Abstract

Ω4400 is the site of a Tn5 lac insertion in the Myxococcus xanthus genome that fuses lacZ expression to a developmentally regulated promoter. Cell-cell interactions that occur during development, including C signaling, are required for normal expression of Tn5 lac Ω4400. The DNA upstream of the Ω4400 insertion has been cloned, the promoter has been localized, and a partial open reading frame has been identified. From the deduced amino acid sequence of the partial open reading frame, the gene disrupted by Tn5 lac Ω4400 may encode a protein with an ATP- or GTP-binding site. Expression of the gene begins 6 to 12 h after starvation initiates development, as measured by β-galactosidase production in cells containing Tn5 lac Ω4400. The putative transcriptional start site was mapped, and deletion analysis has shown that DNA downstream of −101 bp is sufficient for C-signal-dependent, developmental activation of this promoter. A deletion to −76 bp eliminated promoter activity, suggesting the involvement of an upstream activator protein. The promoter may be transcribed by RNA polymerase containing a novel sigma factor, since a mutation in the M. xanthus sigB or sigC gene did not affect Tn5 lac Ω4400 expression and the DNA sequence upstream of the transcriptional start site did not match the sequence of any M. xanthus promoter transcribed by a known form of RNA polymerase. However, the Ω4400 promoter does contain the sequence 5′-CATCCCT-3′ centered at −49 and the C-signal-dependent Ω4403 promoter also contains this sequence at the same position. Moreover, the two promoters match at five of six positions in the −10 regions, suggesting that these promoters may share one or more transcription factors. These results begin to define the cis-acting regulatory elements important for cell-cell interaction-dependent gene expression during the development of a multicellular prokaryote.

Cell-cell interactions play a critical role in cellular differentiation in most multicellular organisms. The gram-negative bacterium Myxococcus xanthus undergoes multicellular development and differentiation in response to cell-cell interactions (10). Upon starvation at a high cell density on a solid surface, undifferentiated, rod-shaped cells move in a coordinated fashion into aggregation centers, where they build a mound-shaped fruiting body containing approximately 105 cells. Some cells within a nascent fruiting body differentiate into dormant, ovoid spores that are resistant to heat and desiccation.

The processes of development and differentiation in M. xanthus are controlled by a program of gene expression which is highly coordinated in response to cell-cell interactions (27). At least five cell-cell signals are required for normal development. Mutants unable to produce any one of these signals are arrested in their development but can develop when mixed with either wild-type cells or cells that are defective in the production of a different signal (8, 19, 35). C-signaling mutants are one class of such developmental signaling mutants. All existing members of the C-signaling class have resulted from mutations in a single gene called csgA and are defective in both fruiting body formation and sporulation (20, 51, 52). Mutations in csgA also block rippling, the synchronous movement of waves of developing cells (46, 53). CsgA appears to mediate C signaling by acting as a developmental timer that, at successively higher concentrations, triggers the normal developmental sequence of rippling, aggregation, fruiting body formation, and sporulation (31, 37). Different levels of C signaling are also necessary to trigger the expression of different developmental genes (31).

Sixteen C-dependent genes have been identified by using a transposon, Tn5 lac, that contains a promoterless lacZ gene near one end (32–34). Transposition of Tn5 lac into the M. xanthus chromosome can generate a transcriptional fusion between lacZ and an M. xanthus promoter. Tn5 lac insertions in C-dependent genes were identified as insertions whose lacZ expression was increased during the development of wild-type cells, but expression was delayed, reduced, or abolished in a csgA mutant background (33). Nearly all genes that begin to be expressed after 6 h into development appear to be at least partially C dependent.

To begin to understand how C signaling regulates M. xanthus developmental gene expression, the DNA regulatory regions of C-signal-dependent genes must be characterized. This report describes the cloning and initial characterization of the regulatory region controlling the transcriptional unit identified by the insertion of Tn5 lac at site Ω4400 in the M. xanthus chromosome (34). Expression of Tn5 lac Ω4400 begins 6 to 12 h into development and is partially dependent on C signaling (33). Deletions were generated to localize the sequences required for promoter activity, the nucleotide sequence of the promoter region was determined and compared to those of other M. xanthus developmental promoters, and the transcriptional start site was mapped. Activity of the minimal promoter was reduced in csgA mutant cells, but normal expression was restored upon codevelopment with wild-type cells, indicating that the cloned promoter retains its partial dependence upon extracellular C signaling. Promoter activity required sequences relatively far upstream of the transcriptional start site, implying that a regulatory protein(s) in addition to RNA polymerase is involved in promoter activation. Comparison of the Tn5 lac Ω4400 promoter to that of the absolutely C-dependent Tn5 lac Ω4403 insertion (14) revealed features common to these genes which might lead to the identification of regulatory proteins involved in the activation of these genes in response to C signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

Table 1 contains a list of the strains and plasmids used in this work.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| DH5α | φ80 ΔlacZΔM15 ΔlacU169 recA1 endA1 hsdR17 supE44 thi-1 gyrA relA1 | 21 |

| JM83 | ara Δlac-pro strA thi φdlacZΔM15 | 41 |

| RL937 | SF800 (P1::Tn5 lac-tet) | 36 |

| M. xanthus | ||

| DK1622 | Wild type | 25 |

| DK4292 | Tn5 lac (Kmr) Ω4400 | 34 |

| MMF1727 | attB::pREG1727 | 14 |

| JPB4000 | attB::pJB4000 | This work |

| JPB4003 | attB::pJB4003 | This work |

| JPB4004 | attB::pJB4004 | This work |

| JPB40018 | attB::pJB40018 | This work |

| JPB40019 | attB::pJB40019 | This work |

| JPB40020 | attB::pJB40020 | This work |

| JPB40013 | attB::pJB40027 | This work |

| DK5208 | csgA::Tn5-132 (Tcr) Ω205 | 51 |

| DK5247 | csgA::Tn5-132 (Tcr) Ω205 Tn5 lac (Kmr) Ω4400 | 33 |

| JPB03 | csgA::Tn5-132 (Tcr) Ω205 attB::pREG1727 | This work |

| JPB4006 | csgA::Tn5-132 (Tcr) Ω205 attB::pJB4000 | This work |

| JPB4007 | csgA::Tn5-132 (Tcr) Ω205 attB::pJB4004 | This work |

| JPB4008 | csgA::Tn5-132 (Tcr) Ω205 attB::pJB4003 | This work |

| JPB40010 | csgA::Tn5-132 (Tcr) Ω205 attB::pJB40018 | This work |

| JPB40011 | csgA::Tn5-132 (Tcr) Ω205 attB::pJB40019 | This work |

| JPB40012 | csgA::Tn5-132 (Tcr) Ω205 attB::pJB40020 | This work |

| ΔsigB | ΔsigB (Kmr) | 1 |

| ΔsigC-1 | ΔsigC-1 (Kmr) | 2 |

| JBP05 | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4400 | This work |

| JPB05B | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4400 ΔsigB (Kmr) | This work |

| JPB05C | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4400 ΔsigC-1 (Kmr) | This work |

| DK4459 | Tn5 lac (Kmr) Ω4459 | 34 |

| JPB06 | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4459 | This work |

| JPB06B | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4459 ΔsigB (Kmr) | This work |

| JPB06C | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4459 ΔsigC-1 (Kmr) | This work |

| DK4368 | Tn5 lac (Kmr) Ω4403 | 34 |

| JPB07 | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4403 | This work |

| JPB07B | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4403 ΔsigB (Kmr) | This work |

| JPB07C | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4403 ΔsigC-1 (Kmr) | This work |

| DK4499 | Tn5 lac (Kmr) Ω4499 | 34 |

| JPB08 | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4499 | This work |

| JPB08B | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4499 ΔsigB (Kmr) | This work |

| JPB08C | Tn5 lac (Tcr) Ω4499 ΔsigC-1 (Kmr) | This work |

| Plasmids | ||

| pGEM7Zf | Aprlacα | Promega |

| pJB4400 | Apr Kmr (pGEM7Zf)a; 10.8-kb XhoI fragment from DK4292 | This work |

| pJB4001 | Apr (pGEM7Zf); 1.1-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragment from pJB4400 | This work |

| pJB40012 | Apr (pGEM7Zf); 0.4-kb SmaI-BamHI fragment from pJB4400 | This work |

| pJB40015 | Apr (pGEM7Zf); 0.64-kb ApaLI-BamHI fragment from pJB4001 | This work |

| pJB40016 | Apr (pGEM7Zf); 0.59-kb BstXI-BamHI fragment from pJB4001 | This work |

| pJB40017 | Apr (pGEM7Zf); 0.56-kb SphI-BamHI fragment from pJB4001 | This work |

| pJB40025 | Apr (pJB4001); 0.23-kb HindIII-SmaI fragment generated by PCR of pJB4001 | This work |

| pREG1727 | Apr Kmr P1-inc attP ′lacZ | 14 |

| pJB4000 | Apr Kmr (pREG1727); 1.8-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment from pJB4400 | This work |

| pJB4003 | Apr Kmr (pREG1727); 1.1-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragment from pJB4001 | This work |

| pJB4004 | Apr Kmr (pREG1727); 0.4-kb SmaI-BamHI fragment from pJB40012 | This work |

| pJB40018 | Apr Kmr (pREG1727); 0.66-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment from pJB40015 | This work |

| pJB40019 | Apr Kmr (pREG1727); 0.61-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment from pJB40016 | This work |

| pJB40020 | Apr Kmr (pREG1727); 0.58-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment from pJB40017 | This work |

| pJB40027 | Apr Kmr (pREG1727); 0.64-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment from pJB40025 | This work |

The vector is indicated in parentheses.

Bacterial growth and development.

Escherichia coli cells were grown at 37°C in LB medium (47) containing 50 μg of ampicillin, 40 μg of kanamycin (KM), or 10 μg of tetracycline per ml, as necessary. M. xanthus was grown at 32°C in CTT medium (23) with 40 μg of KM or 12.5 μg of oxytetracycline (oxyTC) per ml when required. TPM starvation agar was used to induce fruiting body development (34).

Molecular cloning.

To clone the DNA upstream of Tn5 lac Ω4400, chromosomal DNA was prepared (36) from DK4292 (Table 1) and digested with XhoI. Standard techniques were used for this and all subsequent molecular cloning work (47). The chromosomal DNA fragments were ligated to XhoI-digested pGEM7Zf, and the mixture was transformed into E. coli DH5α, selecting for resistance to ampicillin and KM. One Apr Kmr transformant containing a plasmid with an insert of the predicted size was characterized further. Restriction fragments of M. xanthus DNA from this plasmid, pJB4400, were gel purified and ligated into vectors as indicated in Table 1. In these and the subsequent subcloning steps described in Table 1, vectors were digested with the same restriction enzymes used to produce the fragments, except as indicated below.

Plasmids pJB40015, pJB40016, and pJB40017 were constructed by digestion of pJB4001 with ApaLI, BstXI, and SphI, respectively. The ApaLI ends were filled in by using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I. The BstXI and SphI ends were made blunt by digestion with mung bean nuclease. After digestion with BamHI and gel purification, the resulting fragments were subcloned into SmaI-BamHI-digested pGEM7Zf. From these plasmids, XhoI-BamHI fragments were recovered for subcloning into pREG1727 (Table 1).

To generate the promoter deletion to the −76 position, plasmid pJB40025 was constructed. A fragment of Ω4400 upstream DNA was generated by PCR by using pJB4001 as a template. The downstream primer was 5′-CCGCCAGCCCCATCAGC-3′, which binds to the Ω4400 region downstream of the SmaI site, and the upstream primer was 5′-CTTAAGCTTTGCGGTGGTGGGGAGCGAACA-3′, which binds between 612 and 594 bp upstream of the Ω4400 insertion site (primers were synthesized by the Michigan State University Macromolecular Structure Facility). The underlined HindIII site near the 5′ end of the upstream primer was included to facilitate subcloning. The amplified fragment was digested with SmaI and HindIII, gel purified, and ligated to the 4.4-kb EcoRI-SmaI-digested pJB4001 fragment. The HindIII and EcoRI ends were filled in by using the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I and ligated to generate pJB40025. The insert was sequenced to ensure that no replication errors occurred during the PCR.

DNA sequencing.

Plasmids pJB4001, pJB40012, and pJB40015 were used as double-stranded templates in sequencing reactions performed by the method of Sanger et al. (48) with either the dGTP or the 7-deaza-dGTP Sequenase kit (United States Biochemical(. When the gGTP kit was used, terminal deoxynucleotide transferase reactions were performed prior to termination of the sequencing reactions to eliminate ambiguities due to premature termination (13). The University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group software package was used to analyze the sequencing results. The Michigan State University Macromolecular Structure Facility synthesized oligonucleotide primers as needed to sequence both strands of the 1.1-kb Ω4400 upstream DNA.

Construction of M. xanthus strains.

Strains containing pREG1727 derivatives integrated at Mx8 attB were constructed as described previously (14, 16). At least three transductants containing a single copy of the plasmid integrated at Mx8 attB were identified by Southern blot analysis (14, 47), and their β-galactosidase production was measured under developmental conditions (34).

The Tn5 lac (Tcr) strains were constructed by transduction of the appropriate M. xanthus strains containing Tn5 lac (Kmr) with P1::Tn5 lac-tet (Tcr) (a gift from R. Gill). Transductants were plated on CTT containing oxyTC (2.5 μg/ml) and incubated overnight at 30°C (3). The next day, the oxyTC concentration in the plates was increased to 12.5 μg/ml (3). Tcr transductants were picked to CTT-oxyTC-KM to confirm their KM sensitivity. Southern blot analysis was performed to confirm that Tn5 lac (Kmr) had been replaced by Tn5 lac (Tcr): the 6-kb BamHI-StuI fragment of pREG1727 was labeled with digoxigenin (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals) and hybridized to EcoRI-XhoI-digested chromosomal DNA. Two chromosomal DNA fragments hybridize to this probe. One fragment extends from the EcoRI site within the lacZ gene of Tn5 lac to the EcoRI site of the tet gene (4.5 kb) (3) and/or to the XhoI site of the aphII gene (5.4 kb) (32), and the presence of only the 4.5-kb hybridizing fragment is indicative of the replacement by double crossover. The other fragment extends from the EcoRI site within lacZ to the first chromosomal EcoRI or XhoI site upstream of the Tn5 lac insertion and is diagnostic of the proper chromosomal position of the Tn5 lac insertion. Developmental β-galactosidase assays (34) were performed on three positive isolates of each replacement strain.

To introduce the ΔsigB and ΔsigC-1 mutations into the Tn5 lac (Tcr)-containing strains, Mx4 transducing phage stocks (7, 15, 26) were prepared on strains ΔsigB (1) and ΔsigC-1 (2). The Tn5 lac (Tcr)-containing strains (∼108 cells) were mixed with phage at multiplicities of infection of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0, and transductants were selected on CTT-oxyTC-KM plates.

RNA analysis.

M. xanthus RNA was prepared as described previously (14). To perform S1 nuclease protection assays, pJB4001 was digested with either BamHI or SmaI, phosphatase treated, 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP and T4 polynucleotide kinase, and digested with EcoRI. The labeled 1.1-kb EcoRI-BamHI and 0.5-kb EcoRI-SmaI fragments were gel purified and used as probes. The denatured probes were hybridized to 50 μg of RNA, and the DNA-RNA hybrid was digested with 25 or 50 U of S1 nuclease to map the 5′ end of the Ω4400-associated transcript as previously described (14).

Primer extension analysis was performed by using 30 and 60 μg of RNA. The oligonucleotide (Michigan State University Macromolecular Structure Facility) used in the primer extension analysis was end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and [γ-32P]ATP and purified by using a Qiaquick column as recommended by the manufacturer (Qiagen). Primer extension reactions were performed as previously described (14, 47) with the addition of 2.5 U of RNasin (Promega) during the extension reaction.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the region upstream of the Ω4400 Tn5 lac insertion (see Fig. 4) has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF026951.

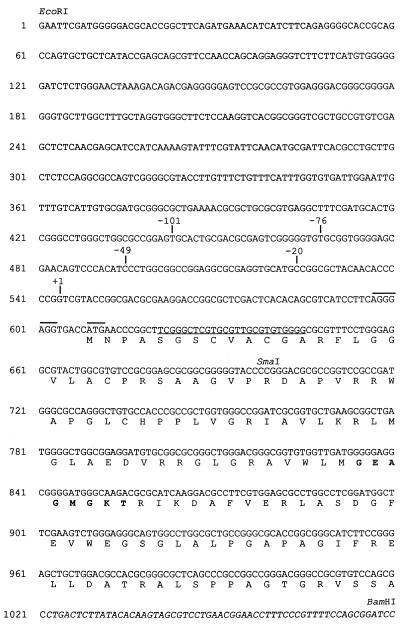

FIG. 4.

Nucleotide sequence of the region upstream of the Ω4400 Tn5 lac insertion. The transcriptional start site is indicated by +1, and the primer used for the primer extension analysis is underlined. The putative translational start codon and a potential ribosome-binding site are overlined. The deduced amino acid sequence of the Ω4400 partial ORF is shown below the nucleotide sequence, and the amino acids comprising the putative ATP- or GTP-binding site motif are in boldface type. The sequence from the end of Tn5 lac to the BamHI site within Tn5 lac is in italics. Restriction sites and important deletion sites are also indicated.

RESULTS

Localization of the developmental promoter controlling Ω4400 expression.

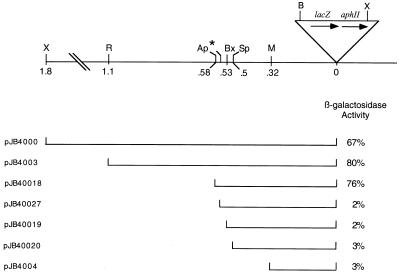

To clone the putative promoter located upstream of the developmentally regulated Tn5 lac insertion Ω4400, we took advantage of an XhoI restriction site approximately 1.8 kb upstream of the Ω4400 insertion in M. xanthus DK4292 (34) and an XhoI site in Tn5 lac approximately 9 kb from the left end (Fig. 1). Chromosomal DNA from DK4292 was digested with XhoI, cloned into pGEM7Zf, and transformed into E. coli cells. Since the 10.8-kb XhoI fragment described above includes the aphII gene of Tn5 lac, which encodes aminoglycoside phosphotransferase and confers Kmr, E. coli cells that contain plasmids with the desired XhoI fragment of M. xanthus chromosomal DNA will survive under KM selection. Several restriction sites upstream of the Ω4400 insertion in DK4292 have been mapped by Kroos et al. (34). Restriction mapping of pJB4400, the plasmid containing the 10.8-kb XhoI fragment of M. xanthus DNA, showed that the insert displayed the pattern predicted on the basis of these data, as well as the known restriction maps of pGEM7Zf and Tn5 lac. The restriction map of DNA upstream of the Ω4400 insertion is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Physical map of the Ω4400 insertion region and summary of deletions tested for promoter activity. The upper schematic depicts the restriction sites in Tn5 lac and the upstream M. xanthus chromosome that were used in this study. The position of the 5′ end of the oligonucleotide used to construct the PCR-generated deletion fragment is also indicated (∗). Distances of restriction sites from the Tn5 lac Ω4400 insertion are given in kilobases. Ap, ApaLI; B, BamHI; Bx, BstXI; M, SmaI; R, EcoRI; Sp, SphI; X, XhoI. The lower diagram depicts the segments of Ω4400 upstream DNA fused to the promoterless lacZ gene of pREG1727 to test for promoter activity. The plasmid designation is indicated on the left (Table 1). The maximum β-galactosidase specific activities during a 48- to 72-h developmental time course of derivatives of wild-type M. xanthus DK1622 containing a single copy of each plasmid integrated at Mx8 attB are given as percentages of the maximum activity observed for Tn5 lac Ω4400-containing strain DK4292. In each case, the activity of at least three independent transductants was measured at least once as described previously (34) and the average is given.

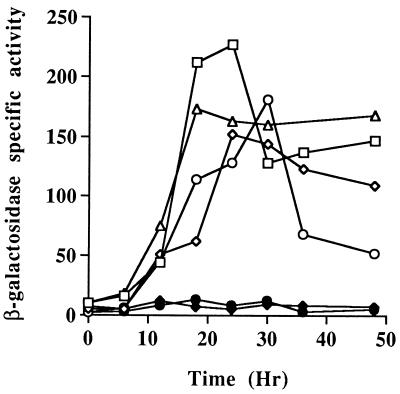

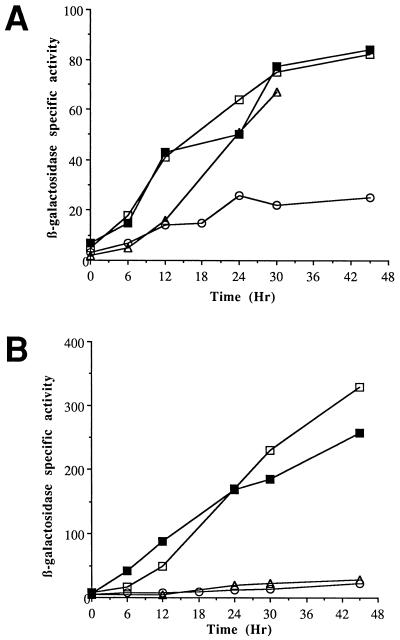

To test the cloned 1.8 kb of DNA upstream of Ω4400 for promoter activity, the XhoI-BamHI restriction fragment from pJB4400, which contains 1.8 kb of M. xanthus DNA and approximately 60 bp of the left end of Tn5 lac (Fig. 1), was subcloned into XhoI-BamHI-digested pREG1727 to construct pJB4000. The BamHI site of pREG1727 is located immediately upstream of the same lacZ-containing fragment found in Tn5 lac, so pJB4000 contains Ω4400 upstream DNA fused to a promoterless lacZ gene in the same manner as Ω4400-containing M. xanthus DK4292. The pREG1727 promoter testing vector includes the attP gene of myxophage Mx8 (14), which allows site-specific integration of this plasmid at the Mx8 phage attachment site of the M. xanthus chromosome (Mx8 attB) (55, 56). P1 specialized transduction (16) was used to transduce pJB4000 from E. coli JM83 into wild-type M. xanthus DK1622. Transductants containing a single copy of pJB4000 integrated at Mx8 attB were identified by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Five of the positive isolates were analyzed for developmental production of β-galactosidase. The developmental β-galactosidase activity in these strains was compared to that of DK4292, the original Ω4400 insertion-containing strain, and to MMF1727, a negative control in which pREG1727 (with no M. xanthus DNA insert) was integrated at the attB site. Transductants containing a single copy of pJB4000 integrated at the attB site produced β-galactosidase with a timing similar to that of the original Ω4400-containing insertion strain (Fig. 2). The average β-galactosidase activity in the pJB4000 integrants reached 67% of the maximal level observed in DK4292 (Fig. 1 and 2). The results indicate that the 1.8-kb Ω4400 upstream DNA segment contains a promoter that is able to direct development-specific expression.

FIG. 2.

Developmental expression of lacZ under the control of the Ω4400 promoter. Developmental β-galactosidase specific activity was measured as described previously (34) for Tn5 lac-containing strain DK4292 (□) and for at least three independently isolated transductants of DK1622 containing a single copy of the 1.8-kb (◊), 1.1-kb (○), 0.64-kb (▵), or 0.4-kb (⧫) Ω4400 upstream DNA fused to promoterless lacZ within pREG1727 and integrated at Mx8 attB. The β-galactosidase specific activity of DK1622 containing the pREG1727 vector alone with no insert integrated at Mx8 attB (•) is also shown. The average β-galactosidase activity from six determinations for DK4292 or from at least one determination for each of three independent transductants is plotted. β-Galactosidase specific activity is expressed in nanomoles of o-nitrophenyl phosphate per minute per milligram of protein.

To further localize the developmental promoter within this region, additional deletions of the Ω4400 upstream DNA were generated and tested for promoter activity as described above. Transductants containing the 1.1-kb EcoRI-BamHI restriction fragment (Fig. 1) cloned into pREG1727 and integrated at the attB site had development-specific lacZ expression similar to that of the 1.8-kb XhoI-BamHI fragment (Fig. 1 and 2), but transductants containing the 0.4-kb SmaI-BamHI restriction fragment produced no developmental β-galactosidase above the background (Fig. 1 and 2). These results suggest that the development-specific promoter driving the expression of Tn5 lac Ω4400 may be located within the 0.7-kb EcoRI-SmaI restriction fragment upstream of the insertion.

Localization of an mRNA 5′ end upstream of Ω4400.

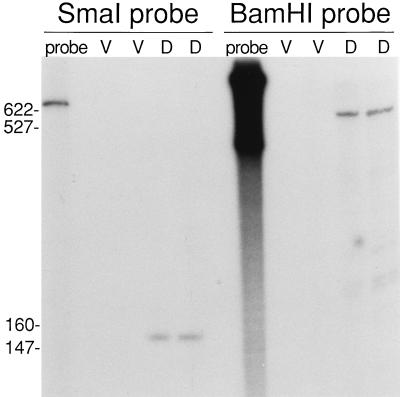

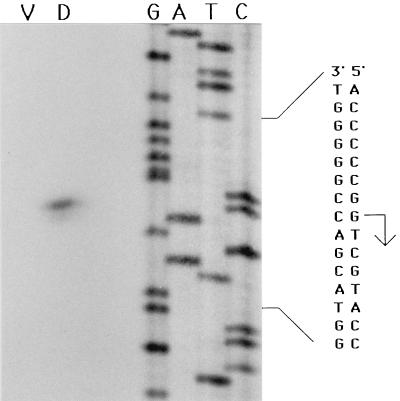

To test whether an mRNA 5′ end maps within the 0.7-kb EcoRI-SmaI region upstream of the Ω4400 insertion, S1 nuclease protection assays were performed (Fig. 3). Probes labeled at the SmaI site upstream of Ω4400 and the BamHI site near the left end of Tn5 lac (Fig. 1) were hybridized to RNA from DK4292 and subjected to S1 nuclease protection analysis. When hybridized to RNA prepared from cells that had undergone 24 h of development, the probe labeled at the SmaI site protected a single RNA species approximately 150 bases in length (Fig. 3). The probe labeled at the BamHI site protected a developmental RNA species approximately 550 bases in length (Fig. 3). No protection was detected when S1 nuclease protection assays were conducted by using RNA prepared from growing cells (Fig. 3). Together, these data indicate that a single, development-specific mRNA is transcribed from the region upstream of the Ω4400 Tn5 lac insertion and the 5′ end of this mRNA species is located approximately 150 bp upstream of the SmaI site in this region. The SmaI-labeled probe was also hybridized to mRNA prepared from developing wild-type DK1622 cells and was shown to protect an RNA species approximately 150 bases in length in this strain as well (data not shown), suggesting that transcription of the fusion mRNA in DK4292 and the native mRNA in DK1622 initiates at the same site.

FIG. 3.

Localization of a single mRNA 5′ end within the Ω4400 upstream region. Low-resolution S1 nuclease mapping of the Ω4400-associated transcript was performed by using RNA prepared from DK4292 cells grown vegetatively (lanes V) or cells that had undergone 24 h of development (lanes D). The RNA was hybridized to DNA probes that were radioactively labeled at either the SmaI site upstream of Ω4400 or the BamHI site near the left end of Tn5 lac prior to digestion by 25 U (left lanes of each set) or 50 U (right lanes) of S1 nuclease. The lengths (in base pairs) of some of the end-labeled, MspI-digested pBR322 molecular size standard fragments are indicated on the left.

DNA sequence of the Ω4400 upstream region.

The nucleotide sequence of both strands of the 1.1-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragment immediately upstream of the Ω4400 insertion site was determined (Fig. 4). An open reading frame (ORF) beginning with the ATG at position 609 is preceded 5 bp upstream by the sequence 5′-AGGGAGG-3′, which might serve as a ribosome-binding site since it is complementary (except for one mismatch) to a sequence near the 3′ end of M. xanthus 16S rRNA (43). The codon preference within the ORF is similar to that of other sequenced M. xanthus genes and exhibits a strong bias towards the presence of a guanine or cytosine at the third codon position (50). The left end of the Tn5 lac used to generate the Ω4400 insertion contains translational stop codons in all three reading frames (34), and the ORF continues uninterrupted to one of these stop codons within Tn5 lac. The deduced 138-amino-acid sequence of the partial ORF was analyzed by the Motifs program (Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group sequence analysis software) and shown to contain an ATP- or GTP-binding site motif (A consensus sequence or P loop), suggesting that the protein product of this ORF binds ATP or GTP (49, 58). The P loop, a glycine-rich region, interacts with one of the phosphate groups of the nucleotide. Analysis of the deduced amino acid sequence by the BLAST program supports this observation: the partial ORF exhibits 41% amino acid identity and 57% amino acid similarity over a 44-amino-acid stretch to the E. coli arsenical pump-driving ATPase (45). The 44-amino-acid region of alignment includes the P-loop consensus sequence Gn4GKT (Fig. 4) (49, 58). These analyses suggest that Tn5 lac Ω4400 disrupts the first or only gene in a developmentally regulated transcriptional unit and this gene encodes a protein that binds ATP or GTP. The function of this putative nucleotide-binding protein is not known because the ability of M. xanthus cells to grow and develop is not affected by the Ω4400 Tn5 lac insertion.

Precise localization of the Ω4400 mRNA 5′ end.

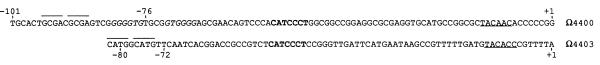

The DNA sequence analysis and the S1 nuclease protection assay results facilitated the design of a primer for precise mapping of the location of the Ω4400 mRNA 5′ end by primer extension analysis. The position of the primer is shown in Fig. 4; however, the actual primer contains a sequence complementary to that underlined. When primer extension analysis was performed by using RNA purified from DK1622 cells that had undergone 24 h of development, a single primer extension product was identified (Fig. 5). This localizes the mRNA 5′ end to a guanine nucleotide on the coding strand at position 544 in the sequence (Fig. 4 and 5). The mRNA 5′ end is 531 bp upstream of the BamHI site near the left end of Tn5 lac and 153 bp upstream of the SmaI site in the region upstream of the Ω4400 insertion (Fig. 1), which is in agreement with the S1 nuclease protection results (Fig. 3). No primer extension product was generated when mRNA prepared from growing cells was subjected to primer extension analysis (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

Primer extension analysis of Ω4400 mRNA. RNA was isolated from wild-type cells grown vegetatively (lane V) or cells that had undergone 24 h of development (lane D), and 60 μg was subjected to primer extension analysis. The same primer was used to sequence Ω4400 upstream DNA. A portion of the DNA sequence is indicated at the right. The arrow indicates the putative transcriptional start site as determined by the migrational position of the single primer extension product detected by using developmental RNA samples.

Further deletion analysis of the Ω4400 upstream region and comparison to known M. xanthus promoters.

Smaller fragments of DNA upstream of the Ω4400 insertion were tested for promoter activity in vivo to further define the sequences required for developmental promoter activity. The DNA sequence analysis identified three unique restriction sites in the Ω4400 upstream region of interest. The ApaLI, BstXI, and SphI sites allowed the construction of 5′ deletions to 101, 49, and 20 bp, respectively, upstream of the putative transcriptional start site (Fig. 1). A fourth fragment was generated by PCR to create a 5′ deletion to −76 bp (Fig. 1). Each fragment was inserted into the pREG1727 promoter testing vector, and M. xanthus strains with a single copy of the plasmid integrated at the chromosomal attB site were tested for developmental β-galactosidase activity. Only the construct containing 101 bp of DNA upstream of the putative transcriptional start site synthesized β-galactosidase at levels and with timing similar to those of DK4292 (Fig. 2). Developmental β-galactosidase activity was completely abolished in the other three constructs (Fig. 1). These results demonstrate that a promoter does exist in this region and that 101 bp of DNA upstream of the transcriptional start site is sufficient for the developmentally regulated expression of lacZ at levels comparable to those of the original Ω4400 insertion-containing strain, DK4292. Additionally, these results show that the DNA between 101 and 76 bp upstream of the start site of transcription is necessary for the activity of this developmental promoter.

DNA sequences in the Ω4400 promoter region bear some resemblance to those in the Ω4403 promoter region (14) (Fig. 6). Like Ω4400, Ω4403 is the site of an M. xanthus chromosomal Tn5 lac insertion that disrupts a developmentally regulated gene. In the −10 regions of both promoters, hexanucleotide sequences matching in five positions are present. The −35 regions of the two promoters are not similar; however, the −50 regions of both promoters contain the sequence 5′-CATCCCT-3′. The conserved sequences in the −10 and −50 regions suggest that the Ω4400 and Ω4403 promoters share one or more transcription factors. DNA between −80 and −72 is essential for Ω4403 promoter activity, yet comparison of this sequence to the critical −101 to −76 region of the Ω4400 promoter revealed no more than three consecutive nucleotides that match, suggesting that the two promoters require different upstream activator proteins. Figure 6 also shows that short repeat sequences are present in the critical upstream regions of both promoters, but the repeat sequences are different for the two promoters. The DNA sequence of the Ω4400 promoter region is not similar to that of any other known bacterial promoters, including developmental M. xanthus promoters (9, 18, 29, 37, 42, 44).

FIG. 6.

Alignment of Ω4403 (14) and Ω4400 promoter DNA sequences. The sequences have been aligned at their respective +1 positions. The 7 bp of identical sequence in the −50 region is in boldface type, and the similar −10 sequences are underlined. Short repeat sequences in the critical upstream regions are overlined, and a 6-bp mirror repeat in the Ω4400 upstream region is italicized.

Dependence of the Ω4400 promoter on csgA and rescue by extracellular C signaling.

The csgA gene is absolutely required for intercellular C signaling in wild-type cells (20, 51, 52), and the csgA gene product somehow mediates the expression of nearly all M. xanthus genes that begin to be expressed after approximately 6 h into development (33). When Kroos et al. (33) transduced a csgA mutation into cells containing the Ω4400 Tn5 lac insertion, developmental lacZ expression was delayed so that it reached only about half the level of expression in wild-type cells at the time of wild-type peak activity.

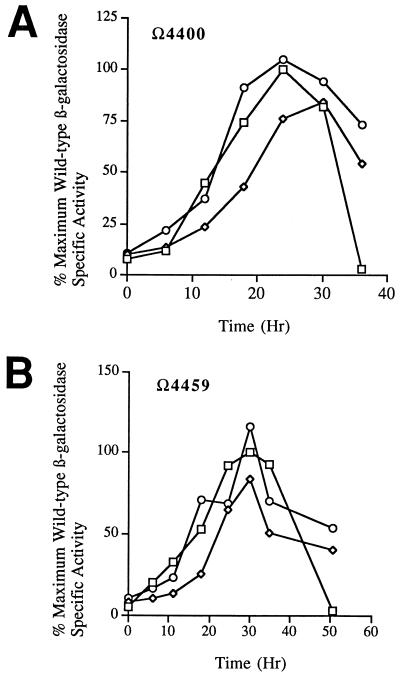

To determine whether the cloned promoter exhibited similar dependence upon csgA, the pREG1727 constructs described above were transduced into a csgA mutant strain. Developmental β-galactosidase activity was measured in strains containing a single copy of the Ω4400 promoter fused to lacZ and integrated at the Mx8 attB site. Strain DK5247 contains the Ω4400 Tn5 lac insertion in a csgA mutant background. Developmental lacZ expression in this strain is reduced about two- to threefold in comparison with Ω4400 Tn5 lac expression in a wild-type background (Fig. 2 and 7A). csgA cells containing pREG1727 with the −101 promoter construct (Fig. 7A) or larger upstream regions (data not shown) exhibit a pattern of lacZ expression similar to that of DK5247: lacZ expression of these constructs is consistently reduced about twofold in a csgA background, indicating that the developmental promoter downstream of −101 is dependent upon csgA for full activity. The −76 promoter construct (Fig. 7A) and smaller upstream regions (data not shown) failed to express lacZ in csgA cells, just as in wild-type cells. As reported previously (14), the pREG1727 vector with no insert of M. xanthus DNA showed substantial lacZ expression in csgA mutant cells, which we attribute to a promoter in the vicinity of the attB integration site. Interestingly, Ω4400 upstream DNA appeared to reduce this readthrough transcription (see Discussion).

FIG. 7.

Developmental expression of lacZ under control of the Ω4400 promoter in a csgA background in the absence (A) and presence (B) of extracellular complementation. (A) Developmental β-galactosidase specific activity was measured for Ω4400 Tn5 lac-containing csgA strain DK5247 (□) and for at least three independently isolated transductants of DK5208 (csgA) containing a single copy of Ω4400 upstream DNA extending to −101 (▪) or −76 (○) fused to lacZ and integrated at Mx8 attB. The β-galactosidase activity of DK5208 (csgA) containing the pREG1727 vector alone with no insert integrated at Mx8 attB (▵) is also shown. (B) The strains used for panel A were codeveloped with an equal number of wild-type DK1622 cells (which express csgA but not lacZ), and the β-galactosidase specific activity was determined as previously described (34). β-galactosidase specific activity is expressed in nanomoles of o-nitrophenyl phosphate per minute per milligram of protein.

To determine whether extracellular signaling could restore Ω4400 promoter activity, csgA mutant cells with either the −101 or −76 promoter construct integrated at Mx8 attB were mixed and codeveloped with an equal number of wild-type strain DK1622 cells, which served as C-signal donors (Fig. 7B). Developmental β-galactosidase expression from the −101 promoter construct in csgA mutant cells mixed with DK1622 was restored to a level similar to that observed in csgA+ cells. The pattern and level of expression from this construct were similar to those observed for DK5247 mixed with DK1622 (Fig. 7B). In contrast, expression from csgA mutant cells containing the −76 promoter construct was not stimulated by codevelopment with DK1622 (Fig. 7B). Expression from the −76 construct was comparable to the β-galactosidase expression observed in mixing experiments with the vector-alone control (Fig. 7B). We conclude that DNA downstream of −101 bp in the Ω4400 promoter region is sufficient for the promoter to be stimulated by extracellular C signaling.

Ω4400 Tn5 lac expression is not dependent upon sigB or sigC.

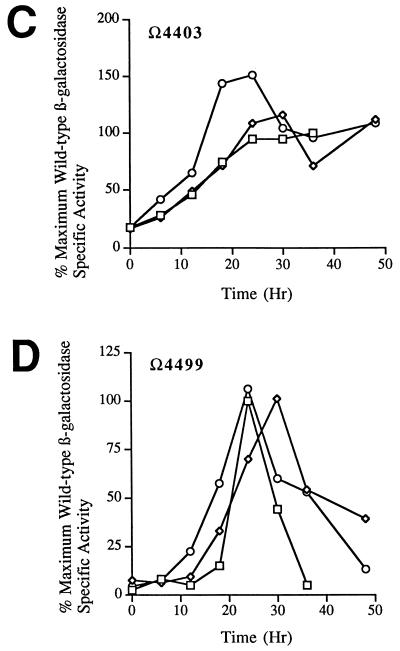

Several genes that appear to encode sigma subunits of RNA polymerase have been identified in M. xanthus (1, 2, 17, 24, 30). Two of these genes, sigB (1) and sigC (2), have been shown to be expressed during development. To determine whether the activity of the promoter positioned upstream of the Ω4400 insertion is dependent upon the product of sigB or sigC, developmental β-galactosidase activity of Ω4400 Tn5 lac (Tcr) was measured in sigB and sigC-1 mutant backgrounds. Expression of Ω4400 Tn5 lac (Tcr) in either a sigB or a sigC-1 mutant background did not differ appreciably from Ω4400 expression in a wild-type background (Fig. 8A). In all cases, β-galactosidase activity was first detected at approximately 6 to 12 h into development and reached a similar maximum level approximately 24 h into development. The mutant sigB and sigC-1 alleles were also transduced into strains containing Ω4403 Tn5 lac (Tcr) (Fig. 8B) or Ω4459 Tn5 lac (Tcr) (Fig. 8C), two fusions that depend absolutely on csgA for expression (33), and into a strain containing Ω4499 Tn5 lac (Tcr) (Fig. 8D), which, like Ω4400 Tn5 lac, depends partially upon csgA for expression (33). Again, developmental lacZ expression in either mutant background was very similar to expression in a wild-type background with respect to both the timing of expression and the maximum level of β-galactosidase activity obtained. Thus, expression of these csgA-dependent genes is not dependent upon the action of either the sigB or the sigC gene product.

FIG. 8.

Developmental lacZ expression of C-dependent promoters in sigB and sigC-1 mutant backgrounds. In each panel, specific activities are given as percentages of the maximum activity observed for the corresponding wild-type (sigB+ sigC+), Tn5 lac (Tcr)-containing parental strain. The developmental β-galactosidase curves of the parental strains (□) represent the average of two assays, and the curves of the Tn5 lac (Tcr)-containing sigB (◊) and sigC-1 (○) mutant strains represent the average of three independently isolated transductants, each assayed twice. Panels: A, Ω4400 Tn5 lac (Tcr); B, Ω4459 Tn5 lac (Tcr); C, Ω4403 Tn5 lac (Tcr); D, Ω4499 Tn5 lac (Tcr).

DISCUSSION

We have cloned and identified the Ω4400 promoter, which depends partially upon intercellular C signaling for expression during M. xanthus development. Deletion analysis and mapping of the Ω4400 mRNA 5′ end showed that DNA between −101 and −76 is essential for transcription from this promoter. DNA sequences in the −10 and −50 regions of the Ω4400 promoter were strikingly similar to sequences in the corresponding regions of the Ω4403 promoter (14), which depends absolutely on C signaling for expression (33). These results begin to define the cis-acting regulatory elements important for C-signal-dependent gene expression and lay the foundation for identification of the regulatory proteins involved.

Downstream of the Ω4400 promoter is an ORF that is likely to be translated in M. xanthus and may encode a protein that binds ATP or GTP. The predicted ATG translational start codon of this ORF at position 609 is located 65 bp downstream from the transcriptional start site (Fig. 4). It is possible that translation begins at the GTG at position 603, but this codon does not appear to be preceded by a satisfactory ribosome-binding site. If translation of the ORF initiated at position 609, it would continue for 138 amino acids until interrupted by a translational stop codon internal to Tn5 lac Ω4400. A 44-amino-acid region of this partial ORF shows a high degree of similarity to the E. coli arsenical pump-driving ATPase (45). In particular, this region of the partial ORF resembles the adenylate-binding site of the arsenite-stimulated ATPase. This glycine-rich region of sequence similarity is found in many proteins that bind ATP or GTP and probably forms a flexible loop that interacts with one of the phosphate groups of the nucleotide (49, 58). It therefore appears that the ORF interrupted by the Ω4400 insertion encodes a protein that binds either ATP or GTP, but the actual function of this protein is unknown. Cells containing a Tn5 lac Ω4400 insertion grow and develop normally (34), so the protein product of this ORF may not be essential for growth, aggregation, or sporulation of M. xanthus. Alternatively, it is possible that the Ω4400 insertion does not render this protein nonfunctional, since the putative ATP- or GTP-binding site remains intact. Further mutational analysis is needed to test this possibility.

The Ω4400 promoter is likely to be developmentally regulated at the level of transcription initiation. The promoter appears to be inactive in growing cells, since β-galactosidase activity from lacZ fusions to the promoter remained at a low background level and no Ω4400 mRNA was detected by S1 nuclease or primer extension analyses. A simple model to explain developmental regulation of the Ω4400 promoter is that one or more essential transcription factors are made or become active during development. We cannot exclude the possibility that the Ω4400 promoter is active during both growth and development, but the mRNA is rapidly degraded in growing cells and is stabilized during development; however, this model would require that Ω4400-lacZ fusion mRNA also exhibit differential stability in growing and developing cells.

The DNA sequence immediately upstream of the Ω4400 transcriptional start site does not match the sequence of any M. xanthus promoter transcribed by a known form of RNA polymerase. In the −10 region, the sequence 5′-TACAAC-3′ contains four matches to the 5′-TATAAT-3′ consensus for promoters transcribed by E. coli ς70 (39) or Bacillus subtilis ς43 (22) RNA polymerase, the major vegetative RNA polymerases in these organisms. However, no sequence in the −35 region of the Ω4400 promoter matches the 5′-TTGACA-3′ consensus. Moreover, partially purified RNA polymerase from growing M. xanthus cells, which contains ςA, the major vegetative ς factor (5), does not transcribe from the Ω4400 promoter in vitro (4). The DNA sequence of the Ω4400 promoter also does not resemble those of the Ω4521 (18, 29) and mbhA promoters (44), which are likely to be transcribed by ς54 RNA polymerase (30), or that of the carQRS promoter (40), which appears to be transcribed by RNA polymerase containing the CarQ sigma factor (6, 17). Two other putative ς factors from M. xanthus, SigB (1) and SigC (2), have been described, but promoters recognized by RNA polymerase containing these sigma factors have not been identified. We showed that a null mutation in sigB or sigC does not affect expression of the Ω4400 promoter or the promoters of several other C-dependent genes (Fig. 8). Thus, the Ω4400 promoter may be transcribed by RNA polymerase containing a novel sigma factor.

The Ω4400 promoter sequence is strikingly similar to that of the Ω4403 promoter, which also depends upon C signaling for expression. In Fig. 6, a five-of-six match is noted between sequences centered at about −10. It should also be noted that the sequence 5′-ACACCC-3′ is present in both promoters slightly closer to the transcriptional start site. Typically, promoters recognized by RNA polymerase containing the same ς factor in the ς70 family exhibit similar sequences in the −35 regions. The Ω4400 and Ω4403 promoters are not similar in the −35 regions. However, both promoters have the sequence 5′-CATCCCT-3′ centered at −49. This could mean that the two promoters are recognized by the same RNA polymerase holoenzyme containing a novel type of ς subunit that recognizes the −50 and −10 regions of promoters. Alternatively, perhaps the RNA polymerase holoenzyme recognizes only the −10 region, as is the case for bacteriophage T4 late promoters recognized by RNA polymerase containing the phage gene 55 protein (12, 28), and another transcription factor binds to the −50 region and activates transcription. Mutational analyses are required to test the importance of the −50 and −10 elements for transcription of the Ω4400 and Ω4403 promoters.

DNA upstream of the −50 element is essential for transcription of both the Ω4400 and Ω4403 promoters. The deletion analysis reported here showed that DNA between −101 and −76 is necessary for Ω4400 promoter activity. It was shown previously that DNA between −80 and −72 is critical for Ω4403 promoter activity (14). Since RNA polymerase typically does not interact with DNA more than about 50 bp upstream of the transcriptional start site, these findings suggest that transcription of both promoters requires activator proteins to bind upstream. Transcriptional activators often bind to palindromic DNA sequences. Short palindromes, as well as other types of repeat sequences, are present in the upstream regions of both promoters (Fig. 6). However, the two promoters do not have an upstream sequence in common. This suggests that different activator proteins are involved in transcription of the Ω4400 and Ω4403 promoters. Two findings had suggested previously that these two promoters are not regulated identically. First, Tn5 lac Ω4403 appeared to be expressed slightly later during development than Tn5 lac Ω4400 (34). Now that the appropriate probes have been developed, this should be examined more carefully by measuring the accumulation of both Ω4400 and Ω4403 mRNAs in the same cells collected at short time intervals during development. Second, the promoters exhibited different patterns of dependence upon csgA (33). Expression of Tn5 lac Ω4403 was abolished in csgA mutant cells, but expression of Tn5 lac Ω4400 was reduced, reaching about half the level of expression in wild-type cells at the time of wild-type peak activity.

The minimal Ω4400 promoter defined by our deletions, containing DNA to −101, showed a pattern of dependence upon csgA and rescue by extracellular C signaling similar to that of Tn5 lac Ω4400 (Fig. 7). This indicates that the DNA element(s) needed for C-signal responsiveness lies downstream of or within the essential promoter region. It remains to be seen whether promoter mutations can be isolated that allow delayed or reduced developmental expression but eliminate the response to C signaling.

A protein that mediates the C-signal response has been identified recently. Certain Tn5 lac insertion mutations that disrupted the ability of cells to respond to C signaling lie in the fruA gene (11, 42, 54). A null mutation in fruA abolishes developmental expression from Tn5 lac Ω4500 (42), which is thought to lie in the same transcription unit as Tn5 lac Ω4403 (34). Expression of the Ω4400 promoter in fruA mutant cells has not been reported. FruA is similar to response regulators of two-component signal transduction systems (42). The Ω4403 and Ω4400 promoter regions are potential targets for FruA binding, although it is possible that FruA directly regulates another gene(s) which, in turn, regulates the C-signal-dependent promoters.

It has been observed previously that the activity of certain C-dependent promoters is reduced when lacZ fusion constructs are integrated at the Mx8 attB site, compared to the activity of constructs located at the native chromosomal site (14, 38, 57). This positional inhibition of C-dependent promoter activity is particularly strong when the promoter to be tested is expressed late in development and is absolutely dependent upon C signaling. The Ω4400 promoter, which is active relatively early in development and is only partially dependent upon C signaling for developmental expression, does not appear to be very sensitive to this inhibition of expression. The deletion constructs shown to contain an active promoter produced nearly as much β-galactosidase activity as the original Tn5 lac Ω4400-containing strain. It has been speculated that differential condensation of the chromosome during development might account for the position-dependent expression of some promoters (57). Perhaps the Ω4400 promoter region is resistant to such condensation. The results presented here show that the method described in this and an earlier report (14) for the cloning of DNA fragments into the pREG1727 promoter testing vector and the integration of these constructs at the Mx8 attB site is an excellent method for the analysis of M. xanthus promoters that are not subject to the position effect. Southern blot analysis or diagnostic PCR allows the rapid identification of integrants containing a single copy of the plasmid construct, and this method is not dependent upon homologous recombination between the insert and the chromosome, so the insert can be quite small (<300 bp) without affecting the ease with which integrants are generated.

It has also been observed previously that the pREG1727 vector alone expresses lacZ under developmental conditions when integrated at the Mx8 attB site of csgA mutant cells (14) (Fig. 7A). No developmental lacZ expression is detected when pREG1727 alone is integrated at Mx8 attB in wild-type cells (14) (Fig. 2). Taken together, these results indicate that a developmental promoter must be located upstream of lacZ in the vector or in the M. xanthus DNA proximal to the Mx8 attB site, and this promoter must be negatively regulated by C signaling. Interestingly, when the Ω4400 upstream DNA fragments that were shown to have no developmental promoter activity were cloned into pREG1727 and integrated at the Mx8 attB site of csgA mutant cells, no promoter activity was detected (Fig. 7A and data not shown). The promoterless Ω4400 upstream DNA fragments somehow prevented readthrough transcription from the promoter in the vicinity of the Mx8 attB site. This result was unexpected because Ω4403 upstream DNA fragments did not appear to impede the readthrough transcription, nor did the presence of factor-independent transcriptional terminators which had been engineered into the vector in the hope of preventing such readthrough transcription (14). The smallest fragment of Ω4400 upstream DNA that we tested, the SmaI-BamHI fragment, was capable of inhibiting the readthrough transcription (data not shown). Therefore, inhibitory DNA is located within the putative coding region of the gene disrupted by Tn5 lac Ω4400. Obviously, the inhibitory DNA does not prevent transcription initiated by the Ω4400 promoter from proceeding downstream to the site of Tn5 lac Ω4400 insertion. However, it is an intriguing possibility that this segment of DNA plays a regulatory role, perhaps causing the reduced expression of Tn5 lac Ω4400 during the development of csgA mutant cells compared to that of wild-type cells (33) (Fig. 7A). This possibility can be tested by deleting segments of DNA between the Ω4400 promoter and the Ω4400 insertion site.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Y. Cheng, D. Kaiser, S. Inouye, and M. Fisseha for providing bacterial strains used in this study.

This research was supported by NIH grant GM47293 and by the Michigan Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apelian D, Inouye S. Development-specific ς-factor essential for late-stage differentiation of Myxococcus xanthus. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1396–1403. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.8.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Apelian D, Inouye S. A new putative sigma factor of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3335–3342. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3335-3342.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avery L, Kaiser D. In situ transposon replacement and isolation of a spontaneous tandem genetic duplication. Mol Gen Genet. 1983;191:99–109. doi: 10.1007/BF00330896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biran, D., and L. Kroos. Unpublished data.

- 5.Biran D, Kroos L. In vitro transcription of Myxococcus xanthus genes with RNA polymerase containing ςA, the major sigma factor in growing cells. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:463–472. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4751843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Browning D, Khoshkhoo N, Hodgson D. Abstracts of the 24th Annual Meeting on the Biology of the Myxobacteria. 1997. CarQ is a sigma factor, CarR is an inner membrane protein of Myxococcus xanthus and CarS appears not to be a DNA binding protein; p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campos J M, Geisselsoder J, Zusman D R. Isolation of bacteriophage Mx4, a generalized transducing phage of Myxococcus xanthus. J Mol Biol. 1975;119:167–178. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90431-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Downard J, Ramaswamy S V, Kil K-S. Identification of esg, a genetic locus involved in cell-cell signaling during Myxococcus xanthus development. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7762–7770. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.24.7762-7770.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Downard J S, Kim S-H, Kil K-S. Localization of the cis-acting regulatory DNA sequences of the Myxococcus xanthus tps and ops genes. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4931–4938. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.10.4931-4938.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dworkin M. Recent advances in the social and developmental biology of the myxobacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:70–102. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.1.70-102.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellehauge E, Lobedanz S, Sogaard-Andersen L. Abstracts of the 24th Annual Meeting on the Biology of the Myxobacteria. 1997. The class II protein, a key protein in the C-factor signal transduction pathway, is a response regulator with a C-terminal DNA-binding domain and may act in a C-factor-dependent phosphorelay system; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elliott T, Geiduschek E. Defining a bacteriophage T4 late promoter: absence of a “−35” region. Cell. 1984;36:211–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fawcett T, Bartlett S. An effective method for eliminating “artifact banding” when sequencing double-stranded DNA templates. BioTechniques. 1990;9:46–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fisseha M, Gloudemans M, Gill R, Kroos L. Characterization of the regulatory region of a cell interaction-dependent gene in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2539–2550. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.9.2539-2550.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geisselsoder J, Campos J M, Zusman D R. Physical characterization of bacteriophage Mx4, a generalized transducing phage for Myxococcus xanthus. J Mol Biol. 1978;119:179–189. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gill R E, Cull M G, Fly S. Genetic identification and cloning of a gene required for developmental cell interactions in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5279–5288. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.11.5279-5288.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorham H, McGowan S, Robson P, Hodgson D. Light-induced carotenogenesis in Myxococcus xanthus: light-dependent membrane sequestration of ECF sigma factor CarQ by anti-sigma factor CarR. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:171–186. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.360888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gulati P, Xu D, Kaplan H B. Identification of the minimum regulatory region of a Myxococcus xanthus A-signal-dependent developmental gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4645–4651. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4645-4651.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagen D C, Bretscher A P, Kaiser D. Synergism between morphogenetic mutants of Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1978;64:284–296. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(78)90079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hagen T J, Shimkets L J. Nucleotide sequence and transcriptional products of the csg locus of Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:15–23. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.15-23.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanahan D. Studies on transformation of Escherichia coli with plasmids. J Mol Biol. 1983;166:557. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80284-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Helmann J. Compilation and analysis of Bacillus subtilis ςA-dependent promoter sequences: evidence for extended contact between RNA polymerase and upstream promoter DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2351–2360. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.13.2351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodgkin J, Kaiser D. Cell-to-cell stimulation of motility in nonmotile mutants of M. xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:2938–2942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.7.2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inouye S. Cloning and DNA sequence of the gene coding for the major sigma factor from Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:80–85. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.80-85.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaiser D. Social gliding is correlated with the presence of pili in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:5952–5956. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.11.5952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaiser D. Genetics of myxobacteria. In: Rosenberg E, editor. Myxobacteria, development and cell interactions. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1984. pp. 163–184. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaiser D, Kroos L. Intercellular signaling. In: Dworkin M, Kaiser D, editors. Myxobacteria II. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 257–284. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kassavetis G, Geiduschek E. Defining a bacteriophage T4 late promoter: bacteriophage T4 gene 55 protein suffices for directing late promoter recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5101–5105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.16.5101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keseler I, Kaiser D. An early A-signal-dependent gene in Myxococcus xanthus has a ς54-like promoter. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4638–4644. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.16.4638-4644.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keseler I, Kaiser D. ς54, a vital protein for Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1979–1984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S K, Kaiser D. C-factor has distinct aggregation and sporulation thresholds during Myxococcus development. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1722–1728. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1722-1728.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroos L, Kaiser D. Construction of Tn5 lac, a transposon that fuses lacZ expression to exogenous promoters, and its introduction into Myxococcus xanthus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:5816–5820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroos L, Kaiser D. Expression of many developmentally regulated genes in Myxococcus depends on a sequence of cell interactions. Genes Dev. 1987;1:840–854. doi: 10.1101/gad.1.8.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kroos L, Kuspa A, Kaiser D. A global analysis of developmentally regulated genes in Myxococcus xanthus. Dev Biol. 1986;117:252–266. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90368-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LaRossa R, Kuner J, Hagen D, Manoil C, Kaiser D. Developmental cell interactions of Myxococcus xanthus: analysis of mutants. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:1394–1404. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.3.1394-1404.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laue B E, Gill R. Use of a phase variation-specific promoter of Myxococcus xanthus in a strategy for isolating a phase-locked mutant. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5341–5349. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5341-5349.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li S-F, Lee B, Shimkets L J. csgA expression entrains Myxococcus xanthus development. Genes Dev. 1992;6:401–410. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li S-F, Shimkets L J. Site-specific integration and expression of a developmental promoter in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:5552–5556. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.12.5552-5556.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lisser S, Margalit H. Compilation of E. coli mRNA promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:1507–1516. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.7.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McGowan S, Gorham H, Hodgson D. Light-induced carotenogenesis in Myxococcus xanthus: DNA sequence analysis of the carR region. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:713–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Messing J. A multipurpose cloning system based on the single-stranded DNA bacteriophage M13. Recombinant DNA bulletin, publication no. 71-99. Bethesda, Md: National Institutes of Health; 1979. pp. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogawa M, Fujitani S, Mao X, Inouye S, Komano T. FruA, a putative transcription factor essential for the development of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:757–767. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.d01-1725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oyaizu H, Woese C. Phylogenetic relationships among the sulfate respiring bacteria, myxobacteria and purple bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1985;6:257–263. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Romeo J M, Zusman D R. Transcription of the myxobacterial hemagglutinin gene is mediated by a ς54-like promoter and a cis-acting upstream regulatory region of DNA. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2969–2976. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2969-2976.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosen B, Borbolla M. A plasmid-encoded arsenite pump produces arsenite resistance in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;124:760–765. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sager B, Kaiser D. Intercellular C-signaling and the traveling waves of Myxococcus. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2793–2804. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.23.2793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saraste M, Sibbald P, Wittinghofer A. The P-loop: a common motif in ATP- and GTP-binding proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990;15:430–434. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90281-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shimkets L. The myxobacterial genome. In: Dworkin M, Kaiser D, editors. Myxobacteria II. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimkets L J, Asher S J. Use of recombination techniques to examine the structure of the csg locus of Myxococcus xanthus. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;211:63–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00338394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shimkets L J, Gill R E, Kaiser D. Developmental cell interactions in Myxococcus xanthus and the spoC locus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1406–1410. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.5.1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimkets L J, Kaiser D. Induction of coordinated movement of Myxococcus xanthus cells. J Bacteriol. 1982;152:451–461. doi: 10.1128/jb.152.1.451-461.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sogaard-Andersen L, Slack F, Kimsey H, Kaiser D. Intercellular C-signaling in Myxococcus xanthus involves a branched signal transduction pathway. Genes Dev. 1996;10:740–754. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.6.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stellwag E, Fink J M, Zissler J. Physical characterization of the genome of the Myxococcus xanthus bacteriophage MX-8. Mol Gen Genet. 1985;199:123–132. doi: 10.1007/BF00327521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stephens K, Kaiser D. Genetics of gliding motility in Myxococcus xanthus: molecular cloning of the mgl locus. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;207:256–266. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thony-Meyer L, Kaiser D. devRS, an autoregulated and essential genetic locus for fruiting body development in Myxococcus xanthus. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7450–7462. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7450-7462.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walker J E, Saraste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. Distantly related sequences in the α- and β-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases, and other ATP-requiring enzymes and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]