sequencing data were processed with DropSeq-tools (version 1.12) using gene annotations from the Ensembl GRCm38.87 database to generate sample- and gene-wise UMI tables61. Downstream analysis was conducted using R version 3.4.452 and DESeq2 version 1.18.153 (ref. 62). Technical replicates with <100,000 total UMIs were excluded before differential expression analysis, and the remaining replicates were collapsed. Genes with <10 reads across all conditions were excluded. Prior differential expression analysis and dispersion of the data were estimated using a parametric fit. GSEA 4.1.0 was used to calculate enrichment for the indicated signatures. All signatures were derived from MSigDB and Harmonizome51,63–65.

Western blot analysis of cytosolic proteins and histones

ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2, ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− or C57BL/6 mice were intraperitoneally injected with a single dose of 2 mg tamoxifen and received 200 μg anti-PD-L1 antibody (BE0101, BioXcell) or isotype control antibody (BE0090, BioXcell), depending on the experimental condition. At the indicated time points, single-cell suspensions were generated, and eGFP+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry and lysed on ice in protein lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, pH 8, 1% NP-40) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (4906845001 and 539131, Sigma). The following antibodies were used at 1:1,000 or 1:10,000 (actin) dilutions for protein detection: anti-hexokinase 2 (ab209847, Abcam), anti-phosphofructokinase 1 (PFKM; MAB7687-SP, R&D Systems), anti-aldolase A (8060, CST), anti-enolase 1 (3810T, CST), anti-actin (3700, CST), anti-histone H3 (9715, CST), anti-acetyl-histone H3 Lys27 (8173, CST), anti-histone H4 (2935, CST), anti-acetyl-histone H4 (06-598, Millipore), anti-ACLY (4332, CST), anti-p-ACLY (4331, CST), anti-AKT (4691, CST) and anti-p-AKT (4060, CST).

Analysis of p-ACLYS455

For the analysis of PD-1-dependent ACLY phosphorylation at serine 455, single-cell suspensions from the spleens of acutely induced ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 mice were incubated overnight with anti-PD-L1 antibody (4 μg ml−1, BE0101, BioXcell), isotype control (4 μg ml−1, BE0090, BioXcell), DMSO, wortmannin (2 μM, 12-338, Sigma) or LY294002 (10 μM, S1105, SelleckChem). The next day, cells were sorted by flow cytometry for the eGFP+ phenotype and lysed as described above.

Analysis of histones

For western blotting of histones, single-cell suspensions were generated from the spleens of acutely induced ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice. Subsequently, eGFP+ cells sorted by flow cytometry were cultured for 4 h in vitro in glucose-free DMEM (11966025, Thermo) supplemented with 1% dialyzed fetal calf serum (FCS; A3382001, Thermo) and 1 mM glucose (G8270, Sigma). Next, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS, and acid-based histone extraction was performed according to published protocols66.

Glucose assay of cell culture supernatants

ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with a single dose of 2 mg tamoxifen. On day five, single-cell suspensions were generated, and eGFP+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry. Two hundred thousand T cells were cultured in vitro in glucose-free DMEM (11966025, Thermo) supplemented with 10% dialyzed FCS (A3382001, Thermo), 2 mM glutamine (25030149, Thermo) and 10 mM glucose for 3 h. The remaining glucose in the supernatants was measured using the Amplex Red Glucose/Glucose Oxidase Assay Kit (A22189, Thermo).

Seahorse assays

ECAR and OCR were measured using a Seahorse XFe96 Analyzer (Agilent) in XF medium (non-buffered RPMI 1640 medium containing 2 mM glutamine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (11360070, Thermo) and 25 mM glucose). Two hundred thousand eGFP+ ITK–SYK-expressing T cells per well were sorted by flow cytometry and centrifuged onto poly-d-lysine (P6403, Sigma)-coated 96-well plates (101085-004, Agilent) and pre-incubated at 37 °C for 45 min in the absence of CO2. Five days before the experiment, ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice received a single dose of 2 mg tamoxifen and, depending on the experiment, intraperitoneal injections of anti-PD-L1 antibody (200 μg, BE0101, BioXcell) or isotype control (200 μg, BE0090, BioXcell) as indicated in the figure legends.

In vivo metabolic imaging using PET–CT and hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance imaging

C57BL/6, ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 or ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice received a single dose of 2 mg tamoxifen. For PET–CT imaging, mice were injected with [18F]FDG (~12 MBq), and tracer uptake was measured after 90 min using a preclinical Siemens Inveon PET–CT system. Splenic standardized uptake values were calculated using Inveon Research Workplace software. Hyperpolarized 13C MRI of the animals was performed using a preclinical 7-T magnetic resonance scanner (Agilent–GE Discovery MR901 magnet and gradient system, Bruker AVANCE III HD electronics). The animals were injected with hyperpolarized [1-13C]pyruvate (250 µl, 80 mM, HyperSense DNP, Oxford Instruments), and both [1-13C]pyruvate and [1-13C]lactate were recorded in vivo using a static 2D FID–CSI (matrix size, 18 × 12; FOV, 30 mm × 20 mm; slice thickness, 3 mm; flip angle, 12°; number of points, 128; bandwidth, 2,000 Hz). T2-weighted images (1H-RARE; matrix size, 150 × 100; FOV, 30 mm × 20 mm; slice thickness, 1 mm) were recorded for co-registration and determination of spleen size. Peak heights for [1-13C]pyruvate versus [1-13C]lactate were determined and summed over the spleen region of interest using MATLAB code developed in house.

Intracellular flow cytometry and Phosflow of murine cells

Ex vivo

TK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 or ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with a single dose of 2 mg tamoxifen. At the indicated time points, cells were isolated and immediately fixed in 4% PFA (28906, Thermo), permeabilized using methanol, stained for CD4 (100437, BioLegend), p-AKTS473 (48-9715-42, Thermo), p-mTORS2448 (2971, CST), hexokinase 2 (ab209847, Abcam), GLUT1 (PA1-46152, Thermo), p-S6S240/S244 (5364S, CST), acetyl-histone H3 Lys27 (13027, CST), HIF1α (36169, CST), Alexa Fluor 647 p-c-FOSS63 (8677, CST) and PE p-c-JUNS73 (8752, CST) and assessed by flow cytometry. Surface and intracellular antibodies were used at dilutions of 1:300 and 1:100, respectively. The following antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:300 as secondary antibodies: PE donkey anti-rabbit IgG (406421, BioLegend) or PE goat anti-mouse IgG (405307, BioLegend). Data were acquired using a FACSCanto II or an LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences). FlowJo software was used for data analyses (FlowJo).

In vitro

eGFP+ T cells sorted by flow cytometry from tamoxifen-injected C57BL/6 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice were cultured in vitro in glucose-free DMEM (11966025, Thermo) supplemented with 1% dialyzed FCS (A3382001, Thermo). After 4 h, the cells were fixed in 4% PFA and processed as described above. An exemplified gating strategy is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Metabolomics

ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice were intraperitoneally injected with a single dose of 2 mg tamoxifen per mouse. Five days later, spleen- and lymph node-derived single-cell suspensions were sorted by flow cytometry for the eGFP+ phenotype. Subsequently, cells were incubated in glucose-free DMEM (11966025, Thermo) supplemented with 10% dialyzed FCS (A3382001, Thermo) and 11 mM uniformly labeled [U13C]glucose (CLM-1396, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). After 3 h of in vitro culture, cells were washed with ice-cold 0.9% NaCl and resuspended in 1 ml of ice-cold 80% methanol–water solution (vol/vol; 51140, Thermo; AE71.1, Carl Roth), including internal standards, followed by incubation for 8 h at −80 °C. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 13,000g and 4 °C for 10 min, and then the supernatants were dried in a SpeedVac concentrator (Savant, Thermo). Lyophilized samples were reconstituted in 40 μl of LC–MS-grade water, vortexed and centrifuged again for 10 min at 13,000g and 4 °C. Samples were analyzed using an Agilent 1200 series HPLC system interfaced with an AB Sciex 5500 hybrid triple quadrupole/linear ion trap mass spectrometer equipped with an electrospray ionization source operating in positive or negative mode. Q1 (precursor ion) and Q3 (fragment ion) transitions, the metabolite identifier, dwell times and collision energies for both positive and negative ion modes were used according to published methods with additional transitions for our internal standards24,67. Five microliters of sample was injected onto an XBridge Amide HPLC column (3.5 μm; 4.6 mm × 100 mm, 186004868, Waters). Mobile phases were run at 400 μl min–1 and consisted of HPLC buffer A (pH 9.0, 95% (vol/vol) water, 5% (vol/vol) acetonitrile (ACN), 20 mM ammonium hydroxide, 20 mM ammonium acetate) and HPLC buffer B (100% ACN). The HPLC settings were as follows: from 0 to 0.1 min, the mobile phase was maintained at 85% buffer B; from 0.1 to 3 min, the percentage of buffer B was decreased from 85% to 30%; from 3 to 12 min, the percentage of buffer B was decreased from 30% to 2% and was maintained at 2% for an additional 3 min. At 15 min, the percentage of buffer B was increased again to 85%, and the column was flushed for an additional 8 min with 85% buffer B. MultiQuant (version 2.1.1, AB Sciex) software was used for data analysis. Metabolite peaks were normalized by cell number and internal standards before statistical analyses.

The retention times for all metabolites were verified using individual purified standards from Sigma: Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis Metabolite Library (ML0013-1KT), Pentose Phosphate Metabolite Library (ML0012), TCA Cycle Metabolite Library (ML0010)), l-glutathione reduced (G4251), l-glutathione oxidized (G6654), l-serine (S4500) and α-d-glucose 1-phosphate (G6750) using the same chromatographic method. Metabolites were quantified by integrating the chromatographic peak area of the precursor ion.

For measurements without 13C labeling, eGFP+ cells sorted by flow cytometry from acutely induced ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice were incubated overnight in vitro in glucose- and glutamine-free DMEM (A1443001, Thermo) supplemented with 10% dialyzed FCS (A3382001, Thermo) and 11 mM glucose (G8270, Sigma), 11 mM galactose (G0750, Sigma) or 11 mM galactose combined with 2 mM N-acetylcysteine (A7250, Sigma). The next day, metabolites were isolated and quantified as described above.

For measurement of acetyl-1,2-[13C2]CoA, cells from the indicated genotypes were prepared as previously described. LC–MS/MS analysis was performed with the following modifications: 10 µl of sample was injected onto an XSelect HSS T3 XP Column (100 Å, 2.5 µm, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, 186006151, Waters). Mobile phases were run at 350 μl min–1 and consisted of HPLC buffer A (20 mM ammonium hydroxide, 20 mM ammonium acetate in water (pH 9)) and HPLC buffer B (20 mM ammonium acetate in methanol). The HPLC settings were as follows: from 0 to 1 min, the mobile phase was maintained at 2% buffer B; from 1 to 6 min, the percentage of buffer B was increased from 2% to 80%; from 6 to 9 min, the percentage of buffer B was increased from 80% to 100% and was maintained at 100% for an additional 4 min. At 13 min, the percentage of buffer B was decreased again to 2%, and the column was flushed for an additional 5 min with 2% buffer B. The transitions used are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

To establish the method, the following purified standards were purchased: acetyl-1,2-[13C2]CoA lithium salt (658650, Sigma), acetyl-CoA sodium salt (A2056, Sigma) and CoA hydrate (C4282, Sigma).

LC–MS/MS analysis of histone post-translational modifications

ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2 and ITK-SYKCD4-CreERT2;Pdcd1−/− mice received a single dose of 2 mg tamoxifen. Five days later, cells were isolated from the spleen, and eGFP+ cells were sorted by flow cytometry and cultured in glucose-free DMEM (Thermo, 11966025) supplemented with 10% dialyzed FCS (A3382001, Thermo) and 1 mM [U13C]glucose (CLM-1396, Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). After 4 h of in vitro culture, the cells were washed once with PBS and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. For histone post-translational modification analysis, approximately 1 million cells were extracted with acid. The pelleted cells were resuspended in 100 μl of 0.2 M H2SO4, and histones were extracted by rotating overnight at 4 °C. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,817g for 10 min at 4 °C. Histones were precipitated by adding trichloroacetic acid (85183, Thermo) to a final concentration of 26%. The tubes were mixed and incubated at 4 °C for 2 h and centrifuged at 20,817g for 15 min. Pellets were washed three times with ice-cold 100% acetone (AA22928-K2, VWR) (5 min of rotation at 4 °C, 15 min of centrifugation at 20,817g and 4 °C between washes), dried for 15 min at room temperature, resuspended in 20 μl of 1× Laemmli sample buffer per million cells and boiled at 95 °C for 5 min. Samples were stored at −20 °C until further use. Precast polyacrylamide (4–20%) gels (43277.01, Serva) were used to separate the histones corresponding to 0.5 × 106 cells. Gels were briefly stained with InstantBlue Coomassie Protein Stain (ab119211, Abcam). For targeted mass spectrometry analysis, histone bands were excised, washed once with LC–MS-grade water (1153331000, Sigma) and destained twice (or until transparent) by incubating for 30 min at 37 °C with 200 μl of 50% ACN (8825.2, Carl Roth) in 50 mM NH4HCO3 (T871.1, Carl Roth). Gel pieces were then washed twice with 200 μl LC–MS-grade water and twice with 200 μl of 100% ACN to dehydrate them. Histones were acylated in gel by adding 20 μl of propionic anhydride (175641, Sigma) and 40 μl of 100 mM NH4HCO3. After 5 min, 140 μl of 1 M NH4HCO3 was slowly added to the reaction. The pH was confirmed to be approximately 7 for each sample (when the reaction was acidic, a few microliters of 1 M NH4HCO3 was added). The samples were incubated at 37 °C for 45 min at 550 r.p.m. Afterward, samples were washed five times with 200 μl of 100 mM NH4HCO3, four times with 200 μl MS-grade water and four times with 200 μl of 100% ACN. They were centrifuged briefly, and all the remaining ACN was removed. Gel pieces were rehydrated in 50 μl trypsin solution (25 ng ml−1 trypsin in 100 mM NH4HCO3) (V5111, Promega) with 1-μl spike tides (SPT-ME-TQL, JPT Peptide Technologies) and incubated at 4 °C for 20 min. After the addition of 150 μl of 50 mM NH4HCO3, histones were digested in gel overnight at 37 °C and 550 r.p.m. Peptides were sequentially extracted by incubating for 10 min at room temperature with 150 μl of 50 mM NH4HCO3, twice with 150 μl of 50% ACN (in LC–MS-grade water), 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and twice with 100 μl of 100% ACN. During each of the washing steps, the samples were sonicated for 3 min in a water bath followed by brief centrifugation. The obtained peptides were dried using a centrifugal evaporator and stored at −20 °C until resuspension in 30 μl of 0.1% TFA. For desalting, peptides were loaded in a C18 StageTip (prewashed with 20 μl of methanol followed by 20 μl of 80% ACN and 0.1% TFA and equilibrated with 20 μl of 0.1% TFA), washed twice with 20 μl 0.1% TFA and eluted three times with 10 μl of 80% ACN and 0.25% TFA. The flowthrough obtained from loading peptides in C18 was further desalted with TopTip Carbon (TT1CAR.96, GlyGen) by loading the flowthrough three times (prewashed three times with 30 μl of 100% ACN followed by equilibration three times with 30 μl of 0.1% TFA), washed five times with 30 μl of 0.1% TFA and eluted three times with 15 μl of 70% ACN and 0.1% TFA. Eluted peptides from both desalting steps were combined and evaporated in a centrifugal evaporator, resuspended in 17 μl of 0.1% TFA and stored at −20 °C. The resuspended samples were injected into an UltiMate 3000 RSLCnano system (Thermo) and separated in a 25-cm Aurora column (IonOpticks) with a 50-min gradient from 6% to 43% of 80% ACN in 0.1% formic acid and a 50-min gradient from 5% to 60% ACN in 0.1% formic acid. The effluent from the HPLC was directly electrosprayed into a Q Exactive HF system (Thermo) operated in data-dependent mode to automatically switch between full-scan MS and MS/MS acquisition. Survey full-scan MS spectra (from m/z 250 to 1,600) were acquired with a resolution of R = 60,000 at an m/z of 400 (AGC target of 3 × 106). The ten most intense peptide ions with charge states between 2 and 5 were sequentially isolated to a target value of 1 × 105 and fragmented at 27% normalized collision energy. Typical mass spectrometric conditions were as follows: spray voltage, 1.5 kV; no sheath and auxiliary gas flow; heated capillary temperature, 250 °C; ion-selection threshold, 33.000 counts. Peak integration was performed using Skyline68. Quantified data were further analyzed in R using a previously published formula69.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing