Abstract

Background

Patient compliance with regimens is one of the most researched and least-understood behavioral concerns in the healthcare profession due to the many meanings employed in multidiscipline over time. Thus, a thorough examination of the idea of patient compliance is necessary.

Objective

This paper aims to explore and identify the essence of the term patient compliance to achieve an operational definition of the concept.

Method

Walker and Avant’s eight-step approach was used. A literature search was conducted using keywords of patient compliance AND healthcare profession from five databases: PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, and Cochrane database, published from 1995 to 2022.

Results

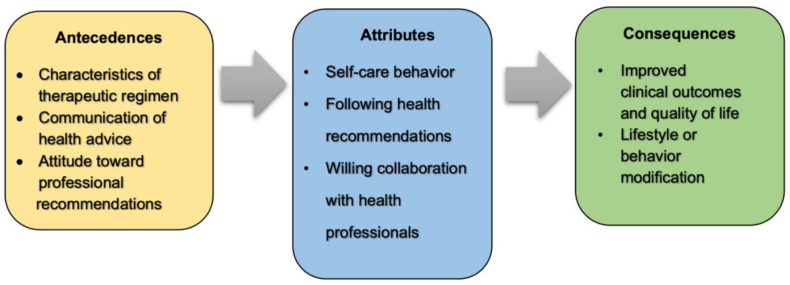

The attributes of patient compliance include 1) self-care behavior, 2) following health recommendations, and 3) willing collaboration with health professionals. Antecedents of patient compliance were characteristics of therapeutic regimens, communication of health advice, and patients’ attitudes toward professional recommendations. Consequences include improved clinical outcomes, quality of life, and lifestyle or behavior modification.

Conclusion

This concept analysis offers a valuable perspective on patient compliance that guides the nursing practice in providing better interventions to promote compliance among patients.

Keywords: compliance, concept analysis, healthcare profession, patient

Background

Patient compliance is crucial to the successful management of chronic diseases. Patient compliance with medications and health recommendations contributes to disease control (Ekinci et al., 2017; Muliyil et al., 2017) and better clinical outcomes in chronic illnesses (Aremu et al., 2022). Unfortunately, low levels of patient compliance have been reported in the literature (Ehwarieme et al., 2018; Sen et al., 2020). Low patient compliance leads to health deterioration and complications. Patients with chronic diseases who have previously been hospitalized are frequently readmitted for reasons such as non-compliance with therapy and lifestyle adjustments (Tun, 2021). Non-compliance can lead to ineffective treatment outcomes, higher hospitalization rates, reduced discharge rates, complications, increased healthcare costs, and death (Desai et al., 2019).

However, the patient compliance concept in the healthcare profession remains ambiguous due to the many meanings employed in multidiscipline over time. The precise identifying characteristics may help the healthcare profession to communicate with one another clearly. As a result, a thorough examination of the idea of patient compliance is necessary (Cheraghi et al., 2021; Walker & Avant, 2019). Clarification and comprehension of the patient compliance idea will improve knowledge of patient compliance as a complicated notion, including a variety of circumstances, actions, and settings. Concept analysis helps to build valid and accurate measuring methods and scales for assessing various elements of patient compliance. It aids in determining the essential indications and dimensions that must be considered when measuring compliance. Healthcare practitioners can create interventions that target specific barriers to compliance by understanding the underlying components (Costa et al., 2021). Furthermore, by conducting a concept analysis of patient compliance, researchers, healthcare professionals, and policymakers can gain a deeper understanding of the concept, leading to improved patient outcomes, enhanced healthcare delivery, and the development of effective interventions (Bunting & de Klerk, 2022). This paper aimed to clarify the patient compliance concept to strengthen understanding in informing nursing interventions to promote patient compliance.

Concept Analysis of Patient Compliance

Walker and Avant’s eight-step concept analysis approach was used in this study (Walker & Avant, 2019). The steps consist of 1) selection of a concept, 2) determination the aim of analysis, 3) identification of all concept uses, 4) determination of defining attributes, 5) identification of a model case, 6) identification of borderline and contrary cases, 7) identification of antecedents and consequences, and 8) identification of empirical referent.

Selection of the Concept

The concept of compliance was chosen for examination because of its centrality in nursing practice. Compliance is a multifaceted phrase that involves self-perception, which varies between therapist and patient. The idea of compliance was employed in clinical practice, yet the genuine meaning of compliance varied from person to person, even among healthcare practitioners. The terms compliance and adherence are interchangeable among healthcare practitioners, but there are numerous differences between the two terms. Adherence involves patients actively choosing to follow the prescribed treatments as they are responsible for their own health, whereas compliance usually indicates passive actions whereby the patients follow a list of orders from the physician. In other words, adherence is a more proactive, positive habit where patients adjust their lifestyles, while compliance is the patients’ act of doing as they are told (Mir, 2023). Obedience, another concept, reflects doing as expected, similar to patient compliance, but the action may be against one’s belief or will (Martin & Bull, 2008). Patient compliance was selected to assist nurses in better understanding this concept.

Determination of the Aim of the Analysis

Specifying the analysis’s goal is the second step in the concept analysis process to emphasize how the findings can be applied (Walker & Avant, 2019). This analysis aimed to clarify the patient compliance concept to strengthen nurses’ understanding, leading to better interventions.

Identification of All Concept Uses

Patient compliance consists of two words: patient and compliance. “Patient” refers to an individual undergoing medical care, particularly at a hospital (Oxford Learner's Dictionaries, 2023a). “Compliance” derives from the Latin word complire, meaning to fill up and, thus, carry out a behavior, transaction, or process and keep a commitment. Oxford Learner's Dictionaries (2023b) describe compliance as following commands or following through on requests made by those in power.

A literature review was conducted to examine the uses of patient compliance on the PubMed, Medline, CINAHL, ProQuest, ScienceDirect, and Cochrane databases, published from 1995 to 2022. The keywords used during the literature search were patient compliance AND healthcare profession. The authors considered using ideas from various fields, including medicine, nursing, and other health-related arenas (Walker & Avant, 2019). The term compliance was not clearly defined in several of the papers reviewed. Therefore, the literature search revealed only 17 papers that provided a clear definition of patient compliance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions of patient compliance

| Author (Year) | Field | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Murphy and Coster (1997) | Medicine | The capacity and willingness of a person to follow medical advice, take prescription medication as directed, attend regular appointments at the doctor’s office, and carry out advised examinations |

| Kyngäs (2000) | Nursing | - Cognitive-motivational processes of individual attitudes and intentions, a collection of self-care activities resulting from an interaction between the patient and the providers |

| Khan et al. (2012) | Medicine | The degree to which a patient’s actions (such as taking medications, making adjustments to their lifestyles, having tests conducted, or following doctor appointments) align with the medical professional’s suggestions |

| Cramer et al. (2008) | Medicine | The extent to which a patient conforms with the provider’s instructions regarding routine therapy in terms of timing, dosage, and frequency, as well as the degree to which a patient behaves in line with the recommended intervals and doses of regimens. |

| Sweileh et al. (2004) | Nursing | The degree to which an individual’s behaviors coincide with medical advice |

| Chatterjee (2006) | Nursing | - The degree to which the individual’s actual drug administration history coincides with the recommended regimen - The degree to which an individual complies with medical or health recommendations, whether it comes to taking medication, adhering to diets, or making modifications to their lifestyles |

| Cushing and Metcalfe (2007) | Medicine | The degree to which an individual follows healthcare recommendation and receives treatments |

| Ibrahim et al. (2010) | Health Sciences | The degree to which a patient engages in the regimen of daily activities suggested by a medical expert as a way to manage their diabetes. These include the way the patient eats, exercises, takes medications, checks blood sugar, and takes care of their feet. |

| van der Wal et al. (2010) | Nursing | The degree to which a patient conforms with (agreed) advice from a medical professional, including taking medications, following a diet, or carrying out other lifestyle suggestions. |

| Vrijens et al. (2012) | Medicine | The degree to which a patient conforms with medical recommendations in terms of taking drugs, following a diet, or making other lifestyle modifications |

| Alikari and Zyga (2014) | Nursing | The patient is required to follow the therapist’s directions, illustrating the relationship between the two parties in which the patient is the one who receives guidance. |

| Rao et al. (2014) | Medicine | The degree to which an individual’s behaviors align with medical advice |

| Dutt (2017) | Health Sciences | The extent to which the person’s actual regimens match what a health practitioner prescribed |

| Lu et al. (2018) | Medicine | How patients follow the medical diagnoses and treatment regimens recommended by their physicians |

| Ali et al. (2019) | Medicine | The capacity of the individual to conform to antihypertensive treatments and related non-drug approaches |

| Shrestha et al. (2019) | Nursing | The actions taken by patients to preserve their health, such as following dietary guidance, engaging in regular exercise, taking prescribed medications, and paying attention to medical advice |

| Wu et al. (2021) | Medicine | The extent to which individuals follow their doctor’s advice and take the necessary steps to enhance their health |

Determination of Defining Attributes

The authors located the term that appears the most frequently among all the current meanings in this stage and classified potential words with comparable meanings into keyword clusters. The authors manually grouped keywords that had similar meanings using a table. The authors subsequently determined the names or attributes corresponding to each identified keyword cluster of patient compliance (Walker & Avant, 2019).

Self-care behavior

Self-care behavior involves taking medication, attending scheduled clinic appointments, undergoing medical tests (Chatterjee, 2006; Khan et al., 2012; Murphy & Coster, 1997), and executing lifestyle changes (Chatterjee, 2006; Khan et al., 2012; van der Wal et al., 2010; Vrijens et al., 2012). Moreover, self-care behavior can be described as appropriate actions to improve health in general (Wu et al., 2021). For example, in the diabetes context, self-care behavior includes daily activities for diabetes management through dietary habits, physical activity, medication use, blood sugar control, foot care, and the timing and coordination of such behaviors (Ibrahim et al., 2010).

Following health recommendations

Following health recommendations simply describes how patients stick to the prescribed medical diagnosis and treatment plans (Ali et al., 2019; Lu et al., 2018) and health behaviors (Shrestha et al., 2019) recommended by their physicians. Following is when the patients’ health behavior coincides with the healthcare provider’s recommendations (Chatterjee, 2006; Cushing & Metcalfe, 2007; Khan et al., 2012; Sweileh et al., 2004; van der Wal et al., 2010; Vrijens et al., 2012). It also means conformity to the advice on routine treatments in terms of the timing, dosage, and frequency, and the patients’ action that is in line with a dosage regimen’s specified interval and dose (Cramer et al., 2008). Furthermore, the following implies that the patient’s documented history of drug use is consistent with the recommended plan (Chatterjee, 2006) and that the patient’s actual regimens match the guidelines set forth by their healthcare practitioner (Dutt, 2017).

Willing collaboration with health professionals

Willing collaboration with health professionals refers to the interaction between the patient and medical professionals (Alikari & Zyga, 2014), in which the patients show willingness (Murphy & Coster, 1997) and agreement (van der Wal et al., 2010) with the recommendations through cognitive-motivational processes of attitude and intention of the patients (Kyngäs, 2000). Intentions are caused by collaborative influences of attitudes toward the behavior, which causally determine behaviors (Umaki et al., 2012). Patients participate in their treatments with the medical professional and define their behavior through their willingness to confront their long-term illness (Costa et al., 2021).

The attributes of patient compliance are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Attributes of patient compliance

| Keyword Clusters | Sources | Attributes |

|---|---|---|

|

(Chatterjee, 2006; Ibrahim et al., 2010; Khan et al., 2012; Murphy & Coster, 1997; Shrestha et al., 2019; van der Wal et al., 2010; Vrijens et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2021) | Self-care behavior |

|

(Chatterjee, 2006; Cramer et al., 2008; Cushing & Metcalfe, 2007; Dutt, 2017; Ibrahim et al., 2010; Khan et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2018; Murphy & Coster, 1997; Shrestha et al., 2019; Sweileh et al., 2004; van der Wal et al., 2010; Vrijens et al., 2012) | Following health recommendations |

|

(Alikari & Zyga, 2014; Kyngäs, 2000; Murphy & Coster, 1997; van der Wal et al., 2010) | Willing collaboration with health professionals |

Identification of a Model Case

“M, aged 46 years, is diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. Her healthcare provider has prescribed medications and a plan for a recommended diet to control diabetes and certain lifestyle practices (more physical activity, self-monitoring of blood sugar) that she needs to practice. The healthcare provider clearly explains the association between each of the recommended behaviors and diabetes control. Thus, M takes medications, lowers carbohydrate intakes, goes for a brisk walk for 30 minutes after meals, and uses a glucometer to monitor her blood sugar regularly (Attribute 1: Self-care behaviors) as her healthcare provider recommended (Attribute 2: Following health recommendations). Moreover, she agrees that these behaviors are beneficial for controlling diabetes (Attribute 3: Willing collaboration with health professionals), leading to lower blood sugar levels and better health status.”

A model case is a complete example of the investigated concept that contains all defining attributes (Walker & Avant, 2019). The model case presented above consists of all defining attributes of patient compliance found in this analysis (self-care behaviors, following health recommendations, and willing collaboration with health professionals). Attribute 1 is illustrated through M’s practice of a set of self-care behaviors for diabetes care by taking medications, taking on a proper diet to control diabetes, practicing more physical exercise, and monitoring her blood sugar regularly, as recommended by her healthcare provider, which reflects Attribute 2. Additionally, Attribute 3 is seen through M’s willing collaboration with what her healthcare provider recommended, as she agrees with the benefits of these recommendations for her diabetes control and healthier status.

Identification of Borderline and Contrary Cases

Borderline Case

“P has hypertension and is recommended by her healthcare provider to take hypertensive medications, take on a DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet, and reduce alcohol consumption and stress. Therefore, she takes her hypertensive medications, eats more vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, avoids drinking alcohol when having dinner or when going out with friends, and practices meditation to reduce stress (Attribute 1: Self-care behaviors), as suggested by her healthcare provider (Attribute 2: Following health recommendations). Nevertheless, deep down, she doubts the health benefits of some of these recommendations because her healthcare provider did not clearly communicate how the recommended behaviors would lead to blood pressure control.”

A borderline case presents the majority, but not all, of the concept’s defining attributes (Walker & Avant, 2019). The borderline case above presents Attribute 1: Self-care behaviors and Attribute 2: Following health recommendations. However, Attribute 3: Willing collaboration with health professionals is not identified because the patient has doubtful feelings about the health recommendations caused by the lack of explanation from the healthcare provider.

Contrary case

“V is diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. His healthcare provider gives him prescriptions for diabetic medications and recommends that he take an appropriate diet for diabetes. V is also suggested to practice more physical exercise regularly and monitor his blood sugar at home. However, V does not perform any of these behaviors. He continues to eat whatever he wants and has a sedentary lifestyle as usual (No self-care behavior), which was the opposite of the professional advice (No Following health recommendations). He argues that these recommendations are troublesome in daily life and do not seem to help reduce his blood sugar level (No Willing collaboration with health professionals).”

A contrary case is directly opposite from a model case as it includes none of the concept’s attributes (Walker & Avant, 2019). The contrary case presented above shows the opposite of the attributes of patient compliance. The patient does not perform any self-care behaviors. He does not follow health recommendations and lacks willing collaboration with health professionals.

Identification of Antecedents and Consequences

Antecedents

According to Walker and Avant (2019), antecedents are events that take place before the concept occurs. The antecedents of patient compliance extracted from the literature review were categorized into three groups: characteristics of therapeutic regimens, communication of health advice, and patients’ attitudes toward professional recommendations.

Characteristics of therapeutic regimens varied, including administration routes, regimen complexity, treatment duration, and side effects. Patients are more likely to comply with treatment when given medications that can be taken easily (such as oral medications) (Jin et al., 2008; Memon et al., 2017). Complex treatments are thought to jeopardize patient compliance. As the number of daily doses rose, the patient compliance rate declined. The prescribed regimens may not be compatible with the patient’s ability to comply, which results in non-compliance (Naghavi et al., 2019). A lengthier treatment time may compromise patient compliance (Abdallah et al., 2023). Moreover, side effects of medications, particularly physical discomfort, reduced patient compliance (Aremu et al., 2022; Basmakci et al., 2022; Naghavi et al., 2019; Saiz et al., 2015).

Communication of health advice affects patient compliance. Communicating effectively is essential to ensure that patients understand their illnesses and treatments (Jin et al., 2008). Whether a patient will follow a physician’s suggestions depends on their communication. Explicit explanations of treatment and disease increase the possibility that patients will follow medical advice (Krot & Sousa, 2017). Furthermore, doctors’ respectful communication, where the doctors allow the patients to speak and listen to patients’ opinions, motivated the patients to follow doctors’ instructions accurately (Naghavi et al., 2019). In contrast, inadequate doctor-patient communication is the primary cause of non-compliance with treatments (Basmakci et al., 2022), as it is a barrier to patient’s understanding of the medications, thereby leading them to miss doses (Naghavi et al., 2019).

Patients’ attitudes toward professional recommendations may influence patient compliance. Patients who perceive the health recommendations as practical and effective tend to be more compliant (Saiz et al., 2015). Furthermore, a doctor’s qualifications and characteristics in terms of medical performance and degree of accuracy of recommendations are crucial considerations. Patients who doubt their doctors’ performance, knowledge, and diagnosis are more likely to be non-compliant (Krot & Sousa, 2017; Naghavi et al., 2019).

Consequences

Consequences are events resulting from the concept (Walker & Avant, 2019). From the literature review, patient compliance with the pharmacological treatment regimen and non-pharmacological treatments leads to improved clinical outcomes (Aremu et al., 2022) in chronic illnesses, such as lower HbA1C among diabetes patients (Muliyil et al., 2017) and lower blood pressure level among hypertensive patients (Ekinci et al., 2017). With improved clinical outcomes and fewer complications, patients also develop general life satisfaction and perceptions of a better quality of life (Garabeli et al., 2016). In addition, patient compliance results in lifestyle or behavior modification, such as regular physical exercise, greater intake of vegetables and fruits, smoking cessation, and moderation of alcohol consumption (Ogbemudia & Odiase, 2021) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Antecedents, attributes, and consequences of patient compliance

Identification of Empirical Referent

Empirical referents are not instruments for measuring concepts but rather meant to quantify attributes (Walker & Avant, 2019). Self-care behavior attribute is measured in several instruments, including the Hypertension Self-Care Activity Level Effects (Warren Findlow et al., 2013), the Therapeutic Self-Care (Sidani & Doran, 2014), Self-Care of Chronic Illness Inventory (Riegel et al., 2018), and Self-Care Inventory (SCI)–Patient Version (Luciani et al., 2022). The attribute of following health recommendations is measured in the Medication Compliance Questionnaire (MCQ) scale (Basmakci et al., 2022), the Compliance Evaluation Test (Ali et al., 2019), and the Kepatuhan Antibiotik Oral-20 (KAO-20) (Zulfa & Handayani, 2020), covering whether the patients take medications as prescribed. Moreover, following health recommendations is assessed in Prigge et al.’s compliance scale (Prigge et al., 2015), which reflects following the prescribed treatment regularly and continuously. The willing collaboration attribute is assessed in the Alliance Negotiation Scale (Doran et al., 2012) and the Consumer Quality Index (CQ-index) Continuum of Care (Berendsen et al., 2009).

Discussion

Patient compliance is not a new concept. However, an analysis is worthwhile to re-examine the understanding of this concept to ensure proper assessments and interventions. Based on the findings on its antecedents, attributes, and consequences, patient compliance can be defined as the practice of self-care behaviors by following health recommendations that reflect willing collaboration with health professionals, influenced by the characteristics of therapeutic regimen, communication of health advice, and patients’ attitude toward professional recommendations, which lead to improved clinical outcomes and quality of life, and lifestyle or behavior modification. Therefore, more effort is needed to improve health professionals’ communication (Aremu et al., 2022) to effectively educate patients about the possible side effects of certain medications and give proper health advice in order to promote positive attitudes among patients. Patients’ inadequate health knowledge, fears of adverse medication side effects, and unfavorable attitudes toward health recommendations were essential barriers to compliance (Dwairej et al., 2020).

Interestingly, the findings showed that one of the attributes of patient compliance was a willing collaboration with health professionals where the patients agree with health recommendations. In literature, it can be argued that willing collaboration is more linked to adherence (Rae, 2021). However, it was found that compliant patients did not always follow health recommendations passively as they were told. Rather, they also agreed on the significance of following healthcare plans (Jansiraninatarajan, 2013). Patients had an understanding of their illness, the food that was good for preventing complications, and the consequences of non-compliance (Berek & Afiyanti, 2020). Further exploration is thus warranted to provide a clearer understanding of this concept.

Conclusion

The focus of this concept analysis was on the concept’s importance, application, and use in nursing. The findings offer the antecedents, attributes, and consequences of the patient compliance concept. The new definition of compliance given in this concept analysis provides clarity and directions for future inquiry and nursing practice. The findings are beneficial for nurses in constructing a tool to predict compliance behavior for a given patient and condition, including a relationship model that focuses on the role of healthcare providers and patients. Furthermore, this research helps raise nurses’ awareness of the need for effective patient communication to increase patient compliance.

Acknowledgment

This article was developed from a class assignment for a PhD in the course of Theory and Development in Nursing. Thus, our gratitude goes to the professors who gave us constant guidance and support. Special thanks to Dr. Kay Coalson Avant, a special teacher in the subject. This paper would have never been accomplished without their assistance and dedicated involvement in every step of the process.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Funding

This paper did not receive any specific grant from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Authors’ Contributions

ST conceptualized, designed, and analyzed. WU contributed to designing, analyzing, drafting, and reviewing the manuscript. LOW drafted the manuscript and reviewed it. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published. All authors contributed equally to this study, and they read and approved the final manuscript and were accountable and entirely responsible for its content. The author meets four authorship criteria based on ICMJE Recommendations.

Authors’ Biographies

Saowaluk Thummak, RN, MSN is a Nursing Instructor at the Kuakarun Faculty of Nursing, Navamindradhiraj University, Thailand. Currently, she is studying in the Doctor of Philosophy Program in Nursing Science at the Faculty of Nursing, Chiang Mai University. Her research interest focuses on critical and emergent nursing and disaster nursing.

Wassana Uppor, RN, PhD is a Nursing Instructor at the Boromarajonani College of Nursing, Suphanburi, Faculty of Nursing, Praboromarajchanok Institute, Thailand. Her research interests focus on nursing education, nursing administration, simulation-based learning, and reflective thinking.

Wing Commander La-Ongdao Wannarit, RN, PhD is a Nursing Instructor at the Royal Thai Air Force Nursing College, Directorate of Medical Services, Royal Thai Air Force, Bangkok, Thailand. Her research interest focuses on maternal and newborn nursing and midwifery, health promotion, and nursing education.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Ethical Consideration

Not applicable.

References

- Abdallah, D. M., Taha, N. M., Mohamed, E. H., & Saleh, M. D. (2023). Factors affecting compliance of therapeutic regimen among patients with multiple sclerosis. Zagazig Nursing Journal, 19(2), 1-12. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. A., Abderraman, G. M., Tondi, Z. M. M., & Mahamat, H. A. (2019). Compliance of hypertensive patients with antihypertensive drug therapy at the Renaissance Hospital of N’Djamena, Chad. Annals of Clinical Hypertension, 3(1), 47-51. 10.29328/journal.ach.1001019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alikari, V., & Zyga, S. (2014). Conceptual analysis of patient compliance in treatment. Health Science Journal, 8(2), 179-186. [Google Scholar]

- Aremu, T. O., Oluwole, O. E., Adeyinka, K. O., & Schommer, J. C. (2022). Medication adherence and compliance: Recipe for improving patient outcomes. Pharmacy, 10(5), 106. 10.3390/pharmacy10050106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basmakci, A., Kutlu, O., Kalyon, S., Sertdemir, T., & Mine, A. (2022). Diabetic patients’ compliance with treatment during COVID-19 pandemic period. Journal of Istanbul Faculty of Medicine, 85(4), 485-493. 10.26650/IUITFD.1050290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berek, P. A. L., & Afiyanti, Y. (2020). Compliance of hypertension patients in doing self-care: A grounded theory study. JurnalSahabat Keperawatan, 2(1), 21-35. [Google Scholar]

- Berendsen, A. J., Groenier, K. H., de Jong, G. M., Meyboom-de Jong, B., van der Veen, W. J., Dekker, J., de Waal, M. W. M., & Schuling, J. (2009). Assessment of patient's experiences across the interface between primary and secondary care: Consumer Quality Index Continuum of care. Patient Education and Counseling, 77(1), 123-127. 10.1016/j.pec.2009.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunting, J., & de Klerk, M. (2022). Strategies to improve compliance with clinical nursing documentation guidelines in the acute hospital setting: A systematic review and analysis. SAGE Open Nursing, 8, 23779608221075165. 10.1177/23779608221075165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, J. S. (2006). From compliance to concordance in diabetes. Journal of Medical Ethics, 32(9), 507-510. 10.1136/jme.2005.012138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheraghi, M. A., Pashaeypoor, S., Dehkordi, L. M., & Khoshkesht, S. (2021). Creativity in nursing care: A concept analysis. Florence Nightingale Journal of Nursing, 29(3), 389–396. https://doi.org/10.5152%2FFNJN.2021.21027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, K. F. d. L., Vieira, A. N., Bezerra, S. T. F., Silva, L. d. F. d., Freitas, M. C. d., & Guedes, M. V. C. (2021). Nursing theory for patients’ compliance with the treatments of arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus. Texto & Contexto-Enfermagem, 30. 10.1590/1980-265X-TCE-2020-0344 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, J. A., Roy, A., Burrell, A., Fairchild, C. J., Fuldeore, M. J., Ollendorf, D. A., & Wong, P. K. (2008). Medication compliance and persistence: Terminology and definitions. Value in Health, 11(1), 44-47. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushing, A., & Metcalfe, R. (2007). Optimizing medicines management: From compliance to concordance. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 3(6), 1047-1058. 10.2147/tcrm.s12160480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai, R., Thakkar, S., Fong, H. K., Varma, Y., Khan, M. Z. A., Itare, V. B., Raina, J. S., Savani, S., Damarlapally, N., & Doshi, R. P. (2019). Rising trends in medication non-compliance and associated worsening cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes among hospitalized adults across the United States. Cureus, 11(8), e5389. 10.7759/cureus.5389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doran, J. M., Safran, J. D., Waizmann, V., Bolger, K., & Muran, J. C. (2012). The Alliance Negotiation Scale: Psychometric construction and preliminary reliability and validity analysis. Psychotherapy Research, 22(6), 710-719. 10.1080/10503307.2012.709326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutt, S. (2017). Importance of patient adherence and compliance in the present day. Journal of Bacteriology and Mycology Open Access, 4(5), 150-152. 10.15406/jbmoa.2017.04.00106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dwairej, L. A., Ahmad, M. M., & Alnaimat, I. A. (2020). The process of compliance with self-care among patients with hypertension: A grounded theory study. Open Journal of Nursing, 10(5), 534-550. 10.4236/ojn.2020.105037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehwarieme, T. A., Ogbogu, C. J., Chisom, M., & Obiekwu Adaobi, L. (2018). Compliance to treatment regimen among diabetic patients attending outpatient department of selected hospitals in Benin City, Edo State. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology, 10(4), 97-107. 10.5897/JPHE2018.1002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ekinci, F., Tuncel, B., Coşkun, D. M., Akman, M., & Uzuner, A. (2017). Effects on blood pressure control and compliance for medical treatment in hypertensive patients by sending daily sms as a reminder. Konuralp Medical Journal, 9(2), 136-141. 10.18521/ktd.288633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garabeli, A. A., Daher, J. B., Wiens, A., Lenzi, L., & Pontarolo, R. (2016). Quality of life perception of type 1 diabetic patients treated with insulin analogs and receiving medication review with follow-up in a public health care service from Ponta Grossa-PR, Brazil. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 52, 669-677. 10.1590/S1984-82502016000400010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim, N. K. R., Attia, S. G., Sallam, S. A., Fetohy, E. M., & El-Sewi, F. (2010). Physicians’ therapeutic practice and compliance of diabetic patients attending rural primary health care units in Alexandria. Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 17(3), 121-128. https://doi.org/10.4103%2F1319-1683.74325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansiraninatarajan . (2013). Diabetic compliance: A qualitative study from the patient’s perspective in developing countries. IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science, 1(4), 29–38. 10.9790/1959-0142938 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J., Sklar, G. E., Min Sen Oh, V., & Chuen Li, S. (2008). Factors affecting therapeutic compliance: A review from the patient’s perspective. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 4(1), 269-286. 10.2147/tcrm.s1458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, A. R., Lateef, Z. N. A.-A., Al Aithan, M. A., Bu-Khamseen, M. A., Al Ibrahim, I., & Khan, S. A. (2012). Factors contributing to non-compliance among diabetics attending primary health centers in the Al Hasa district of Saudi Arabia. Journal of Family and Community Medicine, 19(1), 26-32. https://doi.org/10.4103%2F2230-8229.94008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krot, K., & Sousa, J. P. (2017). Factors impacting on patient compliance with medical advice: Empirical study. Engineering Management in Production and Services, 9(2), 73-81. 10.1515/emj-2017-0016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kyngäs, H. (2000). Compliance of adolescents with diabetes. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 15(4), 260-267. 10.1053/jpdn.2000.6169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X., Zhang, R., Wu, W., Shang, X., & Liu, M. (2018). Relationship between internet health information and patient compliance based on trust: Empirical study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(8), e253. 10.2196/jmir.9364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luciani, M., De Maria, M., Page, S. D., Barbaranelli, C., Ausili, D., & Riegel, B. (2022). Measuring self-care in the general adult population: development and psychometric testing of the Self-Care Inventory. BMC Public Health, 22, 598. 10.1186/s12889-022-12913-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, C. J. H., & Bull, P. (2008). Obedience and conformity in clinical practice. British Journal of Midwifery, 16(8), 504-509. 10.12968/bjom.2008.16.8.30783 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Memon, K. N., Shaikh, N. Z., Soomro, R. A., Shaikh, S. R., & Khwaja, A. (2017). Non-compliance to doctors’ advices among patients suffering from various diseases: Patients’ perspectives: A neglected issue. Journal of Medicine, 18(1), 10-14. [Google Scholar]

- Mir, T. H. (2023). Adherence versus compliance. HCA Healthcare Journal of Medicine, 4(2), 22. 10.36518/2689-0216.1513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muliyil, D. E., Vellaiputhiyavan, K., Alex, R., & Mohan, V. R. (2017). Compliance to treatment among type 2 diabetics receiving care at peripheral mobile clinics in a rural block of Vellore District, Southern India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 6(2), 330-335. https://doi.org/10.4103%2F2249-4863.219991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J., & Coster, G. (1997). Issues in patient compliance. Drugs, 54, 797-800. 10.2165/00003495-199754060-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi, S., Mehrolhassani, M. H., Nakhaee, N., & Yazdi-Feyzabadi, V. (2019). Effective factors in non-compliance with therapeutic orders of specialists in outpatient clinics in Iran: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 19, 413. 10.1186/s12913-019-4229-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogbemudia, E. J., & Odiase, F. E. (2021). Poor compliance with lifestyle modifications and related factors in hypertension. Highland Medical Research Journal, 21(1), 57-62. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford Learner's Dictionaries . (2023a). Patient. In Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/patient_1?q=patient

- Oxford Learner's Dictionaries . (2023b). Compliance. In Oxford Learner's Dictionaries. https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/compliance?q=compliance

- Prigge, J.-K., Dietz, B., Homburg, C., Hoyer, W. D., & Burton, J. L. (2015). Patient empowerment: A cross-disease exploration of antecedents and consequences. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 32(4), 375-386. 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2015.05.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rae, B. (2021). Obedience to collaboration: Compliance, adherence and concordance. Journal of Prescribing Practice, 3(6), 235-240. 10.12968/jprp.2021.3.6.235 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C. R., Kamath, V. G., Shetty, A., & Kamath, A. (2014). Treatment compliance among patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus in a coastal population of Southern India. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 5(8), 992-998. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, B., Barbaranelli, C., Sethares, K. A., Daus, M., Moser, D. K., Miller, J. L., Haedtke, C. A., Feinberg, J. L., Lee, S., & Stromberg, A. (2018). Development and initial testing of the self‐care of chronic illness inventory. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74(10), 2465-2476. 10.1111/jan.13775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saiz, A., Mora, S., & Blanco, J. (2015). Treatment compliance with first line disease-modifying therapies in patients with multiple sclerosis. Compliance study. Neurología (English Edition), 30(4), 214-222. 10.1016/j.nrleng.2015.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen, H. T. N., Linh, T. T. T., & Trang, D. T. K. (2020). Factors related to treatment compliance among patients with heart failure. Ramathibodi Medical Journal, 43(2), 30-40. 10.33165/rmj.2020.43.2.239889 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, K. D., Takma, K. C., & Ghimire, R. (2019). Predictors of treatment regimen compliance and glycemic control among diabetic patients attending in a tertiary level hospital. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council, 17(3), 368-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sidani, S., & Doran, D. I. (2014). Development and validation of a self-care ability measure. Canadian Journal of Nursing Research 11-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweileh, W., Aker, O., & Hamooz, S. (2004). Rate of compliance among patients with diabetes mellitus and hypertension. An-Najah University Journal for Research-A (Natural Sciences), 19(1), 1-11. 10.35552/anujr.a.19.1.612 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tun, H. (2021). Importance of medication compliance and lifestyle modification in heart failure readmission: Single centre cohort study. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 28(Supplement_1), zwab061-030. 10.1093/eurjpc/zwab061.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaki, T. M., Umaki, M. R., & Cobb, C. M. (2012). The psychology of patient compliance: A focused review of the literature. Journal of Periodontology, 83(4), 395-400. 10.1902/jop.2011.110344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Wal, M. H. L., Jaarsma, T., Moser, D. K., van Gilst, W. H., & van Veldhuisen, D. J. (2010). Qualitative examination of compliance in heart failure patients in The Netherlands. Heart & Lung, 39(2), 121-130. 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijens, B., De Geest, S., Hughes, D. A., Przemyslaw, K., Demonceau, J., Ruppar, T., Dobbels, F., Fargher, E., Morrison, V., & Lewek, P. (2012). A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 73(5), 691-705. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, L. O., & Avant, K. C. (2019). Strategies for theory construction in nursing (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Warren Findlow, J., Basalik, D. W., Dulin, M., Tapp, H., & Kuhn, L. (2013). Preliminary validation of the hypertension self‐care activity level effects (H‐SCALE) and clinical blood pressure among patients with hypertension. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension, 15(9), 637-643. 10.1111/jch.12157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D., Lowry, P. B., Zhang, D., & Parks, R. F. (2021). Patients’ compliance behavior in a personalized mobile patient education system (PMPES) setting: Rational, social, or personal choices? International Journal of Medical Informatics, 145, 104295. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zulfa, I. M., & Handayani, W. (2020). Patient’s compliance with oral antibiotics treatments at community health centers in Surabaya: A 20-KAO Questionnaire Development. Borneo Journal of Pharmacy, 3(4), 262-269. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.