Abstract

Background

In recent years, breast cancer has become the most common cancer in the world, increasing women’s health risks. Approximately 60% of breast cancers are categorized as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-low tumors. Recently, antibody-drug conjugates have been found to have positive anticancer efficacy in patients with HER2-low breast cancer, but more studies are required to comprehend their clinical and molecular characteristics.

Methods

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the data of 165 early breast cancer patients with pT1-2N1M0 who had undergone the RecurIndex testing. To better understand HER2-low tumors, we investigated the RecurIndex genomic profiles, clinicopathologic features, and survival outcomes of breast cancers according to HER2 status.

Results

First, there were significantly more hormone receptor (HR)-positive tumors, luminal-type tumors, and low Ki67 levels in the HER2-low than in the HER2-zero. Second, RI-LR (P = .0294) and RI-DR (P = .001) scores for HER2-low and HER2-zero were statistically significant. Third, within HER2-negative disease, HR-positive/HER2-low tumors showed highest ESR1, NFATC2IP, PTI1, ERBB2, and OBSL1 expressions. Fourth, results of the survival analysis showed that lower expression of HER2 was associated with improved relapse-free survival for HR-positive tumors, but not for HR-negative tumors.

Conclusions

The present study highlights the unique features of HER2-low tumors in terms of their clinical characteristics as well as their gene expression profiles. HR status may influence the prognosis of patients with HER2-low expression, and patients with HR-positive/HER2-low expression may have a favorable outcome.

Keywords: breast cancer with HER2-low expression, node-positive breast cancer, RecurIndex recurrence score, prognosis, targeted treatment

In this study, the data of patients with early stage breast cancer who had undergone RecurIndex testing was analyzed. To better understand HER2-low tumors, genomic profiles, clinicopathologic features, and survival outcomes of breast cancers according to HER2 status were investigated.

Implications for Practice.

This is the first study to examine the HER2-low status of breast cancer using the RecurIndex risk assessment model based on an 18-gene assay. According to this study, HER2-low tumors displayed distinctive biological characteristics, including clinicopathologic characteristics and gene expression patterns. The observation of better outcomes and lower RecurIndex recurrence scores in HER2-low tumors supports the hypothesis that low levels of HER2 expression have prognostic value.

Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the leading causes of death in women around the world,1 in which human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-negative breast cancer accounts for 80%-90% of all cases.1-3 There is a study showing that compared with hormone receptor (HR)-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer, the prognosis of HER2-positive breast cancer is more dismal.4 With the development of the drugs targeting HER2, including trastuzumab, pertuzumab, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKI), the clinical outcomes and survival of patients with HER2-positive breast cancer have been greatly improved.5-7 However, for HER2-negative breast cancer, little activity has been found with most HER2-targeting drugs.8,9

Currently, HER2 status is assessed based on the most recent American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)/College of American Pathologists (CAP) updated guidelines.10,11 Among the HER2-negative tumors, 60% are classified as HER2-low (immunohistochemistry [IHC] 1+ or 2+/fluorescence in situ hybridization [FISH]-negative) if they can express HER2 at some level and are detected using IHC and FISH techniques.12 A previous study indicated that patients with HER2-low breast cancer seemed unlikely to derive benefits from HER2-targeted therapies.13 Nevertheless, trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd) and trastuzumab duocarmazine (SYD985), 2 HER2-directed antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), have recently discovered to have promising clinical activity for HER2-low breast cancer.14,15 A phase 3 trial DESTINY-Break04 also showed promising results,16 opening the possibility of expanding anti-HER2 therapy to a wider group of patients.

It is well known that there exists substantial heterogeneity within HER2-negative disease. According to a recent retrospective study from China, HER2-low breast cancer differs clinically and genetically from HER2-positive (IHC 3+ or IHC 2+/FISH-positive) and HER2-zero cancer, indicating a separate genetic background for HER2-low breast cancer.17 Some studies revealed comparable clinical and survival results in HER2-zero and HER2-low breast cancers,18,19 while others reported that HER2-low tumors were a distinct group of cancers.20-22 Considering increasing interests in HER2-low breast cancer, it is very necessary to fully comprehend its clinicopathological and molecular characteristics, as well as patients’ survival outcomes.

RecurIndex assay, a multigene signature, has been demonstrated to predict the survival outcomes in patients with early-stage breast cancer.23-25 However, it remains unclear about the relationship between HER2 expression status and RecurIndex recurrence score (RS). In this study, we analyzed the RecurIndex RS, 18-gene expression profiles, clinicopathological features and survival outcomes according to HER2 expression status.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Patients who were surgically treated for primary invasive breast cancer at the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University between March 2011 and December 2015 were included in the study. According to the previous description, RecurIndex testing was conducted on pT1-2N1M0 patients’ tumor samples.26 Participants will be enrolled in the study if they meet the following criteria: (1) patients with RecurIndex RS results produced by an 18-gene targeted panel from ribonucleic acid (RNA) collected from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) surgical excision specimens; (2) available data on HER2 status assessed by IHC and/or FISH, and (3) complete clinical, pathological, and follow-up information. We excluded patients whose HER2 status was ambiguous or unknown. The patients gave their informed permission. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University (approval No.: 2020115) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

IHC-Based Classification

A specialized breast cancer pathologist confirmed all pathological slides. A tumor expressing estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR) by ≥1% was considered HR-positive, and a tumor expressing ER and PR by <1% was considered triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). A low/intermediate Ki67 (<30%) and a high Ki67 (≥30%) group was created by the International Ki67 Working Group (IKWG).27 According to the ASCO/CAP recommendations, HER2 IHC expression was evaluated.11 HER2-positive breast cancer was defined as having an IHC staining of 3+ or 2+ and positive FISH, whereas HER2-negative breast cancer had an IHC staining of 0, 1+, or 2+ and a negative FISH.

RecurIndex Testing

RecurIndex contained 18 genes (ESR1, ERBB2, MMP15, PHACTR2, TCF3, TPX2, C16ORF7, PIM1, DDX39, BLM, NFATC2IP, SF3B5, OBSL1, CLCA2, TRPV6, CCR1, BUB1B, and PTI1) and the LGM-CM4 and DGM-CM6 models’ full development processes were disclosed in our prior paper.24 We calculated the recurrence indices for local recurrences (RI-LR) and distant recurrences (RI-DR) based on the LGM-CM6 and DGM-CM6 models. The RI-LR cutoff value of 27 and the RI-DR cutoff value of 33 were used to classify patients into high- and low-risk groups for LRR and DR, respectively.

To test RecurIndex, RNA was isolated from FFPE tumor tissues from surgical specimens. An analysis of gene-expression profiles was conducted by reverse transcriptase quantitative real-time PCR on the PanelStation platform, requiring at least 800 ng of total RNA. Target gene expression levels were independently adjusted to those of housekeeping genes. We generated recurrence risk scores from gene expression profiles and clinical variables using analysis software.24

Survival Analysis

Recurrence-free survival (RFS) refers to the time from surgery until ipsilateral chest, breast, or regional lymph node recurrence, distant metastases, death, or last follow-up. The overall survival (OS) is calculated between the date of the initial diagnosis and the date of death or the last follow-up. The final follow-up deadline was October, 20 2022.

Statistical Analysis

Survival curves were created using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Student’s t-test was performed on continuous variables with a normally distributed distribution, and the mean (SD) was calculated for each variable. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. The Cox regression model was used to examine prognostic factors for RFS and OS with a 95% CI. The value of P < .05 was used to determine whether any differences were significant. We used IBM SPSS version 24.0 to conduct all our statistical analyses.

Results

Characteristics of the Baseline Patients

Our study design is illustrated in Fig. 1. Two hundred and thirteen breast cancer patients with pT1-2N1M0 and RecurIndex RS information were found. In the final analysis, 165 individuals were included after excluding 13 patients with unknown HER2 status and 35 patients with ambiguous HER2 status (Fig. 1). Overall, 27 (16.4%) had HER2-zero tumors, 93 (56.4%) had HER2-low and 45 (27.3%) had HER2-positive tumors. The baseline characteristics of three HER2 subgroups are compared in Table 1. Statistically distinct HR status, histological grade, lymphovascular invasion (LVI), Ki67, IHC-based molecular subgroup, and RI-LR and RI-DR risk groups were presented in 3 HER2 subgroups. The tumor stage, age, adjuvant chemotherapy, and PMRT did not show statistically significant differences.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Table 1.

Population characteristics according to HER2 status.

| Demographics | Total (n = 165) | HER2-zero (n = 27) | HER2-low (n = 93) | HER2-positive (n = 45) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 50.5 (10.6) | 51.0 (9.7) | 50.6 (10.7) | 49.9 (11.1) | Ns |

| Histologic grade | Zero vs. low, ns | ||||

| Ⅰ | 3 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | Zero vs. positive, ns |

| Ⅱ | 85 (51.5) | 11 (40.7) | 56 (60.2) | 18 (40.0) | Low vs. positive, P = .022 |

| Ⅲ | 77 (46.7) | 16 (59.3) | 34 (36.6) | 27 (60.0) | |

| Tumor stage | ns | ||||

| T1 | 77 (46.7) | 11 (40.7) | 48 (51.6) | 18 (40.0) | |

| T2 | 88 (53.3) | 16 (59.3) | 45 (48.4) | 27 (60.0) | |

| LVI | Zero vs. low, ns | ||||

| Yes | 75 (45.5) | 12 (44.4) | 37 (39.8) | 26 (57.8) | Zero vs. positive, P = .047 |

| No | 90 (54.5) | 15 (55.6) | 56 (60.2) | 19 (42.2) | Low vs. positive, ns |

| ER status | Zero vs. low, P = .003 | ||||

| Negative | 40 (24.2) | 10 (37.0) | 10 (10.8) | 20 (44.4) | Zero vs. positive, ns |

| Positive | 125 (75.8) | 17 (63.0) | 83 (89.2) | 25 (55.6) | Low vs. positive, P < .001 |

| PR status | Zero vs. low, P = .006 | ||||

| Negative | 58 (35.2) | 13 (48.1) | 20 (21.5) | 25 (55.6) | Zero vs. positive, ns |

| Positive | 107 (64.8) | 14 (51.9) | 73 (78.5) | 20 (44.4) | Low vs. positive, P < .001 |

| HR status | Zero vs. low, P = .013 | ||||

| Negative | 37 (22.4) | 9 (33.3) | 10 (10.8) | 18 (40.0) | Zero vs. positive, ns |

| Positive | 128 (77.6) | 18 (66.7) | 83 (89.2) | 27 (60.0) | Low vs. positive, P < .001 |

| Ki67 | Zero vs. low, ns | ||||

| Low (<30%) | 51 (30.9) | 6 (22.2) | 36 (38.7) | 9 (20.0) | Zero vs. ppositive, ns |

| High (≥30%) | 114 (69.1) | 21 (77.8) | 57 (61.3) | 36 (80.0) | Low vs. positive, P = 0.028 |

| Immunohistochemistry-based molecular subgrouping | Zero vs. low, P = .020 | ||||

| Luminal A (HR+/HER2-/Ki67<14%) | 20 (12.1) | 2 (7.4) | 18 (19.4) | 0 (0.0) | Zero vs. positive, P < .001 |

| Luminal B (HR+/HER2-/Ki67≥14%) | 81 (49.1) | 16 (59.3) | 65 (69.9) | 0 (0.0) | Low vs. positive, P < .001 |

| HER2-enriched (HR+/HER2+) | 27 (16.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 27 (60.0) | |

| HER2-enriched (HR-/HER2+) | 18 (10.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 18 (40.0) | |

| Triple-negative (HR-/HER2−) | 19 (11.5) | 9 (33.3) | 10 (10.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| RI-LR | Zero vs. low, P = .030 | ||||

| Low-risk | 61 (37.0) | 7 (25.9) | 46 (49.5) | 8 (17.8) | Zero vs. positive, ns |

| High risk | 104 (63.0) | 20 (74.1) | 47 (50.5) | 37 (82.2) | Low vs. positive, P < .001 |

| RI-DR | Zero vs. low, ns | ||||

| Low-risk | 20 (12.1) | 1 (3.7) | 17 (18.3) | 2 (4.4) | Zero vs. positive, ns |

| High-risk | 145 (87.9) | 26 (96.3) | 76 (81.7) | 43 (95.6) | Low vs. positive, P = .027 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | Ns | ||||

| Yes | 151 (91.5) | 25 (92.6) | 83 (89.2) | 43 (95.6) | |

| No | 9 (5.5) | 1 (3.7) | 6 (6.5) | 2 (4.4) | |

| Unknown | 5 (3.0) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy | Zero vs. low, ns | ||||

| Yes | 108 (65.5) | 15 (55.6) | 70 (75.3) | 23 (51.1) | Zero vs. positive, ns |

| No | 55 (33.3) | 12 (44.4) | 22 (23.7) | 21 (46.7) | Low vs. positive, P = 0.010 |

| Unknown | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (2.2) | |

| PMRT | ns | ||||

| Yes | 106 (64.2) | 19 (70.4) | 55 (59.1) | 32 (71.1) | |

| No | 59 (35.8) | 8 (29.6) | 38 (40.9) | 13 (28.9) |

Abbreviations: HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hormone receptor; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; ns, not statistically significant; PMRT, postmastectomy radiotherapy; PR, progesterone receptor

In view of the significant unbalance in the proportion of HER2-zero and HER2-low disease regarding HR status, we compared the RI-LR score, RI-DR score, Ki67 levels, and molecular subtypes between HER2-zero/HR+, HER2-low/HR+, HER2-zero/HR−, and HER2-low/HR− tumors. The results showed significantly higher RI-LR and RI-DR scores and Ki67 levels in HER2-low/HR− tumors than in HER2-low/HR+ tumors (P < .0001, P < .0001, P = .0004, respectively), as well as those in HER2-zero/HR− tumors than in HER2-zero/HR+ tumors (P = .0296, P < .0001, P = .0272, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S1A–S1C). Regarding the molecular subtype, no significant differences were presented between HER2-zero/HR+ and HER2-low/HR+ tumors (P = .514) (Supplementary Fig. S1D).

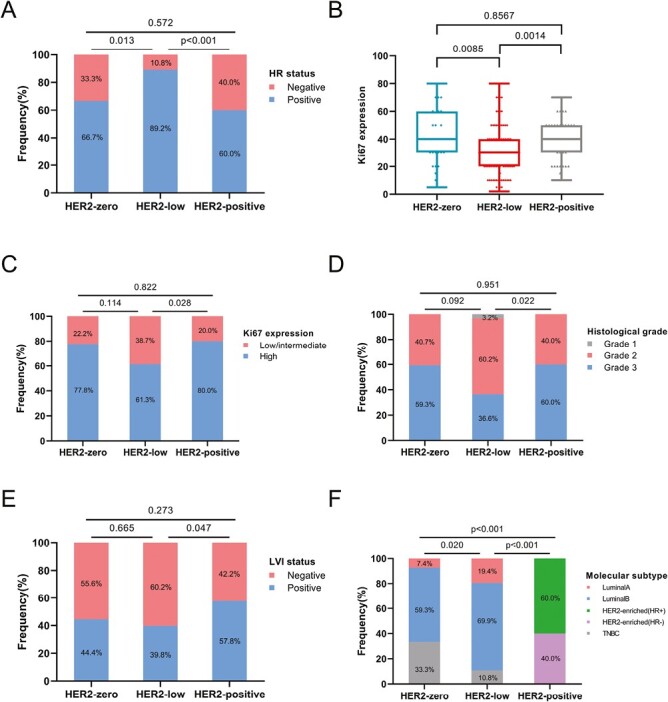

Distinct Clinicopathological Characteristics of HER2-Low Breast Disease

Fig. 2A shows that the HER2-low subgroup had a higher proportion of HR-positive disease than either HER2-zero (89.2% vs. 66.7%, P = .013) or HER2-positive (89.2% vs. 60.0%, P = .001). As opposed to HER2-zero and HER2-positive tumors, HER2-low tumors were more frequently discovered with low Ki67 values (P = .0085 and P = .0014, respectively) (Fig. 2B). In comparison to HER2-positive tumors, the HER2-low tumors exhibited significantly elevated percentages of the low/intermediate-Ki67 group (38.7% vs. 20.0%, P = .028, Fig. 2C), histological grade II (60.2% vs. 40.0%, P = .022, Fig. 2D), and LVI-negative (60.2% vs. 42.2%, P = .047, Fig. 2E). However, a comparison of the Ki67, histological grade, or LVI of HER2-zero and HER2-low did not reveal any statistically significant differences (Fig. 2C–2E). Additionally, the molecular subtype (determined by IHC) distribution of the HER2-low tumors differed considerably from that of the HER2-positive (P < .001) and HER2-zero (P = .020) subgroups (Fig. 2F). Tumors with luminal A and B were more common in the HER2-low group (19.4% vs. 7.4% and 69.9% vs. 59.3%, respectively), although the proportion of TNBC tumors was significantly lower (10.8% vs. 33.3%).

Figure 2.

Different clinical characteristics of the HER2 subgroups included (A) hormone receptor (HR) expression status, (B, C) Ki67 expression levels, (D) histological grade, (E) lymphovascular invasion (LVI) status, and (F) IHC-based molecular subtype distribution.

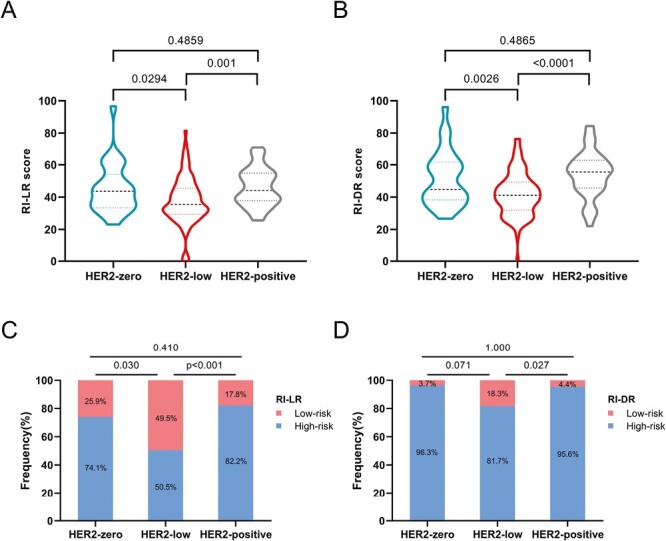

Associations Between HER2 Expression and RecurIndex RS

The average RI-LR scores were 45.4, 37.7, and 46.1 in HER2-zero, HER2-low, and HER2-positive subgroups, respectively. And the average RI-DR scores were 51.6, 41.9, and 54.2, respectively. The HER2-low category had a considerably lower RI-LR score than the HER2-zero (P = .0294) and HER2-positive groups (P = .001), indicating that it had a reduced local recurrent recurrence index (Fig. 3A). The HER2-low category also showed a substantially lower RI-DR score than the HER2-zero (P = .0026) and HER2-positive groups (P < .0001), indicating that a reduced recurrence index for distant metastases was observed in these patients (Fig. 3B). The 18-gene classifier was more likely to stratify HER2-low patients into RI-LR-low-risk compared to HER2-zero (49.5% vs. 25.9%, P = .030) and HER2-positive (49.5% vs. 17.8%, P = .001) subgroups (Fig. 3C). The proportion of RI-DR low-risk tumors in HER2-low tumors was also higher than in HER2-positive tumors (18.3% vs. 4.4%, P = .027; Fig. 3D).

Figure 3.

Associations between HER2 expression and (A, B) RecurIndex recurrence scores (RSs) and (C, D) distribution of RecurIndex risk group risk groups.

It was found, however, that the distribution of RI-DR low-risk was not different within HER2-negative tumors (P = .071; Fig. 3D).

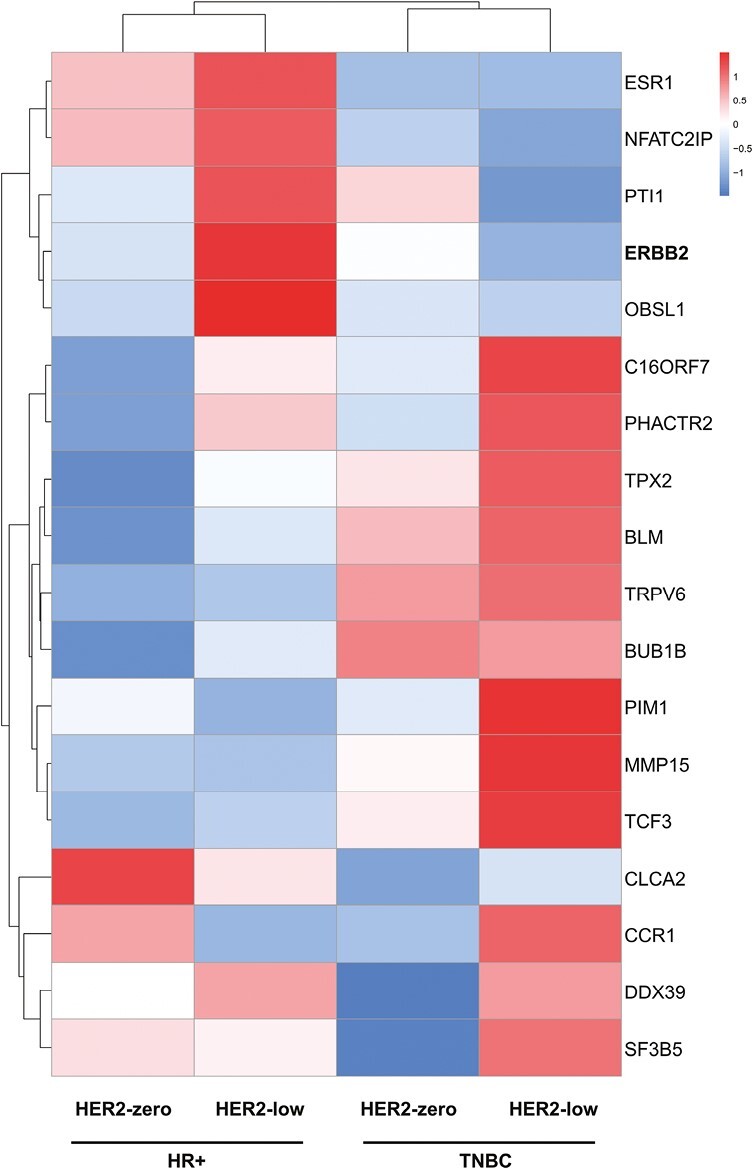

18-Gene Expression Analysis

We examined the levels of ERBB2 in 3 subgroups. The HER2-positive subgroup had the highest ERBB2 expression, as expected. The expression of ERBB2 was noticeably higher in HER2-positive tumors than in HER2-zero (P < .0001) or HER2-low (P < .0001) subgroups, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. S2. HER2-low tumors had considerably higher ERBB2 levels than HER2-zero tumors within HER2-negative disease (P = .0273; Supplementary Fig. S2). Additionally, we looked at the 18 genes’ expression profiles in HER2-negative cancers in accordance with HR status, and we noticed unique gene expression patterns (Fig. 4). There is a higher expression of proliferation-related genes (such as BUB1B and TPX2) and proto-oncogenes (such as BLM and TCF3) in TNBC than in HR-positive in the HER2-negative population. On the other hand, in HR-positive tumors compared to TNBCs, the luminal-related gene ESR1 and the inflammatory gene NFATC2IP were found to be upregulated. Notably, ESR1, NFATC2IP, PTI1, ERBB2, and OBSL1 were highly expressed in HR-positive/HER2-low tumors.

Figure 4.

Supervised clustering of 18-gene expression profiles across 4 subgroups. Gene expression was calculated based on the average value of each group.

Survival and Prognosis

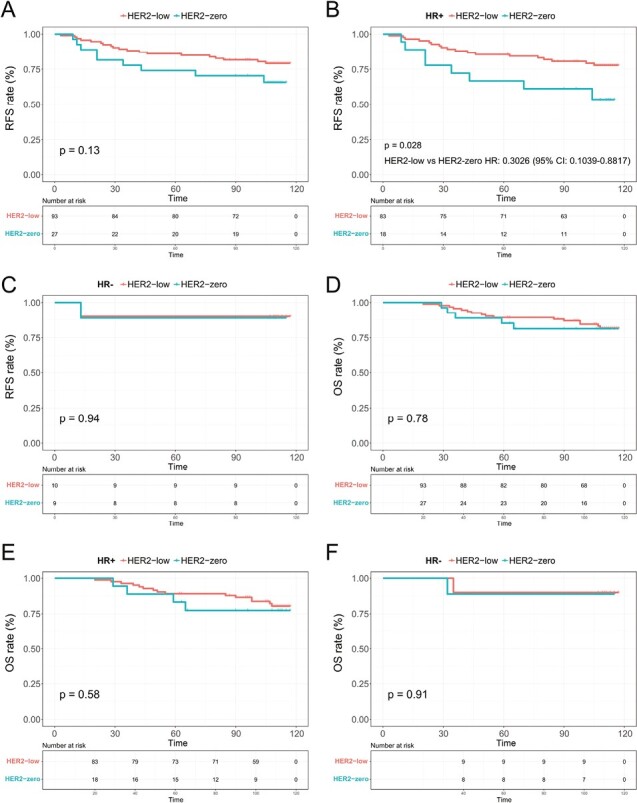

There was a median follow-up time of 110 months for the overall population (95% CI, 108.7-111.3). HER2-negative patients’ RFS was examined. In terms of RFS, the HER2-zero and HER2-low tumors were equivalent (65.7% vs. 79.2%, P = .13; Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) Kaplan-Meier curves. RFS for HER2-zero vs. HER2-low tumors in the (A) entire HER2-negative population, (B) HR-positive, and (C) HR-negative subgroups, and OS for HER2-zero vs. HER2-low tumors in the (D) entire cohort, (E) HR-positive, and (F) HR-negative population.

In Fig. 5B, it is shown that HER2-low tumors were significantly more likely to have a superior RFS than HER2-zero tumors (77.8% vs. 53.5%, HR: 0.3026, 95% CI, 0.1039-0.8817, P = .028), but not in the HR-negative subgroup (90.0% vs. 88.9%, P = .9389; Fig. 5C). As shown in Fig. 5D, the HER2-zero and HER2-low groups had no statistically significant differences in OS (P = 0.78). Based on HR status, similar outcomes were attained (Fig. 5E, 5F).

Table 2 lists the prognostic factors in the subgroup of HR-positive patients associated with RFS. Compared with T1 patients, T2 patients exhibited a substantially increased risk of recurrence (HR: 5.534, 95% CI, 1.821-16.815, P = .003). Recurrence was also more common in those under 40 years of age (HR: 0.182, 95% CI, 0.055-0.605, P = .005). Further, better RFS was associated with HER2-low tumors (HR: 0.314, 95% CI, 0.119-0.825, P = .019; Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate analyses of recurrence and metastasis in HR-positive patients.

| Variables | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P | ||

| Age, years | <40 | Reference | |

| ≥40 | 0.182 (0.055-0.605) | .005 | |

| Tumor stage | T1 | Reference | |

| T2 | 5.534 (1.821-16.815) | .003 | |

| LVI | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.841 (0.305-2.317) | .737 | |

| HER2 status | HER2-zero | Reference | |

| HER2-low | 0.314 (0.119-0.825) | .019 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.222 (0.143-10.450) | .855 | |

| Adjuvant endocrine therapy | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.489 (0.161-1.490) | .208 | |

| PMRT | No | Reference | |

| Yes | 0.755 (0.282-2.018) | .575 | |

Abbreviations: HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; HR, hazards ratios; LVI, lymphovascular invasion; PMRT, postmastectomy radiotherapy.

Discussion

Novel anti-HER2 drugs are showing promising efficacy in tumors with low HER2 expression, prompting investigations into the newly proposed “HER2-low” tumors. We found that 73% of patients in our study (120/165) had HER2-negative breast cancer, of whom a vast majority had HER2-low staining (IHC score 1+ or 2+ with negative FISH). In this study, a comparison of clinicopathologic traits, gene expression, and survival between HER2-zero, HER2-low, and HER2-positive breast cancers was conducted. HER2-zero patients had lower HR-positive rates, higher Ki-67 expressed values, and fewer grade II tumors than HER2-low patients, consistent with earlier studies.21,28 Less aggressive biology with low Ki67 and low histological grade in the HER2low subgroup could explain the better prognosis, which was observed in survival analysis and multivariable analysis.

In our study, the molecular profiles of HER2-low tumors were identified to separate from HER2-zero tumors including genetics, gene expression, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes. Berrino et al. found that ESR1 was more frequently mutated in HER2-zero and more SPEN mutation was detected in HER2-low.29 PAM50 analysis revealed that HER2-low cancers were predominantly luminal intrinsic subtypes, indicating that the HER2-low subgroup was primarily luminal gene-driven despite the low HER2 expression seen in the IHC results.30 Genes involved in tyrosine kinase receptors and proliferation-related genes have been found to be highly expressed in HER2-zero cancers.18 In HER2-low tumors, there was a decreased density of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, which suggested a link to a weakened immune response, according to a preliminary investigation by van den Ende et al.31 Based on an 18-gene expression profile, we found that HR-positive individuals expressed more luminal-related genes and inflammatory genes, whereas TNBC expressed more proto-oncogenes and proliferation-related genes. The difference was found between TNBC and HR-positive subtypes, regardless of IHC-based HER2 expression. Our translational profiling was limited to a few genes, which might explain the results.

To estimate the influence of HER2-low status on prognosis, survival analyses as well as recurrence scores based on RecurIndex were performed. This is the first study to use the RecurIndex risk assessment model based on an 18-gene assay to investigate the HER2-low status of breast cancer. Mutai et al. reported a study utilizing the Oncotype DX test, a 21-gene expression assay, which defined high risk as RS of 26 or higher. In ER-positive, early-stage breast tumors, HER2-zero had a similar proportion of Oncotype DX RS distributions than HER2-low tumors.32 On 281 cases, Zhang et al. performed a genomic profile of the MammaPrint recurrence risk and the BluePrint molecular subtypes. Researchers found that the majority of HER2-low breast cancers exhibited a low recurrence risk and a luminal A subtype.33 According to our study, RI-LR and RI-DR scores differed significantly between HER2-zero and HER2-low patients. Survival study results indicated that HR-positive individuals had an increased RFS if HER2 expression was low, but HR-negative individuals did not. All these results reinforced the evidence a low level of HER2 expression have a significant prognostic impact.32,34

It was shown that ERBB2 mRNA expression was correlated with IHC-based HER2 status, with HER2-zero versus HER2-low bearing a significant difference. The need for a more accurate and sensitive classification of HER2 in the clinical setting was highlighted by the high rate of discrepancy in IHC-based HER2 scoring between various pathologists or laboratories35 and HER2 status switching within HER2-negative patients during disease development.36 A previous study also suggested that ERBB2 mRNA as a quantitative method could be an alternative evaluation of IHC to better detect patients that might obtain benefits from anti-HER2 ADCs.37

This study had some limitations. First, it was a relatively small subgroup of patients in this retrospective study who were HR-negative/HER2-low, thus any analysis of them was limited. Additional research is required to examine the potential prognostic and predictive biomarkers that might offer a more precise categorization of HER2 than the traditional dichotomous classification. Second, more thorough molecular profiling beyond a specific assay may further dissect the heterogeneity within each breast cancer subtypes.

Conclusions

Our results suggested that HER2-low tumors had unique biological features including clinicopathologic features and gene expression profiles. HR status may influence the prognosis of patients with HER2-low expression to a certain extent, and patients with HR-positive/HER2-low expression may show a favorable survival outcome. In the future, research on HER2-low tumors should be conducted in larger studies to expand the existing limited evidence regarding this new category.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Tianli Hui, Breast Center, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, People’s Republic of China.

Sainan Li, Breast Center, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, People’s Republic of China.

Huimin Wang, State Key Laboratory of Translational Medicine and Innovative Drug Development, Jiangsu Simcere Diagnostics Co., Ltd., Nanjing, People’s Republic of China; Department of Medicine, Nanjing Simcere Medical Laboratory Science Co., Ltd, Nanjing, People’s Republic of China.

Xuejiao Ma, State Key Laboratory of Translational Medicine and Innovative Drug Development, Jiangsu Simcere Diagnostics Co., Ltd., Nanjing, People’s Republic of China; Department of Medicine, Nanjing Simcere Medical Laboratory Science Co., Ltd, Nanjing, People’s Republic of China.

Furong Du, State Key Laboratory of Translational Medicine and Innovative Drug Development, Jiangsu Simcere Diagnostics Co., Ltd., Nanjing, People’s Republic of China; Department of Medicine, Nanjing Simcere Medical Laboratory Science Co., Ltd, Nanjing, People’s Republic of China.

Wei Gao, Breast Center, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, People’s Republic of China.

Shan Yang, Breast Center, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, People’s Republic of China.

Meixiang Sang, Breast Center, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, People’s Republic of China.

Ziyi Li, Breast Center, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, People’s Republic of China.

Ran Ding, State Key Laboratory of Translational Medicine and Innovative Drug Development, Jiangsu Simcere Diagnostics Co., Ltd., Nanjing, People’s Republic of China.

Yueping Liu, Department of Pathology, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, People’s Republic of China.

Cuizhi Geng, Breast Center, The Fourth Hospital of Hebei Medical University, Shijiazhuang, People’s Republic of China.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Program of Hebei Natural Science Foundation for Precision Medicine (H2020206199).

Conflict of Interest

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Y.P.L., C.Z.G. Provision of study material or patients: T.L.H., S.N.L. Collection and/or assembly of data: W.G., S.Y., M.X.S., Z.Y.L., R.D. Data analysis and interpretation: T.L.H., S.N.L., H.M.W., X.J.M., F.R.D. Manuscript writing: T.L.H., S.N.L., H.M.W., X.J.M., F.R.D., Y.P.L., C.Z.G. Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209-249. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumler I, Tuxen MK, Nielsen DL.. A systematic review of dual targeting in HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40(2):259-270. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Slamon DJ, Clark GM, Wong SG, et al. Human breast cancer: correlation of relapse and survival with amplification of the HER-2/neu oncogene. Science. 1987;235(4785):177-182. 10.1126/science.3798106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cronin KA, Harlan LC, Dodd KW, Abrams JS, Ballard-Barbash R.. Population-based estimate of the prevalence of HER-2 positive breast cancer tumors for early stage patients in the US. Cancer Invest. 2010;28(9):963-968. 10.3109/07357907.2010.496759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu B, Yan M, Ma F, et al. Pyrotinib plus capecitabine versus lapatinib plus capecitabine for the treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (PHOEBE): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(3):351-360. 10.1016/s1470-2045(20)30702-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baselga J, Cortes J, Kim SB, et al. ; CLEOPATRA Study Group. Pertuzumab plus trastuzumab plus docetaxel for metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):109-119. 10.1056/NEJMoa1113216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, et al. Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(11):783-792. 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gianni L, Lladó A, Bianchi G, et al. Open-label, phase II, multicenter, randomized study of the efficacy and safety of two dose levels of Pertuzumab, a human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 dimerization inhibitor, in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(7):1131-1137. 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tarantino P, Hamilton E, Tolaney SM, et al. HER2-low breast cancer: pathological and clinical landscape. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(17):1951-1962. 10.1200/JCO.19.02488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolff AC, Hammond ME, Hicks DG, et al. ; American Society of Clinical Oncology. Recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3997-4013. 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.9984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolff AC, Hammond MEH, Allison KH, et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists Clinical Practice Guideline focused update. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(20):2105-2122. 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.8738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schalper KA, Kumar S, Hui P, Rimm DL, Gershkovich P.. A retrospective population-based comparison of HER2 immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization in breast carcinomas: impact of 2007 American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists criteria. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138(2):213-219. 10.5858/arpa.2012-0617-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fehrenbacher L, Cecchini RS, Geyer CE Jr., et al. NSABP B-47/NRG Oncology phase III randomized trial comparing adjuvant chemotherapy with or without trastuzumab in high-risk invasive breast cancer negative for HER2 by FISH and with IHC 1+ or 2. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(5):444-453. 10.1200/JCO.19.01455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Modi S, Park H, Murthy RK, et al. Antitumor activity and safety of trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with HER2-low-expressing advanced breast cancer: results From a Phase Ib study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(17):1887-1896. 10.1200/JCO.19.02318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Banerji U, van Herpen CML, Saura C, et al. Trastuzumab duocarmazine in locally advanced and metastatic solid tumours and HER2-expressing breast cancer: a phase 1 dose-escalation and dose-expansion study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(8):1124-1135. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Modi S, Jacot W, Yamashita T, et al. ; DESTINY-Breast04 Trial Investigators. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(1):9-20. 10.1056/NEJMoa2203690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang G, Ren C, Li C, et al. Distinct clinical and somatic mutational features of breast tumors with high-, low-, or non-expressing human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 status. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):142. 10.1186/s12916-022-02346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hein A, Hartkopf AD, Emons J, et al. Prognostic effect of low-level HER2 expression in patients with clinically negative HER2 status. Eur J Cancer. 2021;155:1-12. 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schettini F, Chic N, Braso-Maristany F, et al. Clinical, pathological, and PAM50 gene expression features of HER2-low breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer. 2021;7(1):1. 10.1038/s41523-020-00208-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tan R, Ong WS, Lee KH, et al. HER2 expression, copy number variation and survival outcomes in HER2-low non-metastatic breast cancer: an international multicentre cohort study and TCGA-METABRIC analysis. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):105. 10.1186/s12916-022-02284-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li Y, Abudureheiyimu N, Mo H, et al. In real life, low-level HER2 expression may be associated with better outcome in HER2-negative breast cancer: a study of the National Cancer Center, China. Front Oncol. 2021;11:774577. 10.3389/fonc.2021.774577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Denkert C, Seither F, Schneeweiss A, et al. Clinical and molecular characteristics of HER2-low-positive breast cancer: pooled analysis of individual patient data from four prospective, neoadjuvant clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(8):1151-1161. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cheng SH, Horng CF, Huang TT, et al. An eighteen-gene classifier predicts locoregional recurrence in post-mastectomy breast cancer patients. EBioMedicine. 2016;5:74-81. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Huang TT, Chen AC, Lu TP, Lei L, Cheng SH.. Clinical-genomic models of node-positive breast cancer: training, testing, and validation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;105(3):637-648. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2019.06.2546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cheng SH, Horng CF, West M, et al. Genomic prediction of locoregional recurrence after mastectomy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(28):4594-4602. 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.5676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang L, Zhou M, Liu Y, et al. Is it beneficial for patients with pT1-2N1M0 breast cancer to receive postmastectomy radiotherapy? An analysis based on RecurIndex assay. Int J Cancer. 2021;149(10):1801-1808. 10.1002/ijc.33730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nielsen TO, Leung SCY, Rimm DL, et al. Assessment of Ki67 in breast cancer: updated recommendations from the International Ki67 in Breast Cancer Working Group. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(7):808-819. 10.1093/jnci/djaa201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Almstedt K, Heimes AS, Kappenberg F, et al. Long-term prognostic significance of HER2-low and HER2-zero in node-negative breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2022;173:10-19. 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Berrino E, Annaratone L, Bellomo SE, et al. Integrative genomic and transcriptomic analyses illuminate the ontology of HER2-low breast carcinomas. Genome Med. 2022;14(1):98. 10.1186/s13073-022-01104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Agostinetto E, Rediti M, Fimereli D, et al. HER2-low breast cancer: molecular characteristics and orognosis. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(11):2824-2840. 10.3390/cancers13112824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van den Ende NS, Smid M, Timmermans A, et al. HER2-low breast cancer shows a lower immune response compared to HER2-negative cases. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):12974. 10.1038/s41598-022-16898-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mutai R, Barkan T, Moore A, et al. Prognostic impact of HER2-low expression in hormone receptor positive early breast cancer. Breast. 2021;60:62-69. 10.1016/j.breast.2021.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhang H, Katerji H, Turner BM, Audeh W, Hicks DG.. HER2-low breast cancers: incidence, HER2 staining patterns, clinicopathologic features, MammaPrint and BluePrint genomic profiles. Mod Pathol. 2022;35(8):1075-1082. 10.1038/s41379-022-01019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jacot W, Maran-Gonzalez A, Massol O, et al. Prognostic value of HER2-low expression in non-metastatic triple-negative breast cancer and correlation with other biomarkers. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(23):6059-6071. 10.3390/cancers13236059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ballinger TJ, Sanders ME, Abramson VG.. Current HER2 testing recommendations and clinical relevance as a predictor of response to targeted therapy. Clin Breast Cancer. 2015;15(3):171-180. 10.1016/j.clbc.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Miglietta F, Griguolo G, Bottosso M, et al. Evolution of HER2-low expression from primary to recurrent breast cancer. npj Breast Cancer. 2021;7(1):137. 10.1038/s41523-021-00343-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Griguolo G, Braso-Maristany F, Gonzalez-Farre B, et al. ERBB2 mRNA expression and response to ado-trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in HER2-positive breast cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(7):1902. 10.3390/cancers12071902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.