This randomized clinical trial investigates the relative efficacy of Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement in addition to methadone treatment as usual compared with usual care only.

Key Points

Question

What is the relative efficacy of Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) as an adjunct to methadone treatment as usual (usual care) as compared with usual care only?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 154 individuals with chronic pain in methadone treatment for an opioid use disorder, relative to usual care, MORE plus usual care demonstrated efficacy for decreasing drug use, pain, and depression and increasing methadone treatment retention and adherence.

Meaning

Phase 3 clinical trials of MORE and the development of strategies to train clinicians to integrate MORE into methadone treatment programs are warranted.

Abstract

Importance

Methadone treatment (MT) fails to address the emotion dysregulation, pain, and reward processing deficits that often drive opioid use disorder (OUD). New interventions are needed to address these factors.

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of MT as usual (usual care) vs telehealth Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) plus usual care among people with an OUD and pain.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study was a randomized clinical trial conducted from August 2020 to June 2022. Participants receiving MT for OUD and experiencing chronic pain were recruited at 5 clinics in New Jersey.

Interventions

In usual care, participants received MT, including medication and counseling. Participants receiving MORE plus usual care attended 8 weekly, 2-hour telehealth groups that provided training in mindfulness, reappraisal, and savoring in addition to usual care.

Main Outcomes and Measure

Primary outcomes were return to drug use and MT dropout over 16 weeks. Secondary outcomes were days of drug use, methadone adherence, pain, depression, and anxiety. Analyses were based on an intention-to-treat approach.

Results

A total of 154 participants (mean [SD] age, 48.5 [11.8] years; 88 female [57%]) were included in the study. Participants receiving MORE plus usual care had significantly less return to drug use (hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; 95% CI, 0.37-0.90; P = .02) and MT dropout (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.18-0.96; P = .04) than those receiving usual care only after adjusting for a priori–specified covariates (eg, methadone dose and recent drug use, at baseline). A total of 44 participants (57.1%) in usual care and 39 participants (50.6%) in MORE plus usual care returned to drug use. A total of 17 participants (22.1%) in usual care and 10 participants (13.0%) in MORE plus usual care dropped out of MT. In zero-inflated models, participants receiving MORE plus usual care had significantly fewer days of any drug use (ratio of means = 0.58; 95% CI, 0.53-0.63; P < .001) than those receiving usual care only through 16 weeks. A significantly greater percentage of participants receiving MORE plus usual care maintained methadone adherence (64 of 67 [95.5%]) at the 16-week follow-up than those receiving usual care only (56 of 67 [83.6%]; χ2 = 4.49; P = .04). MORE reduced depression scores and ecological momentary assessments of pain through the 16-week follow-up to a significantly greater extent than usual care (group × time F2,272 = 3.13; P = .05 and group × time F16,13000 = 6.44; P < .001, respectively). Within the MORE plus usual care group, EMA pain ratings decreased from a mean (SD) of 5.79 (0.29) at baseline to 5.17 (0.30) at week 16; for usual care only, pain decreased from 5.19 (0.28) at baseline to 4.96 (0.29) at week 16. Within the MORE plus usual care group, mean (SD) depression scores were 22.52 (1.32) at baseline and 18.98 (1.38) at 16 weeks. In the usual care–only group, mean (SD) depression scores were 22.65 (1.25) at baseline and 20.03 (1.27) at 16 weeks. Although anxiety scores increased in the usual care–only group and decreased in the MORE group, this difference between groups did not reach significance (group × time unadjusted F2,272 = 2.10; P= .12; Cohen d = .44; adjusted F2,268 = 2.33; P = .09). Within the MORE plus usual care group, mean (SD) anxiety scores were 25.5 (1.60) at baseline and 23.45 (1.73) at 16 weeks. In the usual care–only group, mean (SD) anxiety scores were 23.27 (1.75) at baseline and 24.07 (1.73) at 16 weeks.

Conclusions and Relevance

This randomized clinical trial demonstrated that telehealth MORE was a feasible adjunct to MT with significant effects on drug use, pain, depression, treatment retention, and adherence.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04491968

Introduction

The US is experiencing an opioid crisis, with an estimated 10.1 million individuals who misuse opioids or have an opioid use disorder (OUD).1 To address this crisis, programs that provide medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) are expanding.2 MOUD is the criterion standard intervention for OUD, and methadone treatment (MT) is the oldest and the most widely used MOUD3; yet, half of people who begin MT discontinue treatment within a year,4 and, within 6 months, half of people retained in an MT program continue or return to use of opioids and other illicit drugs.5 New interventions are needed to improve MT outcomes and retention.

Physical pain, emotional distress, and reward deficiency, which affect the majority of people receiving MT,6,7 are thought to contribute to continued opioid and other drug use and MT dropout.8,9 Studies of people receiving MT indicate that 80% to 88% experienced pain in the last week,6 and pain is negatively associated with MT retention.9,10 Also, individuals with pain who receive MT report lower treatment satisfaction than those without pain and are more likely to believe their methadone dosage is too low.10,11 Moreover, people receiving MT experience abnormal corticostriatal responses to drug-related and nondrug-related reward stimuli, suggesting that natural rewards are undervalued in these individuals relative to drug-related rewards.12 However, MOUD combined with standard behavioral interventions (eg, motivational interviewing, relapse prevention) fail to systematically address the physical pain, emotional distress, and reward processing deficits that promote drug use.13,14,15,16,17,18,19

Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement (MORE) integrates training in mindfulness, reappraisal, and savoring skills into an 8-week group therapy designed to remediate hedonic dysregulation in brain reward systems underpinning OUD.20 To date, MORE is unique among existing behavioral treatments in its ability to simultaneously reduce drug-cue reactivity, improve pain-related functioning, and increase natural reward responsiveness among people who use opioids.21 Across multiple randomized clinical trials (RCTs), MORE has demonstrated efficacy for reducing opioid use/misuse, craving, emotional distress, and pain in academic and primary care settings.22,23,24,25,26 Our pilot RCT of in-person MORE was the first to demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of MORE in MT, with strong indications of efficacy.27 We, therefore, conducted a phase 2 RCT of MORE vs MT as usual (herein referred to as usual care) among people with OUD and chronic pain. We hypothesized that compared with usual care alone, those randomized to MORE plus usual care would have less return to drug use and MT dropout, greater methadone adherence, and less opioid and other drug use, pain, depression, and anxiety than those receiving usual care only. Although we originally planned to implement MORE in person, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, MORE was delivered through telehealth.

Methods

Design, Setting, and Participants

This phase 2 RCT was approved by the Rutgers institutional review board. Participants were recruited at 5 MT clinics in New Jersey from August 2020 through January 2022 and provided written informed consent. Data collection was completed in June 2022. Eligible participants were (1) prescribed methadone, (2) experiencing chronic pain (ie, pain of a ≥3 of 10 for at least 3 months), (3) not actively psychotic, at risk for suicide, or cognitively impaired, (4) not formally trained in mindfulness in the past 5 years, and (5) able to attend MORE treatment sessions. This study followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) reporting guidelines.28

Randomization and Blinding

We randomized blocks of participants with a 1:1 ratio to usual care alone or MORE plus usual care, before the start of each MORE group. Randomization was stratified by sex and any opioid use in the past 30 days (yes/no) at baseline. Outcome assessors, statisticians, and investigators were blinded to treatment allocation. Only the study coordinator who notified participants of their condition had access to the randomization lists that were generated by a computerized randomization generator.

Interventions

Participants in the MORE plus usual care group attended 8 weekly, 2-hour group sessions. The MORE intervention was implemented remotely, through video conferencing. Participants were provided with a tablet and data plan to ensure access to the internet. MORE sessions involved mindfulness to strengthen self-regulation of drug use and reduce pain, reappraisal to regulate negative emotions and reduce craving by contemplating drug use consequences, and savoring to increase positive emotions and augment natural reward processing (eTable in Supplement 2 contains specific session content).29 Participants were taught to replace the reward obtained from drug use by self-generating natural reward via mindfulness and savoring. MORE also included techniques designed to mindfully honor the recovery process and promote reflection on the reasons for taking MOUD. Each session began with a mindful breathing meditation, followed by group processing of the meditation. Next, therapists debriefed participants’ weekly homework practice of mindfulness, reappraisal, and savoring skills. These group processing efforts involved social-behavioral learning principles including positive reinforcement and shaping to maximize learning and motivation. Psychoeducational material and experiential exercises were then introduced, and participants were asked to practice 15 minutes of mindfulness/reappraisal/savoring skills daily. MORE was delivered by master’s-level clinicians, trained by E.L.G, the developer of MORE. The clinicians received weekly supervision by an experienced, doctoral-level, MORE clinician (A.W.H.). MORE sessions were recorded and reviewed for adherence with the MORE Fidelity Measure, a validated tool.30

In MT programs, patients take methadone daily and come to the clinic regularly to get their dose. However, at the time of the study, most participants received doses at home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. MT clinic individual and group therapy (neither involving mindfulness) was usually delivered through telehealth due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Assessments

Adverse events were assessed at each study visit and were reviewed by a data safety monitoring board. Participants completed interviews at baseline, 8 weeks, and 16 weeks. At each assessment, recent urine drug screen results were abstracted from clinic medical records, or participants provided a saliva sample for drug testing. Also, all participants completed ecological momentary assessments (EMAs) of pain and drug use. Participants responded during weeks 1 to 16 to 3 prompts sent at random times within blocks (1 from 9 am-3 pm, 1 from 3 pm-9 pm, and 1 end-of-day prompt from 9-10 pm) on their own cell phones or tablets provided by the study. Participants had a 2-hour window to respond to an EMA survey before it was unavailable. Surveys were separated by a minimum of 1 hour. While the first and second EMA surveys asked participants to rate pain intensity “right now,” the end-of-day EMA did not ask for a pain rating but instead asked about drug use in the previous 24 hours. Participants were compensated with gift cards for completing study interviews and EMA assessments.

Measures

Primary Outcomes: Return to Drug Use and MT Retention

Return to use was assessed by noting the number of days until first illicit drug use through EMA or positive drug screen. MT retention through 16 weeks was assessed by clinic report of continued enrollment in the MT program.

Secondary Outcomes: Days of Drug Use, Methadone Adherence, Pain, Depression, and Anxiety

Number of days of illicit drug use in the past 30 days (ie, opioids, cocaine/crack, marijuana, amphetamines, hallucinogens, inhalants, tranquilizers, stimulants, or misuse of prescription drugs) were assessed with questions from the Addiction Severity Index (ASI).31 Daily, through EMA, participants were asked to specify which nonprescribed drugs they used in the past 24 hours. Urine or saliva drug screens were used to confirm self-report of drug use at baseline, 8 weeks, and 16 weeks. Variables for number of days of opioid use, other drug use, and any drug use over 16 weeks were computed by counting the greatest number of days of drug use recorded through EMA, the ASI, or drug screen. At least 1 day of drug use was noted for participants who did not self-report drug use but had a positive drug screen. Participants were considered nonadherent to MT if they had a drug screen negative for methadone at baseline, 8 weeks, or 16 weeks. We planned to use medical record review to assess adherence to methadone dosing but had to rely on drug screens because participants were dosing at home due to the COVID-19 pandemic and limitations to clinic operations.

Participants were asked “How intense is your pain right now?” on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (very intense pain) during 2 daily prompts over 16 weeks through EMA.32 At baseline, 8 weeks, and 16 weeks, present moment pain was measured with the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as you can imagine).33 Depression and anxiety were assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), respectively, at baseline, 8 weeks, and 16 weeks.34,35 Scores over 16 on the CES-D or BAI indicate clinically significant depression or moderate to severe anxiety.34,35

Counseling Hours

Based on clinic medical record notes and attendance records, the total number of individual and group counseling hours (other than MORE groups), completed by each participant at their clinic over the study intervention period, was assessed.

Statistical Analysis

We powered this study based on a previous study evaluating a mindfulness intervention among people with substance use disorder that showed that the hazard ratio (HR) of return to drug use for the intervention compared with usual care of 0.46.36 Because MORE would be delivered by telehealth, we assumed a slightly more conservative HR of return to use comparing MORE plus usual care to usual care only of 0.53. Our study needed 56 participants per treatment group to test an HR of 0.53 when comparing MORE plus usual care to usual care, with 84.9% power and α = .05 (2-sided). We accounted for 30% attrition when recruiting participants.

Analyses were based on an intention-to-treat approach. Return to drug use and MT dropout was assessed using survival analysis, including Kaplan-Meier curves, log-rank test, and proportional hazards regression models. Days of drug use were analyzed using zero-inflated Poisson models to account for excessive zeros.37 Methadone adherence was compared between MORE plus usual care and usual care alone using χ2 and logistic regression analysis. Pain, depression, and anxiety were assessed using mixed-model analysis (EMA model specifications are detailed in the eAppendix in Supplement 2). Missing data were handled with maximum likelihood estimation, assuming missing at random.38 Due to the pragmatic nature of the trial, we assumed substantial heterogeneity among study treatment groups, and thus our preregistered primary analyses adjusted for a set of covariates that were selected and predeclared a priori due to their potential association with study outcomes: standard clinic counseling time during the 16 weeks and, at baseline, recent illicit drug use, methadone dose, and time receiving MT. We planned to include other baseline characteristics as covariates if the between-groups P < .10, but no other variables met this threshold. Statistical significance was defined as by a 2-sided P < .05. Analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Participant Characteristics

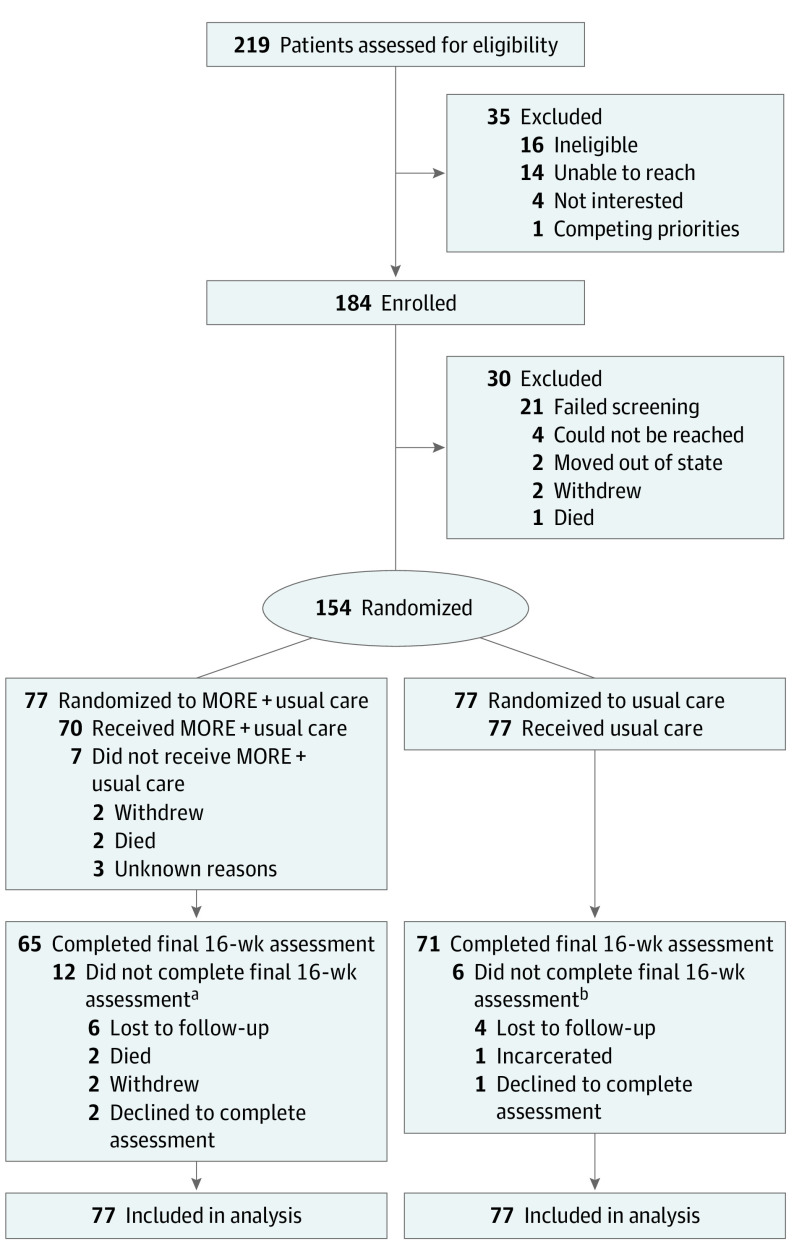

A total of 154 participants (mean [SD] age, 48.5 [11.8] years; 88 female [57%]; 66 male [43%]) were included in the study. Participants identified with the following race and ethnicity categories: 62 Black (40%), 20 Hispanic (13%), and 80 White (52%), and some identified as more than 1 race and ethnicity. A total of 36 participants (23%) did not have a high school diploma, and most were unemployed (136 [86%]). At baseline, in the past 30 days, 65 of 154 participants (42%) used heroin, 38 (25%) used cocaine, and 50 (33%) used marijuana. Participants used drugs a mean (SD) of 15 (19) days in the last 30 days and had received methadone treatment for a mean (SD) of 3.6 (4.6) years. At baseline, 145 participants (95%) had a drug screen positive for methadone. The most common pain conditions reported were back pain (35 [23%]) and arthritis (31 [20%]). At baseline, on average, participants were experiencing moderate pain (mean [SD] score on BPI, 5.2 [2.6]) and clinically significant symptoms of depression (mean [SD] score on the CES-D Scale, 22.6 [11.2]) and anxiety (mean [SD] score on the BAI, 24.4 [14.7]). At baseline, significantly more patients in the MORE plus usual care group (62 [81%]) than in the usual care–only group (50 [63%]) used opioids or other drugs (P = .02). However, there were no significant between-groups differences in other clinical or demographic characteristics (Table and Figure 1).25,26

Table. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics, Overall and by Treatment Groupa.

| Measure | Entire sample (N = 154) | MORE + usual care (n = 77) | Usual care (n = 77) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, No. (%) | |||

| Female | 88 (57) | 44 (57) | 44 (57) |

| Male | 66 (43) | 33 (43) | 33 (43) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 48.5 (11.8) | 49.2 (10.9) | 47.7 (11.3) |

| Race and ethnicity, No. (%)b | |||

| Black/African American | 62 (40) | 29 (38) | 33 (43) |

| Hispanic | 20 (13) | 11 (14) | 9 (12) |

| White | 80 (52) | 38 (49) | 42 (55) |

| Education, completed less than high school, No. (%) | 36 (23) | 19 (25) | 17 (22) |

| Unemployed, No. (%) | 132 (86) | 66 (86) | 66 (86) |

| Primary pain condition, No. (%)b | |||

| Back pain | 35 (23) | 21 (27) | 14 (18) |

| Spinal conditions | 34 (22) | 21 (27) | 13 (17) |

| Arthritis | 31 (20) | 13 (17) | 18 (23) |

| Osteoarthritis | 24 (16) | 16 (21) | 8 (10) |

| Other conditions (eg, migraine, knee pain) | 95 (62) | 48 (62) | 47 (61) |

| Taking over-the-counter or prescribed pain medication | 100 (65) | 53 (69) | 47 (61) |

| Used opioids in the past 30 d, No. (%)c | 81 (53) | 44 (57) | 40 (52) |

| Used any drugs in the past 30 d, No. (%)d | 112 (72) | 62 (81)e | 50 (63)e |

| Methadone dose, mean (SD), mg | 95.3 (40.0) | 93.8 (39.2) | 96.9 (41.2) |

| Drug screen positive for methadone, No. (%) | 145 (95) | 74 (96) | 71 (93) |

| Time taking methadone, mean (SD), y | 3.6 (4.6) | 4.2 (4.7) | 3.1 (4.3) |

| Anxiety, mean (SD)f | 24.4 (14.7) | 25.5 (14.1) | 23.3 (15.4) |

| Depression, mean (SD)g | 22.6 (11.2) | 22.5 (11.6) | 22.6 (11.0) |

| Pain, mean (SD)h | 5.2 (2.6) | 5.1 (2.7) | 5.2 (2.5) |

Abbreviation: MORE, Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement.

No statistically significant differences existed between-groups on any baseline variables, except baseline use of any drugs, χ2 = 6.52.

Participants could report more than one category.

Heroin, morphine, fentanyl, prescription pain medicine (not as prescribed).

Heroin, morphine, fentanyl, prescription pain medicine (not as prescribed), cocaine/crack, marijuana, amphetamines, hallucinogens, inhalants, or misuse of other prescription drugs (eg, benzodiazepines).

P = .02.

Measured with the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Higher scores indicate greater symptoms of anxiety. A score over 16 indicates moderate to severe anxiety.26

Measured with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale. Higher scores indicate greater symptoms of depression. A score over 16 indicates clinically significant depression.25

Pain in the present moment as measured with the Brief Pain Inventory on a scale from 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as you can imagine).

Figure 1. Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Diagram.

MORE indicates Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement.

aOf the 12 participants who did not complete the final 16-week survey, 6 did not do the 8-week survey.

bOf the 6 participants who did not complete the final 16-week survey, 2 did not do the 8-week survey.

Treatment Participation

A total of 56 of 77 participants (73%) randomized to the MORE plus usual care group had at least a minimum treatment dose (ie, attended at least 4 of the 8 sessions).26,39 Participants in the MORE plus usual care group completed a mean (SD) of 5.3 (2.8) MORE sessions. No significant differences in baseline characteristics existed between those who completed treatment and those who did not. Seven participants in the MORE plus usual care group did not participate in MORE sessions (2 withdrew from study, 2 died due to nonstudy-related causes, 3 for unknown reasons). Participants in the MORE plus usual care group had a mean (SD) of 8.6 (11.5) hours and the usual care–only group had a mean (SD) of 8.0 (10.7) hours of group or individual clinic counseling (not including the MORE groups) during the 8-week intervention period. There were no statistically significant differences between the MORE plus usual care group and usual care–only group regarding number of hours of clinic counseling time over the 16-weeks (not including MORE).

Adverse Events

Twenty-nine adverse events (eg, COVID-19 infection, asthma, cellulitis) were reported among 19 participants (8 receiving usual care only and 11 receiving MORE plus usual care); none were determined to be related to study participation.

Primary Outcomes: Return to Drug Use and MT Retention

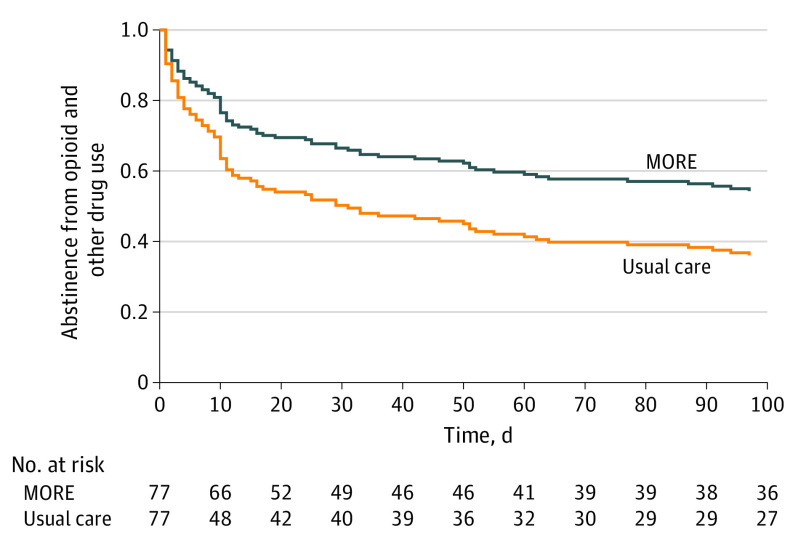

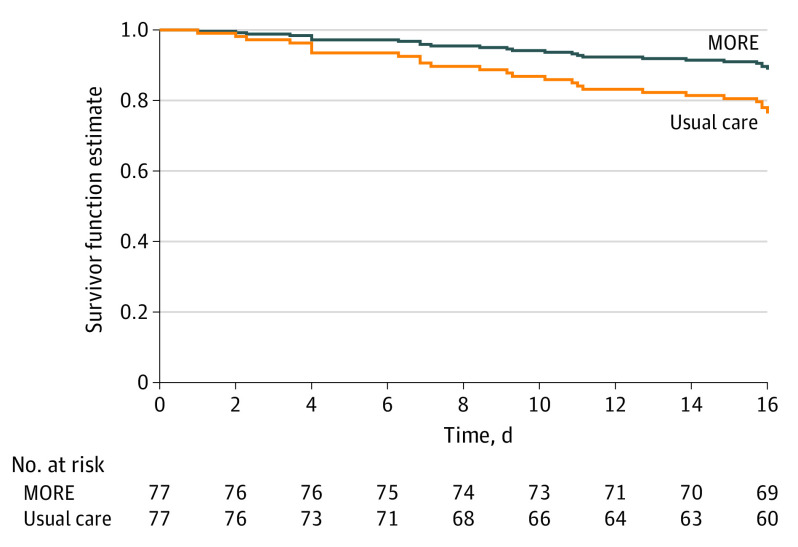

Participants receiving MORE plus usual care had significantly less return to opioid or other drug use than those receiving usual care only (HR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.37-0.90; P = .02) (Figure 2) after adjusting for a priori specified covariates (ie, standard clinic counseling time during the 16 weeks and, at baseline, any drug use in the past 30 days, methadone dose, and time in MT). A total of 44 participants (57.1%) in usual care and 39 participants (50.6%) in MORE plus usual care returned to drug use. Participants receiving MORE plus usual care had significantly less MT dropout during the study period than those receiving usual care only (HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.18-0.96; P = .04) (Figure 3) after adjusting for the a priori–specified covariates noted previously. A total of 17 participants (22.1%) in the usual care group and 10 participants (13.0%) in MORE plus usual care dropped out of MT. In unadjusted analyses, the differences in return to use (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.88-2.10; P = .16) and dropout (HR, 0.55; 95% CI, 0.25-1.19; P = .13) did not reach statistical significance.

Figure 2. Survival Curve Depicting Differences in Return to Opioid and Other Drug Usea,b Among Patients Randomized to Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement Plus Usual Care vs Usual Care Alonec.

aHeroin, morphine, fentanyl, prescription pain medicine (not as prescribed), cocaine/crack, marijuana, amphetamines, hallucinogens, inhalants, or misuse of other prescription drugs (eg, benzodiazepines).

bReturn to use: usual care, 44 (57.1%), MORE plus usual care, 39 (50.6%).

cAdjusted P = .01, a priori, for clinic counseling hours (other than MORE) during treatment period, methadone dose, opioid use at baseline, and time in methadone treatment, at baseline.

Figure 3. Survival Curve Depicting Differences in Methadone Treatment Dropouta Among Patients Randomized to Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement Plus Usual Care vs Usual Care Aloneb.

aDropout: usual care, 17 (22.1%), MORE plus usual care, 10 (13.0%).

bAdjusted P = .04, a priori, for clinic counseling hours (other than MORE) during treatment period, methadone dose, opioid use at baseline, and time in methadone treatment, at baseline.

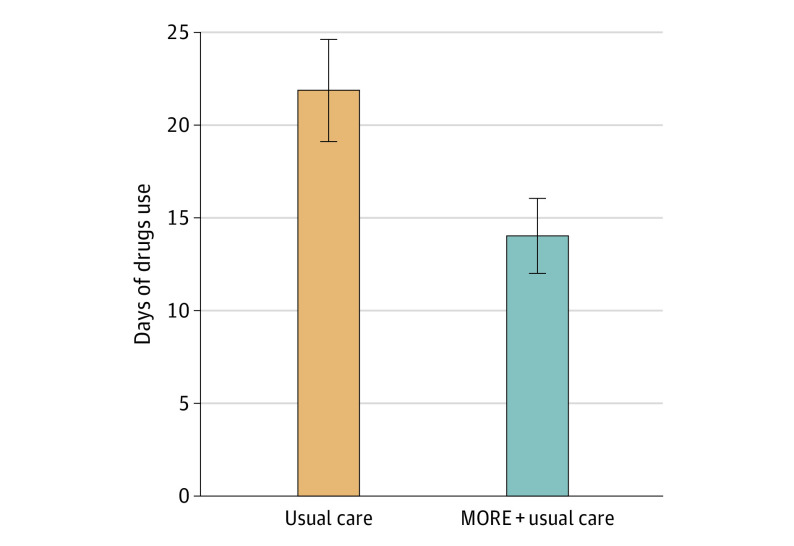

Days of Drug Use

Participants receiving MORE plus usual care had significantly fewer days of any drug use (ratio of means = 0.58; 95% CI, 0.53-0.63; P < .001), including opioid use (ratio of means = 0.72; 95% CI, 0.63-0.81; P < .001) and other illicit drug use (ratio of means = 0.53; 95% CI, 0.48-0.58; P < .001), than those receiving usual care only through 16 weeks in covariate-adjusted models (Figure 4). For participants receiving usual care, the mean (SD) over the 16 weeks was 21.7 (23.8) days for any drug use, 8.5 (14.8) days for opioid use, and 18.3 (23.0) days for other drug use. For participants receiving MORE plus usual care, the mean (SD) over the 16 weeks was 13.9 (16.9) days for any drug use, 7.9 (13.2) days for opioid use, and 9.8 (14.8) days for other drug use. In unadjusted analyses, participants receiving MORE plus usual care also had significantly fewer days of drug use than those receiving usual care only (ratio of means = 0.62; 95% CI, 0.57-0.67; P < .001).

Figure 4. Differences in Mean Days of Opioid and Other Drug Usea Through the 16-Week Follow-Up Among Patients Randomized to Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement Plus Usual Care vs Usual Care Aloneb.

aFor example, any drug use: heroin, morphine, fentanyl, prescription pain medicine (not as prescribed), cocaine/crack, marijuana, amphetamines, hallucinogens, inhalants, or misuse of other prescription drugs (eg, benzodiazepines).

bP <.001.

MT Adherence

Although methadone adherence did not differ between the MORE plus usual care and usual care–only groups at baseline or 8 weeks (χ2 = 0.31; P = .58), a significantly greater percentage of patients receiving MORE plus usual care maintained methadone adherence (64 of 67 [95.5%]) at 16 weeks than those receiving usual care only (56 of 67 [83.6%]; χ2 = 4.49; P = .03). In a covariate-adjusted logistic regression analysis, the effect of MORE plus usual care vs usual care only on methadone adherence at 16 weeks remained statistically significant (odds ratio, 4.56; 95% CI, 1.04-20.05; P = .04).

Pain

The EMA response rate was 61% (34 of 56 days) at 8 weeks and 53% (59 of 112 days) at 16 weeks. Participants receiving MORE plus usual care responded on a mean (SD) of 50.5 (35.6) days, and those receiving usual care only responded on mean (SD) of 68.8 (36.7) days. MORE plus usual care reduced EMA pain ratings through 16 weeks to a significantly greater extent than usual care only (group × time unadjusted F16,13000 = 6.44; P < .001; adjusted F16,13000 = 6.39; P < .001; Cohen d = 0.36). Within the MORE plus usual care group, EMA pain ratings decreased from a mean (SD) of 5.79 (0.29) at baseline to 5.17 (0.30) at week 16. In the usual care–only group, pain decreased from a mean (SD) of 5.19 (0.28) at baseline to 4.96 (0.29) at week 16. No significant between-groups differences were observed on the BPI from baseline through 16 weeks (group × time F2,272 = 0.31; P = .73).

Depression and Anxiety

MORE plus usual care reduced depression scores through the 16-week follow-up to a greater extent than usual care only (group × time unadjusted F2,272 = 3.13; P = .04; adjusted F2,268 = 2.80; P = .06; Cohen d = 0.18). Within the MORE plus usual care group, mean (SD) depression scores were 22.52 (1.32) at baseline and 18.98 (1.38) at 16 weeks. In the TAU group, mean (SD) depression scores were 22.65 (1.25) at baseline and 20.03 (1.27) at 16 weeks. Although anxiety scores increased in those receiving usual care only and decreased in the MORE group, this difference between groups did not reach significance (group × time unadjusted F2,272 = 2.10; P = .12; Cohen d = 0.44; adjusted F2,268 = 2.33; P = .09). Within the MORE plus usual care group, mean (SD) anxiety scores were 25.5 (1.60) at baseline and 23.45 (1.73) at 16 weeks. In the usual care–only group, mean (SD) anxiety scores were 23.27 (1.75) at baseline and 24.07 (1.73) at 16 weeks.

Discussion

This study was the first, to the authors’ knowledge, full-scale RCT of MORE as an adjunct to MOUD for people with OUD and chronic pain, and the first full-scale trial to evaluate MORE as implemented through telehealth. The trial demonstrated that, not only is MORE plus usual care feasible and acceptable when implemented remotely, it led to significant therapeutic effects on drug use, MT retention, methadone adherence, pain, and depression among a racially diverse, low-income sample with OUD and chronic pain. These findings are consistent with our pilot study of in-person MORE in MT27 and suggest that integration of MORE into MT settings could improve addiction treatment outcomes and quality of life among people receiving MOUD.

MORE plus usual care was associated with less return to drug use and fewer days of use than usual care only. These results may stem from the targeting of reward-related processes in MORE that MOUD treatment programs do not typically address. Although MOUD has proved to be the most effective available treatment for reducing relapse in OUD,3 MOUD does not address the underlying deficits in positive affectivity and natural reward processing that are theorized to underlie addictive behavior.12 MORE aims to target these deficits through a unique integration of mindfulness, reappraisal, and savoring techniques designed to restructure reward processing from valuation of drug reward back to valuation of natural rewards. Autonomic and neurophysiological studies demonstrate that MORE enhances cognitive control and reduces opioid cue-reactivity while strengthening responsivity to natural reward cues.40,41,42 The current trial indicates that MORE, which targets these mechanisms, translates to improved treatment outcomes beyond those provided in MT with standard counseling. Assessment of reward processing was beyond the scope of this trial; therefore, future mechanistic studies are required to determine whether MORE’s effects on OUD outcomes are mediated by changes in reward processing.

Participants receiving MORE plus usual care were less likely to drop out of MT and more likely to have a drug screen positive for methadone at 16 weeks as compared to those receiving usual care only. This was the first study, to the authors’ knowledge, to evaluate the relationship between mindfulness and MOUD retention and adherence, and only a few studies, with mixed results, have investigated the relationship between mindfulness and adherence to medications for other chronic conditions, including HIV, psychiatric illness, and heart disease.43 The impact of MORE on MT retention and adherence could be due to the specific instruction in MORE to practice mindfulness in the moments before taking methadone to imbue the act with respect and commitment. This focus on methadone dosing was particularly relevant to participants in this study, given the COVID-19 pandemic, the need for self-administration, and the loss of typical rituals around methadone dosing at the clinic.

Participants receiving MORE plus usual care also evidenced greater reductions in EMA pain ratings and depression, as compared with those receiving usual care only. Although no statistically significant effects were observed on the BPI, the average percentage reduction in EMA pain ratings (11%) following MORE plus usual care met the threshold for minimally clinically significant change according to the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT).44 EMA allowed for temporally dynamic measurement of the impact of mindfulness practice on fluctuations in pain level in everyday life and, thus, is likely a more accurate reflection of the MORE’s analgesic effects in MT. The observed reduction in pain and depression might impact drug use because people who use substances often report that they do so to cope with pain or distress.45,46 Negative reinforcement models suggest that individuals use substances to escape physical or emotional discomfort.47,48,49,50,51 Pain and negative affect are associated with initiation and maintenance of drug use due to perceived benefits of drug use.51 Also, given negative relationships between pain and MT retention, the analgesic effects of MORE might have improved treatment retention.9,10 Future research could elucidate linkages between pain, depression, treatment retention, and drug use among people in MT.

Limitations

This study had some limitations. First, the study was administered during a pandemic, and findings may be different under normal circumstances. Second, the MORE plus usual care group experienced more counseling contact hours than the usual care–only group (when time participating in the MORE group is included), which could have affected results. However, other trials have shown MORE to significantly outperform time-matched, active controls.22,23,24,25,26 Third, methadone adherence was measured at only 3 time points through 16 weeks. We were unable to collect clinic dosing records, as planned, given limited clinic operations and self-administration of methadone at home during the pandemic. Fourth, MORE was implemented by research clinicians. The effectiveness of MORE delivered by MT clinic clinicians in typical circumstances is still unknown. Fifth, this study was not powered to evaluate moderators and mediators. Future research is needed to examine treatment mechanisms and determine moderators of treatment effects. Sixth, given the clinical complexity and socioeconomic instability of the study sample, our EMA compliance rate was suboptimal.52 Efforts to integrate EMA into treatment might improve compliance. Finally, participants were followed up for only 16 weeks. Given known high rates of return to use and MT dropout through 12 months,5 longer follow-up is required to determine the durability of the efficacy of MORE in MT.

Conclusions

In this RCT, MORE plus usual care demonstrated efficacy for addressing drug use, pain, and depression and improving MT retention and adherence in a racially diverse, low-income sample. Based on the findings from this study and prior trials of MORE, large-scale, phase 3 clinical trials that compare MORE with other interventions are warranted. Further, the development of implementation strategies to train clinicians and to integrate MORE into treatment programs is needed to disseminate this potentially impactful intervention to those with OUD and chronic pain.

Trial Protocol.

eTable. More Session Content

eAppendix. Supplemental Details on EMA Pain Rating Model

Data Sharing Statement.

References

- 1.American Society of Addiction Medicine . Opioid addiction 2016 facts & figures. 2017. Accessed July 9, 2023. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/advocacy/opioid-addiction-disease-facts-figures.pdf

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) . Biden administration announces $1.5 billion funding opportunity for state opioid response grant program. 2022. Accessed July 9, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/newsroom/press-announcements/20220519/biden-administration-announces-1-point-5-billion-funding-state-opioid-response

- 3.Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063-2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bao YP, Liu ZM, Epstein DH, Du C, Shi J, Lu L. A meta-analysis of retention in methadone maintenance by dose and dosing strategy. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35(1):28-33. doi: 10.1080/00952990802342899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naji L, Dennis BB, Bawor M, et al. A prospective study to investigate predictors of relapse among patients with opioid use disorder treated with methadone. Subst Abuse. 2016;10:9-18. doi: 10.4137/SART.S37030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eyler EC. Chronic and acute pain and pain management for patients in methadone maintenance treatment. Am J Addict. 2013;22(1):75-83. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.00308.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooperman NA, Lu SE, Richter KP, Bernstein SL, Williams JM. Influence of psychiatric and personality disorders on smoking cessation among individuals in opiate dependence treatment. J Dual Diagn. 2016;12(2):118-128. doi: 10.1080/15504263.2016.1172896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brewer DD, Catalano RF, Haggerty K, Gainey RR, Fleming CB. A meta-analysis of predictors of continued drug use during and after treatment for opiate addiction. Addiction. 1998;93(1):73-92. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.931738.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mancino M, Curran G, Han X, Allee E, Humphreys K, Booth BM. Predictors of attrition from a national sample of methadone maintenance patients. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36(3):155-160. doi: 10.3109/00952991003736389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ilgen MA, Trafton JA, Humphreys K. Response to methadone maintenance treatment of opiate dependent patients with and without significant pain. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82(3):187-193. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jamison RN, Kauffman J, Katz NP. Characteristics of methadone maintenance patients with chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(1):53-62. doi: 10.1016/S0885-3924(99)00144-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gradin VB, Baldacchino A, Balfour D, Matthews K, Steele JD. Abnormal brain activity during a reward and loss task in opiate-dependent patients receiving methadone maintenance therapy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(4):885-894. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verdejo-García A, Bechara A. A somatic marker theory of addiction. Neuropharmacology. 2009;56(Suppl 1)(suppl 1):48-62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.07.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(1):217-238. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elman I, Borsook D. Common brain mechanisms of chronic pain and addiction. Neuron. 2016;89(1):11-36. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg KM, Arnsten JH, Sacajiu G, Karasz A. Providers’ experiences treating chronic pain among opioid-dependent drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):482-488. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0908-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barry DT, Bernard MJ, Beitel M, Moore BA, Kerns RD, Schottenfeld RS. Counselors’ experiences treating methadone-maintained patients with chronic pain: a needs assessment study. J Addict Med. 2008;2(2):108-111. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31815ec240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barry DT, Cutter CJ, Beitel M, Kerns RD, Liong C, Schottenfeld RS. Psychiatric disorders among patients seeking treatment for co-occurring chronic pain and opioid use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(10):1413-1419. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beitel M, Oberleitner L, Kahn M, et al. Drug Counselor Responses to patients’ pain reports: a qualitative investigation of barriers and facilitators to treating patients with chronic pain in methadone maintenance treatment. Pain Med. 2017;18(11):2152-2161. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garland EL. Restructuring reward processing with mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement: novel therapeutic mechanisms to remediate hedonic dysregulation in addiction, stress, and pain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2016;1373(1):25-37. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garland EL, Atchley RM, Hanley AW, Zubieta JK, Froeliger B. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement remediates hedonic dysregulation in opioid users: neural and affective evidence of target engagement. Sci Adv. 2019;5(10):eaax1569. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax1569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garland EL, Manusov EG, Froeliger B, Kelly A, Williams JM, Howard MO. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: results from an early-stage randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(3):448-459. doi: 10.1037/a0035798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garland EL, Hudak J, Hanley AW, Nakamura Y. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement reduces opioid dose in primary care by strengthening autonomic regulation during meditation. Am Psychol. 2020;75(6):840-852. doi: 10.1037/amp0000638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garland EL, Hanley AW, Riquino MR, et al. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement reduces opioid misuse risk via analgesic and positive psychological mechanisms: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(10):927-940. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garland EL, Manusov EG, Froeliger B, Kelly A, Williams JM, Howard MO. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement for chronic pain and prescription opioid misuse: results from an early-stage randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2014;82(3):448-459. doi: 10.1037/a0035798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Garland EL, Hanley AW, Nakamura Y, et al. Mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement vs supportive group therapy for co-occurring opioid misuse and chronic pain in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(4):407-417. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.0033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooperman NA, Hanley AW, Kline A, Garland EL. Pilot randomized clinical trial of mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement as an adjunct to methadone treatment for people with opioid use disorder and chronic pain: impact on illicit drug use, health, and well-being. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;127:108468. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz K, Altman D, Moher D, CONSORT Group . CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garland EL. Mindfulness-Oriented Recovery Enhancement for Addiction, Stress, and Pain. NASW Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanley AW, Garland EL. The mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement fidelity measure (MORE-FM): development and validation of a new tool to assess therapist adherence and competence. J Evid Based Soc Work (2019). 2021;18(3):308-322. doi: 10.1080/26408066.2020.1833803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199-213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farrar JT, Young JP Jr, LaMoreaux L, Werth JL, Poole MR. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149-158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleeland C. Brief Pain Inventory–Short Form. BPI–SF; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988;56(6):893-897. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bowen S, Witkiewitz K, Clifasefi SL, et al. Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):547-556. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lambert D. Zero-inflated Poisson regression, with an application to defects in manufacturing. Technometrics. 1992;34(1):1-14. doi: 10.2307/1269547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubin DB. Inference and missing data. Biometrika. 1976;63(3):581-592. doi: 10.1093/biomet/63.3.581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuyken W, Hayes R, Barrett B, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (PREVENT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(9988):63-73. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62222-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garland EL, Froeliger B, Howard MO. Effects of mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement on reward responsiveness and opioid cue-reactivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2014;231(16):3229-3238. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3504-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garland EL, Froeliger B, Howard MO. Neurophysiological evidence for remediation of reward processing deficits in chronic pain and opioid misuse following treatment with mindfulness-oriented recovery enhancement: exploratory ERP findings from a pilot RCT. J Behav Med. 2015;38(2):327-336. doi: 10.1007/s10865-014-9607-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Garland EL, Hanley AW, Hudak J, Nakamura Y, Froeliger B. Mindfulness-induced endogenous theta stimulation occasions self-transcendence and inhibits addictive behavior. Sci Adv. 2022;8(41):eabo4455. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abo4455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nardi WR, Loucks EB, Springs S, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for medication adherence: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. J Psychosom Res. 2021;149:110585. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105-121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cooperman NA, Richter KP, Bernstein SL, Steinberg ML, Williams JM. Determining smoking cessation related information, motivation, and behavioral skills among opiate dependent smokers in methadone treatment. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(5):566-581. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.991405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cicero TJ, Ellis MS. The prescription opioid epidemic: a review of qualitative studies on the progression from initial use to abuse. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19(3):259-269. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2017.19.3/tcicero [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wills TA, Shiffman S. Coping and substance use: a conceptual framework. In: Shiffman S, Wills TA, eds. Coping and Substance Use. Academic Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: a reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231-244. doi: 10.3109/10673229709030550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: an affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychol Rev. 2004;111(1):33-51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carmody TP, Vieten C, Astin JA. Negative affect, emotional acceptance, and smoking cessation. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39(4):499-508. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leventhal AM, Zvolensky MJ. Anxiety, depression, and cigarette smoking: a transdiagnostic vulnerability framework to understanding emotion-smoking comorbidity. Psychol Bull. 2015;141(1):176-212. doi: 10.1037/bul0000003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Alexander K, Sanjuan P, Terplan M. The use of ecological momentary assessment methods with people receiving medication for opioid use disorder: a systematic review. Curr Addict Rep. 2023;10:366-377. doi: 10.1007/s40429-023-00492-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol.

eTable. More Session Content

eAppendix. Supplemental Details on EMA Pain Rating Model

Data Sharing Statement.