OBJECTIVES OF PREFERRED PRACTICE PATTERN® GUIDELINES

As a service to its members and the public, the American Academy of Ophthalmology has developed a series of Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines that identify characteristics and components of quality eye care. Appendix 1 describes the core criteria of quality eye care.

The Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines are based on the best available scientific data as interpreted by panels of knowledgeable health professionals. In some instances, such as when results of carefully conducted clinical trials are available, the data are particularly persuasive and provide clear guidance. In other instances, the panels have to rely on their collective judgment and evaluation of available evidence.

These documents provide guidance for the pattern of practice, not for the care of a particular individual.

While they should generally meet the needs of most patients, they cannot possibly best meet the needs of all patients. Adherence to these PPPs will not ensure a successful outcome in every situation. These practice patterns should not be deemed inclusive of all proper methods of care or exclusive of other methods of care reasonably directed at obtaining the best results. It may be necessary to approach different patients’ needs in different ways. The physician must make the ultimate judgment about the propriety of the care of a particular patient in light of all of the circumstances presented by that patient. The American Academy of Ophthalmology is available to assist members in resolving ethical dilemmas that arise in the course of ophthalmic practice.

Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines are not medical standards to be adhered to in all individual situations.

The Academy specifically disclaims any and all liability for injury or other damages of any kind, from negligence or otherwise, for any and all claims that may arise out of the use of any recommendations or other information contained herein.

References to certain drugs, instruments, and other products are made for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to constitute an endorsement of such. Such material may include information on applications that are not considered community standard, that reflect indications not included in approved U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labeling, or that are approved for use only in restricted research settings. The FDA has stated that it is the responsibility of the physician to determine the FDA status of each drug or device he or she wishes to use, and to use them with appropriate patient consent in compliance with applicable law.

Innovation in medicine is essential to ensure the future health of the American public, and the Academy encourages the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic methods that will improve eye care. It is essential to recognize that true medical excellence is achieved only when the patients’ needs are the foremost consideration.

All Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines are reviewed by their parent panel annually or earlier if developments warrant and updated accordingly. To ensure that all PPPs are current, each is valid for 5 years from the approved by date unless superseded by a revision. Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines are funded by the Academy without commercial support. Authors and reviewers of PPPs are volunteers and do not receive any financial compensation for their contributions to the documents. The PPPs are externally reviewed by experts and stakeholders, including consumer representatives, before publication. The PPPs are developed in compliance with the Council of Medical Specialty Societies’ Code for Interactions with Companies. The Academy has Relationship with Industry Procedures (available at www.aao.org/about-preferred-practice-patterns) to comply with the Code.

The intended users of Section I of the Pediatric Eye Evaluations PPP are physicians, nurses, and other providers who perform eye and vision screening. The intended users of Section II of the Pediatric Eye Evaluations PPP are ophthalmologists.

METHODS AND KEY TO RATINGS

Preferred Practice Pattern guidelines should be clinically relevant and specific enough to provide useful information to practitioners. Where evidence exists to support a recommendation for care, the recommendation should be given an explicit rating that shows the strength of evidence. To accomplish these aims, methods from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network1 (SIGN) and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation2 (GRADE) group are used. GRADE is a systematic approach to grading the strength of the total body of evidence that is available to support recommendations on a specific clinical management issue. Organizations that have adopted GRADE include SIGN, the World Health Organization, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the American College of Physicians.3

All studies used to form a recommendation for care are graded for strength of evidence individually, and that grade is listed with the study citation.

- To rate individual studies, a scale based on SIGN1 is used. The definitions and levels of evidence to rate individual studies are as follows:

I++ High-quality meta-analyses, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), or RCTs with a very low risk of bias I+ Well-conducted meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a low risk of bias I− Meta-analyses, systematic reviews of RCTs, or RCTs with a high risk of bias II++ High-quality systematic reviews of case-control or cohort studies

High-quality case-control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causalII+ Well-conducted case-control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal II− Case-control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal III Nonanalytic studies (e.g., case reports, case series) - Recommendations for care are formed based on the body of the evidence. The body of evidence quality ratings are defined by GRADE2 as follows:

Good quality Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Insufficient quality Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Any estimate of effect is very uncertain - Key recommendations for care are defined by GRADE2 as follows:

Strong recommendation Used when the desirable effects of an intervention clearly outweigh the undesirable effects or clearly do not Discretionary recommendation Used when the trade-offs are less certain—either because of low-quality evidence or because evidence suggests that desirable and undesirable effects are closely balanced The Highlighted Recommendations for Care section lists points determined by the PPP Panel to be of particular importance to vision and quality of life outcomes.

All recommendations for care in this PPP were rated using the system described above. Ratings are embedded throughout the PPP main text in italics.

Literature searches to update the PPP were undertaken in July 2021 and May 2022 in the PubMed database. Complete details of the literature searches are available in Appendix 4.

HIGHLIGHTED RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CARE

| Amblyopia meets the World Health Organization criteria for a disease that benefits from screening because it is an important health problem for which there is an accepted treatment, it has a recognizable latent or early symptomatic stage, and a suitable test or examination is available to diagnose it before permanent vision loss occurs. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends vision screening at least once for all children aged 3 to 5 years to detect amblyopia or its risk factors.4 |

| Vision testing with single optotypes is likely to overestimate visual acuity in a patient who has amblyopia. A more accurate assessment of monocular visual acuity is obtained by presenting a line of optotypes or a single optotype with crowding bars that surround (or crowd) the optotype being identified. |

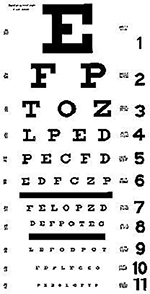

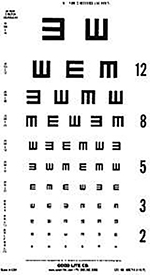

| The choice and arrangement of optotypes (letters, numbers, symbols) on an eye chart can significantly affect the visual acuity score obtained. The preferred optotypes are LEA symbols, HOTV, and Sloan letters because they are standardized and validated.5, 6 |

| Instrument-based screening techniques, such as photoscreening and autorefraction, are useful for assessing amblyopia and reduced-vision risk factors for children ages 1 to 5 years, as this is a critical time for visual development.7 Instrument-based screening can also be used for older children who are unable to participate in optotype-based screening. This type of screening has been shown to be useful in detecting amblyopia risk factors in children with developmental disabilities.8 |

| Vision screening should be performed at an early age and at regular intervals throughout childhood to detect amblyopia risk factors and refractive errors. The elements of vision screening vary depending on the age and level of cooperation of the child, as shown in Table 1. |

TABLE 1.

Age-Appropriate Methods for Pediatric Vision Screening and Criteria for Referral

| Method | Indications for Referral | Recommended Age | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newborn–6 months | 6–12 months | 1–3 years | 3–4 years | 4–5 years | Every 1–2 yrs after age 5 | ||

| Red reflex test | Absent, white, dull, opacified, or asymmetric | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| External inspection | Structural abnormality (e.g., ptosis) | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Pupillary examination | Irregular shape, unequal size, poor or unequal reaction to light | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Fix and follow | Failure to fix and follow | Cooperative infant ≥3 months | • | • | |||

| Corneal light reflection | Asymmetric or displaced | Cooperative infant ≥3 months | • | • | • | • | • |

| Instrument-based screening* | Failure to meet screening criteria | Cooperative infant ≥6 months | • | • | • | • | |

| Cover test | Refixation movement of uncovered eye | • | • | • | |||

| Distance visual acuity† (monocular) | Worse than 20/50 with either eye or 2 lines of difference between the eyes | • | • | • | |||

| Worse than 20/40 with either eye or 2 lines of difference between the eyes | • | • | |||||

SOURCE: Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, eds. 2017, Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children and Adolescents. 4th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2017.

NOTE: These recommendations are based on panel consensus. If screening is inconclusive or unsatisfactory, the child should be retested within 6 months; if inconclusive on retesting, or if retesting cannot be performed, referral for a comprehensive eye evaluation is indicated.9

Subjective visual acuity testing is preferred to instrument-based screening in children who are able to participate reliably. Instrument-based screening is useful for some young children and those with developmental delays.

Refractive correction should be prescribed for children according to the guidelines in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Guidelines for Refractive Correction in Infants and Young Children

| Condition | Refractive Errors (diopters) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age <1 year | Age 1 to <2 years | Age 2 to <3 years | Age 3 to <4 years | |

|

| ||||

| Isoametropia | ||||

| (similar refractive error in both eyes) | ||||

| Myopia | 5.00 or more | 4.00 or more | 3.00 or more | 2.50 or more |

|

| ||||

| Hyperopia (no manifest deviation) | 6.00 or more | 5.00 or more | 4.50 or more | 3.50 or more |

|

| ||||

| Hyperopia with esotropia | 1.50 or more | 1.00 or more | 1.00 or more | 1.00 or more |

|

| ||||

| Astigmatism | 3.00 or more | 2.50 or more | 2.00 or more | 1.50 or more |

|

| ||||

| Anisometropia (without strabismus)* | ||||

| Myopia | 4.00 or more | 3.00 or more | 3.00 or more | 2.50 or more |

|

| ||||

| Hyperopia | 2.50 or more | 2.00 or more | 1.50 or more | 1.50 or more |

|

| ||||

| Astigmatism | 2.50 or more | 2.00 or more | 2.00 or more | 1.50 or more |

NOTE: These values were generated by consensus and are based solely on professional experience and clinical impressions because there are no scientifically rigorous published data for guidance. The exact values are unknown and may differ among age groups; they are presented as general guidelines that should be tailored to the individual child. Specific guidelines for older children are not provided because refractive correction is determined by the severity of the refractive error, visual acuity, and visual symptoms.

The values represent the minimum difference in the magnitude of refractive error between eyes that would prompt refractive correction in the absence of other abnormalities. Thresholds for correction of anisometropia should be lower if the child has strabismus or amblyopia.

Section I. Vision Screening in the Primary Care and Community Setting

INTRODUCTION

Vision screening for children is an evaluation to detect reduced visual acuity or risk factors that threaten the healthy growth and development of the eye and visual system.

Vision screening in the primary care setting is usually performed by a nurse or other trained health professional during routine pediatric examinations. Vision screening in the community setting may be performed in preschools, in daycares, at schools, or at health fairs. Community screenings can be performed by health professionals or trained lay personnel. Lay personnel can be adequately trained to perform vision screening to an acceptable degree of accuracy.12 Screening by non-ophthalmologists using the Brückner’s Test has also been shown to accurately identify significant refractive errors in children.13

PATIENT POPULATION

Infants and children through 17 years of age.

OBJECTIVES FOR VISION SCREENING

Educate screening personnel

Assess vision, ocular alignment, and the presence of ocular structural abnormalities

Communicate the screening results and follow-up plan to the family/caregiver in a manner that follows their language and cultural needs

Refer all children who either fail screening or who are unable to cooperate for testing for a comprehensive eye examination

Verify that the recommended comprehensive eye examination has occurred

BACKGROUND

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF VISION-THREATENING CHILDHOOD OCULAR CONDITIONS

The frequency of ocular conditions that cause severe vision impairment or blindness in children varies considerably around the world (see Table 3).14, 15 In low-income countries, cataracts and corneal conditions resulting from infectious disease or vitamin A deficiency are frequent causes of severe vision impairment and blindness. In middle-income countries, retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is an important cause. In high-income countries, including the United States, conditions of the optic nerve and higher visual pathways, frequently associated with prematurity, are major causes of severe vision impairment and blindness. Additionally, cataract, hereditary diseases (particularly retinal dystrophies), and congenital abnormalities are important causes worldwide. In high-income countries, severe vision-threatening eye problems observed within the first year of life include congenital cataract, ROP, congenital glaucoma, retinoblastoma (a vision- and life-threatening malignancy), and cerebral visual impairment. Accurate incidence and prevalence data on many of these conditions are lacking because they are uncommon, and obtaining good estimates of incidence and prevalence would require very large, and ideally population-based, studies.14, 15 Other more common childhood ocular problems causing vision impairment include strabismus, amblyopia, refractive problems, and uveitis. Table 3 lists prevalence and incidence data for these childhood ocular conditions.

TABLE 3.

Visually Significant Childhood Ocular Conditions

| Condition | Frequency |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Refractive errors | |

| Myopia (-0.75 D or more in eye with lesser refractive error) | 0.7%-9.2%16, 17,18 (prevalence in children aged 5–17 years) |

| Myopia (more than -2.0 D) | 0.2%-2%19 (prevalence in children aged 3–5 years) |

| Hyperopia (+3.0 D or more in eye with lesser refractive error) | 4%-9%16, 17 (prevalence in children aged 5–17 years) |

| Hyperopia (more than +3.25 D) | 6%-7%19 (prevalence in children aged 3–5 years) |

| Astigmatism (worse eye cylinder power 3.0 D or more) | 0.5%-3%16, 20 (prevalence in children aged 5–17 years) |

| Astigmatism (cylinder power more than 1.5 D) | 4%-11%19 (prevalence in children aged 3–5 years) |

|

| |

| Amblyopia | 0.8%-3%21–23 (prevalence in children aged 6–72 months) |

|

| |

| Strabismus | 0.08%-4.6%19, 21–25 (prevalence in children aged 6–72 months) 1.2%-6.8% (prevalence in children aged 6–17 years)26–32 |

|

| |

| Cerebral visual impairment, including traumatic brain injury | Accurate prevalence or incidence data are lacking |

|

| |

| Cataract | 0.02%33, 34 (prevalence in children aged 0–1 year) 0.1%24 (prevalence in children aged 6 months to 6 years) 0.42%35 (prevalence in children aged 6 to 15 years) |

|

| |

| ROP | 8.6%-9.2%36–38 (incidence of severe ROP in cohorts 1000–1250 g [mean] at birth) 15.2%-18.3%39, 40 (incidence of severe ROP in cohorts 800–999 g [mean] at birth) |

|

| |

| Congenital glaucoma | 0.0015%-0.0054%41, 42 (prevalence in newborns) |

|

| |

| Retinoblastoma | 0.0011%-0.0013%43–46 (yearly incidence in children aged <5 years) 0.00036%-0.00041%47, 48 (yearly incidence in children aged <15 years) |

|

| |

| Pediatric uveitis | Incidence 0.004%49 (yearly incidence in children aged <16 years) |

D = diopter; g = grams; ROP = retinipathy of prematurity.

Strabismus is a binocular misalignment (see Esotropia and Exotropia PPP50). The common types of strabismus are esotropia (inwardly deviating eyes) and exotropia (outwardly deviating eyes). Prevalence increases with age during childhood for both types.25, 30 In the United States, the prevalence rates are similar for esotropia and exotropia.22, 25, 51 However, in Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, and China, and in children of East Asian descent in the United States, exotropia is more frequent than esotropia.24, 25, 30, 52–54

Amblyopia is an abnormality of visual development characterized by decreased best-corrected visual acuity in a normal eye or less frequently, in an eye with a structural abnormality in which visual acuity is not fully attributable to the structural anomaly of the eye (see Amblyopia PPP).55 Amblyopia may be unilateral or bilateral and is best treated in early childhood for optimal outcomes. However, amblyopia may also be treated and possibly improved even in the teenage years.56 The prevalence of amblyopia varies by race/ethnicity, with several large studies showing that Latinx children are more likely to have amblyopia than Asian, White or Black children.21, 22, 57, 58, 14 For example, amblyopia was detected in 2.6% of Hispanic/Latinx children and 1.5% of African American children 30 to 72 months old in one study of Los Angeles County children. A global systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of amblyopia from 1950 to 2018 showed that the estimated number of patients with amblyopia worldwide in 2019 was 99.2 million people and is predicted to be 221 million by 2040.59 The most common causes of amblyopia are strabismus (mainly esotropia), and high refractive errors or anisometropia (asymmetric refractive errors). Amblyopia can also occur in conjunction with structural ocular problems.60–63 Uncorrected refractive errors were found to be the leading cause of amblyopia in children age 6 months to 16 years in one large study of almost 40,000 children living in India.64 The odds of having amblyopia are 6.5 to 26 times greater when anisometropia is present and 2.7 to 18 times greater when strabismus is present.24, 27, 65–67 Amblyopia is unusual in children with intermittent exotropia.68 The prevalence of amblyopia in children with developmental delay is sixfold greater than in full-term otherwise healthy children.69 Recent studies found that the prevalence of strabismic amblyopia appears to be similar in left and right eyes; however, most studies confirm a greater percentage (53% to 64%) of anisometropic amblyopia in left eyes.69–71 In the United States, amblyopia affects over 6 million people, and it is responsible for permanently reduced vision in more people under the age of 45 than all other causes of visual disability combined.72

Refractive error is the most common cause of reduced vision in children. Visually important refractive errors include high hyperopia, moderate to high astigmatism, moderate to high myopia, and asymmetric refractive errors (anisometropia). An estimated 5% to 7% of preschool children in the United States have visually significant refractive errors.17, 67 Twenty-five percent of children between the ages of 6 and 18 years use or would benefit from corrective lenses for refractive error or other reasons.17, 73, 74 Incidence rates vary with age, race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status.75

Premature birth is a risk factor for severe visual impairment and blindness in childhood. The most common vision-threatening problem in preterm infants is ROP. The frequency and severity of ROP is inversely related to gestational age and birth weight.76 Preterm infants also have higher rates of amblyopia, strabismus, refractive error, optic atrophy, and cerebral visual impairment. Even preterm children not meeting criteria for ROP screening are at risk for amblyopia.77–83 Children with severe ROP have a lifelong risk of developing glaucoma and retinal detachment.80, 81 Visual impairment from ROP is often accompanied by cerebral palsy, epilepsy, and other motor and intellectual disabilities.81, 84 Experts recognize that, among children with visual disability, cerebral impairment is an important contributor to vision loss. Some studies suggest that at least 25% of children with visual impairment in Europe have a cerebral and/or optic nerve component.85–87 However, there is a lack of robust population-based studies for accurate incidence or prevalence data.

Uveitis, although uncommon, is recognized as an important and treatable cause of ocular morbidity in children.88 Uveitis can be due to many infectious or inflammatory causes;89 the most frequent specific causes are juvenile idiopathic arthritis and toxoplasma retinochoroiditis.90 Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis should have an ophthalmic examination within 1 month of diagnosis of the arthritis to rule out uveitis, and they should have ongoing periodic examinations as defined by the American College of Rheumatology/Arthritis Foundation.91 Prompt diagnosis and treatment of uveitis are critical to preserving visual function, and it is essential to identify any associated systemic infectious or inflammatory disease. Another cause of visual morbidity is keratoconus, which commonly begins during puberty.92, 93 The corneal ectasia progresses most rapidly in young people and, if recognized at this stage, treatment with corneal cross-linking stabilizes the cornea.

RATIONALE FOR PERIODIC VISION SCREENING

The purpose of periodic vision screening and ocular assessment is to identify children who may have eye disorders at a sufficiently early age to allow effective treatment, particularly disorders that contribute to the development of amblyopia. Parents or caregivers may be unaware of the consequences of delayed care.94 Because amblyopia does not always present with signs or symptoms that are apparent to parents or caregivers, children with amblyopia may seem to have normal visual function until formally tested. Amblyopia, therefore, meets the World Health Organization guidelines for a disease that benefits from screening because it is an important health problem for which there is an accepted treatment, it has a recognizable latent or early symptomatic stage, and there is a suitable test or examination available to diagnose the condition.95, 96

Vision screening should be performed periodically throughout childhood.97–108 The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Recommendations for Pediatric Preventive Health Care, or Bright Futures Periodicity, highlight the importance of scheduled vision screening.109 The combined sensitivity of a series of screening encounters is much higher than that of a single screening test, particularly if different methods are used based on the child’s age and abilities.107 In addition, eye problems can present at different stages throughout childhood.

Several governmental and service organizations have developed policies on vision screening, and most clinical authorities, including the American Academy of Ophthalmology, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association of Certified Orthoptists and United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), recommend some form of periodic vision screening for asymptomatic children.108–111 The USPSTF found indirect evidence demonstrating that a number of screening tests can identify many preschool-aged children who have vision problems. It found further indirect evidence suggesting that treatment for amblyopia or unilateral refractive error (with or without amblyopia) is associated with improvement in visual acuity compared with no treatment. However, no randomized controlled trials or cohort studies were identified that explicitly addressed the optimal timing or process of pediatric vision screening from birth to 18 years of age. The 2011 USPSTF Evidence Synthesis report112, 113 and a Cochrane Review114 found insufficient evidence for or against vision screening for asymptomatic children younger than 3 years of age, but they did find evidence supporting vision screening for children ages 3 to 5 years. The 2017 USPSTF report recommends vision screening for children 3 to 5 years of age to detect amblyopia or its risk factors.115 Studies are needed to ascertain whether there are any risks for unintended harm from screening.98

Although there is limited direct evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of preschool vision screening in reducing the prevalence of amblyopia or in improving other health outcomes,111, 114, 116–118 a convincing chain of indirect evidence supports the practice of preschool vision screening. Several methods of vision screening in preschoolers have been shown to be effective in detecting children at risk for amblyopia, and amblyopia treatment results in an improvement in visual acuity relative to no treatment.108, 111, 119, 120 In addition, mounting evidence indicates that successful treatment of visual disability sustains or improves quality of life.121, 122 The earlier amblyopia is detected and properly treated, the higher the likelihood of visual acuity recovery.55, 97–100, 123–128 If untreated or insufficiently treated, amblyopia results in permanent visual loss and may have detrimental consequences in educational achievement, sports participation, psychosocial well-being, and occupational selection.117, 127, 129, 130 The lifelong risk of bilateral vision impairment is approximately double for patients with amblyopia.131 A retrospective study found that vision loss originating from the fellow eye was more likely to occur in children who have amblyopia when compared with children who do not have amblyopia.132 Accidental trauma with injury of the fellow eye was associated with more than one-half of the cases of total vision loss.132 In older subjects, loss of visual acuity in the fellow eye is usually related to retinal abnormalities such as retinal vein occlusion, age-related macular degeneration, and other macular disorders.133 Recognizing such indirect evidence, and despite limitations of direct evidence, expert opinion supports vision screening throughout childhood in primary care and community settings.109, 111

VISION SCREENING PROCESS

The optimal timing and method of pediatric vision screening have not been definitively established. Guidelines for pediatric vision screening continue to evolve as new tests are introduced and new studies are completed.

HISTORY

A history that addresses risk factors for eye problems is important. It is readily obtained in settings where a primary caregiver is likely to be present, but it is more challenging to assess at screenings performed in daycare settings and schools.

Parental/caregiver observations on the overall quality of the child’s vision, eye alignment, and structural features of the eyes and ocular adnexa are invaluable. Poor eye contact by the infant with the caregiver after 8 weeks of age may warrant further assessment. A detailed family history of vision problems, including strabismus, amblyopia, congenital cataract, congenital glaucoma, retinoblastoma, and ocular or systemic genetic disease, should be elicited whenever possible. Special attention should be paid to children with a history of known medical risk factors for the development of vision problems, including prematurity, Down syndrome, and cerebral palsy.134 The presence of neuropsychological conditions or learning issues in school should be sought; if present, a vision problem may be the cause or a contributing factor. At each well-child check or subsequent screening, the screener should ask about the overall quality of the child’s vision. Children who have underlying medical or genetic conditions that place them at higher risk for eye problems should receive a comprehensive ophthalmic examination soon after diagnosis. The parent or caregiver should maintain regular contact with the eye care provider and follow the schedule for future examinations set by that provider.

VISION SCREENING AND REFERRAL PLAN

The elements of vision screening vary depending on the age and level of cooperation of the child (see Table 1). The content of the vision screening may also depend on state and federal mandates, the availability of objective vision-screening devices, and the skills of the examiner. Vision screening is performed in medical, community, and school settings, often by community-based lay screeners. Lay screeners should receive adequate training to carry out specific screening procedures, but they should not be expected to perform more sophisticated elements of an ophthalmic examination.

Primary care providers should perform vision screening of newborns and infants under 6 months of age. Screening should include red reflex testing to detect abnormalities of the ocular media, external inspection of ocular and periocular structures, pupillary examination, and assessment of fixation and following behavior. Findings that would warrant referral of newborns and infants to an ophthalmologist for a comprehensive eye examination following a vision screening are listed in Table 1.

Primary care providers also provide vision screening of older infants and toddlers. By 6 months of age, children should have normal binocular alignment.135, 136 Instrument-based screening with photoscreening and autorefraction devices can be valuable in detecting amblyopia risk factors by age 1 year because the tests are rapid and noninvasive, and minimal cooperation is required on the part of the child.108 These particular vision-screening devices measure risk factors for amblyopia, not the actual visual acuity, and estimates of refractive error should not be converted to visual acuity values. Newer retinal polarization scanners are also available and are designed to detect amblyopia and strabismus directly by detecting the absence of bifoveal fixation.137

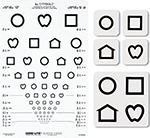

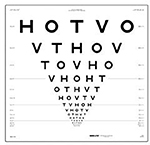

Many 3-year-old children are able to participate in subjective visual acuity screening; however, accurate monocular visual acuity testing is more successful in 4-year-olds.108 After age 4 years, visual acuity testing becomes the preferred method of vision screening. Several tests with appropriate optotypes for young children are available, but the LEA SYMBOLS® or HOTV letters are the preferred ones.119, 138 Several other symbol charts, including Allen figures, the Lighthouse chart, and the Kindergarten (Sailboat) Eye Chart use optotypes that have not been validated and/or are not presented according to recommended standards for eye chart design 139, 140 The desirable optotypes for older children are Sloan letters.11 Snellen letters are less desirable because the individual letters are not of equal legibility and the spacing of the letters does not always meet World Health Organization standards.140–144 See Section II. Comprehensive Ophthalmic Evaluation, and Appendix 2 of this PPP, for detailed information on visual acuity testing charts. Visual acuity testing should be performed monocularly and with habitual refractive correction in place. Ideally, the fellow eye should be covered with an adhesive patch or tape. If such occlusion is not available or not tolerated by the child, extra care must be taken to prevent the child from peeking and using the “covered” eye.

Children who fail to complete subjective visual acuity assessment are considered untestable. Untestable preschoolers are at least twice as likely to have vision disorders as testable children who pass a screening. Children who are untestable should be rescreened within 6 months (preferably sooner, if possible) or referred for a comprehensive eye examination. Children who are testable and fail a subjective visual acuity assessment should be referred for a comprehensive eye examination after the first screening failure. Additional findings that would warrant referral of a 3- to 5-year-old child for a comprehensive ophthalmic examination are included in Table 1. Children should continue to have periodic vision screenings throughout childhood and adolescence because problems may arise at later stages of development.145

Appendix 3 provides additional information on red reflex examination, external inspection, pupillary examination, fixation testing, corneal light reflex assessment, cover testing, and instrument-based screening in the primary care setting.

Instrument-Based Vision Screening

Instrument-based vision screening includes photoscreening, autorefraction, and retinal polarization scanners. Instrument-based vision-screening techniques are useful alternatives to visual acuity screening for very young children and children with developmental delays; they compare well with standard vision-testing techniques and cycloplegic refraction in this patient population.105, 111, 119, 146–149 They are not superior to quantitative visual acuity testing for children who are able to participate in those tests. Most instrument-based vision-screening methods detect the presence of risk factors for amblyopia, including strabismus, high or asymmetric refractive errors, media opacities (e.g., cataract), retinal abnormalities (e.g., retinoblastoma), and ptosis.

Photoscreening uses off-axis photography and photorefraction of the eye’s red reflex to evaluate refractive error and identify risk factors in both eyes simultaneously. In the community setting, photoscreening devices have been shown to have reasonably high sensitivity and specificity for amblyopia risk factors, and threshold values for referral can be adjusted based on desired specificity and sensitivity levels.108, 150 A 2005 multicenter study revealed that, within the pediatric office setting, photoscreening was superior to optotype-based screening for children 3 or 4 years of age, and a 2008 study showed that children who underwent their first photoscreening prior to 2 years of age had superior eventual outcomes.114, 147, 151 Instrument-based vision-screening devices have been shown to improve compliance with the recommended vision-screening guidelines by primary care providers.152

Retinal polarization scanning is a newer method of instrument-based vision screening that detects amblyopia directly by performing a binocular retinal polarization scan of the Henle fiber layer to identify reduced binocularity, microstrabismus, and fixation instability without regard to refractive status.153, 154 Additional study is needed to determine how this device compares with existing photoscreeners and autorefractors, not only with regard to detecting amblyopia and amblyopia risk factors but also in identifying persons with clinically significant refractive errors.137, 155, 156

Smartphone applications that utilize photoscreening, optotype-based vision screening and infrared techniques are becoming increasingly available.157–159

Widefield digital imaging of newborn infants is also being considered as a screening tool and preliminary investigations of the role of this modality are underway.159–162

See Appendix 3 for more information on instrument-based screening.

PROVIDERS

Physicians, nurses, ophthalmologists, optometrists, orthoptists, teachers, and lay persons who perform vision screening should be trained to elicit specified risk factors for vision problems, detect structural eye problems, assess visual abilities or acuities at different ages, and/or conduct instrument-based screening.163 Screeners should be trained in the techniques that are used to test younger children and children with neuropsychological conditions or developmental delays. Training and nationally recognized certification on evidence-based vision-screening tools and procedures are available through Prevent Blindness and its affiliates.

SOCIOECONOMIC CONSIDERATIONS

There is consensus that timely and appropriate eye care can significantly improve children’s quality of life and can reduce the burden of eye disease. There is evidence that academic achievement improves as a result of screening and intervention with necessary eyeglasses.164 Timely treatment relies on early diagnosis.50, 55, 165, 166 Several important pediatric eye conditions can be asymptomatic, and children may be unaware and/or unable to express visual symptoms. Many authorities recommend early and regular vision screening to detect these conditions.

Evidence suggests that many children do not receive recommended eye care. In fact, almost 40% of children in the United States have never undergone a vision screening.167, 168 Children from low-income or uninsured families, or in racial and ethnic minority groups, may fare even worse.167–170 Studies indicate that, in general, Latinx and African American children and children living below the federal poverty level are more likely to be uninsured and receive fewer and less intensive services relative to their non-Latinx white or more affluent counterparts.169, 171–173 There is evidence that these race/ethnicity disparities are reflected in eye care services as well as in other health services.75, 171 It is still unclear whether these disparities in eye care services are due to underdiagnosis and undertreatment of certain conditions in minority children, a lower prevalence of treatable eye conditions in certain populations, racial/ethnic differences in access to care or in preferences for treatment, or a combination of these factors.169

Barriers to eye care extend beyond inadequate screening and diagnosis. Screening programs vary in their ability to ensure access to eye examinations and treatment for children who fail screening. In 15 screening programs in the United States, the rate of referred children receiving a follow-up examination was over 70% in four programs but was below 50% in the other 11 programs.174 Barriers to care may include inadequate information, lack of access to care, limited financial means, and insurance coverage and/or reimbursement issues.175, 176 One study showed the value of partnering with school nurses to ensure follow-up care for minority and low-income children.177 A recent Cochrane review concluded that vision screening plus provision of free spectacles improves the number of children who have and wear the spectacles they need compared with providing a prescription only.178 Children with diagnosed eye conditions require greater use of medical services than children without such conditions, and their families incur higher out-of-pocket expenditures.171 In keeping with other measures of disparity in the provision of health services, non-Latinx white children and those from families of higher socioeconomic status may be more likely to obtain follow-up eye care.175

At the state level, legislatures have attempted to close the gap by mandating some form of vision screening for children.179 Legislative efforts have focused primarily on early detection of vision problems in young children. Leaders in these efforts have stressed the importance of funding mechanisms to support such programs, specifically advocating separate and additional coverage for vision screening in primary care offices as a pathway to success.179

The optimal provision of eye and vision care for children involves an organized program of vision screening in the primary care and community settings. It also includes access for comprehensive eye examinations when indicated and provision of refractive correction as needed. A vision-screening program may reduce the risk of persistent amblyopia.180 More studies are needed to assess the prevalence of eye disease among children as well as the impact of these interventions over time and across diverse populations.181

Section II. Comprehensive Pediatric Ophthalmic Examination

INTRODUCTION

The majority of healthy children should have several vision screenings during childhood. Comprehensive eye examinations are not necessary for healthy asymptomatic children who have passed an acceptable vision-screening test, have no subjective visual symptoms, and have no personal or familial risk factors for eye disease.182 It is recommended that children be referred for a comprehensive eye examination if they fail a vision screening, are unable to be tested, have a vision complaint or exhibit observed abnormal visual behavior, or are at risk for the development of eye problems. Children with certain medical conditions (e.g., Down syndrome, prematurity, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, neurofibromatosis) or a family history of amblyopia, strabismus, retinoblastoma, congenital cataracts, or congenital glaucoma are at higher risk for developing eye problems. Health supervision guidelines exist for many of these conditions.183–190 In addition, children with learning disabilities benefit from a comprehensive eye evaluation to rule out the presence of ocular comorbidities.191, 192 Finally, some children who have developmental delays, intellectual disabilities, neuropsychological conditions, and/or behavioral issues that render them untestable by other caregivers benefit greatly from a comprehensive eye examination by an ophthalmologist who is skilled at working with children.

PATIENT POPULATION

Infants and children through age 17 years.

OBJECTIVES FOR COMPREHENSIVE OPHTHALMIC EXAMINATION

Identify risk factors for ocular disease

Identify systemic disease based on associated ocular findings

Identify factors that may predispose to visual loss early in a child’s life

Determine the health status of the eye and the visual system, and assess refractive errors

Discuss the the findings of the examination and their implications with the parent/caregiver, primary care provider and, when appropriate, the patient

Initiate an appropriate management plan (e.g., treatment, counseling, further diagnostic tests, referral, follow-up, and early intervention services* for newborns and children up to age 3 years, or individual education plans in the public school system for children older than 3 years193)

CARE PROCESS

Comprehensive eye examinations differ in technique, instrumentation, and diagnostic capacity for each child, depending on their age, developmental status, level of cooperation, and ability to interact with the examiner. A comprehensive assessment includes a history, eye examination, and other additional tests or evaluations that may be indicated.

HISTORY

Although a thorough history generally includes the following items, the details depend on the patient’s particular problems and needs:

Demographic data, including sex/gender identity, date of birth, and identity of parent/caregiver

* Under U.S. federal law, early intervention services for children of any age with visual impairments are available from public school districts and regional centers.

The identity of the historian, relationship to child, and any language barriers that may exist

The identity of other pertinent health care providers

The chief complaint and reason for the eye evaluation

Current eye problems

Ocular history, including prior eye problems, diseases, diagnoses, and treatments

Systemic history, birth weight, gestational age, prenatal and perinatal history that may be pertinent (e.g., history of infections or substance or drug exposure during pregnancy), past hospitalizations and operations, and general health and development

Current medications and allergies

Family history of ocular conditions and relevant systemic diseases

Social history, including racial and/or ethnic heritage

Review of systems

EXAMINATION

The pediatric eye examination consists of an assessment of the physiologic function and the anatomic status of the eye and visual system. Documentation of the child’s level of cooperation in the examination can be useful in interpreting the results. The order of the examination may vary depending on the child’s level of cooperation. Testing of sensory function should be performed before using any dissociating examination techniques, such as covering an eye to check visual acuity or alignment. Binocular alignment testing should be done prior to cycloplegia. The examination should include the following elements:

Binocular red reflex (Brückner) test

Binocularity/stereoacuity testing

Assessment of fixation pattern and/or visual acuity

Binocular alignment and ocular motility

Visual field testing

Pupillary examination

External examination

Anterior segment examination

Cycloplegic retinoscopy/refraction

Funduscopic examination

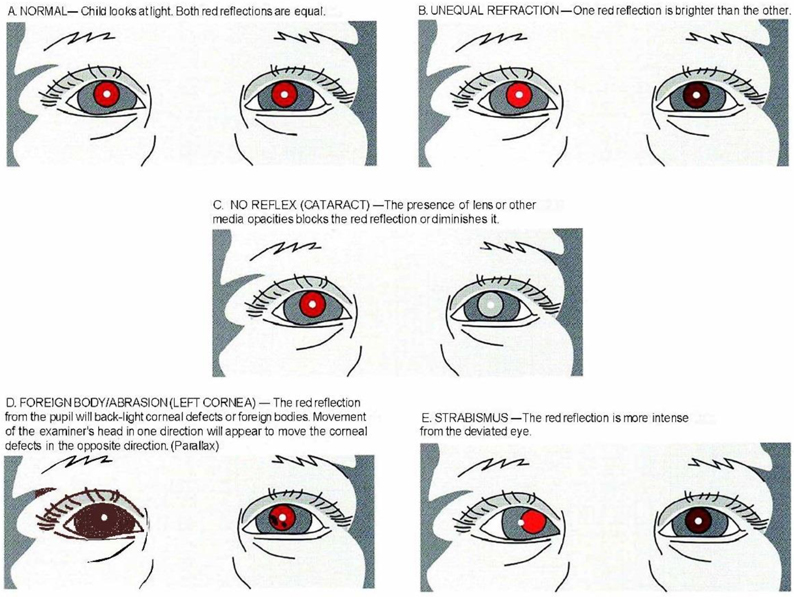

Binocular Red Reflex (Brückner) Test

To perform this test, the room is darkened and the examiner sets the ophthalmoscope lens power at “0” and directs the ophthalmoscope light toward both eyes of the child simultaneously from approximately 18 to 30 inches (45 to 75 centimeters). The Brückner test should be performed prior to pupillary dilation, because subtle differences in the red reflex are difficult to detect once the pupils are dilated.194 To be considered normal, a symmetric red reflex should be observed from both eyes. Opacities within the red reflex, a markedly diminished reflex, the presence of a white or dull reflex, or asymmetry of the red reflexes are all considered abnormal. The appearance of the red reflex varies based on retinal pigmentation and, thus, varies by race/ethnicity; therefore, the emphasis is on symmetry rather than color of the reflex. Significant hyperopia will present as an inferiorly placed brighter crescent in the red reflex. Significant myopia presents as a superiorly placed brighter crescent. Screening by non-ophthalmologists using the Brückner test has also been shown to accurately identify significant refractive errors in children.13

Binocularity/Stereoacuity Testing

Binocularity, or binocular vision, has several different components, including sensory fusion, stereopsis, fusional vergence (motor fusion), and other coordinated binocular eye movements. Sensorimotor fusion is sensitive to disruption by amblyopia, strabismus, refractive error, and deprivation. Binocular vision may be affected to different degrees depending on the underlying diagnosis, and tests to evaluate each of these components vary accordingly. The Worth 4-Dot Test is used to evaluate sensory fusion, the Randot Stereo Test is used to evaluate stereopsis, and a prism bar or rotary prism is used to evaluate fusional motor vergence.33, 195 Assessment of stereoacuity is an important component of binocular alignment testing because high-grade stereoacuity is associated with normal alignment.196 Filter-free stereoacuity tests may be comparable to the Randot test and eliminate the need for polarizing lenses.197 Testing of sensory function should be performed before using any dissociating examination techniques (e.g., covering an eye to check monocular visual acuity or cover testing to assess alignment).

Assessment of Fixation Pattern and Visual Acuity

Fixation

Visual acuity measurement of the infant or toddler involves a qualitative assessment of fixation and tracking (following) eye movements. Fixation and following are assessed by drawing the child’s attention to the examiner or caregiver’s face or to a hand-held light, silent toy, or other fixation target and then slowing moving the target. Fixation behavior can be recorded for each eye as “fixes and follows” or “central, steady, and maintained through a smooth pursuit,” along with any qualifying findings, such as fixation that is eccentric, not central, not steady, or not maintained.

Large differences in vision between the eyes can be detected by observing the vigor with which the child objects to occlusion of one eye relative to the other. Children resist covering an eye when the fellow eye has limited vision.198–200 Grading schemes can be used to describe fixation preference. For strabismic patients, fixation pattern is assessed binocularly by determining the length of time that the nonpreferred eye holds fixation. Fixation pattern can be graded by whether the nonpreferred eye will not hold fixation, holds momentarily, holds for a few seconds (or to or through a blink), or spontaneously alternates fixation. For children with small-angle strabismus or no strabismus, the induced tropia test may be done by holding a base-down or base-in prism of 10 to 20 prism diopters over one eye and then over the other eye and noting fixation behavior.200–202 Studies have shown that these tests cannot stand alone as highly accurate screening tests for differentiating amblyopia from normal.199, 203–205 However, when used in a clinical setting and interpreted in the context of other key findings, tests of fixation preference can be useful diagnostic tools to help determine whether there is amblyopia of sufficient severity to warrant treatment.

Qualitative assessment of visual function should be replaced with a recognition visual acuity test based on optotypes (letters, numbers, or symbols) as soon as the child can perform this task reliably.

Visual Acuity

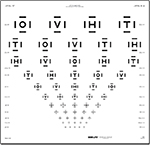

Recognition visual acuity testing, which involves identifying optotypes and consisting of letters, numbers, or symbols, is preferred for assessment of visual acuity to detect amblyopia. The optotypes may be presented on a wall chart, computer screen, or hand-held card. Visual acuity is routinely tested at distance (10 to 20 feet or 3 to 6 meters) and at near (14 to 16 inches or 35 to 40 centimeters). Visual acuity testing conditions should be standardized so that results obtained over a series of visits can be readily compared. High-contrast charts with black optotypes on a white background should be used for standard visual acuity testing.140, 206

A child’s performance on a visual acuity test will depend on the choice of chart and the examiner’s skills and rapport with the child, and on the child’s level of cooperation. To reduce errors, the environment should be quiet and free of distraction. Younger children may benefit from a pretest on optotypes presented at near, either at the start of testing or in a separate session. Before monocular testing, the examiner should ensure that the child is able to perform the test reliably. Allowing children to match optotypes on the chart to those found on a hand-held card will enhance performance, especially in young, shy, or children with cognitive impairments. Visual acuity testing of children with special needs can provide quantitative information about visual impairment and reduce concerns of parents/caregivers about the child’s vision.206 A shorter testing distance or flip chart can also facilitate testing in younger children.138

Visual acuity testing should be performed monocularly and with best refractive correction in place. Ideally, the fellow eye should be covered with an adhesive patch or tape. If such occlusion is not available or not tolerated by the child, care must be taken to prevent the child from peeking and using the “covered” eye. Sometimes the child will not allow any monocular occlusion, in which case binocular visual acuity should be measured. Monocular visual acuity testing for patients with nystagmus or latent nystagmus requires special techniques such as blurring the fellow eye with high plus lenses or using a translucent occluder rather than an opaque one. Binocular visual acuity testing can also be performed on these patients to gain additional information about typical visual performance.

An age-appropriate and consistent testing strategy on every examination is essential. The choice and arrangement of optotypes can significantly affect the visual acuity score obtained.207–209 Optotypes should be clear, standardized, and of similar characteristics, and they should not reflect a cultural bias.140 LEA SYMBOLS® (Good-Lite Co., Elgin, IL), a set of four symbols developed for use with young children, are useful because each optotype blurs similarly as the child is presented with smaller symbols, increasing the reliability of the test.10, 207 Another method for testing young children involves using a design containing only the letters H, O, T, and V.207, 210 Because the LEA SYMBOLS and the HOTV optotypes include only four possible responses, these acuity tests are easier for younger children. Children who cannot name the LEA SYMBOLS or HOTV letters may be able to match them using a hand-held card. For older children, Sloan letters are preferred.

Several other symbol charts, including Allen figures, the Lighthouse chart, and the Kindergarten (Sailboat) Eye Chart use optotypes that have not been validated and/or are not presented according to recommended standards for eye chart design.139, 140

The desirable optotypes for older children are Sloan letters used with logMAR size progression and proportional spacing of letters and lines, as in the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) tests.11 Snellen charts are less desirable because the chart design is not standardized, the individual letters are not of equal legibility and the spacing of the letters does not always meet World Health Organization standards.140–144

The arrangement of optotypes on a visual acuity test is important.139 Optotypes should be presented in a full line of five whenever possible. If a child needs assistance knowing which optotype to identify, the screener may point to the optotype and immediately remove the pointer. The majority of optotypes must be correctly identified to “pass” a line. A similar number of optotypes on each line with equal spacing is preferred. In the setting of amblyopia, visual acuity testing with single optotypes is likely to overestimate visual acuity211–213 because of the crowding phenomenon; that is, it is easier to discriminate an isolated optotype than one presented in a line of optotypes. Therefore, a more accurate assessment of monocular visual acuity is obtained in amblyopia with a line of optotypes. In order to preserve the crowding effect of adjacent optotypes, optotypes should not be covered or masked as the examiner points to each successive optotype. If a single optotype must be used to facilitate visual acuity testing for some children, the single optotype should be surrounded (crowded) by bars placed above, below, and on either side of the optotype to account for the crowding phenomenon and to avoid overestimating visual acuity.148, 214, 215 An age-appropriate and consistent testing strategy on every examination is needed.

Forced choice preferential looking testing can provide an assessment of grating resolution visual acuity in some infants and in preverbal children, and the patient’s acuity can be compared with normative data; this method of testing overestimates recognition visual acuity in children with amblyopia.216, 217

Appendix 2 shows the design details of visual acuity testing charts.

Binocular Alignment and Ocular Motility Assessment

The corneal light reflection, binocular red reflex (Brückner) test, and cover tests are commonly used to assess binocular alignment. Cover/uncover tests for tropias and alternate cover tests for the total deviation (latent component included) in primary gaze at distance and near should use accommodative targets. The cover test is performed by covering one eye and observing for a refixation movement of the fellow eye; if it occurs, then a tropia is present. Cover tests require sufficient visual acuity and cooperation to fixate on the desired target. Ocular versions and ductions, including into the oblique fields of gaze, should be tested in all infants and children. Eye movements may be tested using oculocephalic rotation (doll’s head maneuver) or assessed by observing spontaneous eye movements in the inattentive or uncooperative child. Binocular alignment testing should be done before cycloplegia, because alignment may change after cycloplegia.

Visual Field Testing

Confrontation visual field testing may be performed in children using a toy or by asking them to count fingers in each quadrant. The peripheral visual field of very young children can be assessed by observation for refixation to the field of gaze in which an object of interest has been presented. A young child may mimic or state aloud the number of fingers held in different quadrants of the visual field while looking at the examiner’s face. Older children may count the examiner’s fingers when presented in all quadrants of the visual field for each eye. Quantitative visual field testing should be attempted when indicated; reliability may be a concern, although performance may improve with practice.

Pupillary Examination

The pupils should be assessed for size, symmetry, and shape; for their direct and consensual responses to light; and for presence of a relative afferent defect. Pupillary evaluation in infants and children may be difficult due to hippus, poorly maintained fixation, and/or rapid changes in accommodative status. Anisocoria greater than 1 millimeter may indicate a pathological process, such as Horner syndrome, Adie tonic pupil, or a pupil-involving third-cranial-nerve palsy. Irregular pupils may indicate the presence of traumatic sphincter damage, iritis, or a congenital abnormality (e.g., coloboma). A relative afferent pupillary defect (RAPD) of 0.3 or more log units (i.e., easily visible) is not typically seen in amblyopia.218 A subtle RAPD may be seen with dense amblyopia. The presence of a large RAPD should warrant a search for compressive optic neuropathy or other etiologies of visual impairment (e.g., retinal abnormality).218

External Examination

The external examination involves assessment of the eyelids, eyelashes, lacrimal system, and orbit. The examination should include an assessment of ptosis, the amount of levator function, presence of eyelid retraction, and relative position of the globe within the orbit (e.g., proptosis or globe retraction, hypoglobus, or hyperglobus). Older children may tolerate measurement of globe position using an exophthalmometer. For uncooperative or younger children, proptosis of the globe may be estimated by comparing the position of the globes when viewing from above the head. The anatomy of the face (including the eyelids, interocular distance, and presence or absence of epicanthal folds), orbital rim, and presence of oculofacial anomalies should be noted. The position of the head and face (including head tilt, turn, or chin-up or chin-down head posture) should be recorded. Children who have prominent epicanthal folds and/or a wide, flat nasal bridge and normal binocular alignment often appear to have an esotropia (pseudoesotropia). Dysmorphic features need further evaluation.

Anterior Segment Examination

The cornea, conjunctiva, anterior chamber, iris, and lens should be evaluated using slit-lamp biomicroscopy, if possible. For infants and young children, anterior segment examination using a direct ophthalmoscope, a magnifying lens such as that used for indirect ophthalmoscopy, or a hand-held slit-lamp biomicroscope may be helpful.

Cycloplegic Refraction

Determination of refractive error is important in the diagnosis and treatment of amblyopia or strabismus. Patients should undergo cycloplegic refraction with retinoscopy, followed by subjective refinement of refraction when possible.195 Cycloplegic autorefraction has also been shown to be an accurate means of assessing the refractive error of children and can be used in conjunction with retinoscopy and subjective refinement.219 Care must be made to ensure that adequate time passes following installation of cycloplegia agents. Recommended cycloplegic agents are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Recommended Cycloplegic Agents

| Age | Recommended Agent | Dosage | Duration of Cycloplegia + Mydriasis | Side Effect Profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Preterm to 3 months | Cyclomydril (cyclopentolate 0.2% and phenylephrine 1%) | Two sets of one drop every 5 minutes | 6–48 hours+ | Minimal |

|

| ||||

| 3 months to 1 year | Cyclopentolate 0.5% | Two sets of one drop every 5 minutes | 6—48 hours+ | Moderate |

|

| ||||

| Cyclopentolate 1% |

Two sets of one drop every 5 minutes | 6–48 hours+ | Moderate | |

| 1 to 12 years | Atropine 1% drops or ointment | One drop twice a day for 3 days | 1–2 weeks+ | High |

|

| ||||

| 12 years and older | Tropicamide 1% (may be used for younger children if cyclopentolate unavailable) | Two sets of one drop every 5 minutes | 2–6+ hours | Low |

Source: Mutti DO, Zadnik K, Egashira S, et al. The Effect of Cycloplegia on Measurement of the Ocular Components. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1994; 35: 515–27. Taylor and Hoyt Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus 6th Edition.

Adequate cycloplegia is necessary for accurate retinoscopy in children because of their increased accommodative tone compared with adults. One study found that noncycloplegic refraction compared with cycloplegic refraction among school-aged children resulted in a measurement of 0.65 D more myopia on average.220 At present, there is no ideal cycloplegic agent that has rapid onset and recovery, provides sufficient cycloplegia, and has no local or systemic side effects.221 Cyclopentolate hydrochloride 1% is useful because it produces rapid cycloplegia that approximates the effect of topical ophthalmic atropine 1% solution but with a shorter duration of action.222 Cyclopentolate 1% solution is typically used in term infants over 12 months old. The dose of cyclopentolate should be determined based on the child’s weight, iris color, and dilation history. In eyes with heavily pigmented irides, repeating the cycloplegic eyedrops or using adjunctive agents, such as phenylephrine hydrochloride 2.5% (which has no cycloplegic effect) or tropicamide 1.0%, may be helpful to achieve adequate cycloplegia and dilation to facilitate retinoscopy and ophthalmoscopy.221 Tropicamide (0.5%) and phenylephrine hydrochloride (2.5%) may also be used in combination to produce adequate dilation and cycloplegia. For children younger than 6 months, an eyedrop combination of cyclopentolate 0.2% and phenylephrine 1% is often used.223 In some children, higher concentrations may be necessary.

In rare cases, topical ophthalmic atropine sulphate 1% solution may be necessary to achieve maximal cycloplegia.222 The use of topical anesthetic prior to the cycloplegic reduces the stinging of subsequent eyedrops and promotes penetration of subsequent eyedrops.224 Uncommon short-term side effects of cycloplegic agents may include hypersensitivity reactions, fever, dry mouth, tachycardia, nausea, vomiting, flushing, somnolence, and, rarely, behavioral changes (i.e., delirium). Punctal occlusion may be useful to reduce these side effects. If the reaction is severe, the child should be referred to an emergency care setting and physostigmine may be given.

Funduscopic Examination

The optic disc, macula, retina, vessels, and the choroid should be examined, preferably using an indirect ophthalmoscope and condensing lens after adequate dilation is achieved. It may be impossible to examine the peripheral retina of the awake young child. If necessary, examination of the peripheral retina with an eyelid speculum and scleral depression may require swaddling, sedation, or general anesthesia.

OTHER TESTS

Based on the patient’s history and findings, additional tests or evaluations that are not part of the routine comprehensive ophthalmic evaluation may be indicated. Components that may be included if the child cooperates are the sensorimotor evaluation, assessment of accommodation and convergence, color-vision testing, measurement of intraocular pressure (IOP), and imaging. Photography of facial or ocular structural abnormalities may be helpful for documentation and follow-up.

Sensorimotor Evaluation

A sensorimotor examination consists of measuring binocular alignment in more than one field of gaze with sensory testing of binocular function when appropriate, which includes testing of binocular sensory status (stereoacuity or Worth 4-Dot); assessing diplopia-free visual field; measuring ocular torsion (double Maddox rods); and/or assessing whether horizontal, vertical, and torsional components require correction in order to restore binocular alignment (using a prism or a synoptophore).

Assessment of Accommodation and Convergence

Testing the near point of accommodation and convergence and determining accommodative and fusional convergence amplitudes can be helpful in children with reading concerns. In a recent study, convergence insufficiency was reported to be present in 2% to 6% of 5th and 6th grade children and accommodative insufficiency in 10%.225 Noncycloplegic retinoscopy provides a rapid assessment of accommodation and may be helpful in evaluating a child with asthenopia who has high hyperopia or a child at risk for accommodative dysfunction, such cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, or other types of developmental delay.226–228,229 Accurate accommodation when viewing a small target on or near the retinoscope is seen as a neutral retinoscopic reflex or small degree of “with” movement. In dynamic retinoscopy, the examiner evaluates the change in the retinoscopic reflex from a “with” motion toward neutrality when the patient shifts fixation from distance to the near target.

Color-Vision Deficiency Testing

Color-vision deficiency testing is usually performed with pseudoisochromatic plates, and children who cannot yet identify numbers can instead identify simple objects.230 Eight percent of males and less than 1% of females are color deficient.231 Color-vision testing is not routinely performed in asymptomatic children but can be useful in symptomatic children or when there is a family history of color deficiency. When identified in a young child, it can be useful for their teachers to be aware that it may be difficult for them to accurately identify certain colors.

Intraocular Pressure Measurement

Intraocular pressure measurement is not necessary for every child because glaucoma is rare in this age group and, when present, usually has additional manifestations (e.g., buphthalmos, epiphora, photosensitivity, and corneal clouding in infants; myopic progression in very young children; and enlarged optic cups). Intraocular pressure should be measured whenever a child has or is at risk for glaucoma. Because IOP measurement can be difficult in some children, a separate examination with the patient sedated or anesthetized may be required. The introduction of more compact instruments such as the Tono-Pen (Reichert, Inc., Depew, NY), Perkins tonometer (Haag-Streit UK Ltd., Harlow, United Kingdom), and iCare rebound tonometer (iCare Finland Oy, Helsinki, Finland) have facilitated testing of IOP in children.232, 233 One advantage of the iCare rebound tonometer is that topical anesthetic drops are not required; however, overestimation of IOP sometimes occurs.234 Central corneal thickness measurement may be helpful in interpreting IOP because thicker corneas may cause artificially high IOP readings and thinner corneas can produce artificially low IOP readings.235–238

Imaging

Photography or imaging in conjunction with the comprehensive pediatric eye examination may be appropriate to document and follow changes of facial or ocular structural abnormalities. Examples of indications to image include external photography for orbital or adnexal masses, strabismus, ptosis, or facial structure abnormalities; photography and optical coherence tomography to document cataract and other anterior segment anomalies; corneal topography to detect early changes related to keratoconus; ultrasound for vitreous and/or retinal pathology; and autofluorescence for optic nerve head assessment. Optical coherence tomography of the retinal nerve fiber layer/ganglion cell layer and of the retina may be considered in young children for conditions such as unexplained visual loss, risk of ocular toxicity from mediciation, glaucoma suspect, optic neuropathy, retinal dystrophies, and ROP.

DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

When the eye examination is normal or indicates only a refractive error, and the child does not have risk factors for the development of eye disease, the ophthalmologist should establish an appropriate interval for re-examination. If re-examination has been determined to be unnecessary, patients should return for a comprehensive eye evaluation if new ocular symptoms, signs, or risk factors for ocular disease develop. Periodic vision screening should be continued (see Table 2).

When the history reveals risk factors for developing ocular disease or the examination shows potential signs of an abnormal condition, the ophthalmologist should determine an appropriate treatment and management plan for each child based on the findings and the age of the child. Periodic vision screening may be discontinued if the child is routinely followed with comprehensive eye evaluations (see Table 2).

When ocular disease is present, a treatment and management plan should be established, which may involve observation, eyeglasses, topical or systemic medications, occlusion therapy, eye exercises, and/or surgical procedures. The ophthalmologist should communicate the examination findings and the need for further evaluation, testing, treatment, or follow-up to parents/caregivers and to the patient and the patient’s primary care physician or other specialists, as appropriate. Further evaluation or referral to other medical specialists may be advised.

Management of amblyopia, esotropia, and exotropia are discussed in the Amblyopia PPP55 and the Esotropia and Exotropia PPP,50 respectively.

Refractive correction is prescribed for children to improve visual acuity, alignment, and binocularity and to reduce asthenopia. Refractive correction plays an important role in the treatment of amblyopia and strabismus (see Amblyopia PPP55 and Esotropia and Exotropia PPP50). Table 2 provides guidelines for refractive correction in infants and young children. Smaller amounts of refractive error may also warrant correction depending on the clinical situation.

Factors that help children to wear eyeglasses successfully include a correct prescription, frames that fit well, and positive reinforcement. Children require updates in eyeglasses much more frequently than adults owing to eye growth and associated changes in refraction.

Infants and children with cerebral visual impairment or Down syndrome, and children on prescribed seizure medication may have poor accommodation and, therefore, require correction for smaller amounts of hyperopia compared with typically developing infants and toddlers.

PROVIDER AND SETTING

Certain eye care services and procedures, including elements of the eye examination, may be delegated to appropriately trained and supervised auxiliary health care personnel under the ophthalmologist’s supervision.239 For cases in which the diagnosis or management is difficult, consultation with or referral to an ophthalmologist who specializes in the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric patients may be desirable.

Of all vision care providers, the ophthalmologist, as a physician with full medical training, best combines a thorough understanding of ocular pathology and disease processes; familiarity with systemic disorders that have ocular manifestations; and clinical skills and experience in ocular diagnosis, treatment, and medical decision-making. This makes the ophthalmologist the most qualified professional to perform, oversee, and interpret the results of a comprehensive medical eye evaluation. Frequently, and appropriately, specific testing and data collection are conducted by trained personnel working under the ophthalmologist’s supervision.

COUNSELING AND REFERRAL

The ophthalmologist should discuss the findings and any need for further evaluation, testing, or treatment with the child and/or family/caregiver. When a hereditary eye disease is identified, the parent/caregiver may be advised to have other family members evaluated and counseled for risk to subsequent pregnancies, which may include referral to a geneticist or genetic counselor.240 Families with financial hardship or who have a child who has a new diagnosis of a sight- or life-threatening condition may benefit from referral to social services. Patients with bilateral visual impairment should be offered contact information for early intervention and/or vision rehabilitation services.193 Many ocular/neurological diagnoses qualify newborns and children up to 3 years old for free early intervention services under Part C of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (http://idea.ed.gov).

APPENDIX 1. QUALITY OF OPHTHALMIC CARE CORE CRITERIA

Providing quality care is the physician’s foremost ethical obligation, and is the basis of public trust in physicians.

AMA Board of Trustees, 1986

Quality ophthalmic care is provided in a manner and with the skill that is consistent with the best interests of the patient. The discussion that follows characterizes the core elements of such care.

The ophthalmologist is first and foremost a physician. As such, the ophthalmologist demonstrates compassion and concern for the individual, and utilizes the science and art of medicine to help alleviate patient fear and suffering. The ophthalmologist strives to develop and maintain clinical skills at the highest feasible level, consistent with the needs of patients, through training and continuing education. The ophthalmologist evaluates those skills and medical knowledge in relation to the needs of the patient and responds accordingly. The ophthalmologist also ensures that needy patients receive necessary care directly or through referral to appropriate persons and facilities that will provide such care, and he or she supports activities that promote health and prevent disease and disability.

The ophthalmologist recognizes that disease places patients in a disadvantaged, dependent state. The ophthalmologist respects the dignity and integrity of his or her patients and does not exploit their vulnerability.

Quality ophthalmic care has the following optimal attributes, among others.

The essence of quality care is a meaningful partnership relationship between patient and physician. The ophthalmologist strives to communicate effectively with his or her patients, listening carefully to their needs and concerns. In turn, the ophthalmologist educates his or her patients about the nature and prognosis of their condition and about proper and appropriate therapeutic modalities. This is to ensure their meaningful participation (appropriate to their unique physical, intellectual, and emotional state) in decisions affecting their management and care, to improve their motivation and compliance with the agreed plan of treatment, and to help alleviate their fears and concerns.

The ophthalmologist uses his or her best judgment in choosing and timing appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic modalities as well as the frequency of evaluation and follow-up, with due regard to the urgency and nature of the patient’s condition and unique needs and desires.

The ophthalmologist carries out only those procedures for which he or she is adequately trained, experienced, and competent, or, when necessary, is assisted by someone who is, depending on the urgency of the problem and availability and accessibility of alternative providers.

- Patients are assured access to, and continuity of, needed and appropriate ophthalmic care, which can be described as follows.

- The ophthalmologist treats patients with due regard to timeliness, appropriateness, and his or her own ability to provide such care.

- The operating ophthalmologist makes adequate provision for appropriate pre- and postoperative patient care.

- When the ophthalmologist is unavailable for his or her patient, he or she provides appropriate alternative ophthalmic care, with adequate mechanisms for informing patients of the existence of such care and procedures for obtaining it.

- The ophthalmologist refers patients to other ophthalmologists and eye care providers based on the timeliness and appropriateness of such referral, the patient’s needs, the competence and qualifications of the person to whom the referral is made, and access and availability.