Key Points

Question

Does adding sigh breaths to the usual care of trauma patients receiving mechanical ventilation increase ventilator-free days?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial among 524 trauma patients with risk factors for developing acute respiratory distress syndrome, the addition of sigh breaths did not significantly increase ventilator-free days compared with usual care alone (median ventilator-free days, 18.4 vs 16.1, respectively). Although not adjusted for multiple testing, sigh breaths were associated with improvement in secondary outcomes including all-cause mortality. There was no evidence of harm.

Meaning

Sigh breaths added to usual care did not significantly increase ventilator-free days among trauma patients who received mechanical ventilation but may improve clinical outcomes.

Abstract

Importance

Among patients receiving mechanical ventilation, tidal volumes with each breath are often constant or similar. This may lead to ventilator-induced lung injury by altering or depleting surfactant. The role of sigh breaths in reducing ventilator-induced lung injury among trauma patients at risk of poor outcomes is unknown.

Objective

To determine whether adding sigh breaths improves clinical outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A pragmatic, randomized trial of sigh breaths plus usual care conducted from 2016 to 2022 with 28-day follow-up in 15 academic trauma centers in the US. Inclusion criteria were age older than 18 years, mechanical ventilation because of trauma for less than 24 hours, 1 or more of 5 risk factors for developing acute respiratory distress syndrome, expected duration of ventilation longer than 24 hours, and predicted survival longer than 48 hours.

Interventions

Sigh volumes producing plateau pressures of 35 cm H2O (or 40 cm H2O for inpatients with body mass indexes >35) delivered once every 6 minutes. Usual care was defined as the patient’s physician(s) treating the patient as they wished.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary outcome was ventilator-free days. Prespecified secondary outcomes included all-cause 28-day mortality.

Results

Of 5753 patients screened, 524 were enrolled (mean [SD] age, 43.9 [19.2] years; 394 [75.2%] were male). The median ventilator-free days was 18.4 (IQR, 7.0-25.2) in patients randomized to sighs and 16.1 (IQR, 1.1-24.4) in those receiving usual care alone (P = .08). The unadjusted mean difference in ventilator-free days between groups was 1.9 days (95% CI, 0.1 to 3.6) and the prespecified adjusted mean difference was 1.4 days (95% CI, −0.2 to 3.0). For the prespecified secondary outcome, patients randomized to sighs had 28-day mortality of 11.6% (30/259) vs 17.6% (46/261) in those receiving usual care (P = .05). No differences were observed in nonfatal adverse events comparing patients with sighs (80/259 [30.9%]) vs those without (80/261 [30.7%]).

Conclusions and Relevance

In a pragmatic, randomized trial among trauma patients receiving mechanical ventilation with risk factors for developing acute respiratory distress syndrome, the addition of sigh breaths did not significantly increase ventilator-free days. Prespecified secondary outcome data suggest that sighs are well-tolerated and may improve clinical outcomes.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02582957

This randomized clinical trial compares the efficacy of sighs in addition to usual care vs usual care alone in improving clinical outcomes among trauma patients receiving mechanical ventilation and are at risk for developing acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Introduction

Most patients receiving pressure- or volume-controlled invasive mechanical ventilation receive a constant, or nearly constant, tidal volume (VT) with each breath.

Many studies, however, report that constant VT ventilation (CVTV), with either small or large VTs, delivered for even short periods, alters surfactant, increases surface tension, causes atelectasis, generates inflammatory cytokines, and produces ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI).1 Atelectasis is a critical factor in this pathophysiology because cyclical opening and closing of atelectatic airspaces (termed atelectrauma) and overdistension of patent alveoli adjacent to the atelectatic regions (termed volutrauma) occur, both of which are currently thought to cause VILI and result in systemic inflammation (termed biotrauma2,3).

Surfactant is normally inactivated and/or depleted continuously over time. Accordingly, it must be continuously secreted to maintain low surface tension and prevent atelectasis. The strongest stimulus for surfactant secretion is the mechanical stress resulting from stretching type II pneumocytes, as would occur with large VTs.4,5,6,7,8,9,10 Nearly 60 years ago, Pattle11 noted that one of the functions of a yawn or deep breath was to recruit more surfactant to the lining film and that if deep breaths were prevented, the lining film would collapse leading to alveolar collapse. He also suggested that, if artificial respiration were being used, the collapse could be prevented by giving occasional maximal inflations.

Short-term administration of sighs improves compliance and gas exchange, decreases ventilation heterogeneity and regional lung strain, reverses and prevents atelectasis, and reduces inflammatory cytokine production.12,13,14,15,16,17,18 While there is concern that large breaths may cause VILI by volutrauma,2,3 a recent study suggested that sighs seem to be safe when administered to patients with lung injury.19 The Pragmatic Trial of Sigh Ventilation in Patients with Trauma (SiVent) study was conducted to test whether incorporating sighs into the routine management of trauma patients requiring mechanical ventilation improved outcomes compared with usual care.

Methods

Study Design

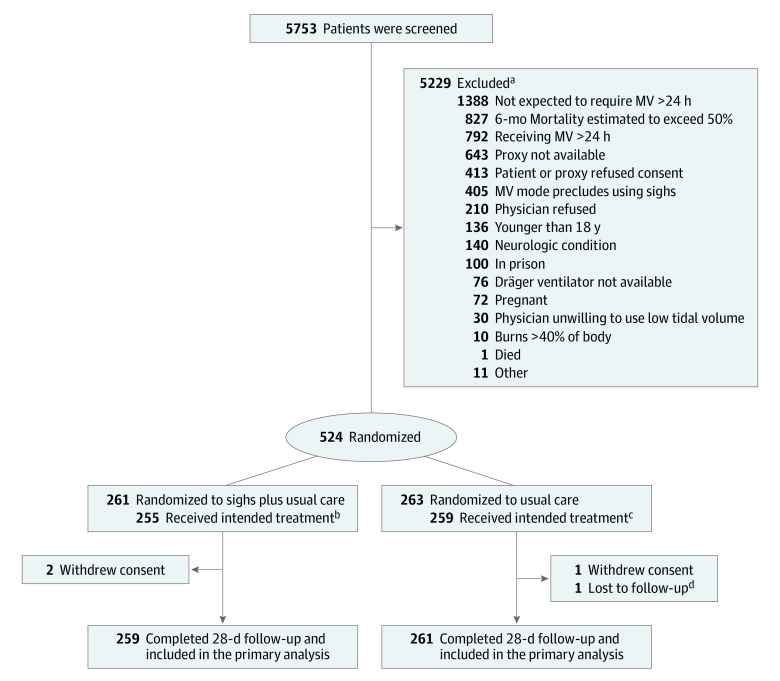

We used a pragmatic, parallel-group design with participants randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to the control or intervention groups. Randomization used an interactive website operated by the data coordinating center with block randomization (randomly chosen block sizes of 2, 4, or 6) stratified by center (Figure 1). The control group received usual care defined as the patient’s physician(s) treating the patient as they wished. The intervention group received usual care with sighs added to whatever ventilatory protocol was being used (eg, ventilatory mode, respiratory rate, VT, level of positive end-expiratory pressure [PEEP], inspiratory flow rate).

Figure 1. Screening, Randomization, and Follow-Up of Participants in the SiVent Trial.

MV indicates mechanical ventilation; SiVent, Sigh Ventilation to Increase Ventilator-Free Days in Victims of Trauma at Risk for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome.

aIndividuals may have met more than 1 exclusion criteria.

bSix individuals were receiving mechanical ventilation.

cFour individuals temporarily received sighs.

dVital status at day 28 unknown.

Patients were followed up daily up to 28 days until they were extubated and left the intensive care unit (ICU) or died. If a patient was reintubated, daily assessments were restarted. Vital status was assessed at day 28.

The protocol and changes to the protocol that occurred after the study began are available in Supplement 1.

Participants

Patients were recruited in 15 trauma centers in the US (Table 1). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or from their legally authorized representative. Inclusion criteria were age 18 years or older; admission because of trauma; receipt of invasive mechanical ventilation but for less than 24 hours; expected ventilation at more than 24 hours; expected survival at more than 48 hours; and having 1 or more of the following risk factors for developing acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): (1) traumatic brain injury; (2) more than 1 long bone fracture; (3) shock (defined as a systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg when first evaluated); (4) lung contusion (as indicated in the medical record); and (5) receipt of more than 6 units of all blood products in the first 24 hours of care. Race and ethnicity information was self-reported or obtained from the medical record by the research coordinators for patients who were intubated and unable to communicate and was collected to facilitate generalizing the patients studied to the US population.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Enrolled Patients.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sighs + usual care | Usual care alone | |

| Total No. of participants | 261 | 263 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 43.7 (19.1) | 44.2 (19.2) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 197 (75.5) | 197 (74.9) |

| Female | 64 (24.5) | 66 (25.1) |

| Race and ethnicitya | 260 | 262 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2 (0.8) | 0 |

| Asian | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.5) |

| Black or African American | 55 (21.2) | 52 (19.8) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 43 (16.5) | 42 (16.0) |

| White | 202 (77.7) | 203 (77.5) |

| Multiple racial and ethnic categories | 0 | 3 (1.1) |

| Smoking status, No. | 199 | 183 |

| Current/past | 134 (67.3) | 103 (56.3) |

| Never | 65 (32.7) | 80 (43.7) |

| Entry criteria | ||

| Traumatic brain injury | 159 (60.9) | 165 (62.7) |

| >1 Long bone fractures | 44 (16.9) | 47 (17.9) |

| In shock on arrival in EDb | 81 (31.0) | 96 (36.5) |

| Lung contusion | 107 (41.0) | 111 (42.2) |

| >6 U of blood products | 94 (36.0) | 89 (33.8) |

| Arterial blood gases on enrollment | 234 | 243 |

| pH, mean (SD) | 7.36 (0.08) | 7.37 (0.08) |

| Paco2, mean (SD), mm Hg | 39.1 (7.4) | 38.6 (7.8) |

| Pao2, mean (SD), mm Hg | 157.4 (84.2) | 152.5 (79.9) |

| Fio2, mean (SD), mm Hg [No.] | 48.1 (19.0) [230] | 47.1 (17.2) [228] |

| Pao2/Fio2 ratio, mean (SD) [No.] | 348.6 (171.9) [230] | 349.8 (214.0) [228] |

| Pao2/Fio2 ratio categorical | ||

| >300 (Best) | 130 (56.5) | 128 (56.1) |

| >200-300 | 57 (24.8) | 55 (24.1) |

| >100-200 | 35 (15.2) | 37 (16.2) |

| ≤100 (Worst) | 8 (3.5) | 8 (3.5) |

| PEEP, mean (SD), cm H2O [No.] | 6.8 (2.5) [222] | 7.1 (3.6) [227] |

| Hours with ventilator prior to randomization, mean (SD) | 17.1 (5.8) | 17.0 (5.9) |

| Ventilator mode, No. | 260 | 263 |

| Assisted mechanical ventilation | 98 (37.7) | 106 (40.3) |

| Controlled mechanical ventilation | 69 (26.5) | 66 (25.1) |

| Pressure control ventilation | 45 (17.3) | 45 (17.1) |

| Synchronized intermittent mandatory ventilation | 39 (15.0) | 40 (15.2) |

| Other | 9 (3.4) | 6 (2.2) |

| Inspiratory (set) tidal volume, mean (SD), mL [No.] | 502.9 (97.0) [258] | 501.2 (92.3) [261] |

| Set tidal volume/PBW, mean (SD), mL [No.] | 7.4 (1.4) [258] | 7.3 (1.4) [261] |

| Injury Severity Score, mean (SD) [No.]c | 28.8 (12.9) [256] | 29.9 (11.7) [259] |

| RASS scale, mean (SD) [No.]d | −2.0 (2.1) [256] | −2.0 (2.3) [261] |

| BMI [No.] | 261 | 263 |

| <30 | 161 (61.7) | 169 (64.3) |

| ≥30 | 100 (38.3) | 94 (35.7) |

| Infiltrates on initial chest x-ray or CT, No. | 258 | 261 |

| None | 181 (70.2) | 178 (68.2) |

| Localized | 22 (8.5) | 21 (8.0) |

| Generalized (bilateral) | 37 (14.3) | 49 (18.8) |

| Diffuse | 18 (7.0) | 13 (5.0) |

| Medications | 260 | 263 |

| For sedatione | 249 (95.8) | 252 (95.8) |

| For hypotensionf | 98 (37.7) | 90 (34.2) |

| For paralysis | 31 (11.9) | 24 (9.1) |

| To increase cardiac outputg | 3 (1.2) | 3 (1.1) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CT, computed tomography; ED, emergency department; Fio2, fraction of inspired oxygen; PBW, predicted body weight; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; RASS, Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale.

Race and ethnic data were self-reported by participants within fixed categories based on National Institutes of Health Diversity Program.

Systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg.

Score range, 0 (no injury) to 75 (not survivable).

Score range, +4 (combative) to −5 (unarousable). Score information is available in eTable 1 in Supplement 2.

Benzodiazepines, propofol, dexmedetomidine, haloperidol, quetiapine, and phenobarbital.

Norepinephrine, vasopressin, epinephrine, and phenylephrine.

Isoproterenol, dopamine, and inotropic agents.

Exclusion criteria were (1) inability to obtain consent from the patient or their legally authorized representative; (2) unwillingness of the treating physician to use sigh ventilation; (3) age younger than 18 years; (4) undergoing invasive mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hours; (5) presence of malignancy or other irreversible disease or condition for which the 6-month mortality was estimated to exceed 50% (eg, chronic liver disease with a Child-Pugh score of 10-15, malignancy refractory to treatment); (6) moribund, not expected to survive 48 hours; (7) individuals who were pregnant (negative pregnancy test results required for individuals of child-bearing age); (8) those in prison; (9) neurologic condition that could impair spontaneous ventilation (eg, C5 or higher spinal cord injury); (10) lack of availability of Dräger Evita Infinity V500 ventilator; (11) burns on more than 40% of body surface area; (12) treating physicians being unwilling to use low VT ventilation strategy when ARDS was diagnosed; (13) treating physician’s decision to use airway pressure–release ventilation; and (14) patient not expected to require mechanical ventilation for more than 24 hours (eg, intubated for alcohol intoxication rather than pulmonary problem).

Intervention

Sigh volumes were defined as whatever VT produced a plateau pressure (Pplat) of 35 cm H2O because this Pplat produces an end-inspiratory lung volume approximating total lung capacity if respiratory system compliance is normal. In patients with a body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) greater than 35, or in those presumed to have an increase in abdominal pressure, a Pplat of 40 cm H2O was targeted because chest wall compliance would be reduced. The volume delivered above the set VT to produce Pplats of 35 or 40 cm H2O was manually determined. Sighs were delivered over 5 seconds once every 6 minutes based on the findings of Bendixen and colleagues20 but not during transport or when patients were in the operating room.

Outcomes

The primary end point was ventilator-free days (VFDs), defined as the number of days of unassisted breathing to day 28 without having to reinstitute invasive ventilation. Patients who died before day 28 were assigned 0 VFDs. Post hoc subgroup analyses were performed on VFDs for demographic differences, each of the ARDS risk factors described above, and for severity of injury dichotomized above and below the median score.

Prespecified, secondary end points were all-cause 28-day mortality; the number of ICU-free days to day 28; complications (as diagnosed by the patients’ treating physicians); and discharge status. All primary and secondary end points were prespecified.

Post hoc tertiary end points included total VFDs (TVFDs), defined as the number of 24-hour periods that were free from assisted ventilation to day 28 or death; time to successful extubation; use of sedatives; time to development of a Pao2 to fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2) ratio consistent with ARDS and ARDS subgroups as defined by the Berlin criteria;21 and/or development of bilateral or diffuse infiltrates on chest imaging as determined from radiology reports.

Sample Size

We initially estimated a need to enroll 916 patients based on assumptions used in the EDEN and FACTT studies22,23 (ie, the SD for VFDs would be 10.5 days and the difference in VFDs between patients randomized to sighs vs usual care would be 2.25 days; 90% power; and 2-sided significance of .05). Two interim analyses were conducted: after approximately one-third and two-thirds of the targeted enrollment had occurred, respectively (monitoring boundaries are described in the eMethods in Supplement 2). After the first interim analysis of blinded data and review of recruitment progress, the data and safety monitoring board recommended recalculating the sample size using a reduced power and revised SD for VFDs. Using an SD of 9.9 VFDs observed in the control group, 80% power, and a withdrawal rate of 1%, the data coordinating center estimated the need to enroll 544 patients.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis for the difference in VFDs and ICU-free days between the 2 groups was the Wilcoxon rank-sum statistic. Linear least-squares regression with robust standard errors was additionally used to compare VFDs, TVFDs, and ICU-free days between groups. Kaplan-Meier survival curves and Cox models were used to compare time of death, time to development of Pao2/Fio2 ratios consistent with ARDS or ARDS subgroups, and/or development of generalized or diffuse infiltrates. Time to successful extubation was analyzed using competing risk regression with death as the competing risk.24 Occurrence of adverse events and all-cause 28-day mortality were analyzed by logistic regression unless otherwise specified. All analyses were based on the intention-to-treat principle. No adjustments for multiplicity were performed so the secondary and subgroup analyses should be interpreted as exploratory. Adjusted models included age, sex, smoking history, traumatic brain injury, more than 1 long bone fracture, shock, lung contusion, receipt of more than 6 units of blood products in the first 24 hours of care, Injury Severity Score, Pao2/Fio2 ratio of 300 or less prior to randomization, and trial center (adjusted Cox models were stratified by trial center). The significance threshold was 2-sided P < .05. Analyses were performed using R software version 4.32.1 (R Core Team) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). Additional statistical considerations are provided in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

The institutional review board at each participating institution approved the study.

Results

Patients

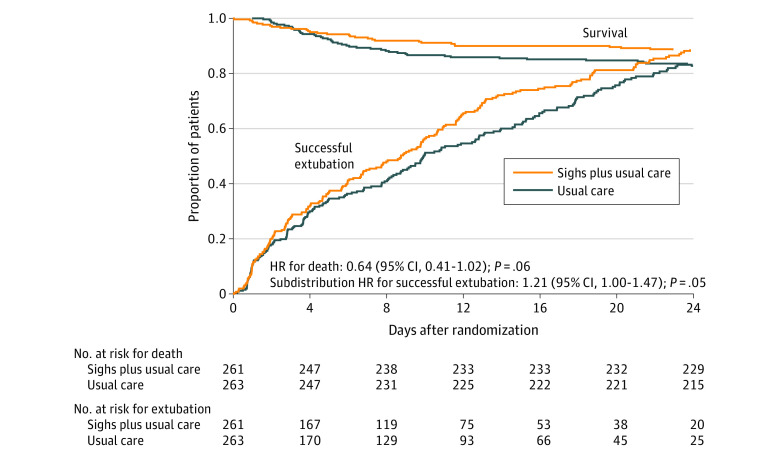

From April 2016 to September 2022, 524 patients were randomized (96% of the targeted enrollment), 261 to sigh breaths plus usual care and 263 to usual care alone (Figure 1, Table 1). The study was stopped prior to meeting targeted enrollment due to funding termination. A total of 520 participants (99%) completed follow-up and were included in the primary analysis. One patient was discharged prior to day 28 and their vital status as of day 28 was unknown. All randomized participants were included in the secondary time-to-event analysis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimates of the Probability of Survival and Survival Without the Need for Assisted Ventilation During the First 28 Days After Randomization.

Successful extubation was defined as the patient being able to breathe unassisted and maintaining unassisted breathing until the end of the study period. Among those who died, the median days from randomization to death was 5.5 (IQR, 2.1-9.8; n = 30) in the sighs plus usual care group and 5.3 (IQR, 3.5-9.1; n = 46) in the usual care alone group. Among those who were successfully extubated, the median days from randomization to extubation was 6.4 (IQR, 1.9-12.9; n = 209) in the sighs plus usual care group and 6.8 (IQR, 2.8-13.2; n = 197) in the usual care alone group.

Sigh Volumes

Of the 259 patients randomized to sighs with complete follow-up available, 223 were documented as receiving an initial (day 1) mean (SD) sigh volume of 939 (290) mL or 13.7 (4.1) mL/kg predicted body weight, representing 195% (76%) of their set VT (Table 2). Ventilator modes and tidal volumes during follow-up are reported in eTable 3 in Supplement 2.

Table 2. Primary and Secondary Outcomes.

| End point | Median (IQR) | Mean difference (sighs − usual care) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sighs + usual care (n = 259)a | Usual care alone (n = 261) | Unadjusted | Adjustedb | |||

| Estimated (95% CI) | P value | Estimated (95% CI) | P value | |||

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| Ventilator-free daysc | ||||||

| Overall | 18.4 (7.0 to 25.2) | 16.1 (1.1 to 24.4) | 1.9 (0.1 to 3.6) | .04 | 1.4 (−0.2 to 3.0) | .08 |

| Death excluded | 20.3 (14.2 to 25.8) | 19.5 (10.2 to 25.2) | 0.9 (−0.7 to 2.6) | .26 | 0.8 (−0.8 to 2.3) | .33 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| ICU-free days | ||||||

| Overall | 13.7 (2.0 to 20.6) | 11.9 (0.0 to 20.0) | 1.3 (−0.3 to 2.9) | .10 | 0.8 (−0.6 to 2.3) | .26 |

| Death excluded | 15.5 (7.8 to 21.2) | 14.0 (6.4 to 21.6) | 0.6 (−1.0 to 2.1) | .48 | 0.3 (−1.2 to 1.8) | .71 |

| Total ventilator-free daysd | ||||||

| Overall | 20.0 (9.0 to 25.0) | 17.0 (4.0 to 24.0) | 1.9 (0.2 to 3.6) | .03 | 1.4 (−0.1 to 2.9) | .07 |

| Death excluded | 21.0 (15.0 to 25.0) | 20.0 (11.5 to 25.0) | 1.0 (−0.6 to 2.5) | .22 | 0.8 (−0.7 to 2.2) | .30 |

Abbreviation: ICU, intensive care unit.

Patients randomized to sighs plus usual care received sighs for a median of 3 days (IQR, 1-7). Among those with a plateau pressure of ≤35 cm H2O (n = 183), the initial mean (SD) sigh volume was 994 (296) mL, 13.7 (4.2) mL/kg predicted body weight (PBW), or 192% (57%) of the set tidal volume. Among those with a plateau pressure >35 cm H2O (n = 37), the initial mean (SD) sigh volume was 905 (271) mL, 13.5 (3.6) mL/kg PBW, or 205% (138%) of the set tidal volume.

Models were adjusted for age, sex, smoking history, traumatic brain injury, >1 long bone fracture, shock, lung contusion, receipt of >6 units of blood products in the first 24 hours of care, Injury Severity Score, Pao2/Fio2 ratio ≤300 prior to randomization, and trial center. Missing values for Injury Severity Score and Pao2/Fio2 ratio were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations. Results were pooled across 50 imputations using the Rubin rules for computing the total variance. Results from the complete case analyses are provided in eTable 2 in Supplement 2.

Defined as number of days of unassisted breathing to day 28 without having to reinstitute invasive ventilation. Patients who died before day 28 were assigned 0 ventilator-free days.

Defined as the number of 24-hour periods that were free from assisted ventilation to day 28 or death.

Ventilator-Free Days

Patients randomized to sighs had a median of 18.4 VFDs (IQR, 7.0-25.2) during the first 28 days compared with 16.1 VFDs (IQR, 1.1-24.4) for those receiving usual care (P = .08) (Table 2). The mean difference in VFDs between groups was 1.9 days (95% CI, 0.1-3.6). Participants randomized to sighs had a shorter time to successful extubation (subdistribution hazard ratio, 1.21 [95% CI, 1.00-1.47]; P = .05; Figure 2). Patients receiving sighs had a median of 20.0 TVFDs (IQR, 9.0-25.0) compared with 17.0 (IQR, 4.0-24.0) for those receiving usual care (P = .06). The mean difference in TVFDs between groups was 1.9 days (95% CI, 0.2-3.6). Among individuals who survived to day 28, no significant difference in VFDs or TVFDs between treatment groups was observed. Patients receiving sighs had more VFDs in all 23 post hoc exploratory subgroups analyzed and no significant interactions between treatment assignment and any subgroup were detected (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2).

Mortality

The prespecified, secondary end point of 28-day mortality was 11.6% (30/259) in patients receiving sighs and 17.6% (46/261) in those receiving usual care (odds ratio, 0.61 [95% CI, 0.37-1.00]; P = .05). The unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios for death associated with sighs compared with usual care were 0.64 (95% CI, 0.41-1.02; P = .06) and 0.70 (95% CI, 0.43-1.15; P = .16), respectively (Figure 2). No differences were found in the causes of death between the 2 groups (Table 3).

Table 3. Complications and Serious Adverse Events (SAEs).

| Event/complication | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sighs + usual care (n = 259) | Usual care alone (n = 261) | |

| Fatal events | 30 (11.6) | 46 (17.6) |

| Brain injury | 20 (66.7) | 30 (65.2) |

| Multiple traumas | 4 (13.3) | 6 (13.0) |

| Hemorrhagic shock | 3 (10.0) | 3 (6.5) |

| Respiratory | 2 (6.7) | 3 (6.5) |

| Cardiac | 1 (3.3) | 2 (4.3) |

| Multiorgan failure | 0 | 1 (2.2) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 0 | 1 (2.2) |

| Nonfatal SAEs | ||

| Total SAEs, No. (count per person) | 118 (0.456) | 111 (0.425) |

| Experienced ≥1 SAE | 80 (30.9) | 80 (30.7) |

| Pneumonia | 22 (8.5) | 22 (8.4) |

| Pneumothorax | 18 (6.9) | 20 (7.7) |

| DVT/PE | 10 (3.9) | 13 (5.0) |

| Respiratory | 12 (4.6) | 10 (3.8) |

| Infection/sepsisa | 9 (3.5) | 12 (4.6) |

| Stroke | 7 (2.7) | 7 (2.7) |

| Gastrointestinal bleed | 6 (2.3) | 6 (2.3) |

| Cardiovascular | 6 (2.3) | 5 (1.9) |

| Septic shock | 6 (2.3) | 3 (1.1) |

| Hypotension | 7 (2.7) | 0 |

| Hemorrhagic shock | 3 (1.2) | 2 (0.8) |

| Otherb | 5 (1.9) | 4 (1.5) |

| Complications and medication use | ||

| Sedative use | 246 (95.0) | 255 (97.7) |

| Days of use, median (IQR) | 7.0 (3.0-12.0) | 7.0 (3.0-14.5) |

| Used blood products | 143 (55.2) | 143 (54.8) |

| Days of use, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) |

| Pressor use | 127 (49.0) | 120 (46.0) |

| Days of use, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0-4.5) | 3.0 (2.0-5.0) |

| Ventilator-associated pneumoniac | 57 (22.0) | 69 (26.4) |

| Rib platingd | 10 (3.9) | 4 (1.5) |

| Pneumatocele | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) |

Abbreviations: DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Other than pneumonia.

Includes conditions with <5 total events.

Defined as pneumonia recorded while the individual was intubated that occurred at least 24 hours after initial intubation.

Defined as inserting plates and screws to stabilize broken ribs.

Other Secondary and Tertiary End Points

Patients randomized to sighs had a median of 13.7 ICU-free days (IQR, 2.0-20.6) compared with 11.9 (IQR, 0-20.0) for patients receiving usual care (P = .10, Table 2).

Time to development of Pao2/Fio2 ratios and/or bilateral or diffuse infiltrates consistent with ARDS were similar between groups as was discharge status (eFigure 2 and eTables 3-4 in Supplement 2).

We found no difference in the incidence of complications in the 2 groups (Table 3). The number of nonfatal severe adverse events was similar between groups, but more patients receiving sighs had hypotension reported as an adverse event (7 vs 0 in the usual care group, Table 3). Of the 7, however, 2 had no association with sighs because the hypotension occurred 13 days after extubation in one and prior to sighs being implemented in the other. In the remaining 5, hypotension was temporally related to the sigh breaths but 4 were receiving pressors at the time sighs were implemented and 1 was also being ventilated with 30 cm H2O of positive end-expiratory pressure.

Discussion

In this pragmatic, randomized trial of 524 patients, the change in the distributions of VFDs in the 2 groups did not reach statistical significance (Wilcoxon sign rank P = .08) with the addition of sigh breaths to usual care but the difference in VFDs increased by an unadjusted mean of 1.9 days (least-squares regression P = .04) compared with usual care alone among trauma patients with risk factors for developing ARDS. The prespecified secondary outcome of mortality was also lower in patients receiving sighs (odds ratio P = .05). No significant difference in length of ICU stay or nonfatal adverse events was observed. Five patients receiving sighs (1.9%) had hypotension attributable to sighs but 4 of these were receiving pressors prior to the administration of sighs.

The difference in VFDs between treatment groups did not reach statistical significance using the Wilcoxon rank-sum statistic and could have occurred by chance, but a stronger signal was found when differences in mean VFDs were compared between groups and when analyzed using a competing-risks approach. The observed differences in VFDs were likely driven by the difference in mortality between treatment groups because VFDs were comparable in survivors of both groups. As noted by Schoenfeld and Bernard,25 parametric tests of VFDs are dependent on the length of the study, with the difference between early extubation and mortality weighted more strongly with a longer study period. Nonparametric tests, such as the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, are less dependent on length of the study and weight mortality and duration of ventilation similarly. This could explain why a stronger signal was identified using the parametric approach vs the nonparametric approach. In addition, a study published after the current study began found that using a competing-risks approach was more powerful than the Wilcoxon rank-sum test when the effect of an intervention on VFDs was primarily through mortality.26 Hence, in hindsight, specifying a competing-risks analysis for VFDs may have been a more appropriate approach. Given the low mortality of patients with trauma, selecting mortality as the primary end point would have required enrolling an unrealistic number of patients. The mechanism linking sighs with a lower mortality can only be speculated.

No difference was found in the timing or number of patients developing ventilator-associated pneumonia or findings consistent with ARDS between the 2 treatment groups but this study was underpowered to find clinically meaningful differences in these complications given the low incidence observed in both groups. In addition, blood gases and x-rays were not obtained in a consistent fashion given the pragmatic nature of the study design. The reduced mortality in patients receiving sighs largely resulted from fewer patients dying of traumatic brain injury or multiple traumas. The rationale for sighs is that they reduce VILI. Accordingly, sighs could have reduced the extent of VILI-associated biotrauma contributing to these injuries as might occur through the link between stretch-activated mechanoreceptors and the immune response.27

Only 1 previous study has assessed the long-term effects of sighs: a phase 2 trial investigating the safety of sighs in patients with acute hypoxic respiratory failure and ARDS (the PROTECTION study).19 In this trial, no difference was observed in VFDs, the length of ICU stay, mortality, or adverse events. Several differences between the current study and PROTECTION limit directly comparing results from the 2 trials. First, all of the patients in PROTECTION had acute hypoxic failure defined as a Pao2/Fio2 ratio of less than 300 (median: 222) and half had ARDS as defined by a Pao2/Fio2 ratio of less than 300 and bilateral infiltrates on enrollment. In the current study, only 43% of the patients had Pao2/Fio2 ratios of less than 300 (median: 325) and less than 15% had ARDS defined by the same criteria. These 2 differences, plus the current finding in subgroup analysis that sighs were associated with more VFDs in patients with Pao2/Fio2 ratios greater than 300, suggests that the benefits of sighs might be greater in patients without ARDS or when they are administered prior to the development of ARDS. Second, only approximately 7% of the patients in PROTECTION had an admitting diagnosis of trauma. Third, more than twice the number of patients were enrolled in the current study than reported in PROTECTION.

While sighs likely resulted in some degree of alveolar recruitment, they were not applied as recruitment maneuvers but rather to facilitate surfactant secretion by stretching the type II pneumocytes. Single sigh breaths over 5 seconds every 6 minutes were administered in this study until the patients were breathing without ventilatory assistance. Studies of recruitment maneuvers generally applied Pplats of 35 or 40 cm H2O as in this study, but for 20 to 40 seconds, with up to 3 consecutive breaths given but no more than 4 times per day.28 These studies reported improvements in gas exchange, compliance, end-expiratory lung volume, and/or the respiratory pattern. Because all of these improvements reversed gradually over 20 to 60 minutes when returning to the prerecruitment levels of PEEP and/or VT,27 and because concurrent hypotension frequently developed in conjunction with delivering recruitment maneuvers, the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine guidelines recommend against using recruitment maneuvers.29 Hypotension was also found to be temporally related to sighs but this only occurred in 5 patients and 4 of these required pressors prior to receiving sighs. The infrequent occurrence of hypotension was likely related to not holding the increased distending pressure for any extended duration. The transient improvements reported in studies of recruitment maneuvers would be consistent with the higher Pplats causing surfactant secretion, which facilitated recruitment. The gradual reversal of these improvements on resumption of CVTV would be consistent with surfactant inactivation or depletion leading to derecruitment.

Limitations

This study has a number of limitations. First, the pragmatic design did not specify when arterial blood gas sampling or imaging should be obtained. While this limited expenses, patient discomfort, and unnecessary testing, it compromised the ability to evaluate the effect of sighs on gas exchange and roentgenographic changes over time, which, in turn, limited the ability to determine whether sighs altered the development of ARDS/VILI. Second, this study is underpowered to assess the effect of sighs on the development of ARDS because only a fraction of patients with any risk factor for ARDS actually develop ARDS. Third, the findings would be more generalizable if patients with other risk factors predisposing to ARDS were included, particularly because patients with trauma seem to have a lower incidence of ARDS and lower mortality if they develop ARDS than those with other risk factors, even when adjusting for the younger age of trauma patients.30 Enrollment was limited to patients with trauma because the trial was funded by the Department of Defense.

Fourth, subjective factors contribute to the decision to wean patients from mechanical ventilation. These could bias the VFDs and TVFDs end points because investigators, patients, and treating physicians could not be blinded to the intervention. Fifth, these conclusions could be strengthened had phospholipids and surface tension–lowering ability of bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and/or inflammatory biomarkers in BAL or blood in these patients had been measured. BAL or biomarker assessment was not performed because of funding limitations, the pragmatic study design, not knowing when in the hospital course BAL or blood sampling should be obtained, and concerns that the invasive nature of the BAL procedure might limit consent to participate. Pison and colleagues31 demonstrated that surfactant abnormalities in BAL fluid developed progressively in trauma patients, but only an extensive literature can be cited supporting that these abnormalities are reversed by adding sighs.1 Sixth, finding a difference in the effect of sighs on VFDs as a function of body mass index could be because the Pplat of 40 cm H2O that was empirically selected underestimated the effect of obesity on chest wall compliance.

Conclusions

In a pragmatic, randomized trial among trauma patients receiving mechanical ventilation with risk factors for developing acute respiratory distress syndrome, the addition of sigh breaths did not significantly increase ventilator-free days. Prespecified secondary outcome data suggest that sighs are well-tolerated and may improve clinical outcomes.

Section Editor: Christopher Seymour, MD, Associate Editor, JAMA (christopher.seymour@jamanetwork.org).

Trial Protocol

eMethods

eReferences

eFigure 1. Relationship Between Treatment Assignment and VFDs in Patient Groups

eFigure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimate of Time to Development of P/F ≤300, P/F ≤200, P/F ≤100, P/F ≤300 and Bilateral/Diffuse Infiltrates, P/F ≤200 and Bilateral/Diffuse Infiltrates, P/F ≤100 and Bilateral/Diffuse Infiltrates, and Bilateral or Diffuse Infiltrates

eTable 1. Ventilator Mode and Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale During Follow-Up by Treatment Assignment

eTable 2. Study Outcomes for Complete Case Adjusted Analyses

eTable 3. Lowest Observed Partial Pressure of Oxygen to the Fraction of Inspired Oxygen (P/F) Ratio During Follow-Up for Individuals Without P/F Ratios Consistent With ARDS (P/F >300) at Baseline

eTable 4. Status at Discharge

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Albert RK. Constant Vt ventilation and surfactant dysfunction: an overlooked cause of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205(2):152-160. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202107-1690CP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mead J, Takishima T, Leith D. Stress distribution in lungs: a model of pulmonary elasticity. J Appl Physiol. 1970;28(5):596-608. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1970.28.5.596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albert RK, Smith B, Perlman CE, Schwartz DA. Is progression of pulmonary fibrosis due to ventilation-induced lung injury? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(2):140-151. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201903-0497PP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Faridy EE. Effect of distension on release of surfactant in excised dogs’ lungs. Respir Physiol. 1976;27(1):99-114. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(76)90021-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildebran JN, Goerke J, Clements JA. Surfactant release in excised rat lung is stimulated by air inflation. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. 1981;51(4):905-910. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1981.51.4.905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholas TE, Power JHT, Barr HA. The pulmonary consequences of a deep breath. Respir Physiol. 1982;49(3):315-324. doi: 10.1016/0034-5687(82)90119-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wirtz HR, Dobbs LG. Calcium mobilization and exocytosis after one mechanical stretch of lung epithelial cells. Science. 1990;250(4985):1266-1269. doi: 10.1126/science.2173861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietl P, Frick M, Mair N, Bertocchi C, Haller T. Pulmonary consequences of a deep breath revisited. Biol Neonate. 2004;85(4):299-304. doi: 10.1159/000078176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferris BG Jr, Pollard DS. Effect of deep and quiet breathing on pulmonary compliance in man. J Clin Invest. 1960;39(1):143-149. doi: 10.1172/JCI104012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caro CG, Butler J, Dubois AB. Some effects of restriction of chest cage expansion on pulmonary function in man: an experimental study. J Clin Invest. 1960;39(4):573-583. doi: 10.1172/JCI104070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pattle RE. Surface lining of lung alveoli. Physiol Rev. 1965;45:48-79. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1965.45.1.48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pelosi P, Cadringher P, Bottino N, et al. Sigh in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159(3):872-880. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9802090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foti G, Cereda M, Sparacino ME, De Marchi L, Villa F, Pesenti A. Effects of periodic lung recruitment maneuvers on gas exchange and respiratory mechanics in mechanically ventilated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(5):501-507. doi: 10.1007/s001340051196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patroniti N, Foti G, Cortinovis B, et al. Sigh improves gas exchange and lung volume in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome undergoing pressure support ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(4):788-794. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200204000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reiss LK, Kowallik A, Uhlig S. Recurrent recruitment manoeuvres improve lung mechanics and minimize lung injury during mechanical ventilation of healthy mice. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24527. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moraes L, Santos CL, Santos RS, et al. Effects of sigh during pressure control and pressure support ventilation in pulmonary and extrapulmonary mild acute lung injury. Crit Care. 2014;18(4):474. doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0474-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mauri T, Eronia N, Abbruzzese C, et al. Effects of sigh on regional lung strain and ventilation heterogeneity in acute respiratory failure patients undergoing assisted mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2015;43(9):1823-1831. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tabuchi A, Nickles HT, Kim M, et al. Acute lung injury causes asynchronous alveolar ventilation that can be corrected by individual sighs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(4):396-406. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201505-0901OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mauri T, Foti G, Fornari C, et al. ; PROTECTION Trial Collaborators . Sigh in patient with acute hypoxemic respiratory failure and ARDS: the PROTECTION pilot randomized clinical trial. Chest. 2021;159(4):1426-1436. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.10.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bendixen HH, Smith GM, Mead J. Pattern of ventilation in young adults. J Appl Physiol. 1964;19:195-198. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1964.19.2.195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. ; ARDS Definition Task Force . Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2526-2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rice TW, Wheeler AP, Thompson BT, et al. ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network . Initial trophic vs full enteral feeding in patients with acute lung injury: the EDEN randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307(8):795-803. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiedemann HP, Wheeler AP, Bernard GR, et al. ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) Clinical Trials Network . Comparison of two fluid-management strategies in acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2564-2575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fine JP, Gray PJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoenfeld DA, Bernard GR; ARDS Network . Statistical evaluation of ventilator-free days as an efficacy measure in clinical trials of treatments for acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(8):1772-1777. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200208000-00016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yehya N, Harhay MO, Curley MAQ, Schoenfeld DA, Reeder RW. Reappraisal of ventilator-free days in critical care research. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):828-836. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-2050CP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cremin M, Schreiber S, Murray K, Tay EXY, Reardon C. The diversity of neuroimmune circuits controlling lung inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2023;324(1):L53-L63. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00179.2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fan E, Wilcox ME, Brower RG, et al. Recruitment maneuvers for acute lung injury: a systematic review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(11):1156-1163. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-335OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grasselli G, Calfee CS, Camporota L, et al. ; European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Taskforce on ARDS . ESICM guidelines on acute respiratory distress syndrome: definition, phenotyping and respiratory support strategies. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49(7):727-759. doi: 10.1007/s00134-023-07050-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calfee CS, Eisner MD, Ware LB, et al. ; Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute . Trauma-associated lung injury differs clinically and biologically from acute lung injury due to other clinical disorders. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(10):2243-2250. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000280434.33451.87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pison U, Seeger W, Buchhorn R, et al. Surfactant abnormalities in patients with respiratory failure after multiple trauma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140(4):1033-1039. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.4.1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eMethods

eReferences

eFigure 1. Relationship Between Treatment Assignment and VFDs in Patient Groups

eFigure 2. Kaplan-Meier Estimate of Time to Development of P/F ≤300, P/F ≤200, P/F ≤100, P/F ≤300 and Bilateral/Diffuse Infiltrates, P/F ≤200 and Bilateral/Diffuse Infiltrates, P/F ≤100 and Bilateral/Diffuse Infiltrates, and Bilateral or Diffuse Infiltrates

eTable 1. Ventilator Mode and Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale During Follow-Up by Treatment Assignment

eTable 2. Study Outcomes for Complete Case Adjusted Analyses

eTable 3. Lowest Observed Partial Pressure of Oxygen to the Fraction of Inspired Oxygen (P/F) Ratio During Follow-Up for Individuals Without P/F Ratios Consistent With ARDS (P/F >300) at Baseline

eTable 4. Status at Discharge

Data Sharing Statement