Abstract

Myxococcus xanthus has been shown to utilize both directed (tactic) and undirected (kinetic) movements during different stages of its complex life cycle. We have used time-lapse video microscopic analysis to separate tactic and kinetic behaviors associated specifically with vegetatively swarming cells. Isolated individual cells separated by a thin agar barrier from mature swarms showed significant increases in gliding velocity compared to that of similar cells some distance from the swarm. This orthokinetic behavior was independent of the frequency of reversals of gliding direction (klinokinesis) but did require both the Frz signal transduction system and S-motility. We propose that M. xanthus uses Frz-dependent, auto-orthokinetic behavior to facilitate the dispersal of cells under conditions where both cell density and nutrient levels are high.

The gliding bacterium Myxococcus xanthus has been reported to display both chemokinetic and chemotactic behavioral responses (4, 14). Chemokineses, which may involve changes in speed (orthokineses) or changes in turning frequency (klinokineses) (5) are usually considered to result in the dispersal of organisms, whereas chemotaxes (or, more properly, chemo-klinokineses with adaptation) allow cells to move up gradients of chemicals, which results in their accumulation. While individual M. xanthus cells have never been shown to move up chemical gradients (19), under nutrient-rich conditions groups of vegetative cells have been shown to move outward from an inoculation point as a coordinated swarm in order to colonize new areas (14, 15). Additionally, when starved, developmental cells aggregate into discrete mounds or fruiting bodies, within which the cells undergo morphogenesis to form environmentally resistant myxospores. Both the dispersal mechanism of vegetative swarming and the accumulation mechanism of developmental aggregation have been suggested to involve tactic responses to attractant stimuli, which are mediated by the Frz signal transduction system. Excitation responses to attractants are defined in this system as causing methylation of the sensor protein of the Frz signal transduction pathway, FrzCD (a methyl-accepting chemotaxis protein homolog), and result in a decrease in the reversal frequency of cellular gliding (9, 15, 16). The Frz signal transduction system shows many such similarities to the chemotaxis system of the enteric bacteria (8, 10). However, there are substantial differences between chemotaxis in the enteric bacteria (1) and directed motility in M. xanthus. For example, only responses of M. xanthus to repellent stimuli are similar to responses of enteric bacteria. Responses to attractant stimuli appear to be more complex, involving not only FrzCD, FrzA (a CheW homolog), and FrzE (a CheA-CheY fusion homolog) but also FrzZ (a dual domain CheY-CheY homolog) (20) and FrzB (a protein with no enteric homolog). The complex nature of responses of M. xanthus to attractant stimuli and its lack of responses to specific nutrient stimuli (9, 19) have led to the suggestion that this slow-moving organism may respond only to self-generated, auto-attractant molecules (22). The term chemotaxis is commonly used to refer to any directional movement of bacteria towards, or away from, chemicals, regardless of the underlying mechanisms, but we have coined the term autochemotaxis when discussing the directed motility of M. xanthus since it better describes the complex nature of the responses displayed by this bacterium.

Dworkin and Eide (4), while analyzing the motility behavior of M. xanthus, observed that gliding velocity was dependent on nutrient concentration and that high levels of nutrients could temporarily inhibit motility, thereby trapping cells in nutritionally favorable areas. Such chemokinetic behavior appears unusual, since orthokineses usually result in the distribution of organisms rather than their accumulation (12). Behavior more typical of chemokinesis was reported by Kaiser and Crosby (7), who used a swarm expansion assay to measure the rate at which cells colonize new areas. Those authors showed that gliding speed is dependent on cell density. In this study we have analyzed the behavior of individual cells plated either over large swarms or at a significant distance from the swarm, with a thin agar barrier being used to separate the two layers of cells. We provide preliminary evidence that vegetative swarms may release a diffusable factor which in trans increases gliding velocity. This increase in the speed of gliding was independent of klinokinetic, or tactic, behavior (in that it did not involve a change in the reversal frequency of gliding), but it required the Frz signal transduction system and S-motility. We propose that this auto-orthokinetic behavior may be a mechanism for efficient dispersal at high cell densities.

Time-lapse motion analysis.

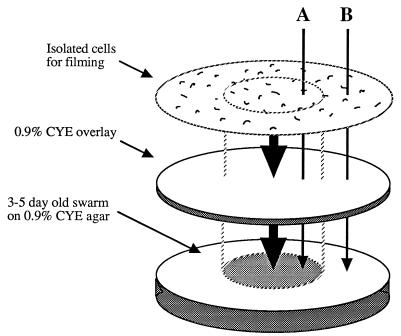

The M. xanthus strains used in this study are shown in Table 1. Cells were grown in CYE medium (2) at 32°C on a rotary shaker at 225 rpm. Swarm plates (14) and swarm plate overlays were prepared with CYE broth solidified with 0.9% agar (Difco). Plates for filming were prepared in two stages. In the first stage wild-type M. xanthus DZ2 cells were inoculated onto swarm plates (25 ml), which were incubated for 3 to 4 days at 32°C until the cells formed swarms of 3- to 5-cm diameters. Cooled agar overlays, which were used as barriers to the movement of cells (but not to that of diffusable molecules), were then poured carefully over the surfaces of these swarm plates; care was taken not to disturb the bacteria in the swarm. A 5-ml volume of agar was used to form the overlay, which measured approximately 1 mm in depth once the agar was poured. These plates were then incubated at room temperature for 5 to 6 h (incubation for a shorter period was insufficient for observation of the reported effect). In the second stage, overnight cultures of the bacterial strains to be analyzed were diluted in CYE broth to approximately 107 cells per ml, and then a 50-μl volume was spread on top of the agar overlays. Isolated individual cells at positions directly over the swarm and (on the same plate) at some distance from the underlying swarm (at least 1 cm from the edge of the swarm) were then filmed by time-lapse video microscopy for periods of 30 min. Fields of 10 to 30 cells were documented at a time, and analyses were performed on totals of between 50 and 150 cells per experiment. Cells were observed with a Nikon Labphot-2 microscope with a 40× objective. Images were recorded with a Dage-MTI CCD-72 series camera and a time-lapse video cassette recorder (120-h speed setting; model GYYR TLC 1800). Filming was started 10 to 15 min postinoculation and continued for up to 3 h. Longer periods of filming were avoided to minimize cell-cell interactions (which are known to influence motility behavior [14]) within the population of cells on the overlay. Data were analyzed manually by tracing the movement of the cells during playback. Gliding-speed measurements (transient velocities) were taken from motile cells only between reversals or stops.

TABLE 1.

M. xanthus strains

Underlying swarms influence gliding velocities of individual cells on an overlay.

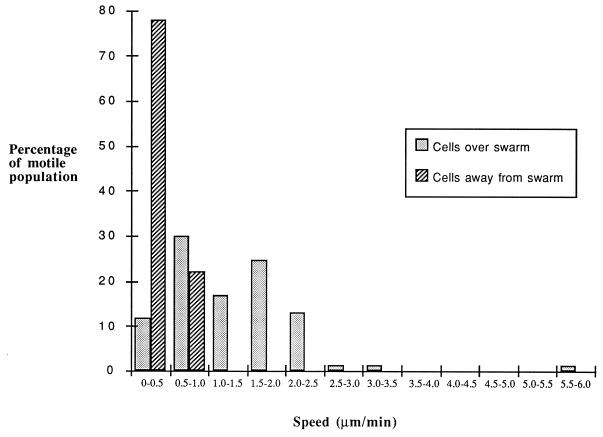

Figure 1 shows a diagram of the experimental design with which the effect of an underlying swarm of M. xanthus on individual cells separated from the swarm by an agar barrier was determined. Under the conditions used, wild-type (strain DZ2) cells positioned at least 1 cm away from the underlying swarm moved very slowly, with a mean speed ± the standard deviation of 0.4 ± 0.1 μm/min. In contrast, cells positioned above the swarm were moving significantly faster at 1.3 ± 0.8 μm/min. Figure 2 shows the distribution of gliding velocities within wild-type populations both over and away from the underlying swarms; the differences in the speeds of movement are clearly significant, although the speeds are somewhat slower than normal M. xanthus gliding speeds (3.8 μm/min on 1.5% agar when the cells are separated by more than 0.5 μm from each other [18]). However, adventurous motility is known to be reduced on soft agar (13) and the use of 0.9% agar in this assay may have contributed to the generally slow gliding speeds. No adaptation, resulting in reduced gliding velocity, was seen during the course of the experiment. Samples of cells filmed directly after inoculation had average gliding velocities of 1.43 ± 0.59 μm/min, while cells filmed on the same plate approximately 2 h after inoculation showed slight increases in gliding velocities (1.78 ± 0.52 μm/min), suggesting that the response is sustained or perhaps even enhanced over time. These results suggest that vegetatively swarming cells produce an extracellular substance that increases the gliding velocity of closely associated cells but that this stimulation does not require cell-cell contact. However, it might alternatively be postulated that the underlying swarm is removing either nutrients or an unknown motility-inhibiting factor from the top agar during the 5- to 6-h incubation time. Neither of these possibilities was supported by a control experiment which showed that removal of the swarm prior to the addition of the top agar had no effect on the reported chemokinetic response (data not shown). Furthermore, insertion of a dialysis membrane between the underlying swarm and the cell overlay blocked the stimulatory effect (see below).

FIG. 1.

Diagram of experimental protocol. The motility behavior of cells was analyzed under conditions in which cells were located directly over an underlying swarm (A) and in which cells were at least 1 cm from the underlying swarm (B). A thin agar overlay acted as a barrier between the individual cells on the overlay and the underlying swarm.

FIG. 2.

Speeds of M. xanthus DZ2 cells within motile populations moving either over or away from underlying wild-type DZ2 swarms. Swarm plates and swarm plate overlays were both prepared with CYE containing 0.9% agar.

Chemokinetic stimulation requires the Frz signal transduction system and S-motility.

In order to further characterize this chemokinetic effect, we studied the movement of several motility and chemotaxis mutants using the experimental plan described in Fig. 1. While the mechanism for gliding motility and the motor which powers it are still unknown, two distinct motility systems with defined properties have been identified in M. xanthus (6). The A-motility system, which controls adventurous gliding (and is most efficient on dry surfaces [13]), allows individual cells to move in the absence of others. The S-motility system, which controls social gliding and is more active under moist conditions, requires cell-cell interactions and involves type IV pili (23). While A+ S− cells are individually capable of motility, A− S+ cells are never seen moving more than one cell’s distance from each other. During filming, the A− S+ strain DK1218 showed no movement since the experimental design required a low density of plating, resulting in individual cells that were not within contact distance of each other. The A+ S− strain DK1300 did show motility under these conditions, but there was little difference in speeds between those cells moving over and those moving away from the underlying swarm (the velocity of cells moving over the swarm was 0.4 ± 0.1 μm/min, while only a single cell was seen moving away from the swarm and had a measured velocity of 0.4 μm/min). It is not understood at this time why cells moving by A-motility should require the S-motility system for this behavioral response; however, the S-motility system does appear to be required for this autochemokinesis.

The Frz signal transduction system is known to be central to the regulation of directed motility in M. xanthus (22). However, its role in kinetic behavior is unknown. We therefore tested several frz mutants for an orthokinetic response under the conditions of our assay. Mutants with defects in frzCD (DZ4169), frzE (DZ4148), and frzZ (DZ4146) showed no response to the presence of an underlying swarm. DZ4169 moved at mean speeds of 0.5 ± 0.25 μm/min over the swarm and 0.3 ± 0.1 μm/min away from the swarm; DZ4148 moved at mean speeds of 0.5 ± 0.25 μm/min over the swarm and 0.4 ± 0.2 μm/min away from the swarm; and DZ4146 moved at mean speeds of 0.6 ± 0.25 μm/min over the swarm and 0.4 ± 0.2 μm/min away from the swarm. These results suggest that the diffusable molecule that stimulates chemokinesis may interact with components of the Frz system to have its effect. However, since this molecule has not yet been identified and the experimental design is limiting, we cannot at present determine if this interaction is direct or indirect.

Chemokinetic signal cannot penetrate a dialysis membrane barrier.

The ability of an underlying swarm to induce faster gliding speeds in individual cells through an agar barrier suggests that the swarm may be producing a diffusable chemokinetic substance. To see if this substance is a small molecule, a Spectra/Por dialysis membrane (molecular weight cutoff, 12,000 to 14,000) was inserted between the swarm and the agar overlay and then cells both over and away from the swarm were analyzed as described previously. Under these conditions, no increase in the speed of gliding over the swarm by wild-type DZ2 cells was observed (the mean speeds of cells were 0.4 ± 0.2 μm/min when they were gliding over the swarm and 0.2 ± 0.1 μm/min when they were gliding away from the swarm), indicating that the stimulatory factor is not a small molecule and may be larger in size than the 12,000 to 14,000 exclusion size of the membrane. However, no studies were performed to identify a dialysis membrane which would allow diffusion of the putative stimulatory molecule. It should be noted that dialysis membranes often contain residual glycerol, sulfur, or heavy metals which might potentially have an effect on gliding speeds, preventing chemokinesis.

Reversal frequencies and the chemotactic response.

While the kinetic behavior of DZ2 cells positioned in close association with wild-type swarms showed sustained increases in velocity and no apparent adaptation, the loss of this effect in the frz mutant strains suggests that such chemokinetic behavior may be associated with the Frz signal transduction system and therefore klinokinetic or tactic behavior. Therefore, the reversal frequencies of wild-type DZ2 cells both over and away from underlying swarms were analyzed. However, no significant differences between the frequency of reversals of cells gliding over the underlying swarm and that of cells gliding away from the underlying swarm were found. DZ2 cells reversed on average 1.8 times during a 30-min period of filming when gliding over the swarm and on average 2.0 times when gliding away from the swarm, suggesting that although this chemokinetic effect may require the Frz signal transduction system, it is distinct from the previously reported tactic behavior.

Underlying swarm cells influence the proportion of cells moving on the agar overlay.

During the analysis of gliding speeds of both wild-type and mutant strains of M. xanthus, it was observed that the individual cells inoculated onto swarm plates were frequently more likely to be motile when they were positioned directly over the swarm. We therefore scored the frequency of motile cells observed directly over or distant from the swarms (Table 2). Cells were considered motile if they showed recordable movements during the course of filming. In wild-type DZ2 cells, only 19% of cells distant from the underlying swarm were motile during the 30 min of filming. In contrast, 82% of cells directly over the swarm were motile. This pattern was repeated for most of the strains tested, suggesting that vegetative swarms may produce a second diffusable factor that stimulates motility but that acts independently of either S-motility or the Frz signal transduction system. This putative motility stimulation factor was not blocked by the dialysis membrane barrier (molecular weight cutoff, 12,000 to 14,000), which indicates that this stimulatory effect may involve a low-molecular-weight molecule. However, this behavior was not displayed by all of the strains tested and requires further analysis.

TABLE 2.

Frequencies of motile cells observed

| Strain | Relevent phenotype | Motile population (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Over swarm | Away from swarm | ||

| DZ2 | WTa | 82 | 19 |

| DZ2 (mwcob) | WT | 87 | 30 |

| DZ4169 | FrzCD | 68 | 17 |

| DZ4148 | FrzE | 60 | 60 |

| DZ4146 | FrzZ | 73 | 70 |

| DK1300 | A+ S− | 70 | 11 |

| DK1218 | A− S+ | 0 | NDc |

WT, wild type.

mwco, molecular weight cutoff membrane.

ND, not determined.

What is the role of chemokinesis in swarming?

In this study we have identified an orthokinetic behavioral response associated with nutrient-rich conditions and swarming M. xanthus colonies. The ability of a vegetative swarm of M. xanthus cells to influence the behavior of individual cells, physically isolated from the swarm, suggests that the inducer of the chemokinetic response is produced by the swarm and that the behavior identified is an example of auto-orthokinesis. While we have not yet attempted to isolate the chemical responsible for this behavior, a substance with a molecular weight greater than 12,000 to 14,000 is probable, since a molecular weight cutoff membrane of this size, when it was used as a barrier, stopped the response. Although this chemokinetic behavior is associated with nutrient-rich conditions, it is distinct from that previously reported by Dworkin and Eide (4), in whose report a response suggested to facilitate cell accumulation in nutrient-rich areas was described. Under the conditions used in this study, where cell density was high, the resultant chemokinetic response favored cell dispersal.

While this chemokinetic behavior requires a functional Frz signal transduction system, it appears to be independent of tactic responses, since sustained increases in gliding velocity were demonstrated independently of changes in reversal frequency. Separate chemokinetic and chemotactic behaviors have been previously identified in Rhodobacter sphaeroides (11), which, like M. xanthus, has multiple CheY homologs (21). Multiple CheY homologs have also been identified in the closely related species Rhizobium meliloti, where CheY2 is suggested to be the major chemokinetic response regulator, with phosphorylation by CheA being indispensable for its function (17). The loss of chemokinesis in the frz mutant strains suggests that the dual CheY-like response regulators of FrzZ may have similar roles in chemokinesis and require phosphorylation by FrzE for function.

In conclusion, M. xanthus may utilize both autochemotaxis and auto-orthokinesis to regulate its motility behavior. In this study we have identified a Frz-dependent orthokinetic response that is independent of previously reported chemotactic and chemokinetic behaviors (14) but which may promote the efficient dispersal of cells under conditions of high cell density and good nutrition.

Acknowledgments

Research in our laboratory is supported by Public Health Service grant GM20509 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blair D F. How bacteria sense and swim. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1995;49:489–522. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.49.100195.002421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campos J M, Geisselsoder J, Zusman D R. Isolation of bacteriophage Mx4, a generalized transducing phage for Myxococcus xanthus. J Mol Biol. 1978;119:167–178. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campos J M, Zusman D R. Regulation of development in Myxococcus xanthus: effect of 3′:5′ cyclic AMP, ADP and nutrition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:518–522. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.2.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dworkin M, Eide D. Myxococcus xanthus does not respond chemotactically to moderate concentration gradients. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:437–442. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.437-442.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fraenkel G S, Gunn D L. The orientation of animals: kineses, taxes and compass reactions. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press; 1940. . [Reprint with additional notes, Dover Publications, New York, N.Y., 1961.] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodgkin J, Kaiser D. Genetics of gliding motility in Myxococcus xanthus (Myxobacterales): two gene systems control movement. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;171:177–191. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaiser D, Crosby C. Cell movement and its coordination in swarms of Myxococcus xanthus. Cell Motil. 1983;3:227–245. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McBride M J, Weinberg R A, Zusman D R. “Frizzy” aggregation genes of the gliding bacterium Myxococcus xanthus show sequence similarities to the chemotaxis genes of the enteric bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:424–428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McBride M J, Kohler T, Zusman D R. Methylation of FrzCD, a methyl-accepting taxis protein of Myxococcus xanthus, is correlated with factors affecting cell behavior. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:4246–4257. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.13.4246-4257.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCleary W R, Zusman D R. FrzE of Myxococcus xanthus is homologous to both CheA and CheY of Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5898–5902. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Packer H L, Armitage J P. The chemokinetic and chemotactic behavior of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: two independent responses. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:206–212. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.206-212.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnitzer M J, Block S M, Berg H C, Purcell E M. Strategies for chemotaxis. Symp Soc Gen Microbiol. 1990;46:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi W, Zusman D R. The two motility systems of Myxococcus xanthus show different selective advantages on various surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3378–3382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shi W, Kohler T, Zusman D R. Chemotaxis plays a role in the social behaviour of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:601–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi W, Ngok F K, Zusman D R. Cell density regulates cellular reversal frequency in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4142–4146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.9.4142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Søgaard-Andersen L, Kaiser D. C factor, a cell-surface-associated intercellular signalling protein, stimulates the cytoplasmic Frz signal transduction system in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2675–2679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.7.2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sourjik V, Schmitt R. Different roles of CheY1 and CheY2 in the chemotaxis of Rhizobium meliloti. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:427–436. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.1291489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spormann A M, Kaiser A D. Gliding movements in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5846–5852. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5846-5852.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tieman S, Koch A, White D. Gliding motility in slide cultures of Myxococcus xanthus in stable and steep chemical gradients. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3480–3485. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3480-3485.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trudeau K G, Ward M J, Zusman D R. Identification and characterization of FrzZ, a novel response regulator, necessary for swarming and fruiting body formation in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:645–655. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5521075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ward M J, Bell A W, Hamblin P A, Packer H L, Armitage J P. Identification of a chemotaxis operon with two cheY genes in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:357–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17020357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward M J, Zusman D R. Regulation of directed motility in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:885–893. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4261783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu S S, Kaiser D. Genetic and functional evidence that type IV pili are required for social gliding motility in Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:547–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18030547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]