Abstract

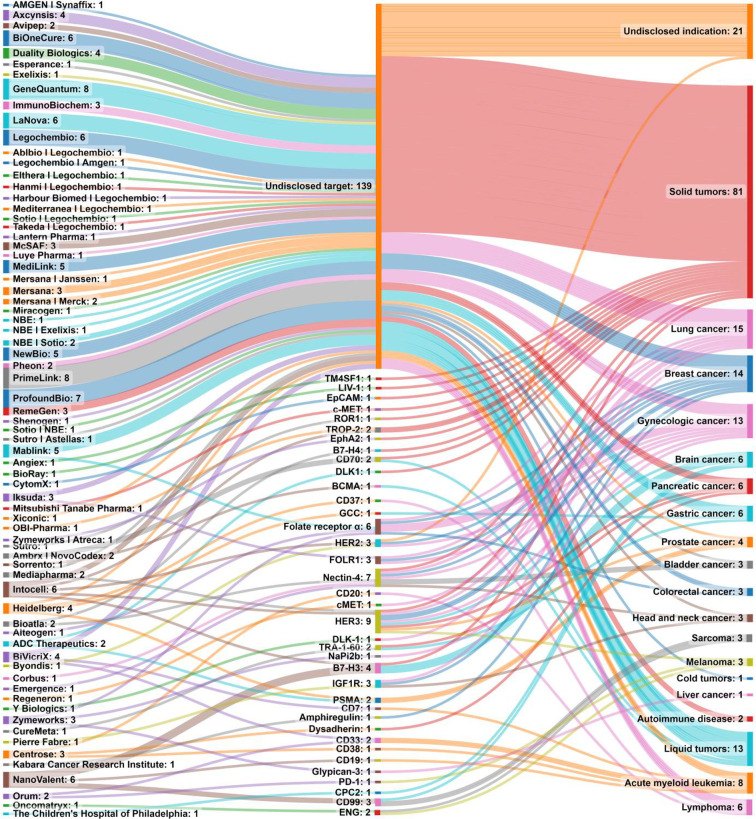

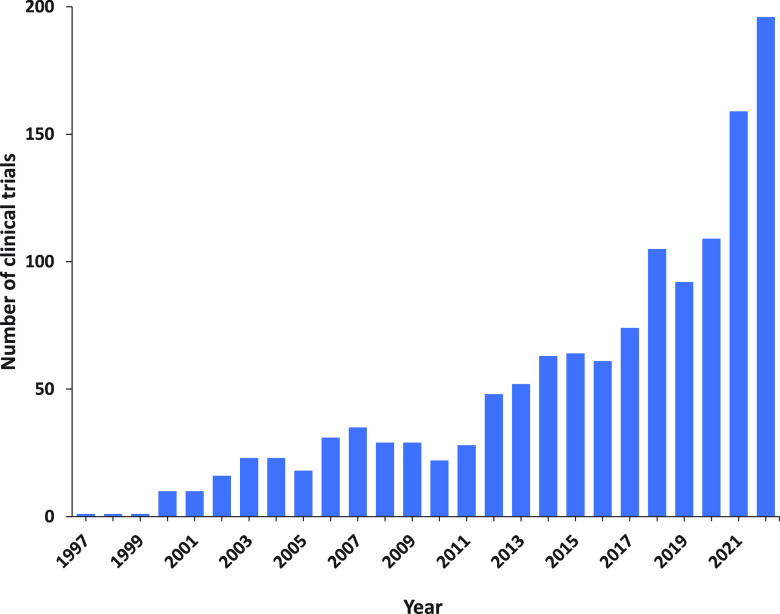

Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) are targeted immunoconjugate constructs that integrate the potency of cytotoxic drugs with the selectivity of monoclonal antibodies, minimizing damage to healthy cells and reducing systemic toxicity. Their design allows for higher doses of the cytotoxic drug to be administered, potentially increasing efficacy. They are currently among the most promising drug classes in oncology, with efforts to expand their application for nononcological indications and in combination therapies. Here we provide a detailed overview of the recent advances in ADC research and consider future directions and challenges in promoting this promising platform to widespread therapeutic use. We examine data from the CAS Content Collection, the largest human-curated collection of published scientific information, and analyze the publication landscape of recent research to reveal the exploration trends in published documents and to provide insights into the scientific advances in the area. We also discuss the evolution of the key concepts in the field, the major technologies, and their development pipelines with company research focuses, disease targets, development stages, and publication and investment trends. A comprehensive concept map has been created based on the documents in the CAS Content Collection. We hope that this report can serve as a useful resource for understanding the current state of knowledge in the field of ADCs and the remaining challenges to fulfill their potential.

1. Introduction

Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) are currently among the most promising drug classes in oncology because of their ability to deliver cytotoxic agents to specific tumor sites, combining the selectivity of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and the efficacy of chemotherapeutic drugs.1−4 Cancer is a major global health threat, causing millions of fatalities yearly.5,6 Chemotherapies based on cytotoxic drugs have been the main strategy for treating of a wide assortment of cancers for decades.7,8 Cytotoxic drugs include a large variety of compounds such as alkylating agents, antimetabolites, antitumor antibiotics, topoisomerase and mitotic inhibitors, and corticosteroids among many others.9−14 Most of these antitumor drugs, however, exhibit low therapeutic index and cause severe side effects due to nonspecific drug exposure to off-target tissues.15 To address these challenges, intense research has been carried out, aimed at developing novel cancer therapeutics with better targeting ability and less harmful side effects.

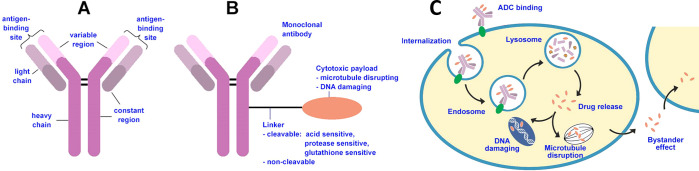

ADCs are targeted immunoconjugate constructs that integrate the potency of cytotoxic drugs with the selectivity of monoclonal antibodies (Figure 1), minimizing damage to healthy cells and reducing systemic toxicity. The structure of an ADC consists of three main components: a monoclonal antibody, a cytotoxic drug payload, and a linker molecule.16−19 The monoclonal antibody is engineered to bind specifically to a target antigen that is overexpressed on cancer cells. This allows the ADC to selectively target cancer cells while sparing normal cells. The cytotoxic drug payload is a potent chemotherapeutic agent that is highly effective in killing cancer cells. The linker molecule attaches the cytotoxic drug to the antibody, and its stability is crucial in controlling the release of the drug within the target cell.16,20−22 Once the ADC binds to the cancer cell surface, it is internalized through receptor-mediated endocytosis. Within the cancer cell, the linker molecule is designed to release the cytotoxic drug payload either by enzymatic cleavage or through chemical degradation. Once released, the cytotoxic drug exerts its therapeutic effect by disrupting key cellular processes and inducing cancer cell death.

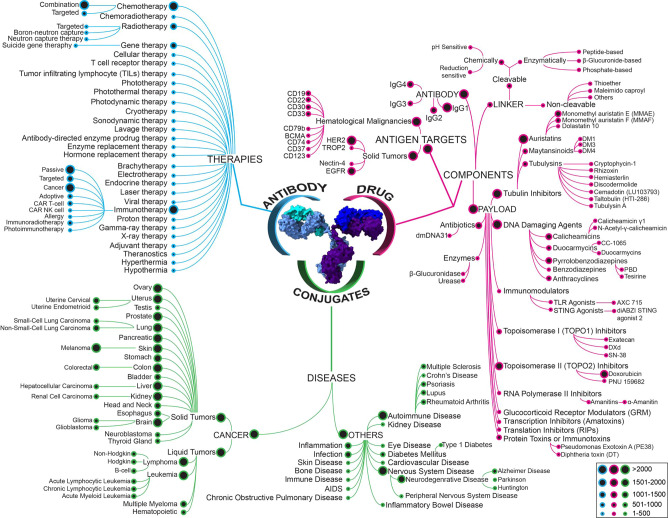

Figure 1.

Structure and mechanism of action of ADCs. (A) Scheme of antibody structure including heavy chains, light chains, constant region, variable region, and antigen binding site. (B) Antitumor ADCs combine three key elements: a monoclonal antibody moiety that binds to an antigen preferentially expressed on the tumor cell surface, thereby ensuring specific binding to tumor cells; a covalent linker that warrants that the payload drug is not released in blood ahead of time, but is released within the tumor cell; and a cytotoxic payload that causes tumor cell apoptosis through targeting of key components such as DNA, microtubules. (C) ADC mechanism of action includes key sequential steps: binding to cell surface antigen; internalization of the ADC–antigen complex through endocytosis; lysosomal degradation; release of the cytotoxic payload within the cytoplasm; and interaction with target cell components. A fraction of the payload may be released in the extracellular environment and taken up by neighboring cells, known as the bystander effect.

ADCs offer several advantages over conventional chemotherapy. By selective targeting of cancer cells, ADCs reduce damage to healthy tissues and minimize side effects. This allows for higher doses of the cytotoxic drug to be delivered to the tumor, potentially increasing efficacy. Additionally, the antibody component of ADCs can elicit an immune response against the cancer cells, further enhancing their antitumor activity. Therefore, ADCs have become a major approach in the research and development of antitumor drugs.16,21,22

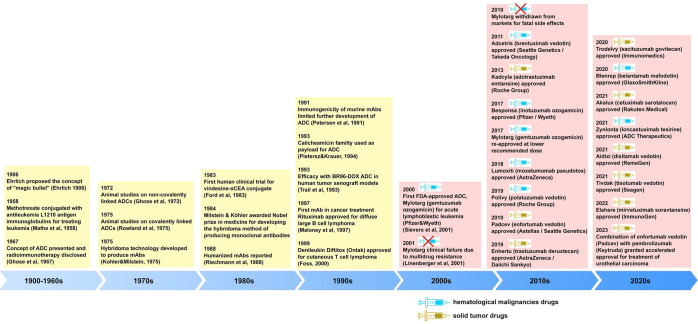

The German scientist Paul Ehrlich is credited with coining the term chemotherapy to indicate the use of chemical compounds to treat disease.23 Following his experience with antibodies, Ehrlich also proposed the concept of a “magic bullet” (Figure 2) that would bring about a selective targeting of pathogens without injuring the rest of the organism, one of the most notable notions of modern medicine.24 Ehrlich’s idea of targeted therapy was first materialized almost 50 years later, with methotrexate linked to an antibody targeting leukemia cells.25 The innovative development of hybridoma technology to produce mouse mAbs greatly advanced the field.26 It took nearly eight decades until Ehrlich’s visionary concept was advanced to achieve the first human trial of ADC therapy using an anticarcinoembryonic antigen antibody-vindesine conjugate.27 Subsequent advances in technologies for the ADC constituent building blocks–the antibody, the linker, and the payload–have resulted in the development of greater number of ADCs with enhanced potency, improved pharmacokinetics, reduced immunogenicity and overall toxicity, and upgraded specificity for cancer cells.28 Early ADC prototypes were created but they suffered from issues such as limited stability and inadequate target specificity. In the 1990s preclinical studies demonstrated the potential of ADCs in improving the therapeutic index of cytotoxic drugs by targeting specific antigens expressed on cancer cells.29−31 However, early clinical trials encountered challenges including toxicity and insufficient efficacy. In the late 1990s to early 2000s advances in antibody engineering and linker technologies contribute to the development of more stable and effective ADCs.32−35 Several ADC candidates have entered clinical trials, showing promising results in terms of efficacy and safety.

Figure 2.

Timeline of key events and discoveries in the antibody–drug conjugate research and development.21,24−27,29−34,36−80

The early, first-generation, ADCs used clinically approved drugs with well-documented mechanisms of action, including the antimetabolites methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil, the DNA cross-linker mitomycin and the antimicrotubule agent vinblastine.30 First-generation ADC, however, showed insufficient drug efficacy, linker instability, targeted antigens expressed in both normal and cancerous cells, and triggered undesired immune responses.29 Further developments, including higher drug efficacy and thoroughly selected targets, eventually led to the first ADC, Mylotarg (gemtuzumab ozogamicin), to get approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2000 for the treatment of CD33-positive acute myelogenous leukemia.33,34 Regardless of the hopeful clinical results, Mylotarg was withdrawn from the market because it did not exhibit progress in overall survival. The second ADC to be developed, Adcetris (brentuximab vedotin), received approval from the US FDA in 2011 for the treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma and anaplastic large-cell lymphoma.43,44 The next ADC, Kadcyla (trastuzumab emtansine), used a construct combining the humanized antibody trastuzumab with a powerful microtubule inhibitor cytotoxic drug via a highly stable linker. It was approved for the treatment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer in 2013.45,46

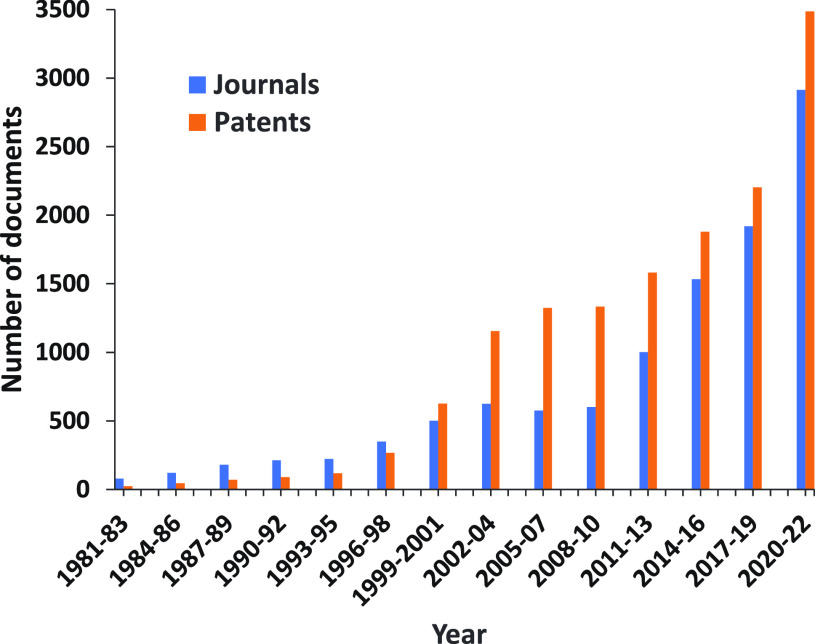

Recent advancements have resulted in a new generation of ADCs with better chemistry, manufacturing, and control (CMC) properties, including linkers with optimized stability and powerful cytotoxic agents. Currently, there are 15 approved ADCs, which have received market endorsement worldwide, with over 150 candidates being investigated in various stages of clinical trials at present. Out of these, ∼12% are in the late-phase (Phase III/IV) owing to rapid advancements in technology required for generating ADCs. Thus, ADCs as an anticancer treatment strategy is leading a new era of targeted cancer defeat. Additionally, ADCs are being increasingly applied in combination with other agents. The growing diversification of target antigens as well as bioactive cytotoxic payloads is rapidly extending the range and scope of tumors targeted by ADCs. However, toxicity continues to remain a key issue in the development of these agents, and a better understanding and management of ADC-related toxicities will be essential for further optimization. Although numerous challenges remain, recent clinical accomplishments have produced intense interest in this therapeutic class reflected in a rapidly growing number of publications (Figure 3). The development of ADCs continues to be a particularly active area of research and development, with ongoing efforts to optimize the design of antibodies, linkers, and cytotoxic drug payloads. The goal is to improve the efficacy and safety profile of ADCs and apply them to a wider range of cancers and to other diseases.

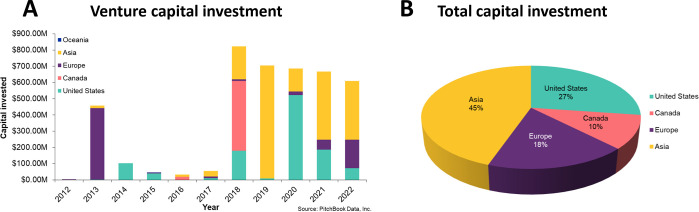

Figure 3.

Yearly growth of the number of documents (journal articles and patents) in the CAS Content Collection related to antibody–drug conjugate research and development.

This report provides a detailed overview of the recent advances in antibody–drug conjugate research and considers future directions and challenges in advancing this promising platform to widespread therapeutic use. We examine data from the CAS Content Collection,81 the largest human-curated collection of published scientific information, and analyzed the ADC publication landscape of recent research (2000 onward) to uncover the trends in published documents (both journals as well as patents) and to provide insights into scientific advances in the area. We also discuss the evolution of key concepts in the field as well as the major technologies and the development pipelines of ADCs with a particular focus/emphasis on company research, disease targets, and development stages. We hope this report can serve as a useful resource for understanding the current state of the field of ADCs and the remaining challenges to fulfill and achieve their full potential.

2. ADC Basics

2.1. Selection/Optimization of Antibodies

Antibodies are an essential building block of ADCs (Figure 1) that possess characteristic requirements. It should have a high affinity and avidity for the target antigen but no or insignificant binding to off-target sites and it is important to have selective binding to the target antigen leading to the accumulation and retention of ADCs at the target site.82−84 In addition, the antibody should have low immunogenicity, low cross-reactivity, optimum-linker binding, and a long half-life.85,86 It is interesting to note that the antibody component of many ADCs retains its activity profile and can therefore interfere with target cell function, alter downstream signaling, and/or cause immune effector cells to elicit payload-independent antitumor immunity, thereby acting beyond mere payload carrier. For example, the Fab region of the antibody in ADCs can disrupt target function by blocking ligand binding, interfering with dimerization and/or endocytosis, and target protein degradation.84,87 Likewise, the Fc region of the antibody can induce antibody-dependent cell cytotoxicity (ADCC). Most ADCs such as Kadcyla (T-DM1), Enhertu (T-DXd), Polivy, Padcev, Trodelvy, just to mention a few, rely upon the ADCC-competent IgG1 backbone.59,61,65,85,88 The Fc region is also responsible for complement-dependent cytotoxicity and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis.

A significant and long-recognized challenge in the field is the heterogeneous distribution of the antibodies when administered systemically.89 Antibody internalization and clearance obstruct uptake in solid tumors, limited by tumor vascular permeability and diffusion.90 Mathematical analysis of antibody distribution through tumors applying simple scaling relationships can help understanding the tumor physiology and antibody tumor penetration.90,91 Fundamental understanding of the mechanisms and time scales of antibody transport and clearance are essential for the prediction of the distance an antibody may permeate through tumor tissue, with the balance between these processes controlling the antibody penetration into a tumor and therefore its optimal efficacy.91 Thus, for solid tumors, optimal binding affinity has been suggested to depend on the level of target expression.91

Initially, first-generation ADCs used murine antibodies, but they elicited a robust immune response with some patients producing antihuman antibodies, leading to the generation of second-generation chimeric antibodies. These mouse/human chimeric antibodies contain the variable regions of mouse light- and heavy-chains linked to human constant regions. Recent developments in the field have moved toward fully humanized mAbs which do not produce immunogenic responses.88,92 Many innovative strategies are being used to maximize the efficacy of ADCs including the use of biparatopic antibodies. These antibodies target two different epitopes of the same target antigen and can help cluster the antigenic receptors, leading to the rapid internalization of ADCs.

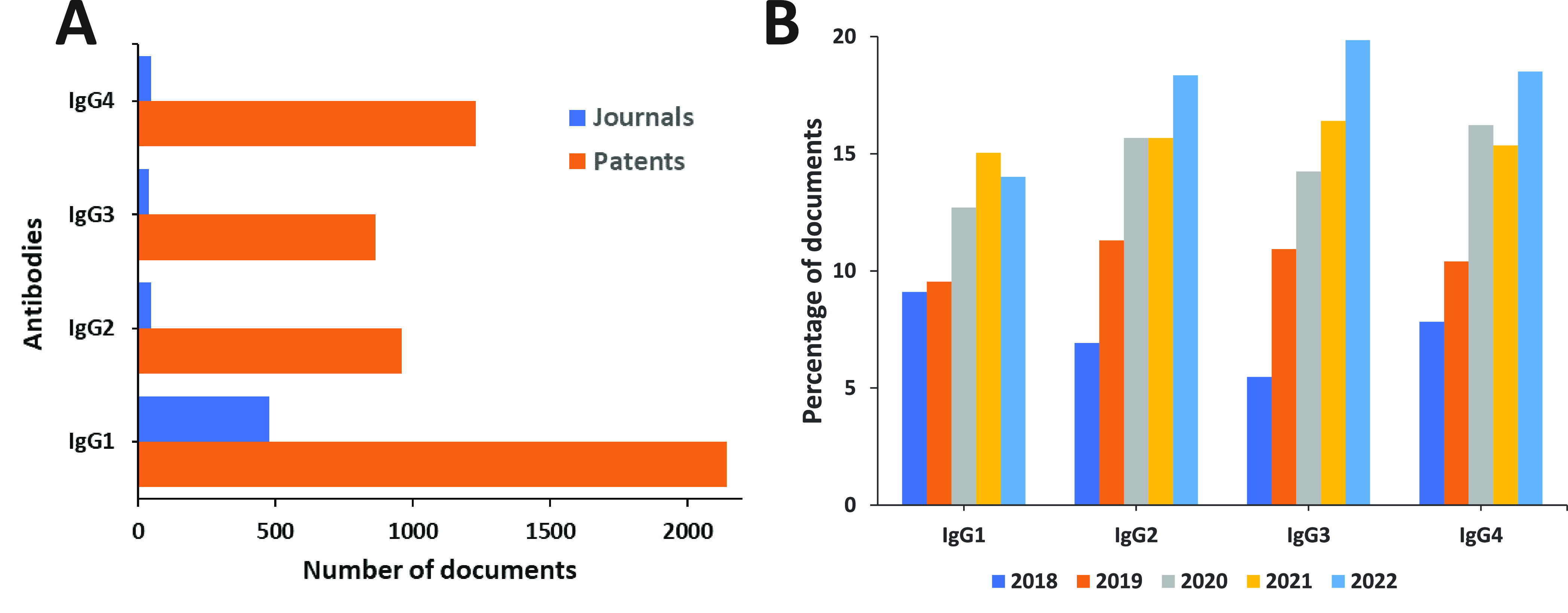

For designing present-day ADCs, immunoglobulin G (IgG) is the most widely used antibody isotype. ADCs must have similar pharmacokinetic properties to those of normal human IgGs. Human IgG comprises four subclasses: IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4, which differ in their constant and hinge regions. Despite being the most immunogenic, use of IgG3 is avoided in ADC design due to its short serum circulating half-life (∼7 days) when compared to other subclasses (∼21 days).88,93 Though IgG1, IgG2, and IgG4 have suitable serum half-lives, IgG2 is rarely used owing to its tendency to dimerize and aggregate in vivo.94 Most ADCs are developed on IgG1 platforms because of improved solubility, greater complement-fixation, low nonspecific immunity, and better immune effector cell receptor (FcγR)-binding efficiencies of IgG1, which can play a crucial role in anticancer activity of ADCs.3,84 Though IgG4 can also induce antibody-dependent phagocytosis (ADCP), its dynamic nature due to Fab-arm exchange contributes to reduced efficacy. Despite this, a few ADCs, such as Gemtuzumab ozogamicin and Inotuzumab ozogamicin, use IgG4 as the platform to target CD33 and CD22, respectively.95−97 Gemtuzumab ozogamicin contains an IgG4 core-hinge mutation that blocks Fab-arm exchange.98

″Biparatopic” or “bispecific antibodies” are antibodies designed to simultaneously bind to two different epitopes (binding sites) on the same target antigen or two different antigens.99,100 This dual binding capacity can offer several advantages in terms of therapeutic applications. Thus, having two antigen-binding sites allows them to target either two distinct epitopes on the same antigen or two different antigens altogether. Their advantages include (i) enhanced targeting–bispecific antibodies can engage two binding sites on the same antigen, potentially increasing binding affinity and specificity; (ii) versatility–they can target multiple antigens simultaneously, which is particularly valuable in cancer therapy or immunological diseases; (iii) cross-linking–in the context of cancer therapy, bispecific antibodies can cross-link cancer cells and immune cells, such as T cells, leading to targeted cell killing.100

Antibodies with masked binding domains have been engineered to have one or more of their antigen-binding sites temporarily inactivated or “masked”.101,102 These antibodies can be designed to change their binding properties under specific conditions. Their applications include conditional activation, for instance, an antibody may only become active when exposed to specific environmental factors or cellular cues; reduced off-target effects—in some cases, masking can be used to prevent antibody binding to nontarget tissues or cells until it reaches the desired site. CytomX’s Probody technology is one example where the binding domains of antibodies are masked by a peptide, which is selectively cleaved by proteases present at the tumor site.103 This allows for the activation of the antibody’s binding and therapeutic functions specifically within the tumor microenvironment.

Both biparatopic/bispecific antibodies and antibodies with masked binding domains are innovative strategies in antibody engineering, offering greater control and versatility in targeting diseases while minimizing off-target effects. These approaches continue to advance in the field of immunotherapy and targeted therapies with potential applications in cancer, autoimmune diseases, and other medical conditions.

The antibodies used in ADC design are large compared to the actual cytotoxic payload, which implies that much of the actual formulation is being utilized to deliver the antigen to the target rather than to execute its pharmacological activity. The large size of the antibody (∼150 kDa) can also cause issues with target penetration in solid tumors. The targeting capacity of antibodies is achieved through its small variable loop structures (VH) present at the terminal portion of Fab fragments; therefore, fragments of native antibodies can be used to develop smaller binding motifs such as F(ab)2, Fab′, Fab, and Fv fragments. In addition, engineered scaffolds, such as single-chain variable fragments (scFv-Fc), single domain antibodies (sdAbs), and diabodies, are being explored. Furthermore, humanized fragments of unusual IgGs, such as heavy chain variable domain(VHH) and heavy chain variable domain-based antibody (VNAR) fragments from camelids and shark antibodies, respectively known as nanobodies, are being studied.104 Owing to their small size, ease of production, manipulation, conjugation, high solubility, stability, and delayed serum clearance, these antibody fragment conjugates or FDCs have various advantages compared to their antibody precursors.105

For example, Fan et al. developed an epidermal growth factor (EGFR)-targeting nanobody-drug conjugate that displays potent anticancer activity in solid tumor models.104 In recent years, ASN004, an scFv-Fc ADC, has been developed that targets 5T4 oncofetal antigens expressed on a wide range of malignant tumors. It is designed by conjugating a novel scFv-Fc antibody with an Auristatin F hydroxypropylamide (AF-HPA) payload using Dohtlexin drug-linker technology. The developed ADC has a high drug-antigen ratio (DAR) of approximately 10–15 and has shown tumor repression in preclinical models.106 ANT-045 and ANT-043 are other scFv-Fc conjugated ADCs being developed by Antikor Biopharma that have shown successful results against solid tumors. While ANT-043 has tumor ablation effects in gastric, breast, and cancer xenograft models, ANT-045 has high stability, excellent in vitro cell-kill potency, and is successful in in vivo tumor cures.107

With the advancement in molecular biology techniques, site-specific antibody conjugation is being introduced into ADC development to increase the therapeutic efficacy. Antibodies can be engineered using genetic engineering, chemoenzymatic modifications, or metabolic labeling through their Fab or Fc region to introduce specific reaction sites for ease of conjugation. A few modifications include introducing natural amino acids such as cysteine (Cys) or glutamine (Gln).108−110 Apart from natural amino acids, unnatural amino acids (UAA) (also referred to as noncanonical amino acids) containing orthogonal side-chain functional groups are also introduced at different positions in the antibody for generating sites for stable conjugation. For example, tubulin inhibitor payload AS269 is conjugated to a HER2- targeted mAb incorporated with a UAA, pAF. The resulting anti-HER2 ADC (ARX788) has a DAR of 1.9 and exhibits a high serum stability and half-life. ARX788 showed strong antitumor activity in mice and is currently undergoing Phase III clinical trials.111,112 Recently, other ligands such as short peptide tags, modified glycans, and small molecule-based affinity ligands are also used to generate conjugation sites for antibody payloads.109,113,114 Some ADCs in preclinical/clinical development have attenuated effector functional activity, with the intention for reducing off-target off-tumor toxicity.115−117

Similar to ADCs, peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs) consist of a peptide two-five amino acids in length bound to the cytotoxic payload via a linker. A key difference between ADCs and PDCs is the substantially smaller size of the peptide component (2–20 kDa) of PDCs than the antibody component (∼150 kDa) of ADCs (5–25 amino acids vs ∼1000 amino acids in peptides and antibodies, respectively)118,119 This allows for better absorption and uptake than conventional ADCs, which is especially important for drugs that need to cross the BBB.118,119 ADCs and PDCs show a great degree of overlap in terms of linker chemistry and types of cytotoxic payloads. A variety of peptides have been utilized in PDCs, including bicyclic toxin peptides and dendritic peptides.119 Bicyclic peptides are small, constrained peptides, many of which have high affinity for target antigens. An example of a PDC is BT8009, which consists of a bicyclic peptide linked to MMAE. BT8009 binds cell adhesion molecule, nectin-4 with high affinity (∼3 nM) and specificity and has shown promise in NSCLC and pancreatic ductal xenograft models.120 Currently, several PDCs are in clinical trials or being actively explored.119

2.2. Linkers for Use in Antibody–Drug Conjugates

Linkers connect the active molecule in an ADC to the antibody that determines the target for the drug. To be effective, a linker should be stable in plasma.121 It should not alter the behavior of either the drug or the antibody to which it is attached. The linker should be sufficiently hydrophilic to moderate or mitigate the solubility effects of warheads, which, in most cases, are lipophilic. The linkers should not aggregate; since aggregation is likely to impair the activity of the antibody and may reduce the stability of the ADC. Finally, the linker should release the drug completely and selectively under appropriate conditions. The choice of linker will be determined by the functionality present on the drug and the antibody.

2.2.1. Linker Types

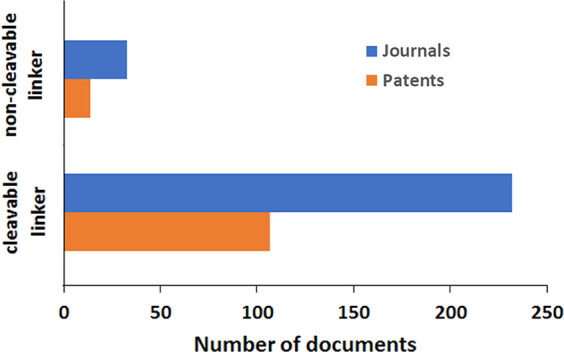

Linkers can be divided into two major classes: cleavable and noncleavable. Cleavable linkers allow the drug to be separated from the antibody without proteolytic cleavage of the antibody, while noncleavable linkers require proteolysis of the antibody for the drug to diffuse to its site of action.

2.2.1.1. Cleavable Linkers

Cleavable linkers allow the drug attached to an antibody to be freed from the ADC without destroying the antibody.17 Most commonly, cleavable linkers can be severed by acid, reducing agents, or enzymes.

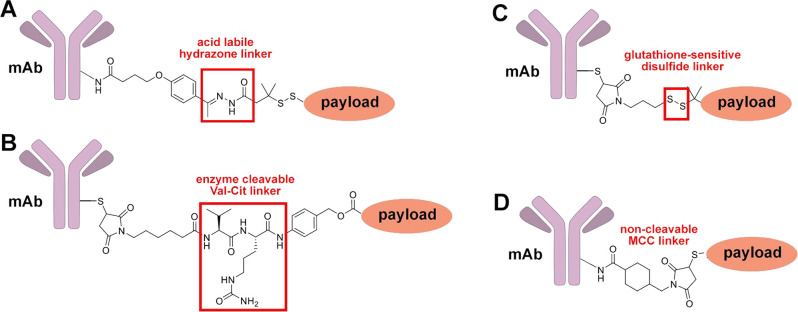

Acid-sensitive linkers are chosen because the microenvironment of tumors is often acidic and hypoxic;122 with parenteral administration ensuring that the drug is released selectively only in the tumor. Acid-cleavable linkers are most commonly hydrazones; for example, a hydrazone is used in the linker for the first USFDA-approved ADC Mylotarg.123 One disadvantage of acid-sensitive linkers is premature or nonselective release; Mylotarg was withdrawn in part because of nonselective toxicity (which was mitigated by changes in ADC dosing).124

Reductive linkers allow the release of the drug under reducing conditions; the hypoxic environment of tumors makes release of the drug at the tumor site more likely than elsewhere. Reductive linkers have most commonly been disulfides; disulfides can be cleaved either by reduction of the sulfur–sulfur bond or by exchange of thiols (such as glutathione, present in high concentrations in cancer cells) with disulfides to release a thiol (either the antibody or the drug).121 Cysteines or other thiols comprise the linker, but when the disulfide is attached to unhindered carbon atoms, nonselective cleavage of the disulfide is more likely. This can be mitigated significantly by two α-methyl groups on one of the carbons at the disulfide.125,126

Finally, as the name suggests, enzyme-cleavable linkers incorporate linkages that are selectively cleaved by enzymes. Enzyme-cleavable linkers most commonly use amides as the linking moieties because of the prevalence of enzymes in organisms that process and cleave amide bonds in proteins. Amides are thermally and hydrolytically stable, reducing the likelihood of premature or nonselective drug cleavage. The availability of a wide variety of enzymes and enzyme targets allows linkers to be tuned to avoid hydrolysis by enzymes in normal cells and to facilitate hydrolysis in tumor cells. Initially, di- and tripeptide linkers were used; one of the most common linkers contain the valine-citrulline (Val-Cit) linkage, a target for cathepsin B which is overexpressed in some tumor cells.127 Phenylalaninylvaline, valinylalanine, and tetrapeptide linkers have been deployed as well.128 The valine-citrulline linker is used in the approved ADC Adcetris, while the terminated clinical candidate T-Rova uses a valine-alanine linker.129 While amides are the most common in enzyme-cleavable linkers, other motifs have also been used. For example, substituted ortho-hydroxybenzyl β-glucuronides17 and β-galactosides121 are susceptible to hydrolysis by β-glucuronidase and β-galactosidase, respectively. Alternatively, substitution of the hydroxybenzyl phosphate-containing linkers yields linkers susceptible to hydrolysis by phosphatases. Cleavage of the acetal or phosphate linkage generates an ortho-hydroxybenzyl group, which subsequently undergoes dealkylative cleavage via an ortho-quinone methide to split the linker. The protected ortho-quinone methide linker is termed a self-immolative linker;130 while it is stable under physiological conditions, rapid cleavage occurs when the hydroxy group is unveiled. The self-immolative linker can be altered to incorporate a variety of groups sensitive to various enzymes, allowing linker cleavage to be tailored to the necessary selectivity.

2.2.1.2. Noncleavable Linkers

Noncleavable linkers are designed to remain intact until the antibody is proteolyzed in lysosomes after internalization. One example of a noncleavable linker is the maleimido thioether linker in Kadcyla;88,131 while retro-Michael reaction of the β-thioether amide is possible, the modes of cleavage common under physiological conditions are limited. Since conditional cleavage of ADC containing noncleavable linkers is rare to nonexistent, premature release of the drug moiety should be limited to cleavage of the antibody itself, an unlikely event. The off-target toxicity of ADC using noncleavable linkers should thus be minimal. In addition, proteolytic cleavage of the ADC yields a drug moiety substituted with a remaining fragment of the antibody; the peptide fragment is likely polar and charged, preventing the escape of the drug from the cell. The peptide-substituted drug is thus retained within the cell, limiting its ability to kill neighboring cells or to enter circulation and kill nontarget cells; the antibody fragment may also limit transporter-mediated resistance to the drug (though it is unlikely to reduce the effects of other resistance pathways).

Exemplary cleavable and noncleavable linkers used in ADCs are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Exemplary ADC linkers: (A) acid labile hydrazone linker; (B) enzyme cleavable Val-Cit linker; (C) glutathione-sensitive disulfide linker; (D) noncleavable maleimidomethyl cyclohexane-1-carboxylate (MCC) linker.

2.2.1.3. Branched Linkers

Branched linkers have been devised for ADC to access ADC with higher DAR.132 The closest technology to clinical use is that developed by Mersana Therapeutics in which a glycerol-glycolaldehyde condensation polymer (Fleximer) with pendant esters of mercaptocarboxylic acids and drug moieties is prepared and attached to an arylmaleimide-substituted antibody.133,134 The method can produce ADC with a DAR of 10–15. A vincristine-functionalized trastuzumab using the technology had antitumor activity similar to and lower toxicity than the corresponding conventionally generated ADC. Two ADC using this technology have entered clinical trials. Upifitomab rilsodotum135,136 uses MMAF as the warhead; in a Phase 1/2 trial, it did not show improvement over control against platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. A second ADC, XMT 2056, uses the same platform but uses an STING agonist as the warhead. It is in Phase 1 clinical trials for treating metastatic HER2-positive tumors; unfortunately, its trials are in clinical hold due to a severe adverse event.137 Other branched linker methodologies use transglutaminase-mediated coupling of trisubstituted piperidine-containing amines with sequence-modified antibodies,134,138 the preparation and use of carbamoylethyl- and carbamoylethoxy arylmaleimides by Firefly Bio as branched linkers for ADC,139 the use of pentaerythritol-derived linkers containing amine or oxime moieties for antibody conjugation, fluorescent linkers, and three azide moieties for attachment pf payloads by Sapozhnikova et al.,140 and the preparation and use of disubstituted tetrahydropyrazinoindoles as antibody linkers via condensation of aldehyde-containing antibodies with trisubstituted indolemethanehydrazines by R.P. Scherer Technologies.141 Linkers that carry two drug units per linker have been also reported for typical hinge cysteine-based conjugation.142,143

2.2.2. What Types of Linkers Are Used in ADCs? Why?

Of the currently approved ADCs, cleavable linkers (particularly enzyme-cleavable linkers) predominate, with 11 out of 13 USFDA-approved ADCs having cleavable linkers19 (and eight of the ADCs having enzyme-cleavable linkers). Thus, while premature release of the payload (as seen in Mylotarg) in ADC possessing cleavable linkers can lead to unacceptable off-target toxicity and reduced exposure that potentially affects efficacy, the benefits of selective linker cleavage appear to outweigh the liabilities. One way in which this may occur is by the “bystander effect”.127 If the payload is released either near a target cell or is transported from (or diffuses from if the drug lacks charged groups such as carboxylates), then the drug can be taken up by neighboring cells, resulting in their death. In most cases, cells in the vicinity of a tumor cell are likely to be tumor cells; thus, the bystander effect allows the ADC to affect cells in the vicinity of an antigen-presenting cell. Since one of the many ways that cancer cells evade treatment is to downregulate the production and expression of surface antigens, ADCs using cleavable linkers can take advantage of the bystander effect and circumvent some of the resistance modes of tumor cells.

2.3. Drugs Incorporated into ADCs

2.3.1. What Are the Requirements for Drugs To Be Incorporated as Payloads into ADCs?

First, antibodies such as IgG (approximately 150 kDa) are large; attachment of many drug molecules to an antibody often makes it more lipophilic, causing aggregation of the ADC and subsequent degradation and inactivation. The number of drug molecules linked to an antibody is small (in most cases, four or fewer), making the effective dose of the drug in an ADC small. In addition, the low numbers of antigens per cell and the imperfect delivery of ADC to cells further reduces the likely dose of drug from ADC.131 Thus, because only a small dose of drug is possible, the drug chosen for use in an ADC needs to be highly potent (exhibiting its effects at nM to pM concentrations) to boost efficacy. However, the effective dosage of drug to cells from ADCs has shown a plateau in mice, indicating that a sufficient ADC can be delivered to a tumor to oversaturate it with the drug (with the caveat that the drugs delivered in this case were highly potent and adapted for the ADC).144 Second, drugs in ADCs are attached to antibodies and are not free to diffuse into cells. If the linker between a drug and an antibody remains intact until delivery, the antibody controls where the drug is released, allowing less selective drugs to be used in ADCs than those given systemically. Finally, the drug needs to be stable both to storage and to administration; since ADCs are administered parentally, the drug in an ADC needs to be stable in blood and plasma (though attachment to an antibody may provide steric shielding for a drug and thus may reduce its reactivity and increase its stability). A secondary consideration is if the ADC is being used in combination with other drugs, the ADC warhead should act on a different target, a different biological pathway, or at a different phase of the cell cycle than the other drugs being used.3

2.3.2. What Types of Drugs Are Used as Payloads for ADCs?

Auristatins are tubulin polymerization inhibitors derived from the marine natural product dolastatin 10, with potencies of 50–100 pM.88 Monomethyl auristatins F and E have been used as warheads for ADCs such as Adcetris, Polivy, and Blenrep.145

Maytansinoids are ansa-macrolide natural products isolated from the shrub Maytenus serrata.146 They bind tubulin and prevent its assembly into microtubules, thus inhibiting mitosis and cell replication.147 Maytansinoids were tried as antitumor agents but were not effective at tolerable concentrations. The maytansine DM1 is the warhead of the ADC Kadcyla.88

Camptothecin and its analogs such as irinotecan, topotecan, govitecan, SN-38, exatecan, and deruxtecan inhibit topoisomerase 1, an enzyme that unwinds and cuts a single strand of supercoiled DNA, allowing it to be repaired and replicated;148 its inhibition leads to DNA cleavage and cell death. A variety of camptothecin analogs have been tried as antitumor agents, but their aqueous solubilities and side effects have hindered their use as antitumor agents.149 Some of the camptothecins have also been susceptible to export by ABC transporters; annulation of an additional ring as in exatecan prevented transport but caused myelotoxicity, which was reduced further by addition of a maleimide-terminated peptide to form deruxtecan. Camptothecin analogs are warheads in the USFDA-approved ADC Enhertu and Trodelvy.88

Pyrrolobenzodiazepines such as tesirine and talirine were derived from the natural product anthramycin.150 They alkylate DNA with extremely high potencies (as low as 100 fM).88 One pyrrolobenzodiazepine (SJG-136) was tried as an antitumor agent but progressed only to Phase I trials due to significant toxicity with no antitumor response.151 Their high potency makes them attractive warheads for ADCs.152 A variety of ADCs with pyrrolobenzodiazepine warheads have been tried, with one (Zylonta) having been approved as of December 2021 for the treatment of B-cell lymphomas. Their dimeric nature and the presence of two alkylating moieties allows them to cross-link DNA, which creates DNA damage that is difficult to repair. However, these same features are also likely responsible for undesired off-target toxicity. Structurally related indolinobenzodiazepine dimers have also been studied as warheads for ADC;153 incorporation of monoamine indolinobenzodiazepines has been used to generate antitumor ADC with reduced off-target toxicities.131,154

Calicheamicin γ1 and related natural products such as dynemicin contain strained enediyne moieties. Under reductive conditions, DNA-bound calicheamicin undergoes Bergmann cyclization to generate diradicals which cleave both strands of DNA, leading to damage which is difficult or impossible for cells to repair. It inhibits DNA replication at pg/mL concentrations155 but is also toxic as a result. The combination of potency and toxicity suggested the potential use of calicheamicin γ1 in ADCs. The first approved ADC, Mylotarg, incorporated calicheamicin as a warhead; it was approved in 2001 but withdrawn in 2010 because of its toxicity. Development of modified dosing allowed Mylotarg to be reapproved in 2017 with an expanded patient population.124 The ADC Besponsa also uses a calicheamicin derivative as a warhead.

Many other compounds have been tried as warheads for ADC. Duocarmycins such as CC-1065 and seco-DUBA are DNA-alkylating agents effective at nanomolar to picomolar concentrations.156 Tubulysins are noncanonical peptides containing thiazole moieties that act as microtubule polymerization inhibitors and are active against cancer cells at nanomolar to picomolar concentrations,157 making them attractive candidates for ADCs.158 However, some of the tubulysins are unstable in aqueous environment and can show unselective toxicity in cancer cells. Cryptophycins are macrolides which inhibit tubulin polymerization at picomolar concentrations; however, trials against cancer showed toxicity but not efficacy.159,160 Despite this, their potency has made them attractive payloads for ADCs.161 The spliceostatins and thailanostatins are natural products that inhibit the spliceosome, modifying mRNA sequences and thus influencing protein expression. They have shown inhibition of cancer cells at nanomolar concentrations162 and hence are potential ADC payloads.163 Doxorubicin is an intercalating agent for modification of DNA which was used as one of the first payloads for ADCs but was not effective because of its low potency. However, if the DAR of doxorubicin conjugates can be increased by newer conjugation methods, it may prove to be an effective warhead for ADCs. Alternatively, more potent anthracycline drugs have been developed. For example, PNU-159682 is an anthracycline acting by a similar mechanism to doxorubicin which was found to be nearly 1000 times more potent than doxorubicin.164,165 This enhanced potency enables ADCs incorporating it to be highly effective.166 α-Amanitin, a fungal toxin which inhibits RNA polymerase II, is a significant cause of liver failure and death from toxic mushroom ingestion.167 Its toxicity, robustness, and moderate size make it a reasonable choice as a warhead for ADC.168 Protein toxins have been used as warheads for ADCs; for example, Pseudomonas exotoxin A169 is the warhead for the USFDA-approved ADC Lumoxiti.170 Diphtheria exotoxin171 has also been used as a payload for ADC.172

Finally, immunomodulating agents have been tested as antibody payloads, either to suppress immune responses for anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressant activities or to enhance the immune response to cancer.173−177 In addition, an ADC with antibiotic warheads have been designed for use as an antibacterial agent.178

2.4. Conjugation Methods for Antibody–Drug Conjugates

2.4.1. What Are the Important Features of a Conjugation Method?

As with the linking moiety, it is important that the method of attaching a drug to an antibody through a linker does not alter the activity or stability of the drug or the antibody. In addition, conjugation should be efficient, proceed in high yield (so that as little as possible of the reagents are used per unit of ADC) and proceed as rapidly as possible. It should also be selective and predictable so that the locations of attachment of a drug to the antibody are controllable, known, and consistent.179 While it would be optimal to have a single species generated by a method, it is not necessary as long as the ADC is composed of a consistent mixture of species with consistent stability, biological and physical properties, and biological activity.

2.4.2. What Is the Structure of an Antibody? Where Can It Be Functionalized?

Most antibodies used for ADC are immunoglobulins, of which the most commonly used is immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Figure 1).127 IgG contains two heavy chains and two light chains. The heavy chains are attached to each other and to the light chains through four (interchain) disulfide S–S bonds that hold the antibody together. Twelve other intrachain disulfide bonds control the tertiary structures of the light and heavy chains. There are also roughly 80 lysine residues in a typical antibody, of which 40 may be functionalized. In addition, one of the heavy chain glutamine residues is substituted with a branched-chain heptasaccharide which improves the ability of the antibody to trigger an immune response.180

2.4.3. Conjugation Methods to Native Antibodies

2.4.3.1. Lysine

Under most circumstances, however, the reactivity of specific residues is rarely controlled, unless the basicity of a residue is significantly altered by its position in the protein sequence or by the side chains of nearby residues. In most cases, the average number of residues functionalized can be controlled by stoichiometry but not the position of functionalization. The lysine ε-amine forms stable amides with acylating agents such as N-hydroxysuccinimidyl esters (particularly sulfonated N-hydroxysuccinimidyl esters,181 which have better aqueous solubilities), benzoyl fluorides,182 and acid anhydrides.183 Acylating agents can form esters with tyrosine, threonine, or serine residues, but the esters are not stable; thus, if not prevented, some of the acylating agents will be consumed, decreasing the amount of drug attached to the antibody. Affinity peptides have been used to control the location of conjugation with antibodies;184 for example, binding of a peptide-containing acylating agent to the Fc domain of an antibody directs the acylation reaction to nearby residues185 and the conjugation method has been performed on gram scale using a peptide-substituted thioester.186 Cleavage of the peptide yielded a thiol available for further reaction.

2.4.3.2. Cysteine

Cysteine is the most common residue functionalized in antibodies because the sulfur atom of its side chain is highly nucleophilic. Cysteine’s thiol moiety is acidic enough for its anion to be accessible under physiological conditions; the resultant anion is more reactive toward electrophiles than other residues but is not basic enough to cause side reactions. IgG does not natively contain free cysteine residues, requiring some of the disulfide bonds of the antibody to be cleaved in order to allow functionalization. The four interchain disulfide bonds are most often used;187 while this preserves the structure and function of the individual antibody fragments, the stability of the antibody may be compromised. Selectivity among the cysteine residues is difficult; while a single species can be formed if all eight cysteines are functionalized (as for the approved ADC Troldelvy and Enhertu), most methods yield mixtures of products.

The most common monofunctionalization reagent used is the maleimide. Maleimides undergo Michael additions of thiols readily under ambient conditions to yield alkylthiosuccinimides.188 The thiol-succinimide adducts, however, can undergo retro-Michael addition, which could lead to either incomplete functionalization of the antibody or premature release of the drug from the antibody and undesired toxicity. Ring opening of the imide to form a carboxylate-containing amide reduces retro-Michael reactions substantially.189 Exposure of the imide product to mildly basic conditions can be used to form the carboxylate;190 the presence of nearby positively charged residues facilitates imide ring opening and stabilizes the maleimide adducts. Intramolecular reactions can also be used to stabilize the cysteine adducts.191 Other monofunctionalization reagents for cysteine include palladium aryl complexes to yield aryl thioethers,192 disulfides derived from exogenous thiols (particularly acidic thiols),193 and alkenyl and alkynyl phosphorus194,195 and iodine reagents.196 The known reactions of haloacetamides with cysteine residues can also be used;96 while stable thioether linkages are formed, their reactivity may lead to difficulty in controlling the number of appended drug moieties or their residue selectivities.

Disulfide rebridging can be used to reduce the potential instability caused by complete functionalization of the cysteines generated by reduction of the four interchain disulfide bonds.179 Reaction of the intermediate octathiols with biselectrophiles yields bisthioethers in which two of the cysteines are connected by alkyl or aryl groups; the thioether linkages are robust and can stabilize the dimeric antibody structure. The number of bridges formed (and thus the number of drugs incorporated) is easily controlled; the structure of the alkylating agent and the number of available sites for drug conjugation on it determine the carrying capacity of the ADC. One disadvantage of the method is that the biselectrophiles are likely to not be commercially available and thus require synthesis. A variety of reagents has been developed for disulfide rebridging. Abzena developed bis(sulfonylmethyl)methyl ketones (ThioBridge) which undergo sequential elimination and Michael reactions to yield thioether-substituted ketones.197 The payload can then be attached with alkoxyamines or by reductive amination. A similar method for rebridging has been used by Novartis with dichloroacetone as the biselectrophile.198 Maleimides with bromo-, iodo-, or arylthiol-substituents undergo Michael/retro-Michael reactions to yield substituted maleimides;199−201 incubation at pH 8.4 yields maleimidic acids which are resistant to Michael and retro-Michael reactions at the linker. Dihalo- or bis(phenylthio)pyridazines undergo analogous reactions to dihalo- or bis(arylthiol)maleimides but are resistant to linker cleavage by retro-Michael reactions.202 The pyridazines can incorporate multiple drug moieties; in addition, their reactivity can be controlled by temperature. Other biselectrophiles used for disulfide rebridging are aryl di(bromomethyl)quinoxalines (C-Lock, Concortis Therapeutics203), cis-platinum diamine complexes (Invictus Oncology),204 and divinylpyrimidines.205

2.4.3.3. Other Residues

The N-terminal amino group of peptides is less basic than the ε-amino groups of lysine residues, making selective reactions at the N-terminus of the antibody heavy chains possible. The proximity of the N-termini to the receptor binding site of the antibody may complicate functionalization. While reaction at the C-terminus would be preferable (because the C-terminus of the heavy chains is distant from the antigen- or receptor-binding sites of the antibody), chemical methods for doing so are uncommon. Transamination at an N-terminal glutamine residue with a formylpyridinium salt followed by reaction with an alkoxyamine yielded a stable N-terminal oxime ether.206 Oxidation of an N-terminal serine moiety yields a formylglycine residue, which can react with an alkoxyamine to form an oxime ether or can form nitrogen heterocycles by condensation with carbonyl compounds.

Arginine residues are unreactive under physiological conditions because the guanidine conjugate base of the native guanidinium ion is highly basic, inhibiting reaction. However, dicarbonyl compounds can react with amidines or guanidines to yield stable imidazoles. An azidophenylglyoxal was designed for reaction with arginine residues to form azidophenylaminoimidazole moieties; azide–alkyne cycloaddition with a terminal alkyne-substituted warhead yields the functionalized antibody.207 Finally, Ugi reactions of a lysine residue, a nearby aspartate or glutamate residue, an azidoaldehyde, and an isonitrile formed azide-functionalized macrocycles amenable to drug attachment via azide–alkyne cycloaddition.208

2.4.4. Conjugation Methods for Non-Native Antibodies

If an ADC with a precisely known structure is desired, native antibodies may not allow sufficient selectivity. Incorporating non-native functional groups by modification of the heavy chain sequence makes selective antibody conjugation with existing chemistry possible. Antibodies can be produced either by inoculation of mice with an antigen, by phage display, or by biopanning,209 separation of the cells producing the antibody and hybridization with cancer cells, cloning of the antibody sequence, and insertion into CHO cells.210 Since the antibody DNA and protein sequences are known, they can be modified to obtain antibodies with non-native sequences.210 Multiple methods of sequence modification may be useful.

2.4.4.1. Cysteine Incorporation

IgG normally does not possess free cysteine residues; the cysteines are connected by oxidation to intra- and interchain disulfides. Because the reactivity of cysteine is distinct from other residues, a non-native cysteine residue should be readily functionalizable, and has been used in technologies such as THIOMAB.211 Incorporation of an N-terminal cysteine allows reaction with aldehydes to form thiazolidines212 which slowly releases the aldehyde payload and enables the adducts to be effective as ADC. The position of insertion of the cysteine into the antibody sequence, however, needs to be chosen to minimize perturbation of antibody structure; in addition, as noted earlier, the presence of positively charged residues nearby facilitates ring opening of maleimide conjugates and improves their stabilities to deconjugation. Another caveat of cysteine incorporation is that cysteines form disulfides with glutathione during antibody production which must be reductively cleaved, but methods have been developed to address this issue.213 Recent studies have shown that antibody engineering methods are used to add two or three unpaired Cys residues, boosting the DAR of ADCs to >2 per antibody.109

2.4.4.2. Noncanonical Amino Acids

The use of amino acids containing functionality not normally present in peptides or antibodies allows facile, biocompatible, and selective reactions such as azide–alkyne cycloaddition and oxime ether formation to be used for linking to drugs. However, the biosynthesis of antibodies containing noncanonical amino acids (NCAA) is difficult. NCAA incorporation normally requires one of the stop codons in translation (most commonly, the amber codon UAG) to be suppressed and instead be used to encode the desired amino acid. Amber codon suppression, however, is believed to harm the cells in which it is deployed,214 requiring alterations to the expression methods. Cell-free systems can be used to generate NCAA-containing antibodies, but they lack the ability to glycosylate the finished antibody,215 which reduces its ability to summon an immune response. In addition, the site of incorporation requires optimization to avoid altering the stability or function of the antibody. Antigen- and receptor-binding sites and the hinge regions must be avoided, while solvent-exposed sites are preferred to increase the rate of drug attachment.

p-Acetylphenylalanine,216,217 p-azidophenylalanine,218,219 p-azidomethylphenylalanine,220,221 and azidolysine222−224 are stable in cells and do not alter protein structure significantly. p-Acetylphenylalanine reacts readily with alkoxyamines, while p-azidophenylalanine, p-azidomethylphenylalanine, and azidolysine undergo either copper-catalyzed or strain-promoted azide–alkyne cycloadditions with terminal alkynes or cyclic alkynes, respectively. All can be incorporated into peptides in reasonable yields. N-Propargyllysine is stable and amenable to copper-catalyzed azide–alkyne cycloaddition225 but differs enough in structure from lysine to inhibit its incorporation into peptides.226 Cyclopropene- and cyclopentadiene-substituted amino acids undergo cycloaddition reactions with tetrazines or maleimides to form stable pyrazine or bicycloheptene adducts.227,228 Selenocysteine is a rare but natural amino acid; the selenol group is more acidic and yields an even better nucleophile than a cysteine residue. Incorporation of selenocysteine into an antibody was achieved,229 despite low yields because of undesired termination at the erstwhile stop codon. Finally, suppression of two of the three stop codons allows peptides to be translated with two NCAA, which allows two different warheads to be attached to a single ADC.230 The difficulty of incorporating NCAA into an antibody likely means that the use of NCAA-based conjugation reduces the possible drug capacity of the ADC.

2.4.4.3. Incorporation of Additional Amino Acids

Addition of amino acid sequences to the C-terminus of the heavy chain of an antibody can be used to selectively conjugate drugs. (While the addition of amino acids increases the size of the ADC, large addends are required to perturb the antibody’s movement because it is already large, 150 kDa in the case of IgG). The cysteine in a π-clamp sequence (FCPF) selectively reacts with perfluorinated benzenes to yield substituted fluoroaryl thioethers.231 The cysteine in a different cysteine-containing sequence (LCYPWVY) undergoes reaction with dibenzocyclooctynes to yield stable dibenzocyclooctenyl thioethers.232 Both reactions can thus be used to attach drugs to an antibody. Appending a receptor to the C-terminus of an antibody can be used to attach drugs to the antibody if a covalent or irreversible inhibitor of the receptor exists; this method was used with CD38.233 Finally, a catalytic antibody sequence (38C2) was incorporated into an IgG1 antibody (without significant alteration of its properties); the antibody alters the basicity of nearby lysine and arginine residues, making their selective functionalization possible.207 The size and position of added sequences are likely to limit the drug loading of an antibody.

2.4.5. Enzymatic Methods for Conjugation

Enzymatic methods can circumvent some of the limitations that exist in chemical methods to conjugate drugs to antibodies. The evolutionary constraints for enzyme function are well-suited for chemoselective attachment of substrates to antibodies, and the development of bioorthogonal chemistries to interrogate protein function has further enhanced their capabilities.

Some enzymic modifications allow moieties to be directly attached to an antibody; while they require specific chemical matter to be present or may require mutant or additional sequences to be added to an antibody, the methods need only one step to functionalize antibodies. In most cases, the need for a single residue or functional handle for specificity limits the number of warheads that can be easily attached to an antibody. Transglutaminases exchange the amino group of a glutamine’s amide moiety for another amine, allowing for facile attachment of amino-containing payloads or linkers. A glutamine residue (Q295) in the heavy chain possesses a carbohydrate moiety that helps to determine the physical properties and immune responses of the antibody; removal of the carbohydrate can have negative consequences for ADC performance234 but provides a reliable attachment point for payloads.235 Alternatively, inclusion of glutamine residues (either by extension or by mutation of the antibody sequence) allows transglutaminase-mediated coupling reactions to attach payloads without perturbing the immune effects of the antibody.236 A large variety of amine-containing linkers can be used; with mutant transglutaminases, hydrazones (acyl hydrazines) can also be exchanged with glutamine residues.237 Prenyltransferases attach farnesyl or geranylgeranyl (15- or twenty-carbon) pyrophosphates to cysteine residues followed by two aliphatic amino acid residues.238 One of the prenyl methyl groups can be substituted; when a ketone or azide moiety is included, bioorthogonal coupling methods are applicable to attachment of linkers or payloads.239 Sortases attach N-terminal substituents to peptides or antibodies with the C-terminal sequence LPXTG–OH (effectively coupling an amine to the C-terminal glycine), allowing attachment of N-terminal substituents to an antibody where they are less likely to interfere with other functions.240 Butelase 1 appends dipeptides to C-terminal asparaginylhistidylvaline moieties to form dipeptidyl asparagine amides; the enzyme has been used with sortase A and modification of the antibody light chains to provide doubly modified antibodies.241 SpyLigase attaches a peptide containing an N-terminal tag to a peptide with a corresponding C-terminal tag, eliding the intervening peptide and forming a new substituted antibody.242 Phosphopanteinyltransferases acylate serine residues with CoA thioesters;243 while the functionality that can be incorporated is broader (requiring only a CoA thioester, the ester linkage formed may not be sufficiently stable or persistent.

Other enzymic methods convert native peptides or amino acid residues to reactive moieties that are amenable to conjugation with a variety of linkers or warheads but do not directly attach substituents to antibodies. Formylglycine-generating enzyme (FGE) reacts with peptides with the N-terminal sequence H-CXPXR (X = any amino acid), again requiring mutation of the antibody sequence. FGE generates formylglycine residues from the N-terminal cysteine;244 the aldehyde moiety is amenable to condensation with oxime ethers or with electron-rich arylmethylhydrazines in iso-Pictet-Spengler reactions to form aryl-fused tetrahydropyridazines.245 FGE-mediated conjugation may be useful when conjugation with cysteines is not compatible with the linker chemistry or when different requirements for linker stability are necessary. Tyrosinases and horseradish peroxidases oxidize tyrosine residues to form ortho-quinones which can undergo either Michael addition of amines to the quinones and rearomatization to yield stable 3-aminotyrosine residues246 or Diels–Alder reactions.247 While aminotyrosine residues are potentially oxidizable, the carbon–nitrogen bond formed is robust.

Finally, the sugar moieties present in the antibodies can be remodeled to yield attachment points for conjugation. Fucose, sialic acid, and galactose moieties contain vicinal cis-hydroxyl groups which can be oxidatively cleaved by sodium periodate to yield dialdehydes; condensation with oxime ethers or hydrazines yields oxime ethers and hydrazones.248 While the oxidation provides multiple attachment points for payloads, it also can oxidize methionine residues of the antibody, which increases clearance and decreases efficacy.249 An alternative method is to alter the sugar moieties by incorporating sugars with non-native functionalities into the pendant sugar moieties. For example, endoglycosidases catalyze the exchange of the terminal aminosugar moieties of saccharides, incorporating 2-N-acetylglycosamines into saccharides via oxazoline intermediates.250 Glucosyl-, galactosyl-, and thiofucosylamines with azide or ketone substituents (or, with thiofucosylamine, a thiol group) can thus be swapped into the sugar moieties of antibodies;251 reaction of azides with alkynes (using copper catalysis or strained alkynes), of ketones with alkoxyamines, or of thiofucose moieties with maleimides immobilizes payloads onto antibodies. Both methods may alter the immune functions of the antibody–drug conjugate by sugar modification and thus the activity of the conjugate.

2.4.6. Drug–Antibody Ratio

Drug–antibody ratio (DAR) characterizes how many drug molecules an ADC can carry; theoretically, it should characterize the ability of an ADC to deliver drug to a tumor and thus positively correlate to effectiveness.19 However, the presence of large numbers of drugs (and thus large numbers of linkers) on an ADC perturbs the properties of the antibody. Lipophilic drugs and linkers increase the aggregation of ADC, preventing them from reaching their site of action; they may also hinder access to binding sites necessary for antigen recognition or binding, reducing the activity of the ADC. Reducing the lipophilicity of linker moieties has been used to reduce the negative consequences of antibody functionalization,121 but not the alteration in ADC properties. In addition, significant toxicity has been noted for ADC with high DAR (DAR ≥ 8) and high DAR may increase the clearance of ADC (reducing their residence time and effectiveness).252 DAR is an important analytical property of ADC; the ability to produce ADC with consistent DAR is likely to lead to ADC with consistent properties and biological activity and thus is likely a critical attribute for ADC synthesis and production.

2.4.7. What Types of Drugs, Linkers, and Conjugation Methods Have Been Used for Approved ADCs?

A variety of types of drugs are used in clinically approved ADCs and in ADCs in clinical trials (discussed further in the text). Calicheamicin, maytansinoids, auristatins, duocarmycins, and pyrrolobenzodiazepines have been used, while tubulysin-, eribulin-, and amberstatin-containing ADCs are being researched in clinical trials.19 The drugs in ADCs are highly potent (effective at nM to pM concentrations); the difficulty in delivering significant amounts of drug to tumors with an ADC (as noted earlier) may explain the prevalence of potent drugs in ADC.

Most of the currently approved drugs and nearly all ADCs in clinical trials use cleavable linkers, and in most cases, enzyme-cleavable linkers.19 The preference for cleavable linkers indicates (as noted) that the contribution of bystander effects to the ADC clinical effectiveness is critical. In addition, the continued development of enzyme-cleavable linkers is likely important. While the toxicity of Mylotarg and its subsequent withdrawal and reapproval provided concern for chemically reactive linkers, the incorporation of chemically stable linkers allows the best of both worlds. The controlled drug release provides safety assurance as well as increased antitumor response via the bystander effect. The use of cleavable linkers also may prevent or reduce the resistance of tumors to ADCs by decreasing the effect of antigen loss on toxicity and releasing ADCs from the requirement for lysosomal cleavage.

As of mid-2023, all of the approved ADCs used conjugation to lysine or cysteine residues; none of the currently approved ADC used site-selective functionalization methods,19 while few of the ADCs use site-selective conjugation methods. It is unclear why site-selective methods have not been more effective; knowledge of antibody structure and function should be sufficient to avoid antibody inactivation or a loss of function. Methods to site-specifically conjugate drugs to antibodies were less advanced and may have been insufficient for incorporation into a drug (or may have had insufficient data and thus too much risk to incorporate into a clinical candidate). The reasons for the failures in the current trials, however, appear unclear.

ADCs currently approved and in clinical trials vary significantly in their DAR as well; DAR between 1.8 and 8 have been tried (see Section 7.3 below enlisting approved ADCs), with most possessing DAR around 4. The DAR may be an artifact of the conjugation method; immobilization using the interchain bridging disulfides should yield ADC with a DAR of roughly 4. The presence of larger linker and drug moieties may also require a lower DAR to avoid aggregation or inactivation of the ADC. ADCs with higher DARs and less-potent drugs have not yet reached clinical trials; it is not clear whether this is due to limitations on DAR, ineffectiveness in previously tried high-DAR ADCs with less potent payloads, or some other reason.

2.5. Selection/Optimization of Target Antigen Moiety

The efficacy of an ADC depends on the expression levels of target antigens. ADCs are designed to release the payload upon interaction with cognate antigens.88,253 As the field continues to grow, over 50 antigens have been identified as successful ADC targets under various clinical evaluation stages.253,254 To achieve optimal therapeutic efficiency, antibody–antigen binding affinity can be optimized on a case-by-case basis depending on the tumor size, target antigen concentration, and receptor-mediated internalization kinetics.

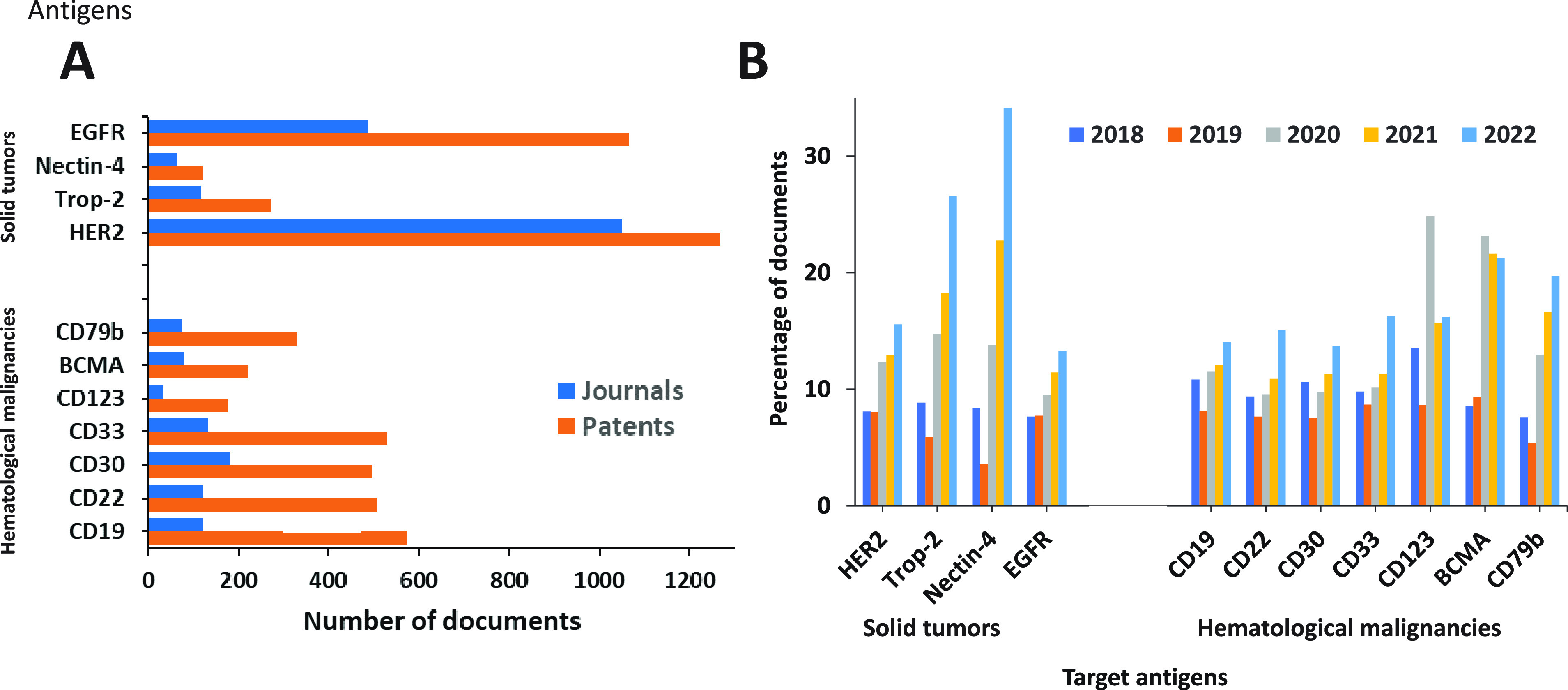

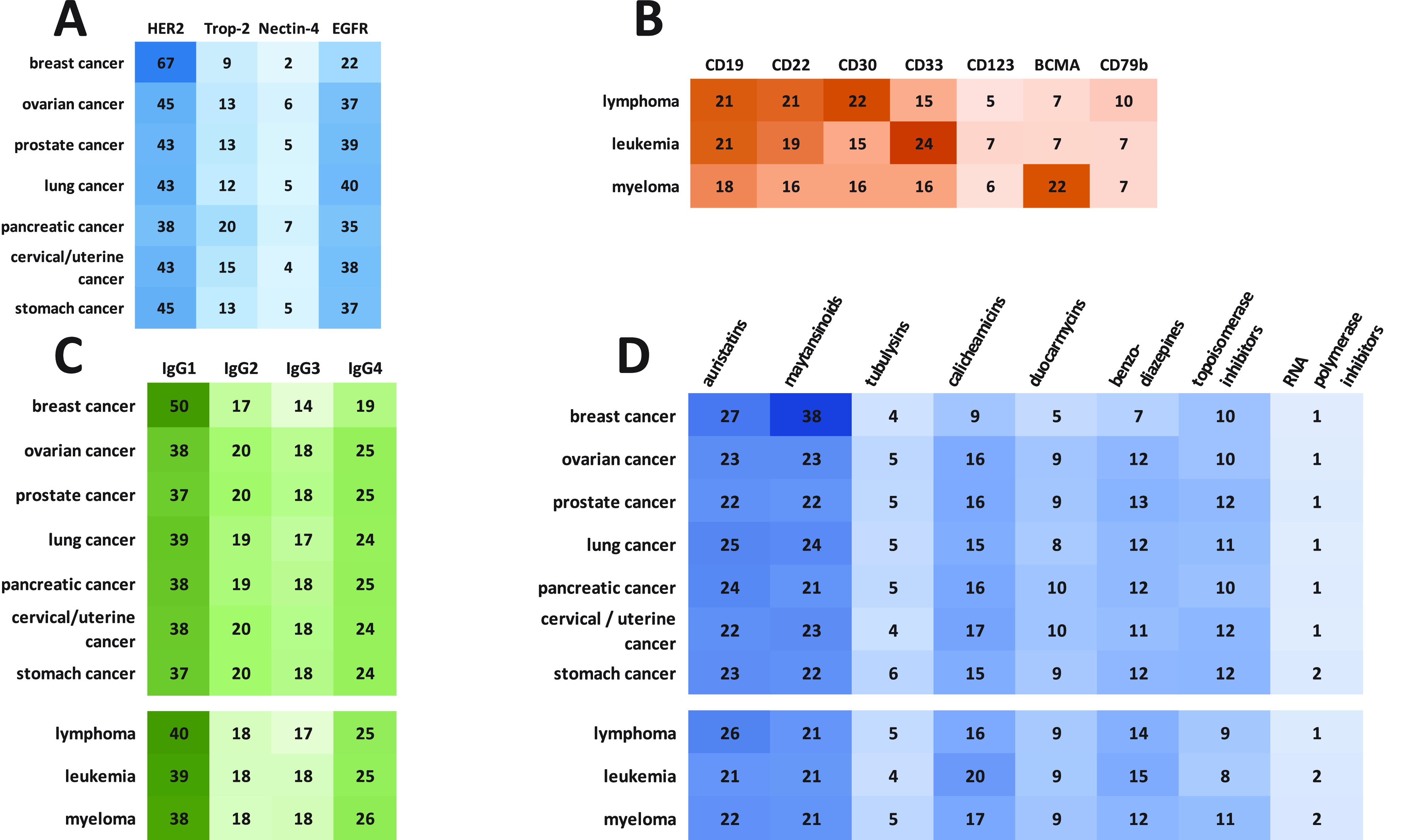

The most used antigenic targets are CD19, erb-b2 receptor tyrosine kinase 2 (ERBB2), HER2, CD22, CD30, CD33, CD79b, and Mesothelin (MSLN).46 These antigenic markers vary depending on the tumor type. Antigens such as HER2, EGFR, 5T4, trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2 (TROP2), and nectin 4 are commonly used ADC targets in solid tumors due to their higher level of expression in malignant cells when compared to the nonmalignant ones.46,255,256 For hematological cancers, markers such as CD30, CD22, CD79b, CD19, CD138, and B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), which are distinct from solid tumor markers, are commonly used.88 For example, CD30, the target of brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris by Seattle Genetics), is mainly expressed by the malignant lymphoid cells of Hodgkin lymphoma and anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). Likewise, for specifically targeting B cell lineages, markers such as CD22, CD79b, and BCMA are used. These markers have successfully been used as the targets of inotuzumab ozogamicin (for the treatment of relapsed or refractory (R/R) B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia), polatuzumab vedotin (for R/R diffuse large B cell lymphoma), and belantamab mafodotin (for R/R multiple myeloma), respectively.257,258 Apart from these well-known targets, work to identify suitable antigenic targets in the tumor microenvironment, such as in the stroma and vasculature, is ongoing.

A successful antigenic target of an ADC should be uniformly and heterogeneously expressed on the surface of target cells or other components of the tumor microenvironment and have minimal to no expression in off-target sites.259,260 Other essential factors include the internalization and processing of ADCs that help in their cellular uptake and increase the efficiency of the cytotoxic drug. In addition, it is advantageous that ADCs are designed against functional/oncogenic targets as they can have higher antitumor activity; for example, data from preclinical studies suggest that HER2-targeted ADCs T-DM1 and T-DXd having anti-HER2 mAb trastuzumab’s Fab region prevents ligand-independent HER2 dimerization, inhibiting HER2 downstream signaling.

Once the antibody in an ADC binds to the target antigen, it is internalized via the early endosome, and the internalization rate and efficiency depend on the target antigen and the payload. Affinity correlates well with internalization with higher affinity often resulting in rapid internalization up to a ceiling limit.88 However, a very strong binding affinity between the antibody and target antigen can lead to uneven distribution of ADCs in solid tumors due to the presence “binding site barrier”. This leads to stronger binding of antibodies with the antigens presents on cells near blood vessels and less penetration away from the tumors.261,262

Once ADCs are inside the cell, the endosomes containing them mature into late endosomes and finally fuse with lysosomes. This is followed by the release of cytotoxic payloads in the lysosome upon linker cleavage or antibody degradation. The payload eventually escapes into the cytosol to exert its effects. ADCs with cleavable linkers can release drug to neighboring cells both with and without ADC internalization.263,264 ADC with noncleavable linkers require proteolysis of the ADC for drug release. Proteolysis yields drugs with an attached amino acid residue (lysine or cysteine) which is charged at cellular pH.265 The ability of drugs to diffuse out of the cell depends on their lipophilicity; charge impairs their ability to diffuse across the membrane and thus leave the cell through passive transport. ABC transporters prefer neutral and hydrophobic compounds and export neutral hydrophobic drugs out of the cell, so drugs with amino acid residues derived from ADC catabolism are poor substrates for ABC266 and require help to leave the lysosome267 and the cell. The susceptibility of payloads to active transport decreases the effectiveness of ADC but also makes cells that do not take up the antibody subject to its effects. In particular, the bystander effect depends on how much drug can escape a cell and then accumulate in neighboring cells and if it is sufficient to kill them.265

ADCs are used to treat solid tumors, but a heterogeneous expression of antigenic targets in these tumors may be overcome by the ’bystander-killing effect’,84,268,269 where the payload is transferred from the antigen-positive cells to the antigen-negative cells in the tumor microenvironment. The lipophilic payload for internalized ADCs diffuses across cell membranes and significantly contributes to ADC activity against tumors. For some ADCs, the payload release might happen extracellularly, killing antigen-negative cells located in proximity.259

Table 1 summarizes antigens used as targets of ADCs in development and in the clinic.4,254,270,271

Table 1. Target Antigens for ADCs in Development and in the Clinic.

| Disease | Target antigens |

|---|---|

| Breast cancer | CD25, CD174, CD197, CD205, CD228, c-MET, CRIPTO, HER2, HER3, FLOR1, Globo H, GPNMB, IGF-1R, integrin β-6, PTK7, nectin-4, ROR2, SLC39A6 |

| Ovarian cancer | CA125, CD142, CD205, FLOR1, Globo H, mesothelin, PTK7, TIM-1 |

| Prostate cancer | CD46, PSMA, STEAP-1, SLC44A4, TENB2 |

| Lung cancer | CD25, CD56, CD71, CD228, CD326, CRIPTO, EGFR, HER3, FAP, Globo H, GD2, IGF-1R, integrin β-6, mesothelin, PTK7, ROR2, SLC34A2, SLC39A6, Axl, αv β6 |

| Pancreatic cancer | CD25, CD71, CD74, CD227, CD228, GRP20, GCC, IGF-1R, integrin β-6, nectin-4, SLC34A2, SLC44A4, αv β6, mesothelin |

| Melanoma | CD276, GD2, GPNMB, ED-B, PMEL 17, endothelin B receptor |

| Gastric cancer | CD25, CD197 (CCR7), CD228 (P79, SEMF), FLOR1(FRα), Globo H, GRP20, GCC, SLC39A6 (LIV1A ZIP6) |

| Colorectal cancer | CD74, CD174, CD166, CD227, CD326, CEACAM5, CRIPTO, FAP, ED-B, HER3 |

| Bladder cancer | CD25, CD205(Ly75) |

| Liver cancer | CD276 (B7–H3), c-MET |

| Renal cancer | AGS-16, EGFR, c-MET, CAIX, CD70, FLOR1, TIM-1 |

| Multiple Myeloma | CD38, CD46, CD56, CD74, CD138, CD269, endothelin B receptor |

| Head and neck cancer | CD71 (transferrin R), CD197 (CCR7), EGFR, SLC39A6 (LIV1A ZIP6) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | CD19, CD20, CD21, CD22, CD25, CD30, CD37, CD70, CD71, CD72, CD79a/b, CD180, CD205, ROR1 |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | CD25, CD30, CD197 |

| Acute myeloid leukemia | CD25, CD33, CD123, FLT3 |

| Gliomas | CD25, EGFR |

| Mesothelioma | mesothelin, CD228 |

3. Landscape View of Antibody–Drug Conjugate Research–insights from the CAS Content Collection

The CAS Content Collection81 is the largest human-compiled collection of published scientific information, which represents a valuable resource to access and keep up to date on the scientific literature all over the world across disciplines including chemistry, biomedical sciences, engineering, materials science, agricultural science, and many more, thus allowing quantitative analysis of global research publications across various parameters including time, geography, scientific area, medical application, disease, and chemical composition. Currently, there are over 25,000 scientific publications (mainly journal articles and patents) in the CAS Content Collection related to ADC research and development. There has been a steady growth of these documents over the last three decades, with an >30% increase in the last three years (Figure 3). Noteworthy, while in the earlier years scientific journal publications dominated, after around the year 2000 the number of patents clearly outnumber them, correlating well with the initial accumulation of scientific knowledge and its subsequent transfer into patentable applications.

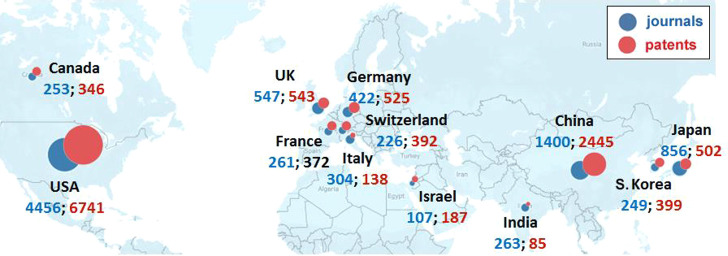

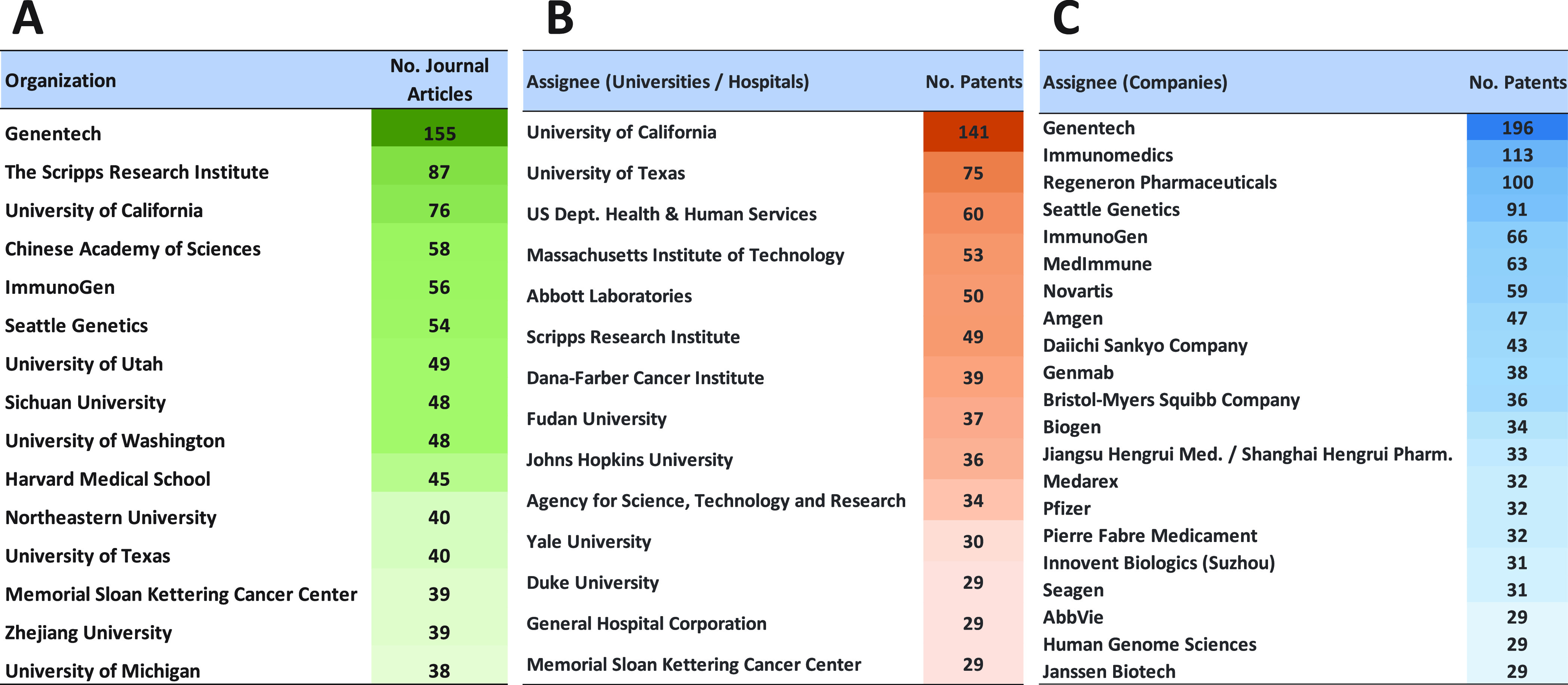

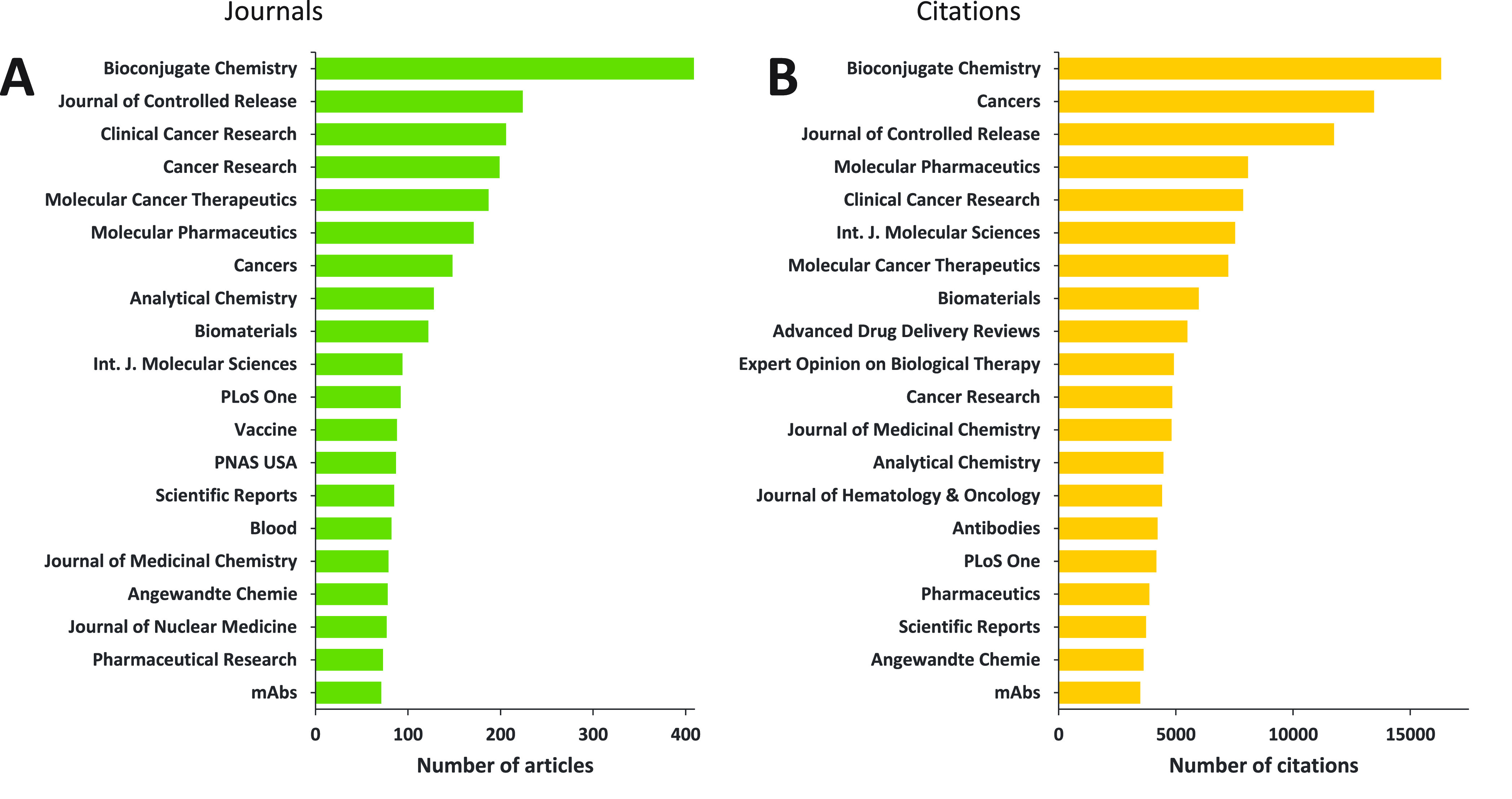

United States, China, Japan, United Kingdom, Germany, and South Korea are the leaders with respect to the number of published journal articles and patents related to ADC research with the United States having ∼3- and ∼2.7-fold greater number of journal and patent publications, respectively, as compared to China (Figure 5). Genentech, the Scripps Research Institute, University of California, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences have the largest number of published articles in scientific journals (Figure 6A). The journal Bioconjugate Chemistry publishes the most articles related to ADC research (Figure 7A) and is the most-cited journal for ADC research (Figure 7B). Unsurprisingly, patenting activity is dominated by corporate players as compared to academics (Figure 6B,C). Genentech, Immunomedics, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, and Seattle Genetics have the highest number of patents among the companies (Figure 6C), while University of California leads among the universities, having nearly double the number of patents as University of Texas, ranked second (Figure 6B).

Figure 5.

Top countries with respect to the number of ADC-related journal articles (blue) and patents (red).

Figure 6.

(A) Top organizations publishing ADC-related journal articles. Top patent assignees of ADC-related patents from universities and (B) hospitals and (C) companies.

Figure 7.

Top scientific journals with respect to the number of ADC-related (A) articles published and the (B) citations they received.

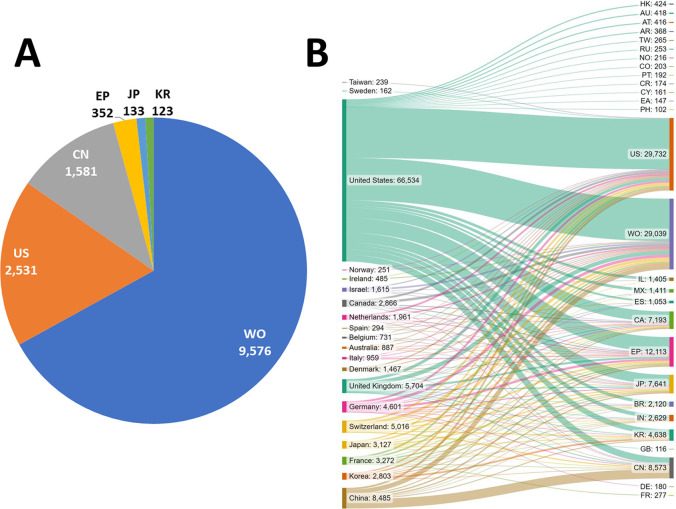

Figure 8A presents the distribution of patents among the top patent offices receiving ADC-related patent applications. The World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) patent office clearly dominates accounting for about 2/3 of patents filed, followed by the patent offices of the United States (US), China (CN), Japan (JP), and S. Korea (KR), and the European patent office (EP).

Figure 8.

(A) Top patent offices receiving ADC-related patent applications. (B) Flow of ADC-related patent filings from different patent assignee locations (left) to various patent offices of filing (right). The abbreviations on the right indicate the patent offices of Hong Kong (HK), Australia (AU), Austria (AT), Argentina (AR), Taiwan (TW), Russian Federation (RU), Norway (NO), Colombia (CO), Portugal (PT), Costa Rica (CR), Cyprus (CY), Eurasian Patent Organization (EA), Philippines (PH), United States (US), World Intellectual Property Organization (WO), Israel (IL), Mexico (MX), Spain (ES), Canada (CA), European Patent Office (EP), Japan (JP), Brazil (BR), India (IN), South Korea (KR), Great Britain (GB), China (CN), Germany (DE), and France (FR).

Patent protection is territorial, and therefore the same invention can be filed for patent protection in several jurisdictions. We thus searched for all related files pertaining to ADCs. Certain patent families might be counted multiple times when they have been filed in multiple patent offices. Figure 8B presents the flow of patent filings from various applicant locations to a variety of patent offices of filing. Most of the applicants tend to have a comparable number of filings in their home country and at the WO, while also having a sizable number of filings at other patent offices such as the US, European Patent Office (EP), and others.

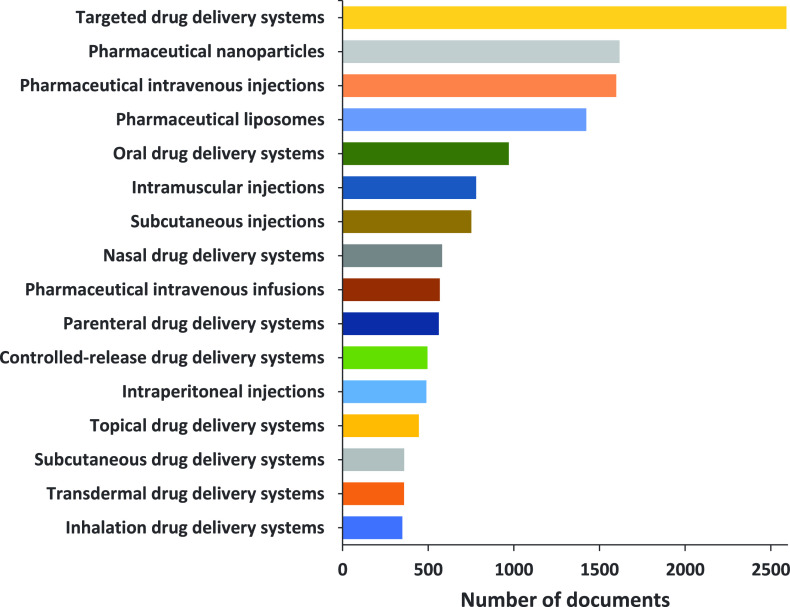

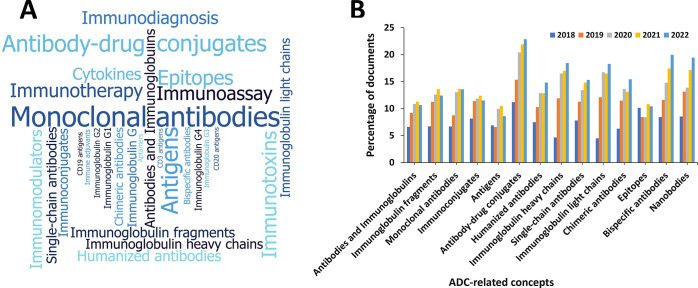

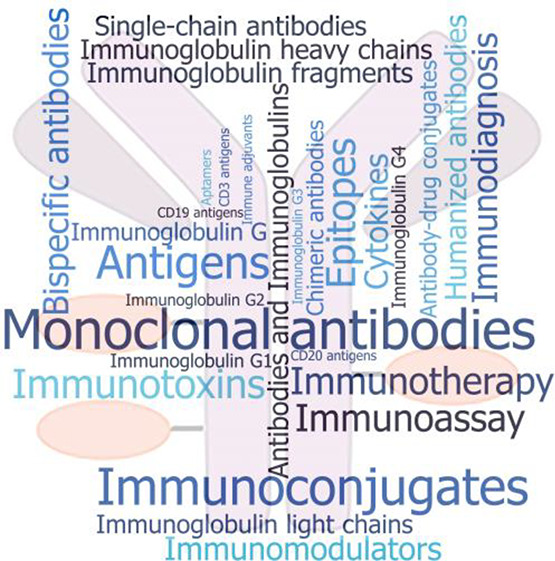

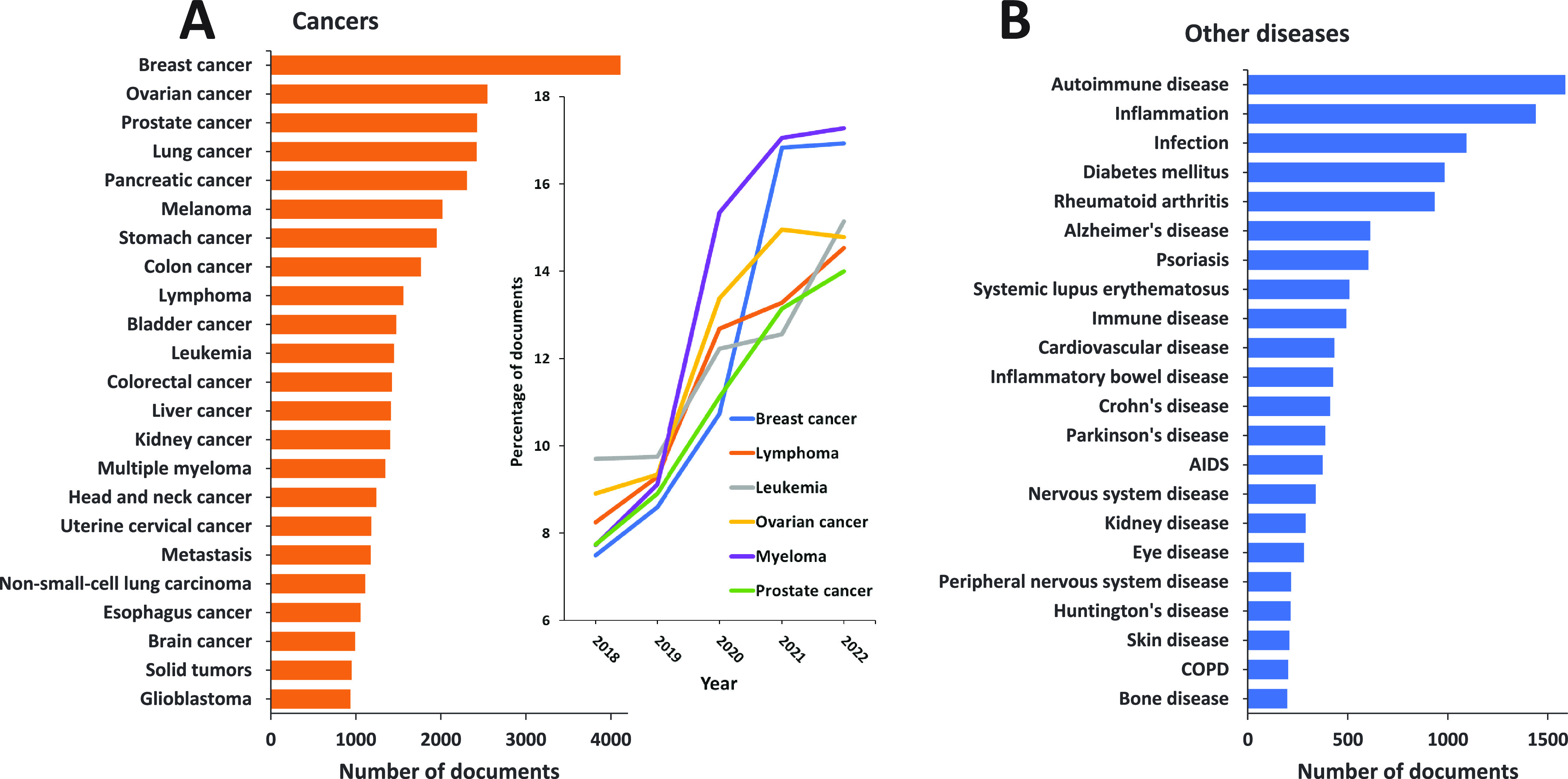

We further explored distribution and trends in the published documents (journals and patents) dealing with various ADC-related concepts. Figure 9 presents a number of the ADC-related documents in the CAS Content Collection concerning neoplastic (A) and other diseases (B). The highest number of documents pertain to breast cancer (mammary gland neoplasm) and lymphoma for solid tumors and hematological malignancies, respectively. This data correlates well with approved ADCs used in the treatment of cancers that are currently on the market.53,55 Breast cancer and myeloma exhibit the highest growth rate in the last five years with respect to the number of documents related to them (Figure 9A, inset). Most ADCs developed thus far, aimed at treating various types of cancer (solid and hematological), have nonetheless been restricted to treating cancer. Challenges in designing ADCs for noncancerous diseases include identifying targeting cell types, a specific surface marker expressed on the targeting cells, and an effective payload drug. So far, not many ADCs have been designed for noncancerous indications, with none yet having successfully progressed through clinical trials to market. With the advancement of ADC platforms and technology, more ADCs for nononcology indications are being developed.272 A search in the CAS Content Collection showed that among the noncancerous diseases, autoimmune diseases, inflammations, and infections are the top pathologies with respect to the number of documents related to ADCs (Figure 9B). Despite obvious complications such as difficulty in penetration through the blood-brain barrier (BBB), our data indicate a growing interest in development of ADCs targeting the brain. The number of documents pertaining to ADCs in the context of neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease (Figure 9B) are on the rise. Recent approvals of antibody treatments for Alzheimer’s disease by the US FDA273,274 also stimulate ADC development for neurological diseases.

Figure 9.

Diseases explored in ADC-related publications: (A) cancers (Inset: Annual growth of the number of documents for the fastest growing solid and hematological cancers for the years 2018–2022); (B) other diseases.

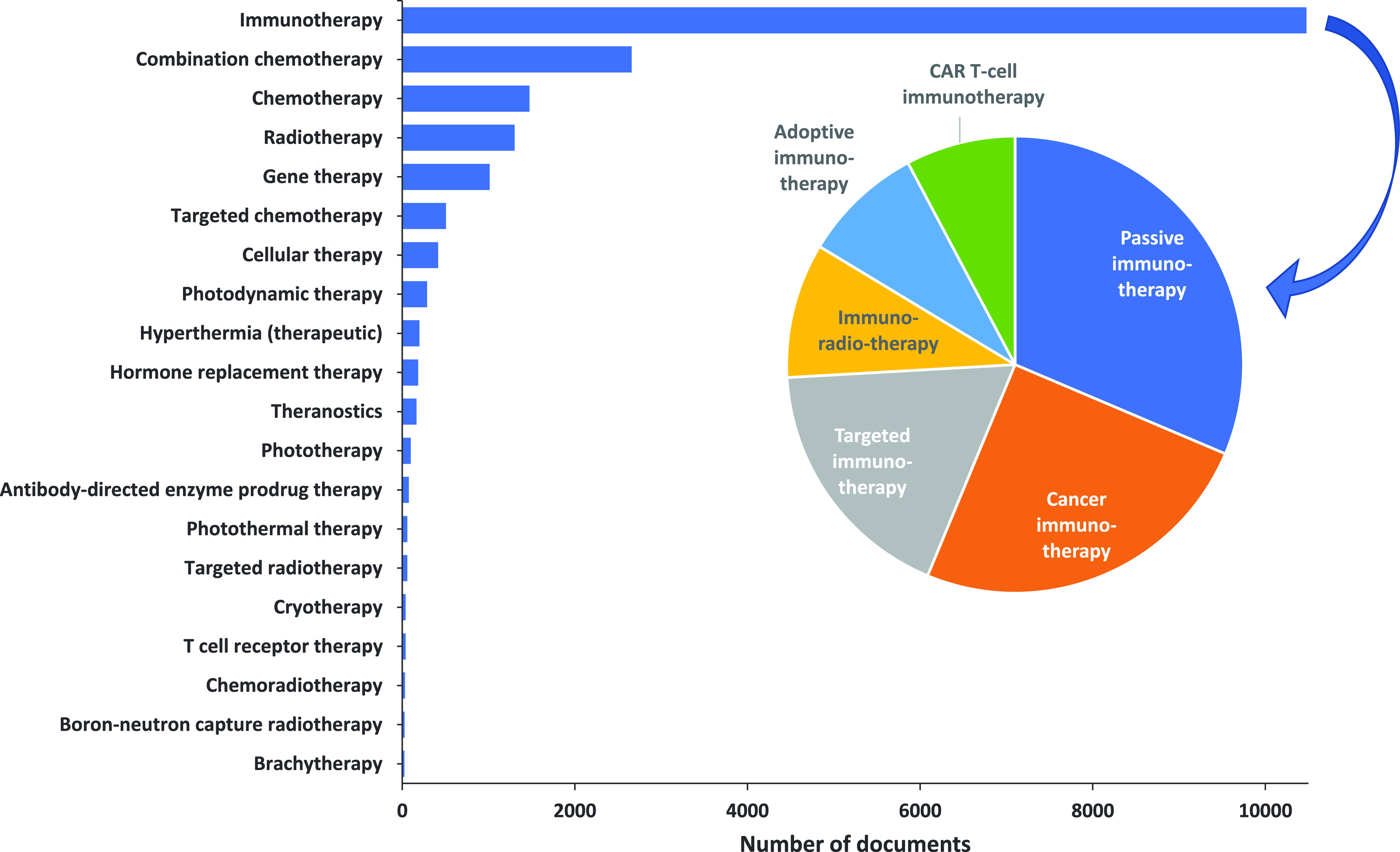

Figure 10 presents the number of ADC-related documents in the CAS Collection concerning various types of therapies. Immunotherapy understandably accounts for the highest number of documents. Indeed, a sound biological rationale supports the research into combining ADCs with immunotherapy to overcome the incidence of resistance and improve patient outcomes.275 Most immunotherapy-related papers involve passive immunotherapy (Figure 10, inset pie chart). Passive immunotherapy agents produce rapid antitumor responses by direct administration of immune-cell factors, such as cytokines or antibodies. With passive immunotherapy, continued dosing may be required for a prolonged response since immune system memory is not engaged.276,277

Figure 10.

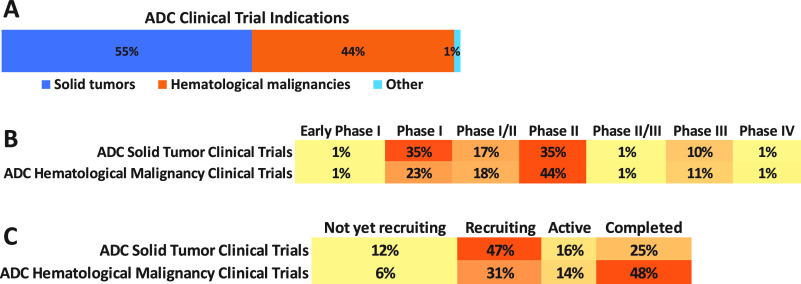

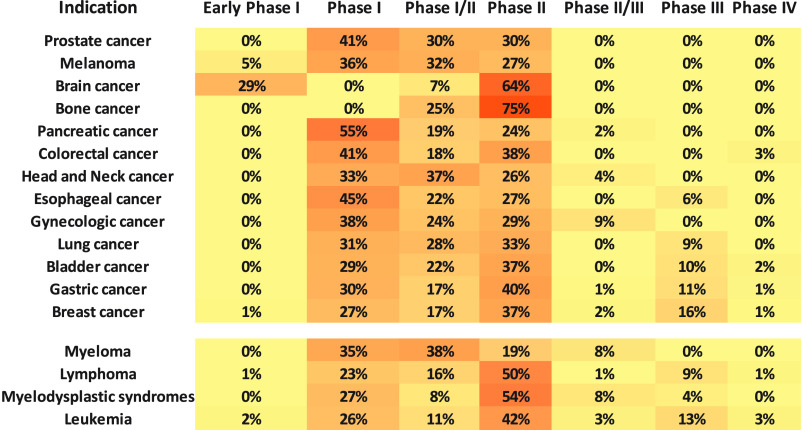

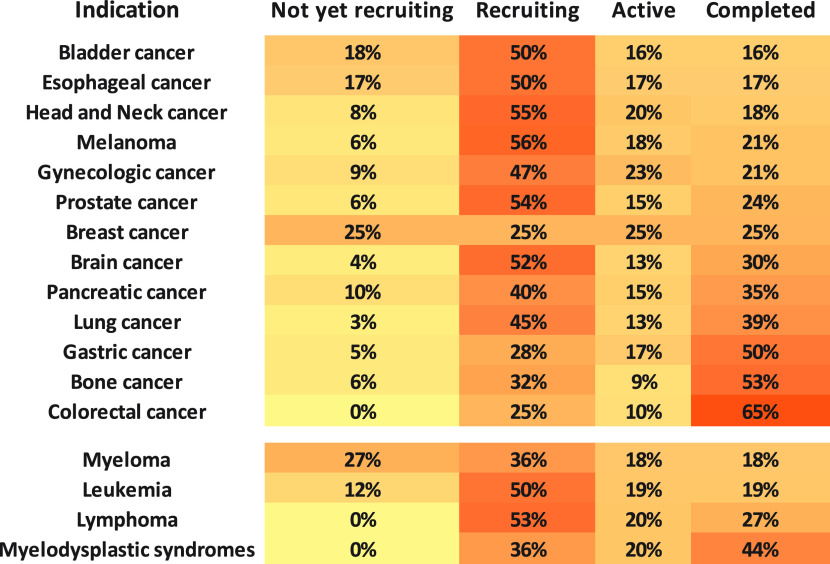

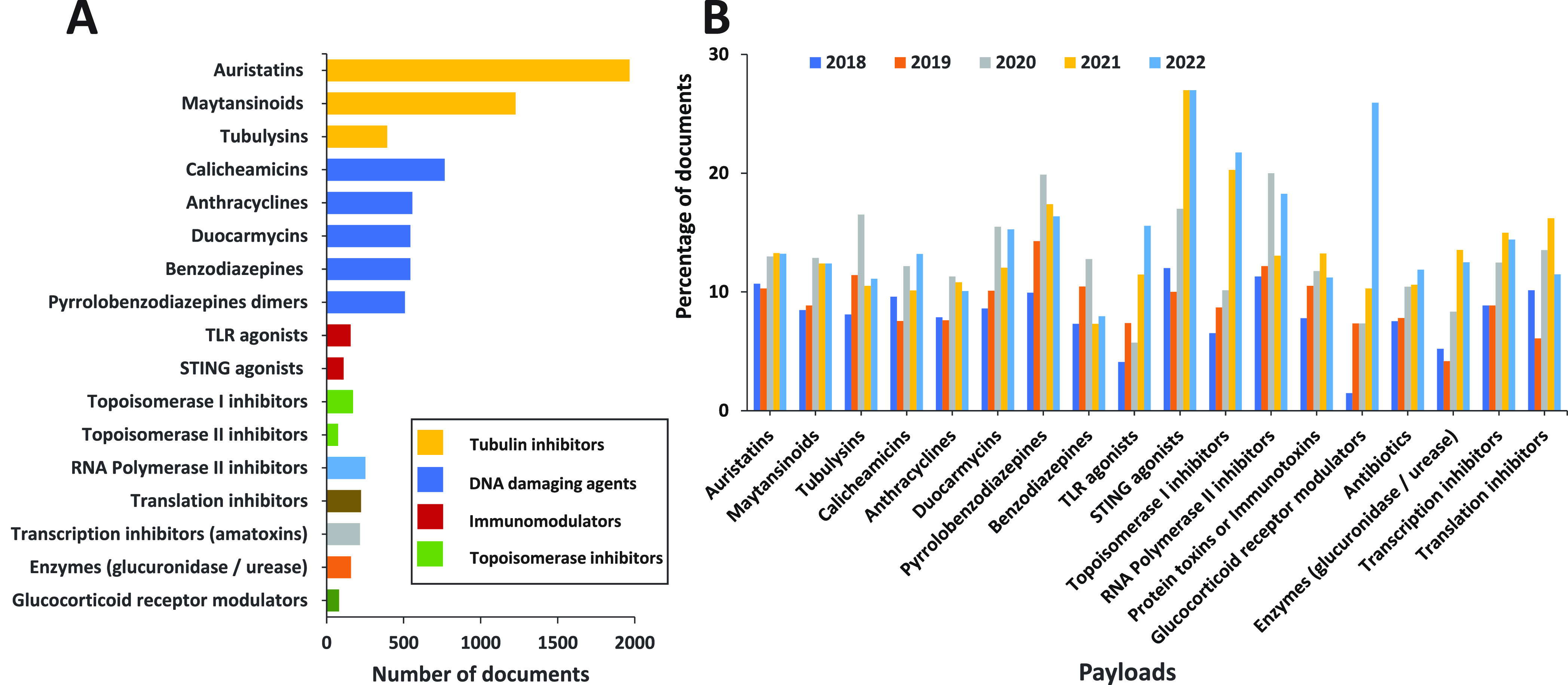

Therapies explored in the ADC-related publications.