Abstract

Recent literature demonstrates an interdependence between relatives and healthcare providers throughout euthanasia processes. Yet, current guidelines and literature scarcely specify the interactions between healthcare providers and bereaved relatives. The aim of this work consisted of providing an insight into bereaved relatives’ experiences (1) of being involved in euthanasia processes and (2) of their interactions with healthcare providers before, during, and after the euthanasia. The research process was guided by the principles of constructivist grounded theory. Nineteen Dutch-speaking bereaved relatives of oncological patients, who received euthanasia at home or in a hospital less than 24 months ago, participated via semi-structured interviews. These interviews were conducted between May 2021 and June 2022. Due to the intensity of euthanasia processes, relatives wanted to be involved as early as possible, in order to receive time, space, and access to professionals’ support whilst preparing themselves for the upcoming loss of a family member with cancer. Being at peace with the euthanasia request facilitated taking a supportive attitude, subsequently aiding in achieving a serene atmosphere. A serene atmosphere facilitated relatives’ grief process because it helped them in creating and preserving good memories. Relatives appreciated support from healthcare providers, as long as overinvolvement on their part was not occurring. This study advocates for a relational approach in the context of euthanasia and provides useful complements to the existing euthanasia guidelines.

Keywords: bereavement, euthanasia, family, grounded theory, healthcare providers, interview, cancer, qualitative research

Background

Assisted dying is perceived as a means of dying in a controlled and/or painless way (Kelly et al., 2020), which reflects the principles of autonomy and self-determination and is subject to time-specific norms (Hamarat et al., 2021). Assisted dying, often also framed as “hastened death,” “medical assistance in dying,” and “voluntary assistance in dying,” is an umbrella concept for euthanasia and (physician) assisted suicide (Mroz et al., 2021). Assisted suicide refers to the process wherein a medical professional supplies a lethal drug followed by self-administration by the patient as opposed to euthanasia where a healthcare provider (often a physician) proceeds to the administration of the drug to the patient (Yan et al., 2022). In Belgium, the term euthanasia is commonly used to indicate assisted dying, whereas self-administration by the patient (called “hulp bij zelfdoding” in Flemish) remains an unclear concept under the Belgian law on euthanasia (LEIF, 2023). Therefore, the term euthanasia will be used in this article instead of assisted dying. Euthanasia became legal in Belgium in 2002 and is solely performed by a physician in accordance with strict due care criteria, as specified in the Belgian law. According to these criteria, patients requesting euthanasia must be competent persons, who request euthanasia repeatedly in a voluntary and well-considered way, without any form of external pressure. The request results from constant and unbearable physical and/or psychological intolerable suffering, which cannot be alleviated through a reasonable alternative solution (De Laat et al., 2018). The attending physician has to consult at least one independent physician in the case of terminal illness. In the case that death is unlikely to occur in the near future, two must be consulted, one of whom must be a specialist in the patient’s condition (Belgian Official Gazette, 2002). The attending physician is also obliged to inform the nursing team of the patient’s request, as opposed to informing relatives (Belgian Official Gazette, 2002).

Despite relatives being overlooked in legal frameworks of assisted dying, a recent review emphasizes the interdependence between relatives and healthcare providers (Roest et al., 2019). The findings indicate that physicians take both the patient’s autonomy as well as the broader social context into account when fulfilling a euthanasia request. Acknowledging the social context is important because a death-related loss impacts five (Beuthin et al., 2022) to nine (Verdery et al., 2020) relatives on average. Professionals’ support can mitigate the risk for developing bereavement-related complications (Kustanti et al., 2021). Relatives can benefit from professionals’ informational, instrumental, appraisal, and emotional support. Informational support consists of logistic help, advice, and information enabling informed decision-making. Instrumental support includes tangible assistance and services, while empathy, trust, and caring are central to emotional support. Finally, appraisal support encourages people to self-evaluate through affirmation, feedback, and equality (Cacciatore et al., 2021; Price et al., 2011). Previous research on bereaved parents ascribes an important role to nurses for the provision and coordination of this kind of support, especially when the informal network is insufficient (Price et al., 2011).

To date, Belgian euthanasia guidelines scarcely mention interactions between healthcare providers and relatives, and how support can be provided before and after loss (De Laat et al., 2018; LEIF, 2020). Literature is predominantly focused on physicians’ (Beuthin et al., 2022; van Marwijk et al., 2007) and nurses’ experiences (Beuthin et al., 2018; De Bal et al., 2006) of being involved in euthanasia processes. When support to relatives is mentioned, this is often vaguely described as “giving support” (Inghelbrecht et al., 2010), “best possible care” (Bellens et al., 2020), “guiding, counseling, and supporting family” (Denier et al., 2009), and “having deeper conversations”(Beuthin et al., 2018). Moreover, these descriptions lack in-depth insights into the underlying mechanisms of interaction (Hales et al., 2019; Oczkowski et al., 2021; Thangarasa et al., 2022). The aim of this paper is two-fold, namely, to understand relatives’ experiences (1) of being involved in euthanasia processes and, (2) of their interactions with healthcare providers before, during, and after the euthanasia of a family member with cancer.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative study design was chosen to gain in-depth insights into relatives’ experiences of being involved in the euthanasia process of a family member suffering from cancer. Qualitative research enables one to explore the way people interpret and give meaning to experiences and the world in which they live (Savin-Baden & Major, 2013).

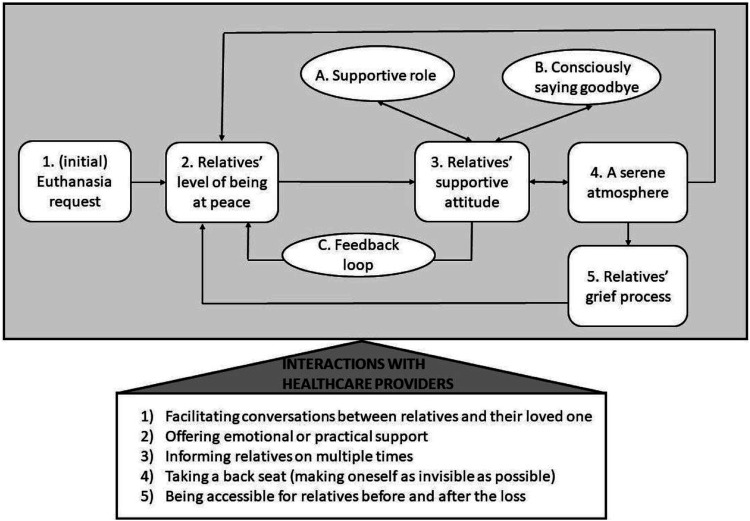

Principles of a constructivist grounded theory approach guided the research process, which is characterized by an iterative data collection and analyzing process (Charmaz, 2004), ultimately resulting in a robust theory (see Figure 1). Constructivism states that knowledge and truth are created (co-production) rather than discovered, and constructed meanings can be presented by an inductively developed theory or patterns of meaning. Grounded theory is a research approach aimed at developing a theory distilled from the study of cases (Savin-Baden & Major, 2013). This inductive research approach fits the aim of the paper due to the scarcity of literature available on this topic and the need to understand relatives’ experiences of euthanasia in order to provide needs-based care. Ultimately, a theory was developed contributing to both research and practice of caring for (nearly) bereaved relatives.

Figure 1.

Central concepts and underlying relationships resulting from the participants’ accounts.

Sampling Strategy

Participants were recruited and interviewed between May 2021 and June 2022. Diverse recruitment strategies were implemented: newsletters, advocacy groups, snowball sampling, and a longitudinal survey study (see Supplementary Material 1). The longitudinal survey and this interview study are part of a mixed methods study called “the BE-CARED project” conducted with Flemish relatives and healthcare providers aiming to further develop needs-based bereavement care in oncology and euthanasia.

Inclusion criteria consisted of: (1) being a Dutch-speaking relative of ≥18 years old (2) of a cancer patient who died in a hospital or at home due to euthanasia and (3) the euthanasia occurred less than 2 years ago. People could offer their participation when being a first- or second-degree relative or an in-law. A purposive sample was derived to achieve maximum homogeneity and heterogeneity in terms of the relatives’ age, gender, and relationship to the deceased (Holloway & Galvin, 2016).

Data Collection and Processing

Data collection consisted of one-time semi-structured interviews until data saturation emerged. Data saturation was reached in this study when no new data appeared through sampling and analyzing the interviews, and the central concepts and underlying mechanisms were well-developed and described (Morse, 2004).

Interviews were conducted by two female interviewers online or face to face in the absence of interference by environmental disturbing factors and individually, except for the interview of one couple. Both interviewers displayed no previous relationship with the participants. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber, and recordings were deleted after finishing data analysis.

The interview guide (see Supplementary Material 2) was based on literature (Andriessen et al., 2020; Roest et al., 2019; Swarte et al., 2003), as well as input from experts in palliative care, euthanasia, and grief. The interview guide was iteratively adapted by deleting, adding, or fine-tuning questions.

Data Analysis

Interviews were analyzed by the constant comparative method inherent to the principles of a constructivist grounded theory approach. The constant comparative method aims to develop a theory by testing and comparing concepts at different levels and timepoints, which also helps identifying gaps or when to stop data collection (Aldiabat & Le Navenec, 2018). Interviews and coded fragments were continuously compared to develop these central concepts, in which findings informed the next wave of data collection.

Ensuring Quality of the Research Process and Product

Different strategies were implemented to ensure product and process quality contributing to the research’s validity and trustworthiness: (1) method and investigator triangulation, (2) external audit, (3) positionality statement, (4) constant data comparison, (5) valid data analysis methods, and (6) a dense description of methods and findings.

Method triangulation was achieved by adding observations and field notes to each interview, while investigator triangulation was accomplished by involving experts (N.V.D.N., R.P., L.D., L.V.D.B., L.V.H., S.D., and C.B.) with various multidisciplinary backgrounds (medicine, nursing, and psychology, sociology, and educational sciences) and different interviewers (C.B. and S.D.). Second, two experts (R.P. and L.V.D.B.) externally reviewed the research products as well as the process in order to check if data were grounded and accurate. Third, since both interviewers are the primary instrument of data collection, a written reflective framework was performed beforehand (e.g., including individual belief systems, goals, and personal assumptions) to check if bias could have influenced the results (Mortari, 2015). According to the interviewers’ personal framework, both researchers (C.B. and S.D.) have a favorable attitude toward assisted dying because they are currently working on or finished a PhD in euthanasia. Additionally, their educational background (educational sciences and sociology) may have created a bias in the sense that they favor increased attention to the surrounding network of the patient. To deal with these possible biases, meetings were frequently held with the experts mentioned earlier to reflect on the interviews itself (e.g., interview style and guide) and the analysis of results. Fourthly, the constant comparison of data helps to define and refine the emergent theory grounded in the participants’ data. Moreover, the researchers reported a dense description of methods (see the Methods section) and findings (e.g., thick description of central concepts and sufficient quotations) enabling readers to consider if good decisions were taken, and whether findings are transferable (Savin-Baden & Major, 2013). Finally, the combination of two valid data analysis methods was used: traditional tools (e.g., notes and colored pens) and digital software (NVivo 12 QSR International). Software facilitates data retrieval and management, while writing, (re)arranging notes, and visualizing data result in a more meaningful data interaction due to temporization (Maher et al., 2018).

Ethical Considerations

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ghent University Hospital [registration number: B6702020000289]. All participants were well-informed about the study in advance by telephone and provided oral and written consent for their participation. The informed consents were in accordance with (1) the regulation 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 April 2016 on the protection of natural persons’ processing of personal data and the free movement of data, (2) GDPR regulations, and (3) the Belgian Act of 30 July 2018 on the Protection of Natural Persons with Regard to the Processing of Personal Data.

Participants were informed that they could always contact the research group or the interviewers in case of questions or to reflect on (the impact of) the interview. The contact information was listed in the recruitment flyer and the informed consent. Before the start of the interview, participants received verbal assurance stating that pausing or stopping the interview was feasible when they felt it was too intense or difficult. When interviewers noticed throughout the interview that relatives were at risk for developing or had developed grief-related disorders, they explored relatives’ need for referral information on specialized organizations (e.g., grief or mental health organizations).

Besides, participants were well-informed about the pseudonymization process by telephone and by careful reading of the informed consents, implying usage of codage for interview transcripts, removal of any personal data (e.g., names), and decontextualization of quotations to avoid participants identification. Finally, participants’ contact information received password protection and safe storage separated from the interview transcripts.

Findings

A total of 19 family members were interviewed, of which the majority had a postgraduate education (N = 11), were female (N = 10), were non-religious (N = 16), and had a spouse (N = 10). On average, the participants were 63 years old (range: 33–86). One interview with a couple was collected, and two other participants lost the same person. Patients (N = 17) were often female (N = 10), on average 70 years old (range: 32–88), and often died at home (N = 10). The majority died more than a month after the euthanasia request (N = 12) and often asked for euthanasia 6 months after the cancer diagnosis (N = 10). Interviews were on average 105 minutes long (range: 57–183 minutes) and usually occurred face to face (N = 16). More information on the sociodemographic characteristics is available in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Participants (N = 19) and the Deceased (N = 17).

| Characteristics of the participants (N = 19) | |

|---|---|

| Age (in years), N (%) | |

| 31–40 | 1 (5.3%) |

| 41–50 | 1 (5.3%) |

| 51–60 | 7 (36.8%) |

| 61–70 | 5 (26.3%) |

| 71–80 | 4 (21.1%) |

| 81–90 | 1 (5.3%) |

| Relationship to the deceased, participant is a …, N (%) | |

| Spouse | 10 (52.6%) |

| (Legitimate) child | 6 (31.6%) |

| Parent | 2 (10.5%) |

| Granddaughter | 1 (5.3%) |

The central concepts and underlying relationships identified in this study are depicted in Figure 1. Despite the intensity of the euthanasia process, we found the presence of relatives offered value to individuals receiving euthanasia, and relatives timely involvement, in turn, met their needs for preparation, understanding, and support. Feeling better prepared was associated with an increased serenity, in which relatives (to a certain extent) cognitively and affectively understood the request and expressed their support. This supportive attitude helped them to consciously say goodbye and take up a supportive role, yet the supportive attitude could be interrupted at any moment along the way. Relatives appreciated professionals’ (proactive) support, as long as they did not take over the process or become overinvolved (Figure 1). The central concepts are discussed separately and linearly but in reality are intertwined in various ways.

(Initial) Euthanasia Request

The moment relatives were informed of the request, they became involved in the euthanasia process of their family member with cancer. In most cases, patients informed their relatives themselves, while others said healthcare providers facilitated this conversation. Staff offered this by bringing up the topic themselves, stimulating relatives to initiate the conversation with the patient, and/or helping patients to express their wish. Professionals’ support was appreciated as long as they did not take over or became overinvolved.

I told my father: “I heard you had a conversation with the doctor, in which she said she could no longer cure you. She also told me that you refuse to give up because of us. Dad, you can stop fighting against something you cannot win. It is ok to let go.” I found it very difficult, but I had to do it rather than the healthcare providers because he was doing this for us. (IV8, parent died in the hospital)

Conversations that preceded or were held shortly after the patient’s terminal diagnosis made relatives expect the request. Nonetheless, for the majority of participants, both their perspective on the request and the patient’s (initially) differed. They often felt disbelief, anxious, and reluctant to accept the upcoming loss, while the patient was relieved and had come to terms with his/her imminent death. Participants preferred to be involved as soon as possible in order to understand the patient’s request and to receive professional support.

Level of Being at Peace With the Request

Being at peace with the request was understood as (a certain extent of) cognitive and affective understanding. The pace of coming to an understanding differed substantially between participants. Some immediately found it to be the right decision, whilst others had doubts and needed more time and space.

Initially, I found her decision selfish, but gradually my opinion has changed. […]. Now, I wonder how I could have felt that way. She was not selfish at all, on the contrary, she was brave. […] I just needed to be able to talk to someone, who pointed out to me everything that Emma was going to leave behind once she died. (IV12, spouse died at the hospital)

Cognitive Understanding

Relatives cognitively understood the request, if they found the underlying motives rationally justified. Higher cognitive understanding was associated with (1) perceiving the person with cancer’s situation as desperate and incurable; (2) being adequately informed about the legal framework and course of the euthanasia; and (3) being (regularly) confronted with the patient’s pain and suffering. The participants’ role as caregivers was helpful, as they closely witnessed deteriorations in the person with cancer’s condition. Professionals needed to communicate clearly and comprehensively with relatives about the patient’s condition if relatives were not primary caregivers.

I found it difficult seeing the cancer take control of his body and that he was deteriorating so quickly. Hence, I realized that things could not go on like this. I was unwilling to say goodbye, but I realized that there was no other option left. (IV2, spouse died at home)

Affective Understanding

When relatives affectively understood the request, they could reconcile with the request and gave their family member with cancer permission to let go. Cognitive comprehension of the request often preceded relatives’ affective understanding.

I was not ready, I always postponed it. I never thought it would end, although, I mentally knew she was not going to grow old with this diagnosis. […] I was unable to physically or mentally say goodbye to Anne, anyhow, she did with a lot of tears … I just sat there, silent, because I lacked the courage. (IV14, child died at the hospital)

Better affective understanding was associated with (1) patients being older, (2) relatives being able to have open conversations about death, dying, and end of life with their family member suffering from cancer, healthcare providers (e.g., family meetings), and/or their informal network (e.g., compassionate listening); (3) a shared belief that a good death entailed an absence of deterioration and suffering between patients and their relatives; and (4) mutual respect for individual choices within the relationship.

I struggled with it at first, although, eventually I reconciled. […] I have no right to make that choice, but she has to. The oak and cypress have to give each other space because they can never grow in each other’s shadow. It is not because I am her husband that I have to make that choice, no, we have never lived like that. (IV7, spouse died at home)

Supportive Attitude

Relatives’ feeling of being at peace with the request facilitated taking a supportive attitude, which could be expressed through (non)verbal behavior. These (non)verbal behaviors could be directed toward the person affected by cancer (e.g., explicitly giving verbal permission), staff (e.g., advocating for the patient’s wish), and/or other relatives or friends (e.g., defending the euthanasia request). In turn, a supportive attitude helped relatives in taking on a supportive role and consciously saying goodbye. This supportive attitude could be interrupted at any moment before or after the loss. For example, some relatives reflected on their active involvement throughout the euthanasia and wondered if they should have delayed the process in order to have more time together. In this case, participants found it helpful if healthcare providers compassionately listened and informed them that the patient would have died soon anyway.

The general practitioner told me afterwards that she would have died within two weeks, which confirmed that we made the right choice. Otherwise, she would have suffered needlessly. (IV18, spouse died at home)

Active Supportive Role

Almost all participants wanted the request of their family member with cancer to be granted, and some even took an active supportive role (e.g., the administrative paperwork). In this case, the person with cancer assumed that their relative would facilitate the euthanasia request as they were already (primary) caregivers.

Some relatives felt in the period before or after the death that they had contributed to “killing” him/her. They wondered how it was possible that they had given their permission to let go, even though this fulfilled the patient’s wish. These thoughts sometimes led to a feedback loop, which will be discussed in a following section.

I think it is mind-blowing that I found it [the euthanasia] so normal. I was actually always busy accompanying someone to his death. That is what is all about. […] At that time, I did not see it this way, I thought: “It will be a solution to him, his suffering is going to be over.” (IV3, spouse died at home)

Consciously Saying Goodbye

A supportive attitude encouraged relatives to consciously say goodbye and take care of unfinished business. Still, talking about death and dying required courage and honesty. Some relatives wanted to spare the person with cancer and themselves by not talking about the imminent death.

I was very emotional the first time I saw him [after being informed of his euthanasia request]. I knew he was going to die soon. The next time was different because I could control my emotions better. When we talked, it was really just small talk, there was nothing more to say. […] The more you say goodbye, the harder it gets. […] and I wanted to stay strong because I found it hard enough for him. (IV10, grandparent died at the hospital)

Relatives appreciated the emotional support of staff and/or them opening up conversations about the topic. In the period leading up to the euthanasia, participants wanted to be as close as possible to their family member with cancer. They expected professionals to facilitate proximity, by offering a private room, flexible visiting hours, providing information, etc. Most relatives wanted staff to keep a low profile in order to fully experience these final moments together.

They were almost stuck to the wall. I guess they avoided disturbing us. I find it difficult to describe. You can be physically present, but that was not really the case. […] I appreciated it because at that moment only we count. (IV8, parent died at the hospital)

Feedback Loop

Relatives’ supportive attitude toward euthanasia could be interrupted (briefly) by certain events that made the loss (more) tangible (e.g., farewell dinner, friends and family stopping by to say goodbye, and funeral planning). These events could install a feedback loop, due to the feelings of grief and anxiety for the imminent death, triggering relatives to reevaluate their level of being at peace with the request. These events could occur before (e.g., setting the date), during (e.g., administering the lethal medication), and after the euthanasia (e.g., receiving confirmation of the death).

You do not accept what happens internally. Accepting death on paper is ok, but when you face it and you see it happen … It changes your whole life. It certainly does not give you a feeling of satisfaction: “her suffering is over,” as some people tell you. No, not at all, because for that feeling you have to look at the period before it happens. (IV16, spouse died at home)

The Central Aim of Achieving a Serene Atmosphere

Serenity throughout the euthanasia process was influenced by relatives’ level of being at peace with the request. The overall aim of most relatives was to strive for a good death, which they felt was equivalent to dying in a serene atmosphere. For the participants, serenity meant an atmosphere of connectedness, peace, and intimacy, in which the person with cancer did not experience discomfort and in which the dying process could take place as naturally as possible (preferably not drawn out). A serene atmosphere throughout the process, as well as on the day of the euthanasia, made relatives feel that they had made the right decision by supporting the request. In addition, a serene atmosphere also contributed to their sense of being at peace.

She was comfortable, it looked like she just fell asleep, her face also had the expression: “Yes, it is over” […]. For us, it was a beautiful death and all the people present said: “I want to die like her.” (IV4, parent died at home)

Relatives tried to “stay strong” in the period before and on the day of the euthanasia to maintain a serene atmosphere and spare their family member with cancer from their thoughts, worries, and feelings regarding the euthanasia. Relatives often vent their emotions to other family members or professionals after the patient’s death.

You stay strong until the euthanasia, you just go with it. After that, you realize it is over. […] The moment the euthanasia was performed, I felt an emotional release. […]. You should not start crying when the person says: “I am completely done with it.” That is not the right time, you can always mourn later. (IV6, spouse died at home)

Grief Process

Relatives’ grief process was facilitated by a serene atmosphere, which helped to create and preserve good memories. Regardless of achieving a serene death, almost all participants had a setback after loss, often when arranging practical matters had ended. This was due to the focus shifting from fulfilling the patient’s needs to attending to their own.

The period afterwards has been very tough […] Until the last moment, you do everything you can to provide comfort. That is what your thoughts are mainly focused on. When she passed away, I started thinking differently […] The main theme that keeps coming back is the enormous grief, and the questions: “How should I go on?” What should I do? (IV16, spouse died at home)

Most participants experienced the euthanasia as positive, providing a solution for a dignified death. Thus, their reflections on the euthanasia were accompanied by warm feelings.

It is an unpopular opinion to say that you are glad your wife died. You should not take it that way. I am just happy she was able to die like that. I think that is important, also for my grief process. I know she was happy about it, so I am happy too. (IV6, spouse died at home)

Therefore, few expectations existed regarding aftercare. Relatives felt it was sufficient to receive contact details to contact healthcare providers if necessary.

Discussion

Collectively, these results indicate the need for a greater awareness amongst professionals about the way relatives can feel involved, and a joint trajectory can be achieved, which should be reflected in existing euthanasia guidelines. These findings, along with a recent interview study (Brown et al., 2022), show that a relational approach, in which healthcare providers invest time in the relationship with patients, families, and other healthcare providers, is a crucial milestone in achieving good care for all involved persons in the context of assisted dying. Attention to relatives’ needs can contribute positively to their grief and bereavement (Goldberg et al., 2021).

Besides, these findings illustrate relatives’ experience of being involved in a euthanasia process as related to whether serenity can be achieved. Moreover, this work provides a conceptualization of serenity: an atmosphere of connection, peace, and intimacy, in which the patient can die comfortably and as naturally as possible. Previous research on assisted dying already demonstrates the importance of “an optimal dying experience,” yet the conceptualization remains rather vague or absent (Oczkowski et al., 2021; Thangarasa et al., 2022). In this perspective, previous research shows different paces of finding peace with the request, and more detailed information on the conceptualization and contributing factors are lacking (Oczkowski et al., 2021; Thangarasa et al., 2022). Present findings unveil these contributing factors and show that time, space, and support are needed to establish such a serene atmosphere and prepare for the coming loss. Our study found that participants appreciated staff’s supporting strategies, although an emphasis is put on the importance of tailoring support to different family members and at different timepoints. Research points out that feeling prepared for death is characterized by three dimensions (Treml et al., 2021): first, cognitive preparedness, which includes practical, medical, spiritual, and psychosocial information; second, affective preparedness, which involves helping relatives prepare emotionally and mentally for the coming loss; and finally, behavioral preparedness, which refers to practical arrangements (e.g., funeral plans).

Relatives also clearly favor presence of staff before, during, and shortly after the loss when needed. Yet, there are limited expectations regarding aftercare, as the focus is primarily on the period before the loss. Similar results were also found in previous research, as the study of Hales et al. (2019) showed that the family preferred pre-loss support, as being able to comply with the patient’s request for euthanasia helped them cope with the loss. Although the participants felt adequately prepared for the loss, most relatives suffered a setback several months after loss. This normative experience illustrates that grieving is a dynamic, unpredictable, and continuous process of making sense and going back and forth (Walsh, 2020). Grief should not be pathologized; therefore, the literature emphasizes the importance of needs-based care and identifying those at risk for developing grief-related complications (Hudson et al., 2018). Staff plays an important role in the early identification of groups at risk and appropriate referral. This strategy is consistent with the stepped or tiered model, in which all bereaved should receive some form of support, and more intensive care is reserved for relatives at risk (Aoun et al., 2012). In the pre-loss period, relatives find it important to be adequately informed by staff contributing to their cognitive understanding. Affective understanding is enhanced by staff facilitating conversations between the relatives and their family member with cancer about end of life and the request for euthanasia. Relatives also find it important to vent their feelings about the imminent death to staff. Cognitive and affective understanding can be linked to the previously discussed literature on cognitive and affective preparedness for death. Healthcare providers have an important role in terms of supporting relatives’ cognitive and emotional coping with the loss, especially when relatives are unable to rely on their informal network (Price et al., 2011).

Relatives are grateful for timely involvement despite the intensity of the euthanasia process, which is also found in previous studies (Brown et al., 2022; Hashemi et al., 2021; Oczkowski et al., 2021; Smolej et al., 2022). Early involvement is crucial for relatives to access professionals’ support, and not being informed is associated with adverse grief outcomes (Hashemi et al., 2021). Early involvement can help relatives construct meaning, cope with the loss, and integrate the upcoming loss into their lives (Lichtenthal et al., 2011). Although relatives find early involvement important, the laws of several countries (such as Australia, Belgium, and Canada) do not require that next of kin be notified of the request.

Our findings increase the visibility of relatives in the context of assisted dying and present how a joint trajectory can be achieved, in contrast to legal frameworks in which relatives are often overlooked. It offers insights into relatives’ experiences with euthanasia and the interaction with healthcare providers throughout the entire process. Moreover, it highlights several actions that healthcare providers can perform before and after the loss in order to facilitate relatives’ grief process. It might be indicated for healthcare providers to proactively take care of relatives’ needs as relatives are inclined to prioritize the needs of their family member with cancer. Our findings complement a recent interview study that presents the perspective of healthcare providers on this issue (Boven et al., 2023).

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study is characterized by some strengths such as gaining in-depth insights into relatives’ experiences of being involved in a euthanasia process and the interaction with staff. Quality of research findings and process were ensured throughout the study (see the Ensuring Quality of the Research Process and Product section).

On the other hand, this study also has several limitations: (1) Inclusion of a small sample size after reaching data saturation (see the Data Collection and Processing section). Relatives’ negative experiences of euthanasia might be underreported, as people with greater feelings of grief have higher nonresponse rates (Stroebe & Stroebe, 1990). (2) Inclusion of only one relative that was not able to attend the euthanasia. Recent research suggests that persons who are absent during the euthanasia might face unique challenges and have different grief reactions (Andriessen et al., 2020). To date, it remains unclear how different reasons for absence (practical, obliged by healthcare providers, fear, etc.) show a distinct impact on the grief process of relatives. (3) Inclusion of relatives of deceased oncological patients. Therefore, the transferable value to other conditions is unknown. (4) Finally, COVID-19 and the corresponding restrictions might have biased our findings, as contact between relatives and healthcare providers was often limited. Furthermore, COVID also required changes in the research protocol, as we decided to allow relatives to choose between face-to-face or online interviews (due to the risk of contamination). Interviewers adequately informed participants about the safety measures to prevent spreading COVID (e.g., face masks (FFPP2), alcohol gel, use of a plastic screen between the participant and relative, and ventilated room). Originally, participants would only be recruited through the longitudinal survey study of the BE-CARED project. Due to COVID-19, the study got delayed and participants were recruited in multiple ways (newsletters, advocacy groups, etc.) (see the Sampling Strategy section).

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data confirms that relatives aim at striving for a good death, which is understood as a serene death farewell. Preparedness for the imminent death contributes to a more serene atmosphere, which is associated with (a certain level of) understanding and a supportive attitude. Relatives’ level of understanding can be supported by professionals opening up conversations about the end of life and the euthanasia request and by adequately informing relatives throughout the process. Nonetheless, early involvement is required to offer relatives time, space, and access to professionals’ support needed during their preparation phase for the imminent death. Relatives appreciate support from healthcare professionals yet favor professionals taking a position in the background. Expectations regarding aftercare are limited, as relatives feel that the main emphasis converges on support before the loss. For most relatives, receiving contact information to contact staff if necessary was sufficient. Despite relatives’ appreciation of being timely involved, this is not required by the Belgian law. The reported findings highlight the importance of a relational approach and increasing the visibility of relatives in the context of euthanasia. Moreover, these insights complement existing euthanasia guidelines and offer concrete directions for staff to achieve a joint trajectory. Further research would benefit from including relatives who were not at peace with their family member’s euthanasia request or with negative experiences regarding assisted dying, exploring their experiences of being involved in euthanasia processes and their needs regarding professionals’ bereavement care.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Relatives’ Experiences of Being Involved in Assisted Dying: A Qualitative Study by Charlotte Boven, Let Dillen, Sigrid Dierickx, Lieve Van den Block, Ruth Piers, Nele Van Den Noortgate, and Liesbeth Van Humbeeck in Qualitative Health Research.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our gratitude to the relatives for their interest and participation in the study. We also want to thank Karen Versluys for her input on Figure 1, and Sandrine Herbelet and Keegan Humphrey for the language editing.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Kom op tegen Kanker [grant number: 2019/11010], the Flemish cancer society. The funding source had no involvement in the research conduct nor in the preparation of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Ethical Statement

Ethical Approval

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ghent University Hospital (B6702020000289). All participants gave oral and written consent to participate. All data and quotes were pseudonymized.

ORCID iD

Charlotte Boven https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9069-3370

References

- Aldiabat K., Le Navenec C-L. (2018). Data saturation: The mysterious step in grounded theory methodology. Qualitative Report, 23(1), 245–261. 10.46743/2160-3715/2018.2994 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andriessen K., Krysinska K., Castelli Dransart D. A., Dargis L., Mishara B. L. (2020). Grief after euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Crisis, 41(4), 255–272. 10.1027/0227-5910/a000630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoun S. M., Breen L. J., O'Connor M., Rumbold B., Nordstrom C. (2012). A public health approach to bereavement support services in palliative care. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 36(1), 14–16. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2012.00825.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belgian Official Gazette . (2002). Law of 28 may 2002 on euthanasia. Belgian Official Gazette. http://www.const-court.be/public/e/2015/2015-153e.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Bellens M., Debien E., Claessens F., Gastmans C., Dierckx de Casterlé B. (2020). It is still intense and not unambiguous." Nurses' experiences in the euthanasia care process 15 years after legalisation. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(3-4), 492–502. 10.1111/jocn.15110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuthin R., Bruce A., Scaia M. (2018). Medical assistance in dying (MAiD): Canadian nurses' experiences. Nursing Forum, 53(4), 511–520. 10.1111/nuf.12280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuthin R., Bruce A., Thompson M., Andersen A. E. B., Lundy S. (2022). Experiences of grief-bereavement after a medically assisted death in Canada: Bringing death to life. Death Studies, 46(8), 1982–1991. 10.1080/07481187.2021.1876790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boven C., Van Humbeeck L., Van den Block L., Piers R., Van Den Noortgate N., Dillen L. (2023). Bereavement care and the interaction with relatives in the context of euthanasia: A qualitative study with healthcare providers. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 140(1), 104450. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.104450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J., Goodridge D., Harrison A., Kemp J., Thorpe L., Weiler R. (2022). Care Considerations in a patient- and family-Centered medical assistance in dying Program. Journal of Palliative Care, 37(3), 341–351. 10.1177/0825859720951661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciatore J., Thieleman K., Fretts R., Jackson L. B. (2021). What is good grief support? Exploring the actors and actions in social support after traumatic grief. PLoS One, 16(5), e0252324. 10.1371/journal.pone.0252324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2004). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis (2nd ed.). Los Angeles Sage. [Google Scholar]

- De Bal N., Dierckx de Casterlé B., De Beer T., Gastmans C. (2006). Involvement of nurses in caring for patients requesting euthanasia in Flanders (Belgium): A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43(5), 589–599. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Laat M., De Coninck C., Derycke N., Huysmans G., Coupez V. (2018). Richtlijn Uitvoering euthanasie. www.pallialine.be [Google Scholar]

- Denier Y., Dierckx de Casterlé B., De Bal N., Gastmans C. (2009). Involvement of nurses in the euthanasia care process in Flanders (Belgium): An exploration of two perspectives. Journal of Palliative Care, 25(4), 264–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg R., Nissim R., An E., Hales S. (2021). Impact of medical assistance in dying (MAiD) on family caregivers. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 11(1), 107–114. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hales B. M., Bean S., Isenberg-Grzeda E., Ford B., Selby D. (2019). Improving the medical assistance in dying (MAID) process: A qualitative study of family caregiver perspectives. Palliative & Supportive Care, 17(5), 590–595. 10.1017/s147895151900004x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamarat N., Pillonel A., Berthod M. A., Castelli Dransart D. A., Lebeer G. (2021). Exploring contemporary forms of aid in dying: An ethnography of euthanasia in Belgium and assisted suicide in Switzerland. Death Studies, 46(7), 1–15. 10.1080/07481187.2021.1926635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashemi N., Amos E., Lokuge B. (2021). Quality of bereavement for caregivers of patients who died by medical assistance in dying at home and the factors impacting their experience: A qualitative study. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 24(9), 1351–1357. 10.1089/jpm.2020.0654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway I., Galvin K. (2016). Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare (4th ed. ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson P., Hall C., Boughey A., Roulston A. (2018). Bereavement support standards and bereavement care pathway for quality palliative care. Palliative & Supportive Care, 16(4), 375–387. 10.1017/s1478951517000451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inghelbrecht E., Bilsen J., Mortier F., Deliens L. (2010). The role of nurses in physician-assisted deaths in Belgium. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 182(9), 905–910. 10.1503/cmaj.091881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly B., Handley T., Kissane D., Vamos M., Attia J. (2020). An indelible mark” the response to participation in euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among doctors: A review of research findings. Palliative & Supportive Care, 18(1), 82–88. 10.1017/s1478951519000518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kustanti C. Y., Fang H.-F., Linda Kang X., Chiou J.-F., Wu S.-C., Yunitri N., Chou K.-R. (2021). The Effectiveness of bereavement support for Adult family caregivers in palliative care: A Meta-analysis of Randomized controlled Trials. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 53(2), 208–217. 10.1111/jnu.12630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEIF . (2020). Leifdraad: Leidraad voor artsen bij het zorgvuldig uitvoeren van euthanasie. LEIF. https://leif.be/professionele-info/professionele-leidraad/ [Google Scholar]

- LEIF . (2023). Hulp bij zelfdoding. LEIF. https://leif.be/vragen-antwoorden/hulp-bij-zelfdoding/ [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenthal W. G., Burke L. A., Neimeyer R. A. (2011). Religious coping and meaning-making following the loss of a loved one. Counselling and Spirituality/Counseling et Spiritualité, 30(3), 113–135. [Google Scholar]

- Maher C., Hadfield M., Hutchings M., de Eyto A. (2018). Ensuring Rigor in Qualitative Data Analysis: A Design Research Approach to Coding Combining NVivo With Traditional Material Methods. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 10.1177/1609406918786362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morse J. M. (2004). Theoretical saturation. In Lewis-Beck M. S., Bryman A., Liao T. F. (Eds), The Sage Encyclopedia of social science research methods (pp. 1123–1123). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mortari L. (2015). Reflectivity in research practice:an Overview of different perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(5), 34. 10.1177/1609406915618045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mroz S., Dierickx S., Deliens L., Cohen J., Chambaere K. (2021). Assisted dying around the world: A status quaestionis. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 10(3), 3540–3553. 10.21037/apm-20-637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oczkowski S. J. W., Crawshaw D. E., Austin P., Versluis D., Kalles-Chan G., Kekewich M., Frolic A. (2021). How can we improve the experiences of patients and families who request medical assistance in dying? A multi-centre qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care, 20(1), 185. 10.1186/s12904-021-00882-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J., Jordan J., Prior L., Parkes J. (2011). Living through the death of a child: A qualitative study of bereaved parents’ experiences. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(11), 1384–1392. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roest B., Trappenburg M., Leget C. (2019). The involvement of family in the Dutch practice of euthanasia and physician assisted suicide: A systematic mixed studies review. BMC Medical Ethics, 20(1), 23. 10.1186/s12910-019-0361-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savin-Baden M., Major C.H. (2013). Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice. Great Britain TJ International Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Smolej E., Malozewski M., McKendry S., Diab K., Daubert C., Farnum A., Cameron J. I. (2022). A qualitative study exploring family caregivers' support needs in the context of medical assistance in dying. Palliative & Supportive Care, Online ahead of print. 10.1017/s1478951522000116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe M. S., Stroebe W. (1990). Who participates in bereavement research? A review and empirical study. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 20(1), 1–29. 10.2190/C3JE-C9L1-5R91-DWDU [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swarte N. B., van der Lee M. L., van der Bom J. G., van den Bout J., Heintz A. P. (2003). Effects of euthanasia on the bereaved family and friends: A cross sectional study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 327(7408), 189. 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangarasa T., Hales S., Tong E., An E., Selby D., Isenberg-Grzeda E., Nissim R. (2022). A race to the end: Family caregivers' experience of medical assistance in dying (MAiD)-a qualitative study. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 37(4), 809–815. 10.1007/s11606-021-07012-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treml J., Schmidt V., Nagl M., Kersting A. (2021). Pre-loss grief and preparedness for death among caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients: A systematic review. Social science & medicine, (1982), 284(3), 114240. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Marwijk H., Haverkate I., van Royen P., The A. M. (2007). Impact of euthanasia on primary care physicians in The Netherlands. Palliative Medicine, 21(7), 609–614. 10.1177/0269216307082475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdery A. M., Smith-Greenaway E., Margolis R., Daw J. (2020). Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier applied to the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(30), 17695–17701. 10.1073/pnas.2007476117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh F. (2020). Loss and resilience in the time of COVID-19: Meaning making, hope, and transcendence. Family process, 59(3), 898––911. 10.1111/famp.12588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan H., Bytautas J., Isenberg S. R., Kaplan A., Hashemi N., Kornberg M., Hendrickson T. (2022). Grief and bereavement of family and friends around medical assistance in dying: Scoping review. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. Online ahead of print. 10.1136/spcare-2022-003715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Relatives’ Experiences of Being Involved in Assisted Dying: A Qualitative Study by Charlotte Boven, Let Dillen, Sigrid Dierickx, Lieve Van den Block, Ruth Piers, Nele Van Den Noortgate, and Liesbeth Van Humbeeck in Qualitative Health Research.