Abstract

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is one of the non-communicable diseases which continues to rise in prevalence and mortality rate throughout the years. Drug-related problems (DRPs) are more prevalent among T2DM patients especially those with co-morbidities.

Objective

The objective of this study was to review and assess the prevalence and characteristics of DRPs among hospitalized type 2 diabetes mellitus patients.

Methods

The systematic review of the literature was carried out using five online databases: PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library from the inception of the database until June 2022. Studies included in the review were published in English or Malay language. The data were extracted and assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools.

Results

A total of 939 studies were identified with 20 studies that met inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review. The overall prevalence of DRPs in all 20 studies ranged from 7% to 94%. The most common DRPs included drug-drug interaction (DDI), adverse drug reaction (ADR), therapeutic effectiveness problems, and inappropriate medication use.

Conclusion

The most common drug classes involved were antidiabetics (metformin), antihypertensives, antiplatelets and antibiotics. The risk factors contributing to DRPs included the presence of comorbidities, the number of medications, and polypharmacy. To conclude, the rate of DRPs incidence in hospitalized T2DM patients was observed to be high. Further future studies with appropriate study designs and methods of detecting DRPs will be necessary to reduce and prevent DRPs occurrences.

Keywords: Patient safety, Drug safety, Diabetes, Health care quality, Health outcomes, Medical care, Pharmaceutical care, Adverse drug reaction

Introduction

The administration of medications is essential for the treatment and prevention of health issues. Throughout the years, the number of medications developed is increasing which has led to the discovery of more complex drug regimens to treat patients. Despite the remarkable advance in drug development to treat patients, Drug-Related Problems (DRPs) may arise which can cause undesirable treatment outcomes and potentially worsen patient conditions. According to the Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE), DRP is defined as “an event or circumstance involving drug therapy that actually or potentially interferes with desired health outcomes”.1 There are nine sub-categories identified causes of DRPs: 1. Improper drug selection 2. Improper dose selection 3. Inappropriate dose selection 4. Duration of treatment 5. Problem with prescribing and dispensing process 6. Issues with drug administration process 7. Patient-related including behavior 8. Patient transfer related, between primary, secondary, and tertiary care.1 The three main types of DRPs include Medication Error (ME) defined as “a failure in the treatment process that leads to, or has the potential to lead to, harm to the patient”.2,3 Adverse Drug Reactions (ADR) defined as “any response to a drug which is noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses normally used in humans for prophylaxis, diagnosis or therapy of disease, or for the modification of physiological function”,4 and Adverse Event defined as “an adverse outcome that can be attributed, with some degree of probability, to an action of a drug”.5

The prevalence of T2DM increases with time and is globally estimated to be most common in people aged 55 to 59 years with males experiencing symptom manifestation sooner than females. In 2019, the number of adults diagnosed with T2DM was found to be the highest in China and India estimated with 116.4 million and 77.0 million, respectively. According to the IDF, the number of people with T2DM is expected to increase to 700 million globally.6 The first-line drug therapy for T2DM is generally metformin with several advantages including a lower risk of hypoglycemia and promoting weight loss. Depending on the patient individual glycemic needs, additional medications from different drug classes (eg., glucagon-like peptide 1 [GLP-1] receptor agonists, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 [SGLT2] inhibitors), may be appropriate. Patients experiencing weight loss and hyperglycemia with alarming levels of blood glucose (≥300 mg/dL [16.7 mmol/L]) or A1C (>10% [86 mmol/mol]) should be considered for an early introduction to insulin therapy.7., 8, 9. Studies also confirmed that insulin therapy was associated with a higher incidence of ADR due to the hypoglycemic tendency of its use.10

Previous systematic reviews focused on patients with diabetes' admission to hospital due to medication problems11,12 with several reviews focused on patients with type 2 diabetes in an outpatient setting.13,14 While there are various systematic reviews focusing on the identification of DRP in patients with diabetes in a hospital setting, few systematic reviews have been conducted on the prevalence and risk factors in hospitalized patients specifically with type 2 diabetes. Therefore, the aim of this study was to review and assess literature related to DRP in adult hospitalized T2DM patients, focusing on its prevalence and risk factors.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols was used for this systematic review. Five electronic databases were used for the review including PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. The articles were searched from the inception of the database until June 2022. Various search key terms were used for each database including drug-related problem (DRP), adverse drug reaction (ADR), adverse drug event (ADE), medication error (ME), treatment related problems, medical-problem oriented plan, inpatients, and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Studies on DRPs or subcategories in adult (≥ 18 years) type 2 diabetic hospitalized patients of both genders were included in the review. Type 2 diabetes without or with comorbidities (eg., Hypertension, renal failure) was included in the review. Type 1 diabetes and gestational diabetes were excluded from the review. However, the search was not limited to studies that report only type 2 diabetes. If a study consists of data on DRPs for both type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients, the study was read and data on type 2 diabetes were extracted. If data on type 2 diabetes were unable to be extracted, the study was removed. A similar selection process was applied to studies that consist of data on DRPs involving type 2 diabetes in both inpatient and outpatient settings.

The type of study designs reporting data and prevalence of DRPs in type 2 diabetes hospitalized patients included cross-sectional studies, interventional studies, and cohort studies. Studies included in this review were published in English and Malay.

A software program Endnote (Chandler, AZ, United States) was used for the systematic review where the study retrieved from the database search was transferred. The software facilitates the identification and removal of duplicate articles. Two researchers first screened the articles based on the titles and abstracts. Then, the full articles were screened according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria with reasoning provided for studies that were excluded at this stage. The discrepancies between two researchers were then independently reviewed by the third researcher.

Data pertaining to study details were extracted by two reviewers. Study details include the characteristic of the study (study design, duration, setting, patient demographics), DRPs characteristics (methods to classify DRPs, most common drugs involved, overall incidence), and the risk factors for DRPs.

The methodological quality of the studies included in the systematic review was assessed by two reviewers using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools. The tool uses four answers: ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Unclear’ and ‘Not applicable’.

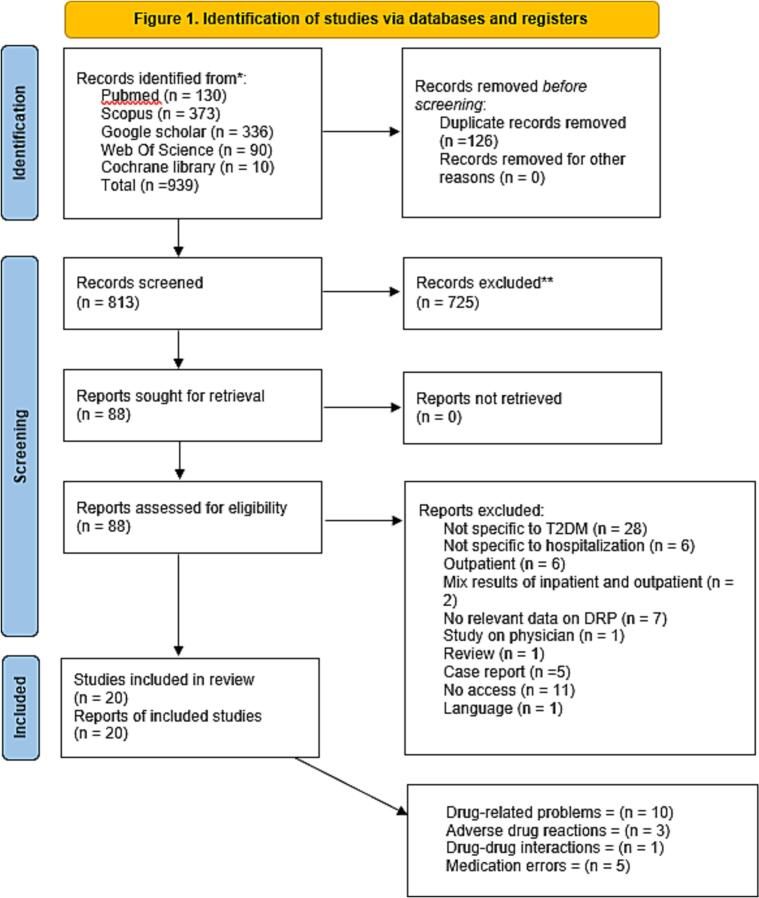

A total of 939 studies were identified from the five databases which subsequently 725 studies were excluded based on the title and abstract. A total of 88 studies were screened in full text whereby 68 studies were excluded for not fulfilling the inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 20 studies met inclusion criteria and were included in this systematic review. Fig. 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart. Characteristics of included studies and drug related problem are presented in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively. PRISMA checklist can be found in Supplementary Information 1.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

| Author/Year and Country | Study design | Identification method | Study subjects | Duration | Setting | Patient characteristics | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corsonello et al., 2005 15 Italy |

Observational study | Incident reports | Renal failure and elderly patient with diabetes |

4 months | Community and university hospitals | Total 2257 Age 72.1 ± 11.4 |

A total of 231 (10.2% of all patients) patients having an ADR diagnosed |

| Varghese et al., 2007 16 USA |

Prospective medical record review | Chart review & Incident reports | Hospitalized patients receiving antihyperglycemic therapy” |

August 16, 2004, to November 15, 2004 | University hospital | Total 2174 | Of the 484 hypoglycemic episodes, 46.9% occurred in patients with type 2 DM |

| Indriani et al., 2010 17 Indonesia |

Retrospective study | Chart review | T2DM patients with non-complication |

January 2009 to March 2010 | Total 14 Age Female 71% |

DRPs drug interactions occur at 29%, ADR of 7%, 14% needed medication, and do not need drugs amounted to 7% | |

| Okayasu et al., 2012 18 Japan |

Retrospective study | Incident reports & chart review | T2DM patients who initially administered metformin |

September 1, 2009 to August 31, 2010 | University hospital | Total 101 Age 60.7 (14–86) |

The overall incidence of diarrhea observed was 26.7% (27 of 101 patients) |

| Kosmalski et al., 2012 19 Poland |

No info | T2DM patients using metformin |

2009 to 2011 | Department of Internal Diseases, Diabetology and Clinical Pharmacology of the Medical University of Lodz | Total 558 Age 66.65 ± 12.73 Female |

275 patients were found to be contraindicated and despite this 120 of them were using this medication at an average dose of 1793.91 ± 701.61 mg. Only three patients reported moderate dyspepsia | |

| Inamdar et al., 2016 20 India |

Survey study | Survey | Elderly patients with T2DM |

– | Elderly in general medicine department (general ward and intensive care unit) | Total 123 Age 68.84 ± 7.33 Female 47 (38%) |

364 DRPs were identified in all 123 study subjects |

| Herman et al., 2016 21 Indonesia |

Retrospective data collection | Chart review | Elderly T2DM patients | January to December of 2013 | Inpatient private hospital | Total 50 Age 65.0 ± 4.46 Female 35 (70%) |

15 (30%) of 50 patients identified with inappropriate use of drug by Stopp criteria |

| Zazuli et al., 2017 22 Indonesia |

Prospective study | No info | DRPs in T2DM patients with hypertension |

October to December 2015 | T2DM patient with HTN admitted to inpatient ward | Total 90 Age Female 74 (82.8%) |

261 DRPs were identified |

| Hidayati et al., 2018 23 Indonesia |

Retrospective descriptive study | Incident reports | T2DM patients with complications of comorbidities |

January to December 2016 | Inpatient pharmacy depo | Total 49 Age Female 28 (57.14%) |

Drug interaction of metformin with simvastatin was found in 3 people (6.12%) |

| Maharani et al., 2018 24 Indonesia |

Prospective study | Chart review & incident reporting | DRPs in hospitalized geriatric patients with diabetes mellitus |

February to April 2015 | Geriatric patient admitted to the army hospital | Total 26 Age > 60 Female 19 (73.1%) |

166 DRPs were identified from 299 drug treatments obtained for 26 patients |

| Salam et al., 2018 25 Indonesia |

Observational study with a cross-sectional approach | Chart review | DRPs in T2DM patients with complications of macrovascular disease |

July to August 2018 | T2DM with macrovascular complication admitted to hospital | Total 20 Age Female 14 (70%) |

100% potential problems and 35,3% problem manifestations consisting of adverse drug reactions, non-optimal treatment effects, untreated indications, and treatment unnecessary |

| Siregar et al., 2018 26 Indonesia |

Retrospective observational study | Chart review | DRPs among T2DM patients |

January to June 2016 | T2DM patient with HTN admitted to hospital | Total 30 Age Female 17 (56%) |

DRPs in the category of drug interactions in theory was potentially 220 times (90%). There were 18 cases of drug doses too low and 18 cases of drug doses too high |

| Hussain et al., 2019 27 India |

Prospective interventional study | Chart review, direct observation (pharmacist intervention) & Interview (physician & patient) | Diabetes mellitus patients with hypertension |

Six months | T2DM patient with HTN admitted to hospital | Total 122 Age 64.3 ± 1.05 Female 63 (52%) |

99 patients (81%) experience drug-drug interactions |

| Indriani et al., 2019 28 Indonesia |

Retrospective cross-sectional | Chart review | T2DM patients in the ward patient |

May to June 2018 (2 months) | Total 100 Age Female 58% |

Most common DRPS is drug interactions that is 94.62% | |

| Nzayisenga et al., 2019 29 Africa |

Retrospective cross-sectional study | Chart review | DRPs among T2DM patients with hypertention |

January 2013 to December 2017 | T2DM patient with HTN admitted to hospital | Total 385 Age Female 238 (61.56%) |

The prevalence of DRPs was 81.29% (313/385) |

| Acharya et al., 2020 30 India |

Retrospective observational study | Chart review | T2DM patients with comorbidities |

August 2019 to March 2020 | Tertiary care hospital | Total 250 Age 62.5 ± 12.86 Female 72 (28.8%) |

226 DRPs with an average of 0.91 DRP per patient |

| Inamdar et al., 2020 31 India |

Prospective interventional study | Chart review & direct observation (pharmacist intervention) | DRP among T2DM patients |

Six months | General medicine department | Total 107 Age Female 43 (40.21%) |

A total of 278 DRPs were identified after assessing 107 study |

| Sharma et al., 2020 32 India |

Cross-sectional study | Chart review | Potential Inappropriate medication use among T2DM patients |

August 2019 to January 2020 | Elderly in tertiary care hospital | Total 150 Age 68.85 ± 5.51 Female 68 (45,3%) |

Overall, 58 (38.7%) patients were prescribed at least one PIM, 37 (24.7%) were prescribed two PIMs, and 16 (10.7%) were prescribed ≥ three PIMs |

| Mader et al., 2022 33 Austria |

Single-center survey | Questionnaire | T2DM patients with medication errors |

April 2017 to February 2019 | Department of Endocrinology and Diabetology | Total 100 |

25% of patients already suffered at least one drug error, whereby prescribing a wrong dose seemed to be the most common type of error |

| Nigussie et al., 2022 34 Pakistan |

Prospective cross-sectional study | Chart review (data abstraction form) & interview for missing files | Inappropriate antidiabetic medication therapy among T2DM patients |

November 2021 to January 2022 | Medical and surgical wards | Total 138 Age 58 ± 16.1 Female 80 (58%) |

The overall prevalence of inappropriate anti-diabetic medication therapy was 70.3% |

Table 2.

Drug-related problem characteristics.

| Author/Year and Country | Method of classify DRPs | Most common drugs | Overall incidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corsonello et al., 2005 15 Italy |

– | – | 231 (10.2% of all patients) ADR identified |

| Varghese et al., 2007 16 USA |

Establish operational definitions | Specific drug class study, Antihyperglycemic (no specific drug name mentioned) | Of the 484 hypoglycemic episodes, 46.9% occurred in patients with type 2 DM, |

| Indriani et al., 2010 17 Indonesia |

Drug Information Handbook (DIH) edition 14 MIMS Indonesia edition 72,007/2008 Drug Interaction Facts (DIF) ISO Indonesia volume 442,009/2010 Informatory Obat Indonesia (IONI) 2000. |

– | DRPs drug interactions occur at 29%, ADR of 7%, 14% needed medication, and do not need drugs amounted to 7% |

| Okayasu et al., 2012 18 Japan |

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 4.0) | Specific drug study (metformin) | The overall incidence of diarrhea observed was 26.7% (27 of 101 patients) |

| Kosmalski et al., 2012 19 Poland |

– | Specific drug study (metformin) | 275 patients were found to be contraindicated and despite this 120 of them were using this medication 3 patients reported moderate dyspepsia |

| Inamdar et al., 2016 20 India |

PCNE | Antihypertensives (108)- DDI, DWI Antidiabetics (96)- metformin + metoprolol/rabeprozol/insulin DDI /ADR Antibiotics (41) Anti-emetics (29) Antiplatelets (36) |

364 DRPs were identified in all 123 study subjects. |

| Herman et al., 2016 21 Indonesia |

Start-Stopp criteria | – | 15 (30%) of 50 patients identified with inappropriate use of drug |

| Zazuli et al., 2017 22 Indonesia |

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015 Consensus guidelines on the management and prevention of type II diabetes mellitus in Indonesia 2015 Drug Information Handbook 2011–2012. 20th |

– | 261 DRPs were identified |

| Hidayati et al., 2018 23 Indonesia |

Stockley 2008; Stockley 2010 Drug interaction book Drug interaction journal study on T2DM patient with hyperlipidemia |

Metformin + simvastatin 3 | Drug interaction of metformin with simvastatin was found in 3 people (6.12%) |

| Maharani et al., 2018 24 Indonesia |

Pharmacotherapy A Pathophysiologic Approach, 7th edition Drug Information Handbook, 17th edition Geriatric Dosage Handbook 2005 Journal of Pharmacy of Clinic MIMS ISO 2014 Micromedex PCNE |

Ranitidine, omeprazole with/without sucralfate or rebamipide Antibiotics, ACE inhibitor- DDI hypo/hyperglycemia |

166 DRPs were identified from 299 drug treatments obtained for 26 patients |

| Salam et al., 2018 25 Indonesia |

PCNE | – | 100% potential problems and 35,3% problem manifestations consisting of adverse drug reactions, non-optimal treatment effects, untreated indications, and treatment unnecessary |

| Siregar et al., 2018 26 Indonesia |

– | – | DRPs in the category of drug interactions in theory was potentially 220 times (90%). 18 cases of drug doses too low and 18 cases of drug doses too high. |

| Hussain et al., 2019 27 India |

Helper Strand classification Lexicomp Micromedex |

Aspirin, clopidogrel, warfarin, atorvastatin and some drugs acting on the CNS- DDI Antihypertensives- ADR |

99 patients (81%) experience DDI |

| Indriani et al., 2019 28 Indonesia |

PCNE American Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes 2018 Drug Interaction Drug Information Handbook Indonesian Endocrinology Society |

– | Most common DRPS is drug interactions that is 94.62% |

| Nzayisenga et al., 2019 29 Africa |

PCNE | Antihypertensive (270/385) Antidiabetics (267/385) Mainly drug/dose selection |

The prevalence of DRPs was 81.29% (313/385) |

| Acharya et al., 2020 30 India |

Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe (PCNE) classification Helper Strand classification Micromedex Medscape Lexicomp Drugs.com |

Metformin + ciprofloxacin 2 Insulin |

226 DRPs with an average of 0.91 DRP per patient |

| Inamdar et al., 2020 31 India |

PCNE | Metformin + Metoprolol 64 (33.16%) Metformin + Ranitidine 51 (26.42%) |

278 DRPs were identified after assessing 107 study |

| Sharma et al., 2020 32 India |

Beers Criteria 2019 | Short-acting insulin Glimepiride PPI- PIM Clonazepam |

58 (38.7%) patients were prescribed at least one PIM, 37 (24.7%) were prescribed two PIMs, and 16 (10.7%) were prescribed ≥ three PIMs |

| Mader et al., 2022 33 Austria |

No reference (survey study from patient perspective) | – | 25% of patients already suffered at least one drug error, whereby prescribing a wrong dose seemed to be the most common type of error |

| Nigussie et al., 2022 34 Pakistan |

Cipolle's DRP classification | Biguanides (64) Insulin (61) |

The overall prevalence of inappropriate anti-diabetic medication therapy was 70.3% |

A wide range of scores was allocated across the 20 studies with an overall of standard quality. Three studies used an inappropriate method (purposive sampling) of recruiting participants.21,25,26 Individual quality assessment scoring is presented in Supplementary Information 2.

Characteristics of studies included

Retrospective studies constituted the majority of the articles (40%), with different various observational methodological approaches (Table 1). Two prospective studies included were conducted with interventional methods implemented. Most of the studies were carried out in Asia (75%): Indonesia,17,21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26.,28 India,20,27,30., 31, 32 Japan,18 and Pakistan,34 followed by Europe (15%): Italy,15 Poland,19 Austria,33 Africa (5%)29 and North America (5%).16 The majority of the studies were conducted in the general hospital ward with only 2 studies reported to have been conducted in the endocrinology and diabetology department.19,33

In all of the 20 studies, a total of 6844 patients were recruited with only adults (≥ 18 years). Of these, five studies were focused only on geriatric patients (≥ 60 years).15,20,21,24,32

The identification of DRPs using chart review only was utilized in eight studies.17,21,25,26,28, 29., 30.,32 Five studies implemented more than one method of detecting DRPs.16,18,24,27,31,34 Five studies used incident reports (with/without methods combination) for adverse drug reactions and drug interactions.15,16,18,23,24 Two studies used surveys or questionnaires as means of collecting data on DRPs from the patient.20,33 Two studies do not provide information on methods of detecting DRPs.19,22 In all of the 20 studies, a total of 27 sources of information were used to detect and classify DRPs. Eight studies used one source only.18,20,21,25,29,31,32,34 Seven studies used more than one source.17,22, 23, 24,27,28,30 One study establishes operational definitions as its source.16 No available sources were mentioned in four studies.15,19,26,33 Micromedex was the most used source of information (n = 3)24,27,30 followed by Lexicomp (n = 2)27,30 and American Diabetes Association (n = 2).22,28

The overall prevalence of DRPs in all 20 studies ranged from 7% to 94%. One retrospective study reported antidiabetic drug interactions only and found 6.12% of 49 patients experiencing DDIs. Three different sources were used to identify and classify the DRPs detected.

The majority of the studies investigated DRPs as a whole (n = 11) with no specification on the type of DRPs investigated, for example DDI, ADR, therapeutic effectiveness and dosage problems. Five of these studies identified DDIs as the main type of DRP found with a range of 29% to 94%.17,20,27,28,31 One retrospective study found that 37.6% of 250 patients have insufficient clinical information during the hospitalization period.30 The necessary clinical parameters for monitoring diabetes including blood glucose levels were not documented. Only one study reported therapeutic effectiveness problems as the common DRP with a frequency of 50.6%.24 The problems observed include the medication being ineffective and the failure of treatment. One study reported drug choice problems in 55.17% of 90 patients with the primary source of DRPs being drug/dose selection, which was similarly found in another study conducted by Nyazisenga and colleagues (2019). with frequencies of 62.16% and 36.97% respectively.22,29 No drug prescribed with clear indication has the highest frequency of 25.3% under the drug choice problem subdomain.

Two studies reported ADR only with one study focused on a specific antidiabetic drug (metformin) and another on a specific drug class (antihyperglycemic) with no drug name mentioned.16,18 In a study of ADR on a specific drug (metformin), the occurrence of diarrhea was found in 26.7% of 101 participants while a study of ADR on a specific drug class (antihyperglycemic) found 46.9% of 484 hypoglycemic episodes manifested in T2DM patients.

In this review, nine studies reported the most common drugs involved in DRPs, the majority of the drugs involved were antidiabetics, antihypertensives, antiplatelets and antibiotics. Four studies reported antidiabetics (metformin) to be commonly involved in DDIs.20,23,30,31 Inamdar and colleagues (2020) reported a common DDIs of metformin with metoprolol (33.1%) and ranitidine (26.4%).31 One study reported common DDIs with cardiovascular medications such as aspirin, clopidogrel, warfarin, and atorvastatin whereas antihypertensives such as hydrochlorothiazide and furosemide are associated with a higher occurrence ADRs.27

Five studies examined medication errors such as potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) and dosage problems.19,21,32, 33, 34 One of the studies investigated a specific drug (metformin) use in the elderly and observed 82% of 335 patients to be contraindicated with only three reported dyspepsias during hospital stay.19 Two studies investigated PIM in the elderly population with a prevalence of 30% and 74% having at least one PIM.21,32 Two studies reported a ME prevalence of 25% having at least one ME and 70.3% respectively with the most common problem associated with dosage problems.33,34 The study with a 70.3% prevalence further specifies 29.2% receiving doses too high and 27.9% doses too low.34 These findings aligns with another study that reported up to average 9.35 treatment related problems per patient, with 53% considered as major and 28% as moderate treatment related problems in hospitalized internal medicine patients in Jordan.35

Three studies investigated DRPs in specific drugs or drug classes (metformin, antihyperglycemics).16,18,19

Thirteen studies included the risk factors contributing to DRPs. The most prevalent risk factors for DRPs involved the presence of comorbidities found in six studies with the majority having hypertension (HTN).20,22,27,28,31,34 Five studies reported on age,20,24,28,29,34 four studies on the number of medications,22,27, 28, 29. another four studies on polypharmacy,20,29,31,32 and three studies on gender.18,28,32 The list of risk factors reported in the studies is presented in Supplementary Information 3.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we examine the overall prevalence of DRPs in T2DM hospitalized patients with risk factors influencing DRPs and the most common drugs involved with the DRPs. In this review, ten studies investigated DRPs as a whole, followed by six studies on ME, three studies on ADRs and only one study specifically on DDIs.

The ideal outcome of treatment for T2DM patients can be defined generally as attaining the targeted glycemic control mainly by the adjustments in lifestyle together with the initiation of drug therapy. Therapeutic success can be more thoroughly defined as slowing or halting disease development and minimizing the risk factors associated with disease complications.36 The first line of drug therapy for diabetes is the initiation of metformin with a slow intensification of therapy depending on the disease progression with the goal of achieving targeted glycemic control as stated previously.7 The presence of DRPs has a potential negative impact on the outcome of diabetes treatment as well as any other conditions. The consequences of DRPs interfere with the desired clinical outcome worsening patient quality of life which emphasizes the importance of pharmaceutical care in preventing unfavorable health outcomes.37

One of the ways to diagnose diabetes is by using the A1C test to measure the average blood glucose for the past two to three months. A1C result showing a value of 6.5% and above indicates an individual is diagnosed with diabetes. Another test known as fasting plasma glucose (FPG) is performed during fasting when an individual is not consuming food or drinks for at least eight hours to measure the fasting blood glucose level. American Diabetes Association defines diabetes mellitus when an individual's fasting blood glucose value is 126 mg/dL and above.38 In this review, no studies specified the test used to diagnose patients with type 2 diabetes. Before the progression to T2DM, an individual often goes through a stage known as prediabetes in which they show a high level of blood glucose but are still not considered high enough to be identified as T2DM.39

The methods for identification of DRPs used in the studies include chart reviews, incident reports, surveys, direct observation, and minimal interviews. The majority of studies included in this review used chart review as the primary method for the detection of DRPs.16, 17, 18,21,24, 25, 26., 27, 28, 29., 30., 31, 32,34 The use of chart review at the prescription stage demonstrates a higher detection of DRPs with low clinical significance. The outcome of the chart review is dependent on the ability of the reviewer to detect the triggers.40,41 The second most used method was incident reporting.15,16,18,23,24 Five studies implemented more than one method of detecting DRPs with combinations of chart review with direct observation, interview, or incident reports.16,18,24,27,31,34

In this systematic review, a wide variety of medications was involved with DRPs in all 20 studies. Most of the studies did not specify investigating one specific drug class only however, results presented in the studies were mostly associated with class of antidiabetic medications only.

Two studies performed an investigation on a specific drug which was metformin.18,19 Overall, the most common antidiabetic drug classes associated with DRPs in this review were biguanide (metformin), followed by cardiovascular drugs mainly antihypertensives with several studies specifically investigating DRPs in T2DM patients with HTN as comorbidity. The higher prevalence of comorbidities has greater exposure to DRPs as the presence of such complex conditions is often associated with multiple drug therapy, hence, the patient comorbid condition and therapy should be carefully reviewed ensuring appropriate prescribing of medications and early prevention of DRPs.42

Antihypertensives were found to be the most commonly involved in DRPs in three studies with one identifying the ACE inhibitor drug class mainly involved with DRPs. Multiple drug therapy regimens including antihypertensives with other cardiovascular medications potentially reduces the effect of therapy and have greater exposure to adverse effects.43

Metformin demonstrates a significant involvement with DRPs in five studies.20,23,30,31,34 The DRPs involving metformin in these studies were mostly associated with DDIs with other non-antidiabetic drug classes including metoprolol, ranitidine, simvastatin, and ciprofloxacin. The mechanism of interaction between metformin with beta-blockers and H2 receptor blockers was mainly through inhibition of either organic cation transporters (OCT) or multidrug and toxin extruders (MATE) transporters or both. The reduction in metformin renal clearance and increase in metformin plasma concentration further increases the risk of developing metformin-associated lactic acidosis.44,45 Therefore, prescribers should be alert for patients with medications that have an effect on the OCTs and MATEs transporters.

Out of all twenty studies included, thirteen mentioned the risk factors contributing to DRPs. In all of the thirteen studies, a total of 23 risk factors were observed with the most prevalent being associated with the presence of comorbidities which increases number of medications reported in six studies with the majority having hypertension.20,22,27,28,31,34 The risk of developing hypertension in people with diabetes is higher as they often manifest insulin resistance compared to normal individuals.46 This was followed by the number of medications reported in four studies22,27, 28, 29. and polypharmacy in another four studies.20,29,31,32 Overall, the risk factor was mostly involved with the high number of prescribed medications resulting in higher exposure to DRPs.47 The exposure to DRPs can be reduced with the act of deprescribing (“a systematic approach to identify and discontinue medications in which potential harm outweighs the benefit and medications with unclear benefit”).48

Strength and limitations

In the previous systematic reviews, the majority are focused on DRPs in the general inpatient diabetic population with a few on T2DM in inpatient and outpatient settings. This systematic review is one of the few that conducted reviews on the available literature on DRPs in hospitalized patients specifically with T2DM. Five electronic databases were used to search appropriate articles with various search strategies used in each database. The data on the most common drugs or drug classes involved with DRPs were limited. Several studies reported the name of common drugs involved only when it came to DDIs. The common drug or drug classes involved were stated without describing the DRPs it was associated with. Additionally, a few studies performed non-random sampling which may possibly generate highly biased data results. One of the studies that carried out a questionnaire study design based on patient perspective will have a risk of the individual not having the appropriate knowledge or recollection of the DRPs experienced to provide responses accurately affecting the results of the study.

From this systematic review, it can be observed that hospitalized T2DM patients have a high prevalence of DRPs with the most common being DDIs. Prescribers should be more cautious with this population, especially those who have co-morbidities as it increases the number of medications and risk of DDIs. The risk of DDIs could be reduced by regularly reviewing the patient list of medications and using a reliable source of information guidelines on common drug interaction with antidiabetics. Future studies on DRPs prevalence in hospitalized T2DM patients are necessary for further development of approaches in identifying, resolving, and preventing DPRs improving patient clinical outcomes.49 Recently, a new tool, The Alsayed_v1 tools, encompassing treatment assessments, medical-problem oriented plan, and care plan, have been validated and applied to real patient cases.50 This comprehensive tool can be modified for clinical pharmacists to efficiently identify, categorize, and address drug-related problems for T2DM.

Conclusion

In this systematic review, the occurrence of DRPs in T2DM hospitalized patients was observed to be high with a diverse range among the included studies. DDIs were reported to be most prevalent in a majority of the studies. Antidiabetics (metformin) and antihypertensives showed a significant involvement with DRPs. The risk factors that were highly associated with DRPs were the presence of comorbidities (HTN), the number of medications and polypharmacy.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Institute of Research and Community Services (Lembaga Penelitian dan Pengabdian Masyarakat, LPPM) Universitas Airlangga, Surabaya, Indonesia.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcsop.2023.100348.

Contributor Information

Andi Hermansyah, Email: andi-h@ff.unair.ac.id.

Ching Siang Tan, Email: tcsiang@kpjuc.edu.my.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

PRISMA checklist.

Risk factors for drug-related problems

Quality assessment scores

References

- 1.Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe Association Pharmaceutial Care Network Europe (PCNE) Classification for drug-related problems V9. 1. 2020. https://www.pcne.org/upload/files/417_PCNE_classification_V9-1_final.pdf Available online. Accessed 12 Aug 2023.

- 2.Salmasi S., Wimmer B.C., Khan T.M., Zaidi S.T.R., Ming L.C. A proposed stepwise approach to reducing medication errors in older people. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2018;14(2):207–209. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xue Qin Q.N., Ming L.C., Abd Wahab M.S., Tan C.S., Yuda A., Hermansyah A. Drug-related problems among older people with dementia: a systematic review. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2023;19(6):873–881. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2023.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Bemt P.M., Egberts T.C., de Jong-van den Berg LT, Brouwers J.R. Drug-related problems in hospitalised patients. Drug Saf. 2000;22(4):321–333. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200022040-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aronson J.K., Ferner R.E. Clarification of terminology in drug safety. Drug Saf. 2005;28(10):851–870. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200528100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tinajero M.G., Malik V.S. An update on the epidemiology of type 2 diabetes: a global perspective. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2021;50(3):337–355. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2021.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes—2022 abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diab. 2022;40(1):10–38. doi: 10.2337/cd22-as01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfeiffer A.F., Klein H.H. The treatment of type 2 diabetes. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111(5):69–81. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0069. [quiz 2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Diabetes Federation Guideline Development Group Global guideline for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014 Apr;104(1):1–52. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.10.001. Epub 2014 Feb 5. PMID: 24508150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCall A.L. Insulin therapy and hypoglycemia. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2012;41(1):57–87. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prasad T.D., Ranganayakulu D., Devanna N. Prescribing pattern and medication related problems in hospitalized diabetic patients: a hospital-based study. J Pharm Res Int. 2021;33(5):12–21. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor J.E., Campbell L.V., Zhang L., Greenfield J.R. High diabetes prevalence and insulin medication errors in hospital patients. Intern Med J. 2018;48(12):1529–1532. doi: 10.1111/imj.14124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abu Farha R.K., Mukattash T.L., Qudah R., Alkhalaileh W., Alsaffar S. Drug-related problems and health-related quality of life in outpatients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study from Jordan. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2019;10(3):303–309. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adisa R., Osoba D. Evaluation of drug therapy problems among outpatient hypertensive and type-2-diabetic patients at a tertiary hospital, South-West Nigeria. Niger J Pharm Res. 2019;15(2):127–141. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corsonello A., Pedone C., Corica F., et al. Concealed renal failure and adverse drug reactions in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(9):1147–1151. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.9.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varghese P., Gleason V., Sorokin R., Senholzi C., Jabbour S., Gottlieb J.E. Hypoglycemia in hospitalized patients treated with antihyperglycemic agents. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(4):234–240. doi: 10.1002/jhm.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Indriani D.V. Sanata Dharma University; 2010. Evaluation of drug related problems (drps) in non-complicated type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in the inpatient unit of panti rini hospital yogyakarta from January 2009 to March 2010: Thesis.http://www.library.usd.ac.id/Data%20PDF/F.%20Farmasi/Farmasi/068114080_Full.pdf Available online. Accessed 11 Aug 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Okayasu S., Kitaichi K., Hori A., et al. The evaluation of risk factors associated with adverse drug reactions by metformin in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35(6):933–937. doi: 10.1248/bpb.35.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosmalski M., Drozdowska A., Sliwinska A., Drzewoski J. Inappropriate metformin prescribing in elderly type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients. Adv Med Sci. 2012;57(1):65–70. doi: 10.2478/v10039-012-0017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Inamdar S., Kulkarni R. Drug related problems in elderly patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetology. 2016;7(1):1. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Herman H., San I.P., Rahmawati Azizah R.N. Inappropriate use of the drugto elderly patients with type-II diabetes mellitus in Makassar Indonesia. Pharm Lett. 2016;8(3):154–158. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zazuli Z., Rohaya A., Adnyana I.K. Drug-related problems in type 2 diabetic patients with hypertension in Cimahi, West Java, Indonesia: a prospective study. Int J Green Pharmacy. 2017;11(2):S298–S304. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hidayati N.R., Oktaviani P., Setyaningsih I. Medical Sains: Jurnal Ilmiah Kefarmasian. 2(2) 2018. Overview of drug interactions of type 2 diabetes mellitus with comorbid disease medications in inpatient patients at rsud gunung jati, cirebon city, in 2016.Gambaran interaksi obat diabetes melitus tipe 2 dengan obat penyakit penyerta pada pasien rawat inap di rsud gunung jati kota cirebon tahun 2016; pp. 58–64. Available online: https://ojsstfmuhammadiyahcirebonacid/indexphp/iojs/article/view/49: Access 11 Aug 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maharani D.D., Syafhan N.F., Hersunaryati Y. Drug-related problems in hospitalized geriatric patients with diabetes mellitus. Int J Appl Pharmac. 2018;10(Special Issue 1):142–147. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salam N.S. Identifikasi drug related problems (drps) pada pasien diabetes mellitus tipe 2 dengan komplikasi penyakit makrovaskular. Universitas Islam Negeri Alauddin Makassar; 2018. Identification of drug related problems (drps) in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with macrovascular disease complications. . http://repositori.uin-alauddin.ac.id/16744/ [Google Scholar]

- 26.Siregar DA. Identification of drug related problem in diabetes mellitus type 2 patients with hypertension at 5th floor of teratai in general hospital center (RSUP) Fatmawati Period January–June 2016. https://repository.uinjkt.ac.id/dspace/handle/123456789/42350: Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta.

- 27.Hussain M.A., Firdous S., Uz M.E. Role of clinical pharmacist in patients with diabetes and hypertension: a prospective study. World J Pharm Res. 2019;8(6):842–858. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Indriani L., Oktaviani E. Bandung International Conference on Collaborative Health Research. 2019. Drug related problems (DRPs) identification on diabetes melitus type 2 ward patients with complication. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nzayisenga J. Mount Kenya University Rwanda; 2019. Drug-Related Problems among Type II Diabetes Mellitus Patients with Hypertension: A Cross-Sectional Study. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Acharya Dr L.D. Study of Drug Related Problems in Type Ii Diabetes Mellitus Patients with Comorbidities in a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Retrospective Study. https://impressions.manipal.edu/mcops/9:

- 31.Inamdar S.Z., Kulkarni R.V., Akhila V. Pharmacist led assessment of drug related problems in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Int J Psychosocial Rehab. 2020;24(4) doi: 10.37200/IJPR/V24I4/PR201059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharma R., Chhabra M., Vidyasagar K., Rashid M., Fialova D., Bhagavathula A.S. Potentially inappropriate medication use in older hospitalized patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Pharmacy (Basel) 2020;8(4) doi: 10.3390/pharmacy8040219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mader J.K., Aberer F., Drechsler K.S., et al. Medication errors in type 2 diabetes from patients’ perspective. PLoS One. 2022;17(4 April) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0267570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nigussie K.A., Shegena E.A., Stephen O.P., Namugambe J.S., Yadesa T.M. Prevalence and factors associated with inappropriate anti- diabetic medication therapy among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients at the medical and surgical wards of Mbarara regional referral hospital, Uganda. PLoS One. 2022;17(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0270108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aburuz S.M., Bulatova N.R., Yousef A.M., Al-Ghazawi M.A., Alawwa I.A., Al-Saleh A. Comprehensive assessment of treatment related problems in hospitalized medicine patients in Jordan. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(3):501–511. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9497-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stolar M.W. Defining and achieving treatment success in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(12 Suppl):S50–S59. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garin N., Sole N., Lucas B., et al. Drug related problems in clinical practice: a cross-sectional study on their prevalence, risk factors and associated pharmaceutical interventions. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):883. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80560-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2022. Diabetes Care. 2021;45(Supplement_1):S17–S38. doi: 10.2337/dc22-S002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cali A.M., Caprio S. Prediabetes and type 2 diabetes in youth: an emerging epidemic disease? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diab Obes. 2008;15(2):123–127. doi: 10.1097/MED.0b013e3282f57251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manias E. Detection of medication-related problems in hospital practice: a review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(1):7–20. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montesi G., Lechi A. Prevention of medication errors: detection and audit. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(6):651–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kefale B., Tegegne G.T., Kefale Y., Molla M., Ewunetei A., Degu A. Magnitude and determinants of drug therapy problems among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients with hypertension in Ethiopia. SAGE Open Med. 2020;8 doi: 10.1177/2050312120954695. 2050312120954695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kusumawardani L.A., Andrajati R., Nusaibah A. Drug-related problems in hypertensive patients: a cross-sectional study from Indonesia. J Res Pharm Pract. 2020;9(3):140–145. doi: 10.4103/jrpp.JRPP_20_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pakkir Maideen N.M., Jumale A., Balasubramaniam R. Drug interactions of metformin involving drug transporter proteins. Adv Pharm Bull. 2017;7(4):501–505. doi: 10.15171/apb.2017.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stage T.B., Brøsen K., Christensen M.M. A comprehensive review of drug-drug interactions with metformin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2015;54(8):811–824. doi: 10.1007/s40262-015-0270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petrie J.R., Guzik T.J., Touyz R.M. Diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: clinical insights and vascular mechanisms. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34(5):575–584. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen Y.C., Fan J.S., Chen M.H., et al. Risk factors associated with adverse drug events among older adults in emergency department. Euro J Intern Med. 2014;25(1):49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dahal R., Bista S. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2022. Strategies to Reduce Polypharmacy in the Elderly. StatPearls. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bergkvist Christensen A., Holmbjer L., Midlöv P., et al. The process of identifying, solving and preventing drug related problems in the LIMM-study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2011;33(6):1010–1018. doi: 10.1007/s11096-011-9575-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Alsayed A.R., Al-Dulaimi A., Alnatour D., Awajan D., Alshammari B. Validation of an assessment, medical problem-oriented plan, and care plan tools for demonstrating the clinical pharmacist’s activities. Saudi Pharm J. 2022;30(10):1464–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2022.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA checklist.

Risk factors for drug-related problems

Quality assessment scores