Abstract

Significance:

Glioblastoma (GBM), the most common and lethal primary brain tumor with a median survival rate of only 15 months and a 5-year survival rate of only 6.8%, remains largely incurable despite the intensive multimodal treatment of surgical resection and radiochemotherapy. Developing effective new therapies is an unmet need for patients with GBM.

Recent Advances:

Targeted therapies, such as antiangiogenesis therapy and immunotherapy, show great promise in treating GBM based upon increasing knowledge about brain tumor biology. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals the plasticity, heterogeneity, and dynamics of tumor cells during GBM development and progression.

Critical Issues:

While antiangiogenesis therapy and immunotherapy have been highly effective in some types of cancer, the disappointing results from clinical trials represent continued challenges in applying these treatments to GBM. Molecular and cellular heterogeneity of GBM is developed temporally and spatially, which profoundly contributes to therapeutic resistance and tumor recurrence.

Future Directions:

Deciphering mechanisms of tumor heterogeneity and mapping tumor niche trajectories and functions will provide a foundation for the development of more effective therapies for GBM patients. In this review, we discuss five different tumor niches and the intercellular and intracellular communications among these niches, including the perivascular, hypoxic, invasive, immunosuppressive, and glioma-stem cell niches. We also highlight the cellular and molecular biology of these niches and discuss potential strategies to target these tumor niches for GBM therapy. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 39, 904–922.

Keywords: glioblastoma, glioblastoma niches, tumor niches, cancer niches, niche characterization

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common and deadly brain cancer, as it accounts for 49.1% of all the malignant brain tumors and has a 5-year survival rate of only 6.8% in the United States (Ostrom et al., 2021). Despite aggressive multimodal treatment including surgical resection and radiochemotherapy, patients with GBM, particularly older adult patients, have a poor prognosis of ∼12–15 months and a near-universal recurrence of tumors (Kim et al., 2021; Ostrom et al., 2021). The complexity and heterogeneity of GBM have been proposed to significantly contribute to tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis (Becker et al., 2021).

According to the 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) classification, GBM was classified as the isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)-wild-type diffuse and astrocytic tumors in adults, which are characterized by microvascular proliferation (MVP) or necrosis, presence of TERT promoter mutation, EGFR gene amplification, the gain of whole chromosome 7, and loss of whole chromosome 10 (Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015; Louis et al., 2021). The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) studies also demonstrated the genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic heterogeneity of GBM by classifying four subtypes, proneural, neural, classical, and mesenchymal (Brennan et al., 2013); and subsequently the neural subtype was excluded due to the lack of GBM-specific features (Wang et al., 2018). Recent single-cell transcriptomic analyses provided strong evidence of cellular heterogeneity, plasticity, and hierarchal organization of tumor cells during GBM development that resembles normal brain development (Couturier et al., 2020; Neftel et al., 2019).

Adding to the heterogeneity at the pathological and molecular levels, the presence of different nontumor cells within the tumor microenvironment (TME), profoundly influences the complexity of GBM (Louis et al., 2021; Perrin et al., 2019). The GBM TME comprised a wide variety of non-neoplastic stromal cells and extracellular matrix (ECM), including endothelial cells (ECs), pericytes, infiltrating and resident immune cells, and other glial cell types, which are present in anatomically distinct regions to form the various tumor niches (Lathia et al., 2015; Prager et al., 2020). These microenvironmental niches exhibit dynamic and unique interactions between tumor cells and host cell populations to escape immune surveillance and resist treatment (Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015).

In the clinic, the current treatments are mainly hampered by the occurrence of intra- and intertumoral heterogeneity, which incrementally promotes tumor progression by regulating the communications between the host and tumor cells, the switch between immune stimulation-immune suppression, and the interconversion between glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) and non-GSCs (Chen et al., 2021; Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015; Lathia et al., 2015; Prager et al., 2020).

In this review, we discuss various tumor niches and their interactions within GBM tumors and review the current strategies for targeting these niches in preclinical and clinical research. Particularly, we emphasize how GSCs participate in these niches to promote tumor progression due to their unique characteristics of self-renewal pluripotency and interconversion with non-GSCs (Hira et al., 2018; Zhou et al., 2017).

Perivascular Niche

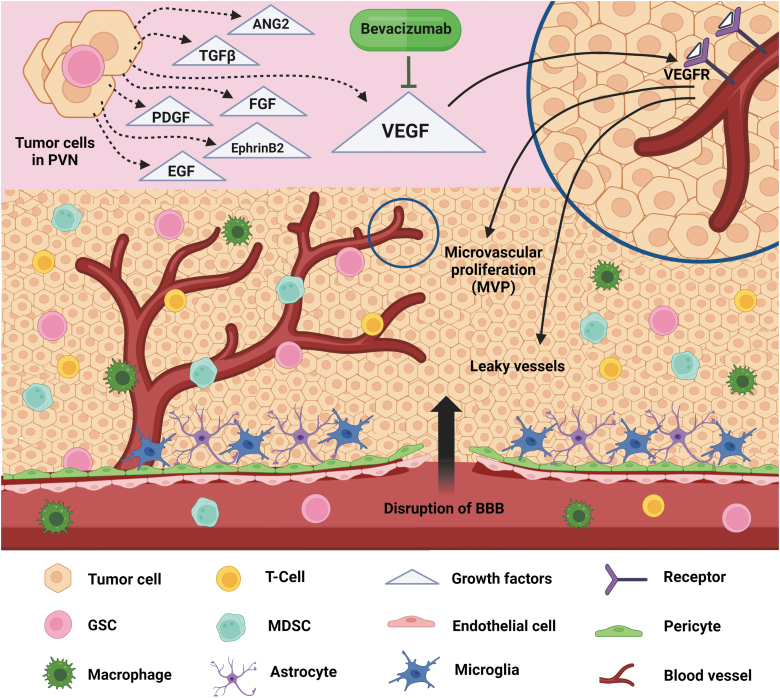

The tumor proliferative zone, where interactions between glioma cells and non-neoplastic cells (e.g., ECs, pericytes) create a specialized tumor vascular environment, is called a perivascular niche (PVN). The features and functions of the PVN include promoting microvascular proliferating structures, maintaining the GSC pool, and homing and recruiting a variety of cell types, such as reactive astrocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (Calabrese et al., 2007; Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015; Wen and Kesari, 2008) (Fig. 1). MVP, the hallmark of GBM, is one of the early indicators of malignant progression and a marker for defining high-grade gliomas (Charles and Holland, 2010). The glioma PVN is considered a prime location for GSCs and can maintain these cells in a self-renewing and undifferentiated state (Calabrese et al., 2007).

FIG. 1.

PVNs in GBM. A PVN is composed of multiple cell types, including glioma cells, GSCs, astrocytes, microglia, TAMs, and MDSCs, which are all localized around a zone of proliferating blood vessels. Hallmarks of the PVN include rapid MVP, leaky blood vessels, and the BBB breaking. Glioma cells and GSCs highly express several growth factors, including VEGF, EGF, FGF, ANG2, TGFβ, ephrinB2, and PDGF, which play pivotal roles in driving PVN formation and expansion. Although bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF drug, was approved by FDA in the clinic, monotherapy or combination therapy with standard treatments demonstrated only a modest benefit for GBM patients. ANG2, angiopoietin-2; BBB, blood–brain barrier; EGF, epidermal growth factor; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; GBM, glioblastoma; GSC, glioblastoma stem cell; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; MVP, microvascular proliferation; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PVN, perivascular niche; TAM, tumor-associated macrophage; TGFβ, transforming growth factor-β; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Indeed, the high density of the PVN regions is associated with the increased number of GSCs, leading to accelerating the initiation and growth of gliomas (Calabrese et al., 2007; Charles and Holland, 2010). The vigorous and abnormal vasculature in GBM gives rise to disorganized and leaky blood vessels, severe hypoxia, and a disrupted blood–brain barrier (BBB), that is formed by ECs, pericytes, and astrocytes, as a transport interface between the peripheral and neuronal tissues (Abbott et al., 2006; Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015). The disrupted BBB allows immune cells, including monocytes, neutrophils, MDSCs, resident microglia, and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), to be recruited to PVN regions and promote glioma growth and progression (Guillemin and Brew, 2004; Kohanbash and Okada, 2012; Liang et al., 2014). Moreover, the brain ECM plays a key role in the PVN formation and progression of GBM.

In the normal brain, the common components of ECM, such as collagens, laminins, and fibronectin, are typically found in the vascular basement membranes, which contribute to the functional and structural integrity of the BBB (Quail and Joyce, 2017; Thomsen et al., 2017). A growing body of evidence shows that the major components of the ECM in GBM, including tenascins, periostin, fibronectin, fibulin-3, heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs), and hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan, HA), serve as critical niche factors in the PVN for promoting GBM proliferation, invasion, vascularization, immunosuppression, and therapy resistance (Mohiuddin and Wakimoto, 2021; Quail and Joyce, 2017).

At the molecular level, several key proangiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), angiopoietin-2 (ANG2), transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ), ephrinB2, and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) ligands, play pivotal roles in driving PVN formation and expansion (Fig. 1) (Dunn et al., 2000; Hermanson et al., 1992; Nakada et al., 2010; Stratmann et al., 1998). The development of neovascularization and the subsequent MVP during rapid tumor growth require glioma cells to release high levels of these proangiogenic factors (Carmeliet and Jain, 2011; Dunn et al., 2000). The ANG2 can bind to the tyrosine kinase (Tie2) receptor to induce the regression of mature vessels due to increased permeability and loss of vascular integrity (Maisonpierre et al., 1997).

It has been shown that ANG2 is involved in a resistance pathway to anti-VEGF treatment in a preclinical model of GBM (Chae et al., 2010), pointing to a potentially effective therapeutic approach by simultaneously targeting ANG2 and VEGF signaling. A high level of TGFβ is correlated with a worse prognosis in patients with glioma (Bruna et al., 2007); TGFβ can also induce VEGF expression in glioma cell lines via an SMAD- and ALK-5-dependent manner (Seystahl et al., 2015). The ephrinB2-EphB4 system plays an essential signaling role in both neoplastic and non-neoplastic vascularization during development (Erber et al., 2006). Increased messenger RNA (mRNA) expression levels of ephrinB2 and its receptor EphB4 were also found and significantly associated with short-term survival in patients with glioma (Erber et al., 2006; Nakada et al., 2010), indicating that ephrinB2/EphB4 upregulation in GBM contributes to PVN formation.

All the PDGF ligands (PDGFA, PDGFB, PDGFC, and PDGFD) were reported to be expressed in glioma (Hermansson et al., 1988; Lokker et al., 2002; Martinho et al., 2009). High levels of these ligands are associated with poor prognosis factors, such as older age and PTEN deletion in GBM patients (Cantanhede and de Oliveira, 2017). Genetically, the major gene amplifications or mutations, such as EGFR/EGFRVIII, PDGFRα, ERBB2, and HGF/MET, are associated with angiogenesis and antiangiogenic resistance in GBM (An et al., 2018; Cruickshanks et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2012).

The matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a large family of zinc-dependent endopeptidases, are enzymes that degrade the structural components of the ECM. Among the MMP family members, MMP2 and MMP9 have been most studied in GBM. MMP2 was reported to be involved in affecting tumor cell survival and tumor invasion by regulating vascular patterning and branching in GBM (Du et al., 2008b). Inhibiting MMP9 expression resulted in attenuation of angiogenesis and tumor growth in GBM-bearing xenograft mouse models (Ezhilarasan et al., 2009; Lakka et al., 2004). Clinical sample analyses showed that a baseline of high and low plasma levels of MMP2 and MMP9, respectively, was associated with a high response rate in recurrent high-grade gliomas treated with bevacizumab (Tabouret et al., 2015; Tabouret et al., 2014). These data suggest that the MMP-mediated ECM degradation process plays a crucial role in the PVN by promoting tumor angiogenesis, progression, and treatment response in GBM.

Clinically, the aggressiveness of tumor angiogenesis in PVN offers a potential target for better treatment in GBM patients. Bevacizumab, a therapeutic monoclonal antibody, was the first VEGFA inhibitor approved for the treatment of recurrent GBM (Table 1). However, the addition of bevacizumab to standard treatments, including radiotherapy and alkylating chemotherapy with temozolomide, demonstrated no increase in overall survival (OS) in patients with GBM (Chinot et al., 2014; Gilbert et al., 2014). A growing body of evidence has shown the various mechanisms of GBM resistance to anti-VEGF therapy (Lu and Bergers, 2013; Lu et al., 2012; Ramezani et al., 2019; Scholz et al., 2016). Inhibition of VEGF signaling can enhance MET activity by recruiting PTP1B to an MET/VEGFR2 complex, leading to antiangiogenic resistance, mesenchymal transformation, and invasion in GBM (Lu et al., 2012).

Table 1.

Pre- or Clinical Trials for Targeting Glioblastoma Niches

| Tumor niche | Promising therapies | Biological action | Combination strategies | Current status | Pre/clinical effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perivascular niche | Bevacizumab | Inhibiting VEGFA | Radiation, temozolomide pembrolizumab | Completed clinical trials | No increase in OS |

| Hypoxic niche | 2ME2 | Inhibiting HIF-1α | Temozolomide | Phase I | Modest antitumor effect as a monotherapy, unknown with temozolomide |

| PT2977 | Inhibiting HIF-2α | N/A | Active, not recruiting (NCT02974738) | N/A | |

| PT2385 | Inhibiting HIF-2α | N/A | Completed clinical trial (NCT03216499) | The results were variable | |

| Invasive niche | RGD | Inhibiting ECM and integrins | N/A | Preclinical | Inhibition of glioma cell migration and anoikis |

| TAE226 | Inhibiting FAK and IGF-IR | N/A | Preclinical | Prolongation of animal survival | |

| IS20I | Inhibiting αvβ3 | N/A | Preclinical | Inhibition of tumor growth | |

| Amphotericin B | Reducing microglia | N/A | Preclinical | Prolongation of animal survival | |

| Targeting WNT5A-GdEC signaling | Promoting existing EC recruitment and GdEC expansion | N/A | Preclinical | Reduction of GBM invasiveness | |

| Immunosuppressive niche | PLX3397 | Inhibiting CSF1R | Radiation, temozolomide | Completed clinical trial (NCT01790503) | No improvement of PFS or OS |

| BLZ945 | Inhibiting CSF1R | Radiation | Preclinical | Significant changes in the dynamics and plasticity of the MDMs and microglia | |

| Gal3BP mimicking peptide | Disrupting CHI3L1-Gal3 protein binding complex | N/A | Preclinical | Reduction of M2-like MDMs but increased M1-like MDMs and CD8+ T cells | |

| CAR2BRAIN | Manipulating NK cells | N/A | Active, not recruiting (NCT02974738) | N/A | |

| Dexamethasone | Anti-inflammatory response | Radiation, temozolomide | Widely used in the clinic | Reduction of tumor-associated edema | |

| GSC Niche | SVZ | Targeting astrocyte-like NSCs at SVZ | Temozolomide | Recruiting (NCT02177578) | N/A |

| SVZ | Targeting astrocyte-like NSCs at SVZ | Stereotactic radiosurgery | Active, not recruiting, (NCT03956706) | N/A | |

| DC vaccination | Autologous DCs loaded with autogeneic GSCs (A2B5+) | Radiation, temozolomide | Recruiting, (NCT01567202) | N/A | |

| DC vaccination | Autologous DCs loaded with autologous tumor-associated antigens | Radiation, temozolomide | Active, not recruiting, (NCT03400917) | N/A | |

| DEN-STEM | DC immunotherapy against GSCs | Temozolomide | Recruiting, (NCT03548571) | N/A | |

| SurVaxM vaccine therapy | Targeting survivin-expressed GSCs | Temozolomide | Active, not recruiting, (NCT02455557) | N/A | |

| IL13Rα2 CAR-T cell therapy | Target GSCs based on IL13Rα2 expression | Ipilimumab nivolumab | Recruiting, (NCT04003649) | N/A |

2ME2, 2-methoxyestradiol; CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; CHI3L1, chitinase-3-like 1; CSF1R, colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor; DC, dendritic cell; EC, endothelial cell; ECM, extracellular matrix; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; Gal3, galectin-3; Gal3BP, galectin-3 binding protein; GBM, glioblastoma; GdEC, GSC-derived endothelial-like cell; GSC, glioblastoma stem cell; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor; MDM, myeloid-derived macrophage; N/A, not application; NK, natural killer; NSC, neural stem cell; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; RGD, Arg-Gly-Asp; SVZ, subventricular zone.

The findings from Lu's study indicate that combined VEGF and MET inhibition can overcome anti-VEGF therapy resistance and block GBM invasion. ANG2 was reported to be elevated in GBM with anti-VEGF treatment, and the ANG2/VEGF bispecific antibody delayed tumor growth and prolonged survival in preclinical glioma mouse models (Chae et al., 2010; Kloepper et al., 2016; Scholz et al., 2016). In addition, preclinical studies showed that the other proangiogenic factors, such as bFGF, TGFα, and PDGFC, were highly upregulated in GBM cells after anti-VEGF therapy, indicating other mechanisms of antiangiogenic resistance and evasion (di Tomaso et al., 2009; Lucio-Eterovic et al., 2009). Targeting VEGF signaling-mediated tumor vascularization in GBM PVN must be accompanied by the inhibition of other proangiogenic factors that are associated with antiangiogenic therapy evasion.

Despite the critical roles of ECM in the PVN, broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors, such as marimastat, have failed in phase III trials for the treatment of GBM patients (Levin et al., 2006). Therefore, it is critical that we gain a better understanding of the mechanistic involvement of MMP-dependent ECM biology in GBM.

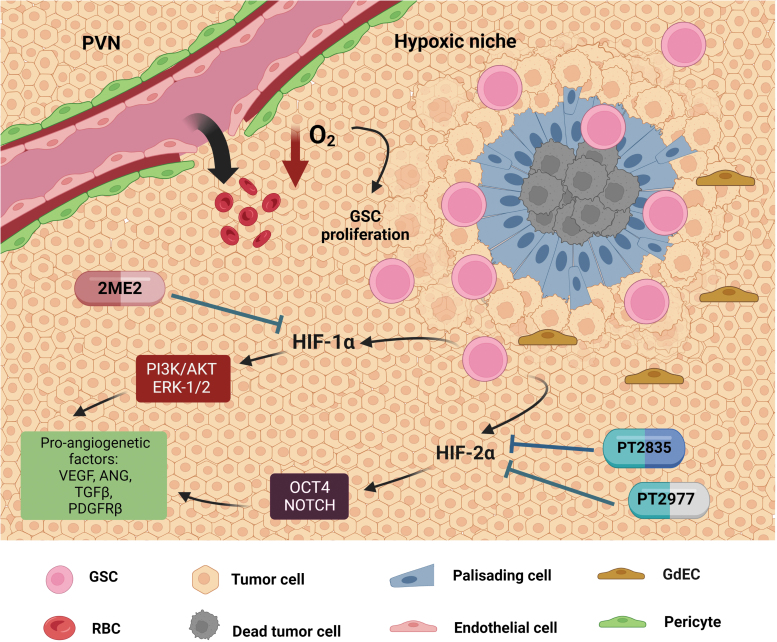

Hypoxic Niche/Perinecrotic Niche

As mentioned above, tumor angiogenesis generates compromised blood vessels due to increased permeability and disrupted basement membrane, which thereby results in inconsistent blood flow and oxygen supply, further creating the pseudopalisading necrotic regions termed the hypoxic or perinecrotic niche in GBM (Fidoamore et al., 2016; Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015) (Fig. 2). Notably, pseudopalisading cells surrounding the necrotic regions are a hallmark of hypoxic niches because they are one of the most powerful predictors of worse patient outcomes and are used to characterize the transition from astrocytoma to GBM (Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015). Glioma cells, GSCs, and ECs are the principal cell types in the hypoxic niche, where outward migration of tumor cells away from hypoxic areas can create pseudopalisading necrosis and microvascular hyperplasia (Rong et al., 2006).

FIG. 2.

Hypoxic niches in GBM. Due to the decrease in oxygen levels from the leaky blood vessels in the PVN, the hypoxic niche originates around the dead tumor cells and has a hallmark feature of palisading cells that surround the necrosis region, thereby increasing the proliferation of GSCs within the region. The hypoxic niche factors HIF-1α and HIF-2α expressed by GSCs contribute to the activation of proangiogenetic factors such as VEGF via the molecular pathways, such as PI3K/AKT, ERK1/2, OCT4, and Notch signaling, which promote tumor progression and invasiveness. In the preclinical and clinical trial studies, 2ME2 (HIF-1α inhibitor), PT2977, and PT2385 (HIF-2α inhibitors) have been observed to reduce the growth of hypoxic niches. 2ME2, 2-methoxyestradiol; HIF, hypoxia-inducible factor.

GSCs preferentially reside in hypoxic and necrotic regions because hypoxia not only maintains stemness and self-renewal of GSCs, but also protects GSCs from radio/chemotherapy (Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015; Seidel et al., 2010). Moreover, the functional involvement of hypoxic niches includes promoting tumor angiogenesis, progression, invasiveness, and immunosuppression, which are predominantly mediated by the hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs) (Boyd et al., 2021; Seidel et al., 2010; Zagzag et al., 2006; Zhou et al., 2015).

The HIF family members belong to the basic helix-loop-helix/PER-ARNT-SIM (bLHL-PAS) subfamily of the heterodimeric transcription factors, including three major oxygen-dependent α subunits (HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and HIF-3α) and a constitutively expressed, oxygen-independent HIF-1β subunit (also known as “ARNT”) (Cowman and Koh, 2022). HIF-1α and HIF-2α have been mostly studied in GBM and their expression in hypoxic niches can activate proangiogenetic factors, such as VEGF, angiopoietin, TGFβ, and PDGFRβ, resulting in tumor angiogenesis and invasiveness (Lee et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2021; Peng et al., 2021; Zagzag et al., 2006).

A plethora of evidence demonstrates that hypoxic niches contribute to stemness, trans-differentiation/plasticity, proliferation, and invasion of the GSCs and are mediated by HIF (Colwell et al., 2017; Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015; Li et al., 2009). For example, HIF-1α or HIF-2α can upregulate GSC-associated stem-like marker genes, such as CD133 upregulation by HIF-1α via the PI3K-Akt or ERK1/2 pathway (Soeda et al., 2009) and HIF-2α upregulates OCT4 and the Notch pathway in GSCs (Seidel et al., 2010) (Fig. 2). A previous study revealed abundant blood vessels with incorporated GSC-derived endothelial-like cells (GdECs) in GBM hypoxic niches, suggesting that hypoxia can promote transdifferentiation of GSCs into an endothelial lineage (Soda et al., 2011). Our previous work also demonstrated that epigenetic activation of WNT5A promotes GdEC lineage differentiation of GSCs, which significantly contributes to tumor invasiveness and recurrence in mouse models and patients with GBM (Hu et al., 2016).

Given the crucial roles of the HIFs in GBM hypoxic niches, targeting HIF-1α or HIF-2α could be significant for patient treatment by decreasing HIF expression levels and/or inhibiting up/downstream signaling activity in the HIF pathways (Table 1). The microtubule-targeting drug 2-methoxyestradiol (2ME2), an inhibitor of HIF-1α, has shown a dose-dependent inhibition of tumor growth in a preclinical animal model (Kang et al., 2006). A clinical trial treating patients with recurrent GBM reported that this drug was well tolerated after oral administration as a monotherapeutic with modest antitumor activity. The combination with temozolomide was also tested (Yang et al., 2012). The combined treatment of 2ME2 and temozolomide within a clinical trial has been conducted, but the data have not been released (Arko et al., 2010).

Two HIF-2α inhibitors, PT2977 and PT2385, have been tested as monotherapies for the treatment of patients with GBM; PT2977 is an ongoing trial in phase one, whereas PT2385 has completed the phase two trial (NCT02974738, NCT03216499) (Sokolov et al., 2021). In addition to decreasing HIF expression levels, targeting HIF signaling pathways also showed profound inhibition of glioma progression. The RAS inhibitor trans-farnesylthiosalicylic acid (FTS) exhibited tumor-suppressive effects in U87 GBM cells (Blum et al., 2005). Inhibition of the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor (IGFR1) by its specific tyrosine kinase inhibitor NVP-AEW541 decreased HIF-1α protein levels and transcriptional activity via STAT3 signaling activation in glioma cells (Gariboldi et al., 2010). These studies support the pharmacologic inhibition of HIFs or HIF signaling activation as a potential strategy to target hypoxic niches for suppressing tumor angiogenesis, survival, and invasiveness in GBM.

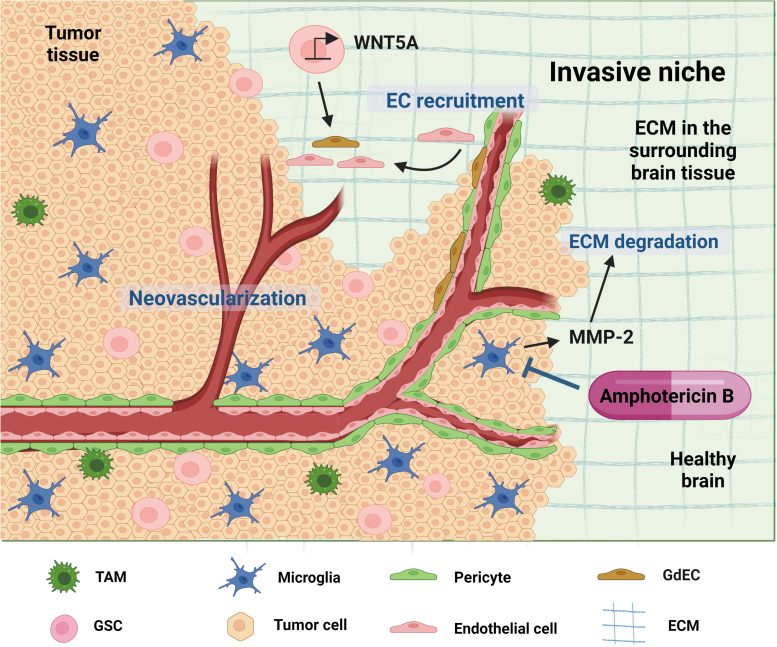

Invasive Niche

Tumor invasiveness is a major contributing factor to disease recurrence, treatment failure, and the worst prognosis for patients with GBM. In 1938, German neuropathologist Hans Joachim Scherer focused on the invasiveness of gliomas by adapting distinct morphological patterns (Scherer, 1938). He categorized distinct tumor patterns as secondary structures of gliomas where invading glioma cells move along the white matter tracts and basement membrane and co-opt normal blood vessels to invade normal brain parenchyma (Diksin et al., 2017; Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015; Scherer, 1938). These secondary structures in GBM are defined as invasive niches, which are generally located at the edge of the tumor mass. Major cell types residing in invasive niches include glioma cells, GSCs, GdECs, ECs, pericytes, activated microglia, and reactive astrocytes (Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015; Hu et al., 2016).

As opposed to PVNs and hypoxic niches with robust angiogenesis, invasive niches may contribute to abnormal neovascularization that supports glioma cell and/or GSC survival outside of those native niches in the peritumoral regions (Hu et al., 2016; Isner and Asahara, 1999). Thus, invasive niches significantly influence incomplete surgical resection and radio/chemotherapy resistance, resulting in tumor recurrence in GBM patients.

We previously discovered a new mechanism of how GSCs, GdECs, and ECs orchestrate an invasive niche supporting GSC growth and survival, thereby promoting tumor cell growth beyond the primary TME (Hu et al., 2016) (Fig. 3). In this model, GSC differentiation into GdEC can stimulate host EC recruitment via WNT5A to create a vascular-like niche supporting distal tumor invasive growth and tumor recurrence. Clinical sample validations further revealed that elevated levels of WNT5A and GdEC signature are correlated with worse progression-free survival (PFS) and tumor recurrence in patients with GBM (Hu et al., 2016). Other features in GBM invasive niches include a local breach of the BBB, the loss of astrocyte–vascular coupling, and seizing control over the regulation of vascular tone, by which invading glioma cells co-opt existing vessels and displace astrocytes from these vessels outside of the main tumor mass (Watkins et al., 2014).

FIG. 3.

The invasive niche in GBM. The invasive niche is characterized by proliferating microvasculature that breaks down the ECM and invades the surrounding healthy brain tissue, beyond the area of the tumor. Major cell types, such as glioma cells, GSCs, GdECs, ECs, pericytes, microglia, and reactive astrocytes, reside in invasive niches. An invasive niche is formed by GSC differentiation into GdECs, which stimulates host EC recruitment via WNT5A to create a vascular-like niche, thereby promoting tumor cell growth beyond the primary tumor microenvironment. Manipulating niche-relevant cell types could be a therapeutic strategy. For instance, amphotericin B, an antifungal drug, shows inhibition of tumor progression by reducing glioma-associated microglia. EC, endothelial cell; ECM, extracellular matrix; GdEC, GSC-derived endothelial-like cell.

In contrast, glioma-reactive astrocytes express numerous proteins at high levels, such as connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), MMP2, and the gap junction protein connexin43 (Cx43), which can participate in the formation of invasive niches for glioma invasion (Edwards et al., 2011; Le et al., 2003; Sin et al., 2016). Furthermore, we and others have reported that brain resident microglia predominantly reside in peritumoral regions as opposed to periphery macrophages that accumulate in intratumoral regions based on mouse glioma models (Chen et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2017). These findings suggest that microglia may play a critical role in GBM invasive niches. Tumor-associated microglia can promote glioma cell invasion into the surrounding brain parenchyma by direct involvement in the degradation of the ECM, which is mediated by the secretion of MMP2 (Markovic et al., 2009; Markovic et al., 2005).

A genetic knockout mouse study also reported that loss of MMP2 altered the model of diffuse glioma growth by causing tumor cells to preferentially move along blood vessels (Du et al., 2008b). Furthermore, integrin-mediated signaling pathways regulate the activities and localization of MMPs, which control ECM degradation during tumor invasiveness. Fox example, high levels of integrin-αvβ3 expression were found to be associated with the GBM invasive phenotype and colocalized with MMP2; αvβ3 binding to MMP2 can promote GBM cell and EC invasion (Bello et al., 2001; Yosef et al., 2018). Other factors secreted by tumor-activated microglia contribute to increased invasiveness of GBM, such as EGF (Coniglio et al., 2012), TGFβ1 (Wesolowska et al., 2008), and the cochaperone stress-inducible protein 1 (STI1) (Carvalho da Fonseca et al., 2014).

Early studies have focused on targeting ECM and integrins to stop glioma cell migration and invasion (Bello et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2007; Russo et al., 2013). The integrin receptor family is the key regulator of cell adhesion and migration maintaining a structural link between ECM and neighboring cells. Integrin-mediated signaling activates focal adhesion kinases (FAKs) and forms an integrin/FAK complex with the actin cytoskeleton and cell adhesion to regulate cell migration (Ellert-Miklaszewska et al., 2020). Therefore, decreased glioma invasiveness was observed by inhibiting either the interactions of ECM and integrins using the tripeptide Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) or activities of integrin/FAK complexes using the inhibitors, TAE226 (an FAK inhibitor) or IS20I (an αvβ3 inhibitor) (Bello et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2007; Russo et al., 2013) (Table 1).

Despite the positive results of targeting ECM and integrins for inhibiting tumor migration and invasion in the preclinical model systems, the clinical applications of these treatment strategies have been unsuccessful (Ellert-Miklaszewska et al., 2020). Given the aforementioned features of invasive niches, unique approaches are required for targeting niche-relevant factors or cell types. For instance, manipulation of the reactive astrocytes by eliminating astrocytic Cx43 led to increased astrogliosis, which is an abnormal increase in the number of astrocytes, and reduction of glioma spreading into the brain parenchyma (Sin et al., 2016). Interestingly, amphotericin B, which is commonly used for antifungal treatment, showed a significant reduction of glioma-associated microglia, leading to prolonged survival in a glioma mouse model (Sarkar et al., 2014).

Importantly, anti-VEGF therapy using bevacizumab may not attenuate the GdEC-mediated invasive niche because increased WNT5A levels promote existing EC recruitment and GdEC expansion to maintain this niche effect during tumor progression (Hu et al., 2016). A previous study revealed that administration of the VEGF receptor inhibitor AG28262 resulted in increased GdECs in the treated mice compared with control mice (Soda et al., 2011). These findings suggest that inhibition of WNT5A signaling may be an effective therapy to target invasive niches for the treatment of recurrent GBM (Hu et al., 2016).

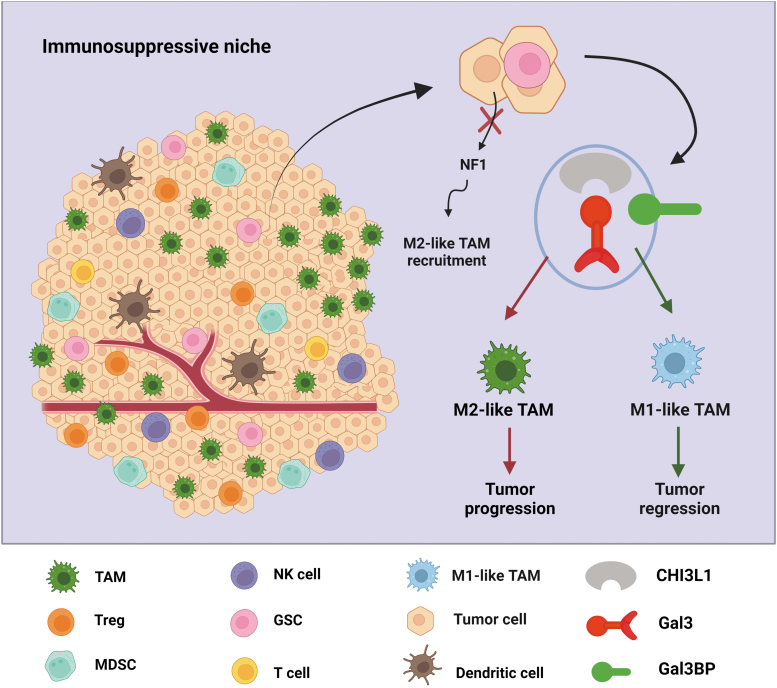

Immunosuppressive Niches

While immunotherapies have been highly effective in some types of cancer, disappointing results from clinical trials for GBM immunotherapy represent our incomplete understanding (Buerki et al., 2018). The tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) of GBM is recognized as highly immunosuppressive and resistant to immunotherapy because glioma cells escape from effective antitumor immunity. A growing body of evidence demonstrates that genetic and epigenetic heterogeneity of GBM promotes the formation of an immunosuppressive niche that includes TAMs, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), MDSCs, dendritic cells (DCs), and regulatory T cells (Tregs) (Pombo Antunes et al., 2020) (Fig. 4). Immunosuppressive niches significantly contribute to the failures of immune-based therapeutics in GBM.

FIG. 4.

Reprogramming TAMs in the GBM immunosuppressive niche. The immunosuppressive niche contains various cells that play a critical role in GBM immunosuppression, such as TAMs, T cells, MDSCs, DCs, and Tregs. NF1 deletions/mutations in glioma cells result in the recruitment of M2-like TAMs. TAMs can also be reprogrammed by cancer-intrinsic CHI3L1 signaling. Mechanistically, CHI3L1 binding with Gal3 modulates TAM polarization toward a protumor M2-like phenotype, leading to tumor progression. However, Gal3BP competes with Gal3 to rescue CHI3L1-Gal3-mediated immunosuppression, resulting in tumor regression. Targeting this competitive interaction could lead to the development of better treatments aimed at reprogramming the immunosuppressive niche. CHI3L1, chitinase-3-like 1; DC, dendritic cell; Gal3, galectin-3; Gal3BP, galectin-3 binding protein; Tregs, regulatory T cells.

Cancer genomic studies revealed a strong correlation between immunosuppression and GBM genetic/epigenetic alterations (Luoto et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2019). As opposed to proneural and classical subtypes of GBM, mesenchymal tumors have enrichment of tumor-promoting M2-like TAMs; and experimental validations showed that NF1 deficiency, a common genetic alteration in mesenchymal GBM, resulted in increased TAM recruitment (Wang et al., 2018). TIL accumulations are strongly associated with mesenchymal GBM harboring mutations in NF1 and RB1 compared with proneural and classical subtypes of GBM with EGFR amplification or homozygous PTEN deletion (Rutledge et al., 2013). Furthermore, tumors with IDH wild-type display higher TIL infiltration and PD-L1 expression compared with IDH mutant tumors that showed reduced expression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated genes and IFN-γ-inducible chemokines, such as CXCL10 (Berghoff et al., 2017; Kohanbash et al., 2017).

The immunosuppressive niches within the GBM are regulated by various immunomodulatory factors (e.g., TGF-b, IL-10, IL-6, and IDO-1), immune checkpoint genes (e.g., TIM-3, LAG-3, PD-1, CTLA-4, and TIGIT), and immunomodulatory surface ligands (e.g., PD-L1 and PD-L2), which are highly expressed in the niche-relevant cell types (Bausart et al., 2022; Himes et al., 2021; Raphael et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2019). TAMs, the major noncancer cell population in the GBM immunosuppressive niches, account for up to 30%–50% of the total tumor composition (Hambardzumyan et al., 2016). TAMs contribute to the GBM immunosuppressive niches by releasing cytokines (such as TGF-b and IL-10) that inhibit T lymphocyte response (Quail and Joyce, 2017; Tomaszewski et al., 2019).

Although increasing evidence suggests that TAMs contribute to GBM progression and treatment response, the classification of M1/M2-like TAM phenotypes and the functional plasticity of TAMs remain an area of active investigation (Gabrusiewicz et al., 2016; Hambardzumyan et al., 2016; Quail and Joyce, 2017). Our recent work demonstrated that a novel protein complex, CHI3L1/galectin-3/galectin-3 binding protein, can reprogram TAM to regulate T cell-mediated immune response in GBM progression (Chen et al., 2021) (Fig. 4). Chitinase-3-like 1 (CHI3L1), also known as human homolog YKL-40, is a secreted glycoprotein with chitin-binding capacity, but lacking chitinase activity, which plays a critical role in tissue remodeling, inflammation, and cancer (Fusetti et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2011).

Galectin-3 (Gal3), a member of the β-galactoside-binding lectin family encoded by the LGALS3 gene, can interact with its binding partner, galectin-3 binding protein (Gal3BP), a secreted glycoprotein encoded by the LGALS3BP gene, to promote cell–cell adhesion and initiate pathological proinflammatory signaling cascades (DeRoo et al., 2015; Filer et al., 2009; Silverman et al., 2012). Our major findings from this study included the following: modulation of TAM polarization toward a protumor M2-like phenotype by the binding of CHI3L1 to Gal3, Gal3BP competes with Gal3 to negatively regulate CHI3L1-Gal3-mediated immunosuppression, and disrupting CHI3L1-Gal3 interaction can promote CD8+ T cell-mediated antitumor immune response (Chen et al., 2021). These findings provided novel mechanistic regulations of the GBM immunosuppressive niches and insights to develop new therapies for GBM patients.

The neutrophilic CD15+ CD14− cells (polymorphnuclear-MDSCs) are the majority of the MDSC population in the GBM immunosuppressive niches, which can promote immunosuppression in glioma by inhibiting the antitumor functions of the other immune cell populations, such as T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, DCs, and Tregs (Mi et al., 2020). The number of TILs in the GBM immunosuppressive niches is not only relatively low but also exhausted by high levels of inhibitory molecules including PD-1, CTLA4, TIM-3, and LAG-3 (Bausart et al., 2022; Woroniecka et al., 2018). Of note, Tregs among TILs are recognized to play a crucial role in the GBM immunosuppressive niches by inhibiting effector T cells and antigen-presenting cells (Bausart et al., 2022; Strepkos et al., 2020).

Although absolute numbers of TILs may not be sufficient to evaluate clinical outcomes in GBM patients, the increased ratios of FoxP3+ Tregs to CD3+, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells are associated with a worse prognosis in this patient population (Sayour et al., 2015). In addition to a low number of TILs, the low levels of other immune cell populations, such as the infiltrating NK cells and B cells, were observed in GBM (Bausart et al., 2022; Kmiecik et al., 2013). Notably, understanding NK cells in GBM became an active investigation. Recent studies revealed that NK cell-mediated tumor regression is blocked by the activities of the αv integrin/TGFβ and the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) DNA sensing pathways in GBM (Berger et al., 2022; Shaim et al., 2021).

While NK cells preferentially kill GSCs rather than normal neural progenitor cells and astrocytes, GBM-infiltrating NK cells express reduced levels of activation receptors, including NKp30, NKG2D, DNAM-1, and CD9, which are downregulated by TGFβ in the GBM TME (Close et al., 2020; Shaim et al., 2021). These findings indicate that targeting the TGFβ signaling pathway to stimulate NK cell activation can potentially be a new immunotherapy approach for patients with GBM. Together, the GBM immunosuppressive niches are maintained by either reprogrammed immune cells or a low density of tumor-infiltrating immune cells, indicating that novel and effective therapy can be achieved by manipulating or increasing these immune cell populations in GBM.

A growing interest in the therapeutic manipulation of the immunosuppressive niches is fueled by numerous discoveries from basic research and early-phase clinical trials in GBM immune-based therapy (Table 1). The strategies for manipulating TAMs include depletion of macrophage numbers, inhibition of tumor-TAM recruitment, and repolarization of protumoral M2-like TAMs into antitumoral M1-like TAMs (Allavena et al., 2021). Among the pharmacologic manipulation of TAMs, the inhibitor of colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R), such as small molecule PLX3397, has been tested in clinical trials for the treatment of GBM patients (Butowski et al., 2016). While PLX3397 was well tolerated in the patients, the results of the trials using monotherapy showed no efficacy (Butowski et al., 2016) and no improvement of median PFS or OS even when combined with radiotherapy and temozolomide in the patients with newly diagnosed GBM (NCT01790503).

A recent preclinical study revealed that CSF1R inhibition using BLZ945 combined with radiotherapy substantially changed the dynamics and plasticity of the myeloid-derived macrophages (MDMs) and microglia, indicating that reprogrammed TAMs are a far more effective influence on tumor progression than depleting TAMs in GBM (Akkari et al., 2020). As aforementioned, our recent work uncovered that the CHI3L1-Gal3-Gal3BP protein binding complexes selectively regulate tumor accumulation and repolarization of MDMs rather than the microglia (Chen et al., 2021). Importantly, pharmacologic disruption of the CHI3L1- Gal3 protein binding complex using our newly developed peptide that mimics the Gal3BP binding motif led to tumor regression in the treated animals aligning with reduced M2-like MDMs but increased M1-like MDMs and CD8+ T cells (Chen et al., 2021). These findings provide insight into the development of new therapeutic manipulation strategies of TAMs in GBM oncology.

Although a number of clinical trials of immune checkpoint blockade therapy either alone or in combination with standard-of-care therapies have been performed over the years, the results from these studies revealed that PFS and OS remain dismal in GBM patients (Lee, 2021; Nayak et al., 2021; Reardon et al., 2020). Similarly, other phase III trials including the CheckMate 498 trial (NCT02617589) and Checkmate 548 trial (NCT02667587) also failed to meet the primary endpoint for improving patient OS with nivolumab combined with temozolomide and/or radiotherapy (Bausart et al., 2022). Therefore, other therapeutic manipulations have been tested in clinical trials using chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cells, DCs, and NK cells. The completed clinical trials include EGFRvIII-specific CAR-T, IL13Rα2-specific CAR-T, and HER2-specific CAR-T, which had limited success (Maggs et al., 2021).

Other ongoing clinical trials are testing CAR-T cell therapy on new targets, such as B7–H3/CD276, CD147, GD2, MMP2, and NKG2D ligands (Maggs et al., 2021). DC-based vaccination therapies have also been tested in GBM clinical trials, including a synthetic peptide stimulated DC vaccine therapy (ICT107) and a DC-based vaccine therapy (DCVaxL) (Liau et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2019a) (Table 1). Although these trials showed promising results in patient safety and tolerability, unidentified reasons led to their discontinuation (Yu and Quail, 2021). Moreover, therapeutically manipulating NK cells as CAR-NK cell therapy has become a novel strategy for targeting GBM immunosuppressive niches. An ongoing CAR2BRAIN clinical trial is currently testing intracranial injection of NK-92/5.28.z cells in patients with recurrent HER2-positive GBM (NCT03383978); the prepreliminary results showed promise with no toxicities reported (Yu and Quail, 2021).

GSCs Within the Tumor Niches

GSCs play a vital role in the evolution of GBM and therapy resistance due to their unique properties that include unlimited self-renewal potential, higher tumorigenic potential, multidifferentiation capability, and higher intrinsic chemo- and radioresistance (Ong et al., 2017; Osuka and Van Meir, 2017). These features of GSCs are endowed and maintained by GSC niches, which have been described as the specific regions where GSCs reside in the tumor and the TME deploys its maximum influence (Schiffer et al., 2018). Within GSC niches, GSCs and GSC-derived progeny directly communicate with their surrounding cells in the different tumor niches, such as ECs in perivascular, hypoxic, and invasive niches, as well as resident microglia and infiltrating immune cells in immunosuppressive niches.

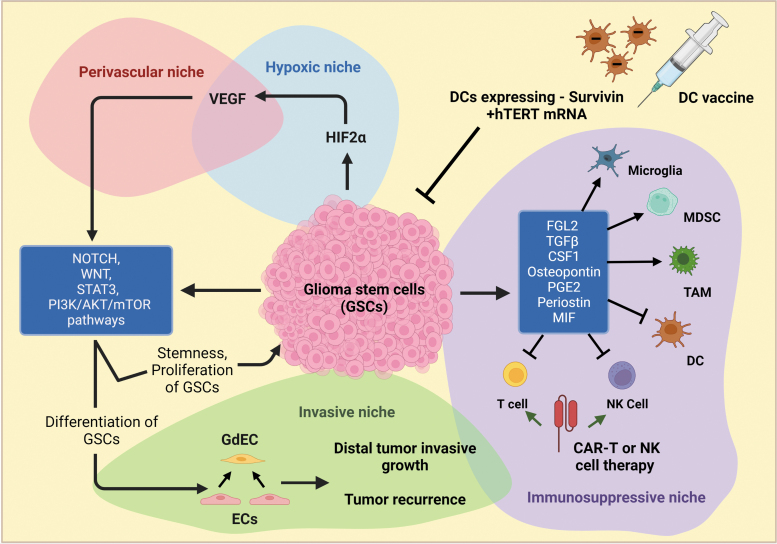

Normal neural stem cells (NSCs) are located close to capillaries where ECs regulate their self-renewal and differentiation (Wurmser et al., 2004). Similarly, GSCs prefer PVNs, which seem to maintain their stemness and growth (Calabrese et al., 2007). GSCs can express high levels of VEGF to support MVP and the subsequent vascular hyperplasia in GBM (Bao et al., 2006b; Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015). Importantly, the plasticity of GSCs contributes to the formation and expansion of the perivascular, hypoxic, and invasive niches in GBM (Fig. 5). Gene mutation and lineage-tracing analyses in mouse models and patient tumors have demonstrated that GSCs are able to differentiate into GdECs that participate in tumor vessel formation (Ricci-Vitiani et al., 2010; Soda et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2010).

FIG. 5.

GSC niches and cross talk with other tumor niches. GSCs highly express HIF2α that upregulates VEGF levels, contributing to the formation and expansion of the perivascular and hypoxic niches. The multiple developmental signaling pathways, such as Notch, WNT, STAT3, and PI3K/AKT/mTOR, regulate GSC stemness, differentiation, and proliferation. GSCs can differentiate into GdECs that participate in the formation of invasive niches by recruiting existing ECs. GSCs also express and secrete the immunomodulators that promote a protumor phenotype in TAMs, microglia, and MDSCs but inhibit antitumor immunity in T cells, DCs, and NK cells. Clinical trials using DC vaccines, CAR-T, or -NK cell therapy to reactivate the antitumor immunity of these cells hold great promise for GBM treatment. CAR, chimeric antigen receptor; NK, natural killer.

However, a previous study using immunofluorescence and fluorescence in situ hybridization assay for double labeling for the endothelial marker CD34 and EGFR gene locus revealed that the incorporation of glioma cells into the tumor vessels is extremely rare in human GBM tumors (Rodriguez et al., 2012). Offering a potential explanation for these observations, we have previously found that GdECs from GSC differentiation mainly participate in the formation of tumor invasive niches by recruiting and expanding host ECs in supporting distal tumor invasive growth, hence tumor recurrence (Hu et al., 2016). As opposed to non-GSCs and normal NSCs, GSCs selectively express high levels of the HIF HIF2α rather than HIF1α, which upregulates VEGF expression and promotes GSC growth (Li et al., 2009).

A previous study reported that ephrinB2 is highly expressed in GSCs, resulting in tumor perivascular invasion; genetic deletion of EFNB2 (encoding EphrinB2) or treatment with an ephrin-B2 blocking antibody in GSCs suppressed GBM progression (Krusche et al., 2016). A growing body of research revealed that GSCs evade immune surveillance by exerting their effect on immunosuppressive niches in GBM. The immunomodulators secreted by GSCs include FGL2, CSF1, TGFβ1, MIF, PGE2, osteopontin, and periostin, which influence periphery macrophages, resident microglia, T cells, DCs, MDSCs, and NK cells within the GBM immunosuppressive niches (Mitchell et al., 2021). A recent study revealed that GSCs can acquire myeloid-affiliated transcriptional programs to establish an enhanced immunosuppressive niche through an epigenetic immunoediting process (Gangoso et al., 2021). Therefore, all evidence suggests that GSCs play an instructive role during GBM evolutionarily trajectory by interacting with other GBM niches.

Given the significant roles of GSCs in GBM development and treatment resistance, developing targeted GSC therapies could offer an unprecedented opportunity for patients with GBM (Table 1). Two active clinical trials (NCT02177578 and NCT03956706) were designed to target astrocyte-like NSCs at the subventricular zone (SVZ) by using temozolomide and stereotactic radiosurgery, respectively, because GBM development was considered to arise from the SVZ cells with low levels of driver mutations (Lee et al., 2018). While directly inhibiting developmental signaling pathways that control GSC stemness, differentiation, and proliferation (e.g., Notch, WNT, STAT3, and PI3K/AKT/mTOR) holds therapeutic promise, extremely rare new therapies have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of GBM patients.

To date, the first bispecific Notch antibody targeting VEGF/DLL4 (navicixizumab) was granted fast-track designation for FDA approval in pretreated ovarian cancer (Christopoulos et al., 2021); several FDA-approved drugs targeting the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways were approved for the treatment of breast cancer (everolimus, alpelisib), chronic lymphocytic leukemia (duvelisib), follicular lymphoma (copanlisib, umbralisib), and advanced renal cell carcinoma (temsirolimus) (Peng et al., 2022). However, none of these FDA-approved drugs was granted use for the treatment of GBM in the clinic due to increased toxicity and no clinical benefits in GBM patients (Chinnaiyan et al., 2018; Wen et al., 2019b; Zhao et al., 2017).

The success of immunotherapy in other solid tumors may provide new hope by developing anti-GSC immunotherapeutics for the treatment of GBM. The early mouse and human studies showed a potential therapeutic effect of DC vaccination (Pellegatta et al., 2006; Vik-Mo et al., 2013). Based on these findings, multiple clinical trials are now being tested by using allogenic GSC lysate-loaded DCs or autologous DC vaccines consisting of autologous DCs loaded with autologous tumor-associated antigens (NCT01567202 and NCT03400917). Furthermore, a trivalent GSC-specific DC vaccine clinical trial is currently underway, targeting GSCs by administering DCs transfected with survivin and hTERT mRNA from autologous tumor stem cells (NCT03548571) because both survivin and hTERT are highly expressed in GSCs (Beck et al., 2011; Nandi et al., 2008).

Another clinical trial is active for targeting survivin-expressed GSCs by using a survivin vaccine (SurVaxM) in combination with temozolomide (NCT02455557). Besides DC-based therapeutic manipulation, CAR-T or -NK cell therapy has been developed to target GSCs based on specific antigen expression, such as IL13Rα2 (Brown et al., 2012; Yu and Quail, 2021). An active clinical trial of IL13Rα2 CAR-T cell therapy is underway in combination with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ipilimumab and nivolumab; NCT04003649).

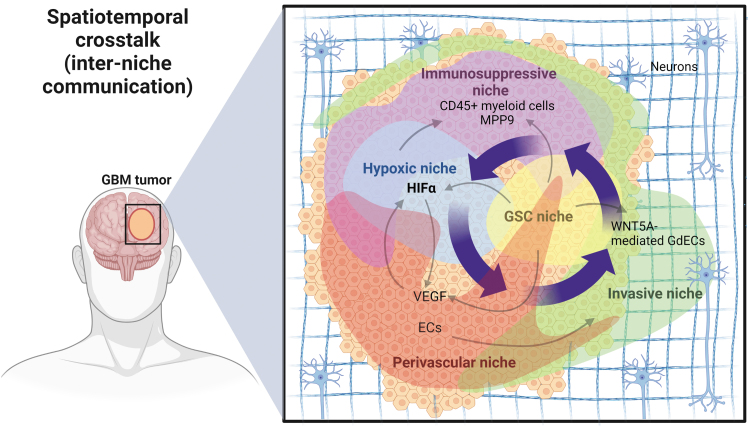

Spatiotemporal Evolution of GBM Niche Interactions

The discussion above describes how the GBM TME, composed of GSCs, non-GSCs, and their surrounding cells, is compartmentalized into anatomically and functionally distinct niches. Accumulating evidence also suggests how these tumor niches interact with each other directly or indirectly to create a heterogeneous and dynamic ecosystem during GBM evolution from tumor initiation and progression to therapeutic resistance and recurrence (Fig. 6). PVNs are responsible for the generation of hypoxic niches, a region with inconsistent blood flow and oxygen supply, which is the result of dilated and leaky blood vessel formation during aberrant angiogenesis. Neovasculature is an integral part of invasive niches, which are associated with vessel cooption to invade deeply in the brain parenchyma (Brooks and Parrinello, 2017).

FIG. 6.

Spatiotemporal cross talk of the tumor niches in GBM. GSC niches play an instrumental role in the various niche interactions. GSCs are preferably located in PVNs and express high levels of VEGF to promote niche growth and expansion, leading to inconsistent blood flow, decreased oxygen supply, and the subsequent hypoxic niche formation. GSCs within hypoxic niches highly express HIF factors to upregulate VEGF for neovasculature and PVN formation. HIF-mediated recruitment of CD45+ myeloid cells and upregulation of MMP9 expression enhance the expansion of immunosuppressive and invasive niches. WNT5A-mediated GdEC differentiation of GSCs and GdEC-mediated recruitment of existing ECs promote invasive niche formation. The invasive niches can merge with the primary tumor mass, subsequently resulting in the formation of new PVNs and hypoxic niches during GBM evolution. MMP, matrix metalloproteinase.

Notably, hypoxic niches induce neovascularization to support the survival of tumor cells, leading to the formation of PVNs. For instance, hypoxia-mediated HIF-1α/HIF-2α upregulates several signaling molecules, including VEGF, placenta-like growth factor (PIGF), PDGFB, and angiopoietins (ANG1 and ANG2), which are involved in orchestrated PVN formation (Kaur et al., 2005; Li et al., 2009). HIF-1α induces zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2), which directly downregulates ephrinB2, leading to promoting invasiveness and resistance to antiangiogenic therapies in GBM (Depner et al., 2016). Furthermore, HIF-1α promotes SDF1a/CXCL12 signaling activation to recruit bone marrow-derived CD45+ myeloid cells in neovascularization and bone marrow-derived MMP9+ cells in tumor invasion in GBM (Du et al., 2008a). With tumor expansion and progression, the GBM invasive niches can merge with the expanding tumor mass, which subsequently triggers the formation of new PVNs and hypoxic niches (Hambardzumyan and Bergers, 2015).

A recent study based on a spatial analysis of immune cells in patient GBM tissues suggests that terminally exhausted CD8+ T cells, Treg cells, and M2-like protumor TAMs are more enriched in the hypoxic niches than the invasive niches (Kim et al., 2022). As mentioned previously, GSC niches play a central role in the GBM microenvironment by multilaterally interacting with other tumor niches. Therefore, GSC niches have been described as perivascular niches, periarteriolar niches, perihypoxic niches, and peri-immune niches (Aderetti et al., 2018). Above all, the evidence demonstrates that these tumor niches engage in spatiotemporal dynamic changes, which creates an evolutionary trajectory of the GBM microenvironment to support tumor progress, treatment resistance, and eventual recurrence.

A plethora of evidence suggests that the plasticity of tumor cells and the transition of tumor niches are linked to the treatment resistance mechanisms. It has become increasingly clear that the standard-of-care therapies significantly alter the tumor niches by promoting cancer cell plasticity during GBM evolution. For example, radio/chemotherapy eventually resulted in increasing the population of GSCs and GSC niche expansion, leading to treatment resistance and tumor recurrence through multiple signaling pathways, including DNA damage checkpoint activation, Notch and Sonic hedgehog (Shh) pathways, and mechanisms involving tumor metabolism (Bao et al., 2006a; Ong et al., 2017; Tamura et al., 2013; Tamura et al., 2010). The temozolomide-mediated chemotherapy resistance correlates with increased hypoxia and elevated expression of chemoresistance markers, HIF-1α, GSC markers, and O6-methylguanine methyltransferase (MGMT) (Pistollato et al., 2010).

Preclinical and clinical data demonstrated that radiotherapy and/or temozolomide can exacerbate GBM immunosuppression, which is mediated by treatment-induced lymphopenia, T cell dysfunction, or immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-6 and IL-10 (Karachi et al., 2018; Pearson et al., 2020). Treatment with anti-inflammatory steroids such as dexamethasone has been shown to upregulate CTLA-4 mRNA and protein in CD4 and CD8 T cells, leading to inhibition of T cell proliferation, differentiation, and response to immune checkpoint blockade (Giles et al., 2018). The combination of dexamethasone and radio/chemotherapy resulted in severe reductions in CD4 T cell counts in patients with newly diagnosed GBM (Grossman et al., 2011). These findings suggest that current treatment modalities fuel the effect of immunosuppressive niches on GBM progression, which might explain the failure of immunotherapy-based clinical trials (Pearson et al., 2020).

Moreover, targeting PVNs using bevacizumab to neutralize VEGF has been shown to enhance tumor invasiveness in patients and mouse models with GBM (de Groot et al., 2010). Given that VEGF contributes to tumor immunosuppression (Fukumura et al., 2018), targeting VEGF-mediated PVNs may enhance immunotherapy benefits for patients with GBM. Unfortunately, a clinical trial study revealed that anti-PD-1 using pembrolizumab alone or with bevacizumab was well tolerated but of limited benefit (NCT02337491) (Nayak et al., 2021).

Spatial Profiling Technologies for Understanding Brain Tumor Niches

Single-cell sequencing- and spatial omics-based technologies have recently been rapidly developed and intensively used to characterize the remarkable diversity of cellular/tissue identity and function at their native complexity level (Moffitt et al., 2022). These technologies offer an unprecedented opportunity and powerful tools for understanding the diversity and dynamics of GBM niche evolution and interaction. Omics approaches can yield molecular profiling of normal and cancer cells in the TME at genome-, epigenome-, transcriptome-, metabolome-, and proteome-wide scales when the spatial context of tissues/organs is preserved. Emerging methods have been mainly used, including spatial indexing transcriptomics, image-based spatial transcriptomics, and image-based spatial proteomics (Moffitt et al., 2022). The most recent study using spatial profiling technologies sought to characterize GBM by spatially resolved transcriptomics, metabolomics, and proteomics and provided the landscape of bidirectional GBM tumor–host interdependence (Ravi et al., 2022).

Undoubtedly, spatial profiling technologies will play a crucial role in the investigations of the brain TME and further deepen our understanding of tumor niche dynamics and complexity and hold great promise for the development of new and effective therapies for this devastating disease.

Conclusions

In this review, we describe the various tumor niches in GBM, which are anatomically and functionally distinct but interconnected with each other during tumor evolution. The cellular and molecular heterogeneity of the components within these niches demonstrates the complexity and dynamics of the GBM microenvironment. It is very likely that GBM treatment will require manipulating the dynamic niches rather than single molecular or single cell types. Of note, GSCs play a central role in the TME during GBM evolution by bilaterally communicating with PVNs, hypoxic niches, invasive niches, and immunosuppressive niches. Based on numerous preclinical studies, many clinical trials have been aimed at targeting the niche's components.

However, the data from completed and ongoing clinical trials suggest that GBM therapy faces many significant challenges, including deeply understanding the plasticity and heterogeneity of GSCs and non-GSCs, delineating molecular mechanisms of immunosuppression and treatment escape, and mapping tumor niche trajectories and functions. Thus, future studies should address these questions with the use of new technologies and sophisticated model systems, such as spatiotemporal multiomics, patient-derived organoids, and humanized GBM mouse models, which will inform the design of novel and effective therapies for the treatment of this devastating brain cancer.

Abbreviations Used

- 2ME2

2-methoxyestradiol

- ANG2

angiopoietin-2

- ARNT

oxygen-independent HIF-1β subunit

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- CAR

chimeric antigen receptor

- CHI3L1

chitinase-3-like 1

- CSF1R

colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor

- Cx43

gap junction protein connexin43

- DCs

dendritic cells

- EC

endothelial cell

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- FAKs

focal adhesion kinases

- FDA

Food and Drug Administration

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- Gal3

galectin-3

- Gal3BP

galectin-3 binding protein

- GBM

glioblastoma

- GdECs

GSC-derived endothelial-like cells

- GSCs

glioblastoma stem cells

- HIFs

hypoxia-inducible factors

- IDH

isocitrate dehydrogenase

- MDM

myeloid-derived macrophage

- MDSC

myeloid-derived suppressor cell

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- MVP

microvascular proliferation

- NK

natural killer

- NSC

neural stem cell

- OS

overall survival

- PDGF

platelet-derived growth factor

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PVN

perivascular niche

- RGD

Arg-Gly-Asp

- SVZ

subventricular zone

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor-β

- TILs

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

- TME

tumor microenvironment

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Authors' Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S. and B.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.S., M.D., and B.H.; writing—review and editing, R.S., M.D., H.Z., X.L., and B.H.; figure design and preparation, R.S., M.D., and B.H.; funding acquisition, B.H.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding Information

This work was supported by grants from the Scientific Program Fund from the UPMC Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh (to B.H.) and NIH grants 1R01CA259124 (to B.H.) and 1R21NS125218 (to B.H.).

References

- Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006;7(1):41–53; doi: 10.1038/nrn1824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aderetti DA, Hira VVV, Molenaar RJ, et al. The hypoxic peri-arteriolar glioma stem cell niche, an integrated concept of five types of niches in human glioblastoma. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2018;1869(2):346–354; doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akkari L, Bowman RL, Tessier J, et al. Dynamic changes in glioma macrophage populations after radiotherapy reveal CSF-1R inhibition as a strategy to overcome resistance. Sci Transl Med 2020;12(552); doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaw7843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allavena P, Anfray C, Ummarino A, et al. Therapeutic manipulation of tumor-associated macrophages: Facts and hopes from a clinical and translational perspective. Clin Cancer Res 2021;27(12):3291–3297; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An Z, Aksoy O, Zheng T, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor and EGFRvIII in glioblastoma: Signaling pathways and targeted therapies. Oncogene 2018;37(12):1561–1575; doi: 10.1038/s41388-017-0045-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arko L, Katsyv I, Park GE, et al. Experimental approaches for the treatment of malignant gliomas. Pharmacol Ther 2010;128(1):1–36; doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Wu Q, McLendon RE, et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature 2006a;444(7120):756–760; doi: 10.1038/nature05236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao S, Wu Q, Sathornsumetee S, et al. Stem cell-like glioma cells promote tumor angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res 2006b;66(16):7843–7848; doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bausart M, Preat V, Malfanti A. Immunotherapy for glioblastoma: The promise of combination strategies. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2022;41(1):35; doi: 10.1186/s13046-022-02251-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck S, Jin X, Sohn YW, et al. Telomerase activity-independent function of TERT allows glioma cells to attain cancer stem cell characteristics by inducing EGFR expression. Mol Cells 2011;31(1):9–15; doi: 10.1007/s10059-011-0008-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AP, Sells BE, Haque SJ, et al. Tumor heterogeneity in glioblastomas: From light microscopy to molecular pathology. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13(4); doi: 10.3390/cancers13040761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello L, Francolini M, Marthyn P, et al. Alpha(v)beta3 and alpha(v)beta5 integrin expression in glioma periphery. Neurosurgery 2001;49(2):380–389, discussion 390; doi: 10.1097/00006123-200108000-00022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello L, Lucini V, Giussani C, et al. IS20I, a specific alphavbeta3 integrin inhibitor, reduces glioma growth in vivo. Neurosurgery 2003;52(1):177–185, discussion 185–176; doi: 10.1097/00006123-200301000-00023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger G, Knelson EH, Jimenez-Macias JL, et al. STING activation promotes robust immune response and NK cell-mediated tumor regression in glioblastoma models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2022;119(28):e2111003119; doi: 10.1073/pnas.2111003119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berghoff AS, Kiesel B, Widhalm G, et al. Correlation of immune phenotype with IDH mutation in diffuse glioma. Neuro Oncol 2017;19(11):1460–1468; doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum R, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, et al. Ras inhibition in glioblastoma down-regulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha, causing glycolysis shutdown and cell death. Cancer Res 2005;65(3):999–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd NH, Tran AN, Bernstock JD, et al. Glioma stem cells and their roles within the hypoxic tumor microenvironment. Theranostics 2021;11(2):665–683; doi: 10.7150/thno.41692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, et al. The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 2013;155(2):462–477; doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks LJ, Parrinello S. Vascular regulation of glioma stem-like cells: A balancing act. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2017;47:8–15; doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown CE, Starr R, Aguilar B, et al. Stem-like tumor-initiating cells isolated from IL13Ralpha2 expressing gliomas are targeted and killed by IL13-zetakine-redirected T cells. Clin Cancer Res 2012;18(8):2199–2209; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruna A, Darken RS, Rojo F, et al. High TGFbeta-Smad activity confers poor prognosis in glioma patients and promotes cell proliferation depending on the methylation of the PDGF-B gene. Cancer Cell 2007;11(2):147–160; doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buerki RA, Chheda ZS, Okada H. Immunotherapy of primary brain tumors: Facts and hopes. Clin Cancer Res 2018;24(21):5198–5205; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butowski N, Colman H, De Groot JF, et al. Orally administered colony stimulating factor 1 receptor inhibitor PLX3397 in recurrent glioblastoma: An Ivy Foundation Early Phase Clinical Trials Consortium phase II study. Neuro Oncol 2016;18(4):557–564; doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nov245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese C, Poppleton H, Kocak M, et al. A perivascular niche for brain tumor stem cells. Cancer Cell 2007;11(1):69–82; doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.11.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantanhede IG, de Oliveira JRM. PDGF family expression in glioblastoma multiforme: Data compilation from Ivy Glioblastoma Atlas Project database. Sci Rep 2017;7(1):15271; doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15045-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Principles and mechanisms of vessel normalization for cancer and other angiogenic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2011;10(6):417–427; doi: 10.1038/nrd3455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho da Fonseca AC, Wang H, Fan H, et al. Increased expression of stress inducible protein 1 in glioma-associated microglia/macrophages. J Neuroimmunol 2014;274(1–2):71–77; doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.06.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae SS, Kamoun WS, Farrar CT, et al. Angiopoietin-2 interferes with anti-VEGFR2-induced vessel normalization and survival benefit in mice bearing gliomas. Clin Cancer Res 2010;16(14):3618–3627; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles N, Holland EC. The perivascular niche microenvironment in brain tumor progression. Cell Cycle 2010;9(15):3012–3021; doi: 10.4161/cc.9.15.12710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A, Jiang Y, Li Z, et al. Chitinase-3-like 1 protein complexes modulate macrophage-mediated immune suppression in glioblastoma. J Clin Invest 2021;131(16); doi: 10.1172/JCI147552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Feng X, Herting CJ, et al. Cellular and molecular identity of tumor-associated macrophages in glioblastoma. Cancer Res 2017;77(9):2266–2278; doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-2310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnaiyan P, Won M, Wen PY, et al. A randomized phase II study of everolimus in combination with chemoradiation in newly diagnosed glioblastoma: Results of NRG Oncology RTOG 0913. Neuro Oncol 2018;20(5):666–673; doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nox209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinot OL, Wick W, Mason W, et al. Bevacizumab plus radiotherapy-temozolomide for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2014;370(8):709–722; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos PF, Gjolberg TT, Kruger S, et al. Targeting the Notch signaling pathway in chronic inflammatory diseases. Front Immunol 2021;12:668207; doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.668207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close HJ, Stead LF, Nsengimana J, et al. Expression profiling of single cells and patient cohorts identifies multiple immunosuppressive pathways and an altered NK cell phenotype in glioblastoma. Clin Exp Immunol 2020;200(1):33–44; doi: 10.1111/cei.13403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell N, Larion M, Giles AJ, et al. Hypoxia in the glioblastoma microenvironment: Shaping the phenotype of cancer stem-like cells. Neuro Oncol 2017;19(7):887–896; doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coniglio SJ, Eugenin E, Dobrenis K, et al. Microglial stimulation of glioblastoma invasion involves epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF-1R) signaling. Mol Med 2012;18:519–527; doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier CP, Ayyadhury S, Le PU, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals that glioblastoma recapitulates a normal neurodevelopmental hierarchy. Nat Commun 2020;11(1):3406; doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17186-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowman SJ, Koh MY. Revisiting the HIF switch in the tumor and its immune microenvironment. Trends Cancer 2022;8(1):28–42; doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2021.10.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruickshanks N, Zhang Y, Yuan F, et al. Role and therapeutic targeting of the HGF/MET pathway in glioblastoma. Cancers (Basel) 2017;9(7); doi: 10.3390/cancers9070087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Groot JF, Fuller G, Kumar AJ, et al. Tumor invasion after treatment of glioblastoma with bevacizumab: Radiographic and pathologic correlation in humans and mice. Neuro Oncol 2010;12(3):233–242; doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depner C, Zum Buttel H, Bogurcu N, et al. EphrinB2 repression through ZEB2 mediates tumour invasion and anti-angiogenic resistance. Nat Commun 2016;7:12329; doi: 10.1038/ncomms12329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRoo EP, Wrobleski SK, Shea EM, et al. The role of galectin-3 and galectin-3-binding protein in venous thrombosis. Blood 2015;125(11):1813–1821; doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-569939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- di Tomaso E, London N, Fuja D, et al. PDGF-C induces maturation of blood vessels in a model of glioblastoma and attenuates the response to anti-VEGF treatment. PLoS One 2009;4(4):e5123; doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diksin M, Smith SJ, Rahman R. The molecular and phenotypic basis of the glioma invasive perivascular niche. Int J Mol Sci 2017;18(11); doi: 10.3390/ijms18112342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du R, Lu KV, Petritsch C, et al. HIF1alpha induces the recruitment of bone marrow-derived vascular modulatory cells to regulate tumor angiogenesis and invasion. Cancer Cell 2008a;13(3):206–220; doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du R, Petritsch C, Lu K, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 regulates vascular patterning and growth affecting tumor cell survival and invasion in GBM. Neuro Oncol 2008b;10(3):254–264; doi: 10.1215/15228517-2008-001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn IF, Heese O, Black PM. Growth factors in glioma angiogenesis: FGFs, PDGF, EGF, and TGFs. J Neurooncol 2000;50(1–2):121–137; doi: 10.1023/a:1006436624862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LA, Woolard K, Son MJ, et al. Effect of brain- and tumor-derived connective tissue growth factor on glioma invasion. J Natl Cancer Inst 2011;103(15):1162–1178; doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellert-Miklaszewska A, Poleszak K, Pasierbinska M, et al. Integrin signaling in glioma pathogenesis: From biology to therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21(3); doi: 10.3390/ijms21030888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erber R, Eichelsbacher U, Powajbo V, et al. EphB4 controls blood vascular morphogenesis during postnatal angiogenesis. EMBO J 2006;25(3):628–641; doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezhilarasan R, Jadhav U, Mohanam I, et al. The hemopexin domain of MMP-9 inhibits angiogenesis and retards the growth of intracranial glioblastoma xenograft in nude mice. Int J Cancer 2009;124(2):306–315; doi: 10.1002/ijc.23951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidoamore A, Cristiano L, Antonosante A, et al. Glioblastoma stem cells microenvironment: The paracrine roles of the niche in drug and radioresistance. Stem Cells Int 2016;2016:6809105; doi: 10.1155/2016/6809105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filer A, Bik M, Parsonage GN, et al. Galectin 3 induces a distinctive pattern of cytokine and chemokine production in rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts via selective signaling pathways. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60(6):1604–1614; doi: 10.1002/art.24574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, et al. Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: Opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2018;15(5):325–340; doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fusetti F, Pijning T, Kalk KH, et al. Crystal structure and carbohydrate-binding properties of the human cartilage glycoprotein-39. J Biol Chem 2003;278(39):37753–37760; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303137200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabrusiewicz K, Rodriguez B, Wei J, et al. Glioblastoma-infiltrated innate immune cells resemble M0 macrophage phenotype. JCI Insight 2016;1(2); doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.85841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangoso E, Southgate B, Bradley L, et al. Glioblastomas acquire myeloid-affiliated transcriptional programs via epigenetic immunoediting to elicit immune evasion. Cell 2021;184(9):2454.e26–2470.e26; doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gariboldi MB, Ravizza R, Monti E. The IGFR1 inhibitor NVP-AEW541 disrupts a pro-survival and pro-angiogenic IGF-STAT3-HIF1 pathway in human glioblastoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol 2010;80(4):455–462; doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MR, Dignam JJ, Armstrong TS, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab for newly diagnosed glioblastoma. N Engl J Med 2014;370(8):699–708; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles AJ, Hutchinson MND, Sonnemann HM, et al. Dexamethasone-induced immunosuppression: Mechanisms and implications for immunotherapy. J Immunother Cancer 2018;6(1):51; doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0371-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman SA, Ye X, Lesser G, et al. Immunosuppression in patients with high-grade gliomas treated with radiation and temozolomide. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17(16):5473–5480; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin GJ, Brew BJ. Microglia, macrophages, perivascular macrophages, and pericytes: A review of function and identification. J Leukoc Biol 2004;75(3):388–397; doi: 10.1189/jlb.0303114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambardzumyan D, Bergers G. Glioblastoma: Defining tumor niches. Trends Cancer 2015;1(4):252–265; doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2015.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambardzumyan D, Gutmann DH, Kettenmann H. The role of microglia and macrophages in glioma maintenance and progression. Nat Neurosci 2016;19(1):20–27; doi: 10.1038/nn.4185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermanson M, Funa K, Hartman M, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor and its receptors in human glioma tissue: Expression of messenger RNA and protein suggests the presence of autocrine and paracrine loops. Cancer Res 1992;52(11):3213–3219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermansson M, Nister M, Betsholtz C, et al. Endothelial cell hyperplasia in human glioblastoma: Coexpression of mRNA for platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) B chain and PDGF receptor suggests autocrine growth stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1988;85(20):7748–7752; doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himes BT, Geiger PA, Ayasoufi K, et al. Immunosuppression in glioblastoma: Current understanding and therapeutic implications. Front Oncol 2021;11:770561; doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.770561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hira VVV, Aderetti DA, van Noorden CJF. Glioma stem cell niches in human glioblastoma are periarteriolar. J Histochem Cytochem 2018;66(5):349–358; doi: 10.1369/0022155417752676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Wang Q, Wang YA, et al. Epigenetic activation of WNT5A drives glioblastoma stem cell differentiation and invasive growth. Cell 2016;167(5):1281.e18–1295.e18; doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isner JM, Asahara T. Angiogenesis and vasculogenesis as therapeutic strategies for postnatal neovascularization. J Clin Invest 1999;103(9):1231–1236; doi: 10.1172/JCI6889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SH, Cho HT, Devi S, et al. Antitumor effect of 2-methoxyestradiol in a rat orthotopic brain tumor model. Cancer Res 2006;66(24):11991–11997; doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karachi A, Dastmalchi F, Mitchell DA, et al. Temozolomide for immunomodulation in the treatment of glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol 2018;20(12):1566–1572; doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noy072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur B, Khwaja FW, Severson EA, et al. Hypoxia and the hypoxia-inducible-factor pathway in glioma growth and angiogenesis. Neuro Oncol 2005;7(2):134–153; doi: 10.1215/S1152851704001115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AR, Choi SJ, Park J, et al. Spatial immune heterogeneity of hypoxia-induced exhausted features in high-grade glioma. Oncoimmunology 2022;11(1):2026019; doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2022.2026019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M, Ladomersky E, Mozny A, et al. Glioblastoma as an age-related neurological disorder in adults. Neurooncol Adv 2021;3(1):vdab125; doi: 10.1093/noajnl/vdab125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]