Abstract

Designing cost‐effective alkaline water‐splitting electrocatalysts is essential for large‐scale hydrogen production. However, nonprecious catalysts face challenges in achieving high activity and durability at a large current density. An effective strategy for designing high‐performance electrocatalysts is regulating the active electronic states near the Fermi‐level, which can improve the intrinsic activity and increase the number of active sites. As a proof‐of‐concept, it proposes a one‐step self‐assembly approach to fabricate a novel metallic heterostructure based on nickel phosphide and cobalt sulfide (Ni2P@Co9S8) composite. The charge transfer between active Ni sites of Ni2P and Co─Co bonds of Co9S8 efficiently enhances the active electronic states of Ni sites, and consequently, Ni2P@Co9S8 exhibits remarkably low overpotentials of 188 and 253 mV to reach the current density of 100 mA cm−2 for the hydrogen evolution reaction and oxygen evolution reaction, respectively. This leads to the Ni2P@Co9S8 incorporated water electrolyzer possessing an ultralow cell voltage of 1.66 V@100 mA cm−2 with ≈100% retention over 100 h, surpassing the commercial Pt/C║RuO2 catalyst (1.9 V@100 mA cm−2). This work provides a promising methodology to boost the activity of overall water splitting with ultralow overpotentials at large current density by shedding light on the charge self‐regulation of metallic heterostructure.

Keywords: active electronic state, bifunctional electrocatalyst, heterostructure, one‐step self‐assembly approach, water splitting

The metallic Ni2P@Co9S8 heterostructure is a highly efficient and stable bifunctional catalyst for overall water splitting. The electron transfer from Co─Co bonds of Co9S8 to active Ni sites of Ni2P in the heterointerface modulates the active electronic states of Ni sites, holding great potential to lower the energy cost for hydrogen generation.

1. Introduction

Electrochemical water splitting is a sustainable and promising technology for clean hydrogen generation, especially in alkaline conditions that are commercially practical for large‐scale hydrogen production.[ 1 ] While commercial Pt/C and IrO2/RuO2 have demonstrated exceptional activity for hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER), respectively, their high cost and limited availability hinder their widespread applications.[ 2 ] Recently, nonprecious metal‐based catalysts exhibit remarkable electrocatalytic activity for water splitting at low current density (10‐50 mA cm−2), but achieving larger current density for large‐scale production remains a challenge.[ 3 ] To address this issue, various approaches such as bimetallic engineering,[ 4 , 5 ] crystal phase regulation,[ 6 ] defect introduction,[ 7 , 8 ] nonmetal doping,[ 9 ] and heterostructure construction[ 10 , 11 ] have been extensively developed. Based on the earlier pioneering work,[ 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ] the sluggish water dissociation step in alkaline media has been identified as a bottleneck for robust water electrolysis with low cell voltage. This involves the Volmer step of cleaving H─OH bond to form an adsorbed hydrogen atom (H ad) and the Heyrovsky step of combining H ad with other H─OH bonds to generate H2. Thus, water adsorption/dissociation and hydroxyl groups (OH−) adsorption lead to higher cell voltage at large current density.

To develop ideal bifunctional catalysts with large current density water splitting (HER/OER) at lower overpotentials, several requirements need to be fulfilled, including sufficient active sites for rapid adsorption/dissociation of OH−/H2O, high electrical conductivity, continuous H2/O2 escape, and superior mechanical stability. Ni‐based compounds, such as (oxy)hydroxides, oxides, sulfides, pnictides, nitrides, and their composites, have shown great potential for large current density water splitting.[ 7 , 11 , 16 ] While Raney Ni has demonstrated potential as a bifunctional electrocatalyst for large current density water splitting, its intrinsic activity remains unsatisfactory, resulting in a cell voltage (1.8–2.4 V) that is significantly higher than the thermodynamic potential (1.23 V).[ 14 ] It is highly desirable to design efficient Ni‐based catalysts for hydrogen production.[ 17 ] Among various Ni‐based materials, nickel phosphide is a promising catalyst for HER due to its low cost and efficient catalytic activity.[ 18 ] However, it has high energy barrier for oxygen‐containing intermediates adsorption in OER process and H2O molecule dissociation during the HER process in alkaline solution, which hinders its wide application in overall water splitting.[ 19 ] Combining the nickel phosphide with other materials that need small energy to adsorb oxygen‐containing intermediates, such as oxides, hydroxides, and chalcogenides, is an effective strategy to derive advanced catalysts. Some novel heterostructures have been developed, such as Ni5P4@NiCo2O4,[ 20 ] Co2P–Ni2P/TiO2 [ 21 ] and sc‐Ni2Pδ−/NiHO,[ 22 ] in which the oxides or hydroxides were used to expedite the kinetics of water splitting. Especially, the low conductivity of oxides and hydroxides hamper the electron transport during the electrochemical processes, leading to sluggish kinetics in the overall water splitting. Chalcogenides with higher electron conductivity are more suitable for use in nickel phosphide‐based heterostructure, although the S─Had bonds on the surface of the metal sulfides in the HER process are too strong, making the conversion of Had to H2 difficult. Thus, constructing heterostructure through combining chalcogenide equipped with higher electron conductivity with moderate H atom binding energy of nickel phosphide may be a promising approach to accelerate electron transfer kinetics and enhance overall water splitting ability.[ 23 ]

Herein, we design a novel bifunctional electrocatalyst via a one‐step self‐assembly strategy, consisting of Ni2P@Co9S8 metallic heterostructure conductor attached to a vulcanized nickel foam (VNF). The unique structure of Ni2P@Co9S8 metallic heterostructure provides increased exposure of active sites to electrolytes and enables efficient adsorption/desorption of *H and oxygen‐contain intermediates while lowering the energy barrier for water dissociation. As a result, the as‐prepared catalyst exhibits remarkably low overpotentials of 188 and 253 mV to reach the current density of 100 mA cm−2 of HER and OER, respectively. In a symmetrical two‐electrode cell, Ni2P@Co9S8 performs effectively as both the cathode and anode, achieving an ultralow cell voltage of only 1.66 V at the current density of 100 mA cm−2 for overall water splitting. This approach provides a promising method for the design of bifunctional electrocatalysts for water splitting.

2. Results and Discussion

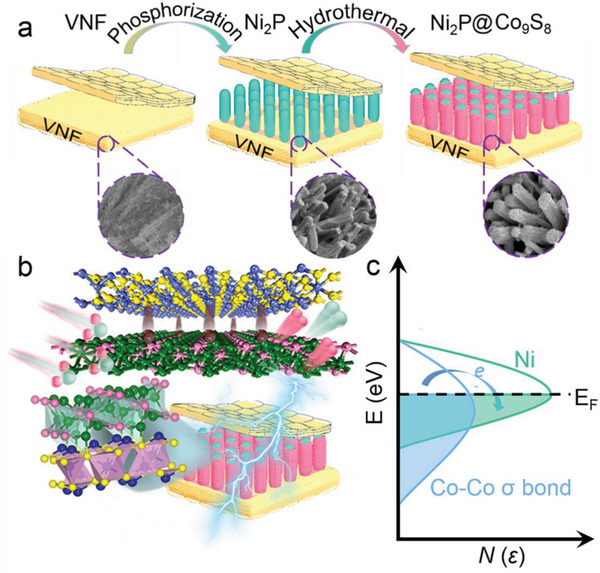

As depicted schematically in Figure 1a, the synthesis of a Co9S8 nanoflakes‐anchored Ni2P nanorods structure was achieved through one‐step self‐assembly hydrothermal method (see Experimental Section for details). The resulting metallic heterointerface between Ni2P and Co9S8, which can be used for overall water splitting, is further depicted in Figure 1b. In Figure 1c, we propose that the Co9S8 containing active Co─Co σ bonds could serve as an electron reservoir to regulate the electronic state of active Ni2P. For the Ni2P@Co9S8 composite, the charge regulation from Co─Co σ bonds to an active site can further optimize the active electronic states of Ni around the Fermi‐level, favorable for enhancing catalytic activity. Gap states around the Fermi‐level are mainly generated by active Ni atoms, where the charge of active atoms is transferred between Co─Co bonds and Ni atoms. The activated 3d‐bands of Ni atom in Ni2P@Co9S8 can not only interact strongly with S atom in deep energy level but also isolate across the Fermi‐level benefitting the formation of heterointerface and the enhanced catalytic activity of OER half‐reaction. Thus, the charge regulation effect on the active electronic states of Ni and Co sites around the Fermi‐level, in which the Co─Co regulate the Ni active sites near the Fermi‐level, which form moderate electronic states for intermediates adsorption in the electrochemical reaction, resulting in improved electrocatalytic performance. In addition, morphology analysis was carried out using field‐emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and high‐angle annular dark‐field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF‐STEM).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams. Schematic illustrations of a) the fabrication of Co9S8 nanoflakes on Ni2P nanorods, b) the water splitting of Ni2P@Co9S8 metallic heterostructure, and c) the charge compensation effect on the active electronic states in Ni2P@Co9S8 metallic heterostructure.

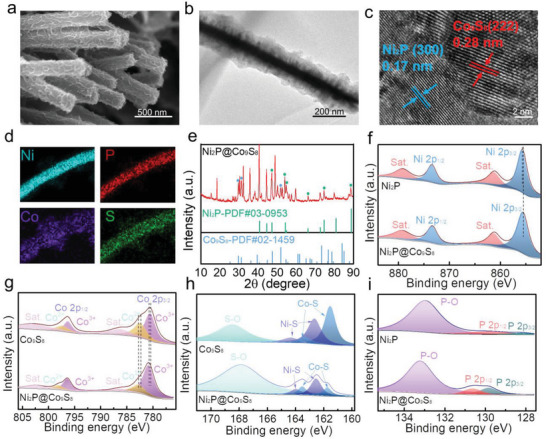

As shown in Figure 2a, the SEM image of Ni2P@Co9S8 demonstrates the uniform anchoring of Co9S8 nanoflakes on Ni2P nanorods, consistent with the individual Ni2P nanorods and Co9S8 nanoflakes shown in Figure S1 (Supporting Information). Notably, the Ni2P nanorods, generated from VNF as a nickel source, seamlessly contact the foam, which promotes overall electron transmission of the integrated material and benefits charge transfer at the Ni2P@Co9S8 interface. The TEM image in Figure 2b further confirms the coexistence of Ni2P nanorods and Co9S8 nanoflakes, with the nanoflakes partially distributed at the edges of nanorods, consistent with the diameter size of FESEM results. The high‐resolution TEM (HRTEM) image in Figure 2c shows clear lattice fringes, with spacing lattices of 0.28 and 0.17 nm, corresponding to the (222) plane of Co9S8 crystal and (300) plane of Ni2P crystal respectively, consistent with the results of Figure S2 (Supporting Information), verifying the successful synthesis of the Ni2P@Co9S8 metallic heterostructure. The elemental mapping of Ni2P@Co9S8 is determined by HAADF‐STEM (Figure 2d), revealing the homogeneous distribution of Ni, P, Co, and S elements within the metallic heterostructure. As depicted in Figure 2e, apart from the VNF, the peaks emerging at 2θ = 29.7°, 31.2°, and 51.9° are indexed to the (311), (222) and (440) planes of Co9S8 (JCPDS file No. 02–1459), respectively. The peaks located at 44.5°, 47.3°, 54.2°, 54.9°, 66.2°, 72.6°, 74.6°, and 88.8° can be ascribed to (201), (210), (300), (211), (310), (311), (400), and (321) planes of Ni2P (JCPDS file No. 03–0953), respectively. The X‐ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of contrast samples are displayed in Figure S3 (Supporting Information).

Figure 2.

Characterizations of VNF supported catalysts. a) FESEM image, b) TEM image, and c) HRTEM image of Ni2P@Co9S8. d) Elemental mapping images of Ni, P, Co, and S and e) XRD pattern of Ni2P@Co9S8. XPS of f) Ni 2p for Ni2P@Co9S8 and Ni2P, g) Co 2p for Ni2P@Co9S8 and Co9S8, h) S 2p for Co9S8 and Ni2P@Co9S8 and i) P 2p for Ni2P@Co9S8 and Ni2P.

To further investigate the chemical states and elemental composition of the composites, X‐ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was conducted (Figure 2f–i). For Ni2P@Co9S8, the Ni 2p3/2 and Ni 2p1/2 peaks located at 855.4 and 873.6 eV with two satellites are fitted, indicating the Ni2+ oxidation state. Compared to Ni2P,[ 24 ] the Ni 2p peak is negatively shifted by 0.2 eV. Additionally, as depicted in Figure 2g, the Co 2p signals located at about 780.6 eV in Co 2p3/2 and 796.7 eV in Co 2p1/2 can be indexed to the spin‐orbit characteristics of Co3+, while the peaks at about 782.6 eV in Co 2p 3/2 and 797.5 eV in Co 2p1/2 are attributed to the characteristics of Co2+. Compared to the sample of Co9S8,[ 25 ] the XPS peaks of Co 2p of Ni2P@Co9S8 are respectively positively shifted by 0.3 eV, indicating a strong interaction between Co9S8 and Ni2P. Ni─S and Co─S bonds can be observed in Figure 2h. The down‐shift of Ni 2p and up‐shift of Co 2p binding energy reveal the electron transfer from Co9S8 to Ni2P, demonstrating the charge redistribution and strong electronic interactions among Ni2P nanorods and Co9S8 nanoflakes, which is beneficial to decreasing transfer resistance (R ct) and promoting the catalytic properties. The characterized peaks of P 2p in Ni2P@Co9S8 also positively shift toward higher binding energy compared to Ni2P (Figure 2i).[ 24 ] The shift of Ni and Co binding energy leads to the increase of the valence density, beneficial to the reaction with oxygen intermediates.

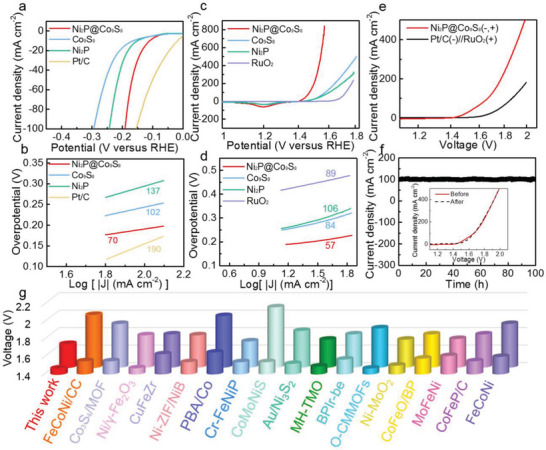

The electrocatalytic HER behavior of all as‐prepared samples was investigated in 1 M KOH solution using three‐electrode system. In Figure 3a and Figure S4 (Supporting Information), the linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves of Ni2P@Co9S8 with those of pure NF, VNF, Ni2P, Co9S8 and Pt/C‐NF at scan rate of 5 mV s−1 were compared. Ni2P@Co9S8 just delivers the smallest overpotential of 188 mV to reach the current density of 100 mA cm−2, indicating the significant effect of the cooperation Co9S8 nanoflakes and Ni2P nanorods on HER performance. The superior HER performance of Ni2P@Co9S8 can also be manifested through the Tafel slopes based on obtained LSV curves. As shown in Figure 3b and Figure S5 (Supporting Information), the Tafel slope value of Ni2P@Co9S8 is as low as 70 mV dec−1, much lower than those of contrast samples, suggesting more favorable reaction kinetics of Ni2P@Co9S8 towards HER. The mechanism of Ni2P@Co9S8 electrode can be considered as Volmer‐Heyrovsky process.

Figure 3.

Catalytic performances of VNF supported catalysts. a) LSV curves with iR‐compensation and b) Tafel slopes of Ni2P@Co9S8, Co9S8, Ni2P and Pt/C for HER in 1 m KOH. c) LSV curves with iR‐compensation and d) Tafel slopes of Ni2P@Co9S8, Co9S8, Ni2P and RuO2 for OER in 1 m KOH. e) LSV curves for electrocatalytic overall water splitting in 1 m KOH. f) The i‐ ‐t curve of Ni2P@Co9S8//Ni2P@Co9S8 at cell voltage of 1.66 V for 100 h. Inset: LSV curves before and after the durability measurement. g) Comparison of working voltage of Ni2P@Co9S8//Ni2P@Co9S8 and related alkaline electrolyzer at the current density of 10 and 100 mA cm−2 with those reported previously.

The values of double‐layer capacitance (C dl) were used to further assess the electrochemical active surface area (ECSA) in the non‐Faradic potential interval. As shown in Figures S6 and S7 (Supporting Information), the Ni2P@Co9S8 possesses the highest C dl value using cyclic voltammetry (CV) method of 91 mF cm−2, significantly larger than those of other catalysts, indicating that Ni2P@Co9S8 can achieve increased area density. To further confirm this, the roughness factor (RF) values were also assessed by dividing the determined C dl by 40 µF cm–2, which was usually regarded as C dl value of an ideally flat electrode in an alkaline solution,[ 26 ] and the results are shown in Table S1 (Supporting Information). The fact that the Ni2P@Co9S8 has the largest ECSA and RF values among these contrast samples suggests the high exposure of this hybrid structure, which is beneficial to sufficient contact with the electrolyte and enhanced H2O molecule adsorption ability. In addition, to eliminate the contribution from the roughness factor, as exhibited in Figure S8 (Supporting Information), the LSV curves were normalized with their corresponding ECSA values, consistent with Figure 3a, indicating the superior intrinsic activity of Ni2P@Co9S8.

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was utilized to gain insights into the reaction kinetics. As shown in Figure S9 (Supporting Information), the as‐prepared catalysts formed semicircles in the plane plots. Based on the equivalent circuit (inset of Figure S9, Supporting Information), the R ct value of Ni2P@Co9S8 is 2.79 Ω, which is lower than those of contrast samples (Table S2, Supporting Information). This observation indicates faster charge‐transfer kinetics and high efficiency of reaction at the interface of Ni2P@Co9S8 during the HER process. This improved performance may be attributed to the integration of Ni2P nanorods seamless on VNF, electron transfer from Co9S8 to Ni2P, and the more homogeneous distribution of Co9S8 nanoflakes on Ni2P nanorods. Furthermore, to evaluate the electrochemical HER durability of the Ni2P@Co9S8 structure, an i‐ t curve was recorded at the fixed potential of −0.188 V versus RHE for over 100 h in 1 m KOH (Figure S10, Supporting Information). There is no palpable attenuation in its corresponding current density of −100 mA cm−2, highlighting the superior structural stability during the HER process. In addition, the remarkable stability of Ni2P@Co9S8 as an electrode for HER was further confirmed by the LSV curves before and after 100 h test (inset of Figure S10, Supporting Information).

In addition to its excellent HER performance, the activity of Ni2P@Co9S8 towards OER was evaluated in the same electrolyte. As shown in Figure 3c and Figure S11 (Supporting Information), the acquired overpotential to obtain 100 mA cm−2 of Ni2P@Co9S8 is 253 mV, lower than the cases of Co9S8 (335 mV), Ni2P (333 mV), and VNF (387 mV) and other reported work,[ 4 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 18 ] indicating superior OER activity. In Figure 3d and Figure S12 (Supporting Information), the small Tafel slope value of 57 mV dec−1 for Ni2P@Co9S8 is lower than those values of Ni2P, Co9S8, VNF, NF, and RuO2‐NF, reflecting its fast reaction kinetics and superior OER catalytic performance. Based on the CV curves (Figure S13, Supporting Information), as shown in Figure S14 (Supporting Information), the Ni2P@Co9S8 shows the largest C dl value of 50 mF cm−2 among these samples, indicating that it can provide the largest electrochemical active surface areas and the most accessible active sites for the OER reaction. The RF values based on C dl values are depicted in Table S3 (Supporting Information), and the LSV curves after normalization are exhibited in Figure S15 (Supporting Information), suggesting the outstanding intrinsic activity of Ni2P@Co9S8 for the OER process. In addition, Ni2P@Co9S8 exhibits the smallest R ct as 2.51 Ω in Figure S16 and Table S4 (Supporting Information) among the as‐prepared samples, implying remarkable reaction kinetic in the OER process. In this work, the formation of metallic heterogeneous Ni2P@Co9S8 further reduced the activation energy of chemical reactions and accelerated the interfacial charge transfer dynamics, which is beneficial to optimizing intermediate adsorption, decreasing the R ct value and promoting the catalytic performance. This is consistent with the results of Tables S2 and S4 (Supporting Information).

As depicted in Figure S17 (Supporting Information), the Ni2P@Co9S8 demonstrates exceptional electrochemical durability for 100 h at fixed potential of 1.485 V versus RHE. Notably, the current density after 100 h has only a negligible attenuation. In the inset of Figure S17 (Supporting Information), moreover, there exists ignorable variation in the LSV curves between the original one and the one after 100 h test at 100 mA cm−2, which further confirms the stability of the structure. Based on the above electrochemical properties, the Ni2P@Co9S8 possesses a more exposed active site, enhanced intrinsic electrocatalytic performance, and favorable reaction kinetics, which strongly suggests that the Co9S8 can modulate the electron distribution of Ni2P, beneficial to achieving remarkable HER and OER behavior. The contrast samples, in contrast, require larger overpotentials than Ni2P@Co9S8 to attain high current densities for HER and OER, indicating that Ni2P@Co9S8 possesses excellent catalytic behavior.

To evaluate its catalytic activity for overall water decomposition, we assembled two‐electrode equipment using Ni2P@Co9S8 as both the anode and cathode, as it showed outstanding electrocatalytic properties for the HER and OER in an alkaline solution. As seen in Figure 3e, the Ni2P@Co9S8||Ni2P@Co9S8 can reach a current density of 10 mA cm−2 at 1.46 V, surpassing the commercial Pt/C║RuO2 catalyst. Additionally, the voltage window only slightly dropped after 100 h of electrolysis at 100 mA cm−2 (Figure 3f). After 100 h durability measurements, the LSV curve exhibits minimal change compared to the original one, indicating the stability of the structure (inset of Figure 3f). All these show that Ni2P@Co9S8 possesses attractive stability.

After the electrochemical process, as depicted in Figure S18a, (Supporting Information), the XRD pattern obtained after HER showed unobvious changes, suggesting the chemical stability during HER. As to the XRD pattern after OER, the characterization peaks are the same as the initial sample, but the intensity of some peaks located at 18.4°, 29.7°, 44.5°, and 51.9° is weaker than the initial sample, which may be attributed to the partial phase transition during OER. At the same time, to further illustrate the structural reconstruction during OER, we tested in‐situ Raman patterns at different voltages (Figure S18b, Supporting Information), and the characteristic peaks located at around 460 and 550 cm−1 effectively show that oxyhydroxides are formed during OER.[ 27a ] The charge regulation mechanism should be still applicable to reconstructed catalysts by modulating the active electronic states of active sites. In addition, the charge regulation of pre‐catalysts can optimize the electronic states of reactive species, which is beneficial for the structure reconstruction of catalysts during OER.[ 6 , 12 , 27 ] As presented in Tables S5–S7 (Supporting Information) and Figure 3g, the Ni2P@Co9S8 electrode exhibits superior parameters of Tafel slope and overpotentials for HER and OER and thus of cell voltage for overall water splitting performance, outperforming most reported non‐precious metal‐based electrocatalytic materials.[ 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ] Commonly, in order to meet the requirements for electrolysis of water under industrial alkaline conditions, the current density should achieve 200–400 mA cm−2 at the cell voltage of 1.8–2.4 V.[ 34 ] The Ni2P@Co9S8 just needs a cell voltage of 1.76 V to achieve the current density of 200 mA cm−2, outperforming Pt/C║RuO2 (1.99 V), suggesting Ni2P@Co9S8 can lower the energy cost during the hydrogen production than commercial catalyst. Besides, to reach the current density of 200 mA cm−2 , Ni2P@Co9S8 only needs 204 and 276 mV for HER and OER, respectively. We have compared the overpotentials required to achieve the current density of 200 mA cm−2 for HER, OER, and overall water splitting with reported catalysts (Tables S8–S10, Supporting Information). The results show that Ni2P@Co9S8 holds great potential for industrial water electrolysis.

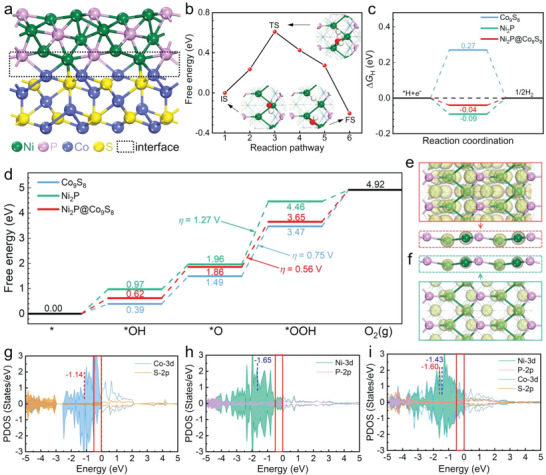

To investigate the outstanding HER and OER activities of Ni2P@Co9S8, the dissociation of water and adsorption of reaction intermediates on Ni2P, Co9S8, and Ni2P@Co9S8 were thoroughly examined using density functional theory (DFT) calculations (see Figure 4a; Figure S19, Supporting Information for models). In alkaline media, the kinetic rate of HER process is primarily governed by the energy barrier induced by the water dissociation process. As shown in Figure 4b, the energy barrier of water dissociation on the active Ni sites of Ni2P@Co9S8 (0.61 eV) is lower than that of Ni2P (0.79 eV, Figure S20, Supporting Information) and Co9S8 (0.99 eV, Figure S21, Supporting Information), suggesting that the heterostructure accelerates water dissociation for faster protons generation. Besides the water decomposition, the subsequent hydrogen adsorption also plays a vital role in determining the apparent alkaline HER activity, and the optimal ∆G H value is 0 eV. Figure 4c shows the free energy profile of HER and Figure S22 (Supporting Information) provides the corresponding configurations. Compared to Ni2P (0.27 eV) and Co9S8 (−0.09 eV), the ∆G H value of Ni2P@Co9S8 (−0.04 eV) is much closer to 0 eV, suggesting that the heterostructure exhibits enhanced HER activity.

Figure 4.

DFT analyses. a) Optimized structure of Ni2P@Co9S8. b) The energy barrier and reaction pathway of water dissociation on Ni2P@Co9S8. Insets are configurations of initial state (IS), transition state (TS), and final state (FS). Colar code: O, red; H, white. Free energy profiles of (c) HER and (d) OER on Co9S8, Ni2P, and Ni2P@Co9S8. Charge density analysis of e) Ni2P@Co9S8 and f) Ni2P at an isovalue of 0.15 e Å−1[.3] Dashed boxes side views of top layers for visual comparison between surface‐active Ni sites in Ni2P@Co9S8 and Ni2P. Projected density of state (PDOS) of g) Co9S8, h) Ni2P, and i) Ni2P@Co9S8, including the corresponding ε d values.

Regarding the OER activity, the ∆G values of reaction intermediates (*OH, *O, and *OOH) are effective descriptors. According to the free energy profile shown in Figure 4d and the configurations of *OH, *O, and *OOH shown in Figure S22 (Supporting Information), the elementary step of *O oxidation (*O + OH− → *OOH + e −) is the rate‐determining step (RDS) for both Ni2P and Co9S8, with ∆G RDS = 2.50 and 1.98 eV, respectively. Compared to Ni2P, interestingly, the active Ni sites remain the optimal active sites for Ni2P@Co9S8 but with much strong adsorption of reaction intermediates. The RDS is the elementary step of *O oxidation as well, but the corresponding ∆G RDS decreases to 1.79 eV. Consequently, the overpotential of OER of Ni2P@Co9S8 (η = 0.56 V) is lower than that of Co9S8 (η = 0.75 V) and Ni2P (η = 1.27 V), indicating that the heterostructure exhibits enhanced OER activity.

The unique electronic structure of Ni2P@Co9S8 is responsible for its optimal ∆G H value and also for its ∆G RDS and η values lower than pure Ni2P and Co9S8. Since both Ni2P and Ni2P@Co9S8 have the same active Ni sites, charge density analysis was conducted on the surface active Ni sites to see the inherent difference (Figure 4e,f). In reference to Ni2P, the charge densities of Ni sites in Ni2P@Co9S8 are clearly larger, suggesting the electronic regulation of Ni2P due to the formation of heterostructure. Such a difference can be further confirmed by the Bader charge analysis (Figure S23, Supporting Information), where smaller Bader charge values and thus lower oxidation state of active Ni sites in Ni2P@Co9S8 can be observed. This agrees well with the XPS results shown in Figure 2f that the valence state of Ni atoms in Ni2P@Co9S8 is lower than that in Ni2P. Accordingly, the reduction states of P and S atoms should also change to maintain the electric neutrality of the whole system. To further clarify the charge transfer, the Bader charge analysis of the topmost Co and S atoms in Co9S8 and Ni2P@Co9S8 was performed (Figure S24, Supporting Information). With Ni2P@Co9S8 formation, the average Bader charge of three topmost Co atoms changes from +0.37|e| to +0.47|e|, while it changes from +0.48|e| to +0.52|e| for three topmost S atoms. This indicates that the charge variation of non‐metal atoms should be relatively negligible in comparison with mental atoms. For a deeper understanding, the PDOS figures of Ni2P, Co9S8, and Ni2P@Co9S8 are depicted. From Figure 4g,i, a significant charge density redistribution can be observed in Ni2P@Co9S8, qualitatively illustrating the redistribution of electronic states induced by the charge transfer. In Figure 4i, the strong hybridization between Co‐3d and P‐2p orbital can be found in the deep energy level (≈−3.5 eV), contributing to the formation of a metallic heterostructure of Ni2P@Co9S8. Moreover, around the Fermi level (−0.5–0 eV, red boxes), the active electronic states of active Ni sites in Ni2P@Co9S8 are highly increased along with the increased d‐band center (ε d; from −1.65 to −1.43 eV) compared to Ni2P (Figure 4h), suggesting more active electrons in Ni2P of Ni2P@Co9S8, which is highly conductive to optimizing the charge transfer and then improving the water splitting performance. Meanwhile, owing to the electronic regulation between Co─Co bonds and active Ni atoms, the active electronic states of Co sites around the Fermi level decrease, and ε d decreases from −1.14 to −1.60 eV. Hence, compared to Ni2P and Co9S8, the Co─Co bonds in Ni2P@Co9S8 can regulate the intrinsic charge distribution of active Ni sites to further optimize the HER/OER performance.

3. Conclusion

In summary, we design a bifunctional electrocatalyst of Ni2P@Co9S8 composite conductor to perform highly efficient alkaline water electrolysis with ultralow overpotential at large current density. The constructed Ni2P@Co9S8║Ni2P@Co9S8 electrolyzer achieved an ultralow cell voltage of 1.66 V at a current density of 100 mA cm−2 and maintained operation stability over 100 h, which just requires low overpotentials of 188 and 253 mV to achieve HER and OER processes at the current density of 100 mA cm−2 in alkaline condition, respectively. The active electronic states of Ni around the Fermi‐level are modulated in the Ni2P@Co9S8 metallic heterostructure by the Co─Co bond, which contributes to the enhanced overall water‐splitting performance. Remarkably, the ultralow cell voltage of 1.66 V to achieve 100 mA cm−2 is contributed from the enhanced accessible surface area, faster electron transitions, and complementary function of different components of the Ni2P@Co9S8 metallic heterostructure. Our work provides a convenient and concise strategy for the design of large current‐density transition metal‐based catalysts in overall water splitting.

4. Experimental Section

Synthesis of VNF, Ni2P, Co9S8, and Ni2P@Co9S8 Electrocatalysts

] Typically, NF (30 mm × 20 mm × 1 mm) was treated through cleaning sequentially with solvents of acetone, 3 m HCl solution, distilled water, and absolute ethanol to ensure a clean surface.

After washing, the NF was immersed in the solution containing 0.076 g thiourea (1 mmol) and methanol (20 ml) in an oven at 180 °C for 6 h. The obtained sample was washed thoroughly with water and then placed in a vacuum oven at 60 °C for 8 h. After cooling down the autoclave at room temperature, the VNF was placed in 1 m KOH solution for 3 h, there will exist Ni(OH)2 nanoflakes upon VNF. After that, the Ni(OH)2 supported on VNF was placed in a tube furnace, with 0.5 g NaH2PO2 placed at the upstream side and near the above tube furnace. After flushing with argon gas, the furnace was heated up to 300 °C at a ramping rate of 1°C min−1. When the heating process was over, the temperature of 300 °C was held for 30 min to convert Ni(OH)2 to Ni2P. Then the Ni2P on VNF was submerged in a 100 mL Teflon‐lined stainless autoclave filled with 0.0474 g CoCl2·6H2O, 0.0496 g Na2S2O3 and 40 mL H2O and then heated in an oven at 150°C for 12 h. The resulting material was further treated with distilled water three times and dried in a vacuum at 60 °C. Finally, the Ni2P@Co9S8 sample was obtained. In addition, the VNF was directly immersed in 40 mL deionized water containing 0.0474 g CoCl2·6H2O and 0.0496 g Na2S2O3 in an oven at 150 °C for 12 h to obtain Co9S8. For the Pt/C and RuO2 electrodes, the catalysts (2 mg) were dispersed in a mixture of 960 µL ethanol and 40 µL Nafion solution (20 wt%), respectively. The 1 mL Pt/C and RuO2 inks were dropped into NF to obtain Pt/C‐NF and RuO2‐NF. The loading mass of Pt/C, RuO2, and Ni2P@Co9S8 are 1.91, 1.93, and 1.87 mg cm−2, respectively.

Material Characterization

FESEM (JEOL JSM‐6700F, 15 keV) and TEM (JEOL JEM‐2100F, 200 keV) were used to further make sure the morphology and microstructure of as‐prepared electrodes. To analyze the material phase and crystallinity, XRD patterns were measured with the assistance of D8 FOCUS (powder) and D/max 2500 pc diffractometer (bulk) with Cu Kα radiation. XPS was collected using an ESCALAB Mk II (vacuum generator) spectrometer with an Al anode. All binding energies were calibrated via referencing to C 1s binding energy (284.8 eV). The Raman spectroscopy characterization was obtained with a Renishaw Raman spectrometer using an intensity of 0.05 mW with a wavelength of 532 nm as the exciting source.

Electrochemical Characterization

The electrochemical characterization was carried out in a conventional three electrode electrochemical cell consisting of a graphite rod as a counter electrode, a standard calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode and working electrode, and in alkaline solution (1 m KOH pH = 13.6) controlled by the CHI Instruments 660E electrochemical workstation. For all electrochemical measurements, the obtained SCE potential was converted into RHE based on the following formula: E RHE = E SCE + 0.244 + 0.0592 × pH. All of the data were iR‐calibrated in view of the equation: E compensated = E measured‐ iR s (R s is the solution resistance based on the result of EIS). LSV curves of HER and OER processes were recorded at a scan rate of 5 mV s−1, and the scan rate of LSV curves for overall water splitting is 1 mV s−1. The ECSA was characterized by double‐layer capacitances based on CV curve measurements under different scan rates. The EIS spectra were recorded with fixed overpotentials set at −0.26 V versus RHE for HER and 1.53 V versus RHE for OER with the frequency range from 10[ 5 ] to 10−3 HZ (amplitude of 10 mV). The i–t curves were recorded for 100 h at a constant applied potential of −0.188 V versus RHE for HER and 1.485 V versus RHE for OER, respectively.

Computational Details

Spin‐polarized DFT calculations were performed within the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP), using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method, the generalized gradient approximation of Perdew‐Burke‐Ernzerhof (GGA‐PBE) functional, and the plane‐wave basis set with an energy cutoff of 450 eV.[ 35 ] The Brillouin zones were sampled by a gamma‐centered 2 × 4 × 1 k point mesh, while a dense 6 × 12 × 1 mesh was used for electronic property calculations. The convergence criteria of structure optimization were set to be 10−4 eV for the electronic energy and 0.02 eV Å−1 for the forces on each atom. The slab models of Co9S8(111) and Ni2P(100) were built to simulate pure Co9S8 and Ni2P (Figure S19, Supporting Information), respectively. The mismatch between Co9S8(111) and Ni2P(100) is ≈3.6%, and subsequently, the Ni2P(100)@Co9S8(111) slab was constructed to explore the HER and OER activity of the Ni2P@Co9S8 heterostructure (Figure 4a). For all slab models, the vacuum space over 15 Å was added along the z‐axis to eliminate the interactions between neighboring models. The DFT‐D3 method was selected for the van der Waals correction.[ 36 ] The minimum energy paths and transition states (TS) were determined by the climbing image nudged elastic band (CI‐NEB) method implemented in VASP.[ 37 ]

The Gibbs free energy of the intermediates (*H, *OH, *O, *OOH) during the HER and OER process was determined by,

| (1) |

where E ads is the adsorption energy of the intermediate, ∆E ZPE is the zero‐point energy difference between the adsorption and gas states, T is the temperature (298.15 K), and ∆S is the entropy change between the adsorption and gas phases. For intermediates, ∆E ZPE and S were obtained from the vibrational frequency calculations with harmonic approximation, and the vibrational modes of intermediates were computed with the fixed slabs. For H2 and H2O molecules, ∆E ZPE was computed in a 14×15×16 Å[ 3 ] cell, while S at 298.15 K was taken from the handbook.[ 38 ]

The changes in the adsorption energy for *H, *OH, *O and *OOH were computed on the basis of DFT ground state energies as,

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

where * denotes the adsorption site on a substrate surface.

The OER process in an alkaline medium usually follows:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

In addition,

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

The overpotential (η), an important parameter to evaluate the OER activity, was computed as,

| (14) |

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions

X.Z. and X.Y. contributed equally to this work. Y.Z., E.S. conceived the research. X.Z. carried out the synthesis and performed materials characterization and electrochemical measurements. E.S. proposed the active electronic states and X.Y. carried out the theoretical calculations. Y.Z, E.S., C.S., and Q.J. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Supporting information

Supporting Information

Acknowledgements

All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 51871107, 51631004, and 52130101), the Top‐notch Young Talent Program of China (W02070051), the Chang Jiang Scholar Program of China (Q2016064), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, the Program for Innovative Research Team (in Science and Technology) in University of Jilin Province, and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (21ZR1472900, 22ZR1471600). C.S. acknowledged the support of the Natural Sciences & Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the University of Toronto, and the Digital Research Alliance of Canada for enabling DFT simulations. E.S. is grateful for support through key research and development project from Shanghai Jiao Tong University‐Shaoxing Institute of new Energy and Molecular Engineering.

Zhu X., Yao X., Lang X., Liu J., Singh C.‐V., Song E., Zhu Y., Jiang Q., Charge Self‐Regulation of Metallic Heterostructure Ni2P@Co9S8 for Alkaline Water Electrolysis with Ultralow Overpotential at Large Current Density. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2303682. 10.1002/advs.202303682

Contributor Information

Chandra‐Veer Singh, Email: chandraveer.singh@utoronto.ca.

Erhong Song, Email: ehsong@mail.sic.ac.cn.

Yongfu Zhu, Email: yfzhu@jlu.edu.cn.

Qing Jiang, Email: jiangq@jlu.edu.cn.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.a) Turner J. A., Science 2004, 305, 972; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Roger I., Shipman M. A., Symes M. D., Nat. Rev. Chem. 2017, 1, 0003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Chen W., Wu B., Wang Y., Zhou W., Li Y., Liu T., Xie C., Xu L., Du S., Song M., Wang D., Liu Y., Li Y., Liu J., Zou Y., Chen R., Chen C., Zheng J., Li Y., Chen J., Wang S., Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 6428; [Google Scholar]; b) Cheng N., Stambula S., Wang D., Banis M. N., Liu J., Riese A., Xiao B., Li R., Sham T. K., Liu L. M., Botton G. A., Sun X., Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13638; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hu Q., Gao K., Wang X., Zheng H., Cao J., Mi L., Huo Q., Yang H., Liu J., He C., C. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Xiao Z., Wang Y., Huang Y.‐C., Wei Z., Dong C.‐L., Ma J., Shen S., Li Y., Wang S., Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 2563; [Google Scholar]; b) Sui X., Zhang L., Li J., Doyle‐Davis K., Li R., Wang Z., Sun X., Adv. Energy Mater. 2022, 12, 2102556. [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Yao R.‐Q., Shi H., Wan W.‐B., Wen Z., Lang X. Y., Jiang Q., Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1907214; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Huang Z. F., Song J., Du Y., Xi S., Dou S., Nsanzimana J. M. V., Wang C., Xu Z. J., Wang X., Nat. Energy 2019, 4, 329; [Google Scholar]; c) Zhou H., Yu F., Zhu Q., Sun J., Qin F., Yu L., Bao J., Yu Y., Chen S., Ren Z., Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 2858. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a) Lu Z., Chen Z. W., Singh C. V., Matter 2020, 3, 1318; [Google Scholar]; b) Zhou Y., Song E., Chen W., Segre C. U., Zhou J., Lin Y. C., Zhu C., Ma R., Liu P., Chu S., Thomas T., Yang M., Liu Q., Suenaga K., Liu Z., Liu J., Wang J., Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2003484; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Shi H., Zhou Y. T., Yao R. Q., Wan W. B., Ge X., Zhang W., Wen Z., Lang X. Y., Zheng W. T., Jiang Q., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2940; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Song J., Jin Y. Q., Zhang L., Dong P., Li J., Xie F., Zhang H., Chen J., Jin Y., Meng H., Sun X., Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2003511. [Google Scholar]

- 6.a) Wang Z., Chen J., Song E., Wang N., Dong J., Zhang X., Ajayan P. M., Yao W., Wang C., Liu J., Shen J., Ye M., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5960; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu L., Wu J., Wu L., Ye M., Liu X., Wang Q., Hou S., Lu P., Sun L., Zheng J., Xing L., Gu L., Jiang X., Xie L., Jiao L., Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 1108; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Voiry D., Fullon R., Yang J., De Carvalho Castro E Silva C., Kappera R., Bozkurt I., Kaplan D., Lagos M. J., Batson P. E., Gupta G., Mohite A. D., Dong L., Er D., Shenoy V. B., Asefa T., Chhowalla M., Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a) Liu P., Chen B., Liang C., Yao W., Cui Y., Hu S., Zou P., Zhang H., Fan H. J., Yang C., Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2007377; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li H., Tsai C., Koh A. L., Cai L., Contryman A. W., Fragapane A. H., Zhao J., Han H. S., Manoharan H. C., Abild‐Pedersen F., Nørskov J. K., Zheng X., Nat. Mater. 2016, 15, 48; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Zhou Y., Zhang J., Song E., Lin J., Zhou J., Suenaga K., Zhou W., Liu Z., Liu J., Lou J., Fan H. J., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a) He J., Liu Y., Huang Y., Li H., Zou Y., Dong C.‐L., Wang S., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2009245; [Google Scholar]; b) Lei Y., Xu T., Ye S., Zheng L., Liao P., Xiong W., Hu J., Wang Y., Wang J., Ren X., He C., Zhang Q., Liu J., Sun X., Appl. Catal. B 2021, 285, 119809. [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Sun Y., Xu K., Wei Z., Li H., Zhang T., Li X., Cai W., Ma J., Fan H. J., Li Y., Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1802121; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yu L., Zhu Q., Song S., Mcelhenny B., Wang D., Wu C., Qin Z., Bao J., Yu Y., Chen S., Ren Z., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5106; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hu Q., Han Z., Wang X., Li G., Wang Z., Huang X., Yang H., Ren X., Zhang Q., Liu J., He C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 19054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a) Song Y. R., Zhang X. M., Zhang Y. X., Zhai P. L., Li Z. W., Jin D. F., Cao J. Q., Wang C., Zhang B., Gao J. F., Sun L. C., Hou J. G., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202200946; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Kim Y. T., Lopes P. P., Park S.‐A., Lee A. Y., Lim J., Lee H., Back S., Jung Y., Danilovic N., Stamenkovic V., Erlebacher J., Snyder J., Markovic N. M., Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1449; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Chen G. F., Ma T. Y., Liu Z. Q., Li N., Su Y.‐Z., Davey K., Qiao S. Z., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 3314. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Zhai P., Zhang Y., Wu Y., Gao J., Zhang B., Cao S., Zhang Y., Li Z., Sun L., Hou J., Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5462; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Song F., Li W., Yang J., Han G., Liao P., Sun Y., Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Wu T., Song E., Zhang S., Luo M., Zhao C., Zhao W., Liu J., Huang F., Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2108505; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yang C. C., Zai S. F., Zhou Y. T., Du L., Jiang Q., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1901949; [Google Scholar]; c) Zai S. F., Gao X. Y., Yang C. C., Jiang Q., Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2101266. [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Zhang J., Wang T., Pohl D., Rellinghaus B., Dong R., Liu S., Zhuang X., Feng X., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6702; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jiao Y., Zheng Y., Davey K., Qiao S. Z., Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16130; [Google Scholar]; c) Zhang J., Wang T., Liu P., Liao Z., Liu S., Zhuang X., Chen M., Zschech E., Feng X., Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Sun H., Chen L., Lian Y., Yang W., Lin L., Chen Y., Xu J., Wang D., Yang X., Rümmerli M. H., Guo J., Zhong J., Deng Z., Jiao Y., Peng Y., Qiao S., Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2006784; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lei C., Wang Y., Hou Y., Liu P., Yang J., Zhang T., Zhuang X., Chen M., Yang B., Lei L., Yuan C., Qiu M., Feng X., Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 149; [Google Scholar]; c) Zheng Y., Jiao Y., Zhu Y., Li L. H., Han Y., Chen Y., Jaroniec M., Qiao S. Z., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 16174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a) Zhang J., Wang T., Liu P., Liu S., Dong R., Zhuang X., Chen M., Feng X., Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 2789; [Google Scholar]; b) Zheng Y., Jiao Y., Vasileff A., Qiao S. Z., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 7568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.a) Lu X. F., Yu L., Lou W., Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav6009; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Huang Y., Zhang S. L., Lu X. F., Wu Z. P., Luan D., Lou X. W. (.D.)., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 11841; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Feng J. X., Wu J. Q., Tong Y. X., Li G. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Li X., Zhang H., Hu Q., Zhou W., Shao J., Jiang X., Feng C., Yang H., He C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202300478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zeng K., Zhang D., Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2010, 36, 307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Zhang X., Li J., Yang Y., Zhang S., Zhu H., Zhu X., Xing H., Zhang Y., Huang B., Guo S., Wang E., Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1803551; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhao D., Sun K., Cheong W. C., Zheng L., Zhang C., Liu S., Cao X., Wu K., Pan Y., Zhuang Z., Hu B., Wang D., Peng Q., Chen C., Li Y., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 8982; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gu W., Gan L., Zhang X., Wang E., Wang J., Nano Energy 2017, 34, 421; [Google Scholar]; d) Yang Y., Luo M., Xing Y., Wang S., Zhang W., Lv F., Li Y., Zhang Y., Wang W., Guo S., Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1706085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a) Shi Y., Zhang B., Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 1529; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chang J., Feng L., Liu C., Xing W., Hu X., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang T., Yang K., Wang C., Li S., Zhang Q., Chang X., Li J., Li S., Jia S., Wang J., Fu L., Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1801690. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu X., Hu Q., Zhu B., Li G., Fan L., Chai X., Zhang Q., Liu J., He C., Small 2018, 14, 1802755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. You B., Zhang Y., Jiao Y., Davey K., Qiao S. Z., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 11796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xu J., Cui J., Guo C., Zhao Z., Jiang R., Xu S., Zhuang Z., Huang Y., Wang L., Li Y., Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu M., Wang J.‐A., Klysubun W., Wang G. G., Sattayaporn S., Li F., Cai Y.‐W., Zhang F., Yu J., Yang Y., Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhuo S., Shi Y., Liu L., Li R., Shi L., Anjum D. H., Han Y., Wang P., Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mccrory C. C. L., Jung S., Ferrer I. M., Chatman S. M., Peters J. C., Jaramillo T. F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 4347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.a) Moysiadou A., Lee S., Hsu C. S., Chen H. M., Hu X., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 11901; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Guo X., Song E., Zhao W., Xu S., Zhao W., Lei Y., Fang Y., Liu J., Huang F., Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5954; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Gao X. R., Liu X. M., Zang W. J., Dong H. L., Pang Y. J., Kou Z. K., Wang P. Y., Pan Z. H., Wei S. R., Mu S. C., Wang J., Nano Energy 2020, 78, 105355; [Google Scholar]; d) Chang K., Tran D. T., Wang J., Prabhakaran S., Kim D. H., Kim N. H., Lee J. H., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2113224; [Google Scholar]; e) Sun Y., Mao K., Shen Q., Zhao L., Shi C., Li X., Gao Y., Li C., Xu K., Xie Y., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2109792. [Google Scholar]

- 28.a) Hao S., Chen L., Yu C., Yang B., Li Z., Hou Y., Lei L., Zhang X., ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 952; [Google Scholar]; b) Sun S., Zhou X., Cong B., Hong W., Chen G., ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 9086; [Google Scholar]; c) Fei H., Dong J., Feng Y., Allen C. S., Wan C., Volosskiy B., Li M., Zhao Z., Wang Y., Sun H., An P., Chen W., uo Z., Lee C., Chen D., Shakir I., Liu M., Hu T., Li Y., Kirkland A. I., Duan X., Huang Y., Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 63. [Google Scholar]

- 29.a) Han X., He G., He Y., Zhang J., Zheng X., Li L., Zhong C., Hu W., Deng Y., Ma T.‐Y., Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1870043; [Google Scholar]; b) Wu K., Sun K., Liu S., Cheong W. C., Chen Z., Zhang C., Pan Y., Cheng Y., Zhuang Z., Wei X., Wang Y., Zheng L., Zhang Q., Wang D., Peng Q., Chen C., Li Y., Nano Energy 2021, 80, 105467; [Google Scholar]; c) Wu Z. P., Zhang H., Zuo S., Wang Y., Zhang S. L., Zhang J., Zang S. Q., Lou X. W. (.D.)., Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2103004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Xiong Q., Wang Y., Liu P. F., Zheng L.‐R., Wang G., Yang H. G., Wong P.‐K., Zhang H., Zhao H., Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1801450; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.a) Zhang Q., Bedford N. M., Pan J., Lu X., Amal R., Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1901312; [Google Scholar]; b) Liu T., Li P., Yao N., Kong T., Cheng G., Chen S., Luo W., Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806672; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Shi H., Liang H., Ming F., Wang Z., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 573; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Yu L., Zhou H., Sun J., Qin F., Yu F., Bao J., Yu Y., Chen S., Ren Z., Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 1820. [Google Scholar]

- 31.a) Zheng J., Chen X., Zhong X., Li S., Liu T., Zhuang G., Li X., Deng S., Mei D., Wang J. G., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1704169; [Google Scholar]; b) Suryanto B. H. R., Wang Y., Hocking R. K., Adamson W., Zhao C., Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5599; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kim Y., Kim D., Lee J., Lee L. Y. S., Ng D. K. P., Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2103290; [Google Scholar]; d) Liu Y., Chen Y., Tian Y., Sakthivel T., Liu H., Guo S., Zeng H., Dai Z., Adv. Mater. 2022, 34, 2203615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.a) Zhuang L., Jia Y., Liu H., Li Z., Li M., Zhang L., Wang X., Yang D., Zhu Z., Yao X., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 14664; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Li X., Liu C., Fang Z., Xu L., Lu C., Hou W., Small 2022, 18, 2104354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.a) Liu H., Cheng J., He W., Li Y., Mao J., Zheng X., Chen C., Cui C., Hao Q., Appl. Catal. B 2022, 304, 120935; [Google Scholar]; b) Huang L., Chen D., Luo G., Lu Y. R., Chen C., Zou Y., Dong C. L., Li Y., Wang S., Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1901439; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Xu H., Fei B., Cai G., Ha Y., Liu J., Jia H., Zhang J., Liu M., Wu R., Adv. Energy Mater. 2020, 10, 1902714; [Google Scholar]; d) Wang Y., Ma J., Wang J., Chen S., Wang H., Zhang J., Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1802939; [Google Scholar]; e) Wu Y., Tao X., Qing Y., Xu H., Yang F., Luo S., Tian C., Liu M., Lu X., Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1900178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.a) Yang Y., Yao H., Yu Z., Islam S. M., He H., Yuan M., Yue Y., Xu K., Hao W., Sun G., Li H., Ma S., Zapol P., Kanatzidis M. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 10417; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Menezes P. W., Panda C., Garai S., Walter C., Guiet A., Driess M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 15237; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Pan Y., Sun K., Liu S., Cao X., Wu K., Cheong W. C., Chen Z., Wang Y., Li Y., Liu Y., Wang D., Peng Q., Chen C., Li Y., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 2610; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Gao X., Zhang H., Li Q., Yu X., Hong Z., Zhang X., Liang C., Lin Z., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 6290; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Hou Y., Lohe M. R., Zhang J., Liu S., Zhuang X., Feng X., Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 478. [Google Scholar]

- 35.a) Blochl P. E., Phys Rev B Condens Matter 1994, 50, 17953; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Perdew J. P., Burke K., Ernzerhof M., Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Grimme S., J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Henkelman G., Jónsson H., J. Chem. Phys. 2000, 113, 9978. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Haynes W. M., CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Florida: 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.