Abstract

BACKGROUND

Gratitude, empathy and humility have been defined as personality dispositions, as complex interpersonal emotions, and as states that prompt people to be more pro-social. However, studies on the associations between these emotions and authenticity are scarce. The main purpose of this study was to analyze the mediation effect of gratitude and empathy on the association between humility and perceived false identity.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

The number of participants who took part in the survey was equal to 220 university students (91% female). Students completed questionnaires concerning humility (BSHS scale), gratitude (GQ scale), empathy (QCAE inventory), and perceived false self (POFS scale).

RESULTS

The results confirmed significant correlations between gratitude, empathy and authenticity, but not with humility. Further analysis revealed that gratitude and affective and cognitive empathy explain 9% of the perceived false identity level. The findings confirmed the mediation effect of gratitude on the associations between (1) humility and false self, (2) affective empathy and false self, but not between cognitive empathy and false self. The results also indicated that humility may influence authenticity indirectly via gratitude, but not via dimensions of empathy.

CONCLUSIONS

The findings confirm the significance of gratitude and cognitive empathy as dispositions that promote a feeling of being authentic. On the other hand, the relationship between affective empathy and false self was positive.

Keywords: gratitude, humility, empathy, perceived false self

BACKGROUND

Humility, gratitude, and empathy are defined as character strengths, as factors shaping interpersonal relations. Particularly, all of them encourage individuals to present behaviors that benefit others at a variety of costs to the self, not only in materials terms but also in terms of devoted time or personal effort spent on helping (Gurnani & Sethia, 2019; Lishner et al., 2016; Xiao et al., 2021). Their definitions suggest that feeling them enriches knowledge about oneself as well as increasing personal growth (Derksen et al., 2021; Homan & Hosack, 2019; Jafari, 2020). Despite the unquestionable conceptual connections between these emotions, studies on the associations between them have received insufficient attention. Moreover, the relationship between these emotions and false self-construct has not been examined yet in Poland.

HUMILITY, GRATITUDE AND EMPATHY – THE THEORETICAL BACKGROUND OF THE CURRENT STUDY

Humility was defined as the dispositional quality of an individual, a hypoegoic state that includes a specific attitude to oneself indicated by a decrease in self-focus, e.g. the reflection that something or someone greater than the self exists (Frostenson, 2016; Nielsen & Marrone, 2018). Humility is connected with lack of arrogance in relation to others. According to Davis et al. (2012), humility is not something possessed by an individual per se, but is an interpersonal judgment about the person that we create. Humility is an emotion that is important in both self-knowledge and the effectiveness in building relationships (Albrecht, 2015). Wright et al. (2018) distinguished two dimensions of humility, e.g. low self-focus and high other focus. Humility is built from four components: accurate self-awareness, appreciation of others, openness to feedback, and transcendence perspective (Nielsen & Marrone, 2018). However, Kruse et al. (2017) posited that humility fluctuates over time depending on social contexts. The state approach to humility research makes it possible to explore whether the dynamics in humility change the individuals’ behaviors (ego-inflating actions) or emotional responses (e.g. expressing gratitude or empathy) to a variety of life or daily events, or a combination of these factors and other individual characteristics. Therefore, in the current study, the momentary humility conceptualization was applied.

Gratitude is understood as a sense of thankfulness and joy for what one possesses, and it is experienced when people receive something valuable and beneficial (Emmons & McCullough, 2004). Additionally, gratitude refers to the awareness of a positive personal outcome that was freely bestowed upon the individual by others (Bono et al., 2004) and which in turn increases later prosociality (Oliveira et al., 2021). The most often used measurement of gratitude – the Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ) proposed by McCullough et al. (2002) – captures mostly its emotional component. In this approach, gratitude is “a generalized tendency to recognize and respond with grateful emotion to the roles of other people’s benevolence in the positive experiences and outcomes that one obtains” (McCullough et al., 2002, p. 112). As the current study mostly tries to examine the associations between positive emotions and false self, McCullough and colleagues’ gratitude emotional perspective was applied.

Empathy “bridges the gap between self-experience and that of others” (Wilkinson et al., 2017, p. 19). This complex emotion predicts whether an observer would provide help when confronted with a request to do so, but also as an altruistic, fully voluntary gesture when help is needed, although the beneficiary does not ask for it (Nowakowska, 2022). Reik’s model of the empathy process includes identifying with the interlocutor, incorporating the other person’s emotions, understanding the other’s emotions, and separating oneself from them (Reik, 1948, as cited in Mora-Pelegrín et al., 2021). More specifically, experiencing empathy requires the emergence of three core processes: (1) an emotional process defined as sharing someone’s emotion, (2) a cognitive process indicating that the person is capable of taking the other’s perspective, and (3) a motivational process of showing and feeling compassion and wanting to help (Hall & Schwartz, 2019). The multidimensional approach to empathy with affective (the ability to experience and share the emotions of others) and cognitive dimensions (the ability to understand the emotions of others) (Reniers et al., 2011) is most common in empirical studies and was used in the current project.

HUMILITY, GRATITUDE AND EMPATHY – THE EVIDENCE FOR INTERRELATIONSHIPS

Kruse et al. (2014) confirmed the strong mutual association between humility and gratitude, i.e. “practicing gratitude fosters humble thoughts and feelings, which, in turn, may promote even more gratitude, which further boosts humility, and so on” (Kruse et al., 2014, p. 817). Johnson (2019) believes that empathy requires intellectual humility and that it is impossible to imagine emotional states of others without it. Humility also encourages people to adopt another’s perspective and act in an other-enhancing way (Hendijani & Sohrabi, 2019). In other words, it helps to diminish the impact of the self-centered perspective when we analyze and make social judgments about others. Past studies also indicated the positive relation between empathy and gratitude (Lasota et al., 2020). The abovementioned findings suggest that humility may facilitate an empathetic perspective and the feeling of gratitude.

THE PSYCHOLOGICAL VIEW OF AUTHENTICITY

Rivera et al. (2019) discussed authenticity in two ways: (a) a veridical objective approach, determining whether the person really is living/behaving authentically, according to objective standards, and (b) a non-veridical subjective approach (perceived authenticity), in which the judgments about authenticity are derived, and the subjective state comes from the question whether the person feels authentic. Based on this approach, Weir and Jose (2010) defined the perceived false self as the inauthenticity observed in behaviors caused by social demands. In the current study, the subjective veridical approach to authenticity was used, as the participants assessed their feeling of being inauthentic. In this view the false self is two-dimensional, comprising (1) the false self, which refers to hiding true thoughts, beliefs, feelings, and motives in social situations, and (2) social concern, which refers to behaviors in which a person desists from presenting their own beliefs and behaviors because of external social norms and standards. Harter et al. (1996, p. 360) claimed that lack of authenticity is “the extent to which one is acting in ways that do not reflect one’s true self as a person”, or the ‘real me’.

AUTHENTICITY AND EMPATHY

According to Bialystok and Kukar (2018), authenticity and empathy are engaged in a give-and-take relationship; however, they are not fully actualized at the same time. Empathy promotes social orientation and cooperation; thus people may hide true thoughts and feelings to avoid social conflicts (Rumble et al., 2009). Moreover, family members’ empathy may facilitate the quality of social interactions and increase the influence of others on a person’s behaviors and judgments (Michałek-Kwiecień, 2020). In addition, pro-social orientation may facilitate the ability to take the perspective of others, recognize their feelings, and empathize with their emotional states. In this context, it is worth mentioning the dual empathy in couples, which highlights the role of other-oriented focus (Kaźmierczak & Karasiewicz, 2021). Thus, fear of losing positive relationships with relatives may encourage one to hide true beliefs and thoughts. However, studies give mixed results in this area.

AUTHENTICITY AND HUMILITY

Humble persons are characterized by a self-regulatory capacity that fosters pro-social tendencies (Owens et al., 2013). Humility mitigates human vices, e.g. hubris, arrogance, egoistic attitude, self-aggrandizement (Nielsen & Marrone, 2018). Therefore, humility is usually recognized by an accurate or balanced self-concept, and the ability to notice others’ worth (Kruse et al., 2014). A humble person is capable of acknowledging and accepting their own limitations and weaknesses, as well as of seeking diverse feedback (Nielsen & Marrone, 2018). Moreover, even if they receive negative feedback, which is usually connected to experiencing a significant ego threat, humble people can appreciate this and do not self-disparage themselves (Kruse et al., 2014). This is because humility is strongly related to an affirmed and secure identity and „forgetting of the self” (Tangney, 2000). To a certain extent, this may also promote being more authentic as the humble person accepts their weaknesses and does not try to present themselves as someone else.

AUTHENTICITY AND GRATITUDE

Homan and Hosack (2019) stated that gratitude amplifies the good in people’s lives because this emotion strengthens the ability to see the good in themselves (e.g. people are more aware of their own personal qualities and resources). As a result, the individual’s self-compassion and self-acceptance increase. The authors found that gratitude also guides people to search for good things in others. What is more, according to the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, such emotions broaden individuals’ modes of momentary thought and behavior repertoire, and as a consequence people’s thinking and behavior are more flexible when necessary (Fredrickson, 2004). In addition, individuals are able to appreciate the present moment as something that is given them and can develop new perspectives of self and the world by integrating all benefits (Kardaş & Yalçin, 2021). Among the broadening aspects of human life stemming from positive emotions such as gratitude are enriched psychological resources, e.g. developing identity and sense of orientation (Fredrickson, 2004). Some of the past studies confirmed that gratitude strengthens the individual’s positive beliefs about self and increases self-esteem (Li et al., 2012). Therefore it should also encourage people to show their true thoughts, feelings and behaviors in public situations, that is to be more authentic.

THE PRESENT STUDY

To date, only a few studies have explored the relationships of humility, empathy and gratitude with self construct indicators. In addition, none of them examined all these variables together. Thus, this study aimed to examine four hypotheses:

H1: High humility and gratitude and low empathy will predict a lower level of perceived false self.

As mentioned in the introduction, humility and gratitude strengthen self-worth and authenticity (Homan & Hosack, 2019; Kruse et al., 2014), while empathy increases the interpersonal orientation, which may cause a tendency to hide true feelings and beliefs in social situations.

H2: Humility will directly and indirectly predict the level of perceived false self via gratitude.

The upward spiral between humility and gratitude indicates that gratitude may be considered as an antecedent of humility and vice versa, and that humility may enhance the awareness of social resources via externally focused emotions such as gratitude (Kruse et al., 2014). It is also worth noting that humility is related to low self-focus and enables people to focus on other people and on the world around them (Kruse et al., 2017). This may help in taking a broader perspective that allows one to perceive and appreciate the good that man has received from others but also from force majeure, e.g. God, nature, or fate. In addition, Hussong et al. (2019) defined gratitude as a cognitively mediated, socio-emotional process that refers to a feeling of appreciation, happiness, or joy because of gift/benefit, that is not due to personal effort but to a benefactor’s free and unrestricted intentions to give. Such an external focus and pro-social perspective seem to be linked to a shift away from an egoistic orientation. Considering that both gratitude and humility make people re-examine what they know about themselves, to accept their weaknesses and to acknowledge personal strengths, such conditions may encourage them to be more authentic.

H3: Gratitude will mediate the association between empathy and perceived false self.

Because gratitude requires the ability to recognize human emotions and connect them properly to social situations (Nelson et al., 2013), it may serve as a mediator between the emotions that reinforces not overestimating self-worth and openness to others (e.g. humility) (Spezio et al., 2019) and the ability to understand emotions of others (e.g. empathy) appearing in the interpersonal context. More specifically, understanding of gratitude involves an understanding of the mental state of the other person, e.g. the benefactor (Tudge et al., 2015). Such a process requires the cognitive ability to identify and understand other people’s emotions and an altruistic motivation. The positive judgment and emotions aimed at and concerning the other person can create conditions in which the person feels accepted enough, which may encourage him/her to reveal individual true emotions and beliefs. As such, the perceived authenticity may increase.

H4: Humility will directly and indirectly predict perceived false self through empathy.

The theoretical justification for the direct relationship between the state of humility and perceived false self came from the common observation that the emotional states interfere with self-judgments and behaviors. More specifically, the emotion-as-direct-causation asserts that current emotions guide behavior and judgment, and vice versa (DeWall et al., 2016). Affective states motivate people to authenticity (Lenton et al., 2012). Past studies have confirmed that self-judgments of authenticity are affected by several factors, e.g. the positivity of the behavior and the stringency of their construals of authenticity (Jongman-Sereno & Leary, 2020). Moreover, the self-concordance model proposed by Sheldon and Elliot (1998) posited that people are authentic if there is a fit between their situational goal strivings and their personal values. The lack of congruency (the lack of correspondence between implicit and explicit motives) is connected to lower emotional well-being (Schultheiss & Brunstein, 2010). As such, also momentary emotions may be related to fluctuation in false self. The mediation effect of empathy on the association between humility state and false self is related to a theory of relational humility. This construct is defined as the perception of another person that consists of two judgments: (a) whether the person is other-oriented, rating the ability to act modestly by regulating self-oriented emotions and inhibiting socially off-putting expressions of those emotions; (b) whether the person has realistic self-esteem, rating the accuracy of self-view. This approach asserts that humility promote strengthening social bonds, leads to greater group acceptance, and can help repair relationships because it involves integrity of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and motivational qualities (Davis et al., 2012). The conditions described above are also important in feeling and expressing empathy, as at the same time, to feel empathy, an individual must recognize another person’s emotional state, have an ability to share these feelings and the motivation to be compassionate (Hall & Schwartz, 2019). Since empathy is a pro-social emotion, it usually results in reactions to meet the needs of the object of empathy according to one’s own opinion (Depow et al., 2021). In other words, adaptive empathy allows us to learn according to others’ needs and adjust our own empathic response based on feedback (Kozakevich et al., 2021). Because humility encourages people to notice others’ meaning by diminishing egoistic perspective (Kruse et al., 2014), it was expected that it may reinforce the cognitive ability to think about, understand, and sympathize with other people’s mental states. Such empathetic orientation increases social connectedness (Depow et al., 2021). However, it may in turn create the conditions not to reveal one’s true self for fear of spoiling close relationships with others (see Figure 1).

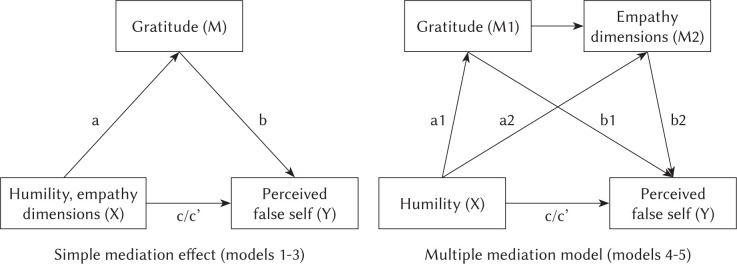

Figure 1.

Theoretical models of tested relationships between positive emotions and perceived false self

Note. a-a2, b-b2, c/c’ – testing paths

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The participants were university students from the fields of pedagogy, therapy and psychology in their 2nd, 3rd and 5th years of study, with a majority of women (n = 200, 91% of the sample) and aged M = 24.05 years, SD = 5.28.

PROCEDURE

The study was conducted in 2020 (paper-pencil method of collecting data with n = 111 students) and in 2021 (online data collection with n = 109 students). All participants provided informed consent before completing the survey. Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Institute of Psychology at the Pedagogical University of Krakow (no. 1/09/2021).

MEASUREMENTS

Brief State Humility Scale (BSHS) by Kruse et al. (2017). The scale is a 6-item tool to measure momentary humility (e.g. “I feel that I do not have very many weaknesses”). The participants answer the question how they feel at the moment and rate each item from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). However, the 3-item Polish version was used in the current research project, because of good psychometric properties (e.g. EFA: 58.35% of the explained variances, loadings ranged from .46 to .88; reliability: α = .60, ɷ = .68).

Cognitive and Affective Empathy Questionnaire (QCAE) by Reniers et al. (2011) in the Polish version by Lasota et al. (2020). The QCAE scale consists of 31 items that measure two main components of empathy: cognitive (e.g. “I can sense if I am intruding, even if the other person does not tell me”), and affective (e.g. “I am happy when I am with a cheerful group and sad when the others are glum”). The participants respond on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (I disagree) to 4 (I agree).

The Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ; McCullough et al., 2002) is a 6-item scale (e.g. “I am grateful to a wide variety of people”) with a 7-point Likert scale rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree) (Kossakowska & Kwiatek, 2014).

Perceptions of False Self (POFS; Weir & Jose, 2010) is a scale composed of 16 items scored using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale captures how much a person reacts in line with perceived external standards rather than self-generated internal standards (e.g. “I say what I think even if it is different to the opinion of others”). The Polish version of the POFS scale was used in this study because of good psychometric properties (EFA with one factor solutions: 35% of the explained variances in perceived false self, loadings ranged from .25 to .74, only two items did not reach the statistical criteria for loadings over .40, i.e. item 15 (.25), and item 16 (.33); reliability: α = .83, ɷ = .86).

DATA ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics (M, SD, Pearson’s correlation) were calculated for continuous variables to describe the sample’s characteristics. Linear regression was used to test the predictive power of gratitude, empathy and humility (independent variables) for false self (dependent variable). Process Macro v. 3.3 by Hayes (2013) was used to examine the mediation effects (model 4, 6). SPSS (vs. 22.0) was employed for data evaluation. The JASP package was used to calculate the reliability of the scales. A Monte Carlo power analysis for indirect effects with two parallel mediators was performed (Schoemann et al., 2017). The power of 0.82 (p < .05) was reached with 180 participants (for conditions: (a) r = .04 between: X-Y variables; X-M1; Y-M1, and M1-M2; (b) r = .02 between X-M2; Y-M2).

RESULTS

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN POSITIVE EMOTIONS AND PERCEIVED FALSE SELF

The skewness and kurtosis indicated a normal distribution for all variables. The Pearson’s analysis revealed that the humility is positively related only to gratitude. The false self negatively correlated with gratitude and cognitive empathy, but not with humility and affective empathy. Gratitude was positively associated with both empathy dimensions. Affective empathy and cognitive empathy were correlated positively with each other. All of the correlations were low (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations (N = 220)

| Variables | Min./max. | M | (SD) | Skewness | Kurtosis | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | α/ ɷ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Humility state | 7/21 | 16.25 (3.22) | –.55 | .03 | – | .60/.68 | |||||

| 2. Gratitude | 11/42 | 33.08 (6.22) | –.93 | .67 | .16* | – | .80/.82 | ||||

| 3. Perceived false self | 22/71 | 42.26 (9.33) | .37 | –.01 | .01 | –.24*** | – | .83/.86 | |||

| 4. Cognitive empathy | 37/75 | 56.73 (7.80) | .03 | –.53 | .03 | .14* | –.15* | – | .88/.88 | ||

| 5. Affective empathy | 20/47 | 36.03 (4.86) | –.24 | .12 | .07 | .23*** | .08 | .23** | – | .73/.75 | |

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

As expected, higher gratitude and both empathy dimensions (but not humility) were predictors of a lower false self and explained 9% of the variances in POFS (F(4, 214) = 6.08, p < .001, R2 = .10, adj. R2 = .09) (H1 was partially supported) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Positive emotions as predictors of perceived false self

| Independent variables | B | SE | β | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LL | UL | ||||

| Humility state .11 | .19 | .04 | –.26 | .49 | |

| Gratitude –.41 | .10 | –.27*** | –.61 | –.21 | |

| Cognitive empathy –.18 | .08 | –.15* | –.34 | –.02 | |

| Affective empathy .33 | .13 | .17* | .07 | .59 | |

| Summary of the regression model: F(4, 214) = 6.08, p < .001, R2 = .10, adj. R2 = .09 | |||||

Note. *p < .05, ***p < .001; LL – lower bound 95% confidence interval; UL – upper bound 95% confidence interval; Durbin-Watson test for the regression model = 2.03.

BASIC MEDIATION EFFECTS OF GRATITUDE ON THE ASSOCIATIONS OF HUMILITY AND DIMENSIONS OF EMPATHY WITH PERCEIVED FALSE SELF (MODELS 1-3)

Gratitude was positively associated with two independent variables, i.e. humility and affective empathy, but not with cognitive empathy (paths a). As expected, in all three tested models, the mediator was negatively related to the dependent variable (path b). Furthermore, the significant relationship between cognitive empathy and perceived false self became insignificant (model 2, path cʹ), and the insignificant association between affective empathy and false self became significant (model 3, path cʹ) after inserting the mediator. Judging by the effects of the mediator on the association between humility and affective empathy and perceived false self, we can see that the abovementioned simple mediations were confirmed. The relationship between independent and dependent variables was higher in models 1 and 3 (path cʹ). However, the indirect effect of cognitive empathy on false self via gratitude was insignificant. Thus, H2 and H3 were partially confirmed (see Table 3, Figures 2-4).

Table 3.

Indirect effects from simple mediation models by bootstrap method (models 1-3)

| Number of model | Path | Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | β | SE | LL UL | |||

| Model 1 | Humility → Gratitude → Perceived false self | –.11 | –.04 | .02 | –.08 | –.01 |

| Model 2 | Cognitive empathy → Gratitude → Perceived false self | –.04 | –.03 | .02 | –.08 | .01 |

| Model 3 | Affective empathy → Gratitude → Perceived false self | –.12 | –.06 | .03 | –.13 | –.01 |

| Model 4 | Humility → Gratitude → Perceived false self | –.10 | –.04 | .02 | –.08 | –.004 |

| Humility → Cognitive empathy → Perceived false self | .00 | .00 | .01 | –.02 | .02 | |

| Humility → Gratitude → Cognitive empathy → Perceived false self | –.01 | –.002 | .00 | –.01 | .00 | |

| Model 5 | Humility → Gratitude → Perceived false self | –.13 | –.04 | .02 | –.09 | –.01 |

| Humility → Affective empathy → Perceived false self | .01 | .01 | .01 | –.01 | .03 | |

| Humility → Gratitude → Affective empathy → Perceived false self | .01 | .01 | .004 | –.0001 | .02 | |

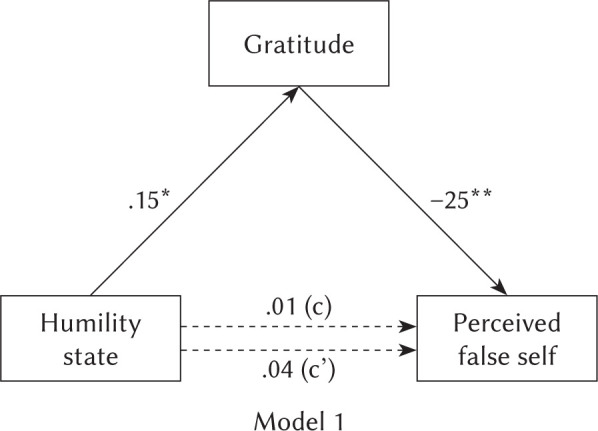

Figure 2.

Simple mediation effect of gratitude on the relationship between humility and perceived false self

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01.

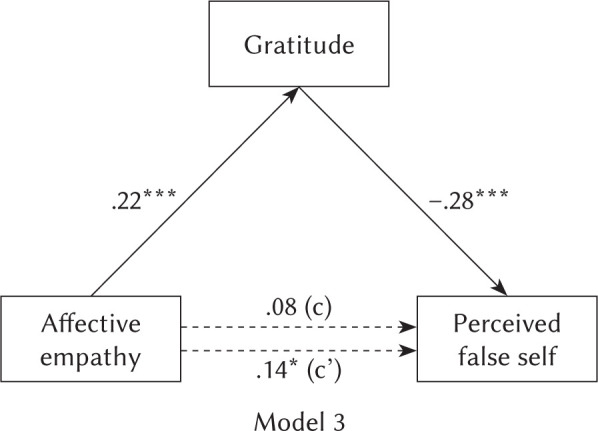

Figure 4.

Simple mediating effect of gratitude on affective empathy and perceived false self relationship

Note. *p < .05, ***p < .001.

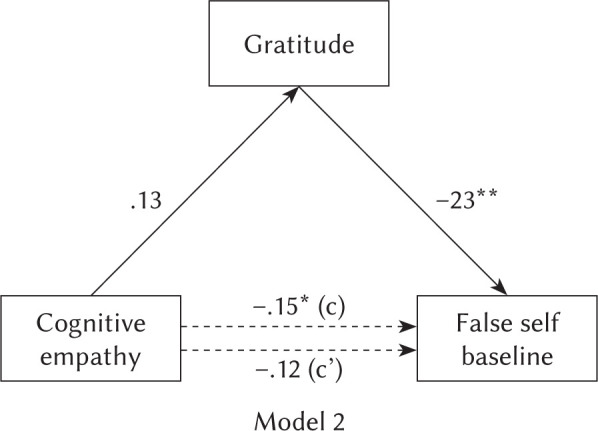

Figure 3.

Cognitive empathy indirect effect on perceived false self via gratitude

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01.

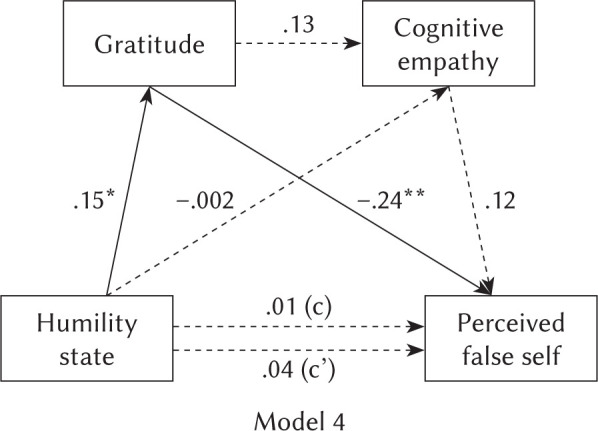

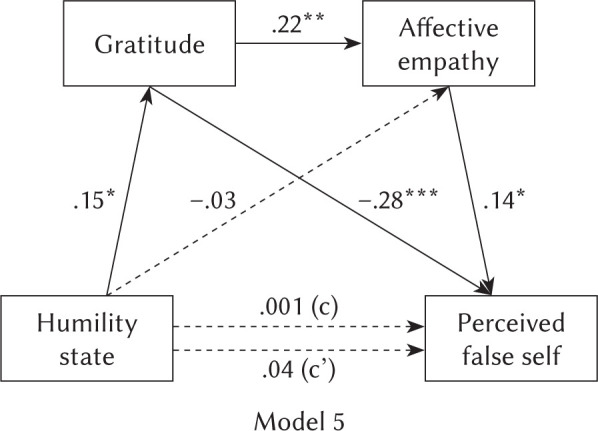

MEDIATION EFFECTS OF GRATITUDE AND EMPATHY ON THE ASSOCIATION BETWEEN HUMILITY AND PERCEIVED FALSE SELF (MODELS 4-5)

Two multiple mediation models with two mediators, namely (1) gratitude and cognitive empathy (2) gratitude and affective empathy, were examined. Both were found to be significant (F(3, 215) = 5.83, p < .001, R2 = .07; F(3, 215) = 6.27, p < .001, R2 = .08).

In model 4, the direct effect (B = .12, p = .509, 95% CI [–.25; .51]) of humility on perceived false self was at an insignificant level. The direct path from humility to gratitude (B = .29, β = .15, p = .023, 95% CI [.04; .55], path a1) was significant, but the path to cognitive empathy (B = –.004, β = –.002, p = .979, 95% CI [–.33; .32], path a2) was insignificant. The path from the first mediator (gratitude) to the second (cognitive empathy) was also insignificant (B = .16, β = .13, p = .065, 95% CI [–.01; .33]). The path from the mediator to false self, namely, from gratitude (B = –.36, β = –.24, p < .001, 95% CI [–.55; –.16]) was significant (path b1) and from cognitive empathy (B = –.14, β = –.12, p = .073, 95% CI [–.30; .01]) was insignificant (path b2). The indirect effect of humility on perceived false self (1) via gratitude was at a significant level (B = –.10, β = –.04, 95% CI [–.08; –.004]), (2) via cognitive empathy (B = .00, β = .00, 95% CI [–.02; .02]) was insignificant, (3) and via gratitude and cognitive empathy (B = –.01, β = –.002, 95% CI [–.01; .00]) was insignificant (see Table 3, Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Mediation effect of gratitude and cognitive empathy on the association between humility and perceived false self

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01.

In model 5, the direct effect of humility on perceived false self (B = .11, p = .552, 95% CI [–.26; .49]) and the relationship between the independent variable and affective empathy (B = .05, β = .03, p = .562, 95% CI [–.15; .25], path a2) were insignificant. The paths between humility and gratitude (B = .29, β = .15, p = .023, 95% CI [.04; .55], path a1) and between gratitude and affective empathy (B = .17, β = .22, p = .001, 95% CI [.07; .27]) were significant. The associations between both mediators and the dependent variable were at a significant level (path b1: B = –.42, β = –.28, p < .001, 95% CI [–.63; –.22]; and path b2: B = .27, β = .14, p = .036, 95% CI [.02; .53], respectively). The indirect effect of humility on perceived false self via (1) gratitude was significant (B = –.13, β = –.04, 95% CI [–.09; –.01]), (2) affective empathy was insignificant (B = .00, β = .00, 95% CI [–.01; .03], and (3) gratitude and affective empathy was insignificant (B = .00, β = .01, 95% CI [–.0001; .02]. H4 was confirmed only with regard to the indirect effect of humility on perceived false self via gratitude (see Table 3, Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Mediation effect of gratitude and affective empathy on the association between humility and perceived false self

Note. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

DISCUSSION

The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions assumes that the feeling of positive affective states supports human functioning in many areas, including developing personal resources. Following this thesis, the present study investigated the associations between gratitude empathy, humility, and perceived false identity.

Higher gratitude and cognitive empathy and lower affective empathy predicted lower false self. Humility was found to be an insignificant predictor. These findings suggest that feeling empathy may negatively affect one’s own behavior by discouraging individuals from revealing their true beliefs and emotions; however, the cognitive process of identifying others’ emotions had an opposite effect. Past studies have produced mixed results for characteristics that are correlated with empathy. For example, some studies have confirmed that empathy is connected to positive outcomes (e.g. increase in well-being, decrease in depression), while other findings suggest that it leads to burnout and social withdrawal, hyper-competition or immorality (Depow et al., 2021). The results of this study are consistent with the Depow et al. (2021) conclusions, that people, even though they notice other people’s emotional states, are not always willing to empathize with them. Therefore, the process of empathy often is not completed (lack of affective and motivational stages). As a result, the person, although recognizing other people’s emotions, ignores them, which may be associated with presenting artificial, inauthentic reactions, e.g. uttering clichés instead of showing true feelings. As such, the perceived false self may increase.

According to the results, humility was associated with perceived false self only indirectly via gratitude. The insignificance of the direct effect of state humility on false self is surprising. The findings may be related to the dark side of this feeling. Expressing humility may have a detrimental effect on personal resources. For example, Yang et al. (2019) found that it may lead to emotional depletion, adverse work-related outcomes (i.e. turnover intentions), and work-to-family conflicts. As such, humility may also affect other personal resources e.g. self-judgments. Expressing the feeling of humility may be suppressed due to different motives. For example, Roberts et al. (2021) found that individuals often hide their successes from close relatives (react in a too humble way) because of paternalistic motives. Unfortunately, suppressing humility has negative relational costs and leads people to negative feelings and resource loss. Furthermore, social standards about expressing vs. suppressing humility are not clear. On the one hand, exaggerated self-promoting behaviors are often negatively assessed by society, which is related to the rule “it is not nice to brag”. On the other hand, some social norms upgrade assertive behaviors in which the person appreciates her/his success, and hiding the feeling of self-pride may be perceived as not authentic (“false modesty”). As such, the social standards may lead to either being too humble or hiding humility. This may interfere with either the tendency to deny this feeling or express it. Both may affect personal judgments in different ways. Additionally, humility is a complex construct and depends on people’s general ethical orientation, autonomy, life goals, religious practices, and reactions to disagreement (Wright et al., 2018). These factors were not controlled for in the current study, but they might be important in determining why state humility is not directly associated with perceived authenticity.

The indirect relationship between humility and false self via gratitude is partially consistent with empirical evidence that humility may play a key role (antecedent, mediator or consequence) in feeling positive emotions such as gratitude (Kruse et al., 2017). Layous et al. (2017) confirmed that this emotional state mediates the association between gratitude and motivation to become a better person by increasing the belief that one deserves the help of a benefactor. However, Kruse et al. (2014) identified humble feelings as a state that facilitates greater sensitivity to gratitude. Specifically, it activates a more other-oriented perspective in social situations. Moreover, induction of gratitude, which promotes external focus and inhibits internal focus, can increase humility, because this emotion also decreases self-focus (Kruse et al., 2014). In the light of this study, momentary humility through higher gratefulness may manifest itself as a behavior change consisting of the tendency to show real emotions, beliefs, or thoughts. In other words, humility may enhance the individual’s reactions in line with perceived self-generated internal standards but only by reinforcing a grateful attitude. This effect may be related to the beliefs about who we actually are in different social settings. The self-perception may be “incongruent and in order to decrease self-discrepancy, individuals have to regulate or modify their perceptions, feelings, and actions to change their self-views according to the particular feedback or with the standards of desired behavior” (Mestvirishvili & Mestvirishvili, 2021, p. 31). Humility can facilitate behaviors consistent with the ideal self (i.e. reducing egoistic attitude and arrogance) and gratitude may increase self-reflection of social roles and people’s reactions and thereby encourage responses in a more authentic way.

As expected, gratitude mediated the association between affective empathy and perceived false self. However, the indirect relationship between cognitive empathy and perceived false self via gratitude was not confirmed. Past studies also revealed differences in two empathy facets in relation to psychological characteristics and correlates. For example, the emotional component of empathy was found to increase the tendency to feel and share the other person’s negative states (distress), which can lead to negative psychological outcomes, e.g. empathy burnout (Decety & Fotopoulou, 2014). In contrast, a high ability to identify and understand another person’s affects usually leads to more effective helping strategies (Hua et al., 2021). One explanation of these different patterns may lie in self-consciousness. According to Luan and Chen (2020), feeling empathy is mostly related to private self-consciousness, which indicates that the person activates the process of moral values in choosing the way of helping others. Similarly, the classical concept of gratitude defined it as a moral affect (McCullough et al., 2001). The activation of moral judgments indicated by gratitude seems to be also associated with the tendency to behave according to private standards. This is because gratitude may force individuals to re-evaluate their own life/past opinions about people, which in turn may lead to discovering a positive balance in previous positive and negative experiences. Therefore, the person may be more willing to show authentic reactions. On the other hand, a grateful person may want to behave in a way which corresponds with the ideal self concept, because thinking about what good they have received so far in their life may also induce the behavioral tendency to react in accordance to what kind of person they would like to be. In this context, it is also worth noting that ideal-self contents are more accessible for people high in private self-consciousness (Falewicz & Bąk, 2016), and both empathy and gratitude are related to higher awareness of one’s self and social relations in which individuals are embedded.

Interestingly, affective empathy was positively related to the perceived false self. Empathy often takes place in problematic situations in which a person experiences difficult emotions. The empathetic person is then faced with the task of supporting the interlocutor. However, even in professional help relationships, there is a dilemma whether to show true emotions, sometimes negative (e.g. anxiety, helplessness), or hide them. This is because the person providing the support by expressing true feelings builds closeness and a sincere atmosphere. On the other hand, expressing real emotions may be overwhelming to the person in need. According to Orange (2002), there is an incompatibility of the empathic understanding which was described by this author with two main questions: Does remaining close to the patient’s emotional perspective require the analyst to become dishonest or inauthentic? Or conversely, does authentic participation require an emotional distance incompatible with empathic understanding? In other words, to effectively support someone, do we need to be dishonest and hide true emotions (suppressing the affective empathy), and focus only on understanding the other person’s emotions (heightened cognitive empathy)? Although the author believes that this is only an apparent contradiction and authenticity and empathy are compatible, the question of the relationship between these constructs still requires in-depth research. Similarly, the current study does not allow us to answer the above questions.

The present study contributes to the existing literature about authenticity in several ways. First, this is the first research to examine altogether gratitude, empathy, humility and the perceived discrepancy in self-view. Moreover, the findings highlighted the important role of gratitude in linking other emotional states with self-judgments. This study also partially confirmed that expressing humility (in the sense of admitting that this is the feeling that I feel at the moment) is related to a higher tendency to express gratitude and only in this condition promote the feeling of authenticity. Lastly, the results shed some light on the complex relationship of empathy dimensions with perceived false self.

LIMITATIONS

The limitations include the small study sample, cross-sectional design, using self-reporting measures, and the predominance of women over men. Thus, the findings cannot be generalized and do not allow for causal and directional influences to be determined. Furthermore, humility was measured as a momentary state, and, perhaps due to its measurement, it was not directly related to dimensions of empathy and perceived false self in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

The results suggest that gratitude may play a key role in changing the perspective from which one looks at what oneself and others are like as well as what one would reveal to others. In contrast, affective empathy is positively, while cognitive empathy negatively, associated with wearing masks in social settings. Humility was connected to self-construct only via gratitude.

Footnotes

TO CITE THIS ARTICLE – Tomaszek, K. (2023). Do positive emotions prompt people to be more authentic? The mediation effect of gratitude and empathy dimensions on the relationship between humility state and perceived false self. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 11(4), 297–309.

DISCLOSURE

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Albrecht, K. (2015). The paradoxical power of humility: Why humility is under-rated and misunderstood. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brainsnacks/201501/the-paradoxical-power-humility [accessed January 20, 2022]

- Bialystok, L., & Kukar, P. (2018). Authenticity and empathy in education. Theory and Research in Education, 16, 23–39. 10.1177/1477878517746647 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bono, G., Emmons, R., & McCullough, M. E. (2004). Gratitude in practice and the practice of gratitude. In Linley P. A. & Joseph S. (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 464–481). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, D., Worthington, E. L., Hook, J., & Van Tongeren, D. R. (2012). Humility and the development and repair of social bonds: Two longitudinal studies. Self and Identity, 12, 1–20. 10.1080/15298868.2011.636509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Decety, J., & Fotopoulou, A. (2014). Why empathy has a beneficial impact on others in medicine: Unifying theories. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 8, 457. 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depow, G. J., Francis, Z., & Inzlicht, M. (2021). The experience of empathy in everyday life. Psychological Science, 32, 1198–1213. 10.1177/0956797621995202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derksen, F. A. W. M., Olde-Hartman, T. C., Lagro-Janssen, A. L. M., & Kramer, A. W. M. (2021). Clinical empathy in GP-training: Experiences and needs among Dutch GP-trainees. “Empathy as an element of personal growth”. Patient Education and Counseling, 104, 3016-3022. 10.1016/j.pec.2021.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeWall, C. N., Baumeister, R. F., Chester, D. S., & Bushman, B. J. (2016). How often does currently felt emotion predict social behavior and judgment? A meta-analytic test of two theories. Emotion Review, 8, 136–143. 10.1177/1754073915572690 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (eds.). (2004). The psychology of gratitude. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Falewicz, A., & Bąk, W. (2016). Private vs. public self-consciousness and self-discrepancies. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 4, 58–64. 10.5114/cipp.2016.55762 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 145–166). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frostenson, M. (2016). Humility in business: a contextual approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 138, 91–102. 10.1007/s10551-015-2601-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gurnani, R., & Sethia, S. (2019). Does receiving promote giving? Gratitude as a predictor of altruism via happiness. International Journal of Research and Analytical Reviews, 6, 992–981. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J. A., & Schwartz, R. (2019). Empathy present and future. Journal of Social Psychology, 159, 225–243. 10.1080/00224545.2018.1477442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harter, S., Marold, D., Whitesell, N. R., & Cobbs, G. (1996). A model of the effects of parent and peer support on adolescent false self behavior. Child Development, 67, 360–374. 10.2307/1131819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Hendijani, R., & Sohrabi, B. (2019). The effect of humility on emotional and social competencies: The mediating role of judgment. Cogent Business & Management, 6, 1–16. 10.1080/23311975.2019.1641257 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Homan, K., & Hosack, L. (2019). Gratitude and the self: Amplifying the good within. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 29, 874–886. 10.1080/10911359.2019.1630345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hua, A. Y., Wells, J. L., Brown, C. L., & Levenson, R. W. (2021). Emotional and cognitive empathy in caregivers of people with neurodegenerative disease: Relationships with caregiver mental health. Clinical Psychological Science, 9, 449–466. 10.1177/2167702620974368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussong, A. M., Langley, H. A., Thomas, T., Coffman, J., Halberstadt, A., Costanzo, P., & Rothenberg, W. A. (2019). Measuring gratitude in children. Journal of Positive Psychology, 14, 563–575. 10.1080/17439760.2018.1497692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari, F. (2020). The mediating role of self-compassion in relation between character strengths and flourishing in college students. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 6, 76–93. 10.1504/IJHD.2020.108755 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. R. (2019). Intellectual humility and empathy by analogy. Topoi, 38, 221–228. 10.1007/s11245-017-9453-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jongman-Sereno, K. P., & Leary, M. (2020). Self-judgments of authenticity. Self and Identity, 19, 32–63. 10.1080/15298868.2018.1526109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lasota, A., Tomaszek, K., & Bosacki, S. (2020). How to become more grateful? The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between empathy and gratitude. Current Psychology. 10.1007/s12144-020-01178-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lenton, A. P., Bruder, M., Slabu, L., & Sedikides, C. (2012). How does “being real” feel? The Experience of state authenticity. Journal of Personality, 81, 276–289. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2012.00805.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardaş, F., & Yalçin, I. (2021). The broaden-and-built theory of gratitude: Testing a model of well-being and resilience on Turkish college students. Participatory Educational Research, 8, 141–159. 10.17275/per.21.8.8.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierczak, M., & Karasiewicz, K. (2021). Dyadic empathy in Polish samples: Validation of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index for Couples. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 9, 354–365. 10.5114/cipp.2021.103541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossakowska, M., & Kwiatek, P. (2014). Polska adaptacja kwestionariusza do badania wdzięczności GQ-6 [The Polish adaptation of the Gratitude Questionnaire GQ-6]. Przegląd Psychologiczny, 57, 503–514. [Google Scholar]

- Kozakevich, A. E, Shamay-Tsoory, S. G., & Hertz, U. (2021). Adaptive empathy: Empathic response selection as a dynamic, feedback-based learning process. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 706474. 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.706474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, E., Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2017). State humility: Measurement, conceptual validation, and intrapersonal processes. Self and Identity, 16, 399–438. 10.1080/15298868.2016.1267662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse, E., Chancellor, J., Ruberton, P. M., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). An upward spiral between gratitude and humility. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5, 805–814. 10.1177/1948550614534700 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Layous, K., Nelson, S. K., Kurtz, J. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2017). What triggers prosocial effort? A positive feedback loop between positive activities, kindness, and well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12, 385–398. 10.1080/17439760.2016.1198924 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, D., Zhang, W., Li, X., Li, N., & Ye, B. (2012). Gratitude and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts among Chinese adolescents: Direct, mediated, and moderated effects. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 55–66. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lishner, D. A., Steinert, S. W., & Stock, E. L. (2016). Gratitude, sympathy, and empathy. In T. K. Shackelford & V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science (pp. 1–4). Springer. 10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_3053-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luan, C. C., & Chen, T. H. (2020). Empathy from private or public self-consciousness in socially responsible consumption. Journal of Philanthropy and Marketing, 26, e1695. 10.1002/nvsm.1695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mestvirishvili, M., & Mestvirishvili, N. (2021). Self-control and self-consciousness: Regulation or acceleration of self-discrepancy distress? Polish Psychological Bulletin, 52, 31–39. 10.24425/ppb.2021.136814 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. A. (2002). The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 112–127. 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough, M. E., Kilpatrick, S., Emmons, R., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Is gratitude a moral affect? Psychological Bulletin, 127, 249–266. 10.1037//0033-2909.127.2.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michałek-Kwiecień, J. (2020). Grandparental influence on young adult grandchildren: The role of grandparental empathy and quality of intergenerational relationships. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 8, 329–338. 10.5114/cipp.2020.101301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mora-Pelegrín, M., Montes-Berges, B., Aranda, M., Vázquez, M. A., & Armenteros-Martínez, E. (2021). The empathic capacity and the ability to regulate it: Construction and validation of the Empathy Management Scale (EMS). Healthcare, 9, 587. 10.3390/healthcare9050587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J. A., Freitas, L. B. L., O’Brien, M., Calkins, S. D., Leerkes, E. M., & Marcovitch, S. (2013). Preschool-aged children’s understanding of gratitude: Relations with emotion and mental state knowledge. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 31, 42–56. 10.1111/j.2044-835X.2012.02077.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, R., & Marrone, J. A. (2018). Humility: Our current understanding of the construct and its role in organizations. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20, 805–824. 10.1111/ijmr.12160 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nowakowska, I. (2022). Volunteerism in the last year as a moderator between empathy and altruistic social value orientation: an exploratory study. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 10, 10–20. 10.5114/cipp.2021.108258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, R., Baldé, A., Madeira, M., Ribeiro, T., & Arriaga, P. (2021). The impact of writing about gratitude on the intention to engage in prosocial behaviors during the COVID-19 outbreak. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 588691. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.588691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orange, D. M. (2002). There is no outside: Empathy and authenticity in psychoanalytic process. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 19, 686–700. 10.1037/0736-9735.19.4.686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Owens, B. P., Johnson, M. D., & Mitchell, T. R. (2013). Expressed humility in organizations: Implications for performance, teams, and leadership. Organization Science, 24, 1517–1538. 10.1287/orsc.1120.0795 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reniers, R. L., Corcoran, R., Drake, R., Shryane, N. M., & Völlm, B. A. (2011). The QCAE: a questionnaire of cognitive and affective empathy. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93, 84–95. 10.1080/00223891.2010.528484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, G. N., Christy, A. G., Kim, J., Vess, M., Hicks, J. A., & Schlegel, R. J. (2019). Understanding the relationship between perceived authenticity and well-being. Review of General Psychology, 23, 113–126. 10.1037/gpr0000161 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, A. R., Levine, E. E., & Sezer, O. (2021). Hiding success. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120, 1261–1286. 10.1037/pspi0000322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumble, A. C., Van Lange, P. A. M., & Parks, C. D. (2009). The benefits of empathy: When empathy may sustain cooperation in social dilemmas. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 856–866. 10.1002/ejsp.659 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schultheiss, O., & Brunstein, J. (2010). Implicit motives. Oxford Scholarship Online.

- Sheldon, K. M., & Elliot, A. J. (1998). Not all personal goals are personal: Comparing autonomous and controlled reasons as predictors of effort and attainment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 546–557. 10.1177/0146167298245010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Monte Carlo power analysis for indirect effects application. Retrieved from https://schoemanna.shinyapps.io/mc_power_med/ [accessed April 20, 2022]

- Spezio, M., Peterson, G., & Roberts, R. C. (2019). Humility as openness to others: Interactive humility in the context of l’Arche. Journal of Moral Education, 48, 27–46. 10.1080/03057240.2018.1444982 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney, J. P. (2000). Humility: Theoretical perspectives, empirical findings and directions for future research. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 70–82. 10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.70 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tudge, J. R. H., Freitas, L. B. L., & O’Brien, L. T. (2015). The virtue of gratitude: a developmental and cultural approach. Human Development, 58, 281–300. 10.1159/000444308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weir, K. F., & Jose, P. E. (2010). The Perception of False Self Scale for adolescents: Reliability, validity, and longitudinal relationships with depressive and anxious symptoms. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 28, 393–411. 10.1348/026151009x423052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, H., Whittington, R., Perry, L., & Eames, E. (2017). Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. Burnout Research, 6, 18–29. 10.1016/j.burn.2017.06.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J. C., Nadelhoffer, T., Thomson Ross, L., & Sinnott-Armstrong, W. (2018). Be it ever so humble: Proposing a dual-dimension account and measurement of humility. Self and Identity, 17, 92–125. 10.1080/15298868.2017.1327454 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W., Lin, X., Li, X., Xu, X., Guo, H., Sun, B., & Jiang, H. (2021). The influence of emotion and empathy on decisions to help others. SAGE Open, 11, 1–12. 10.1177/21582440211014513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K., Zhou, L., Wang, Z., Lin, C., & Luo, Z. (2019). The dark side of expressed humility for non-humble leaders: a conservation of resources perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1858. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]