Abstract

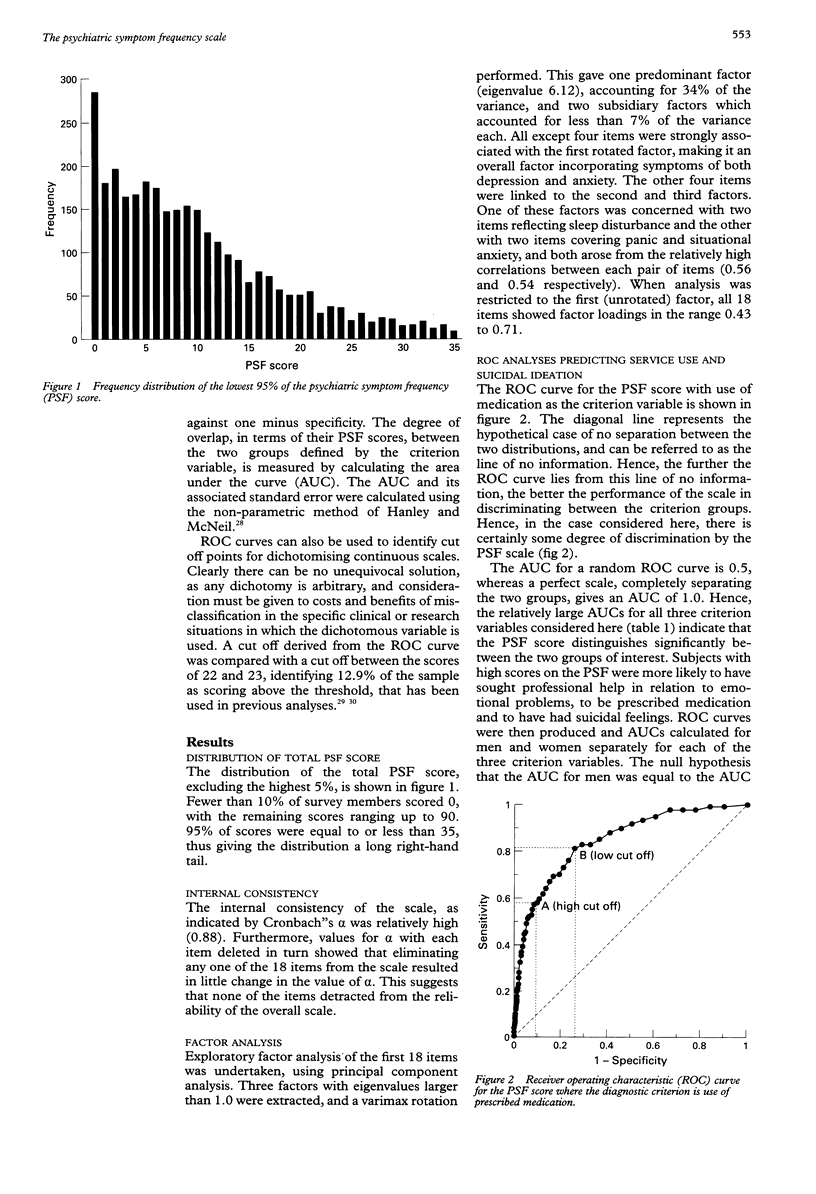

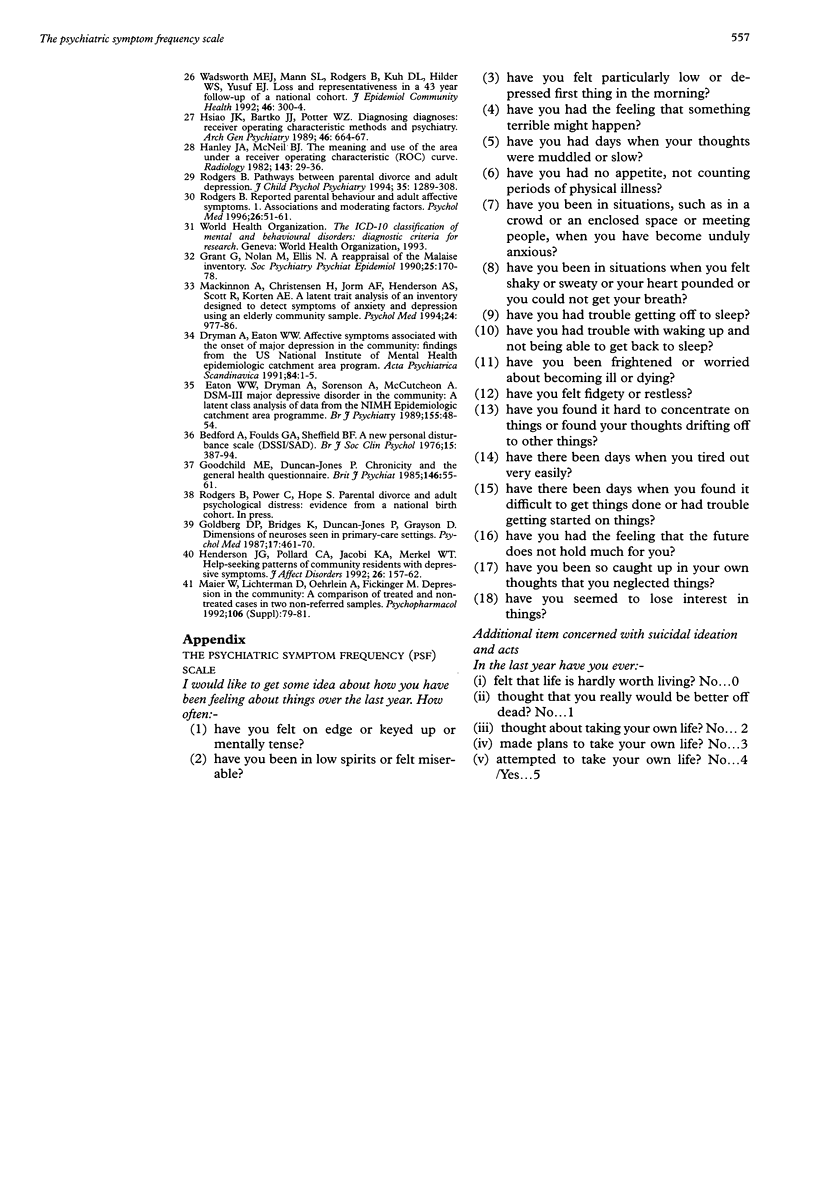

OBJECTIVES: The psychiatric symptom frequency (PSF) scale was developed to assess symptoms of anxiety and depression (i.e. affective symptoms) experienced over the past year in the general population. This study aimed to examine the distribution of PSF scores, internal consistency, and factor structure and to investigate relationships between total scores for this scale and other indicators of poor mental health. PARTICIPANTS: The Medical Research Council national survey of health and development, a class stratified cohort study of men and women followed up from birth in 1946, with the most recent interview at age 43 when the PSF scale was administered. MAIN RESULTS: The PSF scale showed high internal consistency between the 18 items (Cronbach's alpha = 0.88). Ratings on items of the scale reflected one predominant factor, incorporating both depression and anxiety, and two additional factors of less statistical importance, one reflecting sleep problems and the other panic and situational anxiety. Total scores were calculated by adding 18 items of the scale, and high total scores were found to be strongly associated with reports of contact with a doctor or other health professional and use of prescribed medication for "nervous or emotional trouble or depression," and with suicidal ideas. CONCLUSIONS: The PSF is a useful and valid scale for evaluating affective symptoms in the general population. It is appropriate for administration by lay interviewers with minimal training, is relatively brief, and generates few missing data. The total score is a flexible measure which can be used in continuous or binary form to suit the purposes of individual investigations, and provides discrimination at lower as well as upper levels of symptom severity.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bedford A., Foulds G. A., Sheffield B. F. A new personal disturbance scale (DSSI/sAD). Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1976 Nov;15(4):387–394. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1976.tb00050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend B. P., Shrout P. E., Egri G., Mendelsohn F. S. Nonspecific psychological distress and other dimensions of psychopathology. Measures for use in the general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980 Nov;37(11):1229–1236. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1980.01780240027003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dryman A., Eaton W. W. Affective symptoms associated with the onset of major depression in the community: findings from the US National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area Program. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991 Jul;84(1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1991.tb01410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton W. W., Dryman A., Sorenson A., McCutcheon A. DSM-III major depressive disorder in the community. A latent class analysis of data from the NIMH epidemiologic catchment area programme. Br J Psychiatry. 1989 Jul;155:48–54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.155.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton W. W., Ritter C. Distinguishing anxiety and depression with field survey data. Psychol Med. 1988 Feb;18(1):155–166. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700001987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman L. A. Distinguishing depression and anxiety in self-report: evidence from confirmatory factor analysis on nonclinical and clinical samples. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993 Aug;61(4):631–638. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg D. P., Hillier V. F. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979 Feb;9(1):139–145. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700021644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodchild M. E., Duncan-Jones P. Chronicity and the General Health Questionnaire. Br J Psychiatry. 1985 Jan;146:55–61. doi: 10.1192/bjp.146.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant G., Nolan M., Ellis N. A reappraisal of the Malaise Inventory. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1990 Jul;25(4):170–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00782957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley J. A., McNeil B. J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982 Apr;143(1):29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson J. G., Jr, Pollard C. A., Jacobi K. A., Merkel W. T. Help-seeking patterns of community residents with depressive symptoms. J Affect Disord. 1992 Nov;26(3):157–162. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(92)90011-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst M. A. Evaluating the Malaise Inventory. An item analysis. Soc Psychiatry. 1983;18(4):181–184. doi: 10.1007/BF00583528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao J. K., Bartko J. J., Potter W. Z. Diagnosing diagnoses. Receiver operating characteristic methods and psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989 Jul;46(7):664–667. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1989.01810070090014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt C., Andrews G. Comorbidity in the anxiety disorders: the use of a life-chart approach. J Psychiatr Res. 1995 Nov-Dec;29(6):467–480. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(95)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., McGonagle K. A., Zhao S., Nelson C. B., Hughes M., Eshleman S., Wittchen H. U., Kendler K. S. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994 Jan;51(1):8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon A., Christensen H., Jorm A. F., Henderson A. S., Scott R., Korten A. E. A latent trait analysis of an inventory designed to detect symptoms of anxiety and depression using an elderly community sample. Psychol Med. 1994 Nov;24(4):977–986. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700029068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee R., Williams S., Silva P. A. An evaluation of the Malaise Inventory. J Psychosom Res. 1986;30(2):147–152. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(86)90044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B. Behaviour and personality in childhood as predictors of adult psychiatric disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1990 Mar;31(3):393–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb01577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B., Mann S. A. The reliability and validity of PSE assessments by lay interviewers: a national population survey. Psychol Med. 1986 Aug;16(3):689–700. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700010436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B. Pathways between parental divorce and adult depression. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1994 Oct;35(7):1289–1308. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01235.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers B. Reported parental behaviour and adult affective symptoms. 1. Associations and moderating factors. Psychol Med. 1996 Jan;26(1):51–61. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700033717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth M. E., Mann S. L., Rodgers B., Kuh D. J., Hilder W. S., Yusuf E. J. Loss and representativeness in a 43 year follow up of a national birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992 Jun;46(3):300–304. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.3.300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing J. K. Use and misuse of the PSE. Br J Psychiatry. 1983 Aug;143:111–117. doi: 10.1192/bjp.143.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]