Abstract

Objective:

To examine the effect of digital health interventions (DHIs) compared to treatment as usual (TAU) on preventing and treating postpartum depression (PPD) and postpartum anxiety (PPA).

Data Sources:

Searches in Ovid Medline, Embase, SCOPUS, Cochrane Database, and ClinicalTrials.gov for randomized controlled trials comparing DHIs to TAU for preventing or treating PPD and PPA. The primary outcome was the score on the first ascertainment of PPD or PPA symptoms after the intervention. Secondary outcomes included screening positive for PPD or PPA—as defined in the primary study—and loss to follow-up, defined as the proportion of participants who completed the final study assessment compared to the number who were initially randomized.

Methods of Study Selection:

Two authors independently screened all abstracts for eligibility and independently reviewed all potentially eligible full-text articles for inclusion. A third author screened abstracts and full-text articles as needed to determine eligibility in cases of discrepancy. For continuous outcomes, the Hedges method was used to obtain standardized mean differences (SMD) when the studies used different psychometric scales, and weighted mean differences (WMD) were calculated when studies used the same psychometric scales. For categorical outcomes, pooled relative risks (RR) were estimated.

Tabulation, Integration, and Results:

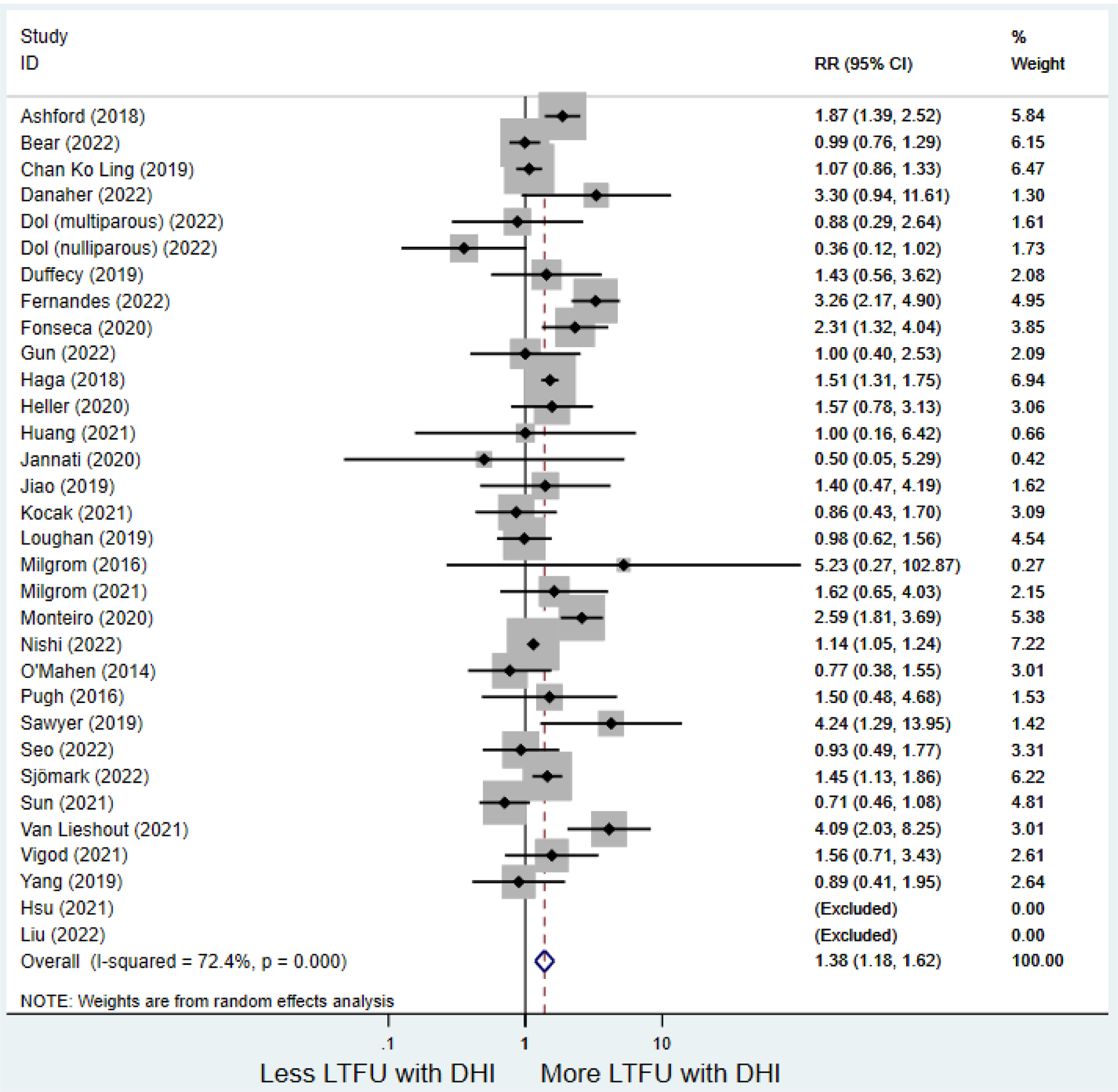

Of 921 studies originally identified, 31 randomized controlled trials—corresponding to 5,532 participants randomized to DHI and 5,492 participants randomized to TAU—were included. Compared to TAU, DHIs significantly reduced mean scores ascertaining PPD symptoms (29 studies: SMD −0.64 (95% Confidence Interval (CI): −0.88, −0.40), I2= 94.4%) and PPA symptoms (17 studies: SMD −0.49 (95% CI: −0.72, −0.25) ), I2= 84.6%). In the few studies that assessed screen-positive rates for PPD (n=4) or PPA (n=1), there was no significant differences between those randomized to DHI versus TAU. Overall, those randomized to DHI had 38% increased risk of not completing the final study assessment compared to those randomized to TAU (pooled RR 1.38 (95% CI 1.18, 1.62), but those randomized to app-based DHI had similar loss-to-follow-up rates as those randomized to TAU (RR 1.04 (95% Confidence Interval: 0.91, 1.19)).

Conclusion:

DHIs modestly, but significantly, reduced scores assessing PPD and PPA symptoms. More research is needed to identify DHIs that effectively prevent or treat PPD and PPA but encourage ongoing engagement throughout the study period.

Keywords: digital health intervention, postpartum depression, postpartum anxiety, perinatal mental health, smartphone application, internet, text message

Tweetable statement:

In a meta-analysis of RCTs, digital interventions modestly but significantly reduced symptoms of postpartum depression and anxiety but had higher risk of loss-to-follow up compared to routine care.

Introduction

In the year after childbirth, approximately 15% of women experience postpartum depression (PPD)1 and 20% experience postpartum anxiety (PPA).2 Prior studies have demonstrated that interventions utilizing psychoeducation3 or psychotherapy (cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT),4 interpersonal therapy (IPT),5 or mindfulness6) effectively prevent and treat PPD and PPA. Unfortunately, less than 20% of women with PPD or PPA have access to these interventions.7 The inadequate dissemination of programs shown to improve perinatal mental health has been attributed to the limited number of skilled mental health professionals who can provide psychoeducation or psychotherapy in the perinatal period.8

Digital health interventions (DHIs) may help expand access to evidence-based psychoeducation or psychotherapy-based perinatal mental health programs. Though the World Health Organization defines DHIs broadly as “a discrete functionality of digital technology that is applied to achieve health objectives,”9, DHIs may be defined pragmatically as interventions delivered directly to a patient via the internet, a smartphone application (app), or a text message or short-message system (SMS) program. DHIs have notable advantages when compared to in-person interventions. First, they are accessible to nearly all who reside in the United States: smartphone ownership rates are nearly universal among reproductive-aged patients (95% of individuals aged 18–49 years own a smartphone),10 and most households (77%)—even low-income (57%)11 or rural households (72%)12—have broadband internet at home.11, 12Second, DHIs bypass barriers such as lack of childcare or unreliable transportation that have been associated with reduced adherence to in-person postpartum care.13, 14 Lastly, DHIs are inherently scalable: once proven effective, DHIs can be widely disseminated without reducing intervention fidelity.

Prior meta-analyses have suggested that DHIs effectively improve PPD or PPA when compared to treatment as usual in randomized controlled trials.15–18 However, these meta-analyses have limitations: most only included internet-based DHIs,16–18 and the only meta-analysis that included multiple DHI modalities focused exclusively on the effect of DHIs on PPD15 despite the significant burden of PPA on perinatal populations. In addition, nine randomized controlled trials comparing DHIs to treatment as usual (TAU) have been published since 2021.19–27 Thus, an updated meta-analysis is warranted. The primary aim of this study is to assess the effect of DHIs compared to TAU on preventing or treating PPD and PPA. Secondary aims included assessing the effect of DHIs compared to TAU on treating PPD and PPA overall and the effect of specific DHI modalities on PPD and PPA prevention or treatment.

Methods

Sources

All written methodologies, including search strategies, used in this systematic review and meta-analysis were created according to standards and guidelines for conducting and reporting systematic reviews set forth by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA),28 the Peer Review Systematic Search Strategies (PRESS),29 the Institute for Medicine Standards for Systematic Reviews,30 and the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews.31 This study was registered on PROSPERO (#CRD42022321649) prior to data abstraction and exempt from institutional board review as only deidentified data derived from prior publications were included.

A medical librarian (A.H.) searched published literature for records discussing postpartum depression, anxiety, or distress and digital or mobile health interventions in pregnant or postpartum people. The librarian created search strategies using a combination of controlled vocabulary and keywords in Ovid Medline 1946-, Embase 1947-, Scopus 1823-, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and Clinicaltrials.gov 1997-. The search was initially completed in October 2021 and was re-executed in December 2022. Appendix 1describes reproducible search strategies for each database.

Study selection

Two co-authors (A.K.L and A.R.W) independently screened all titles and abstracts before jointly reviewing their individual selection of potentially eligible abstracts. Disagreements on potential eligibility were resolved with discussion with a third author (N.K.A.). A.K.L and A.R.W then independently reviewed all full-text articles for inclusion, with N.K.A determining final eligibility in cases of discrepancy. Review articles, case reports or series, abstracts, articles published in languages other than English, and studies without a comparison group or without outcomes of interest were excluded. Randomized trials comparing any perinatal digital health intervention to TAU, defined as routine care, were included. We also reviewed the bibliographies of included studies to identify additional eligible studies not identified in our search of the literature.

Data abstraction

Two authors (A.K.L and A.R.W.) independently reviewed eligible articles for data abstraction using a data abstraction tool (Appendix 2). The primary outcome was the score obtained on the first postpartum ascertainment after intervention delivery or randomization of depressive or anxiety symptoms using any psychometric scales that screen for PPD or PPA. For the secondary psychological outcomes, only studies that assessed PPD or PPA via the most commonly utilized psychometric scale for PPD (Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)32) and for PPA (Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)33) were included. Other secondary outcomes included screening positive at any postpartum assessment for depression or anxiety—as defined in the primary study—and loss to follow-up, defined as the proportion of participants who completed the final study assessment compared to the number who were initially randomized.

The same two reviewers also assessed the quality of each study using a prespecified criteria adapted from the Cochrane Handbook31 in a system of classification previously utilized.34–36 High-quality studies were defined as trials with appropriate randomization methods, clear definitions of primary outcomes, and intention-to-treat analyses. Lower-quality studies were those missing at least one of these attributes.34–36 In instances that a study did not include sufficient data to judge an attribute, that attribute was categorized as missing. Disagreement on study quality classification were resolved by discussion with a third author (N.K.A.).

Data synthesis and assessment of risk of bias

All statistical analyses were performed with the METAN package in STATA 16.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Heterogeneity between studies was assessed using the Cochrane’s Q and Higgins I2 tests.31 Heterogeneity was deemed to be significant based on conservative thresholds of Q > df for the Q tests or I2 > 30%.31 Raw data from each study were pooled. For continuous outcomes, the Hedges method was used to obtain standardized mean differences (SMD) when the studies used different psychometric scales, weighted mean differences (WMD) were calculated when studies used the same psychometric scales. For categorical outcomes, pooled relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using raw data from each study. To account for clinical heterogeneity between studies and to produce a more conservative estimate of effect size,37 data were pooled using the DerSimonian-Laird random-effects models regardless of evidence of statistical heterogeneity. For the primary outcomes (PPD and PPA), we also calculated 95% prediction intervals (PI) to determine the potential effect size of a new study if this study were selected at random from the same population of studies currently included in our meta-analysis.38

We conducted pre-specified stratified analyses to assess whether the effect of the digital health intervention was altered by study quality, developed versus developing country setting, or type of digital health intervention. These analyses were based on study quality (higher- versus lower-quality), location of study completion (developed versus developing country, as categorized by the United Nations 2022 World Economic Situation and Prospects document39), or route of digital health intervention delivery (online/internet versus TAU; app versus TAU; and text message/SMS versus TAU). In addition, we conducted stratified analyses based on: (1) whether the study population was restricted to those who screened positive for PPD or PPA per study criteria (i.e., either via a prespecified score on a PPD or PPA psychometric scale or self-reported depression or anxiety symptoms) or who were diagnosed with depression via formal psychological interview prior to randomization; and (2) the type of intervention delivered digitally (psychotherapy—defined as CBT, IPT, or mindfulness—or psychoeducation, with or without peer support; the study that provided peer support alone40 was analyzed individually).

Publication bias was assessed visually using a funnel plot, while the Egger’s test statistically assessed symmetry.41

Pooled Results

Study Selection

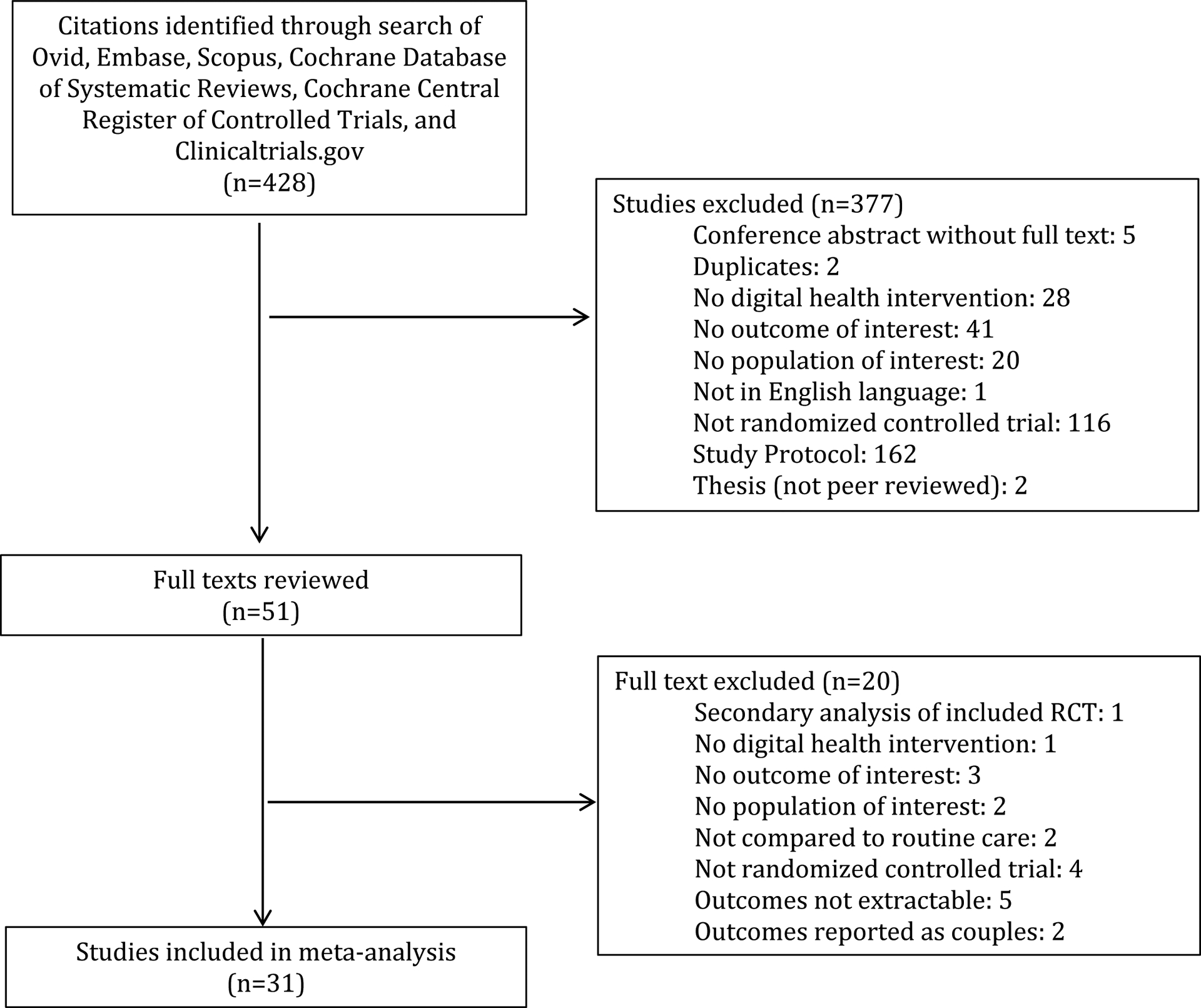

The literature search including ClinicalTrials.gov yielded a total of 921 citations. 453 duplicate citations were removed using the automatic duplicate finder in Endnote, and an additional 40 duplicates identified in both the original and updated search were removed (Figure 1). The titles and abstracts for each of the remaining 428 citation were reviewed for relevance and screened against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Most studies were excluded because they were not a randomized controlled trial (116 studies) or were a published study protocol (162 studies). Ultimately, 51 full texts were reviewed. Of these, 20 were excluded, most commonly because data were un-abstractable due to being presented as the change between psychometric scores at baseline and at first post-randomization assessment but without the actual scores (5 studies) or the study was described as a randomized trial but employed a different study design (4 studies) or lacked outcomes of interest (3 studies). Thus, 31 studies were included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 1:

Flow Diagram for Study Selection

Study Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of included studies are described in Table 1. All 31 studies were randomized trials published as full-text manuscripts. One study dichotomized analyzes by parity (nulliparous and multiparous)21; data from this study were abstracted independently and presented in the forest plots as “Dol: nulliparous” and “Dol: multiparous” and was therefore counted as two studies in our analyses. Two studies were three-group randomized trials (in Jiao et al’s study,42 the three groups were: web-based psychoeducation, home-based psychoeducation, and TAU; for Milgrom et al’s study43, the three groups were: web-based CBT, in-person CBT, and TAU). Per methodological strategies described in prior meta-analyses,34, 35 data from the DHI group and the TAU group were abstracted for these two studies and compared. Among the 31 studies, 20 were deemed to be of higher-quality,21, 22, 25, 27, 42–57 and 11 were lower-quality.19, 20, 23, 24, 26, 40, 58–62 The reason that a study was designated as lower quality is described in Table 1. 24 studies were conducted in developed countries19–22, 25–27, 42, 43, 45–53, 55, 56, 58–60, 62; only seven were conducted in developing countries.23, 24, 40, 44, 54, 57, 61 The route of delivery for the DHI varied between studies: 19 studies utilized an online or internet-based intervention,20, 22, 24, 27, 40, 42, 43, 45–52, 55, 56, 58, 59 11 studies employed a smartphone application,19, 23, 25, 26, 44, 53, 54, 57, 60–62 and one study used a text-message/SMS-based intervention.21 In terms of study population, 14 studies utilized DHIs to try to prevent PPD or PPA: of these, 10 studies did not include psychometric screening for or self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety as part of their study’s eligibility criteria,19, 21, 23, 24, 40, 42, 44, 46, 50, 60 while four studies screened potentially eligible participants for depression or anxiety in order to exclude those who screened positive.22, 25, 27, 62 The remaining 17 studies utilized DHIs to try to treat PPD or PPA among those who screened positive or were diagnosed with PPD or PPA Specifically, 12 studies included only those who screened positive for depression or anxiety prior to randomization,20, 26, 45, 52–59, 61 three studies included participants who underwent interview-based clinical assessments to diagnose major depressive disorder,43, 49, 51 and two studies included those who self-reported symptoms of depression or anxiety prior to randomization.47, 48The type of intervention delivered digitally also varied: one provided digital peer support,40 two delivered psychoeducation with peer support,51, 60 and nine provided psychoeducation.21, 23, 42, 44, 46, 47, 53, 62 Of the 20 studies that provided psychotherapy, 14 delivered CBT,20, 25–27, 43, 45, 48–52, 55, 59, 61 six provided mindfulness,19, 22, 24, 54, 57, 60 one delivered IPT,56 and one included a program combining mindfulness and CBT.58

Table 1:

Study characteristics

| Author (Year) | Count ry (UN Category) | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | Intervention | Intervention Type (type of psychotherapy, if psychotherapy) | Intervention Delivery | Quality | First postpartum follow-up (Sample size) | Postpartum Depressin (psychometri c scale) Mean (standard deviation) | Postpartumanxiety (psychometri c scale) Mean (standard deviation) | Screen positive (postpartum depression vs postpartum vs anxiety) | Loss to follow-up (number completed final study assessment/number initially randomized) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashford (2018) | England (developed) | Given birth in last 12 months, be aged over 18 years, live in England, read and write in English, have internet access, and have scored ≥ 5 on the GAD-7 |

Receiving formal psychological treatment at start of the study, reported self-harm or suicidalideation, or had a stillbirth or the baby was seriously ill. |

iWaWa: 9 modules including CBT & mindfulness, with option for weekly email and/or text- message reminders and weekly 30-min telephone support with ach module | Psychotherapy (CBT and mindfulness) | Online | Lower (not intentional to treat) |

DHI:8 TAU:21 |

DASS-21 DHI:2.75 (3.33) TAU:4.95 (3.91) |

GAD-7 DHI: 6.63 (5.29) TAU:8.29 (4.24) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI:44/46 TAU:22/43 |

| Bear (2022) | NewZealand (developed) | Mother of a child aged 012 months; access to asmartph one that can download applications | Smiling Mind's Mindfulness Foundation: smartphone application offering hundreds of hours of guided and unguided mindfulness meditations via multiple programs. Mindfulness foundation: 10 modules over 41 sessions, serving as introduction to mindfulness (not postnatal specific) | Psychotherapy (mindfulness) | Smartphone application | Lower (rando mizatio n and not intentio n to treat) | DHI:27 TAU:29 |

DASS-21 DHI:3.52 (3.84) TAU:5.59 (4.26) |

DASS-21 DHI:3.07 (3.49) TAU:5.13 (3.70) |

PPD: DHI:4; TAU:7 PPA: DHI:5; TAU:8 |

DHI:34/49 TAU:35/50 |

|

| Chan Ko Ling (2019) | China (developing) | Firsttime pregnant women with less than 24 weeks of gestation remainin g and who attended antenatal clinic at Kwong Wah Hospital, read and write Chinese or English, and were willing to consent. |

Unable to give informed written consent or communi cate with the interviewer. |

iParent app: adapted from in-person parenting course, provides videos and articles that are on-demand with ability to ask questions to OBGYN who answers privately |

Psychoeducation | Smartphone application | Higher | DHI:218 TAU:225 |

EPDS DHI:5.3 (4.4) TAU: 5.9 (4.7) |

DASS-21 DHI:1.9 (2.1) TAU: 1.8 (2.3) |

PPD: - PPA: - | DHI:112/3 30 TAU:105/3 30 |

| Danaher (2022) | United States (developed) | North Shore Universit y Health System patients who had EPDS score >12 during pregnan cy or within 1 year of delivery, ≥18 years of age, no active suicidal ideation, access to broadba nd internet via desktop/laptop, tablet, or smartph one, and English language proficiency. |

Active suicidalideation (those with affirmativ e answers to the EPDS selfharm item were included if social work assessment deemed them low-risk for suicide) |

MomMood- Booster2+Peri natalDepresion Program: six CBT sessions comprised of video and audio recordings, animations, and editable lists in browser-based web application, which opened sequentially over a 7 week period and were available for 7 months |

Psychot herapy (CBT) | Online | Lower (randomization) | DHI:86 TAU:92 |

PHQ-9 DHI:5.78 (4.42) TAU:7.48 (5.67) |

DASS-21 DHI:2.81 (2.82) TAU:4.12 (3.83) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI:10/96 TAU:3/95 |

| Dol (multiparous) (2022) | Canada (developed) | Between 37+0 weeks pregnant and 10 days postpart um,had daily access to mobile phone,>18 years old, lived and gave birth in in NovaScotia, and could speak and read English |

Newborn died or was expected to die prior to leaving the hospital, they did not havec access to a mobile phone (personal or shared), were unwilling to receive text messages, declined or withdrew by not participati ng in primary survey, or previousl y participat ed in developm ent or feasibility phase of this project |

53 standardized text messages providing information related to newborn care and maternal mental health in the first 6 weeks postpartum. 2 messages per day for 2 weeks, then daily message for weeks 3–6 | Psychoeducation | Text message | Higher | DHI:34 TAU:35 |

EPDS DHI:8.91 (6.09) TAU:8.0 (4.67) |

Postpartum specific anxiety scale DHI:97.3 (22.5) TAU:101.29 (19.01) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI:5/39 TAU:6/41 |

| Dol (nulliparous) (2022) | Canada (developed) | Between 37+0 weeks pregnant and 10 days postpart um, had daily access to mobile phone, >18 years old, lived and gave birth in in Nova Scotia, and could speak and read English |

Newborn died or was expected to die prior to leaving the hospital, they did not have access to a mobile phone (personal or shared), were unwilling to receive text messages, declined or withdrew by not participati ng in primary survey, or previousl y participat ed in developm ent or feasibility phase of this project |

53 standardized text messages providing information related to newborn care and maternal mental health in the first 6 weeks postpartum. 2 messages per day for 2 weeks, then daily message for weeks 3–6 |

Psychoe ducation | Text message | Higher | DHI:40 TAU:35 |

EPDS DHI:7.68 (3.97) TAU:8.66 (5.27) |

Postpartum specific anxiety scale DHI:106.6 (22.09) TAU: 108.2 (22.76) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI:4/44 TAU:12/47 |

| Duffecy (2019) | United States (developed) | ≥18 years old, between 20 and 28 weeks gestation at time of baseline assessm ent, had a score between 5 and 14 on the PHQ-8 score (mild- moderat edepression sympto ms), were able to read and speak English, andaccess to internet on any device | Diagnosis of a major depression episode, psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, substance use disorder or other diagnoses using the MINI, current use of psychotro pic medication, intention to resume antidepre ssant medicatio n after delivery (if women discontin ued use during pregnanc y), currently in psychothe rapy, endorsed suicidality | Sunnyside: 8- week online prevention intervention consisting of 16 core didactic lessons and 3 postpartum booster sessions through a CBT approach with peer support (used a garden that grew plants as lessons were completed and peers provided engagement) | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Online | Lower (not intentio n to treat) | DHI:10 TAU:2 | PHQ-9 DHI:2.3 (1.3) TAU: 3 (0) | -- | PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI:11/18 TAU:3/7 |

| Fernan des (2022) | Portugal | ≥18 years of age, | Current selfreported | Mindful Moment: selfguided one- | Psychotherapy | Online | Higher | DHI:70 | EPDS DHI: | HADS DHI: | PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI:76/146 TAU:23/146 |

| (developed) | having child aged up to 18 months old, having moderate or high levels of parenting stress, female, being Portuguese, being a resident of Portugal; having internet access in a desktop, tablet, or telephone | diagnosis of serious mental health condition (e.g., schizophrenia, substance abuse, bipolar disorder, and personality disorder) | hour modules (6 is total) designed for postpartum, designed to be opened one module per week per week. | (mindfulness) | TAU: 123 | 10.47 (0.57) TAU: 8.66 (5.27) |

9.39 (0.42) TAU: 10.03 (0.34) |

|||||

| Fonseca (2020) | Portugal (developed) | up to 3 months postpartum, being 18 years old or older; being atrisk for PPD (assessed by scores above the cutoff score (5.5) on the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised [PDPI-R] and/or presenting earlyonset PPD symptoms(assessed by scores above the cutoffscore (10) onthe Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale [EPDS], having access to a compute r/tablet/smartph one and internet access at home, being able to read and speak Portuguese, being a resident of Portugal. | presence of a seriousmedical condition(psychical or psychiatric) in mom or infant (selfreported) | Be A Mom: self-guided, 5 modules based on CBT that are presented with psychoeducati onal tools (text format, audio, video, and animations) and interactive exercises with personalized feedback tools. At end of module, a 2–3 minute summary video presented and homework activity is assigned. | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Online | Higher | DHI: 65 TAU: 82 |

EPDS DHI: 6.91 (0.45) TAU 6.87 (0.41): |

-- | PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 33/98 TAU: 14/96 |

| Gun (2022) | Turkey (developing) | Mothers who gave birth viacesarean delivery at maternity service of a tertiarylevel hospital in Turkey, were within 48 hours of birth, who had no complication, whose baby had no complication, who had a health baby, who had a singleton delivery, no chronic disease, no mental disorder, aged above 18 years, literate, able to communicate in Turkish, and who filled in data collection forms |

Did not meet aforement ioned inclusion criteria | Slideshow given describing education via Pecha Kucha technique, with narrative/inte nse visual materials were utilized. | Psychoe ducation | Smart phone application | Lower (not intention to treat, primary outcome not defined) | DHI: 70 TAU: 70 |

STAI DHI: 47.41 (8.5) TAU: 53.929 (8.735) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 8/78 TAU: 8/78 |

|

| Haga (2018) | Norway (devel oped) | Pregnant at <25 weeks gestation, at least 18 years old, able to read and write in Norwegi an, have access to the internet, and have an electronic mailing account | -- | Mamma Mia: automated internet-based program in 3 phases containing education to help participants psychologically prepare for being a mother. First: starts at 21–25 weeks' gestation with 11 sessions and ends at 37 week's; Second: have 2–8 week old infant and have three sessions a week for six weeks; Third: 10 sessions over 18m. In total 44 sessions over 11.5 months | Psychoe ducation | Text message | Higher | DHI: 392 TAU: 531 |

EPDS DHI: 5.2 (4.3) TAU: 5.8 (4.2) |

-- | PPD: DHI: 37; TAU: 63 PPA: - |

DHI: 297/678 TAU: 198/684 |

| Heller (2020) | Netherlands (developed) | ≥18 years,<30 weeks pregnant, showed symptoms of anxiety, depression, or both, access to internet.Theythen took CES-D and HADS and were eligible if their score on the CES-D was at least 16 or score on HADS Anxiety scale was 8 or more. Those with severe depressi on or anxiety sympto ms (CES-D ≥25 or HADS-A ≥12) were allowed to participate, but they were advised to contact their general practitio ner to see if they required other treatment | Reported intention to harm themselve s or to attempt suicide (assessed by one question of the Web Screening Questionnaire) | MamaKits online: 5 week guided intervention based on problem solving treatment. Each of the 5 modules had information and examples of pregnant women with depression or anxiety doing the intervention, and homework, which was evaluated by trained coaches, who provided on the assignment via secure email | Psychoe ducation | Online | Higher | DHI: 54 TAU: 65 |

EPDS DHI: 8.2 (5.2) TAU: 8.7 (5.9) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 17/79 TAU: 11/80 |

|

| Hsu (2021) | Taiwan (developed) | Pregnant women at a physician prenatal clinic at Taipei's Chang Gung Obstetric s and Gynecology | -- | We'll App: mindfulness | Psychotherapy (mindfulness) | Smart phone application | Lower (randomizatio n, not intentio n to treat) | DHI: 30 TAU: 30 |

EPDS DHI: 1.69 (0.298) TAU: 1.8 (0.475) |

-- | PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 0/30 TAU: 0/30 |

| Huang (2021) | China (developing) | ≥18 years old, first time mothers with healthy babies, ability to answer the question naires, and internet access by mobile phone or compute r | “If they or their infants had serious diseases” | Online learning forum, communicatio n area, ask the expert forum, baby at home forum, all developed according to self-efficacy theory and social exchange theory | Peer support | Online | Lower (not intentio n to treat) | DHI: 18 TAU: 18 |

EPDS DHI: 5.78 (2.23) TAU: 8.28 (2.66) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 2/20 TAU: 2/20 |

|

| Jannati (2020) | Iran (developing) | Women aged 18 and above, at least weekly access to the internet and mobile phone, giving birth in last 6 months, sufficient Persian language skills to complete survey, EPDS ≥13, and interview with psychologist to confirm PPD diagnosis |

Happy Mom: 8 lessons over 8 weeks like a storybook and see in story how similar moms with PPD dealt with or improved their mental health. Each lesson 45–60m and ended with assignments | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Smart phone application | Lower (not intentio n to treat) | DHI: 38 TAU: 37 |

EPDS DHI: 8.18 (1.5) TAU: 15.01 (2.9) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 1/39 TAU: 2/39 |

||

| Jiao (2019) | Singapore (developed) | First time mothers who delivered at a tertiary care center in Singapore | Web-based postnatal psychoeducational intervention accessible for one month | Psychoe ducation | Online | Higher | DHI: 64 TAU: 64 |

EPDS DHI: 4.73 9.94) TAU: 5.14 (10.55) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 7/68 TAU: 5/68 |

||

| Kocak (2021) | Turkey (developed) | Being 18 years or older and having given vaginal or cesarean birth, having Android phone and internet connection, having a baby with normal birth weight and an APGAR score of 8 and above, having developed no postpart um complications, speaking and understand Turkish | Being illiterate, Having complications in the mother or the newborn (including baby in the intensive care unit), presence of anomaly in the newborn, presence of chronic disease or disability in mother (selfreport or clinically diagnosed) disability in the mother (physical, mental, vision, hearing, etc.), having given birth to twins, having been diagnosed with anxiety and depression (selfreport), having had a high-risk pregnancy (pregnancy hypertension, gestational diabetes, etc), having divorced pregnancy or being in process of divorce | BebekveBiz: on-demand support and education on maternal care, baby care, breastfeeding, and the ability to interact with a consultant at any time. The program also sent notifications every 5–10 hours to increase motivation of the mothers. | Psychoeducation | Smart phone application | Lower (notintention to treat) | DHI: 50 TAU: 48 |

EPDS DHI: 6.68 (6.51) TAU: 8.81 (8.32) |

STAI DHI: 42.33 (0.72) TAU: 42.55 (0.79) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 12/62 TAU: 14/62 |

| Liu (2022) | China (developing) | Voluntary participation; ages 20–40 years old; 36–38 weeks’ pregnant; diagnosis of pregnancy; “no examination or treatment affecting endocrine function within half a year”; be able to use a smartph one for more than 3 years, can use various mobile phone applications | severe physical disease and mental disorder; experience in mindfulness training; taking antianxiety or antidepre ssants; high-risk pregnancy status diagnosed by obstetrician | We’ll App: smartphone application that aims to provide mindfulness and perceived social support interventions for puerperia. Received the app intervention 3 times a week for 8 weeks. | Psychotherapy (mindfulness) | Online | Lower (rando mization, not intention to treat) | DHI: 65 TAU: 65 |

-- | -- | PPD: DHI: 41; TAU: 52 PPA: - - |

DHI: 0/65 TAU: 0/65 |

| Loughan (2019) | Australia (developed) | within 12 months postpartum; aged over 18 years; fluent in written and spoken English; Australian resident; computer and internet access; selfreport symptoms of anxiety and/or depressi on above clinical threshold (i.e. GAD-7 and/or PHQ-9 total score ≥ 10), willing to provide contact details for their general practitioner | Current substance use or dependence; use of benzodiaz epines; diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder; started psychotherapy <4 weeks ago or medication <8 weeks ago for anxiety/depression. Applicants with severe depression (PHQ-9 total score ≥ 23) or current suicidality | MUMentum postnatal: three online CBT lessons that had to be completed within active treatment period of six weeks | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Online | Higher | DHI: 50 TAU: 47 |

EPDS DHI: 8.82 (4.96) TAU: 13.34 (4.96) |

GAD-7 DHI: 6.66 (4.23) TAU: 9.97 (4.22) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 32/69 TAU: 20/62 |

| Milgrom (2016) |

Australia (developed) | Australian residency; 18 years of age or older; English speaking; less than 1 year post partum, internet access with regular email use; EPDS score of 11–23 and score of <3 on item #10 (thoughts of selfharm). After this initial assessment, underwent structured clinical interview to confirm diagnosis of major or minor depressive disorder | Current substance abuse; Current and past manic/hypomanic symptoms; posttrau matic stress disorder; alcohol abuse or dependence; depression with psychotic features; risk of suicide as per risk protocol; current active treatment for depression (medication or psychotherapy). | MumMoodBooster: 6 interactive CBT sessions designed to be completed one per week, each with text animations, videos introductions, and case vignettes; personalization encouraged; self-monitoring via homework. Also with peermonitored forum and telephonebased coach for 30 minute per week sessions | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Online | Higher | DHI: 19 TAU: 22 |

BDI DHI: 14.5 (7.2) TAU: 23.0 (7.5) |

DASS-21 DHI: 4.2 (5.5) TAU: 5.4 (3.0) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 2/21 TAU: 0/22 |

| Milgrom (2021) | Australia (developed) | EPDS scores of 11–25; aged ≥18 years; 6 week to 1 year postpartum; familiari ty with internet and email; agreeing to be assigned to any of the 3 experimental conditions. After this initial assessment, underwent structured clinical interview to confirm diagnosis of major or minor depressive disorder | At risk of suicide based on follow-up questions to EPDS score >0 on question 10 during screening. In second phase, excluded if current substance abuse; manic or hypomanic symptoms or depression with psychotic features; posttrau matic stress disorder; risk of suicide; under treatment for depression (medication or therapy). | MumMoodBooster: 6 interactive CBT sessions designed to be completed one per week, each with text animations, videos introductions, and case vignettes; personalization encouraged; self-monitoring via homework. Also with peermonitored forum and telephonebased coach for 30 minute per week sessions | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Onlin e | Higher | DHI: 32 TAU: 33 |

BDI DHI: 11.63 (8.98) TAU: 18.85 (10.16) |

DASS-21 DHI: 1.81 (2.61) TAU: 4.73 (5.22) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 10/39 TAU: 6/38 |

| Monteiro (2020) | Portugal (developed) | Early postpartum period (up to 3 months postpartum); age ≥ 18 years; low risk for PPD (Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised <5.5); have internet access at home; resident of Portugal; understand Portuguese | Serious medical condition (physical or psychiatric); infant had serious health condition (both selfreported). | Be A Mom: five sequential online CBT modules, averaging 45 minutes in length, once a week. | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Online | Higher | DHI: 104 TAU: 145 |

EPDS DHI: 5.26 (0.33) TAU: 6.19 (0.29) |

-- | PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 87/191 TAU: 31/17 6 |

| Nishi (2020) | Japan (developed) | Pregnant women with Luna Luna Baby user ID; ≥20 years of age; 16–20 weeks of gestation; no diagnosis of major depressive episode in pastmonth per selfadministered interview; no bipolar episode lifelong. | -- | Luna Luna smartphone application: six CBT modules, each lasting about 5 minutes | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Smart phone application | Higher | DHI: 1086 TAU: 1260 |

EPDS DHI: 6.47 (0.12) TAU: 6.5 (0.12) |

-- | PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 804/2 509 TAU: 704/2 508 |

| O’Mahen (2014) | United Kingdom (developed) | Aged over 18 years; given birth to live baby within the last year; scored >12 on EPDS; did not experience substance abuse or psychosis; spoke English. Then diagnosed with major depressive disorder viadiagnostic clinical assessment | -- | Netmums: 12 session postpartum modules, each with interactive exercises where can chat with similar mothers in room moderated by peers, focus on behavioral activation (a component of CBT), weekly phone call | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Online | Higher | DHI: 37 TAU: 34 |

EPDS DHI: 11.04 (4.71) TAU: 14.26 (5.11) |

GAD-7 DHI: 8.71 (4.61) TAU: 11.28 (5.49) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 10/41 TAU: 13/41 |

| Pugh (2016) | Canada (developed) | 18 years of age or older; gave birth to an infant within last 12 months; residing in Saskatch ewan; selfreported access to and comfort using a computer and the internet; score of ≥10 on EPDS; consent to notify physician of participation; not receiving other psychotherapy; if taking medicati on, stable dose for more than a month | No past or present psychotic mental illness (schizophrenia), bipolar disorder; no current suicide plan or intent. | Maternal Depression Online: seven online modules (one a week), each with a range of media (text, graphics, animation, audio, and video). Also, a therapist would email participant weekly to provide support and encouragement and answer questions. | Psychot herapy (CBT) | Onlin e | Higher | DHI: 19 TAU: 21 |

EPDS DHI: 8.68 (3.8) TAU: 12.71 (3.7) |

DASS-21 DHI: 42.33 (0.73) TAU: 7.62 (6.74) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 6/25 TAU: 4/25 |

| Sawyer (2019) | Australia (developed) | EPDS score ≥7; at least 1 selfreported parenting problem; literacyin English; access to a smartphone. | -- | eMums Plus: nursing led, 4-month parenting educational intervention delivered via smartphone application when infants were 2–6 months old. Components included chat, timeline, resources, and contacts/assistance. | Psychoeducation | Smart phone application | Higher | DHI: 60 TAU: 58 |

EPDS DHI: 7.9 (--) TAU: 8.7 (--) |

-- | PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 15/72 TAU: 3/61 |

| Seo (2022) | South Korea (developed) | Score of 9 or higher on EPDS; within one year childbirth; used Androidbased smartphones | Receiving psychiatric treatment | Happy Mother App: provides psychoeducati on and CBT, previously shown to be of “superiorquality” in prior research; used for 8 weeks | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Smart phone application | Lower (notintention to treat) | DHI: 37 TAU: 36 |

EPDS DHI: 10.7 (4.64) TAU: 13.03 (6.19) |

-- | PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 13/50 TAU: 14/50 |

| Sjömark (2022) | Sweden (developed) | Score ≤5 on Likert scale of overall childbirth experience and/or exposure to immediate CD and/or severe hemorrh age (>2 liters) following childbirth |

<18 years old; no ability to use internet; Unable to speak, read, or write Swedish; severe mental illness based on participants statement; stillbirth and neonatal death, ongoing psychological treatment | Two parts: Part 1: six audio-visual modules (or could download text), one per week, with homework assignments and ability to talk to psychologist on demand.: six steps including homework. If completed this part and diagnosed with PTSD, then eligible for second part Part 2: 8 modules of individualized, structured content that included weekly therapeutic support via email | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Online | Higher | DHI: 69 TAU: 85 |

EPDS DHI: 8.76 (4.19) TAU: 8.62 (4.47) |

-- | PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 77/13 2 TAU: 54/13 4 |

| Sun(2021) | China (developing) | Aged 18 years and older; in 12th to 20th week of gestation; singleton pregnancy; no plan to terminate pregnancy; plan to receive antenatal care and deliverat study hospital; complete junior high school or above; positive depressive symptoms with EPDS >9 or a PHQ-9>4; able to use the app on smartph one for the study; able to understand and respond to question naire | At risk of suicide or self-harm; currently receiving psychiatric treatmentor using psychiatric medications; history of substance abuse or addiction in the past 6 months; prior experience with mindfulness meditation; declined to participate | Spirits Healing: 8-week mindfulness training program containing 8 sessionscomposed of thematic curriculum via text, audio, and visual materials, followed by writing in mindfulness journal | Psychot herapy (mindfulness) | Smartphone application | Higher | DHI: 52 TAU: 40 |

EPDS DHI: 6.77 (4.693) TAU: 6.25 (5.098) |

GAD-7 DHI: 4.31 (2.995) TAU: 4.1 (3.967) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 24/84 TAU: 34/84 |

| Van Lieshout (2021) | Canada (developed) | ≥18 years old; infant younger than 12 months; lived in Ontario; EPDS score of at least 10; live in Ontario. | -- | One day interactive, virtual workshop with didactic teaching, group exercises and discussions, and roleplay over four modules | Psychotherapy (CBT) | Onlin e | Higher | DHI: 165 TAU: 192 |

EPDS DHI: 11.65 (4.83) TAU: 14.04 (4.54) |

GAD-7 DHI: 7.97 (5.54) TAU: 10.76 (5.1) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 37/20 2 TAU: 9/201 |

| Vigod (2021) | Canada (developed) | Identified as mother (inclusive of all genders, adoptive and birth parents), 18 years or older with infant between 0–12 months old living with them; resided in Ontario; had EPDS score of 10 or above | Individuals with active suicidal ideation, mania, psychosis or a substance or alcohol use disorder; those without internet access; those unable to read or write in English | Mother Matters: 10 weekly topics following interpersonal therapy targets; each week, therapists would post educational information about the weekly topic to forum with a set of questions for group to answer and monitor responses | Psychotherapy (interpersonaltherapy) | Online | Higher | DHI: 37 TAU: 40 |

EPDS DHI: 11.3 (4.54) TAU: 12 (4.79) |

-- | PPD: DHI: 23; TAU: 20 PPA: - - |

DHI: 13/50 TAU: 8/48 |

| Yang (2019) | China (developing) | More than 18 years; 24 to 30 weeks’ gestation; lowrisk pregnancy at start of intervention; internet access; fluent in Chinese and able to complete the question naires; elevated depressive or anxious symptoms (PHQ-9 >4, GAD-7 >4) | History or current diagnosis of psychoso matic disease (physical symptoms or illness that results from interplay of psychosocial and physiologic process, such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or asthma); current substance abuse; participation in psychological therapy or stress reduction program; history of suicide attempt; current use of psychoact ive drug; high level of depression PHQ-9>14, or GAD-7>14; regular mindbody practice (including yoga, meditation) | 4 mindfulness modules given over 8 weeks through WeChat platform; included homework practice and ability to interact with each other and researchers | Psychotherapy (mindfulness) | Smartphone application | Higher | DHI: 52 TAU: 50 |

PHQ-9 DHI: 3.58 (2.32) TAU: 6.26 (3.31) |

GAD-7 DHI: 2.97 (2.34) TAU: 5.26 (2.88) |

PPD: - - PPA: - - |

DHI: 10/62 TAU: 11/61 |

Key: --: data not included in manuscript; DHI: digital health intervention; TAU: treatment as usual; CBT: cognitive behavioral therapy; EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; BDI: Becks Depression Inventory; DASS-21: Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 items (either depression or anxiety subscales); STAI: State Trait Anxiety Inventory; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (anxiety subscale); CES-D: Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

Synthesis of results and risk of bias of included studies

In total, 5532 participants received a digital health intervention and 5492 participants received TAU across the 31 individual studies (which were analyzed as 32 studies due to Dol et al’s dichotomous study population21), with sample sizes ranging from 18 to 2509 participants and follow up lasting from 2 days until one year after randomization. Inclusion and exclusion criteria differed significantly across studies; for example, most studies recruited participants exclusively in person during prenatal care clinics or birth hospitalization while 7 studies recruited participants partly or exclusively through social media or printed advertisements in community space. The time frame of the first screen for PPD or PPA was heterogeneous: though 28 studies first assessed for PPD or PPA from four to 12 weeks postpartum, the range extended from less than one week after delivery to 32 weeks postpartum.

Psychometric scales utilized to screen for PPD or PPA varied across studies (Table 1). Of the 29 studies that screened for PPD, 22 studies used the EPDS, three used the Patient Health Questionnaire-9,63 two used the Depression subscale of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21),64 and two used the Beck’s Depression Inventory.65 Four studies presented data on screen-positive rates for PPD (though the definition of screening positive differed across studies: one study screen-positive PPD as having a mild score or higher on the DASS-21,19 and the three other studies used the EPDS, with a score of ≥924 or ≥1046, 56 defined as screen positive). For PPA, six of the 17 studies that screened for PPA utilized the GAD-7, six used the anxiety subscale of the DASS-21,64 two used the State Trait Anxiety Inventory,66 Dol et al used the Postpartum Specific Anxiety Scale for the nulliparous and multiparous cohorts,67 and one use the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale.68 Only one study provided data on screen-positive rates for PPA, defined as a mildscore or more on the DASS-21 anxiety subscale.19

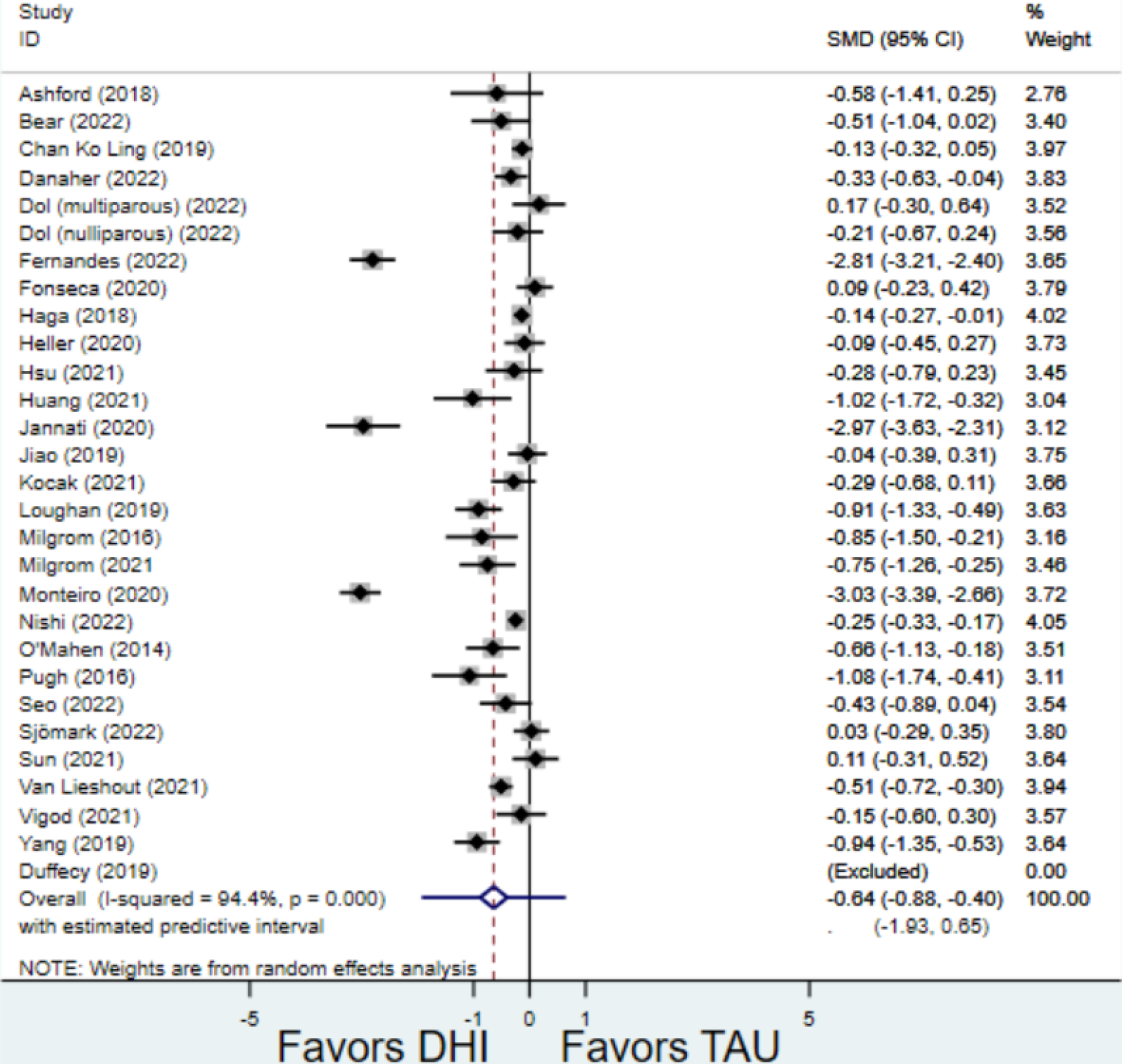

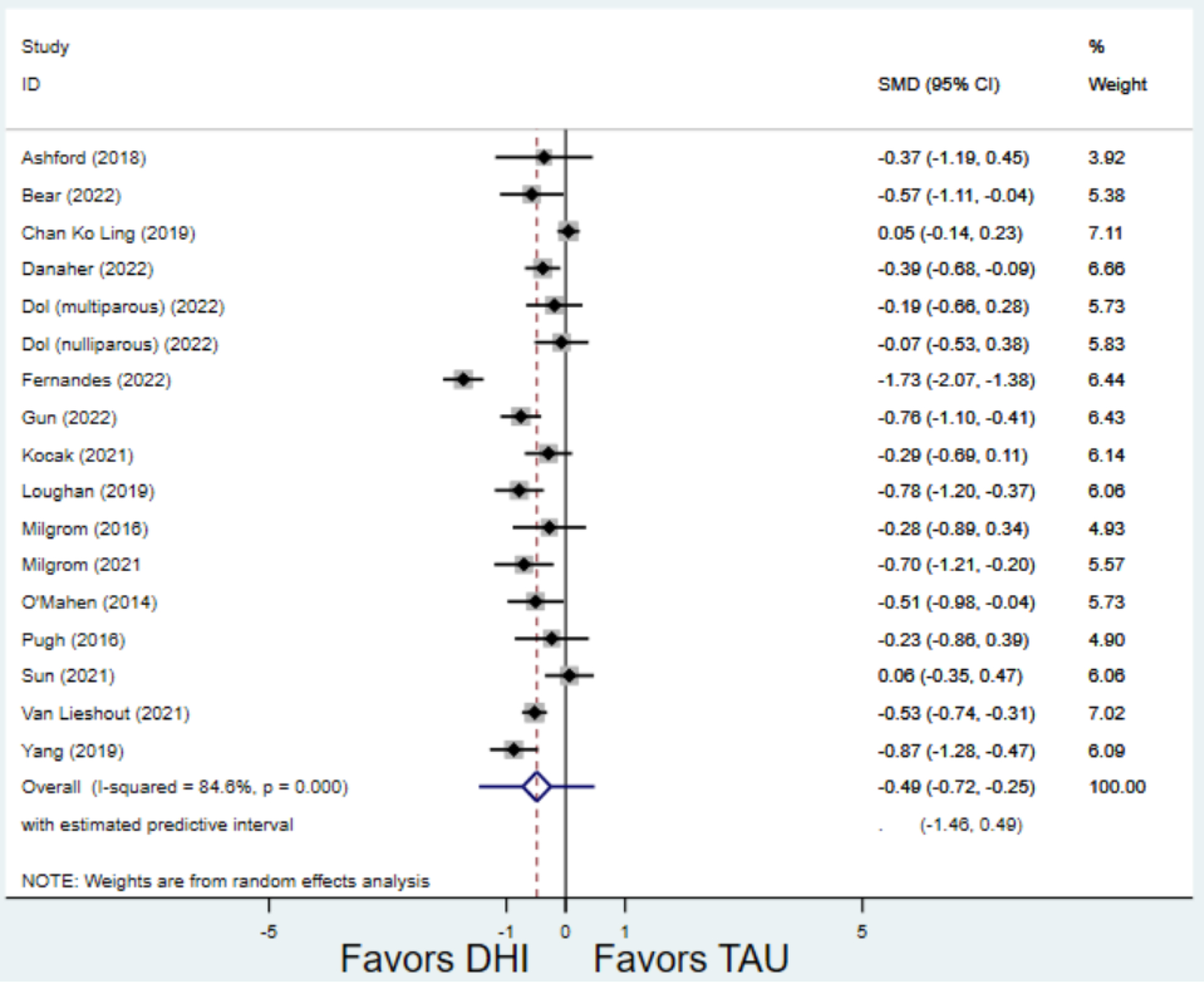

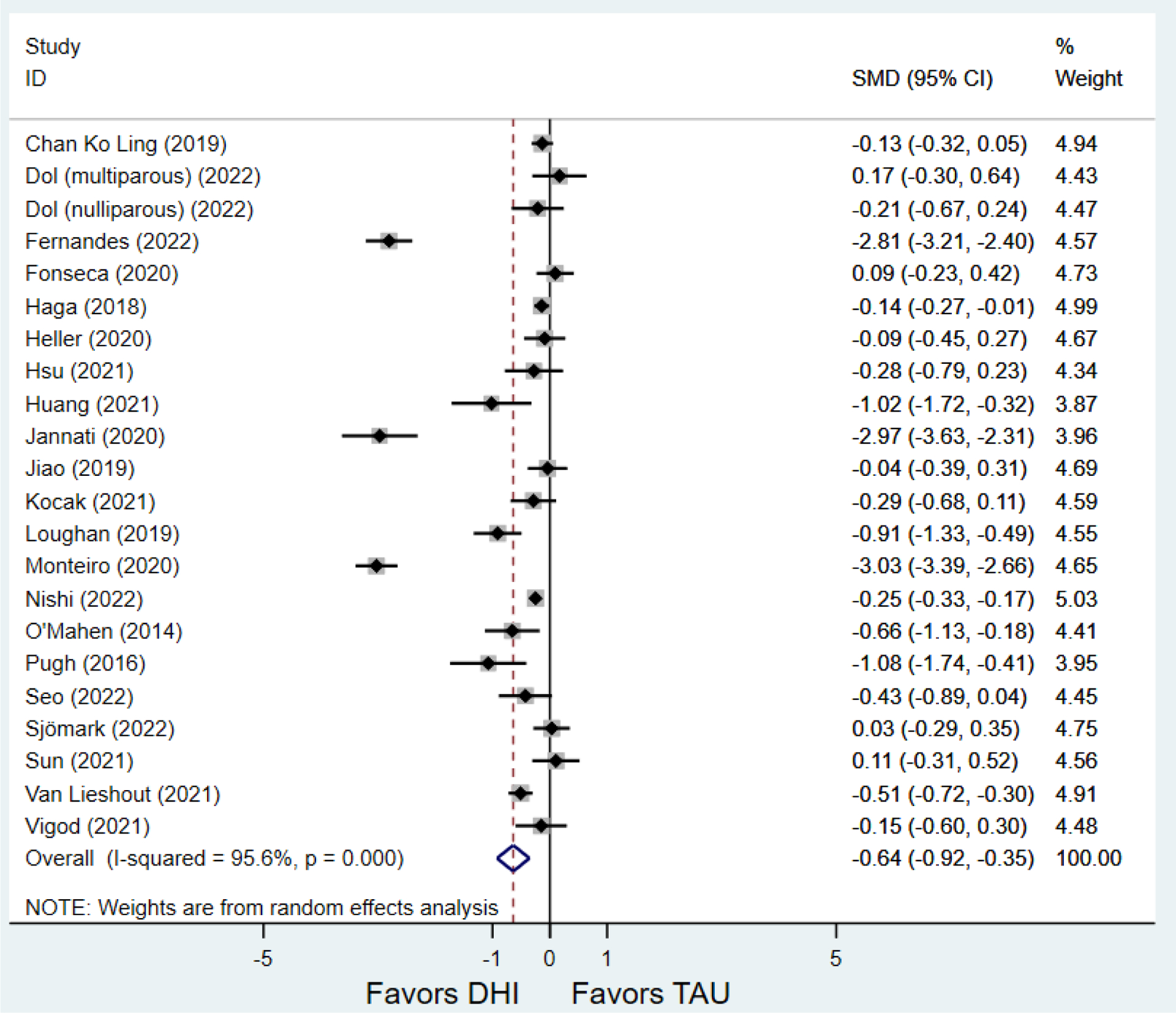

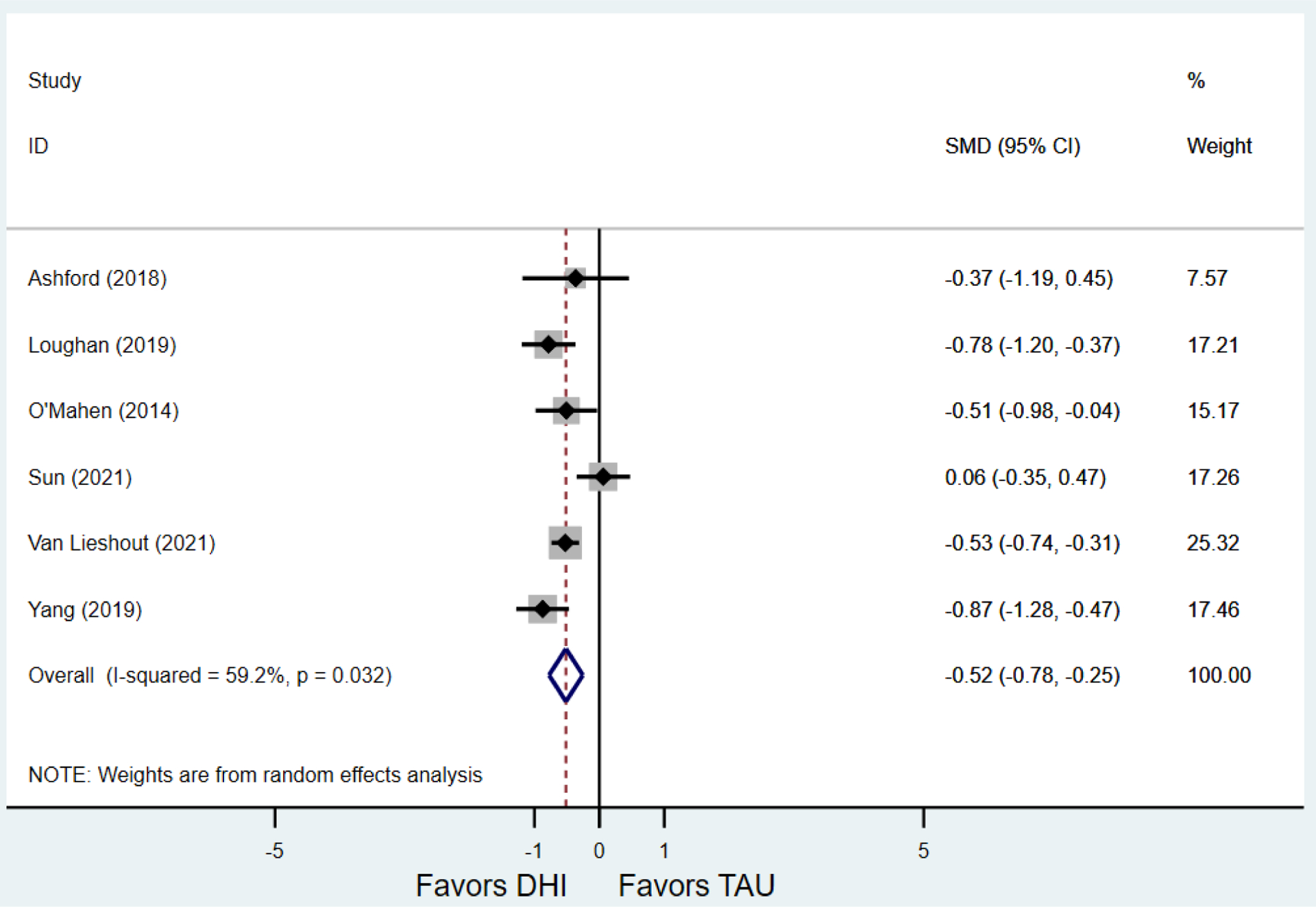

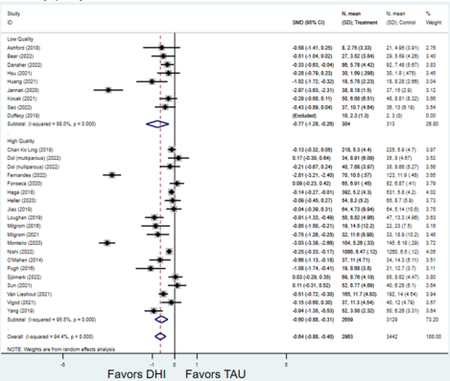

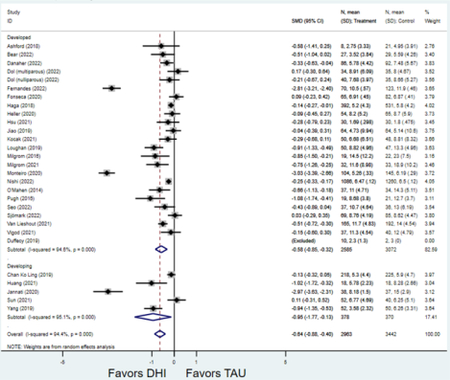

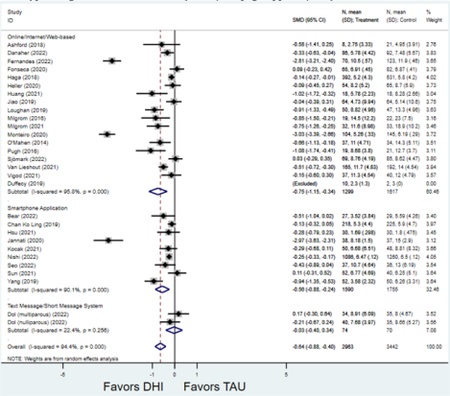

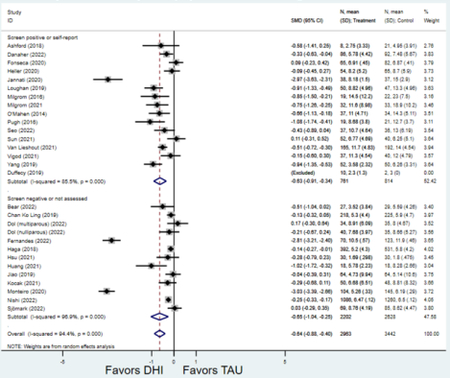

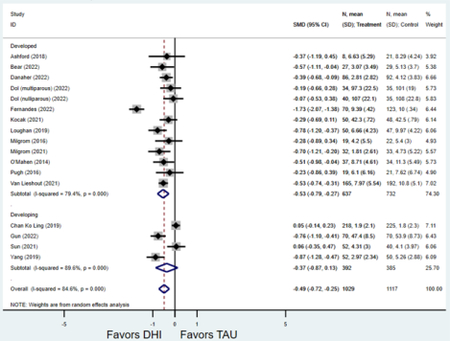

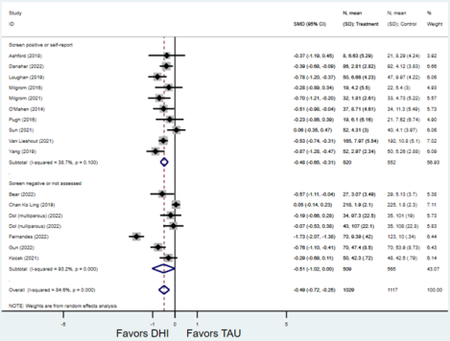

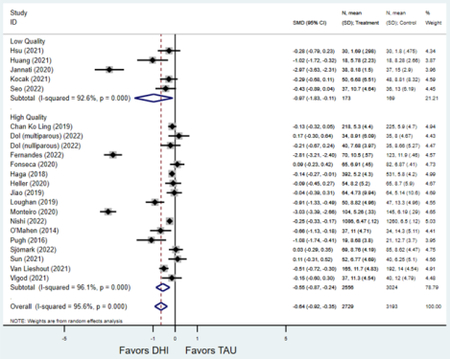

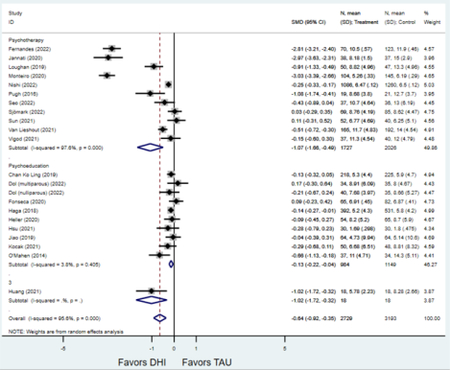

Compared to TAU, digital health interventions significantly, though modestly, reduced both PPD symptoms (29 studies: SMD −0.64 (95% CI: −0.88, −0.40); 95% prediction interval: −1.93, 0.65) and PPA symptoms (17 studies: SMD −0.49 (95% CI: −0.72, −0.25); 95% prediction interval: −1.96, 0.49) (Figure 2). A high amount of interstudy heterogeneity was identified for both PPD and PPA (I2 was 94.4% and I2 83.4%, respectively). For both primary outcomes, the funnel plots did not show asymmetry, and the Egger’s test confirmed an absence of publication bias for PPD (p=0.12) and PPA (p=0.85) (Figure 3).

Figure 2:

Weighted mean difference of scores of first postnatal screen for (a) postpartum depression and (b) postpartum anxiety after digital health intervention versus treatment as usual for postpartum depression or anxiety Key: DHI = digital health intervention; TAU = treatment as usual. SMD = standardized mean difference. PPD= postpartum depression. PPA = postpartum anxiety.

a) Scores on first screening for PPD after delivery

b) Scores on first screening for PPA after delivery

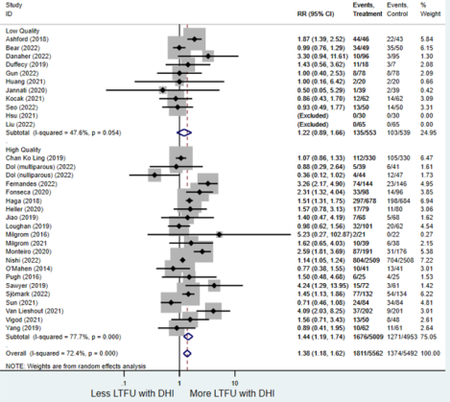

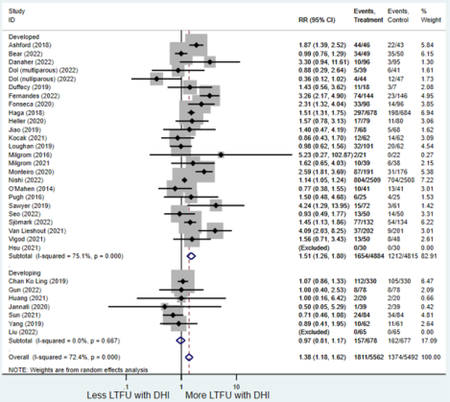

Figure 3:

Funnel plot with pseudo 95% confidence intervals for all studies included for postpartum depression screening

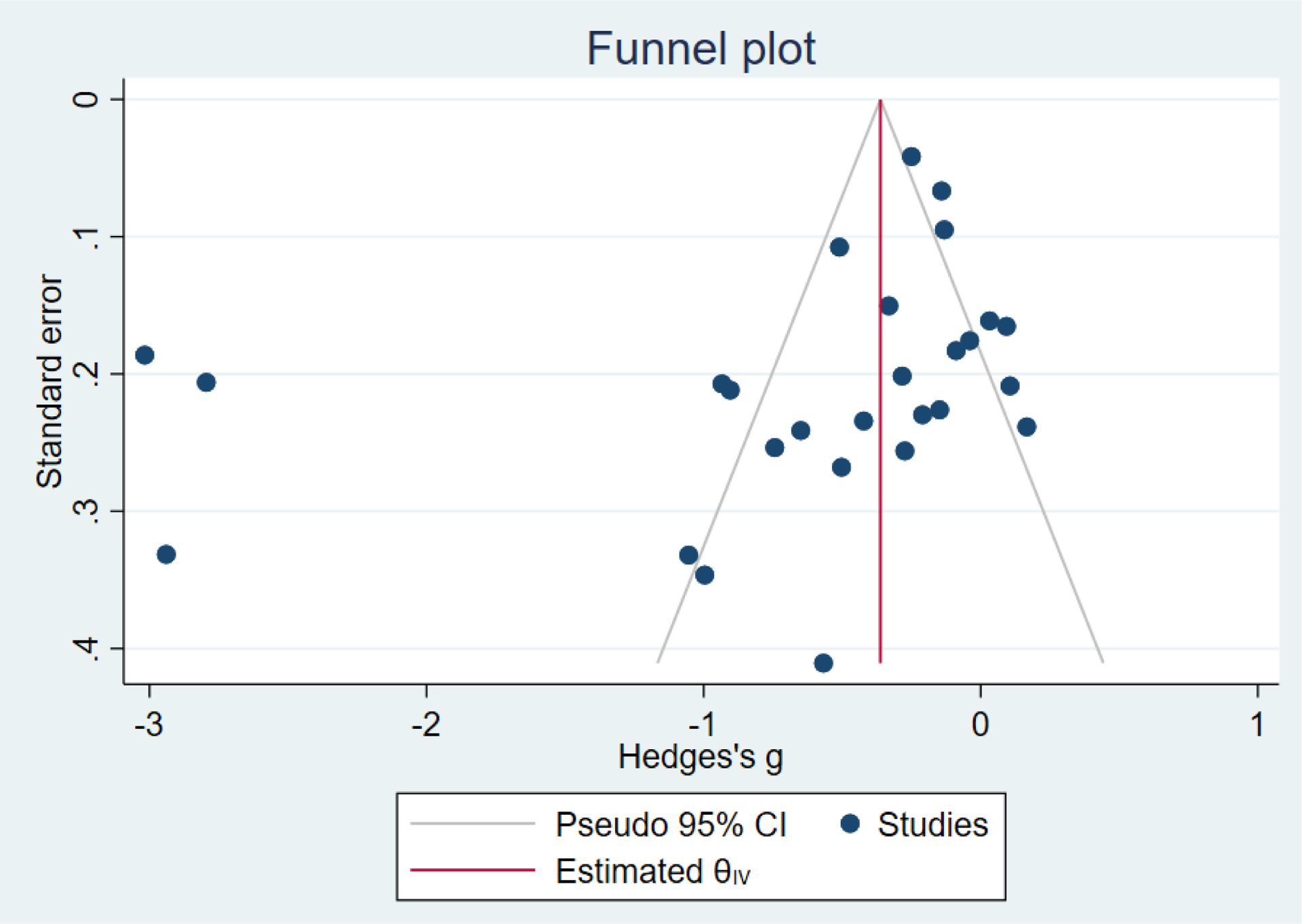

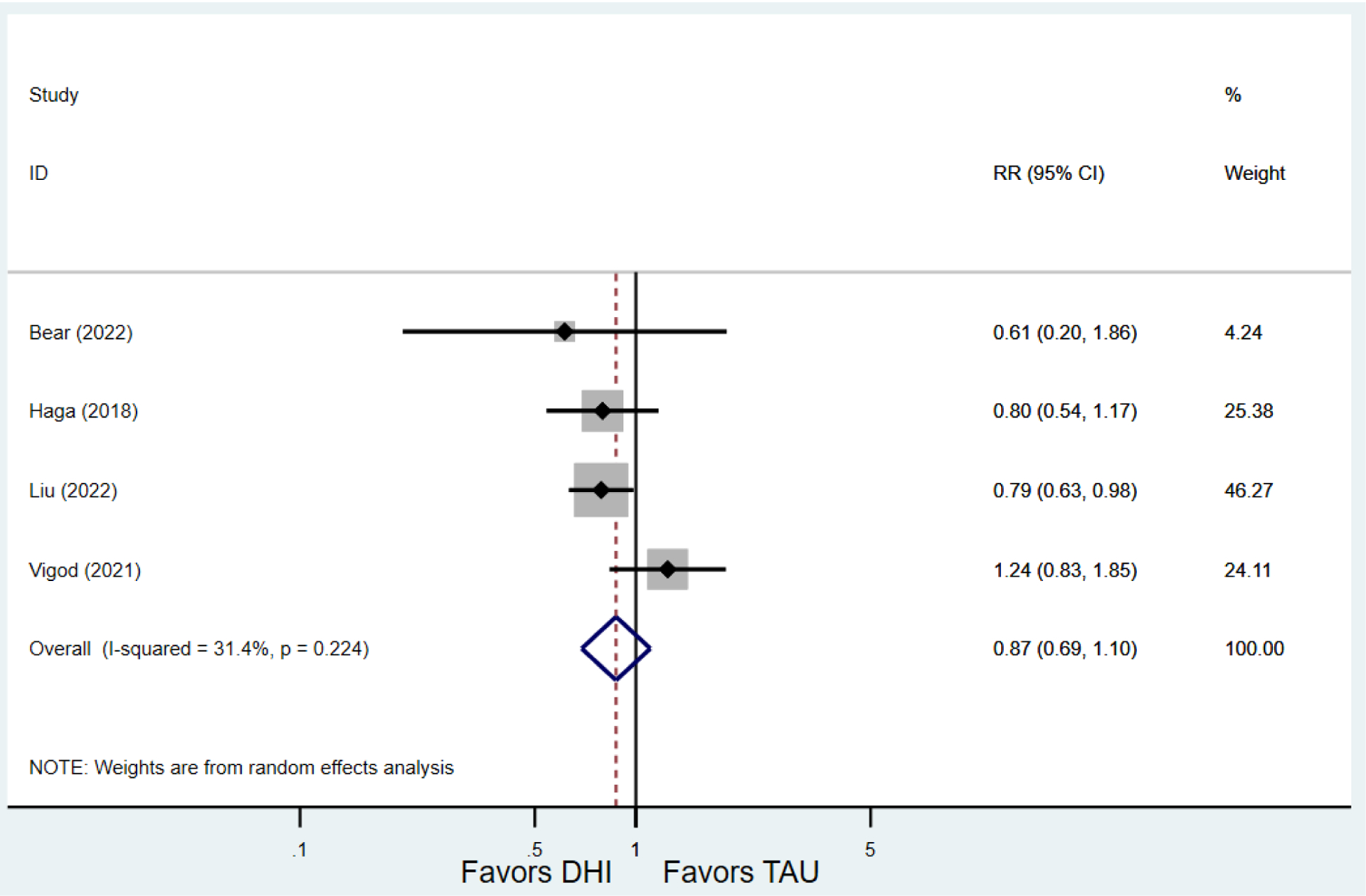

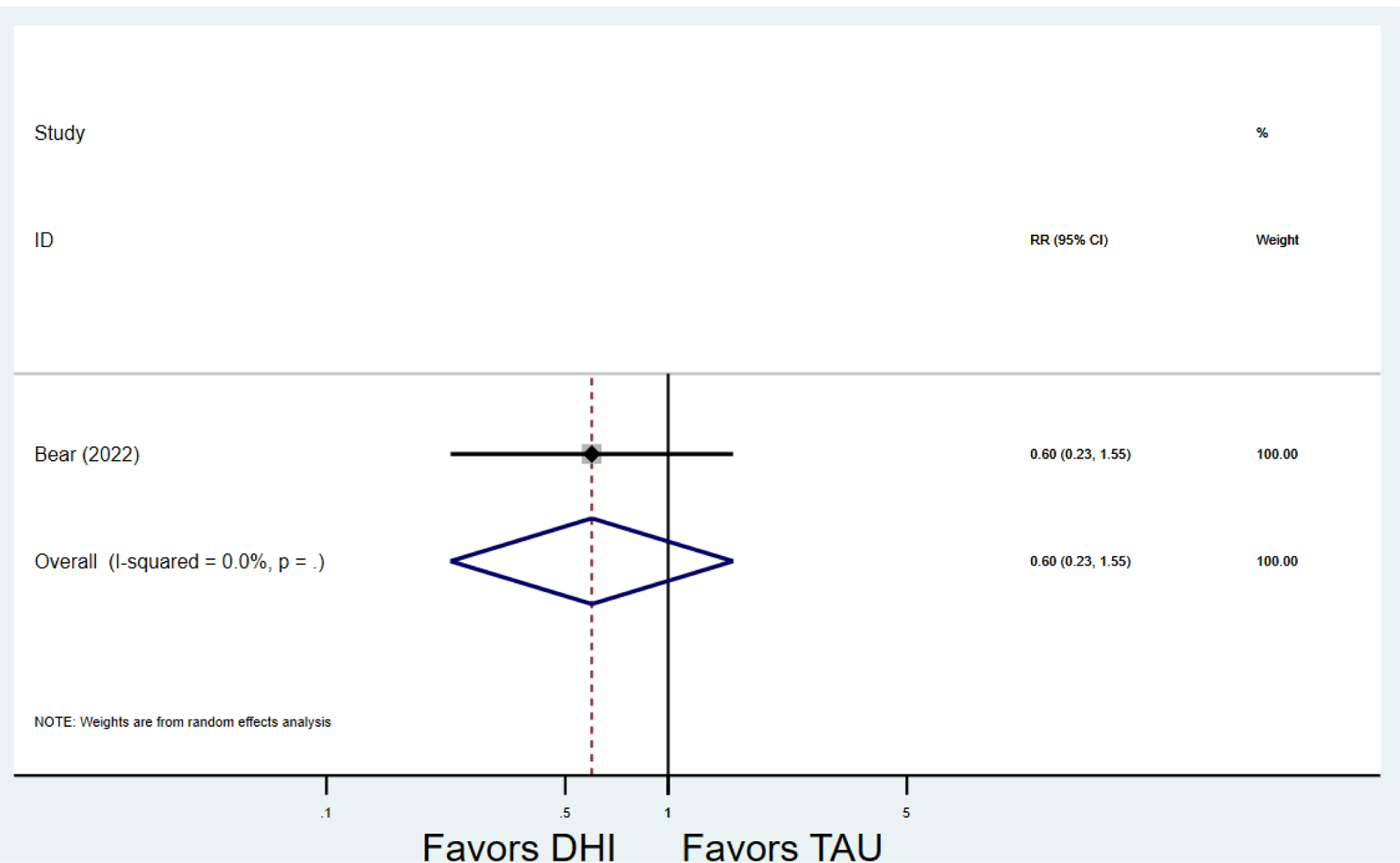

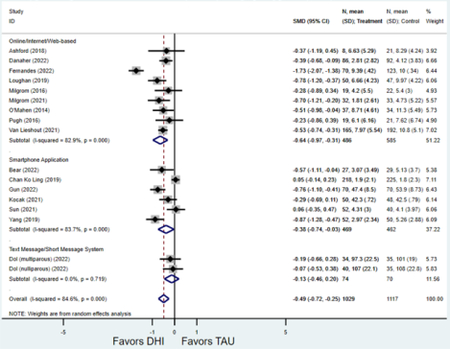

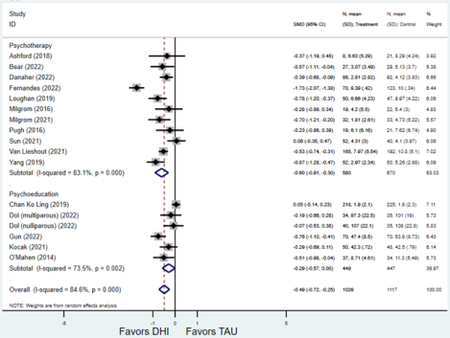

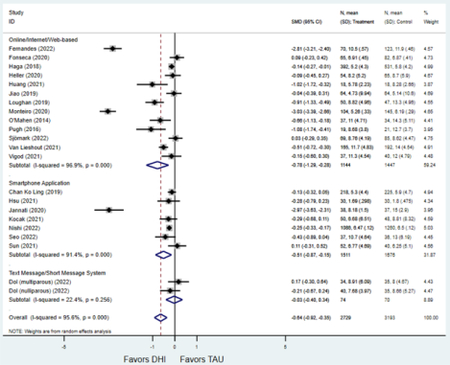

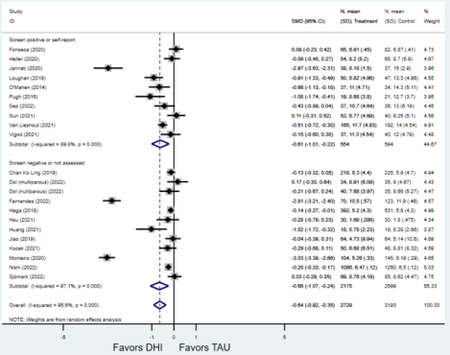

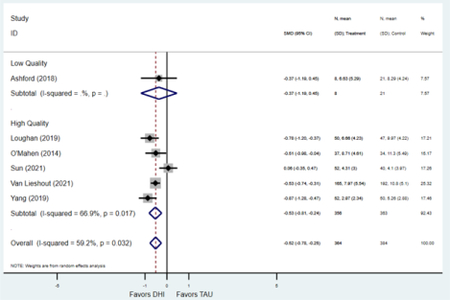

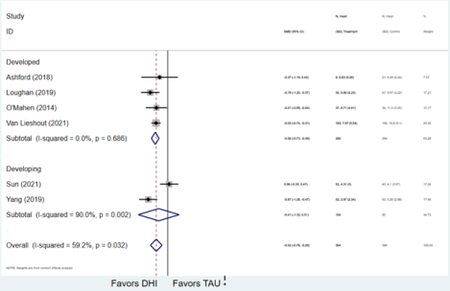

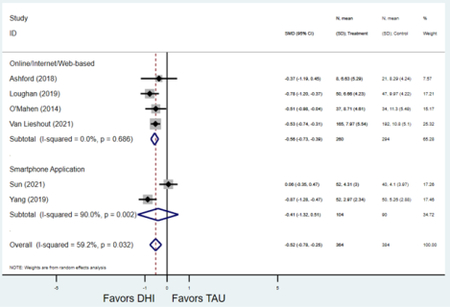

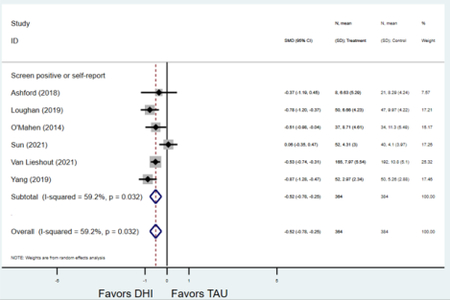

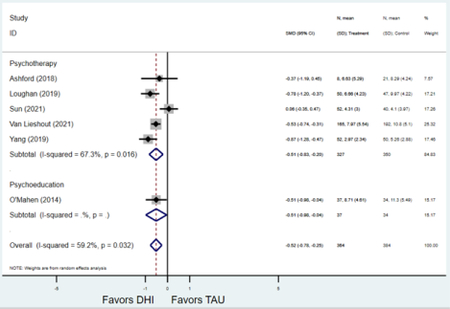

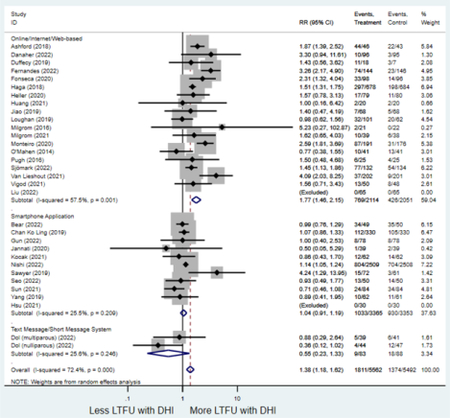

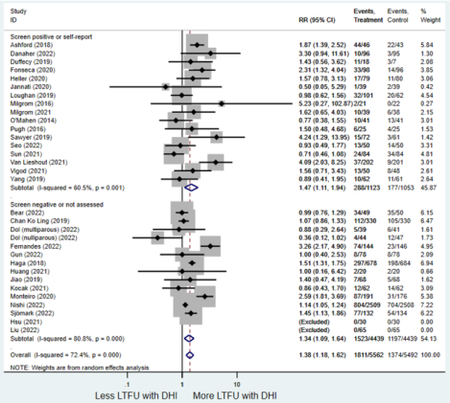

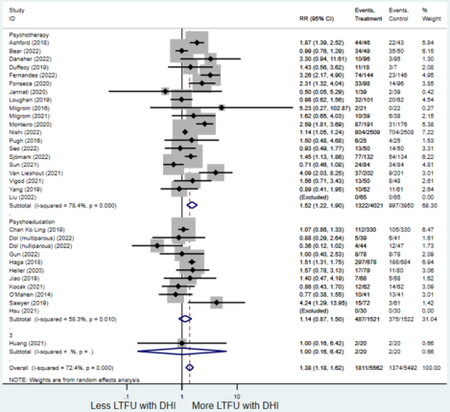

Secondary outcomes shown in Figure 4 include scores on the EPDS for PPD and on the GAD-7 for PPA as well as screen positive rates and overall loss-to-follow-up rates. When analyses were limited to studies that conducted PPD or PPA screening with these scales, DHIs significantly reduced both EPDS scores (22 studies: WMD −0.64 (95% CI −0.92, −0.35)) and GAD-7 scores (6 studies: WMD −0.52 (95% CI −0.78, −0.25)), though interstudy heterogeneity persisted (I2 95.6% for PPD and I2 59.5% for PPA). There were no differences in rates of screening positive for PPD (n=4) or PPA (n=1) among those randomized to DHI versus TAU. In terms of LTFU, 57.1% (n=3158) of those randomized to the DHI completed the final study assessment, compared to 66.2% (n=3635) of those randomized to TAU; thus, those randomized to the DHI had 38% higher risk of not completing the study comparatively (pooled RR 1.38 (95% CI 1.18, 1.62)).

Figure 4:

Secondary outcomes after digital health intervention versus treatment as usual for postpartum depression or anxiety Key for all forest plots: DHI = digital health intervention. TAU = treatment as usual. SMD = standardized mean difference. CI = confidence interval. PPD = postpartum depression. PPA = postpartum anxiety. EPDS: Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7. LTFU: loss to follow-up.

a) Scores on first EPDS screening for PPD after delivery

b)Scores on first GAD-7 screening for PPA after delivery

c) Screen positive for PPD

d) Screen positive for PPA

e) Loss to follow-up rates

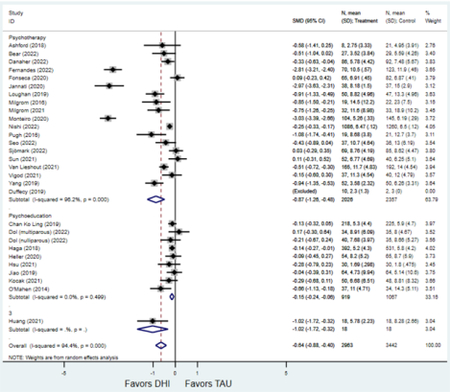

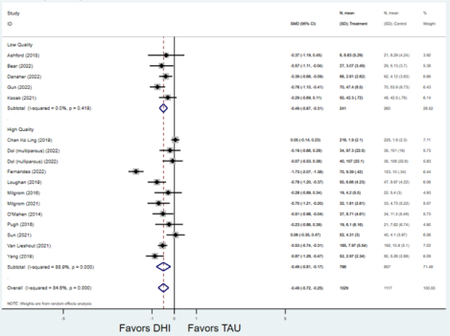

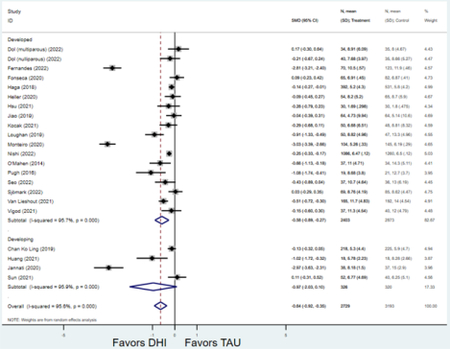

Forest plots for stratified analyses or primary outcomes and for all secondary outcomes are included in Appendix 3. In general, the effect of DHIs on primary and secondary psychological outcomes was similar among the primary analyses and analyses stratified by study quality, country setting, type of DHI (web/online, app, or text message), and whether the participants did or did not screen positive (or was diagnosed with or self-reported symptoms of) depression or anxiety (Table 2). Nearly all stratified analyses showed high amount of inter-study heterogeneity (Table 2). For the primary PPD outcome, interventions that provided psychotherapy had a larger effect on PPD and PPA compared to those that delivered psychoeducation with or without peer support (psychotherapy: PPD (19 studies): SMD −0.87 (95% CI: −1.26, −0.48) and PPA (11 studies): SMD −0.60 (95% CI: 0.91, −0.30)) versus psychoeducation: PPD (9 studies): SMD −0.15 (95% CI: −0.22, −0.06) and PPA (6 studies): SMD −0.29 (95% CI −0.57, 0.00)). The risk of not completing the final study assessment was higher among those randomized to DHI that were web/online-based (19 studies: RR 1.77 (95% CI 1.46, 2.15)) or that delivered psychotherapy (20 studies: RR 1.52 (95% CI 1.22, 1.90) compared to the overall (RR 1.38 (95% CI 1.18, 1.62)). Of note, there was no difference in loss to follow-up rates among those randomized to apps versus to TAU (RR 1.04 (95% CI: 0.91, 1.19)).

Table 2:

Pooled and stratified analyses of the effect of digital health interventions versus treatment as usual on postpartum depression or postpartum anxiety

| Outcome | No. of studies1 | Digital Health Interven tion (n) | Treatme nt as Usual (n) | Measure of Effect | Effect size (95% Confidence Interval) | I 2 | p from DHI vs TAU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score on Postpartum Depression Scale 1 | 29 | 2,963 | 3,442 | Standardi zed Mean Differenc e (SMD)2 | −0.64 (−0.88, −0.40) | 94.4% | <0.001 |

| Higher quality1 | 20 | 2,659 | 3,129 | SMD2 | −0.60 (−0.88, −0.31) | 95.5% | <0.001 |

| Lower quality | 9 | 304 | 313 | SMD2 | −0.77 (−1.28, −0.26) | 88.0% | 0.003 |

| Developed country1 | 24 | 2,585 | 3,072 | SMD2 | −0.58 (−0.85, −0.32) | 94.6% | <0.001 |

| Developing country | 5 | 378 | 370 | SMD2 | −0.95 (−1.77, −0.13) | 95.1% | 0.023 |

| Online/web-based intervention | 18 | 1,299 | 1,613 | SMD2 | −0.75 (−1.15, −0.34) | 95.8% | <0.001 |

| Smartphone application | 9 | 1,590 | 1,755 | SMD2 | −0.56 (−0.88, −0.24) | 90.1% | 0.001 |

| Text-message1 | 2 | 74 | 70 | SMD2 | −0.03 (−0.40, 0.34) | 22.4% | 0.88 |

| Screen-positive for depression or anxiety | 16 | 761 | 814 | SMD2 | −0.63 (−0.91, −0.34) | 85.5% | <0.001 |

| Screen-negative or no screening1 | 13 | 2,202 | 2,628 | SMD2 | −0.65 (−1.04, −0.25) | 96.9% | 0.001 |

| Psychoeducation with or without peer support1 | 9 | 919 | 1,067 | SMD2 | −0.15 (−0.22, −0.06) | 0.0% | 0.004 |

| Psychotherapy | 19 | 2,026 | 2,357 | SMD2 | −0.87 (−1.26, −0.48) | 96.2% | <0.001 |

| Score on Postpartum Anxiety Scale 1 | 17 | 1,010 | 1,095 | SMD2 | −0.49 (−0.72, −0.25) | 84.6% | <0.001 |

| Higher quality1 | 12 | 788 | 857 | SMD2 | −0.49 (−0.81, −0.17) | 88.9% | 0.003 |

| Lower quality | 5 | 241 | 260 | SMD2 | −0.49 (−0.67, −0.31) | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Developed country1 | 13 | 637 | 732 | SMD2 | −0.53 (−0.79, −0.27) | 79.4% | <0.001 |

| Developing country | 4 | 392 | 385 | SMD2 | −0.37 (−0.87, 0.13) | 89.6% | 0.15 |

| Online/web-based intervention | 9 | 486 | 585 | SMD2 | −0.64 (−0.97, −0.31) | 82.9% | <0.001 |

| Smartphone application | 6 | 469 | 462 | SMD2 | −0.38 (−0.74, −0.03) | 83.7% | 0.035 |

| Text-message1 | 2 | 74 | 70 | SMD2 | −0.13 (−0.45, 0.20) | 0.0% | 0.44 |

| Screen-positive for depression or anxiety | 10 | 520 | 552 | SMD2 | −0.48 (−0.65, −0.31) | 38.7% | <0.001 |

| Screen-negative or no screening1 | 7 | 509 | 565 | SMD2 | −0.51 (−1.02, −0.00) | 93.3% | 0.051 |

| Psychoeducation with or without peer support1 | 6 | 449 | 447 | SMD2 | −0.29 (−0.57, 0.00) | 68.33% | 0.052 |

| Psychotherapy | 11 | 580 | 670 | SMD2 | −0.60 (−0.91, −0.30) | 83.1% | <0.001 |

| Score on Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale 1 | 22 | 2,729 | 3,193 | Weighted Mean Differenc e (WMD)3 | −0.64 (−0.92, −0.35) | 95.6% | <0.001 |

| Higher quality1 | 17 | 2,556 | 3,024 | WMD3 | −0.55 (−0.87, −0.24) | 99.31% | <0.001 |

| Lower quality | 5 | 173 | 169 | WMD3 | −0.97 (−1.83, −0.11) | 94.94% | 0.027 |

| Developed country1 | 18 | 2,403 | 2,873 | WMD3 | −0.58 (−0.89, −0.27) | 95.7% | <0.001 |

| Developing country | 4 | 326 | 320 | WMD3 | −0.97 (−2.03, 0.10) | 95.6% | 0.07 |

| Online/web-based intervention | 13 | 1,144 | 1,447 | WMD3 | −0.78 (−1.29, −0.28) | 96.9% | 0.002 |

| Smartphone application | 7 | 1,511 | 1,676 | WMD3 | −0.51 (−0.87, −0.15) | 99.56% | 0.005 |

| Text-message1 | 2 | 74 | 70 | WMD3 | −0.03 (−0.40, 0.34) | 22.4% | 0.88 |

| Screen-positive for depression or anxiety | 10 | 554 | 594 | WMD3 | −0.61 (−1.01, −0.22) | 89.8% | 0.002 |

| Screen-negative or no screening1 | 12 | 2,175 | 2,599 | WMD3 | −0.66 (−1.07, −0.24) | 97.1% | 0.002 |

| Psychoeducation with or without peer support1 | 10 | 984 | 1,149 | WMD3 | −0.13 (−0.22, −0.04) | 3.7% | 0.04 |

| Psychotherapy | 11 | 1,727 | 2,026 | WMD3 | −1.07 (−1.66, −0.49) | 97.6% | <0.001 |

| Score on Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 scale | 6 | 364 | 384 | WMD3 | −0.52 (−0.78, −0.25) | 59.52% | <0.001 |

| Higher quality | 5 | 356 | 363 | WMD3 | −0.53 (−0.81, −0.26) | 66.9% | <0.001 |

| Lower quality | 1 | 8 | 21 | WMD3 | −0.37 (−1.19, 0.45) | n/a | 0.38 |

| Developed country | 4 | 260 | 294 | WMD3 | −0.56 (−0.73, −0.39) | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Developing country | 2 | 104 | 90 | WMD3 | −0.41 (−1.32, 0.51) | 87.27% | 0.38 |

| Online/web-based intervention | 4 | 260 | 294 | WMD3 | −0.56 (−0.73, −0.39) | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Smartphone application | 2 | 104 | 90 | WMD3 | −0.41 (−1.32, 0.51) | 87.27% | 0.38 |

| Text-message | 0 | -- | -- | WMD3 | -- | -- | -- |

| Screen-positive for depression or anxiety | 6 | 364 | 384 | WMD3 | −0.52 (−0.78, −0.25) | 59.52% | <0.001 |

| Screen-negative or no screening | 0 | -- | -- | WMD3 | -- | -- | -- |

| Psychoeducation with or without peer support1 | 1 | 37 | 34 | WMD3 | −0.51 (−0.83, −0.20) | 67.3% | 0.035 |

| Psychotherapy | 5 | 327 | 350 | WMD3 | −0.51 (−0.98, −0.04) | -- | 0.01 |

| Did not finish last study assessment (n) 1 | 32 | 1,811 | 1,374 | Relative risk (RR)4 | 1.38 (1.18, 1.62) | 72.4% | <0.001 |

| Higher quality1 | 21 | 1,676 | 1,271 | RR4 | 1.44 (1.19, 1.74) | 77.7% | <0.001 |

| Lower quality | 11 | 135 | 103 | RR4 | 1.22 (0.89, 1.66) | 47.6% | 0.21 |

| Developed country1 | 25 | 1,654 | 1,212 | RR4 | 1.51 (1.26, 1.80) | 75.1% | <0.001 |

| Developing country | 7 | 157 | 162 | RR4 | 0.97 (0.81, 1.17) | 0.0% | 0.76 |

| Online/web-based intervention | 19 | 769 | 426 | RR4 | 1.77 (1.46, 2.15) | 57.4 | <0.001 |

| Smartphone application | 11 | 1,033 | 930 | RR4 | 1.04 (0.91, 1.19) | 25.5% | 0.39 |

| Text-message1 | 2 | 9 | 18 | RR4 | 0.55 (0.23, 1.33) | 25.6% | 0.19 |

| Screen-positive for depression or anxiety | 17 | 288 | 177 | RR4 | 1.47 (1.11, 1.94) | 60.5% | 0.008 |

| Screen-negative or no screening1 | 15 | 1,523 | 1,197 | RR4 | 1.34 (1.09, 1.64) | 80.8% | 0.005 |

| Psychoeducation with or without peer support1 | 12 | 487 | 375 | RR4 | 1.14 (0.87, 1.50) | 58.3% | 0.32 |

| Psychotherapy | 20 | 1,322 | 997 | RR4 | 1.52 (1.22, 1.90) | 78.4% | <0.001 |

Dol et al study counted as two studies;

Calculated via Hedge’s g statistic;

Calculated via pooled mean difference.

numbers > 1 = loss-to-follow up is greater among digital health interventions compared to treatment as usual.

Discussion

Principal Results

In this meta-analysis of randomized trials analyzing the effect of DHIs on PPD and PPA, a modest but statistically significant reduction in scores on psychometric scales assessing PPD and PPA were identified among those randomized to DHIs overall and when PPD and PPA were assessed via EPDS or GAD-7, respectively. This effect was more pronounced when the DHI delivered psychotherapy (CBT, IPT, or mindfulness) compared to psychoeducation with or without peer support. DHIs had similarly modest effect on preventing PPD or PPA from those who screened negative (or were not screened) for these conditions upon randomization and on treating PPD and PPA for those who screened positive or were diagnosed with depression or anxiety at randomization. Though LTFU rates were higher among those randomized to DHIs than those randomized to TAU, this difference was driven by a high rate of drop out identified in studies utilizing web/online interventions: there was no difference in LTFU rates among those randomized to apps compared to TAU. These findings suggest that, while all DHIs appear to improve postpartum mental health, those that provide psychotherapy and are delivered via smartphone application may be the most effective at improving psychological outcomes and retaining participant engagement, respectively.

Comparisons with Prior Work

Our findings are consistent with those reported from prior meta-analyses,15–18 which also noted a small but statistically significant improvement in psychometric scales measuring PPD or PPA but no difference in screen-positive rates for PPD among those randomized to DHIs compared to TAU. However, unlike the prior meta-analyses,15–18 which reported mostly pooled psychometric outcomes, we conducted stratified analyses based on factors that could plausibly impact the effectiveness of DHI, such as study quality, country of origin, type of intervention delivered (psychoeducation or psychotherapy), and type of DHI utilized (online, app, or SMS). In addition, unlike prior meta-analyses—which presented study populations as homogeneous15–18—one of our analyses stratified the primary studies into those in which potential participants were required to screen positive for or self-reported depressive or anxiety symptoms in order to be randomized. Interestingly, this stratified analysis concluded that DHI had a similar effect on postpartum psychometric scales regardless of whether the participant did or did not screen positive for depression or anxiety. Altogether, our findings not only support those from prior meta-analysis15–18 but add depth to the relationship between DHI and postpartum depression and anxiety.

Clinical Implications

PPD and PPA are among the most common conditions in the postpartum period.1, 2 Despite the fact that psychoeducation3 and psychotherapy4–6 have been shown to effectively prevent and treat PPD and PPA, few people who have PPD or PPA are able to access these interventions,7 potentially due to a lack of skilled mental health professionals.8 DHI are accessible to nearly all who reside in the United States,10–12 bypass barriers associated with reduced adherence to in-person postpartum care,13, 14 and are inherently scalable without relying on skilled mental health professionals for dissemination. The fact that DHIs are more effective than TAU in terms of reducing scores on psychometric scales assessing for PPD and PPA is promising for PPD/PPA prevention and treatment. More specifically, widespread incorporation of DHIs that provide evidence-based psychoeducation or psychotherapy could provide modest population-wide reductions in PPD and PPA symptoms, as measured by psychometric scales. Furthermore, the benefits to DHI noted in the subgroup of studies conducted in developing countries offers scalable promise to the global burden of untreated perinatal mental health conditions.

Strengths and Limitations

Our study offers several strengths. First, we used a predesigned protocol in which an expert research librarian conducted a comprehensive search strategy, and two researchers independently screened all abstracts and potentially eligible full manuscripts for inclusion before independently abstracting data, which reduced bias. We also updated our search during the review process due to the publication of multiple potentially eligible randomized trials after the initial search was complete, which allowed us to base our conclusions on the most up-to-date data available. In addition, we conducted multiple stratified analyses, which allowed us to assess the impact of study quality, study setting, type of intervention delivered, and type of DHI on the effectiveness of DHIs on PPD and PPA. Lastly, we pooled data from studies using random-effects models, which is a more conservative strategy that helps reduce the potential effect of heterogeneity between studies.

Nevertheless, limitations should be considered. First, the findings of our meta-analysis carry forward the limitations of primary studies, including lower quality studies. However, the persistence of our findings within the subgroup of studies considered high quality provides reassurance against biased findings. Second, there was excessive clinical and statistical heterogeneity in our analysis, with multiple different psychometric scales employed, varying eligibility criteria for entry into each included study, and the study interventions, even within similar categories of DHIs. We attempted to reduce the effect of this heterogeneity by conducting multiple secondary analysis and subgroup analysis in which the analyses were limited to studies that contained the same psychometric scale, or that required participants to screen positive for PPD, or used the same individual type of DHI. Though these additional analyzes may have reduced the effect of heterogeneity on our outcomes, it would be impossible to eliminate the heterogeneity, particularly for study intervention. Indeed, a trial analyzing the effect of self-guided online videos on CBT45 and another trial analyzing the effect of a live, interactive, remote CBT workshop55 were both categorized as a DHI offering online CBT, though these interventions clearly differed. Reframing the heterogeneity of DHIs included in this meta-analysis as mirroring differences between in-person CBT, IPT, or mindfulness programs also reduces the potential effect of heterogeneity on our outcomes. Specifically, each psychotherapeutic intervention abides by defined principles within CBT, IPT, or mindfulness but is not identical to other programs offering the same psychotherapy. Third, the varying definitions of screening positive for PPD or PPA entailed—and the paucity of studies that included data on screening positive for either condition—limits our ability to examine the effect of DHIs on screen-positive PPD or PPA. Lastly, there was also marked heterogeneity in psychometric scales used in the primary PPD and PPA outcomes. Given the fact that our secondary outcomes were scores on one PPD or PPA scale and these analyses had similar results as from our primary analysis, it is unlikely that this heterogeneity affected our results.

Need for additional research

The fact that participants were more likely to not complete final study assessments if randomized to the DHI group than to the TAU group demonstrates that more research is needed to optimize acceptability and use of DHI in clinical settings. Incorporating end-user feedback into the intervention development process has been described as an effective strategy to encourage sustained participant engagement with DHIs.69–71 In addition, the notable difference in LTFU rates among online DHIs versus app-based DHIs—and in particular the lack of difference in loss-to-follow up rates among app-based DHIs and TAU—should be a research priority. Implementation research or hybrid implementation-effectiveness trials may offer another avenue to understand and optimize DHI use.72 Lastly, most studies included assessed PPD, but fewer assessed PPA. Future research on DHI should include assessments for both PPD and PPA.

Conclusions

The results from this meta-analysis of randomized trials suggest that DHIs significantly—though modestly—reduce PPD and PPA symptoms and that this effect is more pronounced if the DHI delivers psychotherapy such as CBT, IPT, or mindfulness. Though LTFU rates were higher overall among those randomized to DHIs than those randomized to TAU, there was no difference in LTFU rates among those randomized to apps compared to TAU. These findings suggest that DHIs that provide psychotherapy and are delivered via smartphone application may be the most effective at improving perinatal psychological outcomes and retaining participant engagement. However, because few studies include app-based psychotherapy, additional high-quality randomized trials are needed to further examine the potential of DHIs delivering psychotherapy via a smartphone application specifically on reducing PPD and PPA.

Supplementary Material

AJOG at a Glance.

- A. Why was this study conducted?

- a. Digital health interventions (DHI) are increasingly utilized in postpartum depression (PPD) and postpartum anxiety (PPA) prevention and treatment.

- b. Eight randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing DHI to treatment as usual for PPD and PPA have been published since the most recent meta-analysis

- B. What are the key findings?

- a. DHIs effectively but modestly reduce symptoms of PPD and postpartum anxiety overall, particularly when the DHI provides psychotherapy.

- b. Those randomized to DHI had higher risk of loss-to-follow-up (LTFU) versus those randomized to TAU overall, but the rate of LTFU was similar among smartphone applications.

- C. What does this study add to what is known?

- a. App-based DHIs providing psychotherapy may be the most effective at improving perinatal psychological outcomes and retaining participant engagement.

Funding:

Dr. Lewkowitz is supported by the NICHD (K23HD103961). Dr. Ayala is a recipient of the Robert A. Winn Diversity in Clinical Trials Career Development Award, funded by Gilead Sciences. Dr. Battle is supported by the NICHD (R01HD81868; R21HD110912), NIDA (R34DA055317) and the American Psychological Association (6NU87PS004366-03-02). Dr. Ranney is supported by the NICDH (R01HD104187; R01HD093655), NIGM (P20GM139664), NCIPC (R01CE003267), and NIDA (501DA054698). Dr. Miller is supported by the NICHD (R01HD105499). These funding sources had no role in study design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Appendix 1: Systematic Review Search Methodology

Search Strategies created by Angela Hardi, MLIS, Original search: October 2021; Updated Search: December 2022

Methods:

The published literature was searched using strategies designed by a medical librarian for the concepts of postpartum depression, anxiety, or distress, and mobile health applications. The strategies were created using a combination of controlled vocabulary terms and keywords, and were executed from database inception in Medline (Ovid), Embase.com, Scopus, CINAHL Plus, PsycInfo, Cochrane Library (including CENTRAL), and Clinicaltrials.gov. Results were limited to randomized controlled trials by using RCT filters recommended by the Cochrane Group for Ovid-Medline1, Embase,2 and CINAHL,3 and a librarian-created filter for Scopus.4 Results were limited to English and Spanish using database-supplied limits. The initial searches were completed on October 7, 2021, with an updated literature search completed on December 6, 2022. A 2021–2022/2023 date limit was used on the updated literature search. Complete search strategies are provided.

Results:

The initial literature search completed in 2021 retrieved 614 search results. The citations were imported to Endnote where 304 duplicate citations were identified and removed leaving 310 unique citations for analysis. The updated literature search completed in 2022 retrieved 307 search results, with 189 duplicate citations, leaving 118 unique citations for analysis. Between the initial and updated literature searches there were 428 unique citations remaining for further review.

Lefebvre C, Manheimer E, Glanville J. Chapter 6: Searching for studies. In: Higgins J, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org]

Randomised controlled trials filter: Embase. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Search Filters Web Page: https://www.sign.ac.uk/what-we-do/methodology/search-filters/

Clowes, M. Randomised controlled trials filter: CINAHL for EBSCO. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN): https://www.sign.ac.uk/what-we-do/methodology/search-filters/

-

Chin, Annelissa. “Searching Scopus for Randomised Control Trials” in Systematic Review Guide: http://libguides.nus.edu.sg/c.php?g=145717&p=2470589

Please note: The project librarian (Angela Hardi) should be included as an author on the systematic review manuscript if the search methods statement above or the search strategies listed below are included in the manuscript.

Citation Library Stats:

Original Search (10/2021)

Total number retrieved from database searches: 614

Number of duplicates removed: 304

Number of unique citations: 310

Updated Search (12/2022):

Total number retrieved from database searches: 307

Number of duplicates removed: 189 (149 duplicates found within updated search; 40 duplicates found between original and updated search)

Number of unique citations: 118

Total number of unique citations Original + Updated Search = 428

Complete Search Strategies:

Embase.com

=114 results on 10/7/2021; Results limited to English and Spanish; RCT filter used

Updated Search

= 66 results on 12/6/2022; Results limited to 2021–2023 and limited to English and Spanish, RCT filter used

(‘postnatal depression’/exp OR ‘postpartum anxiety’/exp OR (postpartum OR ‘post-partum’ OR postnatal OR ‘post natal’) NEAR/3 (depression OR depressive OR anxiety OR anxieties OR distress)) AND (‘mobile application’/exp OR ‘text messaging’/exp OR ‘telemedicine’/exp OR ‘smartphone’/de OR ‘web-based intervention’/exp OR ‘mobile application*’ OR ‘mobile app*’ OR ‘portable electronic app*’ OR ‘portable electronic app*’ OR ‘portable software app*’ OR ‘phone app*’ OR ‘tablet app*’ OR ‘text messag*’ OR texting* OR ‘SMS’ OR telemedicine OR ‘mobile health’ OR ‘mHealth’ OR ‘eMedicine’ OR telehealth OR smartphone* OR ‘smart phone*’ OR ‘cell phone*’ OR ‘mobile phone*’ OR iPhone* OR iPad* OR ‘tablet computer*’ OR ‘Android device*’ OR ‘Android phone*’ OR ‘internet intervention’ OR ‘internet based intervention’ OR ‘online intervention’ OR ‘web based intervention’ OR ‘digital intervention*’ OR ‘technology based’ OR ‘technology-based’) AND (‘clinical trial’/de OR ‘randomized controlled trial’/de OR ‘randomization’/de OR ‘single blind procedure’/de OR ‘double blind procedure’/de OR ‘crossover procedure’/de OR ‘placebo’/de OR ‘prospective study’/de OR ‘randomi?ed controlled’ NEXT/1 trial* OR rct OR ‘randomly allocated’ OR ‘allocated randomly’ OR ‘random allocation’ OR allocated NEAR/2 random OR single NEXT/1 blind* OR double NEXT/1 blind* OR (treble OR triple) NEAR/1 blind* OR placebo*) AND ([english]/lim OR [spanish]/lim)

Ovid-Medline All

=86 results on 10/7/2021 (results limited to English and Spanish); RCT filter used

Updated search

= 45 results on 12/6/2022; Results limited to 2021–2023 and limited to English and Spanish, RCT filter used

(Depression, Postpartum/ OR ((postpartum OR “post-partum” OR postnatal OR “post natal”) adj3 (depression OR depressive OR anxiety OR anxieties OR distress)).mp.) AND (Mobile Applications/ OR Text Messaging/ OR exp Telemedicine/ OR Smartphone/ OR Internet-Based Intervention/ OR (“mobile application*” OR “mobile app*” OR “portable electronic app*” OR “portable electronic app*” OR “portable software app*” OR “phone app*” OR “tablet app*” OR “text messag*” OR texting* OR “SMS” OR telemedicine OR “mobile health” OR mHealth OR eMedicine OR telehealth OR smartphone* OR “smart phone*” OR “cell phone*” OR “mobile phone*” OR iPhone* OR iPad* OR “tablet computer*” OR “Android device*” OR “Android phone*” OR “internet intervention” OR “internet based intervention” OR “online intervention” OR “web based intervention” OR “digital intervention*” OR “technology-based” OR “technology based”).ti,ab.) AND (randomized controlled trial.pt. OR controlled clinical trial.pt. OR randomized.ab. OR placebo.ab. OR drug therapy.fs. OR randomly.ab. OR trial.ab. OR groups.ab.)

CINAHL Plus

= 71 results on 10/7/2021; Limited to English and Spanish; RCT filter used

Updated Search

= 26 results on 12/6/2022; Results limited to 2021-present and limited to English and Spanish, RCT filter used

| # | Query | Limiters/Expanders Results |

|---|---|---|

| S4 | S1 AND S2 AND S3 | 73 |

| S3 | (TX allocat* random* OR (MH “Quantitative Studies”) OR (MH “Placebos”) OR TX placebo* OR TX random* allocat* OR (MH “Random Assignment”) OR TX randomi* control* trial* OR TX ( (singl* n1 blind*) OR (singl* n1 mask*) ) OR TX ( (doubl* n1 blind*) OR (doubl* n1 mask*) ) OR TX ( (tripl* n1 blind*) OR (tripl* n1 mask*) ) OR TX ( (trebl* n1 blind*) OR (trebl* n1 mask*) ) OR TX clinic* n1 trial* OR PT Clinical trial OR (MH “Clinical Trials+”)) | 1,613,627 |

| S2 | ((MH “Telemedicine”) OR (MH “Smartphone”) OR (MH “Text Messaging”) OR (MH “Mobile Applications”) OR (MH “Internet-Based Intervention”) OR “mobile application*” OR “mobile app*” OR “portable electronic app*” OR “portable electronic app*” OR “portable software app*” OR “phone app*” OR “tablet app*” OR “text messag*” OR texting* OR “SMS” OR telemedicine OR “mobile health” OR “mHealth” OR “eMedicine” OR telehealth OR smartphone* OR “smart phone*” OR “cell phone*” OR “mobile phone*” OR iPhone* OR iPad* OR “tablet computer*” OR “Android device*” OR “Android phone*” OR “internet intervention” OR “internet based intervention” OR “online intervention” OR “web based intervention” OR “digital intervention*” OR “technology-based” OR “technology based”) | 59,445 |

| S1 | ((MH “Depression, Postpartum”) OR ((postpartum OR “post-partum” OR postnatal OR “post natal”) N3 (depression OR depressive OR anxiety OR anxieties OR distress)) | 11,604 |

PsycInfo

=50 results on 10/7/2021; Limited to English and Spanish; RCT filter used

Updated Search

= 13 results on 12/6/2022; Results limited to 2021–2022, RCT filer used

(DE “Postpartum Depression” OR (postpartum OR “post-partum” OR postnatal OR “post natal”) N3 (depression OR depressive OR anxiety OR anxieties OR distress)) AND ((DE “Mobile Applications”) OR (DE “Text Messaging”) OR (DE “Telemedicine”) OR (DE “Smartphones”) OR (DE “Digital Interventions”) OR “mobile application*” OR “mobile app*” OR “portable electronic app*” OR “portable electronic app*” OR “portable software app*” OR “phone app*” OR “tablet app*” OR “text messag*” OR texting* OR “SMS” OR telemedicine OR “mobile health” OR “mHealth” OR “eMedicine” OR telehealth OR smartphone* OR “smart phone*” OR “cell phone*” OR “mobile phone*” OR iPhone* OR iPad* OR “tablet computer*” OR “Android device*” OR “Android phone*” OR “internet intervention” OR “internet based intervention” OR “online intervention” OR “web based intervention” OR “digital intervention*” OR “technology-based” OR “technology based”) AND ((TX allocat* random* OR (MH “Quantitative Studies”) OR (MH “Placebos”) OR TX placebo* OR TX random* allocat* OR (MH “Random Assignment”) OR TX randomi* control* trial* OR TX ( (singl* n1 blind*) OR (singl* n1 mask*) ) OR TX ( (doubl* n1 blind*) OR (doubl* n1 mask*) ) OR TX ( (tripl* n1 blind*) OR (tripl* n1 mask*) ) OR TX ( (trebl* n1 blind*) OR (trebl* n1 mask*) ) OR TX clinic* n1 trial* OR PT Clinical trial OR (MH “Clinical Trials+”)))

Scopus

=121 results on 10/7/2021; Limited to English and Spanish; RCT filter used

Updated search

= 84 results on 12/6/2022; Results limited to 2021–2022 and English and Spanish; RCT filter used

TITLE-ABS-KEY((postpartum OR “post-partum” OR postnatal OR “post natal”) W/3 (depression OR depressive OR anxiety OR anxieties OR distress)) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(“mobile application*” OR “mobile app*” OR “portable electronic app*” OR “portable electronic app*” OR “portable software app*” OR “phone app*” OR “tablet app*” OR “text messag*” OR texting* OR “SMS” OR telemedicine OR “mobile health” OR “mHealth” OR “eMedicine” OR telehealth OR smartphone* OR “smart phone*” OR “cell phone*” OR “mobile phone*” OR iPhone* OR iPad* OR “tablet computer*” OR “Android device*” OR “Android phone*” OR “internet intervention” OR “internet based intervention” OR “online intervention” OR “web based intervention” OR “digital intervention*” OR “technology-based” OR “technology based”) AND ( ( INDEXTERMS ( “clinical trials” OR “clinical trials as a topic” OR “randomized controlled trial” OR “Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic” OR “controlled clinical trial” OR “Controlled Clinical Trials” OR “random allocation” OR “Double-Blind Method” OR “Single-Blind Method” OR “Cross-Over Studies” OR “Placebos” OR “multicenter study” OR “double blind procedure” OR “single blind procedure” OR “crossover procedure” OR “clinical trial” OR “controlled study” OR “randomization” OR “placebo” ) ) OR ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( “clinical trials” OR “clinical trials as a topic” OR “randomized controlled trial” OR “Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic” OR “controlled clinical trial” OR “Controlled Clinical Trials as Topic” OR “random allocation” OR “randomly allocated” OR “allocated randomly” OR “Double-Blind Method” OR “Single-Blind Method” OR “Cross-Over Studies” OR “Placebos” OR “cross-over trial” OR “single blind” OR “double blind” OR “factorial design” OR “factorial trial” ) ) ) OR ( TITLE-ABS ( clinical AND trial* OR trial* OR rct* OR random* OR blind* ) ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , “English” ) OR LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE , “Spanish” ) )

Cochrane Library: Central Trials