Abstract

Knowledge of deeply-rooted non-ammonia oxidising Thaumarchaeota lineages from terrestrial environments is scarce, despite their abundance in acidic soils. Here, 15 new deeply-rooted thaumarchaeotal genomes were assembled from acidic topsoils (0-15 cm) and subsoils (30-60 cm), corresponding to two genera of terrestrially prevalent Gagatemarchaeaceae (previously known as thaumarchaeotal Group I.1c) and to a novel genus of heterotrophic terrestrial Thaumarchaeota. Unlike previous predictions, metabolic annotations suggest Gagatemarchaeaceae perform aerobic respiration and use various organic carbon sources. Evolutionary divergence between topsoil and subsoil lineages happened early in Gagatemarchaeaceae history, with significant metabolic and genomic trait differences. Reconstruction of the evolutionary mechanisms showed that the genome expansion in topsoil Gagatemarchaeaceae resulted from extensive early lateral gene acquisition, followed by progressive gene duplication throughout evolutionary history. Ancestral trait reconstruction using the expanded genomic diversity also did not support the previous hypothesis of a thermophilic last common ancestor of the ammonia-oxidising archaea. Ultimately, this study provides a good model for studying mechanisms driving niche partitioning between spatially related ecosystems.

Subject terms: Archaeal genomics, Archaeal evolution, Molecular evolution, Microbial ecology

Non-ammonia oxidising Thaumarachaeota lineages are common in acidic soils, but their evolution is unclear. Here, the authors assemble 15 genomes from deeply rooted Thaumarachaeota in topsoils and subsoils, investigating evolutionary divergence in the family Gagatemarchaeaceae.

Introduction

Many microbial genomes have been released recently due to the advent of culture-independent whole-genome sequencing techniques, including genome-resolved metagenomics. Concurrently, recently developed phylogenomic approaches such as gene tree - species tree reconciliation have enabled the investigation of mechanisms of genome evolution across large evolutionary timescales. These approaches have been applied to understand microbial habitat transitions between different ecosystems1,2, such as from aquatic to terrestrial environments, and dramatic niche transitions between, for example, free-living and host-associated lifestyles3–5. However, the adaptive mechanisms associated with ancestral niche specialisation between spatially closely related ecosystems, such as associated topsoils and subsoils, have not been investigated.

Thaumarchaeota are commonly known for their ammonia oxidation function, which is a crucial step in the global nitrogen cycle6. However, this metabolism appears restricted to a single class within this phylum (Nitrososphaeria), with deeply-rooted Thaumarchaeota lacking potential for ammonia oxidation in soil7–10, hot springs11,12 or marine environments13,14. Instead, these non-ammonia oxidising archaea (non-AOA) Thaumarchaeota produce energy using sulphur and iron-reduction11,12 or utilisation of organic substrates13–15. This Thaumarchaeota diversity offers the opportunity to address open questions in the evolution of the phylum, such as speciation in diverse environments.

The deeply-rooted Group I.1c Thaumarchaeota10 are prevalent in terrestrial ecosystems, particularly in forest soils where they can comprise 20-25% of the archaeal abundance9. Their role in soil ecology is largely unknown, but an analysis of a single representative genome, Fn1, suggested that they are anaerobic heterotrophs15. However, this prediction contradicts the observed aerobic growth of Group I.1c Thaumarchaeota in soil microcosms16. Group I.1c Thaumarchaeota are present in both topsoils and subsoils16,17, with distinct lineages being differentially abundant at different soil depths16. This depth-based niche partitioning provides a strong model for studying the ecological and evolutionary niche specialisation to soil depth in archaea.

Following metagenome assemblies from topsoils and subsoils, we assembled 15 new archaeal genomes and characterised Group I.1c Thaumarchaeota as a novel archaeal family (Candidatus Gagatemarchaeaceae). This family is prevalent in acidic soils and appears to have undergone an early evolutionary divergence, with distinct lineages occupying topsoils and subsoils. The early split between both lineages corresponds with significant genomic differences and specialised metabolisms. A gene tree-species tree reconciliation approach revealed that the early acquisition of novel gene families, followed by extensive gene duplication, drove the genome diversification of these archaea.

Results

Assembly and classification of non-ammonia oxidising Thaumarchaeota genomes

Fifteen Thaumarchaeota metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) that represent novel species of terrestrial archaea based on GTDB relative evolutionary divergence scores were recovered from five topsoils (0–15 cm) and four subsoils (30–60 cm), all acidic (Table 1). These genomes were related to the non-AOA Thaumarchaeota. Thirteen of the new genomes were affiliated with the Group I.1c clade (represented as f_UBA183 in GTDB). Two genomes were classified as members of the uncharacterised f_UBA141 family, a family closely related to the heterotrophic marine Thaumarchaeota (HMT)13,14 (classified as f_UBA57 in GTDB). The ammonia monooxygenase amoA or amoB genes were not detected in any of the 15 genomes using BLASTn18 or BLASTp against custom databases of amoA and amoB sequences19, by GhostKOALA20, or by hmmsearch21 (amoA; PF12942, amoB; PF04744) indicating that these organisms are likely not capable of ammonia oxidation. The newly assembled Thaumarchaeota genomes were of relatively high quality, with average completeness of 70% (range: 49–95%) and average contamination of 2% (range: 0–9%) (Table 1). These genomes were predicted to be at relatively low abundance within their environments, averaging 0.7% (range: 0.1–3.1%) based on metagenomics sequence read recruitment (Table 1, Supplementary Data 1).

Table 1.

Genome characteristics of newly sequenced metagenome-assembled genomes

| Short name | Completeness (%) | Contamination (%) | Relative abundance (%)* | Optimal growth temperature (°C)** | GC% | Adjusted genome size (bp) | Number Contigs | Adjusted CDS number | Environment source | Type of Soil | Soil pH | Soil Depth (cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca. Gagatemarchaeum | ||||||||||||

| AcS1–13 | 70.9 | 0.0 | 0.75 | 37 | 62 | 2.3.E + 06 | 85 | 2596 | Topsoil | Humus-iron podzols | 4.2 | 0–15 |

| AcS1–27 | 71.4 | 0.0 | 0.38 | 36 | 59 | 3.0.E + 06 | 122 | 3234 | Topsoil | Humus-iron podzols | 4.2 | 0–15 |

| AcS1–6 | 85.0 | 5.8 | 0.81 | 38 | 59 | 2.4.E + 06 | 52 | 2554 | Topsoil | Humus-iron podzols | 4.2 | 0–15 |

| AcS4–109 | 82.9 | 1.9 | 0.10 | 37 | 60 | 2.9.E + 06 | 204 | 3124 | Topsoil | Humus-iron podzols | 4.9 | 0–15 |

| AcS5–19 | 89.8 | 2.6 | 0.14 | 34 | 58 | 2.3.E + 06 | 154 | 2639 | Topsoil | Humus-iron podzols | 3.7 | 0–15 |

| AcS9–25 | 53.1 | 3.0 | 0.24 | 36 | 61 | 2.2.E + 06 | 165 | 2782 | Topsoil | Peaty gleyed podzols | 4.4 | 0–15 |

| AcS11–71 | 54.2 | 9.5 | 0.20 | 37 | 60 | 3.4.E + 06 | 1219 | 4973 | Topsoil | Humus-iron podzols | 4.0 | 0–15 |

| Ca. Subgagatemarchaeum | ||||||||||||

| SubAcS9–116 | 95.3 | 1.0 | 0.40 | 39 | 59 | 1.7.E + 06 | 26 | 1886 | Subsoil | Peaty gleyed podzols | 4.9 | 45–60 |

| SubAcS10–18 | 54.1 | 0.0 | 0.47 | 41 | 57 | 4.5.E + 05 | 48 | 527 | Subsoil | Noncalcareous gley | 4.6 | 30–45 |

| SubAcS11–97 | 50.1 | 9.0 | 0.37 | 39 | 57 | 2.5.E + 06 | 398 | 3039 | Subsoil | Humus-iron podzols | 3.9 | 30–45 |

| SubAcS15–15 | 60.7 | 1.0 | 2.35 | 37 | 54 | 2.0.E + 06 | 3 | 2225 | Subsoil | Peaty gleyed podzols | 5.0 | 45–60 |

| SubAcS15–57 | 94.7 | 1.0 | 0.22 | 39 | 56 | 2.2.E + 06 | 151 | 2426 | Subsoil | Peaty gleyed podzols | 5.0 | 45–60 |

| SubAcS15–94 | 48.9 | 0.0 | 3.09 | 41 | 57 | 1.4.E + 06 | 71 | 1594 | Subsoil | Peaty gleyed podzols | 5.0 | 45–60 |

| Heterotrophic Terrestrial Thaumarchaeota | ||||||||||||

| SubAcS9–71 | 74.3 | 1.0 | 0.35 | 33 | 46 | 1.8.E + 06 | 214 | 2009 | Subsoil | Peaty gleyed podzols | 4.9 | 45–60 |

| SubAcS15–91 | 57.6 | 1.0 | 0.17 | 35 | 48 | 3.8.E + 06 | 378 | 4151 | Subsoil | Peaty gleyed podzols | 5.0 | 45–60 |

Genome size and CDS number were adjusted for completeness. More detailed information on all genomes used in this study can be found in Supplementary Data 1. * Relative abundance was based on metagenomic read recruitment to genomes. **Optimal growth temperature was predicted in silico.

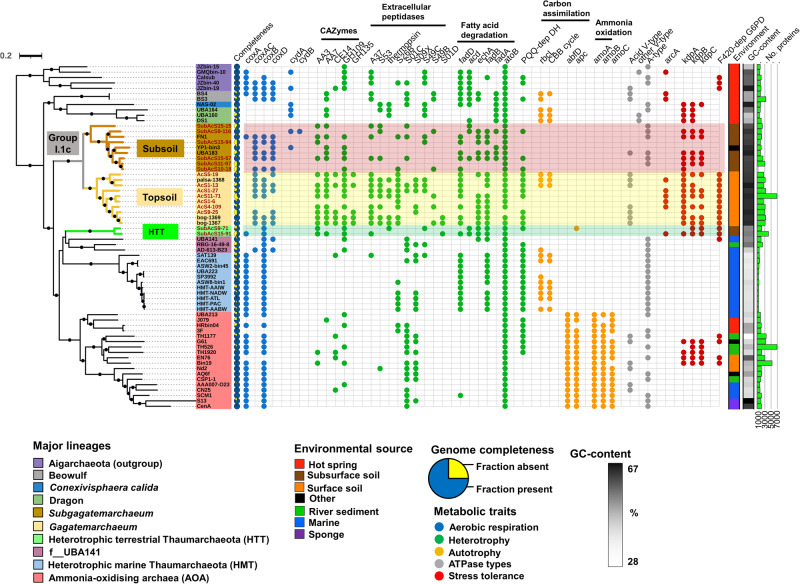

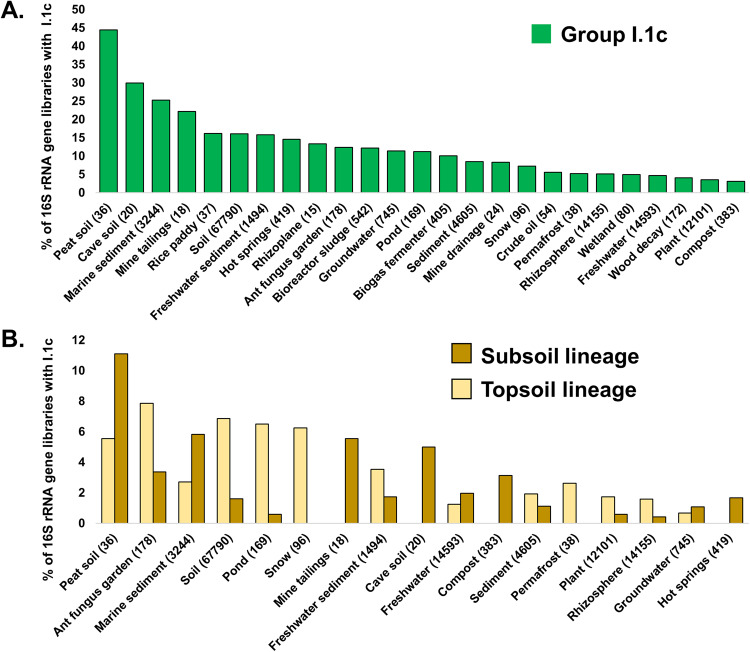

Diversity and prevalence of Group I.1c

The 13 new Group I.1c genomes and the closely related publicly available genomes (Fn1, YP1-bin3, UBA183, palsa-1368, bog-1367 and bog-1369) belong to a single family and represent two genera and 17 species (Supplementary Data 1–3) according to the GTDB-Tk and AAI criteria outlined in the Methods section. The inferred phylogeny of Thaumarchaeota reveals a significant split between lineages occupying topsoils and subsoils, indicating that specialisation in these different habitats occurred early in their evolution (Fig. 1). Based on the current genomic representation, subsequent habitat switching does not appear to have happened since the divergence (Fig. 1). Using representative 16 S rRNA gene sequences from each of the two Group I.1c lineages, it was observed that the Group I.1c family was detected in diverse environments and is particularly prevalent in peat and cave soils (present in 44 and 30% of 16 S rRNA sequencing libraries, respectively) (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Data 4). Subsoil Group I.1c are twice as prevalent as topsoil Group I.1c in peat (11 versus 6%), whereas topsoil Group I.1c are 4-fold more prevalent than subsoil Group I.1c in more than 67,000 soils (7 versus 2%) (Fig. 2B, Supplementary Data 5).

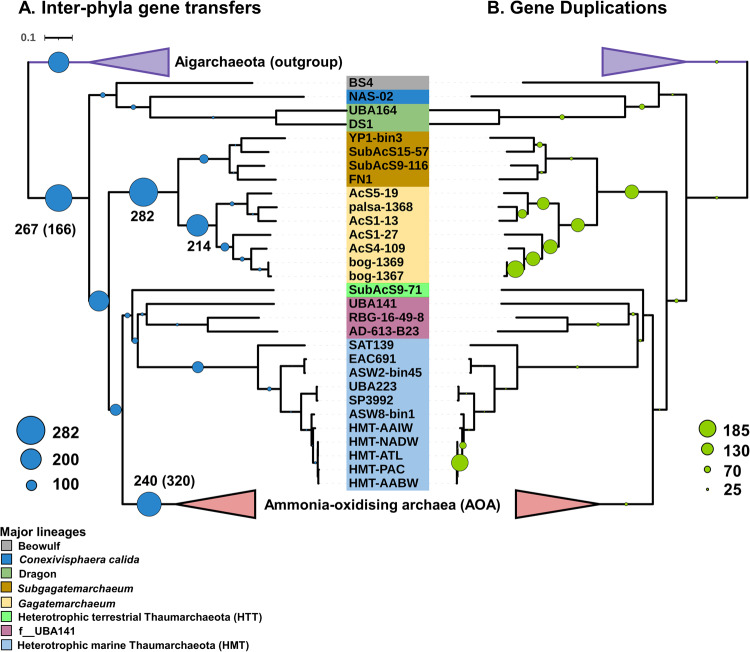

Fig. 1. Phylogenomic tree of Thaumarchaeota and distinctive traits of Gagatemarchaeaceae and Heterotrophic Terrestrial Thaumarchaeota genomes.

This tree comprises the major lineages of Thaumarchaeota, including 19 Gagatemarchaeaceae (previously Group I.1c Thaumarchaeota) genomes and two Heterotrophic Terrestrial Thaumarchaeota (HTT) genomes (Dataset 2). It was inferred by maximum likelihood reconstruction from 76 concatenated single-copy marker genes using the LG + C60 + G + F model. The 15 new genomes obtained in this study are labelled with the prefix “AcS” or “SubAcS” for topsoil and subsoil acidic soils, respectively. Dots indicate branches with 90% UFBoot and SH-aLRT support. The selected genes implicated in key ecosystem functions are: coxA (haem-copper oxygen reductases, subunit A; K02274), coxAC (haem-copper oxygen reductases, fused coxA and coxC subunit; K15408), coxB (haem-copper oxygen reductases, subunit B; K02275), ctaA (haem a synthase; K02259), ctaB (haem o synthase; K02257), cydA (cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase, subunit A; K00425), cydB (cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase, subunit B; K00426), rbcL (ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase large chain; K01601), CBB (Calvin–Benson–Bassham) cycle, abfD (4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase; K14534), apc (acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA carboxylase; K18603), amoABC (ammonia monooxygenase subunits A, B and C; K10944, K10945 and K10946), ATPase types (V/A-type ATPase, subunit A; K02117), arcA (arginine deiminase; K01478), kdpABC (K+ transporting ATPase subunits A, B and C; K01546, K01547 and K01548), F420-dep G6PD (F420-dependent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; K15510) and PQQ-dep DH (PQQ-dependent dehydrogenase; PF13360).

Fig. 2. Distribution of Gagatemarchaeaceae sequences in publicly available 16 S rRNA gene libraries, from a diverse range of environments.

A The assessment of family-level distribution was performed by querying the 16 S rRNA gene of bog-1369 against IMNGS72 for reads of >400 bp that possessed >90% similarity. B The assessment of genus-level distribution was performed by querying the 16 S rRNA genes of bog-1369 (topsoil) and Fn1 (subsoil) against the collection of 16 S rRNA libraries in IMNGS72 for reads >400 bp that possessed >95% sequence similarity. The number of samples of each environment is given in brackets. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Competitive read recruitment of metagenomic reads from the 15 soils (Supplementary Data 6) against Group I.1c genomes revealed that topsoil and subsoil Group I.1c lineages are differentially abundant in the two soil layers (P < 0.01) (Supplementary Data 7), indicating niche partitioning between these diverging lineages. The topsoil lineage dominates the Group I.1c community in topsoil soils, with the subsoil lineage comprising only 10% of the total Group I.1c abundance (Supplementary Fig. 1). The subsoil lineage makes up a significantly higher proportion of the Group I.1c community (41%; P < 0.01) at a depth of 30–45 cm (Supplementary Fig. 1) than in the topsoil environment. The proportion of subsoil lineage appears to increase further at depths of 45–60 cm (76%) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Classification of the acquired Group I.1 c genomes against previously published phylogenetic groups of Group I.1c19 indicates that most Group I.1c topsoil genomes belong to the terrestrial Group I.1c GC1 and GC5 groups (Supplementary Data 8) (Supplementary Fig. 2), which have been shown to grow under aerobic conditions16. In contrast, most Group I.1c subsoil genomes belong to the GC7 group (Supplementary Data 8), which was more abundant in subsoil than in topsoil forest soil previously studied16.

With regards to formal taxonomic classification, we selected the genome bog-1369 as type material for classifying the novel family comprising Group I.1c (henceforth Gagatemarchaeaceae). Bog-1369 and Fn1 genomes were selected as type materials for classifying the novel topsoil (henceforth Gagatemarchaeum) and subsoil (henceforth Subgagatemarchaeum) genera, respectively. These genomes meet the quality criteria for type material suggested for MIMAGs22,23, including high genome completeness ( > 95% complete) and possessing the 5 S, 16 S and 23 S rRNA genes (Supplementary Data 9). Full classification notes are detailed in Supplementary Note 1: Classifications.

Shared metabolism within Gagatemarchaeaceae genomes

None of the Gagatemarchaeaceae genomes possessed the ammonia monooxygenase genes, suggesting that they cannot oxidise ammonia as an energy source (Supplementary Data 10). They lack marker genes of dicarboxylate-hydroxybutyrate, reductive acetyl-CoA and Wood-Ljungdahl carbon fixation pathways and also lack the hydroxypropionate-hydroxybutyrate pathway common in ammonia-oxidising archaea (AOA). Only three topsoil genomes possess the Type III ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase (rbcL) and the ribose 1,5-bisphosphate isomerase (predicted to be involved in thaumarchaeotal RuBisCo11), indicating carbon fixation through the RuBisCo system (Supplementary Data 10). These two genes and the ribose-phosphate pyrophosphokinase were found to be adjacent to each other in these genomes, but all three genes were absent from other members of the family (Supplementary Data 11). Therefore, most Gagatemarchaeaceae likely acquire carbon from organic sources, such as exogenous carbohydrates, amino acids and fatty acids.

Gagatemarchaeaceae encode multiple genes involved in complex carbohydrate degradation, including glycoside hydrolases, carbohydrate esterases and auxiliary activity enzymes (Supplementary Data 12), as well as multiple GH135, GT39 and GH92 genes that possess signal peptides, indicating those that are secreted (Supplementary Data 13). Enzymes of the GH135 and GT39 CAZyme families are involved in the degradation and modification of fungal cell wall components24,25, while GH92 enzymes cleave alpha-mannans (a major component of fungal cell walls)26,27, potentially providing a carbon and nitrogen source for Gagatemarchaeaceae. The family lacks a complete glycolytic pathway, notably lacking key glycolytic gene phosphofructokinase, but could possibly metabolise carbohydrates through the pentose phosphate pathway.

Gagatemarchaeaceae also encode multiple genes involved in peptide degradation (Supplementary Data 14), including several signal peptide-encoding peptidases (Supplementary Data 15). These putatively extracellular enzymes include S01C and S09X family serine peptidases, which are also encoded by several members of the AOA (Supplementary Data 15), and the peptidases S53 and A05 (thermopsin), which are active at low pH28–30. Gagatemarchaeaceae genomes additionally encode the liv branched-chain amino acid transport system and multiple peptide and oligopeptide ABC transporter systems (Supplementary Data 10). They also encode genes for the degradation of amino acids alanine (ala, alanine dehydrogenase), glutamate (gltBD, glutamate synthase), aspartate (aspB, aspartate aminotransferase), serine (ilvA, threonine dehydratase), glycine (glycine cleavage system) and histidine (hutHUI) to precursor metabolites, as well as key genes involved in the degradation of branched-chain amino acids (Supplementary Data 10).

Members of this family also possess several genes involved in the beta-oxidation of fatty acids (Fig. 1), with most of the genomes encoding the long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase (fadD), required for initiated degradation of long-chain saturated and unsaturated fatty acids.

In contrast to the previous investigation of this clade using Fn1 as a representative genome15, the aerobic respiration terminal oxidase (Complex IV) was detected in most Gagatemarchaeaceae genomes (14 of 19 genomes) (Fig. 1), suggesting that aerobic metabolism is common in this family. The complex IV consists of a fused coxA and coxC subunit gene (coxAC), coxB and coxD genes. The coxAC genes of Gagatemarchaeaceae are members of the D- and K-channel possessing A1 subfamily of haem-copper oxygen reductases31. In addition, the microaerobic respiration terminal oxidase, cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidase gene cydA was present in the Subgagatemarchaeum genomes, UBA183 and Fn1 (Fig. 1), suggesting adaptation of these organisms to environments where molecular oxygen is scarce. The cytochrome bd ubiquinol oxidases identified in UBA183 and Fn1 are members of the less common quinol:O2 oxidoreductase families qOR2 and qOR3 respectively, based on the cydA subfamily database32.

Most Gagatemarchaeaceae possess the Kdp potassium transporter (EC:3.6.3.12), which is involved in pH homoeostasis in acidophiles by generating reverse membrane potential33,34. Half of the Gagatemarchaeum genomes encode an arcA arginine deiminase, which is involved in acid tolerance in several bacteria35–37. Additionally, all Gagatemarchaeum encode up to 12 copies of coenzyme F420-dependent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (EC:1.1.98.2), which catalyses the conversion of glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) to 6-phosphogluconolactone, with the subsequent reduction of the cofactor F420 to F420H2, acting as a mechanism of resistance against oxidative stress38 and nitrosative species39,40. Gene tree-species tree reconciliation and single-gene tree analysis of this gene family indicate that the multiple copies arose mainly from multiple progressive gene duplications throughout the evolutionary history of the Gagatemarchaeum (Supplementary Data 16 and 17, and Supplementary Fig. 3). Additionally, single-gene tree analysis indicates a second independent lateral acquisition of F420-dependent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase into the Gagatemarchaeum last common ancestor (LCA) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The high copy number of this gene family in Gagatemarchaeum suggests that these genes are metabolically important in topsoil colonisation.

Pyrroloquinoline quinone (PQQ)-dependent dehydrogenases catalyse the oxidation of a variety of alcohols and sugars41. These genes were highly expressed in marine environments and predicted to play an important physiological role in the heterotrophic marine Thaumarchaeota (HMT)13,14. PQQ-dependent dehydrogenases are also present in most Gagatemarchaeum (Fig. 1), with up to 8 genes per genome. This indicates that these genes may also play an important role in terrestrial non-AOA Thaumarchaeota. As noted for HMT14, the PQQ-dependent dehydrogenases of Gagatemarchaeum tend to be colocalised on the genome, often appearing in adjacent pairs or trios (Supplementary Data 18). The PQQ-dependent dehydrogenases detected in this study formed 11 subfamilies (Supplementary Fig. 4). Four of the eight subfamilies detected in Gagatemarchaeum were also present in HMT13. Interestingly, PQQ-dependent dehydrogenases were also present in genomes of the Nitrososphaerales and Nitrosocaldales lineages of AOA and could indicate an alternative energy source for these highly nutritionally specialised organisms. Gagatemarchaeaceae also lack marker genes of the archaeal, which is present in several AOA lineages42, indicating that they are non-motile.

Gagatemarchaeaceae genomic differences between topsoil and subsoil lineages

Despite the physiological similarities between members of this family, there were notable differences between the topsoil and subsoil lineages. There is strong evidence of lateral gene transfer in the energy-yielding V/A-type H+/Na+-transporting ATPases of these archaea. The topsoil lineages (Gagatemarchaeum) possess the acid-tolerant V-type ATPase and most subsoil lineages (Subgagatemarchaeum) encode the A-type ATPase (Fig. 1, Supplementary Fig. 5). The A-type ATPases have been previously predicted to be the ancestral thaumarchaeotal ATPase, with V-type ATPases being laterally acquired under environmental pressures such as low pH and high pressure43. Our analysis of the expanded Thaumarchaeota dataset supports this hypothesis, with multiple early diverging major lineages encoding the A-type ATPase (Supplementary Fig. 5).

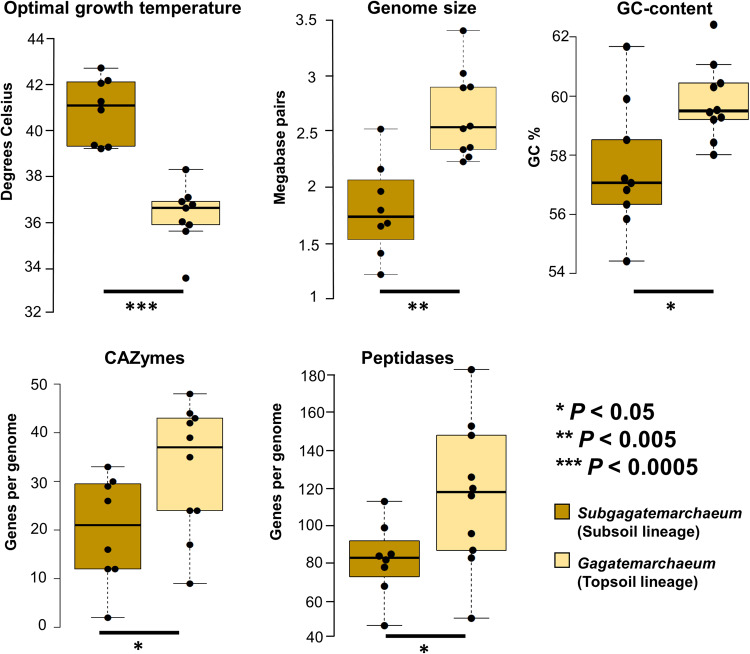

Gagatemarchaeum genomes also possess significantly more CAZymes (involved in carbohydrate degradation) (P < 0.02) and peptidases (involved in peptide degradation) (P < 0.02) than Subgagatemarchaeum genomes (Fig. 3). In addition to functional gene differences, the topsoil and subsoil lineages vary in their genome characteristics. Gagatemarchaeum genomes (median 2.5 Mb; range 2.2–3.4 Mb) are, on average, 47% larger than Subgagatemarchaeum members (median 1.7 Mb; range 1.2-2.5 Mb) (P < 0.001) and have slightly higher GC-content (P < 0.02) (Fig. 3). Additionally, the predicted optimal growth temperature of the Subgagatemarchaeum (average 40.5 °C) was slightly higher than that of Gagatemarchaeum (average 36 °C) (P < 1e−5) (Fig. 3). Values for CAZymes, peptidases and genome size in this comparison have been adjusted by the genome incompleteness.

Fig. 3. Genomic differences between topsoil and subsoil Gagatemarchaeaceae lineages.

Optimal growth temperature (estimated theoretically on the entire proteome) (P = 3.23e−5), genome size (P = 5.15e−4), GC-content (P = 0.02) and CAZyme (P = 0.04) and peptidase (P = 0.03) numbers were compared for the two lineages, with adjustment for genome completeness when required. Dots indicate data points (n = 19 genomes), centre lines show the medians, box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles and whiskers extend 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th percentiles. Significant differences between the two groups were estimated with two-tailed unequal variance (Welch’s) t-tests, with the significance level indicated below each graph. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Metabolism of the heterotrophic terrestrial Thaumarchaeota (HTT) clade

Two newly acquired genomes, representing a novel terrestrial genus related to the HMT and the uncharacterised f_UBA141 family (Fig. 1), lack the gene markers for autotrophic carbon fixation (Supplementary Data 10) and possess genes for carbohydrate, peptide, and fatty acid utilisation (Fig. 1). The coxA gene in SubAcS9-71 is a member of the B subfamily of haem-copper oxygen reductases, in contrast to the A2 subfamily genes found in HMT and the A1 subfamily genes found in AOA and Gagatemarchaeaceae. This indicates that the Complex IV of f_UBA184 and HMT families were independently acquired. HTT also possess acid tolerance genes such as the Kdp potassium transporter (EC:3.6.3.12) present in Gagatemarchaeaceae and terrestrial AOA1 or the arcA arginine deiminase present in Gagatemarchaeum. Two PQQ-dependent dehydrogenases of the 4.1 subfamilies (Supplementary Fig. 4) are present in the HTT genome SubAcS15-91, indicating another heterotrophic energy source for these terrestrial organisms.

Genome evolution of the non-ammonia oxidising Thaumarchaeota

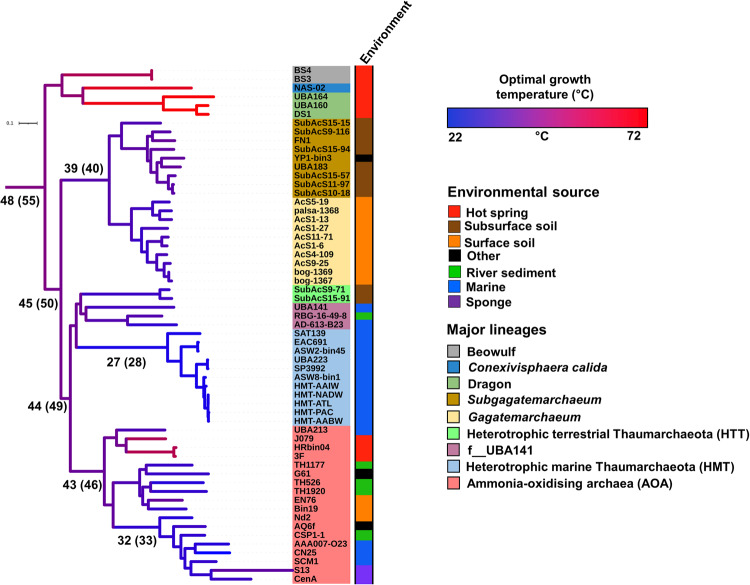

The 15 newly acquired genomes and the recent description of other non-AOA Thaumarchaeota11,13,14 allow us to address some of the open questions about genome evolution in Thaumarchaeota, including the temperature preference of the AOA ancestor (Fig. 4). Ridge regression of extant genome optimal growth temperatures (OGTs) across the thaumarchaeotal species tree indicates that the thaumarchaeotal LCA had an OGT of 48 °C, with a gradual reduction in OGT to 43 °C for the AOA LCA (Fig. 4). Our analysis predicts that the AOA and multiple lineages of non-AOA Thaumarchaeota form a mesophilic clade, except for some thermophilic genomes belonging to the Nitrosocaldales lineage. The non-AOA Thaumarchaeota lineage encompassing the Dragon (DS1, UBA164 and UBA160), Beowulf (BS3 and BS4) and Conexivisphaera calida NAS-02 genomes is sister to this mesophilic clade. This reconstruction supports the hypothesis that the LCA of AOA was a mesophile1, which was hypothesised based on the presence of mesophilic Nitrosocaldales genomes (Thaumarchaeota archaea SAT137 and UBA213) and related non-AOA Thaumarchaeota lineages. The current increased representation of mesophilic non-AOA Thaumarchaeota lineages provides a scenario which contradicts the earlier hypothesis of thermophilic archaeal ammonia oxidation ancestor42,44,45. A previous study predicted the reverse gyrase, rgy, (considered a hallmark enzyme of thermophily in prokaryotes46,47) to be present in the AOA LCA42. However, gene tree analysis indicates that the rgy gene present in the Nitrosocaldales genome J079 (Supplementary Data 10), was acquired recently (Supplementary Fig. 6), consistent with the theory that the AOA LCA was a mesophile.

Fig. 4. Sequence-based prediction of thermal adaptation throughout Thaumarchaeota history.

The optimal growth temperature (OGT) of extant organisms was predicted based on genome sequences using Tome78, with previously demonstrated good correspondence between predicted and empirical values1. Ancestral OGTs were predicted using a ridge regression approach79 across the Thaumarchaeota phylum tree (Dataset 3) using the extant organism OGTs as leaf values. Branches were coloured based on their predicted OGT, and key ancestral OGTs were presented on specific branches. Values presented in parenthesis are included to give overestimated values of OGT (as described in Methods) without altering the conclusion.

The genome GC content varies significantly across the Thaumarchaeota phylum (range 29–67%). The genomes of the HMT clade have a low GC content (range 31–34%), consistent with most lineages of AOA (Fig. 1). GC content is higher in the genomes of the HMT-related clades (GC 46–49%) and even higher in the Gagatemarchaeaceae (range 54–62%). This is consistent with previous observations of higher GC content in terrestrial than related aquatic species48,49.

Evolution of Thaumarchaeota Group I.1c topsoil and subsoil lineages

The Gagatemarchaeaceae have larger genomes than other non-AOA Thaumarchaeota lineages, especially the topsoil lineage - the Gagatemarchaeum (Fig. 1). A gene tree-species tree reconciliation approach was adopted to study the mechanisms influencing the evolution of the Gagatemarchaeaceae family and decipher if the large genome size results from a reduction of the ancestral genome in other lineages or genome expansion in Gagatemarchaeaceae (Supplementary Data 19 and Supplementary Fig. 7). As observed in Nitrososphaerales1 and Cyanobacteria50, genome expansion occurred during the transition into terrestrial environments (Supplementary Fig. 8). Genome expansion was likely initiated by numerous intra- and inter-phyla gene transfers, with the latter being crucial for providing novel metabolic acquisition, enabling environmental transition. Two periods of extensive acquisition of novel gene families (by inter- and intra-phylum gene transfer) were predicted in the early evolution of Gagatemarchaeaceae (Fig. 5A). The first was in the Gagatemarchaeaceae LCA (282 inter- and 342 intra-phylum gene transfers), and the second was in the Gagatemarchaeum LCA (214 inter and 151 intra-phylum gene transfers). ALE51, the reconciliation tool used for inferring these transfers employs a probabilistic model of gene duplication, transfer and loss, averaging over the uncertainty in the gene tree and the uncertainty in the mapping of gene tree branches to the species tree (the reconciliation). Inferred numbers of events therefore represent averages of over 100 sampled reconciliations for each gene family52. While the method accounts for phylogenetic uncertainty, it does make use of topological information so stochastic gene tree error or artifacts such as long branch attraction have the potential to moderately inflate the number of inferred transfers52. High levels of gene duplication were also detected throughout the evolution of the Gagatemarchaeum genus (Fig. 5B), further driving genome expansion. These duplications include the newly acquired gene families, of which 10–20% are present in multiple copies in extant Gagatemarchaeum genomes (Supplementary Data 20).

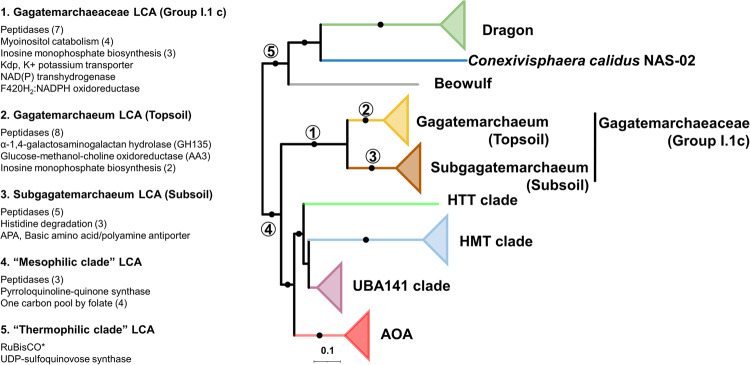

Fig. 5. Acquisition of novel gene families (through inter-phyla gene transfers) and gene duplications along non-AOA Thaumarchaeota lineages.

The quantitative and qualitative predictions of inter-phyla gene transfers (A) and gene duplications (B) were estimated across the Thaumarchaeota phylum tree (Dataset 3) using a gene tree-species tree reconciliation approach as described in the Methods section “Predicting gene content changes across evolutionary history”. Scale numbers indicate the range of the predicted number of events for a given mechanism, and circle sizes are proportional to the number of events.

Gene losses in the Gagatemarchaeaceae lineages were higher than in the rest of the phylum (P < 0.04) (Supplementary Fig. 9), but generally, losses were less punctuated (i.e., events were less concentrated in a small number of species tree branches, as indicated by a lower punctuation score1,2) across the phylum history than the other mechanisms of gene content change (Supplementary Fig. 10). The Gagatemarchaeaceae LCA received a notable influx of genes through lateral transfer from other members of the Thaumarchaeota (342 genes) (Supplementary Fig. 9). Over a third (38%) of these incoming genes were predicted to have been transferred from the lineages f_UBA-141 and HTT (Supplementary Data 21).

The Gagatemarchaeaceae LCA gained many key genes relevant for their adaptation to soil environments, including seven peptidases (families S33, S09X, M95, N11, S33, M50B and M03C) and four genes involved in the utilisation of myo-inositol (iolB, C, E and G), an abundant chemical in soil that can be used as a sole carbon source by diverse bacteria53 (Fig. 6). This LCA also gained three genes involved in inosine monophosphate biosynthesis (purD, H and M), which metabolically link the pentose phosphate pathway and histidine metabolism to the production of purines. The Kdp potassium transporter (EC:3.6.3.12), likely implicated in acidophily, was also acquired by this LCA. Other gene gains in this LCA included the Pnt NAD(P) transhydrogenase (EC:1.6.1.2), which performs the reversible transfer of electrons from NADH to NADP54, and F420H2:NADPH oxidoreductase (EC:1.5.1.40), which transfers electrons from NADPH to oxidised coenzyme F42055 (Fig. 6), indicating an important role for electron transfer between redox cofactors in these organisms.

Fig. 6. Notable functional gene gains during non-AOA Thaumarchaeotal evolution.

The gain of gene families in specific ancestors was predicted by comparing the probabilistic ancestral gene content reconstructions. Dots indicate branches with at least 95% UFBOOT and SH-aLRT support. Circled numbers indicate specific thaumarchaeotal ancestors. The numbers in parentheses correspond to the number of gene families of the named function gained in each ancestor. *The rbcL gene was slightly below the 0.5 reconciliation copies threshold (0.43), but we decided to retain it in the analysis.

The Gagatemarchaeum LCA gained eight peptidases (three S33, S01D, C44, two S09X and S49C), two additional genes involved in inosine monophosphate biosynthesis (purB and E) and the α-1,4-galactosaminogalactan hydrolase (GH135), which is potentially involved in fungal cell wall degradation (Fig. 6). This LCA also gained a member of the Glucose-methanol-choline oxidoreductase family (AA3), while several family members are present in diverse Gagatemarchaeaceae. These enzymes catalyse the oxidation of alcohols or carbohydrates in lignocellulose degradation of wood-degrading fungi56, but their function in archaea has not been studied.

The Subgagatemarchaeum LCA gained the histidine degrading genes hutH, U and I, with the coinciding loss of the histidine biosynthetic genes hisD, F, G and H. Indeed, analysis of extant genomes indicates that this lineage is incapable of biosynthesising histidine (Fig. 6). This suggests that Subgagatemarchaeum uptakes extracellular histidine, which is at least partially used as a source of energy, carbon, and nitrogen. Like the family’s LCA, the Subgagatemarchaeum LCA also gained multiple peptidases (two M38, M32, C26 and S33 family peptidases).

The LCA of the “mesophilic clade” of Thaumarchaeota, which excludes the thermophilic Conexivisphaera, Dragon and Beowulf clades, was predicted to have gained three peptidases (M61, M48B and C26) (Fig. 6). It also gained the PQQ synthase, pqqC, which performs the final steps in PQQ biosynthesis57, reflecting the abundance of PQQ-dehydrogenases in its descendants (Fig. 1). This LCA also gained four genes of the one-carbon metabolic pathway. Notably, both the 5,10-methylene-tetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/cyclohydrolase (FolD) and 10-formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase (Fhs) pathways for N10-formyltetrahydrofolate (metabolite in initiator tRNA and purine nucleotide biosynthesis) production were gained (Fig. 6). In Escherichia coli, fhs provides a selective advantage under anaerobic conditions, particularly in the presence of formate58. Therefore, the possession of both pathways may indicate adaptation to a facultatively anaerobic strategy in the mesophilic clade.

Although the evolution of the more “thermophilic clade” of non-AOA Thaumarchaeota (Conexivisphaera, Dragon and Beowulf) was not studied here in detail due to a lack of representative genomes, its LCA acquired the ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase large chain, rbcL, which was shown previously to classify as a Type III RuBisCO11 (involved in carbon fixation) (Fig. 6). It also acquired a UDP-sulfoquinovose synthase, an essential gene in the production of sulfolipids59, which reduces the microbial phosphate requirements in oligotrophic marine environments60.

Notes

Gagatemarchaeaceae, Gagatemarchaeum and Subgagatemarchaeum are not validly published names under the International Code of Nomenclature of Prokaryotes and thus can be considered as candidatus taxa. The Candidatus prefix was omitted from these taxa in the manuscript for brevity.

Discussion

A previous genomic analysis of a single Gagatemarchaeaceae genome, Fn1, indicated that this group of organisms is anaerobic15. However, subsequent experimental evidence suggested that Gagatemarchaeaceae grow under aerobic conditions in soil16. Our genomic analysis detected the presence of microaerophilic respiration genes in Fn1 and revealed the presence of genes for aerobic respiration in most Gagatemarchaeaceae genomes, corroborating the empirical aerobic growth.

The Gagatemarchaeaceae appears to have undergone an early bifurcation in its evolutionary history, with the Gagatemarchaeum and Subgagatemarchaeum genera adapting to topsoil and subsoil soils, respectively. This divergence corresponds with some notable metabolic and genomic differences between the two lineages. Gagatemarchaeum genomes have significantly more genes for utilising exogenous organic substrates, such as carbohydrates and proteins, than their subsoil sister lineage genomes. They also possess genes for acid tolerance that were absent from the Subgagatemarchaeum genomes. Gagatemarchaeum genome sizes and GC-contents are greater than that of Subgagatemarchaeum, likely due to better adaptation to fluctuating environments61 and involvement with resistance to DNA damage49, respectively. Together, this suggests an adaptation of Gagatemarchaeum to a nutrient-rich but environmentally stressed lifestyle in topsoils, contrasting the Subgagatemarchaeum nutrient-poor lower-stress lifestyle in subsoils.

The larger genomes observed in Gagatemarchaeaceae were driven by early lateral gene acquisition and subsequent gene duplication in topsoil lineages. This paradigm of genome expansion has been observed previously in the terrestrial AOA Nitrososphaerales1, indicating that gene duplication may be a common mode of genome expansion in archaea. This paradigm of early gene acquisition followed by extensive duplication has been proposed as the mechanism through which early eukaryotes increased in complexity, thereby differentiating from their archaeal ancestor62,63. Our work suggests that this paradigm has broader implications than in the archaeal-eukaryote branch of life.

Previous gene tree-species tree reconciliation studies have examined genome evolution during expansion into drastically different ecosystems, such as from aquatic to terrestrial1 or to hypersaline environments3, but this is (to the best of our knowledge) the first study to use these techniques to study transitions into more similar and spatially related ecosystems, representing a majority of the habitat expansions. The phylogenetic approach cannot distinguish if the Gagatemarchaeaceae LCA inhabited a topsoil environment and an early diverging member expanded into subsoil soils or vice versa, but the higher rate of gene family loss between Gagatemarchaeaceae LCA and subsoil genomes might suggest the former, to the extent that the loss of ancestral genes might be associated with habitat shift.

Contrasting theories have been proposed about the thermal preference of the AOA LCA, suggesting either a hyperthermophilic42,44,45 or a mesophilic ancestor1. When initially proposed44, the hyperthermophilic ancestor hypothesis was in good agreement with available data, including an early branching hyperthermophilic AOA (Nitrosocaldus yellowstonii) and hyperthermophilic closest relatives to the Thaumarchaeota. Since then, multiple major lineages of non-AOA Thaumarchaeota mesophiles have been discovered in this work and previously, including Gagatemarchaeaceae15, HMT13,14, HTT and mesophilic Nitrosocaldales1. These mesophilic lineages were not included in this early work44 or some subsequent predictions of AOA LCA thermal preference42,45. Based on this expanded sampling of taxonomically diverse thaumarchaeotal genomes, our predictions suggest that the transition to a mesophilic state occurred earlier in Thaumarchaeota evolution than in the AOA LCA.

Methods

Sampling, sequencing and metagenomic assembled genome creation

Soil samples were collected from nine sites in Scotland (UK) (Supplementary Data 6), and the environmental DNA was extracted using Griffith’s protocol64 with modifications65. DNA libraries were prepared using Illumina TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Library Prep Kit with one µg of environmental DNA. The sequencing was performed on the Illumina NovaSeq S2 platform (9.2 × 1010 bases per sample on average, Macrogen company, Supplementary Data 6), generating 150 bp paired-end reads. Reads were filtered using the READ_QC module66, and high-quality reads for each metagenome were assembled using MEGAHIT67. Binning of resulting contigs was performed with MaxBin268 and metaBAT269, and the results were consolidated using the Bin_refinement module from MetaWRAP66. Completeness and contamination of bins were estimated with CheckM 1.0.1270, and bins with completeness >45% and contamination <10% were retained for further analysis. Genome coverage by metagenomic reads was calculated using CoverM v0.6.1 (https://github.com/wwood/CoverM). The relative abundance of each genome was estimated by competitive read recruitment of metagenomics reads to genome sequences using the Quant_bins module in metaWRAP66. Differences in genome abundance between topsoil and subsoil metagenomes were validated by either one- or two-tailed unequal variance (Welch’s) t-tests. Taxonomic characterisation to genus level was performed using the classify_wf function in GTDB-Tk v1.7.071 using the R202 GTDB release. Average amino acid identities (AAIs) between pairs of genomes were calculated using CompareM (https://github.com/dparks1134/CompareM), and species were defined with AAI thresholds higher than 95%.

Collection of public genomes

Forty-four publicly available thaumarchaeotal genomes were selected from previous literature. This included 19 non-AOA Thaumarchaeota previously used in a detailed thaumarchaeotal phylogenomic analysis1, seven heterotrophic deeply-rooted marine Thaumarchaeota genomes13,14, the Conexivisphaera calida genome12, four genomes classified in GTDB as members of the families f_UBA183 (Gagatemarchaeaceae; Group I.1c) and f_UBA141, and a selection of 18 genomes representing the major lineages of ammonia-oxidising archaea (AOA)1. These genomes were downloaded from NCBI (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Prevalence of Gagatemarchaeaceae in public 16 S rRNA libraries

The bog-1369 and Fn1 genomes were chosen as representative organisms as these genomes meet the quality criteria for type material suggested for MIMAGs22,23, as detailed later in the manuscript. The 16 S rRNA gene of the genome bog-1369 was used to represent the Gagatemarchaeaceae family and queried against the extensive collection of 16 S rRNA gene libraries in IMNGS72 for reads ≥400 bp presenting ≥90% sequence similarity. Additionally, the 16 S rRNA genes of the bog-1369 and Fn1 genomes were used to represent the topsoil and subsoil lineages of Gagatemarchaeaceae, respectively. They were queried against IMNGS for reads ≥400 bp that possessed ≥ 95% sequence similarity. Prevalence was calculated as the percentage of samples of a given environment where Gagatemarchaeaceae was detected.

Group I.1 c Thaumarchaeota classification

The 16 S rRNA gene sequences were extracted from Gagatemarchaeaceae genome sequences using Barrnap v0.9 (--kingdom arc, archaeal rRNA) (https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap) and combined with previously published 16 S rRNA sequences used for a Group I.1c phylogenetic tree19 (https://github.com/SheridanPO-Lab/I.1c-Group). A phylogenetic tree was constructed with IQ-TREE 2.0.373 using the SYM + R5 model. The Gagatemarchaeaceae genomes for which 16 S rRNA genes could be recovered were directly compared to the previously published taxonomic classification. The classification of several Gagatemarchaeaceae genomes without 16 S rRNA gene sequences was inferred based on their phylogenomic relationships to genomes with 16 S rRNA gene sequences.

Determination of genome characteristics

All genomes were annotated using Prokka v1.1474, and GC content and genomic size were calculated using QUAST75. Environmental source information and genome sequence type (i.e. culture, SAG, MAG, etc.) were retrieved from NCBI or associated published studies. Protein novelty1,2, defined as the percentage of encoded proteins that lack a close homologue (e-value < 10 − 5, % ID > 35, alignment length > 80 and bit score > 100) in the arCOG database76, was estimated using Diamond BLASTp77. Optimal growth temperatures (OGT) were predicted in silico for each genome (based on Tome78, which uses a machine-learning model of amino acid dimer abundance in all genes of a genome). OGT in ancestors of extant Thaumarchaeota was inferred with RidgeRace79, which uses ridge regression for continuous ancestral character estimation and uses the Tome predictions as leaf values. RidgeRace was previously used for predicting pH preference in thaumarchaeotal ancestors80. As Tome has been shown to underestimate the OGT of hyperthermophilic organisms1, OGT values for key ancestors were also estimated using a 19 °C-increased OGT for all genomes presenting a predicted OGT greater than 45 °C. The 19 °C value was selected as the highest observed discrepancy between Tome predictions and experimental predictions1.

Gene marker selection and phylogenomic inference

For each dataset, ortholog groups (OGs) were detected using Roary (-i 50, -iv 1.5)81. Core OGs were defined as those present in a single copy in each genome and present in at least 70% of the genomes. Core OGs were aligned individually using MAFFT L-INS-i82, and spurious sequences and poorly aligned regions were removed with trimAl (automated1, resoverlap 0.55 and seqoverlap 60)83. Alignments were removed from further analysis if they presented evidence of recombination using the PHItest84. The remaining alignments were concatenated into a supermatrix for each dataset. Maximum-likelihood trees were constructed for each dataset supermatrix with IQ-TREE 2.0.373 using the complex mixture model LG + C60 + G + F. Branch supports were computed using the SH-aLRT test85 and 2000 UFBoot replicates. A hill-climbing nearest-neighbour interchange (NNI) search was performed to reduce the risk of overestimating branch supports.

Phylogenomic analysis

This study used three separate genome datasets for different analyses (Supplementary Data 22). Dataset 1 consisted of 19 Gagatemarchaeaceae genomes, two UBA141-like genomes and three AOA. Dataset 2 consisted of 64 genomes of Thaumarchaeota and related species (completeness > 45%, contamination < 10%). Dataset 3 consisted of 52 higher-quality genomes of Thaumarchaeota and closely related species (completeness > 70%, contamination <5%). Dataset 2 was used to infer the phylogenomic tree presented in Figs. 1 and 4 (note: The same Group I.1c phylogenetic topology was obtained using Dataset 1). Dataset 3 was used to infer the phylogenomic tree presented in Figs. 5 and 6.

Predicting gene content changes across evolutionary history

For the higher-quality genomes dataset (Dataset 3; 52 genomes, completeness > 70%, contamination < 5%), gene families were inferred with Roary 3.12.081 with low stringency (-i 35, –iv 1.3, –s). Sequences shorter than 30 amino acids and families with less than four sequences were removed from further analysis. All remaining sequences within each family were aligned using MAFFT L-INS-i 7.40782, and poorly aligned sites were removed with trimAl 1.4.1 (“automated1” setting)83. Individual ML phylogenetic trees were constructed for each alignment with IQ-TREE 2.0.373 using the best-fitting protein model predicted in ModelFinder86.

Each gene family tree was probabilistically reconciled against the previously created rooted supermatrix tree (Dataset 3) using the ALEml_undated algorithm of the ALE package51. For the gene family trees being probabilistically reconciled against the species tree (3914 of 3921), this approach allowed inferring the numbers of duplications, intra-LGTs, losses and originations (inter-LGTs) on each branch of the species tree. A 0.5 reconciliation copies threshold1 was used to determine a gene family’s presence in ancestral gene content reconstructions. Genome incompleteness was probabilistically accounted for within ALE using the genome completeness values estimated by CheckM 1.0.1270. The mechanism of gene content change on every branch of the species tree was estimated using branchwise_numbers_of_events.py, as described before1. The number of intra-LGTs transferring into and transferring from every branch of the species tree was estimated with calc_from_to_T.sh, as described before2. All phylogenomic trees were visualised using iTOL87.

Functional annotation of genomes

Genomes were annotated with the KEGG database88 using GhostKOALA20, with the arCOG database76 using Diamond BLASTp77 (best-hit and removing matches with e-value > 10 − 5, % ID < 35, alignment length <80 or bit score <100) and with the Pfam89 database using hmmsearch21 (HMMER v3.2.1) (-T 80). The subfamily classification of cydA was performed using hmmsearch (-T 80) with the cydA subfamily database32. The subfamily classification of coxA genes was performed using the haem-copper oxygen reductase database90. Carbohydrate-active enzymes were annotated using profile HMM from dbCAN (http://bcb.unl.edu/dbCAN2/) (filtered with hmmscan-parser.sh and by removing matches with mean posterior probability < 0.7). Peptidases were annotated using Pfam profile HMMs corresponding to MEROPs families, as described previously91. Extracellular carbohydrate-active enzyme peptidases were identified using Signalp 5.092 (-org arch, archaeal signal peptides) to detect the presence of signal peptides. The presence of motility genes in Gagatemarchaeaceae was initially assessed by the presence of the conserved archaellum subunits C (arCOG05119), D/E (arCOG02964), F (arCOG01824), G (arCOG01822) and J (arCOG01809). The 5 S, 16 S and 23 S rRNA and tRNA genes were identified using Barrnap v0.9 (--kingdom arc, archaeal rRNA) (https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap) and tRNAscan-SE v2.0.593 (-A, archaeal tRNA), respectively. The 16 S rRNA genes from the different genomes were compared by a pairwise analysis using BLASTn v2.9.018.

Single gene tree analysis

To infer a phylogeny for F420-dependent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase genes, an expanded inter-domain set of prokaryotic genomes (Supplementary Data 17) was annotated against the KEGG database88 using GhostKOALA20, and the protein sequences of all genes annotated as F420-dependent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase were extracted and combined with the F420-dependent glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase genes detected in this study. To infer a phylogeny for the Thaumarchaeota PQQ-dependent dehydrogenases, protein sequences were extracted for genes annotated as PQQ-dependent dehydrogenases by their possession of the PF13360 conserved domain. To infer a phylogeny for the V/A-ATPase genes detected in this study, protein sequences of the three largest subunits of V/A-ATPase (atpA, atpB and atpI) extracted from the genomes in Dataset 1 and combined with those analysed in a previous study of Lutacidiplasmatales ATPases2. All subunits were individually aligned and then concatenated into a single partitioned supermatrix. This aligned supermatrix is available at https://github.com/SheridanPO-Lab/I.1c-Group/tree/main/Alignments with the filename “ATPase_supermatrix.aln”.To infer a phylogeny for the reverse gyrase genes detected in the study, protein sequences that possessed the IPR005736 domain were downloaded from UniProt94. These sequences were clustered with CD-HIT95 using an identity threshold of 50%. Representative protein sequences from each cluster and thaumarchaeotal reverse gyrases were combined into a single dataset. Each of these multi-protein sequence datasets were aligned using MAFFT L-INS-i82, and spurious sequences and poorly aligned regions were removed with trimAl (automated1)83. Maximum-likelihood trees were constructed for each alignment with IQ-TREE 2.0.373 using the best-fitting model in ModelFinder86. Branch supports were computed using 1000 UFBoot replicates. A hill-climbing nearest-neighbour interchange (NNI) search was performed to reduce the risk of overestimating branch supports. The resulting trees were rooted using minimal ancestor deviation96. Subfamilies of the Thaumarchaeota PQQ-dependent dehydrogenases were determined by the average pairwise distance between leaves using TreeCluster97.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

UKRI financially supported P.O.S. and Y.M. through the NERC grant (NE/R001529/1). In addition, C.G.-R. and T.A.W. were supported by Royal Society University Research Fellowships (URF150571 and UF140626, respectively). We thank Tony Travis for his support with Biolinux. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support of the Maxwell computer cluster funded by the University of Aberdeen.

Author contributions

P.O.S., T.A.W. and C.G.-R. designed the study and developed the theory. P.O.S. collected the samples and Y.M. performed DNA extraction. P.O.S. assembled the 15 new genomes and performed genomic analyses. P.O.S., T.A.W. and C.G.-R. interpreted the results and wrote the paper. All authors have accepted the final version of the paper.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Accession numbers for the 15 new genomes presented in this study can be found in Supplementary Data 1 and under the NCBI BioProject PRJNA883052. The accession numbers for publicly available genome sequences used in the phylogenomic genome datasets can be found in Supplementary Data 22 and accessions for the expanded inter-domain set of prokaryotic genomes, used for single gene tree analysis, can be found in Supplementary Data 17. Public data is available from NCBI, KEGG, dbCAN, arCOG, PFAM, TIGRFAM and GTDB R202. Source data are provided in this paper.

Code availability

Scripts for general manipulation of ALE outputs have been deposited at https://github.com/Tancata/phylo/tree/master/ALE (10.5281/zenodo.4012549)98, and additional scripts, alignments and phylogenies specific to this work have been deposited at https://github.com/SheridanPO-Lab/I.1c-Group (10.5281/zenodo.8421019)99 and https://github.com/SheridanPO-Lab/ALE_analysis (10.5281/zenodo.8421034)100.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-43196-0.

References

- 1.Sheridan PO, et al. Gene duplication drives genome expansion in a major lineage of Thaumarchaeota. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19132-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheridan PO, Meng Y, Williams TA, Gubry-Rangin C. Recovery of Lutacidiplasmatales archaeal order genomes suggests convergent evolution in Thermoplasmatota. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-31847-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martijn J, et al. Hikarchaeia demonstrate an intermediate stage in the methanogen-to-halophile transition. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19200-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams TA, et al. Integrative modeling of gene and genome evolution roots the archaeal tree of life. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E4602–E4611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618463114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schön, M. E., Martijn, J., Vosseberg, J., Köstlbacher, S. & Ettema, T. J. The evolutionary origin of host association in the Rickettsiales. Nat. Microbiol.7, 1189–1199 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Könneke M, et al. Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature. 2005;437:543–546. doi: 10.1038/nature03911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jurgens G, Lindström K, Saano A. Novel group within the kingdom Crenarchaeota from boreal forest soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997;63:803–805. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.803-805.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bomberg M, Timonen S. Distribution of cren-and euryarchaeota in scots pine mycorrhizospheres and boreal forest humus. Microb. Ecol. 2007;54:406–416. doi: 10.1007/s00248-007-9232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yarwood SA, Bottomley PJ, Myrold DD. Soil microbial communities associated with Douglas-fir and red alder stands at high-and low-productivity forest sites in Oregon, USA. Microb. Ecol. 2010;60:606–617. doi: 10.1007/s00248-010-9675-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber EB, Lehtovirta-Morley LE, Prosser JI, Gubry-Rangin C. Ammonia oxidation is not required for growth of Group 1.1 c soil Thaumarchaeota. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015;91:fiv001. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiv001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beam JP, Jay ZJ, Kozubal MA, Inskeep WP. Niche specialization of novel Thaumarchaeota to oxic and hypoxic acidic geothermal springs of Yellowstone National Park. ISME J. 2014;8:938–951. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato S, et al. Isolation and characterization of a thermophilic sulfur-and iron-reducing thaumarchaeote from a terrestrial acidic hot spring. ISME J. 2019;13:2465–2474. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0447-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aylward FO, Santoro AE. Heterotrophic Thaumarchaea with small genomes are widespread in the dark ocean. Msystems. 2020;5:415. doi: 10.1128/mSystems.00415-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reji L, Francis CA. Metagenome-assembled genomes reveal unique metabolic adaptations of a basal marine Thaumarchaeota lineage. ISME J. 2020;14:2105–2115. doi: 10.1038/s41396-020-0675-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin X, Handley KM, Gilbert JA, Kostka JE. Metabolic potential of fatty acid oxidation and anaerobic respiration by abundant members of Thaumarchaeota and Thermoplasmata in deep anoxic peat. ISME J. 2015;9:2740–2744. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biggs-Weber E, Aigle A, Prosser JI, Gubry-Rangin C. Oxygen preference of deeply-rooted mesophilic thaumarchaeota in forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020;148:107848. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu X, Seuradge BJ, Neufeld JD. Biogeography of soil Thaumarchaeota in relation to soil depth and land usage. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2017;93:fiw246. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vico Oton E, Quince C, Nicol GW, Prosser JI, Gubry-Rangin C. Phylogenetic congruence and ecological coherence in terrestrial Thaumarchaeota. ISME J. 2016;10:85–96. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Morishima K. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 2016;428:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eddy SR. Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998;14:755–763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowers RM, et al. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017;35:725–731. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chuvochina M, et al. The importance of designating type material for uncultured taxa. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 2019;42:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bamford NC, et al. Sph3 is a glycoside hydrolase required for the biosynthesis of galactosaminogalactan in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:27438–27450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.679050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palamarczyk G, Lehle L, Mankowski T, Chojnacki T, Tanner W. Specificity of solubilized yeast glycosyl transferases for polyprenyl derivatives. Eur. J. Biochem. 1980;105:517–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1980.tb04527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu Y, et al. Mechanistic insights into a Ca2-dependent family of α-mannosidases in a human gut symbiont. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2010;6:125–132. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiels P, et al. A bacterial glycosidase enables mannose-6-phosphate modification and improved cellular uptake of yeast-produced recombinant human lysosomal enzymes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:1225–1231. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oda, K., Takahashi, S., Ito, M. & Dunn, B. M. in Aspartic Proteinases 349–353 (Springer, 1998).

- 29.Lin X, Tang J. Purification, characterization, and gene cloning of thermopsin, a thermostable acid protease from Sulfolobus acidocaldarius. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:1490–1495. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)40043-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rawlings ND, Barrett AJ. [13] Evolutionary families of metallopeptidases. Methods Enzymol. 1995;248:183–228. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)48015-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sousa FL, et al. The superfamily of heme–copper oxygen reductases: types and evolutionary considerations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1817:629–637. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murali, R., Gennis, R. B. & Hemp, J. Evolution of the cytochrome bd oxygen reductase superfamily and the function of CydAA’in Archaea. ISME J.15, 3534–3548 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Baker-Austin C, Dopson M. Life in acid: pH homeostasis in acidophiles. Trends Microbiol. 2007;15:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herbold CW, et al. Ammonia‐oxidising archaea living at low pH: Insights from comparative genomics. Environ. Microbiol. 2017;19:4939–4952. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cunin R, Glansdorff N, Pierard A, Stalon V. Biosynthesis and metabolism of arginine in bacteria. Microbiol. Rev. 1986;50:314–352. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.3.314-352.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marquis RE, Bender GR, Murray DR, Wong A. Arginine deiminase system and bacterial adaptation to acid environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987;53:198–200. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.1.198-200.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fulde M, et al. ArgR is an essential local transcriptional regulator of the arcABC operon in Streptococcus suis and is crucial for biological fitness in an acidic environment. Microbiology. 2011;157:572–582. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.043067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurumurthy M, et al. A novel F420‐dependent anti‐oxidant mechanism protects Mycobacterium tuberculosis against oxidative stress and bactericidal agents. Mol. Microbiol. 2013;87:744–755. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manjunatha UH, et al. Identification of a nitroimidazo-oxazine-specific protein involved in PA-824 resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:431–436. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508392103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh R, et al. PA-824 kills nonreplicating Mycobacterium tuberculosis by intracellular NO release. Science. 2008;322:1392–1395. doi: 10.1126/science.1164571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsutani M, Yakushi T. Pyrroloquinoline quinone-dependent dehydrogenases of acetic acid bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018;102:9531–9540. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abby SS, Kerou M, Schleper C. Ancestral reconstructions decipher major adaptations of ammonia-oxidizing archaea upon radiation into moderate terrestrial and marine environments. Mbio. 2020;11:2371. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02371-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang B, et al. Expansion of Thaumarchaeota habitat range is correlated with horizontal transfer of ATPase operons. ISME J. 2019;13:3067–3079. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0493-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De la Torre JR, Walker CB, Ingalls AE, Könneke M, Stahl DA. Cultivation of a thermophilic ammonia oxidizing archaeon synthesizing crenarchaeol. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;10:810–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hua Z, et al. Genomic inference of the metabolism and evolution of the archaeal phylum Aigarchaeota. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05284-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bouthier De La Tour C, et al. Reverse gyrase, a hallmark of the hyperthermophilic archaebacteria. J. Bacteriol. 1990;172:6803–6808. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.6803-6808.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forterre P. A hot story from comparative genomics: reverse gyrase is the only hyperthermophile-specific protein. Trends Genet. 2002;18:236–237. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02650-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reichenberger ER, Rosen G, Hershberg U, Hershberg R. Prokaryotic nucleotide composition is shaped by both phylogeny and the environment. Genome Biol. Evolut. 2015;7:1380–1389. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weissman JL, Fagan WF, Johnson PL. Linking high GC content to the repair of double strand breaks in prokaryotic genomes. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1008493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen M, et al. Comparative genomics reveals insights into cyanobacterial evolution and habitat adaptation. ISME J. 2021;15:211–227. doi: 10.1038/s41396-020-00775-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Szöllősi GJ, Rosikiewicz W, Boussau B, Tannier E, Daubin V. Efficient exploration of the space of reconciled gene trees. Syst. Biol. 2013;62:901–912. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syt054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams, T. A. et al. Parameter estimation and species tree rooting using ALE and GeneRax. Genome Biol Evol. 15, evad134 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Yoshida K, et al. myo-Inositol catabolism in Bacillus subtilis. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:10415–10424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clarke DM, Loo TW, Gillam S, Bragg PD. Nucleotide sequence of the pntA and pntB genes encoding the pyridine nucleotide transhydrogenase of Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 1986;158:647–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eker A, Hessels J, Meerwaldt R. Characterization of an 8-hydroxy-5-deazaflavin: NADPH oxidoreductase from Streptomyces griseus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1989;990:80–86. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4165(89)80015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sützl L, et al. Multiplicity of enzymatic functions in the CAZy AA3 family. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018;102:2477–2492. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-8784-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Puehringer S, Metlitzky M, Schwarzenbacher R. The pyrroloquinoline quinone biosynthesis pathway revisited: a structural approach. BMC Biochem. 2008;9:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-9-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sah S, Aluri S, Rex K, Varshney U. One-carbon metabolic pathway rewiring in Escherichia coli reveals an evolutionary advantage of 10-formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase (Fhs) in survival under hypoxia. J. Bacteriol. 2015;197:717–726. doi: 10.1128/JB.02365-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Güler S, Essigmann B, Benning C. A cyanobacterial gene, sqdX, required for biosynthesis of the sulfolipid sulfoquinovosyldiacylglycerol. J. Bacteriol. 2000;182:543–545. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.2.543-545.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Mooy BA, Rocap G, Fredricks HF, Evans CT, Devol AH. Sulfolipids dramatically decrease phosphorus demand by picocyanobacteria in oligotrophic marine environments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:8607–8612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600540103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bentkowski P, Van Oosterhout C, Mock T. A model of genome size evolution for prokaryotes in stable and fluctuating environments. Genome Biol. Evolut. 2015;7:2344–2351. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koonin EV. Origin of eukaryotes from within archaea, archaeal eukaryome and bursts of gene gain: eukaryogenesis just made easier? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B. 2015;370:20140333. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vosseberg J, et al. Timing the origin of eukaryotic cellular complexity with ancient duplications. Nat. Ecol. Evolut. 2021;5:92–100. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-01320-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Griffiths RI, Whiteley AS, O’Donnell AG, Bailey MJ. Rapid method for coextraction of DNA and RNA from natural environments for analysis of ribosomal DNA- and rRNA-based microbial community composition. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:5488–5491. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.12.5488-5491.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nicol GW, Leininger S, Schleper C, Prosser JI. The influence of soil pH on the diversity, abundance and transcriptional activity of ammonia oxidizing archaea and bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 2008;10:2966–2978. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Uritskiy GV, DiRuggiero J, Taylor J. MetaWRAP—a flexible pipeline for genome-resolved metagenomic data analysis. Microbiome. 2018;6:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0541-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Li D, Liu C, Luo R, Sadakane K, Lam T. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1674–1676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu Y, Simmons BA, Singer SW. MaxBin 2.0: an automated binning algorithm to recover genomes from multiple metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics. 2016;32:605–607. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kang DD, et al. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7359. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 2015;25:1043–1055. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chaumeil, P., Mussig, A. J., Hugenholtz, P. & Parks, D. H. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics36, 1925–1927 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Lagkouvardos I, et al. IMNGS: a comprehensive open resource of processed 16S rRNA microbial profiles for ecology and diversity studies. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep33721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nguyen L, Schmidt HA, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2015;32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seemann T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Archaeal clusters of orthologous genes (arCOGs): an update and application for analysis of shared features between Thermococcales, Methanococcales, and Methanobacteriales. Life. 2015;5:818–840. doi: 10.3390/life5010818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. methods. 2015;12:59. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Li G, Rabe KS, Nielsen J, Engqvist MK. Machine learning applied to predicting microorganism growth temperatures and enzyme catalytic optima. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019;8:1411–1420. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kratsch C, McHardy AC. RidgeRace: ridge regression for continuous ancestral character estimation on phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:i527–i533. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gubry-Rangin C, et al. Coupling of diversification and pH adaptation during the evolution of terrestrial Thaumarchaeota. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:9370–9375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419329112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Page AJ, et al. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan genome analysis. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3691–3693. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Katoh K, Toh H. Recent developments in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Brief. Bioinforma. 2008;9:286–298. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbn013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Capella-Gutiérrez S, Silla-Martínez JM, Gabaldón T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1972–1973. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bruen, T. & Bruen, T. PhiPack: PHI Test and Other Tests of Recombination. (McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, 2005).

- 85.Guindon S, et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TK, von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:587. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:127–128. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kanehisa M, Goto S, Kawashima S, Okuno Y, Hattori M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:277. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.El-Gebali S, et al. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D427–D432. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sousa FL, Alves RJ, Pereira-Leal JB, Teixeira M, Pereira MM. A bioinformatics classifier and database for heme-copper oxygen reductases. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e19117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tully BJ. Metabolic diversity within the globally abundant Marine Group II Euryarchaea offers insight into ecological patterns. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07840-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Armenteros JJA, et al. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:420–423. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chan, P. P. & Lowe, T. M. in Gene Prediction 1–14 (Springer, 2019).

- 94.UniProt Consortium. UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D506–D515. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3150–3152. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tria FDK, Landan G, Dagan T. Phylogenetic rooting using minimal ancestor deviation. Nat. Ecol. Evolut. 2017;1:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41559-017-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Balaban M, Moshiri N, Mai U, Jia X, Mirarab S. TreeCluster: clustering biological sequences using phylogenetic trees. PloS ONE. 2019;14:e0221068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sheridan, P. O. et al. Gene duplication drives genome expansion in a major lineage of Thaumarchaeota (tools). 10.5281/zenodo.4012549 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 99.Sheridan, P. O. et al. Group I.1c Thaumarchaeota. 10.5281/zenodo.8421019 (2023).

- 100.Sheridan, P. O. et al. ALE analysis. 10.5281/zenodo.8421034 (2023).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Accession numbers for the 15 new genomes presented in this study can be found in Supplementary Data 1 and under the NCBI BioProject PRJNA883052. The accession numbers for publicly available genome sequences used in the phylogenomic genome datasets can be found in Supplementary Data 22 and accessions for the expanded inter-domain set of prokaryotic genomes, used for single gene tree analysis, can be found in Supplementary Data 17. Public data is available from NCBI, KEGG, dbCAN, arCOG, PFAM, TIGRFAM and GTDB R202. Source data are provided in this paper.

Scripts for general manipulation of ALE outputs have been deposited at https://github.com/Tancata/phylo/tree/master/ALE (10.5281/zenodo.4012549)98, and additional scripts, alignments and phylogenies specific to this work have been deposited at https://github.com/SheridanPO-Lab/I.1c-Group (10.5281/zenodo.8421019)99 and https://github.com/SheridanPO-Lab/ALE_analysis (10.5281/zenodo.8421034)100.