Abstract

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), previously called metabolic nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, is the most prevalent chronic liver disease worldwide. The multi-factorial nature of MAFLD severity is delineated through an intricate composite analysis of the grade of activity in concert with the stage of fibrosis. Despite the preeminence of liver biopsy as the diagnostic and staging reference standard, its invasive nature, pronounced interobserver variability, and potential for deleterious effects (encompassing pain, infection, and even fatality) underscore the need for viable alternatives. We reviewed computed tomography (CT)-based methods for hepatic steatosis quantification (liver-to-spleen ratio; single-energy “quantitative” CT; dual-energy CT; deep learning-based methods; photon-counting CT) and hepatic fibrosis staging (morphology-based CT methods; contrast-enhanced CT biomarkers; dedicated postprocessing methods including liver surface nodularity, liver segmental volume ratio, texture analysis, deep learning methods, and radiomics). For dual-energy and photon-counting CT, the role of virtual non-contrast images and material decomposition is illustrated. For contrast-enhanced CT, normalized iodine concentration and extracellular volume fraction are explained. The applicability and salience of these approaches for clinical diagnosis and quantification of MAFLD are discussed.

Relevance statement

CT offers a variety of methods for the assessment of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease by quantifying steatosis and staging fibrosis.

Key points

• MAFLD is the most prevalent chronic liver disease worldwide and is rapidly increasing.

• Both hardware and software CT advances with high potential for MAFLD assessment have been observed in the last two decades.

• Effective estimate of liver steatosis and staging of liver fibrosis can be possible through CT.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords: Biomarkers, Fatty liver, Liver cirrhosis, Liver diseases, Tomography (x-ray computed)

Background

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD), previously called metabolic nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD, is a major risk factor for chronic liver disease, which affects approximately a quarter of the population worldwide [1, 2]. It is characterized by a pathological spectrum of severity with steatosis exceeding 5% in the hepatocytes, including alcohol-induced steatosis or concomitant secondary hepatic fat accumulation [1]. MAFLD can range from simple hepatocellular steatosis to steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis, which ultimately may lead to hepatocellular carcinoma, liver failure, and even death [3]. Furthermore, MAFLD is strongly linked to the occurrence and development of cardiovascular diseases [4].

MAFLD is mainly pathologically characterized by hepatocyte steatosis, hepatocyte ballooning degeneration, lobular inflammation, and fibrosis. The severity of MAFLD is best described by combining the stage of fibrosis with the grade of activity [1]. The degree of liver fibrosis is a crucial independent prognostic factor for mortality and morbidity due to liver disease in MAFLD patients. Therefore, an accurate assessment of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis is crucial in the diagnosis and treatment of MAFLD [5]. Liver biopsy has long been the reference standard for accurately evaluating steatosis and the degree of fibrosis [6]. Nevertheless, liver biopsy has some limitations, including sampling error, intra- and inter-observer variability, and invasiveness, which is associated with risks such as infection, pain, perforation of the organs near the liver, bleeding and, in rare cases, even death [7]. As such, it is essential to develop practical, robust, and cost-effective tests for the diagnosis, staging, and monitoring of MAFLD. Non-invasive modalities based on serum markers and imaging examinations, which circumvent the limitations of liver biopsy, have been developed for routine use in clinical practice [8, 9].

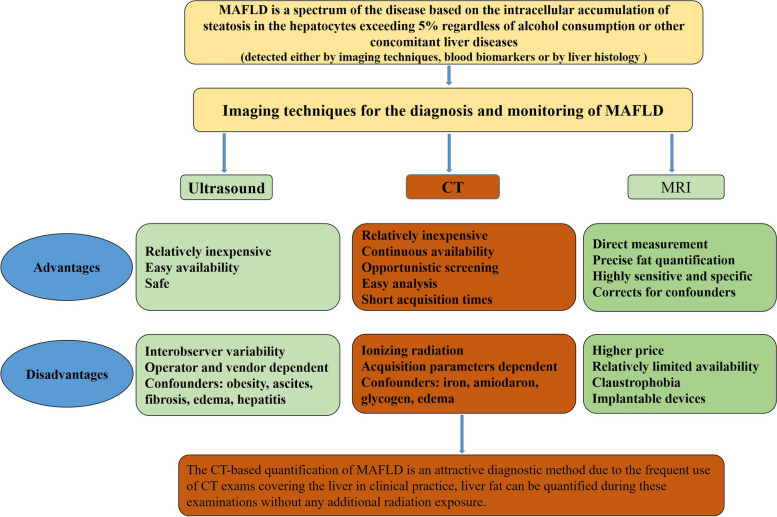

Imaging techniques have been used for the evaluation of steatosis and assessment of liver fibrosis severity in MAFLD for nearly two decades (Fig. 1). The current reference standards for non-invasive measurement of hepatic steatosis include magnetic resonance spectroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging-proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF) [10, 11]. However, their high cost and limited availability limit their widespread use in clinical practice. Ultrasound has been widely used to assess hepatic steatosis in clinical settings because of its low cost and availability. Emerging quantitative ultrasound elastographic techniques are also being developed and validated for the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis [12–14]. However, the accuracy of ultrasound-based methods is affected by various factors, such as the level of obesity and the serum alanine aminotransferase [15].

Fig. 1.

Comparison of ultrasound, CT, and MR for the diagnosis and monitoring of MAFLD. MAFLD Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease, CT Computed tomography, MRI Magnetic resonance imaging, US Ultrasound

CT can also measure liver fat [16, 17] and has been proven to be effective for detecting steatosis [17–21], but it exposes patients to ionizing radiation. Nonetheless, the CT-based quantification of MAFLD is an attractive diagnostic method as CT exams including the liver are common in clinical practice and it can be performed to quantify liver fat without additional radiation exposure. Furthermore, CT-based imaging biomarkers are increasingly used to diagnose and stage hepatic fibrosis [22–26], as they can be retrieved quantitatively, retrospectively, and rapidly using automated systems [24, 25]. Hence, CT liver fat measurement could be an effective method for the screening and diagnosis of MAFLD. This article reviews recent studies on CT techniques for hepatic steatosis quantification and CT-based tools for staging hepatic fibrosis and discusses their practical application in routine clinical diagnosis and quantification of MAFLD.

Estimation of liver steatosis

The traditional methods of conventional CT diagnosis of hepatic steatosis are based on liver Hounsfield units (HU) difference between liver and spleen, typically the liver-to-spleen ratio. These methods classify steatosis as normal, mild, moderate, or severe [19, 26–29]. HU is a unit of measurement used to measure the density of a local tissue or organ in the body as seen in CT scan. HU can be calculated using the following formula:

where μ is the CT linear attenuation coefficient and μair is almost zero and can be ignored

However, these methods merely provide a qualitative or semi-quantitative assessment of liver fat content and have been deemed accurate for moderate-to-severe steatosis but insensitive to mild steatosis [21]. Additionally, the outcomes are susceptible to variations in scanning conditions, including different tube voltages and usage of CT scanners from various manufacturers [30]. Furthermore, these evaluation methods cannot detect early stages of liver fibrosis based on fatty liver. Recently, various quantitative and reliable technologies based on CT have been developed and validated for evaluating the presence of steatosis and have high accuracy than the traditional methods of conventional CT. We summarized the CT-based technologies for quantitative evaluation of hepatic steatosis in Table 1, along with several representative studies presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Quantitative evaluation of hepatic steatosis using computed tomography

| CT-based tools | Principles | Acquisition methods |

|---|---|---|

| Deep learning | Automated algorithms for liver segmentation and analysis | All voxels designated as liver by the segmentation algorithm were analyzed, and the mean and median HU were computed |

| Quantitative CT | Using a scanner with a five-rod calibration phantom with an aqueous K2HPO4 bone density standard placed beneath the participants |

CTFF = (HUlean -HUliuer)/(HUlean—HUfat) HUliver is the measurement in Hounsfield units in the liver HUlean is the value in Hounsfield units for fat-free liver tissue HUfat is the value for 100% fat |

| Dual-energy CT | It provides information about tissue composition | VNC and iodine maps; TNC images; MMD algorithm |

| Deep learning | Automated algorithms for liver segmentation and analysis | All voxels designated as liver by the segmentation algorithm were analyzed, and the mean and median HU were computed |

| Photon-counting CT | It is able to detect and weight individual photons based on their energies | TNC and VNC images |

CT Computed tomography, CTFF CT fat fraction, HU Hounsfield units, MMD Multi-material decomposition, TNC True non-contrast, VNC Virtual non-contrast

Table 2.

Summary of CT studies for quantitative evaluation of hepatic steatosis

| First author [Reference] | Number of patients | Methods | Reference standard | AUROC or positive and negative predictive value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pickhardt [31] | 1,204 | Deep learning | MR-PDFF |

Steatosis ≥ 5%: 0.669 Steatosis ≥ 10%: 0.854 Steatosis ≥ 15%: 0.962 |

Steatosis ≥ 5%: 34.0% Steatosis ≥ 15%:75.9% | Steatosis ≥ 5%: 94.2% Steatosis ≥ 10%: 95.7% |

| Guo [16] | 400 | QCT | MR-PDFF |

Steatosis ≥ 5%: 0.87 Steatosis ≥ 14%: 0.99 |

Steatosis ≥ 5%:75.9% Steatosis ≥ 14%:84.8% |

Steatosis ≥ 5%: 83.3% Steatosis ≥ 14%: 98.4% |

| Hyodo [32] | 33 | DECT FVF | Histologic | FVF discrimination between histologic grade 0 and grades 1–3: 0.88 | Cut-off 4.6% for FVF: 82% | Cut-off 4.6% for FVF: 100% |

| Cao [33] | 50 | DECT MMD | Pathological | FVF correlated well with the pathological grades: 0.92 | 89.2% | 100% |

| Zhang [34] | 128 | DECT VNC | MR-PDFF | Steatosis > 6%: 0.834 and 0.872 in the right and left lobe | 57%/93.9% (right) | 67.9%/90% (left) |

| Niehoff [35] | 140 | PCD-CT VNC | Previous reported cut-off values for diagnosing hepatic steatosis (CT (L) ≤ 40 HU, CT (L-S) ≤ -10 HU, CT (L/S) ≤ 0.8 |

PPV and NPV for the detection of hepatic steatosis: 30% and 99.5% When adjusting cut-off values: 41% and 99.6% |

PPV and NPV: 94% When adjusting cut-off values: 94% |

PPV and NPV: 87% When adjusting cut-off values: 92% |

AUROC Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, DECT Dual-energy computed tomography, FVF Fat volume fraction, HU Hounsfield units, MMD Multi-material decomposition, MR-PDFF Magnetic resonance imaging-derived proton density fat fraction, NPV Negative predictive value, PPV Positive predictive values, QCT Quantitative CT, VNC Virtual non-contrast

Single-energy “quantitative” CT (QCT)

This technique was initially developed to measure bone mineral density [36]. QCT converts HU measurements into tissue densities by scanning a phantom with standards corresponding to the known density of bone and soft tissue [37]. Using QCT phantom, which includes water and fat standards, CT HU can be used to estimate tissue fat content, as adiposity negatively correlated with decreasing HU. In a study, a 120-kVp QCT scan of the liver was used to measure the fat content. Single-energy QCT-derived percentage of liver fat content was calculated using the following equation [37]:

Compared with traditional semiquantitative CT approaches, QCT can directly measure liver fat content and the calibration phantom can be used for multi-center studies. QCT significantly decreases the variability in HU measurements due to factors such as x-ray filtration, kVp, patient size, and splenic HU variation.

Peripheral QCT has been used in small animal models to assess body and liver fat [38]. Xu et al. [39] verified this method by comparing QCT liver fat measurements in goose liver samples with those obtained from biochemical analysis and chemical shift-encoded MRI. Guo et al. [16] validated the accuracy of QCT in measuring hepatic steatosis content using chemical shift-encoded MRI-PDFF as a standard in a large prospective cohort of healthy individuals. Furthermore, in a subsequent study, the researchers compared the prevalence of hepatic steatosis among Chinese and American cohorts using QCT measurements and found a strong correlation between the QCT liver fat measurement and MRI-PDFF determined using the mDixon Quant software [40]. Those studies collectively demonstrated the potential of quantitative computed tomography (QCT) as a reliable and accurate method for hepatic steatosis quantification. The findings underscore its usefulness in noninvasively assessing liver fat content in various cohorts. QCT holds promise as a valuable tool in clinical and research settings for hepatic steatosis evaluation. Further investigations and standardized protocols will aid in its widespread adoption and integration into routine clinical practice.

Dual-energy CT (DECT)

This is a qualitative and quantitative modality that obtains multi-material decomposition based on the attenuation measurements of x-rays at multiple diverse energies to differentiate and quantify the composition of the target [41]. Over the past decade, DECT has been increasingly employed for quantifying hepatic steatosis in phantom, animal, and clinical studies and showing promise over conventional CT imaging due to its ability to accurately quantify fat content [42–44].

However, Artz et al. [45] reported that the fat (water) content measurements strongly correlated with triglycerides in a phantom but not as well in vivo. Additionally, there have been differing opinions on the superiority of DECT over conventional single-energy CT and contrast-enhanced DECT for quantitatively assessing liver steatosis [18, 46]. Despite these variations, several principal studies have demonstrated the accuracy and reproducibility of DECT for quantitative assessment of liver fat, making it suitable for clinical use [32, 33, 47]. Zhang et al. [34] demonstrated that attenuation at virtual non-contrast (VNC) images of DECT had a moderate correlation with liver fat content and > 90% specificity for diagnosis attenuation at virtual non-contrast (VNC) images of DECT had a moderate correlation with liver fat content and > 90% specificity for diagnosis in fatty liver. In another research by Molwitz et al. [48] developed a fat quantification method based on dual-layer detector-based spectral, a detector-based DECT scanner, which demonstrated strong agreement with MRI techniques for patient liver and muscle.

By focusing on these principal studies, we can better understand the strengths and limitations of DECT in quantifying liver fat and appreciate its potential clinical utility. Contrast-enhanced DECT demonstrates high specificity in evaluating hepatic steatosis through VNC attenuation of the liver, making it a promising tool for the early and incidental detection of fatty liver disease. However, hepatic iron deposition might be the most significant influencing factor for DECT in the quantitative assessment of liver steatosis. The potential for future application of an iron-specific multi-material decomposition algorithm in DECT may enable quantitative assessment of liver steatosis while effectively correcting for the influences of iron and iodine in the liver.

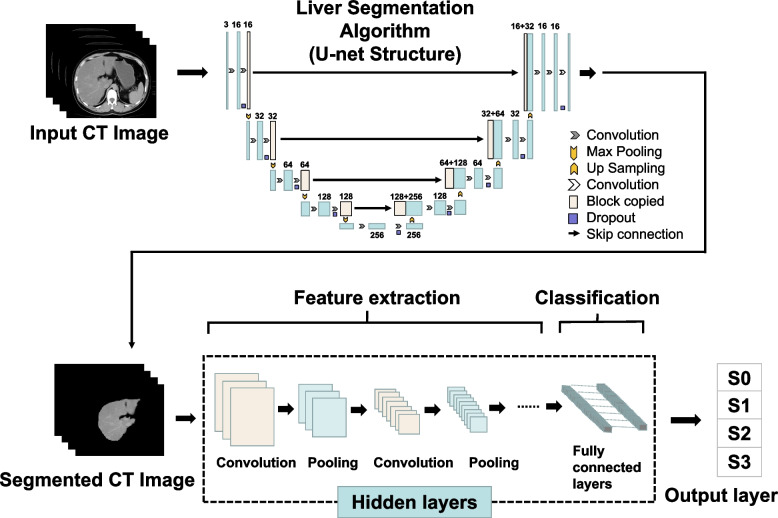

Deep learning (DL)-based methods

The application of artificial intelligence, in particular machine learning, has improved the accuracy of MAFLD diagnostic techniques. DL is a branch of machine learning commonly using convolutional neural networks. In Fig. 2, a flowchart of DL methods for liver assessment, which includes three layers is shown: input, hidden, and output. The input liver image is automatically delineated by the U-net structure. The hidden layers perform convolution and pooling of images, which are then fed to the fully connected layers. To generate high-dimensional manageable features, convolution and pooling of input images are repeated before feeding analyzed features of input imaged into fully connected layers for the classification task. Finally, probabilities for the classes are returned by the output layer. The loss function was calculated as follows:

where represents the predicted image and denotes the corresponding ground truth; represents the number of classes; represents the number of elements in or ’s first two dimensions; and represents the weighting factor for each class. The Dice coefficient is calculated using the following formula:

where and represent the predicted image and ground truth of each class, respectively ( = 1, 2). For each class, Jaccard’s index is calculated as follows:

Fig. 2.

Flowchart of deep learning for fatty liver. CT Computed tomography

Several studies have evaluated the performance of DL-based CT in liver fat quantification for MAFLD assessment in recent years. Kullberg et al. [49] used DL to analyze CT data to develop and validate an automated image-processing technique for analyzing body composition, including liver fat. Graffy et al. [25] proposed an automated liver segmentation tool based on deep learning was validated by retrospectively quantifying liver fat in 9,552 consecutive patients. In other studies, DL volumetric liver segmentation algorithm was used to evaluate liver fat based on contrast-enhanced CT images, which achieved high accuracy as an objective tool for assessing hepatic steatosis [31]. However, as this method does not exclude liver vessels, which have a higher HU value, it may overestimate liver attenuation. To reduce the vessel effects, Huo et al. [50] proposed a method that combines deep learning and morphological operations for accurate estimation the liver attenuation in peripheral regions of interest. Overall, these studies show the potential of deep learning technology for segmentation, quantification, and standardization of diagnosis in patients with MAFLD. In the future, this fully automated CT tool may be used in investigations with larger retrospective cohorts since it provides both rapid and objective assessment.

Photon-counting CT (PCCT)

In 2021, the first clinical PCCT scanner using a photon-counting detector with quantum technology to enhance the capability of spectral imaging, was introduced, taking CT technology to the next level. This has enabled PCCT technology to be used for true multi-energy CT scanning, as demonstrated by several preclinical and clinical studies [51, 52]. PCCT is an evolution in CT data collection methods within the realm of energy. It can produce material-specific or virtual monoenergetic images from CT data similar to DECT. Compared with conventional CT detectors, photon-counting detectors can detect and measure single photons and their energy because they are composed of one thick layer of semiconductor material [53, 54]. In addition, in contrast to DECT, PCCT has the potential to improve material decomposition, especially materials with K-edges in the diagnostic energy range [55]. It has been demonstrated that PCCT can accurately measure calcium, gadolinium, and iodine concentrations in phantoms [56, 57].

PCCT systems are currently under preclinical testing, mostly using phantoms, animal models, ex vivo tissue or cadavers. Some authors speculate that due to their improved spectral separation capacity, PCCT could improve the selective recognition and removal of iodine from contrast-enhanced CT images, obtaining more realistic VNC images [53, 58]. Currently, however, density measurements obtained with the first clinical PCCT have a limited diagnostic value. In one study, the liver parenchyma was found to differ by approximately 11 HU between VNC and true non-contrast images [59]. However, the accuracy of PCCT very likely will improve in the coming years. One research established that PCCT could be used to reconstruct phantom and patient VNC images of the liver with accurate attenuation value and without the effects of dose, base material’s attenuation, and liver iodine content [60]. Additionally, a recent research by Niehoff et al. [35] showed that using the spectral datasets obtained from the first clinical PCCT scanner good VNC images could be reconstructed for hepatic steatosis assessment, and all indices showed high sensitivity and specificity even after changing the cut-off values. Despite being the latest technology for CT imaging, PCCT can benefit from further technical advancement to improve its capability to detect and quantify hepatic steatosis.

Staging of liver fibrosis

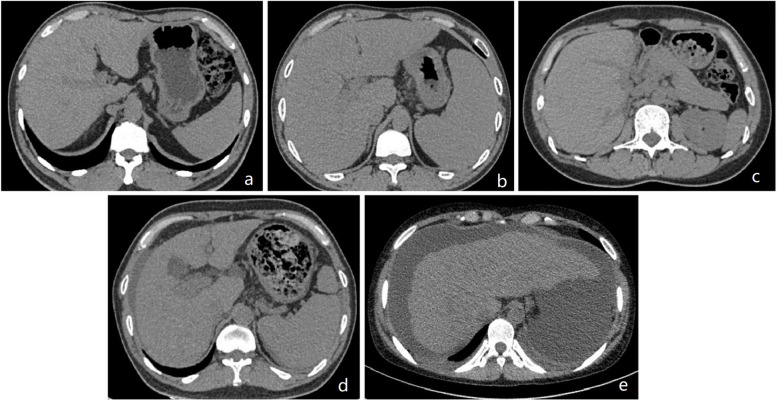

As the degree of hepatic fibrosis is strongly associated with both carcinogenesis and prognosis, a precise assessment is essential for determining its clinical course and prognosis of the patient. For patients with MAFLD, non-invasive diagnosis and staging of liver fibrosis is crucial for assessing disease progression. Techniques such as elastography measure the velocity of the ‘sheer wave’ or tissue displacement due to liver fibrosis to quantify how the organ “stiffers” based on ultrasonic or physical impulse. Ultrasound-based modalities, including vibration-controlled transient elastography, two-dimensional shear wave elastograghy, point shear wave elastography, and magnetic resonance elastography, are advanced elastography technologies for evaluating liver fibrosis. However, increasingly, CT biomarkers are being used to detect and stage hepatic fibrosis (Fig. 3). Current CT methods for detecting liver fibrosis on abdominal CT rely on morphology-based score, contrast-enhanced imaging biomarkers, and post-processing methods. We summarized the CT-based technologies for estimation of hepatic fibrosis (Table 3) and representative studies (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography findings of liver fibrosis at each stage. a Fibrosis grade 0 (F0): normal liver. b Fibrosis grade 1 (F1): no significant change in liver volume and increased volume of spleen. c Fibrosis grade 2 (F2): the liver volume is slightly reduced. d Fibrosis grade 3 (F3): portal vein thickening, spleen enlargement, and minimal ascites are visible. e Fibrosis grade 4 (F4): liver with an irregular shape and ascites are visible

Table 3.

CT methods assessing hepatic fibrosis

| Approach | Acronym | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Morphology-based score | CRL-R | Caudate-right-lobe ratio = caudate lobe diameter/right lobe diameter |

| LIMV-FS | Liver imaging morphology and vein diameter fibrosis score = liver vein diameter/caudate-right-lobe ratio | |

| LIMA-FS | Liver imaging morphology and attenuation fibrosis score = caudate-right-lobe ratio × liver vein to cava attenuation | |

| LIMVA-FS | Liver imaging morphology, vein diameter and attenuation fibrosis score = liver vein diameter/caudate-right-lobe ratio × liver vein to cava attenuation | |

| Contrast-enhanced biomarkers | NIC |

Normalized iodine concentration = iodine concentration liver/ iodine concentration aorta The ICratio was defined as ICAP/ ICPVP, where ICAP and ICPVP denoted iodine concentrations during AP and PVP, respectively |

| ECV |

Hepatic extracellular volume—Hounsfield units (%) = △Hounsfield units liver × (100–1-hematocrit (%))/△Hounsfield units aorta △HUlive indicates the difference in HUs between the precontrast and equilibrium phase |

|

| Postprocessing methods | LSN | A semiautomated postprocessing software |

| LSVR | A dedicated computed tomography software tool | |

| TA | A commercially available texture analysis research software platform | |

| DLS |

The steps for deep learning system: Input CT images Liver segmentation algorithm Segmented liver images Liver fibrosis staging algorithm Output |

|

| Radiomics |

The steps for radiomics: Importing CT images ROI segmentation Featre extraction Feature selection Clinical application and analysis |

AP Arterial phase, CRL-R Caudate-right-lobe ratio, CLD Caudate lobe diameter, TA Texture analysis, DLS Deep learning system, ECV Hepatic extracellular volume, HU Hounsfield units, Hct 1-hematocrit, IC Iodine concentration, LSN Liver surface nodularity, LSVR Regional changes in hepatic volume, LIMV-FS Liver imaging morphology and vein diameter fibrosis score, LVD Liver vein diameter, LIMA-FS Liver imaging morphology and attenuation fibrosis score, LVCA Liver vein to cava attenuation, LIMVA-FS Liver imaging morphology, vein diameter, and attenuation fibrosis score, NIC Normalized iodine concentration, PVP Portal venous phase, RLD Right lobe diameter, ROI Circular regions of interest

Table 4.

Summary of CT studies assessing of hepatic fibrosis

| First author [reference] | Number of patients | Methods | Reference standard | AUROC or positive and negative predictive value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awaya [61] | 236 | Morphology-based score: CR–L | Pathologically proved cirrhosis | 0.797 | 71.7% | 77.4% |

| Huber [62] | 148 | Morphology-based score: LIMV-FS | Histologically prove |

AUC for cirrhosis is 0.64 AUC for cirrhosis is 0.82 |

kd/crl-r score ≤ 19.6 for cirrhosis: 88% ld/crl-r score ≤ 23.9 for fibrosis: 83% |

kd/crl-r score ≤ 19.688% for cirrhosis: 82% ld/crl-r score ≤ 23.9 for fibrosis: 76% |

| Obmann [63] | 148 | Morphology-based score: LIMVA-FS | MR elastography |

Any degree of liver fibrosis: 0.84 Significant liver fibrosis: 0.97 |

Any degree of liver fibrosis: 67% Significant liver fibrosis: 95% |

Any degree of liver fibrosis: 88% Significant liver fibrosis: 85% |

| Lv [64] | 81 | Contrast-enhanced CT-based imaging biomarkers: NIC | Liver biopsy | ROC of NIC during the PVP: (0.84) and ICratio (0.65) |

NIC: 95% ICratio: 79% Combination of these two parameters: 77% |

NIC: 61% ICratio: 49% Combination of these two parameters: 87% |

| Sofue [65] | 47 | NIC | Liver biopsy | Each liver fibrosis score (> / = F1–F4): 0.795 to 0855 |

F0 versus F1–4: 75% F0–1 versus F2–4: 56.6% F0–2 versus F3–4: 57.2% F0–3 versus F4:60.8% |

F0 versus F1–4: 81.4% F0-1 versus F2–4: 79.5% F0-2 versus F3–4: 81.9% F0-3 versus F4: 85.5% |

| Marri [66] | 107 | NIC of the right lobe of the liver (RNIC) | Liver biopsy | Metavir fibrosis stage (ranging from F0 to F4): 0.86 to 0.96 | F1–F4 fibrosis: 83–93% | F1-F4 fibrosis: 81–87% |

| Yoon [67] | 141 | fECV | Liver biopsy |

Normal or F0–F1 from F2–F4: 0.832 F4: 0.739 |

Normal or F0–F1 from F2–F4: 87.5% F4: 73.3% |

Normal or F0–F1 from F2–F4: 71.0% F4: 62.7% |

| Shinagawa [68] | 41 | ECV-newSub | Liver biopsy | liver fibrosis grades: 0.71 | Discrimination of advanced stage (F3–4) from early stage (F0–2): 100% | Discrimination of advanced stage (F3–4) from early stage (F0–2): 100% |

| Ito [69] | 52 | ECV | Surgically resected or percutaneously biopsied |

ECVI-B IVC cut-off value of 26.4%, discrimination of advanced stage (F3–4) from early stage (F0–2: AUC: 0.95 positive predictive value: 93% negative predictive value: 69% |

ECVI-B IVC cut-off value of 26.4%, discrimination of advanced stage (F3–4) from early stage (F0–2: 78% | ECVI-B IVC cut-off value of 26.4%, discrimination of advanced stage (F3–4) from early stage (F0–2: 90% |

| Yoon [70] | 177 | ECV-iodine | Liver resection or biopsy |

Differentiating F0–1 from F2–4: 0.82 Detecting F4: 0.81 |

Differentiating F0–1 from F2–4: 82.8% Detecting F4: 74.7% |

Differentiating F0–1 from F24: 78.6% Detecting F4: 72.3% |

| Smith [71] | 94 | LSN scores | Liver biopsy | Differentiating cirrhotic from noncirrhotic livers: 0.910–0.929 | Range: 84–88% | Range: 87–92% |

| Pickhardt [72] | 367 | LSN scores | Liver biopsy | F2, F3, F4: 0.902, 0.932, and 0.959, respectively | 80.2%; 80.0%; 97.9% | 80.0%; 84.2%; 84.8% |

| Furusato [73] | 312 | LSVR | Liver biopsy | Distinguishing cirrhosis from normal: 0.916 |

LSVR ≥ 0.26: 95.4% LSVR ≥ 0.28: 94.4% LSVR ≥ 0.30: 88.0% LSVR ≥ 0.35: 81.5% LSVR ≥ 040: 68.5% |

LSVR ≥ 0.26: 51.5% LSVR ≥ 0.28: 63.2% LSVR ≥ 0.30: 71.1% LSVR ≥ 0.26: 88.7% LSVR ≥ 0.40: 96.1% |

| Pickhardt [74] | 624 | LSVR | Liver biopsy |

F3–F4 versus F0–F2: 0.880 F3–F4 versus F0–F2: 0.854 |

F3–F4 versus F0–F2: 72.2% F3-F4 versus F0–F2: 68.3% |

F3–F4 versus F0–F2: 88.1% F3–F4 versus F0–F2: 87.9% |

| Lubner [75] | 289 | TA | Liver biopsy |

F0 versus F1–4: 0.78 For significant fibrosis (> / = F2): 0.71–0.73 For cirrhosis (> / = F4): 0.86 and 0.87 |

F0 versus F1–4: 74% For significant fibrosis (> / = F2): 71% For cirrhosis (> / = F4): 84% |

F0 versus F1–4: 74% For significant fibrosis (> / = F2): 68% For cirrhosis (> / = F4): 75% |

| Yasaka [76] | 286 | DCNN | Biopsy specimen or surgical specimens |

fibrosis (> / = F2): 0.74 fibrosis (> / = F3): 0.76 fibrosis (> / = F3): 0.73 |

fibrosis (> / = F2): 64% fibrosis (> / = F3): 66% fibrosis (> / = F3): 62% |

fibrosis (> / = F2): 85% fibrosis (> / = F3): 85% fibrosis (> / = F3): 84% |

| Yin [77] | 252 | LFS network | Liver biopsy |

F2–F4: 0.92 F3–F4: 0.89 F4: 0.88 |

F2–F4: 83.0% F3–F4: 79.5% F4:75.1% |

F2–F4: 91.7% F3–F4: 88.2% F4: 86.5% |

| Wang [78] | 332 | Radiomic | Liver pathologic examination |

F2–F4: 0.904 F3-F4: 0.911 F4: 0.844 |

F2–F4: 92.1% F3–F4: 83.6% F4: 60.7% |

F2–F4: 76.7% F3–F4: 89.3% F4: 95.6% |

| Yin [79] | 252 | Radiomic | Histologically proven |

F2–F4: 0.92 F3–F4: 0.81 F4: 0.85 |

Average accuracy rates: F2–F4: 88% F3–F4: 82% F4: 86% |

|

AUC Area under the curve, CT Computed tomography, C/RL Caudate-right lobe ratio, TA Texture analysis, DCNN Deep convolutional neural network, ECV-newSub ECV obtained from new algorithm data, ECV Hepatic extracellular volume, fECV Hepatic extracellular volume fractions, ICratio Iodine concentration ratio, LIMV-FS Liver imaging morphology and vein diameter fibrosis score, LIMVA-FS Liver imaging morphology, vein diameter and attenuation fibrosis score, LFS Liver fibrosis staging, LSN Liver surface nodularity, LSVR Regional changes in hepatic volume, NIC Normalized iodine concentration, PVP Portal venous phase, ROC Circular regions of interest

Morphology-based methods

Quantitative metrics for assessing hepatic fibrosis based on abdominal CT scans are reproducible, require no postprocessing of the images, and can distinguish cirrhotic livers from normal livers with high accuracy. They include caudate-right-lobe ratio (CRL-R) [61], the liver imaging morphology and vein diameter fibrosis score (LIMV-FS) [62], liver imaging morphology and attenuation fibrosis score (LIMA-FS), and liver imaging morphology and vein diameter and attenuation fibrosis score (LIMVA-FS) [63]. And those studies showed that those morphology-based assessments of CT indicators have clinical utility in evaluating the in patients with chronic liver disease, even in the pre-cirrhotic stages of liver fibrosis [61–63]. Notably, enhancement of these scores (LIMVA-FS and LIMA-FS) were better that purely morphology-based CRL-R score [63]. In addition, these quantifiable metrics can be calculated retrospectively on axis planes without time-consuming post-processing and those methods may be easily applied to retrospective CT data analysis. Nonetheless, such linear measurements of liver may not capture all complex changes underlying its morphology.

Contrast-enhanced biomarkers

CT has limited accuracy in quantifying hepatic fibrosis due to insufficient differences in mass attenuation coefficient between fibrous liver tissue and normal liver tissue. However, fibrosis can be indirectly measured using contrast media as a marker [80]. Markers such as normalized iodine concentration (NIC) and hepatic extracellular volume fraction (ECV) can individually estimate the degree of early hepatic fibrosis in animal and clinical studies. Compared with healthy liver, liver cirrhosis absorb different iodine contrast agents differently during the arterial phase and the venous phase.

NIC, computed as the ratio of liver and aorta contrast concentration during the venous phase, is utilized in DECT imaging to diagnose and stage liver cirrhosis [64–66, 81]. Lv et al. [64] analyzed 38 cirrhosis patients and 43 liver-healthy patients, finding that NIC during the venous phase and the iodine concentration ratio obtained from spectral CT can provide a high level of specificity and sensitivity for distinguishing healthy liver from cirrhotic liver, particularly class C cirrhotic liver. Sofue et al. [65] observed a correlation between NIC in the 3-min delayed DECT scans and severity of liver fibrosis (Spearman r = 0.65, p < 0.001). However, Marri et al. [66] reported a strong correlation between NIC concentrations in 5-min delayed DECT liver scans and histological forms of liver fibrosis. Based on the rationale that fibrotic areas exhibit a gradual contrast material accumulation, CT acquisition with a delay exceeding 3 min was expected to yield higher iodine concentrations in fibrotic livers. Despite the lack of consensus on the optimal minute for delayed NIC acquisition, NIC using DECT imaging provides a noninvasive method for staging liver fibrosis. The clinical application of DECT iodine measurements for liver fibrosis could be valuable in monitoring disease progression and treatment response, potentially reducing the necessity for liver biopsy.

ECV, which reflects the degree of hepatic fibrosis by measuring the enlarged extracellular space due to collagen fiber deposition, can be assessed during the equilibrium phase of contrast-enhanced CT [82]. The ECV of the liver tissue can be determined using contrast-enhanced CT during the equilibrium phase, when the contrast media has diffused from the intravascular to extravascular spaces to reach an equilibrium. At this contrast-enhanced CT's equilibrium phase, the contrast media is considered to be at equal concentration intravascularly and extravascularly. Consequently, the ECV fraction can be estimated with the following formula: (enhancement in the liver)/(enhancement in the aorta) × (1-hematocrit).

Several studies have validated ECV may act as a reliable biomarker of liver fibrosis [67–70, 83, 84]. Yoon et al. [70] even suggested that ECV is a more suitable parameter for assessing liver fibrosis than iodine density and effective atomic number maps, which are calculated solely based on iodine/water concentration without considering hematocrit levels. They also demonstrated that liver ECV estimated on the basis of HU values showed significant differences between fibrosis stages, but its diagnostic accuracy was lower compared with ECV calculated via iodine density. Despite these promising findings, 3 to 10 min or later delayed phase was used to achieve a consistent steady-state equilibrium condition for ECV measurement in the literature. Further studies are needed to determine the optimal delay time for ECV calculated in the equilibrium phase.

In summary, the use of NIC and ECV with DECT imaging provides valuable insights into hepatic fibrosis evaluation, offering noninvasive alternatives for staging liver fibrosis.

Postprocessing methods for assessing liver fibrosis

Postprocessing methods for assessing hepatic fibrosis based on CT include liver surface nodularity, liver segmental volume ratio, CT texture analysis (TA), deep learning system (DLS), and radiomics. A quantitative tool developed using a dedicated semiautomated CT software for calculating objective scores of liver surface nodularity was validated for staging hepatic fibrosis [71, 72, 85]. The process of determining the volume of the liver has been made easier by advanced visualization software tools that effectively segment the liver. Several studies showed that liver segmental volume ratio and total splenic volume, which measure CT-based hepatosplenic volumetric changes, can be used for non-invasive staging of liver fibrosis [73, 74]. TA determines the level of heterogeneity in a particular region of interest by analyzing the distribution of pixel and voxel-gray levels in an image based on histogram analysis [86]. Several studies have investigated the application of TA for the assessment of hepatic fibrosis on CT and found that TA parameters are feasible and useful biomarkers for assessing hepatic fibrosis [75, 87]. However, further research is needed to study and standardize TA methodology as TA metrics and software platforms differ widely.

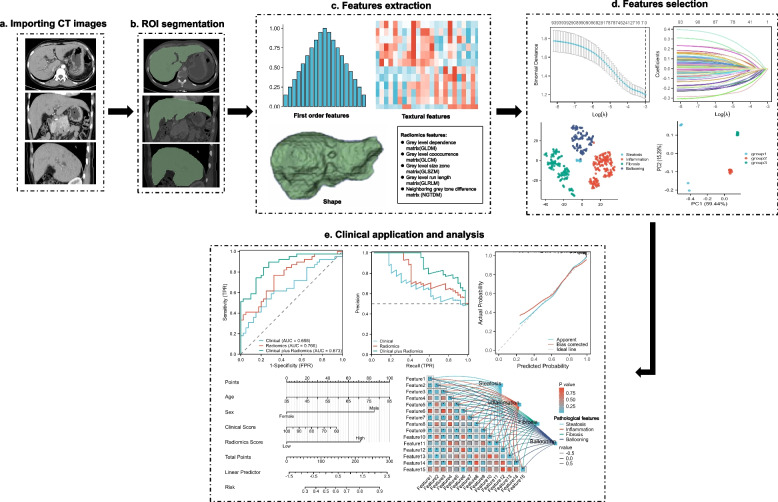

Recently, deep learning methods, specifically neural network with convolutions, have attracted interest as a tool for recognizing and interpreting images. The use of deep learning methods to stage liver fibrosis has been demonstrated in a few studies [24, 76, 77]. DLS provides a promising method for assessing liver fibrosis using CT scans and liver CT scans, which are widely available. Compared with DLS, radiomics analysis requires less data, and computational power is needed for training, as features are extracted from CT scans using manually designed algorithms instead of the raw image. A typical process of hepatic fibrosis evaluation using radiomics is shown in Fig. 4. Additionally, by analyzing radiomic features, radiomics analysis can identify and extract key symptoms that are most relevant to the model from the images, making CT-based radiomics a valuable diagnostic tool for staging liver fibrosis [78]. Another study revealed that incorporating splenic radiomic features and hepatic radiomic features based on CT can improve radiomics analysis for staging liver fibrosis [79].

Fig. 4.

Evaluation of hepatic fibrosis based on radiomics. a Importing CT images. b The ROI was manually delineated on CT images of the entire liver. c First-order statistics, textural features, wavelet or Laplacian of Gaussian transforms, and shape features were extracted. d The feature selection is performed using a least absolute shrinkage, selection operator and cluster analysis, and cluster analysis, etc. e Nomogram was used to integrate radiomic and clinical features. The performance of established models was evaluated by receiver operator characteristic curve and precision-recall curve, the correlation between pathological features and radiomic features could be also analyzed, etc. CT Computed tomography, ROI Region of interest

Although the multiple CT-based biomarkers have been demonstrated as reliable in evaluating liver fibrosis in various mixed and disease-specific cohorts of patients, these techniques are prone to many confounders, such as patient-related factors, operator expertise, technical variations, sampling errors, presence of other liver pathologies, variability in fibrosis distribution and so on. Ideally, hepatic fibrosis should be assessed using a multi-parametric approach that combines the most promising CT features, especially retrospective data acquisition, low cost, and optimal use of resources.

Conclusions

In summary, MAFLD affects millions of people worldwide, posing a significant burden on economies and healthcare systems. It has become routine clinical practice to assess hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in patients with MAFLD non-invasively. Various CT parameters can be used to identify and stratify the stage of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis with high accuracy. In addition, these methods are attractive due to not only their relationship with hepatic steatosis and fibrosis but also the ease of accessibility and ubiquity of CT technology in clinical settings. With continued improvements in new scanning technique and post-processing method, CT parameters are expected to become more accurate, precise, reproducible, affordable, and routinely applied to non-invasive assessment of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in MAFLD.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully thank all the participants at Guizhou Medical University; we are also thankful to StudyForBetter Team who contributed their best research spirits to this work.

Abbreviations

- CT

Computed tomography

- DECT

Dual-energy CT

- DL

Deep learning

- ECV

Extracellular volume

- HU

Hounsfield units

- MAFLD

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MRI-PDFF

MRI-derived proton density fat fraction

- NIC

Normalized iodine concentration

- PCCT

Photon-counting CT

- QCT

Quantitative CT

- TA

Texture analysis

- VNC

Virtual non-contrast

Authors’ contributions

All the authors participated in planning the study. Na Hu, Gang Yan, and Maowen Tang wrote the original draft preparation. Yuhui Wu, Fasong Song, Xing Xia reviewed and edited the manuscript. Lawrence Wing-Chi Chan and Pinggui Lei gave valuable medical insight and conceived the work. All the authors have read the manuscript and agreed to submit it.

Funding

This work was partially supported by Science and Technology Projects of Guizhou Province (NO. Qiankehejichu-ZK[2023]353, Qiankehejichu-ZK[2022]422), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81960338), and Funding for the Excellent Reserve Talents in the Discipline of Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University (gyfyxkyc-2023-13).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Na Hu, Gang Yan, and Maowen Tang have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Contributor Information

Lawrence Wing-Chi Chan, Email: wing.chi.chan@polyu.edu.hk.

Pinggui Lei, Email: pingguilei@foxmail.com.

References

- 1.Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: an international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nan Y, An J, Bao J, et al. The Chinese Society of Hepatology position statement on the redefinition of fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2021;75:454–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fazel Y, Koenig AB, Sayiner M, Goodman ZD, Younossi ZM. Epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2016;65:1017–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim D, Konyn P, Sandhu KK, et al. Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease is associated with increased all-cause mortality in the United States. J Hepatol. 2021;75:1284–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dulai PS, Singh S, Patel J et al (2017) Increased risk of mortality by fibrosis stage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology 65:1557–1565. 10.1002/hep.29085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–1321. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davison BA, Harrison SA, Cotter G, et al. Suboptimal reliability of liver biopsy evaluation has implications for randomized clinical trials. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1322–1332. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loomba R, Adams LA. Advances in non-invasive assessment of hepatic fibrosis. Gut. 2020;69:1343–1352. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ajmera V, Loomba R. Imaging biomarkers of NAFLD, NASH, and fibrosis. Mol Metab. 2021;50:101167. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2021.101167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caussy C, Alquiraish MH, Nguyen P, et al. Optimal threshold of controlled attenuation parameter with MRI-PDFF as the gold standard for the detection of hepatic steatosis. Hepatology. 2018;67:1348–1359. doi: 10.1002/hep.29639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferraioli G, Maiocchi L, Raciti MV et al (2019) Detection of liver steatosis with a novel ultrasound-based technique: a pilot study using MRI-derived proton density fat fraction as the gold standard. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 10:e00081. 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Tamaki N, Koizumi Y, Hirooka M, et al. Novel quantitative assessment system of liver steatosis using a newly developed attenuation measurement method. Hepatol Res. 2018;48:821–828. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bae JS, Lee DH, Lee JY, et al. Assessment of hepatic steatosis by using attenuation imaging: a quantitative, easy-to-perform ultrasound technique. Eur Radiol. 2019;29:6499–6507. doi: 10.1007/s00330-019-06272-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeon SK, Lee JM, Joo I. Clinical feasibility of quantitative ultrasound imaging for suspected hepatic steatosis: intra- and inter-examiner reliability and correlation with controlled attenuation parameter. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2021;47:438–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2020.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petta S, Wai-Sun Wong V, Bugianesi E et al (2019) Impact of obesity and alanine aminotransferase levels on the diagnostic accuracy for advanced liver fibrosis of noninvasive tools in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 114:916–928. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000153 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Guo Z, Blake GM, Li K, et al. Liver fat content measurement with quantitative CT validated against MRI proton density fat fraction: a prospective study of 400 healthy volunteers. Radiology. 2020;294:89–97. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019190467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickhardt PJ, Graffy PM, Reeder SB, Hernando D, Li K. Quantification of liver fat content with unenhanced MDCT: phantom and clinical correlation with MRI proton density fat fraction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018;211:W151–W157. doi: 10.2214/AJR.17.19391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer H, Pickhardt PJ, Kliewer MA, et al. Accuracy of liver fat quantification with advanced CT, MRI, and ultrasound techniques: prospective comparison with MR spectroscopy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2017;208:92–100. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hahn L, Reeder SB, Munoz del Rio A, Pickhardt PJ. Longitudinal changes in liver fat content in asymptomatic adults: hepatic attenuation on unenhanced CT as an imaging biomarker for steatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;205:1167–1172. doi: 10.2214/AJR.15.14724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SS, Park SH, Kim HJ, et al. Non-invasive assessment of hepatic steatosis: prospective comparison of the accuracy of imaging examinations. J Hepatol. 2010;52:579–585. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pickhardt PJ, Park SH, Hahn L, et al. Specificity of unenhanced CT for non-invasive diagnosis of hepatic steatosis: implications for the investigation of the natural history of incidental steatosis. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:1075–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2349-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno CC, Hemingway J, Johnson AC, et al. Changing abdominal imaging utilization patterns: perspectives from medicare beneficiaries over two decades. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13:894–903. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith-Bindman R, Kwan ML, Marlow EC, et al. Trends in use of medical imaging in US health care systems and in Ontario, Canada, 2000–2016. JAMA. 2019;322:843–856. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.11456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi KJ, Jang JK, Lee SS, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning system for staging liver fibrosis by using contrast agent-enhanced CT images in the liver. Radiology. 2018;289:688–697. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018180763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graffy PM, Sandfort V, Summers RM, Pickhardt PJ. Automated liver fat quantification at nonenhanced abdominal CT for population-based steatosis assessment. Radiology. 2019;293:334–342. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2019190512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeb I, Li D, Nasir K, et al. Computed tomography scans in the evaluation of fatty liver disease in a population based study: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Acad Radiol. 2012;19:811–818. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kodama Y, Ng CS, Wu TT, et al. Comparison of CT methods for determining the fat content of the liver. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188:1307–1312. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schwenzer NF, Springer F, Schraml C, et al. Non-invasive assessment and quantification of liver steatosis by ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance. J Hepatol. 2009;51:433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Wang C, Duanmu Y, et al. Comparison of CT and magnetic resonance mDIXON-Quant sequence in the diagnosis of mild hepatic steatosis. Br J Radiol. 2018;91:20170587. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20170587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cropp RJ, Seslija P, Tso D, Thakur Y. Scanner and kVp dependence of measured CT numbers in the ACR CT phantom. J Appl Clin Med Phys. 2013;14:4417. doi: 10.1120/jacmp.v14i6.4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickhardt PJ, Blake GM, Graffy PM, et al. Liver steatosis categorization on contrast-enhanced CT using a fully automated deep learning volumetric segmentation tool: evaluation in 1204 healthy adults using unenhanced CT as a reference standard. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;217:359–367. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.24415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hyodo T, Yada N, Hori M, et al. Multimaterial decomposition algorithm for the quantification of liver fat content by using fast-kilovolt-peak switching dual-energy CT: clinical evaluation. Radiology. 2017;283:108–118. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017160130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cao Q, Yan C, Han X, Wang Y, Zhao L (2022) Quantitative evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver in rat by material decomposition techniques using rapid-switching dual energy CT. Acad Radiol 29:e91-e97. 10.1016/j.acra.2021.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Zhang PP, Choi HH, Ohliger MA. Detection of fatty liver using virtual non-contrast dual-energy CT. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2022;47:2046–2056. doi: 10.1007/s00261-022-03482-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Niehoff JH, Woeltjen MM, Saeed S, et al. Assessment of hepatic steatosis based on virtual non-contrast computed tomography: Initial experiences with a photon counting scanner approved for clinical use. Eur J Radiol. 2022;149:110185. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2022.110185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engelke K. Quantitative computed tomography-current status and new developments. J Clin Densitom. 2017;20:309–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jocd.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng X, Blake GM, Brown JK et al (2017) The measurement of liver fat from single-energy quantitative computed tomography scans. Quant Imaging Med Surg 7:281–291. 10.21037/qims.2017.05.06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Nagy TR, Johnson MS. Measurement of body and liver fat in small animals using peripheral quantitative computed tomography. Int J Body Compos Res. 2004;1:155–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu L, Duanmu Y, Blake GM, et al. Validation of goose liver fat measurement by QCT and CSE-MRI with biochemical extraction and pathology as reference. Eur Radiol. 2018;28:2003–2012. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5189-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guo Z, Blake GM, Graffy PM et al (2022) Hepatic steatosis: CT-based prevalence in adults in China and the United States and Associations With Age, Sex, and Body Mass Index. AJR Am J Roentgenol 218:846–857. 10.2214/AJR.21.26728 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Agostini A, Borgheresi A, Mari A, et al. Dual-energy CT: theoretical principles and clinical applications. Radiol Med. 2019;124:1281–1295. doi: 10.1007/s11547-019-01107-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fischer MA, Gnannt R, Raptis D, et al. Quantification of liver fat in the presence of iron and iodine: an ex-vivo dual-energy CT study. Invest Radiol. 2011;46:351–358. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e31820e1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng X, Ren Y, Phillips WT, et al. Assessment of hepatic fatty infiltration using spectral computed tomography imaging: a pilot study. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2013;37:134–141. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e31827ddad3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li JH, Tsai CY, Huang HM. Assessment of hepatic fatty infiltration using dual-energy computed tomography: a phantom study. Physiol Meas. 2014;35:597–606. doi: 10.1088/0967-3334/35/4/597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Artz NS, Hines CD, Brunner ST, et al. Quantification of hepatic steatosis with dual-energy computed tomography: comparison with tissue reference standards and quantitative magnetic resonance imaging in the ob/ob mouse. Invest Radiol. 2012;47:603–610. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e318261fad0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel BN, Kumbla RA, Berland LL, Fineberg NS, Morgan DE. Material density hepatic steatosis quantification on intravenous contrast-enhanced rapid kilovolt (peak)-switching single-source dual-energy computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2013;37:904–910. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang Q, Zhao Y, Wu J, et al. Quantification of hepatic fat fraction in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: comparison of multimaterial decomposition algorithm and fat (water)-based material decomposition algorithm using single-source dual-energy computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2021;45:12–17. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000001112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Molwitz I, Campbell GM, Yamamura J, et al. Fat quantification in dual-layer detector spectral computed tomography: experimental development and first in-patient validation. Invest Radiol. 2022;57:463–469. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kullberg J, Hedstrom A, Brandberg J, et al. Automated analysis of liver fat, muscle and adipose tissue distribution from CT suitable for large-scale studies. Sci Rep. 2017;7:10425. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08925-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huo Y, Terry JG, Wang J, et al. Fully automatic liver attenuation estimation combing CNN segmentation and morphological operations. Med Phys. 2019;46:3508–3519. doi: 10.1002/mp.13675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tao S, Rajendran K, McCollough CH, Leng S. Feasibility of multi-contrast imaging on dual-source photon counting detector (PCD) CT: An initial phantom study. Med Phys. 2019;46:4105–4115. doi: 10.1002/mp.13668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leng S, Rajendran K, Gong H, et al. 150-mum spatial resolution using photon-counting detector computed tomography technology: technical performance and first patient images. Invest Radiol. 2018;53:655–662. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Willemink MJ, Persson M, Pourmorteza A, Pelc NJ, Fleischmann D. Photon-counting CT: technical principles and clinical prospects. Radiology. 2018;289:293–312. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018172656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flohr T, Petersilka M, Henning A, et al. Photon-counting CT review. Phys Med. 2020;79:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmp.2020.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fredette NR, Kavuri A, Das M. Multi-step material decomposition for spectral computed tomography. Phys Med Biol. 2019;64:145001. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/ab2b0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Muenzel D, Bar-Ness D, Roessl E, et al. Spectral photon-counting CT: initial experience with dual-contrast agent K-edge colonography. Radiology. 2017;283:723–728. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016160890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Curtis TE, Roeder RK. Quantification of multiple mixed contrast and tissue compositions using photon-counting spectral computed tomography. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 2019;6:013501. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.6.1.013501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leng S, Zhou W, Yu Z, et al. Spectral performance of a whole-body research photon counting detector CT: quantitative accuracy in derived image sets. Phys Med Biol. 2017;62:7216–7232. doi: 10.1088/1361-6560/aa8103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Niehoff JH, Woeltjen MM, Laukamp KR, Borggrefe J, Kroeger JR (2021) Virtual non-contrast versus true non-contrast computed tomography: initial experiences with a photon counting scanner approved for clinical use. Diagnostics (Basel) 11. 10.3390/diagnostics11122377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Sartoretti T, Mergen V, Higashigaito K, et al. Virtual noncontrast imaging of the liver using photon-counting detector computed tomography: a systematic phantom and patient study. Invest Radiol. 2022;57:488–493. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Awaya H, Mitchell DG, Kamishima T, et al. Cirrhosis: modified caudate-right lobe ratio. Radiology. 2002;224:769–774. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2243011495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Huber A, Ebner L, Montani M, et al. Computed tomography findings in liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2014;144:w13923. doi: 10.4414/smw.2014.13923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Obmann VC, Mertineit N, Berzigotti A, et al. CT predicts liver fibrosis: Prospective evaluation of morphology- and attenuation-based quantitative scores in routine portal venous abdominal scans. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0199611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0199611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lv P, Lin X, Gao J, Chen K. Spectral CT: preliminary studies in the liver cirrhosis. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13:434–442. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2012.13.4.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sofue K, Tsurusaki M, Mileto A, et al. Dual-energy computed tomography for non-invasive staging of liver fibrosis: accuracy of iodine density measurements from contrast-enhanced data. Hepatol Res. 2018;48:1008–1019. doi: 10.1111/hepr.13205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marri UK, Das P, Shalimar, , et al. Noninvasive staging of liver fibrosis using 5-minute delayed dual-energy CT: comparison with US elastography and correlation with histologic findings. Radiology. 2021;298:600–608. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021202232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yoon JH, Lee JM, Klotz E, et al. Estimation of hepatic extracellular volume fraction using multiphasic liver computed tomography for hepatic fibrosis grading. Invest Radiol. 2015;50:290–296. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shinagawa Y, Sakamoto K, Sato K, et al. Usefulness of new subtraction algorithm in estimating degree of liver fibrosis by calculating extracellular volume fraction obtained from routine liver CT protocol equilibrium phase data: Preliminary experience. Eur J Radiol. 2018;103:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ito E, Sato K, Yamamoto R, et al. Usefulness of iodine-blood material density images in estimating degree of liver fibrosis by calculating extracellular volume fraction obtained from routine dual-energy liver CT protocol equilibrium phase data: preliminary experience. Jpn J Radiol. 2020;38:365–373. doi: 10.1007/s11604-019-00918-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yoon JH, Lee JM, Kim JH, et al. Hepatic fibrosis grading with extracellular volume fraction from iodine mapping in spectral liver CT. Eur J Radiol. 2021;137:109604. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.109604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smith AD, Branch CR, Zand K, et al. Liver surface nodularity quantification from routine CT images as a biomarker for detection and evaluation of cirrhosis. Radiology. 2016;280:771–781. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016151542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pickhardt PJ, Malecki K, Kloke J, Lubner MG. Accuracy of liver surface nodularity quantification on MDCT as a noninvasive biomarker for staging hepatic fibrosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;207:1194–1199. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.16514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Furusato Hunt OM, Lubner MG, Ziemlewicz TJ, Munoz Del Rio A, Pickhardt PJ. The liver segmental volume ratio for noninvasive detection of cirrhosis: comparison with established linear and volumetric measures. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2016;40:478–484. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000000389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pickhardt PJ, Malecki K, Hunt OF et al (2017) Hepatosplenic volumetric assessment at MDCT for staging liver fibrosis. Eur Radiol 27:3060–3068. 10.1007/s00330-016-4648-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Lubner MG, Malecki K, Kloke J, Ganeshan B, Pickhardt PJ. Texture analysis of the liver at MDCT for assessing hepatic fibrosis. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2017;42:2069–2078. doi: 10.1007/s00261-017-1096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yasaka K, Akai H, Kunimatsu A, Abe O, Kiryu S. Deep learning for staging liver fibrosis on CT: a pilot study. Eur Radiol. 2018;28:4578–4585. doi: 10.1007/s00330-018-5499-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yin Y, Yakar D, Dierckx R, et al. Liver fibrosis staging by deep learning: a visual-based explanation of diagnostic decisions of the model. Eur Radiol. 2021;31:9620–9627. doi: 10.1007/s00330-021-08046-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang J, Tang S, Mao Y, et al. Radiomics analysis of contrast-enhanced CT for staging liver fibrosis: an update for image biomarker. Hepatol Int. 2022;16:627–639. doi: 10.1007/s12072-022-10326-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yin Y, Yakar D, Dierckx R et al (2022) Combining hepatic and splenic CT radiomic features improves radiomic analysis performance for liver fibrosis staging. Diagnostics (Basel) 12. 10.3390/diagnostics12020550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Tsurusaki M, Sofue K, Hori M et al (2021) Dual-energy computed tomography of the liver: uses in clinical practices and applications. Diagnostics (Basel) 11. 10.3390/diagnostics11020161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 81.Lamb P, Sahani DV, Fuentes-Orrego JM, et al. Stratification of patients with liver fibrosis using dual-energy CT. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015;34:807–815. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2014.2353044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Varenika V, Fu Y, Maher JJ, et al. Hepatic fibrosis: evaluation with semiquantitative contrast-enhanced CT. Radiology. 2013;266:151–158. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12112452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zissen MH, Wang ZJ, Yee J, et al. Contrast-enhanced CT quantification of the hepatic fractional extracellular space: correlation with diffuse liver disease severity. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:1204–1210. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.10039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bandula S, Punwani S, Rosenberg WM, et al. Equilibrium contrast-enhanced CT imaging to evaluate hepatic fibrosis: initial validation by comparison with histopathologic sampling. Radiology. 2015;275:136–143. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14141435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Smith AD, Zand KA, Florez E, et al. Liver surface nodularity score allows prediction of cirrhosis decompensation and death. Radiology. 2017;283:711–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2016160799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lubner MG, Smith AD, Sandrasegaran K, Sahani DV, Pickhardt PJ. CT Texture analysis: definitions, applications, biologic correlates, and challenges. Radiographics. 2017;37:1483–1503. doi: 10.1148/rg.2017170056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Daginawala N, Li B, Buch K, et al. Using texture analyses of contrast enhanced CT to assess hepatic fibrosis. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.