Abstract

Aims

Aging is a dominant driver of atherosclerosis and induces a series of immunological alterations, called immunosenescence. Given the demographic shift towards elderly, elucidating the unknown impact of aging on the immunological landscape in atherosclerosis is highly relevant. While the young Western diet-fed Ldlr-deficient (Ldlr−/−) mouse is a widely used model to study atherosclerosis, it does not reflect the gradual plaque progression in the context of an aging immune system as occurs in humans.

Methods and results

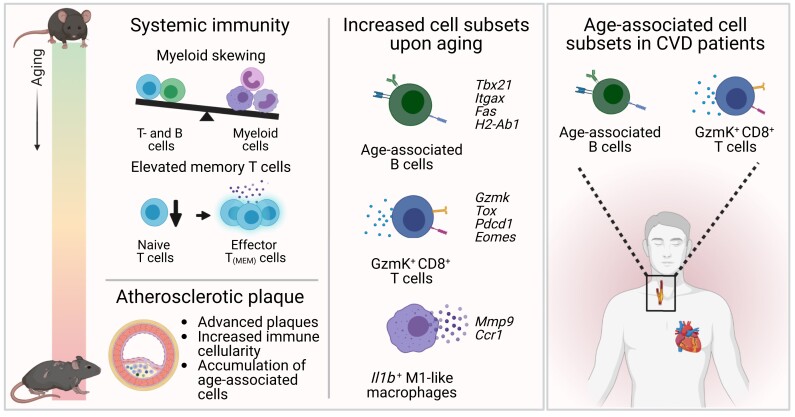

Here, we show that aging promotes advanced atherosclerosis in chow diet-fed Ldlr−/− mice, with increased incidence of calcification and cholesterol crystals. We observed systemic immunosenescence, including myeloid skewing and T-cells with more extreme effector phenotypes. Using a combination of single-cell RNA-sequencing and flow cytometry on aortic leucocytes of young vs. aged Ldlr−/− mice, we show age-related shifts in expression of genes involved in atherogenic processes, such as cellular activation and cytokine production. We identified age-associated cells with pro-inflammatory features, including GzmK+CD8+ T-cells and previously in atherosclerosis undefined CD11b+CD11c+T-bet+ age-associated B-cells (ABCs). ABCs of Ldlr−/− mice showed high expression of genes involved in plasma cell differentiation, co-stimulation, and antigen presentation. In vitro studies supported that ABCs are highly potent antigen-presenting cells. In cardiovascular disease patients, we confirmed the presence of these age-associated T- and B-cells in atherosclerotic plaques and blood.

Conclusions

Collectively, we are the first to provide comprehensive profiling of aged immunity in atherosclerotic mice and reveal the emergence of age-associated T- and B-cells in the atherosclerotic aorta. Further research into age-associated immunity may contribute to novel diagnostic and therapeutic tools to combat cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, Atherosclerosis, Aging, Immunology, Immunosenescence

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Time of primary review: 33 days

1. Introduction

Aging is a complex process that gradually affects multiple physiological systems in the body. During aging, cell-intrinsic and microenvironmental changes of the bone marrow cause haematopoietic stem cells and progenitors to deviate from lymphopoiesis and preferentially differentiate towards myeloid lineages, resulting in expansion of the myeloid cell pool. Concurrently, age-induced structural changes of lymphoid organs cause a strong reduction in peripheral lymphocytes.1,2 Together with a gradual functional decline of immune cells, these age-related changes of the immune system are termed ‘immunosenescence’.3 Immunosenescence can promote a chronic state of low-grade inflammation called ‘inflammaging’.4 As a result, the elderly are more susceptible to infections, autoimmune diseases, and chronic vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis, which is the main underlying cause of cardiovascular disease (CVD).3,5 Aging is actually one of the main risk factors for CVD, as the prevalence and consequent mortality associated with CVD increase with age. In 2019, CVD accounted for more than one-third (3.4 million) of total deaths in the global population aged 60–69 and up to nearly half (11.5 million) of total deaths in age groups of 70 years and older.6 Together with a large demographic shift towards an older population, it has become a major public health priority to improve our understanding of age-associated maladaptive immunity as a cause of disease susceptibility and mortality.

Both myeloid and lymphoid cells contribute to the formation of atherosclerotic plaques in the arterial wall7, and transcriptome analyses of aortic leucocytes in murine models of atherosclerosis have revealed high diversity amongst immune cells in the plaque.8,9 The vast majority of experimental studies investigating immunity and immune modulating therapies in atherosclerosis has been performed in relatively young animals fed with a Western diet (3–6 months of age, resembling adolescents aged 20–30 years), whereas CVD patients receiving treatment are often of advanced age (∼60 years at first coronary artery disease diagnosis)10 and have an aged immune system, which limits the translation of experimental findings to the patient. In addition, accelerated development of Western diet-induced atherosclerosis in young mice does not resemble the gradual process of plaque development and progression in humans. It is therefore of utmost importance to take aging into consideration in experimental atherosclerosis studies. To obtain in-depth insight in the atherosclerotic immune responses that arise upon aging, we profiled age-associated systemic immunity by a high throughput analysis and investigated atherosclerotic lesion development in young (5 months) and aged (22 months, correlating with humans of ∼60 years of age) low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient (Ldlr−/−) mice. Using single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-seq), we compared the transcriptomic profile of aortic leucocytes from chow diet- and Western diet-fed young Ldlr−/− mice to chow diet-fed aged atherosclerotic Ldlr−/− mice and revealed age-associated immune cell subsets, including age-associated GzmK+CD8+ T-cells and age-associated B-cells (ABCs), in atherosclerotic mice and cardiovascular disease patients.

2. Methods

A detailed version of the methods is available in the Supplementary material online.

2.1. Animals

All animal experiments were approved by the Leiden University Animal Ethics Committee and were performed according to the guidelines of the European Parliament Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament. Female C57BL/6J, Ldlr−/−, and Apoe−/− mice (if not specified elsewhere: young, 3 months or aged, 20 months old), and OTII mice (4 months old) on a C57Bl/6J genetic background were bred and aged in-house and kept under standard laboratory conditions. C57BL/6J, and Apoe−/−, and OTII mice were fed with a regular chow diet (CD). Aged Ldlr−/− mice were fed with a CD, while young mice were fed with a CD or a Western diet (WD) containing 0.25% cholesterol and 15% cocoa butter (Special Diet Services, Witham, Essex, UK) for 10 weeks. At the end of experiment, mice were terminally anaesthetized by a subcutaneous injection of a cocktail contain ketamine (100 mg/kg), atropine (50 μg/mL), and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Mice were bled by retro-orbital bleeding, and tissues were harvested after in situ perfusion with phosphate buffered saline.

2.2. Patient population

Human atherosclerotic plaques (n = 9–15) and paired blood samples were obtained from patients undergoing a carotid endarterectomy procedure at the Haaglanden Medical Center, location Westeinde (The Hague, The Netherlands). The study was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the HMC (NL71516.058.19). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and all patients gave written informed consent at the start of the study.

2.3. Serum cholesterol, triglyceride, and immunoglobulin measurements

To determine total cholesterol and triglyceride levels, mouse serum samples underwent enzymatic colourimetric procedures (Roche/Hitachi, Mannheim, Germany) with precipath (Roche/Hitachi) as an internal standard. Total serum titres of IgM and oxLDL-specific IgM were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as previously described.11

2.4. Histology

Hearts and aortas were embedded in O.C.T. compound (Sakura) and snap-frozen. To determine lesion size, cryosections (10 μm) of the aortic root were stained with Oil-Red-O and haematoxylin (Sigma-Aldrich). Collagen content was quantified using a Masson’s trichrome staining (Sigma-Aldrich). The necrotic core was defined as the acellular, debris-rich lesion area as percentage of total plaque area. Corresponding sections on separate slides were stained for monocyte/macrophage content with a MOMA-2 antibody (1:1000, AbD Serotec) followed by secondary antibody. We categorized cholesterol crystallization of atherosclerotic lesions in the aortic root on a scale of 0 (no cholesterol crystallization) to 3 (>75% of the lesion area contains crystalline cholesterol). The presence of calcification was manually scored based on morphology. Analysis and scoring were performed blinded. Mice with bicuspid aortic valves were excluded from histological analyses (n = 3). Pictures were taken with a Mikrocam II (Besser) linked to a Leica DM6000 Microscope. Stained sections were manually analysed with ImageJ software.

2.5. Human tissue processing

Single cell suspensions of human carotid plaques were obtained as previously described.12

2.6. Flow cytometry

Immunostaining was performed as previously described13 on single cell suspensions derived from murine blood, spleen, and aortas, and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and plaques to characterize immune cells. Living cells were selected using Fixable Viability Dye eFluor™ 780 (1:2000, eBioscience), and different cell populations were defined using anti-mouse and anti-human fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (Major Resources Table in the Supplementary material). Antibody staining of transcription factors and cytokines was performed using transcription factor fixation/permeabilization concentrate and diluent solutions and cytofix/permeabilization solutions, respectively (BD Biosciences). Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis was performed on a Cytoflex S (Beckman Coulter), and the acquired data were analysed using FlowJo software.

2.7. Aortic CD45+ cell isolation for single-cell RNA-sequencing

Atherosclerotic aortic arches, from which perivascular adipose tissue was removed, were isolated from young WD-fed (young WD) Ldlr−/− mice (4–5 months old; n = 29) and old CD-fed (old CD) Ldlr−/− mice (22 months old; n = 12) and enzymatically digested. Single cell suspensions were stained with Fixable Viability Dye eFluor™ 780 (1:2000, eBioscience) and CD45-PE (1:500, clone 30-F11, Biolegend). After removing doublets, alive CD45+ cells were sorted (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1A) using a FACS Aria II SORP (BD Biosciences) and loaded on a Chromium Single Cell instrument (10x Genomics) to prepare scRNA-seq libraries. Sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq2500, and the digital expression matrix was generated by de-multiplexing barcode processing and gene unique molecular index (UMI) counting using the Cell Ranger v3.0 (aged) and v6.0 (young) pipeline (10x Genomics). Data quality is provided in Supplementary material online, Figure S1B–D.

2.8. Single-cell data processing and integrative analysis

Digital expression matrices were analysed using the Seurat package in R. Low-quality cells were excluded by setting thresholds for unique gene count reads and mitochondrial gene expression (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1C). Using the DoubletDecon approach,14 doublets were removed. Single-cell transcriptomes of CD45+ cells isolated from aortas of young non-atherosclerotic chow diet-fed Ldlr−/− mice (2 months old, n = 9; GSM2882368)9 were loaded and filtered from doublets and low-quality cells.

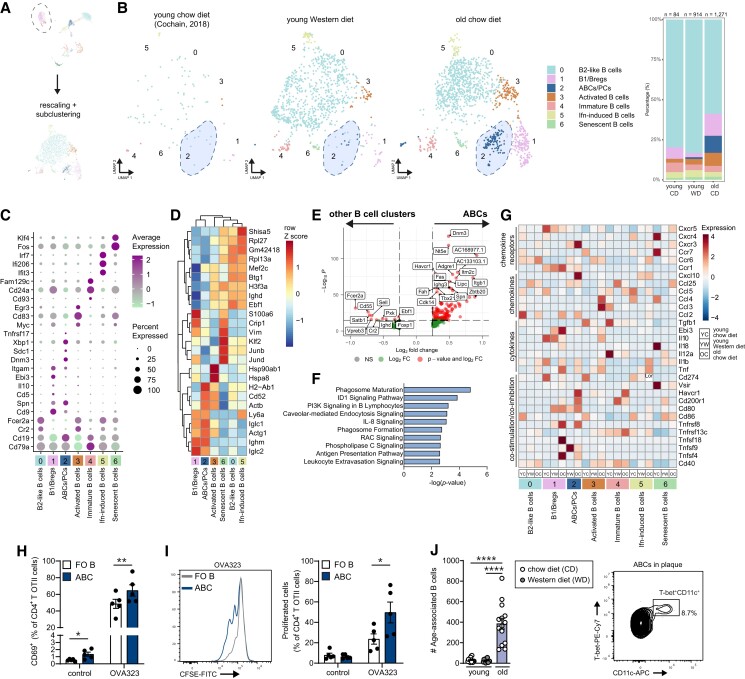

Next, transcriptomes of the three datasets were integrated to perform comparative analysis on the remaining 372 (young CD), 4319 (young WD), and 4674 (old CD) cell counts, followed by clustering. For the high-resolution re-clustering, B-cell clusters (Cd79b+), T-cell clusters (Cd3e+), and myeloid clusters (Cd68+ and Itgam+) were selected and extracted from the main clustering. Re-clustering on rescaled transcripts was performed resulting in: 3561 T-cells, 2269 B-cells, and 1166 myeloid cells. Within cluster 2 of the B-cell clustering, bona fide ABCs were separated from plasma cells (PCs) by setting a threshold on Igkc expression levels: ABCs, Igkc < 6.3, and PCs, Igkc > 6.3 (see Supplementary material online, Figure S6H). Differential gene expression of bona fide ABCs was used for volcano plot generation and pathway analysis in Figure 4. Pathway analysis was performed using Ingenuine Pathway Analysis (IPA) Software (Qiagen).

Figure 4.

Characterization of age-associated B-cells in atherosclerotic aortas of Ldlr−/− mice. (A) Cd79a+ clusters were extracted from the principal clustering and reclustered, after which the B-cells clusters were identified. (B) UMAP plots and stacked diagrams visualizing the identified B-cell subclusters, in which ABCs are encircled in the dashed blue shape. (C) Dot plot showing the average expression of immune cell cluster-defining markers for each cluster. (D) Heatmap of hierarchically clustered top 25 variable genes across B-cell subclusters. (E) Volcano plot of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the age-associated B-cells (ABCs), excluded of plasma cells (PCs), compared to other B-cells in the B-cell subclustering. (F) Top canonical pathways of the ABCs. (G) Heatmap showing average expression of biological process-associated genes in B-cell clusters of young CD, young WD, and old CD Ldlr−/− aortas. (H) ABCs and follicular (FO) B-cells were tested for their capability to present OVA323 peptide antigen to CD4+ OTII T-cells and induce T-cell activation (CD69+) or (I) proliferation (n = 5). (J) Absolute numbers of CD19+CD11b+CD11c+ ABCs and representative plot of associated protein expression of CD11c and T-bet within the ABCs in aortas of Ldlr−/− mice (n = 12–15). Gating strategy is shown in Supplementary material online, Figure S5A. Statistical significance was tested by two-tailed paired t-test (FO B-cells vs. ABCs) or one-way ANOVA (three groups). Mean ± S.e.m. plotted. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

2.9. Projection of scRNA-seq analysis of aortic cells of non-atherosclerotic C57BL/6 mice onto Ldlr−/− aortas

ScRNA-seq data of C57BL/6 mice of 3–24 months of age15 were loaded and excluded of non-immune cells (e.g. endothelial cells; Supplementary material online, Figure S7B). A total of 45 (3 months), 27 (18 months), and 19 (24 months) aortic immune cells were included in this analysis and set as query dataset. Our scRNA-seq dataset of atherosclerotic aortas from Ldlr−/− mice was set as reference dataset. With the MapQuery function, the query cells were projected onto the Ldlr−/− Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) structure.

2.10. PMA/ionomycin stimulation

Single cell suspensions from spleen were stimulated for 4 h with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) (50 ng/mL, Sigma), ionomycin (500 ng/mL, Sigma), and the Golgi-plug brefeldin A (3 μg/mL, Thermo Fisher) to detect intracellular cytokine expression with flow cytometry.

2.11. In vitro antigen presentation assay

Splenic ABCs and follicular (FO) B-cells were isolated from aged female Ldlr−/− mice (aged 12–20 months old, n = 5) and exposed to OVA323 peptide antigen or control medium for 4 h at 37°C 5% CO2. Next, B-cells were co-cultured in a 1:1 ratio with CD4+ T-cells from OTII mice for 24 h, after which activated CD69+ cells were measured as percentage CD4+ T-cells with flow cytometry. Proliferation was assessed by co-culturing OVA323-exposed B-cells with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labelled CD4+ T-cells for 72 h, followed by measurement of CFSE dilution.

2.12. Macrophage polarization and in vitro phagocytosis assay

M1 and M2 bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were cultured from young and aged chow diet-fed Ldlr−/− mice (n = 5 per group). To assess efferocytosis capacity, M1 and M2 macrophages were exposed to CFSE-labelled apoptotic splenocytes for 2 h, after which uptake was measured by flow cytometry. To assess lipid uptake, macrophages were cultured with 4 μM cholesteryl-BODIPY FL C12 (Invitrogen, #C3927MP) for 24 h, followed by measurement of alive BODIPY+ (lipid-laden) macrophages using flow cytometry.

2.13. Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± S.e.m. Outliers were identified and removed using Grubbs outlier tests (α = 0.05). Significance of mouse data with three groups was tested using an ordinary one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test or non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test followed by a Tukey or Dunn multiple comparisons test, respectively. Significance of young vs. aged BMDMs was tested by two-tailed unpaired t-test. Significance of FO B-cells vs. ABCs was tested by two-tailed paired t-test. Significance of human data was tested using a two-tailed paired t-test. P values of <0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0.

3. Results

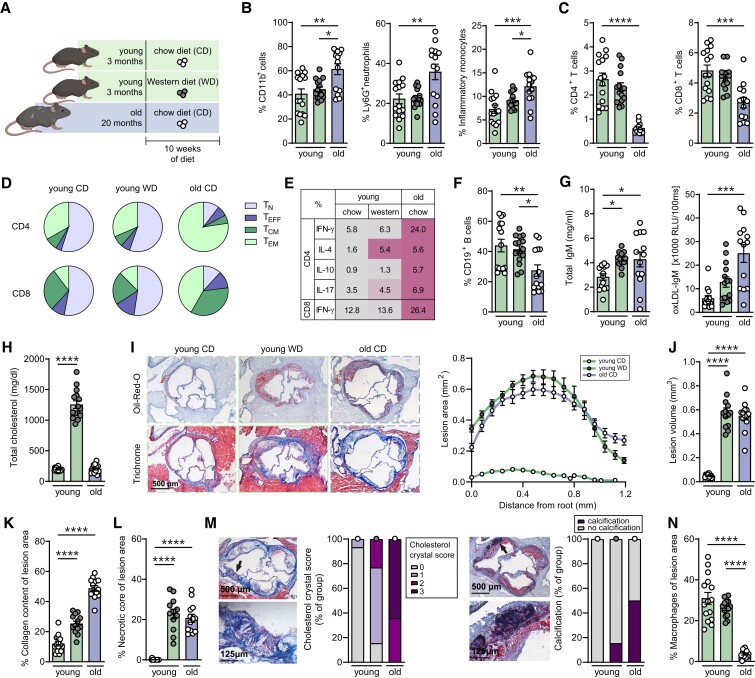

3.1. Myeloid skewing and reduced lymphoid output in aged Ldlr−/− mice

We set out to investigate the impact of aging on innate and adaptive immunity in atherosclerosis. To this extent, leucocyte populations were characterized in the circulation and lymphoid organs of chow diet-fed (CD) or Western diet-fed (WD) young (5 months) and old CD (22 months) Ldlr−/− mice (Figure 1A). Circulating myeloid CD11b+ cells, including neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes, were elevated with age (Figure 1B). Conversely, the lymphoid output, as measured by CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells and CD19+ B-cells in the blood, was decreased upon aging (Figure 1C–F). Within the T-cell compartment, aging significantly reduced the proportion of circulating naïve CD8+ T-cells, whereas central memory CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells were increased (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2A). More apparent shifts from naïve to memory T-cell populations were observed in the spleen (Figure 1D). Besides changes in lymphoid output, aging can also affect the activation status of lymphocytes.3 As shown in Figure 1E, T-cells producing interferon-γ (IFN-γ), interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-10, and IL-17 were elevated in aged Ldlr−/− mice, indicating enhanced regulatory and effector T-cell functionality. Since aging can also alter humoral immunity,16 we measured antibody levels in the serum. Total serum immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) and IgG2c levels remained unchanged in aged mice compared to young mice (data not shown), while total IgM and oxidized LDL-specific IgM (oxLDL-IgM) levels were increased upon aging (Figure 1G).

Figure 1.

Aging promotes immunosenescence and atherosclerosis in Ldlr−/− mice. (A) Experimental setup: Ldlr−/− mice aged 3 months (green bars) or 20 months (violet bars) were fed with a standard chow diet (white circles) or a Western diet (grey circles) for 10 weeks. (B) Using flow cytometry, percentages (% from live) of circulating myeloid cells (CD11b+), neutrophils (CD11b+Ly6CintLy6G+), inflammatory monocytes (CD11b+Ly6ChiLy6G−), and (C) circulating CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells were determined (% from live). (D) Splenic naïve (TN: CD44−CD62L+), effector (TEFF: CD44−CD62L−), central memory (TCM: CD44+CD62L+), and effector memory (TEM: CD44+CD62L−) T-cells were quantified as a percentage of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells and plotted in pie charts. (E) Intracellular cytokine production of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10, and IL-17 were measured as percentage (mean) of splenic CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells after 4 h of stimulation with PMA and ionomycin. Colour scale is normalized for each cytokine. (F) Circulating CD19+ B-cells were determined with flow cytometry. (G) Total and oxidized LDL (oxLDL)-specific IgM titres were measured in the serum. (H) Total serum cholesterol levels at sacrifice were measured. (I) Cross sections of the aortic root were stained for lipid and collagen content, and (J) atherosclerotic lesion volume was quantified. (K) Collagen content and (L) necrotic cores were quantified as percentage of lesion area. (M) Cholesterol crystallization in atherosclerotic lesions was categorized on a scale of 0 (no cholesterol crystallization) to 3, and presence of calcification (purple) or no calcification (grey) was presented as percentage of group. (N) Macrophage content (MOMA-2) was measured as percentage of lesion area. Data are from n = 12–15 mice per group. Statistical significance was tested by one-way ANOVA. Mean ± S.e.m. plotted. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

3.2. Aging promotes atherosclerosis

Next, we determined the influence of age on the development of atherosclerosis and lesion composition in Ldlr−/− mice. As shown in Figure 1H and Supplementary material online, Figure S2B, body weight increased with age, and total serum cholesterol and triglyceride levels increased upon Western diet feeding. Whereas Western diet-induced hypercholesterolaemia was essential for the development of atherosclerosis in young Ldlr−/− mice, upon aging, Ldlr−/− mice developed atherosclerosis on a regular CD (Figure 1I and J and Supplementary material online, Figure S2C). In contrast to wildtype (WT) C57BL/6 mice that have relatively low cholesterol levels and do not develop atherosclerosis (see Supplementary material online, Figure S2D), chow diet-fed Ldlr−/− mice develop atherosclerotic lesions with mildly elevated cholesterol levels upon aging, thereby mimicking the disease progression as manifested in humans. As shown in Figure 1K and L, aging promotes collagen-rich atherosclerotic lesions, while the relative necrotic core area is similar in young and aged plaques. Moreover, while lesions in young Ldlr−/− mice showed little accumulation of cholesterol crystals and rarely any signs of calcification, we observed an increase in crystals and calcification areas in lesions of aged Ldlr−/− mice (Figure 1M). Concomitantly, lesions from aged mice show a reduction in relative macrophage content compared to lesions from young WD-fed Ldlr−/− mice (Figure 1N and Supplementary material online, Figure S2E).

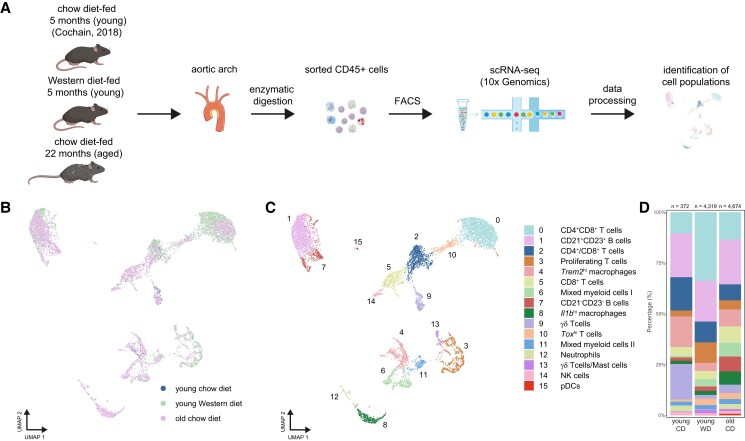

3.3. Single-cell transcriptomic profile shows age-associated immune alterations in atherosclerotic Ldlr−/− aortas

We next mapped the immunological landscape of the aged atherosclerotic plaque by performing scRNA-seq (10x Genomics Chromium) on FACS CD45+ cells from the aortic arch of aged atherosclerotic Ldlr−/− mice (old CD, Figure 2A). To define age-associated changes in aortic leucocytes, we integrated scRNA-seq data of aortic CD45+ cells from non-atherosclerotic young CD Ldlr−/− mice9 and atherosclerotic young WD Ldlr−/− mice, which currently is one of the most frequently used atherosclerosis models.

Figure 2.

Integrated scRNA-seq analysis reveals age-associated leucocyte alterations in atherosclerotic mouse aortas. (A) Workflow of scRNA-seq on aortic CD45+ cells of chow diet-fed young Ldlr−/− mice (young CD, n = 9),9 or Western diet-fed (10 weeks) young Ldlr−/− mice (young WD, n = 29) and chow diet-fed aged Ldlr−/− mice (old CD, n = 12). UMAP visualization of clustered aortic leucocytes grouped by (B) sample or (C) immune cell clusters. (D) Stacked diagram showing the relative proportions of major immune cell subtypes within CD45+ cells of Ldlr−/− aortas. NK, natural killer; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell.

The analysis of 372 (young CD), 4319 (young WD), and 4674 (old CD) single-cell transcriptomes with a UMAP projection revealed 16 distinct immune cell clusters in the atherosclerotic aorta (Figure 2B and C and Supplementary material online, Figure S3A and B), providing, to our knowledge, the first comprehensive atlas of immune cells present in atherosclerotic aortas of aged Ldlr−/− mice. We assigned biological identities to major immune cells by interrogating expression patterns and canonical marker genes17 (see Supplementary material online, Figure S3C and D and Supplementary material online, Table S1): B-cells (Cd79a and Cd19), T-cells (Cd3e, Cd4, Cd8a, and Tcrg-c1), natural killer (NK) cells (Klr1bc and Ncr1), and myeloid cell populations (Itgam, Cd68, and Adgre1). Among CD45+ cells in the aorta of young CD, WD, and old CD mice, myeloid cell clusters (cl. 4, 6, 8, 11, 12, and 15) accounted for 22% in young CD, 12% in young WD, and 27% in old CD mice, Cd79a+ B-cells (cl. 1 and 7) for 23% in young CD, 22% in young WD, and 29% in old CD mice, and Klrb1c+ NK cells (cl. 14) for 2% in young CD and 1% in both young WD and old CD mice, while Cd3e+ T-cells (cl. 0, 2, 3, 5, 9, 10, and 13) were the most abundant (53% in young CD, 65% in young WD, and 42% in aged CD mice; Figure 2D).

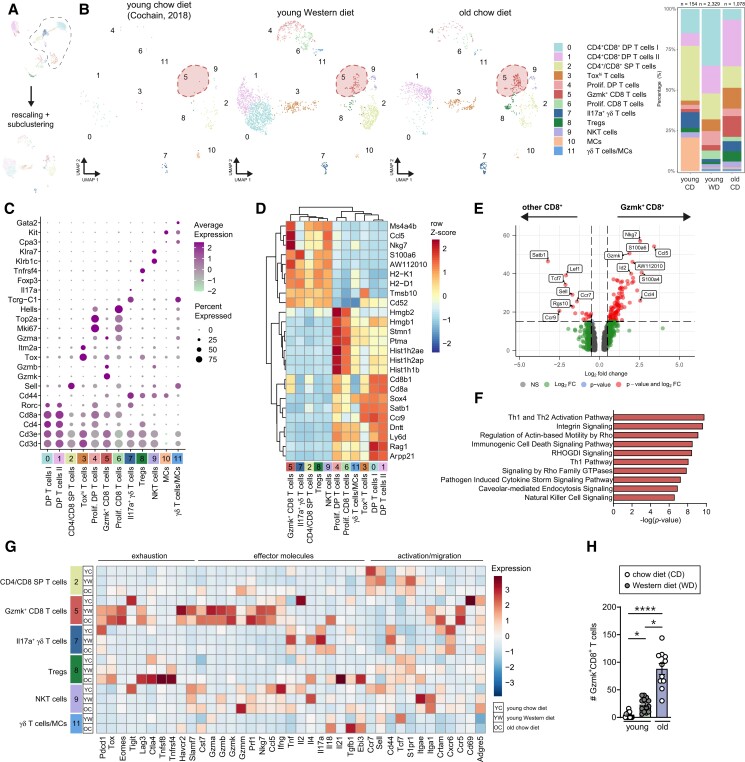

3.4. Integrated scRNA-seq analysis of T-cells reveals a large CD8+GzmK+ T-cell population in aged atherosclerotic aortas

Although T-cells have been well-described in atherosclerosis progression, in the lymphoid system and locally in the lesion,18 the impact of aging on T-cell subsets remains largely unknown. To identify age-associated alterations within the T-cell compartment in atherosclerotic aortas, we reclustered the Cd3e+ T-cells from the principal clustering, resulting in 12 distinct clusters (Figure 3A and B and Supplementary material online, Figure S4A).

Figure 3.

Identification of age-associated T-cell populations and gene signatures in atherosclerotic aortas from Ldlr−/− mice. (A) Cd3e+ clusters were extracted from the principal clustering and reclustered, after which the T-cell clusters were identified. (B) UMAP plots and stacked diagrams visualizing the identified T-cell subclusters in young CD, young, WD and old CD aortas, in which Gzmk+CD8+ T-cells are encircled in the dashed red shape. (C) Dot plot showing the average expression of immune cell cluster-defining markers for each cluster. (D) Heatmap of hierarchically clustered top 25 variable genes across T-cell subclusters. (E) Volcano plot of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the Gzmk+CD8+ T-cell cluster compared to other CD8+ T-cells in clusters 2, 3, 5, and 6. (F) Top canonical pathways of the Gzmk+CD8+ T-cell cluster compared to CD8+ T-cells in clusters 2, 3, 5, and 6. (G) Heatmap showing average expression of biological process-associated genes in T-cell clusters of young CD, young WD, and old CD Ldlr−/− aortas. (H) Using flow cytometry, absolute numbers of Ly6C−CD44+Tox+PD-1+ CD8+ T-cells (GzmK+CD8+ T-cells) were measured in aortas of young and aged Ldlr−/− mice (n = 11–15). Gating strategy is shown in Supplementary material online, Figure S5B. Statistical significance was tested by one-way ANOVA. Mean ± S.e.m. plotted. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001. DP, double positive; SP, single positive; Tregs, regulatory T-cells; NKT, natural killer T; MC, mast cells.

Three T-cell clusters (cl. 0, 1, and 4) co-expressed Cd4 and Cd8 (Figure 3C). Clusters 0 and 1 exhibited a gene expression profile similar to that of late stage CD4+CD8+ double positive (DP) thymocytes.19,20 Besides high expression level of Rorc, leading differentially expressed genes (DEGs) of clusters 1 and 2 included Rag1 and Ccr9 (Figure 3D and Supplementary material online, Table S2). Comparative analysis between clusters 0 and 1 showed higher expression of Ifngr1, Ly6d, Lgals1, and Anxa2, while Malat1, Rag1, and Glcc1 were less expressed in cluster 0 compared to cluster 1 (Supplementary material online, Figure S4B). Clusters 4 (DP T-cells) and 6 (Cd4−Cd8+ T-cells) were enriched in genes associated with cell organization and cell cycle processes (Nusap1, Top2a, and Mki67), suggesting that these clusters are distinguished by their (proliferative) cell cycle state (see Supplementary material online, Table S2). Specifically, some DP cells and proliferating CD8+ T-cells (clusters 1, 4, and 6) expressed Gzma, indicating cytotoxic properties (Figure 3C and Supplementary material online, Figure S4C). Adjacent to the large CD4+CD8+ population, cluster 3 is located, which contains Toxhi CD4+CD8+ DP, CD4+, and CD8+ single positive (SP) T-cells (Figure 3B). Top DEGs in this cluster were Itm2a, Tox, and Lef1, which are usually involved in DP thymocyte selection, activation, and differentiation.21,22

Cluster 2 contains CD4+ and CD8+ SP T-cells, and is defined by T-cell activation state, as we observed a gradient of Cd44 and Sell (CD62L) expression, indicating the presence of naïve or quiescent T-cells, and memory T-cells. While Cd44−Sell+ naïve-like cells were mainly found in the aorta of young CD and WD mice, Cd44+ cells were mostly present in the aged atherosclerotic aorta (see Supplementary material online, Figure S4D). Although we could not retrieve distinct clusters of typical CD4+ T-cell subsets (e.g. Th1 or Th2 cells), we identified a CD4+ T-cell cluster (cluster 8) that mainly contained regulatory T-cells (Tregs) expressing Foxp3, Izumo1r (folate receptor 4), Tnfrsf4 (OX40), Ctla4, and Nt5e.23 Tregs from aged Ldlr−/− mice showed higher expression of Ctla4, Lag3, and Tnfrsf4, in addition to higher expression of cytokines (e.g. Tgfb1 and Ebi3 that encodes for the IL-35 subunit; Figure 3G).

Cluster 5 contained CD8+ T-cells with a gene expression profile suggestive of an effector (Nkg7, Gzmk, Gzmb, and Fasl), but also exhausted (Eomes, Pdcd1, and Lag3) phenotype. The signature of these cells (Figure 3G and Supplementary material online, Figure S4E) resembles the recently described age-associated granzyme K (Gzmk)-expressing CD8+ T (Taa) cells.24 Indeed, these Taa cells were almost absent in young CD aortas, and mostly present in the aorta of old CD mice (Figure 3B). Compared to other CD8+ T-cells in clusters 2, 3, and 6, Taa cells highly expressed Gzmk, Ccl5, Nkg7, Cd52, and Id2, indicating again an effector and memory phenotype (Figure 3E and Supplementary material online, Figure S4F). Th1/Th2 and NK signalling pathways were enriched in cluster 5 (Figure 3F), suggesting that these cells might be active effector cells.25 When we compare the few Gzmk+CD8+ T-cells found in young aortas with the Gzmk+CD8+ T-cells found in old CD aortas, aged Gzmk+CD8+ T-cells showed high expression of exhaustion-associated markers and effector molecules Gzmk, and Prf1, indicating a more extreme phenotype in aged than in young atherosclerotic aortas (Figure 3G).

Enrichment of NK-marker genes (Klre1, Klrk1, and Klrb1c) and cytotoxic marker genes Gzmb and Gzmm were observed in cluster 9, indicative of NKT-cells. Besides conventional αβ T-cells, we also identified γδ T-cells in clusters 7 and 11. Cluster 11 is most likely a mix of γδ T-cells and progenitor-like mast cells (Nfe2, Cd34, Cpa3, and Gata2; Figure 3C and Supplementary material online, Table S2), whereas cluster 7 exclusively expressed Il17a (Figure 3C and G), consistent with IL-17-producing γδT17 cells.26 We detected few remainder Cd3e− mast cells (Kit, Gata2, and Fcer1a) in cluster 10.

Overall, T-cells in aortas from young mice mainly include naïve, developing and proliferating T-cells, while T-cells from old atherosclerotic aortas exhibit increased expression of activation markers (e.g. Crtam and Adgre5; Figure 3G) and mostly consist of effector (memory) T-cells, Tregs and age-associated T-cells.

To validate our age-induced changes found with scRNA-seq, we performed flow cytometry on immune cells within the atherosclerotic aortic arch. CD4+ T-cells, CD8+ T-cells, and CD4+CD8+ DP T-cells within the Ldlr−/− aorta were increased upon aging (see Supplementary material online, Figures S4G and S5A). Although present in small numbers in atherosclerotic aortas of young WD mice, we confirmed a significant ∼four-fold increase in Ly6C−CD44+Tox+PD-1+ CD8+ T-cells within the aortas of old CD mice (P < 0.05; Figure 3H and Supplementary material online, Figure S5B), representing the Gzmk+CD8+ T-cells.

3.5. Identification of age-associated B-cells with pro-inflammatory features in aged atherosclerotic aortas

B-cells in atherosclerosis can be considered pro-atherogenic (B2-cells) or anti-atherogenic (MZ B-cells, B1-cells, and regulatory B-cells),27 and have been found in transcriptomic studies of young atherosclerotic aortas.8,9 To identify age-associated differences in B-cell subpopulations in the aorta, we reclustered Cd79a+ B-cells from the principal clustering at higher resolution (Figure 4A), resulting in the identification of seven separate cell populations (Figure 4B and Supplementary material online, Figure S6A). Cells within clusters 0 and 3 show high differential gene expression levels of Cr2 (CD21), Fcer2a (CD23), and Ighd (encoding for IgD), which are markers characteristic of mature B2-cells (Figure 4C and D). Cluster 3 contains activated B-cells as they are enriched for genes associated with B-cell activation (Myc, Egr3, Irf4, and Cd83) and heat-shock protein-associated genes (Figure 4D).28 Cluster 5 exhibited high expression levels of genes related to the interferon-induced response module (Ifit3, Ifi206, and Irf7; Supplementary material online, Table S3).

Interestingly, Cr2low (encoding CD21) clusters 1 and 2 were almost exclusively present in the aorta of old CD mice, but nearly absent in the aortas of young CD mice. Cells within cluster 1 are enriched for markers characteristic of B1-cells as we observed high expression of Cd9, Spn (CD43), and Ighm (IgM), but low expression of Fcer2a and Ighd. Besides a B1-cell-associated marker, Cd9 also identifies regulatory B-cells (Bregs).29 Indeed, high levels of Breg-associated genes, including the anti-inflammatory cytokines Il10, Ebi3, Atf3, and Slamf9, were detected in cluster 1 (see Supplementary material online, Table S3).30,31 Interestingly, Bregs of aged mice showed a relative high expression of IL-35-associated Ebi3, while young Bregs showed elevated Il10 expression (Figure 4G), indicating a shift in phenotype upon aging. Moreover, cluster 1 showed high expression of Zbtb32 (see Supplementary material online, Table S3), a gene involved in plasma cell differentiation, which has previously been observed in splenic and peritoneal CD21low B-cells.24,32 B-cells within cluster 2 showed co-expression of Itgam (CD11b), Itgax (CD11c), Tbx21 (transcription factor T-bet), and Fas (Figure 4B and Supplementary material online, Figure S6B), which we identified as so-called ABCs. ABCs, characterized by the expression of CD11b, and/or CD11c and T-bet, progressively accumulate with age and during autoimmunity.33–36 Comparison of bona fide ABCs with other B-cell clusters showed a distinct gene signature with high expression of Tbx21 (transcription factor T-bet), Fas, Zbtb20, and Ighg3 (Figure 4E). High expression of H2-Ab1 (encoding MHCII) and Dnm3 (dynamin 3, a GTPase involved in endocytosis) (Figure 4D and E) supports previous reports in which ABCs have been described as efficient antigen-presenting cells.37,38 Correspondingly, signalling pathways associated with phagosome formation and antigen presentation were enriched in the ABCs (Figure 4F). In addition, ABCs, as well as B1-cells and Bregs, from aged Ldlr−/− mice show high expression of co-stimulatory and inhibitory molecules, such as Tnfsf4 (OX40L), Tnfsf18 (GITRL), Tnfrsf8 (CD30), Cd80, and Havcr1 (TIM-1) compared to other B-cell clusters (Figure 4G). In support of these data, we show that ABCs from aged atherosclerotic mice are superior in antigen presentation and T-cell activation compared to FO B-cells, as demonstrated by elevated percentages of CD69+ CD4 T-cells and vigorous antigen-specific T-cell proliferation upon OVA323 peptide antigen exposure (Figure 4H and I and Supplementary material online, Figure S6C–E).

Using flow cytometry, we confirmed the large age-induced increase of total B-cells and presence of ABCs in aortas of aged Ldlr−/− mice based on the expression of CD11b, CD11c, and T-bet (young WTD 27 ± 4 cells vs. aged chow 386 ± 53 cells, P < 0.01; Figure 4J and Supplementary material online, Figures S5A and S6F). Accumulation of ABCs in the aorta is not restricted to Ldlr−/− mice, as we also observed an age-dependent expansion of ABCs in atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice and non-atherosclerotic C57BL/6 mice. However, healthy aortas of old C57BL/6 mice show reduced ABC numbers compared to age-matched atherosclerotic Ldlr−/− and Apoe−/− mice, indicative that the atherosclerotic environment promotes expansion of ABCs (see Supplementary material online, Figure S6G).

Besides ABCs, we observed PCs within cluster 2 that highly expressed Igkc (Ig kappa constant; Supplementary material online, Figure S6H), indicating that these PCs produce high levels of antibodies. These PCs exhibited a relatively low expression of Cd19, but high expression of Sdc1 (Syndecan-1 or CD138), Xbp1, and Tnfrsf17 (BCMA),39 and were mostly present in the aorta of old CD mice (Figure 4B).

In cluster 4, we identified immature B-cells, consistent with high expression levels of the transitional B-cell marker Cd93. B-cells in cluster 6 showed high expression of Klf4/6, Junb/d, and Fos, which are involved in the suppression of cell proliferation, but are also features of cellular senescence,40–42 suggesting that these may be senescent B-cells (Figure 4D and Supplementary material online, Table S3).

Altogether, the B-cell compartment in the atherosclerotic aorta is greatly affected by aging, emphasized by enhanced activation, e.g. elevated expression of co-stimulatory/inhibitory molecules, cytokines, and chemokines, particularly in the B1/Breg and ABC clusters (Figure 4G).

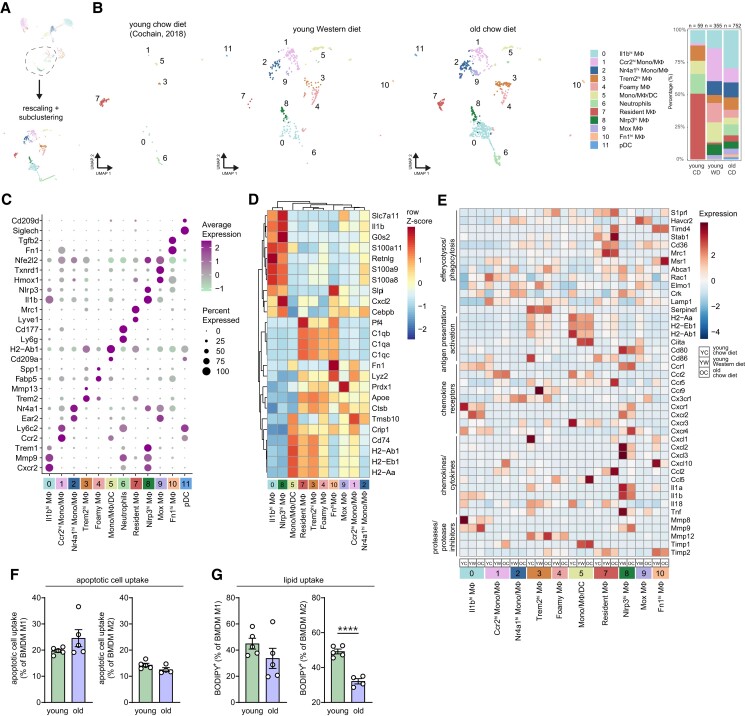

3.6. Integrated analysis of myeloid cells reveals enrichment of inflammatory macrophages in aged atherosclerotic aortas

Myeloid populations such as dendritic cells and macrophages have been described as major players in atherosclerosis.43 To assess age-induced changes within the myeloid cells, we reclustered the myeloid repertoire at higher resolution, resulting in 12 distinctive myeloid subpopulations (Figure 5A and B).

Figure 5.

Integrated analysis of myeloid cells reveals age-induced phenotype alterations in macrophage subpopulations in atherosclerotic aortas. (A) Cd68+ and Itgam+ clusters were extracted from the principal clustering and reclustered, after which the myeloid clusters were identified. (B) UMAP plots and stacked diagrams visualizing the identified myeloid subclusters. (C) Dot plot showing the average expression of immune cell cluster-defining markers for each cluster. (D) Dendrogram heatmap based on the 25 most differentially expressed genes from all macrophage clusters. (E) Heatmap showing average expression of biological process-associated genes in myeloid cell clusters of young CD, young, WD and old CD Ldlr−/− aortas. (F and G) Percentage of M1- or M2-like bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) of young and aged Ldlr−/− mice (n = 5), which have taken up apoptotic cells (F) or BODIPY-labelled cholesteryl lipids (G), was measured by flow cytometry, of which the gating strategy is shown in Supplementary material online, Figure S7C. Statistical significance was tested by one-way ANOVA. Mean ± S.e.m. plotted. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Clusters 0 and 8 hold M1-like Il1b+ macrophages that showed high expression of pro-inflammatory markers, such as Il1b and Nlrp3, in addition to the gene encoding triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 1 (Trem1; Figure 5C).44 Interestingly, expression of genes encoding pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines (Cxcl2, Cxcl3, Il1a, Il1b, Il18, and Tnf) was decreased in aged compared to young macrophage clusters 0 and 8. In contrast, expression of extracellular matrix degrading metalloprotease (MMP) 9 was increased in aged Il1bhi and Nlrp3hi macrophages, suggesting an age-induced shift in functionality (Figure 5E).

Clusters 3, 4, and 7 show an M2-like macrophage signature with a common expression of Trem2, Apoe, and genes encoding complement C1q chains (C1qa, C1qb, and C1qc) (Figure 5C and D).41 Lyve1+Mrc1+ resident macrophages9,45 (cluster 7) were the main immune cell population in aortas of young CD mice (Figure 5C). Trem2+ macrophages in cluster 4 displayed high expression of genes including Abcg1, Fabp4, Fabp5, Spp1, Lgals3, and Apoe, indicative of foamy macrophages,44,46 which were absent in aortas of young CD mice, present in young WD mice, but relatively decreased in old CD mice (Figure 5B and Supplementary material online, Figure S7B). Upon aging, genes related to antigen presentation and activation (e.g. H2-Aa, H2-Ab1, and Cd86) were increased in the resident macrophages (Figure 5E), but not in Trem2hi macrophages. In addition, expression of MMP-12 was up-regulated with age in the Trem2hi (foamy) macrophage clusters 3 and 4, although tissue inhibitor of MMPs (TIMP) 2, encoded by Timp2, was also up-regulated in these clusters (Figure 5E). Considering the phagocytic capacity of macrophages, macrophages from aged Ldlr−/− mice express more recognition receptors important for efferocytosis (e.g. Stab1 and Timd4) while expression of genes involved in engulfment (e.g. Abca1, Rac1, and Elmo1) was decreased compared to that in young macrophages (Figure 5E),47 suggesting an age-induced change in phagocytic capacity. To test age-related effects on macrophage phagocytosis, we skewed BMDMs from young and aged Ldlr−/− mice towards an M1- or M2-like phenotype and tested in vitro phagocytic function. Although apoptotic cell uptake was not altered upon aging, lipid uptake (% BODIPY+ cells) was decreased in aged compared to young M2-like BMDMs (Figure 5F and G and Supplementary material online, Figure S7C). The latter observation is in line with our scRNA-seq data, which showed a decrease in engulfment-related genes that could lead to decreased lipid uptake.

Besides the Il1b+ and Trem2+ macrophage subsets, we also identified a population resembling Mox macrophages in cluster 9.48 These macrophages were characterized by high expression of Nrf2 (encoded by Nfe2l2), a transcription factor that activates genes involved in synthesis of antioxidant enzymes in response to oxidative stress, and co-expression of antioxidant-associated genes Hmox, Txnrd1, and Cebpb (Figure 5C).48 In cluster 10, we detected macrophages with high expression of fibronectin (Fn1). Furthermore, we observed possibly recently recruited Ly6c2hi monocytes and/or macrophages with high expression of Ccr2 and Fn1 in cluster 1. Cluster 2 contained Ly6c2lo monocytes and/or macrophages expressing Nr4a1 and Ear2, which have been described to have anti-atherogenic properties.9 Cluster 5 contains a mix of monocytes, macrophages, and DCs (Cd209a, Flt3, and Klrd1; Figure 5C and Supplementary material online, Table S4), with high expression of genes encoding for MHCII (H2-Ab1, H2-Aa, and H2-Eb1; Figure 5D). In contrast to the Trem2+ macrophages, cluster 5 exhibits reduced expression of antigen presentation-associated genes in aged compared to young mice (Figure 5E), which is in line with a transcriptomic profiling study describing an age-associated down-regulation of antigen-presentation pathways in human DCs.49 Finally, we recovered two non-macrophage myeloid clusters from the principal clustering that were characterized as neutrophils (cluster 6) and pDCs (cluster 11; Figure 5C).

To summarize, aging affects the myeloid compartment in the atherosclerotic aorta by inducing a relative increase in Il1b+ macrophages, by up-regulating macrophage-derived MMP expression, and by altering antigen-presentation and phagocytosis-associated gene signatures.

3.7. Projection of scRNA-seq analysis of vascular leucocytes in healthy aortas onto atherosclerotic aortas

Additionally, we projected scRNA-seq data of healthy non-atherosclerotic aortas from young and aged C57BL/6 mice15 onto our scRNA-seq data of Ldlr−/− aortas (see Supplementary material online, Figure S8). Few immune cells are residing in the arterial wall of C57BL/6 aortas, which consisted mostly of Cd68- and Itgax-expressing myeloid cells that belong to clusters 4 (Trem2hi macrophages), 6 (mixed myeloid cells I), and 11 (mixed myeloid cells II), while T- and B-cells were less present (see Supplementary material online, Figure S8B and C).

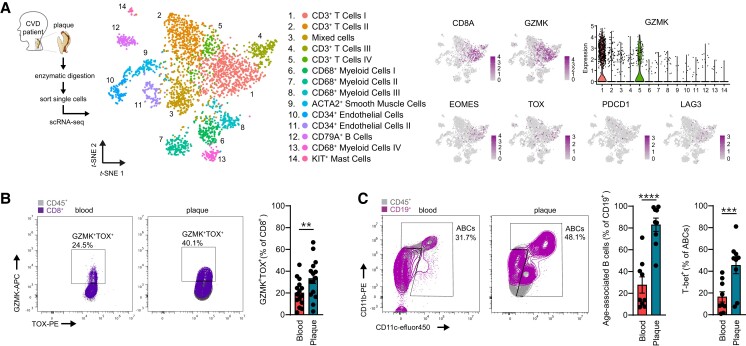

3.8. Age-associated T- and B-cells are present in human atherosclerotic plaques

Using scRNA-seq, we have reported transcriptomic immune cell alterations in the aged aorta of Ldlr−/− mice, including the presence of age-associated cell subsets. To translate our findings and explore the relevance of Gzmk+CD8+ T-cells in human atherosclerosis, we utilized a single-cell transcriptome dataset of 18 human plaques.12 Granzyme K was mostly expressed in the largest T-cell cluster, namely CD3+CD8+ T-cells, and similar to Gzmk+CD8+ T-cells in aged mice, these cells expressed EOMES, TOX, PDCD1 (PD-1), and LAG3 (Figure 6A). Furthermore, we confirmed the presence of Gzmk+TOX+CD8+ T-cells with high expression of PD-1, in human atherosclerosis using flow cytometry (Figure 6B and Supplementary material online, Figure S9A), of which plaques showed higher levels of Gzmk+TOX+CD8+ T-cells within the CD8+ T-cells (33.3 ± 4.6%) as compared to blood (20.1 ± 3.1%, P < 0.01). Finally, we confirmed the presence of ABCs, based on the expression of CD11b, CD11c, and T-bet, in human atherosclerotic plaques and PBMCs obtained from patients that underwent carotid endarterectomy (∼71 years old; Figure 6C and Supplementary material online, Figure S9B) using flow cytometry. Intriguingly, we observed significantly increased levels of ABCs within the B-cell compartment in the plaque (82.9 ± 6.1%) compared to the circulation (27.7 ± 7.4%, P < 0.0001). In addition, human atherosclerotic plaques exhibited increased levels of T-bet+ ABCs compared to PBMCs, which can be a consequence of tissue residency and the pro-inflammatory microenvironment in the plaque.50,51

Figure 6.

Flow cytometry analysis confirms expansion of age-associated T- and B-cells in human atherosclerotic plaques. (A) Single-cell RNA-sequencing analysis of human atherosclerotic plaques (n = 18),12 in which gene expression of GzmK+CD8 T-cell-associated markers GZMK, EOMES, TOX, PDCD1, and LAG3 are shown. (B) Representative plot and quantification of GZMK+TOX+ as percentage of CD8+ T-cells as measured in human atherosclerotic plaques and corresponding blood samples (n = 15) with flow cytometry. (C) Representative plot and quantification of CD11b+CD11c+ ABCs as percentage of B-cells, and expression of T-bet within ABCs measured in human atherosclerotic plaques and corresponding blood samples (n = 9) with flow cytometry. Gating strategies are shown in Supplementary material online, Figure S9. Statistical significance was tested by two-tailed paired t-test. Mean ± S.e.m. plotted. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

4. Discussion

Healthy aging is one of the prime goals in today’s society, and atherosclerosis is among the greatest causes of morbidity in elderly. In order to gain better insights into age-driven atherosclerosis and to move one step closer towards tailored immunotherapies, research generating in-depth characterization of systemic and local inflammation in the atherosclerotic plaque upon aging is needed. Although several studies used state-of-the-art proteomic and transcriptomic approaches to identify cell subsets in murine atherosclerotic plaques,8,9,52,53 the translational aspect is limited as these were obtained from young mice, which do not display age-associated immunity. Our study provides, to our knowledge, the first comprehensive analysis of immunity in aged atherosclerotic mice, reporting a systemic myeloid skewing, enhanced effector (memory) phenotypes in T-cells, and the emergence of age-associated, pro-inflammatory immune cells in the atherosclerotic aorta. Moreover, presence of these age-associated immune cells was confirmed in CVD patients.

In contrast to the rapid development of atherosclerosis in young Apoe−/− mice or Ldlr−/− mice fed with a WD, atherosclerosis is a slow process taking decades to develop and progress into advanced atherosclerotic plaques that eventually can cause acute cardiovascular events. Simultaneously, our immune system undergoes numerous changes as we age, including myeloid skewing and a functional decline in our protective immunity, which might affect atherosclerosis progression, plaque composition, and the efficacy of immunotherapies. By using naturally aged Ldlr−/− mice, which have mildly elevated cholesterol levels, both gradual plaque development and immunosenescence are accounted for, thereby resembling disease progression in humans. We observed age-associated alterations, such as elevated circulating monocytes, reduced levels of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells, and a shift from naïve towards effector (memory) T-cells. Although the numerical decline of CD4 T-cells is more subtle in humans upon aging compared to mice,54 age-induced changes within the T-cell compartment, including reduced naïve T-cells, increased memory T-cells, and the arise of age-associated Gzmk+CD8+ T-cells, occur in both.24,55 Additionally, we found increased regulatory and effector T-cells upon activation, particularly pro-atherogenic IFN-γ-producing T-cells, in our naturally aged atherosclerotic Ldlr−/− mice. This corroborates with a recent study by Elyahu et al.56 who showed a similar shift towards a more extreme effector T-cell phenotype within the splenic CD4+ T-cell compartment of old C57BL/6 mice, supporting a detrimental role for aged T-cells in inflammaging and immunosenescence. The age-associated systemic changes can subsequently contribute to plaque growth and alter plaque composition.

In line with transcriptomic and proteomic data of human plaques obtained from aged CVD patients,12,57 T-cell clusters dominated aortic leucocytes in the aorta. Retrieval of conventional T helper cell subsets in the atherosclerotic plaque using scRNA-seq is difficult as we and others were unable to identify separate clusters of Th1/Th2/Th17 cells due to limited detection of their hallmark transcription factors and cytokines. However, we did observe a CD4+ T-cell cluster that mainly contains Tregs. Splenic and lymphoid Tregs from aged C57BL/6 mice showed enhanced release of IL-10, compared to Tregs from young mice,58 which we also observed in our aged Ldlr−/− mice. Although we could not detect IL-10 on mRNA level in the aorta, we found that Tregs from aged aortas show increased expression of Treg-related genes encoding suppressor cytokines TGF-β and IL-35, compared to Tregs from young aortas, confirming an enhanced regulatory phenotype, and could contribute to enhanced collagen deposition that we observed in lesions of aged atherosclerotic mice.59,60 Interestingly, we identified a relatively large population of CD8+ T-cells in the aged aortic arch with enriched exhaustion markers, which mostly expressed Gzmk and Eomes. Recently, GzmK+CD8+ T-cells were shown to expand in mice and humans with age and disease, as these cells are enriched in inflamed tissues of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).24,61 More importantly, we and others show that Gzmk+CD8+ T-cells are abundant in atherosclerotic plaques of CVD patients.12,57 Although GzmK+CD8+ T-cells express exhaustion markers, studies have shown that these cells are potent effector cells through secretion of IFN-γ, CCL5, and GzmK, of which the latter can promote release of pro-inflammatory senescence-associated secretory phenotype components (e.g. IL-6, CCL2, and CXCL1) by senescent cells.24,61 The presence of these cells locally in the atherosclerotic plaque may contribute to enhanced inflammation.

We also found a relatively large amount of B-cells in the aged Ldlr−/− aorta and were able to identify a wide variety of B-cell subsets. The largest cluster was formed by B-cells resembling B2-cells, which are known to aggravate atherosclerosis27 and are also the predominant B-cell subset found in young aortas.8,62 The relative increase of B-cells in aortic leucocytes of aged Ldlr−/− mice could be ascribed to the expansion of CD21low B-cells, which exhibited enhanced activation, as illustrated by elevated expression of genes encoding co-stimulatory/inhibitory molecules, cytokines, and chemokines. Within these CD21low B-cells, we identified B-cells with previously described anti-atherogenic features including CD9+CD43+ B1-like cells and IL-10+ regulatory B-cells.63 B1-cells have also been reported to give rise to pro-atherogenic GM-CSF+ IRA B-cells,64 but we did not find Csf2 (GM-CSF) expression in this cluster. Most interestingly, we identified CD21lowCD11b+CD11c+T-bet+ ABCs in aged aortas, which are superior in antigen-presentation and T-cell activation compared to follicular B2-cells. ABCs are known to accumulate with age and autoimmune diseases,33,34 but up to date have not been described in atherosclerosis. As CD-fed young Ldlr−/− and C57BL/6 mice barely have any atherosclerosis, not surprisingly, scRNA-seq of these healthy C57BL/6 aortas revealed low numbers of immune cell reads. Although this forms a limitation in comparing the data, we supported our scRNA-seq deducted findings with flow cytometry data of ABCs in aortas of Ldlr−/− mice and C57BL/6 mice, showing that accumulation of ABCs in the aortic environment of Ldlr−/− mice is co-dependent on aging and atherosclerosis. ABCs are driven by IL-21, IFN-γ, and Toll-like receptor (TLR) 7 and 9 activation (e.g. via self-nucleic acids), after which they secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α) and high levels of autoantibodies.65 Indeed, we found elevated gene expression levels of IL-1β and TNF-α, plasma cell differentiation-associated gene Zbtb20, and T-bet expression (associated with autoantibody production)66 in the ABC cluster, which supports the pro-inflammatory cytokine and antibody-producing potential of these cells. Previous studies have shown that ABCs exert a pathogenic role in chronic diseases, such as RA, SLE, and Crohn’s disease.67,68 We now show that ABCs are present in CVD patients and are relatively enriched in carotid human plaques compared to the circulation. Possibly, systemic inflammaging and the microenvironment of the atherosclerotic plaque containing debris from damaged and dead cells promote commitment of B-cells to this ABC fate in atherosclerosis, but the exact contribution of ABCs to atherosclerosis is currently under investigation.

Furthermore, we identified distinctive macrophage subsets, including pro-inflammatory Il1b+ macrophages and Trem2+ macrophages.44,69 Macrophages in the aged aorta expressed increased levels of genes encoding MMPs (MMP-9 and 12), although Mmp12 up-regulation in clusters 3 and 6 could be counteracted by up-regulated Timp2 co-expression.70 MMPs are generally associated with plaque instability by degradation of extracellular matrix components (e.g. collagen).71 However, some studies have also reported that MMPs promote collagen deposition in plaques through TGF-β activation,72,73 in addition to increased vascular calcification.74 Increased expression levels of macrophage-derived MMPs in atherosclerotic aortas of aged mice could therefore be associated with the increased collagen content and calcification within the atherosclerotic plaque upon aging, but this should be confirmed with further research on protein level. Notably, previous studies have shown that non-immune cells, such as vascular smooth muscle cells, are known to increase collagen deposition with age75 and can thereby also contribute to the collagen-rich plaque environment in aged Ldlr−/− mice. Defects in phagocytosis and efferocytosis have been observed in macrophages of aged individuals.76 In our data, we show that aging affects lipid uptake by M2-like macrophages in Ldlr−/− mice.

Collectively, we provide comprehensive profiling of aged immunity in atherosclerotic mice, enhancing our knowledge on the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis. Our results stress the importance of taking age into account when aiming to halt progression of atherosclerotic plaques, as we reveal the emergence of specific age-associated T- and B-cell subsets in the atherosclerotic aorta of aged mice and in atherosclerotic plaques and blood of CVD patients. Where the age-associated cells are precisely located in the atherosclerotic plaque environment remains to be investigated. Future research investigating mechanisms underlying the activation, accumulation, and function of age-associated cells in experimental atherosclerosis and CVD patients will further enhance our understanding of disease aetiology and can serve as a foundation for diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to combat CVD.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Berend from the Flow Cytometry Core Facility and Marja from the Genomics Core Facility of the AMC for flow sorting and processing the samples for sequencing. We would also like to thank S. Semrau for his advice on scRNA-seq data processing, and Pien Killiaan and Maria Ozsvar Kozma for the technical help. Graphical abstract, Figure 1A and 2A were created with BioRender.com.

Contributor Information

Virginia Smit, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Jill de Mol, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Frank H Schaftenaar, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Marie A C Depuydt, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Rimke J Postel, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Diede Smeets, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Fenne W M Verheijen, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Laurens Bogers, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Janine van Duijn, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Robin A F Verwilligen, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Hendrika W Grievink, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands; Centre for Human Drug Research, Zernikedreef 8, 2333 CL Leiden, The Netherlands.

Mireia N A Bernabé Kleijn, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Eva van Ingen, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Maaike J M de Jong, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Lauren Goncalves, Department of Surgery, Haaglanden Medical Center—location Westeinde, Lijnbaan 32, 2515 VA The Hague, The Netherlands.

Judith A H M Peeters, Department of Surgery, Haaglanden Medical Center—location Westeinde, Lijnbaan 32, 2515 VA The Hague, The Netherlands.

Harm J Smeets, Department of Surgery, Haaglanden Medical Center—location Westeinde, Lijnbaan 32, 2515 VA The Hague, The Netherlands.

Anouk Wezel, Department of Surgery, Haaglanden Medical Center—location Westeinde, Lijnbaan 32, 2515 VA The Hague, The Netherlands.

Julia K Polansky, Berlin Institute of Health at Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin, BIH Center for Regenerative Therapies (BCRT), Augustenburger Platz 1, 13353 Berlin, Germany.

Menno P J de Winther, Amsterdam University Medical Centers—location AMC, University of Amsterdam, Experimental Vascular Biology, Department of Medical Biochemistry, Amsterdam Cardiovascular Sciences, Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Christoph J Binder, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Medical University of Vienna, Lazarettgasse 14, AKH BT25.2, 1090 Vienna, Austria.

Dimitrios Tsiantoulas, Department of Laboratory Medicine, Medical University of Vienna, Lazarettgasse 14, AKH BT25.2, 1090 Vienna, Austria.

Ilze Bot, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Johan Kuiper, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Amanda C Foks, Leiden Academic Centre for Drug Research, Division of BioTherapeutics, Leiden University, Einsteinweg 55, 2333 CC Leiden, The Netherlands.

Author contributions

V.S. and A.C.F. participated in the conceptualization, performed data analysis, drafted the manuscript, and designed the figures. V.S., J.d.M., F.H.S., M.A.C.D., R.J.P., D.S., J.v.D., R.A.F.V., H.W.G., E.v.I., M.J.M.d.J., M.N.A.B.K., I.B., and A.C.F. executed the animal experiments. L.G., J.A.H.M.P., H.J.S., and A.W. performed carotid endarterectomy procedures and human sample collection at the HMC. V.S. and M.A.C.D. performed FACS and flow cytometry. V.S. performed the scRNA-seq analysis. F.H.S., F.W.M.V., L.B., and A.C.F. contributed to the scRNA-seq clustering analysis. V.S., F.W.M.V., L.B., J.K., M.P.J.d.W., J.d.M., J.K.P., D.T., and A.C.F. contributed to the interpretation of the scRNA-seq data. C.J.B. contributed to the antibody measurements. All authors provided feedback on the research, analyses, and manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Dutch Heart Foundation grant number 2018T051 to A.C.F., 2019T067 to I.B., CVON2017-20: Generating the best evidence-based pharmaceutical targets and drugs for atherosclerosis (GENIUS II) to J.K., and the European Research Area Network on Cardiovascular Diseases (ERA-CVD) B-eatATHERO consortium; Dutch Heart Foundation grant number 2019T107 to A.C.F., Austrian Science Fund (FWF) grant number I4647 to D.T., Bundesministerium für Bildung and Forschung (BMBF) grant number 01KL2003 to J.K.P., and the Fondation Leducq grant number TNE-20CVD03 to C.J.B.

Data availability

In silico data analysis was performed using custom R scripts (R version 4.1.2) designed especially for this research and/or based on the recommended pipelines from the pre-existing packages listed in the individual segments above. Single-cell RNA-sequencing data are available upon personal request from the corresponding author (a.c.foks@lacdr.leidenuniv.nl).

References

- 1. Nikolich-Žugich J. Aging of the T cell compartment in mice and humans: from no naive expectations to foggy memories. J Immunol 2014;193:2622–2629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ho YH, del Toro R, Rivera-Torres J, Rak J, Korn C, García-García A, Macías D, González-Gómez C, del Monte A, Wittner M, Waller AK, Foster HR, López-Otín C, Johnson RS, Nerlov C, Ghevaert C, Vainchenker W, Louache F, Andrés V, Méndez-Ferrer S. Remodeling of bone marrow hematopoietic stem cell niches promotes myeloid cell expansion during premature or physiological aging. Cell Stem Cell 2019;25:407–418.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nikolich-Žugich J. The twilight of immunity: emerging concepts in aging of the immune system review-article. Nat Immunol 2018;19:10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Franceschi C, Bonafè M, Valensin S, Olivieri F, de Luca M, Ottaviani E, de Benedictis G. Inflamm-aging. An evolutionary perspective on immunosenescence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;908:244–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goronzy JJ, Li G, Yang Z, Weyand CM. The Janus head of T cell aging—autoimmunity and immunodeficiency. Front Immunol 2013;4:131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network . Global burden of disease study 2017 results.

- 7. Witztum JL, Lichtman AH. The influence of innate and adaptive immune responses on atherosclerosis. Annu Rev Pathol 2014;9:73–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Winkels H, Ehinger E, Vassallo M, Buscher K, Dinh HQ, Kobiyama K, Hamers AAJ, Cochain C, Vafadarnejad E, Saliba AE, Zernecke A, Pramod AB, Ghosh AK, Michel NA, Hoppe N, Hilgendorf I, Zirlik A, Hedrick CC, Ley K, Wolf D. Atlas of the immune cell repertoire in mouse atherosclerosis defined by single-cell RNA-sequencing and mass cytometry. Circ Res 2018;122:1675–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cochain C, Vafadarnejad E, Arampatzi P, Pelisek J, Winkels H, Ley K, Wolf D, Saliba AE, Zernecke A. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals the transcriptional landscape and heterogeneity of aortic macrophages in murine atherosclerosis. Circ Res 2018;122:1661–1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Okunrintemi V, Tibuakuu M, Virani SS, Sperling LS, Volgman AS, Gulati M, Cho L, Leucker TM, Blumenthal RS, Michos ED. Sex differences in the age of diagnosis for cardiovascular disease and its risk factors among US adults: trends from 2008 to 2017, the medical expenditure panel survey. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9:e018764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gruber S, Hendrikx T, Tsiantoulas D, Ozsvar-Kozma M, Göderle L, Mallat Z, Witztum JL, Shiri-Sverdlov R, Nitschke L, Binder CJ. Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin G promotes atherosclerosis and liver inflammation by suppressing the protective functions of B-1 cells. Cell Rep 2016;14:2348–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Depuydt MAC, Prange KHM, Slenders L, Örd T, Elbersen D, Boltjes A, de Jager SC, Asselbergs FW, de Borst GJ, Aavik E, Lönnberg T, Lutgens E, Glass CK, den Ruijter HM, Kaikkonen MU, Bot I, Slütter B, van der Laan SW, Yla-Herttuala S, Mokry M, Kuiper J, de Winther MPJ, Pasterkamp G. Microanatomy of the human atherosclerotic plaque by single-cell transcriptomics. Circ Res 2020;127:1437–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Douna H, Amersfoort J, Schaftenaar FH, Kröner MJ, Kiss MG, Slütter B, Depuydt MAC, Bernabé Kleijn MNA, Wezel A, Smeets HJ, Yagita H, Binder CJ, Bot I, van Puijvelde GHM, Kuiper J, Foks AC. B- and T-lymphocyte attenuator stimulation protects against atherosclerosis by regulating follicular B cells. Cardiovasc Res 2020;116:295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DePasquale EAK, Schnell DJ, van Camp PJ, Valiente-Alandí Í, Blaxall BC, Grimes HL, Singh H, Salomonis N. Doubletdecon: deconvoluting doublets from single-cell RNA-sequencing data. Cell Rep 2019;29:1718–1727.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tabula Muris Consortium . A single-cell transcriptomic atlas characterizes ageing tissues in the mouse. Nature 2020;583:590–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Frasca D, Diaz A, Romero M, Blomberg BB. The generation of memory B cells is maintained, but the antibody response is not, in the elderly after repeated influenza immunizations. Vaccine 2016;34:2834–2840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hume DA, Summers KM, Raza S, Baillie JK, Freeman TC. Functional clustering and lineage markers: insights into cellular differentiation and gene function from large-scale microarray studies of purified primary cell populations. Genomics 2010;95:328–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Saigusa R, Winkels H, Ley K. T cell subsets and functions in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2020;17:387–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mingueneau M, Kreslavsky T, Gray D, Heng T, Cruse R, Ericson J, Bendall S, Spitzer MH, Nolan GP, Kobayashi K, von Boehmer H, Mathis D, Benoist C; Immunological Genome Consortium; Best AJ, Knell J, Goldrath A, Joic V, Koller D, Shay T, Regev A, Cohen N, Brennan P, Brenner M, Kim F, Nageswara Rao T, Wagers A, Heng T, Ericson J, Rothamel K, Ortiz-Lopez A, Mathis D, Benoist C, Bezman NA, Sun JC, Min-Oo G, Kim CC, Lanier LL, Miller J, Brown B, Merad M, Gautier EL, Jakubzick C, Randolph GJ, Monach P, Blair DA, Dustin ML, Shinton SA, Hardy RR, Laidlaw D, Collins J, Gazit R, Rossi DJ, Malhotra N, Sylvia K, Kang J, Kreslavsky T, Fletcher A, Elpek K, Bellemare-Pelletier A, Malhotra D, Turley S. The transcriptional landscape of αβ T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol 2013;14:619–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Winkels H, Ghosheh Y, Kobiyama K, Kiosses WB, Orecchioni M, Ehinger E, Suryawanshi V, La Mata S H-D, Marchovecchio P, Riffelmacher T, Thiault N, Kronenberg M, Wolf D, Seumois G, Vijayanand P, Ley K. Thymus-derived CD4 + CD8 + cells reside in mediastinal adipose tissue and the aortic arch. J Immunol 2021;207:2720–2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kirchner J, Bevan MJ. ITM2A is induced during thymocyte selection and T cell activation and causes downregulation of CD8 when overexpressed in CD4+CD8+ double positive thymocytes. J Exp Med 1999;190:217–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aliahmad P, Seksenyan A, Kaye J. The many roles of TOX in the immune system. Curr Opin Immunol 2012;24:173–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ricardo Miragaia AJ, Gomes T, Chomka A, Haniffa M, Powrie F, Teichmann SA. Single-cell transcriptomics of regulatory T cells reveals trajectories of tissue adaptation. Immunity 2019;50:493–504.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mogilenko DA, Shpynov O, Andhey PS, Arthur L, Swain A, Esaulova E, Brioschi S, Shchukina I, Kerndl M, Bambouskova M, Yao Z, Laha A, Zaitsev K, Burdess S, Gillfilan S, Stewart SA, Colonna M, Artyomov MN. Comprehensive profiling of an aging immune system reveals clonal GZMK+ CD8+ T cells as conserved hallmark of inflammaging. Immunity 2020;54:99–115.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Welsh GI, Miyamoto S, Priced NT, Safer B, Proud CG. T-cell activation leads to rapid stimulation of translation initiation factor eIF2B and inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3. J Biol Chem 1996;271:11410–11413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ribot JC, de Barros A, Pang DJ, Neves JF, Peperzak V, Roberts SJ, Girardi M, Borst J, Hayday AC, Pennington DJ, Silva-Santos B. CD27 is a thymic determinant of the balance between interferon-γ- and interleukin 17-producing γδ T cell subsets. Nat Immunol 2009;10:427–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sage AP, Tsiantoulas D, Binder CJ, Mallat Z. The role of B cells in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019;16:180–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Fowler T, Garruss AS, Ghosh A, De S, Becker KG, Wood WH, Weirauch MT, Smale ST, Aronow B, Sen R, Roy AL. Divergence of transcriptional landscape occurs early in B cell activation. Epigenetics Chromatin 2015;8:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sun J, Wang J, Pefanis E, Chao J, Rothschild G, Tachibana I, Chen JK, Ivanov II, Rabadan R, Takeda Y, Basu U. Transcriptomics identify CD9 as a marker of murine IL-10-competent regulatory B cells. Cell Rep 2015;13:1110–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Dambuza IM, He C, Choi JK, Yu CR, Wang R, Mattapallil MJ, Wingfield PT, Caspi RR, Egwuagu CE. IL-12p35 induces expansion of IL-10 and IL-35-expressing regulatory B cells and ameliorates autoimmune disease. Nat Commun 2017;8:719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thompson MR, Xu D, Williams BRG. ATF3 transcription factor and its emerging roles in immunity and cancer. J Mol Med 2009;87:1053–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Masle-Farquhar E, Peters TJ, Miosge LA, Parish IA, Weigel C, Oakes CC, Reed JH, Goodnow CC. Uncontrolled CD21low age-associated and B1 B cell accumulation caused by failure of an EGR2/3 tolerance checkpoint. Cell Rep 2022;38:110259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rubtsov AV, Rubtsova K, Fischer A, Meehan RT, Gillis JZ, Kappler JW, Marrack P. Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7)-driven accumulation of a novel CD11c+ B-cell population is important for the development of autoimmunity. Blood 2011;118:1305–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hao Y, O’Neill P, Naradikian MS, Scholz JL, Cancro MP. A B-cell subset uniquely responsive to innate stimuli accumulates in aged mice. Blood 2011;118:1294–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Cancro MP. Age-associated B cells. Annu Rev Immunol 2020;38:315–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Knode LMR, Naradikian MS, Myles A, Scholz JL, Hao Y, Liu D, Ford ML, Tobias JW, Cancro MP, Gearhart PJ. Age-associated B cells express a diverse repertoire of VH and vκ genes with somatic hypermutation. J Immunol 2017;198:1921–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rubtsov AV, Rubtsova K, Kappler JW, Jacobelli J, Friedman RS, Marrack P. CD11c-expressing B cells are located at the T cell/B cell border in spleen and are potent APCs. J Immunol 2015;195:71–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gu C, Yao J, Sun P. Dynamin 3 suppresses growth and induces apoptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells by activating inducible nitric oxide synthase production. Oncol Lett 2017;13:4776–4784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Minnich M, Tagoh H, Bönelt P, Axelsson E, Fischer M, Cebolla B, Tarakhovsky A, Nutt SL, Jaritz M, Busslinger M. Multifunctional role of the transcription factor Blimp-1 in coordinating plasma cell differentiation. Nat Immunol 2016;17:331–343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gou B, Chu X, Xiao Y, Liu P, Zhang H, Gao Z, Song M. Single-cell analysis reveals transcriptomic reprogramming in aging cardiovascular endothelial cells. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022;9:900978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Xu Q, Liu M, Zhang J, Xue L, Zhang G, Hu C, Wang Z, He S, Chen L, Ma K, Liu X, Zhao Y, Lv N, Liang S, Zhu H, Xu N, Xu Q, Liu M, Zhang J, Xue L, Zhang G, Hu C, Wang Z, He S, Chen L, Ma K, Liu X, Zhao Y, Lv N, Liang S, Zhu H, Xu N. Overexpression of KLF4 promotes cell senescence through microRNA-203-survivin-p21 pathway. Oncotarget 2016;7:60290–60302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tong LQ, Toliver-Kinsky T, Edwards M, Rassin DK, Werrbach-Perez K, Regino Perez-Polo J. Attenuated transcriptional responses to oxidative stress in the aged rat brain. J Neurosci Res 2002;70:318–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Koltsova EK, Hedrick CC, Ley K. Myeloid cells in atherosclerosis: a delicate balance of anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory mechanisms. Curr Opin Lipidol 2013;24:371–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Willemsen L, Winther MP. Macrophage subsets in atherosclerosis as defined by single-cell technologies. J Pathol 2020;250:705–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lim HY, Lim SY, Tan CK, Thiam CH, Goh CC, Carbajo D, Chew SHS, See P, Chakarov S, Wang XN, Lim LH, Johnson LA, Lum J, Fong CY, Bongso A, Biswas A, Goh C, Evrard M, Yeo KP, Basu R, Wang JK, Tan Y, Jain R, Tikoo S, Choong C, Weninger W, Poidinger M, Stanley RE, Collin M, Tan NS, Ng LG, Jackson DG, Ginhoux F, Angeli V. Hyaluronan receptor LYVE-1-expressing macrophages maintain arterial tone through hyaluronan-mediated regulation of smooth muscle cell collagen. Immunity 2018;49:326–341.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zernecke A, Erhard F, Weinberger T, Schulz C, Ley K, Saliba A-E, Cochain C. Integrated single-cell analysis-based classification of vascular mononuclear phagocytes in mouse and human atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Res 2023;119:1676–1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhang W, Zhao J, Wang R, Jiang M, Ye Q, Smith AD, Chen J, Shi Y. Macrophages reprogram after ischemic stroke and promote efferocytosis and inflammation resolution in the mouse brain. CNS Neurosci Ther 2019;25:1329–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kadl A, Meher AK, Sharma PR, Lee MY, Doran AC, Johnstone SR, Elliott MR, Gruber F, Han J, Chen W, Kensler T, Ravichandran KS, Isakson BE, Wamhoff BR, Leitinger N. Identification of a novel macrophage phenotype that develops in response to atherogenic phospholipids via Nrf2. Circ Res 2010;107:737–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rahmatpanah F, Agrawal S, Scarfone VM, Kapadia S, Mercola D, Agrawal A. Transcriptional profiling of age-associated gene expression changes in human circulatory CD1c+ myeloid dendritic cell subset. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2019;74:9–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Naradikian MS, Myles A, Beiting DP, Roberts KJ, Dawson L, Herati RS, Bengsch B, Linderman SL, Stelekati E, Spolski R, Wherry EJ, Hunter C, Hensley SE, Leonard WJ, Cancro MP. Cutting edge: IL-4, IL-21, and IFN-γ interact to govern T-bet and CD11c expression in TLR-activated B cells. J Immunol 2016;197:1023–1028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Johnson JL, Rosenthal RL, Knox JJ, Myles A, Naradikian MS, Madej J, Kostiv M, Rosenfeld AM, Meng W, Christensen SR, Hensley SE, Yewdell J, Canaday DH, Zhu J, McDermott AB, Dori Y, Itkin M, Wherry EJ, Pardi N, Weissman D, Naji A, Prak ETL, Betts MR, Cancro MP. The transcription factor T-bet resolves memory B cell subsets with distinct tissue distributions and antibody specificities in mice and humans. Immunity 2020;52:842–855.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kim K, Shim D, Lee JS, Zaitsev K, Williams JW, Kim K-W, Jang M-Y, Seok Jang H, Yun TJ, Lee SH, Yoon WK, Prat A, Seidah NG, Choi J, Lee S-P, Yoon S-H, Nam JW, Seong JK, Oh GT, Randolph GJ, Artyomov MN, Cheong C, Choi J-H. Transcriptome analysis reveals nonfoamy rather than foamy plaque macrophages are proinflammatory in atherosclerotic murine models. Circ Res 2018;123:1127–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. da Lin J, Nishi H, Poles J, Niu X, Mccauley C, Rahman K, Brown EJ, Yeung ST, Vozhilla N, Weinstock A, Ramsey SA, Fisher EA, Loke P. Single-cell analysis of fate-mapped macrophages reveals heterogeneity, including stem-like properties, during atherosclerosis progression and regression. JCI Insight 2019;4:e124574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Grievink HW, Smit V, Huisman BW, Gal P, Yavuz Y, Klerks C, Binder CJ, Bot I, Kuiper J, Foks AC, Moerland M. Cardiovascular risk factors: the effects of ageing and smoking on the immune system, an observational clinical study. Front Immunol 2022;13:968815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Márquez EJ, han Chung C, Marches R, Rossi RJ, Nehar-Belaid D, Eroglu A, Mellert DJ, Kuchel GA, Banchereau J, Ucar D. Sexual-dimorphism in human immune system aging. Nat Commun 2020;11:751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]