Keywords: chronic hemodialysis; health equity, diversity, and inclusion; patient-centered care; social determinants of health

Abstract

Key Points

Food insecurity and housing instability may affect dialysis outcomes through health behaviors like treatment adherence and their effect on access to transplantation or home dialysis therapies.

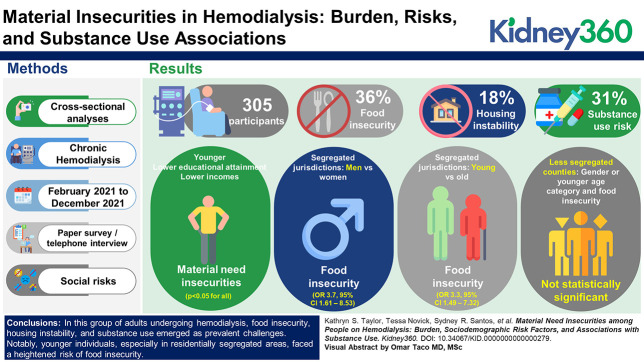

People on hemodialysis who were younger, with less educational attainment, with lower incomes, or experiencing financial strain were more likely to experience material need insecurities.

Participant race was not associated with material need insecurities, although residential segregation moderated associations between age, sex, and food insecurity.

Background

Despite their relevance to health outcomes, reports of food insecurity and housing instability rates among adults on hemodialysis are limited. Their relation to sociodemographic and behavioral factors are unknown for this population.

Methods

We enrolled a convenience sample of people receiving hemodialysis at Baltimore and Washington, DC metropolitan area facilities. Participants completed measures of socioeconomic position, food insecurity, housing instability, and substance use disorder. We cross-referenced participant and facility zip codes with measures of area poverty and residential segregation. We examined associations between individual-level and area-level sociodemographic characteristics, food insecurity, and housing instability using multivariable logistic regression models.

Results

Of the 305 participants who completed study surveys, 57% were men and 70% were Black, and the mean age was 60 years. Thirty-six percent of the sample reported food insecurity, 18% reported housing instability, and 31% reported moderate or high-risk substance use. People on hemodialysis who were younger, with lower educational attainment, with lower incomes, or experiencing financial strain were more likely to have material need insecurities (P < 0.05 for all). Among participants living in segregated jurisdictions, men had increased odds of food insecurity compared with women (odds ratio 3.7; 95% confidence interval, 1.61 to 8.53); younger participants (age <55 years) had increased odds of food insecurity compared with older participants (odds ratio 3.3; 95% confidence interval, 1.49 to 7.32). Associations between sex or younger age category and food insecurity were not statistically significant in less segregated counties (P interaction for residential segregation×sex: P = 0.006; residential segregation×younger age category: P = 0.12).

Conclusions

Food insecurity, housing instability, and substance use were common among this sample of adults on hemodialysis. Younger adults on hemodialysis, particularly those living in residentially segregated jurisdictions, were at increased risk for food insecurity. Future research should examine whether material need insecurities perpetuate disparities in dialysis outcomes.

Podcast

This article contains a podcast at https://dts.podtrac.com/redirect.mp3/www.asn-online.org/media/podcast/K360/2023_12_01_KID0000000000000279.mp3

Introduction

Food insecurity and housing instability are material need insecurities associated with worse chronic disease outcomes1 including progression of chronic kidney disease.2,3 Food insecurity is defined as a limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods4 and housing instability is characterized by housing that is high cost, overcrowded, or dangerous.5 Food insecurity and housing instability may be persistent but are often transient,6,7 resulting from stressors to household budgets as seen at the start of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.8 For people with ESKD, hemodialysis may be another such stressor because of employment and income loss related to thrice weekly treatments.9 Food insecurity and housing instability may affect dialysis outcomes through health behaviors like medication, treatment, or dietary adherence as well as through their effect on access to transplantation or home dialysis therapies.10,11 Therefore, material need insecurities are clinically relevant across the trajectory of chronic kidney disease, yet previous reports of food insecurity and housing instability in the adult ESKD population are limited.12

Identification of sociodemographic risk factors for food insecurity and housing instability among people on hemodialysis can inform targeted allocation of resources to high-risk groups. However, these risk factors remain unclear. In the US general population, Black and Hispanic households and households with incomes below 185% of the federal poverty level are more likely to experience food insecurity.13 US Census Household Pulse Surveys indicate that a higher proportion of Black and Hispanic respondents faced challenges paying for housing since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.14 People on hemodialysis face additional risk factors for food and housing insecurity, and hemodialysis itself might increase risk for unmet social needs. Moreover, area-level variables, such as neighborhood poverty or residential segregation, may contextualize individual-level sociodemographic differences in material need insecurities.15,16

Finally, material need insecurities and substance use co-occur and may be mutually reinforcing.17 Research with other populations (e.g., people living with HIV,18 pregnant women,19 veterans20) has quantified associations between substance use and material need insecurities and examined the moderating effect of food insecurity on associations between substance use and health behaviors.21 Although a limited body of research has explicitly studied people on hemodialysis who use substances,22 associations between substance use and material need insecurities among people on hemodialysis have not been established. If substance use and material need insecurities co-occur, interventions should address these issues together instead of in isolation.

Therefore, important gaps exist in our understanding of risk factors for clinically relevant material need insecurities among people on hemodialysis. We aimed to address these gaps by (1) quantifying the burden of food insecurity and housing instability, (2) identifying individual and area-level sociodemographic risk factors for food insecurity and housing instability, and (3) examining associations between food insecurity, housing instability, and substance use among people on hemodialysis.

Methods

We report cross-sectional analyses of baseline survey data from a cohort of people on hemodialysis aimed at elucidating the relation of social risks and clinical outcomes. People were eligible for enrollment if they were age 18 years or older, had been on chronic hemodialysis for at least 3 months, and could provide a high-level explanation of study purpose and procedures after informed consent. We enrolled a convenience sample of people receiving hemodialysis at Baltimore and Washington, DC metropolitan area facilities within the same dialysis organization. In early 2021 because of operational changes within dialysis facilities in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, we identified eligible people via nephrologist referral. After participating facilities completed COVID-19 vaccination campaigns in Spring 2021, a study team member conducted eligibility screening and informed consent in the dialysis facility waiting room before hemodialysis treatment with people who verbalized interest in participating in the study. People self-reported their age and length of time on chronic hemodialysis for eligibility screening. We collected survey data from February 2021 to December 2021. Participants could complete a paper survey independently during hemodialysis treatment or schedule a telephone interview with a trained study team member. Surveys were available in English or Spanish. Participants received a $20 Visa gift card as remuneration.

Survey data included participant zip code, self-reported race and other demographics, and indicators of socioeconomic status (e.g., education level and income). To assess financial strain, one item asked participants how their finances usually worked out at the end of the month: some money left over, just enough to make ends meet, or not enough to make ends meet. We cross-referenced participant zip codes with area-level poverty rates from the 2020 American Community Survey. Finally, we obtained county-level Dissimilarity Index scores from County Health Rankings and Roadmaps (countyhealthrankings.org). The Dissimilarity Index is a measure of Black-White residential segregation and represents the proportion of the population that would have to relocate within the county for the distribution of Black and White residents to become even.

We assessed participants' level of food security using the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) Adult Food Security Survey Module23; housing instability with a two-item screener developed by the US Department of Veterans Affairs24; and substance use disorder with the World Health Organization's Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST).25 We selected validated measures that clinicians could use for screening in a health care setting. Each measure demonstrated excellent internal consistency. Cronbach alpha for the USDA Adult Food Security Survey Module was 0.92 in the sample. The KR-20 coefficient for the dichotomous US Department of Veterans Affairs screener was 0.9. Cronbach alphas for each of the nine substance risk scales in the ASSIST ranged from 0.73 to 0.9 (Survey instrument available in Supplemental Materials).

Two study team members entered survey data into separate Excel spreadsheets to ensure data entry accuracy. A third team member resolved discrepancies in data entry comparing entries to paper surveys. The Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board and the dialysis organization's research protocol review committee approved the study.

Statistical Methods

We examined descriptive statistics for all variables. We combined categorical data into groups that were conceptually similar (e.g., cohabitating and married). We calculated scores for food insecurity and substance use risk from the mean of nonmissing responses if participants answered at least 70% of scale items. Distributions for food insecurity and substance use risk scores were right skewed. We used cutoffs from the USDA to generate a binary food insecurity variable categorizing participants with marginal, low, or very low food security as food insecure. We applied cutoffs from the World Health Organization to create categorical variables for low, moderate, or high-risk use of any of the nine substances included in the ASSIST, except for alcohol use. The World Health Organization categorizes substance risk scores >3 as moderate risk for all substances except alcohol, which has a cutoff for moderate risk at 11. We coded alcohol risk scores >3 as moderate risk given that even lower frequency alcohol use may be harmful to patients on hemodialysis. We created a binary variable for a negative or positive screen for housing instability as described by the US Department of Veterans Affairs.24 Finally, we generated binary area-level variables for poverty rate and residential segregation using median values as cut points.

We conducted logistic regression to examine associations between individual-level sociodemographic characteristics (independent variables) and food insecurity or housing instability (dependent variables). For area-level predictors, we used mixed-effects logistic regression models with poverty level or residential segregation as independent variables and food insecurity or housing instability as dependent variables. We then generated multivariate models adjusting for age and sex. We also explored interactions between individual and area-level risk factors for food insecurity. Specifically, we generated bivariate mixed-effects regression models with interaction terms for residential segregation×sex or residential segregation×younger age category (<55 years) as the independent variable and food insecurity as the dependent variable. Finally, we conducted chi-squared tests to examine associations between food insecurity or housing instability and substance use risk scores. We used Stata version 17.0 to conduct statistical analyses.

Results

We enrolled 322 participants across 17 dialysis facilities. A total of 305 participants completed the survey (95% response rate). We considered surveys incomplete if the study team was unable to contact enrolled participants for telephone interviews within three attempts. Less than 5% of participants had a missing food insecurity score. The rate of missing substance risk scores varied by substance and ranged from 3% for amphetamine, inhalants, or sedatives use to 15% for alcohol use. Participants with missing alcohol use data were dropped from substance use analyses. Less than 2% of the sample had a missing homelessness risk screener.

The mean age of participants was 60 years (range 27–86 years). Men comprised 57% of the sample, and 70% of the sample identified their race as Black while 6% of the sample identified their ethnicity as Hispanic. Of the 293 (96%) participants who received a food insecurity score, 105 (36%) reported food insecurity in the previous 12 months (Table 1). Specifically, 39 (13%) reported marginal food security, 37 (13%) reported low food security, and 29 (10%) reported very low food security. Of the 300 (98%) participants who completed the two-item screener for housing instability, 54 (18%) reported they “did not have a home of their own where they felt safe in the past 90 days or were worried that they would not have one in the next 90 days. Overall, 32 (11%) participants reported both material needs insecurities: 67% of participants who screened positive for housing instability also reported food insecurity, and 31% of those reporting food insecurity also screened positive for housing instability.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients on hemodialysis by food insecurity and housing instability

| Sample Characteristic | Total Samplea No. (%) |

Food Security | Housing Instability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High No. (%)b |

Marginal, Low, or Very Low No. (%) |

Negative Screen No. (%) |

Positive Screen No. (%) |

||

| Total sample | 305 | 188 (64) | 105 (36) | 246 (82) | 54 (18) |

| Age group (yr) | |||||

| 67–86 | 98 (33) | 75 (77) | 22 (23) | 85 (89) | 10 (11) |

| 55–66 | 99 (33) | 60 (65) | 32 (35) | 77 (79) | 21 (21) |

| 27–54 | 99 (33) | 52 (54) | 45 (47) | 80 (81) | 19 (19) |

| Sex c | |||||

| Female | 127 (42) | 86 (70) | 37 (30) | 103 (82) | 22 (18) |

| Male | 173 (58) | 100 (60) | 66 (40) | 140 (82) | 30 (18) |

| Race | |||||

| White | 55 (19) | 39 (72) | 15 (28) | 48 (87) | 7 (13) |

| Black | 213 (73) | 128 (62) | 77 (38) | 171 (82) | 8 (18) |

| Asian, AIAN, NHPI, or >1 race | 25 (8) | 15 (68) | 7 (32) | 18 (75) | 6 (25) |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | 280 (94) | 178 (66) | 93 (34) | 227 (83) | 48 (17) |

| Hispanic | 17 (6) | 6 (40) | 9 (60) | 12 (71) | 5 (29) |

| Income | |||||

| ≥$25,000/yr | 91 (45) | 73 (84) | 14 (16) | 79 (88) | 11 (12) |

| <$25,000/yr | 109 (55) | 57 (53) | 50 (47) | 82 (77) | 25 (23) |

| Financial strain | |||||

| Some money left over | 100 (39) | 84 (84) | 16 (16) | 93 (93) | 7 (7) |

| Just enough to make ends meet | 88 (35) | 55 (65) | 30 (35) | 74 (84) | 14 (16) |

| Not enough to make ends meet | 67 (26) | 22 (35) | 40 (65) | 41 (63) | 24 (37) |

| Education level | |||||

| Post-high school | 61 (20) | 74 (68) | 35 (32) | 98 (89) | 12 (11) |

| High school | 131 (43) | 89 (69) | 40 (31) | 105 (80) | 26 (20) |

| Less than high school | 113 (37) | 25 (45) | 30 (55) | 43 (73) | 16 (27) |

| Marital status | |||||

| Cohabitating or married | 105 (36) | 74 (73) | 28 (27) | 90 (87) | 14 (13) |

| Divorced, widowed, or separated | 97 (33) | 54 (56) | 42 (44) | 77 (80) | 19 (20) |

| Never married | 90 (31) | 54 (64) | 31 (36) | 70 (80) | 18 (20) |

AIAN, American Indian and Alaska Native; NHPI, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander.

Cell totals may not add to event total because of missing sample characteristics data.

All percentages correspond to row totals.

We report gender subgroups with >10 participants.

Younger age was a risk factor for food insecurity and housing instability (Table 2). Participants in the youngest age group (age 27–54 years) had increased odds of food insecurity compared with participants in the oldest age group (age 67–86 years) after adjusting for sex (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 2.89; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.55 to 5.41). Participants in the middle age group (age 55–66 years) had increased odds of housing instability compared with the oldest age group (aOR 2.35; 95% CI, 1.04 to 5.31). Male participants had a 50% increased odds of food insecurity after adjusting for age, but this association did not reach statistical significance (aOR 1.53; 95% CI, 0.92 to 2.55). There was no association between sex and housing instability (odds ratio [OR] 1; 95% CI, 0.54 to 1.86). Compared with White participants, Black participants had a 60% increased odds of food insecurity after adjusting for age and sex, but this association did not reach statistical significance (aOR 1.59; 95% CI, 0.8 to 3.15). A small number of Hispanic participants were enrolled in the study (n=17). Although Hispanic ethnicity was strongly associated with food insecurity after adjusting for age and sex, the association did not reach statistical significance (aOR 2.14; 95% CI, 0.7 to 6.5).

Table 2.

Adjusted odds ratiosa for food insecurity or housing instability

| Sample Characteristic | Food Insecurity n=105 |

Housing Instability n=54 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P Value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

| Age group (yr) | ||||||

| 67–86 (n=99) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||

| 55–66 (n=99) | 1.82 | 0.96 to 3.47 | 0.07 | 2.35c | 1.04 to 5.31c | 0.04c |

| 27–54 (n=98) | 2.89c | 1.55 to 5.41c | 0.001c | 2.07 | 0.91 to 4.74 | 0.08 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female (n=127) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||

| Male (n=173) | 1.53 | 0.92 to 2.55 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.54 to 1.86 | 1 |

| Race | ||||||

| White (n=55) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||

| Black (n=213) | 1.59 | 0.8 to 3.15 | 0.19 | 1.38 | 0.58 to 3.33 | 0.47 |

| Asian, AIAN, NHPI, or >1 race (n=25) | 1.28 | 0.43 to 3.85 | 0.66 | 2.21 | 0.65 to 7.5 | 0.21 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic (n=280) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||

| Hispanic (n=17) | 2.14 | 0.71 to 6.5 | 0.18 | 1.02 | 0.27 to 3.84 | 0.97 |

| Income | ||||||

| ≥$25,000/yr (n=109) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||

| <$25,000/yr (n=91) | 4.65c | 2.32 to 9.34c | <0.001c | 2.2c | 1.01 to 4.79c | 0.05c |

| Financial strain | ||||||

| Some money left over (n=100) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||

| Just enough to make ends meet (n=88) | 2.97c | 1.44 to 6.11c | 0.003c | 2.47 | 0.94 to 6.49 | 0.07 |

| Not enough to make ends meet (n=67) | 8.49c | 3.9 to 18.49c | <0.001c | 6.52c | 2.51 to 16.89c | <0.001c |

| Education level | ||||||

| Post-high school (n=61) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||

| High school (n=131) | 0.92 | 0.52 to 1.62 | 0.76 | 2.06 | 0.96 to 4.43 | 0.07 |

| Less than high school (n=113) | 2.24 | 1.1 to 4.54c | 0.03c | 3.13c | 1.3 to 7.53c | 0.01c |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Cohabitating or married (n=105) | (ref) | 1.38 to 5.01c | (ref) | |||

| Divorced, widowed, or separated (n=97) | 2.63c | 0.73 to 2.75 | 0.003c | 1.64 | 0.74 to 3.63 | 0.22 |

| Never married (n=90) | 1.42 | 0.3 | 1.51 | 0.68 to 3.32 | 0.31 | |

| % Below FPL b | ||||||

| 0%–12% (n=146) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||

| 12.5%–36.3% (n=145) | 1.56 | 0.94 to 2.61 | 0.09 | 1.2 | 0.51 to 2.81 | 0.68 |

| Dissimilarity index b | ||||||

| Below median (n=185) | (ref) | (ref) | ||||

| Above median (n=120) | 1.52 | 0.91 to 2.54 | 0.11 | 1.28 | 0.66 to 2.48 | 0.47 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; AIAN, American Indian and Alaska Native; NHPI, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander; FPL, Federal Poverty Level.

Multivariate logistic regression model adjusted for age and sex except when independent variable in the model.

Multivariate mixed-effects logistic regression model adjusted for age and sex.

p< 0.05

Income, financial strain, and educational level were risk factors for food insecurity and housing instability. Participants who did not graduate from high school had increased odds of food insecurity and housing instability compared with participants with at least some college education (aOR 2.24; 95% CI, 1.1 to 4.54 and aOR 3.13; 95% CI, 1.3 to 7.53, respectively). Marital status was associated with food insecurity but not housing instability. Compared with participants who were married or cohabitating, participants who were divorced, separated, or widowed had a 2.5-fold increase in food insecurity (aOR 2.63; 95% CI, 1.38 to 5.01).

Black participants were more likely to live in zip codes with higher poverty rates and in counties with a Dissimilarity Index score above the median of 61 (henceforth, more segregated). For example, 38% of Black participants lived in zip codes with the highest poverty rates, compared with 16% of White participants. In unadjusted analyses, neighborhood poverty and residential segregation were associated with food insecurity. Participants living in high poverty zip codes had a 80% increased odds of food insecurity compared with those living in wealthier zip codes (OR 1.79; 95% CI, 1.09 to 2.95), and those living in more segregated counties had a 70% increase in odds of food insecurity (OR 1.69; 95% CI, 1.03 to 2.78). These associations were slightly attenuated after controlling for age and sex.

In exploratory analyses, residential segregation moderated associations between sex and food insecurity (Supplemental Materials). Among participants living in more segregated counties, men had increased odds of food insecurity compared with women (OR 3.7; 95% CI, 1.61 to 8.53). However, men living in counties with less segregation did not have increased odds of food insecurity compared with women (OR 0.85; 95% CI, 0.45 to 1.6; residential segregation x sex interaction term P = 0.006). In addition, the association between younger age category (age <55) and food insecurity persisted in a subgroup of participants living in more segregated areas (OR 3.3; 95% CI, 1.49 to 7.32) but was not observed among participants living in less segregated areas (OR 1.42; 95% CI, 0.71 to 2.85; residential segregation x younger age category interaction term P = 0.12).

Table 3 displays food insecurity and housing instability by substance and level of substance use risk. Of the 296 participants who received a substance risk score, 92 (31%) reported substance use that presented a moderate or high risk to their health. Nine (3%) reported high-risk use of any substance (i.e., daily use, difficulty cutting back, strong urge to use). Participants most frequently reported moderate or high-risk use of tobacco (22.2%), alcohol (16.9%), and cannabis (11.6%). Nine (3%) reported intravenous drug use at any time in their lives. Younger age (age <55 years) was associated with moderate or high-risk cannabis use (P < 0.001), but not with tobacco, alcohol, or other drug use. Food insecurity was associated with moderate or high-risk tobacco use (P = 0.02). A higher proportion of participants with food insecurity reported moderate or high-risk use of cannabis, but associations did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.08). There were no statistically significant associations between housing instability and substance use.

Table 3.

Moderate or high-risk substance use by measures of food insecurity and housing instability

| Substance Use | Food Insecurity | Housing Instability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High No. (%) |

Margina, Low, or Very Low No. (%) |

Χ2 P Value | Negative Screen No. (%) |

Positive Screen No. (%) |

Χ2 P Value | |

| Tobacco use | 0.02b | 0.93 | ||||

| Low risk (n=210) | 139 (82) | 65 (70) | 174 (78) | 35 (78) | ||

| Moderate or high risk (n=60) | 30 (18) | 28 (30) | 48 (22) | 10 (22) | ||

| Alcohol | 0.71 | 0.21 | ||||

| Low risk (n=216) | 137 (84) | 74 (82) | 181 (85) | 33 (77) | ||

| Moderate or high risk (n=44) | 26 (16) | 16 (18) | 33 (15) | 10 (23) | ||

| Cannabis | 0.08 | 0.33 | ||||

| Low risk | 161 (91) | 83 (84) | 205 (89) | 43 (84) | ||

| Moderate or high risk | 16 (9) | 16 (16) | 25 (11) | 8 (16) | ||

| Other substancesa | 0.17 | 0.7 | ||||

| Low risk | 171 (93) | 86 (89) | 218 (92) | 45 (94) | ||

| Moderate or high risk | 12 (7) | 11 (11) | 19 (8) | 3 (6) | ||

| Any substance | 0.1 | 0.91 | ||||

| Low risk | 134 (72) | 65 (63) | 168 (69) | 35 (69) | ||

| Moderate or high risk | 51 (28) | 38 (37) | 74 (31) | 16 (31) | ||

Cocaine, amphetamines, inhalants, sedatives, hallucinogens, or opioids.

p< 0.05

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to report material need insecurities in a geographically diverse sample of adults on hemodialysis. Estimates of food insecurity were higher than the national average. Nationwide, 3.8% of households experienced very low food security in 2021.13 Nearly 10% of people in our sample reported very low food security during the same timeframe. Nearly 20% of people in our sample did not have a safe home of their own or were worried they may not have a safe place to live in the immediate future compared with 15% of respondents to the US Census Household Pulse Survey reporting it was very likely they would be evicted within the next 2 months in August of 2021.26 More than 15% of people in our sample reported moderate or high-risk use of tobacco, alcohol, and cannabis or other drugs. A large cohort study using administrative data estimated the nationwide prevalence of drug abuse in the hemodialysis population at 1.5%. However, other cross-sectional studies using valid screening tools in urban hemodialysis facilities have reported rates of current substance use disorder at 19%27 and alcohol use disorder at nearly 30%.28

We found that people on hemodialysis who were younger, with less educational attainment, with lower incomes, or experiencing financial strain were more likely to experience material need insecurities. Hispanic people on hemodialysis may be at increased risk for food insecurity, but we lacked sufficient power to detect associations between material need insecurities and ethnicity. In contrast with the general population, our study did not find an association between patient race and material need insecurities, although residential segregation moderated associations between age, sex, and food insecurity. Conceptual models of food insecurity resilience may explain the disproportionate burden of food insecurity among younger people and socially disadvantaged groups on hemodialysis. Food insecurity resilience models position food insecurity as a function of stressors at the micro-level (e.g., divorce) or the macro-level (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic or inflation) and individual and community-level resilience capacities.29 Hemodialysis initiation may restrict individual food insecurity resilience capacity through loss of income and strain on social support networks. The effect may be more pronounced for younger people who may not have accumulated wealth but have not aged into federal retirement programs and may not have adult children able to provide instrumental support. At the community level, disinvestment in residentially segregated areas may result in limited access to healthy foods.30

Hemodialysis initiation is a significant physiologic, social, and financial stressor31 that socially advantaged groups are better positioned to manage.32 For socially disadvantaged groups, the resulting financial strain and material need insecurities constrain options for self-managing kidney failure and accelerate cumulative disadvantage over the life course.10,33 Therefore, the disproportionate burden of material need insecurities among young adults, particularly in residentially segregated cities, may contribute to observed racial disparities in hospitalization and survival on dialysis.34,35 In a small cohort study of children with ESKD on hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis, children experiencing food insecurity had a higher rate of unplanned hospitalizations in the 12 months before screening.36 Future research should examine associations between material need insecurities and health disparities among adults on hemodialysis.

Given these health equity implications, policy and programmatic interventions to address material need insecurities are immediately warranted. Payers can incentivize person-centered, holistic care through alternative payment models that reward care coordination to address material need insecurities.37 At the facility level, interdisciplinary teams can implement more frequent, proactive screening. For people on hemodialysis with material need insecurities, a comprehensive harm reduction approach can include screening for substance use.38 Once identified, dialysis organizations could consider allocating additional social work staff to facilities with higher rates of material need insecurities and could partner with community-based organizations or professionals (e.g., community health workers) to connect people to community resources.39 The Centers for Medicare &Medicaid Services' recently proposed rule to reimburse community health workers and community health integration services for people with Medicare would support and sustain these models.

Our study had some limitations. We recruited participants directly from hemodialysis facilities and may not have enrolled people on hemodialysis with the highest burden of material need insecurities who may miss more dialysis treatments. Lack of variability limited statistical power to identify subgroup differences in material need insecurities. We measured participants' experiences of food security and housing instability via self-report, which may have been subject to respondent bias. Finally, we measured food insecurity and housing instability once, but material need insecurities often change over time. Future research should repeat analyses with larger subgroup sample sizes and repeated measures.

In this cross-sectional analysis of people on hemodialysis in the Baltimore and Washington, DC metropolitan areas, self-reported food insecurity, housing instability, and substance use were common, particularly among socially disadvantaged subgroups. Future research should examine whether material need insecurities perpetuate health disparities among people on hemodialysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the research participants and clinicians and staff from participating Fresenius Kidney Care facilities.

Disclosures

D.C. Crews reports the following: Consultancy: Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation (CORE); Research Funding: Baxter International; Somatus, Inc.; Honoraria: Maze Therapeutics; Advisory or Leadership Role: Editorial Board—Journal of Renal Nutrition, Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, Journal of the American Society of Nephrology; Associate Editor, Kidney360; Advisory Group, Health Equity Collaborative, Partner Research for Equitable System Transformation after COVID-19 (PRESTAC), Optum Labs; and Other Interests or Relationships: Board of Directors, National Kidney Foundation of Maryland/Delaware; Nephrology Board, American Board of Internal Medicine; Council of Subspecialist Societies, American College of Physicians; Executive Councilor, American Society of Nephrology. T. K. Novick reports the following: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney (NIDDK) from K23DK127153; Consultancy: Cricket Health. K.S. Taylor reports the following: Other Interests or Relationships: I was the Corporate Vice President of Quality for Fresenius Kidney Care (FKC) from September 2016 through December 2017. I am currently an Assistant Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing. I do not currently have any financial interests, relationship, or commitment with Fresenius Kidney Care. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work is supported by National Institute of Nursing Research from F31NR109461 (K.S. Taylor), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute from K24HL148181 (D.C. Crews).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Deidra C. Crews, Kathryn S. Taylor.

Data curation: Yuling Chen, Owen W. Smith, Sydney R. Santos, Kathryn S. Taylor.

Formal analysis: Nancy A. Perrin, Kathryn S. Taylor.

Funding acquisition: Kathryn S. Taylor.

Investigation: Kathryn S. Taylor.

Methodology: Deidra C. Crews, Nancy A. Perrin, Kathryn S. Taylor.

Project administration: Kathryn S. Taylor.

Supervision: Deidra C. Crews, Nancy A. Perrin.

Writing –original draft: Kathryn S. Taylor.

Writing – review & editing: Yuling Chen, Deidra C. Crews, Tessa K. Novick, Nancy A. Perrin, Sydney R. Santos, Owen W. Smith.

Data Sharing Statement

Partial restrictions to the data and/or materials apply. The authors can share a limited, de-identified data set through a data use agreement.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://links.lww.com/KN9/A402.

Supplemental Table 1. Unadjusted odds of food insecurity by demographic risk factors and residential segregation.

References

- 1.Kushel MB, Gupta R, Gee L, Haas JS. Housing instability and food insecurity as barriers to health care among low-income americans. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):71–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00278.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall YN, Choi AI, Himmelfarb J, Chertow GM, Bindman AB. Homelessness and CKD: a cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(7):1094–1102. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00060112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee T Crews DC Wesson DE, et al.. Food insecurity, CKD, and subsequent ESRD in US adults. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(1):38–47. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.10.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Core indicators of nutritional state for difficult-to-sample populations. J Nutr. 1990;120(suppl 11):1559–1600. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.suppl_11.1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novick TK, Kushel M, Crews D. Unstable housing and kidney disease: a primer. Kidney Med. 2022;4(4):100443. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2022.100443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrne T, Fargo JD, Montgomery AE, Roberts CB, Culhane DP, Kane V. Screening for homelessness in the Veterans health administration: monitoring housing stability through repeat screening. Public Health Rep. 2015;130(6):684–692. doi: 10.1177/003335491513000618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rose D. Economic determinants and dietary consequences of food insecurity in the United States. J Nutr. 1999;129(2S suppl):517S–520S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.2.517S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caspi C, Seligman H, Berge J, Ng SW, Krieger J. COVID-19 Pandemic-Era Nutrition Assistance: Impact and Sustainability. Health Affairs. 2022. https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hpb20220330.534478/ [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hallab A, Wish JB. Employment among patients on dialysis: an unfulfilled promise. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;13(2):203–204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.13491217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor KS, Umeukeje EM, Santos SR, McNabb KC, Crews DC, Hladek MD. Context matters: a qualitative synthesis of adherence literature for people on hemodialysis. Kidney360. 2023;4(1):41–53. doi: 10.34067/KID.0005582022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novick TK, Gadegbeku CA, Crews DC. Dialysis for patients with end-stage renal disease who are homeless. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(12):1581–1582. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.5470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Novick T, Osuna M, Crews D. Health-related social needs screening tool among patients receiving hemodialysis: evaluation of sensitivity and specificity. Kidney Med. 2023;5(9):100702. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2023.100702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Food Security in the U.S. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/frequency-of-food-insecurity/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monte L, Perez-Lopes D. COVID-19 Pandemic Hit Black Households Harder Than White Households, Even When Pre-Pandemic Socio-Economic Disparities Are Taken Into Account. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/07/how-pandemic-affected-black-and-white-households.html [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whittle HJ, Palar K, Hufstedler LL, Seligman HK, Frongillo EA, Weiser SD. Food insecurity, chronic illness, and gentrification in the San Francisco bay area: an example of structural violence in United States public policy. Soc Sci Med. 2015;143:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shieh JA Leddy AM Whittle HJ, et al.. Perceived neighborhood-level drivers of food insecurity among aging women in the United States: a qualitative study. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;121(5):844–853. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2020.12.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whittle HJ Sheira LA Frongillo EA, et al.. Longitudinal associations between food insecurity and substance use in a cohort of women with or at risk for HIV in the United States. Addiction. 2019;114(1):127–136. doi: 10.1111/add.14418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raja A, Heeren TC, Walley AY, Winter MR, Mesic A, Saitz R. Food insecurity and substance use in people with HIV infection and substance use disorder. Subst Abus. 2022;43(1):104–112. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2020.1748164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rose-Jacobs R, Trevino-Talbot M, Vibbert M, Lloyd-Travaglini C, Cabral HJ. Pregnant women in treatment for opioid use disorder: material hardships and psychosocial factors. Addict Behav. 2019;98:106030. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2019.106030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunne EM, Burrell LE, Diggins AD, Whitehead NE, Latimer WW. Increased risk for substance use and health-related problems among homeless veterans. Am J Addict. 2015;24(7):676–680. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pellowski JA, Huedo-Medina TB, Kalichman SC. Food insecurity, substance use, and sexual transmission risk behavior among people living with HIV: a daily level analysis. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(7):1899–1907. doi: 10.1007/s10508-017-0942-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grubbs V, Vittighoff E, Grimes B, Johansen KL. Mortality and illicit drug dependence among hemodialysis patients in the United States: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2016;17(1):56–61. doi: 10.1186/s12882-016-0271-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Radimer KL, Radimer KL. Measurement of household food security in the USA and other industrialised countries. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(6A):859–864. doi: 10.1079/PHN2002385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montgomery AE, Fargo JD, Kane V, Culhane DP. Development and validation of an instrument to assess imminent risk of homelessness among veterans. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(5):428–436. doi: 10.1177/003335491412900506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO ASSIST Working Group. The alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97(9):1183–1194. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00185.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.United States Census Bureau. Week 48 Househole Pulse Survey, Housing Table 3a. Accessed October 16, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2022/demo/hhp/hhp48.html [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cukor D Coplan J Brown C, et al.. Depression and anxiety in urban hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(3):484–490. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00040107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hegde A, Veis JH, Seidman A, Khan S, Moore J. High prevalence of alcoholism in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35(6):1039–1043. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70037-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bene C. Resilience of local food systems and links to food security—a review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Security. 2020;12(4):805–822. doi: 10.1007/s12571-020-01076-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bower KM, Thorpe RJ, Rohde C, Gaskin DJ. The intersection of neighborhood racial segregation, poverty, and urbanicity and its impact on food store availability in the United States. Prev Med. 2014;58:33–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hladek MD Zhu J Crews DC, et al.. Physical resilience phenotype trajectories in incident hemodialysis: characterization and mortality risk assessment. Kidney Int Rep. 2022;7(9):2006–2015. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2022.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferraro KF, Kemp BR, Williams MM. Diverse aging and health inequality by race and ethnicity. Innov Aging. 2017;1(1):igx002. doi: 10.1093/geroni/igx002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Rand AM. The precious and the precocious: understanding cumulative disadvantage and cumulative advantage over the life course. Gerontologist. 1996;36(2):230–238. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.2.230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan G Norris KC Greene T, et al.. Race/ethnicity, age, and risk of hospital admission and length of stay during the first year of maintenance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(8):1402–1409. doi: 10.2215/CJN.12621213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johns TS Estrella MM Crews DC, et al.. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, race, and mortality in young adult dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(11):2649–2657. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013111207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Starr MC, Wightman A, Munshi R, Li A, Hingorani S. Association of food insecurity and acute health care utilization in children with end-stage kidney disease. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(11):1097–1099. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.3086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tummalapalli SL, Mohan S. Value-based kidney care: a recipe for success. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;16(10):1467–1469. doi: 10.2215/CJN.11250821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boucher LM Shoemaker ES Liddy CE, et al.. “The drug use unfortunately isn't all bad”: chronic disease self-management complexity and strategy among marginalized people who use drugs. Qual Health Res. 2022;32(6):871–886. doi: 10.1177/10497323221083353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cervantes L, Robinson BM, Steiner JF, Myaskovsky L. Culturally concordant community-health workers: building sustainable community-based interventions that eliminate kidney health disparities. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;33(7):1252–1254. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2022030319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Partial restrictions to the data and/or materials apply. The authors can share a limited, de-identified data set through a data use agreement.