Abstract

Background:

Several lysosomal genes are associated with Parkinson’s disease (PD), yet the association between PD and ARSA remains unclear.

Objectives:

To study rare ARSA variants in PD.

Methods:

To study rare ARSA variants (minor allele frequency<0.01) in PD, we performed burden analyses in six independent cohorts with a total of 5,801 PD patients and 20,475 controls, followed by a meta-analysis.

Results:

We found evidence for associations between functional ARSA variants and PD in four cohorts (P≤0.05 in each) and in the meta-analysis (P=0.042). We also found an association between loss-of-function variants and PD in the UKBB cohort (P=0.005) and in the meta-analysis (P=0.049). These results should be interpreted with caution as no association survived multiple comparisons correction. Additionally, we describe two families with potential co-segregation of ARSA p.E384K and PD.

Conclusions:

Rare functional and loss-of-function ARSA variants may be associated with PD. Further replications in large case-control/familial cohorts are required.

Keywords: Lysosomal genes, Parkinson’s disease, ARSA, rare variants

Introduction

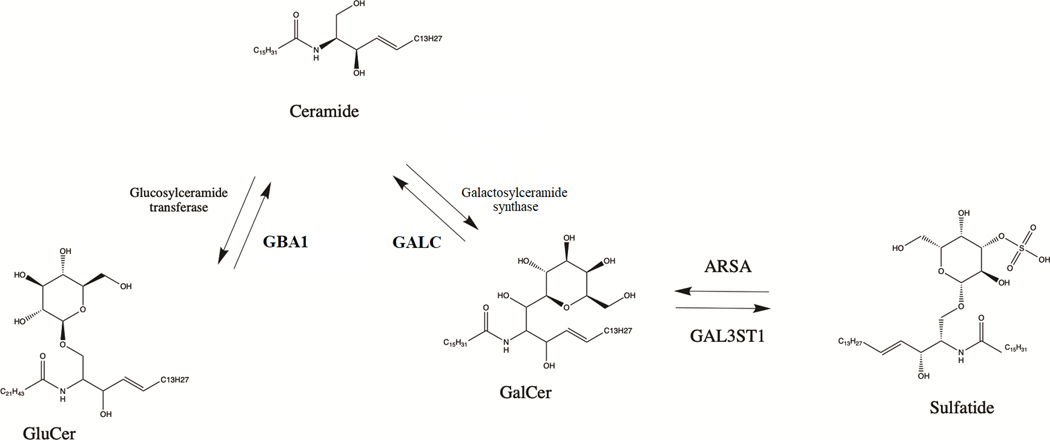

Lysosomal genes play a prominent role in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease (PD).1 Variants in GBA1 are amongst the most important risk factors of PD,2 and mutations in other lysosomal storage disorder genes have also been associated with PD (e.g. ASAH1, GALC, SMPD1).3–7 Homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in ARSA may lead to the autosomal recessive lysosomal storage disorder metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD).8 The ARSA gene, located on chromosome 22q13.33, encodes arylsulfatase A, which hydrolyzes sulfatides to galactosylceramide and sulfate8 (Figure 1). Consequently, hydrolysis of galactosylceramide occurs by the lysosomal enzyme galactosylceramidase, encoded by GALC, which is nominated as a PD gene by genome-wide association studies and targeted analyses.6, 7, 9

Figure 1.

The role of ARSA and GBA1 in sphingolipid metabolism. GluCer- glucosylceramide; GalCer- galactosyleramide; ARSA- arylsulfatase A; GALC- galactosylceramidase; GBA1- galactosylceramidase

The genetic association between ARSA variants and PD remains controversial.10–14 Co-segregation of pathogenic ARSA variant was reported in one family with two PD patients, and two studies suggested potential association between rare ARSA loss-of-function variants and PD.10, 12 In the current study, we aimed to evaluate the association between rare ARSA variants and PD in six cohorts of 5,801 PD patients and 20,475 controls and in two families with MLD and PD.

Methods

Population

The study population included a total of 5,801 PD patients, including 759 patients with early onset PD (EOPD <50 years old) and 20,475 controls from six cohorts (detailed in Supplementary Table 1). Four cohorts have been collected and sequenced at McGill University: McGill (Quebec, Canada and Montpellier, France)15, Columbia University (the SPOT study, New York, NY)16, Sheba Medical Center (Israel) and Pavlov First State Medical university and Institute of Human Brain (Pavlov and Human Brain cohort; Saint-Petersburg, Russia). Additionally, we analyzed data from the UK Biobank (UKBB) and Accelerating Medicines Partnership – Parkinson Disease (AMP-PD) initiatives.The McGill university cohort was recruited in Québec, Canada (partially through the Quebec Parkinson Network, QPN)15 and in France. The Columbia cohort was collected in NY and is of mixed ancestry (European, Ashkenazi Jews [AJ] and a minority of Hispanics and Blacks, described in detail previously)16. The Sheba cohort, recruited in Israel, includes only participants with full AJ ancestry (by report). Pavlov and Human Brain cohort, recruited in Russia, consist predominantly of patients of European ancestry. All PD patients in these cohorts were diagnosed by movement disorder specialists according to the UK brain bank criteria17 or the MDS clinical diagnostic criteria.18

We contacted 21 families with MLD (homozygous or compound heterozygous carriers of pathogenic ARSA variants) or their representatives through Russian Society of Rare (Orphan) Diseases and sent them out questionnaire to detect family history of PD. The description of this analysis and results are presented in the Supplementary Appendix in detail.

All participants signed informed consent forms before entering the studies and study protocols were approved by the institutional review boards.

Targeted next generation sequencing

The ARSA gene was sequenced in the four cohorts collected at McGill University with targeted next generation sequencing by molecular inversion probes (MIPs) as previously described.19 All MIPs that were used to sequence ARSA are provided (Supplementary Table 2) and the full protocol is available at https://github.com/gan-orlab/MIP_protocol. The library was sequenced using Illumina NovaSeq 6000 SP PE100 platform at the Genome Quebec Innovation Centre. Alignment was performed with Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (hg19)20 and Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, v3.8) was used for post-alignment quality control and variant calling.21 We performed quality control by filtering out variants and samples with reduced quality, using the PLINK software v1.9.22 SNPs were excluded from analysis if missingness was more than 10%. Variants with a minor allele frequency (MAF) less than 1% and with a minimum quality score (GQ) of 30 were included in the analyses and analyzed at minimal depths of coverage 30x.

Data quality control and analysis in AMP-PD and UKBB

Quality control procedures of whole genome sequencing for AMP-PD cohorts were performed on individual and variant levels as described by AMP-PD (https://amp-pd.org/whole-genome-data and detailed elsewhere).23 Quality control of UKBB whole exome sequencing data was performed using Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK, v3.8). In this analysis we used previously suggested filtration parameters for whole exome sequencing data with minimum depth of coverage 10x and GQ 20.24 Additionally, all multi-allelic sites were removed from the dataset during the quality control process.

Alignment of AMP-PD and UKBB data was performed using the human reference genome (hg38) and coordinates for the ARSA gene extraction were chr22:50,622,754–50,628,152. We performed additional filtration procedures using the UKBB and AMP-PD cohorts to exclude non-European individuals (UKB field 21000) and filtered by relatedness to remove any first and second-degree relatives. Only participants of European ancestry have been included in the analysis from UKBB and AMP-PD cohorts.

Annotations and statistical analysis

To functionally annotate genetic variants in all cohorts, we utilized ANNOVAR.25 Data on variant pathogenicity were predicted using Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) score and Varsome.26, 27 To analyze rare variants (MAF<0.01), an optimized sequence Kernel association test (SKAT-O, R package) and Collapsing and combine rare variants-Wald test (CMC-Wald, rvtest package), were performed.28, 29 We separately analyzed the burden of all rare, nonsynonymous and functional variants (nonsynonymous, stop/frameshift and splicing) and loss-of-function variants. Lastly, we analyzed variants with a Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion (CADD) score of ≥ 20, representing the top 1% of potentially deleterious variants. For each of the analyses, we performed a meta-analysis between the cohorts using metaSKAT package,30 adjusting for sex, age and ethnicity. We applied false discovery rate (FDR) correction to all p-values and in the results, we use ‘Pfdr’ to denote P-values with FDR correction and ‘P’ to denote P-values without FDR. All the code used in the current study is available at https://github.com/gan-orlab/ARSA.

In silico structural analysis

The atomic coordinates of the human Aryl sulfatase A were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank (PDB 1AUK). The analysis and figures were performed using PyMol v.2.4.0.

Results

Rare functional and loss-of-function ARSA variants are associated with Parkinson’s disease

The average coverage across all four cohorts sequenced at McGill was >714X with >98% of the nucleotides covered at >30x (detailed in Supplementary Table 3). We identified a total of 96 rare variants across all cohorts sequenced at McGill (Supplementary Table 4) and 113 rare variants in AMP-PD and UKBB cohorts (Supplementary Table 5). We identified a total of 92 nonsynonymous variants, among which ten were observed in multiple cohorts. Additionally, we found seven loss-of-function variants, all detailed in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6. In the UKBB cohort, we identified a pathogenic splicing variant c.465+1G>A that was nominally associated with PD in this specific cohort (OR=4.03, 95%CI=1.62–10.02; p=0.004). However, this variant was also found in two controls in the AMP-PD cohort and was absent in the other cohorts we analyzed. Therefore, it cannot be concluded if this specific variant is pathogenic for PD. Across all the cohorts we analyzed, we identified three individuals who carried more than one rare (MAF<1%) ARSA nonsynonymous or loss-of-function variants (Supplementary Table 6). In all three, the variants were in close proximity and were confirmed to be in cis. We did not find any other specific variants that were significantly associated with PD.

Burden analyses, using SKAT-O, demonstrated an association of functional variants with PD in four out of six cohorts (McGill, P=0.023, Columbia, P=0.037, Pavlov, P=0.022 and UKBB, P=0.009) and in the meta-analysis (P=0.042; Table 1; Supplementary Table 7). We also found an association between rare loss-of-function variants in the UKBB cohort (P=0.005) and in the meta-analysis (P=0.049). However, these results should be interpreted with caution as only a few loss-of-function variant were reported and none of the associations survived FDR correction (Supplementary Table 4-5, 7).

Table 1.

Burden analysis of rare ARSA variants

| Cohort | N cases | N controls | All rare variants, P | All non-synonymous variants, P | Functional variants, P | Loss of function, P | CADD > 20, P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Columbia cohort | 917 | 486 | 0.005 | 0.060 | 0.037 | 0.313 | 0.009 |

| Sheba cohort | 683 | 553 | 0.195 | 0.745 | 0.095 | - | 0.664 |

| McGill cohort | 761 | 549 | 0.011 | 0.032 | 0.023 | - | 0.081 |

| Pavlov and Human brain cohort | 497 | 401 | 0.019 | 0.106 | 0.022 | 0.467 | 0.082 |

| UKBB | 602 | 15,000 | 0.009 | 0.686 | 0.009 | 0.005 | 0.539 |

| AMP-PD | 2,341 | 3,486 | 0.820 | 0.673 | 0.602 | 0.107 | 0.705 |

| Meta-analysis of all cohorts | 5,801 | 20,475 | 0.826 | 0.420 | 0.042 | 0.049 | 0.431 |

N, number; P, p value; UKBB, UK biobank; AMP-PD, Accelerating Medicines Partnership – Parkinson Disease; CADD, Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion score.

p-value presented without FDR adjustment, as no p-values survived after correction.

We found associations between all rare variants and PD in the McGill cohort (P=0.011), Columbia cohort (P=0.005), Pavlov and Human brain institute (P=0.019) and in the UKBB cohort (P=0.009). However, there was no association in the meta-analysis (Table 1; Supplementary Table 4). Variants with CADD scores ≥20 were associated with PD in the Columbia cohort (P=0.009), whereas no association was found in the other cohorts and in the meta-analysis. Similarly, all rare nonsynonymous variants in ARSA were associated with PD in the McGill cohort (P=0.032) but not in the other cohorts Using CMC-Wald test, we observed that rare ARSA variants were overrepresented in PD cases among four out of six of our cohorts, including McGill, Pavlov and Human Brain, Sheba, and UKBB cohorts (Supplementary Table 8). We did not find any meaningful association between rare ARSA variants and EOPD in the meta-analyses (Supplementary Table 9).

We did not find the p.L300S ARSA variant, which was previously reported as pathogenic in PD,31 yet we found the likely pathogenic (based on Varsome annotation) p.L300V variant in two cases and one control in our analysis. We found potential co-segregation of p.E382K variant in two PD patients from two separate families with history of MLD and PD. However, one of the patients, II-4 from the first family, was also a carrier of the GBA1 variant RecNcil (Supplementary Figure 1A), further complicating our ability to estimate the role of the ARSA variant in PD. We did not find p.E382K in any of the cohorts we analyzed. In silico structural analysis demonstrated a disruptive effect of p.E382K variant on ARSA (Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Appendix). A Detailed description of the familial and structural analyses is provided in the Supplementary Appendix.

Discussion

In the current study, we report a possible association between rare functional and loss-of-function ARSA variants and PD. In four of our cohorts, we also identified a possible association between all rare and nonsynonymous variants and PD. The negative results previously reported for rare ARSA variants in PD could be attributed to sample size or ethnicity (Supplementary Table 10).12–14 Although the associations described in the present study do not survive correction for multiple comparisons, the fact that there were many nominal associations in independent cohorts may suggest that these associations are real.

A recent large scale burden analysis found an association between rare ARSA loss-of-function variants and PD.10 This study included data from AMP-PD and UKBB that were also used in our analysis. However, our study included four independent cohorts with no overlapping samples comprising a total of 2,858 cases and 1,989 controls, and we demonstrated an association of rare ARSA variants with PD in three out for four of our cohorts. While a study from China did not find a statistically significant burden of rare ARSA variants in PD,12 they reported higher prevalence of loss-of-function variants in late-onset PD (0.25% in PD vs 0% in controls),12 which is in line with our results. However, our results should be interpreted with caution as none of our associations survived FDR correction and we only discovered a few carriers of private loss-of-function variants across all six cohorts. A recent study from Japan suggested that the ARSA p.L300S mutation was likely pathogenic in PD due to co-segregation within a family with two PD patients.31 We did not find this specific variant in our study. However, we identified several variants that could potentially be associated with PD. These include the canonical splicing loss-of function variant c.465+1G>A, as well as a rare pathogenic variant p.E382K that showed potential segregation in two families. The structure of ARSA would be disrupted by the p.E382K mutation, as it would likely destabilize the octameric enzyme according to our structural analysis (Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Appendix). The role of these variants in PD should be further examined in genetic and functional studies.

The enzyme encoded by ARSA, arylsulfatase A, has an important role in the lysosomal ceramide metabolism pathway. Galactosylceramide is hydrolyzed from sulfatides by arylsulfatase A, which is then further hydrolyzed to ceramide by galactosylceramidase,32 encoded by the putative PD gene GALC.7 Another PD gene, GBA1,1, 33 also plays an important role in ceramide metabolism, by hydrolyzing glucosylceramide to ceramide (Figure 1). ARSA is also important for myelin metabolism.34 Several studies suggested a link between ARSA and alpha-synuclein accumulation. Accumulation of α-synuclein was found in glial cells and microglia of MLD patients..35 In ARSA knockout cells, the authors reported an increase in alpha-synuclein accumulation, secretion and propagation.11 These findings suggest a potential association between pathogenic ARSA variants and α-synuclein accumulation. The activity of ARSA was reported to be low in the subset of patients with parkinsonism.36 Moreover, plasma ARSA levels was reported to be higher in early PD as compared to controls or late PD, suggesting a possible compensatory mechanism.37 Reduced level of sulfatides, substrate of ARSA, was reported in frontal cortex of PD patients.38 Therefore, there is biochemical, functional, and genetic evidence for the involvement of ARSA in neurodegeneration and potentially PD, further emphasizing the importance of the lysosomal ceramide metabolism pathway in PD (Figure 1). The link between ARSA and PD is not as strong as between GBA1 and PD and only evident in large scale burden analysis (Supplementary Table 10). Potentially, it could be due to rarity of ARSA variants that associated with PD and could depend on the ethnicity.

Our study has several limitations. In some of our cohorts, patients and controls were not matched for sex and age, which was therefore adjusted in the statistical analysis. Different quality control procedures were used for targeted sequencing, whole-exome sequencing, and whole-genome sequencing data, utilizing varying thresholds for depth of coverage and quality assessment as recommended for the different platforms. Notably, lower depths of coverage and GQ scores were utilized in the UKBB dataset due to methodological differences in whole exome sequencing compared to the other sequencing methods. This could potentially lead to discrepancy in enrichment in variants between different cohorts. Another limitation of our study is the inclusion of mainly individuals of European ancestry. In addition, an inherent feature of kernel analyses is that it is impossible to determine the direction of the association, since both disease risk and protective variants are included at the same time. Nevertheless, SKAT-O is preferred over individual variant analysis and other burden analysis in rare variant association studies because it addresses the low statistical power and mitigates risk of spurious associations resulting from the low frequency of individual rare variants, and it allows for a combined analysis of both risk and protective variants. Lastly, in our analysis, we did not perform adjustment for principal components, as we did not have genome-wide or whole-genome sequencing data for all cohorts.

To conclude, rare functional and loss of function ARSA variants may be associated with PD, yet the results here cannot be considered as conclusive. Further replications in other cohorts are required to confirm our findings along with additional functional studies to understand the potential mechanism.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1 Study population

Supplementary Table 2 Detailed information on the ARSA molecular inversion probes

Supplementary Table 3 Coverage details for ARSA

Supplementary Table 4 Rare ARSA variants for cohorts sequenced at McGill

Supplementary Table 5 Rare ARSA variants for UKBB and AMP-PD cohorts

Supplementary Table 6 PD patients carrying multiple rare ARSA mutations.

Supplementary Table 7 Kernel analysis of ARSA in full cohort

Supplementary Table 8 Burden analysis of ARSA using CMC-Wald test

Supplementary Table 9 Kernel analysis of ARSA among early onset PD patients (<50 years old)

Supplementary Table 10 Previous rare variants analysis of ARSA in PD

Supplementary Figure 1. Family trees of two families with Metachromatic leukodystrophy and Parkinson’s disease in history. Square – male; circle – female; open symbol – healthy; grey– Parkinson’s disease; filled black symbol – Metachromatic leukodystrophy; PD – Parkinson’s disease; MLD – Metachromatic leukodystrophy; crossed line – deceased subject; wt – wild-type.

(A) Octameric assembly of the human ARSA (pdb 1AUK). Glu382 side-chains are labeled as yellow spheres. (B) Close up of the interface between two chains (A and B) where Glu382 is located. The mutation p.E382K would disrupt an intrachain hydrogen bond between the side-chain carboxyl of Glu382 and the main chain amide of Phe472. The backbone carbonyl oxygen of Glu382 also interacts with the side-chain of Lys457.

Acknowledgement:

We would like to thank the participants in the different cohorts for contributing to this study. This research used the NeuroHub infrastructure and was undertaken thanks in part to funding from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, awarded through the Healthy Brains, Healthy Lives initiative at McGill University, Calcul Québec and Compute Canada. UK Biobank Resources were accessed under application number 45551. The UKBB cohort was accessed using Neurohub (https://www.mcgill.ca/hbhl/neurohub). The Accelerating Medicines Partnership – Parkinson Disease (AMP-PD, 2.5 release) initiative cohorts were accessed using the Terra platform (https://amp-pd.org/). Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the AMP PD Knowledge Platform. For up-to-date information on the study, visit https://www.amp-pd.org. AMP PD – a public-private partnership – is managed by the FNIH and funded by Celgene, GSK, the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research, the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Verily. Genetic data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Fox Investigation for New Discovery of Biomarkers (BioFIND), the Harvard Biomarker Study (HBS), the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI), the Parkinson’s Disease Biomarkers Program (PDBP), the International LBD Genomics Consortium (iLBDGC), and the STEADY-PD III Investigators. BioFIND is sponsored by The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (MJFF) with support from the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). The BioFIND Investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. For up-to-date information on the study, visit michaeljfox.org/news/biofind. The HBS is a collaboration of HBS investigators [full list of HBS investigator found at https://www.bwhparkinsoncenter.org/biobank/ and funded through philanthropy and NIH and Non-NIH funding sources. The HBS Investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. PPMI – a public-private partnership – is funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and funding partners, including [list the full names of all of the PPMI funding partners found at www.ppmi-info.org/fundingpartners]. The PPMI Investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. For up-to-date information on the study, visit www.ppmi-info.org. PDBP consortium is supported by the NINDS at the National Institutes of Health. A full list of PDBP investigators can be found at https://pdbp.ninds.nih.gov/policy. The PDBP investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. Genome Sequencing in Lewy Body Dementia and Neurologically Healthy Controls: A Resource for the Research Community.” was generated by the iLBDGC, under the co-directorship by Dr. Bryan J. Traynor and Dr. Sonja W. Scholz from the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. The iLBDGC Investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. For a complete list of contributors, please see: bioRxiv 2020.07.06.185066; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.06.185066. STEADY‐PD III is a 36‐month, Phase 3, parallel group, placebo‐controlled study of the efficacy of isradipine 10 mg daily in 336 participants with early Parkinson’s Disease that was funded by the NINDS and supported by The Michael J Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research and the Parkinson’s Study Group. The STEADY-PD III Investigators have not participated in reviewing the data analysis or content of the manuscript. The full list of STEADY PD III investigators can be found at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02168842. Pavlov and Human Brain cohort is supported by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (Project No 123030200067–6). We would like to thank All-Russian Society of Rare (Orphan) Diseases for providing assistance and information. ZGO is supported by the Fonds de recherche du Québec - Santé (FRQS) Chercheurs-boursiers award, in collaboration with Parkinson Quebec, and is a William Dawson Scholar. The access to part of the participants for this research has been made possible thanks to the Quebec Parkinson’s Network (http://rpq-qpn.ca/en/). KS is supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF), awarded to McGill University for the Healthy Brains for Healthy Lives initiative (HBHL) and FRQS post-doctoral fellowship.

Funding

This study was financially supported by grants from the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA), the Canada First Research Excellence Fund (CFREF), awarded to McGill University for the Healthy Brains for Healthy Lives initiative (HBHL), and Parkinson Canada. The Columbia University cohort is supported by the Parkinson’s Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (K02NS080915 and UL1 TR000040) and the Brookdale Foundation.

Financial Disclosures of all authors (for the preceding 12 months)

RNA research is funded by the Michael J. Fox Foundation, the Silverstein Foundation and the Parkinson’s Foundation. He received consultation fees from Gain Therapeutics, Takeda and Genzyme/Sanofi. ZGO received consultancy fees from Lysosomal Therapeutics Inc. (LTI), Idorsia, Prevail Therapeutics, Inceptions Sciences (now Ventus), Ono Therapeutics, Bial Biotech, Bial, Handl Therapeutics, UCB, Capsida, Denali Lighthouse, Guidepoint and Deerfield. Other authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

Authors’ Roles

1. Research project: A. Conception, B. Organization, C. Execution

2. Statistical Analysis: A. Design, B. Execution, C. Review and critique

3. Manuscript Preparation: A. Writing of the first draft, B. Review and critique

KS: 1A, 1B, 1C, 2A, 2B, 3A

MB: 1C, 2B, 3B

AD: 1C, 2B, 2C, 3A

EY: 1C, 2C, 3B

JA: 1C, 2C, 3B

JAR: 1C, 2C, 3B

FA: 1C, 2C, 3B

DS: 1C, 2C, 3B

SF: 1C, 2C, 3B

CW: 1C, 2C, 3B

OM: 1C, 2C, 3B

YD: 1C, 2C, 3B

ND: 1C, 2C, 3B

LG: 1C, 2C, 3B

SHB: 1C, 2C, 3B

IN: 1C, 2C, 3B

AT: 1C, 2C, 3B

IM: 1C, 2C, 3B

AT: 1C, 2C, 3B

AE: 1C, 2C, 3B

EZ: 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

RNA: 1A, 1C, 2C, 3B

SP: 1B, 1C, 2C, 3B

ZGO: 1A, 1B, 2A, 2C, 3A, 3B

Relevant conflicts of interest/financial disclosures: Nothing to report.

References

- 1.Senkevich K, Gan-Or Z. Autophagy lysosomal pathway dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease; evidence from human genetics. Parkinsonism & related disorders 2020;73:60–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidransky E, Nalls MA, Aasly JO, et al. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med 2009;361(17):1651–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan-Or Z, Ozelius LJ, Bar-Shira A, et al. The p.L302P mutation in the lysosomal enzyme gene SMPD1 is a risk factor for Parkinson disease. Neurology 2013;80(17):1606–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robak LA, Jansen IE, van Rooij J, et al. Excessive burden of lysosomal storage disorder gene variants in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2017;140(12):3191–3203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alcalay RN, Wolf P, Levy OA, et al. Alpha galactosidase A activity in Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis 2018;112:85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nalls MA, Blauwendraat C, Vallerga CL, et al. Identification of novel risk loci, causal insights, and heritable risk for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. The Lancet Neurology 2019;18(12):1091–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senkevich K, Zorca CE, Dworkind A, et al. GALC variants affect galactosylceramidase enzymatic activity and risk of Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Shaimardanova AA, Chulpanova DS, Solovyeva VV, et al. Metachromatic Leukodystrophy: Diagnosis, Modeling, and Treatment Approaches. Frontiers in Medicine 2020;7(692). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang D, Nalls MA, Hallgrímsdóttir IB, et al. A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies 17 new Parkinson’s disease risk loci. Nat Genet 2017;49(10):1511–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Makarious MB, Lake J, Pitz V, et al. Large-scale Rare Variant Burden Testing in Parkinson’s Disease Identifies Novel Associations with Genes Involved in Neuro-inflammation. medRxiv 2022:2022.2011.2008.22280168.

- 11.Lee JS, Kanai K, Suzuki M, et al. Arylsulfatase A, a genetic modifier of Parkinson’s disease, is an α-synuclein chaperone. Brain 2019;142(9):2845–2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pan HX, Wang YG, Zhao YW, et al. Evaluating the role of ARSA in Chinese patients with Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Fan Y, Mao CY, Dong YL, et al. ARSA gene variants and Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2020;143(6):e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Makarious MB, Diez-Fairen M, Krohn L, et al. ARSA variants in α-synucleinopathies. Brain 2019;142(12):e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gan-Or Z, Rao T, Leveille E, et al. The Quebec Parkinson Network: A Researcher-Patient Matching Platform and Multimodal Biorepository. J Parkinsons Dis 2020;10(1):301–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alcalay RN, Levy OA, Wolf P, et al. SCARB2 variants and glucocerebrosidase activity in Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2016;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes AJ, Ben-Shlomo Y, Daniel SE, Lees AJ. What features improve the accuracy of clinical diagnosis in Parkinson’s disease. A clinicopathologic study 1992;42(6):1142–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Postuma RB, Berg D, Stern M, et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Movement disorders 2015;30(12):1591–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudakou U, Ruskey JA, Krohn L, et al. Analysis of common and rare VPS13C variants in late onset Parkinson disease. bioRxiv 2019:705533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009;25(14):1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome research 2010;20(9):1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang CC, Chow CC, Tellier LC, Vattikuti S, Purcell SM, Lee JJ. Second-generation PLINK: rising to the challenge of larger and richer datasets. Gigascience 2015;4(1):s13742–13015-10047–13748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwaki H, Leonard HL, Makarious MB, et al. Accelerating Medicines Partnership: Parkinson’s Disease. Genetic Resource. Mov Disord 2021;36(8):1795–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carson AR, Smith EN, Matsui H, et al. Effective filtering strategies to improve data quality from population-based whole exome sequencing studies. BMC Bioinformatics 2014;15:125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic acids research 2010;38(16):e164–e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kircher M, Witten DM, Jain P, O’Roak BJ, Cooper GM, Shendure J. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nature Genetics 2014;46(3):310–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopanos C, Tsiolkas V, Kouris A, et al. VarSome: the human genomic variant search engine. Bioinformatics 2018;35(11):1978–1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S, Emond MJ, Bamshad MJ, et al. Optimal unified approach for rare-variant association testing with application to small-sample case-control whole-exome sequencing studies. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91(2):224–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhan X, Hu Y, Li B, Abecasis GR, Liu DJ. RVTESTS: an efficient and comprehensive tool for rare variant association analysis using sequence data. Bioinformatics 2016;32(9):1423–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee S, Teslovich TM, Boehnke M, Lin X. General framework for meta-analysis of rare variants in sequencing association studies. Am J Hum Genet 2013;93(1):42–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JS, Kanai K, Suzuki M, et al. Arylsulfatase A, a genetic modifier of Parkinson’s disease, is an α-synuclein chaperone. Brain 2019. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Bongarzone ER, Escolar ML, Gray SJ, Kafri T, Vite CH, Sands MS. Insights into the pathogenesis and treatment of Krabbe disease. Pediatric endocrinology reviews: PER 2016;13:689–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sidransky E, Nalls MA, Aasly JO, et al. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson’s disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2009;361(17):1651–1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Knaap MS, Bugiani M. Leukodystrophies: a proposed classification system based on pathological changes and pathogenetic mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol 2017;134(3):351–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suzuki K, Iseki E, Togo T, et al. Neuronal and glial accumulation of α- and β-synucleins in human lipidoses. Acta Neuropathologica 2007;114(5):481–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinelli P, Ippoliti M, Montanari M, et al. Arylsulphatase A (ASA) activity in parkinsonism and symptomatic essential tremor. Acta Neurol Scand 1994;89(3):171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoo HS, Lee JS, Chung SJ, et al. Changes in plasma arylsulfatase A level as a compensatory biomarker of early Parkinson’s disease. Scientific Reports 2020;10(1):5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fabelo N, Martín V, Santpere G, et al. Severe Alterations in Lipid Composition of Frontal Cortex Lipid Rafts from Parkinson’s Disease and Incidental Parkinson’s Disease. Molecular Medicine 2011;17(9):1107–1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1 Study population

Supplementary Table 2 Detailed information on the ARSA molecular inversion probes

Supplementary Table 3 Coverage details for ARSA

Supplementary Table 4 Rare ARSA variants for cohorts sequenced at McGill

Supplementary Table 5 Rare ARSA variants for UKBB and AMP-PD cohorts

Supplementary Table 6 PD patients carrying multiple rare ARSA mutations.

Supplementary Table 7 Kernel analysis of ARSA in full cohort

Supplementary Table 8 Burden analysis of ARSA using CMC-Wald test

Supplementary Table 9 Kernel analysis of ARSA among early onset PD patients (<50 years old)

Supplementary Table 10 Previous rare variants analysis of ARSA in PD

Supplementary Figure 1. Family trees of two families with Metachromatic leukodystrophy and Parkinson’s disease in history. Square – male; circle – female; open symbol – healthy; grey– Parkinson’s disease; filled black symbol – Metachromatic leukodystrophy; PD – Parkinson’s disease; MLD – Metachromatic leukodystrophy; crossed line – deceased subject; wt – wild-type.

(A) Octameric assembly of the human ARSA (pdb 1AUK). Glu382 side-chains are labeled as yellow spheres. (B) Close up of the interface between two chains (A and B) where Glu382 is located. The mutation p.E382K would disrupt an intrachain hydrogen bond between the side-chain carboxyl of Glu382 and the main chain amide of Phe472. The backbone carbonyl oxygen of Glu382 also interacts with the side-chain of Lys457.