Abstract

Chemical investigation of the endophyte Pseudofusicoccum stromaticum CMRP4328 isolated from the medicinal plant Stryphnodendron adstringens yielded ten compounds, including two new dihydrochromones, paecilins Q (1) and R (2). The antifungal activity of the isolated metabolites was assessed against an important citrus pathogen, Phyllosticta citricarpa. Cytochalasin H (6) (78.3%), phomoxanthone A (3) (70.2%), phomoxanthone B (4) (63.1%), and paecilin Q (1) (50.5%) decreased in vitro the number of pycnidia produced by P. citricarpa, which are responsible for the disease dissemination in orchards. In addition, compounds 3 and 6 inhibited the development of citrus black spot symptoms in citrus fruits. Cytochalasin H (6) and one of the new compounds, paecilin Q (1), appear particularly promising, as they showed strong activity against this citrus pathogen, and low or no cytotoxic activity. The strain CMRP4328 of P. stromaticum and its metabolites deserve further investigation for the control of citrus black spot disease.

Keywords: Pseudofusicoccum stromaticum, Phyllosticta citricarpa, Stryphnodendron adstringens, fungal metabolites, dihydro-chromones, phytopathogenic fungi

Introduction

Endophytic fungi establish remarkable associations with their hosts [1]. They have attracted considerable attention, especially those associated with medicinal plants, due to their ecological and biotechnological potential [2–4]. Recent research has shown that endophytic fungi produce a wide diversity of metabolites with various biological activities that could find a use as pharmaceuticals or agrochemicals [2,4, 5].

Endophytes isolated from harsh environments have been described as of great interest for bioprospecting studies, since stress factors can induce biosynthetic pathways to produce secondary metabolites [4–6]. The endophytes of plants found in the Cerrado, the Brazilian savanna, endure unique conditions, including dry and wet seasons, combined with the occurrence of natural fire [7]. Widely distributed in this biome, Stryphnodendron adstringens (Mart) Coville (Fabaceae) (commonly known as “barbatimão”) is a native Brazilian savanna tree that has been long used in folk medicine as anti-inflammatory, antifungal, antioxidant, and anticancer agents [8,9].

As part of our screening for natural products with antifungal potential, Pseudofusicoccum stromaticum strain CMRP4328, isolated from the medicinal plant S. adstringens, caught our attention, as its extract showed considerable antifungal activity against citrus pathogens in a preliminary assay [5]. Studies on the chemical characterization and biological activities of strains of P. stromaticum were recently reported. New coumarins showing antifungal and anti-cholinesterase activity were isolated [10]. In another study, 11 compounds were identified and 1 compound, tephrosin, showed activity against a colorectal cancer cell line (HCT-116) [11]. However, the potential of the metabolites of P. stromaticum against citrus pathogens remained unexplored.

Citrus black spot (CBS) is an important citrus disease caused by Phyllosticta citricarpa, which leads to economic losses in citrus-producing regions worldwide [12]. Widely distributed in warm summer rainfall areas, CBS disease causes a considerable economic impact on citrus production by depreciating the commercial value of the fruit, reducing crop productivity, increasing production costs, and making the export of citrus unfeasible [12,13]. In addition, concerns were raised about health and environmental issues as well as antifungal resistance associated with the broad use of synthetic fungicides to control P. citricarpa [13, 14]. Therefore, the search for new eco-friendlier alternatives to control CBS disease is needed.

In this context, we explored the secondary metabolites produced by P. stromaticum (CMRP4328) after large-scale fermentation and evaluated their antifungal activities against P. citricarpa.

Results

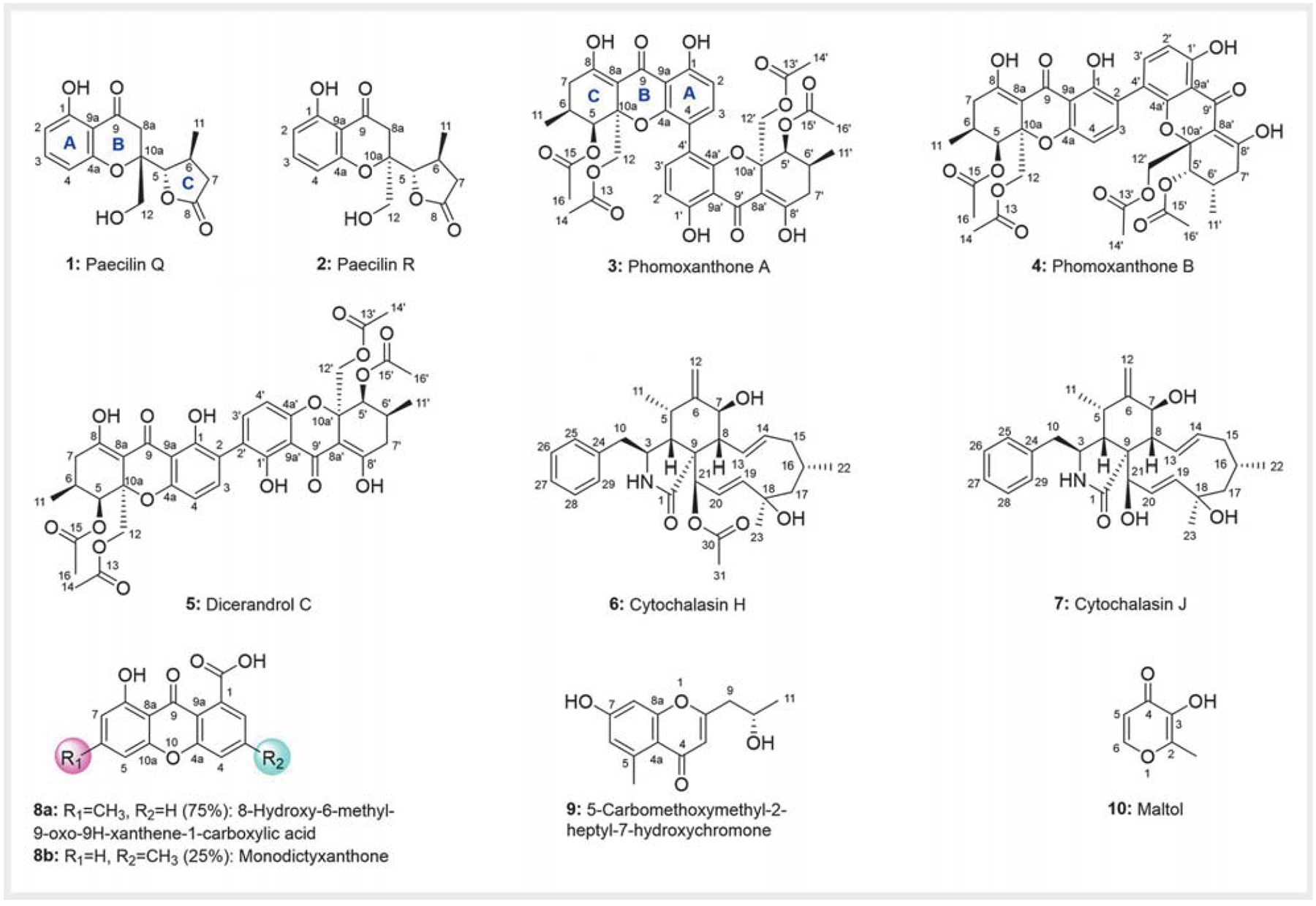

Scale-up fermentation of P. stromaticum CMRP4328 (10 L) using malt extract medium, followed by extraction with MeOH, afforded 1.02 g of brown oily crude extract. The crude extract was subjected to reverse-phase C18 column chromatography, followed by Sephadex LH-20 and HPLC purification to provide compounds 1–10 (Fig. 1 and Fig. 1S, Supporting Information).

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of compounds 1–10 produced by Pseudofusicoccum stromaticum CMRP4328.

The chemical structures of the known compounds 3–10 (Fig. 1) were determined by 1D and 2D NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry (MS) (Figs. 1 and 2, Tables 1 and 2, and Fig. 2S and Table 1S, Supporting Information), and by comparison with literature data. They were identified as phomoxanthone A (3) [6, 15, 16], phomoxanthone B (4) [6, 15, 16], dicerandrol C (5) [6, 17–23], cytochalasin H (6) [24–26], cytochalasin J (7) [24–26], 8-hydroxy-6-methyl-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-1-carboxylic acid (8a) [27], monodictyxanthone (8b) [28], 5-carbomethoxymethyl-2-heptyl-7-hydroxychromone (9) [29], and maltol (10).

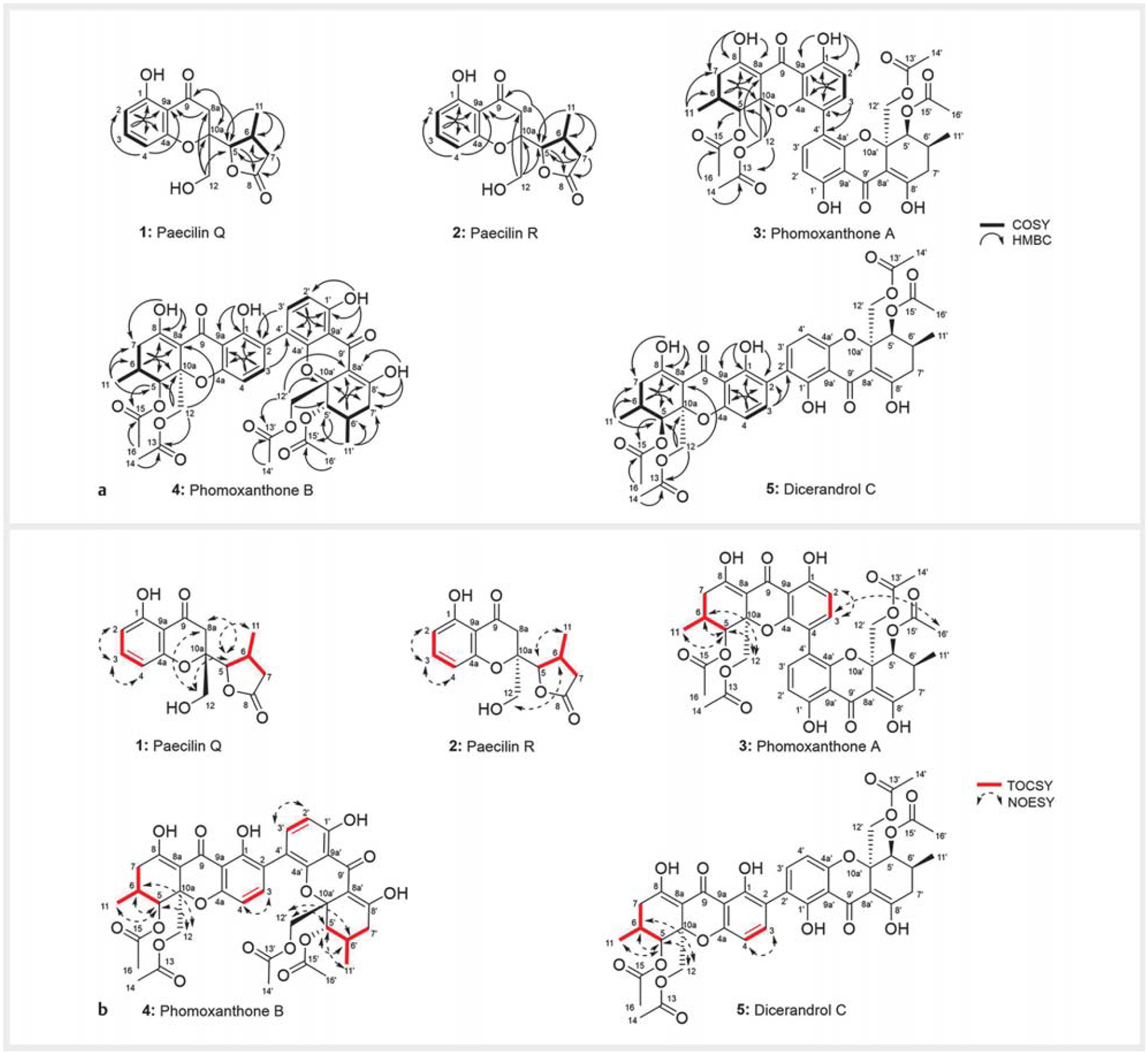

Fig. 2.

a 1H,1H-COSY (−) and selected HMBC (→) correlations of compounds 1–5. b TOCSY (→) and selected NOESY correlations of compounds 1–5.

Table 1.

13C NMR spectroscopic data (100MHz) for compounds 1–5 compared with the literature data of 3 (δ in ppm).

| Position | 1* | 2* | 3 (Lit.)17 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC, type(a) | δC, type(a) | δC, type(b) | δC, type(b) | δC, type(b) | δC, type(b) | |

| 1 | 162.9, C | 162.8, C | 161.6, C | 161.7, C | 160.0, C | 159.5, C |

| 2 | 110.2, CH | 110.3, CH | 109.5, CH | 109.7, CH | 118.6, C | 118.0, C |

| 3 | 139.7, CH | 139.5, CH | 141.1, CH | 141.4, CH | 139.5, CH | 140.4, CH |

| 4 | 108.5, CH | 108.4, CH | 115.3, C | 115.6, C | 107.9, C | 108.4, CH |

| 4a | 161.0, C | 161.0, C | 153.8, C | 154.0, C | 157.3, C | 157.6, C |

| 5 | 84.8, CH | 89.8, CH | 70.3, CH | 70.6, CH | 70.5, CH | 70.6, CH |

| 6 | 31.2, CH | 30.6, CH | 27.5, CH | 27.8, CH | 27.9, CH | 27.9, CH |

| 7 | 37.4, CH2 | 37.4, CH2 | 33.2, CH2 | 33.5, CH2 | 33.5, CH2 | 33.6, CH2 |

| 8 | 178.8, C | 178.5, C | 177.6, C | 177.9, C | 178.0, C | 178.0, C |

| 8a | 38.7, CH2 | 40.0, CH2 | 100.1, C | 100.3, C | 101.0, C | 100.6, C |

| 9 | 198.3, C | 198.8, C | 187.7, C | 187.9, C | 188.3, C | 188.0, C |

| 9a | 108.5, C | 108.6, C | 106.2, C | 106.5, C | 106.4, C | 106.6, C |

| 10a | 84.8, C | 84.8, C | 80.3, C | 80.6, C | 80.8, C | 80.7, C |

| 11 | 21.0, CH3 | 20.9, CH3 | 17.5, CH3 | 17.7, CH3 | 17.8, CH3 | 17.8, CH3 |

| 12 | 63.2, CH2 | 63.9, CH2 | 64.5, CH2 | 64.8, CH2 | 64.7, CH2 | 65.5, CH2 |

| 13 | 170.0, C | 170.3, C | 170.6, C | 170.6, C | ||

| 14 | 20.4, CH3 | 20.6, CH3 | 21.0, CH3 | 20.9, CH3 | ||

| 15 | 169.6, C | 169.8, C | 170.7, C | 170.7, C | ||

| 16 | 20.6, CH3 | 20.9, CH3 | 21.1, CH3 | 21.1, CH3 | ||

| 1′ | 161.6, C | 161.7, C | 161.8, C | 159.5, C | ||

| 2′ | 109.5, CH | 109.7, CH | 110.1, CH | 118.0, C | ||

| 3′ | 141.1, CH | 141.4, CH | 139.6, CH | 140.4, CH | ||

| 4′ | 115.3, C | 115.6, C | 117.3,C | 108.4, CH | ||

| 4a′ | 153.8, C | 154.0, C | 154.9, C | 157.6, C | ||

| 5′ | 70.3, CH | 70.6, CH | 69.6, CH | 70.6, CH | ||

| 6′ | 27.5, CH | 27.8, CH | 27.8, CH | 27.9, CH | ||

| 7′ | 33.2, CH2 | 33.5, CH2 | 33.4, CH2 | 33.6, CH2 | ||

| 8′ | 177.6, C | 177.9, C | 177.9, C | 178.0, C | ||

| 8a′ | 100.1, C | 100.3, C | 100.7, C | 100.6, C | ||

| 9′ | 187.7, C | 187.9, C | 188.3, C | 188.0, C | ||

| 9a′ | 106.2, C | 106.5, C | 106.6, C | 106.6, C | ||

| 10a′ | 80.3, C | 80.6, C | 80.5, C | 80.7, C | ||

| 11′ | 17.5, CH3 | 17.7, CH3 | 17.6, CH3 | 17.8, CH3 | ||

| 12′ | 64.5, CH2 | 64.8, CH2 | 64.3, CH2 | 65.5, CH2 | ||

| 13′ | 170.0, C | 170.3, C | 170.1, C | 170.6, C | ||

| 14′ | 20.4, CH3 | 20.6, CH3 | 20.5, CH3 | 20.9, CH3 | ||

| 15′ | 169.6, C | 169.8, C | 169.9, C | 170.7, C | ||

| 16′ | 20.6, CH3 | 20.9, CH3 | 21.1, CH3 | 21.1, CH3 |

Atom numbering according to compounds 3–5 for better comparison;

CD3OD,

CDCl3;

see Supporting Information for NMR spectra; Assignments were supported by 2D HSQC and HMBC experiments

Table 2.

1H NMR spectroscopic data (500MHz) for compounds 1–5, (δ in ppm).

| Position | 1* | 2* | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH (mult, J in [Hz])(a) | δH (mult, J in [Hz])(a) | δH (mult, J in [Hz])(b) | δH (mult, J in [Hz])(b) | δH (mult, J in [Hz])(b) | |

| 1-OH | 11.52 (s) | 11.59 (s) | 11.79 (s) | ||

| 2 | 6.45 (dd, 8.4, 0.9) | 6.43 (dd, 8.5, 1.0) | 6.54 (d, 8.7) | ||

| 3 | 7.38 (t, 8.3) | 7.36 (t, 8.3) | 7.36 (d, 8.8) | 7.16 (d, 8.4) | 7.38 (d, 8.5) |

| 4 | 6.42 (dd, 8.3, 0.9) | 6.43 (dd, 8.0, 1.0) | 6.41 (d, 8.4) | 6.44 (d, 8.5) | |

| 5 | 4.41 (d, 4.3) | 4.41 (d, 4.3) | 5.39 (brd, 1.3) | 5.51 (d, 1.2) | 5.54 (d, 1.5) |

| 6 | 2.86 (m) | 2.95 (m) | 2.33 (m) | 2.40 (m) | 2.38 (m) |

| 7 | 2.86 (brm) 2.24 (brm) | 2.82 (dd, 18.0, 9.4) 2.21 (dd, 18.0, 5.1) | 2.43 (m) 2.32 (m) | 2.50–2.30 (m) | 2.50–2.31 (m) |

| 8-OH | 14.08 (s) | 14.06 (s) | 14.03 (s) | ||

| 8a | 3.02 (d, 18.0) 2.98 (d, 17.5) | 3.14 (d, 17.5) 3.03 (d, 17.5) | |||

| 11 | 1.22 (d, 6.6) | 1.24 (d, 7.0) | 0.98 (d, 6.3) | 1.04 (brd, 5.8) | 1.04 (d, 5.9) |

| 12 | 3.78 (s) | 2.72 (d, 11.8) 3.18 (d, 11.8) | 4.26 (d, 12.7) 4.14 (d, 12.7) | 4.53 (d, 13.0) 4.28 (d, 13.1) | 4.47 (d, 12.8) 4.16 (d, 12.8) |

| 14 | 1.86 (s) | 2.09 (s) | 2.08 (s) | ||

| 16 | 2.04 (s) | 2.08 (s) | 2.08 (s) | ||

| 1′ | 11.52 (s) | 11.36 (s) | 11.79 (s) | ||

| 2′ | 6.54 (d, 8.7) | 6.55 (d, 8.6) | |||

| 3′ | 7.36 (d, 8.8) | 7.30 (d, 8.5) | 7.38 (d, 8.5) | ||

| 4′ | 6.44 (d, 8.5) | ||||

| 5′ | 5.39 (brd, 1.3) | 5.33 (d, 1.9) | 5.54 (d, 1.5) | ||

| 6′ | 2.33 (m) | 2.27 (m) | 2.38 (m) | ||

| 7′ | 2.43 (m) 2.32 (m) | 2.50–2.30 (m) | 2.50–2.31 (m) | ||

| 8′-OH | 14.08 (s) | 14.01 (s) | 14.03 (s) | ||

| 11′ | 0.98 (d, 6.3) | 0.97 (d, 6.5) | 1.04 (d, 5.9) | ||

| 12′ | 4.26 (d, 12.7) 4.14 (d, 12.7) | 4.52 (d, 12.5) 3.84 (d, 12.8) | 4.47 (d, 12.8) 4.16 (d, 12.8) | ||

| 14′ | 1.86 (s) | 1.77 (s) | 2.08 (s) | ||

| 16′ | 2.04 (s) | 2.05 (s) | 2.08 (s) |

Atom numbering according to compounds 3–5 for better comparison;

CD3OD,

CDCl3;

see Supporting Information for NMR spectra. Assignments were supported by 2D HSQC and HMBC experiments

Compound 1 was obtained as an optically active pale yellow solid. The UV spectrum (λmax 207, 275, 350 nm) displayed UV-vis characteristics similar to the isolated metabolites 3–5 and to those reported for phomoxanthone/dicerandrol-rearranged analogues including paecilins [30–32], ascherxanthones [33], xylaromanones [34], blennolides [30, 35] pseudopalawanone [32], penexanthones [23], and versixanthones [36], thereby suggesting the presence of a similar chromanone chromophore in 1 (Fig. 3S, Supporting Information). The molecular formula of 1 was deduced as C15H16O6 on the basis of (−)-HRESI-MS [m/z 291.0866 [M – H]− (calcd. for C15H15O6, 291.0874)], (+)-HRESI-MS [m/z 293.1020 [M + H]+ (calcd. for C15H17O6, 293.1020)], and NMR data. The molecular weight and molecular formula differences between 1 and 3–5, indicated that compound 1 was a monomer instead of a dimer as, e.g., compounds 3–5. The 13C NMR and HSQC spectra of 1 (Table 1) revealed 15 carbon resonances, including two carbonyl, six sp2, one quaternary (δC 84.8), two methine, one methyl, three methylene carbons. Among these, the signal for one carbonyl resonance (δC 198.3) and 6 aromatic carbons (ring A) were consistent with a chromanone-chromophore core. The proton NMR data of 1 in CD3OD (Table 2) displayed signals for three aromatic methine protons, two aliphatic methine protons (δH 4.41, d, J = 4.3 Hz, H-5; δH 2.86, m, H-6), three methylenes, and one methyl group (δH 1.22, CH3-11) (Table 2). Among these, the presence of three ortho-coupled aromatic protons at δH 7.38 (t, J = 8.3 Hz), 6.45 (dd, J = 8.4, 0.9 Hz), and 6.42 (dd, J = 8.3, 0.9 Hz) was consistent with a trisubstituted benzene, which was further supported by the observation of 1H,1H-COSY and NOESY cross-peaks for H-2/H-3 and H-3/H-4, and HMBC correlations (H-2 to C-9a, C-4; H-3 to C-1, C-4a; H-4 to C-2, C-9a) (Fig. 2). The 1H and 13C NMR data of compound 1 suggested that ring C of compounds 3–5 was replaced by a 5-membered lactone (ring C) similar to the one found in paecilins [30, 31], versixanthones [36], blennolides [35], and xylaromanones [34]. The lactone ring substructure of 1 was deduced from the existence of two methine protons (δH 4.41, H-5; δH 2.86, H-6), one methylene (δH 2.86, 2.24, CH2-7), and one methyl (δH 1.22, CH3-11), in conjunction with 1H,1H-COSY (CH2-7/H-6; H-6/H-5 and H-6/CH3-11), HSQC, and HMBC correlations [CH3-11 with C-6, C-7, C-5; CH-5 with C-8; CH2-7 with C-8, C-6, C-5]. The HMBC correlations of the singlet CH2-12 to C-10a, C-5 and C-8a revealed the C-5/C10a connection of rings C/B. The assignment of the remaining methylene (δH 3.02, 2.98, CH2-8a) at the 8a position was supported by the HMBC correlations from CH2-8a to C-9, C-9a, C-5, and C-10a. The configuration at C-6, C-5, and C-10a was established based on NOESY correlations and optical rotation data. The observed NOE cross-peaks between H-5/CH3-11 and H-5/CH2-12 indicated that H-5, CH2-12, and CH3-11 shared the same facial orientation (Fig. 2). The optical rotation of compound 1 was very similar to that of reported paecilin B (11) (Fig. 4S, Supporting Information) [30]. In addition, a synthetic isomer [13, (R)-5-hydroxy-2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-([2R,3R]-3-methyl-5-oxotetrahydrofuran-2-yl) chroman-4-one)] [37] of compound 1 has been reported, with an opposite sign of optical rotation (Fig. 4S, Supporting Information). Therefore, the absolute configuration of 1 was established as depicted in Fig. 1, with all stereo-centers in the S-configuration. Detailed analyses of 1D (1H, 13C) and 2D (HSQC, 1H,1H-COSY, HMBC, and NOESY) NMR data (Fig. 2 and Tables 1 and 2) fully support the structure of 1 as depicted in Fig. 1. Compound 1 is as new natural product, closely related to paecilin B, and was named paecilin Q.

Compound 2 was obtained as a yellow solid and displayed UV-vis characteristics similar to 1. Compounds 1 and 2 shared identical molecular formulas of C15H16O6 based on (+)-HRESIMS. Comprehensive analyses of 1D (1H, 13C) and 2D (HSQC, 1H,1H-COSY, HMBC, and NOESY) NMR data of 2 (Fig. 1 and Tables 1 and 2) revealed that compounds 1 and 2 had the same planar structure. The 13C NMR and 1H NMR data of 2 (Tables 1 and 2) were similar to those of 1, except for slight 1H and 13C NMR shifts at the CH-5, CH2-8a, and CH2-12 positions. In addition, CH2-12, which was detected in compound 1 as a singlet, was observed in compound 2 as two doublets at 3.18 (J = 11.8 Hz)/2.72 (J = 11.8 Hz). The observed NOE cross-peaks between H-5/CH3-11 and H-6/CH2-12 indicated that H-5 and CH3-11 shared the same facial orientation, while CH2-12 and H-6 were on the other face (Fig. 2). All 2D-NMR (1H,1H-COSY, HMBC, and NOESY) correlations were in full agreement with structure 2 (Fig. 1). Based on the cumulative spectroscopic data, 1 and 2 differed only at the C-10a stereocenter, and thus compound 2 is an 10a-epi form of 1. Compound 2 is a new epimeric analogue of paecilin Q (1) and was named paecilin R (Fig. 1).

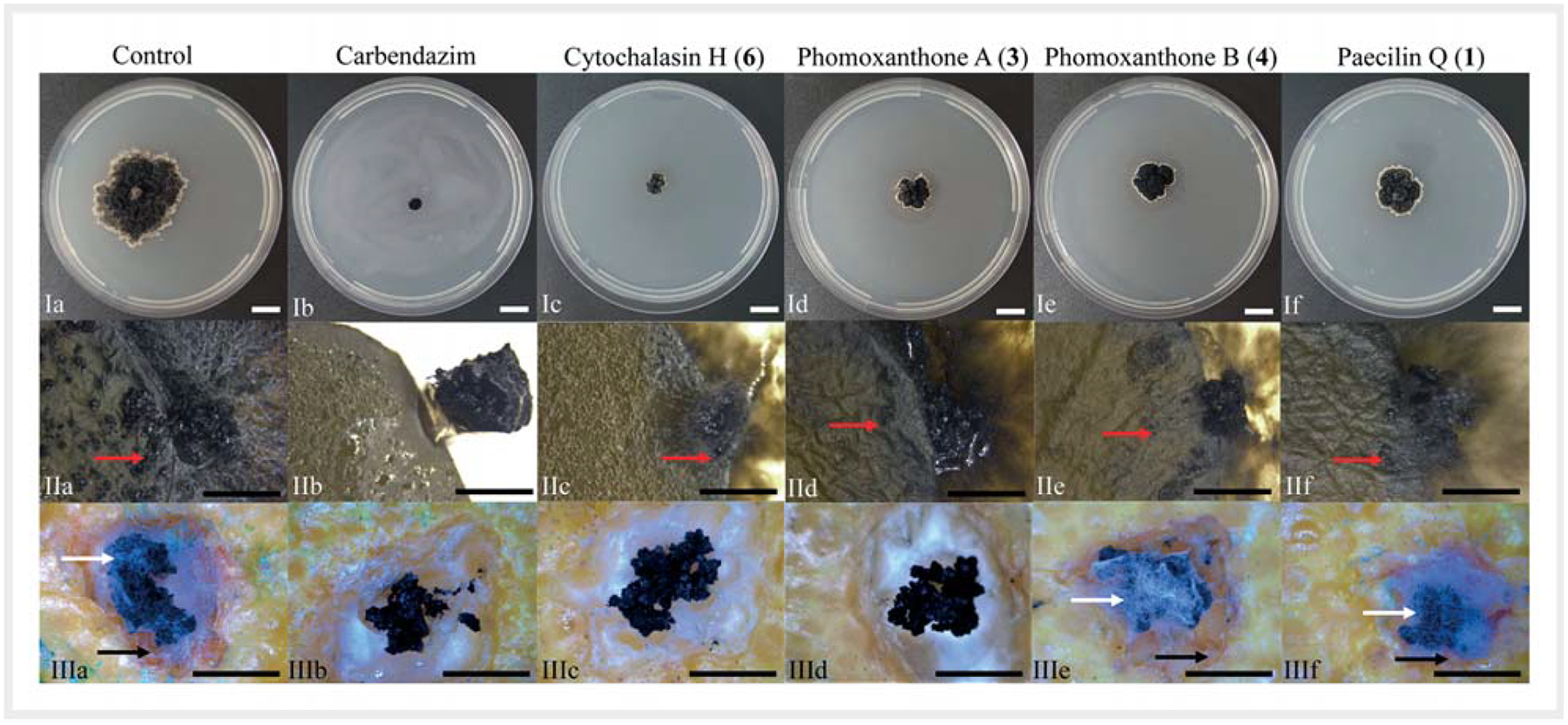

The antifungal activity of compounds 1–10 was evaluated against P. citricarpa. In petri dishes, cytochalasin H (6) and phomoxanthone A (3) at a concentration of 10 mg/mL inhibited the mycelial growth of P. citricarpa by 80 and 65.7%, respectively. Phomoxanthone B (4) (51.4% inhibition) and paecilin Q (1) (48.6% inhibition) had moderate antifungal activity. The other compounds showed lower inhibition, ranging from 2.8 to 16.2% (Fig. 3 and Table 3).

Fig. 3.

Antifungal activity of cytochalasin H (6), phomoxantone A (3), phomoxantone B (4), and paecilin Q (1) (10 mg/mL) against the phyto-pathogen Phyllosticta citricarpa. I a–f Evaluation of mycelial growth, II a–f development of pycnidia in citrus leaves, III a–f citrus black spot (CBS) lesions in detached fruits. a Control with methanol, b treatment with carbendazim. Treatment with compounds: c cytochalasin H (6), d phomoxantone A (3), e phomoxantone B (4), and f paecilin Q (1). Red arrow (II): pycnidia of P. citricarpa, black arrow (III): necrotic zone, white arrow (III): fungal growth. – Scale bars: I = 10 mm, II = 3 mm, III = 5 mm. For antifungal activities of the remaining compounds (2, 5, 7–10), see Fig. 4S, Supporting Information)

Table 3.

Growth [in cm mean (± SD)] of the citrus pathogen Phyllosticta citricarpa in petri dishes, number of pycnidia produced in leaves by P. citricarpa, development of citrus black spot (CBS) symptoms, and cytotoxicity IC50 values obtained after 72 h incubation of A549 (non-small cell lung cancer) and PC3 (prostate cancer) human cell lines in the presence of 100 uL of compounds 1–10 produced by Pseudofusicoccum stromaticum CMRP4328.

| Compounds | Petri dishes | Pycnidia | CBS symptoms | IC50 μM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | PC3 | ||||

| Paecilin Q (1) | 1.8 ± 0.2*b | 98 ± 11*c | + | >80 | >80 |

| Paecilin R (2) | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 128 ± 4*c | + | >80 | >80 |

| Phomoxanthone A (3) | 1.2 ± 0.1*b | 59 ± 6*b | − | 4.95 ± 0.53 | 3.18 ± 0.02 |

| Phomoxanthone B (4) | 1.7 ± 0.3*b | 73 ± 6*b | + | 10.39 ± 0.59 | 7.39 ± 0.62 |

| Dicerandrol C (5) | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 187 ± 9 | + | 2.92 ± 0.24 | 2.23 ± 0.13 |

| Cytochalasin H (6) | 0.7 ± 0.2*a | 43 ± 7*a | − | >50 | >50 |

| Cytochalasin J (7) | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 172 ± 8 | + | >80 | >80 |

| 8-Hydroxy-6-methyl-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-1-carboxylic acid (8a) Monodictyxanthone (8b) | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 191 ± 7 | + | >80 | >80 |

| 5-Carbomethoxymethyl-2-heptyl-7-hydroxychromone (9) | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 200 ± 6 | + | >80 | >80 |

| Maltol (10) | 2.9 ± 0.3*c | 176 ± 9 | + | >80 | >80 |

| Carbendazim | 0* | 0 | − | NE | NE |

| Control with methanol | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 198 ± 8 | + | NE | NE |

− Absence of symptoms; + presence of symptoms;

Samples that were significant in the reduction of growth compared to the control in ANOVA, p < 0.001; The same subscript letter in the same column means the values are not different. NE: not evaluated. Compound concentration in the applied solution was 10 mg/mL. Actinomycin D and H2O2 [A549 (non-small cell lung), PC3 (prostate) human cancer cell lines] were used as positive controls at 20 μM and 2 mM concentrations, respectively (0% viable cells).

Four compounds decreased more than 50% of the pycnidia produced by P. citricarpa citrus in leaves. The highest inhibition was obtained with cytochalasin H (6) (78.3%), followed by phomoxanthone A (3) (70.2%), phomoxanthone B (4) (63.1%), and paecilin Q (1) (50.5%) (Fig. 3 and Table 3). Paecilin R (2) reduced the pycnidia formation by 35.5% and the other compounds showed less than 14% inhibition [cytochalasin J (7), maltol (10), dicerandrol C (5), 8-hydroxy-6-methyl-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-1-carboxylic acid (8a), and monodictyxanthone (8b)] or no activity [carbomethoxymethyl-2-heptyl-7-hydroxychromone (9)] (Table 3 and Fig. 5S, Supporting Information).

In a further assay, cytochalasin H (6) and phomoxanthone A (3) completely inhibited CBS symptoms in citrus fruits, comparably to the fungicide carbendazim, where only the residual mycelium used for the fungal inoculation was observed (Fig. 3). The other compounds were not able to control the development of CBS lesions, with results similar to the negative control, where fungal growth and the necrotic zone around the lesion were observed (Fig. 3, Table 3, and Fig. 5S, Supporting Information).

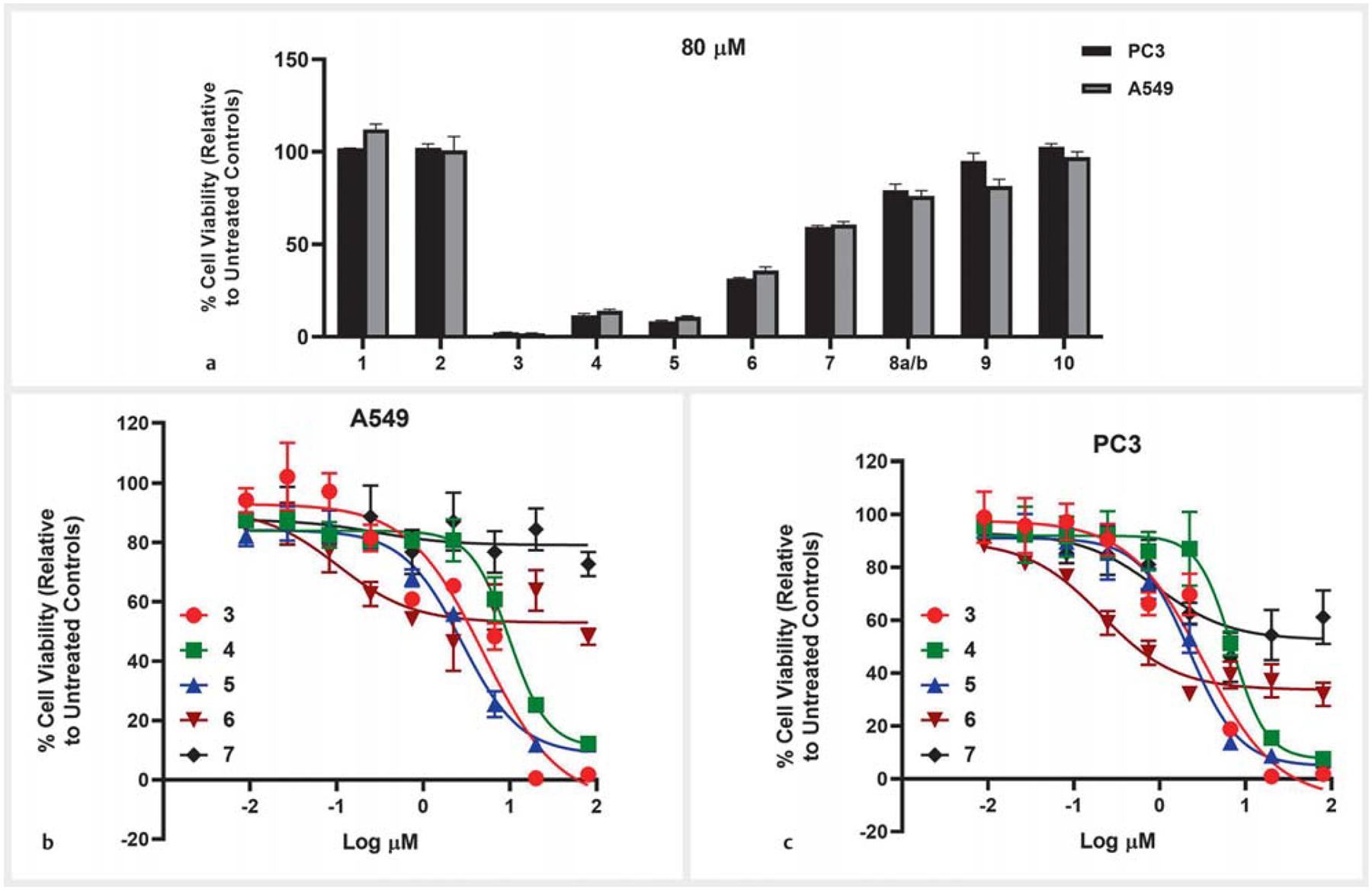

The cytotoxic activities of compounds 1–10 were evaluated using A549 (non-small cell lung) and PC3 (prostate) human cancer cell lines (Table 3). Phomoxanthone A (3) [IC50 = 4.95 μM (A549); 3.18 μM (PC3)], phomoxanthone B (4) [(IC50 = 10.39 μM (A549); 7.39 μM (PC3)], and dicerandrol C (5) [(IC50 = 2.92 μM (A549); 2.23 μM (PC3)] were highly cytotoxic. Cytochalasin H (6) showed IC50>50 μM against both A549 and PC3. Other compounds including the new derivatives paecilins Q (1) and R (2) showed no cytotoxicity at up to an 80 μM concentration against these cell lines (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

a % Viability of A549 (non-small lung) and PC3 (prostate) human cancer cell lines after 72 h of treatment at the 80 μM concentration of compounds 1–10. b Concentration-response of compounds 3–7 against the A549 (non-small cell lung) human cancer cell line (72 h). c Concentration-response of compounds 3–7 against the PC3 (prostate) human cancer cell line (72 h). A549: IC50 for compounds 1–2 (> 80 μM), 3 (4.95 ±0.53 μM), 4 (10.39 ± 0.59 μM), 5 (2.92 ± 0.24 μM), 6 (> 50 μM), and 7–10 (> 80 μM). PC3: IC50 for compounds 1–2 (> 80 μM), 3 (3.18 ± 0.02 μM), 4 (7.39 ± 0.62 μM), 5 (2.23 ± 0.13 μM), 6 (> 50 μM), and 7–10 (> 80 μM); see Table 3. Actinomycin D and H2O2 [A549 (non-small cell lung), PC3 (prostate) human cancer cell lines] were used as positive controls at 20 μM and 2 mM concentrations, respectively (0% viable cells).

Discussion

P. stromaticum CMRP4328 was isolated from S. adstringens, commonly found in the Cerrado, and used as a medicinal plant in Brazil [5]. The species P. stromaticum was already isolated as an endophytic fungus from S. adstringens in the Brazilian Cerrado [2, 5] and has also been reported as an endophyte from other plants in Brazil [2,5, 11].

In a previous study [5], we observed that an extract of P. stromaticum CMRP4328 exhibited high activity against citrus plant pathogens. In this study, we identified the compounds produced by this strain and evaluated their cytotoxicity and ability to control the citrus phytopathogen P. citricarpa. Ten compounds were isolated and identified (Fig. 1), including two new chromanone derivatives, paecilin Q (1) and R (2), four xanthenes (3–5 and 8a/8b), two cytochalasins (6–7), one chromone (9), and one pyranone (10).

Paecilins were previously isolated and reported from fungi belonging to different genera and ecological habitats, but not from Pseudofusicoccum species. Paecilins A and B were produced by the mangrove endophytic fungus Paecilomyces sp. [38, 39]. In addition, paecilin B was also isolated from other fungi, such as Setophoma terrestris (soil), Talaromyces sp. (endophytic of Duguetia stelechantha), and Pseudopalawania siamensis (saprophytic of Caryota sp.) [30, 32, 39, 40]. Paecilin C was obtained from the marine fungus Penicillium sp. [41]. Paecilin D was reported from Talaro-myces sp., an endophyte of D. stelechantha [40], and paecilin E was produced by the marine fungus Neosartorya fennelliae [31]. More recently, 14 additional paecilins have been reported from the endophytic fungus Xylaria curta E10 [42] and a mutant strain of Penicillium oxalicum 114–2 [43]. It is very important to note that the chemical structures of paecilins F–H reported from the endophytic fungus X. curta E10 [42] are different from those of paecilins F–H reported from the mutant strain of P. oxalicum 114–2 [43]. Two papers [42, 43] were published in the same time frame, and the authors have unfortunately used the same name (paecilins F–H) for three new paecilin molecules produced by these fungi.

Phomoxanthones A (3) and B (4) belong to the class of xanthones of heterocyclic natural products. Both compounds were previously reported as metabolic products of endophytic strains of Diaporthe spp. (Phomopsis spp.) [15, 21]. Dicerandrol C (5) has similarities with the phomoxanthones, having a dimeric tetrahydroxanthenone skeleton [6]. Dicerandrol C was isolated from the soybean pathogenic fungus Diaporthe longicolla (Phomopsis longicolla) [22]. 8-Hydroxy-6-methyl-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-1-carboxylic acid (8a) and 8-hydroxy-3-methyl-9-oxo-9H-xanthene-1-carboxylic acid (8b), also known as monodictyxanthone, were obtained as a mixture of isomers in a 3:1 ratio. Compound 8a was previously reported from roots of Bulbine frutescens [27], while monodictyxanthone (8b) is a known metabolic product of the fungus Monodictys putredinis, isolated from the inner tissue of a marine green alga [28].

Cytochalasins are a class of structurally related fungal metabolites with broad biological activities, such as antifungal, cytotoxic, and antibacterial properties [44, 45]. Cytochalasins H (6) and J (7) have already been isolated from various fungi, including Endothia gyrosa and Diaporthe spp. [44–48]. 5-Carbomethoxymethyl-2-heptyl-7-hydroxychromone (9) was previously produced by the endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis sp. [29]. Maltol (10), which is mainly known from plants [48], was also previously reported as an actinobacterial metabolite from Streptomyces sp. [49].

Cytochalasin H (6), phomoxantone A (3), phomoxantone B (4), and paecilin Q (1) inhibited the mycelial growth of the plant pathogen P. citricarpa and decreased the formation of pycnidia in citrus leaves, suggesting that these compounds can be used as an alternative to control P. citricarpa (Fig. 3). In regions with high rainfall, such as Brazil, the conidia (asexual spores) are washed down to the adjacent citrus tissues and contribute to the spread of the fungus and the appearance of CBS disease [12]. The inhibition of pycnidia formation is essential to decrease the concentration of conidia in orchards and can be essential in CBS control as well, since conidia dispersion is the most important source of P. citricarpa spread [12, 13].

In addition, cytochalasin H (6) and phomoxanthone A (3) suppressed the hyphal growth and development of CBS lesions in detached fruits (Fig. 3). Although, the pathogen P. citricarpa causes diverse symptoms, the hard spot in citrus fruits, characterized by sunken, pale brown necrotic lesions with a dark reddish brown raised border, is the most common symptom [12, 14]. The presence of severe symptoms on the fruit can result in premature fruit abscission, leading to crop losses [12]. Thus, strategies that impact CBS lesions development, and pycnidia formation has great importance for the citrus culture worldwide.

The two new paecilins (1 and 2) do not show cytotoxic activity against human non-small cell lung A549 and human prostate PC3 cell lines, respectively. Studies with other paecilins also did not reveal cytotoxic activity against human cell lines, but not all compounds have been evaluated yet [30–32,39–43]. Compounds 3, 4, 5, and 6 displayed moderate to high activity against human non-small cell lung A549 and human prostate PC3 cell lines (Fig. 4 and Table 3), respectively. Cytotoxic activity against several other human cancer cell lines have been reported for dimeric tetrahydroxanthone derivatives [15, 21].

In the current study, we found two new compounds, paecilins Q (1) and R (2), produced by the endophytic fungus P. stromaticum CMRP4328. Additionally, we analyzed the antifungal activity of ten compounds produced by P. stromaticum CMRP4328 against the citrus pathogen P. citricarpa. Cytochalasin H (6) showed considerable activity against P. citricarpa, acting on different aspects of the phytopathogen development, inhibiting mycelial growth, pycnidia formation, and the development of lesions of the CBS disease. The new compound paecilin Q (1), showed moderate activity against this citrus pathogen, and no cytotoxic activity. These compounds can be considered promising and should be further investigated for the control of CBS disease.

Materials and Methods

Fungal strains

Strain CMRP4328 was isolated as an endophyte from leaves of the medicinal plant S. adstringens, collected in the Cerrado biome (savanna) (20°18′10.8 “S 56°15′44.3′′ W) in Brazil, in 2018. The isolate was identified as P. stromaticum by phylogenetic analysis of the internal transcribed spacer region (ITS) (MN173204) and translation elongation factor 1-α gene (tef1) partial sequences (MT331613) [5]. P. citricarpa CMRP06 was isolated from Citrus sp. With positive results in a CBS pathogenicity tests [3]. Potato dextrose agar (PDA) media was used for the maintenance of strains. The endophyte and the citrus pathogen P. citricarpa (CMRP06) are deposited in the CMRP Taxonline Microbiological Collections of Paraná Network, at the Federal University of Parana, Brazil (www.cmrp-taxonline.com). The fungal strains used in this work were registered in SISGEN (National System for the Management of Genetic Heritage and Associated Traditional Knowledge) under number A1693BA in compliance with Brazilian Law 13.123/2015. The collection of biological material used in this work was authorized by ICMBio, according to authorization SISBIO (Biodiversity Authorization and Information System) No. 68691.

Fermentation, extraction, and isolation

Isolate CMRP4328 was cultivated in PDA plates at 28 °C for 7 days. Three discs (12 mm each) of the corresponding medium with fungal growth were transferred to Erlenmeyer flasks (250 mL) containing 100 mL of malt extract medium (malt extract 20 g/L, dextrose 20 g/L, peptone 1 g/L). The fermentation (10 L total) was incubated at 28°C on a rotary shaker (180 rpm) for 14 days. The biomass (mycelium) was separated from the culture medium by filtration with Whatman n°4 filter paper. The culture filtrate was mixed with 5% (w/v) XAD-16 resin, stirred overnight, and then centrifuged (5000 rpm) for 10 min. The resin was washed with H2O (3 times) and then eluted in MeOH. The methanol extract was rotary evaporated at 40°C [4] to yield 1.02 g of brown oil crude extract. The extract was separated on a reverse-phase C18 column (25 × 2.5 cm, 250 g) eluted with a gradient of H2O-CH3CN (100 : 0–0: 100). Twenty-one fractions (F1–F21) were combined after TLC and HPLC analysis. Purification of fractions F4–5 (73 mg) by Sephadex LH-20 column chromatography (MeOH; 2.5 × 50 cm) followed by semiprep HPLC yielded compounds 8a/8b (3.1 mg) and 10 (13.7 mg). Similarly, semiprep HPLC purification of F10 (35 mg) afforded compounds 1 (2.2 mg) and 2 (2.3 mg). In the same manner, chromatographic purification of F11 (43 mg) yielded compounds 1 (3.3 mg) and 9 (2.8 mg), F12–13 (75 mg) yielded compounds 6 (13.5 mg) and 7 (10.6 mg), F17 (57 mg) yielded compounds 3 (10.1 mg) and 5 (2.1 mg), F18 (35 mg) yielded compounds 3 (3.8 mg) and 4 (3.7 mg), and F19–21 (53 mg) yielded compound 3(25.0 mg). The other fractions were not further investigated based on TLC and HPLC analyses, since they contained only sugars and other media components (Fig. 1S, Supporting Information).

Paecilin Q (1). C15H16O6; pale yellow solid; UV/vis (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 207 (3.75), 275 (3.42), 350 (2.98) nm (Fig. 3S, Supporting Information); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) and 13C NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz) data, see Tables 1 and 2; (−)-ESI-MS: m/z 291 [M – H]−; (+)-ESI-MS: m/z 293 [M + H] +; (−)-HRESI-MS: m/z 291.0866 [M – H]− (calcd. for C15H15O6, 291.0874); (+)-HRESI-MS: m/z 293.1020 [M + H]+ (calcd. For C15H17O6, 293.1020), 315.0840 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C15H16O6Na, 315.0839) (Figs. 7S–17S, Supporting Information).

Paecilin R (2). C15H16O6; pale-yellow solid; [α]25D + 46.6 (c 1.0, CH3OH); UV/vis (MeOH) λmax (log ε) 208 (3.86), 273 (3.08), 348 (3.12) nm (Fig. 3S, Supporting Information); 1H NMR (CD3OD, 500 MHz) and 13C NMR (CD3OD, 100 MHz) data, see Tables 1 and 2; (−)-ESI-MS: m/z 291 [M – H]−; (+)-ESI-MS: m/z 293 [M + H] +; (−)-HRESI-MS: m/z 291.0867 [M – H]− (calcd. for C15H15O6, 291.0874); (+)-HRESI-MS: m/z 293.1019 [M + H]+ (calcd. For C15H17O6, 293.1020), 315.0839 [M + Na]+ (calcd. for C15H16O6Na, 315.0839) (Figs. 19S–29S, Supporting Information).

The physicochemical properties of compounds 3–10 are listed in the Supporting Information.

Antifungal assays

Mycelial growth inhibition assay

A 100 μL solution of each compound dissolved in methanol (10 mg/mL) was spread over the surface of a petri dish containing PDA medium. One mycelial disc (8 mm) of citrus pathogen P. citricarpa was inoculated in the center of the plates. Plates were incubated in BOD (biochemical oxygen demand) at 28°C with a 12-h photoperiod. The antifungal activity was evaluated after 21 days. To determine inhibition percentage (IP), the diameter of the colonies was measured, and the IP was calculated according to the formula: IP = (mycelial growth in control – mycelial growth in treatment)/mycelial growth in control*100 [3, 5]. The fungicide carbendazim (1.0 mg/mL) was used as the positive control and methanol as the negative control. The experiments were performed in triplicate, and the data were submitted to analysis of parametric variance (ANOVA) with GraphPad Prims v. 6.01.

Inhibition of Phyllosticta citricarpa pycnidia development in citrus leaves

Leaves of Citrus sinensis were thoroughly washed in running tap water, cut into discs [10 mm (Ø)], and autoclaved in distilled water (20 min, 120°C, 1 atm). Three leaf discs were placed in petri dishes with water-agar (1.5% w/v) medium, and 10 μL of a solution of each compound dissolved in methanol (10 mg/mL) were deposited on each leaf fragment. Four discs (2-mm thick) of P. citricarpa CMRP06 mycelia were inoculated on the edge the leaf fragments. The petri dishes were incubated at 28 °C with a 12-h photoperiod for 21 days. After this period, the number of P. citricarpa pycnidia present above the leaves were counted under a stereoscopic microscope. The fungicide carbendazim and methanol were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The experiments were performed in triplicate [5].

Inhibition of citrus black spot development in citrus fruits

Ripe and detached C. sinensis fruits were superficially disinfected and a disc (5 mm) of mycelium of P. citricarpa was introduced into the fruit using creating a wound with a cutting drill. Next, 10 μL of a solution of each compound dissolved in methanol (10 mg/mL) were added to the wounds. The wound was sealed with tape and fruits were kept in a light chamber at 28°C under continuous light. The presence of lesions (fungal growth and the necrotic zone around the lesion) was qualitatively evaluated 21 days after inoculation in comparison to the treatments with the negative control (only methanol) and the positive control (50 μg of the fungicide carbendazim) [3]. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Cytotoxicity assay

The cytotoxicity of compounds was evaluated against A549 (human lung non-small cell carcinoma) and PC3 (prostate adenocarcinoma) human cancer cell lines. The cytotoxicity of compounds was evaluated by measuring the conversion of resazurin (7-hydroxy-10-oxidophenoxazin-10-ium-3-one) into its fluorescent product resorufin. The cytotoxicity IC50 values were obtained after 72 h incubation. Hydrogen peroxide (2.0 mM) and actinomycin D (20 μM) were used as positive controls (0% viable cells), and 0.1% dimethyl sulfoxide was used as a negative control (100% viable cells) [4]. The tests were performed in triplicate. For full details about the cytotoxicity assay, see Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the INCT Citrus CNPq 465440/2014-2 Brazil and CNPq grant 309971/2016-0 and 424738/2016-3 to C.G., CAPES-Brazil - grant to J.I. This work was also supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01 CA243529, R37 AI52218, the Center of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) in Pharmaceutical Research and Innovation (CPRI, NIH P20 GM130456), the University Professorship in Pharmacy (to J. R. and J. S. T.), the University of Kentucky College of Pharmacy, the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center, and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000117 and UL1TR001998). We thank the College of Pharmacy NMR Center (University of Kentucky) for NMR support. J.I. thanks the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for a scholarship.

Footnotes

Supplementary material is available under https://doi.org/10.1055/a-2063-5481

Supporting information

General experimental procedures, cancer cell line viability assay, physicochemical properties of compounds 3–10, workup scheme for compound isolation, UV-vis spectra of compounds 1–5, chemical structures of compounds 11–13, antifungal activity of compounds 2, 5, and 7–10, 1H,1H-COSY, TOCSY, HMBC, and NOESY correlations of compounds 6–10, HPLC/UV, HPLC/MS, HRMS and NMR spectra of all isolated compounds are available as Supporting Information.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Hardoin PR, Van Overbeek LS, Berg G, Pirttila AM, Compant S, Campisano A, Doring M, Sessitsch A. The hidden world within plants: Ecological and evolutionary considerations for defining functioning of microbial endophytes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2015; 79: 293–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Noriler SA, Savi DC, Aluizio R, Palácio-Cortes AM, Possiede YM, Glienke C. Bioprospecting and structure of fungal endophyte communities found in the Brazilian biomes, Pantanal, and Cerrado. Front Microbiol 2018; 9: 1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Savi DC, Noriler SA, Ponomareva LV, Thorson JS, Rohr J, Glienke C, Shaaban KA. Dihydroisocoumarins produced by Diaporthe cf. heveae LGMF1631 inhibiting citrus pathogens. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2020; 65: 381–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Savi DC, Shaaban KA, Gos FMWR, Ponomareva LV, Thorson JS, Glienke C, Rohr J. Phaeophleospora vochysiae Savi & Glienke sp. nov. isolated from Vochysia divergens found in the Pantanal, Brazil, produces bioactive secondary metabolites. Sci Rep 2018; 8: 1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Iantas J, Savi DC, Schibelbein RDS, Noriler SA, Assad BM, Dilarri G, Ferreira H, Rohr J, Thorson JS, Shaaban KA, Glienke C. Endophytes of Brazilian medicinal plants with activity against phytopathogens. Front Microbiol 2021; 12: 2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Rönsberg D, Debbab A, Mandi A, Vasylyeva V, Bohler P, Stork B, Engelke L, Hamacher A, Sawadogo R, Diederich M, Wray V, Lin W, Kassack MU, Janiak C, Scheu S, Wesselborg S, Kurtan T, Aly AH, Proksch JP. Pro-apoptotic and immunostimulatory tetrahydroxanthone dimers from the endophytic fungus Phomopsis longicolla. J Org Chem 2013; 78: 12409–12425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].de Deus Vidal J jr., de Souza AP, Koch I. Impacts of landscape composition, marginality of distribution, soil fertility and climatic stability on the patterns of woody plant endemism in the Cerrado. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 2019; 28: 904–916 [Google Scholar]

- [8].Morey AT, Souza FC, Santos JP, Pereira CA, Cardoso JD, de Almeida RS, Costa MA, Mello JC, Nakamura CV, Pinge-Filho P, Yamauchi LM, Yamada-Ogatta SF. Antifungal Activity of Condensed Tannins from Stryphnodendron adstringens: Effect on Candida tropicalis Growth and Adhesion Properties. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2016; 17: 365–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Baldivia DDS, Leite DF, Castro DTHD, Campos JF, Santos UPD, Paredes-Gamero EJ, Carollo CA, Silva DB, Souza KP, Dos Santos EL. Evaluation of in vitro antioxidant and anticancer properties of the aqueous extract from the stem bark of Stryphnodendron adstringens. Int J Mol Sci 2018; 19: 2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Rahmé GM. Prospecção química em Pseudofusicoccum stromaticum, um fungo Endofítico em Eugenia jambolana (Myrtaceae) [Dissertation]. UNESP: Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sobreira AC, Francisco das Chagas LP, Florêncio KG, Wilke DV, Staats CC, Streit RAS, Freire FCO, Pessoa ODL, Trindade-Silva AE, Canuto KM. Endophytic fungus Pseudofusicoccum stromaticum produces cyclopeptides and plant-related bioactive rotenoids. RSC Adv 2018; 8: 35575–35586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Sposito MB, Amorim L, Bassanezi RB, Yamamoto PT, Felippe MR, Czermainski ABC. Relative importance of inoculum sources of Guignardia citricarpa on the citrus black spot epidemic in Brazil. Crop Prot 2011; 30: 1546–1552 [Google Scholar]

- [13].Guarnaccia V, Gehrmann T, Silva Junior GJ, Fourie PH, Haridas S, Vu D, Statafora J, Martin FM, Robert V, Grigoriev IV, Groenewald JZ, Crous PW. Phyllosticta citricarpa and sister species of global importance to Citrus. Mol Plant Pathol 2019; 20: 1619–1635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Strano MC, Altieri G, Admane N, Genovese F, Di Renzo GC. Advance in citrus post-harvest management: Diseases, cold storage and quality evaluation. J Citrus Pathol 2017; 4: 139–159 [Google Scholar]

- [15].Isaka M, Jaturapat A, Rukseree K, Danwisetkanjana K, Tanticharoen M, Thebtaranonth Y. Phomoxanthones A and B, novel xanthone dimers from the endophytic fungus Phomopsis species. J Nat Prod 2001; 64: 1015–1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Elsässer B, Krohn K, Flörke U, Root N, Aust HJ, Draeger S, Schulz B, Kurtán T. X-ray structure determination, absolute configuration and biological activity of phomoxanthone A. Eur J Org Chem 2005; 2005: 4563–4570 [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ganapathy D, Reiner JR, Valdomir G, Senthilkumar S, Tietze LF. Enantio-selective total synthesis and structure confirmation of the natural dimeric tetrahydroxanthenone dicerandrol C. Chem Eur J 2017; 23: 2299–2302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Choi JN, Kim J, Ponnusamy K, Lim C, Kim JG, Muthaiya MJ, Lee CH. Identification of a new phomoxanthone antibiotic from Phomopsis longicolla and its antimicrobial correlation with other metabolites during fermentation. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2013; 66: 231–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ding B, Yuan J, Huang X, Wen W, Zhu X, Liu Y, Li H, Lu Y, He L, Tan H, She Z. New dimeric members of the phomoxanthone family: phomolac-tonexanthones A, B and deacetylphomoxanthone C isolated from the fungus Phomopsis sp. Mar Drugs 2013; 11: 4961–4972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Frank M, Niemann H, Bohler P, Stork B, Wesselborg S, Lin W, Proksch P. Phomoxanthone A – from mangrove forests to anticancer therapy. Curr Med Chem 2015; 22: 3523–3532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yang R, Dong Q, Xu H, Gao X, Zhao Z, Qin J, Chen C, Luo D. Identification of phomoxanthone A and B as protein tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors. ACS Omega 2020; 40: 25927–25935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wagenaar MM, Clardy J. Dicerandrols, new antibiotic and cytotoxic dimers produced by the fungus Phomopsis longicolla Isolated from an endangered mint. J Nat Prod 2001; 64: 1006–1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cao S, McMillin DW, Tamayo G, Delmore J, Mitsiades CS, Clardy J. Inhibition of tumor cells interacting with stromal cells by xanthones isolated from a Costa Rican Penicillium sp. J Nat Prod 2012; 75: 793–797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hsun-Shuo C Chemical constituents of the endophytic fungus Phomopsis asparagi isolated from the plant Peperomia sui. Chem Nat Compd 2018; 54: 504–508 [Google Scholar]

- [25].Buchanan MS, Hashimoto T, Asakawa Y. Cytochalasins from a Daldinia sp. of fungus. Phytochemistry 1996; 41: 821–828 [Google Scholar]

- [26].Izawa Y, Hirose T, Shimizu T, Koyama K, Natori S. Six new 10-pheynl-[11] cytochalasans, cytochalasins N–S from Phomopsis sp. Tetrahedron 1989; 45: 2323–2335 [Google Scholar]

- [27].Abdissa N, Heydenreich M, Midiwo JO, Ndakala A, Majer Z, Neumann B, Stammler HG, Sewald N, Yenesew A. A xanthone and a phenylanthraqui-none from the roots of Bulbine frutescens, and the revision of six seco-anthraquinones into xanthones. Phytochem Lett 2014; 9: 67–73 [Google Scholar]

- [28].Krick A, Kehraus S, Gerhäuser C, Klimo K, Nieger M, Maier A, Fiebig HH, Atodiresei I, Raabe G, Fleischhauer J, König GM. Potential cancer chemo-preventive in vitro activities of monomeric xanthone derivatives from the marine algicolous fungus Monodictys putredinis. J Nat Prod 2007; 70: 353–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Xu J, Kjer J, Sendker J, Wray V, Guan H, Edrada R, Lin W, Wu J, Proksch P. Chromones from the endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis sp. isolated from the Chinese mangrove plant Rhizophora mucronata. J Nat Prod 2009; 72: 662–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].El-Elimat T, Figueroa M, Raja HA, Graf TN, Swanson SM, Falkinham JO 3rd, Wani MC, Peaerce CJ, Oberlies NH. Biosynthetically distinct cytotoxic polyketides from Setophoma terrestris. European J Org Chem 2015; 1: 109–121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kumla D, Shine Aung T, Buttachon S, Dethoup T, Gales L, Pereira JA, Inácio A, Costa PM, Lee M, Sekeroglu N, Silva AMS, Pinto MMM, Kijjoa A. A new dihydrochromone dimer and other secondary metabolites from cultures of the marine sponge-associated fungi Neosartorya fennelliae KUFA 0811 and Neosartorya tsunodae KUFC 9213. Mar Drugs 2017; 15: 375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Mapook A, Macabeo APG, Thongbai B, Hyde KD, Stadler M. Polyketide-derived secondary metabolites from a Dothideomycetes fungus, Pseudo-palawania siamensis gen. et sp. nov., (Muyocopronales) with antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities. Biomolecules 2020; 10: 569–592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sadorn K, Saepua S, Boonyuen N, Choowong W, Rachtawee P, Pittaya-khajonwut P. Bioactive dimeric tetrahydroxanthones with 2, 2′- and 4, 4′-axial linkages from the entomopathogenic fungus Aschersonia confluens. J Nat Prod 2021; 84: 1149–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Maha A, Rukachaisirikul V, Phongpaichit S, Poonsuwan W, Sakayaroj J. Dimeric chromanone, cyclohexenone and benzamide derivatives from the endophytic fungus Xylaria sp. PSU-H182. Tetrahedron 2016; 72: 2874–2879 [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhang W, Krohn K, Zia U, Florke U, Pescitelli G, Di Bari L, Antus S, Kurtan T, Rheinheimer J, Draeger S, Schulz B. New mono- and dimeric members of the secalonic acid family: Blennolides A–G isolated from the fungus Blennoria sp. Chemistry 2008; 14: 4913–4923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wu G, Yu G, Kurtan T, Mandi A, Peng J, Mo X, Liu M, Li H, Sun X, Li J, Zhu T, Gu Q, Li D. Versixanthones A–F, cytotoxic xanthone-chromanone dimers from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus versicolor HDN1009. J Nat Prod 2015; 78: 2691–2698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Valdomir G, Senthilkumar S, Ganapathy D, Zhang Y, Tietze LF. Enantioselective total synthesis of blennolide H and Phomopsis-H76 A and determination of their structure. Chemistry 2018; 24: 8760–8763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Guo Z, She Z, Shao C, Wen L, Liu F, Zheng Z, Lin Y. 1H and 13C NMR signal assignments of paecilin A and B, two new chromone derivatives from mangrove endophytic fungus Paecilomyces sp. (tree 1–7). Magn Reson Chem 2007; 45: 777–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].da Silva PH, Souza MPD, Bianco EA, da Silva SR, Soares LN, Costa EV, Silva FMA, Barison A, Forim MR, Cass QB, de Souza ADL, Koolen HHF, de Souza AQ. Antifungal polyketides and other compounds from amazonian endophytic Talaromyces fungi. J Braz Chem Soc 2018; 29: 622–630 [Google Scholar]

- [40].Bao J, Sun YL, Zhang XY, Han Z, Gao HC, He F, Qian PY, Qi SH. Antifouling and antibacterial polyketides from marine gorgonian coral-associated fungus Penicillium sp. SCSGAF 0023. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2013; 66: 219–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wei P, Ai HL, Shi B, Ye K, Lv X, Pan X, Ma XJ, Xiao D, Li ZH, Lei X. Paecilins F–P, new dimeric chromanones isolated from the endophytic fungus Xylaria curta E10, and structural revision of paecilin A. Front Microbiol 2022; 13: 922444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Gu G, Zhang T, Zhao J, Zhao W, Tang Y, Wang L, Cen S, Yu L, Zhang D. New dimeric chromanone derivatives from the mutant strains of Penicillium oxalicum and their bioactivities. RSC Adv 2022; 12: 22377–22384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Carvalho CD, Ferreira-DʼSilva A, Wedge DE, Cantrell CL, Rosa LH. Anti-fungal activities of cytochalasins produced by Diaporthe miriciae, an endophytic fungus associated with tropical medicinal plants. Can J Microbiol 2018; 64: 835–843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Ma Y, Xiu Z, Zhou Z, Huang B, Liu J, Wu X, Li S, Tang X. Cytochalasin H inhibits angiogenesis via the suppression of HIF-1α protein accumulation and VEGF expression through PI3K/AKT/P70S6K and ERK1/2 signaling pathways in non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Cancer 2019; 10: 1997–2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Xu S, Ge HM, Song YC, Shen Y, Ding H, Tan RX. Cytotoxic cytochalasin metabolites of endophytic Endothia gyrosa. Chem Biodivers 2009; 6: 739–745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chapla VM, Zeraik ML, Ximenes VF, Zanardi LM, Lopes MN, Cavalheiro AJ, Silva DH, Young MC, Fonseca LM, Bolzani VS. Bioactive secondary metabolites from Phomopsis sp., an endophytic fungus from Senna spec-tabilis. Molecules 2014; 19: 6597–6608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Xiu Z, Liu J, Wu X, Li X, Li S, Wu X, Lv X, Ye H, Tang X. Cytochalasin H isolated from mangrove-derived endophytic fungus inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer stemness via YAP/TAZ signaling pathway in non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Cancer 2021; 12: 1169–1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Williams M, Eveleigh E, Forbes G, Lamb R, Roscoe L, Silk P. Evidence of a direct chemical plant defense role for maltol against spruce budworm. Entomol Exp Appl 2019; 12: 755–762 [Google Scholar]

- [49].Cheng C, Othman EM, Stopper H, Edrada-Ebel R, Hentschel U, Abdel-mohsen UR. Isolation of petrocidin A, a new cytotoxic cyclic dipeptide from the marine sponge-derived bacterium Streptomyces sp. SBT348. Mar Drugs 2017; 15: 383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.