Abstract

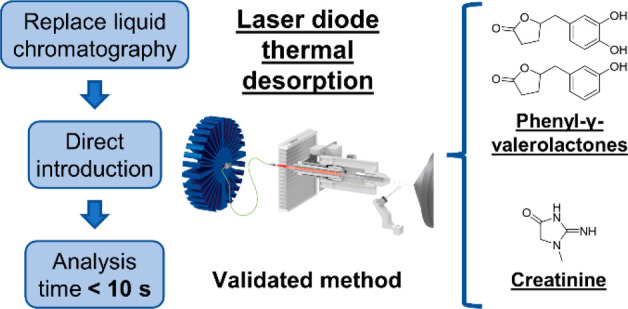

Quantification of nutritional biomarkers is crucial to accurately assess the dietary intake of different classes of (poly)phenols in large epidemiological studies. High-throughput analysis is mandatory to apply this methodology in large cohorts. However, the current validated methods to quantify (poly)phenols metabolites in biological fluids use ultra performance liquid chromatography (UPLC), leading to analysis time of several minutes per sample. To significantly reduce the run time, we developed and validated a method to quantify in urine the flavan-3-ols biomarkers, phenyl-γ-valerolactones (PVLs), using laser diode thermal desorption (LDTD). This mass spectrometry source allows direct introduction of sample extracts, resulting in analysis time of less than 10 s per sample. Also, to encompass the problem associated with the cost and availability of sulfated and glucuronide analytical standards, urine samples were subjected to enzymatic hydrolysis. Creatinine was also quantified to normalize the results obtained from the urinary spot. Results obtained with LDTD-MS/MS were cross-validated by UPLC-MS/MS using 155 urine samples. Coefficient of correlation was above 0.975 for PVLs and creatinine. For all analytes, the accuracy was between 90% and 113% by LDTD-MS/MS. Altogether, sample preparation was fully automated to demonstrate the application potential of this method to large cohorts.

Keywords: method validation, dietary assessment, ultrafast analysis, flavan-3-ols, biomarker

1. Introduction

Consumption of dietary (poly)phenols is associated with the prevention of several chronic diseases such as diabetes, cancer, neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases (CVD).1 Over the past decade, several large-scale epidemiological observational and interventional studies have been conducted to link flavan-3-ol intake, a class of (poly)phenolic compounds principally found in tea, red wine, cocoa, pome fruits and berries,2 to the reduction of CVD, such as COSMOS (NCT02422745).3 In observational studies, dietary intake of flavan-3-ols is often estimated based on self-reported dietary data (i.e., food frequency questionnaires) combined with food composition database like Phenol-Explorer.4 However, estimations based on this method are often heavily biased and can only provide an estimation of particular dietary patterns.5−9 To accurately assess the flavan-3-ol intake, the use of a nutritional biomarker, namely 5-(3′,4′-dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone (3,4-DHPVL) (Figure 1), has been validated8 and used to investigate the association between flavan-3-ol intake and CVD risk markers in the EPIC Norfolk cohort.5 This biomarker has also been used to assess compliance with the cocoa extract treatment in the COSMOS study.3

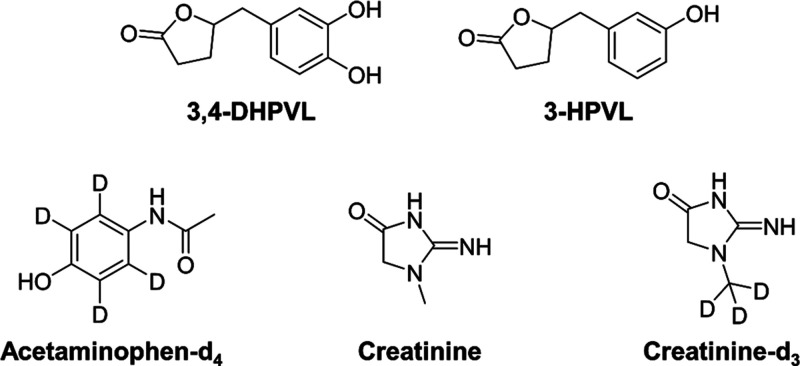

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the analytes and internal standards included in this study.

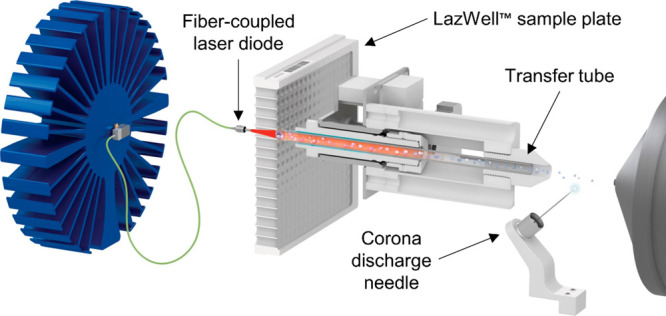

To estimate the flavan-3-ol intake in these studies using this biomarker, the concentration of sulfate and glucuronide 3,4-DHPVL derivatives have been quantified in urine by ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) with a typical analysis time of 8 min.5,8 The methodology was recently adapted to quantify these metabolites in plasma with the same analysis time.10 However, a shorter analysis time is required to efficiently apply those methods in wide-scale epidemiological studies. New UPLC protocols, while much faster than conventional HPLC methodologies, still take a few minutes of runtime and are not readily applicable to large cohorts. New technologies are thus sought for the rapid quantification of biomarkers. Laser diode thermal desorption (LDTD) is a new ultrarapid methodology of direct introduction of sample extracts into the MS which bypasses the time-consuming chromatographic separation step. This approach is now applicable to toxicology studies to quantify different drug metabolites in urine and blood in only few seconds.11,12 Briefly, a small volume of sample extracts (1–10 μL) is placed on a microplate and then quickly dried. Using a fiber-coupled laser diode, the sample is gently evaporated by indirect thermal desorption and transported to MS along with compressed air, where analytes are ionized by atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI) without solvent (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of LDTD source coupled to mass spectrometer.

The aim of this study is to develop and validate a high-throughput LDTD-MS/MS method to quantify 3,4-DHPVL and 5-(3′-hydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone (3-HPVL) (Figure 1), the two most abundant phenyl-γ-valerolactones (PVLs) in urine. 3-HPVL was included because 3,4-DHPVL can be dehydroxylated by the gut microbiota to form 3-HPVL.13 This method advantageously uses a newly developed protocol based on enzymatic hydrolysis of phase II conjugations, allowing quantification with affordable and commercially available unconjugated metabolites.14 To normalize results obtained with spot urine samples, we also developed and validated a high-throughput method to quantify creatinine by LDTD-MS/MS. The results obtained with both methods were cross-validated by UPLC-MS/MS using a total of 155 urine samples (first morning spot and 24 h urine). Finally, to demonstrate the applicability of this method in large scale studies, sample preparation for both analyses was fully automated.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Sodium chloride (NaCl, purity ≥99%), potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KH2PO4, purity ≥99%), bovine serum albumin (purity ≥98%), creatinine (purity ≥98%), acetaminophen-d4 (100 μg/mL in methanol) and LC-MS grade ammonium acetate (purity ≥99%) and ammonium hydroxide (28% in water, ≥99.99% trace metals basis) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, Canada). LC-MS grade acetonitrile (purity ≥99.9%), methanol (purity ≥99.9%) and formic acid (purity ≥99%) were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Ottawa, Canada). Purified solutions of βGL (a genetically modified enzyme from Escherichia coli commercially available as IMCSzyme), aSL (a genetically modified enzyme from Pseudomonas aeruginosa commercially available as Sulfazyme PaS) and 1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 8.0) were kindly provided by Integrated Micro-Chromatography Systems (IMCS), Inc. (Irmo, SC, USA). Creatinine-d3 (methyl-d3, purity ≥99%) was purchased from C/D/N Isotopes (Pointe-Claire, Canada). 5-(3′-Hydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone (purity ≥95%) and 5-(3′,4′-dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone (purity ≥95%) were obtained from Enamine (Monmouth Jct., NJ). Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm, TOC ≤ 3 ppb) was obtained from a Millipore Milli-Q water purification system (Oakville, Ontario). The cranberry extract capsules used in the two clinical trials were kindly provided by Symrise (former Diana Food, Champlain, Canada). Chemical structure of the analytes and internal standards used in this study are presented in Figure 1.

2.2. Study Design of the Clinical Trials

Urine samples from two clinical trials where participants were given flavan-3-ols from a cranberry extract were used for cross-validation of the results obtained by LDTD-MS/MS with the reference method (UPLC-MS/MS). Design of study A and part of study B has already been described elsewhere.14 Briefly, in study A, 12 healthy participants consumed a cranberry extract, providing 86.9 mg of flavan-3-ols per day and supplied a 24 h urine sample at 3 different times (at the beginning and at the end of the supplementation and a week after the treatment period). In total, 36 samples of 24 h urine were collected. In study B, 39 healthy subjects (15 men and 24 women) aged between 23 and 63 years old (36 years old on average) provided first morning spot urine at recruitment (free-living conditions). Once recruited, participants were asked to avoid any food or beverage known to contain flavan-3-ols (see Supporting Information (SI), Table S1) for 7 days and while maintaining the strict dietary restrictions, were given a cranberry extract providing 82.3 mg of flavan-3-ols per day for 4 days. The cranberry extract was characterized as previously published15 and results are presented in SI, Table S2. Every subject collected 24 h urine before and after the supplementation period. Aliquot of 2 mL were stored at −80 °C until analysis. Then 24 h urine samples were diluted with Milli-Q water according to the 24 h urinary excretion volume to standardize the dilution level across all samples, while first morning spot urine samples were simply diluted with an equal volume of Milli-Q water. Informed consent was obtained from all human subjects and both studies were approved by the ethics committee for research involving human beings of Laval University under registration number: 2019–312. Study B is also registered at https://clinicaltrials.gov/ as NCT05931237.

2.3. Quantification of 3-HPVL and 3,4-DHPVL

2.3.1. Preparation of Working Solutions, Calibration Standards and Quality Control Samples

Working solutions were spiked in a pool of urine with low concentrations of 3-HPVL and 3,4-DHPVL (blank matrix) after the enzymatic hydrolysis with a ratio of 1:9 (v/v) to prepare calibration standards (CS) and quality control (QC) samples. Hence, working solutions were prepared 10 times more concentrated than the actual calibration range in acetonitrile. Working solution concentrations are presented in SI, Table S3.

2.3.2. Sample Preparation

The sample preparation was fully automated using an Azeo Liquid Handler (Phytronix Technologies, Quebec, Canada) equipped with a P300 GEN2 pipet and an P20 GEN2 pipet (Opentrons, Brooklyn, NY, USA). The pseudo-code used to prepare the samples for the quantification of PVLs in urine is available in the Supporting Information.

The first preparation step was to hydrolyze phase II conjugations (sulfate and glucuronide) using purified recombinant enzymes (arylsulfatase and β-glucuronidase) to release unconjugated 3-HPVL and 3,4-DHPVL using a previously published protocol.14 The methodology was adapted to perform enzymatic hydrolysis at room temperature for 5 min rather than at 40 °C for 30 min. To confirm that these alterations did not affect the efficiency of hydrolysis, we conducted a hydrolysis kinetic study. A pooled sample of urine was hydrolyzed for 120 min in triplicate. Samples were collected after 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 60 and 120 min and results are presented in ESI Figure S1.

Briefly, 50 μL of urine was added to 25 μL of freshly prepared enzymatic hydrolysis mix composed of 1 M Tris-HCl buffer (pH = 8.0), arylsulfatase and β-glucuronidase (20:40:40, v/v/v) in a 96 deep well plate. Using the Lumo vortexer (Phytronix Technologies, Quebec, Canada), samples were agitated at 1000 rpm during 30 s. Enzymatic hydrolysis was carried out at room temperature for 5 min. To stop the enzymatic process, 295 μL of acetonitrile spiked with 0.25 ppm of acetaminophen-d4 (internal standard) was added and the samples were vortexed at 1000 rpm during 30 s. Then, 5 μL of working solution (or acetonitrile) was added and the samples were agitated again at 1000 ppm for 30 s. In order to perform salt-assisted liquid–liquid extraction, 75 μL of water saturated with NaCl was added to induce phase separation. Samples were agitated at 1000 rpm during 30 s and a pause of 30 s was performed to allow complete phase separation before the next step.

For LDTD-MS/MS analysis, 20 μL of the organic upper layer was added to 20 μL of coating solution composed of water and acetonitrile (75:25, v/v) containing 10 mM of KH2PO4 and 200 ppm of bovine serum albumin in a 96 deep well plate and the resulting diluted solution was mixed with the pipet by aspirating and dispensing the solution multiple times. Then 4 μL of this diluted solution were spotted on a LazWell 96-plate and were then dried during 6 min at 40 °C using Aura V2 dryer (Phytronix Technologies, Quebec, Canada) before analysis.

For UPLC-MS/MS analysis, 100 μL of the organic upper layer was transferred to a new 96 deep well plate and evaporated to dryness under a nitrogen flow. Samples were reconstituted by adding 100 μL of a mix of water and acetonitrile (90:10, v/v) acidified with 0.1% formic acid. Finally, reconstituted samples were filtered using a 0.22 μm water wettable polytetrafluoroethylene (wwPTFE) filter plate at 1500g and 4 °C for 5 min before analysis.

2.3.3. High-Throughput Analysis Using LDTD-MS/MS

LDTD-MS/MS analysis was performed using a Sciex API-5500 Qtrap mass spectrometer (Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA) coupled with Phytronix Luxon ion source model S-960 (Phytronix Technologies, Quebec, Canada).

Samples were desorbed from the individual wells on the plate using a laser power ramp of 3 s to 55% with a flow of 3 L/min of compressed air to carry the sample into to source of the mass spectrometer. Total analysis time was 6 s per sample. The MS acquisition was carried out in negative ion mode. The curtain gas flow and collision gas flow were set, respectively, at 10 and 8 (arbitrary units) and the IonSpray voltage was set at −5.5 kV, while temperature and ion source gas 1 and 2 were all set to 0. A declustering potential of −80 (arbitrary units), an entrance potential of −10 (arbitrary units), a collision cell exit potential of −15 (arbitrary units) and a dwell time of 30 ms were used for each transition. For acetaminophen-d4 (internal standard), the same transition of 154 → 111 with a collision energy (CE) of −25 V was used for quantitation and confirmation. For 3-HPVL, the quantitative transition was 191 → 106 (CE = −35 V) and the confirmation one was 191 → 147 (CE = −25 V), while for 3,4-DHPVL, 207 → 163 (CE = −25 V) and 207 → 122 (CE = −40 V) were used for the quantitative transition and the confirmation transition, respectively. Data were processed using MultiQuant software v 2.1 (Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA).

2.3.4. Reference Analysis Using UPLC-MS/MS

UPLC-MS/MS analysis was performed using an Acquity H-Class UPLC coupled to a TQD mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). Chromatographic separation was achieved with an Acquity UPLC HSS T3 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.8 μm) (Waters, Milford, MA) with an Acquity UPLC HSS T3 VanGuard precolumn (2.1 mm × 5 mm, 1.8 μm) (Waters, Milford, MA) heated to 40 °C using a binary gradient elution composed of water (mobile phase A) and acetonitrile (mobile phase B), both acidified with 0.01% formic acid. The elution was done at a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min with the following gradient: 0–0.4 min, 2% B; 0.5–6.75 min, 2–45% B; 6.75–6.85 min, 45–95% B; 6.85–11.3 min, 95% B; 11.3–11.4 min, 95–2% B and 11.4–15 min: 2% B. The injection volume was 10 μL and samples were kept at 8 °C in the autosampler compartment.

The MS acquisition was done in negative electrospray ionization mode. The voltages of the capillary, cone, extractor and RF lens were set, respectively, to −0.8 kV, −40 V, −3 V and −0.3 V. The temperature of the source and the desolvation gas were set, respectively, to 150 and 400 °C while the desolvation and cone gas flow were set, respectively, to 800 and 50 L/h. The same transitions used for LDTD-MS/MS analysis were used with CE optimized for UPLC-MS/MS analysis with a dwell time of 20 ms (see SI, Table S4). Data processing was performed using Skyline 21.1.16

2.4. Quantification of Creatinine

2.4.1. Preparation of Working Solutions, CS and QC Samples

Working solution was spiked in water with a ratio of 1:9 (v/v) to prepare CS and QC samples. Water was chosen as matrix for CS and QC, because the urine samples were very diluted (858.5×), hence eliminating the matrix effect from urine. However, to validate the absence of a matrix effect, working solutions were spiked in different urine samples with a ratio of 1:9 (v/v). Hence, as for PVLs analysis, working solutions were prepared 10 times more concentrated than the actual calibration range in water. Working solutions concentration are presented in SI, Table S3.

2.4.2. Sample Preparation

The sample preparation was fully automated by using the same system used for PVLs analysis (described in section 2.3.2). The pseudo-code used to prepare the samples for the quantification of creatinine in urine is available in the Supporting Information.

At the onset, we added 40 μL of urine to 300 μL of a mix of methanol and water (90:10, v/v) spiked with 40 ppm of creatinine-d3 in a 96 deep well plate. The resulting solution was mixed with the pipet by aspirating and dispensing the solution multiple times. Then, in a new 96 deep well plate, 3 μL of this initial dilution was added to 300 μL of a mix of methanol and water (90:10, v/v) to obtain the desired dilution factor (858.5×). Using the Lumo vortexer, samples were agitated at 1000 rpm for 30 s.

For LDTD-MS/MS analysis, 4 μL of the final dilution was spotted on a LazWell 96 plate and dried during 4 min at 40 °C using Aura V2 dryer before analysis, while for UPLC-MS/MS analysis, the diluted samples (858.5×) were simply filtered using a 0.22 μm wwPTFE filter plate at 1500g and 4 °C for 5 min before analysis.

2.4.3. High-Throughput Analysis Using LDTD-MS/MS

LDTD-MS/MS was performed using the same system described in section 2.3.3. Samples were desorbed from the plate using a laser power ramp of 3 s to 65% and held at this power for 2 s with a flow of 6 L/min of carrier gas. Total analysis time was 7 s per sample. The MS acquisition was carried out in positive ion mode. The curtain gas flow and collision gas flow were set, respectively, at 20 and 7 (arbitrary units) and the IonSpray voltage was set at 6 kV, while temperature and ion source gas 1 and 2 were all set to 0. A declustering potential of 180 (arbitrary units), an entrance potential of 10 (arbitrary units), a collision cell exit potential of 15 (arbitrary units) and a dwell time of 40 ms were used for each transition. For creatinine, the quantitative transition was 114 → 86 (CE = 15 V) and the confirmation one was 114 → 72 (CE = 21 V), while for creatinine-d3 (internal standard) the same transitions with the same CE were used, except with a 3 Da shift of masses (117 → 89 and 117 → 75). Data were processed using MultiQuant software 2.1 (Sciex, Framingham, MA, USA).

2.4.4. Reference Analysis Using UPLC-MS/MS

UPLC-MS/MS was performed using the same system and the same column described in section 2.3.4. The methodology was adapted from a previously published method.17 Briefly, the mobile phases were composed of 20 mM ammonium acetate adjusted to pH = 7.0 with ammonium hydroxide (A) and methanol (B). Elution was done at 40 °C with a flow rate of 0.4 mL/min and the following gradient: 0–1.75 min, 0% B; 1.75–2 min, 0–95% B; 2–2.5 min, 95% B; 2.5–2.6 min, 95–0% B; and 2.6–4 min, 0% B. The injection volume was 2 μL and samples were kept at 8 °C in the autosampler compartment.

The MS acquisition was performed in positive electrospray ionization mode. The voltages of the capillary, cone, extractor and RF lens were set, respectively, to 0.8 kV, 40 V, 3 V and 1 V. The temperatures (source and desolvation) and gas flow rates (desolvation and cone) were the same as those used for PVLs analysis (described in section 2.3.4). The same transitions used for LDTD-MS/MS analysis were used with CE optimized for UPLC-MS/MS analysis with a dwell time of 40 ms (see SI, Table S4). Data processing was performed using Skyline 21.1.16

2.5. Method Validation

The two LDTD-MS/MS methods (PVLs and creatinine) were validated for linearity, sensitivity with the limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantification (LOQ), precision and accuracy within and between runs, recovery and selectivity according to the Eurachem guideline.18 In addition, wet and dry stabilities, which are specific to LDTD-MS/MS analysis, were evaluated to replace the classic autosampler stability determined for UPLC-MS/MS analysis.

Linearity was assessed with the coefficient of determination (R2) of seven different calibration curves for each analyte. LOD and LOQ were determined by calculating an adjusted standard deviation (s′0) from 10 replicates of blank matrix for PVLs and from 10 replicates of the lowest CS (CS #1 = 100 μg/L) for creatinine because calibration curve and QC were prepared in water for creatinine analysis, as follows:

| 1 |

To obtain the LOD, the adjusted standard deviation was multiplied by three, while it was multiplied by ten to determine the LOQ.

Precision and accuracy were evaluated within and between runs. Within each run, six replicates of each QC level (low, QC-L; medium, QC-M; high, QC-H) were analyzed. To assess the precision and accuracy between runs, six runs were performed, resulting in a total of 36 replicates. The lowest and highest CS (CS #1 and CS #8) were also used to assess these two parameters within run. Precision was expressed as the coefficient of variation (CV), while accuracy was calculated as follows:

| 2 |

Recovery was checked for the PVLs method to determine if these analytes were fully recovered after salt-assisted liquid–liquid extraction. This parameter was not evaluated for the creatinine method because the urine samples were only diluted and not extracted. To assess the recovery, the blank matrix was spiked before and after extraction and was calculated as follows:

| 3 |

This parameter was measured with six replicates of two levels of QC (QC-L and QC-H).

Specificity was assessed using two different tests. First, the matrix effect was evaluated by analyzing six urine samples from different donors with and without being spiked at the concentration of QC-M. Each urine matrix was measured with six replicates to calculate the precision and the accuracy. Second, to assess if the absence of chromatographic separation caused interference using LDTD-MS/MS, a total of 155 urine samples (first morning spot and 24 h urine) were analyzed by LDTD-MS/MS and UPLC-MS/MS. Passing–Bablock regression, a robust approach for method comparison,19 was used to validate that results obtained from LDTD-MS/MS were equivalent to the reference method (UPLC-MS/MS).

Finally, the stability of the different analytes was assessed by preparing a run composed of two calibration curves and six replicates of each QC level (QC-L, QC-M and QC-H) and was analyzed immediately. After, the samples were spotted on a different sample plate, dried and kept at room temperature for 1 h, before being analyzed to evaluate the dry stability. The urine extract (for PVLs analysis) and urine final dilution (for creatinine analysis) were kept at 4 °C for 1 week prior to the analysis to determine the wet stability.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with R 4.1.0, using RStudio 2022.12.0. The package mcr (1.2.2) was used for Passing–Bablock regression and figures were generated with ggplot2 (3.3.5) and ggpubr (0.4.0).

3. Results

3.1. Determination of the Linearity, Limits of Detection and Quantification

The calibration curves of each analyte, all having the same dynamic range of 40, showed good linearity with a R2 superior to 0.997 (Table 1). 3-HPVL showed the best sensitivity with the lowest LOQ and LOD, while 3,4-DHPVL and creatinine shared the similar values. Overall, all LOD were under 12.1 μg/L and LOQ were lower than 40.5 μg/L (Table 1).

Table 1. Limit of Detection (LOD), Limit of Quantification (LOQ) and Linearity of PVLs and Creatinine in Urine by LDTD-MS/MS.

| linearity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| analyte | range (μg/L) | R2 | LOD (μg/L) | LOQ (μg/L) |

| 3-HPVL (191 → 106) | 50–3000 | 0.999 | 2.4 | 8.1 |

| 3,4-DHPVL (207 → 163) | 100–6000 | 0.997 | 12.0 | 40.0 |

| creatinine (114 → 86) | 100–4000 | 0.998 | 12.1 | 40.5 |

3.2. Evaluation of the within and between Runs Precision and Accuracy

Precision and accuracy results are presented in Table 2. Within run precision was slightly superior at the lowest and highest concentrations (CS #1 and CS #8) with CV up to 11.6%, while the CV at intermediate concentrations (QC-L, QC-M, QC-H) were under 4.9%. The CV reflecting between runs precision was higher, especially for 3,4-DHPVL, with values up to 10.6%. Within and between runs, accuracy results were included between 90 and 113% for all analytes.

Table 2. Accuracy and Precision within and between Runs of PVLs and Creatinine in Urine by LDTD-MS/MS.

| within

run (N = 6) |

between

run (N = 36) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| analyte | QC | nominal concentration (μg/L) | mean concentration (μg/L) | precision (% CV) | accuracy (%) | mean concentration (μg/L) | precision (% CV) | accuracy (%) |

| 3-HPVL (191 → 106) | CS #1 | 50 | 56.1 | 7.5 | 112.1 | |||

| QC-L | 150 | 148.3 | 1.6 | 98.9 | 153.2 | 6.3 | 102.1 | |

| QC-M | 1250 | 1232.8 | 4.9 | 98.6 | 1273.8 | 5.1 | 101.9 | |

| QC-H | 2250 | 2358.4 | 4.7 | 104.8 | 2330.8 | 5.0 | 103.6 | |

| CS #8 | 3000 | 2857.0 | 7.4 | 95.2 | ||||

| 3,4-DHPVL (207 → 163) | CS #1 | 255 | 287.7 | 5.8 | 112.8 | |||

| QC-L | 455 | 432.8 | 4.5 | 95.1 | 463.1 | 9.0 | 101.8 | |

| QC-M | 2655 | 2529.6 | 3.8 | 95.3 | 2561.4 | 10.6 | 96.5 | |

| QC-H | 4655 | 4720.1 | 4.4 | 101.4 | 4686.6 | 8.3 | 100.7 | |

| CS #8 | 6155 | 5559.6 | 6.8 | 90.3 | ||||

| creatinine (114 → 86) | CS #1 | 100 | 101.9 | 11.6 | 101.9 | |||

| QC-L | 300 | 299.1 | 3.1 | 99.7 | 293.7 | 5.6 | 97.9 | |

| QC-M | 1200 | 1154.7 | 3.8 | 96.2 | 1156.0 | 5.0 | 96.3 | |

| QC-H | 3000 | 2960.0 | 2.8 | 98.7 | 2967.0 | 4.0 | 98.9 | |

| CS #8 | 4000 | 4054.4 | 6.7 | 101.4 | ||||

3.3. Recovery of the PVLs after Salt-Assisted Liquid–Liquid Extraction

3-HPVL and 3,4-DHPVL were recovered similarly after the extraction. The recovery was better at high concentration (QC-H) with values superior to 92%, while at low concentration (QC-L), the results were higher than 86% (Table 3).

Table 3. Recovery of PVLs in Urine Extract by LDTD-MS/MS.

| analyte | QC | nominal concentration (μg/L) | recovery (%)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-HPVL (191 → 106) | QC-L | 150 | 88.4 ± 1.4 |

| QC-H | 2250 | 94.3 ± 1.9 | |

| 3,4-DHPVL (207 → 163) | QC-L | 455 | 86 ± 8 |

| QC-H | 4655 | 92 ± 4 | |

Recovery values are expressed as mean of 10 replicates ± standard deviation.

3.4. Assessment of the Matrix Effect

To determine the matrix effect, accuracy and precision were measured in six urine samples from different donors and the results are shown in Table 4. Overall, the results obtained from the six different urine matrices are similar to the within run precision and accuracy for the three analytes, with CV ranging from 2.4 to 14.3% and accuracy values varying from 90.4 to 113.8%.

Table 4. Matrix Effect Evaluation of PVLs and Creatinine in Urine by LDTD-MS/MS.

| analyte | matrix | nominal concentration (μg/L) | mean concentration (μg/L) | precision (% CV) | accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-HPVL (191 → 106) | #1 | 1250 | 1130.5 | 2.4 | 90.4 |

| #2 | 1250 | 1164.8 | 5.5 | 93.2 | |

| #3 | 1250 | 1232.4 | 9.6 | 98.6 | |

| #4 | 1250 | 1203.2 | 5.6 | 96.3 | |

| #5 | 1250 | 1356.2 | 7.1 | 108.5 | |

| #6 | 1250 | 1141.6 | 8.5 | 91.3 | |

| 3,4-DHPVL (207 → 163) | #1 | 2500 | 2645.8 | 7.9 | 105.8 |

| #2 | 2500 | 2321.7 | 2.5 | 92.9 | |

| #3 | 2500 | 2607.7 | 5.8 | 104.3 | |

| #4 | 2500 | 2765.0 | 14.3 | 110.6 | |

| #5 | 2500 | 2591.2 | 6.6 | 103.6 | |

| #6 | 2500 | 2844.3 | 8.0 | 113.8 | |

| creatinine (114 → 86) | #1 | 1200 | 1237.3 | 4.6 | 103.1 |

| #2 | 1200 | 1239.5 | 3.6 | 103.3 | |

| #3 | 1200 | 1218.7 | 5.7 | 101.6 | |

| #4 | 1200 | 1203.7 | 9.6 | 100.3 | |

| #5 | 1200 | 1349.7 | 7.0 | 112.5 | |

| #6 | 1200 | 1275.2 | 3.2 | 106.3 | |

3.5. Evaluation of the Wet and Dry Stability of Analytes

Precision and accuracy were measured after the samples were dried on the sample plate and kept 1 h at room temperature to assess dry stability and after the urine extract (PVLs) or dilution (creatinine) was kept 1 week at 4 °C to check the wet stability. In both cases, the precision and accuracy were similar to the results obtained within run, with CV inferior to 9% and accuracies ranging from 91.2 to 115.5%, indicating that the analytes were stable in these two conditions (Table 5).

Table 5. Wet and Dry Stability Study of PVLs and Creatinine in Urine Extract by LDTD-MS/MSa.

| analyte | stability test | condition | nominal concentration (μg/L) | mean concentration (μg/L) | precision (% CV) | accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-HPVL (191 → 106) | WS (QC-L) | 1 week at 4 °C | 150 | 155.2 | 4.7 | 103.5 |

| WS (QC-M) | 1250 | 1329.1 | 5.9 | 106.3 | ||

| WS (QC-H) | 2250 | 2520.8 | 1.7 | 112.0 | ||

| DS (QC-L) | 1 h at room temperature | 150 | 149.6 | 5.5 | 99.7 | |

| DS (QC-M) | 1250 | 1325.3 | 4.9 | 106.0 | ||

| DS (QC-H) | 2250 | 2410.5 | 3.8 | 107.1 | ||

| 3,4-DHPVL (207 → 163) | WS (QC-L) | 1 week at 4 °C | 472 | 430.4 | 6.5 | 91.2 |

| WS (QC-M) | 2672 | 2548.5 | 7.8 | 95.4 | ||

| WS (QC-H) | 4672 | 5396.0 | 9.0 | 115.5 | ||

| DS (QC-L) | 1 h at room temperature | 472 | 472.1 | 2.4 | 100.0 | |

| DS (QC-M) | 2672 | 2522.7 | 3.0 | 94.4 | ||

| DS (QC-H) | 4672 | 4469.1 | 7.7 | 95.7 | ||

| creatinine (114 → 86) | WS (QC-L) | 1 week at 4 °C | 300 | 291.5 | 7.1 | 97.2 |

| WS (QC-M) | 1200 | 1229.5 | 4.6 | 102.5 | ||

| WS (QC-H) | 3000 | 3015.8 | 5.0 | 100.5 | ||

| DS (QC-L) | 1 h at room temperature | 300 | 300.6 | 8.1 | 100.2 | |

| DS (QC-M) | 1200 | 1178.5 | 3.0 | 98.2 | ||

| DS (QC-H) | 3000 | 2979.2 | 3.3 | 99.3 | ||

Wet stability was abbreviated to WS and dry stability to DS.

3.6. Cross-Validation of the LDTD-MS/MS Methods by UPLC-MS/MS

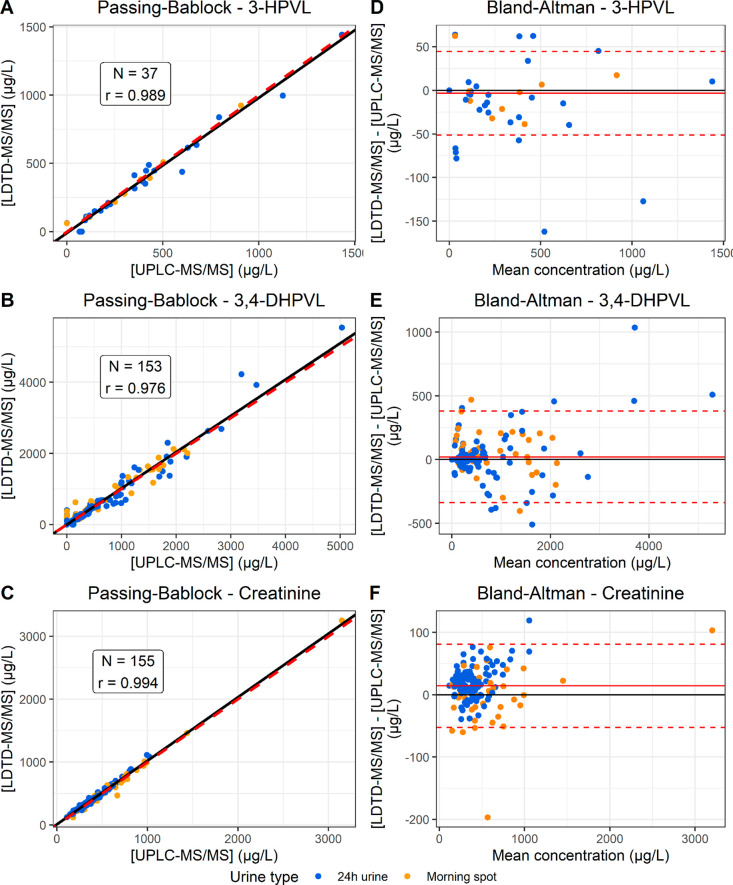

A total of 155 urine samples (41 first morning spot urine samples and 114 24 h urine samples) collected from two clinical trials were analyzed by both LDTD-MS/MS and UPLC-MS/MS to confirm that LDTD-MS/MS is a suitable technology to replace UPLC-MS/MS, the current reference method. To statistically compare the adequation of LDTD-MS/MS with UPLC-MS/MS, Passing–Bablock regression was applied (Figure 3A–C). For the three analytes, all calculated regression lines (represented by black lines) fitted closely the line representing the equivalence between the concentrations measured by LDTD-MS/MS and UPLC-MS/MS (y = x, represented by a dashed red line). Indeed, the parameters of the line y = x (slope equals to 1 and intercept equals to 0) were within the 95% interval confidence of all the analytes, apart from the intercept of creatinine, which was slightly greater than 0 (Table 6), indicating that LDTD-MS/MS provides equivalent results to UPLC-MS/MS. Only urine samples with quantifiable concentrations were included in the Passing–Bablock regression analysis, which explains the difference in the number of observations between the analytes. 3-HPVL was detected in only 37 samples, while 3,4-DHPVL and creatinine were detected in all the samples. Two samples were removed from the analysis of creatinine because their concentration was greater than the upper limit of quantification (4000 μg/L). Bland–Altman plots were used to visualize the distribution of the measurement differences between LDTD-MS/MS and UPLC-MS/MS as a function of the mean concentration (Figure 3D–F). Measurement differences is randomly distributed around 0 for 3-HPVL and 3,4-DHPVL, confirming the absence of systematic bias. For creatinine, LDTD-MS/MS tends to measure slightly higher values than UPLC-MS/MS, which explains the intercept greater than 0.

Figure 3.

Cross-validation by Passing–Bablock regression and Bland–Altman plots. Passing–Bablock regression plots for 3-HPVL (A), 3,4-DHPVL (B) and creatinine (C) and Bland–Altman for 3-HPVL (D), 3,4-DHPVL (E) and creatinine (F) are presented. Each sample is represented by a point of the graph. For the Passing–Bablock plots, the red dashed line represents [LDTD] = [LC] (y = x) and the black line represents the calculated Passing–Bablock regression line. For the Bland–Altman plots, the red full line represents the mean measurement difference, while the red dashed lines represents the mean measurement difference ±2 × standard deviation.

Table 6. Estimates and Confidence Intervals of the Passing–Bablock Regression Parameters.

| estimate |

95%

confidence interval |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| analyte | slope | intercept | slope | intercept |

| 3-HPVL | 0.99 | –9 | [0.92; 1.05] | [−24; 5] |

| 3,4-DHPVL | 1.02 | 0 | [0.98; 1.07] | [−12; 16] |

| creatinine | 1.01 | 11 | [0.98; 1.03] | [3; 20] |

4. Discussion

4.1. Suitability of LDTD-MS/MS to Quantify PVLs and Creatinine in Urine

In this study, we developed a fully automated and high-throughput method to quantify PVLs and creatinine in less than 10 s by LDTD-MS/MS and validated that this new technology was as effective as UPLC-MS/MS. In addition, while enzymatic hydrolysis have been used to facilitate the identification of phase II conjugated metabolites,20−22 this is the first validated method, to our knowledge, to use enzymatic hydrolysis to deconjugate phase II (sulfate and/or glucuronide) PVLs in urine before the quantification of the unconjugated metabolites (3-HPVL and 3,4-DHPVL). Hence, instead of measuring multiple conjugated forms of 3-HPVL and 3,4-DHPVL, only the unconjugated metabolites must be analyzed. Therefore, the comparison of the LOD obtained with LDTD-MS/MS with other validated UPLC-MS/MS is less direct and few studies reported LOD for the unconjugated metabolites. The reported LOD for the quantification in urine by UPLC-MS/MS vary from 270 to 1113 nM for 3-HPVL and from 6.2 to 290 nM for 3,4-DHPVL, while we obtained LOD of 13 nM and 57.7 nM, respectively.23,24 Hence, LDTD-MS/MS displayed a similar sensitivity to UPLC-MS/MS for the analysis of unconjugated PVLs. For sulfated and/or glucuronide derivatives of 3-HPVL and 3,4-DHPVL, the reported LOD are ranging from 1 to 5 nM and from 0.07 to 126.8 nM, respectively.23−26 Similar LOD was obtained by LDTD-MS/MS for the analysis of unconjugated 3-HPVL, but the LOD for unconjugated 3,4-DHPVL is substantially higher. However, this is not an issue because this metabolite was detected in all urine samples included in this study, even in the samples collected during a strict low-(poly)phenols diet. Moreover, the LOD was fixed at 100 nM for sulfated and glucuronide forms of 3,4-DHPVL quantified in the urine samples collected from the EPIC Norfolk cohort.8 Similarly, sensitivity was not an issue for creatinine quantification, because this metabolite was detected in all of the samples after considerable dilution.

However, the gold standard to ensure that a new method is suitable to replace a reference method is the performance of cross-validation on real samples. For the three analytes included in this study, LDTD-MS/MS provided results equivalent to those of UPLC-MS/MS because the 95% interval confidence included a slope of 1 and an intercept with Passing–Bablock regression, except for the intercept of creatinine. In fact, the Bland–Altman plot shows that LDTD-MS/MS seems to overestimate the concentration of creatinine compared to UPLC-MS/MS (Figure 3F). However, this discrepancy is negligible because the mean measurement difference (14 μg/L represented by the full red line) is marginal compared to the mean measured concentration (435 μg/L) with a relative error of 3%. Overall, we demonstrated that LDTD-MS/MS is as valid as UPLC-MS/MS, while it is significantly faster. In addition, cross-validation of the results obtained by LDTD-MS/MS with UPLC-MS/MS confirmed that the enzymatic hydrolysis process was complete. In fact, using LDTD-MS/MS, phase II conjugates are fragmented in the source to release unconjugated PVLs. Because the analytes are not separated prior to the analysis using LDTD, phase II conjugates interfere with the quantification of unconjugated PVLs. Consequently, if the enzymatic hydrolysis was incomplete, concentrations would be overestimated by LDTD-MS/MS compare to those determined by UPLC-MS/MS. This demonstrates the necessity of quantifying PVLs following enzymatic hydrolysis instead of employing authentic phase II conjugated standard. Nevertheless, we advise those who plan to use this method in the future to first confirm that enzymatic hydrolysis is fully achieved with their chosen enzymes using UPLC-MS/MS, prior to analyzing large collections of samples with LDTD-MS/MS.

4.2. Choice of the Internal Standard: A Compromise between Performance and Cost

Normally, the internal standard used for quantification performed by MS is the deuterated derivative of the analyte because the addition of deuterium atoms allows us to measure it independently of the analyte, while sharing almost exactly the same structure of the analyte. Hence, the analyte and his deuterated derivative are influenced similarly by the matrix effect or other experimental variations, providing great performance for the correction of these effects. However, deuterated derivatives of some specific metabolites, such as PVLs, are either very expensive, commercially unavailable or need to be chemically synthesized. To our knowledge, deuterated derivative of 3-HPVL is commercially unavailable, while 3,4-DHPVL labeled with three deuteriums is really expensive (more than 6800$ USD for 5 mg). Therefore, for this method, multiple affordable deuterated internal standards were assessed for the quantification of PVLs in urine by LDTD-MS/MS (data not shown) and acetaminophen-d4 provided the best accuracy and precision. However, this trade-off led to a reduced performance. Indeed, creatinine analysis, for which the internal standard was creatinine-d3, showed overall better performance than PVLs analysis. For the cross-validation, there was more variation for PVLs than creatinine, as the points were more scattered along the regression line. Nevertheless, acetaminophen-d4 provided great performance while being commercially available and affordable.

4.3. Automation of the Sample Preparation and High-Throughput Method: Perspective for Future Studies

In addition to reporting a new high-throughput quantification method of PVLs and creatinine, reducing the analysis time of a sample from several minutes to less than 10 s, we completely automated the sample preparation with a robotic liquid handler. Hence, this protocol is ideal for large epidemiological studies. For example, the quantification of PVLs in 5000 urine samples from the EPIC Norfolk cohort was performed over more than 100 days.8 Using our methodology, the automated sample preparation of a batch containing 69 samples, two calibration curves and three sets of QC was done in 51 min, while the LDTD-MS/MS analysis was performed in less than 12 min. Then, because 5000 samples represent approximately 72 batches, the quantification can be performed in nine regular workdays by analyzing eight batches per day, which is considerably faster than UPLC-MS/MS.

Furthermore, this method could also be applied to the rapid screening or stratification of subjects in clinical trials according to their excretion of PVLs in urine. Future studies could also adapt this method to quantify these metabolites in other matrices, such as plasma, feces, or colic effluents from in vitro fermentation systems. In addition, other microbial (poly)phenols metabolites could be quantified simultaneously with PVLs.

LDTD-MS/MS is a promising technology for the rapid quantification of metabolites, allowing analysis in less than 10 s compared to several minutes with UPLC-MS/MS. Hence, we validated that LDTD-MS/MS is suitable to quantify PVLs and creatinine in urine and demonstrated that this new technology provided performance similar to that of UPLC-MS/MS. In addition, enzymatic hydrolysis was applied to the urine samples in order to quantify PVLs with affordable analytical standards. Sample preparation was automated in order to provide a fast, simple, low-cost and readily transferable method. Therefore, the proposed methodology can be easily applied to the analysis of large cohorts.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded, in part, by the NSERC-Diana Food Industrial Chair on prebiotic effects of fruits and vegetables (IRCPJ 531099–17). Financial support to Jacob Lessard-Lord was provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). We thank Integrated Micro-Chromatography Systems (IMCS) for kindly providing the recombinant enzymes and Symrise (former Diana Food) for supplying the cranberry extract capsules used in the two studies. Finally, we would like to acknowledge Dr. Charlène Roussel for her advice in figure conception, Valérie Guay for her guidance in the preparation of the ethical documents and conducting study B, Valentina Cattero for sample collection of study A and INAF platforms for providing access to the analytical instruments used in this work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 3-HPVL

5-(3′-hydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone

- 3,4-DHPVL

5-(3′,4′-dihydroxyphenyl)-γ-valerolactone

- APCI

atmospheric pressure chemical ionization

- CS

calibration standards

- CV

coefficient of variation

- CVD

cardiovascular diseases

- LDTD

laser diode thermal desorption

- LOD

limit of detection

- LOQ

limit of quantification

- PVLs

phenyl-γ-valerolactones

- QC

quality control

- R2

coefficient of determination

- UPLC-MS/MS

ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry

- wwPTFE

water wettable polytertrafluoroethylene

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.jafc.3c03888.

Food and beverage containing flavan-3-ols participants were asked to not consume during study B, daily dose of (poly)phenols provided by cranberry extract used in study B, concentration of the working solutions, transitions used for quantification by UPLC-MS/MS and pseudocode for automated sample preparation for the analysis of PVLs and creatinine (PDF)

Author Contributions

Jacob Lessard-Lord: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing–original draft. Serge Auger: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing. Sarah Demers: Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing. Pier-Luc Plante: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing. Pierre Picard: Resources, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing. Yves Desjardins: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing.

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): Serge Auger, Sarah Demers and Pierre Picard are employed by Phytronix Technologies. Yves Desjardins holds an NSERC-Diana Food Industrial Chair on prebiotic effects of fruit and vegetable polyphenols.

Supplementary Material

References

- Del Rio D.; Rodriguez-Mateos A.; Spencer J. P. E.; Tognolini M.; Borges G.; Crozier A. Dietary (Poly)phenolics in Human Health: Structures, Bioavailability, and Evidence of Protective Effects Against Chronic Diseases. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2013, 18 (14), 1818–1892. 10.1089/ars.2012.4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manach C.; Scalbert A.; Morand C.; Rémésy C.; Jiménez L. Polyphenols: food sources and bioavailability. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2004, 79 (5), 727–747. 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesso H. D.; Manson J. E.; Aragaki A. K.; Rist P. M.; Johnson L. G.; Friedenberg G.; Copeland T.; Clar A.; Mora S.; Moorthy M. V.; et al. Effect of cocoa flavanol supplementation for the prevention of cardiovascular disease events: the COcoa Supplement and Multivitamin Outcomes Study (COSMOS) randomized clinical trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2022, 115, 1490–1500. 10.1093/ajcn/nqac055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell J. A.; Perez-Jimenez J.; Neveu V.; Medina-Remón A.; M’Hiri N.; García-Lobato P.; Manach C.; Knox C.; Eisner R.; Wishart D. S.; Scalbert A. Phenol-Explorer 3.0: a major update of the Phenol-Explorer database to incorporate data on the effects of food processing on polyphenol content. Database 2013, 2013, bat070. 10.1093/database/bat070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviani J. I.; Britten A.; Lucarelli D.; Luben R.; Mulligan A. A.; Lentjes M. A.; Fong R.; Gray N.; Grace P. B.; Mawson D. H.; et al. Biomarker-estimated flavan-3-ol intake is associated with lower blood pressure in cross-sectional analysis in EPIC Norfolk. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17964. 10.1038/s41598-020-74863-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviani J. I.; Schroeter H.; Kuhnle G. G. C. Measuring the intake of dietary bioactives: Pitfalls and how to avoid them. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 2023, 89, 101139. 10.1016/j.mam.2022.101139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnle G. G. C. Nutrition epidemiology of flavan-3-ols: The known unknowns. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 2018, 61, 2–11. 10.1016/j.mam.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottaviani J. I.; Fong R.; Kimball J.; Ensunsa J. L.; Britten A.; Lucarelli D.; Luben R.; Grace P. B.; Mawson D. H.; Tym A.; et al. Evaluation at scale of microbiome-derived metabolites as biomarker of flavan-3-ol intake in epidemiological studies. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9859. 10.1038/s41598-018-28333-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Li Y.; Ma X.; Alotaibi W.; Le Sayec M.; Cheok A.; Wood E.; Hein S.; Young Tie Yang P.; Hall W. L. Comparison between dietary assessment methods and biomarkers in estimating dietary (poly)phenol intake. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 1369. 10.1039/D2FO02755K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong R. Y.; Kuhnle G. G. C.; Crozier A.; Schroeter H.; Ottaviani J. I. Validation of a high-throughput method for the quantification of flavanol and procyanidin biomarkers and methylxanthines in plasma by UPLC-MS. Food Funct. 2021, 12 (17), 7762–7772. 10.1039/D1FO01228B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bynum N. D.; Moore K. N.; Grabenauer M. Evaluation of Laser Diode Thermal Desorption–Tandem Mass Spectrometry (LDTD–MS-MS) in Forensic Toxicology. Journal of Analytical Toxicology 2014, 38 (8), 528–535. 10.1093/jat/bku084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagerdeo E.; Auger S. Rapid screening procedures for a variety of complex forensic samples using laser diode thermal desorption (LDTD) coupled to different mass spectrometers. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2022, 36, e9244 10.1002/rcm.9244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Pede G.; Bresciani L.; Brighenti F.; Clifford M. N.; Crozier A.; Del Rio D.; Mena P. In Vitro Faecal Fermentation of Monomeric and Oligomeric Flavan-3-ols: Catabolic Pathways and Stoichiometry. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2022, 66, 2101090. 10.1002/mnfr.202101090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard-Lord J.; Plante P.-L.; Desjardins Y. Purified recombinant enzymes efficiently hydrolyze conjugated urinary (poly)phenol metabolites. Food & Function 2022, 13 (21), 10895–10911. 10.1039/D2FO02229J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour C.; Villa-Rodriguez J. A.; Furger C.; Lessard-Lord J.; Gironde C.; Rigal M.; Badr A.; Desjardins Y.; Guyonnet D. Cellular Antioxidant Effect of an Aronia Extract and Its Polyphenolic Fractions Enriched in Proanthocyanidins, Phenolic Acids, and Anthocyanins. Antioxidants 2022, 11 (8), 1561. 10.3390/antiox11081561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams K. J.; Pratt B.; Bose N.; Dubois L. G.; St. John-Williams L.; Perrott K. M.; Ky K.; Kapahi P.; Sharma V.; MacCoss M. J.; et al. Skyline for Small Molecules: A Unifying Software Package for Quantitative Metabolomics. J. Proteome Res. 2020, 19, 1447–1458. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.9b00640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koster R. A.; Greijdanus B.; Alffenaar J.-W. C.; Touw D. J. Dried blood spot analysis of creatinine with LC-MS/MS in addition to immunosuppressants analysis. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2015, 407 (6), 1585–1594. 10.1007/s00216-014-8415-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson B.; Örnemark U.. Eurachem Guide: The Fitness for Purpose of Analytical Methods—A Laboratory Guide to Method Validation and Related Topics, 2nd ed.; Eurachem, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dufey F. Derivation of Passing–Bablok Regression from Kendall’s tau. International Journal of Biostatistics 2020, 16, 20190157. 10.1515/ijb-2019-0157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballet C.; Correia M. S. P.; Conway L. P.; Locher T. L.; Lehmann L. C.; Garg N.; Vujasinovic M.; Deindl S.; Löhr J. M.; Globisch D. New enzymatic and mass spectrometric methodology for the selective investigation of gut microbiota-derived metabolites. Chemical Science 2018, 9 (29), 6233–6239. 10.1039/C8SC01502C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia M. S. P.; Rao M.; Ballet C.; Globisch D. Coupled Enzymatic Treatment and Mass Spectrometric Analysis for Identification of Glucuronidated Metabolites in Human Samples. ChemBioChem. 2019, 20 (13), 1678–1683. 10.1002/cbic.201900065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia M. S. P.; Jain A.; Alotaibi W.; Young Tie Yang P.; Rodriguez-Mateos A.; Globisch D. Comparative dietary sulfated metabolome analysis reveals unknown metabolic interactions of the gut microbiome and the human host. Free Radical Biol. Med. 2020, 160, 745–754. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Caro G.; Ordonez J. L.; Ludwig I.; Gaillet S.; Mena P.; Del Rio D.; Rouanet J. M.; Bindon K. A.; Moreno-Rojas J. M.; Crozier A. Development and validation of an UHPLC-HRMS protocol for the analysis of flavan-3-ol metabolites and catabolites in urine, plasma and feces of rats fed a red wine proanthocyanidin extract. Food Chem. 2018, 252, 49–60. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.01.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindani N.; Mena P.; Calani L.; Benzie I.; Choi S.-W.; Brighenti F.; Zanardi F.; Curti C.; Del Rio D. Synthetic and analytical strategies for the quantification of phenyl-γ-valerolactone conjugated metabolites in human urine. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 61 (9), 1700077. 10.1002/mnfr.201700077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Fernández M.; Xu Y.; Young Tie Yang P.; Alotaibi W.; Gibson R.; Hall W. L.; Barron L.; Ludwig I. A.; Cid C.; Rodriguez-Mateos A. Quantitative Assessment of Dietary (Poly)phenol Intake: A High-Throughput Targeted Metabolomics Method for Blood and Urine Samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69 (1), 537–554. 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano R. P.; Mecha E.; Bronze M. R.; Rodriguez-Mateos A. Development and validation of a high-throughput micro solid-phase extraction method coupled with ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry for rapid identification and quantification of phenolic metabolites in human plasma and urine. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1464, 21–31. 10.1016/j.chroma.2016.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.