Abstract

Introduction

Treatment response to the standard therapy is low for metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs) mainly due to the tumor heterogeneity. We investigated the heterogeneity between primary PanNETs and metastases to improve the precise treatment.

Methods

The genomic and transcriptomic data of PanNETs were retrieved from the Genomics, Evidence, Neoplasia, Information, Exchange (GENIE), and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, respectively. Potential prognostic effects of gene mutations enriched in metastases were investigated. Gene set enrichment analysis was performed to investigate the functional difference. Oncology Knowledge Base was interrogated for identifying the targetable gene alterations.

Results

Twenty-one genes had significantly higher mutation rates in metastases which included TP53 (10.3% vs. 16.9%, p = 0.035) and KRAS (3.7% vs. 9.1%, p = 0.016). Signaling pathways related to cell proliferation and metabolism were enriched in metastases, whereas epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and TGF-β signaling were enriched in primaries. Gene mutations were highly enriched in metastases that had significant unfavorable prognostic effects included mutation of TP53 (p < 0.001), KRAS (p = 0.001), ATM (p = 0.032), KMT2D (p = 0.001), RB1 (p < 0.001), and FAT1 (p < 0.001). Targetable alterations enriched in metastases included mutation of TSC2 (15.5%), ARID1A (9.7%), KRAS (9.1%), PTEN (8.7%), ATM (6.4%), amplification of EGFR (6.0%), MET (5.5%), CDK4 (5.5%), MDM2 (5.0%), and deletion of SMARCB1 (5.0%).

Conclusion

Metastases exhibited a certain extent of genomic and transcriptomic diversity from primary PanNETs. TP53 and KRAS mutation in primary samples might associate with metastasis and contribute to a poorer prognosis. A high fraction of novel targetable alterations enriched in metastases deserves to be validated in advanced PanNETs.

Keywords: Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, Molecular heterogeneity, Metastasis, Targeted therapy, Genetics

Introduction

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) are a group of rare tumors that have extensive heterogeneity in terms of histologic origins, degree of differentiation, tumor grades, and presence or absence of functional symptoms [1]. According to the differentiation, NENs can be classified into well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs) [1]. NENs can arise at almost any anatomical site and are distributed throughout the body in organs of all types [1]. The pancreas was one of the most common primary sites for NENs ranked after the lung, small intestine, and rectum [2]. In the USA, the annual incidence of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs) has increased from 0.3 to 1.0 cases per 100,000 per year over the last 2 decades [3]. In China and India, the pancreas was the most prevalent primary site of NENs in the digestive system [4]. Although PanNETs usually behave indolent growth compared with poorly differentiated NEC of the pancreas, metastasis of PanNETs is frequently observed. According to the statistics, about 64% of PanNET patients present with metastatic disease at initial diagnosis [5]. Besides, distant metastasis also frequently occurred in resected PanNET patients as a common cause of recurrence [6, 7]. Unfortunately, the prognosis of metastatic PanNET patients is extremely poor with median overall survival (OS) of 20–24 months compared with that of 136–230 and 77–90 months for localized and regional PanNET patients, respectively [2, 5]. Currently, available treatment options for advanced metastatic PanNETs included somatostatin analogs, mTOR inhibitors (like everolimus), receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors (like sunitinib and surufatinib), cytotoxic chemotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, and peptide receptor radionuclide therapy [8]. Despite the multiple therapeutic options, the response rate is overall low [8]. And the primary and secondary drug resistance and adverse events are intractable issues for the clinical management of advanced PanNET patients. More precise targeted therapies are needed to increase the response rate and reduce the side effects. One important factor influencing the effectiveness of treatment in PanNETs is tumor heterogeneity [9]. However, most previous comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic studies rarely focused on the difference in molecular characteristics between the primary and metastatic lesions in PanNETs [10–12], thus limiting the understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the metastasis and further impeding the finding of therapeutic targets in advanced PanNET patients. In this study, we systematically investigated the molecular and functional heterogeneity between primary lesions and metastases of PanNETs based on the publicly available genomic and transcriptomic datasets, aiming at providing insight into the molecular change underlying the disease course along with metastasis and paving the way for biomarker-directed precise treatment in advanced PanNET patients.

Materials and Methods

Datasets and Patients

The genomic datasets of PanNET were retrieved from the American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) Project Genomics, Evidence, Neoplasia, Information, Exchange (GENIE) database (version 11.1) (dataset accession number: syn26706564; available from https://doi.org/10.7303/syn26706564) [13]. Six files including data_clinical_patient.txt, data_clinical_sample.txt, data_CNA.txt, data_fusons.txt, data_mutations_extended.txt, and genomic_information.txt were downloaded from the GENIE database. Somatic nonsynonymous mutation types include missense, nonsense, in-frame (including in-frame insertion and deletion), frameshift (including frameshift insertion and deletion), splice site, and translation start site mutation and type of copy number variation (CNV) including copy number amplification (CNA) and copy number loss (CNL) were analyzed. Another independent dataset retrieved from cBioportal (available from http://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=panet_arcnet_2017) [14] was used to validate the prognostic effect of gene mutations. The transcriptomic datasets of PanNETs, GSE73338 (available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE73338) [12], and GSE73339 (available from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE73339) [15] were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. GSE73338 contained 81 primary PanNET samples and 7 metastases, while GSE73339 included 20 primary and 9 metastatic samples. The two datasets were merged for analysis. Because the datasets used in this study are publicly accessible, institutional review of the study is unnecessary.

Bioinformatic Analysis

Bioinformatic analysis was performed by R software (v 4.1.2). The alteration rate of each gene including somatic mutation and CNV rates was defined as the percentage of samples with a gene alteration in the total number of samples with the gene tested. Gene alteration frequency and type were shown in the heatmap generated by the ComplexHeatmap package (v 2.8.0). Comparisons of gene alteration rates between the primary and metastatic samples were shown by scatterplots using the ggplot2 package (v 3.3.5). Sva package (v 3.40.0) was used to merge the transcriptomic datasets and correct the batch effects. Analysis of genes with differential expression between primary and metastatic samples was performed by limma package (v 3.48.3). The cut-offs of the absolute value of log (fold change) (|log FC|) and p value were set to 1 and 0.05, respectively. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed by clusterProfiler package (v 4.2.2) using the gene gets of HALLMARK, Gene Ontology (GO), and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) downloaded from Molecular signature database (Msigdb). Potentially targetable gene alterations (PTGAs) were interrogated by the Precision Oncology Knowledge Base (OncoKB) website (https://oncokb.org/).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by R software (v 4.1.2). Numerical variables with continuous normal distribution were stated as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were stated as counts with the percentage. The Student’s t test was applied to determine the significance of the difference in gene expression between primary and metastatic PanNET samples. Fisher’s exact test was used for comparing the gene alteration rates between primary and metastatic PanNET samples. OS was defined as the interval from the age at the sequencing report to the age at the date of death or the age at the date of the last contact if death has not occurred. The survival curves were plotted based on the Kaplan-Meier method, with the log-rank test applied for significance testing of survival differences between groups. The Cox regression model was used for calculating the hazard ratio (HR). Survival analysis was carried out by Survival (v 3.2–13) and Survminer package (v 0.4.9). All statistical tests were bilateral, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Overview of Genetic Variations with High Frequency in PanNET

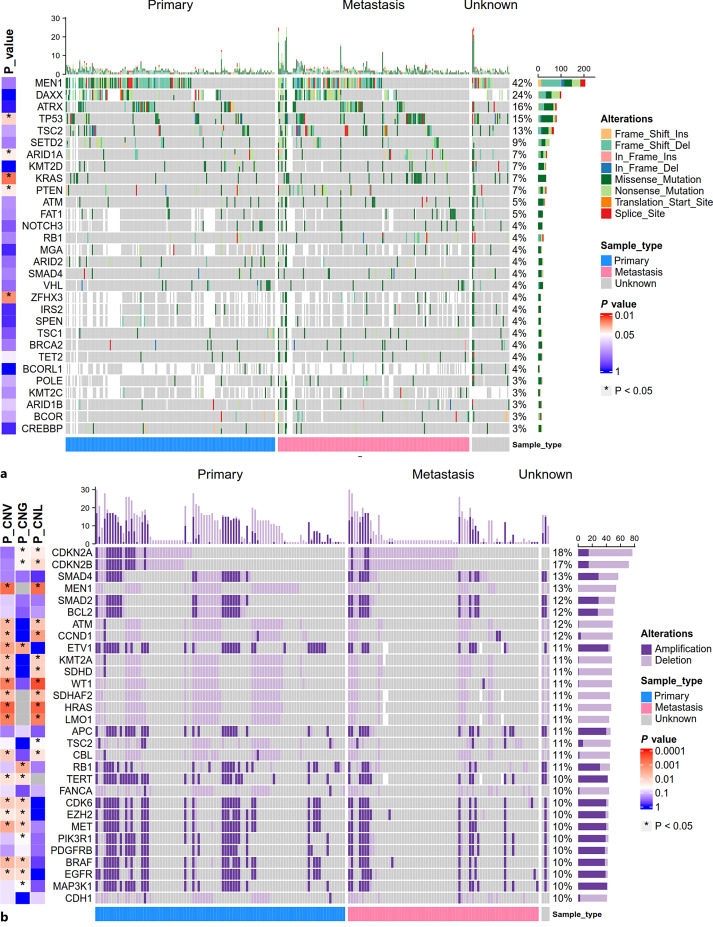

In total, 523 samples (including 243 primary PanNET samples, 242 metastatic PanNET samples, and 38 samples of unknown origins) from 497 PanNET patients were included for somatic mutation analysis. In parallel, 426 samples (including 221 primary PanNET samples, 201 metastatic PanNET samples, and 4 samples of unknown origins) from 402 PanNET patients were included for CNV analysis. The basic characteristics of included patients and samples are shown in Table 1. For somatic mutation, mutations with the top frequency included MEN1 (42.4%, 202/476), DAXX (23.9%, 94/393), ATRX (16.5%, 81/491), TP53 (14.5%, 76/523), TSC2 (12.9%, 64/496), and SETD2 (9.0%, 44/491) (Fig. 1a). For CNV (including CNA and CNL), genes with the top frequency included CDKN2A (18.1%, 77/426), CDKN2B (16.9%, 72/426), SMAD4 (13.4%, 57/426), MEN1 (12.7%, 54/426), SMAD2 (12.2%, 52/426), and BCL2 (11.7%, 50/426) (Fig. 1b). Separately, genes with the top frequency of CNA included ETV1 (10.7%, 43/403), TERT (10.4%, 42/403), MAP3K1 (9.6%, 41/426), APC (9.4%, 40/426), CDK6 (9.4%, 40/426), and MET (9.4%, 40/426) (Fig. 1b). Genes with the top frequency of CNL included CDKN2A (14.6%, 62/426), CDKN2B (13.4%, 57/426), MEN1 (12.7%, 54/426), ATM (11.3%, 48/426), HRAS (11.1%, 47/422) and KMT2A (11.1%, 47/422) (Fig. 1b). For gene fusion, in total, 53 types of gene fusion involved in 58 genes were found in 51/201 samples (including 27 primary PanNET samples, 23 metastases, and 1 sample of unknown origin). The gene fusions presented in more than 1 sample included MEN1 intragenic fusion (n = 5), KMT2A-PHC2 (n = 4), TSC2 intragenic fusion (n = 3), and APC intragenic fusion (n = 2). Detailed information about gene fusion was provided in online supplementary Table S1 (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000530968).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients and sample included in this study

| Characteristic | Genomic data | Transcriptomic data | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | CNV | GSE73338 | GSE73339 | |

| (N = 497) | (N = 402) | (N = 72) | (N = 27) | |

| Mean age, years | 56.2 | 55.3 | 53.0 | 47.2 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 278 (55.9) | 213 (53.0) | 30 (41.7) | 13 (48.1) |

| Female | 217 (43.7) | 187 (46.5) | 42 (58.3) | 14 (51.9) |

| NA | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 399 (80.3) | 339 (84.3) | – | – |

| Black | 24 (4.8) | 21 (5.2) | – | – |

| Asian | 23 (4.6) | 17 (4.2) | – | – |

| Other | 17 (3.4) | 12 (3.0) | – | – |

| NA | 34 (6.8) | 13 (3.2) | – | – |

| Sample location | ||||

| Primary | 243 (46.5) | 221 (51.9) | 81 (92.0) | 20 (69.0) |

| Metastasis | 242 (46.3) | 201 (47.2) | 7 (8.0) | 9 (31.0) |

| NA | 38 (7.3) | 4 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

CNV, copy number variation; NA, not available.

Fig. 1.

Overview of somatic gene mutations and copy number variations (CNVs) with high frequency in primary PanNET samples and metastases. a Mutational landscape of genes with the top 30 frequency in 523 PanNET samples (including 243 primary PanNET samples, 242 metastases, and 38 samples of unknown origins). b The landscape of gene CNVs with the top 30 frequency tested in 426 PanNET samples (including 221 primary PanNET samples, 201 metastases, and 4 samples of unknown origins). Genes not tested in the sample were filled with white blank. Variation frequency was calculated as the proportion of samples with a gene mutation (a) or CNV (b) among the total samples tested for the gene. Samples are split based on sample origins. p value represents the significance of the difference in gene mutation rates (a) and CNV rates (P-CNG: p value for gene CNA rates; P-CNL: p value for gene CNL rate; P-CNV: p value for gene CNV rate) (b) between primary PanNET samples and metastases calculated by the Fisher exact test. p value was log10 scaled and mapped with color.

Genomic Difference between Primary PanNET Samples and Metastases

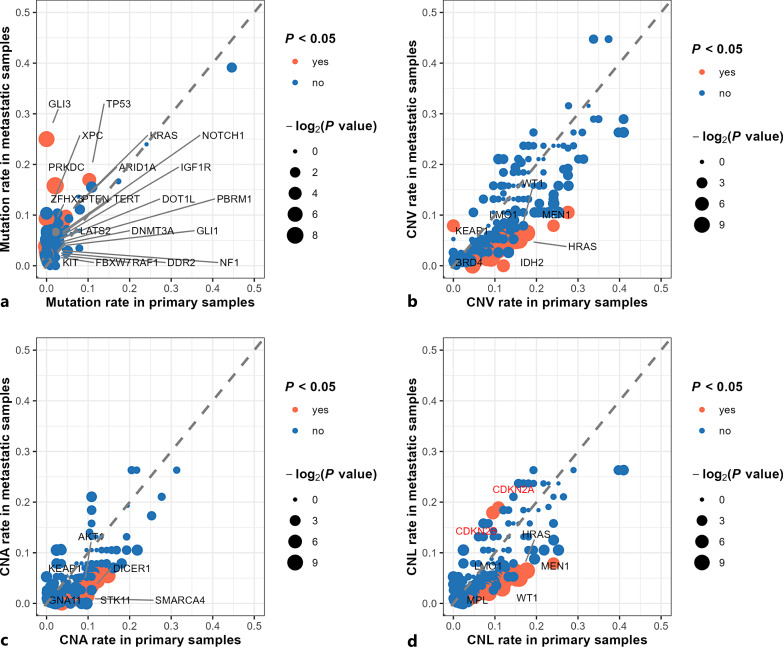

By comparing gene alteration rates between primary PanNET samples and metastases, we found all tested genes with significantly different mutation rates were more highly mutated in metastatic lesions than in primary PanNET samples. In contrast, most of the genes with significantly different CNV rates (including CNA and CNL rates) were more highly altered in primary PanNET samples than in metastatic lesions (Fig. 1, 2). In total, 21 genes had significantly higher mutation rates in metastatic samples which included TP53 (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 10.3% vs. 16.9%, p = 0.035), KRAS (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 3.7% vs. 9.1%, p = 0.016), ARID1A (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 4.6% vs. 9.7%, p = 0.043), PTEN (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 4.1% vs. 8.7%, p = 0.043), IGF1R (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 0.8% vs. 4.5%, p = 0.017), etc (Fig. 1a, 2a; online suppl. Table S2). In sum, 148 genes had significantly different CNV rates between primary and metastatic PanNET samples (Fig. 2b; online suppl. Table S3). Specifically, genes with significantly higher CNA rates in primary PanNET samples included ETV1 (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 14.7% vs. 5.5%, p = 0.003), TERT (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 13.4% vs. 6.0%, p =0.019), MET (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 12.7% vs. 5.5%, p = 0.012), CDK6 (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 12.7% vs. 5.5%, p = 0.012), EGFR (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 12.2% vs. 5.5%, p = 0.017), etc. (Fig. 2c; online suppl. Table S4). Genes with significantly higher CNL rates in primary PanNET samples included MEN1 (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 17.6% vs. 6.5%, p = 0.001), HRAS (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 15.8% vs. 5.1%, p < 0.001), WT1 (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 15.8% vs. 5.0%, p < 0.001), LMO1 (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 15.2% vs. 4.9%, p = 0.001), ATM (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 14.9% vs. 6.5%, p = 0.007), etc. (Fig. 2d; online suppl. Table S5). Of note, only two genes were found to have significantly higher CNL rates in metastases which included CDKN2A (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 10.9% vs. 18.9%, p = 0.027), and CDKN2B (primary PanNET vs. metastases: 9.5% vs. 17.9%, p = 0.015) (Fig. 2d; online suppl. Table S5). Full gene lists of genes with different alteration rates and respective alteration rates between primary and metastatic PanNET samples were provided in online supplementary Table S2-S5. For gene fusion, the majority of gene profiles exhibiting fusions were not shared between primary PanNETs and metastases, except for MEN1 intragenic, KMT2A-PHC2, TSC2 intragenic, APC intragenic fusion (online suppl. Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Genomic difference between primary PanNET and metastatic lesions. Genes with significant different mutation rates (a), copy number variation (CNV) rates (b), copy number amplification (CNA) rates (c), and copy number loss (CNL) rates (d) between primary and metastatic PanNET samples are highlighted with orange and labeled by gene name (in a, genes with p < 0.05 are labeled with black, in b, c, d, genes with p < 0.001 are labeled with black). CDKN2A and CDKN2B deletion were the only CNLs with higher frequency in the metastases with p values of 0.027 and 0.015, respectively. Since the p values are not less than 0.001 for CDKN2A and CDKN2B, the gene names are labeled with red. p value was log2 scaled and mapped with point size. The larger the point size, the less the p value.

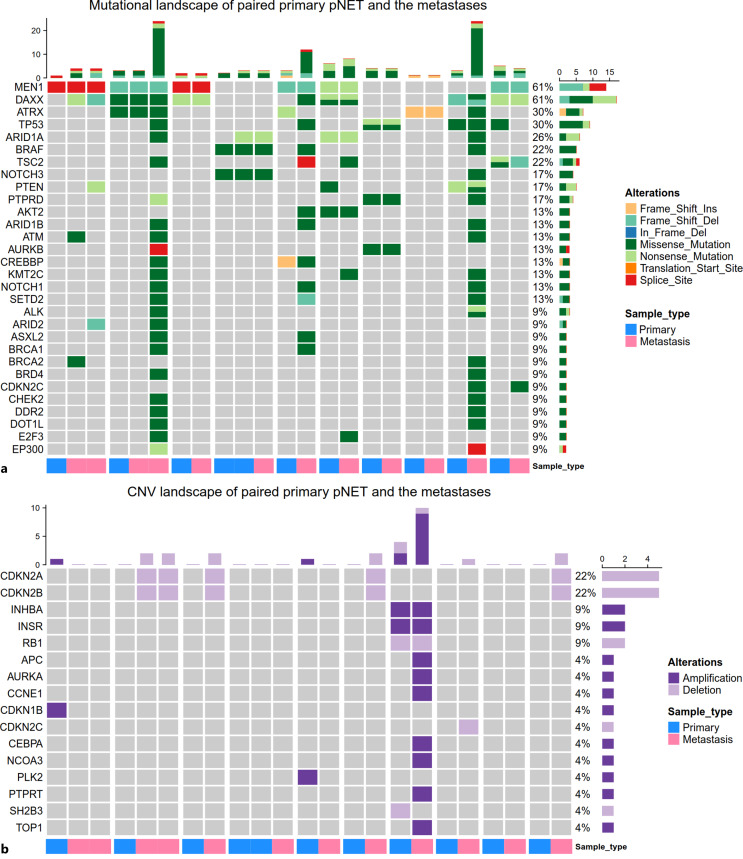

Comparison of Gene Alterations between Paired Primary PanNET Samples and the Metastases

We further compared the gene alterations between paired primary and metastatic samples derived from the same patients. In total, 23 samples from 10 patients who had at least one primary and one metastatic sample were included (Fig. 3). MEN1 mutation was shared in all positive primary and metastatic samples indicating an initial driver role. However, other gene alterations were not consistently present in paired primary and metastatic samples (Fig. 3). For example, among 7 patients with DAXX mutation, 2 patients with DAXX mutation only in the metastases, with primary samples lack of DAXX mutation. Among 4 patients with ATRX mutation, 2 patients had ATRX mutation in both primary and metastatic tumors. However, 1 patient had ATRX mutation exclusively in the primary sample, and the other patient had ATRX mutation only in the metastatic sample (Fig. 3a). One patient with 2 metastatic samples and 1 primary sample harbored TP53 mutation in only one metastatic sample; the other one metastatic sample and the paired primary sample of this patient were lacked a TP53 mutation. Consistent with the analysis of the overall primary and metastatic samples, CDKN2A and CDKN2B deletion were more prevalent in metastases since all of the samples with CDKN2A and CDKN2B deletion are metastatic with absences in the corresponding primary samples (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of gene mutations (a) and copy number variations (CNVs) (b) between paired primary and metastatic samples. Paired samples are placed together and annotated by sample origins at the bottom. Samples from different patients are split by the wide white blank.

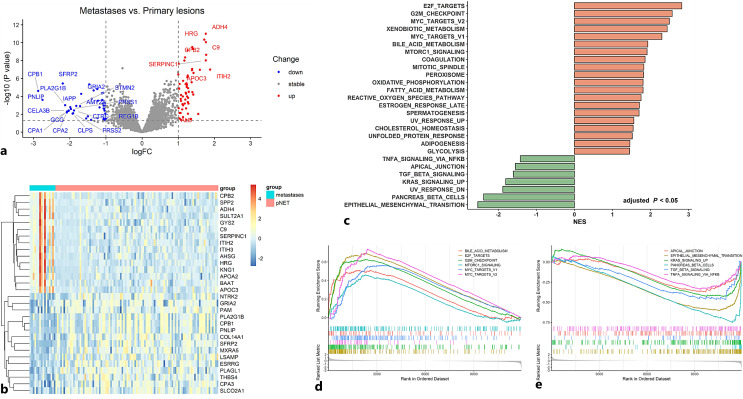

Differences in Gene Expression and Enriched Pathways between Primary PanNET Samples and Metastases

For analysis of the transcriptomic difference between primary PanNET samples and metastases, we merged the two transcriptomic microarray datasets followed by correction of the batch effects. In total, 117 PanNET samples including 101 primary samples and 16 metastases were analyzed. Consequently, 42 genes were up-regulated and 59 genes were down-regulated in metastases compared with primary PanNET samples based on the cut-off of 1.0 for the |log FC| and 0.05 for the p value, respectively (Fig. 4a). The expression of the top 30 differentially expressed genes (including the top 15 genes with higher expression in metastases and top 15 genes with higher expression in primary samples) was shown in the heatmap (Fig. 4b). To investigate the functional and phenotypic difference between the primary and metastatic PanNET samples, we performed the GSEA based on gene sets of the HALLMARK, GO, and KEGG. In total, 27/50 gene sets of the HALLMARK were differentially enriched between primary lesions and metastases based on the adjusted p < 0.05. Among them, 20 gene sets were enriched in metastases with normalized enrichment score (NES) > 0 and 7 gene sets were enriched in primary PanNET samples with NES <0. The top enriched gene sets in metastases included pathways involved in cell proliferation like E2F targets, G2M checkpoint, MYC targets v1 and v2, and pathways involved in metabolisms like xenobiotic metabolism, bile acid metabolism, and mTORc1 signaling. The 7 enriched gene sets in primary PanNET included epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), pancreas beta cells, ultraviolet response down, KRAS signaling up, TGF-β signaling, apical junction, TNF-α signaling via NF-κb (Fig. 4c, e). In total, the results of KEGG showed that 28 pathways were differentially enriched. The enriched pathways in metastases are mainly involved in amino acid, fatty acid, and small molecule compound metabolism, cell cycle, P53 signaling, and DNA replication. The enriched pathways in primary samples are long-term depression, long-term potentiation, and lysosome (online suppl. Fig. S1). In total, 450 terms were generated based on GO analysis. Top-enriched GO terms in metastases included blood microparticle, organic acid catabolic process, protein-containing complex remodeling, complement activation, etc. Top-enriched GO terms in primary samples included extracellular matrix disassembly, c21 steroid hormone biosynthetic process, neuron projection regeneration, positive regulation of hormone metabolic process, etc. (online suppl. Fig. S2).

Fig. 4.

Difference of gene expression and enriched pathways between primary PanNET samples and metastases. a The volcano plot shows the differentially expressed genes between primary PanNET samples and metastases. The cut-off value of the |log fold change| (|log FC|) and P is set at 1 and 0.05, respectively, for determining differentially expressed genes. Genes with the |log FC| > 1.5 and p < 0.05 are labeled by gene name. b The heatmap shows the mRNA expression of the top 30 differentially expressed genes in the merged dataset containing 101 primary PanNET samples and 16 metastases. c Results of gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) based on the HALLMARK gene sets. In total, 27 gene sets were differentially enriched between primary lesion and metastases (including 20 gene sets enriched in metastases with normalized enrichment score (NES) > 0 and 7 gene sets enriched in primary PanNET samples with NES <0). d Selected gene sets enriched in the metastases. e Selected gene sets enriched in the primary PanNET samples.

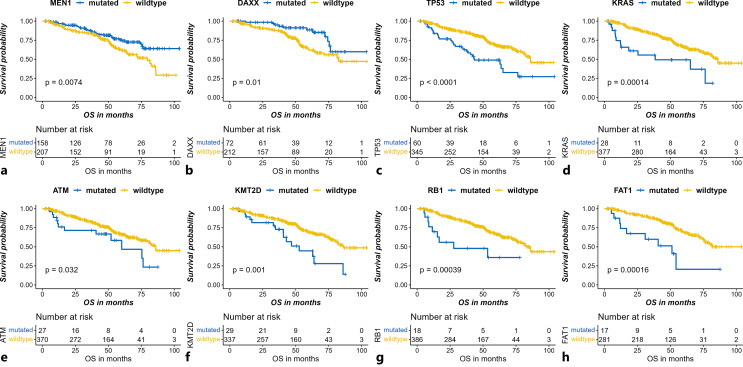

High-Frequency Gene Mutations Enriched in Metastatic Lesions with Significant Prognostic Effects

We compared the OS for all the subgroups stratified by the mutational status of all genes tested. Among the 470 genes mutated in at least one metastatic sample, the mutation status of 87 genes was found to have a statistically significant prognostic effect with the bilateral p value <0.05 for both the log-rank test and the Cox regression model. Here, we focused on the gene mutations with frequencies of more than 5% in metastases of PanNET samples. In total, mutation rates of 8 genes were more than 5% in all metastatic samples. MEN1 and DAXX mutation, which ranked the first and the second frequent mutation, respectively, both had significant favorable prognostic effects (MEN1: mutation rate in metastases [MRIM] 39.1% [81/207], HR 0.57, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.38–0.87, p = 0.008; DAXX: MRIM 24.0% [47/196], HR 0.44, 95% CI: 0.23–0.84, p = 0.013) (Fig. 5a, b). Except for the MEN1 and DAXX mutation, all of the other gene mutations with statistical significance had detrimental prognostic impacts, of which mutation rates above 5% included TP53 (MRIM 16.9% [41/242], HR 2.46, 95% CI: 1.62–3.73, p < 0.001), KRAS (MRIM 9.1% [22/242], HR 2.92, 95% CI: 1.64–5.21, p < 0.001), ATM (MRIM 6.4% [15/235], HR 1.90, 95% CI: 1.05–3.46, p = 0.035), FAT1 (MRIM 6.3% [12/190], HR 3.53, 95% CI: 1.76–7.10, p < 0.001), KMT2D (MRIM 6.3% [13/208], HR 2.43, 95% CI: 1.41–4.22, p = 0.002), and RB1 (MRIM 5.4% [13/242], HR 3.21, 95% CI: 1.62–6.36, p < 0.001) (Fig. 5c–h. Among the 8 genes, only TP53 and KRAS were differentially mutated between primary and metastatic samples with higher mutation rates in metastatic samples. We further performed survival analysis separating primary and metastatic samples. We found TP53 and KRAS mutation in primary sites but not metastatic sites, which could indicate a poorer prognosis (online suppl. Fig. S3a, Fig. S3b). Instead, in metastatic samples, prognostic differences between TP53/KRAS mutated patients and wild-type patients were not significant (online suppl. Fig. S3c, Fig. S3d). Thus, TP53 and KRAS mutation could differentiate the prognosis only in primary samples but not in metastases. We speculated that TP53 and KRAS mutation in primary samples might associate with metastasis and contribute to the poorer prognosis. We further investigated the prognostic effect of these gene mutations in another independent dataset [11]. We found mutations of TP53 (p = 0.007), RB1 (p < 0.001), and FAT1 (p < 0.001) also had significant unfavorable prognostic effects in the dataset (online suppl. Fig. S4), but other gene mutations were either not detected or had insignificant prognostic effects.

Fig. 5.

Gene mutations present in more than 5% of the metastases of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (PanNETs) with significant prognostic effects. Favorable prognostic effects of mutation of MEN1 (p = 0.007) (a) and DAXX (p = 0.010) (b), and unfavorable prognostic effects TP53 (p < 0.001) (c), KRAS (p = 0.001) (d), ATM (p = 0.032) (e), KMT2D (p = 0.001) (f), RB1 (p = 0.002) (g), and FAT1 (p < 0.001) (h) are shown. p values are derived from the log-rank test.

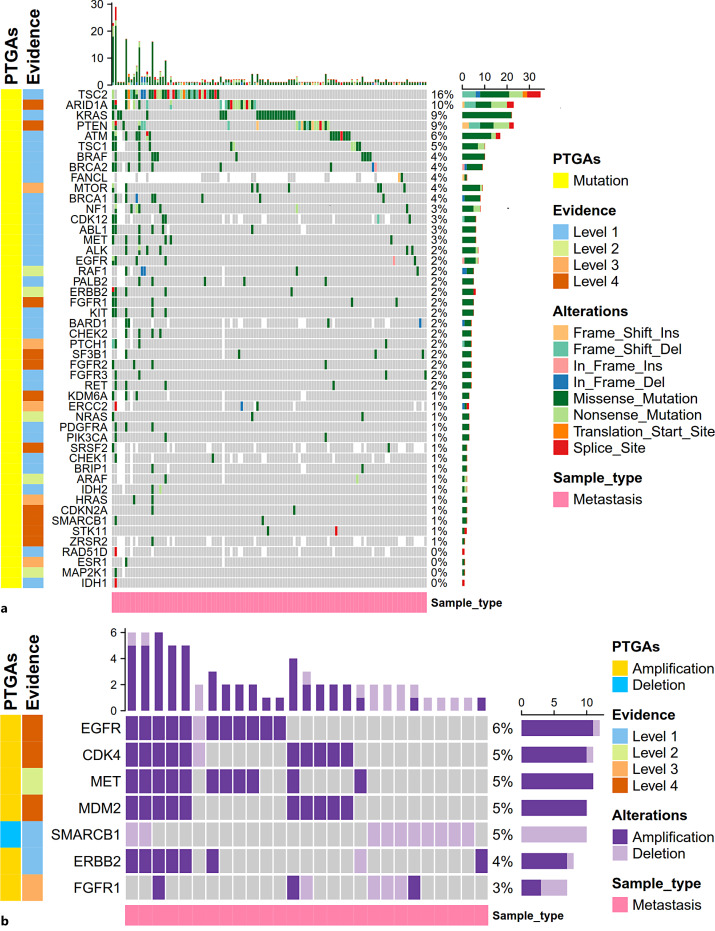

PTGAs with High Frequency Enriched in Metastatic Lesions

We interrogated the OncoKB to acquire the targetable gene alterations with preclinical or clinical evidence-based drugs in other malignancies. Here, we focused on the PTGAs that emerged in at least one metastatic lesion. Among the 56 targetable mutations annotated in OncoKB, 48 gene mutations were present in at least one metastatic sample. Among them, the most common potentially targetable mutation included TSC2 (15.5%, 34/219), ARID1A (9.7%, 21/216), KRAS (9.1%, 22/242), PTEN (8.7%, 21/242), ATM (6.4%, 15/235), TSC1 (4.6%, 10/219), and BRAF (4.1%, 10/242) (Fig. 6a; online suppl. Table S6). Multitargeted drugs covering the PTGAs found in metastases included Everolimus (targeting TSC1/2, MTOR mutation), tazemetostat (targeting ARID1A, KDM6A, SMARCB1 mutation), cobimetinib/trametinib (targeting KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, ARAF, RAF1, MAP2K1, NF1 mutation), olaparib (targeting ATM, BARD1, BRCA1/2, BRIP1, CDK12, CHEK1/2, FANCL, PALB2, RAD51D mutation), sunitinib/imatinib/ripretinib (targeting KIT, PDGFRA mutation), sorafenib (targeting KIT, ARAF mutation), rucaparib (targeting BRCA1/2, PALB2 mutation), Debio1347/infigratinib/erdafitinib/AZD4547 (targeting FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3 mutation), etc. (online suppl. Table S6). For targetable gene CNVs, all of the 6 targetable amplifications (EGFR, CDK4, MET, MDM2, ERBB2, FGFR1) and the one targetable deletion (SMARCB1) annotated in OncoKB were detected in at least one metastatic sample (Fig. 6b; online suppl. Table S6). Drugs covering these PTGAs included lapatinib (targeting EGFR/ERBB2 amplification), trastuzumab (targeting ERBB2 amplification), palbociclib/abemaciclib (targeting CDK4 amplification) crizotinib/capmatinib/tepotinib (targeting MET amplification), milademetan (targeting MDM2 amplification), Debio1347/infigratinib/erdafitinib (targeting FGFR1 amplification), tazemetostat (targeting SMARCB1 deletion), etc. (online suppl. Table S6). For 18 targetable gene fusions annotated in OncoKB, only FGFR3 intragenic gene fusion was detected in 1/201 metastatic samples. The corresponding drug targeting FGFR3 gene fusion was erdafitinib approved for bladder cancer (online suppl. Table S6).

Fig. 6.

Frequency and variation classification of potentially targetable gene alterations (PTGAs) annotated by OncoKB in the metastatic PanNET samples. Potentially targetable gene mutations (a), potentially targetable gene copy number variation (CNVs) including CNA and deletion (b). In total, 242 and 201 metastases were included for analysis of targetable gene mutations (a) and targetable CNVs (b), respectively. Genes not tested in the sample were filled with white blank. Variation frequency was calculated as the proportion of samples with a gene mutation (a) or CNV (b) among the total samples tested for the gene. Levels of evidence corresponding to the PTGAs were annotated based on the top level of evidence for the drug targeting the alteration documented in the OncoKB database.

Discussion

PanNETs frequently develop metastasis which was intractable for clinical management, especially for patients with multiple metastases. However, the molecular characteristics of metastases of PanNETs were not well-delineated in previous studies. To our knowledge, our study first comprehensively depicted the molecular difference between primary PanNETs and metastatic lesions based on both genomic and transcriptomic levels. Our study showed although primary PanNETs and metastases of PanNETs shared the same origins, metastases exhibited a certain extent of genomic and transcriptomic difference from primary PanNETs. This phenomenon might reflect the clone evolution and the plasticity of the tumors in response to temporal-spatial change along with the occurrence of metastasis [16–18]. At the genomic level, we found the mutations of TP53 and KRAS were significantly enriched in metastases compared with primary PanNETs. TP53 and KRAS mutations are two main genetic alterations enriched in gastroenteropancreatic NECs compared with G3 gastroenteropancreatic NETs [19]. However, we found no significant difference in the mutation rate of MEN1, ATRX, and DAXX between primary PanNETs and metastases, which represented the main genetic variation characterizing the well-differentiated PanNETs [10, 11]. This might indicate the biological behavior and treatment sensitivity of metastases of PanNETs with TP53 and KRAS mutation might be more similar to that of the poorly differentiated NECs. Besides, the genes involved in receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) and its downstream MAPK and mTOR signaling like IGF1R, KIT, DDR2, NF1, PTEN, and RAF1 are more frequently mutated in metastases than in primary PanNETs. Furthermore, we found the negative regulators of cell cycle progression, CDKN2A and CDKN2B, were more frequently deleted in metastases which is consistent with previous genomic research on PanNETs metastases (this study found CDKN2A deletion was present in 7.2% (25/347) of the primary PanNETs and 75% (15/20) of the metastases) [20]. Taken together, we concluded that the metastases of PanNETs mostly retained the characteristic genetic variations of the primary PanNETs but were more prone to develop subclones that evolved into more malignant entities with higher activity of proliferation. This hypothesis was further supported by the transcriptomic data which denoted that the pathways involved in cell proliferation (like E2F targets, G2M checkpoint, MYC targets, and mitotic spindle) were more enriched in metastases. Similarly, another transcriptomic study found metastatic panNETs had decreased somatostatin expression and increased Akt Signaling which further corroborated our hypothesis [21]. However, one interesting finding is the “KRAS signaling up” was more enriched in primary sites which conflicted with the higher mutation rates of KRAS in metastases. One possible explanation is that the KRAS signaling is also regulated by the CNV events since the rate of CNA of KRAS in primary PanNETs is significantly higher than that of metastases (9.0% vs. 3.5%, p = 0.027; online suppl. Table S4). Besides, we also noted that the primary PanNETs exhibited a pre-metastatic phenotype with enrichment of EMT and TGF-β signaling. This finding implicated that intervention with the EMT and TGF-β signaling might decrease the occurrence of metastasis in an early disease stage.

Among the genes frequently mutated in metastases that had significant prognostic effects, we identified that both MEN1 and DAXX mutations had significant favorable prognostic effects. This was consistent with the previous finding led by Jiao et al. [10] but conflicted with the studies led by Scarpa et al. [11], Chan et al. [22], and Roy et al. [20]. However, since the mutation rates of MEN1 and DAXX were not significantly different between primary PanNETs and metastases, the prognostic effects of these mutations also influenced the prognosis of the localized/regional PanNETs. In contrast, mutations of TP53 and KRAS that adversely influenced prognosis were significantly enriched in metastases. Thus, we speculated that TP53 and KRAS mutation might associate with metastasis and the higher mutation rates of TP53 and KRAS enriched in metastases contributed to the poorer prognosis of advanced PanNET patients compared with that of localized/regional PanNETs for the following reasons: (1) the mutation rates of TP53 and KRAS were both higher in metastatic samples than in primary samples (Fig. 2); (2) patients with TP53 mutation in primary samples are more likely to have metastatic samples than patients without TP53 mutation in primary samples (proportion of patients with metastatic samples in patients with TP53 mutation in primary samples vs. the proportion of patients with metastatic samples in patients without TP53 mutation in primary samples: 12.0% vs. 3.2%, p = 0.07); (3) PanNET patients with TP53 and KRAS mutation in primary samples had poorer prognosis (online suppl. Fig. S3a, Fig. S3b); (4) PanNET patients with metastatic samples have shorter OS than patients with only primary samples (online suppl. Fig. S5). Based on the findings above, we speculated that primary samples with TP53 and/or KRAS mutation are more prone to develop metastasis, and these patients would suffer from worse prognosis, and metastatic samples would have higher mutation rates of TP53 and KRAS than primary samples. Other gene mutations with more than 5% mutation rates in metastases that significantly adversely influenced prognosis included ATM, KMT2D, RB1, and FAT1. Mutation of TP53, RB1, and FAT1was validated in another dataset. These gene mutations might serve as predictors of prognosis and potential therapeutic targets for PanNETs. Since the samples in the validated dataset were all primary PanNETs and the sample size was limited and samples with these mutations were rare. Thus, more research is needed before translating these findings into clinical practice.

Our study showed the rationale for the application of mTOR inhibitors in advanced PanNETs since TSC2 (15.5%, 34/219), KRAS (9.1%, 22/242), PTEN (8.7%, 21/242), TSC1 (4.6%,10/219), IGF1R (4.5%,10/220), MTOR (3.7%, 8/219), the genes encoded the key negative regulators or the main oncogenic components of the mTOR pathway, were frequently mutated in metastases of PanNETs and might serve as the combinational genomic predictive biomarkers for selecting the patients who are more likely to benefit from mTOR inhibitors. Moreover, we found several gene alterations with targeted drugs having been approved or validated in other malignancies but not have been tested in PanNETs. Notably, we showed the potential of multitargeted drugs as promising novel treatment options which were represented by tazemetostat, cobimetinib/trametinib, olaparib, sunitinib, sorafenib, rucaparib, erdafitinib, lapatinib, etc. Evidence had shown multiple malignancies displayed epigenetic dysregulation caused by subunit variations of SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, such as alterations of ARID1A [23, 24], KDM6A [25, 26], SMARCA4 [24], and SMARCB1 [27], which are sensitive to EZH2 inhibition [23–27]. Tazemetostat is a selective EZH2 inhibitor that has been approved for the treatment of epithelioid sarcoma, a rare soft tissue sarcoma marked by SMARCB1 deficiency [28]. We saw 5.0% (10/201) and 9.7% (21/216) of the metastases harbored SMARCB1 deletion and ARID1A mutation respectively. Besides, 8 mutations of SMARCA4 (3.7%, 8/216), 3 mutations of KDM6A (1.4%, 3/208), and 2 mutations of SMARCB1 (0.8%, 2/242) were also found in the metastases. Furthermore, 5.5% (11/201) of the metastases showed EZH2 amplification. In sum, more than 22% (47/216) of the samples harbored tazemetostat-targeted variations considering both mutation and CNV (online suppl. Fig. S6). Biological evidence has shown that inhibition of EZH2 can reduce the cell viability and impair cell proliferation in vitro in PanNETs cell lines and patient-derived islet-like tumoroids and further reduce the tumor burden in vivo in Rip1TAG2 mice, thus representing a new therapeutic option for PanNENs [29]. However, to date, the attempt of the clinically available drug, tazemetostat, has not been conducted in PanNETs yet. Further investigations are needed to test the performance of tazemetostat in PanNETs. Previous genomic research had shown that DNA damage repair (DDR) was one of the main altered pathways in PanNETs suggesting the feasibility of selectively targeting this pathway in PanNETs [11, 30]. We showed that 6.4% (15/235) and 6.5% (13/200) of the metastases harbored ATM mutation and ATM deletion, respectively, and 4.0% (8/200) and 5.5% (11/201) of the metastases carried CHEK1 and CHEK2 deletion respectively. Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) is the chromatin-associated enzyme involved in the repair of DNA single-strand breaks mediated via the base excision repair pathway [31]. Inhibition of PARP has been shown to potentiate temozolomide cytotoxicity and reverse drug resistance in multiple cancer cell types [32–35]. However, olaparib, the representative PARP inhibitor targeting the DDR pathway [31], has not been tested in PanNETs. Besides, drugs targeting the amplification of MET, CDK4, and MDM2 are also deserved to be attempted since a certain fraction of metastases carried these alterations. So far, sunitinib and sulfatinib are the only two TKIs have been approved for the treatment of advanced PanNETs [36, 37]. However, our study identified multiple targeted drugs with potential effectiveness but not validated in PanNETs. The high fraction of PTGAs in metastases of PanNETs indicated the promising prospect for targeted therapy in advanced PanNETs and underlined the importance of molecular testing for biomarker-directed better-personalized treatment.

A critical issue was that we showed inconsistent mutation rate of TP53 compared with previous genomic studies in PanNETs [10, 11]. We thought there might be some possible causes. (1) The sample type: the previous studies included only primary panNETs, whereas the metastatic samples included in this study account for nearly half of the total samples. Our study found TP53 mutation was more highly enriched in metastases of PanNETs than in primary samples (primary vs. metastases: 10.3% vs. 16.9%, p = 0.035). Thus, TP53 mutation rate in our study would be higher than previous reports. (2) The sample grades: previous genomic studies have shown the NET G3 have higher frequency of TP53 mutation (14%) [19]. Thus, TP53 mutation might be correlated with the sample grade. However, we could not acquire the grading information of the samples, but the sample heterogeneity between different studies could explain the difference of TP53 mutation rates.

Although our study included a large cohort, the analysis was retrospective. Besides, the beginning time of OS was defined as the time point at the sequencing report due to the unavailability of the specific time point at diagnosis which might lead to bias to a certain extent. Moreover, the specific anatomic sites of the metastases and the grading were unknown since such information was not documented in the datasets analyzed in this study. Further basic studies and prospective clinical trials were needed.

In summary, our study revealed the genomic and transcriptomic heterogeneity between primary PanNETs and the metastases. Metastases of PanNETs presented more enrichment of pathways involved in cell proliferation and metabolism, whereas primary PanNETs exhibited the pre-metastatic phenotype with enrichment of EMT and TGF-β signaling. TP53 and KRAS mutation in primary samples might associate with metastasis and contribute to a poorer prognosis. Targeted therapy holds great prospects for alleviating the therapeutic dilemmas of advanced PanNETs due to the high fraction of novel targetable alterations in metastases which deserves to be attempted for advanced PanNETs in clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

We thank the database curators, data providers, and the subjects who participated in the study. All the datasets used in this study can be downloaded from the corresponding database provided in the main context.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval and consent were not required as this study was based on publicly available data.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2019YFB1309704).

Author Contributions

Huangying Tan and Yiying Guo contributed to the conception and design of the study. Yiying Guo performed data collection and curation, analyzed and interpreted the genomic and transcriptomic data, and drafted the manuscript. Chao Tian, Zixuan Cheng, Ruao Chen, Yuangliang Li, Fei Su, and Yanfen Shi contributed to the review and proofreading of the manuscript. Huangying Tan reviewed and edited the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant number 2019YFB1309704).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the [GENIE], [cBioportal], and [GEO]: https://doi.org/10.7303/syn26706564, http://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=panet_arcnet_2017,https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE73338,https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE73339. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Rindi G, Klimstra DS, Abedi-Ardekani B, Asa SL, Bosman FT, Brambilla E, et al. A common classification framework for neuroendocrine neoplasms: an International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) expert consensus proposal. Mod Pathol. 2018 Dec;31(12):1770–86. 10.1038/s41379-018-0110-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dasari A, Shen C, Halperin D, Zhao B, Zhou S, Xu Y, et al. Trends in the incidence, prevalence, and survival outcomes in patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the United States. JAMA Oncol. 2017 Oct 1;3(10):1335–42. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sonbol MBMG, Mazza GL, Starr JS, Hobday TJ, Halfdanarson TR. Incidence and survival patterns of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors over the last two decades: a SEER database analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(4_suppl):629. 10.1200/jco.2020.38.4_suppl.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Das S, Dasari A. Epidemiology, incidence, and prevalence of neuroendocrine neoplasms: are there global differences? Curr Oncol Rep. 2021 Mar 14;23(4):43. 10.1007/s11912-021-01029-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, Dagohoy C, Leary C, Mares JE, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Jun 20;26(18):3063–72. 10.1200/jco.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Strosberg JR, Cheema A, Weber JM, Ghayouri M, Han G, Hodul PJ, et al. Relapse-free survival in patients with nonmetastatic, surgically resected pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: an analysis of the AJCC and ENETS staging classifications. Ann Surg. 2012 Aug;256(2):321–5. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824e6108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dieckhoff P, Runkel H, Daniel H, Wiese D, Koenig A, Fendrich V, et al. Well-differentiated neuroendocrine neoplasia: relapse-free survival and predictors of recurrence after curative intended resections. Digestion. 2014;90(2):89–97. 10.1159/000365143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li YL, Cheng ZX, Yu FH, Tian C, Tan HY. Advances in medical treatment for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. World J Gastroenterol. 2022 May 28;28(20):2163–75. 10.3748/wjg.v28.i20.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018 Feb;15(2):81–94. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jiao Y, Shi C, Edil BH, de Wilde RF, Klimstra DS, Maitra A, et al. DAXX/ATRX, MEN1, and mTOR pathway genes are frequently altered in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Science. 2011 Mar 4;331(6021):1199–203. 10.1126/science.1200609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scarpa A, Chang DK, Nones K, Corbo V, Patch AM, Bailey P, et al. Whole-genome landscape of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Nature. 2017 Mar 2;543(7643):65–71. 10.1038/nature21063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Missiaglia E, Dalai I, Barbi S, Beghelli S, Falconi M, della Peruta M, et al. Pancreatic endocrine tumors: expression profiling evidences a role for AKT-mTOR pathway. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Jan 10;28(2):245–55. 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. American Association of Cancer Research (AACR) . Project genomics, evidence, Neoplasia, information, Exchange (GENIE) database. Version 11.1. syn26706564. Available from: 10.7303/syn26706564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scarpa A, Chang DK, Nones K, Corbo V, Patch AM, Bailey P, et al. Corrigendum: whole-genome landscape of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Nature. 2017;550(7677):548. 10.1038/nature24026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sadanandam A, Wullschleger S, Lyssiotis CA, Grötzinger C, Barbi S, Bersani S, et al. A cross-species analysis in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors reveals molecular subtypes with distinctive clinical, metastatic, developmental, and metabolic characteristics 2015. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE73339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bakir B, Chiarella AM, Pitarresi JR, Rustgi AK. EMT, MET, plasticity, and tumor metastasis. Trends Cell Biol. 2020 Oct;30(10):764–76. 10.1016/j.tcb.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chaffer CL, San Juan BP, Lim E, Weinberg RA. EMT, cell plasticity and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016 Dec;35(4):645–54. 10.1007/s10555-016-9648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Turajlic S, Sottoriva A, Graham T, Swanton C. Resolving genetic heterogeneity in cancer. Nat Rev Genet. 2019 Jul;20(7):404–16. 10.1038/s41576-019-0114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Venizelos A, Elvebakken H, Perren A, Nikolaienko O, Deng W, Lothe IMB, et al. The molecular characteristics of high-grade gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2021 Nov 11;29(1):1–14. 10.1530/ERC-21-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roy S, LaFramboise WA, Liu TC, Cao D, Luvison A, Miller C, et al. Loss of chromatin-remodeling proteins and/or CDKN2A associates with metastasis of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and reduced patient survival times. Gastroenterology. 2018 Jun;154(8):2060–3.e8. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.02.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tran CG, Scott AT, Li G, Sherman SK, Ear PH, Howe JR. Metastatic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors have decreased somatostatin expression and increased Akt signaling. Surgery. 2021 Jan;169(1):155–61. 10.1016/j.surg.2020.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chan CS, Laddha SV, Lewis PW, Koletsky MS, Robzyk K, Da Silva E, et al. ATRX, DAXX or MEN1 mutant pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors are a distinct alpha-cell signature subgroup. Nat Commun. 2018 Oct 12;9(1):4158. 10.1038/s41467-018-06498-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bitler BG, Aird KM, Garipov A, Li H, Amatangelo M, Kossenkov AV, et al. Synthetic lethality by targeting EZH2 methyltransferase activity in ARID1A-mutated cancers. Nat Med. 2015 Mar;21(3):231–8. 10.1038/nm.3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Januario T, Ye X, Bainer R, Alicke B, Smith T, Haley B, et al. PRC2-mediated repression of SMARCA2 predicts EZH2 inhibitor activity in SWI/SNF mutant tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Nov 14;114(46):12249–54. 10.1073/pnas.1703966114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ler LD, Ghosh S, Chai X, Thike AA, Heng HL, Siew EY, et al. Loss of tumor suppressor KDM6A amplifies PRC2-regulated transcriptional repression in bladder cancer and can be targeted through inhibition of EZH2. Sci Transl Med. 2017 Feb 22;9(378):eaai8312. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aai8312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ezponda T, Dupéré-Richer D, Will CM, Small EC, Varghese N, Patel T, et al. UTX/KDM6A loss enhances the malignant phenotype of multiple myeloma and sensitizes cells to EZH2 inhibition. Cell Rep. 2017 Oct 17;21(3):628–40. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gounder M, Schöffski P, Jones RL, Agulnik M, Cote GM, Villalobos VM, et al. Tazemetostat in advanced epithelioid sarcoma with loss of INI1/SMARCB1: an international, open-label, phase 2 basket study. Lancet Oncol. 2020 Nov;21(11):1423–32. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30451-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Simeone N, Frezza AM, Zaffaroni N, Stacchiotti S. Tazemetostat for advanced epithelioid sarcoma: current status and future perspectives. Future Oncol. 2021 Apr;17(10):1253–63. 10.2217/fon-2020-0781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. April-Monn SL, Andreasi V, Schiavo Lena M, Sadowski MC, Kim-Fuchs C, Buri MC, et al. EZH2 inhibition as new epigenetic treatment option for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNENs). Cancers. 2021 Oct 7;13(19):5014. 10.3390/cancers13195014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu IH, Ford JM, Kunz PL. DNA-repair defects in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors and potential clinical applications. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016 Mar;44:1–9. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bochum S, Berger S, Martens UM. Olaparib. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2018;211:217–33. 10.1007/978-3-319-91442-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tentori L, Leonetti C, Scarsella M, D’Amati G, Vergati M, Portarena I, et al. Systemic administration of GPI 15427, a novel poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitor, increases the antitumor activity of temozolomide against intracranial melanoma, glioma, lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2003 Nov 1;9(14):5370–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Higuchi F, Nagashima H, Ning J, Koerner MVA, Wakimoto H, Cahill DP. Restoration of temozolomide sensitivity by PARP inhibitors in mismatch repair deficient glioblastoma is independent of base excision repair. Clin Cancer Res. 2020 Apr 1;26(7):1690–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Curtin NJ, Wang LZ, Yiakouvaki A, Kyle S, Arris CA, Canan-Koch S, et al. Novel poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitor, AG14361, restores sensitivity to temozolomide in mismatch repair-deficient cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2004 Feb 1;10(3):881–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Delaney CA, Wang LZ, Kyle S, White AW, Calvert AH, Curtin NJ, et al. Potentiation of temozolomide and topotecan growth inhibition and cytotoxicity by novel poly(adenosine diphosphoribose) polymerase inhibitors in a panel of human tumor cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 2000 Jul;6(7):2860–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pavel M, O’Toole D, Costa F, Capdevila J, Gross D, Kianmanesh R, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines update for the management of distant metastatic disease of intestinal, pancreatic, bronchial neuroendocrine neoplasms (NEN) and NEN of unknown primary site. Neuroendocrinology. 2016;103(2):172–85. 10.1159/000443167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Das S, Dasari A. Novel therapeutics for patients with well-differentiated gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2021;13:17588359211018047. 10.1177/17588359211018047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during the current study are publicly available in the [GENIE], [cBioportal], and [GEO]: https://doi.org/10.7303/syn26706564, http://www.cbioportal.org/study/summary?id=panet_arcnet_2017,https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE73338,https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE73339. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.