Abstract

GABA and glycine are major inhibitory neurotransmitters in the CNS and act on receptors coupled to chloride channels. During early developmental periods, both GABA and glycine depolarize membrane potentials due to the relatively high intracellular Cl− concentration. Therefore, they can act as excitatory neurotransmitters. GABA and glycine are involved in spontaneous neural network activities in the immature CNS such as giant depolarizing potentials (GDPs) in neonatal hippocampal neurons, which are generated by the synchronous activity of GABAergic interneurons and glutamatergic principal neurons. GDPs and GDP-like activities in the developing brains are thought to be important for the activity-dependent functiogenesis through Ca2+ influx and/or other intracellular signaling pathways activated by depolarization or stimulation of metabotropic receptors. However, if GABA and glycine do not shift from excitatory to inhibitory neurotransmitters at the birth and in maturation, it may result in neural disorders including autism spectrum disorders.

Keywords: GABA, Glycine, Giant depolarizing potentials, Activity dependent functiogenesis

The subject of this review is the depolarizing and excitatory effects of GABA and glycine in the developing hippocampus and other CNSs.

GABAA receptors and strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors are ligand-gated chloride ion channels that belong to the Cys-loop pentameric ligand-gated ion channels (LGIC) superfamily, which also includes nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and 5-HT3 receptors [1]. Since the equilibrium potential of chloride ions is usually more negative than the threshold of action potentials, GABA and glycine are regarded as major inhibitory neurotransmitters in the adult CNS. However, in the 1960s, Obata and colleagues [2, 3] reported that GABA and glycine were excitatory in embryonic chick spinal neurons.

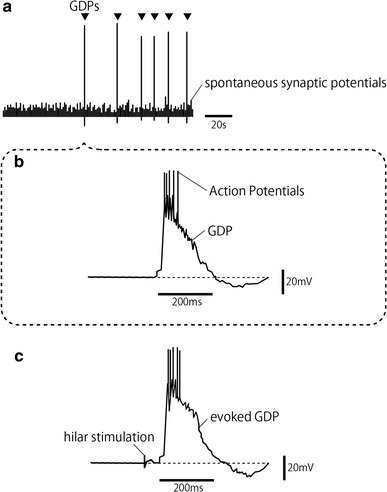

The first studies that gathered attention regarding the importance of GABA as an excitatory neurotransmitter in the developing CNS included a paper by Ben-Ari et al. in 1989 [4] and a subsequent short but comprehensive review in 1991 [5]. They [4] studied immature rat hippocampal CA3 neurons and found giant depolarizing potentials (GDPs), which were concluded to be primarily driven by synchronous pulsatile activity of GABAergic neurons. GDPs consist of low frequency pulsatile activity (between 0.005 and 0.2 Hz) when measured using intracellular recording in CA3 neurons (Fig. 1a). GDP begins with a rather steep depolarization lasting several hundred milliseconds and several concomitant action potentials, and is usually followed by hyperpolarization (Fig. 1b). Interestingly, stimulation of the hilus can evoke a large depolarization (evoked GDP) that is nearly identical to spontaneous GDPs (Fig. 1c). Even though GDPs have been shown to be primarily driven by GABA and completely blocked by specific GABAA receptor blocker bicuculline, antagonists for NMDA receptors also block spontaneous and evoked GDPs, suggesting that glutamatergic activity contributes to GDPs through the NMDA receptor. AMPA-type glutamate receptors have also been shown to act in GDP generation [6], and GDPs are thought to be generated by the synergistic action of GABA and glutamate. GDPs disappeared early in the second postnatal week, though spontaneous hyperpolarizing potentials, similar to GDPs in duration and frequency, were sometimes observed at the beginning of the second postnatal week.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of a recording of GDPs in an immature rat hippocampal CA3 neuron. a GDPs are seen as large depolarizing events among GABAergic spontaneous synaptic potentials. GDPs are GABA-mediated spontaneous pulsatile depolarizing events that occur at a frequency of 0.005–0.2 Hz. b A typical GDP rises abruptly concomitant with several action potentials, decays within 200–300 ms, and is followed by transient hyperpolarization. c Electrical stimulation at the hilus evokes a depolarizing event similar to a GDP after a stimulus intensity dependent short latency

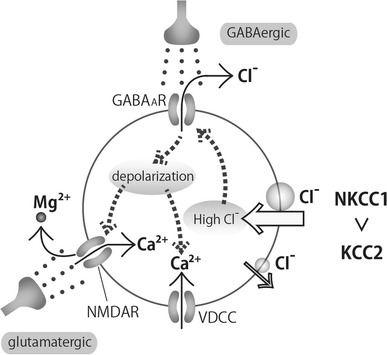

NMDA receptors are thought to be important in developing CNS. They are often present at silent synapses, in which other types of glutamatergic ionotropic receptors are absent [7] or presynaptic glutamate release is insufficient to activate them [8]. NMDA receptors have three important characteristics [9]. First, they can pass Ca2+ as well as Na+ and K+. Second, they cannot be opened by glutamate unless the Mg2+ block is removed by sufficient depolarization. Thus, NMDA receptors work as “AND-gates” for GABAergic depolarization and glutamatergic stimulation causing Ca2+ influx as outputs (Fig. 2). Synchronized activation of GABAergic and glutamatergic input in GDPs and GDP-like network activity have been shown to increase intracellular Ca2+ and potentiate connectivity in neural circuits in several regions of CNS [10, 11]. Third, they require glycine as co-agonist of glutamate, though a relatively low concentration of glycine is sufficient. Gaïarsa and colleagues showed that glycine can modulate GDP network activity by binding to the glycine binding site on the NMDA receptor in a strychnine insensitive manner [12, 13].

Fig. 2.

Ca2+ influx by GABAergic neural inputs in an immature neuron in immature neurons, NKCC1 is more active than KCC2 and intracellular Cl− concentration is maintained at a relatively high level. GABA released from GABAergic interneurons opens GABAA receptor Cl− channels and Cl− efflux results in the depolarization of the neuron. Depolarization opens voltage dependent calcium channels (VDCC) and removes bound Mg2+ from NMDA receptors, resulting in Ca2+ influx through VDCCs and glutamate-activated NMDA receptors. (The glycine binding site on NMDA receptors has been omitted)

GDP network activity is, in a sense, quite robust. It can be seen, as originally observed, in hippocampal slice preparation and it has been observed in vivo in hippocampus using extracellular recordings as “sharp waves” [14]. In addition, it can be seen in cultured neuron clusters [15] and organotypic slice cultures [16]. Furthermore, GDPs can be seen in small portions of sectioned slices of the hippocampus [17]. Using rat neonatal slice preparations containing both hippocampi and medial septa, Leinekugel et al. [17] showed that the GDPs from the temporal portion of the left and the right hippocampus and the septa were synchronized to the GDPs at the septal portion of hippocampi with a slight delay. The separated septum alone cannot generate GDPs whereas a small section of a hippocampus can still generate GDPs. The frequency of GDPs in temporal portion of a hippocampal slice greatly decreases, when separated from the septal portion of hippocampus, whereas the frequency in the septal portion remains unchanged. From these observations and other studies [14, 18], GDPs are thought to be initiated in the hippocampal CA3 region near the septum by relatively small clusters of neurons. Afterwards, the GDPs synchronously propagate to both hippocampi, spread to the septum, and then spread farther in the limbic system.

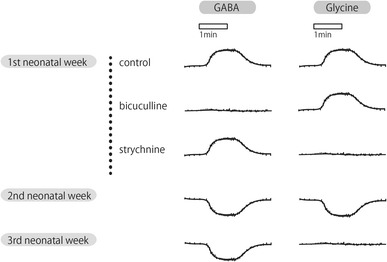

Although the role of glycine as a neurotransmitter in forebrain seems to be quite limited, in the adult CNS, the expression of functional glycine receptors has been found almost everywhere in the developing brain [19, 20]. In 1991, Ito and Cherubini found strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors in rat hippocampal CA3 neurons in the first postnatal week [21]. The postsynaptic cell response to glycine was quite similar to its response to GABA. It is excitatory during the first neonatal week and the reversal potential is identical to that of GABA. The polarity changes from depolarization to hyperpolarization early in the second postnatal week. However, the response to glycine disappears at the end of the second postnatal week, whereas the response to GABA persists in adult neurons (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Schematic membrane potential responses of rat neonatal CA3 neurones to GABA and glycine bath application of GABA and glycine lead to quite identical responses on neonatal CA3 neurone in the presence of TTX, except that GABA and glycine were specifically antagonized by bicuculline and strychnine, respectively, and glycine response disappeared in the 3rd neonatal week. Responses changed polarity from depolarization to hyperpolarization between the 1st and the 2nd postnatal weeks, despite the resting membrane potential remaining unchanged at approximately −65 mV

In addition to GDPs, spontaneous postsynaptic potentials (SPSPs) are also seen in neonatal CA3 neurons (Fig. 1a). Hosokawa et al. [22] studied these SPSPs and showed that SPSPs during the first postnatal week are mainly GABAergic despite being excitatory and that glutamatergic SPSPs are scarce. GABAergic SPSPs shift from depolarizing to hyperpolarizing at the end of the first neonatal week concomitant with the disappearance of GDPs and the gradual increase of glutamatergic excitatory SPSPs. Interestingly, Safiulina et al. observed [23] that the frequency of SPSPs becomes significantly higher prior to the onset of each GDP.

The depolarizing and excitatory effects of GABA and glycine are seen throughout the developing CNSs in various vertebrates, as summarized in the review by Ben-Ari et al. [24]. However, Bregestovski and Bernard raised several questions about the excitatory effects of GABA and glycine in the developing brain [25]. They discussed the possibility that pathologically high intracellular Cl− concentration in in vitro artificial conditions result in misleading excitatory activity including GDPs. Their arguments were immediately refuted by Ben-Ari et al. [26], and it is improbable that all GDPs and GDP-like activities including in vivo observations are mere artefacts. We must still be aware that GDPs in the slice preparation may not accurately represent occurrences in the hippocampus of intact neonates.

The role of extra-synaptic receptors and the tonic effects of their agonists have been studied during the developmental period [27–31] and have been shown to modulate neural network activities including GDP. Tonic effects of agonists on extra-synaptic receptors can be revealed by a shift in the resting membrane potential, or tonic current in a voltage clamp, by specific antagonists and, especially, by specific uptake blockers of putative agonists. Naturally, GABA and glycine have been shown to be tonic agonists on GABAA and glycine receptors [26–28]. In addition, taurine and β-alanine are proposed to be tonic glycine receptor agonists because they are abundant in the extracellular environment and the uptake blocker of taurine potentiates glycine receptor-mediated tonic effects [30, 31].

Excitatory responses to GABA and glycine in immature neurons are explained by the relatively high intracellular Cl− concentration. As shown in Fig. 2, the intracellular Cl− concentration is regulated mainly by two cation-chloride cotransporters, NKCC1 and KCC2 [32]. NKCC1 imports Cl− whereas KCC2 extrudes intracellular Cl−. In addition, a relatively lower expression of KCC2 is thought to cause a high intracellular Cl− concentration in developing neurons [33, 34]. Thus, the reversal potential of Cl− is kept higher than the resting membrane potential and an efflux of Cl− through receptor chloride channels activated by GABA or glycine causes a depolarizing response. It must be emphasised that the intracellular concentration of Cl− is actively controlled with considerable energy cost when the reversal potential differs from the membrane potential.

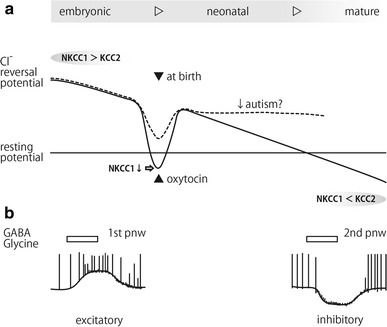

The intracellular Cl− concentration gradually decreases during the early developmental period due to changes in the balance of activities of NKCC1 and KCC2 [35], whereas the resting potential remains relatively constant (Fig. 4a). In the case of rat CA3 neurons, the shift from depolarization to hyperpolarization (D/H shift) occurs at the end of the first postnatal week [4, 21]. Tyzio and colleagues found an amazing phenomenon in mouse hippocampal and cortical neurons that occurs at birth (Fig. 4a) [36]. Although GABAergic response is excitatory both in the embryonic and early postnatal periods, it transiently shifts to inhibitory at birth. This shift was found to be caused by maternal oxytocin which crosses the placenta, blocks NKCC1 and results in a lower intracellular Cl− concentration. They hypothesized that this transient D/H shift works by calming down neural activity, and that it protects the immature brain from harmful stress such as excessive catecholamine release during delivery.

Fig. 4.

The time course of the change in neural intracellular Cl− concentration during early developmental periods. a During the embryonic and early neonatal periods, NKCC1 is more active than KCC2 and the reversal potential for Cl− is maintained above the resting potential. However, at the birth, maternal oxytocin acts on the fetal neurons and suppresses NKCC1 activity resulting in a transient hyperpolarizing shift of Cl− reversal potential. After birth, KCC2 becomes gradually more active than NKCC1 and the Cl− reversal potential finally becomes more negative than the resting potential. Failure of sufficient oxytocin action at birth has been suggested to be a cause of pathological conditions such as autism spectrum disorders. b Responses to GABA and glycine change from excitatory to inhibitory between the 1st and the 2nd postnatal weeks due to the increase of intracellular Cl− concentration

A transient D/H shift during delivery and a gradual decrease of intracellular Cl− after birth were found to be impaired in autism models in rodents [37]. Pre-treatment with bumetanide, a specific NKCC1 blocker, can improve symptoms of autism by lowering intracellular Cl−. While oxytocin itself has been recently tested as a treatment for autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) [38–40], trials of bumetanide for ASD patients are now ongoing with some significantly positive results [41, 42].

In conclusion, spontaneous synaptic events including SPSPs and GDP-like activity work to refine neural networks, and the tonic effects of agonists on extra-synaptic receptors in the microenvironment control the excitability of neurons. Both are the most important mechanisms for activity-dependent morphogenesis and functiogenesis in which GABA and glycine play major roles. On the other hand, failure of a shift to inhibitory at the appropriate timing causes pathological problems of the brain function.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Prof. Enrico Cherubini for his valuable remarks and suggestions. I am also grateful to Miss Keiko Narazaki for help in preparation of figures.

Abbreviations

- AMPA

α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid

- ASD

Autism spectrum disorder

- CA3

Cornu ammonis area 3

- CNS

Central nervous system

- GABA

γ-Aminobutyric acid

- GDP

Giant depolarizing potential

- KCC2

Potassium chloride cotransporter 2

- NKCC1

Sodium potassium chloride cotransporter 1

- NMDA

N-methyl-d-aspartate

- SPSP

Spontaneous postsynaptic potential

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M, Peters JA, Harmar AJ. The concise guide to pharmacology 2013/14: ligand-gated ion channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;170:1582–1606. doi: 10.1111/bph.12446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Obata K. Transmitter sensitivities of some nerve and muscle cells in culture. Brain Res. 1974;73:71–88. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(74)91008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obata K, Oide M, Tanaka H. Excitatory and inhibitory actions of GABA and glycine on embryonic chick spinal neurons in culture. Brain Res. 1978;144:179–184. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(78)90447-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ben-Ari Y, Cherubini E, Corradetti R, Gaïarsa JL. Giant synaptic potentials in immature rat CA3 hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. 1989;416:303–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cherubini E, Gaïarsa JL, Ben-Ari Y. GABA: an excitatory transmitter in early postnatal life. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:515–519. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90003-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolea S, Avignone E, Berretta N, Sanchez-Andres JV, Cherubini E. Glutamate controls the induction of GABA-mediated giant depolarizing potentials through AMPA receptors in neonatal rat hippocampal slices. J Neurophysiol. 1999;81:2095–2102. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.5.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Durand GM, Kovalchuk Y, Konnerth A. Long-term potentiation and functional synapse induction in developing hippocampus. Nature. 1996;381:71–75. doi: 10.1038/381071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gasparini S, Saviane C, Voronin LL, Cherubini E. Silent synapses in the developing hippocampus: lack of functional AMPA receptors or low probability of glutamate release? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9741–9746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170032297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanke ML, Van Dongen AMJ. Activation mechanisms of the NMDA receptor. In: Van Dongen AMJ, editor. Biology of the NMDA receptor. Boca Raton: CRC; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasyanov AM, Safiulina VF, Voronin LL, Cherubini E. GABA-mediated giant depolarizing potentials as coincidence detectors for enhancing synaptic efficacy in the developing hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3967–3972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305974101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohajerani MH, Cherubini E. Role of giant depolarizing potentials in shaping synaptic currents in the developing hippocampus. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2006;18:13–23. doi: 10.1615/CritRevNeurobiol.v18.i1-2.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaïarsa JL, Corradetti R, Cherubini E, Ben-Ari Y. The allosteric glycine site of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor modulates GABAergic-mediated synaptic events in neonatal rat CA3 hippocampal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:343–346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaïarsa JL, Corradetti R, Cherubini E, Ben-Ari Y. Modulation of GABA-mediated synaptic potentials by glutamatergic agonists in neonatal CA3 rat hippocampal neurons. Eur J Neurosc. 1991;3:301–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00816.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leinekugel X, Khazipov R, Cannon R, Hirase H, Ben Ari Y, Buzsaki G. Correlated bursts of activity in the neonatal hippocampus in vivo. Science. 2002;296:2049–2052. doi: 10.1126/science.1071111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voigt T, Opitz T, De Lima AD. Synchronous oscillatory activity in immature cortical network is driven by GABAergic preplate neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8895–8905. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-08895.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohajerani MH, Cherubini E. Spontaneous recurrent network activity in organotypic rat hippocampal slices. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:107–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leinekugel X, Khalilov I, Ben-Ari Y, Khazipov R. Giant depolarizing potentials: the septal pole of the hippocampus paces the activity of the developing intact septohippocampal complex in vitro. J Neurosci. 1998;18:6349–6357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06349.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menendez de la Prida L, Sanchez-Andres JV. Heterogenous populations of cells mediate spontaneous synchronous bursting in the developing hippocampus through a frequency-dependent mechanism. Neuroscience. 2000;97:227–241. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(00)00029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bets H. Glycine receptors: heterogeneous and widespread in the mammalian brain. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:458–461. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90045-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avila A, Nguyen L, Rigo JM. Glycine receptors and brain development. Front Cell Neurosci. 2013;7:184. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2013.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ito S, Cherubini E. Strychnine sensitive glycine responses of neonatal rat hippocampal neurones. J Physiol. 1991;440:67–83. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1991.sp018696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosokawa Y, Sciancalepore M, Stratta F, Martina M, Cherubini E. Developmental changes in spontaneous GABAA-mediated synaptic events in rat hippocampal CA3 neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 1994;6:805–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1994.tb00991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cherubini E, Griguoli M, Safiulina V, Lagostena L. The depolarizing action of GABA controls early network activity in the developing hippocampus. Mol Neurobiol. 2011;43:97–106. doi: 10.1007/s12035-010-8147-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ben-Ari Y, Gaïarsa JL, Tyzio R, Khazipov R. GABA: a pioneer transmitter that excites immature neurons and generates primitive oscillations. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1215–1284. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bregestovski P, Bernard C. Excitatory GABA: how a correct observation may turn out to be an experimental artifact. Front Pharmacol. 2012;3:65. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2012.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ben-Ari Y, WoodinM A, Sernagor E, Cancedda L, Vinay L, Rivera C, Legendre P, Luhmann HJ, Bordey A, Wenner P, Fukuda A, vad den Pol AN, Gaïarsa JL, Cherubini E. Refuting the challenges of the developmental shift of polarity of GABA actions: GABA more exciting than ever! Front Cell Neurosci. 2012;6:1–18. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2012.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marchionni I, Omrani A, Cherubini E. In the developing rat hippocampus a tonic GABAA-mediated conductance selectively enhances the glutamatergic drive of principal cells. J Physiol. 2007;581:515–528. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gomeza J, Hülsmann S, Koji Ohno, Eulenburg V, Szöke K, Richter D, Betz H. Inactivation of the glycine transporter 1 gene discloses vital role of glial glycine uptake in glycinergic inhibition. Neuron. 2003;40:785–796. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00672-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sipila ST, Spoljaric A, Virtanen MA, Hiironniemi I, Kaila K. Glycine transporter-1 controls nonsynaptic inhibitory actions of glycine receptors in the neonatal rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2014;34:10003–10009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0075-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mori M, Gähwiler BH, Gerber U. β-alanine and taurine as endogenous agonists at glycine receptors in rat hippocampus in vitro. J Physiol. 2002;539:191–200. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen R, Okabe A, Sun H, Sharopov S, Hanganu-Opatz IL, Kolbaev SN, Fukuda A, Luhmann HJ, Kilb W. Activation of glycine receptors modulates spontaneous epileptiform activity in the immature rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2014;592:2153–2168. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.271700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaila K, Price TJ, Payne JA, Puskarjov M, Voipio J. Cation-chloride cotransporters in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:637–654. doi: 10.1038/nrn3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang C, Shimizu-Okabe C, Watanabe K, Okabe A, Matsuzaki H, Ogawa T, Mori N, Fukuda A, Sato K. Developmental changes in KCC1, KCC2, and NKCC1 mRNA expressions in the rat brain. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;139:59–66. doi: 10.1016/S0165-3806(02)00536-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamada J, Okabe A, Toyoda H, Kilb W, Luhmann HJ, Fukuda A. Cl− uptake promoting depolarizing GABA actions in immature rat neocortical neurones is mediated by NKCC1. J Physiol. 2004;557:829–841. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.062471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rivera C, Voipio J, Payne JA, Ruusuvuori E, Lahtinen H, Lamsa K, Pirvola U, Saarma M, Kaila K. The K/Cl− co-transporter KCC2 renders GABA hyperpolarizing during neuronal maturation. Nature. 1999;397:251–255. doi: 10.1038/16697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tyzio R, Cossart R, Khalilov I, Minlebaev M, Hubner CA, Represa A, Ben-Ari Y, Khazipov R. Maternal oxytocin triggers a transient inhibitory switch in GABA signaling in the fetal brain during delivery. Science. 2006;314:1788–1792. doi: 10.1126/science.1133212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tyzio R, Nardou R, Ferrari DC, Tsintsadze T, Shahrokhi A, Eftekhari S, Khalilov I, Tsintsadze V, Brouchoud C, Chazal G, Lemonnier E, Lozovaya N, Burnashev N, Ben-Ari Y. Oxytocin-mediated GABA inhibition during delivery attenuates autism pathogenesis in rodent offspring. Science. 2014;343:675–679. doi: 10.1126/science.1247190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hollander E, Bartz J, Chaplin W, Phillips A, Sumner J, Soorya L, Anagnostou E, Wasserman S. Oxytocin increases retention of social cognition in autism. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gordon I, Wyk BCV, Bennett RH, Cordeaux C, Lucas MV, Eilbott JA, Zagoory-Sharon O, Leckman JF, Feldman R, Pelphrey KA. Oxytocin enhances brain function in children with autism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(52):20953–20958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312857110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watanabe T, Mi Kuroda, Kuwabara H, Aoki Y, Iwashiro N, Tatsunobu N, Takao H, Nippashi Y, Kawakubo Y, Kunimatsu A, Kasai K, Yamasue H. Clinical and neural effects of six-week administration of oxytocin on core symptoms of autism. Brain. 2015;138:3400–3412. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lemonnier E, Degrez C, Phelep M, Tyzio R, Josse F, Grandgeorge M, Hadjikhani N, Ben-Ari Y. A randomised controlled trial of bumetanide in the treatment of autism in children. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e202. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Curatolo P, Ben-Ari Y, Bozzi Y, Catana MV, D’Angelo E, Mapelli L, Oberman LM, Rosenmund C, Cherubini E. Synapses as therapeutic targets for autism spectrum disorders: an international symposium held in Pavia on July 4th. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8309:309. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]