Abstract

Background

Combined oral contraceptive (COC) use has been associated with venous thrombosis (VT) (i.e., deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism). The VT risk has been evaluated for many estrogen doses and progestagen types contained in COC but no comprehensive comparison involving commonly used COC is available.

Objectives

To provide a comprehensive overview of the risk of venous thrombosis in women using different combined oral contraceptives.

Search methods

Electronic databases (Pubmed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane, CINAHL, Academic Search Premier and ScienceDirect) were searched in 22 April 2013 for eligible studies, without language restrictions.

Selection criteria

We selected studies including healthy women taking COC with VT as outcome.

Data collection and analysis

The primary outcome of interest was a fatal or non‐fatal first event of venous thrombosis with the main focus on deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary embolism. Publications with at least 10 events in total were eligible. The network meta‐analysis was performed using an extension of frequentist random effects models for mixed multiple treatment comparisons. Unadjusted relative risks with 95% confidence intervals were reported.Two independent reviewers extracted data from selected studies.

Main results

3110 publications were retrieved through a search strategy; 25 publications reporting on 26 studies were included. Incidence of venous thrombosis in non‐users from two included cohorts was 0.19 and 0.37 per 1 000 person years, in line with previously reported incidences of 0,16 per 1 000 person years. Use of combined oral contraceptives increased the risk of venous thrombosis compared with non‐use (relative risk 3.5, 95% confidence interval 2.9 to 4.3). The relative risk of venous thrombosis for combined oral contraceptives with 30‐35 μg ethinylestradiol and gestodene, desogestrel, cyproterone acetate, or drospirenone were similar and about 50‐80% higher than for combined oral contraceptives with levonorgestrel. A dose related effect of ethinylestradiol was observed for gestodene, desogestrel, and levonorgestrel, with higher doses being associated with higher thrombosis risk.

Authors' conclusions

All combined oral contraceptives investigated in this analysis were associated with an increased risk of venous thrombosis. The effect size depended both on the progestogen used and the dose of ethinylestradiol. Risk of venous thrombosis for combined oral contraceptives with 30‐35 μg ethinylestradiol and gestodene, desogestrel, cyproterone acetate and drospirenone were similar, and about 50‐80% higher than with levonorgestrel. The combined oral contraceptive with the lowest possible dose of ethinylestradiol and good compliance should be prescribed—that is, 30 μg ethinylestradiol with levonorgestrel.

Plain language summary

Contraceptive pills and venous thrombosis

Contraceptive pills are among the most popular contraception methods worldwide. A combined oral contraceptive pill contains two components, the estrogen and the progestagen compound. Despite its reliable contraception action, these pills may present side‐effects including obstruction of leg and pulmonary vessels by clots (venous thrombosis). This side‐effect is rare but the most frequently occurring serious adverse effect. Different combination pills show different vessel clotting obstruction tendencies (venous thrombosis risk). Evaluation of these different tendencies may play an important role in choosing the safest pill when starting pill use. COC containing higher estrogen doses (>30 μg) with levonorgestrel (a progestagen) or containing cyproterone acetate or drospirenone as progestagen are associated with higher VT risk than the oral contraceptive pill with 30 μg estrogen and levonorgestrel as progestagen. All combined monophasic oral contraceptive pills have the same effectiveness, that is preventing unwanted pregnancies.

Background

Description of the condition

Venous thrombosis comprises deep‐vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism. DVT typically starts in the calf veins, from where it may extend to the proximal veins and subsequently cause pulmonary embolism (Kearon 2003). Approximately one‐third of patients with symptomatic venous thrombosis manifest pulmonary embolism (White 2003; Huerta 2007). Venous thrombosis is associated with genetic (i.e., carriers of thrombophilic disorders and a positive family history for venous thrombosis) and acquired risk factors (i.e., surgery, trauma, marked immobility, pregnancy, hormonal replacement therapy, previous venous thrombotic event, active cancer). In women of reproductive age, an important risk factor is oral contraceptive use. Oral contraceptives and inherited thrombophilic defects (i.e., factor V Leiden mutation, deficiency of protein C, protein S or antithrombin, high levels of factor VIII, and prothrombin mutation) interact synergistically to increase the risk of venous thrombosis (Bloemenkamp 2003; Huerta 2007; Naess 2007).

Venous thrombosis in women has an incidence of 1.6 per 1000 person‐years. Incidence rates increase with age: women aged 30 to 34 years show an incidence of 0.25 per 1000 person‐years and women aged 60 to 64 years, 0.93 per 1000 person‐years (Naess 2007). Others have estimated the incidence in women during the reproductive years to be in the range of 0.5 to 1.0 per 1000 person‐years (Heinemann 2007). Despite the low incidence of venous thrombosis among women of reproductive age, the impact of oral contraceptives on the risk is large since it is estimated that more than 100 million women worldwide use an oral contraceptive (WHO 1998). Moreover, venous thrombosis is associated with an increased mortality risk. Overall, the 30‐day case fatality rate is higher in patients with pulmonary embolism than in those with DVT (9.7% to 12% versus 4.6% to 6%) (White 2003; Huerta 2007; Naess 2007). In women from 15 to 44 years of age the venous thrombosis‐associated mortality rate is lower (0.6% to 1.7%) (Lidegaard 1998b).

DVT may damage deep venous valves with venous reflux and venous hypertension in the lower limbs, resulting in a post‐thrombotic syndrome (PTS). PTS is characterized by pain, heaviness, and swelling of the leg aggravated by standing or walking (Kearon 2003). PTS may develop in half of all DVT patients within three months, with no further increase being seen up to two years of follow‐up (Tick 2010). Complete resolution of pulmonary embolism occurs in about two‐thirds of patients, with partial resolution in the remainder. However, chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension may occur in up to 5% of pulmonary embolism patients (Kearon 2003).

Description of the intervention

The first combined oral contraceptive (COC) was introduced in 1960 (Enovid®). It consisted of 0.15 mg mestranol, an estrogen, and 9.85 mg norethynodrel, a progestogen. Shortly after, the first case of venous thrombosis associated with COC was reported (Jordan 1961). Since then many studies have established the association between COC use and occurrence of venous thrombosis (van Hylckama Vlieg 2011).

Several large studies in the 1990s confirmed a two‐ to four‐fold increase in the risk of venous thrombosis associated with COC use (Thorogood 1992; Vandenbroucke 1994; WHO 1995; Farmer 1997). Since the estrogen compound in COC was thought to cause the increased risk, the dose of estrogen has been gradually lowered from 150 to 100 μg to 20 μg in the 1970s (Stolley 1975; Wharton 1988; Thorogood 1993). The lower dose of ethinylestradiol in contraceptives was indeed associated with a reduction in the venous thrombosis risk (Inman 1970; Meade 1980; Vessey 1986; WHO 1995; Lidegaard 2002). The oral contraceptives currently prescribed which contain 30 μg of ethinylestradiol are associated with a higher risk of venous thrombosis than contraceptives containing 20 μg (Lidegaard 2009; van Hylckama Vlieg 2009).

Besides adjustments in the dose of ethinylestradiol, the progestogen compound was changed to reduce the side effects of the COC. After the first‐generation progestogens, new progestogens were developed in the 1970s and 1980s (second and third‐generation progestogens, respectively). It was shown that third‐generation COC users had a higher risk of venous thrombosis than second‐generation users (Kemmeren 2001; Vandenbroucke 2001; Lidegaard 2009; van Hylckama Vlieg 2009). However, these results were disputed: it was reasoned that bias or confounding could explain the difference in venous thrombosis risk between the progestogen generations. These issues were addressed in an opinion article and a meta‐analysis in which it was shown that the presence of bias or confounding could not explain the observed results (Vandenbroucke 1997; Kemmeren 2001).

Other progestogens have been developed since the introduction of the third‐generation progestogens, i.e., drospirenone (2001) and dienogest (1995). The use of drospirenone in a COC has been shown to increase the risk of venous thrombosis (Lidegaard 2009; van Hylckama Vlieg 2009), compared with non‐use and compared with second‐generation contraceptives (Jick 2011; Parkin 2011). However, no information concerning the risk of venous thrombosis is available for the contraceptive containing dienogest, mainly used in Germany (Kuhl 1998).

How the intervention might work

The use of COCs affects hemostasis in many ways. It increases factors involved in coagulation or indicative of increased activity of this system (i.e., factor II, factor VII, and factor VIII, prothrombin fragment 1+2, D‐Dimer). Natural anticoagulant factors are also affected, for example, the anticoagulant protein C is increased whereas other anticoagulation factors are decreased (i.e., antithrombin and protein S) in COC users. This trend is more pronounced in third‐generation COC users than in second‐generation users (Vandenbroucke 2001; Kemmeren 2002a; Kemmeren 2002b; Kemmeren 2004).

Besides these individual coagulation factors, the measurement of activated protein C (APC) resistance provides insight into the overall balance of coagulation (Vandenbroucke 2001). There are two APC resistance assays for probing the plasma response to APC (the endogenous thrombin potential assay and the activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT)‐based assay). The two assays rely on different coagulation triggers and endpoints and they probe different coagulation reactions. In summary, APC resistance evaluates the relative inability of protein C to cleave activated factors V and VIII leading to a prothrombotic state (Vandenbroucke 2001; Castoldi 2010). APC resistance predicts venous thrombosis risk in men and in women, as well as in COC users and non‐users (Tans 2003). Several studies have confirmed that APC resistance is increased in COC users (Kemmeren 2004; Rad 2006; Kluft 2008) and the effect is more pronounced in users of a third‐generation progestogen than with a second‐generation progestogen (Kemmeren 2004).

Why it is important to do this review

Since the introduction of the third‐generation progestogens, new progestogens have been introduced, such as nestorone, dienogest, nomegestrol acetate and spirolactone derivates, trimegestone, and drospirenone (Sitruk‐Ware 2006). Many studies compare these new COCs to a COC containing levonorgestrel, which is assumed to have the lowest risk of venous thrombosis (Gomes 2004; Jick 2011; Lidegaard 2011). We set out to review the association between COC and risk of venous thrombosis at the level of different COCs, including the potential risk associated with COCs containing new progestogens. Specifically, we performed a network meta‐analysis to compare one COC to another or to non‐use. Network meta‐analysis allows not only the comparison of two treatments but also a simultaneous comparison of several competing treatments, even where few or no direct comparisons exist. In addition, assessment of effect may be more realistic because it is based on a much larger body of evidence than in conventional meta‐analysis (Jansen 2008; Thijs 2008). In this network analysis we took into account not only the progestogen used in the COC but also the estrogen dose. The rationale of the present systematic review is to provide an update on the venous thrombosis risk associated with COC formulations and to perform a network meta‐analysis on the estrogen dosage and progestogen component of COCs.

The systematic review protocol was established before we developed the review that was published in September 2013 (Stegeman 2013). Reasons for not publishing the protocol before publication of the review were publication rights and unity between the protocol and The Cochrane Library/BMJ review. For abbreviations, we refer to Table 1.

1. Abbreviations.

| Specific abbreviations | Explanation |

| APC | Activated protein C |

| APTT | Activated partial thromboplastin time |

| C | Cohort study |

| CC | Case‐control study |

| COC | Combined oral contraceptive |

| CT | Computed axial tomography |

| DVT | Deep‐vein thrombosis |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| NA | Not applicable |

| NCC | Nested case‐control study |

| PCS | Prospective cohort study |

| PTS | Post‐thrombotic syndrome |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trial |

| V/Q | Ventilation‐perfusion |

| 20LNG | 20 μg ethinylestradiol with levonorgestrel |

| 30LNG | 30 μg ethinylestradiol with levonorgestrel |

| 50LNG | 50 μg ethinylestradiol with levonorgestrel |

| 20GSD | 20 μg ethinylestradiol with gestodene |

| 30GSD | 30 μg ethinylestradiol with gestodene |

| 20DSG | 20 μg ethinylestradiol with desogestrel |

| 30DSG | 30 μg ethinylestradiol with desogestrel |

| 35NRG | 35 μg ethinylestradiol with norgestimate |

| 35CPA | 35 μg ethinylestradiol with cyproterone acetate |

| 30DRSP | 30 μg ethinylestradiol with drospirenone |

Objectives

The objectives of this review are:

to estimate venous thrombosis risk associated with COC use compared with non‐use;

to perform a network comparison of the risk associated with the three generations of COCs;

to compare the effect of estrogen doses and types of progestogen on venous thrombosis risk.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Observational studies on adverse effects may provide valid evidence on unintended effects of treatment as they are often unpredictable and not linked to indications for treatment (Vandenbroucke 2004; Vandenbroucke 2006; Vandenbroucke 2008). Empirical evidence suggests that there may be no difference on average in side effects risk estimates of an intervention derived from meta‐analyses of randomized controlled trials (RCT) and meta‐analyses of observational studies. Therefore it seems reasonable not to restrict systematic reviews of adverse effects only to a specific study type (Golder 2011) and also because there is a paucity of experimental data on side effects. Thus, systematic reviews on the harms of interventions often come from observational studies. Observational studies in this review included case‐control, cohort, and nested case‐control designs. If available, RCTs would also be evaluated and included. Study design criteria are described in Table 2 and Table 3.

2. List of study design features.

| Question and checklist | RCT | PCS | RCS | NCC | CC |

| Was there a comparison: | |||||

| Between two or more groups of participants receiving different interventions? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Within the same group of participants over time? | P | N | N | N | N |

| Were participants allocated to groups by: | |||||

| Concealed randomization? | Y | N | N | N | N |

| Quasi‐randomization? | N | N | N | N | N |

| Other action of researchers? | N | N | N | N | N |

| Time differences? | N | N | N | N | N |

| Location differences? | N | P | P | NA | NA |

| Treatment decisions? | N | P | P | N | N |

| Participants' preferences? | N | P | P | N | N |

| On the basis of outcome? | N | N | N | Y | Y |

| Some other process? (specify) | |||||

| Which parts of the study were prospective: | |||||

| Identification of participants? | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Assessment of baseline and allocation to intervention? | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Assessment of outcomes? | Y | Y | P | Y | N |

| Generation of hypotheses? | Y | Y | Y | Y | P |

| On what variables was comparability between groups assessed: | |||||

| Potential confounders? | P | P | P | P | P |

| Baseline assessment of outcome variables? | P | P | P | N | N |

RCT = randomized clinical trial PCS = prospective cohort study RCS = retrospective cohort study NCC = nested case‐control study CC = case‐control study Y = yes N = no P = possibly NA = not applicable

3. Checklist for data collection/study assessment.

|

Note: Users need to be very clear about the way in which the terms 'group' and 'cluster' are used in these tables. The above table only refers to groups, which is used in its conventional sense to mean a number of individual participants. With the exception of allocation on the basis of outcome, 'group' can be interpreted synonymously with 'intervention group'. Although individuals are nested in clusters, a cluster does not necessarily represent a fixed collection of individuals. For instance, in cluster‐allocated studies, clusters are often studied at two or more time points (periods) with different collections of individuals contributing to the data collected at each time point. Was there a comparison? Typically, researchers compare two or more groups that receive different interventions; the groups may be studied over the same time period, or over different time periods (see below). Sometimes researchers compare outcomes in just one group but at two time points. It is also possible that researchers may have done both, i.e., studying two or more groups and measuring outcomes at more than one time point. How were participants/clusters allocated to groups? These items aim to describe how groups were formed. None will apply if the study does not compare two or more groups of participants. The information is often not reported or is difficult to find in a paper. The items provided cover the main ways in which groups may be formed. More than one option may apply to a single study, although some options are mutually exclusive (i.e., a study is either randomized or not). ‐ Randomization: Allocation was carried out on the basis of truly random sequence. Check carefully whether allocation was adequately concealed until participants were definitively recruited. ‐ Quasi‐randomization: Allocation was done on the basis of a pseudo‐random sequence, e.g., odd/even hospital number or date of birth, alternation. Note: when such methods are used, the problem is that allocation is rarely concealed. ‐ By other action of researchers: this is a catch‐all category and further details should be noted if the researchers report them. Allocation happened as the result of some decision or system applied by the researchers. For example, participants managed in particular 'units' of provision (e.g. wards, general practices) were 'chosen' to receive the intervention and participants managed in other units to receive the control intervention. ‐ Time differences: Recruitment to groups did not occur contemporaneously. For example, in a historically controlled study participants in the control group are typically recruited earlier in time than participants in the intervention group; the intervention is then introduced and participants receiving the intervention are recruited. Both groups are usually recruited in the same setting. If the design was under the control of the researchers, both this option and 'other action of researchers' must be ticked for a single study. If the design 'came about' by the introduction of a new intervention, both this option and 'treatment decisions' must be ticked for a single study. ‐ Location differences: Two or more groups in different geographic areas were compared, and the choice of which area(s) received the intervention and control interventions was not made randomly. So, both this option and 'other action of researchers' could be ticked for a single study. ‐ Treatment decisions: Intervention and control groups were formed by naturally occurring variation in treatment decisions. This option is intended to reflect treatment decisions taken mainly by the clinicians responsible; the following option is intended to reflect treatment decisions made mainly on the basis of participants' preferences. If treatment preferences are uniform for particular provider 'units', or switch over time, both this option and 'location' or 'time' differences should be ticked. ‐ Patient preferences: Intervention and control groups were formed by naturally occurring variation in patients' preferences. This option is intended to reflect treatment decisions made mainly on the basis of patients' preferences; the previous option is intended to reflect treatment decisions taken mainly by the clinicians responsible. ‐ On the basis of outcome: A group of people who experienced a particular outcome of interest were compared with a group of people who did not, i.e., a case‐control study. Note: this option should be ticked for papers that report analyses of multiple risk factors for a particular outcome in a large series of participants, i.e. in which the total study population is divided into those who experienced the outcome and those who did not. These studies are much closer to nested case‐control studies than cohort studies, even when longitudinal data are collected prospectively for consecutive patients. Which parts of the study were prospective? These items aim to describe which parts of the study were conducted prospectively. In a randomized controlled trial, all four of these items would be prospective. For non‐randomized trials (NRS) it is also possible that all four are prospective, although inadequate detail may be presented to discern this, particularly for generation of hypotheses. In some cohort studies, participants may be identified, and have been allocated to treatment retrospectively, but outcomes are ascertained prospectively. On what variables was comparability of groups assessed? These questions should identify 'before‐and‐after' studies. Baseline assessment of outcome variables is particularly useful when outcomes are measured on continuous scales, e.g., health status or quality of life. Response options Try to use only 'Yes', 'No', and 'Can't tell' response options. 'NA' should be used if a study does not report a comparison between groups. |

Types of participants

Participants were healthy women taking a COC. We excluded studies of women on postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy, studies of women taking non‐oral or progestogen‐only contraceptives, and studies of women with venous thrombosis recurrence.

Types of interventions

COC use was compared with non‐use or with a reference COC (for example, levonorgestrel with 30 μg of ethinylestradiol). We defined a woman as a COC non‐user when either she had never been exposed to a COC or she was a former/previous COC user.

As there is no generally accepted way to classify COC according to generation of progestogen, we classified as 'first‐generation' COCs those including lynestrenol and norethisterone as progestogens. 'Second‐generation' COCs included norgestrel and levonorgestrel, while 'third‐generation' COCs included desogestrel, gestodene, or norgestimate as progestogens. Therefore, we classified COCs by progestogen generation independently of ethinylestradiol dose. Whenever another COC generation classification was employed by the researchers, we also kept the original generation classification data so we could evaluate the effect of COC generation classification on venous thrombosis risk (Henzl 2000; Sitruk‐Ware 2008). We also categorized COCs according to estrogen dose and to progestogen type.

Types of outcome measures

The outcome was fatal or non‐fatal first venous thrombosis event (DVT or pulmonary embolism). We classified outcomes according to diagnostic criteria as:

strict diagnostic outcome and specified criteria for venous thrombosis;

discharge diagnoses from wards, but without a priori specified outcome criteria;

ad hoc outcome selection of venous thrombosis patients not specified in advance.

We included these outcome measures in the data abstraction form and we evaluated them in a sensitivity analysis. The outcome classification was assessed independently by two review authors (MdB, BHS) and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was fatal or non‐fatal first venous thrombosis event (DVT or pulmonary embolism).

Secondary outcomes

Not applicable.

Search methods for identification of studies

The search was created in association with an expert librarian (JW Schoones, Walaeus Library, LUMC, Leiden, NL). The search strategy is shown in Appendix 1.

Electronic searches

We have searched the following databases: the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1988 to 22 April 2013), MEDLINE (1966 to 22 April 2013), EMBASE (1980 to 22 April 2013), Web of Science (1900 to 22 April 2013), CINAHL (1982 to 22 April 2013), Academic Search Premier (1997 to 22 April 2013), and ScienceDirect (1995 to 22 April 2013). We have amended the search strategy for each database. We have not set a language restriction on the study search.

Searching other resources

In addition, we checked the references of the selected studies and of any reviews identified.

Data collection and analysis

We analyzed the study results by comparing the venous thrombosis relative risk between COC users and non‐users and comparing different types and dosing of COC components based on a network meta‐analysis.

We used standard piloted forms for study selection, 'Risk of bias' assessment, and data abstraction. Study selection forms included study identification, inclusion/exclusion criteria, standard study design classification, intervention and outcome evaluation, exposure ascertainment, and completeness of results.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MdB, BHS) independently evaluated the title and abstract of each study in the study search for study retrieval using standard piloted forms and specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements have been resolved by consensus and a third author (OMD) was consulted if disagreement persisted.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (MdB, BHS) independently performed data extraction using standard, piloted forms. We extracted details of methods (i.e., participants, age), intervention/exposure (i.e., hormone type, dosage, exposure ascertainment), study comparison, outcome criteria assessment (as defined in Types of outcome measures section), results (i.e., number of participants, sample size, number of events, adjusted and unadjusted measure of effect, absolute risk evaluation), and other variables (i.e., funding source, first time users). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion and a third author (OMD) was consulted if disagreement persisted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Tools for assessing quality in clinical trials are well‐described but much less attention has been given to similar tools for observational studies. Although the Newcastle‐Ottawa tool is frequently used to assess observational studies, the reliability or validity is unknown (Deeks 2003; Sanderson 2007). Since the Newcastle‐Ottawa tool is not customized for case‐control study designs, and as many case‐control studies of COCs are available, we have customized a version of the Newcastle‐Ottawa tool for the research question (Higgins 2011). According to study design (case‐control or cohort designs), slightly different 'Risk of bias' assessment questions were customized:

For participant selection in case‐control study designs and outcome assessment in cohort study designs, we customized the following question: 'Was there a (pre)defined outcome assessment?' Possible options include 'Venous thrombosis objectively confirmed in all included cases'; 'Not all venous thrombosis objectively confirmed'; and 'Unclear'. The criteria for venous thrombosis objectively confirmed include DVT event diagnosed by plethysmography, ultrasound examination, computed tomographic scanning, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or venography; or when a pulmonary embolism event was diagnosed by ventilation‐perfusion (V/Q) scanning, multidetector helical computed axial tomography (CT), or pulmonary angiography (Goodacre 2006; Qaseem 2007), or by other strict diagnostic and specified criteria for venous thrombosis. Low risk of bias is defined as venous thrombosis reported as objectively confirmed in all cases.

For participant selection in case‐control studies we customized the question: 'Was the control sampling adequate?' Possible options include 'Yes, with controls truly representing the source population (community controls)'; 'No, with controls not representing the source population'; 'Unclear'. In cohort studies we customized the question: 'Was the selection of the non‐exposed cohort adequately performed?' Possible options include 'Drawn from the same community as the exposed cohort'; 'Drawn from a different source'; 'No description of the derivation of the non‐exposed cohort'. This item was assessed when the control or the non‐exposed participants were derived from the same population as the cases or the exposed participants. Low risk of bias is defined as a study with controls or non‐exposed participants sampled from the source population or from the same community as exposed participants, respectively.

For both study designs, we customized a question evaluating whether or not there were adjustments for confounding performed either in the analysis or by design (matching). Low risk of bias is defined as adjustment for age and calendar time.

Regarding exposure evaluation, the customized question for both study designs was: 'Was COC utilization properly assessed?' Possible options for case‐control study designs include 'Database record' (i.e., drug deliverance records); 'Interview not blinded to case/control status'; 'Written self report or medical record only'; and 'No description'. For cohort study designs, the options include: 'Database record' (i.e., COC prescription deliverance records); 'Structured interview with interviewer blinded'; 'Written self report'; and 'No description'. Low risk of bias is defined as a database record selection or written self report in cohort design.

For cohort study designs, we customized a further question regarding the possibility of loss to follow‐up. Possible options include 'complete follow‐up' (i.e., all participants accounted for); 'Participants lost to follow‐up unlikely to introduce bias' (i.e., less than 10% of the trial population lost to follow‐up); 'Follow‐up rate potentially leading to bias' (i.e., more than 10% of the trial population lost to follow‐up); and 'No statement'. So, for this question, the cut‐off point was 10% and low risk of bias is defined as studies with complete or over 90% follow‐up (Kristman 2005).

We did not use the 'Risk of bias' assessment to accept or reject studies. However, we produced a table describing 'Risk of bias' assessment for the included studies. Two independent review authors (MdB, BHS) assessed risk of bias using a standard piloted form. Any persistent disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third author (OMD).

Measures of treatment effect

We extracted effect estimates from observational studies or RCTs. Effect estimates can be either odds ratios (RCT, cohort studies, and case‐control studies) or risk ratios (RCT and cohort studies). We extracted or recalculated accompanying 95% confidence intervals based on standard errors or P values.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was a healthy women using COC specified by ethinylestradiol dose and progestogen type.

Dealing with missing data

The denominator for each outcome in each study was the number of participants minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

For heterogeneity calculation we used the standard deviation/variance of the effect between studies. We explored possible reasons for heterogeneity (i.e., participants and intervention) whenever the number of studies allowed. Study class with 0 (zero) events was inflated to 0.5. Indirect comparisons used a random‐effects model. We considered results heterogeneous whenever homogeneity is unlikely, that is a low P value (< 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using a funnel plot. After visual inspection for asymmetry we used the linear regression test for asymmetry proposed by Egger (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

We calculated the meta‐analysis adjusted odds ratios by pooling adjusted odds ratios from individual studies, weighting individual study results by the inverse of their variance. For included studies, we noted levels of attrition.

When we did not find explanations for heterogeneity, we considered using a random‐effects model with appropriate cautious interpretation. We used tables for graphical representation of the individual study point estimates and their associated 95% CI.

For the network meta‐analysis, we selected study categories for comparisons whenever there was at least one study with a specific comparison between estrogen dose or progestogen type. One can calculate indirect comparisons between two strategies by examining studies that contrast each strategy against a third 'reference' intervention. We first derived pooled estimates from standard direct ('head‐to‐head') comparisons and then undertook indirect comparisons for estrogen dosing and progestogen type evaluations. We estimated the comparisons in a pair‐wise manner combining all direct ('head‐to‐head') and indirect evidence in a single joint analysis (network meta‐analysis), using a log odds model with a random‐effects model. Graphic representation of the results was made by a matrix representing each comparison.

The extent of disagreement between direct and indirect evidence was also quantified by the incoherence of the network (Thijs 2008). We also performed a meta‐analysis comparing COCs by progestogen generation. We performed the statistical analyses, including the network analysis, with a STATA package (Stata 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

To explore substantial heterogeneity, we performed subgroup analysis and sensitivity analysis (study design and funding). Funding is defined as any study receiving money from pharmaceutical companies.

Sensitivity analysis

We carried out sensitivity analyses to explore heterogeneity regarding study design, outcome certainty (venous thrombosis objectively confirmed), and source of funding. To determine the stability of the overall risk estimate, we performed sensitivity analysis in which each design, outcome, and funding source category was individually observed by progestogen generation.

Results

Description of studies

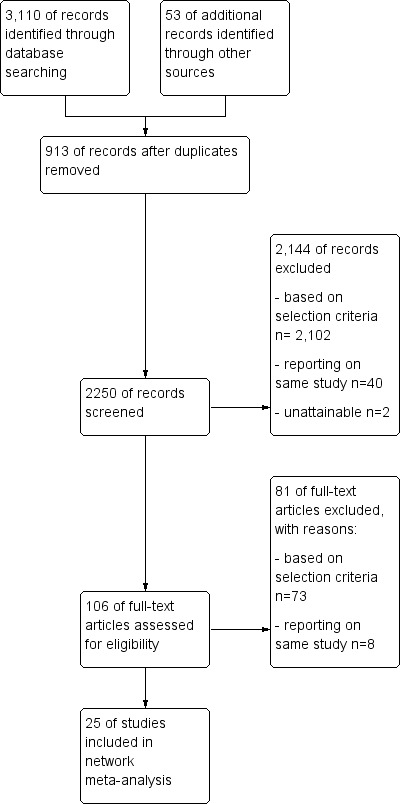

Of 3163 publications retrieved through electronic and references searches, 2144 were excluded after screening the title and abstract and 81 were excluded after detailed assessment of the full text (Figure 1). Overall, 26 studies reported in 25 articles were included (one article (WHO 1995a) presented two studies, see Characteristics of included studies). Two publications provided important additional information to studies included in the meta‐analysis (information on first time use); data from these publications were added to the respective studies already included.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Nine cohort studies, three nested case‐control studies, and 14 case‐control studies were included. Studies were published between 1995 and 2013 and including participants from 1965 to 2009. 19 studies were conducted in Europe, three in the United States of America, one in Israel, one in New Zealand, one in developing countries and one study in several countries across the world. Twelve studies used strict and specific diagnosis criteria for VT events and eight studies were industry‐funded.

Two studies (Lidegaard 2011, Samuelsson 2004) reported the absolute risk of venous thrombosis in non‐users: 0.19 and 0.37 per 1000 woman years. Based on data from 15 studies that included a non‐user group, use of combined oral contraceptives was found to increase the risk of venous thrombosis fourfold (relative risk 3.5, 95% confidence interval 2.9 to 4.3).

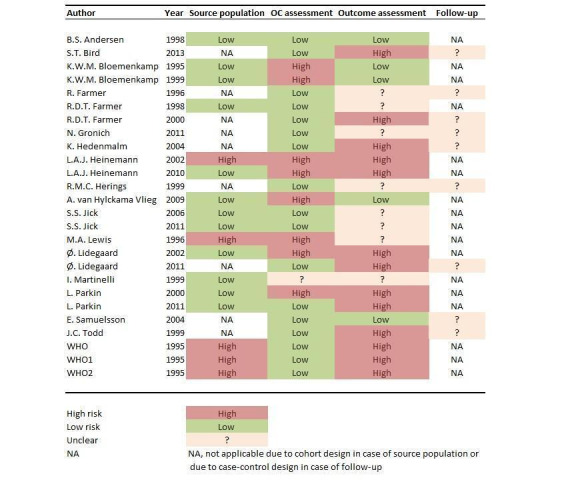

Risk of bias in included studies

Eight studies assessed combined oral contraceptive use through an interview or questionnaire (Figure 2). Only five studies objectively confirmed venous thrombosis in all patients, whereas five case‐control studies selected controls from a population in hospital care. Of the nine cohort studies, none provided information about loss to follow‐up.

2.

Overview of the risk of bias per study

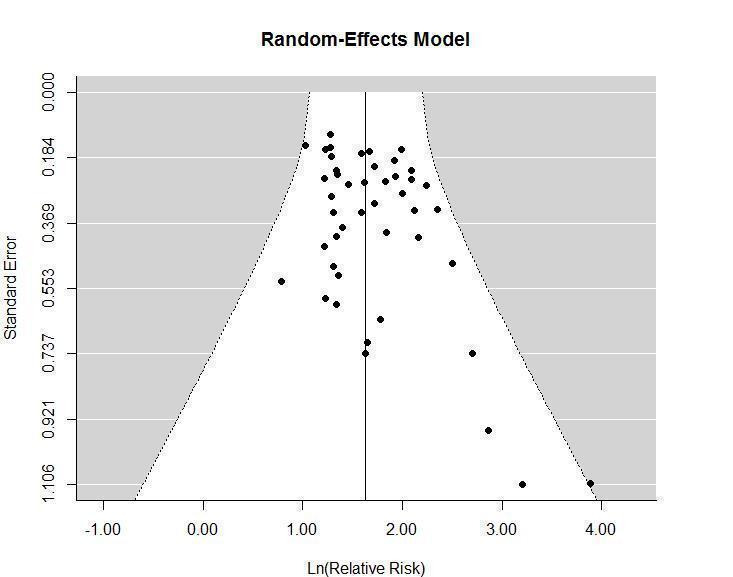

Selective reporting

Neither the funnel plot of the comparison arms of studies (Figure 3) nor the linear regression test as proposed by Egger (p‐value=0.22) suggested asymmetry .

3.

Funnel plot of studies of combined oral contraceptive use and venous thrombosis risk

Effects of interventions

Network meta‐analysis comparing generations of progestogens A total of 23 studies were included for the analysis stratified per generation of progestogen. Three studies (Bird 2013, Jick 2011, Parkin 2011) reported solely on the risk of venous thrombosis in drospirenone, which is not classified as a generation of progestogen. Table 4 provides details of the number of events and total number of women or total follow‐up time per generation, and Table 5 provides the study specific adjusted risk estimates.

4. Included publications with data on generation of progestogens and reference group non‐use.

| Design | Study | Study design | Non‐use | 1st | 2nd | 3rd |

| n event / n total | n event / n total | n event / n total | n event / n total | |||

| 1 | Bloemenkamp 1995 | case control | 46 / 150 | 8 / 13 | 20 / 38 | 37 / 52 |

| Bloemenkamp 1999 | case control | 83 / 511 | 18 / 46 | 8 / 22 | 33 / 67 | |

| Heinemann 2002 | case control | 246 / 2,115 | 45 / 190 | 131 / 865 | 28 /195 | |

| Lidegaard 2011 | cohort | 1,812 / 4,960,730 | 21 / 34,203 | 198 / 233,912 | 1,747 / 2,049,368 | |

| van Hylckama Vlieg 2009 | case control | 421 / 1,523 | 55 / 81 | 382 / 672 | 412 / 582 | |

| WHO 1995a WHO 1 | case control | 168 / 855 | 29 / 74 | 156 / 392 | 53 / 104 | |

| WHO 1995a WHO 2 | case control | 505 / 2,220 | 26 / 65 | 153 / 337 | 18 / 25 | |

| 2 | Heinemann 2010 | case control | 70 / 1,215 | ‐ | 61 / 245 | 62 / 238 |

| Lidegaard 2002 | case control | 458 / 3,196 | ‐ | 98 / 296 | 351 / 1,204 | |

| Parkin 2000 | case control | 9 / 95 | ‐ | 3 / 11 | 12 / 27 | |

| WHO 1995b | case control | 397 / 1,916 | ‐ | 137 / 340 | 71 / 127 | |

| 3 | Andersen 1998 | case control | 27 / 133 | ‐ | ‐ | 16 / 23 |

| Martinelli 1999 | case control | 41 / 179 | ‐ | ‐ | 43 / 79 | |

| Samuelsson 2004 | cohort | 32 / 171,206 | ‐ | ‐ | 17 / 14,819 | |

| 4 | Farmer 2000 | cohort | ‐ | 12 / 39,421 | 98 / 307,070 | 161 / 374,129 |

| Hedenmalm 2004 | cohort | ‐ | 36 / 1,898,899 | 74 / 6,343,562 | 83 / 1,739,393 | |

| 5 | Farmer 1996 | cohort | ‐ | ‐ | 14 / 76,600 | 15 / 65,100 |

| Farmer 1998 | case control | ‐ | ‐ | 27 / 116 | 15 / 79 | |

| Gronich 2011 | cohort | ‐ | ‐ | 23 / 33,187 | 384 / 651,455 | |

| Herings 1999 | cohort | ‐ | ‐ | 29 / 121,411 | 49 / 88,295 | |

| Jick 2006 | nested case control | ‐ | ‐ | 70 / 386 | 211 / 950 | |

| Lewis 1996 | case control | ‐ | ‐ | 96 / 419 | 156 / 451 | |

| Todd 1999 | cohort | ‐ | ‐ | 32 / 76,993 | 53 / 92,052 | |

| Total can be total number of women in the group, or the total follow‐up time. Design refers to the type and number of direct comparisons provided in a single study. Studies with the same design provide direct comparisons of exactly the same generations or same individual oral contraceptives | ||||||

5. Study specific adjusted risk estimates: generations of contraceptives.

| Study | Comparison in RR (95% CI) | |||||

| 1st vs non‐use | 2nd vs non‐use | 3nd vs non‐use | 1st vs 2nd | 3nd vs 2nd | 1st vs 3nd | |

| Andersen 1998 | ‐ | ‐ | 48.6 (5.6‐423) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Bloemenkamp 1995 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Bloemenkamp 1999 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Farmer 1996 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Farmer 1998 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Farmer 2000 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Gronich 2011 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Hedenmalm 2004 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Heinemann 2002 | 8.1 (5.3‐12.5) | 4.9 (3.5‐6.9) | 4.3 (2.6‐7.2) | ‐ | 0.9 (0.6‐1.4) | ‐ |

| Heinemann 2010 | ‐ | 6.9 (4.3‐10.9) | 8.1 (5.0‐13.1) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Herings 1999 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3.5 (1.4‐8.8) | ‐ |

| Jick 2006 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Lewis 1996 | 6.2 (3.8‐10.2 | 3.4 (2.4‐4.6) | 5.4 (3.9‐7.3) | ‐ | 1.6 (1.2‐2.2) | ‐ |

| Lidegaard 2002 | 4.1 (2.4‐7.1) | 2.9 (2.2‐3.8) | 4.0 (3.2‐4.9) | 1.5 (0.9‐2.7) | 1.3 (1.0‐1.8) | ‐ |

| Lidegaard 2011 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Martinelli 1999 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Parkin 2000 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Samuelsson 2004 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Todd 1999 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| van Hylckama Vlieg 2009 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| WHO 1995a WHO 1 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| WHO 1995a WHO 2 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| WHO 1995b | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

Table 6 shows results of the network meta‐analysis according to generations of progestogen. Compared with non‐users, the risk of venous thrombosis in users of oral contraceptives with a first generation progestogen increased 3.2‐fold (95% confidence interval 2.0 to 5.1), 2.8‐fold (2.0 to 4.1) for second generation progestogens, and 3.8‐fold (2.7 to 5.4) for third generation progestogens. The risk of venous thrombosis in second generation progestogen users was similar to the risk in first generation users (relative risk 0.9, 0.6 to 1.4). Third generation users had a slightly higher risk than second generation users (1.3, 1.0 to 1.8). Restricted to studies with an identical classification of generations (see methods section for classification used), the results of each generation compared with non‐use remained the same (first generation relative risk 3.2, 95% confidence interval 1.6 to 6.4; second generation 2.6, 1.5 to 4.7; third generation 3.5, 2.0 to 6.1). A formal interaction test did not show inconsistencies in the network (χ2=2.97, P=0.71).

6. Network meta‐analysis, by generation of progestogen used in combined oral contraceptives.

| Reference group | ||||

| Non‐use | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |

| Non‐use | 1 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 1st | 3.2 (2.0‐5.1) | 1 | ‐ | ‐ |

| 2nd | 2.8 (2.0‐4.1) | 0.9 (0.6‐1.4) | 1 | ‐ |

| 3rd | 3.8 (2.7‐5.4) | 1.2 (0.8‐1.9) | 1.3 (1.0‐1.8) | 1 |

| Data are in relative risk (95% CI) of venous thrombosis | ||||

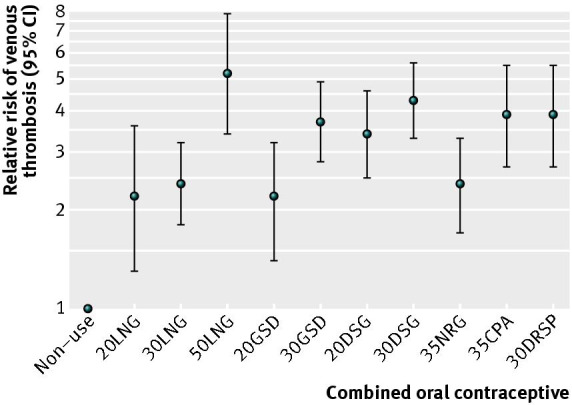

Network meta‐analysis comparing different combined oral contraceptives Of 14 studies providing data per type of oral contraceptive (Table 7, Table 8, Table 9, Table 10), at least one preparation was compared with non‐use or two types were compared directly. Table 11 shows results of the analysis. All preparations were associated with a more than twofold increased risk of venous thrombosis compared with non‐use (Figure 4). The relative risk estimate was highest in 50LNG users and lowest in 20LNG and 20GSD users. A dose related effect was observed for gestodene, desogestrel, and levonorgestrel, with higher doses being associated with higher thrombosis risk. The risk of venous thrombosis for 35CPA and 30DRSP was similar to the risk for 30DSG (relative risk 0.9, 95% confidence interval 0.6 to 1.3 and 0.9, 0.7 to 1.3, respectively, compared with 30DSG). A formal interaction test could not be performed because only two of 14 studies provided data for exactly the same contraceptives.

7. Included publications with data on the 3 / 10 selected contraceptives and reference group non‐use (see also Table 8).

| Design | Study | Study design | Non‐use | 20 LNG | 30 LNG | 50 LNG |

| n event / n total | ||||||

| 1 | van Hylckama Vlieg 2009 | Case‐control | 421 / 1,523 | 8 / 14 | 485 / 858 | 60 / 80 |

| 2 | Lidegaard 2011 | Cohort | 1,812 / 4,960,730 | ‐ | 78 / 104,251 | 31 / 23,691 |

| 3 | Parkin 2000 | Case‐control | 9 / 95 | ‐ | 2 / 6 | 0 / 2 |

| 4 | Lidegaard 2002 | Case‐control | 458 / 2,738 | ‐ | ‐ | 12 / 28 |

| 5 | Bloemenkamp 1999 | Case‐control | 83 / 511 | ‐ | 18 / 46 | ‐ |

| 6 | Bloemenkamp 1995 | Case‐control | 46 / 150 | ‐ | 20 / 38 | ‐ |

| 7 | Farmer 2000 | Cohort | ‐ | ‐ | 64 / 190,191 | ‐ |

| 8 | Todd 1999 | Cohort | ‐ | ‐ | 22 / 49,484 | ‐ |

| 9 | Farmer 1996 | Cohort | ‐ | ‐ | 5 / 35,800 | ‐ |

| 10 | Jick 2006 | Nested cae‐control | ‐ | ‐ | 70 / 386 | ‐ |

| 11 | Bird 2013 | Cohort | ‐ | 30 / 28,782 | 56 / 58,356 | ‐ |

| Jick 2011 | Nested case‐control | ‐ | 20 / 151 | 45 / 282 | ‐ | |

| 12 | Parkin 2011 | Nested case‐control | ‐ | ‐ | 44 / 233 | ‐ |

| 13 | Lewis 1996 | Case‐control | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| Design refers to the type and number of direct comparisons provided in a single study. | ||||||

| Studies with the same design provide direct comparisons of exactly the same generations or same individual oral contraceptives. | ||||||

8. Included publications with data on the 7 / 10 selected contraceptives and reference group non‐use (continuation of Table 7).

| Design | Study | Study design | Non‐use | 20 GSD | 30 GSD | 20 DSG | 30 DSG | 35 NRG | 35 CPA | 30 DRSP |

| n event / n total | ||||||||||

| 1 | van Hylckama Vlieg 2009 | Case‐control | 421 / 1,523 | 14 / 32 | 119 / 186 | 58 / 85 | 289 / 397 | 9 / 13 | 125 / 187 | 19 / 33 |

| 2 | Lidegaard 2011 | Cohort | 1,812 / 4,960,730 | 321 / 472,118 | 738 / 668,355 | 322 / 470,982 | 201 / 170,249 | 165 / 267,664 | 109 / 120,934 | 266 / 286,859 |

| 3 | Parkin 2000 | Case‐control | 9 / 95 | ‐ | 5 / 10 | 4 / 9 | 3 / 8 | ‐ | 2 / 3 | ‐ |

| 4 | Lidegaard 2002 | Case‐control | 458 / 2,738 | 6 / 36 | 206 / 692 | 58 / 187 | 63 / 153 | 18 / 118 | ‐ | ‐ |

| 5 | Bloemenkamp 1999 | Case‐control | 83 / 511 | ‐ | 5 / 9 | 6 / 7 | 22 / 51 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 6 | Bloemenkamp 1995 | Case‐control | 46 / 150 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 37 / 52 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 7 | Farmer 2000 | Cohort | ‐ | ‐ | 63 / 143,581 | 18 / 37,584 | 65 / 152,524 | 15 / 40,440 | 16 / 25,709 | ‐ |

| 8 | Todd 1999 | Cohort | ‐ | ‐ | 21 / 41,947 | 9 / 10,426 | 23 / 39,679 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 9 | Farmer 1996 | Cohort | ‐ | ‐ | 5 / 30,500 | ‐ | 10 / 34,600 | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 10 | Jick 2006 | Nested case‐control | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 87 / 315 | 124/635 | ‐ | ‐ |

| 11 | Bird 2013 | Cohort | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 151/96217 |

| Jick 2011 | Nested case‐control | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 121/434 | |

| 12 | Parkin 2011 | Nested case‐control | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 17/43 |

| 13 | Lewis 1996 | Case‐control | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 15 / 51 | 64 / 174 | 19 / 50 | ‐ | ‐ |

| Design refers to the type and number of direct comparisons provided in a single study. | ||||||||||

| Studies with the same design provide direct comparisons of exactly the same generations or same individual oral contraceptives. | ||||||||||

9. Study specific adjusted risk estimates: per combined oral contraceptive in RR (95% CI) part I.

| Comparisons | Study | |||||

| van Hylckama Vlieg 2009 | Lidegaard 2011 | Parkin 2000 | Lidegaard 2002 | Bloemenkamp 1999 | Bloemenkamp 1995 | |

| 20LNG vs non‐use | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30LNG vs non‐use | 3.6 (2.9‐4.6) | 2.2 (1.7‐2.8) | ‐ | ‐ | 3.7 (1.9‐7.2) | 3.8 (1.7‐8.4) |

| 50LNG vs non‐use | ‐ | 3.5 (2.5‐5.1) | ‐ | 5.3 (2.3‐12.3) | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20GSD vs non‐use | ‐ | 3.5 (3.1‐4.0) | ‐ | 2.0 (0.7‐5.7) | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30GSD vs non‐use | 5.6 (3.7‐8.4) | 4.2 (3.9‐4.6) | ‐ | 3.5 (2.8‐4.5) | 5.2 (1.3‐20.6) | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs non‐use | ‐ | 3.3 (2.9‐3.7) | ‐ | 4.8 (3.2‐7.1) | 24.7 (2.8‐213.5) | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs non‐use | 7.3 (5.3‐10.0) | 4.2 (3.6‐4.9) | ‐ | 5.4 (3.6‐8.0) | 4.9 (2.5‐9.4) | 8.7 (3.9‐19.3) |

| 35NRG vs non‐use | 5.9 (1.7‐21.0) | 2.6 (2.2‐3.0) | ‐ | 1.7 (1.0‐3.1) | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs non‐use | 6.8 (4.7‐10.0) | 4.1 (3.4‐5.0) | 17.6 (2.7‐113.0) | 3.3 (1.4‐7.6) | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs non‐use | 6.3 (2.9‐13.7) | 4.5 (3.9‐5.1) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30LNG vs 20LNG | 0.9 (0.3‐2.5) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 50LNG vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20GSD vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30GSD vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 50LNG vs 30LNG | 2.2 (1.3‐3.7) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20GSD vs 30LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30GSD vs 30LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs 30LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 30LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 30LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 30LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 30LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20GSD vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30GSD vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30GSD vs 20GSD | 3.3 (1.4‐7.1) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs 20GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 20GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 20GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 20GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 20GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs 30GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 30GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 30GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 30GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 30GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 20DSG | 1.4 (0.8‐2.5) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 20DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 20DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 20DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 30DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 30DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 30DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 35NRG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 35NRG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 35CPA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

10. Study specific adjusted risk estimates: per combined oral contraceptive in RR (95% CI) part II.

| Comparisons | Study | |||||||

| Farmer 2000* | Todd 1999 | Farmer 1996 | Jick 2006 | Bird 2013 | Jick 2011 | Parkin 2011 | Lewis 1996 | |

| 20LNG vs non‐use | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30LNG vs non‐use | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 50LNG vs non‐use | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20GSD vs non‐use | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30GSD vs non‐use | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs non‐use | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs non‐use | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs non‐use | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs non‐use | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs non‐use | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30LNG vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 50LNG vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20GSD vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30GSD vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 20LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3.2 (1.8‐5.5) | ‐ | ‐ |

| 50LNG vs 30LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20GSD vs 30LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30GSD vs 30LNG | 1.3 (0.9‐1.9) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs 30LNG | 1.4 (0.8‐2.4) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 30LNG | 1.3 (0.9‐1.8) | ‐ | 1.5 (0.3‐8.3) | 1.7 (1.2‐2.4) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 30LNG | 1.1 (0.6‐2.0) | ‐ | ‐ | 1.1 (0.8‐1.5) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 30LNG | 1.8 (0.9‐3.2) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 30LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 1.8 (1.3‐2.5) | 2.2 (1.5‐3.4) | 3.3 (1.4‐7.6) | ‐ |

| 20GSD vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30GSD vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 50LNG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30GSD vs 20GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs 20GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 20GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 20GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 20GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 20GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20DSG vs 30GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 30GSD | ‐ | ‐ | 1.2 (0.3‐4.0) | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 30GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 30GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 30GSD | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DSG vs 20DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 20DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 20DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 20DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35NRG vs 30DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 30DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 30DSG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 35CPA vs 35NRG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 35NRG | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 30DRSP vs 35CPA | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

11. Results of the network meta‐analysis per combined oral contraceptive pill.

| Non‐use | |||||||||||

| (reference | 20 LNG | 30 LNG | 50 LNG | 20 GSD | 30 GSD | 20 DSG | 30 DSG | 35 NRG | 35 CPA | 30 DRSP | |

| group) | |||||||||||

| Non‐use | 1 | ||||||||||

| 20 LNG | 2.2 (1.3‐3.6) | 1 | 0.9 (0.6‐1.4) | 0.4 (0.2‐0.8) | 1.0 (0.6 (1.8) | 0.6 (0.4‐1.0) | 0.7 (0.4‐1.1) | 0.5 (0.3‐0.8) | 0.9 (0.5‐1.5) | 0.6 (0.3‐1.0) | 0.6 (0.4‐0.9) |

| 30 LNG | 2.4 (1.8‐3.2) | 1.1 (0.7‐1.7) | 1 | 0.5 (0.3‐0.7) | 1.1 (0.8‐1.7) | 0.7 (0.5‐0.9) | 0.7 (0.5‐1.0) | 0.6 (0.4‐0.7) | 1.0 (0.7‐1.4) | 0.6 (0.4‐0.9) | 0.6 (0.5‐0.8) |

| 50 LNG | 5.2 (3.4‐7.9) | 2.3 (1.3‐4.2) | 2.1 (1.4‐3.2) | 1 | 2.4 (1.5‐4.0) | 1.4 (0.9‐2.1) | 1.5 (1.0‐2.4) | 1.2 (0.8‐1.8) | 2.2 (1.4‐3.3) | 1.3 (0.8‐2.1) | 1.3 (0.8‐2.1) |

| 20 GSD | 2.2 (1.4‐3.2) | 1.0 (0.5‐1.7) | 0.9 (0.6‐1.3) | 0.4 (0.3‐0.7) | 1 | 0.6 (0.4‐0.9) | 0.6 (0.4‐1.0) | 0.5 (0.3‐0.7) | 0.9 (0.6‐1.4) | 0.6 (0.4‐0.8) | 0.6 (0.4‐0.9) |

| 30 GSD | 3.7 (2.8‐4.9) | 1.7 (1.0‐2.7) | 1.5 (1.2‐2.0) | 0.7 (0.5‐1.1) | 1.7 (1.1‐2.6) | 1 | 1.1 (0.8‐1.5) | 0.9 (0.7‐1.1) | 1.5 (1.1‐2.1) | 1.0 (0.7‐1.4) | 1.0 (0.7‐1.3) |

| 20 DSG | 3.4 (2.5‐4.6) | 1.5 (0.9‐2.6) | 1.4 (1.0‐1.9) | 0.7 (0.4‐1.0) | 1.6 (1.0‐2.4) | 0.9 (0.7‐1.2) | 1 | 0.8 (0.6‐1.1) | 1.4 (1.0‐2.0) | 0.9 (0.6‐1.3) | 0.9 (0.6‐1.3) |

| 30 DSG | 4.3 (3.3‐5.6) | 1.9 (1.2‐3.1) | 1.8 (1.4‐2.2) | 0.8 (0.5‐1.2) | 2.0 (1.3‐2.9) | 1.2 (0.9‐1.5) | 1.3 (0.9‐1.7) | 1 | 1.8 (1.3‐2.4) | 1.1 (0.8‐1.6) | 1.1 (0.8‐1.5) |

| 35 NRG | 2.4 (1.7‐3.3) | 1.1 (0.7‐1.8) | 1.0 (0.7‐1.3) | 0.5 (0.3‐0.7) | 1.1 (0.7‐1.7) | 0.7 (0.5‐0.9) | 0.7 (0.5‐1.0) | 0.6 (0.4‐0.8) | 1 | 0.6 (0.4‐0.9) | 0.6 (0.4‐0.9) |

| 35 CPA | 3.9 (2.7‐5.5) | 1.7 (1.0‐3.0) | 1.6 (1.1‐2.2) | 0.7 (0.5‐1.2) | 1.8 (1.1‐2.8) | 1.0 (0.7‐1.5) | 1.1 (0.8‐1.6) | 0.9 (0.6‐1.3) | 1.6 (1.1‐2.3) | 1 | 1.0 (0.7‐1.5) |

| 30 DRSP | 3.9 (2.7‐5.5) | 1.7 (1.1‐2.7) | 1.6 (1.2‐2.1) | 0.7 (0.5‐1.2) | 1.8 (1.2‐2.8) | 1.1 (0.7‐1.5) | 1.1 (0.8‐1.6) | 0.9 (0.7‐1.3) | 1.6 (1.1‐2.3) | 1.0 (0.7‐1.5) | 1 |

4.

Network meta‐analysis, per contraceptive plotted on a logarithmic scale.

Dots (lines)=overall relative risk (95% confidence interval) of venous thrombosis; non‐use=reference group.

Sensitivity analyses We performed sensitivity analyses according to funding source, study design, and method of diagnosis confirmation (objective vs subjective confirmation of venous thrombosis). Table 12 shows the results from the sensitivity analysis. Sensitivity analysis stratified by funding source showed that the risk estimate for third generation users (compared with non‐users) was lower in industry sponsored studies than in non‐industry sponsored studies (relative risk 1.9 v 5.2). In cohort studies, the risk estimate for third generation users (compared with non‐users) was lower than the risk for third generation users in case‐control studies (2.0 v 4.2). All risk estimates were higher in studies with objectively confirmed venous thrombosis, of which none were industry sponsored.

12. Results of sensitivity analyses.

| Source of bias and No of studies | ||||||

| Generation of progestogen | Industry (n=8) | Non‐industry (n=9) | Cohort study (n=8) | Case‐control (n=15) | Objectively confirmed venous thrombosis (n=5) | Subjectively confirmed venous thrombosis (n=11) |

| Non‐use | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1st | 2.6 (0.9‐7.4) | 3.3 (2.4‐4.6) | 2.0 (0.4‐10.5) | 3.3 (2.3‐4.7) | 4.5 (3.2‐6.5) | 2.6 (1.3‐5.3) |

| 2nd | 2.1 (1.0‐4.8) | 3.1 (2.5‐3.8) | 1.7 (0.4‐8.0) | 2.9 (2.3‐3.7) | 3.3 (2.8‐4.0) | 2.5 (1.4‐4.5) |

| 3rd | 1.9 (0.8‐4.2) | 5.2 (4.2‐6.5) | 2.0 (0.5‐8.6) | 4.2 (3.3‐5.3) | 6.2 (5.2‐7.4) | 3.0 (1.7‐5.4) |

| Data are relative risk (95% confidence interval) of venous thrombosis | ||||||

Discussion

Summary of main results

We performed a network meta‐analysis based on 26 studies. Overall, combined oral contraceptive use increased the risk of venous thrombosis fourfold. The reported incidence of venous thrombosis in non‐users was in line with the literature. We observed that all generations of progestogens were associated with an increased risk of venous thrombosis and that third generation users had a slight increased risk compared with second generation users. All individual types of combined oral contraceptives increased thrombosis risk compared with non‐use more than two‐fold. The highest risk of venous thrombosis was found among 50LNG users, and the risk was similar in 30DRSP, 35CPA, and 30DSG users. Users of 30LNG, 20LNG, and 20GSD had the lowest thrombosis risk.

Quality of the evidence

See under Potential biases in the review process and Figure 2.

Potential biases in the review process

A network meta‐analysis summarises data from direct and indirect comparisons in a weighted average. In the present study, this resulted in a comprehensive overview of the risk of venous thrombosis in frequently prescribed combined oral contraceptives. The internal validity of the network meta‐analysis was assessed through interaction analysis modelling potential inconsistencies in the network (White 2012). Our results of the analysis based on generations of progestogens indicated that potential inconsistencies are likely the result of chance.

A limitation of our network meta‐analysis was that publications had to provide the crude number of users and number of events per type of combined oral contraceptive. A total of 15 studies provided information on combined oral contraceptive use and thrombosis risk without specification of which contraceptive preparations were used. These studies could therefore not be included. Because of the need for crude numbers in the network meta‐analysis, adjusted risk estimates were not used for pooling the data. Confounding could have influenced our results. Age is a potential confounder for the association between contraceptive use and venous thrombosis. Women using second generation contraceptives are generally older than users of third generation contraceptives. If an analysis is not adjusted for age, the relative risk will then underestimate the risk of venous thrombosis in users of third generation contraceptives compared with users of second generation contraceptives. This implies that the risk of third generation users may be higher than reported here. However, age was often dealt with in the design of the studies. Body mass index is only weakly associated with combined oral contraceptive use, and analyses unadjusted for body mass index are probably not confounded.

There is no generally accepted way to classify oral contraceptives according to generations of progestogens. For instance, norgestimate can be categorised as a second or a third generation progestogen. As a consequence, the classification of these generations was not the same in every publication. However, the results did not materially change when restricted to studies with an identical classification of generations as described in the methods nor when contraceptives with desogestrel or gestodene were compared with levonorgestrel (that is, norgestimate was not taken into account when classifying contraceptives into generations) (data not shown).

In the classification of progestogen generations used in this meta‐analysis, the dose of ethinylestradiol was not taken into account. The observed increased risk in third generation contraceptives, compared with second generation contraceptives, cannot be explained by a difference in ethinylestradiol dose because a higher dose of ethinylestradiol (50 μg) can be present in a second generation contraceptive but not in a third generation contraceptive.

In only a few included studies, venous thrombosis was objectively confirmed in all patients. Only about 30% of patients with clinical symptoms of thrombosis are diagnosed with venous thrombosis (Wells 1995). Including patients without objectively confirmed venous thrombosis would lead to overestimating the association when oral contraceptives users were more likely to be diagnosed than non‐users (diagnostic suspicion bias). However, two studies showed that this bias was independent of type of oral contraceptive (Kemmeren 2001, Vandenbroucke 1997). In studies without objective confirmation, women were misclassified irrespective of their contraceptive use, leading to non‐differential misclassification. Therefore, results of such studies may underestimate the true association, which was confirmed by our sensitivity analysis where the risk estimates were higher in studies with objectively confirmed venous thrombosis than in those without an objective confirmation.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Two other meta‐analyses (Kemmeren 2001, Manzoli 2012) have evaluated the risk of venous thrombosis comparing third generation contraceptive users with second generation users. Both studies found an increased risk in third generation users (relative risk 1.5, 95% confidence interval 1.2 to 1.8 and 1.57, 1.24 to 1.98 53, respectively), which are in line with our results. The majority of included studies from both meta‐analyses were included in our analysis.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

All individual types of combined oral contraceptives increased thrombosis risk compared with non‐use more than two‐fold. The highest risk of venous thrombosis was found among 50LNG users, and the risk was similar in 30DRSP, 35CPA, and 30DSG users. Users of 30LNG, 20LNG, and 20GSD had the lowest thrombosis risk.

It should be kept in mind that all combined oral contraceptives increase the risk of venous thrombosis, which is not the case for the levonorgestrel intrauterine device (van Hylckama Vlieg 2010). However, if a woman prefers using combined oral contraceptives, only contraceptives with the lowest risk of venous thrombosis and good compliance (Gallo 2013) should be prescribed, such as levonorgestrel with 30μg ethinylestradiol. Current practice is to increase the dose of ethinylestradiol in case of disruptions in bleeding patterns (Gallo 2013). Our results indicate that prescribing 50LNG in case of spotting during the use of 30LNG might carry a serious risk for venous thrombosis.

Combining different preparations of oral contraceptive into generations of progestogens may not be an appropriate way to present the risk of thrombosis, because the risk depends on the dose of ethinylestradiol as well as on the progestogen provided. We suggest abstaining from any classification of contraceptives, but to compare the risk of venous thrombosis per oral contraceptive preparation.

Implications for research.

Although we observed that the risk of venous thrombosis increased with the dose of ethinylestradiol, this seemed to depend on the progestogen provided. There was no difference in the venous thrombosis risk between 20LNG and 30LNG, whereas a difference in the risk was observed between 20DSG and 30DSG, for example. It is unclear why the dose effect of ethinylestradiol might depend on the progestogen. A possibility is that there is a difference in inhibitory effects of the progestogen on the procoagulant effect of ethinylestradiol. Oral contraceptive use increases the levels of factors II, VII, VIII, protein C, and decreases the levels of antithrombin, tissue factor pathway inhibitor, and protein S. Clinical studies have showed that this effect on coagulation factors was more pronounced in desogestrel users than in levonorgestrel users, and limited to combined oral contraceptives (Kemmeren 2002b, Kemmeren 2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank Jan W Schoones, Walaeus Library, LUMC, Leiden, NL for developing the search strategies. We thank Ale Algra for helping in the study protocol development.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy for the review

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi‐bin/mrwhome/106568753/HOME)

("oral contraceptives" OR "oral contraceptive" OR combined oral contraceptive* OR ((norethisterone OR norethisteron* OR norethindrone OR norethindron* OR "ethynodiol diacetate" OR lynestrenol OR lynestrenol* OR norethynodrel OR norethynodrel* OR dienogest OR dienogest* OR levonorgestrel OR levonorgestrel* OR norgestrel OR norgestrel* OR dl‐norgestrel OR dl‐norgestrel* OR desogestrel OR desogestrel* OR norgestimate OR norgestimat* OR gestodene OR gestoden* OR "medroxyprogesterone acetate" OR "chlormadinone acetate" OR nomegestrol OR nomegestrol* OR nestorone OR nestoron* OR "Cyproterone acetate" OR Drospirenone OR Drospirenon*) AND ("Ethinyl Estradiol" OR ethinylestradiol OR ethinylestradiol* OR Mestranol OR Mestranol* OR "estradiol valerate" OR "estradiol valerate"))) AND ("deep vein thrombosis" OR "deep venous thrombosis" OR "Venous Thrombosis" OR "Vein Thrombosis" OR "Vein Thrombosis" OR Thrombophlebitis OR "pulmonary embolism" OR "venous thromboembolism" OR "venous thromboembolic disorder*" OR "venous thromboembolic disease*" OR "venous thrombotic") AND risk* AND (women OR woman OR woman* OR women* OR girl OR girls OR female)

PubMed (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/)

("Contraceptives, Oral"[MeSH] OR "Contraceptives, Oral"[Pharmacological Action] OR "oral contraceptives" OR "oral contraceptive" OR "Contraceptives, Oral, Combined"[MeSH] OR "combined oral contraceptives" OR "combined oral contraceptive" OR ((norethisterone OR norethisteron* OR norethindrone OR norethindron* OR "ethynodiol diacetate" OR lynestrenol OR lynestrenol* OR norethynodrel OR norethynodrel* OR dienogest OR dienogest* OR levonorgestrel OR levonorgestrel* OR norgestrel OR norgestrel* OR dl‐norgestrel OR dl‐norgestrel* OR desogestrel OR desogestrel* OR norgestimate OR norgestimat* OR gestodene OR gestoden* OR "medroxyprogesterone acetate" OR "chlormadinone acetate" OR nomegestrol OR nomegestrol* OR nestorone OR nestoron* OR "Cyproterone acetate" OR Drospirenone OR Drospirenon* OR oestrogen*[ti] OR estrogen[ti]) AND ("Ethinyl Estradiol"[MeSH] OR "Ethinyl Estradiol" OR ethinylestradiol OR ethinylestradiol* OR Mestranol OR Mestranol* OR "estradiol valerate"[Supplementary Concept] OR "estradiol valerate" OR progestogen*[ti]))) AND ("deep vein thrombosis"[ti] OR "deep venous thrombosis"[ti] OR "Venous Thrombosis"[ti] OR "Vein Thrombosis"[ti] OR "Venous Thrombosis"[MeSH:noexp] OR "Thrombophlebitis"[MeSH] OR "Upper Extremity Deep Vein Thrombosis"[MeSH] OR Thrombophlebitis[ti] OR "pulmonary embolism"[ti] OR "pulmonary embolism"[MeSH] OR "venous thromboembolism"[ti] OR "Venous Thromboembolism"[MeSH] OR "venous thromboembolic disorders"[ti] OR (venous[ti] AND thromboembolic[ti] AND disorder[ti]) OR "venous thromboembolic diseases"[ti] OR "venous thromboembolic disease"[ti] OR "venous thrombotic"[ti] OR ("Thromboembolism"[MeSH: noexp] AND (venous[tiab] OR vein[tiab] OR veins[tiab))) AND (risk OR risks OR risk factor OR risk factors) AND (women OR woman OR woman* OR women* OR girl OR girls OR female) NOT (animals NOT (human AND animals))

EMBASE (http://gateway.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&MODE=ovid&NEWS=N&PAGE=main&D=emez)

(exp oral contraceptive agent/ OR "oral contraceptives".mp OR "oral contraceptive".mp OR "combined oral contraceptives".mp OR "combined oral contraceptive".mp OR (((norethisterone OR norethisteron* OR norethindrone OR norethindron* OR "ethynodiol diacetate" OR lynestrenol OR lynestrenol* OR norethynodrel OR norethynodrel* OR dienogest OR dienogest* OR levonorgestrel OR levonorgestrel* OR norgestrel OR norgestrel* OR dl‐norgestrel OR dl‐norgestrel* OR desogestrel OR desogestrel* OR norgestimate OR norgestimat* OR gestodene OR gestoden* OR "medroxyprogesterone acetate" OR "chlormadinone acetate" OR nomegestrol OR nomegestrol* OR nestorone OR nestoron* OR "Cyproterone acetate" OR Drospirenone OR Drospirenon*).mp OR oestrogen*.ti OR estrogen.ti) AND (("Ethinyl Estradiol" OR ethinylestradiol OR ethinylestradiol* OR Mestranol OR Mestranol* OR "estradiol valerate" OR "estradiol valerate").mp OR progestogen*.ti))) AND (("deep vein thrombosis" OR "deep venous thrombosis" OR "Venous Thrombosis" OR "Vein Thrombosis").ti OR exp deep vein thrombosis/ OR Vein Thrombosis/ OR Thrombophlebitis/ OR Thrombophlebitis.ti OR "pulmonary embolism".ti OR exp lung embolism/ OR "venous thromboembolism".ti OR exp Venous Thromboembolism/ OR "venous thromboembolic disorder*".ti OR "venous thromboembolic disease*".ti OR "venous thrombotic".ti) AND (exp risk/ OR risk*.mp OR exp risk factor/) AND ((women OR woman OR woman* OR women* OR girl OR girls OR female).mp OR exp female/) AND (exp human/ OR human.ti OR patient.ti OR patients.ti)

CINAHL (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?authtype=ip,uid&profile=lumc&defaultdb=cin20)

TITLE/ABSTRACT/KEYWORD

(oral contraceptives OR oral contraceptive OR combined oral contraceptive* OR ((norethisterone OR norethisteron* OR norethindrone OR norethindron* OR ethynodiol diacetate OR lynestrenol OR lynestrenol* OR norethynodrel OR norethynodrel* OR dienogest OR dienogest* OR levonorgestrel OR levonorgestrel* OR norgestrel OR norgestrel* OR dl‐norgestrel OR dl‐norgestrel* OR desogestrel OR desogestrel* OR norgestimate OR norgestimat* OR gestodene OR gestoden* OR medroxyprogesterone acetate OR chlormadinone acetate OR nomegestrol OR nomegestrol* OR nestorone OR nestoron* OR Cyproterone acetate OR Drospirenone OR Drospirenon*) AND (Ethinyl Estradiol OR ethinylestradiol OR ethinylestradiol* OR Mestranol OR Mestranol* OR estradiol valerate OR estradiol valerate))) AND (deep vein thrombosis OR deep venous thrombosis OR Venous Thrombosis OR Vein Thrombosis OR Vein Thrombosis OR Thrombophlebitis OR pulmonary embolism OR venous thromboembolism OR venous thromboembolic disorder* OR venous thromboembolic disease* OR venous thrombotic) AND risk* AND (women OR woman OR woman* OR women* OR girl OR girls OR female)

Web of Science (http://isiknowledge.com/wos)

TS=("oral contraceptives" OR "oral contraceptive" OR combined oral contraceptive* OR ((norethisterone OR norethisteron* OR norethindrone OR norethindron* OR "ethynodiol diacetate" OR lynestrenol OR lynestrenol* OR norethynodrel OR norethynodrel* OR dienogest OR dienogest* OR levonorgestrel OR levonorgestrel* OR norgestrel OR norgestrel* OR dl‐norgestrel OR dl‐norgestrel* OR desogestrel OR desogestrel* OR norgestimate OR norgestimat* OR gestodene OR gestoden* OR "medroxyprogesterone acetate" OR "chlormadinone acetate" OR nomegestrol OR nomegestrol* OR nestorone OR nestoron* OR "Cyproterone acetate" OR Drospirenone OR Drospirenon*) AND ("Ethinyl Estradiol" OR ethinylestradiol OR ethinylestradiol* OR Mestranol OR Mestranol* OR "estradiol valerate" OR "estradiol valerate"))) AND TI=("deep vein thrombosis" OR "deep venous thrombosis" OR "Venous Thrombosis" OR "Vein Thrombosis" OR "Vein Thrombosis" OR Thrombophlebitis OR "pulmonary embolism" OR "venous thromboembolism" OR "venous thromboembolic disorder*" OR "venous thromboembolic disease*" OR "venous thrombotic") AND TS=risk* AND TS=(women OR woman OR woman* OR women* OR girl OR girls OR female)

Academic Search Premier (http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?authtype=ip,uid&profile=lumc&defaultdb=aph)

title/su/kw/ab

(oral contraceptives OR oral contraceptive OR combined oral contraceptive* OR ((norethisterone OR norethisteron* OR norethindrone OR norethindron* OR ethynodiol diacetate OR lynestrenol OR lynestrenol* OR norethynodrel OR norethynodrel* OR dienogest OR dienogest* OR levonorgestrel OR levonorgestrel* OR norgestrel OR norgestrel* OR dl‐norgestrel OR dl‐norgestrel* OR desogestrel OR desogestrel* OR norgestimate OR norgestimat* OR gestodene OR gestoden* OR medroxyprogesterone acetate OR chlormadinone acetate OR nomegestrol OR nomegestrol* OR nestorone OR nestoron* OR Cyproterone acetate OR Drospirenone OR Drospirenon*) AND (Ethinyl Estradiol OR ethinylestradiol OR ethinylestradiol* OR Mestranol OR Mestranol* OR estradiol valerate OR estradiol valerate))) AND (deep vein thrombosis OR deep venous thrombosis OR Venous Thrombosis OR Vein Thrombosis OR Vein Thrombosis OR Thrombophlebitis OR pulmonary embolism OR venous thromboembolism OR venous thromboembolic disorder* OR venous thromboembolic disease* OR venous thrombotic) AND risk* AND (women OR woman OR woman* OR women* OR girl OR girls OR female)

TITLE((oral contraceptives OR oral contraceptive OR combined oral contraceptive* OR ((norethisterone OR norethisteron* OR norethindrone OR norethindron* OR ethynodiol diacetate OR lynestrenol OR lynestrenol* OR norethynodrel OR norethynodrel* OR dienogest OR dienogest* OR levonorgestrel OR levonorgestrel* OR norgestrel OR norgestrel* OR dl‐norgestrel OR dl‐norgestrel* OR desogestrel OR desogestrel* OR norgestimate OR norgestimat* OR gestodene OR gestoden* OR medroxyprogesterone acetate OR chlormadinone acetate OR nomegestrol OR nomegestrol* OR nestorone OR nestoron* OR Cyproterone acetate OR Drospirenone OR Drospirenon*) AND (Ethinyl Estradiol OR ethinylestradiol OR ethinylestradiol* OR Mestranol OR Mestranol* OR estradiol valerate OR estradiol valerate))) AND (deep vein thrombosis OR deep venous thrombosis OR Venous Thrombosis OR Vein Thrombosis OR Vein Thrombosis OR Thrombophlebitis OR pulmonary embolism OR venous thromboembolism OR venous thromboembolic disorder* OR venous thromboembolic disease* OR venous thrombotic) AND risk* AND (women OR woman OR woman* OR women* OR girl OR girls OR female))

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Andersen 1998.

| Methods | Case control study | |

| Participants | 67 cases / 134 controls (hospital discharge) diagnosis: anticoagulation |

|

| Interventions | 3rd generation | |

| Outcomes | Events during 3rd generation: 16 / 23. Non‐use: 27 / 133. Adjustment for confounding: yes (matched) |

|

| Notes | Denmark | |

Bird 2013.

| Methods | cohort study | |

| Participants | 2001‐2009 432,178 women / 263,902 women years (healthcare plan) age: 18‐46 y diagnosis: anticoagulation |

|

| Interventions | 2nd generation and Drospirenone | |

| Outcomes | Events during 2nd generation: 118 / 132,681. Drospirenone: 236 / 131,221. Adjustment for confounding: yes |

|

| Notes | USA | |

Bloemenkamp 1995.

| Methods | case control study | |

| Participants | 1988‐1995 126 cases / 159 controls (community based) age: 15‐49 y diagnosis: anticoagulation |

|

| Interventions | 1st, 2nd and 3rd generation | |

| Outcomes | Events during 1st genaration: 8 / 13; 2nd generation 20 / 38; 3rd generation 37 / 52. Non‐use: 46 / 150 . Adjustment for confounding: yes |

|

| Notes | The Netherlands | |

Bloemenkamp 1999.

| Methods | case control study | |

| Participants | 1982‐1995 185 cases / 591 controls (community based) age: 15‐49 y diagnosis: anticoagulation |

|

| Interventions | 1st, 2nd and 3rd generation | |

| Outcomes | Events during 1st genaration: 18 / 46; 2nd generation 8 / 22; 3rd generation 33 / 67. Non‐use: 83 / 511. Adjustment for confounding: yes |

|

| Notes | The Netherlands | |

Farmer 1996.

| Methods | cohort study | |

| Participants | 30 cases / 697,000 women (general practioners database) age 14‐45 y diagnosis: anticoagulation |

|

| Interventions | 2nd and 3rd generation | |

| Outcomes | Events using during 2nd generation 14 / 76,600; 3rd generation 15 / 65,100. Adjustment for confounding: yes |

|

| Notes | United Kingdom | |

Farmer 1998.

| Methods | case control study | |

| Participants | 1992‐1995 42 cases / 168 controls (healthcare plan) age: 18‐49 y diagnosis: anticoagulation |

|

| Interventions | 2nd and 3rd generation | |

| Outcomes | Events during 2nd generation 27 / 116; 3rd generation 15 / 79. Adjustment for confounding: yes (matched) |

|

| Notes | Germany | |

Farmer 2000.

| Methods | cohort study | |

| Participants | 1992‐1997 287 cases / 783,876 women years (prescription database) age: 15‐49 y diagnosis: ad hoc |

|