Abstract

The prevalence of highly repetitive sequences within the human Y chromosome has prevented its complete assembly to date1 and led to its systematic omission from genomic analyses. Here, we present de novo assemblies of 43 Y chromosomes spanning 182,900 years of human evolution and report remarkable diversity in size and structure. Half of the male-specific euchromatic region is subject to large inversions with a >2-fold higher recurrence rate compared to all other chromosomes2. Ampliconic sequences associated with these inversions further show differing mutation rates that are sequence context-dependent and some ampliconic genes exhibit evidence for concerted evolution with the acquisition and purging of lineage-specific pseudogenes. The largest heterochromatic region in the human genome, the Yq12, is composed of alternating repeat arrays that show extensive variation in the number, size and distribution, but retain a 1:1 copy number ratio. Finally, our data suggests that the boundary between the recombining pseudoautosomal region 1 and the non-recombining portions of the X and Y chromosomes lies 500 kbp away from the currently established1 boundary. The availability of fully sequence-resolved Y chromosomes from multiple individuals provides a unique opportunity for identifying new associations of traits with specific Y-chromosomal variants and garnering novel insights into the evolution and function of complex regions of the human genome.

Introduction

The mammalian sex chromosomes evolved from a pair of autosomes, gradually losing their ability to recombine with each other over increasing lengths, leading to degradation and accumulation of large proportions of repetitive sequences on the Y chromosome3. The resulting sequence composition of the human Y chromosome is rich in complex repetitive regions, including highly similar segmental duplications (SDs)1,4. This has made the Y chromosome difficult to assemble, and, paired with reduced gene content, has led to its systematic neglect in genomic analyses.

The first human Y chromosome sequence assembly was generated almost 20 years ago, which provided a high quality but incomplete sequence (53.8% or ~30.8/57.2 Mbp unresolved in GRCh38 Y)1. Less than half (~25 Mbp) of the GRCh38 Y chromosome is composed of euchromatin, which contains two pseudoautosomal regions, PAR1 and PAR2 (~3.2 Mbp in total), that actively recombine with homologous regions on the X chromosome and are therefore not considered as part of the male-specific Y region (MSY)1. The remainder of the Y-chromosomal euchromatin (~22 Mbp) has been divided into three main classes according to their sequence composition and evolutionary history1: (i) the X-degenerate regions (XDR, ~8.6 Mbp) are remnants of the ancient autosome from which the X and Y chromosomes evolved, (ii) the X-transposed regions (XTR, ~3.4 Mbp) resulted from a duplicative transposition event from the X chromosome followed by an inversion, and (iii) the ampliconic regions (~9.9 Mbp) that contain sequences having up to 99.9% intra-chromosomal identity across tens or hundreds of kilobases (Fig. 1a). Besides the euchromatin, the Y contains a large proportion of repetitive and heterochromatic sequences, including the (peri-)centromeric DYZ3 α-satellite and DYZ17 arrays, DYZ18 and DYZ19 arrays, and the largest contiguous heterochromatic block in the human genome, Yq12, which is known to be highly variable in size1,5,6. All of these heterochromatic regions are thought to be composed predominantly of satellites, simple repeats, and SDs1,7.

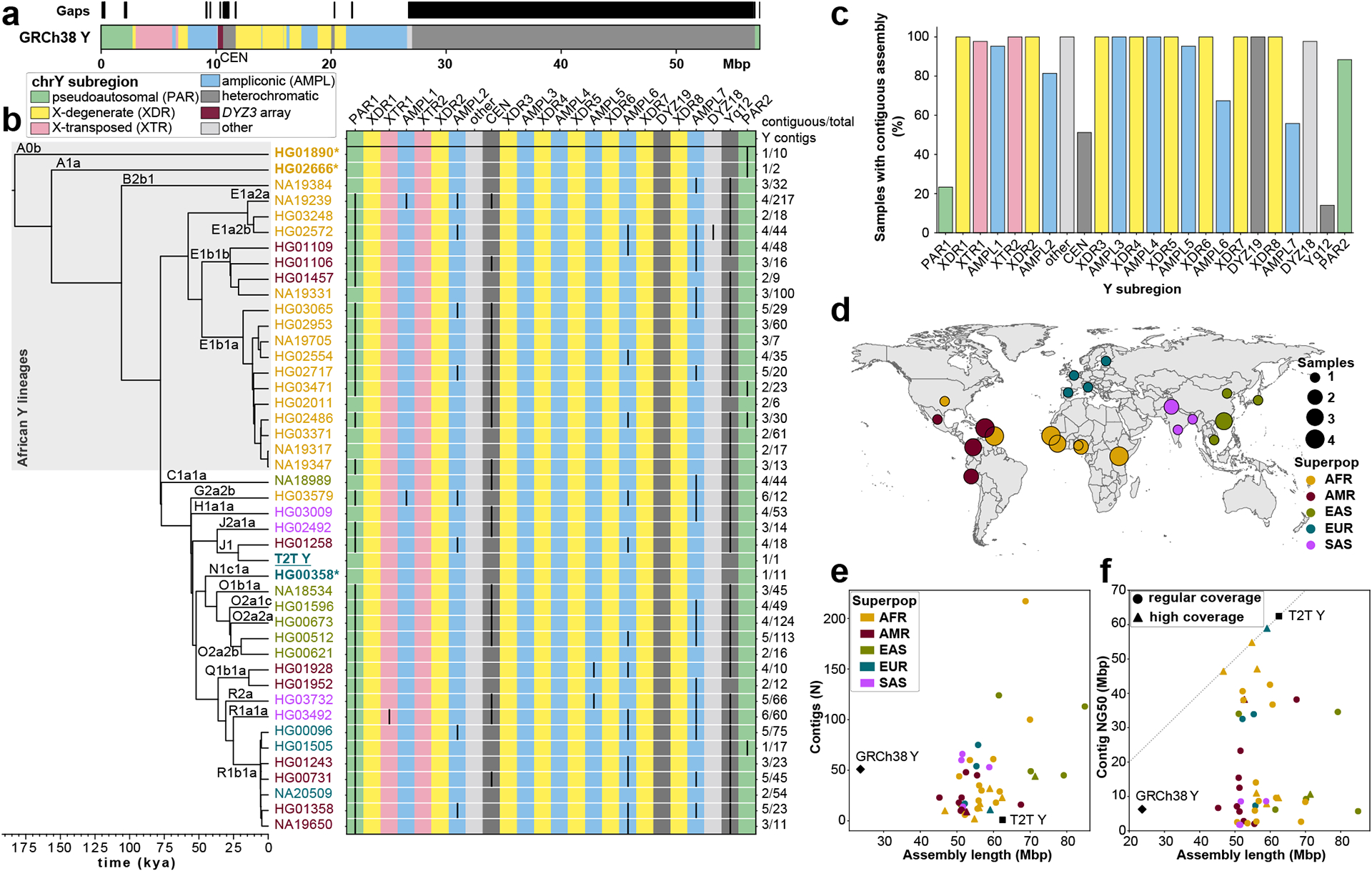

Fig. 1. De novo assembly outcome.

a. Human Y chromosome structure based on the GRCh38 Y reference sequence.

b. Phylogenetic relationships (left) with haplogroup labels of the analysed Y chromosomes with branch lengths drawn proportional to the estimated times between successive splits (see Fig. S1 and Table S1 for additional details). Summary of Y chromosome assembly completeness (right) with black lines representing non-contiguous assembly of that region (Methods). Numbers on the right indicate the number of Y contigs needed to achieve the indicated contiguity/total number of assembled Y contigs for each sample. CEN - centromere - includes the DYZ3 α-satellite array and the pericentromeric region. Three contiguously assembled Y chromosomes are in bold and marked with an asterisk (assemblies for HG02666 and HG00358 are contiguous from telomere to telomere, while HG01890 assembly has a break approximately 100 kbp before the end of PAR2) and the T2T Y is in bold and underlined. The colour of sample ID corresponds to the superpopulation designation (see panel d). Note - GRCh38 Y sequence mostly represents Y haplogroup R1b.

c. The proportion of contiguously assembled Y-chromosomal subregions across 43 samples.

d. Geographic origin and sample size of the included 1000 Genomes Project samples coloured according to the continental groups (AFR, African; AMR, American; EUR, European; SAS, South Asian; EAS, East Asian). Superpop - super population.

e. Y-chromosomal assembly length vs. number of Y contigs. Gap sequences (N’s) were excluded from GRCh38 Y.

f. Y-chromosomal assembly length vs. Y contig NG50. High coverage defined as >50⨉ genome-wide PacBio HiFi read depth. Gap sequences (N’s) were excluded from GRCh38 Y.

Recent attempts have been made to assemble the human Y chromosome using Illumina short-read8 and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) long-read data9, but a contiguous assembly of the ampliconic and heterochromatic regions was not achieved. In April 2022, the first complete de novo assembly of a human Y chromosome was reported by the Telomere-to-Telomere (T2T) Consortium10 (from individual HG002/NA24385, carrying a rare J1a-L816 Y lineage found among Ashkenazi Jews and Europeans11, termed as T2T Y). However, understanding the composition and appreciating the complexity of the Y chromosomes in the human population requires availability of assemblies from many diverse individuals. Here, we combined PacBio HiFi and ONT long-read sequence data to assemble the Y chromosomes from 43 males, representing the five continental groups from the 1000 Genomes Project. While both the GRCh38 (mostly R1b-L20 haplogroup) and the T2T Y represent European Y lineages, half of our Y chromosomes constitute African lineages and include most of the deepest-rooted human Y lineages. This newly assembled dataset of 43 Y chromosomes thus provides a more comprehensive view of genetic variation, at the nucleotide level, across over 180,000 years of human Y chromosome evolution.

Results

Sample Selection

We selected 43 genetically diverse males from the 1000 Genomes Project, representing 21 largely African haplogroups (A, B and E, including deep-rooted lineages A0b-L1038, A1a-M31 and B2b-M112)12,13 (Figs. 1b,d; Fig. S1; Table S1; Methods). The time to the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) among our 43 Y chromosomes and the T2T Y was estimated to be approximately 183 thousand years ago (kya) (95% highest posterior density [HPD] interval: 160–209 kya) (Fig. S1), consistent with previous reports14,15. A pair of closely related African Y chromosomes (NA19317 and NA19347, lineage E1b1a1a1a-CTS8030), was included for assembly validation, as these Y chromosomes are expected to be highly similar (TMRCA 200 years ago (ya) [95% HPD interval: 0 – 500 ya]).

Constructing De Novo Assemblies

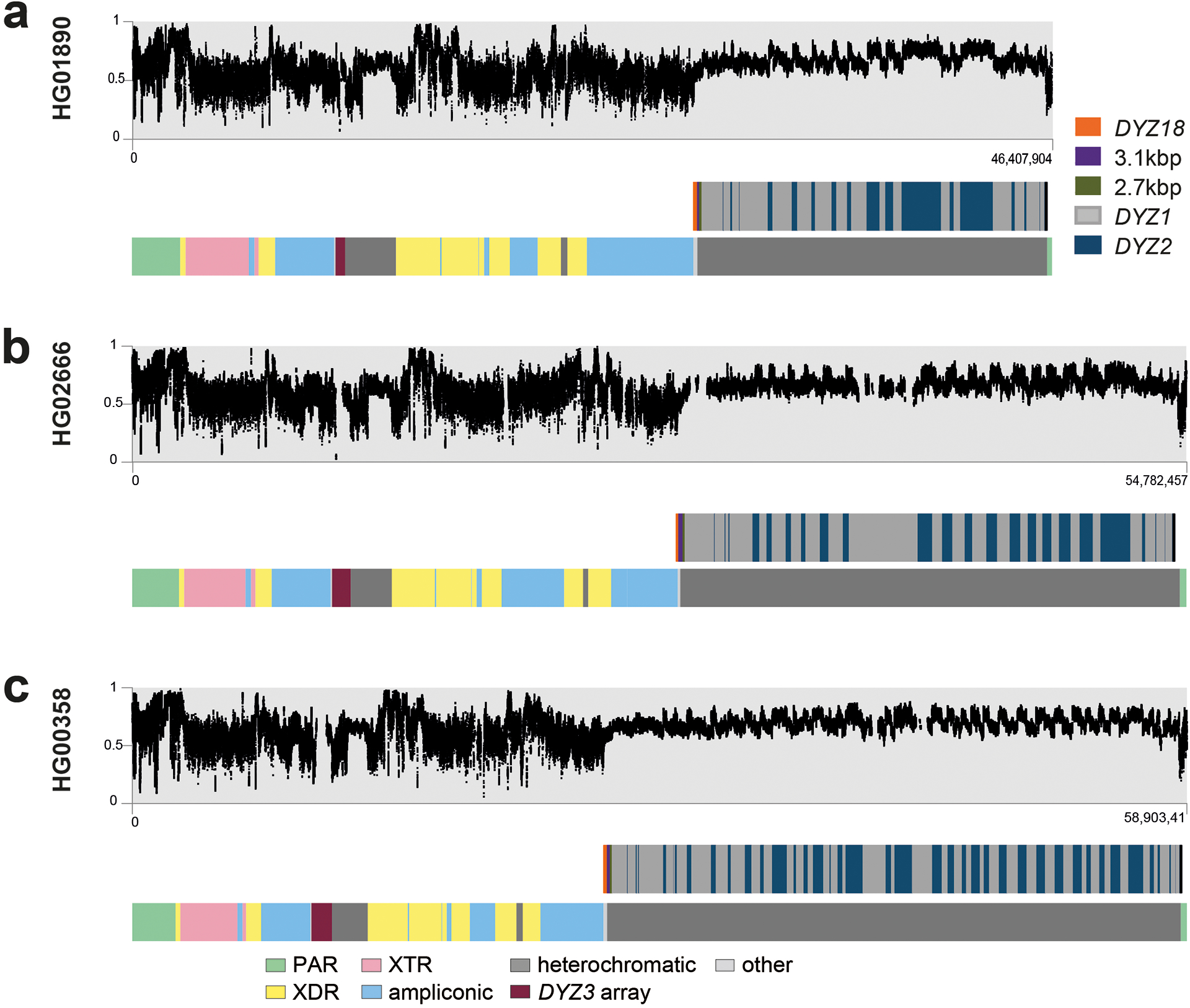

We employed the hybrid assembler Verkko16 to generate Y chromosome assemblies, including the ampliconic and heterochromatic regions (Methods). Verkko leverages the high accuracy of PacBio HiFi reads (>99.8% base-pair calling accuracy17,18) with the length of ONT long/ultra-long reads (median read length N50 134 kbp) to produce highly accurate and contiguous assemblies (Table S2). Using this approach, we generated high-quality (median QV 48; Table S3) whole-genome (median length 5.9 Gbp; Table S4) assemblies for the 43 males studied. The chromosome Y sequences exhibit a high degree of completeness (median length 55.6 Mbp, 79% to 148% assembly length relative to GRCh38 Y; Fig. 1; Fig. S2; Tables S5–S6), contiguity (median NG50 9.6 Mbp, median LG50 2, Table S4), base-pair quality (median QV 46, Table S3), and read-depth profile consistency with the autosomal sequences in the assemblies (Fig. S3, Table S7). The Verkko assembly process was robust (sequence identity for NA19317/NA19347 pair of 99.9959%, Fig. S4; Table S8; Supplementary Results ‘De novo assembly evaluation’). We generated a gapless Y chromosome assembly, spanning from PAR1 to PAR2, for three individuals, two of which represent deep-rooted African haplogroups (Figs. 1b, 2; Table S9). These three samples are among nine samples with an increased HiFi coverage of at least 50⨉ (“high-coverage samples”; Tables S1–S2, S7).

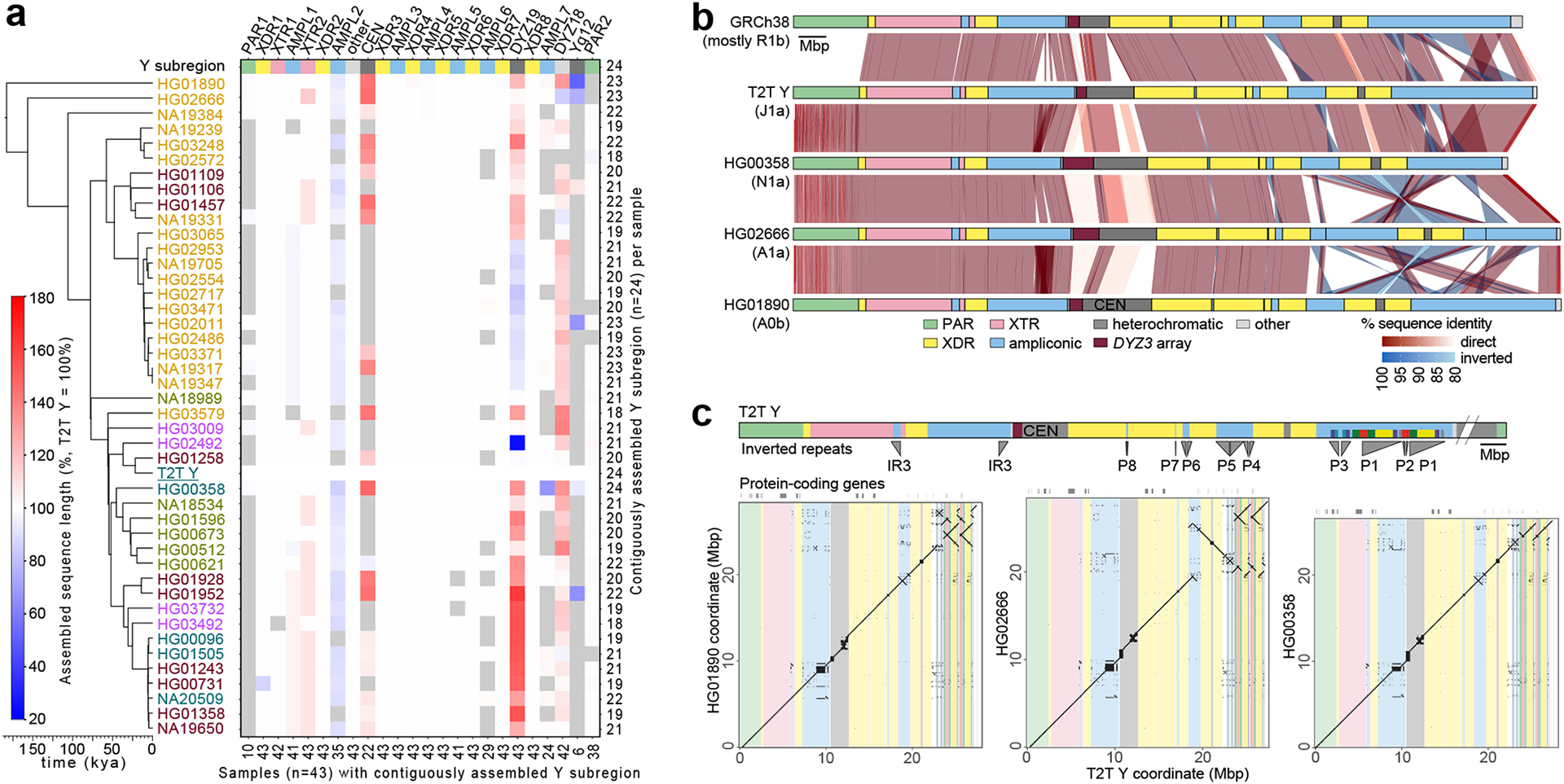

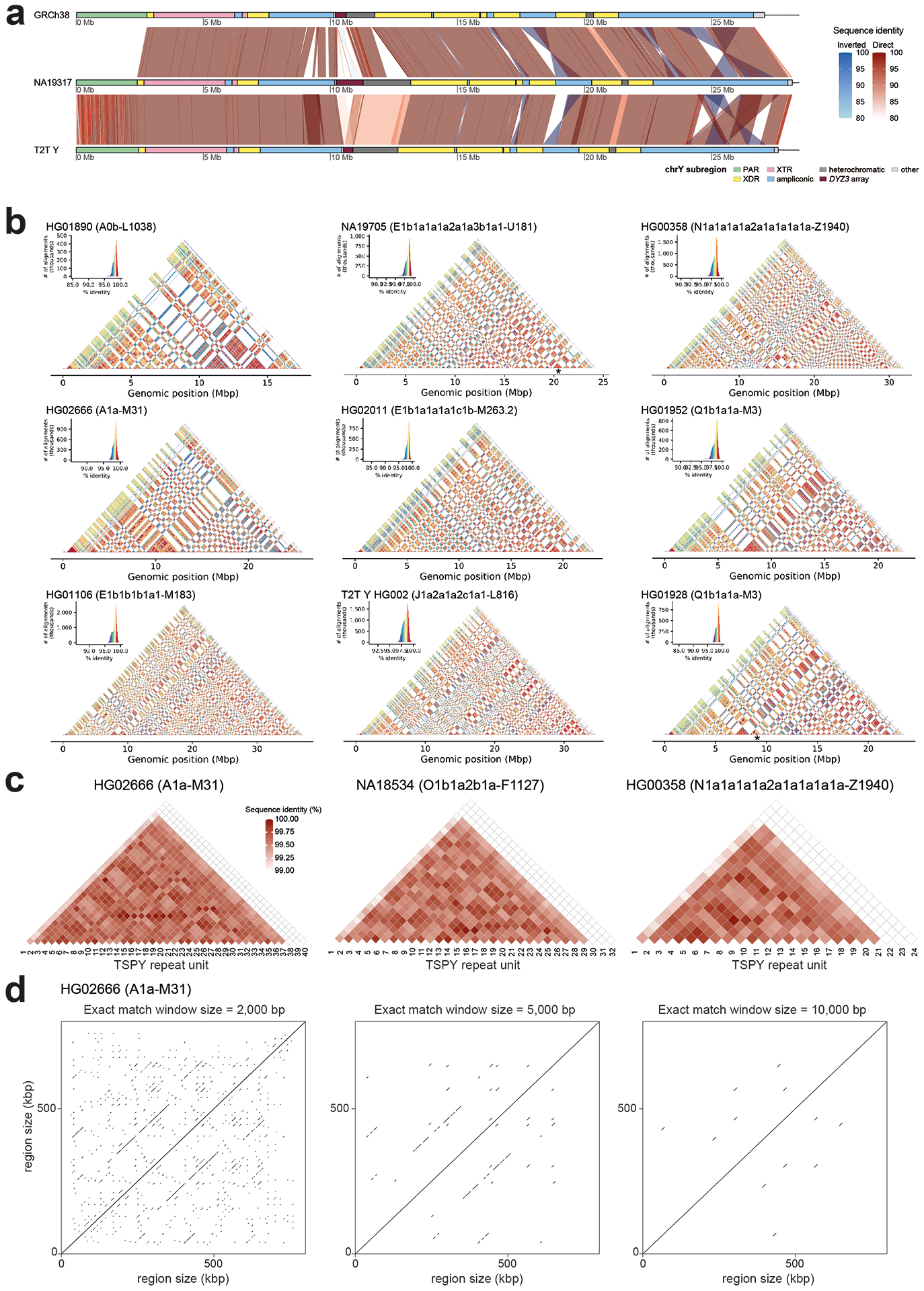

Fig. 2. Size and structural variation of Y chromosomes.

a. Size variation of contiguously assembled Y-chromosomal subregions shown as a heatmap relative to the T2T Y size (as 100%). Boxes in grey indicate regions not contiguously assembled (Methods). Numbers on the bottom indicate contiguously assembled samples for each subregion out of a total of 43 samples, and numbers on the right indicate the contiguously assembled Y subregions out of 24 regions for each sample. Samples are coloured as on Fig. 1b.

b. Comparison of the three contiguously assembled Y chromosomes to GRCh38 and the T2T Y (excluding Yq12 and PAR2 subregions).

c. Dot plots of three contiguously assembled Y chromosomes vs. the T2T Y (excluding Yq12 and PAR2), annotated with Y subregions and segmental duplications in ampliconic subregion 7 (see Fig. S34 for details).

Following established procedures19–21, we flagged potentially erroneous regions, comprising 0.103% (median; mean 0.31%) up to 0.186% (median; mean 0.467%) of the assembled Y sequence (Fig. S5, Tables S10–S12; Methods). Although the error rate is increased for the lower-coverage assemblies, increasing the HiFi coverage beyond 50⨉ has limited effect on the error rate (Fig. S6).

We further annotated each of the Y-chromosomal assemblies with respect to the 24 Y-chromosomal subregions originally proposed by Skaletsky and colleagues1 (Figs. 1a–c; Fig. S2; Table S13; Methods). In addition to the three gapless Y chromosomes, we contiguously assembled the MSY excluding Yq12 and the (peri-)centromeric region for 17/43 samples (Tables S9, S14–S16). Overall, 17/24 subregions were contiguously assembled across 41/43 samples (Figs. 1b–c; Fig. S2).

Diversity of assembled Y chromosomes

Size variation of the assembled Y chromosomes.

The assembled Y chromosomes showed extensive variation both in size and structure (Figs. 2a–c, 3, 4 and 5; Extended Data Fig. 1a; Fig. S7–S18; Methods) with chromosome sizes ranging from 45.2 to 84.9 Mbp (mean 57.6 and median 55.7 Mbp, Fig. S16; Table S14, S16; Methods). This is, however, a slight underestimate of the true Y-chromosomal size due to assembly gaps. An analysis of the underlying assembly graphs suggest that the paths of complete assemblies would be, on average, 1.15% longer (Table S6; Supplementary Results ‘De novo assembly evaluation’). Among the gaplessly assembled Y-chromosomal subregions (including for the T2T Y), the largest variation in subregion size was seen for the heterochromatic Yq12 (17.6 to 37.2 Mbp, mean 27.6 Mbp), the (peri-)centromeric region (2.0 to 3.1 Mbp, mean 2.6 Mbp) and the DYZ19 repeat array (63.5 to 428 kbp, mean 307 kbp) (Figs. 2a, 5f; Extended Data Fig. 1b; Figs. S7, S16–S21; Tables S14–S16).

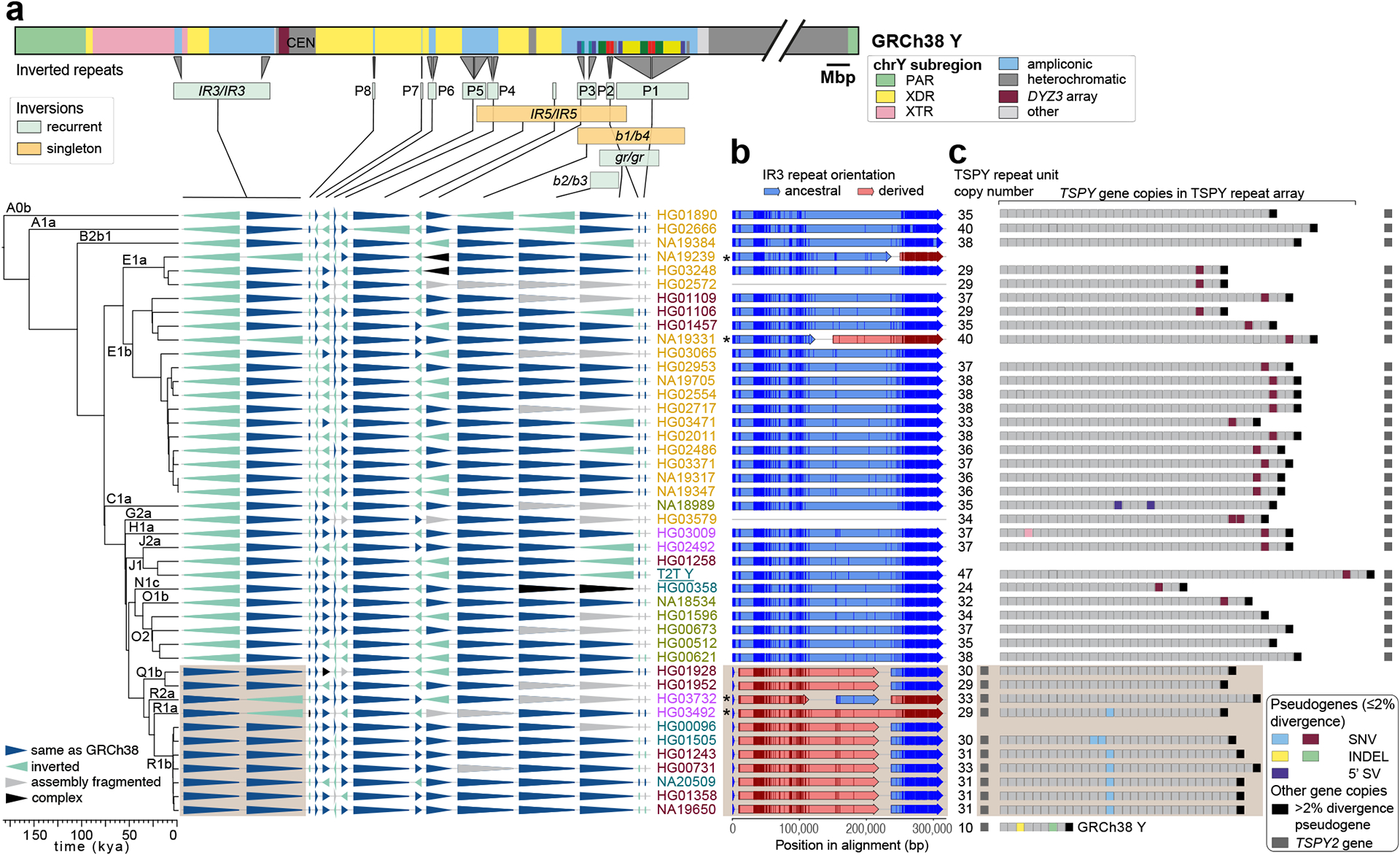

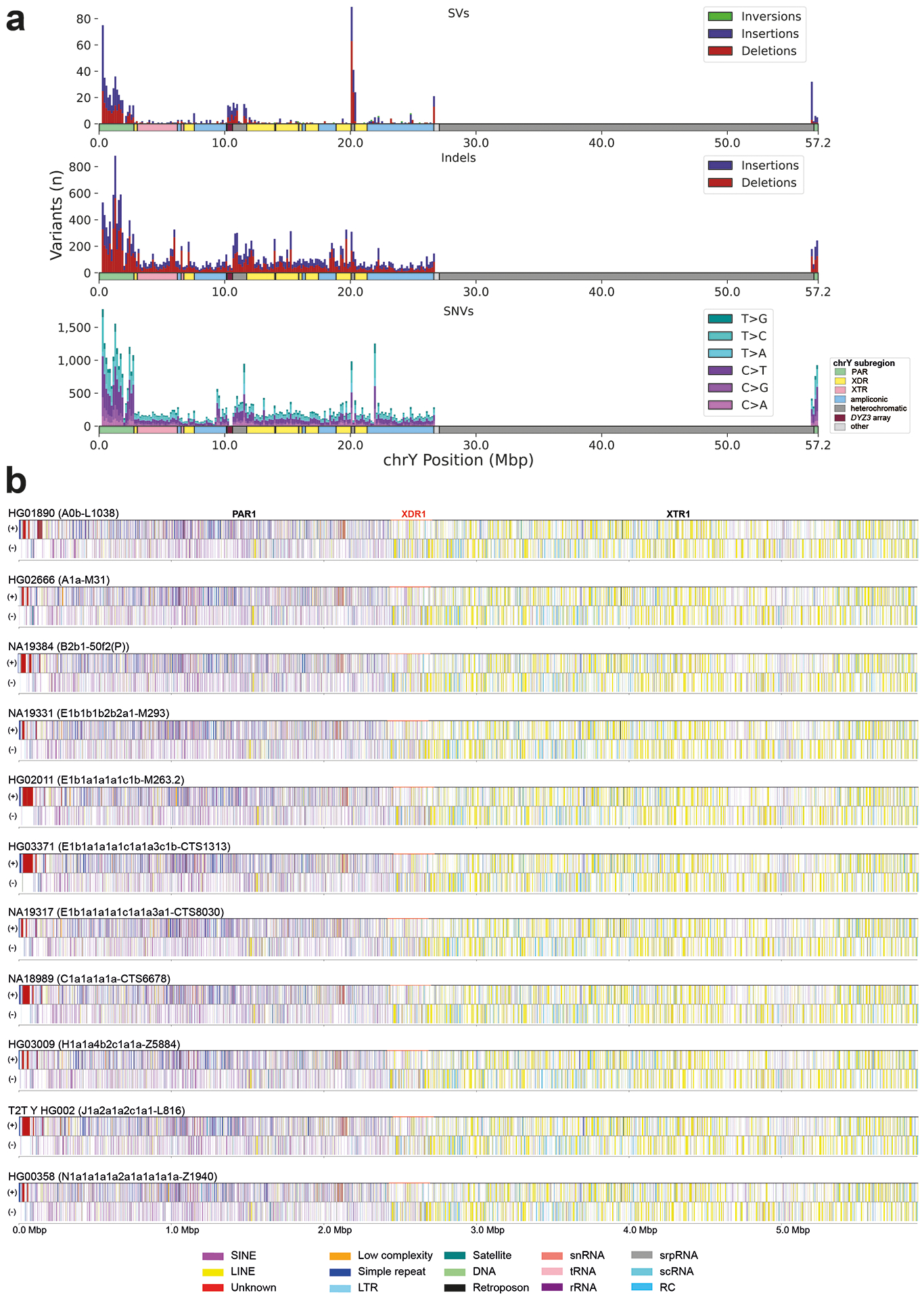

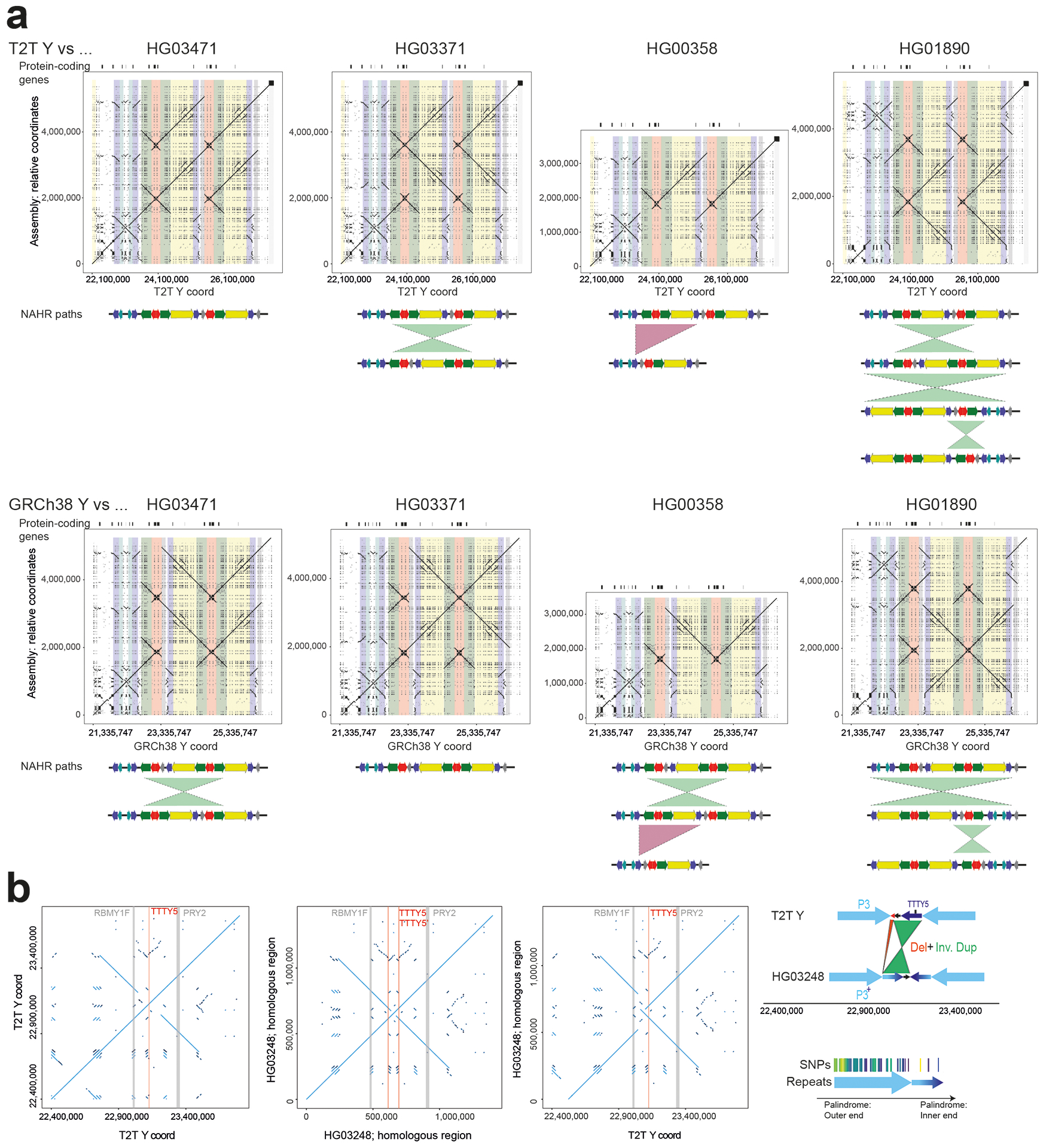

Fig. 3. Characterization of large SVs.

a. Distribution of 14 euchromatic inversions in phylogenetic context, with the schematic of the GRCh38 Y structure shown above, annotated with Y subregions, inverted repeat locations, palindromes (P1-P8), and segmental duplications in ampliconic subregion 7 (see Fig. S34 for details), with inverted segments indicated below. Samples are coloured as in Fig. 1b.

b. Inversion breakpoint identification in the IR3 repeats. Light brown box (also in a and c) indicates samples that have likely undergone two inversions: one changing the location of the single, TSPY2 gene-containing, repeat unit from proximal to distal IR3 repeat and second reversing the region between the IR3 repeats, shared by haplogroup QR samples (Fig. S34, Supplementary Results ‘Y-chromosomal Inversions’). Asterisks indicate samples that have undergone an additional IR3 inversion. Informative PSVs are shown as vertical darker lines in each of the arrows. Samples with non-contiguous IR3 assembly are indicated by grey lines.

c. Distribution of pseudogenes within the TSPY repeat array. The total number of TSPY genes located within the ~20.3 kbp TSPY repeat units is shown on the left. Samples marked with asterisks in b carry the TSPY array in reverse orientation and were reoriented for visualization. The low divergence (≤2%) pseudogenes (coloured boxes) originate from five events: two nonsense mutations (light blue, maroon), two one nucleotide indel deletions (yellow, green), and one 5’ structural variation that deletes ~370 nucleotides of the proximal half of exon 1 (purple). An additional sixth event was identified (i.e., a premature stop codon within the fourth TSPY copy in the array of HG03009, in pink), but was deemed unlikely to result in nonsense-mediated decay as it was located only three codons before the canonical stop codon. Refer to panel a for sample IDs and phylogenetic relationships.

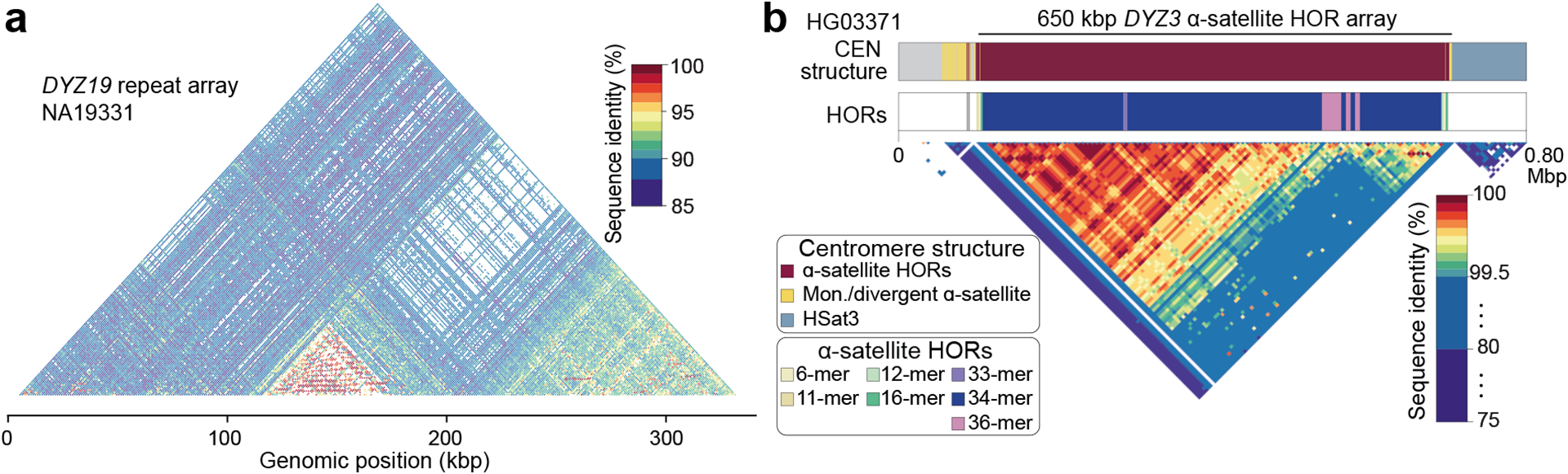

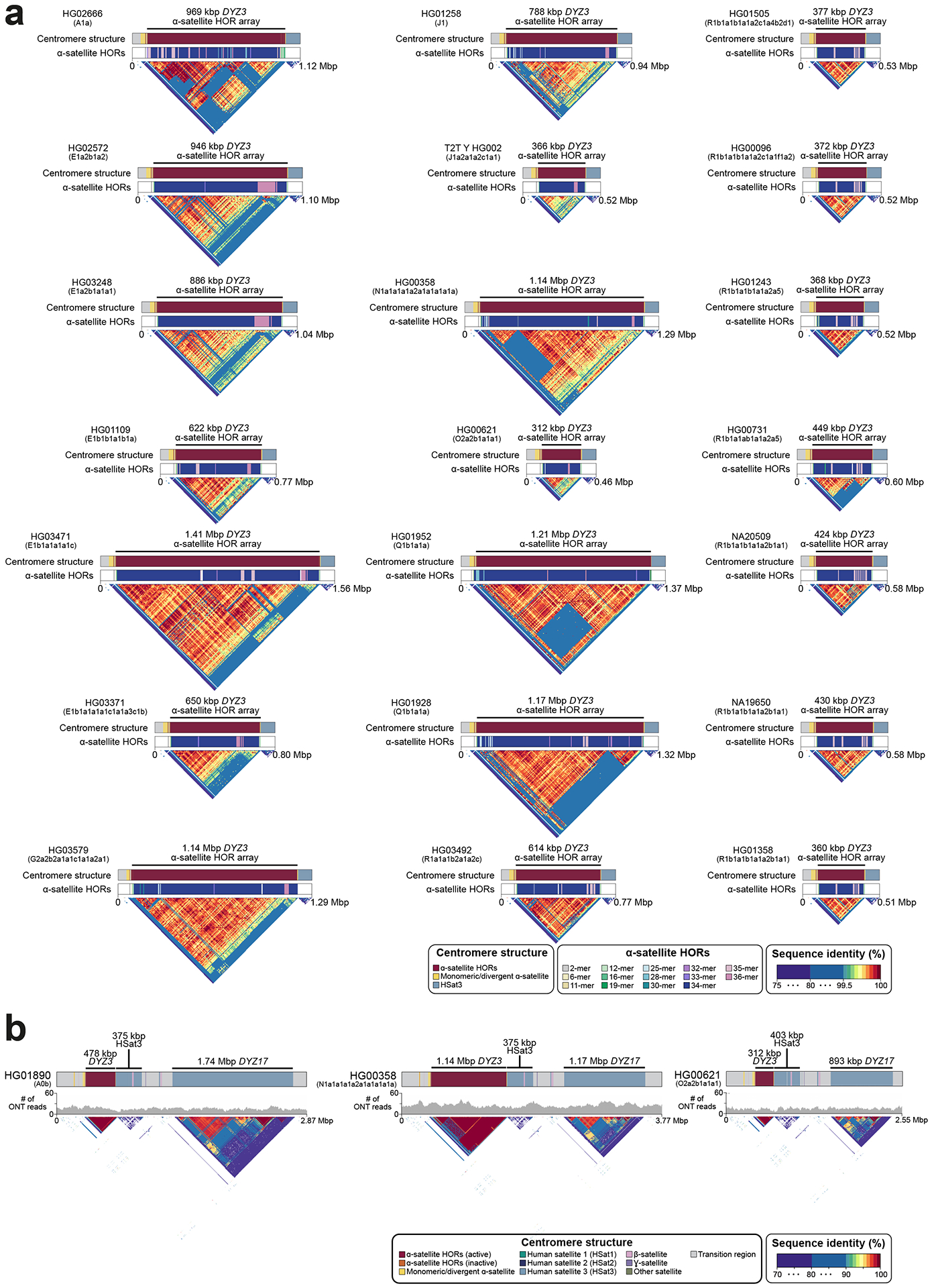

Fig. 4. DYZ19 and centromeric repeat arrays.

a. Sequence identity heatmap of the DYZ19 repeat array from NA19331 (E1b1b1b2b2a1-M293) (using 1 kbp window size) highlighting the higher sequence similarity within central and distal regions.

b. Genetic landscape of the chromosome Y centromeric region from HG03371 (E1b1a1a1a1c1a-CTS1313). This centromere harbours the ancestral 36-monomer higher-order repeats (HORs), from which the canonical 34-monomer HOR is derived (Fig. S46). Mon - monomer; CEN - centromere.

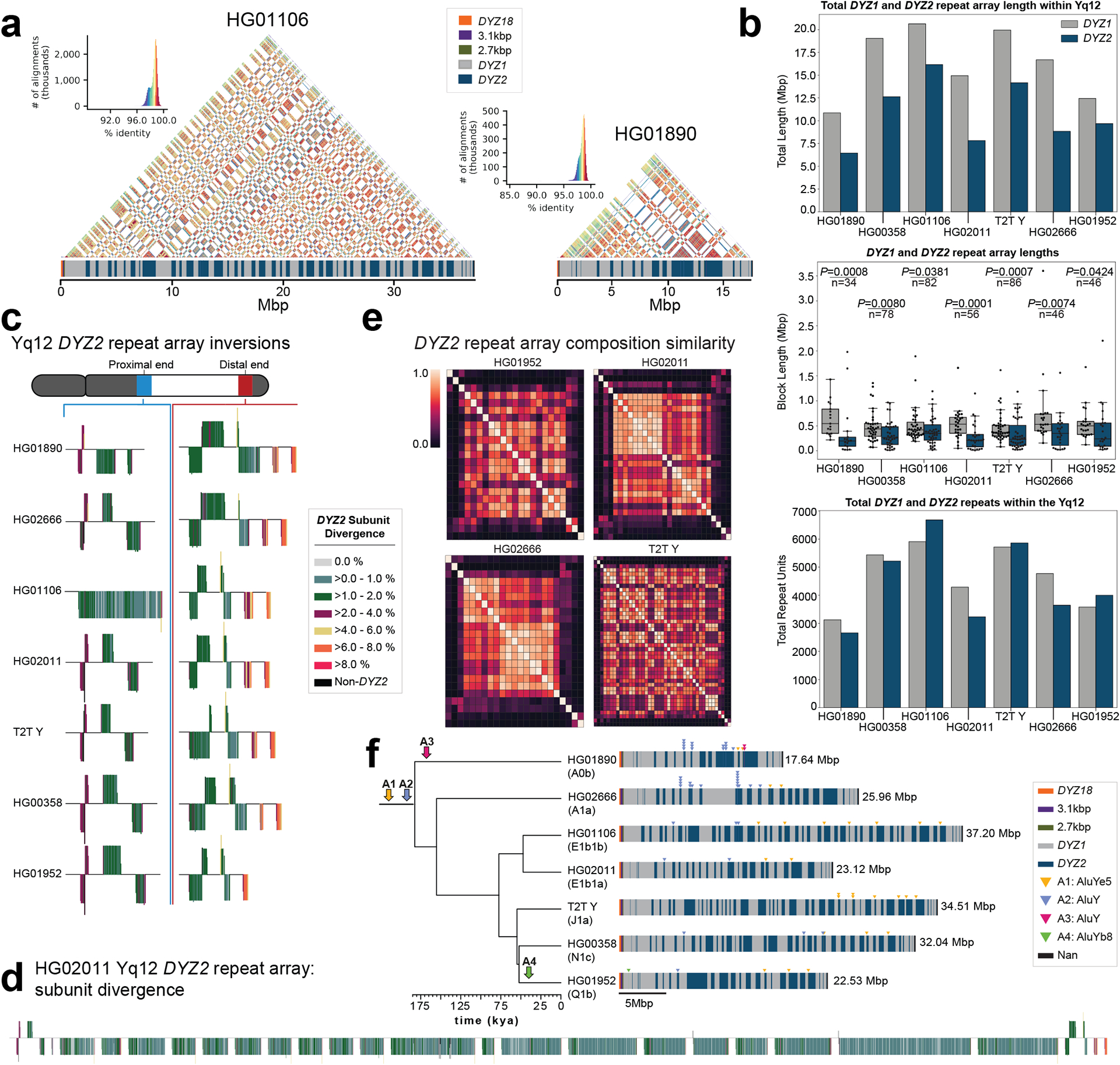

Fig. 5. Yq12 heterochromatic region.

a. Yq12 heterochromatic subregion sequence identity heatmap in 5 kbp windows for two samples with repeat array annotations.

b. Bar plot of DYZ1 and DYZ2 total repeat array lengths (top), boxplots of individual array lengths (middle) and total number of DYZ1 and DYZ2 repeat units (bottom) within contiguously assembled genomes. Black dots represent individual arrays. Statistically significant p-values comparing DYZ1 and DYZ2 array lengths within each assembly and n values are shown (alpha=0.05, two-sided Mann-Whitney U test, Methods). Boxplot limits indicate quartiles, the whiskers encompass the full range of the data (except for ‘outliers’), and the median is indicated by the center line.

c. DYZ2 repeat array inversions in the proximal and distal ends of the Yq12 subregion. DYZ2 repeats are coloured based on their divergence estimate and visualized based on their orientation (sense - up, antisense - down).

d. Detailed representation of DYZ2 subunit divergence estimates for HG02011 (see panel c for colour legend).

e. Heatmaps showing the inter-DYZ2 repeat array subunit composition similarity within a sample. Similarity is calculated using the Bray-Curtis index (1 – Bray-Curtis Distance, 1.0 = the same composition). DYZ2 repeat arrays are shown in physical order from proximal to distal (from top down, and from left to right).

f. Mobile element insertions identified in the Yq12 subregion. We identified four putative Alu insertions across the seven gapless Yq12 assemblies. Their approximate location, as well as expansion and contraction dynamics of Alu insertion containing DYZ repeat units, are shown (right). Following the insertion into the DYZ repeat units, lineage-specific contractions and expansions occurred. Two Alu insertions (A1 and A2) occurred prior to the radiation of Y haplogroups (at least 180,000 years ago), while two additional Alu elements represent lineage-specific insertions. The total length of the Yq12 region is indicated on the right.

The euchromatic regions showed comparatively little variation in size (Fig. 2a; Fig. S7, Tables S14, S16) with exception of the ampliconic subregion 2 that contains a copy-number variable TSPY repeat array, composed of 20.3 kbp repeat units. The TSPY array size varies by up to 467 kbp between individuals (Extended Data Fig. 1c–d; Figs. S18, S22; Tables S15–S18; Supplementary Results ‘Gene family architecture and evolution’; Methods) and was consistently shorter among males within haplogroup QR (from 567 to 648 kbp, mean 603 kbp) compared to males in the other haplogroups (from 465 to 932 kbp, mean 701 kbp) (Figs. S18, S22–S25). The concordance of observed size variation with the phylogeny is well supported by relatively constant, phylogenetically-independent contrasts (PICs), across the phylogeny (Figs. S23–S24; Table S19; Methods). Such phylogenetic consistency reinforces the high quality of our assemblies even across homogeneous tandem arrays, as more closely related Y chromosomes are expected to be more similar, and this consequently allows investigation of mutational dynamics across well-defined timeframes.

Distribution and frequency of genetic variants.

We leveraged our assemblies to produce a set of variant calls for each Y chromosome, including structural variants (SVs), indels, and single-nucleotide variants (SNVs). In the MSY, we report on average 88 insertion and deletion SVs (≥50 bp), three large inversions (>1 kbp), 2,168 indels (<50 bp), and 3,228 SNVs per Y assembly (Extended Data Fig. 2a; Table S20; Methods) when compared to the GRCh38 Y reference. Variants were merged across all 43 samples to produce a nonredundant callset of 876 SVs (488 insertions, 378 deletions, 10 inversions), 23,459 indels (10,283 insertions, 13,176 deletions), and 53,744 SNVs (Tables S21–S25; Supplementary Results ‘Orthogonal support to Y-chromosomal SVs and copy number variation’). Based on SV insertions, we identified an average of 81 kbp (range of 46 to 155 kbp) of novel, non-reference sequences per Y chromosome. After excluding simple repeats and mobile element sequences, an average of 18 kbp (range of 0.6 to 47 kbp) of unique non-reference sequence per Y remained (Table S26).

Across the unique regions of the autosomes, we find 1.91 SVs, 165.66 indels, and 994.42 SNVs per Mbp per haplotype (Table S27, Methods). In the PAR1 region, on both the X and the Y chromosome, SV rates increased 1.98-fold to 3.79 SVs per Mbp (p = 2.37×10−5, Welch’s t-test) per haplotype, indels increased 1.56-fold to 259.14 per Mbp (p = 1.38×10−3, Welch’s t-test), and SNVs decreased slightly to 936.19 (p = 1.00, Welch’s t-test) across unique loci. While PAR1 has the same ploidy as the autosomes, it is much shorter (2.8 Mbp) and has a 10⨉ increased recombination rate in males compared to females22, which may lead to the observed higher density of SVs and indels. A reduced level of variation observed in the proximal 500 kbp before the currently-established PAR1 boundary could be the result of a lower recombination rate closer to the sex-specific chromosomal regions, indicating a more distal location for the actual PAR1 boundary (Figs. S26–S29). As expected, the human chromosome X (excluding both PAR regions) exhibits lower genetic variation with 1.16 SVs (p = 1.08×10−25 Student’s t-test), 106.64 indels (p = 9.29×10−46, Student’s t-test), and 584.93 SNVs (p = 8.23×10−83, Student’s t-test) per Mbp of unique loci with most differences likely attributed to a lower effective population size for the X chromosome. The MSY has even less variation than seen for the X chromosome, with an average of 0.01 SVs, 2.11 indels, and 5.72 SNVs per Mbp (p < 1×10−100 for all, Welch’s t-test) of unique loci (Table S27). Bonferroni correction was applied to all tests.

We also identified 21 mobile element insertions across the 43 Y-chromosomal assemblies that are not present in the GRCh38 Y, including 15 Alu elements (4/15 within the Yq12) and six LINE-1s (long interspersed element-1; no significant difference compared to the whole-genome distribution reported in20) (Fig. 5f; Tables S28–S29; Methods; Supplementary Results ‘Yq12 heterochromatic subregion’). Closer inspection across the three gaplessly assembled Y chromosomes, as well as the T2T Y chromosome, showed substantial differences in repeat composition between Y-chromosomal subregions (Fig. S30; Tables S30–S31). For example, the pseudoautosomal regions showed a clear increase in SINE (short interspersed element) content and reduction in LINE and LTR (long terminal repeat) content compared to the male-specific XTR, XDR, and ampliconic regions (Extended Data Fig. 2b; Fig. S30; Table S32).

Y-chromosomal inversions.

Large inversions were identified using Strand-seq23 and manual inspection of assembly alignments, yielding as many as 14 inversions in the euchromatic regions and two inversions within the Yq12 across the studied males (Figs. 3a, 5c; Extended Data Fig. 3; Tables S33–S35; Methods; Supplementary Results ‘Y-chromosomal Inversions’). Six of these matched the ten inversions identified above by variant calling (Table S23). The breakpoint intervals for 8/14 of the euchromatic inversions were refined to DNA regions as small as 500 bp (Fig. 3b; Figs. S31–33; Table S36; Methods). All these inversions are flanked by highly similar (up to 99.97%) and large (from 8.7 kbp to 1.45 Mbp) inverted SDs, and while determination of the molecular mechanism generating Y-chromosomal inversions remains challenging, most are likely a result of non-allelic homologous recombination (NAHR). Moreover, we found that most (12/14, 85%) euchromatic inversions are recurrent, with 2 to 13 toggling events in the Y phylogeny, which translates to an inversion rate estimate ranging from 3.68 ⨉ 10−5 (95% C.I.: 3.25 – 4.17 ⨉ 10−5) to 2.39 ⨉ 10−4 (95% C.I.: 2.11 – 2.71 ⨉ 10−4) per locus per father-to-son Y transmission. The highest inversion recurrence is seen among the eight Y-chromosomal palindromes (called P1-P8, Fig. 3a; Fig. S34; Table S33, Methods). Taken together, we calculate a rate of one recurrent inversion per 603 (95% C.I.: 533 – 684) father-to-son Y transmissions. The per site per generation rate estimates for 12 Y-chromosomal recurrent inversions are significantly higher (>2-fold difference between median estimates, two-tailed Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test, n=44, p-value <0.0001) than the rates previously estimated for 32 autosomal and X-chromosomal recurrent inversions2.

There are two fixed inversions flanking the Yq12 subregion (Fig. 5c; Fig. S35; Table S35; Supplementary Results ‘Y-chromosomal Inversions’). The proximal inversion, observed in 10/11 individuals analyzed, ranged from 358.9 to 820.7 kbp in size (mean 649.0 kbp) (Table S35). The distal inversion, on the other hand, was observed in all 11 individuals and ranged from 259.5 to 641.4 kbp in size (mean 472.5 kbp). We found the breakpoints for these two inversions to be identical among all individuals. This suggests that the consistent presence of these two inversions at both ends of the Yq12 subregion may prevent unequal sister chromatid exchange from occurring, restricting expansion and contraction of the repeat units to the region flanked by these two inversions.

Evolution of palindromes and multi-copy gene families.

To further reconstruct the evolution of Y-chromosomal palindromes, we investigated both the gene conversion patterns and evolutionary rates across the Y assemblies (Figs. S36–S38; Tables S15, S37–S38). The intra-arm gene conversion patterns across seven palindromes (P1, P3-P8, but excluding the P2 palindrome and DNA sequences that are shared between different palindromes; Methods) showed a significant bias towards G or C nucleotides (942 events to G or C vs. 701 to A or T nucleotides, p=2.75 × 10−9, Chi-square test), but no bias towards the ancestral state (357 events to derived vs. 374 to ancestral state; P=0.5295, Chi-square test; Table S37). Comparison of base substitution patterns for all eight palindromes and the eight XDR regions, across 13 Y chromosomes, indicated that different palindromes are evolving at different rates (Methods). The level of sequence variation (both in base substitutions and SVs) and estimated base substitution mutation rates were higher for palindromes P1, P2 and P3, which contain higher proportions of multicopy (i.e., >2 copies) segments compared to other palindromes (3.03 × 10−8 (95% C.I.: 2.80 – 3.27 × 10−8) vs. 2.12 × 10−8 (95% C.I.: 1.96 – 2.29 × 10−8) mutations per position per generation, respectively) (Fig. 3a; Figs. S34, S36–S38; Table S38; Methods). The increased variation of P1, P2 and P3 likely results from sequence exchange between multicopy regions.

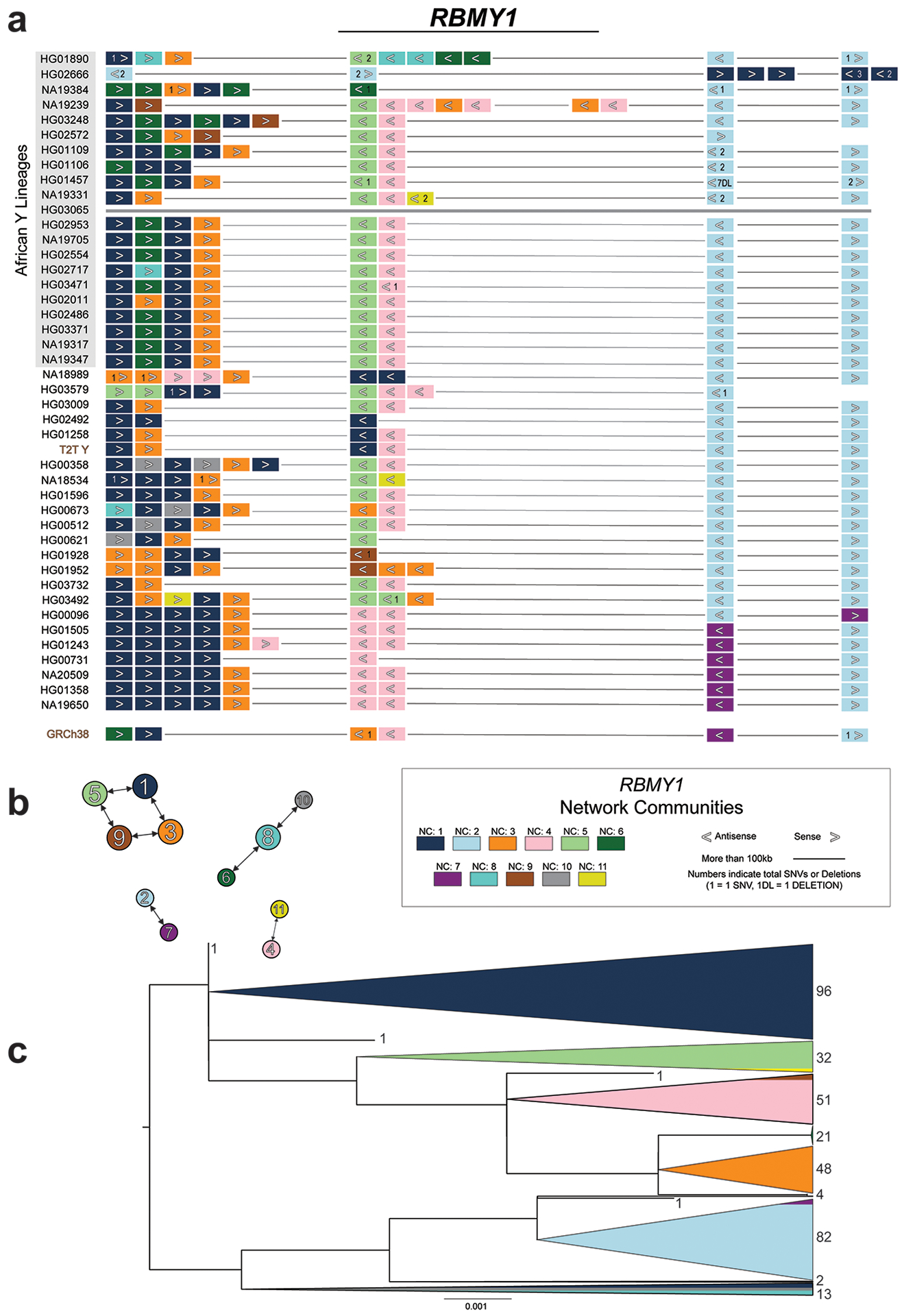

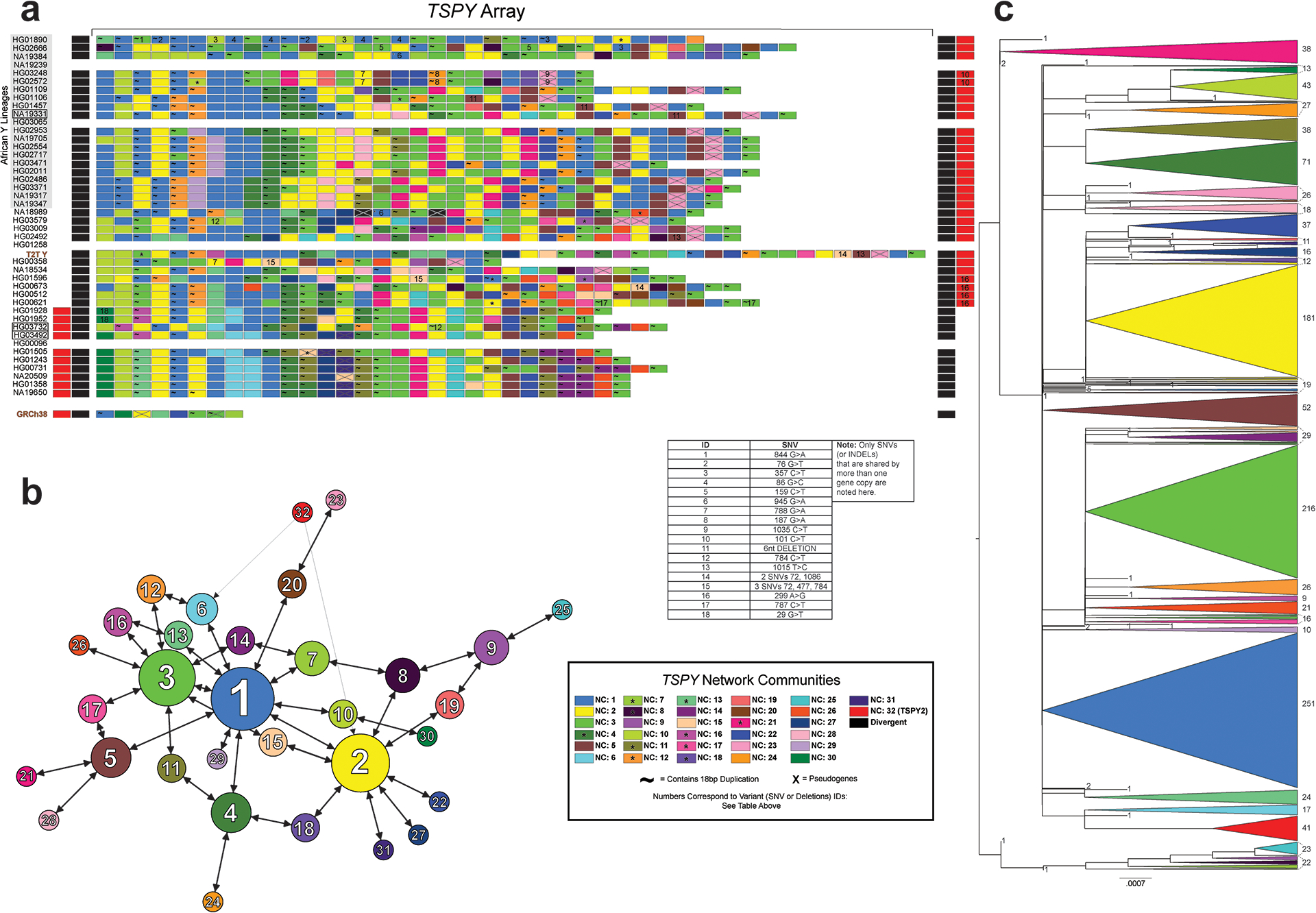

The gene annotation of the Y-chromosomal assemblies showed no evidence of the loss of any MSY protein-coding genes in the 43 males analysed (Tables S39–S43; Supplementary Results ‘Gene annotation’). However, the investigation of three copy-number variable ampliconic gene families (DAZ (Deleted in Azoospermia), TSPY (testis specific protein Y-linked 1), RBMY1 (RNA-binding motif (RRM) gene on Y chromosome), Supplementary Results ‘Gene family architecture and evolution’) revealed substantial differences in their genetic diversity and evolution. While only two out of 43 samples (41 assemblies, T2T Y and GRCh38 Y) showed a difference in the DAZ copy number (two and six DAZ copies vs. four in all others), extensive variation was detected in the copy number of the 28 canonical exons (from 0 to 14 copies of a single exon) between samples (Fig. S39; Tables S15, S44–S45, Methods). Consistent with previous reports, RBMY1 genes were primarily located in four separate regions, while three samples had undergone larger rearrangements (Extended Data Fig. 4; Fig. S40; Supplementary Results ‘Gene family architecture and evolution’)24. On average, eight RBMY1 gene copies (from 5 to 11) were identified, with most of the variation caused by expansions or contractions in regions 1 and 2 (Extended Data Fig. 4; Table S39). A phylogenetic analysis of RBMY1 genes revealed that the gene copies from regions 3 and 4 have likely given rise to RBMY1 genes located in regions 1 and 2 (Extended Data Figs. 4; Figs. S40–S41), additionally supported by the analysis of the chimpanzee (PanTro6) RBMY1 sequences (Supplementary Results ‘Gene family architecture and evolution’).

The majority of the TSPY genes are located in a tandemly organized and highly copy-number variable TSPY array. While a single repeat unit containing the TSPY2 gene is located upstream of the TSPY array in GRCh38, we inferred that the ancestral position of TSPY2 lies in between the TSPY repeat array and the Y centromere in reverse orientation (Fig. 3c; Extended Data Fig. 5; Fig. S42; Table S36; Supplementary Results sections ‘Y-chromosomal inversions’ and ‘Gene family evolution’). Likely the result of two inversions or a complex rearrangement, the localization of TSPY2 upstream of the TSPY array is shared by all QR haplogroup (including the GRCh38 Y) individuals. On average, 33 TSPY gene copies (from 23 to 39, 46 in T2T Y, counts only include low divergence (≤2%) TSPY gene copies from the TSPY repeat array and TSPY2) were identified per assembly (Fig. 3c; Extended Data Fig. 5; Fig. S43; Tables S15, S40). Both network and phylogenetic analysis of TSPY gene sequences support identification of the ancestral gene copy (medium blue in Extended Data Fig. 5b–c; Methods). Notably, five independently arisen pseudogenes were identified among the TSPY genes located within the 41 TSPY arrays analysed (39 contiguous assemblies, the T2T Y and the GRCh38 Y), with 31/41 samples carrying at least one pseudogene (Fig. 3c). The phylogenetic distribution suggests periodic purging of pseudogenes from the array, possibly through the removal of deleterious mutations by gene conversion and NAHR. Evidence of gene conversions and NAHR was found both between the tandemly repeated TSPY gene copies and the RBMY1 genes (Extended Data Figs. 4–5).

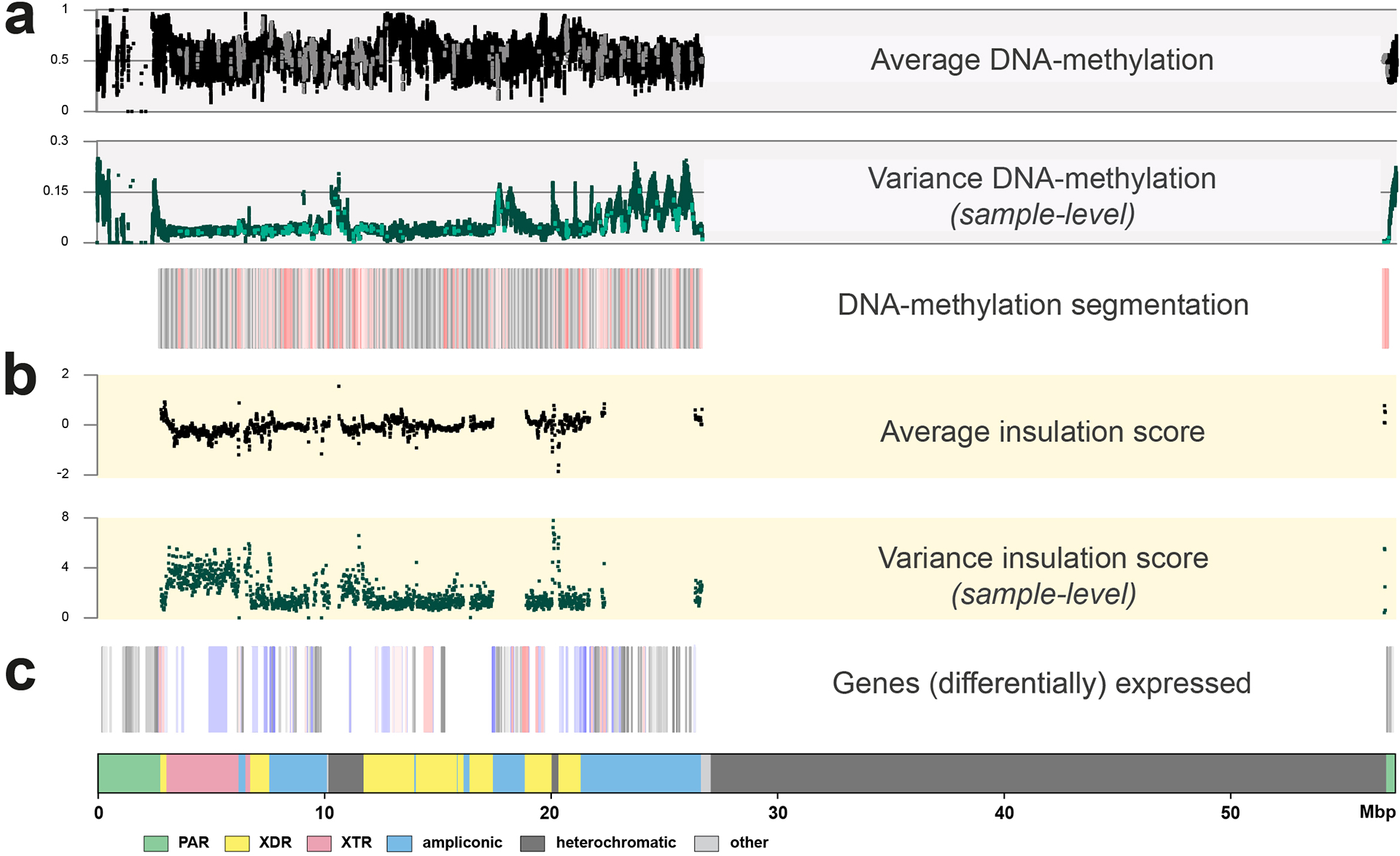

Epigenetic variation.

The ONT sequencing data also provide a means to explore the base-level epigenetic landscape of the Y chromosomes (Extended Data Fig. 6). Here, we focused on DNA methylation at CpG sites, hereafter referred to as DNAme. In 41 samples (EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines) that passed QC (Methods), we first tested the association of chromosome Y assembly length on global DNAme levels as has previously been shown in Drosophila25. We detected a significant relationship between the chromosome Y assembly length on global DNAme levels, both genome wide and for the Y chromosome (linear model p=0.0477 and p=0.0469 (n=41); Fig. S44; Supplementary Results ‘Functional analysis’). We found 2,861 DNAme segments that vary across these Y chromosomes (Extended Data Fig. 7; Table S46). Of note, 21% of the variation in DNAme levels is associated with haplogroups (Permanova p=0.003, n=41), while the same is true for only 4.8% of the expression levels (Permanova p=0.005, n=210, leveraging the Geuvadis RNA-seq expression data26; Methods). This association is particularly strong for five genes (BCORP1 (Fig. S45), LINC00280, LOC100996911, PRKY, UTY), where both DNAme and gene-expression effects are observed (Tables S46–47). Lastly, we find 194 Y-chromosomal genetic variants, including a 171 base-pair insertion and one inversion, that impact DNAme levels on chromosome Y (Table S48; Supplementary Results ‘Functional analysis’). This suggests that some of the genetic background, either on the Y chromosome or elsewhere in the genome, may impact the functional outcome (the epigenetic and transcriptional profiles) of specific genes on the Y chromosome.

Variation of the heterochromatic regions

Variation in the size and structure of centromeric/pericentromeric repeat arrays.

In general, the chromosome Y centromeres are composed of 171 bp DYZ3 α-satellite repeat units1, organized into a higher-order repeat (HOR) array, flanked on either side by short stretches of monomeric α-satellite. The α-satellite HOR arrays across gaplessly assembled Y centromeres ranged in size from 264 kbp to 1.165 Mbp (mean 671 kbp), with smaller arrays found in haplogroup R1b samples compared to other lineages (mean 341 kbp vs. 787 kbp, respectively; Extended Data Fig. 8a; Figs. S18, S23–S24; Tables S15–16; Methods)27,28. We determined that the DYZ3 α-satellite HOR array is mostly composed of a 34-monomer repeating unit that is the most prevalent HOR type found in the 21 analysed samples (Fig. 4b; Fig. S46; Methods). However, we identified two other HORs that were present at high frequency among the analysed Y chromosomes: a 35-monomer HOR found in 14/21 samples and a 36-monomer HOR found in 11/21 samples (Methods). While the 35-monomer HOR is present across different Y lineages in the Y phylogeny, the 36-monomer HOR has been lost in phylogenetically closely related Y chromosomes representing the QR haplogroups (Extended Data Fig. 8a). Analysis of the sequence composition of these HORs revealed that the 36-monomer HOR likely represents the ancestral state of the canonical 35-mer and 34-mer HOR after deletion of the 22nd α-satellite monomer in the resulting HORs, respectively (Fig. S46; Methods).

The overall organization of the DYZ3 α-satellite HOR array is similar to that found on other human chromosomes, with near-identical α-satellite HORs in the core of the centromere that become increasingly divergent towards the periphery29–32. There is a directionality of the divergent monomers at the periphery of the Y centromeres such that a larger block of diverged monomers is consistently found at the p-arm side of the centromere compared to the block of diverged monomers juxtaposed to the q-arm (Fig. 4b; Extended Data Fig. 8b; Figs. S47–S48).

Adjacent to the DYZ3 α-satellite HOR array on the q-arm is an HSat3 repeat array, which ranges in size from 372 to 488 kbp (mean 378 kbp), followed by a DYZ17 repeat array, which ranges in size from 858 kbp to 1.740 Mbp (mean 1.085 Mbp). Comparison of the sizes of these three repeat arrays reveals no significant correlation among their sizes (Figs. S47–S49; Tables S15–S16).

The DYZ19 repeat array is located on the long arm, flanked by XDRs (Fig. 1a) and composed of 125 bp repeat units (fragment of an LTR) in head-to-tail fashion. This subregion was completely assembled across all 43 Y chromosomes and among subregions exhibits the highest variation with a 6.7-fold difference in size (from 63.5 to 428 kbp). The HG02492 individual (haplogroup J2a) with the smallest-sized DYZ19 repeat array has an approximately 200 kbp deletion in this subregion (Table S16). In 43/44 Y chromosomes (including T2T Y), we find evidence of at least two rounds of mutation/expansion (Fig. 4a, green and red coloured blocks, respectively; Figs. S19–S21), leading to directional homogenization of the central and distal parts of the region in all Y chromosomes. Finally, we observed a recent ~80 kbp duplication event shared by the 11 phylogenetically related haplogroup QR samples (Figs. S19–S21), which must have occurred approximately 36,000 years ago (Figs. 1b, S1), resulting in a substantially larger overall DYZ19 subregion in these Y chromosomes.

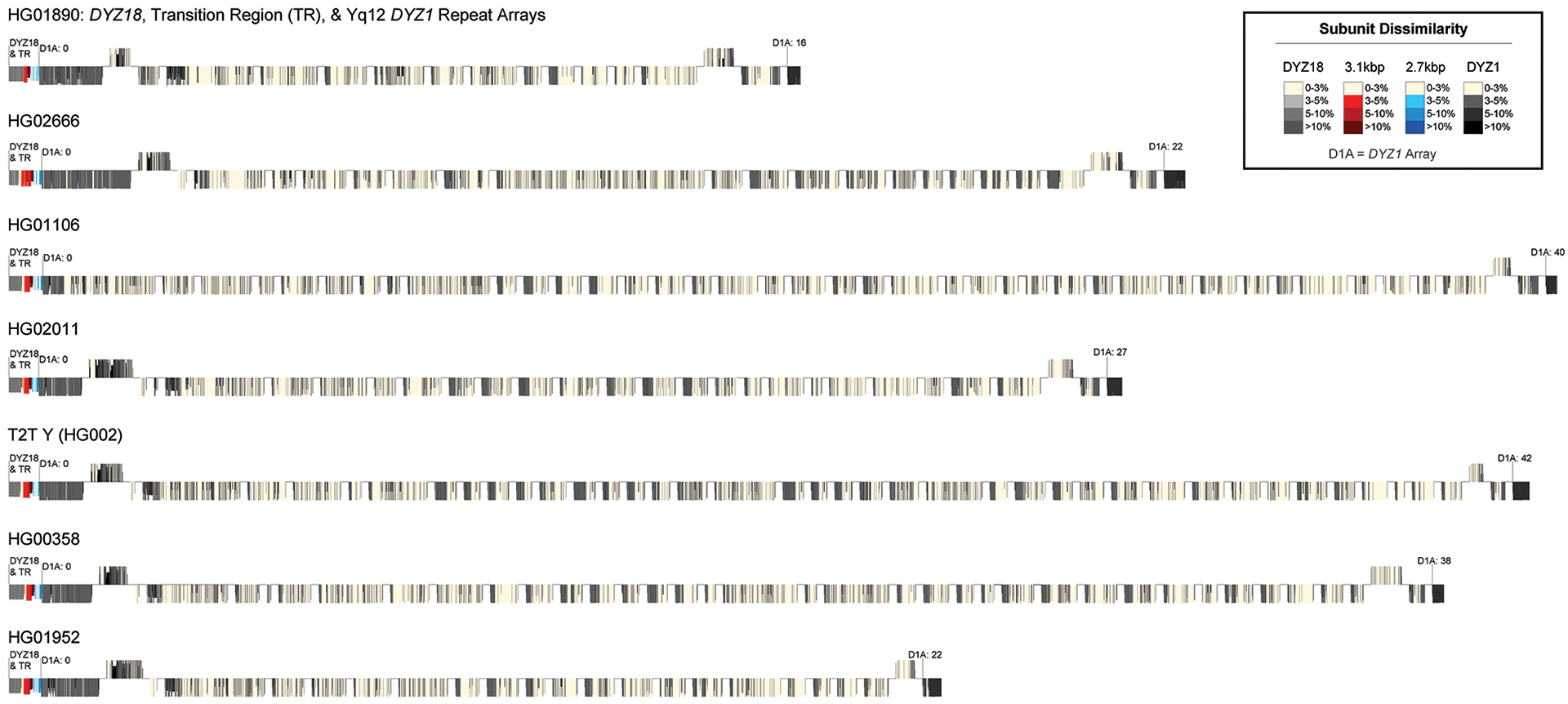

Between the Yq11 and the Yq12 subregions lies the DYZ18 subregion, which comprises three distinct repeat arrays: a DYZ18 repeat array and novel 3.1 kbp and 2.7 kbp repeat arrays (Extended Data Fig. 9; Figs. S50–S56). The 3.1 kbp repeat array is composed of degenerate copies of the DYZ18 repeat unit, exhibiting 95.8% sequence identity (using SNVs only) across the length of the repeat unit. The 2.7 kbp repeat array seems to have originated from both the DYZ18 (23% of the 2.7 kbp repeat unit shows 86.3% sequence identity to DYZ18) and DYZ1 (77% of the 2.7 kbp repeat unit shows 97% sequence identity to DYZ1) repeat units (Fig. S50). All three repeat arrays (DYZ18, 3.1 kbp and 2.7 kbp) show a similar pattern and level of methylation compared to the DYZ1 repeat arrays (Fig. S57), in that we observe constitutive hypermethylation.

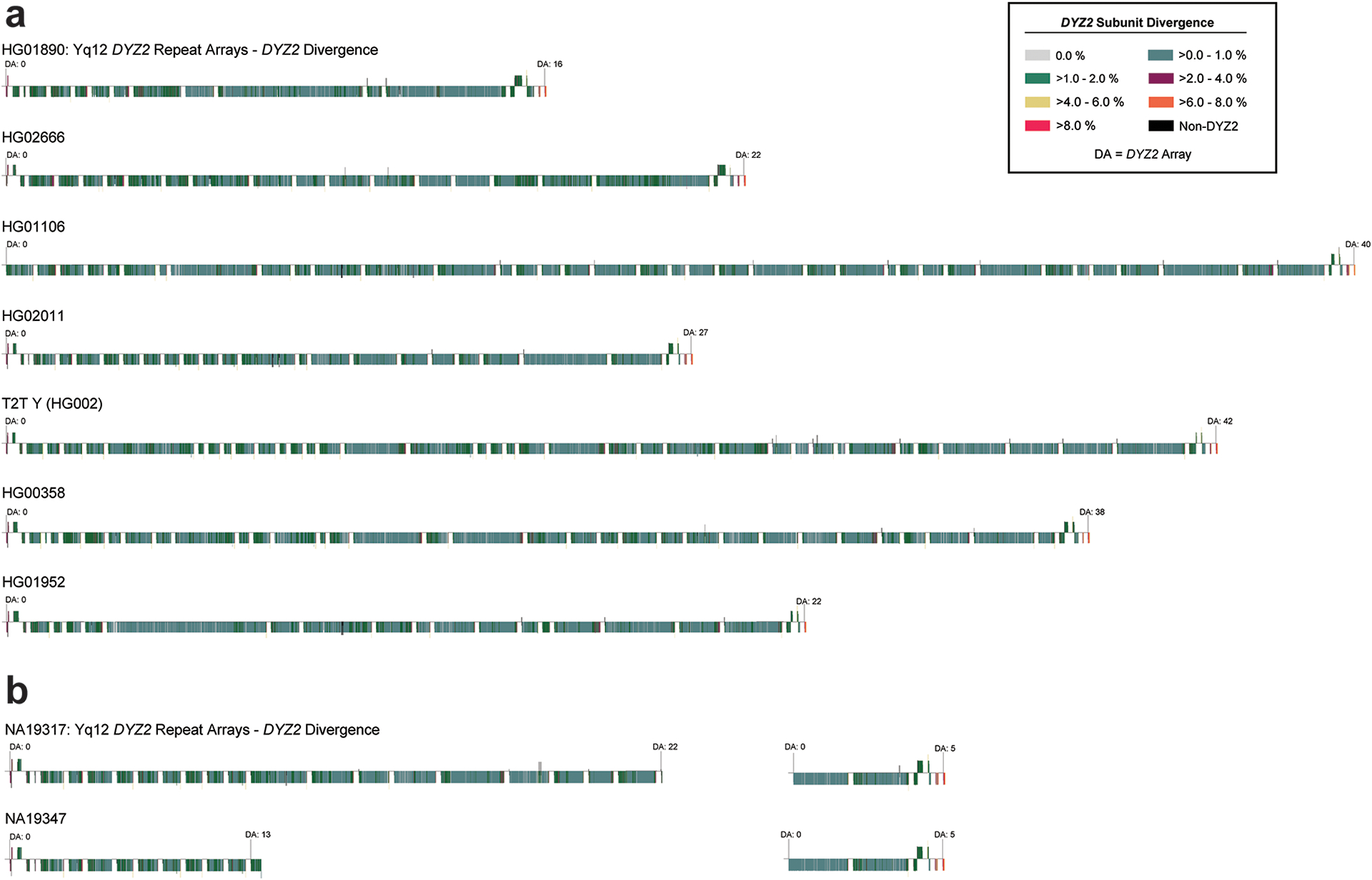

Composition of the Yq12 heterochromatic subregion.

The Yq12 subregion is the most challenging portion of the Y chromosome to assemble contiguously due to its highly repetitive nature and size. In this study, we completely assembled the Yq12 subregion for six individuals and compared it to the Yq12 subregion of the T2T Y chromosome (Figs. 1a, 5a,f; Tables S14–S16; Supplementary Results ‘Yq12 heterochromatic subregion‘). This subregion is composed of alternating arrays of repeat units: DYZ1 and DYZ21,6,33–36. The DYZ1 repeat unit is approximately 3.5 kbp and consists mainly of simple repeats and pentameric satellite sequences, and has been recently referred to as HSat3A65. The DYZ2 repeat (which has been recently referred to as HSat1B31) is approximately 2.4 kbp and consists mainly of a tandemly repeated AT-rich simple repeat fused to a 5’ truncated Alu element followed by an HSATI satellite sequence (Fig. S50).

The DYZ1 repeat units are tandemly arranged into larger DYZ1 repeat arrays, as are the DYZ2 repeat units, and the DYZ1 and DYZ2 repeat arrays alternate with one another (Fig. 5). The total number of DYZ1 and DYZ2 arrays (range from 34 to 86, mean 61) were significantly positively correlated (Spearman correlation=0.90, p-value=0.0056, n=7, alpha=0.05) with the total length of the analysed Yq12 region (Fig. S58), whereas the length of the individual DYZ1 and DYZ2 repeat arrays were found to be widely variable (Fig. 5b; Fig. S59). The DYZ1 arrays were significantly longer (range from 50,420 to 3,599,754 bp, mean 535,314 bp) than the DYZ2 arrays (range from 11,215 to 2,202,896 bp, mean 354,027 bp, two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, p-value < 0.05 for all seven assemblies with a complete Yq12 region); however, the total number of each repeat unit was nearly equal within each Y chromosome (DYZ1 to DYZ2 ratio ranges from 0.88 to 1.33, mean 1.09) (Fig. 5b; Table S49). From ONT data, we observed a consistent hypermethylation of the DYZ2 repeat arrays compared to the DYZ1 repeat arrays, the sequence composition of the two repeats is markedly different in terms of CG content (24% DYZ2 versus 38% DYZ1) and number of CpG dinucleotides (1 CpG/150 bp DYZ2 versus 1 CpG/35 bp DYZ1) potentially explaining the marked DNA methylation differences (Extended Data Fig. 6).

Sequence analysis of the repeat units in the Yq12 suggests that the DYZ1 and DYZ2 repeat arrays and the entire Yq12 subregion may have evolved in a similar manner, and similarly to the centromeric region (see above). Specifically, repeat units near the middle of a given array showed a higher level of sequence similarity to each other than to the repeat units at the distal regions of the repeat array (Fig. 5d; Extended data Figs. 9–10). This suggests that expansion and contraction tend to occur in the middle of the repeat arrays, homogenizing these units yet allowing divergent repeat units to accumulate towards the periphery. Similarly, when looking at the entire Yq12 subregion, we observed that repeat arrays located in the middle of the Yq12 subregion tend to be more similar in sequence to each other than to repeat arrays at the periphery (Fig. 5e; Extended Data Figs. 9–10; Figs. S60). This observation is supported by results from the DYZ2 repeat divergence analysis, the inter-DYZ2 array profile comparison, and the construction of a DYZ2 phylogeny (Fig. S61; Methods).

Discussion

The mammalian Y chromosome has been notoriously difficult to assemble owing to its extraordinarily high repeat content. Here, we present the Y-chromosomal assemblies of 43 males from the 1000 Genomes Project dataset and a comprehensive analysis of their genetic and epigenetic variation and composition. While both the GRCh38 Y and the T2T Y assemblies represent relatively recently emerged (TMRCA 54.5 kya [95% HPD interval: 47.6 – 62.4 kya], Fig. S1) European Y lineages, half of our Y chromosomes carry African Y lineages, including two of the deepest-rooted human Y lineages (A0b and A1a, TMRCA 183 kya [95% HPD interval: 160–209 kya]), which we gaplessly assembled allowing us to investigate how the Y chromosome has changed over 180,000 years of human evolution.

For the first time, we were able to comprehensively and precisely examine the extent of genetic variation down to the nucleotide level across multiple human Y chromosomes. The male-specific portion of the Y chromosome (MSY) can be roughly divided into two portions: the euchromatic and the heterochromatic regions. The single-copy protein-coding MSY genes, present in the GRCh38 Y reference sequence, are conserved in all 43 Y assemblies with few SNVs. The low SNV diversity in Y is concordant with previous studies and consistent with models of natural demographic processes such as extreme male-specific bottlenecks in recent human history and purifying selection removing deleterious mutations and linked variation12,14,37. The multi-copy protein-coding MSY genes are often copy number variable. We found that 5/8 multi-copy gene families showed variation in terms of copy number, with the highest variation observed in the TSPY gene family (23 to 39 copies, 46 in the T2T Y, Fig. 3c; Table S40). Investigation of three copy-number variable gene families (TSPY, RBMY1 and DAZ) revealed different modes of evolution, likely resulting from differences in structural composition of the genomic regions. For example, the majority of the TSPY genes are located within a tandemly repeated array, undergoing frequent expansions and contractions, where we also find evidence of lineage-specific acquisition and purging of pseudogenes.

The euchromatic region harbours additional structural variation across the 43 individuals. Most notably, we identified 14 inversions that together affect half of the Y-chromosomal euchromatin, with only the most closely related pair of African Ys (from NA19317 and NA19347) showing the exact same inversion composition. Of these 14 inversions, 12 showed recurrent toggling in recent human history, including five novel recurrent inversions that were not previously reported2. We narrowed down the breakpoints for all of the inversions and have refined the breakpoints down to a 500 bp region for 8 of 14 inversions. The determination of the molecular mechanism causing the inversions remains challenging; however, the increased recurrent inversion rate on the Y chromosome compared to the rest of the human genome may be in part due to DNA double-strand breaks being repaired by intra-chromatid recombination2,38. The enrichment in highly similar (inverted) SDs1,4 prone to NAHR, coupled with reduced selection to maintain gene order, may explain the high prevalence of recurrent inversions on the Y. The majority of the recurrent inversions (8/14) occur between highly similar SDs termed palindromes P1-P8 (Fig. 3a). Three of the palindromes appear to be evolving at faster rates compared both to the other five palindromes and the unique XDR regions of the Y, likely due to sequence exchange between multi-copy (i.e., >2 copies) SDs.

In the PAR1 region, we find evidence of enrichment of indels and SVs compared to autosomes, and the rest of the X and the Y chromosomes, potentially resulting from a higher recombination rate in this region during male meiosis22. Interestingly, there is a reduction of genetic variation in the proximal 500 kbp of PAR1, indicating a reduced recombination rate here and suggesting that the actual PAR1 boundary probably lies distal to the currently established boundary1.

There are four heterochromatic subregions in the human Y chromosome: the (peri-)centromeric region, DYZ18, DYZ19 and Yq12. Heterochromatin is usually defined by the preponderance of highly repetitive sequences and the constitutive dense packaging of the chromatin within39. When we examined the DNA sequence and the methylation patterns for these four heterochromatic subregions, the high repetitive sequence content and the high level of methylation (Extended Data Fig. 6; Figs. S57) observed is consistent with the definition of heterochromatin. Furthermore, resolving the complete structural variation in the heterochromatic regions of the human Y chromosome provides novel molecular archaeological evidence for evolutionary mechanisms. For example, we show how the higher order structure at the centromeric region of the Y chromosome evolved from an ancestral 36-mer HOR to a 34-mer HOR, which predominates in the centromeres of human males40. Moreover, the degeneration of these repeat units of the (peri-)centromeric region of the Y chromosome has a directional bias towards the p-arm side. The presence of an Alu element right at the q-arm boundary, but not on the p-arm side, raises the possibility that following two Alu insertions, over 180,000 years ago, led to a subsequent Alu-Alu recombination that deleted the region in between and removed the diverged centromeric sequence block41. In the Yq12 subregion, we find evidence for localized expansions and contractions of the DYZ1 and DYZ2 repeat units, though the preservation of nearly 1:1 ratio among all males studied indicates functional or evolutionary constraints.

In this study, we fully sequenced and analysed 43 diverse Y chromosomes and identified the full extent of variation of this chromosome across more than 180,000 years of human evolution, offering a major advance to our understanding of how non-recombining regions of the genome evolve and persist. For the first time, sequence-level resolution across multiple human Y chromosomes has revealed new DNA sequences and new elements of conservation, and provided molecular data that give us important insights into genomic stability and chromosomal integrity. It also offers the possibility to investigate the molecular mechanisms and evolution of repetitive sequences across a well-defined timeframe without the encumbrances of meiotic recombination. Ultimately, the ability to effectively assemble the complete human Y chromosome has been a long-awaited yet crucial milestone towards understanding the full extent of human genetic variation and also provides the starting point to associate Y-chromosomal sequences to specific human traits and more thoroughly study human evolution.

Methods

1. Sample selection

Samples were selected from the 1000 Genomes Project Diversity Panel44 and at least one representative was selected from each of 26 populations (Table S1). A total of 13/28 samples were included from the Human Genome Structural Variation Consortium (HGSVC) Phase 2 dataset, which was published previously20. In addition, for 15/28 samples data was newly generated as part of the HGSVC efforts (see the section ‘Data production’ for details’). We also included 15 samples from the Human Pangenome Reference Consortium (HPRC) (Table S1). Notably, there is an African Y lineage (A00) older than the lineages in our dataset (TMRCA 254 kya; 95% CI 192–307 kya14,45) that we could not include due to sample availability issues.

2. Data production

Data generated as part of this project was derived from lymphoblast lines available from the Coriell Institute for Medical Research for research purposes (https://www.coriell.org/), and authenticated using Illumina high-coverage data from50. Regular checks for mycoplasma contamination are performed at the Coriell Institute who maintains the cell lines.

a. PacBio HiFi sequence production

University of Washington -

Sample HG00731 data have been previously described20. Additional samples HG02554 and HG02953 were prepared for sequencing in the same way but with the following modifications: isolated DNA was sheared using the Megaruptor 3 instrument (Diagenode) twice using settings 31 and 32 to achieve a peak size of ~15–20 kbp. The sheared material was subjected to SMRTbell library preparation using the Express Template Prep Kit v2 and SMRTbell Cleanup Kit v2 (PacBio). After checking for size and quantity, the libraries were size-selected on the Pippin HT instrument (Sage Science) using the protocol “0.75% Agarose, 15–20 kbp High Pass” and a cutoff of 14–15 kbp. Size-selected libraries were checked via fluorometric quantitation (Qubit) and pulse-field sizing (FEMTO Pulse). All cells were sequenced on a Sequel II instrument (PacBio) using 30-hour movie times using version 2.0 sequencing chemistry and 2-hour pre-extension. HiFi/CCS analysis was performed using SMRT Link v10.1 using an estimated read-quality value of 0.99.

The Jackson Laboratory -

High-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA was extracted from 30M frozen pelleted cells using the Gentra Puregene extraction kit (Qiagen). Purified gDNA was assessed using fluorometric (Qubit, Thermo Fisher) assays for quantity and FEMTO Pulse (Agilent) for quality. For HiFi sequencing, samples exhibiting a mode size above 50 kbp were considered good candidates. Libraries were prepared using SMRTBell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 (Pacbio). Briefly, 12 μl of DNA was first sheared using gTUBEs (Covaris) to target 15–18 kbp fragments. Two 5 μg of sheared DNA were used for each prep. DNA was treated to remove single strand overhangs, followed by DNA damage repair and end repair/ A-tailing. The DNA was then ligated V3 adapter and purified using Ampure beads. The adapter ligated library was treated with Enzyme mix 2.0 for Nuclease treatment to remove damaged or non-intact SMRTbell templates, followed by size selection using Pippin HT generating a library that has a size >10 kbp. The size selected and purified >10 kbp fraction of libraries were used for sequencing on Sequel II (Pacbio).

b. ONT-UL sequence production

University of Washington -

High-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA was extracted from 2 aliquots of 30 M frozen pelleted cells using phenol-chloroform approach as described in46. Libraries were prepared using Ultra long DNA Sequencing Kit (SQK-ULK001, ONT) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Briefly, DNA from ~10M cells was incubated with 6 μl of fragmentation mix (FRA) at room temperature (RT) for 5 min and 75°C for 5 min. This was followed by an addition of 5 μl of adaptor (RAP-F) to the reaction mix and incubated for 30 min at RT. The libraries were cleaned up using Nanobind disks (Circulomics) and Long Fragment Buffer (LFB) (SQK-ULK001, ONT) and eluted in Elution Buffer (EB). Libraries were sequenced on the flow cell R9.4.1 (FLO-PRO002, ONT) on a PromethION (ONT) for 96 hrs. A library was split into 3 loads, with each load going 24 hrs followed by a nuclease wash (EXP-WSH004, ONT) and subsequent reload.

The Jackson Laboratory -

High-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA was extracted from 60 M frozen pelleted cells using phenol-chloroform approach as previously described47. Libraries were prepared using Ultra long DNA Sequencing Kit (SQK-ULK001, ONT) according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Briefly, 50ug of DNA was incubated with 6 μl of FRA at RT for 5 min and 75°C for 5 min. This was followed by an addition of 5 μl of adaptor (RAP-F) to the reaction mix and incubated for 30 min at RT. The libraries were cleaned up using Nanodisks (Circulomics) and eluted in EB. Libraries were sequenced on the flow cell R9.4.1 (FLO-PRO002, ONT) on a PromethION (ONT) for 96 hrs. A library was generally split into 3 loads with each loaded at an interval of about 24 hrs or when pore activity dropped to 20%. A nuclease wash was performed using Flow Cell Wash Kit (EXP-WSH004) between each subsequent load.

c. Bionano Genomics optical genome maps production

Optical mapping data were generated at Bionano Genomics, San Diego, USA. Lymphoblastoid cell lines were obtained from Coriell Cell Repositories and grown in RPMI 1640 media with 15% FBS, supplemented with L-glutamine and penicillin/streptomycin, at 37°C and 5% CO2. Ultra-high-molecular-weight DNA was extracted according to the Bionano Prep Cell Culture DNA Isolation Protocol (Document number 30026, revision F) using a Bionano SP Blood & Cell DNA Isolation Kit (Part #80030). In short, 1.5 M cells were centrifuged and resuspended in a solution containing detergents, proteinase K, and RNase A. DNA was bound to a silica disk, washed, eluted, and homogenized via 1hr end-over-end rotation at 15 rpm, followed by an overnight rest at RT. Isolated DNA was fluorescently tagged at motif CTTAAG by the enzyme DLE-1 and counter-stained using a Bionano Prep™ DNA Labeling Kit – DLS (catalog # 8005) according to the Bionano Prep Direct Label and Stain (DLS) Protocol(Document number 30206, revision G). Data collection was performed using Saphyr 2nd generation instruments (Part #60325) and Instrument Control Software (ICS) version 4.9.19316.1.

d. Strand-seq data generation and data processing

Strand-seq data were generated at EMBL and the protocol is as follows. EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines from the 1000 Genomes Project (Coriell Institute; Table S1) were cultured in BrdU (100 uM final concentration; Sigma, B9285) for 18 or 24 hrs, and single isolated nuclei (0.1% NP-40 substitute lysis buffer48 were sorted into 96-well plates using the BD FACSMelody and BD Fusion cell sorter. In each sorted plate, 94 single cells plus one 100-cell positive control and one 0-cell negative control were deposited. Strand-specific single-cell DNA sequencing libraries were generated using the previously described Strand-seq protocol23,48 and automated on the Beckman Coulter Biomek FX P liquid handling robotic system49. Following 15 rounds of PCR amplification, 288 individually barcoded libraries (amounting to three 96-well plates) were pooled for sequencing on the Illumina NextSeq500 platform (MID-mode, 75 bp paired-end protocol). The demultiplexed FASTQ files were aligned to the GRCh38 reference assembly (GCA_000001405.15) using BWA aligner (version 0.7.15–0.7.17) for standard library selection. Aligned reads were sorted by genomic position using SAMtools (version 1.10) and duplicate reads were marked using sambamba (version 1.0). Low-quality libraries were excluded from future analyses if they showed low read counts (<50 reads per Mbp), uneven coverage, or an excess of ‘background reads’ (reads mapped in opposing orientation for chromosomes expected to inherit only Crick or Watson strands) yielding noisy single-cell data, as previously described48. Aligned BAM files were used for inversion discovery as described in2.

e. Hi-C data production

Lymphoblastoid cell lines were obtained from Coriell Cell Repositories and cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 15% FBS. Cells were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Hi-C libraries using 1.5 M human cells as input were generated with Proximo Hi-C kits v4.0 (Phase Genomics, Seattle, WA) following the manufacturer’s protocol with the following modification: in brief, cells were crosslinked, quenched, lysed sequentially with Lysis Buffers 1 and 2, and liberated chromatin immobilized on magnetic recovery beads. A 4-enzyme cocktail composed of DpnII (GATC), DdeI (CTNAG), HinfI (GANTC), and MseI (TTAA) was used during the fragmentation step to improve coverage and aid haplotype phasing. Following fragmentation and fill-in with biotinylated nucleotides, fragmented chromatin was proximity ligated for 4 hrs at 25°C. Crosslinks were then reversed, DNA purified and biotinylated junctions recovered using magnetic streptavidin beads. Bead-bound proximity ligated fragments were then used to generate a dual-unique indexed library compatible with Illumina sequencing chemistry. The Hi-C libraries were evaluated using fluorescent-based assays, including qPCR with the Universal KAPA Library Quantification Kit and Tapestation (Agilent). Sequencing of the libraries was performed at New York Genome Center (NYGC) on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 instrument using 2×150 bp cycles.

f. RNAseq data production

Total RNA of cell pellets were isolated using QIAGEN RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, each cell pellet (10 M cells) was homogenized and lysed in Buffer RLT Plus, supplemented with 1% β-mercaptoethanol. The lysate-containing RNA was purified using an RNeasy spin column, followed by an in-column DNase I treatment by incubating for 10 min at RT, and then washed. Finally, total RNA was eluted in 50 uL RNase-free water. RNA-seq libraries were prepared with 300 ng total RNA using KAPA RNA Hyperprep with RiboErase (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First, ribosomal RNA was depleted using RiboErase. Purified RNA was then fragmented at 85°C for 6 min, targeting fragments ranging 250–300 bp. Fragmented RNA was reverse transcribed with an incubation of 25°C for 10 min, 42°C for 15 min, and an inactivation step at 70°C for 15 min. This was followed by a second strand synthesis and A-tailing at 16°C for 30 min, 62°C for 10 min. The double-stranded cDNA A-tailed fragments were ligated with Illumina unique dual index adapters. Adapter-ligated cDNA fragments were then purified by washing with AMPure XP beads (Beckman). This was followed by 10 cycles of PCR amplification. The final library was cleaned up using AMPure XP beads. Quantification of libraries was performed using real-time qPCR (Thermo Fisher). Sequencing was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq platform generating paired end reads of 100 bp at The Jackson Laboratory for Genomic Medicine.

g. Iso-seq data production

Iso-seq data were generated at The Jackson Laboratory. Total RNA was extracted from 10 M human cell pellets. 300 ng total RNA were used to prepare Iso-seq libraries according to Iso-seq Express Template Preparation (Pacbio). First, full-length cDNA was generated using NEBNext Single Cell/ Low Input cDNA synthesis and Amplification Module in combination with Iso-seq Express Oligo Kit. Amplified cDNA was purified using ProNex beads. The cDNA yield of 160–320 ng then underwent SMRTbell library preparation including a DNA damage repair, end repair, and A-tailing and finally ligated with Overhang Barcoded Adapters. Libraries were sequenced on Pacbio Sequel II. Iso-seq reads were processed with default parameters using the PacBio Iso-seq3 pipeline.

3. Construction and dating of Y phylogeny

The genotypes were jointly called from the 1000 Genomes Project Illumina high-coverage data from50 using the ~10.4 Mbp of chromosome Y sequence previously defined as accessible to short-read sequencing51. BCFtools (v1.9)52,53 was used with minimum base quality and mapping quality 20, defining ploidy as 1, followed by filtering out SNVs within 5 bp of an indel call (SnpGap) and removal of indels. Additionally, we filtered for a minimum read depth of 3. If multiple alleles were supported by reads, then the fraction of reads supporting the called allele should be ≥0.85; otherwise, the genotype was converted to missing data. Sites with ≥6% of missing calls, i.e., missing in more than 3 out of 44 samples, were removed using VCFtools (v0.1.16)54. After filtering, a total of 10,406,108 sites remained, including 12,880 variant sites. Since Illumina short-read data was not available from two samples, HG02486 and HG03471, data from their fathers (HG02484 and HG03469, respectively) was used for Y phylogeny construction and dating.

The Y haplogroups of each sample were predicted as previously described15 and correspond to the International Society of Genetic Genealogy nomenclature (ISOGG, https://isogg.org, v15.73, accessed in August 2021). We used the coalescence-based method implemented in BEAST (v1.10.4)55 to estimate the ages of internal nodes in the Y phylogeny. A starting maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree for BEAST was constructed with RAxML (v8.2.10)56 with the GTRGAMMA substitution model. Markov chain Monte Carlo samples were based on 200 million iterations, logging every 1000 iterations. The first 10% of iterations were discarded as burn-in. A constant-sized coalescent tree prior, the GTR substitution model, accounting for site heterogeneity (gamma) and a strict clock with a substitution rate of 0.76 × 10−9 (95% confidence interval: 0.67 × 10−9– 0.86 × 10−9) single-nucleotide mutations per bp per year was used57. A prior with a normal distribution based on the 95% confidence interval of the substitution rate was applied. A summary tree was produced using TreeAnnotator (v1.10.4) and visualized using the FigTree software (v1.4.4).

The closely related pair of African E1b1a1a1a-CTS8030 lineage Y chromosomes carried by NA19317 and NA19347 differ by 3 SNVs across the 10,406,108 bp region, with the TMRCA estimated to 200 ya (95% HPD interval: 0 – 500 ya).

A separate phylogeny (see Fig. 5f) was reconstructed using seven samples (HG01890, HG02666, HG01106, HG02011, T2T Y from NA24385/HG002, HG00358 and HG01952) with contiguously assembled Yq12 region following identical approach to that described above, with a single difference that sites with any missing genotypes were filtered out. The final callset used for phylogeny construction and split time estimates using Beast contained a total of 10,382,177 sites, including 5,918 variant sites.

4. De novo Assembly Generation

a. Reference assemblies

We used the GRCh38 (GCA_000001405.15) and the CHM13 (GCA_009914755.3) plus the T2T Y assembly from GenBank (CP086569.2) released in April 2022. We note that we did not use the unlocalised GRCh38 contig “chrY_KI270740v1_random” (37,240 bp, composed of 289 DYZ19 primary repeat units) in any of the analyses presented in this study.

b. Constructing de novo assemblies

All 28 HGSVC and 15 HPRC samples were processed with the same Snakemake58 v6.13.1 workflow (see “Code Availability” statement in main text) to first produce a de novo whole-genome assembly from which selected sequences were extracted in downstream steps of the workflow. The de novo whole-genome assembly was produced using Verkko v1.016 with default parameters, combining all available PacBio HiFi and ONT data per sample to create a whole-genome assembly:

verkko -d work_dir/ --hifi {hifi_reads} --nano {ont_reads}

The Verkko assembly process includes several steps that lower the base error rate in the resulting assembly. Sequence overlaps among the HiFi reads are leveraged to correct errors, which further increases the accuracy of the HiFi reads before they are used for the initial genome graph construction. The final output sequence is generated by combining the available sequence information to form a consensus. Therefore, the Verkko assembly process generates highly accurate assemblies16. However, there may be a very small number of SNV errors that escape this correction process (which could benefit from additional corrections using Illumina polishing), that may minimally impact downstream SNV-based analyses.

We note here that we had to manually modify the assembly FASTA file produced by Verkko for the sample NA19705 for the following reason: at the time of assembly production, the Verkko assembly for the sample NA19705 was affected by a minor bug in Verkko v1.0 resulting in an empty output sequence for contig “0000598”. The Verkko development team suggested removing the affected record, i.e., the FASTA header plus the subsequent blank line, because the underlying bug is unlikely to affect the overall quality of the assembly. We followed that advice and continued the analysis with the modified assembly FASTA file. Our discussion with the Verkko development team is publicly documented in the Verkko Github issue #66. The assembly FASTA file was adapted as follows:

egrep -v “(^$|unassigned\-0000598)” assembly.original.fasta > assembly.fasta

For the samples with at least 50X HiFi input coverage (termed high-coverage samples, Tables S1–S2), we generated alternative assemblies using hifiasm v0.16.1-r37559 for quality control purposes. Hifiasm was executed with default parameters using only HiFi reads as input, thus producing partially phased output assemblies “hap1” and “hap2” (cf. hifiasm documentation):

hifiasm -o {out_prefix} -t {threads} {hifi_reads}

The two hifiasm haplotype assemblies per sample are comparable to the Verkko assemblies in that they represent a diploid human genome without further identification of specific chromosomes, i.e., the assembled Y sequence contigs have to be identified in a subsequent process that we implemented as follows.

We employed a simple rule-based strategy to identify and extract assembled sequences for the two quasi-haploid chromosomes X and Y. The following rules were applied in the order stated here:

- Rule 1: the assembled sequence has primary alignments only to the target sequence of interest, i.e., to either chrY or chrX. The sequence alignments were produced with minimap2 v2.2460:

minimap2 -t {threads} -x asm20 -Y --secondary=yes -N 1 --cs -c --paf-no-hit - Rule 2: the assembled sequence has mixed primary alignments, i.e., not only to the target sequence of interest, but exhibits Y-specific sequence motif hits for any of the following motifs: DYZ1, DYZ18 and the secondary repeat unit of DYZ3 from1. The motif hits were identified with HMMER v3.3.2dev (commit hash #016cba0)61:

nhmmer --cpu {threads} --dna -o {output_txt} --tblout {output_table} -E 1.60E-150 {query_motif} {assembly} Rule 3: the assembled sequence has mixed primary alignments, i.e., not only to the target sequence of interest, but exhibits more than 300 hits for the Y-unspecific repeat unit DYZ2 (see Section ‘Yq12 DYZ2 Consensus and Divergence’ for details on DYZ2 repeat unit consensus generation). The threshold was determined by expert judgement after evaluating the number of motif hits on other reference chromosomes. The same HMMER call as for rule 2 was used with an E-value cutoff of 1.6e-15 and a score threshold of 1700.

Rule 4: the assembled sequence has no alignment to the chrY reference sequence, but exhibits Y-specific motif hits as for rule 2.

Rule 5: the assembled sequence has mixed primary alignments, but more than 90% of the assembled sequence (in bp) has a primary alignment to a single target sequence of interest; this rule was introduced to resolve ambiguous cases of primary alignments to both chrX and chrY.

After identification of all assembled chrY and chrX sequences, the respective records were extracted from the whole-genome assembly FASTA file and, if necessary, reverse-complemented to be in the same orientation as the T2T reference using custom code.

c. Assembly evaluation and validation

Error detection in de novo assemblies

Following established procedures16,20, we implemented three independent approaches to identify regions of putative misassemblies for all 43 samples. First, we used VerityMap (v2.1.1-alpha-dev #8d241f4)19 that generates and processes read-to-assembly alignments to flag regions in the assemblies that exhibit spurious signal, i.e., regions of putative assembly errors, but that may also indicate difficulties in the read alignment. Given the higher accuracy of HiFi reads, we executed VerityMap only with HiFi reads as input:

python repos/VerityMap/veritymap/main.py --no-reuse --reads {hifi_reads} -t {threads} -d hifi -l SAMPLE-ID -o {out_dir} {assembly_FASTA}

Second, we used DeepVariant (v1.3.0)62 and the PEPPER-Margin-DeepVariant pipeline (v0.8, DeepVariant v1.3.063) to identify heterozygous (HET) SNVs using both HiFi and ONT reads aligned to the de novo assemblies. Given the quasi-haploid nature of the chromosome Y assemblies, we counted all HET SNVs remaining after quality filtering (bcftools v1.15 “filter” QUAL>=10) as putative assembly errors:

/opt/deepvariant/bin/run_deepvariant --model_type=“PACBIO” --ref={assembly_FASTA} --num_shards={threads} --reads={HiFi-to-assembly_BAM} --sample_name=SAMPLE-ID --output_vcf={out_vcf} --output_gvcf={out_gvcf} --intermediate_results_dir=$TMPDIR

run_pepper_margin_deepvariant call_variant --bam {ONT-to-assembly_BAM} --fasta {assembly_FASTA} --output_dir {out_dir} --threads {threads} --ont_r9_guppy5_sup --sample_name SAMPLE-ID --output_prefix {out_prefix} --skip_final_phased_bam --gvcf

Third, we used the tool NucFreq (v0.1)21 to identify positions in the HiFi read-to-assembly alignments where the second most common base is supported by at least 10% of the alignments. BAM files were filtered with samtools using the flag 2308 (drop secondary and supplementary alignments) following the information in the NucFreq readme. Additionally, we only processed assembled contigs larger than 500 kbp to limit the effect of spurious alignments in short contigs. NucFreq was then executed with default parameters:

NucPlot.py --obed OUTPUT.bed --threads {threads} --bed ASSM-CONTIGS.bed HIFI.INPUT.bam OUTPUT.png

We note here that NucFreq could not successfully process the alignments for sample HG00512 due to an error in the graphics output. We thus omitted this sample from the following processing steps. Again, following the information in the NucFreq readme, we then created flagged regions if more than five positions were flagged in a 500 bp window, and subsequently merged overlapping windows (Table S12).

As a final processing step, we merged the VerityMap- and NucFreq-flagged regions (subsuming HET SNVs called by either DeepVariant or PEPPER) by tripling each region’s size (flanking region upstream and downstream) and then merging all overlapping regions with bedtools:

bedtools merge -c 4 -o collapse -i CONCAT-ALL-REGIONS.bed > OUT.MERGED.bed

The resulting clusters and all regions separately were post-processed with custom code to derive error estimates for the assemblies (see “Code Availability” statement in main text and “Data availability” for access to BED files listing all flagged regions/positions and merged clusters; Table S10).

Since the PAR1 subregion was contiguously assembled from only 10 samples (Table S14, S16), all highlighted regions as putative assembly errors by VerityMap were visually evaluated in the HiFi and ONT read alignments to the assembly using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV v2.14.1)64 (Table S11).

Assembly QV estimates were produced with yak v0.1 (github.com/lh3/yak) following the examples in its documentation (see readme in referenced repository). The QV estimation process requires an independent sequence data source to derive a (sample-specific) reference k-mer set to compare the k-mer content of the assembly. In our case, we used available short read data to create said reference k-mer set, which necessitated excluding the samples HG02486 and HG03471 because no short reads were available. For the chromosome Y-only QV estimation, we restricted the short reads to those with primary alignments to our Y assemblies or to the T2T Y, which we added during the alignment step to capture reads that would align to Y sequences missing from our assemblies.

Assembly gap detection

We used the recently introduced tool Rukki (packaged with Verkko v1.2)16 to derive estimates of potential gaps in our assemblies. After having identified chrY and chrX contigs as described above, we used this information to prepare annotation tables for Rukki to identify chrX/chrY paths in the assembly graph:

rukki trio -g {assembly_graph} -m {XY_contig_table} -p {out_paths} --final-assign {out_node_assignment} --try-fill-bubbles --min-gap-size 1 --default-gap-size 1000

The resulting set of paths including gap estimates was summarized using custom code (Table S6). See “Data availability” section for access to NucFreq plots generated for all samples.

Assembly evaluation using Bionano Genomics optical mapping data

To evaluate the accuracy of Verkko assemblies, all samples (n=43) were first de novo assembled using the raw optical mapping molecule files (bnx), followed by alignment of assembled contigs to the T2T whole genome reference genome assembly (CHM13 + T2T Y) using Bionano Solve (v3.5.1) pipelineCL.py.

python2.7 Solve3.5.1_01142020/Pipeline/1.0/pipelineCL.py -T 64 -U -j 64 -jp 64 -N 6 -f 0.25 -i 5 -w -c 3 \

-y \

-b ${ bnx} \

-l ${output_dir} \

-t Solve3.5.1_01142020/RefAligner/1.0/ \

-a Solve3.5.1_01142020/RefAligner/1.0/optArguments_haplotype_DLE1_saphyr_human.xml \

-r ${ref}

To improve the accuracy of optical mapping Y chromosomal assemblies, unaligned molecules, molecules that align to T2T chromosome Y and molecules that were used for assembling contigs but did not align to any chromosomes were extracted from the optical mapping de novo assembly results. These molecules were used for the following three approaches: 1) local de novo assembly using Verkko assemblies as the reference using pipelineCL.py, as described above; 2) alignment of the molecules to Verkko assemblies using refAligner (Bionano Solve (v3.5.1)); and 3) hybrid scaffolding using optical mapping de novo assembly consensus maps (cmaps) and Verkko assemblies by hybridScaffold.pl.

perl Solve3.5.1_01142020/HybridScaffold/12162019/hybridScaffold.pl \

-n ${fastafile} \

-b ${bionano_cmap} \

-c Solve3.5.1_01142020/HybridScaffold/12162019/hybridScaffold_DLE1_config.xml \

-r Solve3.5.1_01142020/RefAligner/1.0/RefAligner \

-o ${output_dir} \

-f -B 2 -N 2 -x -y \

-m ${bionano_bnx} \

-p Solve3.5.1_01142020/Pipeline/12162019/ \

-q Solve3.5.1_01142020/RefAligner/1.0/optArguments_nonhaplotype_DLE1_saphyr_human.xml

Inconsistencies between optical mapping data and Verkko assemblies were identified based on variant calls from approach 1 using “exp_refineFinal1_merged_filter_inversions.smap” output file. Variants were filtered out based on the following criteria: a) variant size smaller than 500 base pairs; b) variants labeled as “heterozygous”; c) translocations with a confidence score of ≤0.05 and inversions with a confidence score of ≤0.7 (as recommended on Bionano Solve Theory of Operation: Structural Variant Calling - Document Number: 30110); d) variants with a confidence score of <0.5. Variant reference start and end positions were then used to evaluate the presence of single molecules, which span the entire variant using alignment results from approach 2. Alignments with a confidence score of <30.0 were filtered out. Hybrid scaffolding results, conflict sites provided in “conflicts_cut_status.txt” output file from approach 3 were used to evaluate if inconsistencies identified above based on optical mapping variant calls overlap with conflict sites (i.e., sites identified by hybrid scaffolding pipeline representing inconsistencies between sequencing and optical mapping data) (Table S50). Furthermore, we used molecule alignment results to identify coordinate ranges on each Verkko assembly, which had no single DNA molecule coverage using the same alignment confidence score threshold of 30.0, as described above, dividing assemblies into 10 kbp bins and counting the number single molecules covering each 10 kbp window (Table S51).

d. De novo assembly annotation

Annotation of Y-chromosomal subregion

The 24 Y-chromosomal subregion coordinates (Table S13) relative to the GRCh38 reference sequence were obtained from8. Since Skov et al. produced their annotation on the basis of a coordinate liftover from GRCh37, we updated some coordinates to be compatible with the following publicly available resources: for the pseudoautosomal regions we used the coordinates from the UCSC Genome Browser for GRCh38.p13 as they slightly differed. Additionally, Y-chromosomal amplicon start, and end coordinates were edited according to more recent annotations from65, and the locations of DYZ19 and DYZ18 repeat arrays were adjusted based on the identification of their locations using HMMER3 (v3.3.2)66 with the respective repeat unit consensus sequences from1.

The locations and orientations of Y-chromosomal subregions in the T2T Y were determined by mapping the subregion sequences from the GRCh38 Y to the T2T Y using minimap2 (v2.24, see above). The same approach was used to determine the subregion locations in each de novo assembly with subregion sequences from both GRCh38 and the T2T Y (Table S13). The locations of the DYZ18 and DYZ19 repeat arrays in each de novo assembly were further confirmed (and coordinates adjusted if necessary) by running HMMER3 (see above) with the respective repeat unit consensus sequences from1. Only tandemly organized matches with HMMER3 score thresholds higher than 1700 for DYZ18 and 70 for DYZ19, respectively, were included and used to report the locations and sizes of these repeat arrays.

A Y-chromosomal subregion was considered as contiguous if it was assembled contiguously from the subclass on the left to the subclass on the right (note that the DYZ18 subregion is completely deleted in HG02572), except for pseudoautosomal regions where they were defined as >95% length of the T2T Y pseudoautosomal regions and with no unplaced contigs. Note that due to the requirement of no unplaced contigs the assembly for HG02666 appears to have a break in PAR2 subregion, while it is contiguously assembled from the telomeric sequence of PAR1 to telomeric sequence in PAR2 without breaks (however, there is a ~14 kbp unplaced PAR2 contig aligning best to a central region of PAR2). The assembly of HG01890 however has a break approximately 100 kbp before the end of PAR2. Assembly of PAR1 remains especially challenging due to its sequence composition and sequencing biases9,10, and among our samples was contiguously assembled for 10/43 samples, while PAR2 was contiguously assembled for 39/43 samples.

Annotation of centromeric and pericentromeric regions

To annotate the centromeric regions, we first ran RepeatMasker (v4.1.0) on 26 Y-chromosomal assemblies (22 samples with contiguously assembled pericentromeric regions, 3 samples with a single gap and no unplaced centromeric contigs, and the T2T Y) to identify the locations of α-satellite repeats using the following command:

RepeatMasker -species human -dir {path_to_directory} -pa {num_of_threads} {path_to_fasta}

Then, we subsetted each contig to the region containing α-satellite repeats and ran HumAS-HMMER (v3.3.2; https://github.com/fedorrik/HumAS-HMMER_for_AnVIL) to identify the location of α-satellite higher-order repeats (HORs), using the following command:

Hmmer-run.sh {directory_with_fasta} AS-HORs-hmmer3.0–170921.hmm {num_of_threads}

We combined the outputs from RepeatMasker (v4.1.0) and HumAS-HMMER to generate a track that annotates the location of α-satellite HORs and monomeric or diverged α-satellite within each centromeric region.

To determine the size of the α-satellite HOR array (reported for 26 samples in Table S16, while size estimates reported in results section include 23 gapless assemblies - see Table S15), we used the α-satellite HOR annotations generated via HumAS-HMMER (v3.3.2; described above) to determine the location of DYZ3 α-satellite HORs, focusing on only those HORs annotated as “live” (e.g., S4CYH1L). Live HORs are those that have a clear higher-order pattern and are highly (>90%) homogenous67. This analysis was conducted on 21 centromeres (including the T2T Y, Extended Data Fig. 8a), excluding 5/26 samples (NA19384, HG01457, HG01890, NA19317, NA19331), where, despite a contiguously assembled pericentromeric subregion, the assembly contained unplaced centromeric contig(s).

To annotate the human satellite III (HSat3) and DYZ17 arrays within the pericentromere, we ran StringDecomposer (v1.0.0) on each assembly centromeric contig using the HSat3 and DYZ17 consensus sequences described in Altemose, 2022, Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology68 and available at the following URL: https://github.com/altemose/HSatReview/blob/main/Output_Files/HSat123_consensus_sequences.fa We ran the following command:

stringdecomposer/run_decomposer.py {path_to_contig_fasta} {path_to_consensus_sequence+fasta} -t {num_of_threads} -o {output_tsv}

The HSat3 array was determined as the region that had a sequence identity of 60% or greater, while the DYZ17 array was determined as the region that had a sequence identity of 65% or greater.

5. Downstream analysis

a. Effect of input read depth on assembly contiguity

We explored a putative dependence between the characteristics of the input read sets, such as read length N50 or genomic coverage, and the resulting assembly contiguity by training multivariate regression models (“ElasticNet” from scikit-learn v1.1.1, see “Code Availability” statement in main text). The models were trained following standard procedures with 5-fold nested cross-validation (see scikit-learn documentation for “ElasticNetCV”). We note that we did not use the haplogroup information due to the unbalanced distribution of haplogroups in our dataset. We selected basic characteristics of both the HiFi and ONT-UL input read sets (read length N50, mean read length, genomic coverage and genomic coverage for ONT reads exceeding 100 kbp in length, i.e., the so-called ultralong fraction of ONT reads; Table S53) as model features and assembly contig NG50, assembly length or number of assembled contigs as target variable.

b. Locations of assembly gaps