Abstract

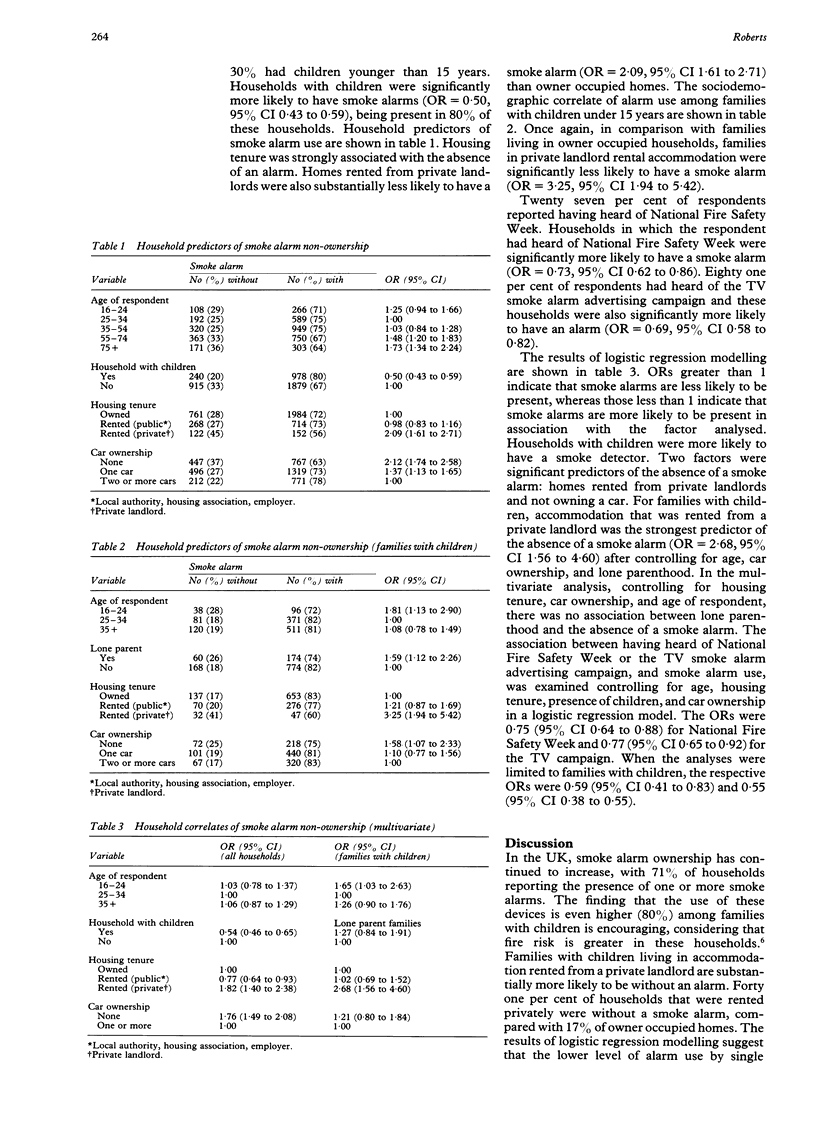

OBJECTIVE: To determine the prevalence of smoke alarm use among families with children and to identify household factors that predict the absence of a smoke alarm. DESIGN: Cross sectional analysis of data collected in the September and November 1995 Omnibus Survey, conducted by the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys in the UK. SUBJECTS: A random sample of British households. Interviews were completed with 4,043 householders. The response rate was 78%. RESULTS: 29% of British households do not have a smoke alarm and smoke alarms were absent in 20% of households with children under 15 years. A smoke alarm was absent in 41% of privately rented homes compared with 17% of owner occupied homes. Living in private rental accommodation was the strongest household predictor of the absence of a smoke alarm (odds ratio = 3.25, 95% confidence interval 1.94 to 5.42). Householders who had heard of National Fire Safety Week or the TV smoke alarm advertising campaign were significantly more likely to have a smoke alarm. The apparent effect of these campaigns was greatest in families with children. CONCLUSIONS: Smoke alarm use has continued to increase but a substantial proportion of British homes still do not have smoke alarms. Homes at greatest risk of residential fire are the least likely to have an alarm. Health professionals may be able to increase smoke alarm use among families with children, by counselling families about the benefits of smoke alarms. They may also be effective in this regard by lobbying local councils, houseing associations, or private landlords to install alarms in all properties and by advocating for national legislation.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- McCabe M., Sibert J. Smoke detectors save lives. BMJ. 1990 Oct 27;301(6758):982–982. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6758.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLoughlin E., Marchone M., Hanger L., German P. S., Baker S. P. Smoke detector legislation: its effect on owner-occupied homes. Am J Public Health. 1985 Aug;75(8):858–862. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.8.858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller R. E., Reisinger K. S., Blatter M. M., Wucher F. Pediatric counseling and subsequent use of smoke detectors. Am J Public Health. 1982 Apr;72(4):392–393. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.4.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara F. P. Traumatic deaths of children in the United States: currently available prevention strategies. Pediatrics. 1985 Mar;75(3):456–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts I. Deaths of children in house fires. BMJ. 1995 Nov 25;311(7017):1381–1382. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7017.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan C. W., Bangdiwala S. I., Linzer M. A., Sacks J. J., Butts J. Risk factors for fatal residential fires. N Engl J Med. 1992 Sep 17;327(12):859–863. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199209173271207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas K. A., Hassanein R. S., Christophersen E. R. Evaluation of group well-child care for improving burn prevention practices in the home. Pediatrics. 1984 Nov;74(5):879–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]