Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

Unhealthy dietary behaviors constitute one of risk the factors for chronic and cardiovascular diseases, which are prevalent in middle-aged and older populations. Milk and dairy products are high-quality foods and important sources of calcium. Calcium protects against osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. Therefore, this study investigated the association of milk and dairy product consumption with cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence in middle-aged and older Korean adults.

SUBJECTS/METHODS

Data were derived from the Ansan–Anseong cohort study, and a total of 8,009 individuals aged 40–69 years were selected and followed up biennially. Cox proportional hazard models were used to examine the association of milk and dairy product consumption with cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence.

RESULTS

During a mean follow-up period of 96.5 person-months, 552 new cases of cardio-cerebrovascular disease were documented. Milk consumers (< 1 serving/day) exhibited a 23% lower risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence than non-milk consumers (hazard ratio [HR], 0.77; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.61–0.97; P for trend = 0.842). High yogurt consumption was associated with a 29% lower incidence risk (≥ 0.5 servings/day vs. none: HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.53–0.96; P for trend = 0.049), whereas high ice cream consumption was associated with a 70% higher risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence (≥ 0.5 servings/day vs. none: HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.01–2.88; P for trend = 0.070).

CONCLUSIONS

This study indicates that less than one serving of milk and high yogurt consumption are associated with a lower cardio-cerebrovascular disease risk in the middle-aged and older populations.

Keywords: Milk, cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular disorders, cohort studies

INTRODUCTION

Cardio-cerebrovascular disease is a term that encompasses cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Cardiovascular diseases are coronary artery diseases, such as including myocardial infarction and angina pectoris. Cerebrovascular diseases include stroke and cerebral infarction. These diseases often co-occur via the interaction of multiple common risk factors, resulting in an increased prevalence and mortality [1].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), ischemic heart disease ranked first and stroke second as the leading causes of death worldwide in 2020 [2]. Globally, cardiovascular disease mortality increased by 12.5% from 2005 to 2015, and disease severity increased as well [3]. Cardio-cerebrovascular disease has emerged as a serious health problem worldwide. In particular, the high socio-economic burden posed by cardiovascular diseases is increasing in Korea due to an aging society. Effective strategies are urgently required for disease control and prevention, considering the substantial cardio-cerebrovascular disease burden in Korea.

The WHO suggests unhealthy eating behaviors, lack of physical activity, smoking, and excessive alcohol consumption as risk factors for cardio-cerebrovascular disease. Among them, dietary factors constitute one of the modifiable risk factors [4]. Health problems, such as chronic diseases, often commence in early-middle and older age. Therefore, customizing nutritional management to decelerate aging and disease progression and prevent cardio-cerebrovascular disease development in necessary.

Milk is a major source of calcium, and it is rich in nutrients, including protein, vitamins B2 and B12, riboflavin, and potassium. High consumption of milk and dairy products has been reported to lower the risk of metabolic syndrome and cardio-cerebrovascular disease due to their high calcium content, which reduces blood pressure [5]. It has reported that calcium reduced calcitriol and fat production levels by regulating the leptin and glucagon-like peptide-1 signaling, thereby ameliorated cardiovascular disease risk [6]. In addition, cardiovascular disease risk is low in Korean adult women with high calcium intake [7].

Various meta-analyses have reported that the consumption of milk and dairy products reduces the risk of various diseases, such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardio-cerebrovascular disease [8,9,10,11]. Most previous studies investigating the association of milk and dairy product consumption with metabolic disease among Korean populations followed a cross-sectional study design [12,13]. A cross-sectional study on milk intake and cardiovascular disease risk in Koreans was recently conducted [14]. Studies analyzing the efficacy of intervention studies on cardio-cerebrovascular disease suggested that longer follow-up periods were necessary to determine the ability of these intervention to reduce disease incidence and mortality [15]. Furthermore, a United Kingdom Biobank-based large population cohort study reported a negative association between cardiovascular disease outcome and the consumption of various types of milk [16]. Although a large-scale cohort study on milk and dairy product consumption in Korea found an association with metabolic syndrome [17], evidence regarding the association of milk and dairy product consumption with cardio-cerebrovascular disease risk based on large-scale, long-term longitudinal studies in Korea is limited. Therefore, this study utilized community-based cohort data to elucidate the association of milk and dairy product consumption with cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence in middle-aged and older Korean adults.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study population

The research data were collected from the Ansan–Anseong cohort study (community-based cohort), a Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. The KoGES was conducted in 2001 and designed to investigate the effects of lifestyle, diet, and environmental factors on the chronic disease incidence in small and medium-sized cities and rural residents [18].

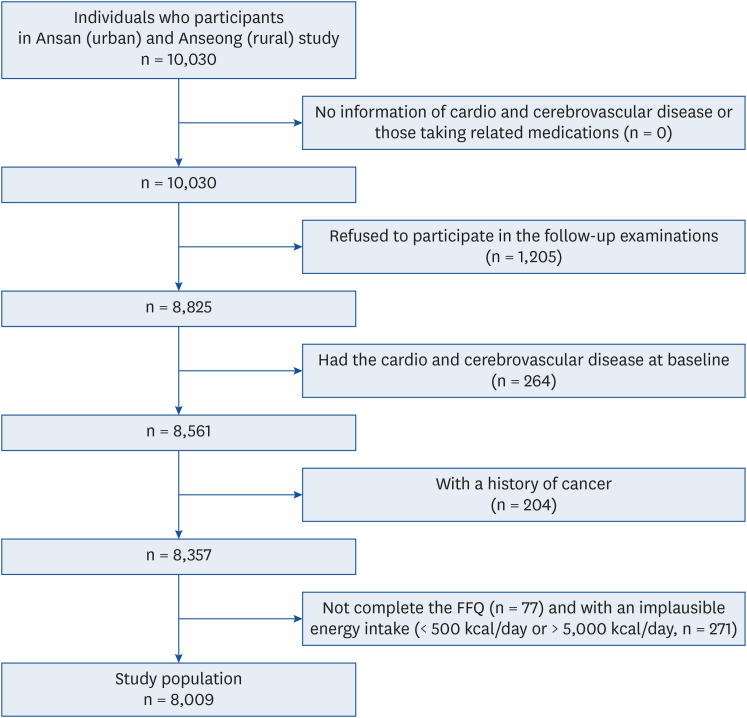

In brief, a baseline examination was conducted in 2001–2002, involving 10,030 adults aged 40–69 years who resided in Ansan (urban region) or Anseong (rural region) [18]. Seven follow-up examinations were conducted in 2003–2004, 2005–2006, 2007–2008, 2009–2010, 2011–2012, 2013–2014, and 2015–2016. Of the 10,030 participants, those who (1) had no information regarding cardio and cerebrovascular disease, were taking related medications, and refused to participate in follow-up examinations (n = 1,205); (2) had cardiocerebrovascular disease at baseline (n = 264); (3) had a history of cancer (n = 204); (4) did not complete the food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) at baseline and during follow-up examinations (n = 77); (5) or had an implausible energy intake (< 500 kcal/day or > 5,000 kcal/day, n = 271) were excluded at baseline. Thus, 8,009 participants were included in the final analysis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Sampling process of study population of Ansan and Anseong study.

FFQ, food frequency questionnaires.

The observation period for individuals who reported any diagnosis or treatment of cardio-cerebrovascular disease during the follow-up was defined as the time between the baseline examination and the date of the first cardio-cerebrovascular disease diagnosis. The observation period for participants who did not develop cardiovascular disease during the follow-up period was considered the period from the date of entry into the baseline study to the date of the final follow-up visit. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ewha Womans University (No. ewha-202007-0004-01).

Dietary assessment

Dietary information was extracted at baseline by trained dietitians using a validated FFQ [19]. The frequency of milk and dairy product consumption was determined by calculating the number of servings per day. One serving was equal to 200 mL of milk, 120 mL of yogurt, 120 g of ice cream, and 20 g of cheese [20].

For analysis, milk and dairy product consumption were converted to daily frequency based on the reported portion size of each food. According to the 2020 Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans, adults aged 19–64 years are recommended to consume milk and dairy products once a day [21]. In this study, the frequency of milk consumption was established based on one serving per day. However, since dairy consumption is often lower than milk consumption, the frequency of dairy product consumption was established based on 0.5 servings per day. Therefore, milk consumption was categorized into 3 groups (none, < 1 serving/day, and ≥ 1 serving/day), and dairy product consumption (yogurt, ice cream, and cheese) was also categorized into 3 groups (none, < 0.5 servings/day, and ≥ 0.5 servings/day).

General characteristics

A questionnaire was administered to extract data on general characteristics, such as age, sex, residential area, education level, household income, and lifestyle variables, including current smoking status, current alcohol intake, and physical activity level, at each examination visit. Education and income levels were reclassified from a total of 8 categories into 4 categories, considering ease of interpretation and participant- response distribution. Educational level was categorized into 4 groups: elementary school graduation or lower, middle school graduation, high school graduation, and college graduation or higher. Average monthly household income was also categorized into 4 groups, ranging from < 1,000,000 KRW to ≥ 4,000,000 KRW. Physical activity was evaluated using metabolic equivalent tasks (METs) hours per day. After establishing a MET value for each level of physical activity, the MET value for each physical activity level was calculated [20]. The MET is a method of displaying physical activity intensity according to the type of physical activity, and 1 MET indicates that 3.5 mL of oxygen was consumed per minute during a break per 1 kg of body weight [22,23]. Disease History was confirmed in those who answered “yes” regarding a previous diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes, or dyslipidemia. Moreover, energy, carbohydrate, fat, protein, and calcium intakes are presented as mean daily intakes.

Definition of the cardio-cerebrovascular disease

Cardio-cerebrovascular disease refers to a disease affecting to the heart and blood vessels, and it has been reported to be highly associated with an increased risk of thrombosis caused mainly by fatty deposits in the cardiovascular and cerebrovascular vessels [24]. In this study, cardio-cerebrovascular disease was defined as a general term for (1) cardiovascular diseases, including myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, congestive heart failure, and coronary artery disease, and (2) cerebrovascular diseases, including stroke. Cardio-cerebrovascular disease was confirmed based on the self-reporting of newly diagnosed myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, or cerebrovascular disease or taking of anticoagulants or stroke medication during the biennial follow-up examinations. The concordance between self-reported disease diagnoses and those confirmed by medical record review has been reported to reach 93% [25].

Statistical analysis

Among the baseline characteristics, categorical variables are presented as percentages, and they were analyzed using the χ2 test, whereas continuous variables are presented as the mean ± SD, and P-values for trends were derived from general linear model analysis. In this study, analyses were performed after assuming a proportional risk model via survival analysis (Kaplan-Meier). Cox’s proportional hazard models were used in survival analysis to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence during the follow-up period according to milk and dairy product consumption. Three covariate models were stratified and systemically analyzed to account for bias caused by confounding variables via Cox proportional hazard models. Potential confounding variables were identified from previous studies [26,27,28,29]. Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex and Model 2 was additionally adjusted for residential area, education level, household income, current smoking status, current alcohol intake, regular exercise, body mass index (BMI), and history of diseases. Model 3 was further adjusted for total energy intake (kcal/day), carbohydrate, fat, and protein intakes (g/d) and Ca intake (mg/d). SPSS 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 25.0; IBM-SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses, and statical significance was set at P-value < 0.05.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the subjects according to milk consumption

The general characteristics of the study participants according to milk consumption are presented in Table 1. Compared with non-milk consumers, milk consumers tended to be younger and reside in Ansan (urban) (P < 0.001). Frequent milk consumers had higher education and income levels, were less likely to smoke, and had a higher alcohol consumption (P < 0.001). Physical activity MET values were highest in non-milk consumers (P = 0.001). The higher the milk consumption, the lower the rates of hypertension and diabetes (P = 0.001). The more frequent the milk consumption, the higher the daily total energy, carbohydrates, fat, protein, and calcium intakes (P < 0.001).

Table 1. General characteristics of study participants at baseline according to milk consumption in Ansan and Anseong cohort study.

| Characteristics | Milk consumption (serving/day)1) | P-value2)3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | < 1 | ≥ 1 | |||

| No. of participants | 3,112 (38.9) | 3,237 (40.4) | 1,660 (20.7) | ||

| Age (yrs) | 53.75 ± 9.16 | 50.56 ± 8.30 | 52.06 ± 8.68 | < 0.001 | |

| Sex | < 0.001 | ||||

| Men | 1,467 (47.1) | 1,686 (52.1) | 706 (42.5) | ||

| Women | 1,645 (52.9) | 1,551 (47.9) | 954 (57.5) | ||

| Residential area | < 0.001 | ||||

| Ansan (urban) | 1,270 (40.8) | 1,689 (52.2) | 892 (53.7) | ||

| Anseong (rural) | 1,842 (59.2) | 1,548 (47.8) | 768 (46.3) | ||

| Educational level | < 0.001 | ||||

| Elementary school graduation or lower | 1,344 (43.5) | 818 (25.3) | 468 (28.4) | ||

| Middle school graduation | 639 (20.7) | 781 (24.2) | 412 (25.0) | ||

| High school graduation | 798 (25.9) | 1,104 (34.2) | 520 (31.6) | ||

| College graduation or higher | 306 (9.9) | 524 (16.2) | 248 (15.0) | ||

| Household income (KRW/month) | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 1,000,000 | 1,344 (43.9) | 902 (28.3) | 514 (31.4) | ||

| 1,000,000–1,999,999 | 820 (26.8) | 991 (31.0) | 502 (30.6) | ||

| 2,000,000–3,999,999 | 704 (23.0) | 1,030 (32.3) | 484 (29.5) | ||

| ≥ 4,000,000 | 196 (6.4) | 269 (8.4) | 139 (8.5) | ||

| Current smoking status (yes) | 841 (27.2) | 831 (25.9) | 361 (21.9) | < 0.001 | |

| Current alcohol intake (yes) | 1,368 (44.2) | 1,685 (52.2) | 786 (47.5) | < 0.001 | |

| MET-h/d4) | 24.87 ± 15.55 | 23.42 ± 14.76 | 24.07 ± 14.81 | 0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.65 ± 3.18 | 24.61 ± 2.97 | 24.36 ± 3.07 | 0.018 | |

| History of disease (yes) | |||||

| Hypertension | 526 (16.9) | 414 (12.8) | 234 (14.1) | < 0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 173 (5.6) | 204 (6.3) | 139 (8.4) | 0.001 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 68 (2.2) | 84 (2.6) | 38 (2.3) | 0.544 | |

| Total energy intake (kcal/d) | 1,824.77 ± 591.74 | 1,957.73 ± 611.32 | 2,163.62 ± 670.32 | < 0.001 | |

| Carbohydrate intake (g/d) | 332.25 ± 105.77 | 343.38 ± 105.91 | 367.07 ± 115.18 | < 0.001 | |

| Fat intake (g/d) | 26.26 ± 16.56 | 33.09 ± 17.72 | 41.26 ± 20.03 | < 0.001 | |

| Protein intake (g/d) | 59.42 ± 24.47 | 66.67 ± 25.50 | 77.27 ± 28.27 | < 0.001 | |

| Ca intake (mg/d) | 363.75 ± 193.74 | 457.70 ± 216.81 | 717.46 ± 277.69 | < 0.001 | |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean ± SD.

MET, metabolic equivalent of task; BMI, body mass index.

1)One serving is equal to 200 mL of milk.

2)P-values are derived from χ2 test for categorical variables.

3)P for trends are derived from general linear model analysis for continuous variables.

4)Physical activity level is calculated as MET-h/day.

Characteristics of the subjects according to dairy product consumption

The general characteristics of the study participants according to dairy product consumption are presented in Table 2. Participants with higher dairy product consumptions tended to be younger, female, Ansan residents (urban) (P < 0.001). Compared with non-dairy product consumers, dairy product consumers had higher education and income levels (P < 0.001). Participants with higher levels of dairy product consumption were less likely to be current smokers (P < 0.001), consume alcohol (P = 0.019), and be physically active (P < 0.001). The more dairy products consumed, the less hypertension and diabetes reported (P = 0.001). The higher the dairy product consumption, the higher the daily total energy, carbohydrate, fat, protein, and calcium intakes (P < 0.001).

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of study participants at baseline according to dairy product consumption in Ansan and Anseong cohort study.

| Characteristics | Dairy product consumption (serving/day)1) | P-value2)3) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | < 0.5 | ≥ 0.5 | |||

| No. of participants | 2,369 (29.6) | 5,382 (67.2) | 258 (3.2) | ||

| Age (yrs) | 54.61 ± 8.88 | 51.04 ± 8.61 | 51.54 ± 8.42 | < 0.001 | |

| Sex | < 0.001 | ||||

| Men | 1,203 (50.8) | 2,557 (47.5) | 99 (38.4) | ||

| Women | 1,166 (49.2) | 2,825 (52.5) | 159 (61.6) | ||

| Residential area | < 0.001 | ||||

| Ansan (urban) | 803 (33.9) | 2,925 (54.3) | 123 (47.7) | ||

| Anseong (rural) | 1,566 (66.1) | 2,457 (45.7) | 135 (52.3) | ||

| Educational level | < 0.001 | ||||

| Elementary school graduation or lower | 1,042 (44.4) | 1,525 (28.5) | 63 (24.4) | ||

| Middle school graduation | 559 (23.8) | 1,204 (22.5) | 69 (26.7) | ||

| High school graduation | 570 (24.3) | 1,771 (33.1) | 81 (31.4) | ||

| College graduation or higher | 177 (7.5) | 856 (16.0) | 45 (17.4) | ||

| Household income (KRW/month) | < 0.001 | ||||

| < 1,000,000 | 1,098 (47.3) | 1,592 (29.9) | 70 (27.8) | ||

| 1,000,000–1,999,999 | 637 (27.4) | 1,592 (29.9) | 84 (33.3) | ||

| 2,000,000–3,999,999 | 480 (20.7) | 1,669 (31.4) | 69 (27.4) | ||

| ≥ 4,000,000 | 107 (4.6) | 468 (8.8) | 29 (11.5) | ||

| Current smoking status (yes) | 706 (30.1) | 1,273 (23.8) | 54 (21.0) | < 0.001 | |

| Current alcohol intake (yes) | 1,143 (48.5) | 2,595 (48.4) | 101 (39.5) | 0.019 | |

| MET-h/d4) | 26.79 ± 16.00 | 22.95 ± 14.52 | 23.82 ± 15.28 | < 0.001 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.45 ± 3.19 | 24.61 ± 3.02 | 24.69 ± 3.04 | 0.193 | |

| History of disease (yes) | |||||

| Hypertension | 401 (16.9) | 740 (13.7) | 33 (12.8) | 0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 193 (8.2) | 314 (5.8) | 9 (3.5) | < 0.001 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 52 (2.2) | 137 (2.5) | 1 (0.4) | 0.067 | |

| Total energy intake (kcal/d) | 1,810.94 ± 596.73 | 1,979.09 ± 606.60 | 2,580.98 ± 865.52 | < 0.001 | |

| Carbohydrate intake (g/d) | 328.33 ± 107.01 | 346.55 ± 105.00 | 433.75 ± 143.43 | < 0.001 | |

| Fat intake (g/d) | 26.41 ± 16.48 | 33.70 ± 17.93 | 51.91 ± 29.25 | < 0.001 | |

| Protein intake (g/d) | 59.34 ± 24.57 | 67.73 ± 25.60 | 92.62 ± 38.52 | < 0.001 | |

| Ca intake (mg/d) | 396.82 ± 229.69 | 490.99 ± 242.37 | 860.27 ± 388.15 | < 0.001 | |

Values are presented as number (%) or mean ± SD.

MET, metabolic equivalent of task; BMI, body mass index.

1)One serving was equal to 120 mL of yogurt, 120 g of ice-cream and 20 g of cheese.

2)P-values are derived from χ2 test for categorical variables.

3)P for trends are derived from general linear model analysis for continuous variables.

4)Physical activity level is calculated as MET-h/day.

Association between milk consumption and the risk of the cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence

The association between milk consumption and the risk of the cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence is presented in Table 3. Milk consumers (< 1 serving/day) exhibited a 19% lower risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence than non-milk consumers after adjusting for confounders such as age and sex (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.67–0.98). After adjusting for potential confounders, including age, sex, residential area, education level, household income, current smoking status, current alcohol intake, physical activity level, BMI, disease history, total energy intake, carbohydrate intake, fat intake, protein intake and Ca intake, individuals consuming < 1 serving of milk per day had a 23% lower risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence than non-milk consumers (HR, 0.77; 95% CI, 0.61–0.97).

Table 3. Hazard ratio (95% confidence intervals) for cardio-cerebrovascular diseases according to milk consumption in Ansan and Anseong cohort study.

| Characteristics | Milk consumption (serving/day) | P for trend | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | < 1 | ≥ 1 | ||

| No. of participants | 3,112 | 3,237 | 1,660 | |

| No. of cases | 248 | 189 | 115 | |

| Model 11) | 1.00 | 0.81 (0.67–0.98) | 0.93 (0.74–1.16) | 0.729 |

| Model 22) | 1.00 | 0.77 (0.61–0.97) | 0.93 (0.71–1.20) | 0.845 |

| Model 33) | 1.00 | 0.77 (0.61–0.97) | 0.85 (0.61–1.18) | 0.842 |

Values are presented as hazard ratio (95% confidence interval).

BMI, body mass index.

1)Model 1: age, sex.

2)Model 2: age sex, residential area, educational level, household income, current smoking status, current alcohol intake, physical activity, BMI, and history of diseases.

3)Model 3: age sex, residential area, educational level, household income, current smoking status, current alcohol intake, physical activity, BMI, history of diseases, total energy intake (kcal/day), carbohydrate, fat, protein intake (g/d) and ca intake (mg/d).

Association between dairy product consumption and the risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence

The association between dairy product consumption and the risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence are presented in Table 4. Yogurt consumers (≥ 0.5 servings/day) had a 24% lower risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence than non-yogurt consumers after adjusting for age and sex (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.59–0.96, P for trend = 0.030). After further adjusting for potential confounders, such as age, sex, residential area, education level, household income, current smoking status, current alcohol intake, physical activity level, BMI, disease history, total energy intake, carbohydrate intake, fat intake, protein intake and Ca intake, yogurt consumers (≥ 0.5 servings/day) exhibited a 29% lower risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence than non-yogurt consumers (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.53–0.96, P for trend = 0.049). No significant associations was noted between ice cream consumption and cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence in Models 1 and 2. However, in the fully-adjusted model, individuals consuming ≥ 0.5 servings/day of ice cream had a higher risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence than non-consumers (HR, 1.70; 95% CI, 1.01–2.88; P for trend = 0.070). No associations were found between cheese consumption and the risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence.

Table 4. Hazard ratio (95% confidence intervals) for cardio-cerebrovascular diseases according to yogurt, ice-cream, and cheese consumption in Ansan and Anseong cohort study.

| Characteristics | Dairy consumption (serving/day) | P for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | < 0.5 | ≥ 0.5 | |||

| Yogurt | |||||

| No. of participants | 3,352 | 3,017 | 1,640 | ||

| No. of cases | 260 | 203 | 89 | ||

| Model 11) | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.76–1.10) | 0.76 (0.59–0.96) | 0.030 | |

| Model 22) | 1.00 | 0.91 (0.73–1.13) | 0.71 (0.54–0.95) | 0.027 | |

| Model 33) | 1.00 | 0.92 (0.74–1.14) | 0.71 (0.53–0.96) | 0.049 | |

| Ice-cream | |||||

| No. of participants | 4,617 | 3,093 | 299 | ||

| No. of cases | 346 | 184 | 22 | ||

| Model 11) | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.79–1.14) | 1.22 (0.79–1.89) | 0.490 | |

| Model 22) | 1.00 | 0.95 (0.76–1.18) | 1.47 (0.90–2.38) | 0.192 | |

| Model 33) | 1.00 | 0.97 (0.78–1.21) | 1.70 (1.01–2.88) | 0.070 | |

| Cheese | |||||

| No. of participants | 6,921 | 977 | 111 | ||

| No. of cases | 481 | 62 | 9 | ||

| Model 11) | 1.00 | 1.10 (0.84–1.44) | 1.28 (0.66–2.48) | 0.432 | |

| Model 22) | 1.00 | 1.06 (0.77–1.45) | 1.31 (0.61–2.80) | 0.472 | |

| Model 33) | 1.00 | 1.11 (0.80–1.53) | 1.36 (0.63–2.93) | 0.411 | |

Values are presented as hazard ratio (95% confidence interval).

BMI, body mass index.

1)Model 1: age, sex.

2)Model 2: age sex, residential area, educational level, household income, current smoking status, current alcohol intake, physical activity, BMI, and history of diseases.

3)Model 3: age sex, residential area, educational level, household income, current smoking status, current alcohol intake, physical activity, BMI, history of diseases, total energy intake (kcal/day), carbohydrate, fat, protein intake (g/d) and ca intake (mg/d).

DISCUSSION

In this community-based prospective study involving a 96.5-person-month follow-up period, baseline data regarding milk and dairy product consumption and cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence were collected from the KoGES. The results revealed that Korean adults consumed milk (< 1 serving/day) and yogurt (≥ 0.5 servings/day) exhibited a lower cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence than non-consumers.

Participants who consumed more milk and dairy products were younger and had a higher proportion of women. Middle-aged and older people are most likely to consume milk for health benefits [30]. Middle-aged women present a greater interest in nutrition and diet [31]. The higher the education and income levels of participants, the greater their consumption of milk and dairy products. Those of higher socioeconomic status consumed more milk and dairy products, exhibiting consistency with the results of a previous community-based cohort study [26]. This study demonstrated that the lower the METs, that is the physical activity index, the lower the consumption of milk and dairy products. Similar results were yielded by a study that utilized KoGES data to elucidate the relationship between dairy product consumption and metabolic syndrome [26]. Since this community-based cohort used MET values, which indicate physical activity intensity rather than regular physical exercise [20], its results suggest that physical activity intensity was low during the investigation period.

The lower the prevalence of hypertension, the higher the consumption of milk and dairy products; nevertheless, no significant difference in the prevalence of dyslipidemia was observed. However, the higher the proportion of people with diabetes, the higher the milk consumption, suggesting that whey in milk is insulinotropic and potentially increases the insulin index, which may interfere with insulin secretion [32].

In this study, the association between dairy product consumption and cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence varied according to dairy product type. The incidence by milk consumption (< 1 serving/day), after adjusting for sex, age, demographic characteristics and nutritional factors, decreased significantly by 23%. The incidence by yogurt consumption (≥ 0.5 servings/day) decreased by 29%; however, that by cheese consumption did not display a significant reduction. Moreover, the incidence according to ice cream consumption (≥ 0.5 servings/day) was 70% higher than that in non-consumers after adjusting all factors.

According to the 2020 Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans, 100 g of milk contains 113 mg of calcium and 2.2 g of saturated fatty acids, 100 g of yogurt contains 141 mg of calcium and 2.5 g of saturated fatty acids, and 100 g of cheese contains 626 mg of calcium and 14.5 g of saturated fatty acids [21]. However, 100 g of ice cream contains 80 mg of calcium and 5.3 g of saturated fatty acids. It has less calcium than twice as much saturated fatty acids as milk and yogurt. On comparing nutrient content per serving size presented in this study, calcium content had the following order from highest to lowest; milk, yogurt, cheese, and ice cream, while saturated fatty acid content had the following order; ice cream, milk, yogurt, and cheese. The higher the calcium content and the lower the saturated fatty acid content per serving, the lower the risk of disease incidence, possibly explaining why milk and yogurt consumption lowers the risk of cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence.

The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Cohort Study reported that fermented dairy products reduced the risk of stroke. The consumption of low-fat dairy products also reduced coronary heart disease risk in normotensive patients [33]. Yogurt consumption was inversely associated with the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in patients with hypertension [34]. A Swedish Malmo Diet and Cancer Cohort Study revealed that fermented milk consumption (including yogurt) reduced the incidence of cardiovascular disease [35]. The Swedish Mammography Cohort Study also reported that the consumption of all dairy products, including milk, reduced the incidence of myocardial infarction [36]. According to the Golestan Cohort Study in Iran, total dairy product consumption was associated with lower risks of all and cardiovascular mortality [37]. A Japanese cohort study using the NIPPON DATA80 also demonstrated that women with a lower consumption of milk and dairy products had an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, coronary artery disease, and stroke mortality [38]. A meta-analysis of Chinese cohort studies found the consumption of low-fat dairy products and cheese to have a negative association with coronary artery disease or stroke [39]. The consumption of fermented dairy products and yogurt was inversely associated with cardiovascular disease risk among middle-aged women in the Australian Longitudinal Study [40]. This research and the present study suggest that milk and dairy product consumption effectively reduces cardio-cerebrovascular disease risk.

Although a negative perception of milk and dairy products generally exists, certain studies have proposed that the dairy fat contained in milk and dairy products is not associated with cardiovascular disease risk [41]. According to a cohort study of adults in the United States, milk fat reduces cardiovascular disease risk [42,43]. Fermented dairy products, such as yogurt and cheese, have a probiotic effect and do not negatively influence blood lipids [44]. Some studies have suggested that reducing saturated fatty acid intake by limiting dairy product consumption could have rather negative effects [45].

Studies confirming alterations in cardiovascular disease biomarkers between low-fat or fermented dairy products and non-fermented dairy products in adults reveal that non-fermented dairy products have more than 3 times the saturated fatty acid content of low-fat dairy products [46]. In this study, interleukin-6, an inflammation marker, was found to be higher in non-fermented dairy products (cream and ice cream) than in low-fat dairy products. Non-fermented dairy products contained a higher saturated fat content and increased cardiovascular disease risk more than low-fat dairy products. The increase in cardio-cerebrovascular disease incidence in this study might have been due to the consumption of ice cream, which is high in saturated fat. In addition, according to the 2005–2007 MONA LISA multicenter French study of middle-aged and older people, the consumption of low-fat dairy products exhibited an inverse correlation with low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels, and a higher consumption of low-fat dairy products reduced cardiovascular mortality scores [47].

In this study, the higher the proportion of women, the higher the consumption of milk and dairy products, and the factors that influence the relationship between disease risk and diet may differ by sex. In particular, middle-aged women are affected by sex hormones and physical and psychological changes that may increase cardio-cerebrovascular disease risk [48]. However, the possibility of result bias cannot be ruled out since both sexes were included in this study. Excluding the possibility of sex as an effect modifier is difficult, therefore, sex-stratification analysis is warranted in future studies. This may require sex-specific studies in the future.

This study has several limitations. Cardio-cerebrovascular disease included diverse conditions, such as myocardial infarction and stroke. Hence, results might have been influenced by the different mechanisms and causes of the various cardio-cerebrovascular diseases. Another limitation to this study might have been self-reported disease diagnosis based on biennial follow-up examination records. Although a previous study reported a degree of agreement between the self-reported disease diagnosis and medical records of up to 93% [25], only 30 cases were studied, thereby compromising validity. Additionally, follow-up might have been rendered impossible by severe disease progression during the follow-up period, thus preventing study participation. In such cases, generalizing the results is complicated by increased loss of follow-up owing to actual disease dropout. Furthermore, the FFQ used in this study did not consider the types and contents of non-fat, low-fat, and whole-fat in commercial milk. The effects of fatty acids may vary depending on butterfat consumption, and studies have shown that components such as short-chain saturated fatty acids, long-chain saturated fatty acids, and unsaturated fatty acids differ considerably according to milk type (cow or goat). Therefore, future investigations must subcategorize the fat content of milk and dairy products. Finally, the present study was exclusively conducted only in 2 areas (Ansan and Anseong); thus, it may not be generalizable to the wider population.

Despite the foregoing limitations, this was a large-scale epidemiological study that investigated the association of milk and dairy product consumption with incident cardio-cerebrovascular disease. Its findings suggest that the consumption of less than one serving of milk and dairy products may prevent cardio-cerebrovascular disease in middle-aged and older Koreans. Randomized controlled trials are warranted to confirm these results and clarify the beneficial effects of milk and dairy product consumption on cardio-cerebrovascular disease.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Data in this study were from the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES; 4851-302), National Institute of Health Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency, Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by Korea Milk Marketing Board.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no potential conflicts of interests.

- Conceptualization: Jeong Y, Kim Y.

- Methodology: Jeong Y, Lee KW, Kim H, Kim Y.

- Funding acquisition: Kim Y.

- Formal analysis: Jeong Y.

- Investigation: Jeong Y, Lee KW, Kim Y.

- Supervision: Kim Y.

- Writing - original draft: Jeong Y.

- Writing - review & editing: Lee KW, Kim H, Kim Y.

References

- 1.Smith SC., Jr Current and future directions of cardiovascular risk prediction. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:28A–32A. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. The top 10 causes of death 2020 [Internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. [cited 2022 March 23]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death. [Google Scholar]

- 3.GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388:1459–1544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atkins JL, Whincup PH, Morris RW, Lennon LT, Papacosta O, Wannamethee SG. High diet quality is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in older men. J Nutr. 2014;144:673–680. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.186486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.German JB, Gibson RA, Krauss RM, Nestel P, Lamarche B, van Staveren WA, Steijns JM, de Groot LC, Lock AL, Destaillats F. A reappraisal of the impact of dairy foods and milk fat on cardiovascular disease risk. Eur J Nutr. 2009;48:191–203. doi: 10.1007/s00394-009-0002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mozaffarian D, Wu JH. Flavonoids, dairy foods, and cardiovascular and metabolic health: a review of emerging biologic pathways. Circ Res. 2018;122:369–384. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.309008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kong SH, Kim JH, Hong AR, Cho NH, Shin CS. Dietary calcium intake and risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and fracture in a population with low calcium intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:27–34. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.148171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Goede J, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Pan A, Gijsbers L, Geleijnse JM. Dairy consumption and risk of stroke: a systematic review and updated dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002787. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elwood PC, Pickering JE, Hughes J, Fehily AM, Ness AR. Milk drinking, ischaemic heart disease and ischaemic stroke II. Evidence from cohort studies. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:718–724. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gholami F, Khoramdad M, Esmailnasab N, Moradi G, Nouri B, Safiri S, Alimohamadi Y. The effect of dairy consumption on the prevention of cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2017;9:1–11. doi: 10.15171/jcvtr.2017.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guo J, Astrup A, Lovegrove JA, Gijsbers L, Givens DI, Soedamah-Muthu SS. Milk and dairy consumption and risk of cardiovascular diseases and all-cause mortality: dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:269–287. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0243-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwon HT, Lee CM, Park JH, Ko JA, Seong EJ, Park MS, Cho B. Milk intake and its association with metabolic syndrome in Korean: analysis of the third Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES III) J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:1473–1479. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2010.25.10.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon S, Lee JS. Study on relationship between milk intake and prevalence rates of chronic diseases in adults based on 5th and 6th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. J Nutr Health. 2017;50:158–170. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ha AW, Kim WK, Kim SH. Intakes of milk and soymilk and cardiovascular disease risk in Korean adults: a study based on the 2012~2016 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr. 2023;52:522–530. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uthman OA, Hartley L, Rees K, Taylor F, Ebrahim S, Clarke A. Multiple risk factor interventions for primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD011163. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011163.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J, Wu Z, Lin Z, Wang W, Wan R, Liu T. Association of milk consumption with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular outcomes: a UK Biobank based large population cohort study. J Transl Med. 2023;21:130. doi: 10.1186/s12967-023-03980-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin S, Lee HW, Kim CE, Lim J, Lee JK, Kang D. Association between milk consumption and metabolic syndrome among Korean adults: results from the health examinees study. Nutrients. 2017;9:1102. doi: 10.3390/nu9101102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim Y, Han BG KoGES group. Cohort profile: the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) consortium. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:1350. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyx105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahn Y, Kwon E, Shim JE, Park MK, Joo Y, Kimm K, Park C, Kim DH. Validation and reproducibility of food frequency questionnaire for Korean genome epidemiologic study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61:1435–1441. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korean National Institute of Health. Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study: KoGES [Internet] Cheongju: Korean National Institute of Health; 2022. [cited 2022 March 23]. Available from: https://nih.go.kr/ko/main/contents.do?menuNo=300583. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministry of Health and Welfare; The Korean Nutrition Society. Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans 2020. Sejong: The Korean Nutrition Society; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O’Brien WL, Bassett DR, Jr, Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:S498–S504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park SJ, Lee GS, Lee HJ. The effects of the obesity and physical activity on the prevalence of hypertension in Korean adults. J East Asian Soc Diet Life. 2015;25:432–439. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendis S, Puska P, Norrving B World Health Organization. Global Atlas on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baik I, Cho NH, Kim SH, Shin C. Dietary information improves cardiovascular disease risk prediction models. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67:25–30. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim D, Kim J. Dairy consumption is associated with a lower incidence of the metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and older Korean adults: the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) Br J Nutr. 2017;117:148–160. doi: 10.1017/S000711451600444X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee J, Lee JE, Kim Y. Relationship between coffee consumption and stroke risk in Korean population: the Health Examinees (HEXA) Study. Nutr J. 2017;16:7. doi: 10.1186/s12937-017-0232-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee J, Kim Y. Association between green tea consumption and risk of stroke in middle-aged and older Korean men: the health examinees (HEXA) study. Prev Nutr Food Sci. 2019;24:24–31. doi: 10.3746/pnf.2019.24.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park K, Son J, Jang J, Kang R, Chung HK, Lee KW, Lee SM, Lim H, Shin MJ. Unprocessed meat consumption and incident cardiovascular diseases in Korean adults: the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) Nutrients. 2017;9:498. doi: 10.3390/nu9050498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim JH, Kyung MS, Min SH, Lee MH. Milk intake patterns with lactose and milk fat in Korean male adults. Korean J Community Nutr. 2018;23:488–495. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim MH, Lee HJ, Kim MJ, Lee KH. The relationship between intake of health foods and dietary behavior in middle-aged women. Korean J Community Nutr. 2014;19:436–447. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfeuffer M, Schrezenmeir J. Milk and the metabolic syndrome. Obes Rev. 2007;8:109–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalmeijer GW, Struijk EA, van der Schouw YT, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Verschuren WM, Boer JM, Geleijnse JM, Beulens JW. Dairy intake and coronary heart disease or stroke--a population-based cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:925–929. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buendia JR, Li Y, Hu FB, Cabral HJ, Bradlee ML, Quatromoni PA, Singer MR, Curhan GC, Moore LL. Regular yogurt intake and risk of cardiovascular disease among hypertensive adults. Am J Hypertens. 2018;31:557–565. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpx220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sonestedt E, Wirfält E, Wallström P, Gullberg B, Orho-Melander M, Hedblad B. Dairy products and its association with incidence of cardiovascular disease: the Malmö diet and cancer cohort. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26:609–618. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9589-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patterson E, Larsson SC, Wolk A, Åkesson A. Association between dairy food consumption and risk of myocardial infarction in women differs by type of dairy food. J Nutr. 2013;143:74–79. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.166330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Farvid MS, Malekshah AF, Pourshams A, Poustchi H, Sepanlou SG, Sharafkhah M, Khoshnia M, Farvid M, Abnet CC, Kamangar F, et al. Dairy food intake and all-cause, cardiovascular disease, and cancer mortality: the Golestan Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185:697–711. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kondo I, Ojima T, Nakamura M, Hayasaka S, Hozawa A, Saitoh S, Ohnishi H, Akasaka H, Hayakawa T, Murakami Y, et al. Consumption of dairy products and death from cardiovascular disease in the Japanese general population: the NIPPON DATA80. J Epidemiol. 2013;23:47–54. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20120054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qin LQ, Xu JY, Han SF, Zhang ZL, Zhao YY, Szeto IM. Dairy consumption and risk of cardiovascular disease: an updated meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2015;24:90–100. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2015.24.1.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buziau AM, Soedamah-Muthu SS, Geleijnse JM, Mishra GD. Total fermented dairy food intake is inversely associated with cardiovascular disease risk in women. J Nutr. 2019;149:1797–1804. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxz128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liang J, Zhou Q, Kwame Amakye W, Su Y, Zhang Z. Biomarkers of dairy fat intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta analysis of prospective studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58:1122–1130. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2016.1242114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen M, Li Y, Sun Q, Pan A, Manson JE, Rexrode KM, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Hu FB. Dairy fat and risk of cardiovascular disease in 3 cohorts of US adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104:1209–1217. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.116.134460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Oliveira Otto MC, Mozaffarian D, Kromhout D, Bertoni AG, Sibley CT, Jacobs DR, Jr, Nettleton JA. Dietary intake of saturated fat by food source and incident cardiovascular disease: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96:397–404. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.037770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Astrup A. Yogurt and dairy product consumption to prevent cardiometabolic diseases: epidemiologic and experimental studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:1235S–42S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.073015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lovegrove JA, Givens DI. Dairy food products: good or bad for cardiometabolic disease? Nutr Res Rev. 2016;29:249–267. doi: 10.1017/S0954422416000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nestel PJ, Mellett N, Pally S, Wong G, Barlow CK, Croft K, Mori TA, Meikle PJ. Effects of low-fat or full-fat fermented and non-fermented dairy foods on selected cardiovascular biomarkers in overweight adults. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:2242–2249. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513001621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huo Yung Kai S, Bongard V, Simon C, Ruidavets JB, Arveiler D, Dallongeville J, Wagner A, Amouyel P, Ferrières J. Low-fat and high-fat dairy products are differently related to blood lipids and cardiovascular risk score. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:1557–1567. doi: 10.1177/2047487313503283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee HJ, Lee KH. Field application and evaluation of health status assessment tool based on dietary patterns for middle-aged women. Korean J Community Nutr. 2018;23:277–288. [Google Scholar]