Abstract

Background

The evidence-based Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) released in August 2020 were developed through a systematic literature review and patient-oriented research process. This CPG is considered a paradigm shift for obesity care as it introduced a new obesity definition that is based on health not body size, incorporates lived experiences of people affected by obesity, and addresses the pervasive weight bias and stigma that patients face in healthcare systems. The purpose of this pilot project was to assess the feasibility of adapting the Canadian CPG in Chile and Ireland.

Methods

An International Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation Committee was established to oversee the project. The project was conducted through four interrelated phases: 1) planning and preparation; 2) pilot project application process; 3) adaptation; and 4) launch, dissemination, and implementation. Ireland used the GRADE-ADAPTE framework and Chile used the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT approach.

Results

Chile and Ireland developed their adapted guidelines in one third of the time it took to develop the Canadian guidelines. In Ireland, 18 chapters, which underpin the 80 key recommendations, were contextually adapted. Chile adopted 18 chapters and 76 recommendations, adapted one recommendation, and developed 12 new recommendations.

Conclusion

The pilot project demonstrated it is feasible to adapt the Canadian CPG for use in other countries with different healthcare systems, languages, and cultural contexts, while retaining the Canadian CPG's key principles and values such as the treatment of obesity as a chronic disease, adoption of new clinical assessment approaches that go beyond anthropometric measurements, elimination of weight bias and stigma, shifting obesity care outcomes to improved health and well-being rather than weight loss alone, and the use of patient-centred, collaborative and shared-decision clinical care approaches.

Keywords: Obesity management, Clinical practice guidelines, Adaptation

1. Introduction

Research has rapidly advanced our understanding of obesity as a chronic disease over the past several years. However, outdated, simplistic and stigmatising attitudes – which hold that obesity is merely the result of positive caloric imbalance arising from poor personal choices remain widely and deeply entrenched in global health care policy and clinical practice settings.

Obesity Canada (OC), a registered charity established in 2007, in collaboration with the Canadian Association of Bariatric Physicians and Surgeons (CABPS), published an evidence-based and patient-centred Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) in 2020 [1]. The guideline and its 80 recommendations were developed using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) framework [2] and a patient-oriented research process [3] that involved interdisciplinary researchers, independent methodologists, clinicians, knowledge translation experts, people living with obesity, and Indigenous communities. A summary article was subsequently published in the Canadian Medical Journal [1], alongside 19 supplemental, in-depth chapters published on the OC website [4].

The launch of the CPG received significant international attention as it represents a comprehensive systematic review and synthesis of the literature in obesity care [5]. Organizations and individuals in several countries immediately expressed an interest in endorsing and/or adapting the guideline for use in their jurisdictions given the extensive human, financial and technical resources required to create a de novo CPG. However, while guidelines in other chronic disease spaces such as lung cancer, psychosis, and rheumatology [[6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]] have successfully demonstrated adaptation from one country to another, an adaptation of an obesity CPG had, to our knowledge, never been implemented.

Here, we present an overview and analysis of a pilot project to adapt the CPG in both Ireland and Chile, each with unique linguistic, cultural, population, and health system characteristics.

2. Methods

2.1. Governance

To guide this pilot project, OC established an International Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation Committee (“the Committee”), composed of Canadian guideline authors (n=9) and strategic partners (OC, CABPS, and the European Association for the Study of Obesity [EASO]) (Appendix 1). The mandate of the Committee was to provide guidance in identifying and following an adaptation process and to ensure key principles and values (e.g., health and patient-centredness), language and tone (e.g., person-first language), key concepts (e.g., obesity framed as a chronic disease) and definitions (e.g., obesity is defined as excess or abnormal adiposity that impairs health) of the CPG were maintained. The project was conducted through four interrelated phases: 1) planning and preparation; 2) pilot project application process; 3) adaptation; and 4) launch, dissemination, and implementation.

2.2. Phase I: planning and preparation (3 months)

In this project phase, the Committee: (1) conducted a literature review on existing guideline adaptation methods in any disease space using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations)-ADAPTE [24] and GRADE-ADOLOPMENT [25,26] methodologies (Appendix 2); (2) developed international pilot project criteria and application process to select pilot study participants (Table 1); (3) created a guideline licensing agreement; (4) created a universal version of the guideline by removing Canadian-specific context and data; and (5), identified universal key principles, values, recommendations, and evidence (flagged by the Committee as transferable, evidence-based and patient-centred practices that can improve obesity care globally) that could not be altered in or removed from the adapted CPGs (Appendix 3).

Table 1.

Selection criteria for the international guideline adaptation project.

| Pilot Site Selection Criteria |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

All 19 chapters and their accompanying references were organized into separate, editable word processing files and stored on a popular and secure file-sharing platform (Dropbox Vault); adaptation teams could thus easily access the content, and the Committee could easily track changes made to the original CPG. Sharable versions of the original CPG research questions for each chapter were also made available. The full literature search strategies and independent methods reports for each chapter were not shared due to contractual agreements between OC and the McMaster University Evidence Review and Synthesis Team, who conducted the original CPG literature search.

The Committee met monthly during the initial three-month planning phase to agree on the level of oversight and approval required by Canadian authors and committee members. It was agreed that countries could adapt (some changes), adopt (no changes), or create new recommendations as needed, without prior review or approval by Canadian authors, OC or CABPS. However, adapting organizations would be required to create their own oversight committee that, in accordance with the GRADE framework, would be responsible for reviewing and approving country specific chapters and final recommendations. To ensure that key principles and values of the Canadian guidelines were respected and retained, the guideline adaptation teams were required to specify changes to the original Canadian recommendations, to provide a justification for changes, to acknowledge the original Canadian guideline authors, and to submit the final adapted guideline recommendations and chapters for review by the Committee's project manager and research assistant.

2.3. Phase II: pilot project application process (3 months)

An open call for applications to potential countries interested in guideline adaptation was launched between February and May 2021 through OC's and EASO's newsletters and social media. Representatives from organizations in eight countries applied. The Committee predetermined that two applications from varied settings would be selected: one from a predominantly English-speaking country and another from the Latin American region. The Committee reviewed submissions against the project criteria (Table 1) and selected Chile, under the leadership of the Sociedad Chilena de Cirugía Bariátrica y Metabólica (Chilean Society of Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery) (SCCBM) and Ireland, under the leadership of the Association for the Study of Obesity for the island of Ireland (ASOI). In Ireland, the application involved an ASOI partnership with the Irish Health Care Executive (HSE) National Clinical Programme for Obesity and the Irish Coalition for People Living with Obesity (ICPO). Chile and Ireland were selected because they met all the pilot site selection criteria.

2.4. Phase II: stakeholder engagement (3 months)

The Irish and Chilean teams created guideline executive committees, who identified local specialists/authors as well as national and regional professional associations that could champion and participate in the guideline adaptation process. In Chile, the Executive Committee coordinated by SCCBM established an interdisciplinary committee that included the Asociación Chilena de Nutrición y Metabolismo (ACHINUMET), the Sociedad Chilena de Medicina Familiar (SOCHIMEF), the Sociedad Chilena de Neurología, Psiquiatría Y Neurocirugía (SONEPSYN), the Sociedad Chilena de Nutrición (SOCHINUT), the Sociedad Chilena de Medicina del Sueño (SOCHIMES) and the Sociedad Chilena de Obstetricia y Ginecología (SOCHOG). In Ireland, the ASOI, the ICPO and the HSE-NCP established an Executive Committee that worked alongside 70 specialists from all over Ireland. A guideline adaptation coordinator was hired in each country to manage stakeholder relations, local guideline steering committee activities, as well as coordination with chapter authors and independent methods experts. Each steering committee recruited a part-time research or administrative assistant to support the adaptation process. OC and EASO recruited a part-time project manager and a full-time research assistant to oversee the pilot study, manage the Committee, and coordinate adaptation and research activities. This work included an adaptation methods literature review, needs assessments with persons living with obesity, healthcare professionals, and policy makers in Chile, Ireland and Canada, feedback surveys from pilot site participants, and guideline launch communications strategies.

2.5. Phase III: adaptation (12 months)

Local guideline adaptation committees identified specialists to review Canadian guideline recommendations and lead individual chapter adaptations while contributing country-specific health system data and knowledge to the process. Weekly meetings with the project consultant and research assistant and the local guideline adaptation coordinators were conducted. To identify and manage project implementation issues, the project team (consultant, research assistant and local coordinators) reviewed recorded meeting notes from all project meetings. These meetings helped identify country-specific contextual factors that may have impacted the adaptation process and outcomes. Adaptation process information generated and collected from all sources, including author surveys, literature review, and project meetings were analysed to understand the barriers and facilitators for adapting the guidelines in different countries.

Weekly meetings with project coordinators in Chile and Ireland facilitated the resolution of key questions and concerns that arose during the adaptation phase. Through iterative discussions with ASOI and SCCBM, the team considered issues such as availability of obesity treatments, products, and services. For example, Chile has additional pharmacological and surgical treatments options that are not available in Canada or Ireland.

Recommendations for obesity treatments available in Chile that were not included in the original Canadian guidelines were developed using the same GRADE methodology [27] and the Evidence-to-Decision (EtD) framework [28,29]. Recommendations for obesity treatment products, programs, or services that were not available or approved Chile or Ireland were removed. An explanation for deletions was included in all these cases. In cases where new obesity treatments were emerging or pending approval, the evidence for such treatments was discussed in the body of the chapter. However, no recommendations for these unavailable or unapproved obesity treatments were included.

2.6. Phase IV: launch, dissemination, and implementation (3 months)

Healthcare professionals, people living with obesity, and policy makers were informed about the adapted guidelines in Ireland and Chile through communications activities such as: online publication of the adapted guidelines; in-person guideline launch events with key stakeholders in both Dublin and Santiago; media outreach; patient engagement via partnerships with a patient advocacy organization in Ireland (ICPO) and the creation of patient tools; an online education course for healthcare professionals; and a qualitative study to assess policy makers’ perceived barriers and facilitators for guideline implementation.

2.7. Process evaluation

An online evaluation survey (Appendices 4 and 5) was conducted at the conclusion of the adaptation process to inform future adaptation processes. The goal was to determine whether the Canadian guideline recommendations were created in a way that would allow health care professionals in other countries to understand, adapt/adopt and implement them within their country specific context.

3. Results

3.1. Pilot site engagement and adaptation processes

The first phase (planning and preparation) took approximately six months. A total of 58 obesity specialists were engaged in Chile and 63 in Ireland. The original Canadian CPG was translated to Spanish by an independent professional medical translator. Chapter authors were responsible for ensuring that the translation was accurate and reflective of Chilean linguistic and cultural contexts.

During the stakeholder engagement phase (three months), pilot sites decided on which methodology to use for their adaptation process and which chapters they were going to adapt. Ultimately, 18 out of the 19 original CPG chapters were selected for adaptation in both countries, with exclusion in both cases of the Canadian-specific Indigenous chapter.

Chile selected the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT [28,29] approach and Ireland selected the GRADE-ADAPTE process [24]. GRADE-ADOLOPMENT approach combines adoption (no changes), adaptation (some changes), and de novo development of new recommendations as needed. The GRADE-ADAPTE process provides a systematic approach to adapting guidelines for use in different cultural and organizational contexts but does not include the creation of de novo (new) recommendations. The specific methodology for the adaptation process in each country has been published previously in the adapted guidelines [[30], [31], [32]].

A key learning from this phase is that guideline adaptation teams must consider which methodology to use based on the applicability to local health policy and acceptance by relevant policy makers to enlist their support for implementation of the guideline. Chile decided on the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT approach because it would allow them to create new PI/PECOT (Population, Intervention or Exposure, Comparison, Outcome, Time) questions that are specific to the Chilean health system and population, while complying with requirements from policy makers in the Chilean Ministry of Health. To support the creation of new research questions, systematic reviews of the literature, and the development of new recommendations, Chile used an independent methods expert team (Epistemonikos). Ireland chose the GRADE-ADAPTE process as it was in line with previous adaptation processes under the Irish National Clinical Effectiveness Committee (NCEC), which provides a framework for endorsement of clinical guidelines that promote evidence-based healthcare [24].

The adaptation phase was 12 months in duration. From the outset, the Chilean and the Irish guideline adaptation committees recognized that the Canadian guideline established a major change in the narrative and scope of obesity care. For context, the Canadian guideline established a new obesity definition that is based on how excess and/or abnormal body fat impairs a person's health, and not solely on body weight or body size. The guideline also recommends the use of body mass index (BMI) as a screening tool rather than a diagnostic tool. In addition, the Edmonton Obesity Staging System (EOSS) tool is recommended to assess the severity of the disease in patients and to help identify root causes of obesity in each patient, which can then inform treatment options that can be tailored and agreed upon between health care providers and patients [33]. A webinar was organized by the Committee with Canadian, Chilean, and Irish authors to provide a more detailed overview of the recommendations in the Canadian guideline, focusing on recommendations from the obesity clinical assessment and diagnosis chapter.

3.2. Results and evaluation in Ireland

In Ireland, 18 chapters from the Canadian guideline were contextually adapted. The Irish guideline is available as a living document on the ASOI website and a summary of the CPGs describing the adaptation project was published in Obesity Facts [30]. A survey for Irish authors gathered feedback regarding use of the ADAPTE Tool 15 [24], which authors used to assess acceptability and applicability of the recommendations for each individual chapter. Irish authors assessed the quality of each CPG chapter and how they determined whether recommendations would be appropriate for Ireland. Irish authors also provided feedback about how they determined if the recommendations were applicable to patients living in Ireland. A total of 45 Irish authors completed the online survey to provide feedback on the adaptation process; 33% of the survey respondents were lead authors and 67% were co-authors. Irish guideline adaptation authors agreed that the original Canadian recommendations met the necessary criteria to be adapted for Ireland. This was determined using the various ADAPTE tools previously described. More than half (60%) of the respondents stated that they adapted the original recommendations. Authors made changes to the recommendations to:

-

1)

Make word changes and language edits agreed upon by the writing groups (41%);

-

2)

Make the guidelines more specific to the Irish context (38%); and,

-

3)

Integrate updated evidence that changed the context of the recommendation (16%).

Based on their experience adapting the original CPG, 96% of the survey respondents agreed that it is feasible to create an evidence synthesis framework for future guideline updates. Irish authors also identified new evidence which may change the recommendations using the ADAPTE Tool 15 which was shared with the Committee for consideration in future guideline updates. All survey respondents (100%) agreed that the guideline adaptation process was worthwhile and were appreciative of the support of the local guideline adaptation coordinator for facilitating the process.

Debriefs with the local Irish project coordinator identified a few challenges in the early phases of the project, including longer timeframes to develop funding agreements to provide part-time clinical backfill for the coordinator. Identifying and recruiting authors for all 18 chapters also took longer than anticipated, as the local CPG Steering Committee made significant efforts to engage specialists from all regions of Ireland and from different disciplines and experience levels. The fact that the Irish obesity care community is well connected was seen as a facilitator to the project. As well, early and ongoing engagement with key stakeholders in the Irish HSE National Clinical Programme for Obesity, the government agency charged with oversight of the development and delivery of obesity care, was also identified as a key facilitator. Reference to the Canadian CPG by Ireland in its Model of Care for Obesity, which had been published in 2021, underpinned the collaborative approach to the adaptation pilot [34]. Finally, strong support from the Irish CPG Steering Committee, including participation from ICPO was also identified as a facilitator for the implementation of this project. Overall, the collaboration between the ASOI and the ICPO facilitated the adaptation process by more fully integrating the perspectives and language preferences of patients living with obesity, making chapters and recommendations less stigmatising and more practical for people to use to advocate for their own care. Two ICPO representatives were co-authors on chapters, further increasing meaningful participation in the adaptation process.

3.3. Results and evaluation in Chile

Chile adopted 18 chapters and 76 recommendations, adapted one recommendation, and developed 12 de novo (new) recommendations. De novo recommendations were prioritised by the executive committee and developed using the Evidence-to-Decision Framework (EtD). A systematic review of the literature was carried out on the Living OVerview of Evidence (LOVE) platform hosted by Epistemonikos [35]. The Chilean CPG is a living document, and a summary of the Chilean guideline was published in Medwave [31]. An independent website was created with all the chapters and associated resources, aimed at healthcare professionals, policy makers and people living with obesity [36].

A survey for Chilean authors was designed to collect feedback about the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT approach. However, since the local committee and authors opted to have an independent methods expert team (Epistemonikos) oversee the process of adapting, adopting, or creating de novo recommendations, most authors did not complete the survey. Instead, the independent methods team prepared a detailed summary explaining the process used to decide whether to adopt, adapt, or create a new recommendation [32].

Furthermore, discussions with the Chilean project coordinator revealed some barriers and facilitators for the guideline adaptation process. There were several aspects in the assessment chapter that were challenging for the Chilean adaptation team. First, EOSS has not been validated in a Chilean population, and authors had to consider how to introduce this new tool to Chilean healthcare professionals. Although EOSS has not been validated in the Canadian or Irish populations either, it has been used widely in different countries [[37], [38], [39]] and clinicians in Canada and Ireland are more familiar with the tool and have been using it for several years. The Irish Adult Obesity Model of Care references and recommends the use of EOSS [34].

Second, the use of BMI as a diagnostic tool for obesity is very common in Chilean clinical practice and health services policies. BMI is often used as a cut-off criterion for various health services, including bariatric surgery. The shift to make BMI a screening tool rather than a diagnostic tool required more discussion within the Chilean adaptation team. (In Ireland, on the other hand, the use of BMI as a screening tool was already established in the Irish Obesity Model of Care, which was informed by the Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines.)

Another key challenge identified in Chile was the existence of several organizations that have a mandate on obesity prevention and management. Although the lead organisation for the adaptation process was SCCBM, Chile adopted a collaborative approach by inviting six other scientific organizations and professional associations to participate in the process. Leaders from these organizations were invited to join writing and adaptation groups for the guideline chapters. SCCBM also recruited an interdisciplinary obesity specialist to coordinate the project. The role of the project coordinator proved to be critical in terms of creating interdisciplinary teams for each chapter and for moving the project forward.

An additional challenge in Chile was a lack of patient engagement. Despite initial efforts to engage a patient group that could participate meaningfully in the adaptation process, this was not possible. The Chilean guideline executive committee was not able to create an administrative structure capable of making an open and transparent call for organizations and/or interested individuals to participate in a meaningful way (i.e., availability of time for weekly meetings, full professional competence in English, participation in representative non-governmental organizations, among other criteria). As a result, patients living with obesity did not participate in the Chilean guideline adaptation process. This made it more difficult to incorporate the perspectives of Chilean patients in the adaptation of Canadian recommendations as well as in the development of new Chilean specific recommendations. However, following the launch of the adapted guidelines in Chile, new efforts were being deployed to engage patients living with obesity in guideline dissemination and implementation activities. The Chilean guideline executive committee also plans to convene individuals and patient organizations in future guideline updates, ensuring an active involvement that reflects patient capabilities and contributions.

3.4. Common experience

A key common barrier identified in both Chile and Ireland was the lack of authors’ experience in the development of clinical practice guidelines using the GRADE framework. To facilitate the adaptation process in Chile, Epistemonikos provided training for Chilean authors focusing on the GRADE framework that was used in the Canadian guideline and the Evidence-to-Decision (EtD) framework which was used to create new Chilean-specific recommendations. In Ireland, this barrier was addressed by implementing the ADAPTE toolkit systematically and by providing clear and detailed instructions to authors on how to approach the adaptation and on how to use the ADAPTE Tool 15.

Authors in Chile and Ireland agreed that healthcare professionals need more training on how to operationalize the new obesity definition, and specifically how to use EOSS and the 4Ms (Metabolic, Mechanical, Mental and Social Milieu) of Obesity Management tools included in the guideline. There was also agreement that more obesity education is needed among primary care professionals, patients living with obesity, and policy makers, particularly around the use of the BMI as a clinical screening tool or population level surveillance measurement rather than a diagnostic tool. Key messages on obesity assessment and diagnosis beyond BMI were therefore incorporated into communications strategies for the launch of the adapted guidelines in Chile and Ireland.

3.5. Overall pilot project outcomes

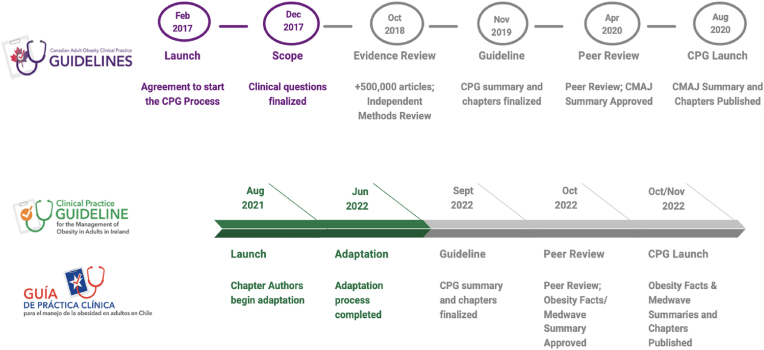

The adaptation phase was 12 months in each country and the launch and dissemination phase was approximately three months. Chile and Ireland were able to create their adapted guidelines in one third the time required to develop the Canadian guidelines (Fig. 1). Adaptation costs in Ireland and Chile were $250,000 USD, representing a saving of approximately $750,000 USD compared with the cost of creating the de novo Canadian guidelines (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guideline Development Process & Timeline compared with CPG Adaptation Process and Timeline in Ireland and Chile.

Table 2.

Comparison of resources and timelines to develop Canadian, Irish, and Chilean clinical practice guidelines.

| Number | Canada | Ireland | Chile |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specialists, authors, patients living with obesity | 60 | 65 | 58 |

| Recommendations | 80 | 80 | 76 adopted |

| 1 adapted | |||

| 12 de novo | |||

| Chapters | 19 | 18 | 18 |

| Summary | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Collaborators | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| Development/Adaptation time (excluding planning and preparation time) | 3 years | 12 months | 12 months |

| Costsa | > $1 Million USD | $250,000 USD | $250,000 USD |

Costs include country-specific operational, research, dissemination, and implementation activities, which were allocated through a grant provided from OC and EASO to ASOI and SCCBM. Some country-specific and general pilot project costs that were coordinated through OC and EASO directly are also included project coordinator and research assistant salaries, independent methods expert team fees, Spanish translation, expert consultants (research consultants, writers, editors, website and graphic designers, communications, and media), and dissemination materials, in-person workshop at the European Congress on Obesity in 2022, and launch events in Chile and Ireland.

The pilot project for both countries engaged over 130 obesity specialists, individuals with obesity in Ireland, independent methods experts, policy makers, and healthcare professionals (in Canada, Chile, and Ireland). The pilot served as a catalyst to build an international community of clinicians, scientists, and people living with obesity who are working together to improve obesity care, using consistent evidence and messaging.

4. Conclusion

The pilot project demonstrated that it is feasible to adapt the Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guideline for use in other countries with different healthcare systems, languages, and population characteristics, while maintaining the original guideline's key principles, revised obesity narrative, and obesity care scope. Specifically, the treatment of obesity as a chronic disease, the operationalization of the new obesity definition through new obesity clinical assessment strategies that go beyond anthropometric measurements, the need to eliminate weight bias and stigma in healthcare settings, the shift of obesity care outcomes to improved health and well-being rather than weight loss alone, and the use of patient-centred, collaborative and shared-decision clinical care approaches were retained.

Our findings align with previous findings indicating that; i) adapting a clinical practice guideline, ii) considering local evidence and even identifying new specific research questions relevant to a local context, and iii) considering specific needs, priorities, legislation, policies, and resources available in different countries, including scopes of clinical practice within different health services or existing models of healthcare delivery, are all possible [41]. The adaptation was far more cost-effective, producing significant financial, time and human resource savings compared to de novo guidelines.

As observed in other disease areas, our study demonstrated that the GRADE-ADAPTE process and the GRADE-ADOLOPMENT approach can be modified to fit the needs of guideline development groups. The decision on which approach to use should consider local contexts such as policies that may facilitate guideline implementation. Whether adapting a clinical practice guideline for the local context improves uptake and implementation of the guidelines remain to be assessed.

Since the launch of the adaptation program, several other countries have expressed interest in adapting/adopting the Canadian, Irish, or Chilean guidelines. Our hope is that the science and scientific/clinical experience – the backbone of all three guidelines – will continue to inspire and motivate decision makers worldwide to strive to reduce stigma and improve access to care for all people living with obesity, using evidence-informed treatments and a commitment to patient-centred care as a foundation to progress.

Authorship statement

The concept of the submission was by XRS and MSC. Data analysis and curation was performed by MSC and XRS. MF, SW, DCS, XRS, JB, SDP, MV, and AMS participated as members of the International Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation Committee. EW participated as a representative of the European Association for the Study of Obesity. NP and IP represented Obesity Canada. XRS, MSC, CB, YP, and BH wrote the first draft. MF, SW, DCS, XRS, JB, SDP, MV, AMS, EW, CB, YP, NP, IP, and BH all reviewed, edited, and approved the final submission and publication.

Ethical review

As this is a clinical practice guideline adaptation pilot project, ethical review was not required.

Funding

Funding for producing the original Canadian guideline came from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategic Patient-Oriented Research initiative, OC's Fund for Obesity Collaboration and Unified Strategies (FOCUS) initiative, CABPS, and in-kind support from the scientific and professional volunteers engaged in the process. The international adaptation pilot funding came from OC and EASO based on an unrestricted grant from Novo Nordisk Global. Novo Nordisk was not involved with the implementation of the project. Committee members and adapting authors were volunteers and were not remunerated for their services. Obesity Canada provided funding for editorial assistance for this manuscript.

Declaration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors did not use AI- assisted technologies.

Declaration of competing interest

XRS was contracted to coordinate the international guideline adaptation project by Obesity Canada and the European Association for the Study of Obesity. MSC was contracted as a research assistant by Obesity Canada for the duration of the pilot project. CB reports backfill time payment from the Association for the Study of Obesity on the island of Ireland to her employer at St Columcille's Hospital while acting as project coordinator for the pilot project in Ireland. YP reports backfill time payment from the Sociedad Chilena de Cirugía Bariátrica y Metabólica and Obesity Canada while acting as project coordinator for the pilot project in Chile. BH was contracted to coordinate communications activities for the guideline adaptation project by Obesity Canada and the European Association for the Study of Obesity. He also provided writing, editing, and proof-reading assistance for this manuscript. MF was the Scientific Director of Obesity Canada (unpaid) and the Chair of the Canadian Guideline Adaptation Committee (unpaid) for the duration of this project. SW, DCS, MV, JB, SDP, and AMS were unpaid members of the Canadian Guideline Adaptation Committee. EW is an employee of the European Association for the Study of Obesity. IP and NP are employees of Obesity Canada.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge guideline adaptation authors, executive committee members, and communications experts and volunteers in Chile and Ireland for their contributions to this project, in addition to all those involved in the original CPG development in Canada. The authors also thank Randy Cameron for his contributions for the development of the adapted guidelines' websites, online resources, tables, and figures.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obpill.2023.100090.

Contributor Information

Ximena Ramos Salas, Email: ximenars@gmail.com.

Miguel Alejandro Saquimux Contreras, Email: asaquimux@yahoo.com.

Cathy Breen, Email: cathybreen24@gmail.com.

Yudith Preiss, Email: yudith.preiss@gmail.com.

Brad Hussey, Email: brad@replicagroup.com.

Mary Forhan, Email: mary.forhan@utoronto.ca.

Sean Wharton, Email: sean@whartonmedicalclinic.com.

Denise Campbell-Scherer, Email: dlcampbe@ualberta.ca.

Michael Vallis, Email: tvallis@dal.ca.

Jennifer Brown, Email: brown@obesitynetwork.ca.

Sue D. Pedersen, Email: drsuepedersen@gmail.com.

Arya M. Sharma, Email: amsharm@ualberta.ca.

Euan Woodward, Email: ewoodward@easo.org.

Ian Patton, Email: patton@obesitynetwork.ca.

Nicole Pearce, Email: pearce@obesitynetwork.ca.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Wharton S., Lau D.C.W., Vallis M., et al. Obesity in adults: a clinical practice guideline. CMAJ (Can Med Assoc J) 2020;192(31):E875–E891. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.191707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siemieniuk R., Guyatt G. What is GRADE?. BMJ best practice. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-is-grade August 21st, 2023.

- 3.Canadian Institutes of Health Research Strategy for patient-oriented research. https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/41204.html Published March 3, 2023. (Accessed August 21st, 2023)

- 4.Obesity Canada. https://obesitycanada.ca/guidelines/chapters/. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Adults. Published August 4, 2020. (Accessed August 11th, 2023).

- 5.Batterham R.L. Switching the focus from weight to health: Canada's adult obesity practice guideline set a new standard for obesity management. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;31 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anuwar A.H.K., Ab-Murat N. Developing clinical practice guidelines for dental caries management for the Malaysian population through the ADAPTE trans-contextual adaptation process. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2021;19(1):217–227. doi: 10.3290/j.ohpd.b1179509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraborty S.P., Jones K.M., Mazza D. Adapting lung cancer symptom investigation and referral guidelines for general practitioners in Australia: reflections on the utility of the ADAPTE framework. J Eval Clin Pract. 2014;20(2):129–135. doi: 10.1111/jep.12097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoedl M., Schoberer D., Halfens R.J.G., Lohrmann C. Adaptation of evidence-based guideline recommendations to address urinary incontinence in nursing home residents according to the ADAPTE-process. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(15–16):2974–2983. doi: 10.1111/jocn.14501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.OPS/OMS - Secretaría de Salud de la República de Honduras Instituto Hondureño de Seguridad Social.Honduras, Guía de Práctica Clínica para el Manejo Ambulatorio (Promoción, Prevención, Diagnóstico, Tratamiento y Seguimiento) del Adulto con Diabetes Millitus Tipo. Honduras. 2015;2 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hurtado M.M., Quemada C., Garcia-Herrera J.M., Morales-Asencio J.M. Use of the ADAPTE method to develop a clinical guideline for the improvement of psychoses and schizophrenia care: example of involvement and participation of patients and family caregivers. Health Expect. 2021;24(2):516–524. doi: 10.1111/hex.13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irajpour A.M., Hashemi M., Taleghani F. 2021. Clinical practice guideline for end-of-life care in patients with cancer: a modified ADAPTE process. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nogueras E.V., Hurtado M.M., Flordelis E., Garcia-Herrera J.M., Morales-Asencio J.M. Use of the ADAPTE method to develop a guideline for the improvement of depression care in primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(8):759–761. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberge P., Fournier L., Brouillet H., et al. A provincial adaptation of clinical practice guidelines for depression in primary care: a case illustration of the ADAPTE method. J Eval Clin Pract. 2015;21(6):1190–1198. doi: 10.1111/jep.12404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selby P., Hunter K., Rogers J., et al. How to adapt existing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines: a case example with smoking cessation guidelines in Canada. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arayssi T., Harfouche M., Darzi A., et al. Recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis in the Eastern Mediterranean region: an adolopment of the 2015 American College of Rheumatology guidelines. Clin Rheumatol. 2018;37(11):2947–2959. doi: 10.1007/s10067-018-4245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coronado-Zarco R., Olascoaga-Gomez de Leon A., Faba-Beaumont M.G. Adaptation of clinical practice guidelines for osteoporosis in a Mexican context. Experience using methodologies ADAPTE, GRADE-ADOLOPMENT, and RAND/UCLA. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;131:30–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darzi A., Harfouche M., Arayssi T., et al. Adaptation of the 2015 American college of rheumatology treatment guideline for rheumatoid arthritis for the eastern mediterranean region: an exemplar of the GRADE adolopment. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2017;15(1):183. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0754-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kahale L.A., Ouertatani H., Brahem A.B., et al. Contextual differences considered in the Tunisian ADOLOPMENT of the European guidelines on breast cancer screening. Health Res Pol Syst. 2021;19(1):80. doi: 10.1186/s12961-021-00731-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCaul M., Ernstzen D., Temmingh H., Draper B., Galloway M., Kredo T. Clinical practice guideline adaptation methods in resource-constrained settings: four case studies from South Africa. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2020;25(6):193–198. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2019-111192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neumann I., Izcovich A., Aguilar R., et al. ASH. ABHH. ACHO. Grupo CAHT. Grupo CLAHT. SAH. SBHH. SHU. SOCHIHEM. SOMETH Sociedad Panameña de Hematologia, SPH, and SVH 2021 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism in Latin America. Blood Adv. 2021;5(15):3032–3046. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neumann I., Izcovich A., Alexander K.E., et al. Methodology for adaptation of the ASH guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism for the Latin American context. Blood Adv. 2021;5(15):3047–3052. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okely A.D., Ghersi D., Hesketh K.D., et al. A collaborative approach to adopting/adapting guidelines - the Australian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for the early years (Birth to 5 years): an integration of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep. BMC Publ Health. 2017;17(Suppl 5):869. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4867-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reilly J.J., Hughes A.R., Janssen X., et al. GRADE-ADOLOPMENT process to develop 24-hour movement behavior recommendations and physical activity guidelines for the under 5s in the United Kingdom, 2019. J Phys Activ Health. 2020;17(1):101–108. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2019-0139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The ADAPTE Collaboration . Guideline International Network; 2009. The ADAPTE process: resource toolkit for guideline adaptation. Version 2.0. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schunemann H.J., Wiercioch W., Brozek J., et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks for adoption, adaptation, and de novo development of trustworthy recommendations: GRADE-ADOLOPMENT. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;81:101–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tugwell P., Knottnerus J.A. Adolopment - a new term added to the clinical epidemiology lexicon. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;81:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt G.H., Oxman A.D., Vist G.E., et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alonso-Coello P., Schunemann H.J., Moberg J., et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 1: introduction. BMJ. 2016;353 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alonso-Coello P., Oxman A.D., Moberg J., et al. GRADE Evidence to Decision (EtD) frameworks: a systematic and transparent approach to making well informed healthcare choices. 2: clinical practice guidelines. BMJ. 2016;353 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i2089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breen C., O'Connell J., Geoghegan J., et al. Obesity in adults: a 2022 adapted clinical practice guideline for Ireland. Obes Facts. 2022;15(6):736–752. doi: 10.1159/000527131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preiss Contreras Y., Ramos Salas X., Avila Oliver C., et al. Obesity in adults: clinical practice guideline adapted for Chile. Medwave. 2022;22(10) doi: 10.5867/medwave.2022.10.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Consorcio Chileno para el Estudio de la Obesidad. https://guiasobesidadchile.com/metodologia Metodología para el desarrollo de la Guía de Práctica Clínica. August 21st, 2023.

- 33.Rueda-Clausen C.F., Poddar M., Lear S.A., Poirier P., Sharma A.M. Obesity Canada; 2020. Canadian Adult obesity clinical practice guidelines: assessment of people living with obesity. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health Service Executive (HSE) Royal College of Physicians in Ireland; Dublin: 2021. Model of care for the management of overweight and obesity. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Epistemonikos Foundation https://iloveevidence.com/ L·OVE stands for Living OVerview of Evidence. August 22nd, 2023.

- 36.Consorcio Chileno para el Estudio de la Obesidad. https://guiasobesidadchile.com/ Obesidad en personas adultas: Guía de práctica clínica adaptada para Chile. August 17th, 2023.

- 37.Swaleh R., McGuckin T., Myroniuk T.W., et al. Using the Edmonton Obesity Staging System in the real world: a feasibility study based on cross-sectional data. CMAJ Open. 2021;9(4):E1141–E1148. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canning K.L., Brown R.E., Wharton S., Sharma A.M., Kuk J. Edmonton obesity staging system prevalence and association with weight loss in a publicly funded referral-based obesity clinic. J Obes. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/619734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez-Flores M., Goicochea-Turcott E.W., Mancillas-Adame L., et al. The utility of the Edmonton Obesity Staging System for the prediction of COVID-19 outcomes: a multi-centre study. Int J Obes. 2022;46(3):661–668. doi: 10.1038/s41366-021-01017-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.International Committee of Medical Journal https://www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/.Disclosure of Interest August 10th, 2023.

- 41.Harrison M.B., Legare F., Graham I.D., Fervers B. Adapting clinical practice guidelines to local context and assessing barriers to their use. CMAJ (Can Med Assoc J) 2010;182(2):E78–E84. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.081232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.