Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular disease is the most frequent cause of death in people with early stages of chronic kidney disease (CKD), and the absolute risk of cardiovascular events is similar to people with coronary artery disease. This is an update of a review first published in 2009 and updated in 2014, which included 50 studies (45,285 participants).

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of statins compared with placebo, no treatment, standard care or another statin in adults with CKD not requiring dialysis.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies up to 4 October 2023. Studies in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, conference proceedings, the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov. An updated search will be undertaken every three months.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs that compared the effects of statins with placebo, no treatment, standard care, or other statins, on death, cardiovascular events, kidney function, toxicity, and lipid levels in adults with CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 90 to 15 mL/min/1.73 m2) were included.

Data collection and analysis

Two or more authors independently extracted data and assessed the study risk of bias. Treatment effects were expressed as mean difference (MD) for continuous outcomes and risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous benefits and harms with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool, and the certainty of the evidence using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach.

Main results

We included 63 studies (50,725 randomised participants); of these, 53 studies (42,752 participants) compared statins with placebo or no treatment. The median duration of follow‐up was 12 months (range 2 to 64.8 months), the median dosage of statin was equivalent to 20 mg/day of simvastatin, and participants had a median eGFR of 55 mL/min/1.73 m2. Ten studies (7973 participants) compared two different statin regimens. We were able to meta‐analyse 43 studies (41,273 participants). Most studies had limited reporting and hence exhibited unclear risk of bias in most domains.

Compared with placebo or standard of care, statins prevent major cardiovascular events (14 studies, 36,156 participants: RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.79; I2 = 39%; high certainty evidence), death (13 studies, 34,978 participants: RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.96; I² = 53%; high certainty evidence), cardiovascular death (8 studies, 19,112 participants: RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.87; I² = 0%; high certainty evidence) and myocardial infarction (10 studies, 9475 participants: RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.73; I² = 0%; moderate certainty evidence). There were too few events to determine if statins made a difference in hospitalisation due to heart failure. Statins probably make little or no difference to stroke (7 studies, 9115 participants: RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.08; I² = 39%; moderate certainty evidence) and kidney failure (3 studies, 6704 participants: RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.05; I² = 0%; moderate certainty evidence) in people with CKD not requiring dialysis.

Potential harms from statins were limited by a lack of systematic reporting. Statins compared to placebo may have little or no effect on elevated liver enzymes (7 studies, 7991 participants: RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.50; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence), withdrawal due to adverse events (13 studies, 4219 participants: RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.60; I² = 37%; low certainty evidence), and cancer (2 studies, 5581 participants: RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.30; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence). However, few studies reported rhabdomyolysis or elevated creatinine kinase; hence, we are unable to determine the effect due to very low certainty evidence. Statins reduce the risk of death, major cardiovascular events, and myocardial infarction in people with CKD who did not have cardiovascular disease at baseline (primary prevention). There was insufficient data to determine the benefits and harms of the type of statin therapy.

Authors' conclusions

Statins reduce death and major cardiovascular events by about 20% and probably make no difference to stroke or kidney failure in people with CKD not requiring dialysis. However, due to limited reporting, the effect of statins on elevated creatinine kinase or rhabdomyolysis is unclear. Statins have an important role in the primary prevention of cardiovascular events and death in people who have CKD and do not require dialysis.

Editorial note: This is a living systematic review. We will search for new evidence every three months and update the review when we identify relevant new evidence. Please refer to the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for the current status of this review.

Keywords: Adult; Humans; Creatinine; Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors; Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors/adverse effects; Myocardial Infarction; Myocardial Infarction/prevention & control; Renal Dialysis; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic/complications; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic/therapy; Rhabdomyolysis; Rhabdomyolysis/chemically induced; Rhabdomyolysis/drug therapy; Stroke; Stroke/drug therapy; Systematic Reviews as Topic

Plain language summary

Statins can help reduce risk of death in people with chronic kidney disease who do not need dialysis

What is the issue? Adults with chronic kidney disease (CKD) have a high risk of cardiovascular events, with elevated serum cholesterol and triglycerides, a factor that contributes to cardiovascular disease. Statin therapy helps to lower the level of bad cholesterol (low‐density lipoprotein) and has cardiovascular protective effects beyond cholesterol reduction. For people not needing dialysis, statin therapy has been shown to reduce death and cardiovascular events. Still, studies in this population have shown unclear effects on stroke, kidney failure, and harms such as muscle damage (rhabdomyolysis).

What did we do? We looked at 62 studies published before 4 October 2023 concerning statins in over 50,000 people with CKD who did not need dialysis treatment. This review is a living systematic review. A search for new evidence will be conducted every three months, and the review will be updated accordingly.

What did we find?

We found that compared to placebo, statin therapy reduced death and major heart‐related events, with one in 13 people receiving statin therapy avoiding heart‐related events and one in 26 people avoiding death. Statin therapy probably had little or no effect on stroke and kidney failure (when people would benefit from dialysis or a kidney transplant). The benefits of statin therapy were also evident in patients with CKD but not heart disease. Statins have some potential harms; however, we found there was probably no effect on cancer, liver function or withdrawing from treatment due to adverse events. There was limited reporting of muscle damage in the studies.

Studies did not identify a preferred type or dose of statin in treating people with CKD not requiring dialysis.

Conclusions Statins decrease death, major cardiovascular events, and myocardial infarction in people with moderate CKD. Limited data related to treatment toxicity resulted in uncertain effects.

Editorial note: Please refer to the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews for the current status of this review.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Statin therapy versus placebo or standard of care for people with chronic kidney disease not requiring dialysis.

| Statin therapy versus placebo or standard of care for people with chronic kidney disease not requiring dialysis | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with chronic kidney disease not requiring dialysis Setting: primary and tertiary care Intervention: statin therapy Comparison: placebo or standard of care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (RCTs) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with placebo or standard of care | Risk with statin therapy | |||||

| Major cardiovascular events (MACE) follow up: mean 46 months | 6 per 1,000 | 5 per 1,000 (4 to 5) | RR 0.72 (0.66 to 0.79) | 36156 (14) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Statin therapy reduces major cardiovascular events |

| Death follow up: mean 40 months | 3 per 1,000 | 2 per 1,000 (2 to 3) | RR 0.83 (0.73 to 0.96) | 34978 (13) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ HIGH | Statin therapy reduces death |

| Rhabdomyolysis follow up: mean 64 months | 1 per 1,000 | 2 per 1,000 (0 to 59) | RR 3.07 (0.13 to 75.37) | 2618 (2) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of statin therapy on rhabdomyolysis |

| Myocardial infarction follow up: mean 39 months | 3 per 1,000 | 2 per 1,000 (1 to 2) | RR 0.55 (0.42 to 0.73) | 9475 (10) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | Statin therapy probably reduces myocardial infarction |

| Stroke follow up: mean 40 months | 13 per 1,000 | 8 per 1,000 (5 to 14) | RR 0.64 (0.37 to 1.08) | 9158 (7) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 3 | Statin therapy probably results in little to no difference in stroke |

| Kidney failure follow up: mean 34 months | 2 per 1,000 | 2 per 1,000 (2 to 2) | RR 0.98 (0.91 to 1.05) | 6704 (3) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 2 | Statin therapy probably results in little to no difference in kidney failure |

| Hospitalisation due to heart failure follow up: 54 months | 75 per 1,000 | 53 per 1,000 (28 to 99) | RR 0.70 (0.37 to 1.32) | 579 (1) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 4 5 | Statin therapy may result in little to no difference in hospitalisation due to heart failure |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the baseline risk of outcomes from observational studies (and its 95%CI) . The relevant studies in the Summary of Findings Table are listed below: Major cardiovascular events and death ‐ Go 2004 Rhabdomyolysis ‐ based on the assumed risk of outcomes in the comparison group Myocardial infarction ‐ Meisinger 2006 Stroke and hospitalisation due to heart failure ‐ Bansal 2017 Kidney failure ‐ Dalrymple 2011 CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; MACE: Major Adverse Cardiac Events | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Very few events

2 Inadequate sequence generation/ generation of comparable groups, resulting in potential for selection bias

3 Effect estimates were on both side of the null

4 Inadequate/lack of blinding of participants and personnel, resulting in potential for performance bias, Inadequate concealment of allocation during randomisation process, resulting in potential for selection bias,

5 Only one study

Background

Description of the condition

The incidence and prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) are increasing, with a global prevalence estimated at around 10% (Global Burden of Disease CKD Collaboration 2020). CKD is a known risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Go 2004). Overall cardiovascular deaths are more common than progression to kidney failure in patients with CKD (Gargiulo 2015). For patients with severe kidney disease on long‐term dialysis, 39% of deaths are attributable to cardiovascular causes (USRDS 2019). People with moderate CKD not on dialysis experience risks of death or complications from CVD equivalent to people with heart disease (Go 2004; Henry 2002).

Description of the intervention

HMG‐CoA reductase inhibitors, known as statins, are a commonly prescribed class of cholesterol‐lowering medications used in the primary prevention of atherosclerotic CVD and secondary prevention for those who have developed CVD (Sidebottom 2020). Ezetimibe is another cholesterol‐lowering medication class which has been examined in combination with statins in clinical trials (SHARP 2010).

How the intervention might work

Many traditional and non‐traditional cardiovascular risk factors are prevalent in people with CKD (Muntner 2005; Shilpak 2005). The majority (60%) of people with CKD have elevated serum cholesterol and triglycerides levels and an even higher proportion in those with nephrotic syndrome (Harris 2002). Abnormal lipid levels may contribute to the development of CVD and the initiation and progression of CKD (Drueke 2001; Schaeffner 2003). In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC) and Physicians Health study, elevated lipid levels were associated with lower kidney function (Manjunath 2003). Apart from their lipid‐lowering function, it is plausible that statin use may result in improved kidney function by decreasing urinary protein excretion and inflammation and reducing fibrosis of tubular cells (Kasiske 1988). Ezetimibe prevents intestinal cholesterol absorption through inhibition of the synthetic 2‐azetidinone agent at the brush border of the small intestine (StatPearls Textbook), while statins could reduce kidney disease progression and CVD incidence in people with kidney dysfunction (Massy 2001). Clinical studies in people with CVD have shown that statins safely reduce the five‐year incidence of death or major cardiovascular events by about 20% (Baigent 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

In previous versions of this review published in 2009 and 2014, statins proportionally reduced the risk of death and major cardiovascular events in people with CKD. However, the risks of stroke, adverse events (muscle or liver damage), and kidney failure in these studies were uncertain due to few reported events (Palmer 2014). The previous version of this review relied on the post‐hoc analysis of larger general population studies. Additional studies have been published, warranting a review update. This review has transitioned to a living systematic review. Clinical practice guidelines recommend using statins with or without ezetimibe for people with CKD, not on dialysis (CARI 2013; KDIGO 2013). The Caring for Australian and New ZealandeRs with Kidney Impairment (CARI) Guideline is being updated, and this review will form the underlying evidence review for guideline recommendations.

Objectives

To evaluate the benefits and harms of statin therapy compared with placebo, standard care without statin therapy, or another different statin in adults with CKD who were not on dialysis. A secondary objective is to maintain the currency of the evidence using a living systematic review approach.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) that evaluated the benefits and harms of statins in adults with CKD who were not on dialysis. The first period of randomised cross‐over studies was included. We excluded studies of fewer than eight weeks duration as these studies were unlikely to enable detection of death or cardiovascular outcomes related to statin therapy (Briel 2006).

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

We included studies enrolling adults with CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) 90 to 15 mL/min/1.73 m2) (defined and staged according to Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines) (KDIGO 2012) who were not on dialysis, including people with persistent urine abnormalities (proteinuria or albuminuria) or structural kidney disease with normal kidney function. Studies were included irrespective of whether participants had CVD at baseline.

Exclusion criteria

Studies of adults with kidney failure treated with dialysis (peritoneal dialysis or haemodialysis) and recipients of a kidney transplant were excluded. Other Cochrane Reviews have specifically reviewed these populations (Palmer 2013; Palmer 2014a).

Types of interventions

We included studies that compared statins with placebo, standard care without statin therapy, or another statin. We excluded studies where a statin was compared with a different lipid‐lowering strategy, including fibrate therapy and ezetimibe.

Types of outcome measures

Standardised Outcomes in NephroloGy (SONG) is currently developing a core outcome set for CKD. This finalised core outcome set will be incorporated in updated versions of this review.

Primary outcomes

Major cardiovascular events

Death

Rhabdomyolysis

Secondary outcomes

Cardiovascular death

Myocardial infarction (MI) (fatal and non‐fatal)

Stroke (fatal and non‐fatal)

Hospitalisation due to heart failure

Kidney failure

Doubling of serum creatinine (SCr)

Acute kidney injury (AKI)

Elevated creatine kinase

Elevated liver enzymes

Withdrawal due to adverse events

Cancer

Onset of diabetes

Revascularisation procedure

End of treatment creatinine clearance (CrCl) or GFR (any measure)

End of treatment proteinuria

-

Serum lipid levels

Total cholesterol

Low‐density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol

High‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol

Triglycerides

Fatigue

Life participation

Memory loss

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies to 4 October 2023 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Register contains studies identified from the following sources:

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Searches of kidney and transplant journals and the proceedings and abstracts from major kidney and transplant conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Register are identified through searches of CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of search strategies, and a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available on the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant website.

See Appendix 1 for search terms used in strategies for this review.

Living systematic review considerations

An updated search of the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies will be undertaken every three months.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Contacting relevant individuals/organisations seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies.

Grey literature sources (e.g. abstracts, dissertations and theses) in addition to those already included in the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies will be searched.

Living systematic review considerations

References lists of newly identified studies from updated searches were checked, and relevant individuals and organisations were contacted if appropriate. Grey literature sources screening will not be periodically undertaken during the living evidence surveillance period.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The following processes were used in the current update and previous versions of the review. The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies relevant to the review. Title and abstracts were screened independently by two authors (BC and DJT), who discarded studies that were not eligible. However, studies and reviews thought to include relevant data or information on studies were retained initially for full‐text review. Two authors (BC and DJT) independently assessed retrieved abstracts and the full text, where necessary, to determine which studies satisfied the inclusion criteria. Disagreements between authors were resolved in consultation with a third author (SP).

Living systematic review considerations

The 2023 review update undertook study selection in Covidence (https://www.covidence.org/). Two independent authors (BC and DJT) immediately screened the retrieved citations from three monthly searches. Disagreements were resolved in consultation with a third author (SP).

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by authors (DJT, BC) using Robot Reviewer (https://www.robotreviewer.net/). Data extraction was checked independently by authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped. Data were obtained from all relevant reports, including long‐term follow‐up data if the attrition rate was less than 80% of randomised participants. Any discrepancies between published versions were highlighted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2022) (Appendix 2).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias?

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (major cardiovascular events, death, rhabdomyolysis, kidney failure, doubling of SCr, onset of diabetes, revascularisation procedure, memory loss, elevated liver enzymes, elevated creatine kinase, withdrawal due to adverse events, and cancer), results were expressed as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where continuous scales of measurement were used to assess the effects of treatment (lipid parameters, proteinuria, kidney function (CrCl or eGFR), fatigue, and life participation), the mean difference (MD) was used, or the standardised mean difference (SMD) where different scales were used for outcome measurement.

Unit of analysis issues

Cross‐over RCTs were analysed using only the data from the first period. Studies with multiple treatment arms were included. When considering these studies, we tried to combine all relevant intervention groups into a single group when appropriate, i.e. high‐ and low‐dose statin, to allow a single pairwise comparison. If appropriate, we compared the intervention arms against one another. It was planned that cluster RCTs were not included in the meta‐analysis and were analysed and reported separately. However, no cluster RCTs were included in the review.

Dealing with missing data

Any further information required from the original author was requested, and relevant information was included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data, such as screened or randomised patients and intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated, and per‐protocol population, was performed. Attrition rates, such as drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up, and withdrawals, were investigated, including the balance between treatment groups. Issues of missing data and imputation methods (e.g. last observation carried forward) were critically appraised (Higgins 2022).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We first assessed the heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plot. We then quantified statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic, which describes the percentage of total variation across studies likely due to statistical heterogeneity rather than sampling error (Higgins 2003). A guide to the interpretation of I² values was as follows.

0% to 40%: might not be important

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

The importance of the observed value of I² depended on the magnitude and direction of treatment effects and the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the Chi² test or a CI for I²) (Higgins 2022).

Meta‐regression for age and GFR was undertaken for outcomes with more than 10 studies in which meta‐analysis demonstrated evidence of substantial or considerable heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess potential bias from small‐study effects, we constructed funnel plots for the log risk ratio in individual studies against the standard error of the risk ratio. Statistical assessment of funnel plot asymmetry with the Egger regression test (Harbord 2006) using R (R Core Team 2013 ‐ http://www.R-project.org/) to assess publication bias if required or sufficient data is available).

Data synthesis

Data were pooled using the random‐effects model, but the fixed‐effect model was also used to ensure the robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

The anticipated absolute effects have been calculated from baseline risks reported in published observational studies that examine the incidence of cardiovascular outcomes, death, and kidney failure in people with CKD (Bansal 2017; Dalrymple 2011; Go 2004; Meisinger 2006). These studies were selected as they were large multi‐national observational studies conducted on people with CKD that may be generalisable to the populations in the identified RCTs in this review. When no published data was available, the assumed risk of the outcomes was given by the event rates in the comparison group.

Living systematic review considerations

All included studies in future review updates will undergo data extraction and critical appraisal by two authors (BC and DJT) independently, using Robot Reviewer (https://www.robotreviewer.net/) as a supportive tool. Whenever new evidence (i.e. studies, data or other information) relevant to the review is identified, we will extract the data and assess the risk of bias as appropriate. We will wait until the accumulating evidence changes one or more of the following components of the review before incorporating it and re‐publishing the review.

The findings of one or more primary outcomes

The credibility (e.g. GRADE rating) of one or more primary outcomes

New settings, populations, interventions, comparisons or outcomes were examined

New serious adverse events.

Formal sequential meta‐analysis approaches will not be used for updated meta‐analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

For outcomes with more than 10 studies, we planned to conduct subgroup analyses to explore potential sources of heterogeneity in modifying estimates of the effects of statins if substantial or considerable heterogeneity or significant heterogeneity (P < 0.1) was present in the primary analysis. We planned subgroup analyses according to participant, intervention, or study‐related characteristics when subgroups contained four or more independent studies (statin type, statin dose (equivalent to simvastatin, baseline total cholesterol (< 230 mg/dL versus ≥ 230 mg/dL), age (≤ 55 years versus > 55 years), the proportion with diabetes (≥ 20% versus < 20%), presence or absence of CVD (primary versus secondary prevention), or adequacy of allocation concealment. Additionally, post‐hoc analyses were conducted on the impact of baseline kidney function on the following outcomes: kidney failure, doubling of SCr, end‐of‐treatment kidney function, and end‐of‐treatment proteinuria.

We conducted meta‐regression using a mixed‐effects model with the Metafor package for R (R Core Team 2013) for primary outcomes with more than 10 studies and substantial or considerable heterogeneity. Age and kidney function were considered covariates for meta‐regression.

Sensitivity analysis

The following sensitivity analyses were considered to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size.

Repeating the analysis, excluding unpublished studies

Repeating the analysis taking into account the risk of bias

Repeating the analysis, excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results

Repeating the analysis excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, the language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), and country.

However, there were insufficient data for sensitivity analyses for unpublished studies, risk of bias, the language of publication, and country.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We presented the main results of the review in the 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined, and the sum of the available data for the main outcomes (Schünemann 2022a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence‐related main outcome using the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach (GRADE 2008; GRADE 2011). The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of the within‐trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, the precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schünemann 2022b). We presented the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Major cardiovascular events

Death

Rhabdomyolysis

Cardiovascular death

MI

Stroke

Hospitalisation due to heart failure

Kidney failure

Methods for future updates

Living systematic review considerations

The conduct and production of this living systematic review will be overseen by the CARI Guidelines Living Evidence Working Group and the Statins in CKD Guideline Working Group. We will review the scope and methods when updating the review in light of potential changes in the topic area or new evidence (e.g. when additional comparisons, interventions, subgroups, outcomes, or new review methods become available). At every three‐month search, we will consider the necessity for the review to be living. By assessing the questions' ongoing relevance to decision‐makers and determining if continuing uncertainty in the evidence is present, we will determine whether further relevant research is likely to change recommendations for clinical practice via the CARI Guidelines Statins in CKD Living Guideline.

Results

Description of studies

The following section contains broad descriptions of the studies considered in this review. For further details on each individual study, please see Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification; Ongoing studies.

Results of the search

Previous versions of this Cochrane review (Navaneethan 2009; Palmer 2014) identified 47 studies (39,738 participants) compared statin therapy with placebo or no treatment, and three studies (5547 participants) compared a statin with another statin (Table 2).

1. List of included studies according to Cochrane review update.

2023 review update

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Register of Studies (4 October 2023) and identified 134 new reports. Thirteen new studies (22 reports) were included, 20 (50 reports) were excluded, and one ongoing study was identified. One new study is awaiting classification (recently completed; no data available). We also identified 61 new reports of existing included studies and studies awaiting classification.

We reassessed and reclassified seven ongoing studies: three studies have been included (Ohsawa 2015; PLANET I 2006; PLANET II 2006); four studies were excluded (Mose 2014a; Mose 2014b; Weinstein 2013; Zinellu 2012); and one study has been moved to awaiting classification as no data have been published (NCT00768638). Eighteen previously excluded studies were deleted because they were not randomised (4), enrolled the wrong population (4), or did not use statins (10).

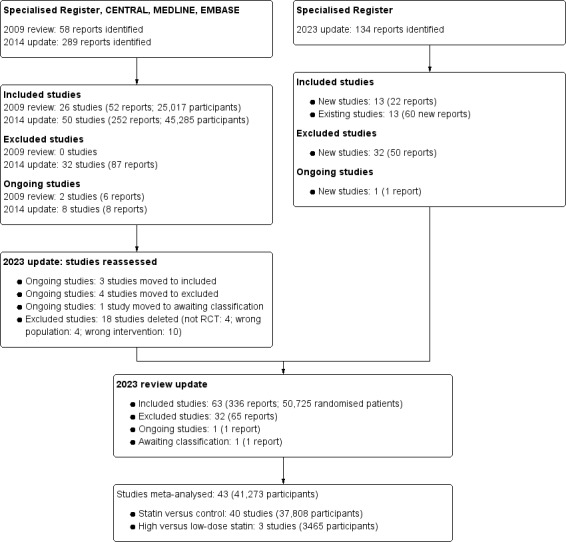

A total of 63 studies were included (336 reports, 50,725 randomised participants), 32 were excluded, two are awaiting classification, and there is one ongoing study (Figure 1).

1.

Flow diagram showing study selection

Included studies

Details are provided in Included studies.

Fifty‐three studies (42,752 randomised participants) compared statin therapy to placebo or no treatment. Nine studies compared high to low‐dose statin (7851 randomised participants), and one study (122 randomised participants) compared continuous‐release versus intermittent‐release statin. Of the 63 included studies, 11 studies provided post hoc data for subgroups of 31,315 adults with CKD within larger studies that compared statins with placebo or no treatment (4S 1993; AFCAPS/TexCAPS 1997; ALLIANCE 2000; ASCOT‐LLA 2003; CARDS 2003; HPS 2002; JUPITER 2007; LIPS 2001; MEGA 2004; PPP 1992; SAGE 2004). Two comparisons provided post hoc data for 5428 adults comparing two statin regimens (IDEAL 2004; TNT 2004). Overall, 43 studies (41,273 participants) contributed to the meta‐analyses.

Statin versus placebo or no treatment

Studies varied in sample size (median 55 participants; range 14 to 3107 participants). Seven comparisons that included more than 1000 participants (4S 1993; ASCOT‐LLA 2003; HPS 2002; JUPITER 2007; MEGA 2004; PPP 1992; SHARP 2010).

The median statin dose (equivalent to simvastatin) was 20 mg (range 5 to 80 mg/day). Twelve studies used simvastatin, 10 studies used atorvastatin, nine studies used pravastatin, nine studies used fluvastatin, four studies used pitavastatin, four studies used rosuvastatin, two studies used lovastatin, one study used cerivastatin, one study used simvastatin with ezetimibe (SHARP 2010). One study used simvastatin or pravastatin (Scanferla 1991) (Table 3).

2. Studies classified by type of statin therapy.

| Atorvastatin (dose) | Cerviastatin (dose) | Fluvastatin (dose) | Lovastatin (dose) | Pitavastatin (dose) | Pravastatin (dose) | Rosuvastatin (dose) | Simvastatin (dose) | Simvastatin and ezetimibe (dose) |

| ALLIANCE 2000 (10 mg/d) | Nakamura 2002 (0.15 mg/d) | Buemi 2000 (40 mg/d) | AFCAPS/TexCAPS 1997 (20 mg/d) | Nakamura 2005 (10 mg/d) | Aranda Arcas 1994 (20 mg/d) | Abe 2011c (5 mg/d) | 4S 1993 (20 mg/d) | SHARP 2010 (20 mg/d and 10 mg/d) |

| ASCOT‐LLA 2003 (10 mg/d) | Cha 2015 (20 mg/d) | Lam 1995 (20 mg/d) | Nakamura 2006 (10 mg/d) | ASUCA 2013 (mean 12.5 mg/d) | JUPITER 2007 (20 mg/d) | Dummer 2008 (20 mg/d) | ||

| Bianchi 2003 (40 mg/d) | Di Lullo 2005 (80 mg/d) | Ohsawa 2015 (20 mg/d) | Imai 1999 (mean 7.5 mg/d) | Sawara 2008 (2.5 mg/d) | Fassett 2010 (10 mg/d) | |||

| CARDS 2003 (10 mg/d) | ESPLANADE 2010 (80 mg/d) | Tokunaga 2008 (40 mg/d) | Lee 2002 (10 mg/d) | Verma 2005 (10 mg/d) | Fried 2001 (10 mg/d) | |||

| Goicoechea 2006 (20 mg/d) | Gheith 2002 (20 mg/d) | MEGA 2004 (15 mg/d) | Hommel 1992 (15 mg/d) | |||||

| Inukai 2011 (10 mg/d) | Lintott 1995 (40 mg/d) | Mori 1992 (10 mg/d) | HPS 2002 (40 mg/d) | |||||

| LORD 2006 (10 mg/d) | LIPS 2001 (20 mg/d) | PPP 1992 (40 mg/d) | Nielsen 1993 (15 mg/d) | |||||

| Masajtis‐Zagajewska 2018 (20 mg/d) | Samuelsson 2002 (40 mg/d) | PREVEND IT 2000 (40 mg/d) | Panichi 2006a (40 mg/d) | |||||

| Renke 2010a (40 mg/d) | Yasuda 2004 (20 mg/d) | Scanferla 1991 (10 mg/d) | Rayner 1996 (25 mg/d) | |||||

| Stegmayr 2005 (10 mg/d) | Zhang 1995 (20 mg/d) | Scanferla 1991 (10 mg/d) | ||||||

| SHARP 2010 (20 mg/d with ezetimibe 10 mg/d) | ||||||||

| Thomas 1993 (40 mg/d) | ||||||||

| Tonolo 1997 (20 mg/d) | ||||||||

| UK‐HARP‐I 2005 (20 mg/d) | ||||||||

| High‐dose statin versus low‐dose statin | ||||||||

| PANDA 2011 (80 mg/d versus 10 mg/d) | PLANET I 2006 (40 mg/d versus 10 mg/d) | |||||||

| TNT 2004 (80 mg/d versus 10 mg/d) | PLANET II 2006 (40 mg/d versus 10 mg/d) | |||||||

The median follow‐up duration was 12 months (range 2 to 66 months). Studies reporting death outcomes that could be included in meta‐analyses had a median follow‐up duration of 44 months (range 5 to 65 months).

Although three studies enrolled participants with established acute or stable coronary artery disease (4S 1993; ALLIANCE 2000; LIPS 2001), 12 studies excluded participants with clinical coronary artery disease (Abe 2011c; AFCAPS/TexCAPS 1997; CARDS 2003; Fried 2001; Imai 1999; JUPITER 2007; Lam 1995; MEGA 2004; Nakamura 2002; Nakamura 2005; Ohsawa 2015; SHARP 2010). Median baseline LDL cholesterol was 143.9 mg/dL (range 108.5 to 189 mg/dL) (3.72 mmol/L; range 2.80 to 4.89 mmol/L)

Ten studies included only participants who had diabetes (Abe 2011c; CARDS 2003; Hommel 1992; Inukai 2011; Lam 1995; Mori 1992; Nakamura 2005; Nielsen 1993; Tonolo 1997; Zhang 1995); and people with diabetes were excluded from eight studies (Bianchi 2003; Gheith 2002; Lee 2002; Nakamura 2002; Nakamura 2006; Ohsawa 2015; Panichi 2006a; Renke 2010a). Stegmayr 2005 combined outcome data for adults not on dialysis with those on dialysis; data from this study were not included in the meta‐analyses.

Effects of statins on adverse events data from SHARP 2010 could not be included in analyses because disaggregated data for 6247 adults with CKD were not available.

The Pravastatin Pooling Project (PPP 1992) was a pooled analysis of three large data sets of participants with kidney impairment who were included in three major statin studies (LIPID 1998; Sacks 1996; Shepherd 1995) conducted in the general population and were included as a single comparison.

High versus low dose statin

PANDA 2011 and TNT 2004 compared two doses of atorvastatin, while PLANET I 2006 and PLANET II 2006 compared low‐ and high‐dose rosuvastatin. The median follow‐up was 24 months (range 12 to 58.8 months). Meta‐analysis was undertaken when two or more studies were available.

Continuous release versus intermittent release statin

Yi 2014 compared continuous‐release statin (20 mg/day) administered in the morning with intermittent‐release statin (20 mg/day) administered in the evening for two months. The study included 122 participants, with a mean LDL cholesterol of 140.5 ± 28.3 mg/day (3.63 ± 0.73 mmol/L).

Statin versus another statin

PLANET I 2006 and PLANET II 2006 compared rosuvastatin and atorvastatin

IDEAL 2004 compared simvastatin with atorvastatin

Abe 2015 compared rosuvastatin with pitavastatin

Ikeda 2012 compared pravastatin with rosuvastatin

Kimura 2012 compared pitavastatin with pravastatin

SAGE 2004 compared atorvastatin with pravastatin.

Sample sizes ranged from 28 to 3107 participants. The median follow‐up was 12 months (range 12 to 57.6 months). Baseline LDL cholesterol levels ranged from 123.6 to 150.8 mg/dL (3.20 to 3.90 mmol/L). Meta‐analysis was not possible because three or more studies were not available for each comparison.

Excluded studies

See Excluded studies.

Thirty‐two studies did not meet our eligibility criteria for the following reasons.

Wrong intervention (11 studies): did not compare a statin with placebo or standard of care without a statin (Almquist 2012; IMPROVE‐IT 2008; Ishimitsu 2014; Kouvelos 2013; NCT03543774; Suzuki 2013a; UK‐HARP‐II 2006; Weinstein 2013; Yasmeen 2015; Yasuda 2010; Zinellu 2012)

No comparator: one study (ESTABLISH 2004)

Wrong study design: three studies (Mose 2014a; Mose 2014b; Siddiqi 2011)

Wrong population: eight studies (Almukhtar 2021; Fotso 2021; Mackie 2008; Mohammadi 2023; PACTR202110707328144; Vasin 2021; Watanabe 2022; Yen 2022)

Unclear duration or less than eight weeks: nine studies (Dogra 2005; Dogra 2007; Golper 1987; Golper 1989; Ott 2008; Paulsen 2010; Schmieder 2003; Torraca 2006; Van Dijk 2001).

Risk of bias in included studies

Seven studies comparing statins with placebo or no treatment were conducted according to published protocols, outcomes were adjudicated by a committee, specified outcomes were reported, and analyses were conducted using intention‐to‐treat methods (4S 1993; HPS 2002; JUPITER 2007; PPP 1992; PREVEND IT 2000; SHARP 2010; UK‐HARP‐I 2005). In placebo or no treatment‐controlled studies, adverse events were reported in 33 studies (63%) and systematically evaluated in 17 studies (33%). See Included studies for detailed information on study risk of bias assessment.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Random sequence generation was low risk in 15 of the included studies, and the remaining 48 studies were judged to have an unclear risk of bias.

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment was low risk in 19 studies, and the remaining 44 studies were judged to have an unclear risk of bias.

In studies that examined the primary outcomes, six of 17 studies were low risk for random sequence generation, and nine of 17 were low risk for allocation concealment.

Blinding

Performance bias

Participants and personnel were blinded in 27 studies and considered low risk, and 24 studies were open‐label and hence high risk, with the remaining 12 studies did not report blinding and were judged to have an unclear risk of bias.

Detection bias

Sixteen blinded outcome assessors and four studies were high risk with no blinding of outcome assessors. The remaining 43 studies were judged to have an unclear risk of bias.

In studies that reported the primary outcome, nine of 17 studies were blinded study participants and personnel, and outcome assessors.

Incomplete outcome data

Completeness of outcome reporting was applied in 26 of the included studies, and 18 included studies exhibited a high risk of incomplete outcome reporting. The remaining 19 studies did not provide sufficient information to permit judgement and were judged to have an unclear risk of bias. Ten of the 17 studies that reported the primary outcomes exhibited a low risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

Selective outcome reporting occurred in four studies, and only four studies exhibited a low risk of selective outcome reporting. The remaining 55 studies had unclear reporting, with studies not reporting a protocol or clinical registry number. Only two studies that reported the primary outcomes of the review exhibited a low risk of selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

The risk of bias due to sources of funding was high in 14 studies, 21 studies exhibited a low risk of any other bias, while in 28 studies the risk of bias was unclear. Nine studies that reported the primary outcomes of the review exhibited a low risk for other potential sources of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Statin therapy versus placebo

The main findings of the analysis are presented in Table 1.

Primary outcomes

Compared to placebo, statin therapy reduces major cardiovascular events (Analysis 1.1 (14 studies, 36,156 participants): RR 0.72, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.79; I² = 39%; high certainty evidence) and death (Analysis 1.2 (13 studies, 34,978 participants): RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.96; I² = 53%; high certainty evidence).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1: Major cardiovascular events

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2: Death

Statins had uncertain effects on rhabdomyolysis due to study limitations and very serious imprecision (Analysis 1.3 (2 studies, 2618 participants): RR 3.07, 95% CI 0.13 to 75.37; very low certainty).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3: Rhabdomyolysis

Secondary outcomes

Cardiovascular endpoints

Compared to placebo, statin therapy probably reduces cardiovascular death (Analysis 1.4 (8 studies, 19,112 participants): RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.87; I² = 0; moderate certainty evidence) and MI (Analysis 1.5 (10 studies, 9475 participants): RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.73; I² = 0%; moderate certainty evidence).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4: Cardiovascular death

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 5: Myocardial infarction

Statin therapy probably has little or no effect on stroke (Analysis 1.6 (7 studies, 9115 participants): RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.37 to 1.08; I² = 39%; moderate certainty evidence) but probably decreases revascularisation procedures (Analysis 1.7 (3 studies, 4156): RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.47 to 0.82; I² = 0%; moderate certainty evidence), and may have no difference on hospitalisation due to heart failure (Analysis 1.8 (1 study, 579 participants): RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.37, to 1.32; low certainty evidence).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 6: Stroke

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 7: Revascularisation procedure

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 8: Hospitilsation due to heart failure

Kidney endpoints

Compared to placebo, statin therapy probably has no protective kidney effect with little or no effect on kidney failure (Analysis 1.9 (3 studies, 6704 participants): RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.05, I² = 0%; moderate certainty evidence), and doubling of SCr (Analysis 1.10 (1 study, 6245 participants): RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.02; moderate certainty evidence).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 9: Kidney failure

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 10: Doubling serum creatinine

Statin therapy probably improves kidney function (CrCl or eGFR) (Analysis 1.11 (18 studies, 4213 participants): MD 1.83, 95% CI 0.27 to 3.39 mL/min; I² = 17%; moderate certainty evidence). No difference was found with the use of measured CrCl compared to eGFR (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 3.11, df = 1 (P = 0.08), I² = 67.8%).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 11: End of treatment kidney function

Compared to placebo, statin therapy may lower proteinuria (Analysis 1.12 (7 studies, 356 participants): MD ‐0.47 g/24 hours, 95% CI ‐0.75 to ‐0.19; I² = 81%; low certainty evidence) with substantial heterogeneity.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 12: End of treatment proteinuria

Safety endpoints

Statin therapy may have little to no effect on elevated liver enzymes (Analysis 1.13 (7 studies, 7991 participants): RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.39 to 1.50; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence), withdrawal due to adverse events (Analysis 1.14 (13 studies, 4219 participants): RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.48; I² = 37%; low certainty evidence), cancer (Analysis 1.15 (2 studies, 5581 participants): RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.30; I² = 0%; low certainty evidence), and onset of diabetes (Analysis 1.16) (1 study, 3267 participants): RR 1.03, 95%CI 0.71 to 1.50; low certainty evidence).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 13: Elevated liver enzymes

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 14: Withdrawal due to adverse events

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 15: Cancer

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 16: Onset of diabetes

Compared to placebo, the effect of statin therapy on elevated creatinine kinase was unclear because of serious study limitations and very serious imprecision (Analysis 1.17 (7 studies, 4514 participants): RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.20 to 3.48; I2 = 0%; very low certainty evidence).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 17: Elevated creatine kinase

Fatigue, life participation, and memory loss were not reported by any of the included studies.

Lipid endpoints

Statins compared to placebo probably lowers total serum cholesterol (Analysis 1.18 (27 studies, 2234 participants): MD ‐50.26 mg/dL, 95%CI ‐64.34 to ‐36.17 mg/dL (MD ‐1.3 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐1.67 to ‐0.97 mmol/L); I² = 96%; moderate certainty evidence), may decrease LDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.19 (24 studies, 2183 participants): MD ‐43.84 mg/dL, 95%CI ‐52.56 to ‐35.12 mg/dL (MD ‐1.14 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐1.37 to 0.91 mmol/L); I² = 92%; low certainty evidence) and triglycerides (Analysis 1.20 (20 studies, 1186 participants): MD ‐26.02 mg/dL, 95%CI ‐40.99 to ‐11.06 mg/dL (MD ‐0.29 mmol/L, 95% CI ‐0.45 to ‐1.22 mmol/L); I² = 82%; low certainty evidence), and may increase HDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.21 (22 studies, 1374 participants): MD 2.92 mg/dL, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 5.88 mg/dL (MD 0.08 mmol/L, 95% CI 0.0001 to 0.15 mmol/L); I² = 81%; low certainty evidence). Analyses of treatment effects on serum lipids showed evidence for substantial heterogeneity (I² > 80%) for all outcomes.

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 18: Total cholesterol

1.19. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 19: LDL cholesterol

1.20. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 20: Triglycerides

1.21. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 21: HDL cholesterol

No other secondary outcomes were reported in the included studies.

Subgroup analyses

Cardiovascular disease

When we limited analyses to studies in which CVD was an exclusion criterion at baseline, effect modification was not evident for death (Analysis 1.22: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 1.40, df = 1 (P = 0.24), I² = 28.5%). However, the test of subgroup differences indicated potential effect modification for major cardiovascular events, but it was considered not important as the direction of the effect estimates were in the same direction, indicating a benefit of therapy and cross‐over of the 95% CIs (Analysis 1.23: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 2.71, df = 1 (P = 0.10), I² = 63.0%).

1.22. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 22: Subgroup analysis (cardiovascular disease): death

1.23. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 23: Subgroup analysis (cardiovascular disease): major cardiovascular events

Statin dose

When comparing < 20 mg/day simvastatin equivalent with ≥ 20 mg/day simvastatin equivalent, effect modification was evident for major cardiovascular events (Analysis 1.24: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 10.27, df = 1 (P = 0.001), I² = 90.3%) but was not important as the effect estimates were in the same direction and overlap of the 95% CIs. Test for subgroup differences found no evidence of effect modification for statin dose for the outcomes of death (Analysis 1.25), withdrawal due to adverse effects (Analysis 1.26), total cholesterol (Analysis 1.27), LDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.28), HDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.29), or triglycerides (Analysis 1.30).

1.24. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 24: Subgroup analysis (statin dose): major cardiovascular death

1.25. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 25: Subgroup analysis (statin dose): death

1.26. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 26: Subgroup analysis (statin dose): withdrawal due to adverse events

1.27. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 27: Subgroup analysis (statin dose): total cholesterol

1.28. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 28: Subgroup analysis (statin dose): LDL cholesterol

1.29. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 29: Subgroup analysis (statin dose): HDL cholesterol

1.30. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 30: Subgroup analysis (statin dose): triglycerides

Age

Comparing age (< 55 years versus ≥ 55 years), a test of subgroup difference was significant for total cholesterol (Analysis 1.31: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 2.91, df = 1 (P = 0.09), I² = 65.6%). However, effect modification was not considered important because the subgroup effect estimates were in the same direction and overlap of the 95% CIs. Other outcomes did not demonstrate any effect modification (withdrawal due to adverse effects (Analysis 1.32), LDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.33), HDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.34), or triglycerides (Analysis 1.35)).

1.31. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 31: Subgroup analysis (age): total cholesterol

1.32. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 32: Subgroup analysis (age): withdrawal due to adverse events

1.33. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 33: Subgroup analysis (age): LDL cholesterol

1.34. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 34: Subgroup analysis (age): HDL cholesterol

1.35. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 35: Subgroup analysis (age): triglycerides

Diabetes mellitus

Effect modification was examined for DM (< 20% versus ≥ 20%) and was evident for withdrawal due to adverse events (Analysis 1.36: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 3.60, df = 1 (P = 0.06), I² = 72.2%) but not for death (Analysis 1.37), major cardiovascular death (Analysis 1.38), total cholesterol (Analysis 1.39), LDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.40) HDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.41), or triglycerides (Analysis 1.42).

1.36. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 36: Subgroup analysis (diabetes mellitus): withdrawal due to adverse events

1.37. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 37: Subgroup analysis (diabetes mellitus): death

1.38. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 38: Subgroup analysis (diabetes mellitus): major cardiovascular death

1.39. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 39: Subgroup analysis (diabetes mellitus): total cholesterol

1.40. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 40: Subgroup analysis (diabetes mellitus): LDL cholesterol

1.41. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 41: Subgroup analysis (diabetes mellitus): HDL cholesterol

1.42. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 42: Subgroup analysis (diabetes mellitus): triglycerides

Baseline cholesterol

When baseline cholesterol at study entry was ≥ 230 mg/dL compared to < 230 mg/dL, test for subgroup differences were found for the outcomes, total cholesterol (Analysis 1.43: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 4.47, df = 1 (P = 0.03), I² = 77.6%) and LDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.44: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 10.02, df = 1 (P = 0.002), I² = 90.0%). The subgroup differences were not considered important because the subgroups are in the same direction and the 95% CI overlap. For the outcomes of withdrawal due to adverse events (Analysis 1.45), HDL cholesterol (Analysis 1.46), and triglycerides (Analysis 1.47), no effect modification was evident.

1.43. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 43: Subgroup analysis (baseline cholesterol): total cholesterol

1.44. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 44: Subgroup analysis (baseline cholesterol): LDL cholesterol

1.45. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 45: Subgroup analysis (baseline cholesterol): withdrawal due to adverse events

1.46. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 46: Subgroup analysis (baseline cholesterol): HDL cholesterol

1.47. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 47: Subgroup analysis (baseline cholesterol): triglycerides

Allocation concealment

We assessed if allocation concealment resulted in effect modification and found that for the outcome of death, a test of subgroup differences was significant (Analysis 1.48: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 5.70, df = 1 (P = 0.02), I² = 82.5%). Studies with high or unclear risk of bias indicated little to no effect (5 studies, 2838 participants: RR 0.98 95% CI 0.82 to 1.16), while studies with appropriate allocation concealment demonstrated a benefit of statin therapy (8 studies, 32,142 participants: RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.84). Furthermore, subgroup differences were demonstrated in total cholesterol (Analysis 1.49: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 4.83, df = 1 (P = 0.03), I² = 79.3%), but the subgroup effect estimates are in the same direction and the 95% CI overlapped and hence considered not important. No effect modification was evident for major cardiovascular events (Analysis 1.50) and triglycerides (Analysis 1.51).

1.48. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 48: Subgroup analysis (allocation concealment): death

1.49. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 49: Subgroup analysis (allocation concealment): total cholesterol

1.50. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 50: Subgroup analysis (allocation concealment): major cardiovascular events

1.51. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 51: Subgroup analysis (allocation concealment): triglycerides

Baseline kidney function

A post hoc analysis was undertaken to examine the influence of baseline kidney function on the outcome end of treatment kidney function. We found that there was no effect modification evident (Analysis 1.52: test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.07, df = 1 (P = 0.79), I² = 0%). Studies with lower kidney function at baseline (< 55 mL/min/1.73 m2)demonstrated little or no effect on (5 studies, 3207 participants: MD 1.56 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI ‐3.02 to 6.15), but studies with higher kidney function at baseline (≥ 55 mL/min/1.73 m2)indicated that there might be a small increase in kidney function at the end of treatment (12 studies, 963 participants: MD 2.24 mL/min/1.73 m2, 95% CI 0.30 to 4.17).

1.52. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 52: Subgroup analysis (kidney function): end of treatment kidney function

Sensitivity analyses

We excluded SHARP 2010 from the meta‐analysis for primary outcomes because it added ezetimibe to statin therapy. We found no differences for major cardiovascular events and death. The summary treatment estimates were essentially unchanged (Analysis 1.53: RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.77) (Analysis 1.54: RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.90).

1.53. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 53: Sensitivity analysis (excluding SHARP): major cardiovascular events

1.54. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 54: Sensitivity analysis (excluding SHARP): death

Excluding studies with industry funding, we found that in studies with non‐industry funding or where funding was not reported, major cardiovascular events were decreased with statin therapy compared to placebo (Analysis 1.55), similar to the meta‐analysis with all included studies (Analysis 1.1). However, for death, studies with no industry funding or where funding was not reported, statins compared to placebo made no difference (Analysis 1.56), unlike the full analysis that found statins decreased death compared to placebo. Although the effect estimates direction indicates a decrease in death, the exclusion of studies may decrease the precision of the finding, and hence the finding should be interpreted with caution. There was insufficient data to examine the effect on rhabdomyolysis.

1.55. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 55: Sensitivity analysis (funding): major cardiovascular events

1.56. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Statins versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 56: Sensitivity analysis (funding): death

Excluding large studies from the analysis (N > 3500) did not change the direction and size of the effect estimates for the primary outcomes, major cardiovascular events and death (data not shown).

The following sensitivity analyses were considered but not undertaken.

Repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies (due to limited unpublished studies)

Repeating analysis taking account of risk of bias (due to limited low risk of bias studies)

Repeating the analysis using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, and country.

Meta‐regression

Considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 53%) was found for the primary outcome of death. Subgroup analyses to explore heterogeneity among the studies found that kidney function at baseline accounted for 100% of the observed heterogeneity in the meta‐analysis for death. Additionally, subgroup analysis indicated that baseline kidney function (98.8% of heterogeneity explained), the proportion with diabetes (99.6%), and adequacy of allocation concealment (100%) modified the observed risks of withdrawal due to adverse events. These findings were exploratory and should be interpreted with caution.

Assessment of publication bias

Publication bias was assessed for all outcomes listed in Table 1, which included more than 10 studies. The funnel plots for the outcomes of major cardiovascular events (Figure 4), death (Figure 5), and MI (Figure 6) were symmetrical and indicated little concern regarding small study effects. No further statistical testing was undertaken to assess publication bias for these outcomes.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Statins versus placebo or no treatment, outcome: 1.1 Major cardiovascular events.

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Statins versus placebo or no treatment, outcome: 1.2 Death.

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Statins versus placebo or no treatment, outcome: 1.5 Myocardial infarction.

Statin therapy versus different statin therapy

PLANET I 2006 and PLANET II 2006 compared low‐ and high‐dose rosuvastatin and atorvastatin and found both therapies were well tolerated, with few events to determine the difference between primary outcome death and secondary outcomes, doubling of SCr and AKI.

IDEAL 2004 compared simvastatin with atorvastatin, Abe 2015 compared rosuvastatin with pitavastatin, Ikeda 2012 compared pravastatin with rosuvastatin, Kimura 2012 compared pitavastatin with pravastatin, and SAGE 2004 compared atorvastatin with pravastatin. Sample sizes ranged from 28 to 3107 participants. The median follow‐up was 12 months (range 12 to 58.8 months). Baseline LDL cholesterol levels ranged from 3.05 to 3.9 mmol/L. Meta‐analysis was not possible because there was insufficient data for each comparison. It was unclear which statin therapy was the most effective and safe from these studies. IDEAL 2004 reported the primary outcome of major cardiovascular events,

Secondary outcomes reported in the identified studies included LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, triglyceride, MDA‐LDL, non‐HDL cholesterol, SCr, cystine C, urinary albumin/creatinine ratio, hs‐CRP, HbA1c, eGFR, adverse events, the cost to lower LDL cholesterol by 10 mg/dL, onset of diabetes, time to first occurrence of a major coronary event, any chronic heart disease event, any cardiovascular event, urinary protein excretion, kidney failure, AKI, and serum uric acid.

High versus low dose statin

PANDA 2011 and TNT 2004 compared two doses of atorvastatin, and PLANET I 2006 and PLANET II 2006 compared low‐ and high‐dose rosuvastatin.

Primary outcomes

High‐dose statin compared to low‐dose statin may have little or no effect on major cardiovascular events (Analysis 2.1 (2 studies, 3226 participants): RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.25 to 5.55; I2 = 59%; low certainty evidence), and death (Analysis 2.2 (3 studies, 3465 participants): RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.29 to 3.83; I2 = 56%; low certainty evidence). No events of rhabdomyolysis were reported.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: High dose versus low dose statin, Outcome 1: Major cardiovascular events

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: High dose versus low dose statin, Outcome 2: Death

Secondary outcomes

TNT 2004 (3107 participants) reported high‐dose statin may decrease stroke (Analysis 2.3: RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.89) and hospitalisation due to heart failure (Analysis 2.4: RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.77; low certainty evidence) compared to low‐dose statin. High‐dose statin, compared to low‐dose statin, probably has little or no effect on serious adverse events (Analysis 2.5 (2 studies, 358 participants): RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.72; I2 = 0%; moderate certainty evidence), but there was limited data on AKI and doubling of SCr to determine if high‐dose statin made a difference. However, high‐dose statins may increase elevated liver enzymes (Analysis 2.6: RR 20.67, 95% CI 2.79 to 153.14; low certainty evidence) compared to low‐dose statins. PLANET I 2006 (223 participants) reported high‐ versus low‐dose rosuvastatin may improve change in total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol at 12 months, but there was no difference in change in HDL cholesterol and change in triglycerides. No other secondary outcomes were reported in the included studies.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: High dose versus low dose statin, Outcome 3: Stroke

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: High dose versus low dose statin, Outcome 4: Hospitilisation due to heart failure

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: High dose versus low dose statin, Outcome 5: Serious adverse events

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: High dose versus low dose statin, Outcome 6: Elevated liver enzyme

Continuous release versus intermittent release statin

Yi 2014 (122 participants) compared continuous‐release to intermittent‐release statin (20 mg/day). No primary outcomes of major cardiovascular events, death, or rhabdomyolysis were reported. There were few withdrawals due to adverse events in the study. Continuous‐release versus intermittent‐release statin may have little or no effect on total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol, but may increase triglycerides. No other secondary outcomes were reported.

There was insufficient data to perform a meta‐analysis for this comparison.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This update confirmed findings from the previous 2014 review (Palmer 2014). Compared to placebo, statins reduced the risk of death by 20% and major cardiovascular events by 28% in people with CKD not needing dialysis. Statins probably reduce the risk of MI by nearly half, but the effects on stroke and hospitalisation due to heart failure remain uncertain. Statins decreased death, major cardiovascular events, and MI in people with (secondary prevention) and without CVD (primary prevention).

Considering the estimated baseline risk of people with CKD not needing dialysis (Table 1), statins given to 1000 people with CKD for one year might be expected to prevent 32 major cardiovascular events, 10 deaths from any cause, and seven non‐fatal or fatal MIs. There was limited reporting of adverse effects of statins in people with CKD not needing dialysis. Withdrawal due to adverse effects probably occurs more frequently among those with lower kidney function or pre‐existing diabetes, suggesting that these people may be more at risk of treatment‐related toxicity. However, there was uncertainty regarding the effect on rhabdomyolysis due to the few events reported and no reporting of patient‐important outcomes such as fatigue, life participation, and memory loss.

Data comparing different statins were sparse in patients with CKD. One study reported a benefit of high‐dose statins in reducing stroke and heart failure events compared to low‐dose statins, but a further examination of this finding is required. Additionally, there was limited reporting of safety in studies comparing high‐ versus low‐dose statins.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Based on current evidence, statins probably make little to no difference to CKD progression, as treatment effects were similar to placebo with more than 2000 events. However, statins probably have a slight benefit on kidney function and may reduce proteinuria due to the pleiotropic effects of statins, but the clinical importance of these outcomes is unclear. Nearly two‐thirds of the included studies did not systematically evaluate and report adverse events, such as rhabdomyolysis and elevated liver enzymes. There was no reporting of patient‐important outcomes, such as fatigue, memory loss, and life participation.

SHARP 2010 assessed ezetimibe (a drug that lowers cholesterol absorption in the intestine) combined with simvastatin. There was insufficient data to determine if treatment effects differed between combination therapy and treatment with a statin alone. There was limited data that could be used to determine the most effective and safe type of statin or dose of statin in the CKD population. Furthermore, it was unclear if treatment benefits for statins depended on treatment‐related reductions in serum cholesterol or by another mechanism of action, as there were insufficient number of studies that reported both cardiovascular and death outcomes and changes in cholesterol levels with treatment.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of the evidence in clinical outcomes (death, cardiovascular events, kidney failure) for shared decision‐making for statin with or without ezetimibe is high to moderate certainty evidence. However, the data for patient‐important outcomes, such as rhabdomyolysis is very low or not reported for fatigue, life participation and memory loss.

Current data on the effects of statins in people with earlier stages of kidney disease relating to the primary outcomes of death and cardiovascular events were derived from post hoc subgroup analyses from major studies in larger populations (4S 1993; AFCAPS/TexCAPS 1997; ALLIANCE 2000; CARDS 2003; HPS 2002; JUPITER 2007; LIPS 2001; MEGA 2004; PPP 1992; PREVEND IT 2000; SHARP 2010). Data for treatment effects in people with CKD derived from post hoc analyses of larger studies may be less reliable (Boutron 2010). The heterogeneity observed in our review was not explained by prespecified or post hoc studies of people with CKD, as the effects estimates in all studies were similar.

Potential biases in the review process

This review is reported using standardised Cochrane methods and the PRISMA checklist (Liberati 2009). It includes a highly sensitive electronic search of the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant's Specialised Registry of Studies, designed by an Information Specialist. Despite applying these best practice approaches, potential biases may exist in the review process. Incomplete reporting of outcomes in the identified studies limited the power to detect differences among interventions for important outcomes. For example, data for treatment effects on stroke and hospitalisation due to heart failure suggest a potential for benefit, but the small number of events resulted in imprecision in the effect estimate. This incomplete reporting of outcomes may also limit the statistical power to detect heterogeneity. However, the analysis of most outcomes exhibits low to moderate heterogeneity, indicating that the meta‐analysis was appropriate. Additionally, we could not include data for people with CKD not on dialysis from Stegmayr 2005 for death and cardiovascular death. Reported data for these outcomes combined results for people on dialysis with those at earlier stages of kidney disease not on dialysis; separate unpublished data for earlier stages of kidney disease were not available.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This update confirmed our earlier review findings that statins reduce serious cardiovascular events and death in people with CKD not requiring dialysis (Palmer 2014). The finding that statins proportionally reduce cardiovascular death by 20% is similar to the prospective meta‐analysis in broader populations of people who had or were at risk for CVD, which showed that statins lowered lipids to reduce coronary‐related death at a rate of 20% (Baigent 2005). People with CKD risk cardiovascular events equivalent to those with existing coronary artery disease (Foley 1998). The absolute benefits of statins in people with CKD are similar to people with a 20% or more 10‐year absolute cardiovascular risk, for whom statins are recommended (NICE 2014).

We also found that statins reduced death by approximately 28%, similar to the 10% proportional reduction in broader populations (Baigent 2005). The inclusion of studies conducted in people with CKD without clinically evident CVD in this review (Abe 2011c; Masajtis‐Zagajewska 2018; Ohsawa 2015) reaffirmed the previous finding that statins have a role in the primary prevention of death and major cardiovascular events (Palmer 2014). The beneficial effect of statins on cardiovascular end‐points observed in our review may be potentially explained by either cholesterol‐dependent or cholesterol‐independent effects or both. In addition to the well‐documented association between cholesterol‐lowering and cardiovascular risk reduction in non‐CKD populations (Baigent 2005), statins may modulate cardiovascular risk by decreasing inflammation, enhancing endothelial function, inhibiting smooth muscle proliferation, exerting direct anti‐thrombotic properties and stabilising pre‐existing atherosclerotic plaque (Kinlay 2003; Robinson 2005; Sotiriou 2000). Similar mechanisms may underpin the beneficial actions of statins on the progression of kidney disease, although other cholesterol‐independent renoprotective actions such as inhibition of renal cell proliferation, anti‐fibrotic effects, suppression of macrophage recruitment, anti‐oxidation, and down‐regulation of inflammatory cytokines, may also contribute (Campese 2005; Keane 2000).

Notably, the finding that statins significantly reduce adverse cardiovascular outcomes in people with earlier stages of CKD contrasts with a similar systematic review and meta‐analysis we have conducted of studies in people with advanced kidney disease on dialysis (Palmer 2013). Statin therapy in people with advanced CKD on dialysis has little or no effect on major cardiovascular events (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.03), death (any cause) (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.02), cardiovascular death (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.06), or MI (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.07) with uncertain effects on liver or muscle function or cancer, despite a similar reduction in cholesterol levels. Similarly, an individual patient‐level meta‐analysis of 28 RCTs found that the effects of statins decreased with declining kidney function, with patients on dialysis receiving little to no benefit from statins (Herrington 2016).

The KDIGO Lipids in CKD guideline recommends statins for patients 50 years or older and an eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 "For patients 50 years of age and older and eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 not needing dialysis, a statin with or without ezetimibe" (KDIGO 2013). Additionally, CARI Guidelines (CARI 2013) recommend using statins with or without ezetimibe in patients with early CKD (stages 1 to 3) to reduce the risk of atherosclerotic disease. Our analysis confirms the benefits of statins in people with CKD (including primary prevention of death and cardiovascular events) and supports the present guidelines. However, there is limited data on the incremental benefit of ezetimibe combined with statins in people with CKD.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Moderate‐to‐high‐quality evidence currently supports the widespread use of statins for people with CKD not on dialysis to prevent death and cardiovascular events, including people without existing CVD. Statins reduce death and cardiovascular events, including MI, although effects on the risk of stroke were less certain. Treating 1000 people with CKD not on dialysis may prevent 32 major cardiovascular events and 10 deaths over one year. Statins have uncertain effects on the progression of CKD and cannot be recommended to slow the progression of CKD. Currently, the toxicity of statins for people with CKD is poorly characterised in studies, and this needs to be acknowledged when commencing treatment.

Implications for research.

Available data confirms the benefit of statins in reducing lipid levels and improving death and cardiovascular death in people with CKD not needing dialysis. Future research, including post‐marketing surveillance, is required to monitor the safety of statins in people with CKD, with a focus on risks of muscle or liver damage associated with longer‐term treatment. A co‐ordinated approach to post‐marketing surveillance might be considered.