Abstract

Background

Dietary patterns can impact the trajectories of healthy aging. However, dietary assessment tools can be challenging to use. With the increased use of technology in older adults, we aimed to evaluate the feasibility of older adults completing the online, Automated Self-Administered 24-h (ASA-24) dietary assessment tool.

Methods

We conducted a randomized, two-period, two-sequence, crossover design of twenty community-dwelling older adults (≥65 years) comparing their preference for completing the ASA-24 alone versus with a research assistant (RA). Participants were recruited via ResearchMatch.com and randomly allocated 1:1 to a sequence of completing both an ASA-24 alone or with an RA, separated by one week. After each session, participants completed an online 11-item feasibility survey (Likert-scale range of 1–5, strongly disagree to strongly agree). Mean and standard deviations were reported for each question.

Results

Mean age was 69 ± 3.5 years (90% females), with no differences were observed for sex, age, race, ethnicity, education, or income. Neither group felt a need for RA assistance (p = 0.34). However, both groups felt the system was easier to follow with the help of an RA (RA: 4.4 ± 1.3, vs. SA 4.6 ± 0.5, p = 0.65), particularly when they completed the ASA-24 alone, first (p = 0.04). When conducting the ASA-24 alone, there was less confidence the system could be learned quickly (SA 4.5 ± 0.5→3.4 ± 1.0 vs RA 3.4 ± 1.0→3.4 ± 0.7, p = 0.001). The ASA-24 was thought to be less cumbersome after repeated exposure in those concluding with the RA.

Conclusion

While older adults were able to complete the ASA-24 independently, the use of an RA led to improved confidence. Enhancing the sample diversity in a larger number of participants could provide helpful data to improve the science of dietary assessment.

Keywords: telehealth, telemedicine, diet, lifestyle, older adult, personalized medicine, self-efficacy

Introduction

Low-quality dietary patterns may be associated with chronic disease development and health trajectories across the lifespan. Previous literature suggests that certain dietary patterns influence the course of chronic diseases and serve as way to mitigate chronic disease development and progression.1,2 For older adults, certain healthy dietary patterns significantly influence the development of chronic diseases such as dementia, frailty, and obesity.1,3,4 For example, older adults in a prospective cohort study incorporating the Mediterranean-Dash Diet Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay (MIND) dietary patterns had less risk of developing dementia over time.5,6 Particular dietary components such as nuts, berries, leafy green vegetables, olive oil and legumes were associated with better cognitive performance and weight loss.5,6 Monitoring the impact of dietary patterns across the lifespan is necessary to improve individualized interventions and positively impact older adults’ health.

Existing methods to assess dietary patterns include food diaries, food-frequency questionnaires, and dietary recalls, such as the Automated Self-Administered (ASA-24) Dietary Assessment Tool. The ASA-24 is a validated method of assessing the dietary patterns of older adults and though it is meant to be self-administered, previous research experiences demonstrated the need for a skilled interviewer to administer the assessment.7–9 Despite older adults’ increasing use of technology-based platforms for health care, little is known about their preferences surrounding the use of web-based dietary assessments.10–12 The purpose of this study was to gain preliminary data on older adults’ perceptions surrounding completion of a web-based ASA-24 independently and with the assistance of an RA. We hypothesized that older adults will prefer to have assistance when completing the web-based ASA-24 platform.

Methods

Study setting and design

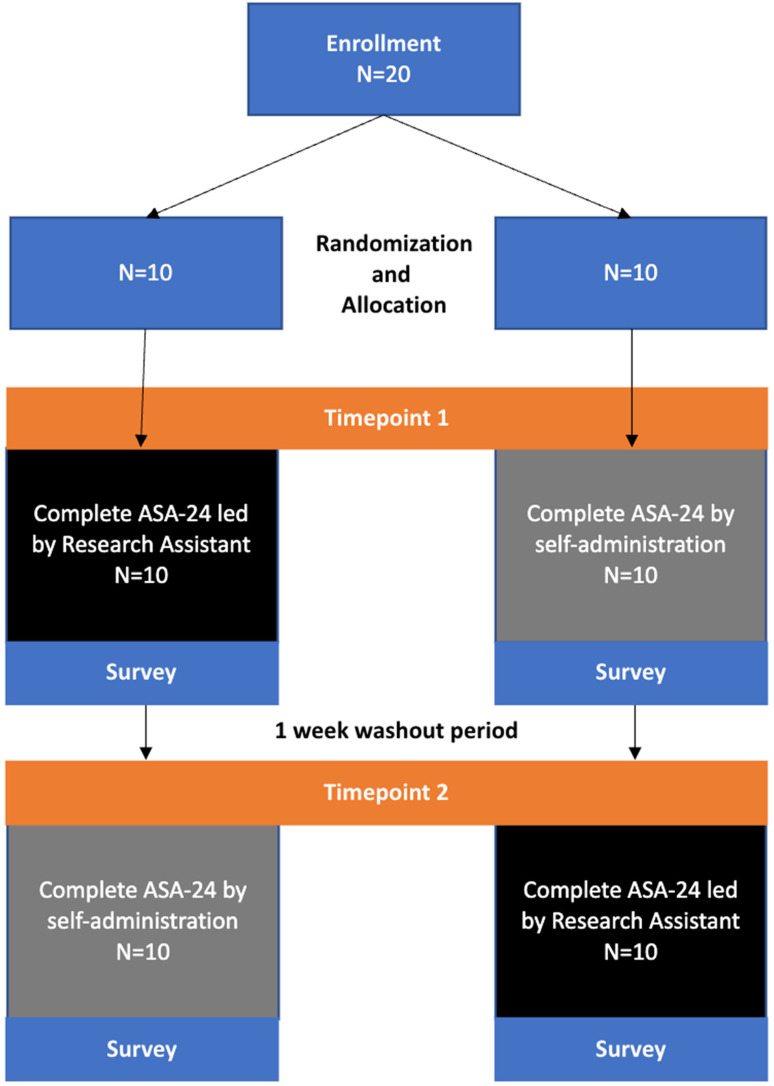

After informed consent, we conducted a randomized, two-period, two-sequence, crossover design of 20 community-dwelling older adults, aged 65 years and older (Figure 1) at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill between October and November 2021. The study was conducted remotely utilizing a video chat platform. It was approved by the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill's Institutional Review Board (number 21-2034).

Figure 1.

Study design: Participants (n = 20) were randomized to a specific sequence: (left) complete the ASA-24 led by the research assistant followed by self-administration; (right) complete the reverse sequence. One week after completion of the first ASA-24, each group completed the ASA-24 using the alternative method. A post-completion survey assessing method preference was conducted after each ASA-24 administration.

Participant recruitment

Participants (n = 20) were recruited via ResearchMatch.org, a secure online recruitment platform. 13 All participants included in this study were 65 years or older, had internet access, and completed all study surveys. All participants completed an online consent process prior to enrollment in the study.

Randomizations

Participants were randomly allocated to a two-period, two-sequence, crossover design. The AB group (n = 10) completed the research assistant (RA) led ASA-24 session, followed by a 1-week washout and completion of the ASA-24 independently. The BA group (n = 10) completed the ASA-24 independently, followed by a 1-week washout and completion of the RA-led ASA-24 session. This paralleled the formative studies conducted on the ASA-24.7,14 All participants were randomly assigned to the AB or BA group.

Study measures

Our main outcome of interest was older adults’ perceptions of ASA-24 completion. The ASA-24 is a validated survey capturing 24 h of intake for the previous day (00:00 to 23:59) via participant recall on a web-based platform. 15 As mentioned previously, each participant completed the ASA-24 independently and with the assistance of the RA. Each RA-led ASA-24 session was one-on-one and took place via Zoom, with the RA reading the ASA-24 survey questions aloud and filling out the ASA-24 answers on behalf of the participant (Figure 1). After completion of each ASA-24 method, participants completed a computer-based survey assessing perceived difficulty of completing the ASA-24 (Figure 1). The survey following the RA-led ASA-24 included 11 questions using a Likert scale (ranging 1–5, strongly disagree to strongly agree, with 3 being neutral) to assess perceived difficulty or ease of completion (Tables 2 and 3). The survey following the independently completed ASA-24 included the same 11 questions, but also asked the participants to rate their self-reported difficulty in completing the ASA-24 independently (1 = very difficult, 2 = difficult, 3 = easy, 4 = very easy). All self-reported demographic information (age, sex, race, ethnicity, education level, and income) and survey responses were collected and stored in REDCap.16,17

Table 2.

Difficulty in using the ASA-24.

| Randomization Sequence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questions | Research Assistant then Self-administration (AB group) | Self-administration then Research Assistant (BA group) | p-value d | |

| I found the ASA-24 system unnecessarily complex a | Timepoint 1 | 2.9 ± 1.4 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | |

| Timepoint 2 | 2.8 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 1.4 | ||

| Delta c | −0.1 ± 1.2 | 0.2 ± 0.8 | 0.50 | |

| P-value | 0.78 | 0.44 | ||

| I thought there was too much inconsistency in the ASA-24 system | Timepoint 1 | 1.6 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 1.1 | |

| Timepoint 2 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | ||

| Delta | 0.4 ± 0.9 | −0.7 ± 1.0 | 0.06 | |

| P-value | 0.17 | 0.07 | ||

| I found the system very cumbersome | Timepoint 1 | 2.1 ± 1.2 | 2.7 ± 1.3 | |

| Timepoint 2 | 2.7 ± 1.5 | 1.9 ± 1.0 | ||

| Delta | 0.6 ± 1.0 | −0.8 ± 1.0 | 0.01 | |

| P-value | 0.08 | 0.04 | ||

| I needed to learn a lot of things before I could get going with this system | Timepoint 1 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | |

| Timepoint 2 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | ||

| Delta | 0.2 ± 0.7 | −0.5 0.7 | 0.11 | |

| P-value | 0.34 | 0.10 | ||

| How difficult was the self-administered ASA-24 to complete b | Timepoint 1 | – | – | – |

| Timepoint 2 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 3.0 ± 2.3 | 0.54 | |

Continuous variables are represented as mean ± standard deviation.

Likert scale 1 (strongly disagree), 3 (neutral), to 5 (strongly agree).

Likert scale 1 (very difficult) to 4 (very easy).

Delta: Difference in mean scores between first and second timepoint for each group (within group difference).

Between group differences.

Table 3.

Ease in using the ASA-24 dietary assessment.

| Randomization Sequence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questions a | Research Assistant then Self-administration (AB group) | Self-administration then Research Assistant (BA group) | p- Value c | |

| I think that I would like to use the ASA-24 system frequently | Timepoint 1 | 3.1 ± 1.7 | 2.9 ± 1.4 | |

| Timepoint 2 | 3.3 ± 1.3 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | ||

| Deltab | 0.2 ± 1.3 | 0.5 ± 1.1 | 0.59 | |

| P-value | 0.64 | 0.18 | ||

| I thought the ASA-24 system was easy to follow | Timepoint 1 | 4.4 ± 1.3 | 3.8 ± 1.1 | |

| Timepoint 2 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.5 | ||

| Delta | −0.3 ± 1.1 | 0.8 ± 1.0 | 0.09 | |

| P-value | 0.39 | 0.04 | ||

| I think that I need help from a Research Assistant to be able to use the ASA-24 system | Timepoint 1 | 2.5 ± 1.3 | 1.7 ± 0.8 | |

| Timepoint 2 | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 1.4 | ||

| Delta | −1.1 ± 1.1 | 0.5 ± 0.9 | 0.01 | |

| P-value | 0.02 | 0.10 | ||

| I found the various functions in the ASA-24 system were well integrated | Timepoint 1 | 3.9 ± 0.7 | 3.2 ± 1.3 | |

| Timepoint 2 | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 4.0 ± 1.1 | ||

| Delta | −0.4 ± 0.9 | 0.8 ± 1.4 | 0.09 | |

| P-value | 0.14 | 0.10 | ||

| I would imagine that most people would learn to use this system very quickly | Timepoint 1 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 3.4 ± 1.0 | |

| Timepoint 2 | 3.4 ± 0.7 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | ||

| Delta | −0.6 ± 1.2 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 0.01 | |

| P-value | 0.14 | 0.001 | ||

| I felt confident about the accuracy and completeness of the ASA-24 recall | Timepoint 1 | 3.9 ± 1.3 | 4.3 ± 0.8 | |

| Timepoint 2 | 3.8 ± 1.2 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | ||

| Delta | −0.1 ± 1.1 | 0.1 ± 0.5 | 0.43 | |

| P-value | 0.86 | 0.59 | ||

| I am confident that I am able to conduct the ASA-24 with help, at least three days per week at home | Timepoint 1 | 4.1 ± 1.4 | 4.6 ± 0.7 | |

| Timepoint 2 | 4.4 ± 0.8 | 4.4 ± 1.1 | ||

| Delta | 0.3 ± 1.6 | −0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.21 | |

| P-value | 0.54 | 0.56 | ||

Continuous variables are represented as mean ± standard deviation.

Likert scale 1 (strongly disagree), 3 (neutral), to 5 (strongly agree).

Delta: Difference in mean scores between first and second timepoint for each group (within group difference).

Between group differences.

Statistical analysis

The mean and standard deviation were reported for all quantitative data. Paired and unpaired t-tests of unequal variance compared continuous variables and Chi-squared for categorical de-identified variables using Microsoft Excel v.16.69.1 (Redmond, Washington). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Participant demographics of the two randomization sequences are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences observed between groups for sex, age, race, ethnicity, education, or income. Table 2 presents information on the difficulty in using the ASA-24 by randomization sequence. Overall, both groups had neutral feelings in the complexity of the ASA-24. We observed a trend suggesting that participants felt there were less inconsistencies with an RA-led ASA-24 session compared to independently completing the ASA-24. The ASA-24 was believed to be less cumbersome after repeated exposure (timepoint 2) for participants who completed the RA-led ASA-24 session last (group BA). Participants had neutral impressions regarding the difficulty of using the ASA-24. Generally, for all questions regarding ASA-24 difficulty, repeated exposure did not improve self-reported difficulty for participants who completed the RA-led ASA-24 session first (group AB).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled older adults aged ≥65 years.

| Randomization sequence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Research Assistant then self-administration (AB group) | Self-administration then Research Assistant (BA group) | p-value | |

| N = 10 | N = 10 | ||

| Age, years | 69.0 ± 4.0 | 68 ± 2.6 | 0.13 |

| Female Sex | 8 (80%) | 10 (100%) | 0.14 |

| Education | 0.50 | ||

| Some College | 0 (0%) | 1 (10%) | |

| College Degree | 6 (60%) | 4 (40%) | |

| Post-college degree | 4 (40%) | 5 (50%) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 10 (100%) | 10 (100%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.30 | ||

| Hispanic/Latino | 0 (0%) | 1 (10%) | |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 10 (100%) | 9 (90%) | |

| Income | 0.13 | ||

| $0–24,999 | 1 (10%) | 1 (10%) | |

| $25,000–49,999 | 1 (10%) | 2 (20%) | |

| $50,000–74,999 | 1 (10%) | 2 (20%) | |

| $75,000–99,999 | 3 (30%) | 0 (0%) | |

| $100,000+ | 2 (20%) | 5 (50%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (20%) | 0 (0%) | |

Continuous variables are represented as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables are represented by a count (percent).

Participants that completed the RA-led ASA-24 first (group AB) reported a decreased need for RA assistance when completing the ASA-24 (Table 3). While both groups felt that the ASA-24 was easy to follow, older adults’ learnability changed because of their initial randomization – those concluding with the RA felt the ASA-24 was easier to follow. Additionally, both groups did not feel that they needed RA assistance and felt more strongly that they could complete the ASA-24 three times a week after self-administration. Both groups were confident in the accuracy and completeness of the ASA-24. Overall, there were inconsistent changes in perceptions of ASA-24 ease with repeated exposure for both groups, although not reaching statistical significance outside of the previously discussed questions in Table 3.

Discussion

We aimed to evaluate the feasibility of older adults completing the online, Automated Self-Administered 24-h (ASA-24) dietary assessment tool. Our findings suggest that while older adults can complete the ASA-24 using an online platform on their own, assistance may improve feasibility of use. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess the preference of online dietary recall platforms in older adults which may have implications for future clinical care and research.

We did observe inconsistencies in both administration sequences regarding preferred ASA-24 method of completion, as trends in learnability differed based on the initial randomization sequence. While both sequences felt the ASA-24 was easily followed and more quickly learned with the RA, both groups did not feel that they needed RA assistance and felt more strongly that they could complete the ASA-24 three times a week after self-administration. These preferences for ASA-24 self-administration may suggest that completion may be feasible in their daily lives. Though not directly observed in our study, we suspect there may be a number of factors that explain these preliminary findings. These sentiments may be in part due to older adults not wanting to burden others with their needs and desiring to maintain a sense of independence with aging.18–20 A desire for independence may lead to less interactions with the health care system and worsen health outcomes for aging adults. 18 Furthermore, more likely, we enrolled a cohort that may have an element of technology literacy.

Despite participants’ preferences to maintain autonomy while using the online ASA-24 platform, the influence of repetitive use did not seem to consistently influence comfort with the ASA-24 for either method. Yet, those receiving RA assistance on the second administration, tended to favor a desire for RA assistance. Although this was not directly assessed within our study, based on our participants’ preferences for RA assistance, we speculate these preferences may be impacted by the length and cumbersome nature of the ASA-24 as well as the potential influence of recent RA assistance (and preference). Shorter surveys may be better received by older adults when completing health surveys on their own and or at least one introduction to the ASA-24 should involve the RA. Ettienne-Gittens et al. similarly observed older adult (>72 years old) frustration with the length of ASA-24 and preference for assistance with the technological-based platform, which may suggest that older adults need tailored dietary recall platforms. 7 This is also supported by our findings that older adults felt the ASA-24 was more easily completed after receiving RA assistance. This may indicate that older adults need at least an assisted introduction to the ASA-24 prior to independent use.

A strength of this study includes the novelty of assessing older adults’ perceptions of an online dietary recall platform, as this has not been extensively studied in older adults. Our findings support efforts for technology-based assessments that may increase access to health care access and interventions for older adults with transportation limitations. Limitations of this study include the small sample size lacking heterogeneity, limiting the analyses (e.g., impact of method order on preference) and larger application, respectively. Though some changes in scores were statistically significant, it is difficult to draw conclusions about clinical significance due to small sample size and lack of previous literature for comparison. Additionally, repeated use based on the survey design may have led to improved usability as one week may not be an adequate washout period. Our analyses are also limited by the lack of validation analyses for our survey. Additionally, because our online platform does remove the typical ASA-24 interviewer for the assessment, this may decrease validity of the ASA-24 as the ASA-24 is usually administered by a trained administrator. Time for completion of either method, baseline technological literacy, and additional survey validation procedures need to be considered in future studies.

Conclusion

An online platform for the ASA-24 dietary recall may be a feasible method to assess older adult dietary preferences, and potentially more so when receiving assistance. While older adults desired autonomy in conducting this assessment, the inconsistencies in preference may suggest that receiving assistance with ASA-24 completion may lead to better healthcare accessibility. Though limited population heterogeneity, our study provides information on best practices for assessing older adults’ dietary patterns using an online platform that may influence aging and chronic disease trajectories.

Footnotes

Contributorship: Hillary Spangler performed analysis of the data, wrote the manuscript, and provided manuscript revisions.

Tiffany Driesse and Michael Fowler participated in recruitment, data collection, analysis of the data and revisions of the manuscript.

David Lynch and Danae Gross provided revisions for the manuscript.

Curtis Peterson participated in the analysis and revisions of the manuscript.

Xiaohui Liang and John Batsis developed the project concept and provided manuscript revisions.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: This study was approved the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill's Institutional Review Board.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was made possible by National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging, (grant number R01AG067416) and NC Translational and Clinical Science Pilot Awardee (grant number #2KR1442102).

Guarantor: John Batsis, MD.

ORCID iD: Hillary B. Spangler https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4027-4113

References

- 1.English LK, Ard JD, Bailey RL, et al. Evaluation of dietary patterns and all-cause mortality: a systematic review. JAMA Network Open 2021; 4: e2122277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Govindaraju T, Sahle BW, McCaffrey TA, et al. Dietary patterns and quality of life in older adults: a systematic review. Nutrients 2018; 10. doi: 10.3390/nu10080971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.León-Muñoz LM, García-Esquinas E, López-García E, et al. Major dietary patterns and risk of frailty in older adults: a prospective cohort study. BMC Med 2015; 13: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen X, Liu Z, Sachdev PS, et al. Dietary patterns and cognitive health in older adults: findings from the Sydney memory and ageing study. J Nutr Health Aging 2021; 25: 255–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arjmand G, Abbas-Zadeh M, Eftekhari MH. Effect of MIND diet intervention on cognitive performance and brain structure in healthy obese women: a randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep 2022; 12: 2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Crom TOE, Mooldijk SS, Ikram MK, et al. MIND Diet and the risk of dementia: a population-based study. Alzheimers Res Ther 2022; 14: 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ettienne-Gittens R, Boushey CJ, Au D, et al. Evaluating the feasibility of utilizing the Automated Self-administered 24-hour (ASA24) dietary recall in a sample of multiethnic older adults. Procedia Food Sci 2013; 2: 134–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moshfegh AJ, Rhodes DG, Baer DJ, et al. The US department of agriculture automated multiple-pass method reduces bias in the collection of energy intakes. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 88: 324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ralph JL, Ah V, Scheett D, et al. Diet assessment methods: a guide for oncology nurses. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2011; 15: E114–E121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gregorič M, Zdešar Kotnik K, Pigac Iet al. et al. A web-based 24-h dietary recall could be a valid tool for the indicative assessment of dietary intake in older adults living in Slovenia. Nutrients 2019; 11. doi: 10.3390/nu11092234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spangler HB, Driesse TM, Lynch DH, et al. Privacy concerns of older adults using voice assistant systems. J Am Geriatr Soc 2022; 70: 3643–3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subar AF, Potischman N, Dodd KW, et al. Performance and feasibility of recalls completed using the automated self-administered 24-hour dietary assessment tool in relation to other self-report tools and biomarkers in the interactive diet and activity tracking in AARP (IDATA) study. J Acad Nutr Diet 2020; 120: 1805–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ResearchMatch. Vanderbilt University, 2023.

- 14.Wei C, Wagler JB, Rodrigues IB, et al. Telephone administration of the automated self-administered 24-h dietary assessment in older adults: lessons learned. Can J Diet Pract Res 2022; 83: 30–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Automated self-administered 24-h (ASA24®) dietary assessment tool. National Institutes of Health, 2023.

- 16.REDCap. NC TraCS Institute, 2023.

- 17.North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute (NC TraCS). UNC School of Medicine.

- 18.Cahill E, Lewis LM, Barg FKet al. et al. You don't want to burden them”: older adults’ views on family involvement in care. J Fam Nurs 2009; 15: 295–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Festen S, van Twisk YZ, van Munster BCet al. et al. What matters to you?’ Health outcome prioritisation in treatment decision-making for older patients. Age Ageing 2021; 50: 2264–2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rogers WA, Mitzner TL. Envisioning the future for older adults: autonomy, health, well-being, and social connectedness with technology support. Futures 2017; 87: 133–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]