Summary

UN member states have committed to universal health coverage (UHC) to ensure all individuals and communities receive the health services they need without suffering financial hardship. Although the pursuit of UHC should unify disparate global health challenges, it is too commonly seen as another standalone initiative with a singular focus on the health sector. Despite constituting the cornerstone of the health-related Sustainable Development Goals, UHC-related commitments, actions, and metrics do not engage with the major drivers and determinants of health, such as poverty, gender inequality, discriminatory laws and policies, environment, housing, education, sanitation, and employment. Given that all countries already face multiple competing health priorities, the global UHC agenda should be used to reconcile, rationalise, prioritise, and integrate investments and multisectoral actions that influence health. In this paper, we call for greater coordination and coherence using a UHC+ lens to suggest new approaches to funding that can extend beyond biomedical health services to include the cross-cutting determinants of health. The proposed intersectoral co-financing mechanisms aim to support the advancement of health for all, regardless of countries’ income.

Introduction

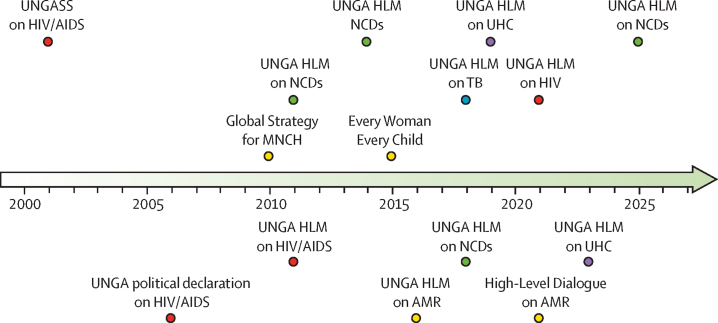

Over the past two decades, a series of outcome documents and political declarations adopted by high-level meetings concerning various specific areas of health at the UN General Assembly have emphasised the key role of universal health coverage (UHC) in achieving health for all.1 UHC is also the centrepiece of the health-related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).2, 3 Although this powerful and galvanising concept has helped to advance broader thinking around the range of health services offered and populations served, paradoxically it has also reinforced a fragmented and biomedically oriented approach to health. Progress on UHC is insufficient to reach SDG target 3.8: achieving UHC, including financial risk protection and access to quality essential health-care services, and safe, effective, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.4, 5

Health service coverage has been rising worldwide since 2010, but not a single country is on course to fully reach all dimensions (service coverage, population coverage, and financial protection) of UHC by 2030. Although health service coverage is high in most high-income countries, stubborn gaps continue to remain in reaching populations most in need.4 The UN 2022 SDG report notes that the COVID-19 pandemic had brought all progress on UHC to a standstill.3, 6

The current conceptualisation of UHC as part of the SDGs was a welcome step towards addressing health issues through a wider socioeconomic development lens. However, SDG Target 3.8 is narrowly focused on the provision of essential health-care services, medicines, and vaccines and does not include indicators to embrace wider determinants of health and global health challenges. Without due consideration of complex and interdependent factors influencing health systems, the realisation of SDG Target 3.8 might not lead to major improvements in the health status-related SDG targets expressed as substantial reductions in mortality and morbidity by 2030 (panel 1).

Panel 1. Health status-related targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

-

•

3.1. By 2030, reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100 000 livebirths

-

•

3.2. By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children youger than 5 years, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1000 livebirths and mortality in children younger than 5 years to at least as low as 25 per 1000 livebirths

-

•

3.3. By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria, and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, waterborne diseases, and other communicable diseases;

-

•

3.4. By 2030, reduce by one-third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and wellbeing (premature mortality is defined as deaths in people aged 30–69 years and excludes mortality in people youger than 30 years from chronic conditions and congenital disorders with major implications for policy and practice)

-

•

3.6. By 2020, halve the number of global deaths and injuries from road traffic accidents

-

•

3.9. By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water, and soil pollution and contamination

The need to implement a whole-of-government approach to health and health-in-all-policies is regularly mentioned in the outcome documents of UN high-level meetings, but rarely put into practice. This inaction at the national level is because of the sectoral allocation of resources and budgets, with an inadequate appreciation of the impact and co-benefits of multisectoral action on health and the need for financial commitments and shared targets to measure progress towards reaching health for all.7

In the lead up to 2030, and in the wake of the UN high-level meeting on UHC in September, 2023, we encourage policy makers to think broadly about UHC as a means to connect all of the health-related SDGs with pre-existing commitment frameworks related to global health. Our working group proposes a broader conceptualisation, UHC+, which recognises the importance of the wider social determinants of health and integrates financing and action across sectors to achieve public health objectives.

Although redefining UHC or revising the available metrics to measure it would be counterproductive in the countdown to 2030, there is value in highlighting actions that can be taken to deliver cross-cutting policies and interventions. As such, UHC+ is a way of thinking broadly about health service coverage that stresses the upstream determinants of health and interdependencies among different health silos that are key to reaching UHC.

The rising importance of health within the global development agenda

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) provided an excellent framework for focusing on some communicable diseases (eg, HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and vaccine-preventable diseases) and advancing maternal and child survival goals with a narrow set of prioritised interventions. However, the MDGs and the targeted development assistance for health were not well aligned with the global burden of disease in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs), particularly for non-communicable diseases (NCDs).

Since 2010, there has been growing attention on several specific health areas that are hampering countries’ socioeconomic development due to high disease burden, resulting in several UN General Assembly special sessions and high-level meetings on HIV, NCDs, antimicrobial resistance, tuberculosis, and UHC. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development brought all health areas under one health goal—SDG3 “to ensure healthy lives and promote wellbeing for all, at all ages”.5 Many other development goals also have important implications for health and UHC by addressing various determinants of health.

Although SDGs are inter-related and reflect all three dimensions of development (social, economic, and environmental), few of these goals integrate other sectors into their targets, and many of them are severely underfunded. For example, the 2022 estimates for the nine SDGs with health implications (SDG 2 on zero hunger; SDG 3 on health; SDG 4 on quality education; SDG 6 on clean water and sanitation; SDG 7 on access to energy; SDG 9 on infrastructure; SDG 13 on climate action; SDG 14 on life below water; and SDG 15 on life on land) indicate that, for most SDGs, hundreds of billions of US$ are required per year, while SDG 6 and SDG 13 would need more than $1 trillion annually.8 Meeting the SDG financing gap for all 59 low-income countries requires an estimated $400 billion per year between 2019 and 2030, and achieving SDG target 3.4 alone would require $140 billion in new spending between 2023 and 2030,9 or an average of $18 billion annually10 (figure 1, panel 2). Each UN General Assembly high-level meeting outcome document cross-references other areas of health and development, highlighting the need for intersectoral action and investments from multiple sources (table 1).

Figure 1.

Health-related UNGA special sessions and HLM

AMR=antimicrobial resistance. HLM=high-level meeting. MNCH=maternal, neonatal, and child health. NCD=non-communicable disease. TB=tuberculosis. UHC=universal health coverage. UNGA=UN General Assembly. UNGASS=UN General Assembly special session.

Panel 2. Mortality data for non-communicable diseases (NCDs), tuberculosis, HIV, antimicrobial resistance, and maternal and child health.

-

•

Almost 5 million people died from drug-resistant infections in 201911

-

•

NCDs kill 41 million people each year, which is equivalent to 74% of all deaths globally. In 2019, 17 million people died of NCDs before reaching the age of 70 years, with 86% of these deaths in low-income and middle-income countries12

-

•

1·6 million people died from tuberculosis in 2021 (including 187 000 people who died from HIV) Worldwide, tuberculosis is the 13th leading cause of death and the second highest cause of infectious disease death after COVID-1913

-

•

A total of 650 000 people died from AIDS-related illnesses in 202112

-

•

The world is not on track to reach a maternal mortality ratio of less than 70 per 100 000 livebirths14

-

•

15 000 children younger than 5 years die every day, mainly from preventable conditions15

Table 1.

Cross-referencing paragraph themes within UN General Assembly high-level meeting outcome documents

| UHC | HIV/AIDS | Tuberculosis | AMR | NCDs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UHC | .. | 2, 67 | 2, 34, 37, and 51 | 5, 9 | 35 |

| HIV/AIDS | 4, 32 | .. | 2, 6, 10, and 29 | 5 | 39 |

| Tuberculosis | 4, 32 | 2, 43 | .. | 5 | 39 |

| AMR | 4 | 2 | 2, 12, and 27 | .. | NA |

| NCDs | 4, 33, 36 | 2, 45 | 2, 6 | .. | .. |

| Financing | 39, 40, 44, 45, 52, and 53 | 43, 50, 52, 63, 64, 66, and 68 | 4, 9, 11, 21, 46, and 47 | 10, 12 | 46, 48 |

| Multisectoral action | 28, 76 | 12, 14, 65, 67, and 70 | 4, 7, and 39 | 12 | 15, 17 |

| Health system strengthening | 8, 27, and 42 | 2, 46 | 9, 16 | 9 | 35 |

| Access to medicines | 8 | 2 | 6, 19, and 20 | 4 | 35, 36 |

| Research | 52, 76 | 1, 69 | 4, 7 | 9 | 27 |

| Social and economic development | 5 | 2 | 17 | 4 | 3, 5 |

Source documents: Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on Antimicrobial Resistance, Sept 21, 2016, New York, NY, USA; Political declaration of the 3rd High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non-Communicable Diseases, Sept 27, 2018, New York, NY, USA; Political Declaration of the High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Fight Against Tuberculosis, Sept 26, 2018, New York, NY, USA; Political Declaration of the High-level Meeting on Universal Health Coverage, Sept 12, 2019, New York, NY, USA; Political Declaration on HIV and AIDS: Ending inequalities and getting on track to end AIDS by 2030, June 9, 2021, New York, NY, USA. AMR=antimicrobial resistance. HLM=high-level meeting. NA=not applicable. NCDs=non-communicable diseases. UHC=universal health coverage.

Realisation of the commitments made at the UN high-level meetings and their real-world effect has proved challenging to quantify. Attributing any changes in mortality or morbidity to political events is particularly difficult as health status depends on many factors within and beyond health systems, including baseline levels of populations’ health, prioritisation of disease burden, funding, and implementation of policies and context-specific interventions. Rodi and colleagues16 found that health-related high-level meetings (on HIV, tuberculosis, antimicrobial resistance, and NCDs) have contributed to greater mobilisation of national and global political commitments, but no major attributable changes were observed in the quantum of financing or trajectory of mortality rates, except for HIV.

Interdependence

Integration has long been advocated for as an approach for improving linkages and synergies among converging areas of global health such as HIV/AIDS; tuberculosis; maternal, neonatal, and child health; sexual and reproductive health; and NCDs.5, 7 The term integration has many applications, ranging from integrating policies and strategies to integrating service delivery across levels of care and the life course. The WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services envisages the end goal of people receiving the full range of services that they require in a continuum rather than via fragmented standalone interventions.17

The convergence of the burden of communicable diseases, maternal and child health, and NCDs (panel 3), and the unfinished maternal, neonatal, and child health agenda present challenges and opportunities to create positive changes in policy, research, public health programming, and integrated delivery of services for chronic conditions and multimorbidity throughout the life cycle.22 Shared risk factors, such as air pollution, poor housing, and poverty contribute to a range of communicable diseases and NCDs. The COVID-19 pandemic, the crises in Ukraine and the middle east, climate change, and many other emergencies have further underlined the syndemic nature of these conditions and strengthened the case for investment in cross-cutting interventions exemplified by UHC.23, 24

Panel 3. Examples of convergence.

HIV and cervical cancer

Women living with HIV are 5 times more likely to develop invasive cervical cancer and at an earlier age than women not living with HIV; invasive cervical cancer is the second most common cancer among women in low-income and middle-income countries. Integration of screening (by use of high-performance tests starting at the age of 25 years) and treatment of precancerous lesions and invasive cervical cancer into HIV care is an effective way to prevent cervical cancer deaths among these women.18

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and maternal and child mortality

Between 2000 and 2020, the maternal mortality ratio dropped by almost 34% globally. The decline in maternal deaths is mainly due to improved availability of effective obstetric interventions and technologies.19 However, indirect maternal deaths as a consequence of pre-existing chronic conditions have been on the rise.20 Hyperglycaemia complicates 17% of pregnancies, including women with diagnosed and undiagnosed diabetes and gestational diabetes.21 NCDs during pregnancy can increase the risk of spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, congenital malformations, infant respiratory death syndrome, and birth injuries.

None of the health-related SDG targets can be reached without addressing the wider social, political, commercial, and economic determinants of health through a whole-of-government approach as these factors are more substantial drivers of overall health outcomes than biomedical interventions delivered by health-care systems. Repeated attempts to quantify the population-attributable fraction of the contribution of clinical medicine to health outcomes have revealed an estimated figure of 10–25%, whereas the broader social determinants of health—the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age25—are responsible for 40–60% of overall health outcomes.26, 27, 28

A clear example comes from examining cross-sectoral links in the context of child health: Blomstedt and colleagues29 documented all of the interdependencies between SDG 3 (health) and other goals that specifically mention children, identifying 24 SDGs in total (1.2; 1.3.1; 2.1; 2.2; 4.1; 4.2; 4.4; 4.5; 4.6; 4a; 5.1; 5.2; 5.3; 5c; 6.2; 8.6; 8.7; 8b; 11.2; 11.7; 13b; 16.2; 16.9; and 16.9.1). Just as health-related goals are largely interdependent, health itself is linked to all the SDGs, as illustrated by WHO. The signatories of the SDG action agenda acknowledge that all 17 SDGs and 169 targets are interdependent, and the achievement of sustainable development requires multidimensional and intersectoral interventions. Furthermore, a key goal of SDG 3 was to foster integration across the different health targets; however, this is not manifested within the indicators. In the absence of clear targets and guidance on how to address cross-cutting issues, it is unsurprising that the fragmented and single-issue approach to SDG attainment has become the norm.

Many non-health sectors and domains influence health: agricultural policy directly affects human nutrition; transport policy can incentivise physical activity; housing policy can address challenges of sanitation and overcrowding; education is foundational in developing health literacy; industrial policy influences air quality and water safety; and culture and sports can encourage participation in physical activity. Tax, social welfare, and environmental policies also strongly influence the conditions in which people live, work, and age. Nunes and colleagues30 provide further analysis of the synergies between health and other SDG sectors. There are many areas where health and other ministries and sectors can allocate budgets to reach mutually beneficial outcomes—eg, investments in active transport networks, green energy, safe housing, and occupational health.

The role of UHC in integrating other health targets

UHC is commonly portrayed as the means for achieving other health-related targets. However, the alignment of indicators for UHC (that concentrate on health spending and 14 tracer indicators) and those for the other issues represented in SDG 3 is poor. Even if UHC were aligned with other health-related targets, its biomedical focus on access to essential services, medicines, and vaccines limits the use of UHC for unifying the health agenda. UHC has the potential to act as a convergence vehicle for SDG 3; however, UHC will not be able to deliver health for all in its current format, given that the social determinants of health lie beyond its remit.

In 2017, the Disease Control Priorities (DCP3) project sought to expand the scope of UHC to include a range of upstream and intersectoral interventions to address shared risk factors for multiple conditions. Traditionally, essential services included in basic benefit packages comprised major infectious diseases (HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria), neglected tropical diseases, family planning, and maternal and child health, with coverage for NCDs lagging.31 DCP3 identified 218 essential UHC interventions that included 71 intersectoral policies designed to tackle environmental and behavioural risk factors, such as tobacco and alcohol use, air pollution, micronutrient deficiencies in diet, unsafe sexual behaviour, excessive sugar consumption, and others.32 Although the mainstream use of UHC focuses on extending access to clinical services, these interventions sought to expand the scope of the concept beyond standard clinical service delivery.

In 2023, the Lancet Commission on synergies between UHC, health security, and health promotion identified a need for a “comprehensive holistic vision of health and legal frameworks that will integrate promotion, surveillance, prevention and control, treatment, care and rehabilitation”.33 The Commission recommended moving away from ill-conceived political interests and decisions that contribute to fragmentation at both global and national levels.33 Integration is also playing a key role in the fields of health system strengthening, global health security, and pandemic preparedness and response.34, 35, 36

Building on the work of DCP3 and the Lancet Commission, and in the run-up to 2030, we encourage policy makers to take a broader view of how to reach UHC, resisting the urge to focus on a very narrow set of clinical interventions, since clinical service provision is only one piece of the jigsaw puzzle. The rallying cry for health must encompass the wider drivers of health, connect existing priorities, and draw attention to multisectoral actions required to accelerate progress.

We propose UHC+ as a concept to unite these imperatives, crystalising the need for joined-up thinking, financing, and action to address the cross-cutting drivers of health and disease. UHC+ recognises that the focused goals of UHC must be bolstered by intersectoral action and greater coherence. UHC+ is also a potential vehicle to integrate action on other high-priority initiatives, such as pandemic preparedness and response, and health system strengthening.

Financing UHC+

UHC+ requires due attention to the social, economic, and environmental determinants of health, with intersectoral funding of actions to advance health. Research by Savedoff37 suggests that no LMIC has successfully extended UHC without using pooled financing mechanisms in the context of rising national incomes. Implementation of a comprehensive approach required by UHC+ will call for intersectoral policies, services, accountability mechanisms, and financing structures, such as those proposed by Oni and colleagues.38 Three broad principles for generating sufficient financial resources for UHC+ are: moving towards non-contributory public funding sources, such as general taxation; pooling to boost redistribution capacity; and adopting of strategic purchasing practices—linking transfers of funds to performance to boost efficiency and promote equity.39

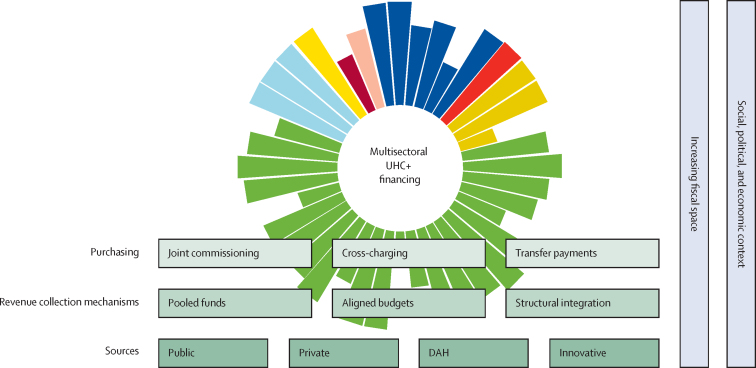

In addition to requiring an increase in the absolute amount of funds allocated to health, UHC+ requires cross-sectoral financing in the form of co-financing, where money is pooled across public sector payers and then used to purchase health-care and non-health interventions that maximise health outcomes (table 2).

Table 2.

Types of financial mechanisms for co-financing

| Definition | |

|---|---|

| Revenue collection | |

| Aligned budgets | Budget holders align resources and identify their own contributions towards prespecified common objectives. Joint monitoring of spending and performance, but management remains separate |

| Pooled funds | At least two budget holders make contributions to a single pool for spending on pre-agreed services or interventions, which can be done at various levels (national, regional, or local) and accessed in different ways (eg, grants of the regular budgetary system) |

| Sectoral integration | Full integration of cross-sector responsibilities, finances, and resources under single management or a single organisation |

| Purchasing | |

| Joint commissioning | Separate budget holders jointly identify a need and agree on a set of objectives, then commission services and track outcomes. The commissioning itself can be done through a joint authority board or one agency taking commissioning responsibility |

| Cross-charging | The mechanism whereby a cross-sector financial penalty is incurred for the non-achievement of a prespecified target. Cross-charging compensates sectors that incur an external cost from another sector's poor performance. |

| Transfer payments | Sectoral budget holders make service revenue or capita contributions to bodies in other sectors to support additional services or interventions in these other sectors. |

These revenue collection and purchasing mechanisms can help to effectively channel funding towards cross-cutting issues and intersectoral actions that promote good health and wellbeing. National governments also have a strategic role in designing and regulating the blend of financing models that operate domestically. Figure 2 presents a conceptual framework that shows how sources of funds and the mechanisms used to enable intersectoral financing inter-relate. The main sources are public, private, development assistance for health, and other (originally dubbed innovative) financing mechanisms operating along similar lines to the Global Fund, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the Global Financing Facility, and the World Bank Pandemic Fund (figure 2).40

Figure 2.

Conceptual framework for the inter-relationships between sources of funds and the mechanisms used to enable intersectoral financing

DAH=development assistance for health. UHC=universal health coverage.

Actions to deliver intersectoral financing

Health is an important global political priority that has been reflected in a growing number of commitments and high-level meetings. However, much remains to be done. The current action to translate promises and ambitions into reality is inadequate, leaving millions at risk partly because focus and funding are oriented around single issues, conditions, and diseases.

Globally, total health spending has been increasing over the last decade, reaching $7·9 trillion in 2017. This number is predicted to reach $11·0 trillion by 2030, and $16·7 trillion by 2050.41 Domestic funding remains the main source of funding for health, and increased more than five times between 2000 and 2015, exceeding $1·5 trillion in LMICs. External resources are an important source of funding in LMICs, constituting 30% of current health expenditure.42 However, these investments are not sufficient to reach the SDG targets, including UHC, by 2030.

More than 800 million people globally spend at least 10% of their income on health care through out-of-pocket payments. In sub-Saharan Africa, residents of 27 (56%) of 48 countries incur direct out-of-pocket costs that are higher than 30% of their income, which pushes people deeper into poverty each year.43 Between 27 million and 50 million people spend more than 40% of their income each year to access NCD services. The total number of people experiencing catastrophic health expenditure (40% threshold) is estimated to be 208 million.44

Financial protection from catastrophic out-of-pocket medical treatment costs could be achieved if every government would commit to spending at least 5% of gross domestic product on health care and ensure about $86 in health expenditure per capita. Most middle-income countries should be able to reach this target without external assistance.45

Domestic public funding through prepaid and pooled financing is a means of achieving UHC and financial risk protection. However, globally this fraction of funding contributing to UHC ranges from 6·7% in Afghanistan to 100% in Greenland.46 In low-income countries, average government spending per capita increased from $7 in 2000 to $9 in 2016.47 None of these countries can afford even the basic interventions for UHC.48

Investments in cross-cutting actions that span SDG domains are required. The estimated $400 billion in additional annual investments needed for the 59 low-income countries to achieve SDGs by 2030 is several orders of magnitude higher than the average total tax revenue in most of these countries. In 2018, only five countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development fulfilled their commitment to providing 0·7% of their gross national income to overseas development assistance: Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden, and the UK. Even though development assistance for health is an essential element in promoting UHC,49 we argue that intersectoral financing, which involves mobilising all sectors as they intersect with health, will help governments leverage additional resources to achieve health goals by addressing root causes. Panel 4 outlines our recommendations.

Panel 4. Recommended actions for intersectoral financing.

-

•

Use a blend of public, private, external, and innovative financing sources, but focus on developing public sources as the main source of multisectoral financing

-

•

Pursue non-contributory pooling approaches, aligned budgets, and structural integration to collect revenue

-

•

Look for cross-linkages and synergies to define the nature of multisectoral funding opportunities

-

•

Allocate at least 5% of gross domestic product to health care

-

•

Use joint commissioning, cross-charging, and transfer payments for purchasing

-

•

Finance multisectoral actions that target shared risk factors for communicable and non-communicable conditions

We identify four issues that need addressing through decisive action. First, the model focusing on a small number of diseases and conditions as part of the UHC packages does not reflect the complex and interconnected reality related to the health of individuals and communities. Second, the current scope of action towards UHC is inappropriately biomedical and reductionist—focused on delivering health care for all rather than health for all. Third, the current financing is inadequate to fund UHC. Fourth, the patterns of financing and funding flows are ill-suited for UHC and hinder cross-cutting intersectoral approaches.

Three standalone high-level health meetings took place in September, 2023. Policy makers should look for synergies between tuberculosis, NCDs, and pandemic preparedness and response and use the UHC+ lens to engage with the wider social determinants of health and other SDG domains as they prioritise their actions.

Conclusions

The current suite of actions to deliver UHC is worthy and important, but ultimately insufficient to bear the load placed upon it as the cornerstone of the health-related SDGs. A much more expansive approach to financing and action is required. We propose the use of blended financing and co-financing, based on higher levels of domestic spending and high-income countries making good on their commitments to development assistance.

The move towards UHC+ radically simplifies the current global health situation, converging multiple individual issues and focusing attention on shared drivers, risk factors, and integrated services to provide a continuum of care across the life course. Those synergistic and integrated approaches should be informed by population and individual needs and local contexts, and align with primary health-care principles of equity, solidarity, and the right to health.

By folding multiple overlapping UN commitments under one umbrella, we hope that our UHC+ concept helps to join the dots for policy makers as they strive to act on the commitments made at the UHC high-level meeting in September, 2023. WHO and the broader Coalition of Partnerships for UHC and global health have a key role in supporting countries’ efforts to balance competing priorities and promote health at home. Moving away from competing vertical issues to a more holistic view of financing horizontal systems that respond to people's needs is well served by the broad concept of UHC+.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank Katie Dain, Helga Fogstad, Lucicia Ditiu, and Corine Karema for the support in developing this paper as part of the work of the Coalition of Partnerships for UHC and Global Health. We gratefully acknowledge the insightful comments of Neena Joshi at the conception of this paper. Special thanks are extended to George Alleyne for his valuable contribution to the early drafts of the manuscript. The paper is the output of the working group of the Coalition of Partnerships for UHC and Global Health coordinated by the Secretariat of UHC2030. The authors alone are responsible for the views expressed in this paper and such views do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or policies of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

Contributors

TEC conceptualised the paper in consultation with all authors and external experts as part of the Coalition of Partnerships for UHC and Global Health and wrote the first draft. SA, RA, SB, OO, MH, and JR provided extensive feedback. AS, DB, IK, AM, and AW provided examples from their respective areas of expertise. LNA consolidated all feedback. TEC and LNA finalised the paper. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.UHC 2030 Taking action for universal health coverage: key documents. 2023. https://www.uhc2030.org/un-hlm-2023/

- 2.UN Newsroom WHO welcomes landmark UN declaration on universal health coverage. Sept 23, 2019. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/blog/2019/09/who-welcomes-landmark-un-declaration-on-universal-health-coverage/

- 3.UN The Sustainable Development Goals report 2022. 2022. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/

- 4.WHO Tracking universal health coverage: 2021 global monitoring report. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240040618

- 5.Sustainable development goals knowledge platform A/RES/70/1 - Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Sustainable development knowledge platform. 2015. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=111&nr=8496&menu=35

- 6.Wagstaff A, Neelsen S. A comprehensive assessment of universal health coverage in 111 countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e39–e49. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holt DH, Rod MH, Waldorff SB, Tj⊘rnh⊘j-Thomsen T. Elusive implementation: an ethnographic study of intersectoral policymaking for health. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:54. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2864-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kulkarni S, Hof A, Ambrósio G, et al. Investment needs to achieve SDGs: an overview. PLoS Sustain Transform. 2022;1 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sustainable Development Solutions Network SDG costing and financing for low-income developing countries. Sept 23, 2019. https://resources.unsdsn.org/sdg-costing-financing-for-low-income-developing-countries?_ga=2.229594010.703084897.1697740602-88681169.1697740602

- 10.Countdown NCD. 2030 collaborators NCD Countdown 2030: efficient pathways and strategic investments to accelerate progress towards the Sustainable Development Goal target 3·4 in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2022;399:1266–1278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02347-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murray CJL, Ikuta KS, Sharara F, et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399:629–655. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.UNAIDS Global HIV and AIDS statistics—factsheet. 2023. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

- 13.WHO TB factsheet. April 23, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tuberculosis

- 14.World Bank Progress in reducing maternal mortality has stagnated. 2023. https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/progress-reducing-maternal-mortality-has-stagnated-and-we-are-not-track-achieve-sdg-target

- 15.WHO Factsheet: children: improving survival and wellbeing. Sept 8, 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/children-reducing-mortality

- 16.Rodi P, Obermeyer W, Pablos-Mendez A, Gori A, Raviglione MC. Political rationale, aims, and outcomes of health-related high-level meetings and special sessions at the UN General Assembly: a policy research observational study. PLoS Med. 2022;19 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. Report: WHO/HIS/SDS/2015.6. 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/155002

- 18.UNAIDS HPV, HIV and cervical cancer: leveraging synergies to save women's lives. July 20, 2016. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2016/HPV-HIV-cervical-cancer

- 19.WHO Maternal mortality. Feb 22, 2023. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality

- 20.Brumana L, Arroyo A, Schwalbe NR, Lehtimaki S, Hipgrave DB. Maternal and child health services and an integrated, life-cycle approach to the prevention of non-communicable diseases. BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mirghani Dirar A, Doupis J. Gestational diabetes from A to Z. World J Diabetes. 2017;8:489–511. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v8.i12.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Remais JV, Zeng G, Li G, Tian L, Engelgau MM. Convergence of non-communicable and infectious diseases in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:221–227. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins T, Tello J, Van Hilten M, et al. Addressing the double burden of the COVID-19 and noncommunicable disease pandemics: a new global governance challenge. Int J Health Gov. 2021;26:199–212. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendenhall E, Kohrt BA, Norris SA, Ndetei D, Prabhakaran D. Non-communicable disease syndemics: poverty, depression, and diabetes among low-income populations. Lancet. 2017;389:951–963. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30402-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health–final report of the commission on social determinants of health. Aug 27, 2008. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Bishai DM, Cohen R, Alfonso YN, Adam T, Kuruvilla S, Schweitzer J. Factors contributing to maternal and child mortality reductions in 146 low- and middle-income countries between 1990 and 2010. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bharmal N, Derose KP, Felician M, Weden MM. Understanding the upstream social determinants of health. RAND Health. 2015:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGinnis JM, Williams-Russo P, Knickman JR. The case for more active policy attention to health promotion. Health Aff. 2002;21:78–93. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blomstedt Y, Bhutta ZA, Dahlstrand J, et al. Partnerships for child health: capitalising on links between the Sustainable Development Goals. BMJ. 2018;360:k125. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nunes AR, Lee K, O'Riordan T. The importance of an integrating framework for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: the example of health and well-being. BMJ Glob Health. 2016;1 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.GBD 2019 Viewpoint Collaborators Five insights from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1135–1159. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31404-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jamison DT, Alwan A, Mock CN, et al. In: Disease control priorities: improving health and reducing poverty. 3rd edn. Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S, et al., editors. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; Washington, DC: 2017. Universal health coverage and intersectoral action for health. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agyepong I, Spicer N, Ooms G, et al. Lancet Commission on synergies between universal health coverage, health security, and health promotion. Lancet. 2023;401:1964–2012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01930-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hafner T, Shiffman J. The emergence of global attention to health systems strengthening. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28:41–50. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO Fostering resilience through integrated health system strengthening: technical meeting report. Aug 21, 2021. https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240033313

- 36.WHO WHO launches new initiative to improve pandemic preparedness. April 26, 2023. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-04-2023-who-launches-new-initiative-to-improve-pandemic-preparedness

- 37.Savedoff W. Results for Development Institute; 2012. Transitions in health financing and policies for universal health coverage: final report of the transitions in health financing project.https://Summary-Transitions-in-Health-Financing-and-Policies-for-Universal-Health-Coverage.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oni T, Mogo E, Ahmed A, Davies JI. Breaking down the silos of universal health coverage: towards systems for the primary prevention of non-communicable diseases in Africa. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathauer I. Strategic purchasing for universal health coverage: key policy issues and questions: a summary from expert and practitioners' discussions. 2017. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259423

- 40.Atun R, Silva S, Knaul FM. Innovative financing instruments for global health 2002–15: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5:e720–e726. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30198-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Financing Global Health. 2020. https://www.healthdata.org/data-tools-practices/interactive-visuals/financing-global-health

- 42.Watkins DA, Yamey G, Schäferhoff M, et al. Alma-Ata at 40 years: reflections from the Lancet Commission on Investing in Health. Lancet. 2018;392:1434–1460. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32389-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ifeagwu SC, Yang JC, Parkes-Ratanshi R, Brayne C. Health financing for universal health coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Glob Health Res Policy. 2021;6:8. doi: 10.1186/s41256-021-00190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bukhman G, Mocumbi AO, Atun R, et al. The Lancet NCDI Poverty Commission: bridging a gap in universal health coverage for the poorest billion. Lancet. 2020;396:991–1044. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31907-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.R⊘ttingen J, Ottersen T, Ablo A, et al. Shared responsibilities for health: a coherent global framework for health financing. Final report of the Centre on Global Health Security Working Group on health financing. 2014. https://researchonline.lshtm.ac.uk/id/eprint/4648019/

- 46.Micah AE, Su Y, Bachmeier SD, et al. Health sector spending and spending on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, and development assistance for health: progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 3. Lancet. 2020;396:693–724. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30608-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.WHO Global health expenditure database. 2023. https://apps.who.int/nha/database

- 48.Watkins DA, Jamison DT, Mills A, et al. In: Disease control priorities: improving health and reducing poverty. 3rd edn. Jamison DT, Gelband H, Horton S, et al., editors. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and The World Bank; Washington, DC: 2017. Universal health coverage and essential packages of care. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Collins TE, Nugent R, Webb D, Placella E, Evans T, Akinnawo A. Time to align: development cooperation for the prevention and control of non-communicable diseases. BMJ. 2019;366 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]