Abstract

Aim:

Preventing unnecessarily long durations of antibiotic therapy is a key opportunity to reduce antibiotic overuse in children 2 years of age and older with acute otitis media (AOM). Pragmatic interventions to reduce durations of therapy that can be effectively scaled and sustained are urgently needed. This study aims to fill this gap by evaluating the effectiveness and implementation outcomes of two low-cost interventions of differing intensities to increase guideline-concordant antibiotic durations in children with AOM.

Methods:

The higher intensity intervention will consist of clinician education regarding guideline-recommended short durations of antibiotic therapy; electronic health record (EHR) prescription field changes to promote prescribing of recommended short durations; and individualized clinician audit and feedback on adherence to recommended short durations of therapy in comparison to peers, while the lower intensity intervention will consist only of clinician education and EHR changes. We will explore the differences in implementation effectiveness by patient population served, clinician type, clinical setting and organization as well as intervention type. The fidelity, feasibility, acceptability and perceived appropriateness of the interventions among different clinician types, patient populations, clinical settings and intervention type will be compared. We will also conduct formative qualitative interviews with clinicians and administrators and focus groups with parents of patients to further inform the interventions and study. The formative evaluation will take place over 1.5 years, the interventions will be implemented over 2 years and evaluation of the interventions will take place over 1.5 years.

Discussion:

The results of this study will provide a framework for other healthcare systems to address the widespread problem of excessive durations of therapy for AOM and inform national antibiotic stewardship policy development.

Clinical Trial Registration: NCT05608993 (ClinicalTrials.gov)

Keywords: acute otitis media, antibiotic stewardship, interventions, outcomes

Plain language summary

What is this article about?

Ear infections are the most common reason children are prescribed antibiotics. National guidelines recommend 5–7 days of antibiotics for most children over 2 years of age, but over 90% of children are prescribed durations over 5–7 days, resulting in unnecessary exposure to antibiotics. This article details the protocol for a study that evaluates two interventions that aim to reduce antibiotic overuse in children 2 years of age and older with ear infections. This study takes place in 35 clinics at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, TN, USA and Washington University Medical Center in MO, USA.

How will the results of this study be used?

The results of this study will provide a framework for other healthcare systems to address the widespread problem of longer than necessary durations of antibiotic treatment and help inform the development of policies to guide how clinicians prescribe antibiotics for childhood ear infections.

Tweetable abstract

This study evaluates interventions to reduce antibiotic overuse in children with ear infections. It will provide a framework to address the problem of excessive durations of therapy and inform stewardship policy.

Background

Acute otitis media (AOM) is the most common indication for antibiotics in children, affecting over 5 million children and resulting in greater than 10 million antibiotic prescriptions annually in USA [1–3]. By 3 years of age, 60% of children will have had AOM at least once [1]. For most children 2 years of age and older, 5–7-day antibiotic durations, rather than conventional 10-day durations, have been shown to be sufficient for treating AOM [4]. Thus, national guidelines recommend 5–7-day antibiotic durations for non-severe AOM in this age group [5]. Despite these recommendations, more than 90% of children 2 years of age and older are prescribed longer durations [6–8] which results in substantial unnecessary antibiotic exposure. It is estimated that more than 40% of all antibiotic-days prescribed for AOM are unnecessary [7]. This may harm children by causing adverse drug events (ADE) [9], selecting for antibiotic-resistant bacteria [10], and increasing risk for Clostridioides difficile infection [11]. Antibiotic exposure is also associated with the development of chronic diseases later in life [12–14].

One method to reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure is to use the shortest duration of antibiotics needed to effectively treat an infection. In a recent single-center study to promote use of the shortest guideline-recommended duration of therapy for AOM, an intervention that included clinician education, individualized clinician audit and feedback with peer comparison, and electronic health record (EHR) changes was associated with a 76% absolute increase in prescribing of the recommended antibiotic duration, while a lower intensity intervention with only EHR changes increased prescribing of the recommended duration by 50% (p < 0.01) [15]. A definitive study is needed to make appropriate recommendations on which intervention to implement in diverse settings while minimizing resource utilization and to compare implementation outcomes to effectively scale the interventions. This study will evaluate and compare effectiveness and implementation outcomes of two low-cost pragmatic interventions with differing intensities using mixed methods analyses and the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework [16,17]. Additionally, the Practical Implementation Sustainability Model (PRISM) [18] will be used to assess multilevel relevant contextual factors to prescribing shorter antibiotic durations for AOM in children 2 years of age and older to help inform intervention and implementation strategy adaptations.

Methods

Overview of study design

This is a pragmatic, cluster randomized clinical trial. We will compare the effectiveness of two interventions to increase prescribing of guideline-concordant durations of antibiotic therapy for children with AOM. The study uses a type two hybrid implementation-effectiveness design [19] to evaluate effectiveness and implementation outcomes using PRISM and RE-AIM. Adaptations will be documented using the iterative RE-AIM method throughout the implementation [20]. Randomization will be clustered at the clinic-level using covariate constrained randomization to achieve balance between the arms on site- and patient-level characteristics. The formative evaluation will take place over 1.5 years, the interventions will be implemented over 2 years, and evaluation of the interventions will take place over 1.5 years. The primary outcome is the proportion of children 2 years or older treated with antibiotics for AOM who are prescribed a 5-day duration of therapy.

Participating clinics will be randomly assigned to a higher intensity or lower intensity intervention. The interventions were modeled after a prior single-center study that compared the effectiveness of interventions of differing intensity in pediatric clinics within a federally qualified health center system (FQHC) in Denver, CO, USA [15]. Both interventions were found to significantly increase adherence to institutional guidance for short (5-day) durations of antibiotics for AOM. However, a higher intensity intervention led to a greater absolute increase in appropriate durations than the lower intensity intervention (76 vs 50% absolute increase, p < 0.001).

Study setting & population

The study will take place in 35 clinics (general pediatric, urgent care, and retail clinics) in the Vanderbilt University Medical Center system and 11 clinics (general pediatric clinics) in the Washington University Medical Center system (Table 1). These clinics serve approximately 15,627 children with AOM annually. The participating clinics were selected to represent a broad range of community-based practice types because more than 40% of children with AOM in the US are cared for in non-primary care locations such as urgent cares and retail clinics [6]. Furthermore, the patient populations from these sites are diverse: 33% are non-white, 8% are Hispanic, 9% have a language preference other than English, and 34% have public insurance or are self-pay. Denver Health and Hospital Authority (DHHA) will lead the implementation of the intervention components at Vanderbilt and Washington University, as the intervention has already been successfully implemented in most DHHA ambulatory care locations.

Table 1. . Characteristics of partner institutes.

| Characteristic | Washington University Medical Center, n (%) |

Vanderbilt University Medical Center, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Practice characteristics | ||

| Practice locations (n) | 11 | 35 |

| Clinicians (n) | 52 | 164 |

| Types of clinical care settings | ||

| Pediatric clinic | 11 | 4 |

| Urgent care | 0 | 17 |

| Retail clinic | 0 | 14 |

| Annual pediatric patient encounters | 158,073 | 156,498 |

| Pediatric patient characteristics | ||

| Age (median, years) | 7.6 | 8.0 |

| Male | 29,072 (51.3) | 35,956 (50.6) |

| Race | ||

| White | 47794 (84.4) | 38,148 (53.6) |

| Black/African–American | 4213 (7.4) | 13,757 (19.2) |

| Other | 4639 (8.2) | 19,744 (27.6) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 1188 (1.2) | 9104 (12.8) |

| Public or self-pay | 7688 (13.6) | 35,767 (50.4) |

| Non-english language preference | 993 (1.7) | 10,650 (15.0) |

| Acute otitis media prescribing | ||

| Annual encounters for AOM in children 2–17 years (inclusive) | 8888 | 6739 |

| Antibiotic prescribed | 7524 (84.6) | 4059 (60.2) |

| Antibiotic duration 5 days† | 168 (2.2) | 42 (1.0) |

| Antibiotic duration 7 days† | 589 (7.8) | 645 (15.9) |

| Antibiotic duration ≥10 days† | 6971 (92.7) | 3263 (80.3) |

Of 2–17-year-old children prescribed an antibiotic.

Formative evaluation of context with PRISM

PRISM [18] will be used to guide the formative implementation evaluation of the interventions. It has demonstrated efficacy in identifying contextual factors to facilitate intervention and dissemination adaptations to prevent program failure and increase program uptake across diverse settings. Such contextual factors – both external and internal – will be assessed in the PRISM domains of organizational perspective; patient perspective; external environment; implementation and sustainability infrastructure; organizational characteristics; and patient characteristics. Using a mixed methods approach during the intervention and implementation refinement phase of the study will help make necessary adaptations to the intervention and guide implementation strategies (Table 2).

Table 2. . Practical robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) components.

| PRISM domain | What are we assessing? | How will data be collected? | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational perspective | • Baseline antibiotic prescribing patterns for AOM • Assessment of current local guidelines for AOM prescribing • Contextual factors that may facilitate/impede shorter duration of antibiotic prescribing • Contextual factors that may facilitate/impede implementation of intervention components • Clinician buy-in for 5 days |

• Key informant interviews • Process mapping interviews • EHR data |

[18] |

| Patient perspective | • Receptiveness to shorter durations of antibiotics for AOM • Contextual factors that may facilitate/impede the acceptance of shorter antibiotics durations for AOM |

• Key informant focus groups | [18] |

| External environment | • Cosmopolitanism • Cost of interventions |

• Key informant interviews • Cost estimates |

|

| Implementation and sustainability infrastructure | • Current resources and resource utilization for AOM management (e.g., EHR tools, education materials) and stewardship • Baseline workflow for AOM • Perceived facilitators/barriers to sustainability |

• Key informant interviews • Process mapping interviews |

|

| Organizational characteristics | • Existing collaborations and information flow between clinics • Administrative support • Shared goals |

• Key informant interviews | |

| Patient characteristics | • Demographics • Urban, suburban, rural designation |

• EHR data collection • Clinic zip codes |

AOM: Acute otitis media; EHR: Electronic health record.

Contextual factors will be assessed at the patient/parent, clinician, clinic, and health systems levels using key informant semi-structured interviews and focus groups, process mapping and EHR data (Table 2). A purposeful sampling of clinical staff (clinicians, administrators) will be recruited to participate in virtual qualitative semi-structured interviews to understand workflow; contextual factors that may facilitate or impede prescription of short antibiotic durations; contextual factors that may facilitate or impede implementation of interventions; and organization culture. A purposeful sampling of parents will be recruited to participate in semi-structured virtual focus groups to understand parent/child level contextual factors around use of short antibiotic durations for AOM and intervention components.

The qualitative research team will analyze data using the Rapid Assessment Process (RAP) [21]. The RAP is an intensive, iterative, team-based approach that provides a framework to efficiently identify a preliminary understanding of a topic to inform design and implementation efforts in applied research activities [21–24].

Finally, to better understand variability in care, assist with setting targets for improvement, and randomize clinics, baseline EHR data will be abstracted to determine baseline antibiotic prescribing patterns and patient-level characteristics.

Intervention components

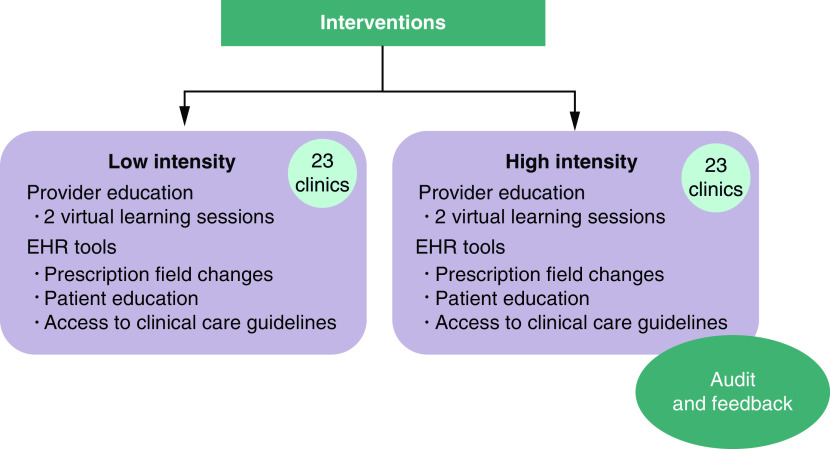

Intervention components in each arm are based on the CDC Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship [2]. In the present trial, the higher intensity intervention is comprised of clinician education regarding the shortest effective duration of antibiotic therapy for AOM; EHR prescription field changes to promote prescribing of recommended short durations; and individualized clinician audit and feedback on adherence to recommended short durations of therapy with comparison to peers. The lower intensity intervention will include only clinician education and the EHR changes (Figure 1). Interventions will be adapted based on the formative evaluation.

Figure 1. . Interventions comparator.

EHR: Electronic health record.

Clinician education

Clinician education will include two one-hour virtual learning lessons. Education will focus on best practices for AOM management including evidence for shorter durations of therapy in children 2 years of age and older, equity in AOM management, and communication with parents using the Dialogue Around Respiratory Treatment (DART) curriculum [12,25]. Based on prior clinician feedback [15] education will be included in both interventions rather than just the higher intensity intervention. Learning sessions will be recorded and continuing medical education (CME) and/or specialty board Maintenance of Certification (MOC) credit will be provided.

EHR changes

All participating clinical sites use a single EHR that can be modified centrally (Epic; WI, USA). The EHR changes will include modifications to prescription fields [15] such as adding a hyperlink to local clinical care guidelines for AOM, ‘help’ text to the prescription to guide real-time prescribing, and changes in the quick-select duration buttons from 10-, 14- and 21-days to 5- and 10-days. Patient education materials will be added to the EHR in languages appropriate for the patient populations (English, Spanish) at a fifth to eighth grade literacy level so that clinicians can add them to the patient after-visit summary.

Audit & feedback reports with peer comparison

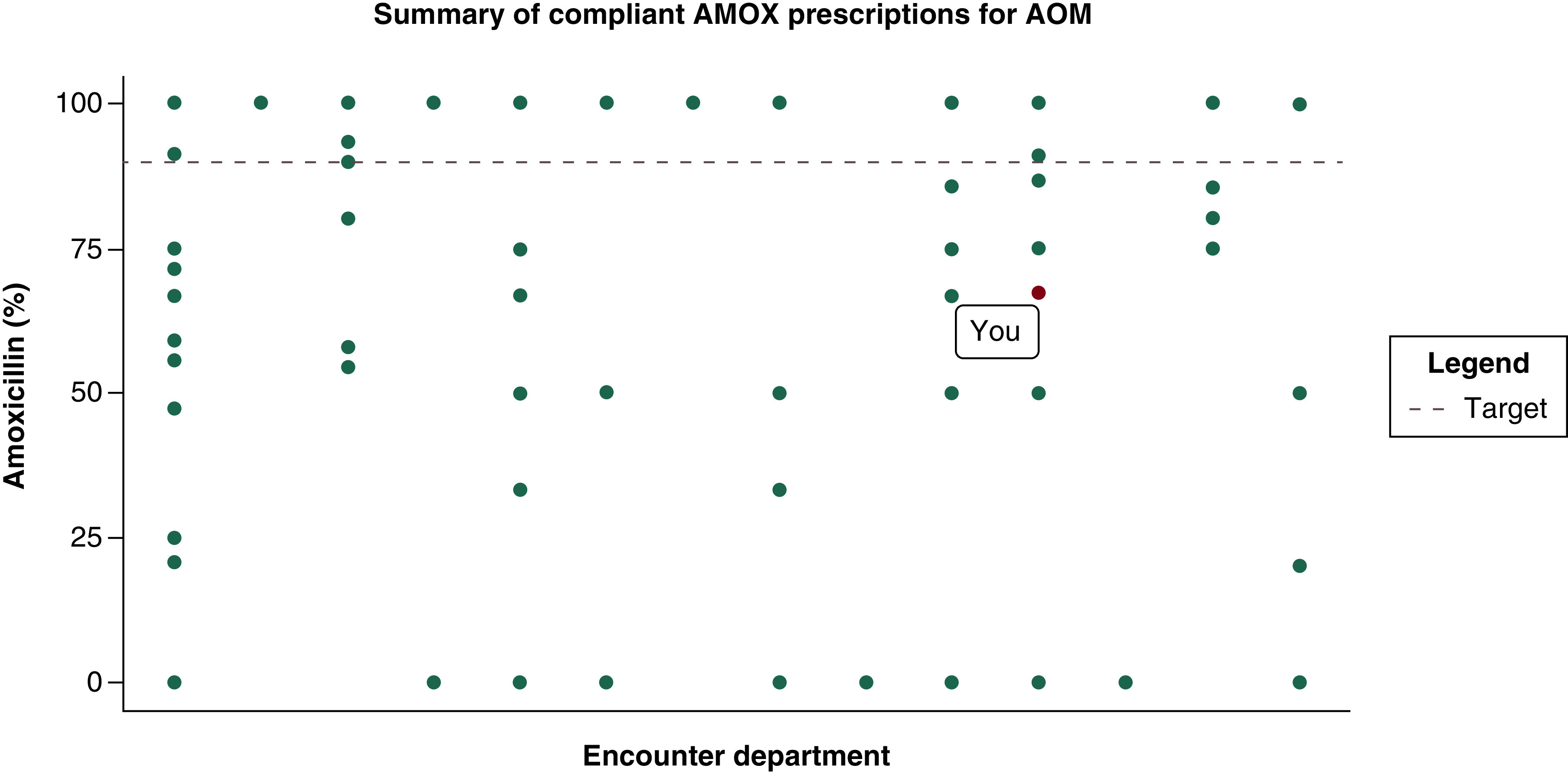

Audit and feedback reports will be created for each clinician in the clinics randomized to the higher intensity intervention. Similar to those previously published [15,26], the reports will show the proportion of that clinician's antibiotic prescriptions for AOM in children ≥2 years old that were for the recommended 5-day duration and the same metric for each peer clinician in their practice (Figure 2). To reduce cost and increase generalizability of the findings, feedback reports will be generated using the Outpatient Automated Stewardship Information System (OASIS©) [27]. OASIS© is a free, open-source method that uses statistical software to automate audit and feedback report creation, distribution and tracks clinician review of reports.

Figure 2. . Example Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship Information System report.

AMOX: Amoxicillin; AOM: Acute otitis media.

Evaluation with RE-AIM including data analytics plan

The RE-AIM framework will guide evaluation using mixed methods to evaluate implementation outcomes (Table 3). Data on participating and non-participating clinics and clinicians will be acquired from each organization to assess and compare the primary and secondary effectiveness outcomes (how many children received short durations and how many had ADEs), adoption outcomes (how many and which types of clinics participated), reach outcomes, implementation outcomes (fidelity, acceptability, appropriateness, time to implementation), reach outcomes (how many and which type of patients were affected), and sustainability outcomes (sustainability, feasibility of implementation in other sites, and costs of the interventions) for each interventions. Finally, the costs of implementation will be assessed.

Table 3. . Reach Effectiveness Adoption Implementation Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework components for evaluation.

| RE-AIM component | Project questions | Outcomes | How will data be obtained and at what intervals? | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R-Reach | • How many patients can be reached by the interventions? | • AOM episodes (n) | • EHR data (baseline, quarterly during intervention, post-intervention) | |

| E-Effectiveness | • Do the interventions increase prescribing of short durations of antibiotics? • How do the interventions impact prescribing for patients of different races, ethnicities, insurance types, and language preferences? • How effective are the intervention in difference clinical settings? |

• Primary: Proportion of antibiotics for AOM that are short course (5 days). • Secondary: Proportion of children experiencing an ADE with short (5 days) vs long durations (>5 days). |

• EHR data (baseline, quarterly during intervention, post-intervention) | |

| A-Adoption | • How many clinics will adopt the interventions? • Do the interventions require adaptations to meet local needs? |

• Number/proportion of eligible clinics that agree to participate • Characteristics of clinics that participate vs clinics that opt not to participate • Number/proportion of enrolled clinics that implement all program components |

• Network data (pre-intervention, post-intervention) • Clinician and administrator surveys (post-intervention) • Key informant qualitative interviews (pre intervention) |

|

| I-Implementation | • Are the interventions fully implemented and how rapidly are interventions implemented? • How many clinicians participate in intervention components? • Do clinicians and administrators think the interventions are acceptable and appropriate? • Are the interventions acceptable to parents? • Are there differences in the acceptability of intervention between parents of different races, ethnicities, insurance types, and language preferences? |

• Implementation of intervention components and time to implementation • Intervention fidelity ○ Education ○ EHR-tools ○ Audit and feedback • Clinician perceptions of component utility, acceptability, and appropriateness • Parent perceptions of short vs long antibiotic durations |

• Stages of Implementation Completeness (SIC) tracking (quarterly through the study) • Attendance at education sessions, meeting board specialty requirements, proportion of AOM episodes where EHR tools were used, proportion of audit and feedback reports read by clinicians- tracked using read receipts (quarterly during intervention and post-intervention) • Clinician and administrator surveys using the AIM and IAM (post intervention). • Focus groups of parents (pre- and post-intervention) |

[28,29] |

| M-Maintenance | • What is the likelihood of sustainability of the interventions? • Do clinicians and administrators think it would be feasible to implement the interventions in other settings? • Could the interventions be implemented in other settings? • What are the health system costs of implementing the interventions? |

• CSAT Sustainability Score • FIM measure • Costs of implementation |

• Clinician and administrator surveys using CSAT and FIM (post-intervention) • COINS method |

[29–31] |

ADE: Adverse drug event; AIM: Acceptability of intervention measure; AOM: Acute otitis media; COINS: Cost of implementation new strategies; CSAT: Clinical Sustainability Assessment Tool; FIM: Feasibility of intervention measure; EHR: Electronic health record; IAM: Intervention appropriate measure.

We will explore the differences in implementation effectiveness by patient population served, clinician type, clinical setting, organization as well as intervention type. The fidelity, acceptability, and perceived appropriateness of the interventions among different clinician types, patient populations, clinical settings and intervention type will be compared.

Stakeholder engagement

We will seek input from key stakeholders to guide this research, increase the likelihood of success of the interventions, and disseminate the trial results. A stakeholder advisory council (SAC) comprised of parents, clinicians, and clinic administrators with representation from both Vanderbilt and Washington Universities will be assembled. The SAC will meet twice in the first year and once annually in the remaining 4 years of the study period. The initial focus will be the development of the components of each intervention arm and implementation strategies with a subsequent focus on interpretation and dissemination of results. A group of national stakeholders from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Pew Charitable Trusts, and the American Academy of Pediatrics will help guide implementation of interventions, evaluation of outcomes and dissemination of findings.

Data collection & statistical analysis

Patient level data

Children aged 2 to 17 years treated for AOM at a participating clinic during the study period will be identified using ICD-10 codes (H65.X, nonsuppurative otitis media; H66.X, suppurative otitis media and unspecified otitis media; H67.X, otitis media in diseases classified elsewhere; H72.X, perforation of tympanic membrane). For each encounter, the following data will be collected: demographic characteristics (age, sex, race, ethnicity, language preference, insurance type), comorbid conditions, vaccination status, visit location, antibiotic prescribed at the index visit and duration of therapy, clinical encounters after the index visit, and antibiotics prescribed within 30 days after the index visits. The baseline (pre-intervention) period of 1 January 2019, through 31 December 2022, was selected to encompass time periods both before and after the emergence of SARS-CoV-2. The duration of the post-intervention implementation period will be 3 years.

Statistical analysis

Baseline patient and practice characteristics will be summarized using descriptive statistics and compared between intervention groups. The primary outcome will be analyzed with a mixed effects logistic regression model, accounting for the hierarchical structure of the data with patients nested within clinics on an intention to treat population. In the main, adjusted analysis, intervention group, period (pre- vs post-intervention), an interaction term between intervention and period, and a priori specified confounding factors (age, race, gender, ethnicity, language preference and insurance type) will be included in the model. In addition, any covariates that appear unbalanced between the study arms in bivariate analysis at p < 0.2, will be included as predictors. As it is possible that clinicians (within clinics) are another source of variation, variance components will also be estimated for clinicians within practices and both random effects will be retained if there is evidence of sufficient variability at both levels. Changes in the proportion of prescriptions will be compared between pre-intervention and intervention periods within and between intervention groups. Comparisons between intervention and period groups will be expressed as proportion differences and odds ratios, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Hypothesis tests will be two-sided with an alpha of 0.05.

Secondary outcomes will be analyzed using linear mixed effects regression for mean days of antibiotics prescribed and mixed effects logistic regression for ADE rates and balance measures (treatment failure and recurrence). Similar random effects will be included accounting for the nested structure of the data. For these analyses, comparisons between and within groups will be expressed as mean differences, difference in proportions, and odds ratios, as appropriate, with 95% CIs.

We will also conduct prespecified, exploratory subgroup analyses to investigate whether age, race, ethnicity, insurance status, clinical care setting, and clinician type modifies the effectiveness of each intervention group in increasing the proportion of short durations of antibiotics. Similar models will be used in evaluating the subgroup analyses on the primary outcome.

Sample size & power

Using feasibility data from Vanderbilt and Washington University, we estimate approximately 23,000 children will be treated for AOM during the study period (11,500 prior to the intervention, 11,500 during the intervention) at each site, or 46,000 total children. Feasibility data also indicate that the proportion of pre-intervention antibiotic prescriptions for 5 days is approximately 2%. If the lower intensity intervention arm increases the proportion to 50%, a 25% absolute difference in the change in the primary outcome from baseline between the groups (i.e., 75% higher intensity post-intervention) can be detected with >99% power (intraclass coefficient [ICC] = 0.02–0.05). In a more conservative estimate, a 10% absolute difference (i.e., 60% higher intensity post-intervention) can be detected with 90% power (ICC = 0.02) and 84% power (ICC = 0.05).

Discussion

AOM is the most common indication for antibiotic prescriptions for children; thus, it is imperative to develop interventions to improve prescribing for AOM to optimize clinical outcomes and reduce unnecessary antibiotic exposure and its inherent risks. Preventing unnecessarily long durations of antibiotic therapy for AOM is one key opportunity to reduce antibiotic use for pediatric AOM. Interventions to promote the shortest effective duration of antibiotic therapy for common infections have proven to be a highly effective outpatient antibiotic stewardship approach. Unfortunately, pragmatic interventions to reduce durations of therapy that can be effectively scaled and sustained are lacking. This study aims to fill this gap by evaluating the effectiveness and implementation outcomes of two low-cost pragmatic interventions of differing intensities to increase prescribing of recommended short antibiotic durations for AOM in children 2 years of age and older.

The strengths of this study include the cluster-randomized design, large number of participating clinics, diversity of the practice types (primary care, urgent care, retail clinics), and the mixed methods approach to guide implementation and evaluate outcomes and sustainability. Furthermore, the components of the intervention are pragmatic and utilize freely available tools so could be implemented in clinics with limited resources. Limitations include use of secondary data to evaluate changes in antibiotic durations associated with the intervention and clinical outcomes, minimal geographic diversity with only two participating health systems, and the inability to assess the long-term sustainability of the interventions. Nevertheless, this study will represent a substantial contribution to the pediatric AOM literature where large, randomized trials have been lacking, provide a framework for other healthcare systems to address the widespread problem of excessive durations of therapy for AOM, and inform national antibiotic stewardship policy development.

Summary points

Preventing unnecessarily long durations of antibiotic therapy is a key opportunity to reduce antibiotic overuse in children 2 years of age and older with acute otitis media (AOM).

This study aims to fill the need for pragmatic interventions to reduce durations of antibiotic therapy by evaluating the effectiveness and implementation outcomes of two low-cost interventions of differing intensities to increase guideline-concordant antibiotic durations in children with AOM.

Intervention components are based on the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Core Elements of Outpatient Antibiotic Stewardship and will include clinician education regarding guideline-recommended short durations of antibiotic therapy; electronic health record (EHR) prescription field changes to promote prescribing of recommended short durations; and individualized clinician audit and feedback on adherence to recommended short durations of therapy in comparison to peers.

The study will take place in 35 clinics in the Vanderbilt University Medical Center and Washington University Medical Center systems.

We will seek input from key stakeholders to guide this research, increase the likelihood of success of the interventions, and disseminate the trial results.

Contextual factors will be assessed at the patient/parent, clinician, clinic, and health systems levels using key informant semi-structured interviews and focus groups, process mapping, and EHR data analysis.

The study will use a type 2 hybrid implementation-effectiveness design to evaluate effectiveness and implementation outcomes using the Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance (RE-AIM) framework and the Practical Implementation Sustainability Model (PRISM).

The results of this study will provide a framework for other healthcare systems to address the widespread problem of excessive durations of therapy for AOM and inform national antibiotic stewardship policy development.

Footnotes

Author contributions

A Keith was responsible for writing the original draft and review and editing of the manuscript. TC Jenkins was responsible for writing the original draft and review and editing of the manuscript. S O'Leary was responsible for writing the original draft and review and editing of the manuscript. AB Stein was responsible for review and editing of the manuscript. SE Katz was responsible for review and editing of the manuscript. J Newland was responsible for review and editing of the manuscript. DJ Rinehart was responsible for review and editing of the manuscript. A Gilbert was responsible for editing and review of the manuscript. S Dodd was responsible for editing and review of the manuscript. CM Terrill was responsible for editing and review of the manuscript. HM Frost was responsible for conceptualization and review and editing of the manuscript.

Financial disclosure

This project was funded under grant no. 1R01HS029153-01 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The authors are solely responsible for this document's contents, findings, and conclusions, which do not necessarily represent the views of AHRQ. Readers should not interpret any statement in this report as an official position of AHRQ or of HHS. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Competing interests disclosure

The authors have no competing interests or relevant affiliations with any organization or entity with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Writing disclosure

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

Open access

This work is licensed under the Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as: • of interest

- 1.Kaur R, Morris M, Pichichero ME. Epidemiology of acute otitis media in the postpneumococcal conjugate vaccine era. Pediatrics 140(3), 1–9 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010–2011. JAMA 315(17), 1864–1873 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Highlights the scope of the problem of over-prescribing antibiotics.

- 3.Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, Shah SS. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics 128(6), 1053–1061 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kozyrskyj A, Klassen TP, Moffatt M, Harvey K. Short-course antibiotics for acute otitis media. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 9(Cd001095),1–16 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This is a large meta-analysis that demonstrates the safety and efficacy of short versus long durations of antibiotics for uncomplicated acute otitis media.

- 5.Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 131(3), e964–999 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This reference is for the American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute otitis media (AOM).

- 6.Frost HM, Bizune D, Gerber JS, Hersh AL, Hicks LA, Tsay SV. Amoxicillin versus other antibiotic agents for the treatment of acute otitis media in children. J.Pediatr. 251, 98–104.e5 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • This demonstrates the current scope of the problem of over-prescribing longer than guideline recommended durations and compares treatment failure rates between long and short antibiotic durations in the United States.

- 7.Frost HM, Becker LF, Knepper BC, Shihadeh KC, Jenkins TC. Antibiotic prescribing patterns for acute otitis media for children 2 years and older. J. Pediatr. 220, 109–15.e1 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGrath LJ, Frost HM, Newland JG et al. Utilization of nonguideline concordant antibiotic treatment following acute otitis media in children in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 32(2), 256–265 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerber JS, Ross RK, Bryan M et al. Association of broad- vs narrow-spectrum antibiotics with treatment failure, adverse events, and quality of life in children with acute respiratory tract infections. JAMA 318(23), 2325–2336 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC. www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest-threats.html (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miranda-Katz M, Parmar D, Dang R, Alabaster A, Greenhow TL. Epidemiology and risk factors for community associated Clostridioides difficile in children. The Journal of Pediatrics. 221, 99–106 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kronman MP, Zaoutis TE, Haynes K, Feng R, Coffin SE. Antibiotic exposure and IBD development among children: a population-based cohort study. Pediatrics 130(4), e794–803 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ni J, Friedman H, Boyd BC et al. Early antibiotic exposure and development of asthma and allergic rhinitis in childhood. BMC pediatrics. 19(1), 225 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horton DB, Scott FI, Haynes K et al. Antibiotic exposure and juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a case-control study. Pediatrics 136(2), e333–343 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frost HM, Lou Y, Keith A, Byars A, Jenkins TC. Increasing guideline-concordant durations of antibiotic therapy for acute otitis media. J.Pediatr. 240, 221–7.e9 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Demonstrates the comparative effectiveness of the two proposed stewardship interventions in a large system of federally qualified health centers.

- 16.Holtrop JS, Estabrooks PA, Gaglio B et al. Understanding and applying the RE-AIM framework: clarifications and resources. Clin. Transl. Sci. 5(1), e126 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am. J. Public Health 89(9), 1322–1327 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldstein AC, Glasgow RE. A practical, robust implementation and sustainability model (PRISM) for integrating research findings into practice. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 34(4), 228–243 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med. Care 50(3), 217–226 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; • Provides details on the use of implementation effectiveness designs.

- 20.Glasgow R et al. Making Implementation science more rapid: use of the RE-AIM framework for mid-course adaptations across five health services research projects in the veterans health administration. front. Public Health. 8(194), (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beebe J. Rapid Assessment Process: An Introduction. altaMira Press. 1st Edition, 1–199 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor B, Henshall C, Kenyon S, Litchfield I, Greenfield S. Can rapid approaches to qualitative analysis deliver timely, valid findings to clinical leaders? A mixed methods study comparing rapid and thematic analysis. BMJ Open. 8(10), e019993 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holdsworth LM, Safaeinili N, Winget M et al. Adapting rapid assessment procedures for implementation research using a team-based approach to analysis: a case example of patient quality and safety interventions in the ICU. Implement Sci. 15(1), 12 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palinkas LA, Zatzick D. Rapid assessment procedure informed clinical ethnography (RAPICE) in pragmatic clinical trials of mental health services implementation: methods and applied case study. Adm. Policy Ment. Health 46(2), 255–270 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mangione-Smith R. Dialogue around respiratory illness treatment. University of Washington. https://www.uwimtr.org/dart/ (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Fiks AG et al. Effect of an outpatient antimicrobial stewardship intervention on broad-spectrum antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians: a randomized trial. JAMA 309(22), 2345–2352 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frost HM, Munsiff SS, Lou Y, Jenkins TC. Simplifying outpatient antibiotic stewardship. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 43(2), 260–261 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chamberlain P, Brown CH, Saldana L. Observational measure of implementation progress in community based settings: the stages of implementation completion (SIC). Implement Sci. 6(1), 116 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implement Sci. 12(1), 108 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Malone S, Prewitt K, Hackett R et al. The clinical sustainability assessment tool: measuring organizational capacity to promote sustainability in healthcare. Implement Sci. Communications. 2(1), 77 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saldana L, Chamberlain P, Bradford WD, Campbell M, Landsverk J. The cost of implementing new strategies (COINS): a method for mapping implementation resources using the stages of implementation completion. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 39, 177–182 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]