Abstract

Our objective was to estimate disparities in binge drinking among secondary school students in California at the intersection of gender identity, race, and ethnicity, without aggregating racial and ethnic categories. We combined two years of the Statewide middle and high school California Healthy Kids Survey (n=951,995) and regressed past month binge drinking on gender identity (i.e., cisgender, transgender, or not sure of their gender identity), race (i.e., white, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, or multiracial), and ethnicity (i.e., Hispanic/Latinx or non-Hispanic/Latinx), and their interaction. Transgender students had greater odds of reporting past month binge drinking than cisgender students, with greater magnitudes among students with minoritized racial or ethnic identities compared to non-Hispanic/Latinx white students. For example, among non-Hispanic/Latinx white students, transgender students had 1.3 times greater odds (AOR=1.30, 95% CI=1.17—1.55), whereas among Hispanic/Latinx Black or African American students, transgender students had 5.3 times greater odds (AOR=5.33, 95% CI=3.84—7.39) of reporting past month binge drinking than cisgender students. Transgender adolescents, particularly those with minoritized racial or ethnic identities, may be at disproportionate risk of binge drinking. Interventions that address systemic racism and cisgenderism from an intersectional perspective are needed.

Keywords: gender identity, transgender, race, ethnicity, alcohol use, binge drinking, health disparities, adolescents

As many as 29% of all high school students reported current (i.e., past month) alcohol use in 2019 (Jones et al., 2020). Alcohol use in adolescence is associated with numerous health concerns including sexual risk behaviors, motor vehicle accidents, violence, other substance use, and alcohol use disorders (Chung, Creswell, Bachrach, Clark, & Martin, 2018; Clark Goings et al., 2019), as well as poor academic achievement and absenteeism (An, Loes, & Trolian, 2017; Maynard et al., 2017; Patte, Qian, & Leatherdale, 2017). Further, problematic alcohol use behaviors, such as binge drinking (i.e., consuming enough alcohol to raise the blood alcohol concentration to 0.08 g/dL), can increase these risks and can cause acute alcohol poisoning (Chung et al., 2018). Binge drinking in the US declined from 2002 to 2016 among all adolescent subgroups by race/ethnicity, sex/gender, and age (Clark Goings et al., 2019). Similar trends have been reported from 2009 to 2019 among US high school students overall, yet 13% reported current binge drinking in 2019 (Jones et al., 2020). These findings indicate an ongoing need for research and prevention efforts to address binge drinking and other associated harmful alcohol use behaviors among adolescents in the US.

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework developed by critical race and Black feminist scholars that can be used to investigate health disparities at the intersections of multiple social positions such as race, sex/gender, class, and others (Bowleg, 2012; Crenshaw, 1989). Intersectionality recognizes the pervasive existence of multiple interlocking systems of privilege and oppression that shape opportunities, experiences, and access to resources and maintain health disparities across social positions (Bowleg, 2012). Two such systems that are relevant for framing and interpreting this investigation are cisgenderism and racism.

Cisgenderism refers to the pervasive system which oppresses transgender people (i.e., whose gender identity does not align with their sex assignment at birth), while simultaneously privileging cisgender people (i.e., whose gender identity aligns with their sex assignment at birth) (Lennon & Mistler, 2014). The Gender Minority Stress Model posits experiences of chronic stressors related to gender identity increase psychological distress and substance use behaviors among transgender adults (Hendricks & Testa, 2012). Although the Gender Minority Stress Model was developed to explain disparities in substance use among transgender adults, a recent review suggests it is useful in describing the relationships between minority stressors, resilience factors, and substance use disparities among transgender adolescents (Delozier, Kamody, Rodgers, & Chen, 2020). Indeed, research suggests transgender adolescents are more likely to report binge drinking and other substance use than their cisgender peers (Day, Fish, Perez-Brumer, Hatzenbuehler, & Russell, 2017; Eisenberg et al., 2017; Gilbert, Pass, Keuroghlian, Greenfield, & Reisner, 2018). These findings indicate a need for ongoing alcohol use prevention efforts among transgender adolescents broadly, however, they do not provide information about disparities among racial or ethnic subgroups of transgender adolescents.

Historically, transgender adolescents have been minoritized and face discrimination in social contexts including schools(Kosciw, Clark, Truong, & Zongrone, 2020; Truong, Zongrone, & Kosciw, 2020). Although recent policy changes in states such as California have attempted to address these inequities, critical trans scholars have noted the failure of policies of inclusion (e.g., enumeration of gender identity in nondiscrimination policies) to dismantle the administrative systems of oppression (Meyer & Keenan, 2018; Spade, 2015). These policies also fail to critically examine how white supremacy interacts with cisgenderism, potentially leading to greater disparities among the most minoritized members of the trans communities, such as transgender adolescents of minoritized racial and/or ethnic identities and immigrants (Meyer & Keenan, 2018). Additionally, these policies have not been implemented equally across districts in California, with only San Francisco Unified School District meeting all the criterial of California state law (Meyer & Keenan, 2018).

In general, adolescents with minoritized racial or ethnic identities report binge drinking less frequently than non-Hispanic/Latinx white adolescents. For example, non-Hispanic/Latinx white adolescents were more likely to report past month binge drinking (17%) than Hispanic/Latinx adolescents (12%) and non-Hispanic/Latinx Black or African American adolescents (6%), in 2019 (Jones et al., 2020). Further, Asian and multiracial adolescents had a lower prevalence of past month binge drinking than non-Hispanic/Latinx white adolescents (Subica & Wu, 2018). In contrast, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander and American Indian or Alaskan Native adolescents did not differ from non-Hispanic/Latinx white adolescents in their prevalence of past month binge drinking (Subica & Wu, 2018). Less is known about adolescent binge drinking behaviors at the intersection of gender identity, race, and ethnicity.

Health disparities research focused on the needs and experiences of transgender adolescents with minoritized racial or ethnic identities is limited and has primarily employed qualitative methods to highlight the unique experiences of living with multiple minoritized statuses (Singh, 2013). Researchers have called from intersectional health disparities research that investigates racial and ethnic disparities among gender minorities (Mereish, 2018; Tan, Treharne, Ellis, Schmidt, & Veale, 2019). Further, quantitative health disparities research often aggregates transgender youth of color into a single category, thereby masking potential heterogeneity based on race or ethnicity (Hatchel & Marx, 2018). Statistical considerations pose numerous challenges to quantifying health disparities at the intersection of multiple minoritized identities, including obtaining large enough samples for precise estimates (Bauer et al., 2021). Due to limited samples sizes, race and ethnicity are often categorized as white, Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and “other” thereby conflating the concepts of race and ethnicity and erasing the experience of indigenous and other smaller racial groups because of a lack of statistical power (Ford & Harawa, 2010; Lett, Asabor, Beltrán, Michelle Cannon, & Arah, 2022). Ethnicity has been defined as “a context-specific, multilevel (i.e., group-level, individual-level), multifactorial social construct that is tied to race and used both to distinguish diverse populations and to establish personal or group identity” (Ford & Harawa, 2010, p. 252). Race in the US has been defined as “a social construct linked to phenotype and/or ancestry that indexes one’s location on the US social hierarchy of socially-constructed, groupings (i.e., races) that has been based primarily on skin color (i.e., white, black, red, yellow) and used for more than 200 years in the US” (Ford & Harawa, 2010, p. 253). Thus, adolescents who are Hispanic/Latinx may differ in terms of race (Fergus, 2016), and although Hispanic/Latinx people may have a shared cultural identity regardless of race, darker skinned Hispanic/Latinx adolescents may experience more discrimination than those who are white, potentially leading to more severe health disparities, including drinking-related outcomes (Flores-González, Aranda, & Vaquera, 2014). More fine-grained information on how adolescent binge drinking disparities vary at the intersections of gender identity, race, and ethnicity can lead to more effective tailoring of prevention efforts to advance health equity.

The purpose of this study is to assess disparities in binge drinking among middle and high school students in California at the intersection of gender identity, race, and ethnicity. We hypothesize the relationship between gender identity and binge drinking will vary by race and ethnicity, such that the magnitude of disparities between transgender and cisgender students will be greater for students with minoritized racial or ethnic identities than non-Hispanic/Latinx, white students. Further, among cisgender students, we hypothesize that students with minoritized racial or ethnic identities will report less binge drinking than non-Hispanic/Latinx, white students, whereas among transgender students we hypothesize students with minoritized racial or ethnic identities will report more binge drinking than non-Hispanic/Latinx, white students.

Methods

Data for this analysis come from the 2017–18 and 2018–19 Statewide California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS), an annual cross-sectional survey of school climate, social-emotional and physical health, and health behaviors, including substance use, among middle school and high school students in California. Data were collected in classrooms with students predominately in grades 7, 9, and 11. Students self-reported all items.

Passive parental consent was used for grades 7 and above, such that parents were notified and required to return a form to the school only if they did not approve of participation. Active consent procedures were used for grades 6 and below. Students participate voluntarily and anonymously (WestEd for the California Department of Education, 2021). Surveys were administered in English and Spanish via an electronic or paper and pen/pencil version. The San Diego State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) deemed the analysis of publicly available, de-identified data exempt from IRB review.

Measures

Past month binge drinking, was assessed with the question “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you use five or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is, within a couple hours?” with response options 0 days, 1 day, 2 days, 3–9 days, 10–19 days, 20–30 days. For this analysis, we recoded responses as 0 days (no binge drinking) and 1 or more days (any binge drinking), given that any binge drinking can have negative health implications for adolescents.

Similar to other school-based health surveillance (Michelle M Johns et al., 2019), gender identity was assessed with the following question, “Some people describe themselves as transgender when their sex at birth does not match the way they think or feel about their gender. Are you transgender?” with response options (1) no, I am not transgender, (2) yes, I am transgender, (3) I am not sure if I am transgender, and (4) decline to respond. Students who selected declined to respond were excluded from this analysis. Students were considered cisgender if they selected “no, I am not transgender,” transgender if they select “yes, I am transgender,” and “not sure” if they selected, “I am not sure if I am transgender.”

Students were asked about their race and their ethnicity with two separate items. For race, students were asked, “What is your race?” with response options (1) American Indian or Alaskan Native, (2) Asian, (3) Black or African American, (4) Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, (5) white, or (6) mixed (two or more) races. For ethnicity, students were asked, “Are you of Hispanic or Latino origin?” with response options yes and no. Some students marked yes to the question about ethnicity and did not select a race, while others marked yes or no to the ethnicity question and then selected one of the 6 race categories. In order to model race and ethnicity without aggregating groups, we recoded race and ethnicity into 13 mutually exclusive categories: non-Hispanic/Latinx white, non-Hispanic/Latinx American Indian or Alaskan Native, non-Hispanic/Latinx Asian, non-Hispanic/Latinx Black or African American, non-Hispanic/Latinx Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, non-Hispanic/Latinx multiracial, Hispanic/Latinx no race selected, Hispanic/Latinx white, Hispanic/Latinx American Indian or Alaskan Native, Hispanic/Latinx Asian, Hispanic/Latinx Black or African American, Hispanic/Latinx Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and Hispanic/Latinx multiracial. Although we consider race and ethnicity to be distinct constructs, we combined race and ethnicity into one variable for the purposes of statistical modeling, which allowed us to retain the large number of Hispanic/Latinx students who did not respond to the race question. Those students who selected one of the 6 race categories and did not answer the question about ethnicity were coded as non-Hispanic/Latinx and their racial category. We chose not to create additional racial and ethnic categories for example, “ethnicity question not answered, Asian,” as there were relatively fewer students who responded in this way compared to the number of Hispanic/Latinx students who did not answer the race question.

We included grade as a covariate, as alcohol use tends to increase with age (Clark Goings et al., 2019). We chose to use grade instead of age as is common in school based health research (Jones et al., 2020), and to align with the data collection. For grade, the majority of students participating in the CHKS are in grades 7th, 9th, and 11th; however a small proportion of students participating in the 2017–18 or 2018–19 survey were in 6th, 8th, 10th, or 12th grade. This was likely because they completed the survey during a class that is primarily open to students in grades 7th, 9th, or 11th, or that their school administered the survey to all grades. Thus, students were coded as being in 6th-8th, 9th-10th, 11th-12th, and “non-traditional” grades, as there were relatively fewer students in grades 6, 8, 10, and 12 compared to grades 7, 9, and 11. Non-traditional grades represent students enrolled in community day schools, or continuing education programs. We include parents’ education as a proxy for socioeconomic status, which has been associated with alcohol use and other risk behaviors among adolescents (Lowry, Kann, Collins, & Kolbe, 1996; Tucker, Pollard, de la Haye, Kennedy, & Green Jr, 2013). Parents’ education was assessed with the question, “What is the highest level of education your parents or guardians completed? (Mark the education level for the parent or guardian who went the furthest in school.)” with response options modeled as: did not finish high school, graduated from high school, attended college but did not complete four-year degree, graduated from college, and don’t know. Finally, we include sexual orientation in our analyses as lesbian, gay, bisexual and other sexual minority youth are more likely to use alcohol, including binge drinking, than heterosexual youth (Corliss, Rosario, Wypij, Fisher, & Austin, 2008; Fish & Baams, 2018; Marshal et al., 2008). Sexual orientation was captured with the question, “Which of the following best describes you?” with response options modeled as: straight (not gay), gay or lesbian, bisexual, I am not sure yet, something else or decline to respond.

Analytic sample

After aggregating samples from 2017–2018 and 2018–2019, the total sample was 1,172,377 students in 2,910 schools. We first excluded students with missing data for school (n=329, 0.03% of students). Then, we excluded 154 schools (5.3% of schools) that did not ask about substance use and 38 schools (1.3%) that did not ask about gender identity, leaving 1,118,439 students in eligible schools. Next, we excluded students who declined to respond to the gender identity question (3.1% of students) and students with missing data for the gender identity question (8.8%). We then excluded students whose response raised concerns of validity per the survey administrator’s (i.e., WestEd) recommendation (0.84%) (e.g., students who indicated the use of a fictitious substance included in the survey). Finally, we excluded students with missing data for race and ethnicity (0.60%), binge drinking (0.55%), and our covariates grade, parents’ education, and sexual orientation (1.02%), leaving us with an analytic sample of 951,995 students (85.1% of students in eligible schools) in 2,718 schools (93.4% of schools).

Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS statistical software version 9.4. We calculated the unadjusted proportion of students who binge drank in the past month by gender identity and race and ethnicity. We then assessed the bivariate relationship between binge drinking and all student level variables using Chi-Square goodness of fit tests. We also tested for collinearity between gender identity and sexual orientation by examining the Phi Coefficient. Using the PROC GLIMMIX command to account for clustering by schools, we regressed past month binge drinking on gender identity and race and ethnicity, and their interaction, adjusting for grade, parents’ education, and sexual orientation. We used post model fit hypothesis tests to calculate adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for gender identity by race and ethnicity and for race and ethnicity by gender identity as is recommended to describe an intersectional interaction (Knol & VanderWeele, 2012). We chose this approach to estimation rather than stratification to retain the power of our full sample. The significance level was set at a p-value less than 0.05. As a sensitivity analysis, we ran our model without adjusting for sexual orientation.

Results

Most students (97.4%) were cisgender, 0.9% were transgender, and 1.7% were not sure if they were transgender. About half (51.5%) of students were Hispanic/Latinx. Among non-Hispanic/Latinx students, 45.0% were white, 2.0% were American Indian or Alaskan Native, 22.5% were Asian, 7.0% were Black or African American, 2.5% were native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 21.0% were multiracial. Among Hispanic/Latinx students, 15.5% did not selected a race, 14.6% were white, 5.4% were American Indian or Alaskan Native, 0.8% were Asian, 1.3% Black or African American, .6% were Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and 61.8% were multiracial. Table 1 provides additional demographics as well as the proportion of students who reported past month binge drinking by each demographic category. Chi-Square tests indicated all independent categorical variables were significantly associated with past month binge drinking (data not shown). Gender identity and sexual orientation were moderately correlated (Phi Coefficient = 0.35).

Table 1.

Student characteristics by past month binge drank, California Healthy Kids Statewide Survey, 2017–18 and 2018–19 (n = 951,995)

| Past month binge drinking | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total, N (%)a | Yes, N (%)b 45,801 (4.8) |

No, N (%)b 906,194 (95.2) |

|

| Gender identity | |||

| Cisgender | 926,795 (97.3) | 43,444 (4.7) | 883,351 (95.3) |

| Transgender | 8,703 (0.9) | 1,232 (14.2) | 7,471 (85.8) |

| Not sure | 16,497 (1.7) | 1,125 (6.8) | 15,372 (93.2) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic or Latinx | |||

| White | 207,756 (21.8) | 13,456 (6.5) | 194,300 (93.5) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 9,353 (1.0) | 567 (6.1) | 8,786 (93.9) |

| Asian | 104,004 (10.9) | 1,690 (1.6) | 102,314 (98.4) |

| Black or African American | 32,477 (3.4) | 980 (3.0) | 3,1497 (97.0) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 11,547 (1.2) | 517 (4.5) | 11,030 (95.5) |

| Multiracial | 97,050 (10.2) | 4,093 (4.2) | 92,957 (95.8) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | |||

| No race selected | 75,976 (8) | 3,851 (5.1) | 72,125 (94.9) |

| White | 71,542 (7.5) | 3,705 (5.2) | 67,837 (94.8) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 26,363 (2.8) | 1,273 (4.8) | 25,090 (95.2) |

| Asian | 3,811 (0.4) | 218 (5.7) | 3,593 (94.3) |

| Black or African American | 6,541 (0.7) | 479 (7.3) | 6,062 (92.7) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 3,062 (0.3) | 226 (7.4) | 2,836 (92.6) |

| Multiracial | 302,513 (31.8) | 14,746 (4.9) | 287,767 (95.1) |

| Grade | |||

| 6–8th grade | 334,924 (35.2) | 4,379 (1.3) | 330,545 (98.7) |

| 9–10th grade | 322,150 (33.8) | 13,159 (4.1) | 308,991 (95.9) |

| 11–12th grade | 270,943 (28.5) | 23,731 (8.8) | 247,212 (91.2) |

| Nontraditional | 23,978 (2.5) | 4,532 (18.9) | 19,446 (81.1) |

| Parents education | |||

| Did not finish high school | 125,447 (13.2) | 8,887 (7.1) | 116,560 (92.9) |

| Graduated high school | 150,120 (15.8) | 8,448 (5.6) | 141,672 (94.4) |

| Some college | 120,211 (12.6) | 6,940 (5.8) | 113,271 (94.2) |

| College graduate | 383,440 (40.3) | 16,851 (4.4) | 366,589 (95.6) |

| Don’t know | 172,777 (18.1) | 4,675 (2.7) | 168,102 (97.3) |

| Sexual orientation | |||

| Heterosexual | 799,874 (84) | 36,345 (4.5) | 763,529 (95.5) |

| Gay or lesbian | 14,802 (1.6) | 1,413 (9.6) | 13,389 (90.5) |

| Bisexual | 52,254 (5.5) | 4,729 (9.1) | 47,525 (91) |

| Not sure | 43,372 (4.6) | 1,749 (4) | 41,623 (96) |

| Other | 14,048 (1.5) | 878 (6.3) | 13,170 (93.8) |

| Decline | 27,645 (2.9) | 687 (2.5) | 26,958 (97.5) |

| Survey year | |||

| 2017–18 | 518,069 (54.4) | 25,735 (5.0) | 492,334 (95.0) |

| 2018–19 | 433,926 (45.6) | 20,066 (4.6) | 413,860 (95.4) |

Past month binge drinking = reported drinking 5 or more drinks in a row in at least once in the past month.

Column percentage.

Row percentage.

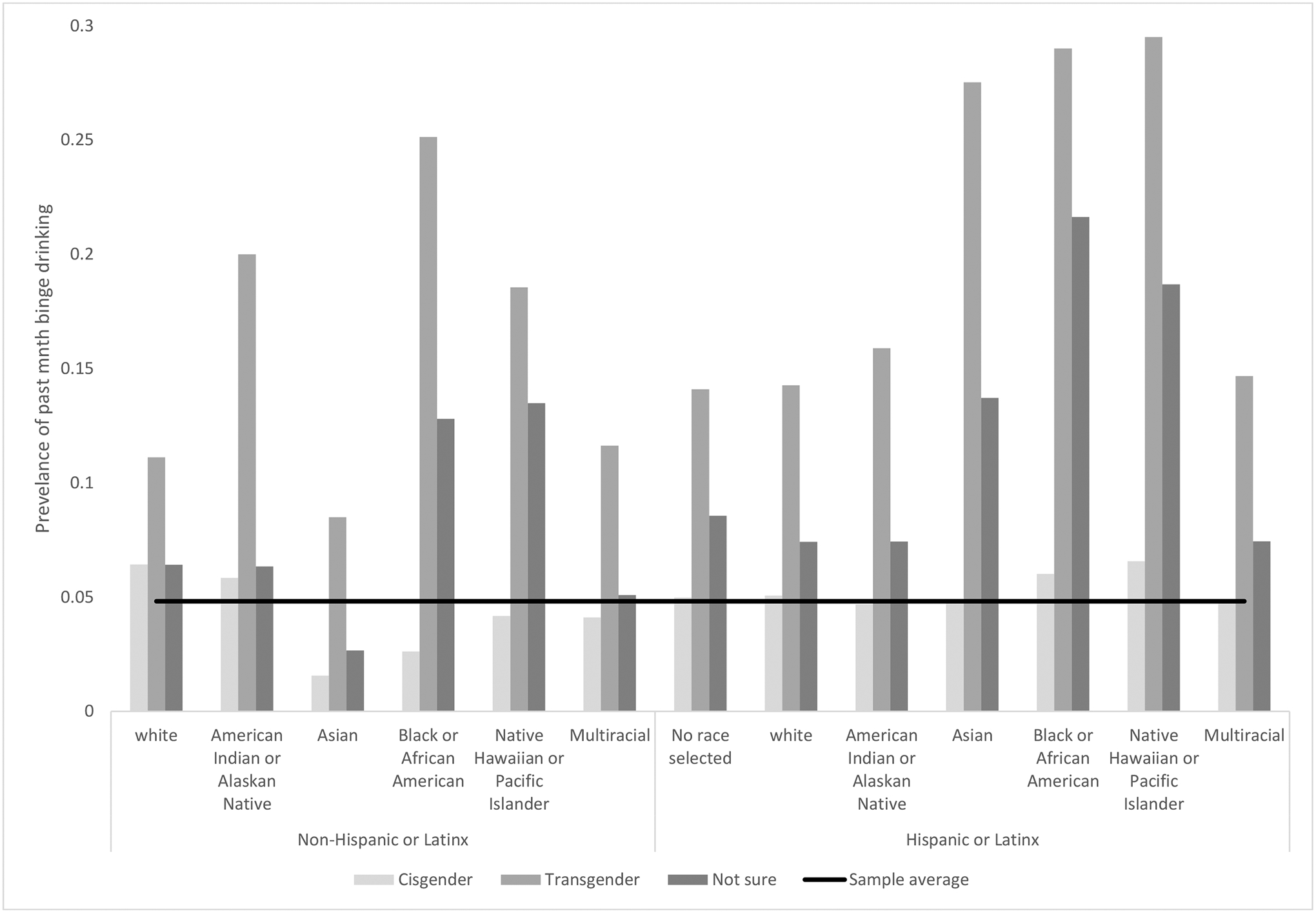

The prevalence of binge drinking in our sample was 4.8%. For gender, 4.7% of cisgender students, 14.2% of transgender students, and 6.8% of not sure students reported past month binge drinking. Figure 1 displays the unadjusted prevalence of past month binge drinking at the intersection of gender identity, race and ethnicity. Table 2 reports the frequencies and proportions of past month binge drinking at the intersection of gender identity, race and ethnicity. In each racial and ethnic category, transgender students reported the highest prevalence of past month binge drinking, followed by not sure students, and finally cisgender students with one exception. For non-Hispanic/Latinx white students, cisgender students and not sure students had approximately the same unadjusted prevalence of past month binge drinking.

Figure 1.

Unadjusted prevalence of past month binge drinking by gender identity, race and ethnicity, California Healthy Kids Statewide Survey, 2017–18 and 2018–19

Table 2.

Proportion of students who reported past month binge drinking at the intersection of gender identity, race, and ethnicity, California Healthy Kids Statewide Survey, 2017–18 and 2018–19

| Cisgender | Transgender | Not sure | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic or Latinx | |||

| White, n (%) | 12,987 (6.4) | 249 (11.1) | 220 (6.4) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native, n (%) | 522 (5.8) | 28 (20.0) | 17 (6.3) |

| Asian, n (%) | 1,582 (1.6) | 49 (8.5) | 59 (2.7) |

| Black or African American, n (%) | 827 (2.6) | 90 (25.1) | 63 (12.8) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, n (%) | 470 (4.2) | 23 (18.6) | 24 (13.5) |

| Multiracial, n (%) | 3,853 (4.1) | 127 (11.6) | 113 (5.1) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | |||

| No race selected, n (%) | 3,724 (5.0) | 54 (14.1) | 73 (8.6) |

| White, n (%) | 3,537 (5.1) | 89 (14.3) | 79 (7.4) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native, n (%) | 1,204 (4.7) | 34 (15.9) | 35 (7.4) |

| Asian, n (%) | 171 (4.8) | 30 (27.5) | 17 (13.7) |

| Black or African American, n (%) | 367 (6.0) | 67 (29.0) | 45 (21.6) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, n (%) | 191 (6.6) | 18 (29.5) | 17 (18.7) |

| Multiracial, n (%) | 14,009 (4.7) | 374 (14.7) | 363 (7.4) |

Past month binge drinking = reported drinking 5 or more drinks in a row in at least once in the past month.

In our adjusted model, gender identity by race and ethnicity interaction terms were statistically significant indicating the relationship between gender identity and binge drinking differs by race and ethnicity and vice versa (F=16.9, DFnumerator=24, DFdenominator>949,000, p<.0001). Table 3 displays the AORs and 95% confidence intervals, first within racial and ethnic with cisgender as the reference category and second within gender identity with non-Hispanic/Latinx white as the reference category. Our sensitivity analysis running our models without adjusting for sexual orientation revealed model estimates and significance of post model fit hypothesis tests were comparable to our fully adjusted model.

Table 3.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of past month binge drinking for gender identity by race and ethnicity and for race and ethnicity by gender identity, California Healthy Kids Statewide Survey, 2017–18 and 2018–19

| Cisgender N = 926,795 |

Transgender N = 8,703 |

Not sure N = 16,497 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic or Latinx | |||

| White | Reference | 1.35 (1.17, 1.55) | 1.02 (0.88, 1.18) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | Reference | 3.70 (2.34, 5.85) | 1.28 (0.76, 2.15) |

| Asian | Reference | 4.53 (3.32, 6.17) | 2.08 (1.59, 2.73) |

| Black or African American | Reference | 10.5 (7.95, 13.7) | 5.84 (4.36, 7.82) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | Reference | 4.08 (2.48, 6.71) | 3.79 (2.36, 6.07) |

| Multiracial | Reference | 2.20 (1.80, 2.68) | 1.31 (1.07, 1.60) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | |||

| No race selected | Reference | 2.51 (1.85, 3.40) | 1.95 (1.51, 2.51) |

| White | Reference | 2.84 (2.24, 3.62) | 1.72 (1.35, 2.19) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | Reference | 3.50 (2.36, 5.20) | 1.70 (1.18, 2.46) |

| Asian | Reference | 6.57 (4.06, 10.6) | 3.19 (1.81, 5.63) |

| Black or African American | Reference | 5.33 (3.84, 7.39) | 4.62 (3.17, 6.75) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | Reference | 5.02 (2.74, 9.18) | 3.99 (2.20, 7.24) |

| Multiracial | Reference | 2.64 (2.34, 2.98) | 1.71 (1.52, 1.92) |

| Non-Hispanic or Latinx | |||

| White | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 1.14 (1.03, 1.25) | 3.12 (1.95, 4.99) | 1.42 (0.83, 2.41) |

| Asian | 0.32 (0.31, 0.34) | 1.09 (0.78, 1.52) | 0.66 (0.49, 0.89) |

| Black or African American | 0.45 (0.41, 0.48) | 3.46 (2.57, 4.66) | 2.55 (1.85, 3.49) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0.77 (0.70, 0.85) | 2.35 (1.42, 3.90) | 2.87 (1.77, 4.65) |

| Multiracial | 0.84 (0.81, 0.87) | 1.37 (1.08, 1.74) | 1.08 (0.84, 1.37) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | |||

| No race selected | 0.76 (0.73, 0.79) | 1.41 (1.01, 1.97) | 1.44 (1.08, 1.93) |

| White | 0.76 (0.73, 0.80) | 1.61 (1.23, 2.12) | 1.28 (0.97, 1.69) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 0.85 (0.79, 0.90) | 2.20 (1.45, 3.33) | 1.41 (0.96, 2.08) |

| Asian | 0.91 (0.77, 1.06) | 4.43 (2.75, 7.12) | 2.83 (1.61, 4.97) |

| Black or African American | 1.15 (1.03, 1.29) | 4.55 (3.25, 6.37) | 5.19 (3.52, 7.66) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 1.09 (0.93, 1.27) | 4.05 (2.22, 7.39) | 4.25 (2.35, 7.68) |

| Multiracial | 0.94 (0.91, 0.97) | 1.85 (1.54, 2.22) | 1.57 (1.31, 1.89) |

Past month binge drinking = reported drinking 5 or more drinks in a row in at least once in the past month. Model was adjusted for grade, parents’ education, and sexual orientation.

Within each racial and ethnic group, transgender students were more likely to report past month binge drinking than cisgender students, albeit with different magnitudes. For example, among non-Hispanic/Latinx white students, transgender students had about 30% greater odds of reporting past month binge drinking than cisgender students (AOR=1.30, 95% CI=1.17—1.55). Yet, among non-Hispanic/Latinx Black or African American students, transgender students had approximately 10 times greater odds of reporting past month binge drinking than cisgender students (AOR=10.5, 95% CI=7.95—13.7). Across racial/ethnic groups, the magnitudes of difference between transgender and cisgender students were greater among all other racial and ethnic groups than non-Hispanic/Latinx white students. Supporting this observation is the fact that the lower bound confidence intervals for all students with minoritized racial or ethnic identities (lower confidence limit for non-Hispanic/Latinx Multiracial students=1.80) was higher than the upper bound confidence interval for non-Hispanic/Latinx white students (upper confidence limit for Non-Hispanic/Latinx white students=1.55). Within each racial and ethnic group, not sure students had greater odds of reporting past month binge drinking than cisgender students, except for non-Hispanic/Latinx white and non-Hispanic/Latinx American Indian or Alaskan Native students, who did not differ from cisgender students in odds of reporting past month binge drinking.

Among cisgender students, all other racial and ethnic groups had lower odds of reporting past month binge drinking than non-Hispanic/Latinx white students, with two exceptions. Non-Hispanic/Latinx American Indian or Alaskan Native students (AOR=1.14, 95% CI=1.03—1.25) and Hispanic/Latinx Black or African American students (AOR=1.15, 95% CI=1.03—1.29) had greater odds of reporting past month binge drinking than non-Hispanic/Latinx white students. Among transgender students, all other racial and ethnic groups had greater odds of reporting past month binge drinking than non-Hispanic/Latinx white students, except for non-Hispanic/Latinx Asian students who did not differ from white students in their odds of reporting past month binge drinking. The greatest disparity among transgender students was among Hispanic/Latinx Black or African American students (AOR=4.55, 95% CI=3.25—6.37) and the smallest was among non-Hispanic/Latinx multiracial students (AOR=1.37, 95% CI=1.08—1.74). Among not sure students, non-Hispanic/Latinx Asian students had lower odds of reporting past month binge drinking than non-Hispanic/Latinx white students (AOR=0.66, 95% CI=0.49—0.89). Further, non-Hispanic/Latinx Black or African American, non-Hispanic/Latinx Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Hispanic/Latinx no race selected, Hispanic/Latinx Asian, Hispanic/Latinx Black or African American, Hispanic/Latinx Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and Hispanic/Latinx multiracial students had greater odds of reporting past month binge drinking than non-Hispanic/Latinx white students. Again, the greatest disparity among not sure students was among Hispanic/Latinx Black or African American students (AOR=5.19, 95% CI=3.52—7.66).

Discussion

Our findings suggest in general transgender adolescents with minoritized racial or ethnic identities are at disproportionate risk of binge drinking compared to cisgender adolescents with minoritized racial or ethnic identities, transgender non-Hispanic/Latinx white adolescents, and cisgender non-Hispanic/Latinx white adolescents. Further, among Hispanic/Latinx adolescents, disparities between transgender and cisgender adolescents varied across racial groups. Overall, these findings are consistent with our hypotheses in that significant interaction terms in our model suggested a greater likelihood of past month binge drinking among adolescents with a minoritized gender identity and a minoritized racial and/or ethnic identity. Further, we found support for our hypotheses that cisgender adolescents with minoritized racial or ethnic identities generally reported binge drinking less than non-Hispanic/Latinx white cisgender adolescents, yet transgender adolescents with minoritized racial or ethnic identities generally reported binge drinking more than non-Hispanic/Latinx white transgender adolescents. Adolescents who were not sure about their gender identity, followed a similar pattern in past month binge drinking to transgender adolescents albeit with smaller magnitudes in disparities. However, we are cautious in interpreting these students as questioning their gender identity as it is possible that some respondents did not understand the question. Similar measures of gender identity, such as an item piloted in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey in 10 states and 9 urban school districts, have included the response option “I do not understand what this question is asking” (2.1%) in addition to “I am not sure if I am transgender” (1.6%) which may help differentiate students who are questioning their gender identity from students who do not understand the question (Michelle M Johns et al., 2019).

Elevated prevalence of past month binge drinking could potentially increase the risk for adverse drinking-related health outcomes among transgender adolescents and adolescents questioning their gender identity with minoritized racial or ethnic identities. These outcomes include HIV and other STI infection, motor vehicle accidents, violence, use of other substances, and disordered alcohol use (Chung et al., 2018; Clark Goings et al., 2019; Garofalo, Deleon, Osmer, Doll, & Harper, 2006; Hotton, Garofalo, Kuhns, & Johnson, 2013; Kerr-Corrêa et al., 2017). Additionally, these disparities may increase negative academic outcomes such as poor academic achievement and absenteeism (An et al., 2017; Maynard et al., 2017; Patte et al., 2017). It is important to note drinking-related negative consequences among specific subgroups of race, ethnicity, and gender may be more severe (Chartier & Caetano, 2010; Coulter et al., 2015; Zapolski, Pedersen, McCarthy, & Smith, 2014). For example, adolescents with minoritized racial or ethnic identities who use alcohol may be more likely to experience alcohol use disorder in adulthood, likely driven by exposure to chronic systemic racism such as discrimination in housing, employment, and health services (Chartier & Caetano, 2010; Zapolski et al., 2014). Similarly, transgender adolescents may be more likely than their cisgender peers to experience suicidality or sexual assault following binge drinking, likely driven by exposure to systemic cisgenderism such as a lack of social or institutional support (Coulter et al., 2015). Thus, the magnitude of disparities in binge drinking at the intersection of race, ethnicity, and gender in this study may underestimate the disparities in the consequences of binge drinking at the same intersections.

Unlike previous research (Clark Goings et al., 2019; Jones et al., 2020), our analysis modeled race and ethnicity across the full range of responses available in our measures. Although race and ethnicity are generally considered to be distinct constructs (Ford & Harawa, 2010), many Hispanic/Latinx adolescents do not respond to survey questions about race, as is evident in our sample. Qualitative work highlights the complexity with how Hispanic/Latinx youth respond to questions about race and ethnicity (Flores-González et al., 2014). Our findings highlight how racial subgroups of the Hispanic/Latinx ethnic group may binge drink more than others. For example, among Hispanic/Latinx Black adolescents (sometimes referred to as AfroLatinx (Salas Pujols, 2020)), disparities in binge drinking between transgender and cisgender students appeared greater than disparities among Hispanic/Latinx youth who also identified as white, multiracial, or selected no race. These findings align with previous work that has found an association between darker skin tone and poor mental health among Hispanic/Latinx women (Torres, Mata-Greve, Bird, & Herrera Hernandez, 2018). Taken together, this implies a need for greater attention to race and ethnicity in intersectional health disparities research, by recognizing them as separate but related constructs.

Within ethnicity, more can be done to unpack the diversity with which people identity. For example, within the umbrella term Hispanic/Latinx are heterogeneous subgroups who may not share the same binge drinking experiences (Siqueira & Crandall, 2008). Further, more nuanced conceptualizations of ethnicity that include groups beyond the Hispanic/Latinx communities could reveal additional intersections at disproportionate risk of alcohol use behaviors. For example, pooled estimates of alcohol use among Asian Americans may under estimate the prevalence of such behaviors for specific subgroups including Filipino, Japanese, and Korean American adolescents (Kane et al., 2017). Additionally, alcohol use is also prevalent among Arab American and other Middle Eastern American adolescent and young adults (Arfken, Arnetz, Fakhouri, Ventimiglia, & Jamil, 2011), who may have culturally specific risk factors for such behaviors (Arfken, Owens, & Said, 2012). Greater attention to ethnicity in health disparities research can increase our understanding of culturally specific contextual factors that may relate to alcohol use and help tailor interventions.

Although our findings document nuanced intersectional disparities in adolescent binge drinking across gender identity, race, and ethnicity, this should not be interpreted to mean these disparities are inherent or caused by racial, ethnic, or gender identity. Rather, it is important to contextualize these findings as likely due to interlocking systems of oppression (i.e., cisgenderism and racism) (Bowleg, 2012). Previous work has emphasized the mediational role of interpersonal stigma on substance use (Coulter, Bersamin, Russell, & Mair, 2018; Hatchel & Marx, 2018), a potential target for intervention work (Layland et al., 2020). However, the Gender Minority Stress Model emphasizes the importance of resilience factors, and research in this area for transgender youth is limited (Delozier et al., 2020; Michelle Marie Johns, Beltran, Armstrong, Jayne, & Barrios, 2018). In addition to individual resilience, such work should focus on parents and schools as potential targets for research and intervention (Andrzejewski, Pampati, Steiner, Boyce, & Johns, 2020; Michelle M Johns et al., 2021). Further, more studies designed to understand the social and structural drivers of intersectional disparities for diverse transgender adolescents are needed, and this study may serve as a call to action for future intersectional studies of alcohol use prevention and intervention research.

Limitations and strengths

Our study has some notable limitations. First, all measures were self-reported, which may bias our estimates. Students may under report binge drinking due to social desirability, however anonymous data collection may help to alleviate such biases (Bjarnason & Adalbjarnardottir, 2000). Second, binge drinking was measured as 5 or more drinks in a row, which may underestimate binge drinking for younger aged adolescents as a blood alcohol concentration of 0.08 g/dL, along with acute impairment of motor coordination and cognitive functioning may occur with less consumption compared to older adolescents (Chung et al., 2018). Third, our sample of high school students in California may not include adolescents at the greatest risk of binge drinking who are more likely to be absent from school (Maynard et al., 2017). Further, transgender students are also less likely to be in school due to experiences of violence and discrimination (Day, Perez-Brumer, & Russell, 2018; Pampati et al., 2020). Therefore, disparities in binge drinking between transgender and cisgender adolescents may be greater than our estimates if transgender adolescents who binge drank in the past month are not in school on days these data were collected. Fourth, our findings may not generalize to adolescents beyond the state of California. Fifth, the CHKS item measuring gender identity only allows participants to indicate if they are or are not transgender, or if they are unsure if they are transgender, rather than using a recommended two-step approach (Badgett et al., 2014). Evidence indicates that this method of assessing gender identity fails to capture some people who are nonbinary but do not consider themselves to be transgender (Bauer, Braimoh, Scheim, & Dharma, 2017). Thus, we were unable to disaggregate transgender students in our analyses (e.g., transgender women, transgender men, and nonbinary people)Future work should consider integrating a two-step approach to improve measurement of sex assignment at birth and current gender identity. Previous research suggests problematic alcohol use may be greater for transgender men than transgender women (Scheim, Bauer, & Shokoohi, 2016), and less is known about binge drinking disparities among nonbinary adolescents. A greater understanding of these disparities may inform prevention efforts. Sixth, recent research suggests that odds of binge drinking among transgender youth may differ by sexual orientation (Gerke et al., 2022). Because we sought to estimate the independent effects of gender identity separate from the effects of sexual orientation to avoid the common pitfall of conflating sexual orientation and gender identity, we adjusted for sexual orientation in our statistical models. This approach may overlook nuances at the intersection of gender identity and sexual orientation, which should be the focus of future research.

Despite these limitations, our study has notable strengths. First, we used a large statewide sample of racially and ethnically diverse middle and high school students to assess intersectional disparities in binge drinking. This focus on harmful alcohol use rather than alcohol use in general is also notable, as it may be more indicative of negative health consequences in adulthood (Chung et al., 2018). Finally, we describe disparities at the intersection of gender identity, race, and ethnicity with a large enough sample to disaggregate racial and ethnic categories to the extent possible with our measures, providing an opportunity for greater precision to examine disparities within the often overly-general “Hispanic/Latinx” ethnicity category (Lett et al., 2022).

Conclusions

Transgender adolescents with minoritized racial and ethnic identities are at disproportionate risk of binge drinking, likely driven by interlocking systems of privilege and oppression (i.e., cisgenderism and racism). Alcohol use prevention interventions specific to these populations are needed. Research on protective factors suggests several avenues for prevention efforts such as within families, schools, and health systems. More work is needed to understand the mechanisms, particularly at the organization and policy levels, which can inform intervention development (del Río-González, Holt, & Bowleg, 2021). Such work would benefit from engaging transgender youth of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds to collaborate equitably with health research scientists on efforts to address systemic inequalities in schools and health care settings, prioritizing the co-production of knowledge and youth-identified strategies for intervention.

Funding/support:

Jack Andrzejewski is supported by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number T32DA023356. Jennifer Felner is supported by the CA Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program under Award Number T29FT0265 and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), NIH under Award Number U54MD012397. Laramie. R. Smith is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), NIH under Award Number R01MH12382. The funders/sponsors did not participate in the work. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Biographies

Jack Andrzejewski, MPH (pronouns: they/them/theirs) is currently a student in the San Diego State University—University of California, San Diego Joint Doctoral Program in Public Health, Health Behavior Track. Their work focuses on mental health, substance use, and sexual health among transgender populations. In particular they are interested in how social determinants of health such as racism, family acceptance, and access to gender affirming health care shape health outcomes for transgender folks.

Jerel P. Calzo, PhD, MPH (pronouns: he/him/his) is an Associate Professor in the Division of Health Promotion and Behavioral Science and Associate Director for Academic Affairs in the School of Public Health at San Diego State University. He is a developmental psychologist with postdoctoral training in social epidemiology. His current research interests include partnering with school and community-based programs to develop evidence-based practices to support positive youth development and resilience among LGBTQIA+ youth, and using survey and mixed method research designs to examine and address health inequities among LGBTQIA+ populations, particularly in the areas of eating disorders and substance use.

Laramie Smith, PhD (pronouns: she/her/hers) is an Associate Professor in the Division of Infectious Diesease and Global Public Health in the School of Medicine at UC San Diego. She is also the co-director of the San Diego State University—University of California, San Diego Joint Doctoral Program in Interdisciplinary Research on Substance Use. Her work focuses on identifying intersectional stigma intervention targets for people who inject drugs and social network approaches to study the effects of stigma on HIV prevention among Latino men who have sex with men.

Heather L. Corliss, MPH, PhD (pronouns: she/her/hers) is a Professor in the Division of Health Promotion and Behavioral Science in the School of Public Health at San Diego State University. She is a social and behavioral epidemiologist whose research focuses primarily on identifying and addressing health disparities among LGBTQ+ populations.

Jennifer K. Felner, PhD, MPH (pronouns: she/her/hers) is an Assistant Professor and Undergraduate Program Director in the School of Public Health at San Diego State University. In her research, Jennifer partners with community-based organizations and community members to identify and address social and structural determinants of health inequities among LGBTQ+ youth and youth experiencing homelessness. She has experience as a public health practitioner addressing child maltreatment via community- and clinically- based education and has been a long-time volunteer for youth- and adult- serving community-based organizations in Atlanta, Georgia, Chicago, Illinois, and San Diego, California.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: “The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.”

References

- An BP, Loes CN, & Trolian TL (2017). The relation between binge drinking and academic performance: Considering the mediating effects of academic involvement. Journal of College Student Development, 58(4), 492–508. [Google Scholar]

- Andrzejewski J, Pampati S, Steiner RJ, Boyce L, & Johns MM (2020). Perspectives of transgender youth on parental support: qualitative findings from the resilience and transgender youth study. Health Education & Behavior, 1090198120965504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arfken CL, Arnetz BB, Fakhouri M, Ventimiglia MJ, & Jamil H (2011). Alcohol use among Arab Americans: what is the prevalence? Journal of immigrant and minority health, 13(4), 713–718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arfken CL, Owens D, & Said M (2012). Binge drinking among Arab/Chaldeans: An exploratory study. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse, 11(4), 277–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badgett M, Baker K, Conron K, Gates G, Gill A, & Greytak E (2014). Best practices for asking questions to identify transgender and other gender minority respondents on population-based surveys (GenIUSS). In: Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, UCLA School of Law. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR, Braimoh J, Scheim AI, & Dharma C (2017). Transgender-inclusive measures of sex/gender for population surveys: Mixed-methods evaluation and recommendations. PloS one, 12(5), e0178043–e0178043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0178043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer GR, Churchill SM, Mahendran M, Walwyn C, Lizotte D, & Villa-Rueda AA (2021). Intersectionality in quantitative research: A systematic review of its emergence and applications of theory and methods. SSM - Population Health, 14, 100798. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjarnason T, & Adalbjarnardottir S (2000). Anonymity and confidentiality in school surveys on alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis use. Journal of Drug Issues, 30(2), 335–343. [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. American journal of public health, 102(7), 1267–1273. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3477987/pdf/AJPH.2012.300750.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier K, & Caetano R (2010). Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research. Alcohol Research & Health, 33(1–2), 152. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung T, Creswell KG, Bachrach R, Clark DB, & Martin CS (2018). Adolescent Binge Drinking. Alcohol research : current reviews, 39(1), 5–15. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30557142 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6104966/ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6104966/pdf/arcr-39-1-e1_a01.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark Goings T, Salas-Wright CP, Belgrave FZ, Nelson EJ, Harezlak J, & Vaughn MG (2019). Trends in binge drinking and alcohol abstention among adolescents in the US, 2002–2016. Drug Alcohol Depend, 200, 115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.02.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, Fisher LB, & Austin SB (2008). Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents: Findings from the Growing Up Today Study. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 162(11), 1071–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RW, Bersamin M, Russell ST, & Mair C (2018). The effects of gender-and sexuality-based harassment on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender substance use disparities. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(6), 688–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulter RW, Blosnich JR, Bukowski LA, Herrick A, Siconolfi DE, & Stall RD (2015). Differences in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems between transgender-and nontransgender-identified young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend, 154, 251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. u. Chi. Legal f, 139. [Google Scholar]

- Day JK, Fish JN, Perez-Brumer A, Hatzenbuehler ML, & Russell ST (2017). Transgender youth substance use disparities: Results from a population-based sample. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(6), 729–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day JK, Perez-Brumer A, & Russell ST (2018). Safe schools? Transgender youth’s school experiences and perceptions of school climate. Journal of youth and adolescence, 47(8), 1731–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Río-González AM, Holt SL, & Bowleg L (2021). Powering and Structuring Intersectionality: Beyond Main and Interactive Associations. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 49(1), 33–37. doi: 10.1007/s10802-020-00720-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delozier AM, Kamody RC, Rodgers S, & Chen D (2020). Health disparities in transgender and gender expansive adolescents: A topical review from a minority stress framework. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(8), 842–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ME, Gower AL, McMorris BJ, Rider GN, Shea G, & Coleman E (2017). Risk and protective factors in the lives of transgender/gender nonconforming adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61(4), 521–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergus E (2016). Understanding Latino student racial and ethnic identification: Theories of race and ethnicity. Theory into practice, 55(1), 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Fish JN, & Baams L (2018). Trends in alcohol-related disparities between heterosexual and sexual minority youth from 2007 to 2015: Findings from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey. LGBT Health, 5(6), 359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-González N, Aranda E, & Vaquera E (2014). “Doing Race”:Latino Youth’s Identities and the Politics of Racial Exclusion. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(14), 1834–1851. doi: 10.1177/0002764214550287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ford CL, & Harawa NT (2010). A new conceptualization of ethnicity for social epidemiologic and health equity research. Social Science & Medicine, 71(2), 251–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Deleon J, Osmer E, Doll M, & Harper GW (2006). Overlooked, misunderstood and at-risk: Exploring the lives and HIV risk of ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(3), 230–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerke DR, Call J, Atteberry‐Ash B, Katz‐Kattari S, Kattari L, & Hostetter CR (2022). Alcohol use at the intersection of sexual orientation and gender identity in a representative sample of youth in Colorado. The American Journal on Addictions, 31(1), 61–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert PA, Pass LE, Keuroghlian AS, Greenfield TK, & Reisner SL (2018). Alcohol research with transgender populations: A systematic review and recommendations to strengthen future studies. Drug Alcohol Depend, 186, 138–146. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5911250/pdf/nihms952361.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchel T, & Marx R (2018). Understanding Intersectionality and Resiliency among Transgender Adolescents: Exploring Pathways among Peer Victimization, School Belonging, and Drug Use. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 15(6). doi: 10.3390/ijerph15061289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks ML, & Testa RJ (2012). A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: An adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460. [Google Scholar]

- Hotton AL, Garofalo R, Kuhns LM, & Johnson AK (2013). Substance use as a mediator of the relationship between life stress and sexual risk among young transgender women. AIDS Educ Prev, 25(1), 62–71. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2013.25.1.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Beltran O, Armstrong HL, Jayne PE, & Barrios LC (2018). Protective factors among transgender and gender variant youth: A systematic review by socioecological level. The journal of primary prevention, 39(3), 263–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, Barrios LC, Demissie Z, McManus T, … Underwood JM (2019). Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68(3), 67. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6348759/pdf/mm6803a3.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns MM, Zamantakis A, Andrzejewski J, Boyce L, Rasberry CN, & Jayne PE (2021). Minority Stress, Coping, and Transgender Youth in Schools—Results from the Resilience and Transgender Youth Study. Journal of school health. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones CM, Clayton HB, Deputy NP, Roehler DR, Ko JY, Esser MB, … Hertz MF (2020). Prescription Opioid Misuse and Use of Alcohol and Other Substances Among High School Students—Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019. MMWR supplements, 69(1), 38. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7440199/pdf/su6901a5.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane JC, Damian AJ, Fairman B, Bass JK, Iwamoto DK, & Johnson RM (2017). Differences in alcohol use patterns between adolescent Asian American ethnic groups: Representative estimates from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2002–2013. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 154–158. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.08.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr-Corrêa F, Pinheiro Júnior FML, Martins TA, Costa D. L. d. C., Macena RHM, Mota RMS, … Kerr LRFS (2017). Hazardous alcohol use among transwomen in a Brazilian city. Cadernos de saude publica, 33, e00008815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knol MJ, & VanderWeele TJ (2012). Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. International journal of epidemiology, 41(2), 514–520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosciw JG, Clark CM, Truong NL, & Zongrone AD (2020). The 2019 National School Climate Survey: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Youth in Our Nation’s Schools. A Report from GLSEN: ERIC. [Google Scholar]

- Layland EK, Carter JA, Perry NS, Cienfuegos-Szalay J, Nelson KM, Bonner CP, & Rendina HJ (2020). A systematic review of stigma in sexual and gender minority health interventions. Translational Behavioral Medicine, 10(5), 1200–1210. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibz200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon E, & Mistler BJ (2014). Cisgenderism. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1(1–2), 63–64. doi: 10.1215/23289252-2399623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lett E, Asabor E, Beltrán S, Michelle Cannon A, & Arah OA (2022). Conceptualizing, Contextualizing, and Operationalizing Race in Quantitative Health Sciences Research. The Annals of Family Medicine, 2792. doi: 10.1370/afm.2792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry R, Kann L, Collins JL, & Kolbe LJ (1996). The effect of socioeconomic status on chronic disease risk behaviors among US adolescents. Jama, 276(10), 792–797. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, King KM, Miles J, Gold MA, … Morse JQ (2008). Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: a meta‐analysis and methodological review. Addiction, 103(4), 546–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard BR, Vaughn MG, Nelson EJ, Salas-Wright CP, Heyne DA, & Kremer KP (2017). Truancy in the United States: Examining temporal trends and correlates by race, age, and gender. Children and youth services review, 81, 188–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereish EH (2018). Addressing Research Gaps in Sexual and Gender Minority Adolescents’ Substance Use and Misuse. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(6), 645–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EJ, & Keenan H (2018). Can policies help schools affirm gender diversity? A policy archaeology of transgender-inclusive policies in California schools. Gender and Education, 30(6), 736–753. [Google Scholar]

- Pampati S, Andrzejewski J, Sheremenko G, Johns M, Lesesne CA, & Rasberry CN (2020). School climate among transgender high school students: An exploration of school connectedness, perceived safety, bullying, and absenteeism. The Journal of School Nursing, 36(4), 293–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patte KA, Qian W, & Leatherdale ST (2017). Marijuana and alcohol use as predictors of academic achievement: a longitudinal analysis among youth in the COMPASS study. Journal of school health, 87(5), 310–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salas Pujols J (2020). ‘It’s About the Way I’m Treated’: Afro-Latina Black Identity Development in the Third Space. Youth & Society, 0044118X20982314. [Google Scholar]

- Scheim AI, Bauer GR, & Shokoohi M (2016). Heavy episodic drinking among transgender persons: Disparities and predictors. Drug Alcohol Depend, 167, 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh AA (2013). Transgender youth of color and resilience: Negotiating oppression and finding support. Sex Roles, 68(11), 690–702. [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira LM, & Crandall LA (2008). Risk and protective factors for binge drinking among Hispanic subgroups in Florida. Journal of ethnicity in substance abuse, 7(1), 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spade D (2015). Normal life. In Normal Life: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Subica AM, & Wu L-T (2018). Substance use and suicide in Pacific Islander, American Indian, and multiracial youth. American journal of preventive medicine, 54(6), 795–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan KK, Treharne GJ, Ellis SJ, Schmidt JM, & Veale JF (2019). Gender minority stress: A critical review. Journal of Homosexuality. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, Mata-Greve F, Bird C, & Herrera Hernandez E (2018). Intersectionality research within Latinx mental health: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 6(4), 304. [Google Scholar]

- Truong NL, Zongrone AD, & Kosciw JG (2020). Erasure and Resilience: The Experiences of LGBTQ Students of Color. Black LGBTQ Youth in US Schools: ERIC. [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JS, Pollard MS, de la Haye K, Kennedy DP, & Green HD Jr (2013). Neighborhood characteristics and the initiation of marijuana use and binge drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend, 128(1–2), 83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WestEd for the California Department of Education. (2021). CalSCHLS Survey Adminstration. Retrieved from https://calschls.org/survey-administration/

- Zapolski TC, Pedersen SL, McCarthy DM, & Smith GT (2014). Less drinking, yet more problems: understanding African American drinking and related problems. Psychological bulletin, 140(1), 188. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3758406/pdf/nihms456621.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]