Abstract

Current chemical recycling of bulk synthetic plastic, polyethylene (PE), operates at high temperature/pressure and yields a complex mixture of products. PE conversion under mild conditions and with good selectivity toward value-added chemicals remains a practical challenge. Here, we demonstrate an atomic engineering strategy to modify a TiO2 photocatalyst with reversible Pd species for the selective conversion of PE to ethylene (C2H4) and propionic acid via dicarboxylic acid intermediates under moderate conditions. TiO2-supported atomically dispersed Pd species exhibits C2H4 evolution of 531.2 μmol gcat−1 hour−1, 408 times that of pristine TiO2. The liquid product is a valuable chemical propanoic acid with 98.8% selectivity. Plastic conversion with a C2 hydrocarbon yield of 0.9% and a propionic acid yield of 6.3% was achieved in oxidation coupled with 3 hours of photoreaction. In situ spectroscopic studies confirm a dual role of atomic Pd species: an electron acceptor to boost charge separation/transfer for efficient photoredox, and a mediator to stabilize reaction intermediates for selective decarboxylation.

Atomic-scale catalysts boost upcycling of plastic waste under light.

INTRODUCTION

The widespread use of plastic products demands proper end-of-life management to reduce environmental threats from landfills and recover value-added products from waste (1, 2). Polyolefins such as polyethylene (PE) account for more than 60% of all plastic waste (3). However, PE waste is now processed via pyrolysis or gasification at high temperatures (>400°C), with complex product compositions (including hydrocarbon gases, oils, waxes, and coke) and substantial energy consumption (4, 5). Although different reaction systems (such as Fenton and chemical oxidation) have been developed to achieve low-temperature decomposition of PE waste (6, 7), the selective production and separation of value-added products remain practically challenging.

Solar-driven photocatalysis offers a clean and sustainable approach to carry out chemical conversions under ambient conditions (8–10). In tandem with low-temperature depolymerization, it holds promise for photocatalytic conversion of PE waste via intermediates into valuable fuels and chemicals under mild conditions. Ethylene (C2H4) is an important chemical feedstock, which is industrially extracted by high-temperature (>800°C) steam cracking (11, 12). PE waste is an untapped resource for C2H4 generation (13), but solar-driven PE-to-C2H4 conversion is practically difficult. The chemical inertness of nonpolar polymers and the uncontrollable reactivity of radical intermediates impede PE conversion and product selectivity (14–17). In addition, C2H4 has been used as a feedstock for valued propionic acid production, for instance, in the Reppe process (18). This industrial process still requires elevated pressure/temperature and generates by-products (19). In contrast, photocatalytic synthesis of propionic acid from plastic waste is a more sustainable and greener route. Despite such potential, the selective conversion of plastic waste to C2H4 and propionic acid under moderate conditions is extremely challenging and rarely explored.

Recently, atomically engineered catalysis has attracted substantial attention in chemical conversions because of maximal metal atom utilization, tunable atomic configuration, and special surface atom-support interaction (20, 21). Engineering abundant atomic-scale sites in catalysts becomes a promising strategy to achieve high efficiency and tailor product selectivity in emerging reactions, such as upcycling of plastic waste (22, 23). Li et al. (24) reported an N-bridged Co, Ni dual atom catalyst for conversion of polystyrene (PS) waste to ethylbenzene. Delicately designed atomic-scale sites enabled adsorption of styrene molecules and C═C bond activation, achieving 95 wt % PS conversion and 92 wt % ethylbenzene yield. On the basis of the understanding of the structure-activity relationship of atomic-scale active sites (25), the atomically engineered photocatalysts that enable photo-generated charge separation/transfer and boost surface redox reactions can be rationally designed and fabricated. This would be beneficial and provide promising opportunities for photocatalytic upcycling of PE waste.

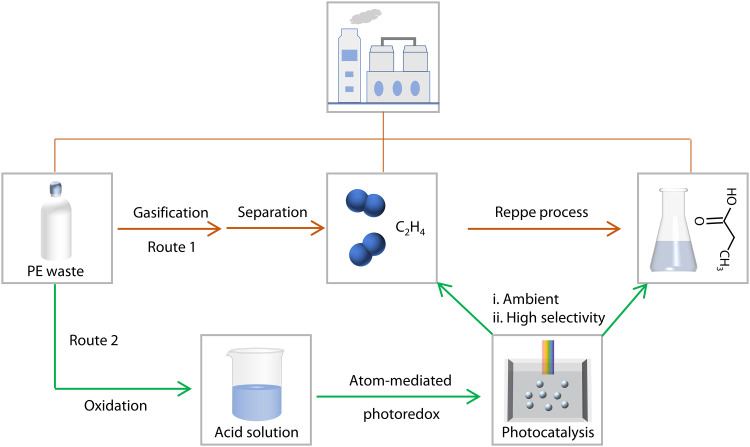

Here, we report the concurrent production of C2H4 and propionic acid with high selectivity from PE waste using an atomically engineered photocatalyst (Fig. 1). We demonstrate that TiO2 nanosheets with atomically dispersed Pd species (Pd1-TiO2) exhibit C2 hydrocarbon evolution of 1033 μmol gcat−1 hour−1 with 51.4% C2H4, and propanoic acid production of 164.4 μmol hour−1 with a selectivity of 98.8% in liquid products. The integrated process allows for the conversion of PE with a C2 hydrocarbon yield of 0.9% and a propionic acid yield of 6.3% under mild conditions. Pd1-TiO2 can generate C2H4 from PE solutions using practically feasible rainwater, seawater, and simulated nitric acid wastewater. This study demonstrates that atomically dispersed Pd species act as electron acceptors to accelerate charge separation/transfer and expose abundant Pd sites to boost photocatalytic activity. We confirm that photoexcited reversible Pd species stabilize radical intermediates and mediate oxidative decarboxylation, boosting the selective generation of C2H4, based on in situ spectroscopic studies.

Fig. 1. Routes for PE waste conversion.

Route 1, conventional gasification of PE waste, involves high temperature/pressure reactions, product separation, and post-synthesis process to generate C2H4 and propionic acid. Route 2, photocatalytic PE upcycling to C2H4 and propionic acid with high selectivity and under mild conditions.

RESULTS

Synthesis and structure characterizations of TiO2 and Pd1-TiO2

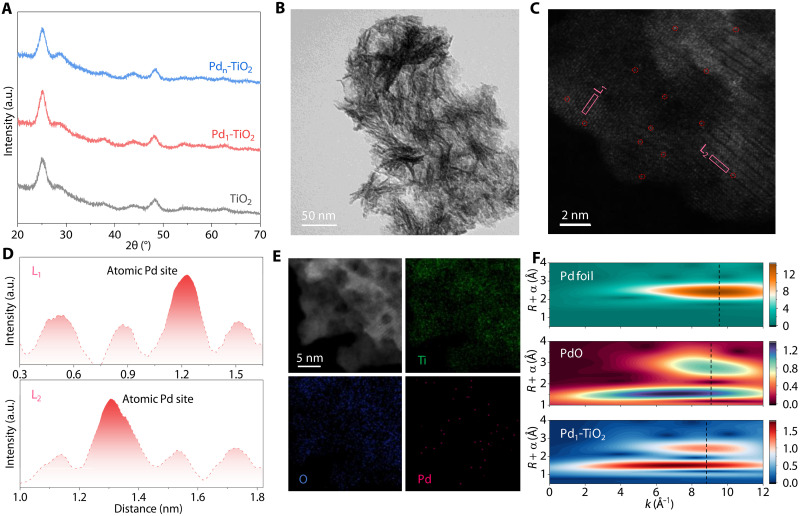

Given excellent stability and activity, TiO2 was prepared as a support photocatalyst via a solvothermal method. Atomically dispersed Pd species were anchored on TiO2 via an icing-assisted photoreduction method (26), forming Pd1-TiO2 photocatalysts. TiO2-supported Pd nanoparticles were synthesized without freezing treatment to get Pdn-TiO2 photocatalysts. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns for TiO2, Pd1-TiO2, and Pdn-TiO2 exhibit the diffraction peaks for anatase TiO2 without Pd-related features, indicating that Pd species are highly dispersed (Fig. 2A). High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) and high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images confirm that TiO2 photocatalysts are nanosheet structures with a measured lattice spacing of 0.35 nm (Fig. 2B and fig. S1, A to C). This finding is consistent with the (101) plane of anatase TiO2 (9). HAADF-STEM image of Pd1-TiO2 exhibits atomically dispersed Pd elements on TiO2 nanosheets, marked by red dashed lines (Fig. 2C). Atomic Pd sites can be identified on the basis of the atomic intensity profiles along the pink rectangles (Fig. 2D). Energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) mappings highlight a homogeneous distribution of Pd, Ti, and O elements (Fig. 2E). For a comparison, an HAADF-STEM image of Pdn-TiO2 shows that Pd nanoparticles with sizes of ~4 nm are loaded on TiO2 nanosheets (fig. S1D). The lattice spacing of 0.23 nm corresponds to the (111) plane of Pd nanoparticles (27). Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) data confirm that Pd contents in Pd1-TiO2 (0.64 wt %) and Pdn-TiO2 (0.7 wt %) are similar (table S1). Brunauer-Emmett-Teller data demonstrate that the surface area and pore volume for Pd1-TiO2 and Pdn-TiO2 are also similar (fig. S2 and table S1).

Fig. 2. Structure characterizations of TiO2, Pd1-TiO2, and Pdn-TiO2.

(A) XRD patterns for TiO2, Pd1-TiO2, and Pdn-TiO2. (B) HRTEM image and (C) HAADF-STEM image of Pd1-TiO2. (D) Intensity profiles along the pink rectangles in (C). (E) HAADF-STEM image and EDS mapping of Pd1-TiO2. (F) Pd K-edge WT-EXAFS for Pd1-TiO2 and reference samples. a.u., arbitrary units.

Pd K-edge x-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra exhibit that the absorption edges of Pd1-TiO2 and PdO reference are relatively matched but slightly shifted to higher energy in comparison with Pd foil (fig. S3A). These findings confirm that the oxidation state of Pd species in Pd1-TiO2 is close to that of PdO reference (28). Pd K-edge Fourier transform extended x-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra exhibit a major peak at ~1.5 Å for Pd-O coordination and a minor peak at ~2.6 Å for Pd-Ti/Pd coordination shell (fig. S3B) (29, 30). The finding is also confirmed by wavelet-transformed EXAFS (WT-EXAFS) analysis, showing two intensity maxima at ~7.2 and 8.8 Å−1 (Fig. 2F). The first shell Pd-O coordination number is determined to be 3 based on the EXAFS fitting (table S2). The second-shell domain for Pd-metal scattering is distinct from the metallic bonding of Pd foil (R = 2.4 Å and k = 9.7 Å−1), indicating the atomic-level distribution of Pd (29, 30). These findings confirm that the Pd species in Pd1-TiO2 are primarily atomic Pd-O3 moieties formed by the coordination of isolated Pd atoms with three O atoms (31, 32). Trace amounts of metallic Pd may be present, contributing to the minor Pd-metal coordination (fig. S3B) (33–35). To determine the dispersity of Pd, the CO adsorption testing was performed on Pd1-TiO2 and Pdn-TiO2 using diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) (fig. S4). The DRIFTS spectrum of Pd1-TiO2 exhibits a distinct signal at ~2105 cm−1 (fig. S4A), which corresponds to the linear CO adsorption configuration (27, 36). For Pdn-TiO2, only a bridge-adsorbed CO spectrum with a broad peak at ~1950 cm−1 is observed in fig. S4B (27, 36). These findings confirm the atomic dispersion of Pd sites on Pd1-TiO2 (37).

In addition, the chemical state of Pd species in Pd1-TiO2 and Pdn-TiO2 was characterized via high-resolution Pd 3d x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). As shown in fig. S5A, the Pd 3d XPS spectrum for Pdn-TiO2 exhibits two sets of Pd signals. The Pd5/2 signal consists of Pd0 (335.1 eV, 70% by area) and a small amount of Pd2+ (oxidized state) (33, 38). The finding indicates that Pd species in Pdn-TiO2 exist primarily in the form of metallic Pd nanoparticles. This is reinforced by the CO adsorption DRIFTS spectra and HRTEM image of Pdn-TiO2 (figs. S4B and S1D). For Pd1-TiO2 (fig. S5B), the Pd5/2 signal is deconvoluted into two peaks at 335.4 eV (typical for Pd0) and 336.8 eV peak (typical for Pd2+) with relative contents of 61 and 39%, respectively (33, 38, 39). This result indicates that the atomically dispersed Pd species are in the form of mixed valence states of Pd0 and Pd2+.

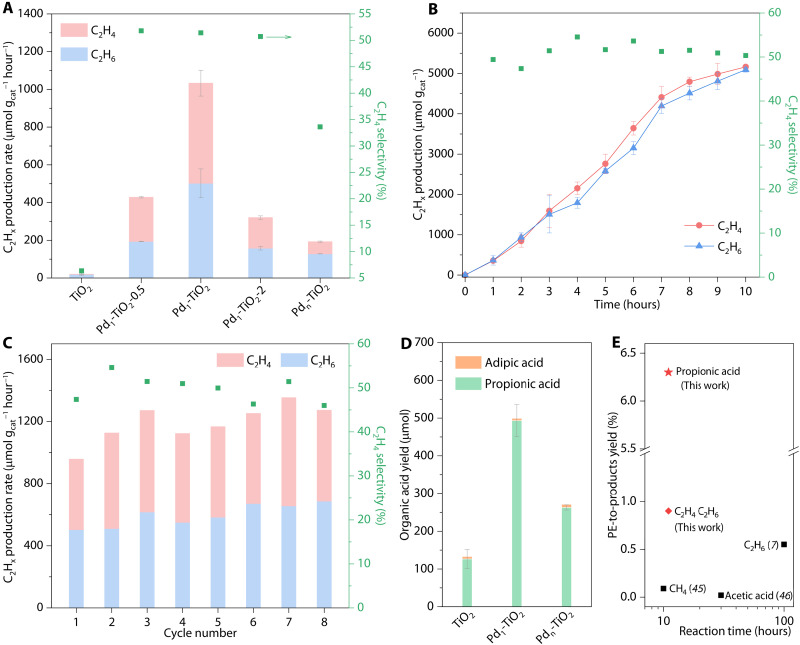

Photocatalytic activity for plastic substrate conversion

Photocatalytic experiments were carried out with succinic acid substrate (i.e., the primary product from PE decomposition) and PE decomposition solution in Ar atmosphere under light-emitting diode (LED) irradiation at room temperature (RT) and atmospheric pressure. The photocatalysts TiO2, Pd1-TiO2, and Pdn-TiO2 and a series of noble metal (i.e., Pt, Au, Ag, and Ru)–modified TiO2 were initially assessed for conversion of succinic acid following 3 hours of irradiation with 365-nm LED (Fig. 3A and fig. S6). The pH value and temperature of the substrate solution were optimized on the basis of the photocatalytic performance of Pd1-TiO2 (tables S3 and S4). Bare TiO2 exhibited low photocatalytic activity and generated low amounts of C2 hydrocarbons (i.e., C2H6 and C2H4) (Fig. 3A). The photocatalytic activity and C2H4 selectivity were substantially boosted by introducing Pd species. As shown in Fig. 3A, Pd1-TiO2 exhibited a C2 hydrocarbon production rate of 1033 μmol gcat−1 hour−1 with, respectively, a boost of 50× and 5.4× over bare TiO2 (20.5 μmol gcat−1 hour−1) and Pdn-TiO2 (192.6 μmol gcat−1 hour−1). Pd1-TiO2 exhibited an apparent quantum efficiency (AQE) of 1.07% at λ = 365 nm. It was also found that the photocatalytic performance exhibits a volcano-like relationship with Pd loadings. The highest C2 hydrocarbon production was achieved on Pd1-TiO2 with 1% Pd loading (i.e., Pd1-TiO2). The C2 hydrocarbon production rates on Pd1-TiO2-0.5 and Pd1-TiO2-2 are determined to be 428.3 and 320.5 μmol gcat−1 hour−1, respectively. The structures of Pd1-TiO2-0.5 and Pd1-TiO2-2 were also characterized by XRD, CO adsorption DRIFTS, and HAADF-STEM (fig. S7). Compared with the optimized sample, Pd1-TiO2-0.5 exhibits a lower activity, probably due to the lack of active sites. Excessive Pd in photocatalysts may result in agglomeration, forming recombination centers for charge carriers and reducing the exposure of active sites. In addition, the C2H4 selectivity of 51.4% (in total generated hydrocarbons) for Pd1-TiO2 is substantially greater than that of bare TiO2 and other metal (i.e., Pt, Au, Ag, and Ru)–modified TiO2 (C2H4 < 10%) (fig. S6). The difference in photocatalytic performance is probably caused by the intrinsic properties of different noble metals, such as the strong hydrogenation capabilities of Pt and Au (7, 15, 40). Photoexcited Pd catalysts are reactive to unsaturated carbon radicals for decarboxylation or cross-coupling (41–43). These findings demonstrate the key role of atomic Pd species in boosting C2H4 production/selectivity.

Fig. 3. Product analysis of photocatalytic experiments with various TiO2 photocatalysts.

(A) C2 hydrocarbon (C2Hx) production for bare TiO2, Pd1-TiO2-0.5, Pd1-TiO2, Pd1-TiO2-2, and Pdn-TiO2 following 3 hours of photoreaction. (B) Time-dependent photocatalytic C2 hydrocarbon production for Pd1-TiO2. (C) Cyclic tests for Pd1-TiO2 with 3 hours per cycle. C2 hydrocarbon production reported in (A) to (C) is expressed per mass of the photocatalyst. C2H4 selectivity is reported on the basis of the total C2Hx yield. (D) Organic acid yields for TiO2, Pd1-TiO2, and Pdn-TiO2 following 3 hours of photoreaction. (E) Activity summary for Pd1-TiO2 and reported photocatalysts for conversion of PE to the valued products. The photocatalysts for reported data are as follows: P25|Pt (7), MoS2/CdS (45), and Nb2O5 (46).

Blank experiments confirmed that no gaseous hydrocarbon is detectable for Pd1-TiO2 in the absence of photocatalysts, light irradiation, and substrates (fig. S8A). The amount of generated C2 hydrocarbons increased almost linearly with illumination time (within 8 hours) and then leveled off. The total production of C2 hydrocarbons reached 10,257.7 μmol gcat−1, together with maintenance of C2H4 selectivity in a continuous 10-hour reaction (Fig. 3B). The photocatalytic performance of Pd1-TiO2 was also retained across eight cyclic tests (Fig. 3C). There was no visible change in phase structure, morphology, and Pd loading of Pd1-TiO2 following photoreaction (fig. S9 and table S5). Regarding Pd chemical states (fig. S9B), the area ratio of Pd2+ to Pd0 increases from 0.64 to 1.12 after cyclic reactions, broadening the Pd peak. This is most likely because of the partial oxidation of atomic Pd species during washing and air drying of post-reaction samples (44). The chemical state of atomic Pd species can be restored upon illumination (fig. S10). This finding hints at the role of atomically dispersed Pd species in trapping photo-generated electrons. The regeneration of photoexcited Pd species may also explain a gradual enhancement of photocatalytic activity during consecutive cyclic tests (Fig. 3C). These findings confirm the excellent stability of the Pd1-TiO2 photocatalyst. In addition, hydrogen (H2) from proton reduction and by-product CO2 by decarboxylation were also detected over Pd1-TiO2 after 3 hours of reaction (table S6) (7). Findings from control experiments confirm that H2 was produced during the photocatalytic reaction in acidic substrate solutions without nitric acid, alkaline substrate solutions, and acetonitrile substrate solutions. Therefore, the H2 evolved likely originates from the succinic acid substrate and water (45). Negligible CO2 was obtained in control experiments without succinate substrate, confirming that the CO2 product originates from substrate conversion (46). No detectable C2H4 was generated in photocatalytic experiments using CO2 as starting reactant (fig. S8B). This finding confirms that C2H4 originates from the direct conversion of succinic acid substrate rather than CO2 reduction.

In the aqueous phase, propionic acid is the major product, along with a trace amount of adipic acid generated. As can be seen in Fig. 3D, Pd1-TiO2 exhibits a high selectivity of 98.8% toward propionic acid with a yield of 493.3 μmol following 3 hours of reaction. Propionic acid was primarily generated via single decarboxylation of succinic acid substrate followed by proton termination (15, 47). Adipic acid was formed as a minor Kolbe-type product by the dimerization of decarboxylative intermediates (7, 48). Compared with bare TiO2, Pd1-TiO2 exhibited a nearly fourfold increase in propionic acid yield with similar product selectivity (Fig. 3D). This shows that the atomically dispersed Pd species boost the substrate oxidation on TiO2. Following 3 hours of photocatalytic reaction, the total carbon yield of gaseous and liquid products was computed to be 98% (based on the consumed substrate). This result confirms that the detected carbon-based products originated almost exclusively from the substrate.

PE was also used as reaction substrates following pretreatment in nitric acid solution. PE pretreatment was completed with a carbon yield of 39.2% (moles of carbon in liquid products detected in the PE decomposition solution). The pure PE decomposition solution was diluted before photoreaction to minimize the light loss caused by the solution (fig. S11). Subsequently, photocatalytic experiments using the PE decomposition solution were performed with the Pd1-TiO2 photocatalyst. The production of C2 hydrocarbons during 3 hours of reaction was determined to be 168.1 μmol gcat−1 with a C2H4 selectivity of 42%, which is decreased compared to the studies with the succinic acid substrate (table S7). This finding is likely due to a nearly fivefold lower concentration of the succinic acid component in the PE solution than in the pure substrate solution (table S8). Other components in PE solution (e.g., glutaric acid) also consumed photo-generated charges and were converted into a low amount of C3 hydrocarbons (evolution of 3.9 μmol gcat−1 hour−1). Side products could compete with the primary reaction for succinic acid and reduce generation of major products. The overall PE to C2 hydrocarbon yield was determined to be 0.9%, while that from PE to propionic acid was 6.3%. Despite operating under harsh conditions, Pd1-TiO2 exhibits substantially greater activity for PE-to-valued chemicals conversion than reported photocatalytic systems (Fig. 3E). Analysis of the available reports on different photocatalytic treatments of plastic waste is also included in table S7. A comparison between our photocatalysis and high-temperature thermocatalytic conversion of PE waste is presented in fig. S12. In addition, Pd1-TiO2 can generate C2 hydrocarbons from PE waste using more available seawater, rainwater, and simulated nitric acid wastewater as solvents (table S9). Pd1-TiO2 retained its photocatalytic activity in impurity-containing natural waters, evidencing the excellent stability of the photocatalyst (49). These findings show the practical potential of Pd1-TiO2 photocatalysts for plastic conversion.

Photocatalytic mechanistic study

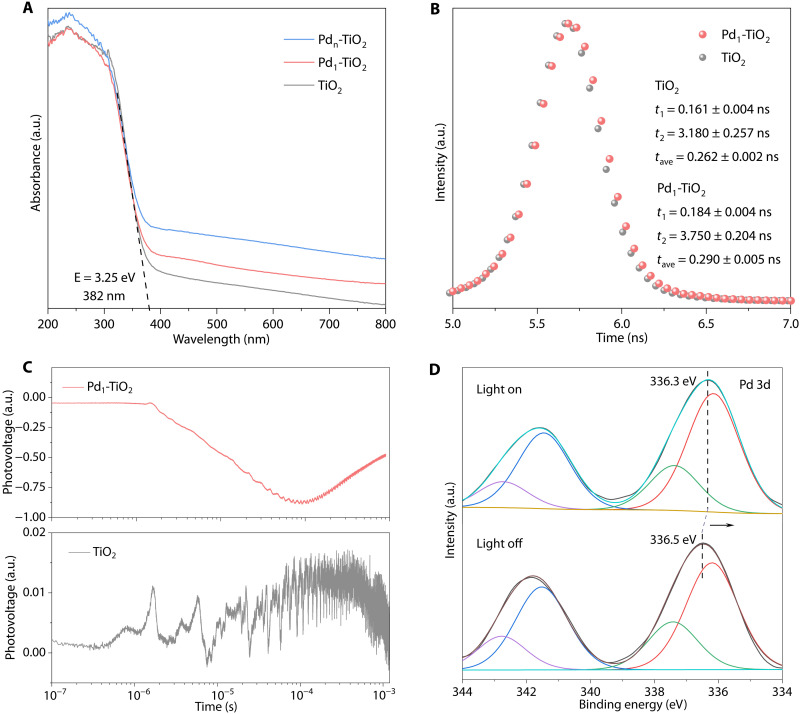

The reason for boosted activity/selectivity for atomically dispersed Pd-modified TiO2 was quantitatively assessed. According to ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (UV-DRS), TiO2, Pd1-TiO2, and Pdn-TiO2 exhibit similar UV absorption (Fig. 4A). However, Pd-boosted visible absorption is not in the excitation wavelength range and thus does not contribute to the photocatalytic activity of Pd1-TiO2. These findings confirm that light absorption is not the decisive reason for the difference in photocatalytic performance. In addition, TiO2 and Pd1-TiO2 exhibited a similar absorption edge with a bandgap of 3.25 eV, evidencing that Pd modification has no apparent influence on the bandgap energy (Fig. 4A). The energy band structures for TiO2 and Pd1-TiO2 were determined via Mott-Schottky analysis and XPS valence band (VB) spectrum (fig. S13, A, B, D and E). The flat band potential for TiO2 is −0.54 V versus the Ag/AgCl electrode. The calibrated VB edge potential and the conduction band (CB) edge for TiO2 are therefore computed to be 2.89 and −0.36 V versus reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE), respectively. In parallel, Pd1-TiO2 exhibits a VB edge potential of 2.87 V and a CB edge potential of −0.38 V versus RHE. The energy band structures for these two materials are summarized in fig. S13 (C and F).

Fig. 4. Light absorption and charge separation/transfer on photocatalysts.

(A) UV-DRS spectra of TiO2, Pd1-TiO2, and Pdn-TiO2. (B)Transient PL and (C) transient SPV spectra of TiO2 and Pd1-TiO2. (D) Pd 3d XPS spectra of Pd1-TiO2 in the dark and under illumination.

The photo-generated charge separation/transfer in materials was studied via in situ and time-resolved characterizations. The transient photoluminescence (PL) spectra for TiO2 and Pd1-TiO2 are shown in Fig. 4B. Pd1-TiO2 exhibits a slower PL decay with a fitted average lifetime (τave) of 0.290 ± 0.005 ns compared with TiO2 (τave = 0.262 ± 0.002 ns). This finding confirms that the recombination of photo-generated electrons and holes is suppressed by atomically dispersed Pd species. This is reinforced by the transient surface photovoltage (SPV) spectroscopy, where Pd1-TiO2 exhibits a slower SPV decay than TiO2, evidencing Pd species-boosted charge separation/transfer (Fig. 4C) (50, 51). As shown in Fig. 4C, a positive SPV signal is observed for TiO2. This result indicates that compared to photo-generated electrons, more holes accumulate on the surface of TiO2. In contrast, Pd1-TiO2 exhibits a negative SPV signal, which indicates that more photo-generated electrons than holes migrate from the bulk to the surface of Pd1-TiO2 (52). In addition, the SPV intensity for Pd1-TiO2 is substantially higher than those for TiO2 and Pdn-TiO2 (Fig. 4C and fig. S14). This indicates that more photo-generated charges accumulate on the Pd1-TiO2 surface (53). These findings confirm that the atomically dispersed Pd species boost the transfer of photo-generated electrons to the surface of photocatalysts. The electron transfer pathway was determined via photo-irradiated XPS. The high-resolution Pd 3d XPS spectrum for Pd1-TiO2 exhibits a Pd signal centered at ~336.5 eV (Fig. 4D), which corresponds to the Pd2+ characteristic binding energy (38). This finding is consistent with the XANES results (fig. S3A). Under light irradiation, the Pd 3d peak of Pd1-TiO2 is shifted negatively by 0.2 eV toward lower binding energy (Fig. 4D and fig. S15A), accompanied by positively shifted binding energy in O 1s (fig. S15B), indicating electron transfer from TiO2 to atomic Pd species. Moreover, the Pd0 signal proportion increases from 68 to 73% during illumination, along with a decrease in the signal of oxidized Pd2+ species (Fig. 4D and table S10). These findings confirm that the atomically dispersed Pd species function as electron acceptors under illumination and extract electrons from TiO2 via the interaction between Pd atoms and TiO2 support, while photo-generated holes are localized on TiO2. This is consistent with transient SPV and EXAFS findings.

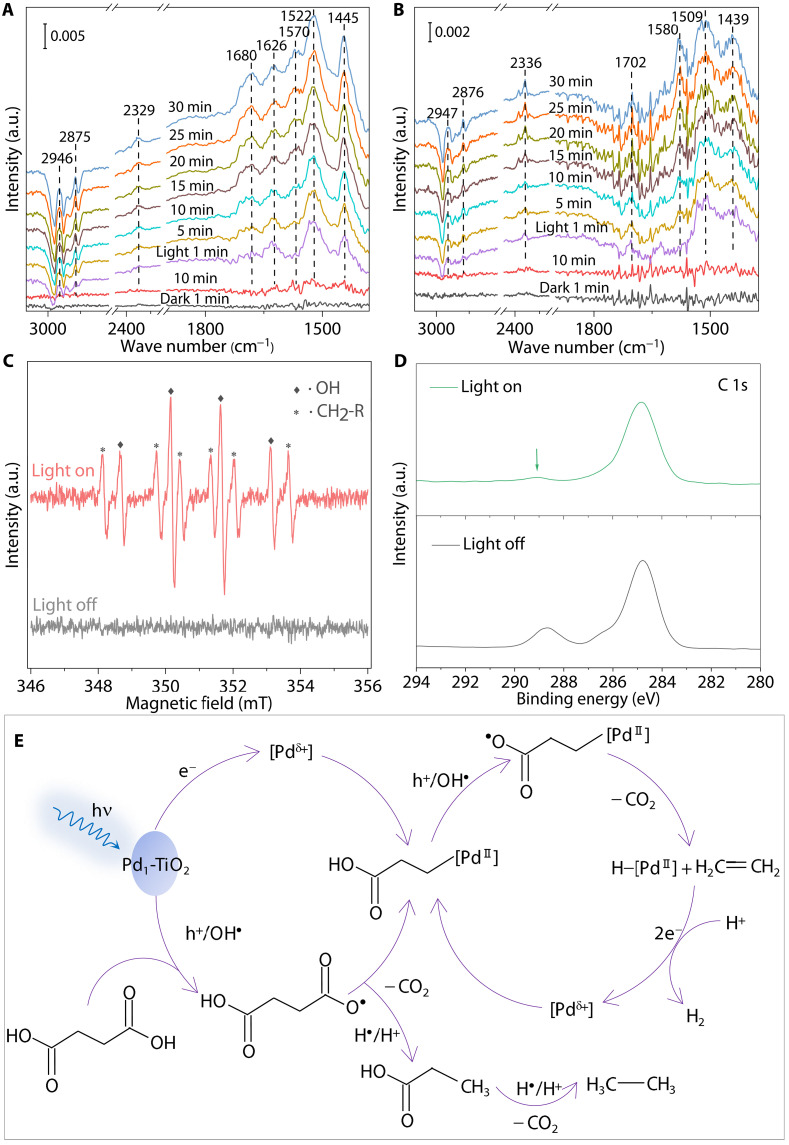

The surface reaction pathway was investigated via in situ DRIFTS. Figure 5A exhibits the DRIFTS spectrum of Pd1-TiO2 in the presence of succinic acid substrate, where several characteristic signals appear with illumination. The peaks at 1570 and 1445 cm−1 are attributed to the asymmetric and symmetric vibrational modes of dicarboxylic acid, respectively (54, 55). A nondissociated vibrational absorbance (1680 cm−1) of the carboxylic group (-COOH) is observed, which primarily originates from substrate adsorption (54, 56). Following light irradiation, these -COOH vibrational modes for the substrate emerge immediately, evidencing the photo-boosted substrate adsorption and dissociation. In addition, a -COOH vibration (1522 cm−1) related to monocarboxylic acids also appears and substantially increases with extended illumination time (57). This finding confirms the formation of propionic acid (the major product of substrate conversion) on the surface of Pd1-TiO2. The difference in -COOH vibrational modes of mono-/dicarboxylic acids is correlated with the -COOH chelating modes when surface molecules bind to materials (54, 58). The -COOH absorption features in DRIFTS spectra are also confirmed by adsorption experiments with different concentrations of succinic and propionic acids (fig. S16, A and B) (54, 59). The infrared signal at 2329 cm−1 under light irradiation represents a typical C═O stretching vibration for CO2 generated from substrate decarboxylation (60). The C─H stretching vibrations for alkyl species are detected at 2946/2875 cm−1 with illumination (15, 60). This feature most likely originates from the decarboxylative intermediates or products adsorbed on metal oxides. The bands for intermediates and products for Pd1-TiO2 are substantially stronger compared to those on the TiO2 spectrum (Fig. 5B). The finding confirms that the atomically dispersed Pd species boost substrate conversion with photo-generated charges, consistent with photocatalytic performance. A distinct band at 1626 cm−1 attributable to C═C stretching for unsaturated alkyl intermediates is observed for Pd1-TiO2 and Pdn-TiO2 (Fig. 5A and fig. S16C) (61, 62), whereas no similar absorbance is detectable in the TiO2 spectrum (Fig. 5B). This is consistent with the selective generation of C2H4 over Pd1-TiO2. In situ DRIFTS results and photocatalytic performance confirm the important role of atomically dispersed Pd species in boosting the formation of alkyl intermediates, products propionic acid, and C2H4 under light irradiation.

Fig. 5. Detection of intermediates and active species during photoreactions.

In situ DRIFTS spectra for the substrate conversion on (A) Pd1-TiO2 and (B) TiO2. (C) In situ EPR spectra for Pd1-TiO2 with the substrate, DMPO, and illumination. (D) In situ high-resolution C 1s XPS spectra for Pd1-TiO2 with the substrate and illumination. (E) Possible reaction routes for photocatalytic substrate conversion on Pd1-TiO2.

To determine the reaction intermediates, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) was performed with the succinic acid substrate in the presence of 5,5′-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as a spin-trapping agent. As can be seen in Fig. 5C, the signals of carbon-centered alkyl radical (∙CH2R) and hydroxyl radical (∙OH) are observed for Pd1-TiO2 (36, 63). The alkyl radical is recognized as the key intermediate for Kolbe oxidations (15, 64). In comparison, only ∙OH is detected on bare TiO2 upon addition of the substrate (fig. S17A). This finding indicates that atomic Pd species boost generation and stabilization of alkyl intermediate, which is well in agreement with DRIFTS results. No alkyl radical is detectable for both Pd1-TiO2 and TiO2 when EPR was performed in the absence of substrates (fig. S17B). The result confirms that alkyl radicals observed in Fig. 5C are derived from substrate conversion. ∙OH is typically formed because of the oxidation of water/hydroxyl groups by photo-generated holes (65, 66). Pd1-TiO2 exhibits a stronger ∙OH signal than TiO2 in the absence of substrate (fig. S17B), evidencing more efficient generation of ∙OH on Pd1-TiO2. The boost in ∙OH generation results from the charge separation improved by atomic Pd species, which is consistent with findings from transient SPV and PL. In addition, a decrease in ∙OH signal for TiO2 is evident upon the addition of substrate (fig. S17A), indicating ∙OH consumption in the presence of substrate. This point is underscored by the photocatalytic experiment using ∙OH scavengers (tert-butanol), in which C2 hydrocarbon production on Pd1-TiO2 was reduced by nearly 70% during 3 hours of photoreaction (fig. S8B). Therefore, photo-generated holes and ∙OH are the main active species for substrate oxidation under anaerobic conditions.

Photo-generated holes or ∙OH convert the substrate into propionic acid intermediates (64), likely the alkyl radicals detected by DRIFTS and EPR. This radical intermediate is highly reactive and is quenched by H protons to yield propionic acid (15). The minor product, adipic acid, is formed via radical dimerization (7). Comparative experiments with propionic acid as the starting substrate indicate that the oxidative decarboxylation of propionic acid mainly produces alkanes (C2H4/C2H6 ratio for Pd1-TiO2 decreases to 1:12) (fig. S8B). Therefore, this process primarily generates C2H6 while barely contributing to C2H4 generation (15, 16). No C2H4 was detectable using C2H6 as the reactant (fig. S8B), which provides evidence that C2H4 does not come from the oxidative dehydrogenation of alkanes. Given excellent hydrogen transfer on TiO2-based photocatalysts (7, 67), C2H4 generation via double decarboxylation of substrate molecules is also excluded. These findings confirm that C2H4 is derived from the direct conversion of succinic acid, where the reactivity of the radical intermediates is mediated by atomic Pd species toward further decarboxylation to C2H4 rather than hydrogenation or dimerization.

The evolution of reactants and atomic Pd species on the Pd1-TiO2 surface was studied via ex situ and in situ XPS. Figure S18A exhibits the C 1s XPS spectra for Pd1-TiO2 before and after photoreactions (offline measurements). An apparent signal appears at 288.6 eV for the post-reaction sample, which corresponds to the -COOH group (68). This indicates that the generated propionic acid/succinic acid substrates are adsorbed on the surface. The chemical state of atomically dispersed Pd species (i.e., electron acceptors) remained almost unchanged before/following photoreactions (fig. S9B), indicating the reversible feature of atomic Pd species. To determine atomic Pd-mediated charge transfer during photoreactions, photo-irradiated XPS was carried out in the presence of the substrate. The -COOH signal at 288.6 eV is observed in darkness (Fig. 5D) because of the adsorption of substrate molecules on the Pd1-TiO2 surface. The -COOH signal is substantially reduced following light irradiation, indicating the substrate consumption by Pd1-TiO2 (27). In parallel, the electron acceptor Pd maintained a similar chemical state during the photoreaction (fig. S18B), which is explained by the charge transfer between photo-excited Pd species and intermediates, resulting in the reversible property of atomic Pd species (69). The intermediates, alkyl species detected by DRIFT and EPR, could be stabilized by interacting with photo-excited Pd species, eventually forming C2H4 via subsequent decarboxylation. This finding is consistent with molecularly catalyzed decarboxylation reported elsewhere (41, 70).

Possible reaction routes for photocatalytic conversion of succinic acid in PE solution by Pd1-TiO2 are presented in Fig. 5E. Photoexcitation generates electron-hole pairs in Pd1-TiO2. Atomically dispersed Pd sites trap electrons to form active Pdδ+ species. The holes on the surface of TiO2 and/or generated ∙OH drive the oxidative decarboxylation of succinic acid to yield propionic acid radicals as the reaction intermediates. The radical intermediate is either hydrogenated to form propionic acid or stabilized by active Pdδ+ species for subsequent decarboxylation. C2H6 is formed via photocatalytic oxidation of propionic acid. In parallel, Pd-mediated decarboxylation of the intermediate followed by homolytic cleavage of the Pd─C bond can yield C2H4. Following H2 evolution by Pd sites with photo-generated electrons, active Pdδ+ species regenerate and close the cycle.

On the basis of mechanistic studies, several strategies can be considered to boost generation of C2H4 and propionic acid in the future. The hydrogenation capabilities of Pd species and semiconductors can be regulated to boost hydrogenation of propionic acid intermediates and consume excess oxidative species through surface hydrogen atoms, inhibiting its further decarboxylation into C2H6. The reactor can also be engineered to enable spatial separation of products and photocatalysts and suppress overoxidation of target products. In addition, the development of photocatalysts with high loading of metal single atoms favors the separation/transfer of photo-generated charges and the exposure of active sites, thereby improving the overall photocatalytic performance and target product yields.

DISCUSSION

We report a benchmark performance of upcycling PE plastic waste under mild conditions by engineering an atomic Pd-mediated photoredox cycle. Photoactivated atomic Pd species on TiO2 were demonstrated to boost charge separation/transfer and mediate oxidative decarboxylation, yielding the desired C2H4 and propionic acid with high selectivity. Robust and recyclable Pd1-TiO2 exhibits a C2H4 evolution of 531.2 μmol gcat−1 hour−1, and a propionic acid production of 164.4 μmol hour−1 with 98.8% selectivity. The overall reaction delivers a yield of 7.2% of C2 hydrocarbons and propionic acid from plastic waste. This work explores atomic engineering design of photocatalysts for plastic upcycling via modulation of intermediate conversion. The reported findings are of practical interest for the selective and stable generation of light olefins and organic acids via plastic valorization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of TiO2 nanosheets

TiO2 nanosheets were synthesized via a solvothermal method. Solution A: 0.24 g of P123 was mixed with 2.025 ml of absolute ethanol under stirring. Solution B: 0.45 ml of titanium isopropoxide was added dropwise to 0.7 ml of 5 M HCl solution under vigorous stirring. Solution B was then drop-added into solution A, followed by stirring for 45 min. Following mixing with 15 ml of ethylene glycol, the resulting solution was transferred to a 50-ml Teflon-lined autoclave and maintained at 145°C for 20 hours. Following cooling to RT, the products were washed four times with absolute ethanol. The final products were dried at RT for 12 hours in a vacuum oven and then calcined at 300°C in a muffle furnace for 6 hours.

Preparation of metal-modified TiO2 photocatalysts

Pd1-TiO2 was synthesized via an icing-assisted photoreduction method. Fifty milligrams of TiO2 nanosheets was dispersed in 12.5 ml of ultrapure water under sonication for 30 min. Then, 0.14 ml of 34 mM sodium tetrachloropalladate solution was added to the above suspension under continuous stirring in Ar. The resultant solution was rapidly frozen with liquid nitrogen, followed by a 300-W Xe lamp irradiation for 4 min. The products were washed several times with ultrapure water and dried at RT in a vacuum for 12 hours. The synthesis used to prepare other noble metal-loaded (Pt, Au, Ru, and Ag) TiO2 is analogous to that for Pd1-TiO2. The concentrations of various metal precursors were controlled at 1% by weight of the TiO2 support. Pdn-TiO2 was synthesized by a photoreduction method without icing treatment. Fifty milligrams of TiO2 was dispersed in a solution of 45 ml of ultrapure water and 5 ml of methanol under sonication for 30 min. Following the addition of 0.14 ml of 34 mM sodium tetrachloropalladate solution, the suspension was stirred for 30 min in Ar. Afterward, the resulting suspension was stirred under irradiation with a 300-W Xe lamp irradiation for 3 hours. The products were washed several times with ultrapure water and dried under vacuum at 60°C for 12 hours.

Physicochemical characterizations

HRTEM was performed on an FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit TEM. HAADF-STEM images and EDS spectra were determined using an FEI Titan Themis 80-200 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). XRD patterns were determined on a Miniflex 600 x-ray diffractometer (Rigaku) using Cu Kα radiation. EPR spectra were determined on a Bruker EMX PLUS. XPS analysis was carried out on a Kratos Axis Ultra with a delay-line detector photoelectron spectrometer. Photo-irradiated XPS data were collected with a Sphera II XPS system (Omicron), and an LED light was used to excite the photocatalysts. Hard x-ray EXAFS measurements were conducted on the hard x-ray spectroscopy beamline of the Taiwan Synchrotron. UV-DRS spectra were determined on a UV-vis 2600 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu). Transient PL spectra were determined at RT using an FLS1000 spectrometer (Edinburgh Instrument). A home-built apparatus introduced by Kang et al. (71) was used to acquire transient SPV spectra. An ICP-OES 7700 (Agilent) was used to determine the Pd loading in photocatalysts. An ASAP 2020 apparatus was used to determine the surface area and pore structure. In situ DRIFTS spectra were determined using a Nicolet iS20 spectrometer equipped with an HgCdTe (MCT) detector cooled with liquid nitrogen. The photocatalysts were placed in a reactor (Harrick Scientific) and irradiated with 365-nm LED light. All electro-/photoelectrochemical measurements were determined on a CHI 760E workstation using a standard three-electrode system in 0.5 M sodium sulfate aqueous solution. The working electrode was a 15 mm–by–10 mm fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) glass coated with photocatalysts. A slurry, TiO2 or Pd1-TiO2, containing 3 mg of photocatalysts, 4.5 mg of polyethylene glycol, and 0.3 ml of ethanol was prepared and applied to the FTO glass via the doctor-blade method. The coated glass was dried naturally. The counter electrode was a Pt-foil and the reference electrode was Ag/AgCl.

Substrate pretreatment

PE powder (300 mg; Mw ~ 4000 and Mn ~ 1700) was dispersed in 15 ml of 7% nitric acid solution in a Teflon-lined autoclave and heated at 160°C for 8 hours. The PE decomposition solution was diluted five times with ultrapure water for photocatalytic reactions.

Photocatalytic evaluation

Photocatalytic performance of the materials was determined in a 160-ml custom-made batch reactor at RT and ambient pressure. Ten milligrams of photocatalyst powder was dispersed by sonication in 10 ml of 0.1 M nitric acid solution containing 10 mg ml−1 of succinic acid or 10 ml of 2 mg ml−1 of PE decomposition solution. Natural seawater was collected from the Southern Ocean in Australia and filtered to remove solids and microorganisms before tests. Natural rainwater was harvested in Adelaide City (autumn), Australia. Simulated nitric acid wastewater is a PE breakdown solution containing common metal ion contaminants such as copper, iron, nickel, and aluminum (50 parts per million in total). High-purity Ar gas was purged into the photocatalyst suspension for 20 min to remove residual air. The reactor was irradiated using a high-power 365-nm LED (PLS-LED100C, Beijing Perfectlight) under continuous stirring. At specific intervals, 100 μl of headspace gas was sampled from the reactor and quantified with gas chromatography (Agilent 7890B and Agilent 8890). In parallel, an aliquot of the reaction solution was withdrawn from the reactor and then immediately filtered to remove any photocatalyst. The concentrations of substrate and products in each aliquot were determined via high-performance liquid chromatography (Thermo Fisher Scientific RefractoMax 520). The yield of plastic to products was computed from

| (1) |

Cevoluted products refers to the detected product (in moles) multiplied by the corresponding number of carbon atoms; Cplastics is the total carbon atoms used in PE (in moles).

The AQE of Pd1-TiO2 was determined under monochromatic irradiation at 365 nm. Headspace gas was analyzed via gas chromatography, and AQE was computed from

| (2) |

For the stability test, each cycle of photocatalytic experiments lasted for 3 hours, between which the photocatalyst was rinsed and the substrate solution was renewed. Following the third run, the photocatalyst was washed and dried in an oven at 40°C for 10 hours. The photocatalytic experiment was then run for five cycles until completion without drying the spent photocatalyst.

Acknowledgments

We thank the soft x-ray spectroscopy beamline and the x-ray absorption spectroscopy beamline of Australian Synchrotron. We thank A. Slattery for help with HAADF-STEM testing, D. Wang and H. Xu for assistance with XPS measurements, and Y. Zhang, M. Guo, A. Talebian Kiakalaieh, and E. Mohamed Mahmoud Hashem for assistance with the gas chromatography and light sources.

Funding: This work was supported by Australian Research Council grants (FL170100154, CE230100032, DP230102027, LP210301397, and FT230100192). S.Z. was supported by the Chinese CSC Scholarship Program.

Author contributions: S.-Z.Q. supervised the overall project and reviewed and corrected the manuscript (MS). S.Z. conceived the idea, designed/performed the experiments, and wrote/revised the MS. J.R. revised the MS. M.J. reviewed and corrected the MS. Y.Q. and L.J. conducted SPV measurements and data processing. B.X. helped with photo-irradiated XPS, EPR, and ICP measurements. All authors discussed findings and agreed on the MS.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S18

Tables S1 to S10

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.T. Uekert, C. M. Pichler, T. Schubert, E. Reisner, Solar-driven reforming of solid waste for a sustainable future. Nat. Sustain. 4, 383–391 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 2.R. Geyer, J. R. Jambeck, K. L. Law, Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700782 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.X. Jia, C. Qin, T. Friedberger, Z. Guan, Z. Huang, Efficient and selective degradation of polyethylenes into liquid fuels and waxes under mild conditions. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501591 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.F. Zhang, M. Zeng, R. D. Yappert, J. Sun, Y.-H. Lee, A. M. LaPointe, B. Peters, M. M. Abu-Omar, S. L. Scott, Polyethylene upcycling to long-chain alkylaromatics by tandem hydrogenolysis/aromatization. Science 370, 437–441 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.G. Lopez, M. Artetxe, M. Amutio, J. Bilbao, M. Olazar, Thermochemical routes for the valorization of waste polyolefinic plastics to produce fuels and chemicals. A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 73, 346–368 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 6.K. Hu, P. Zhou, Y. Yang, T. Hall, G. Nie, Y. Yao, X. Duan, S. Wang, Degradation of microplastics by a thermal fenton reaction. ACS EST Engg. 2, 110–120 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7.C. M. Pichler, S. Bhattacharjee, M. Rahaman, T. Uekert, E. Reisner, Conversion of polyethylene waste into gaseous hydrocarbons via integrated tandem chemical-photo/electrocatalytic processes. ACS Catal. 11, 9159–9167 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.H. Nishiyama, T. Yamada, M. Nakabayashi, Y. Maehara, M. Yamaguchi, Y. Kuromiya, Y. Nagatsuma, H. Tokudome, S. Akiyama, T. Watanabe, R. Narushima, S. Okunaka, N. Shibata, T. Takata, T. Hisatomi, K. Domen, Photocatalytic solar hydrogen production from water on a 100-m2 scale. Nature 598, 304–307 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.J. Xie, R. Jin, A. Li, Y. Bi, Q. Ruan, Y. Deng, Y. Zhang, S. Yao, G. Sankar, D. Ma, J. Tang, Highly selective oxidation of methane to methanol at ambient conditions by titanium dioxide-supported iron species. Nat. Catal. 1, 889–896 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.S. Zhang, Y. Zhao, R. Shi, C. Zhou, G. I. N. Waterhouse, Z. Wang, Y. Weng, T. Zhang, Sub-3 nm ultrafine Cu2O for visible light driven nitrogen fixation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 2554–2560 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.S. Nitopi, E. Bertheussen, S. B. Scott, X. Liu, A. K. Engstfeld, S. Horch, B. Seger, I. E. L. Stephens, K. Chan, C. Hahn, J. K. Nørskov, T. F. Jaramillo, I. Chorkendorff, Progress and perspectives of electrochemical CO2 reduction on copper in aqueous electrolyte. Chem. Rev. 119, 7610–7672 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.L. Li, R.-B. Lin, R. Krishna, H. Li, S. Xiang, H. Wu, J. Li, W. Zhou, B. Chen, Ethane/ethylene separation in a metal-organic framework with iron-peroxo sites. Science 362, 443–446 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.G. Lopez, M. Artetxe, M. Amutio, J. Alvarez, J. Bilbao, M. Olazar, Recent advances in the gasification of waste plastics. A critical overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82, 576–596 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 14.T. Li, A. Vijeta, C. Casadevall, A. S. Gentleman, T. Euser, E. Reisner, Bridging plastic recycling and organic catalysis: Photocatalytic deconstruction of polystyrene via a C-H oxidation pathway. ACS Catal. 12, 8155–8163 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Z. Huang, Z. Zhao, C. Zhang, J. Lu, H. Liu, N. Luo, J. Zhang, F. Wang, Enhanced photocatalytic alkane production from fatty acid decarboxylation via inhibition of radical oligomerization. Nat. Catal. 3, 170–178 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 16.B. Kraeutler, A. J. Bard, Heterogeneous photocatalytic decomposition of saturated carboxylic acids on titanium dioxide powder. Decarboxylative route to alkanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 100, 5985–5992 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 17.J. D. Griffin, M. A. Zeller, D. A. Nicewicz, Hydrodecarboxylation of carboxylic and malonic acid derivatives via organic photoredox catalysis: Substrate scope and mechanistic insight. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 11340–11348 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.I. Eş, A. M. Khaneghah, S. M. B. Hashemi, M. Koubaa, Current advances in biological production of propionic acid. Biotechnol. Lett. 39, 635–645 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.-R. Samel, W. Kohler, A. O. Gamer, U. Keuser, S.-T. Yang, Y. Jin, M. Lin, Z. Wang, J. H. Teles. Propionic acid and derivatives, in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry (Wiley-VCH, 2018), pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 20.S. Ji, Y. Chen, X. Wang, Z. Zhang, D. Wang, Y. Li, Chemical synthesis of single atomic site catalysts. Chem. Rev. 120, 11900–11955 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.A. Wang, J. Li, T. Zhang, Heterogeneous single-atom catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 65–81 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22.C. Gao, J. Low, R. Long, T. Kong, J. Zhu, Y. Xiong, Heterogeneous single-atom photocatalysts: Fundamentals and applications. Chem. Rev. 120, 12175–12216 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.B. Xia, Y. Zhang, J. Ran, M. Jaroniec, S.-Z. Qiao, Single-atom photocatalysts for emerging reactions. ACS Cent. Sci. 7, 39–54 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.R. Li, Z. Zhang, X. Liang, J. Shen, J. Wang, W. Sun, D. Wang, J. Jiang, Y. Li, Polystyrene waste thermochemical hydrogenation to ethylbenzene by a N-bridged Co, Ni dual-atom catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 16218–16227 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.R. Li, D. Wang, Understanding the structure-performance relationship of active sites at atomic scale. Nano Res. 15, 6888–6923 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 26.X. Ge, P. Zhou, Q. Zhang, Z. Xia, S. Chen, P. Gao, Z. Zhang, L. Gu, S. Guo, Palladium single atoms on TiO2 as a photocatalytic sensing platform for analyzing the organophosphorus pesticide chlorpyrifos. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 232–236 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.W. Jiang, J. Low, K. Mao, D. Duan, S. Chen, W. Liu, C.-W. Pao, J. Ma, S. Sang, C. Shu, X. Zhan, Z. Qi, H. Zhang, Z. Liu, X. Wu, R. Long, L. Song, Y. Xiong, Pd-modified ZnO-Au enabling alkoxy intermediates formation and dehydrogenation for photocatalytic conversion of methane to ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 269–278 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Y. Guo, Y. Huang, B. Zeng, B. Han, M. Akri, M. Shi, Y. Zhao, Q. Li, Y. Su, L. Li, Q. Jiang, Y.-T. Cui, L. Li, R. Li, B. Qiao, T. Zhang, Photo-thermo semi-hydrogenation of acetylene on Pd1/TiO2 single-atom catalyst. Nat. Commun. 13, 2648 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.J. Shan, C. Ye, C. Zhu, J. Dong, W. Xu, L. Chen, Y. Jiao, Y. Jiang, L. Song, Y. Zhang, M. Jaroniec, Y. Zhu, Y. Zheng, S.-Z. Qiao, Integrating interactive noble metal single-atom catalysts into transition metal oxide lattices. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 23214–23222 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.H. Jin, X. Liu, P. An, C. Tang, H. Yu, Q. Zhang, H.-J. Peng, L. Gu, Y. Zheng, T. Song, K. Davey, U. Paik, J. Dong, S.-Z. Qiao, Dynamic rhenium dopant boosts ruthenium oxide for durable oxygen evolution. Nat. Commun. 14, 354 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.P. Liu, Y. Zhao, R. Qin, S. Mo, G. Chen, L. Gu, D. M. Chevrier, P. Zhang, Q. Guo, D. Zang, B. Wu, G. Fu, N. Zheng, Photochemical route for synthesizing atomically dispersed palladium catalysts. Science 352, 797–800 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.S. Zhang, Y. Zhao, R. Shi, C. Zhou, G. I. N. Waterhouse, L.-Z. Wu, C.-H. Tung, T. Zhang, Efficient photocatalytic nitrogen fixation over Cuδ+-modified defective ZnAl-layered double hydroxide nanosheets. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1901973 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 33.K. Fujiwara, U. Muller, S. E. Pratsinis, Pd subnano-clusters on TiO2 for solar-light removal of NO. ACS Catal. 6, 1887–1893 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 34.L. Kuai, Z. Chen, S. Liu, E. Kan, N. Yu, Y. Ren, C. Fang, X. Li, Y. Li, B. Geng, Titania supported synergistic palladium single atoms and nanoparticles for room temperature ketone and aldehydes hydrogenation. Nat. Commun. 11, 48 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.K. Fujiwara, S. E. Pratsinis, Single Pd atoms on TiO2 dominate photocatalytic NOx removal. Appl Catal B 226, 127–134 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 36.W. Zhang, C. Fu, J. Low, D. Duan, J. Ma, W. Jiang, Y. Chen, H. Liu, Z. Qi, R. Long, Y. Yao, X. Li, H. Zhang, Z. Liu, J. Yang, Z. Zou, Y. Xiong, High-performance photocatalytic nonoxidative conversion of methane to ethane and hydrogen by heteroatoms-engineered TiO2. Nat. Commun. 13, 2806 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.L. Kuai, S. Liu, S. Cao, Y. Ren, E. Kan, Y. Zhao, N. Yu, F. Li, X. Li, Z. Wu, X. Wang, B. Geng, Atomically dispersed Pt/metal oxide mesoporous catalysts from synchronous pyrolysis-deposition route for water-gas shift reaction. Chem. Mater. 30, 5534–5538 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 38.L. Luo, L. Fu, H. Liu, Y. Xu, J. Xing, C.-R. Chang, D.-Y. Yang, J. Tang, Synergy of Pd atoms and oxygen vacancies on In2O3 for methane conversion under visible light. Nat. Commun. 13, 2930 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.L. Liu, A. Corma, Metal catalysts for heterogeneous catalysis: From single atoms to nanoclusters and nanoparticles. Chem. Rev. 118, 4981–5079 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.M. G. Walter, E. L. Warren, J. R. McKone, S. W. Boettcher, Q. Mi, E. A. Santori, N. S. Lewis, Solar water splitting cells. Chem. Rev. 110, 6446–6473 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.W.-M. Cheng, R. Shang, Y. Fu, Irradiation-induced palladium-catalyzed decarboxylative desaturation enabled by a dual ligand system. Nat. Commun. 9, 5215 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.G.-Z. Wang, R. Shang, W.-M. Cheng, Y. Fu, Irradiation-induced Heck reaction of unactivated alkyl halides at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 18307–18312 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.P. Chuentragool, M. Parasram, Y. Shi, V. Gevorgyan, General, mild, and selective method for desaturation of aliphatic amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 2465–2468 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.J. Liu, M. Jiao, L. Lu, H. M. Barkholtz, Y. Li, Y. Wang, L. Jiang, Z. Wu, D. Liu, L. Zhuang, C. Ma, J. Zeng, B. Zhang, D. Su, P. Song, W. Xing, W. Xu, Y. Wang, Z. Jiang, G. Sun, High performance platinum single atom electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. Nat. Commun. 8, 15938 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.M. Du, Y. Zhang, S. Kang, X. Guo, Y. Ma, M. Xing, Y. Zhu, Y. Chai, B. Qiu, Trash to treasure: Photoreforming of plastic waste into commodity chemicals and hydrogen over MoS2-tipped CdS nanorods. ACS Catal. 12, 12823–12832 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 46.X. Jiao, K. Zheng, Q. Chen, X. Li, Y. Li, W. Shao, J. Xu, J. Zhu, Y. Pan, Y. Sun, Y. Xie, Photocatalytic conversion of waste plastics into C2 fuels under simulated natural environment conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 15497–15501 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.C. Cassani, G. Bergonzini, C.-J. Wallentin, Photocatalytic decarboxylative reduction of carboxylic acids and its application in asymmetric synthesis. Org. Lett. 16, 4228–4231 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.D. W. Manley, J. C. Walton, A clean and selective radical homocoupling employing carboxylic acids with titania photoredox catalysis. Org. Lett. 16, 5394–5397 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.J. Guo, Y. Zheng, Z. Hu, C. Zheng, J. Mao, K. Du, M. Jaroniec, S.-Z. Qiao, T. Ling, Direct seawater electrolysis by adjusting the local reaction environment of a catalyst. Nat. Energy 8, 264–272 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 50.D. Li, Y. Zhao, Y. Miao, C. Zhou, L.-P. Zhang, L.-Z. Wu, T. Zhang, Accelerating electron-transfer dynamics by TiO2-immobilized reversible single-atom copper for enhanced artificial photosynthesis of urea. Adv. Mater. 34, e2207793 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.R. Chen, F. Fan, T. Dittrich, C. Li, Imaging photogenerated charge carriers on surfaces and interfaces of photocatalysts with surface photovoltage microscopy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 8238–8262 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D. Gross, I. Mora-Seró, T. Dittrich, A. Belaidi, C. Mauser, A. J. Houtepen, E. D. Como, A. L. Rogach, J. Feldmann, Charge separation in type II tunneling multilayered structures of CdTe and CdSe nanocrystals directly proven by surface photovoltage spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 5981–5983 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.J. Ran, H. Zhang, S. Fu, M. Jaroniec, J. Shan, B. Xia, Y. Qu, J. Qu, S. Chen, L. Song, J. M. Cairney, L. Jing, S.-Z. Qiao, NiPS3 ultrathin nanosheets as versatile platform advancing highly active photocatalytic H2 production. Nat. Commun. 13, 4600 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Y. Sun, W. Chang, H. Ji, C. Chen, W. Ma, J. Zhao, An unexpected fluctuating reactivity for odd and even carbon numbers in the TiO2-based photocatalytic decarboxylation of C2-C6 dicarboxylic acids. Chemistry 20, 1861–1870 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.I. Dolamic, T. Bürgi, Photocatalysis of dicarboxylic acids over TiO2: An in situ ATR-IR study. J. Catal. 248, 268–276 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 56.S. Kang, B. Xing, Adsorption of dicarboxylic acids by clay minerals as examined by in situ ATR-FTIR and ex situ DRIFT. Langmuir 23, 7024–7031 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.L. Chen, Y. Li, X. Zhang, Q. Zhang, T. Wang, L. Ma, Mechanistic insights into the effects of support on the reaction pathway for aqueous-phase hydrogenation of carboxylic acid over the supported Ru catalysts. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 478, 117–128 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 58.I. Dolamic, T. Bürgi, Photoassisted decomposition of malonic acid on TiO2 studied by in situ attenuated total reflection infrared spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 14898–14904 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.S. Zhang, Y. Zhao, Y. Miao, Y. Xu, J. Ran, Z. Wang, Y. Weng, T. Zhang, Understanding aerobic nitrogen photooxidation on titania through in situ time-resolved spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202211469 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.C. Wang, X. Li, Y. Ren, H. Jiao, F. R. Wang, J. Tang, Synergy of Ag and AgBr in a pressurized flow reactor for selective photocatalytic oxidative coupling of methane. ACS Catal. 13, 3768–3774 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.M.-Y. Gao, H. Bai, X. Cui, S. Liu, S. Ling, T. Kong, B. Bai, C. Hu, Y. Dai, Y. Zhao, L. Zhang, J. Zhang, Y. Xiong, Precisely tailoring heterometallic polyoxotitanium clusters for the efficient and selective photocatalytic oxidation of hydrocarbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202215540 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Y. Chen, C. Zou, M. Mastalerz, S. Hu, C. Gasaway, X. Tao, Applications of micro-Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) in the geological sciences—A review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 30223–30250 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.C. M. Pichler, S. Bhattacharjee, E. Lam, L. Su, A. Collauto, M. M. Roessler, S. J. Cobb, V. M. Badiani, M. Rahaman, E. Reisner, Bio-electrocatalytic conversion of food waste to ethylene via succinic acid as the central intermediate. ACS Catal. 12, 13360–13371 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.L. M. Betts, F. Dappozze, C. Guillard, Understanding the photocatalytic degradation by P25 TiO2 of acetic acid and propionic acid in the pursuit of alkane production. Appl. Catal. A. Gen. 554, 35–43 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Y. Nosaka, A. Y. Nosaka, Generation and detection of reactive oxygen species in photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 117, 11302–11336 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.S. Zhang, H. Li, L. Wang, J. Liu, G. Liang, K. Davey, J. Ran, S.-Z. Qiao, Boosted photoreforming of plastic waste via defect-rich NiPS3 nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6410–6419 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.D. Ma, S. Zhai, Y. Wang, A. Liu, C. Chen, TiO2 photocatalysis for transfer hydrogenation. Molecules 24, 330 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.J. M. Ferreira Jr., G. F. Trindade, R. Tshulu, J. F. Watts, M. A. Baker, Dicarboxylic acids analysed by x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, Part II—Butanedioic acid anhydrous. Surf. Sci. Spectra 24, 011102 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 69.B.-H. Lee, S. Park, M. Kim, A. K. Sinha, S. C. Lee, E. Jung, W. J. Chang, K.-S. Lee, J. H. Kim, S.-P. Cho, H. Kim, K. T. Nam, T. Hyeon, Reversible and cooperative photoactivation of single-atom Cu/TiO2 photocatalysts. Nat. Mater. 18, 620–626 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.X. Sun, J. Chen, T. Ritter, Catalytic dehydrogenative decarboxyolefination of carboxylic acids. Nat. Chem. 10, 1229–1233 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.C. Kang, L. Jing, T. Guo, H. Cui, J. Zhou, H. Fu, Mesoporous SiO2-modified nanocrystalline TiO2 with high anatase thermal stability and large surface area as efficient photocatalyst. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 1006–1013 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 72.R. Bagri, P. T. Williams, Catalytic pyrolysis of polyethylene. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 63, 29–41 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 73.M. Artetxe, G. Lopez, M. Amutio, G. Elordi, J. Bilbao, M. Olazar, Cracking of high density polyethylene pyrolysis waxes on HZSM-5 catalysts of different acidity. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52, 10637–10645 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 74.F. Ateş, N. Miskolczi, N. Borsodi, Comparision of real waste (MSW and MPW) pyrolysis in batch reactor over different catalysts. Part I: Product yields, gas and pyrolysis oil properties. Bioresour. Technol. 133, 443–454 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.N. Lee, J. Joo, K.-Y. A. Lin, J. Lee, Waste-to-fuels: Pyrolysis of low-density polyethylene waste in the presence of H-ZSM-11. Polymers 13, 1198 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.M. Kusenberg, M. Roosen, A. Zayoud, M. R. Djokic, H. D. Thi, S. D. Meester, K. Ragaert, U. Kresovic, K. M. V. Geem, Assessing the feasibility of chemical recycling via steam cracking of untreated plastic waste pyrolysis oils: Feedstock impurities, product yields and coke formation. Waste Manag. 141, 104–114 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.I. I. Ahmed, N. Nipattummakul, A. K. Gupta, Characteristics of syngas from co-gasification of polyethylene and woodchips. Appl. Energy 88, 165–174 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 78.A. Eschenbacher, F. Goodarzi, R. J. Varghese, K. Enemark-Rasmussen, S. Kegnæs, M. S. Abbas-Abadi, K. M. V. Geem, Boron-modified mesoporous ZSM-5 for the conversion of pyrolysis vapors from LDPE and mixed polyolefins: Maximizing the C2–C4 olefin yield with minimal carbon footprint. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 9, 14618–14630 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 79.W. Kaminsky, B. Schlesselmann, C. Simon, Olefins from polyolefins and mixed plastics by pyrolysis. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 32, 19–27 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 80.E. Bäckström, K. Odelius, M. Hakkarainen, Trash to treasure: Microwave-assisted conversion of polyethylene to functional chemicals. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 56, 14814–14821 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 81.T. Uekert, H. Kasap, E. Reisner, Photoreforming of nonrecyclable plastic waste over a carbon nitride/nickel phosphide catalyst. J. Am. Soc. Chem. 141, 15201–15210 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.J. Xu, X. Jiao, K. Zheng, W. Shao, S. Zhu, X. Li, J. Zhu, Y. Pan, Y. Sun, Y. Xie, Plastics-to-syngas photocatalysed by Co-Ga2O3 nanosheets. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, nwac011 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Z. Huang, M. Shanmugam, Z. Liu, A. Brookfield, E. L. Bennett, R. Guan, D. E. Vega Herrera, J. A. Lopez-Sanchez, A. G. Slater, E. J. L. Mclnnes, X. Qi, J. Xiao, Chemical recycling of polystyrene to valuable chemicals via selective acid-catalyzed aerobic oxidation under visible light. J. Am. Soc. Chem. 144, 6532–6542 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.J. Qin, Y. Dou, J. Zhou, V. M. Candelario, H. R. Andersen, C. Helix-Nielsen, W. Zhang, Photocatalytic valorization of plastic waste over zinc oxide encapsulated in a metal-organic framework. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2214839 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 85.J. Ye, Y. Chen, C. Gao, C. Wang, A. Hu, G. Dong, Z. Chen, S. Zhou, Y. Xiong, Sustainable conversion of microplastics to methane with ultrahigh selectivity by a biotic-abiotic hybrid photocatalytic system. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202213244 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.R. Cao, M.-Q. Zhang, C. Hu, D. Xiao, M. Wang, D. Ma, Catalytic oxidation of polystyrene to aromatic oxygenates over a graphitic carbon nitride catalyst. Nat. Commun. 13, 4809 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Y. Liu, X. Wang, Q. Li, T. Yan, X. Lou, C. Zhang, M. Cao, L. Zhang, T.-K. Sham, Q. Zhang, L. He, J. Chen, Photothermal catalytic polyester upcycling over cobalt single-site catalyst. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2210283 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 88.S. Bhattacharjee, V. Andrei, C. Pornrungroj, M. Rahaman, C. M. Pichler, E. Reisner, Reforming of soluble biomass and plastic derived waste using a bias-free Cu30Pd70|perovskite|Pt photoelectrochemical device. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109313 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 89.C.-Y. Lin, S.-C. Huang, Y.-G. Lin, L.-C. Hsu, C.-T. Yi, Electrosynthesized Ni-P nanospheres with high activity and selectivity towards photoelectrochemical plastics reforming. Appl Catal B 296, 120351 (2021). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S18

Tables S1 to S10

References