Abstract

Previously, we demonstrated that the methyl-accepting protein HtrII is the transducer for photoreceptor sensory rhodopsin II. Here, we provide experimental evidence that HtrII is also a chemotransducer. Using an agarose-in-plug bridge method, we show that an HtrII overexpression strain has a quicker response to serine than does an HtrII deletion strain. Furthermore, an in vivo flow assay demonstrates that the deletion strain is unable to modulate methylesterase activity after serine addition or photostimulation, while the overexpression strain shows distinct methanol peaks following both types of stimuli.

The archaeon Halobacterium salinarum exhibits phototactic responses to changes in light intensity and color, aerotactic responses to depletion and abundance of oxygen, and chemotactic behavior due to addition or removal of specific chemical reagents (3, 5, 9). In the absence of stimuli, halobacterial cells swim in straight lines characterized by three possible activities: swimming with one pole forward, pausing, and swimming with the other pole forward (reversal). We have shown that, unlike in eubacteria, clockwise rotation of the right-handed helical flagellar bundle in halobacteria exerts a pushing force on the cell body and counterclockwise rotation pulls the cell (1). The flagellar bundle never flies apart as it does in most enteric bacteria (6). Sensory input changes the frequency of reversals to optimize movements towards attractants and away from repellents. Thus, the cells make net progress in spatial gradients of these attractants and repellents. Specific chemoreceptors have not been identified, but the large array of tactically active compounds suggests that there should be several different receptors. Glucose, histidine, and leucine are among the effective attractants, while phenol is a repellent (7).

During our effort to comprehensivly clone the transducer gene family in H. salinarum, we identified the long-sought sensory rhodopsin II (SRII) gene, sopII, and its transducer, htrII (11, 12). Transformation of the phototaxis-deficient strains Pho81 and Δ35 with the plasmid containing the htrII-sopII locus fully restored the repellent response to blue light (8). Unlike HtrI, the transducer associated with sensory rhodopsin I (SRI), secondary structure analysis of HtrII predicted the existence of a large periplasmic domain in the N-terminal portion of the protein. This domain is 100 amino acids larger than the periplasmic domains of most eubacterial chemotransducers (6a). We postulated that HtrII, in comparison to SRI phototransducer HtrI, is not only a phototransducer for SRII but, due to the presence of the large periplasmic domain, also functions as a chemotaxis transducer. Here, we present experimental evidence showing that HtrII is a chemotransducer as well as a phototransducer in H. salinarum.

Isolation of HtrII deletion and overexpression strains.

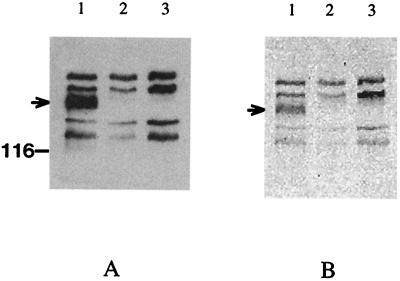

The phototaxis-defective mutant Pho81 contains a 552-bp IS2 insertion element in the region upstream from the htrII-sopII cluster (13). In order to eliminate the potential instability of the Pho81 mutant due to the presence of the mobile genomic element, a gene knockout technique was used to delete most of the downstream portion of the htrII (nucleotides 98 to 2298) coding sequence and the adjacent upstream portion of the sopII (nucleotides 1 to 231) coding sequence. Southern hybridization analysis with a 27-mer oligonucleotide probe (highly conserved among all transducer genes) indicated that the 6.5-kbp PstI fragment is missing in the ΔhtrII deletion strain (data not shown). The HtrII overexpression strain (htrII++/ΔhtrII) was constructed with a multicopy shuttle vector containing the htrII-sopII operon in strain ΔhtrII. Coupled immunoblot and methylation experiments clearly demonstrated the presence of an HtrII band in the overexpression strain (htrII++/ΔhtrII) and its absence in the deletion (ΔhtrII) and defective (Pho81) strains (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Immunoblot and fluorography analysis of the [3H]methyl-labeled transducers of htrII++/ΔhtrII (lanes 1), ΔhtrII (lanes 2), and Pho81 (lanes 3). (A) Western blot analysis with HC23 antibody. (B) Electrophoretic analysis.

HtrII is involved in the chemotactic response to serine.

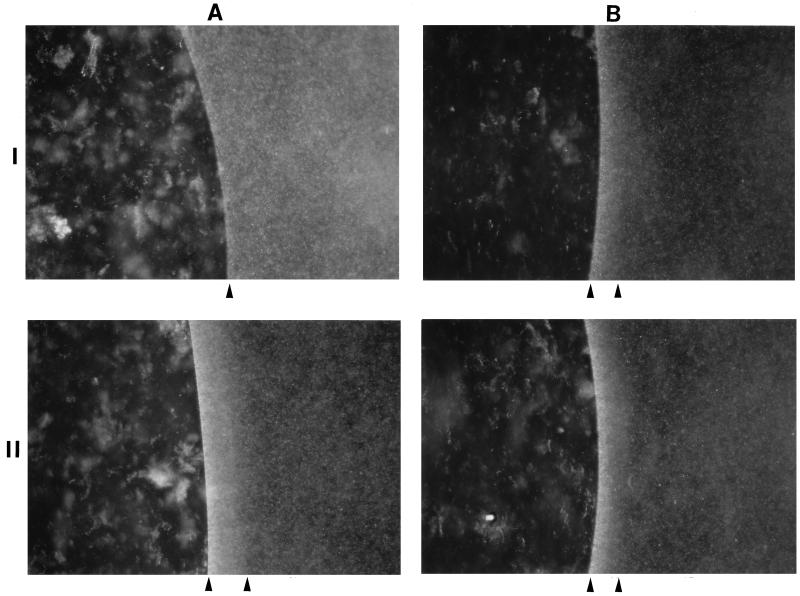

To test the hypothesis that the large periplasmic domain of HtrII has a ligand-binding function, we studied chemotactic responses in strains expressing different levels of the HtrII protein. We analyzed chemotactic responses of the deletion and overexpression strains to amino acids with our recently developed agarose-in-plug bridge method (10). In this method, agar plugs containing specific amino acids are placed under coverslips which are then filled with a motile halobacterial cell suspension. The deletion and overexpression strains were screened for responses to all essential amino acids. Among the amino acids, serine and alanine showed different kinetics in chemotactic ring formation around the agarose plug. Unlike those of the overexpression strain, ΔhtrII cells did not form a dense chemotactic ring within 5 to 10 min (Fig. 2A, panel I). During this period, overexpression strain cells did form a distinct visible chemotactic ring in response to serine, i.e., a white ring against a dark background (Fig. 2A, panel II). The difference in chemotactic response to alanine between these two strains was not as distinct as that to serine (data not shown). Both strains formed comparable chemotactic rings within 5 to 10 min with a growth medium agarose plug (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Chemotactic response (white ring indicated by two arrowheads) of an H. salinarum htrII deletion mutant (ΔhtrII) (I) and an htrII overexpression mutant (htrII++/ΔhtrII) (II) by the agarose-in-plug bridge method. (A) Serine. (B) Growth medium. Micrographs were taken by a Nikon automatic camera during dark-field microscopy with a 10× objective.

The ΔhtrII deletion mutant is defective in methylesterase responses to serine and 450-nm light (λmax = 487 [for SRII]).

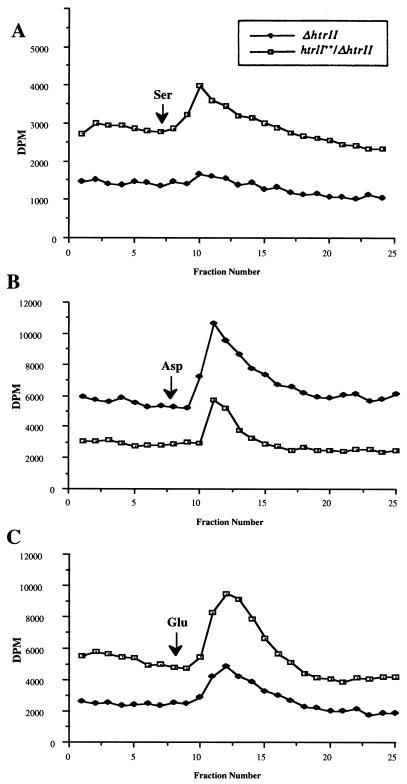

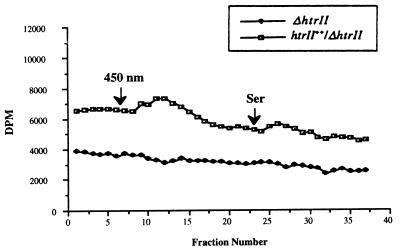

The physiological data above clearly indicate that strain ΔhtrII is defective in chemotactic responses to serine. To demonstrate that HtrII is involved in methylation-demethylation during photostimulation and chemostimulation, we have studied the methylesterase activities of the deletion and overexpression strains in response to serine and light. Deletion mutant ΔhtrII does not exhibit a transient increase in methanol production upon chemostimulation with serine, while responses to Asp and Glu are comparable for strains ΔhtrII and htrII++/ΔhtrII (Fig. 3). The same result was obtained after light stimulation (450 nm) followed by the addition of serine (Fig. 4). These results show that the halobacterial strain lacking HtrII does not modulate methylesterase activity upon stimulation with both light and serine. The low level of methanol evolution and the delayed chemotactic ring formation in agarose-in-plug bridge assays observed for strain ΔhtrII reflect the possibility of organizational and functional sharing among the 13 known transducers of H. salinarum. We cannot exclude the possibility that serine might be sensed by transducers other than HtrII, including the four soluble transducers (3, 11). Indeed, we have demonstrated that stimulation by Asp and Glu causes demethylation of two different transducers (the soluble transducer HtrXI and the putative membrane-bound transducer HtrVII) at the same time (4). The amplitudes of the transient increase in methanol evolution after serine stimulation and photostimulation are comparable. These results indicate that the methyl group turnover rates in the putative methylation sites of HtrII by methylesterase induced by chemostimulation and photostimulation should be similar.

FIG. 3.

Chemostimulus-induced changes in the rate of release of [3H]methyl groups under conditions of a nonradioactive chase of an htrII deletion mutant (ΔhtrII) and an htrII overexpression mutant (htrII++/ΔhtrII) in response to serine (A), aspartate (B), and glutamate (C). Cells were prepared according to Alam et al. (2).

FIG. 4.

Photostimulation and chemostimulation cause a transient increase in methanol evolution in the overexpression strain but not in the deletion strain. Cells were prepared as described for Fig. 3. The duration of the pulse was 2 min.

We have established that HtrII is a phototransducer and a chemotransducer. Thus, it is reasonable to postulate that there must be a mechanistic dissection of chemotactic and phototactic signaling in HtrII or the presence of specific regions or amino acid sequences in HtrII that are crucial for photostimulation and chemostimulation. Further studies are under way to trace residues to identify their effects in phototactic and chemotactic signaling and adaptation.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Berger and P. Patek for critical reading and discussion of the manuscript and Dyall Smith, University of Melbourne, Melbourne Australia, for kindly providing us with the shuttle vector pMDS20.

This work was supported by a University of Hawaii Intramural Project Development Award and National Institutes of Health grant R55 GM53149-01A1 to M.A.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alam M, Oesterhelt D. Morphology, function and isolation of halobacterial flagella. J Mol Biol. 1984;176:459–475. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(84)90172-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam M, Lebert M, Oesterhelt D, Hazelbauer G L. Methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins in Halobacterium halobium. EMBO J. 1989;8:631–639. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brooun, A., F. Villablanca, T. Freitas, and M. Alam. Unpublished data.

- 4.Brooun A, Zhang W, Alam M. Primary structure and functional analysis of the soluble transducer protein HtrXI from the archaeon Halobacterium salinarum. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2963–2968. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.2963-2968.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoff W D, Jung K-H, Spudich J L. Molecular mechanism of photosignaling by archaeal sensory rhodopsins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1997;26:223–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macnab R M. Flagella. In: Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- 6a.Macnab R M. Motility and chemotaxis. In: Neidhardt F C, Ingraham J L, Low K B, Magasanik B, Schaechter M, Umbarger H E, editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium: cellular and molecular biology. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1987. pp. 732–759. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schimz A, Hildebrand E. Chemosensory responses of Halobacterium halobium. J Bacteriol. 1979;140:749–753. doi: 10.1128/jb.140.3.749-753.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spudich E N, Zhang W, Alam M, Spudich J L. Constitutive signaling by phototaxis sensory rhodopsin II from disruption of its protonated Schiff base-Asp-73 interhelical salt bridge. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4960–4965. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.4960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spudich J L. Color sensing in the Archaea: a eukaryotic-like receptor coupled to a prokaryotic transducer. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7755–7761. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7755-7761.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu H-S, Alam M. An agarose-in-plug bridge method to study chemotaxis in the Archaeon Halobacterium salinarum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;156:265–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang W, Brooun A, MacCandless J, Banda P, Alam M. Signal transduction in the Archaeon Halobacterium salinarum is processed through three subfamilies of 13 soluble and membrane-bound transducer proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:4649–4654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Brooun A, Mullner M, Alam M. The primary structures of the Archaeon Halobacterium salinarum blue light receptor sensory rhodopsin II and its transducer, a methyl-accepting protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8230–8235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu, J., E. N. Spudich, M. Alam, and J. L. Spudich. Effects of substitutions D73E, D73N, D103N, and V106M on signaling and pH titration of sensory rhodopsin II. Photochem. Photobiol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]