Summary

Background

The history of the primary healthcare system in Iran portrays a journey of strategic development and implementation that has resulted in significant advancements in healthcare access and overall population well-being. Starting in the early 1980s, Iran embarked on a comprehensive approach to health care delivery prioritizing universal access, equity, and community participation.

Introduction

The foundation of this system was established during the Alma-Ata Conference in 1978, which placed a strong emphasis on the role of primary health care in attaining health for all.

Iran’s unwavering commitment to this approach led to the creation of an extensive network of rural and urban health centers designed to offer essential health services and preventive care to all citizens.

Discussion

Over the years, the expansion of Iran’s primary healthcare system has yielded noteworthy accomplishments. Maternal and child mortality rates have seen substantial declines, attributed to improved access to maternal care and immunization services. The effectiveness of the system in reaching diverse populations has been enhanced through community engagement and the integration of traditional medicine. Furthermore, Iran’s focus on health education and disease prevention has resulted in heightened public awareness and the adoption of healthier lifestyles. Despite these achievements, challenges continue to persist. Disparities in the quality and accessibility of services between urban and rural areas remain a concern. Moreover, the ongoing necessity for infrastructure development, training of the health workforce, and efficient resource allocation underscore the continuous efforts required to strengthen the primary healthcare system.

Conclusions

The history of Iran’s primary health care system is marked by progress and achievements, underscored by an unwavering commitment to providing comprehensive, community-based care. Iran’s journey serves as an exemplary model, highlighting the positive impact of prioritizing primary health care in achieving better health outcomes for its population. As Iran continues to evolve its health system, addressing challenges and building upon successes, the history of its primary health care system serves as a valuable lesson in the pursuit of accessible and equitable health care for all.

Keywords: Primary health care, Iran, History of Public health, Health policy, Equitable health

Introduction

Primary Health Care (PHC) is a fundamental component of healthcare systems, characterized by its universal accessibility, community-based nature, comprehensiveness, and provision at the initial level of the healthcare system [1]. It is widely acknowledged as the bedrock of a well-functioning healthcare system, aiming to address the health requirements of both individuals and communities across their lifespan [2]. PHC takes a holistic approach to health and well-being, extending beyond medical care to encompass the social, economic, and environmental determinants of health [3].

Primary Health Care possesses several key characteristics

Accessibility: PHC aims to ensure unfettered access for all individuals, regardless of their social or economic standing. This objective is accomplished through community-based services and strategically positioned health centers, facilitating convenient proximity to the population [4].

Comprehensiveness: The range of healthcare needs is comprehensively covered by PHC services, encompassing preventive, promotive, curative, and rehabilitative elements. This comprehensive framework enables individuals to sustain good health and curtail the onset of diseases effectively [5].

Coordination: PHC emphasizes effective coordination and integration of various healthcare services, including medical, dental, mental health, and preventive care. This coordinated approach ensures a well-rounded provision of care that addresses every facet of an individual’s health [6].

Community Involvement: PHC fosters active participation from the community in the planning, execution, and evaluation of healthcare services. This collaborative engagement allows for the customization of services following the specific needs and cultural contexts of the population [7].

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention: PHC places significant emphasis on educating individuals and communities regarding healthy lifestyles and disease prevention. This proactive approach reduces the burden of illness and diminishes the necessity for complex and expensive treatments [8].

Early Detection and Management: PHC focuses on early detection and management of health issues. By addressing health problems in their early stages, PHC can often prevent the progression of diseases and complications [9].

Importance of PHC

Universal Access: PHC ensures the availability and accessibility of basic health services to all individuals, irrespective of their socioeconomic background. This is paramount in achieving health equity and reducing health disparities [10].

Cost-Effectiveness: By emphasizing prevention and early intervention, PHC can minimize the need for expensive medical interventions and hospitalizations. This generates cost savings for individuals, communities, and the healthcare system as a whole [11].

Population Health Improvement: The focus of PHC on health promotion and disease prevention contributes to the enhancement of overall population health. Healthy individuals are more productive and can make positive contributions to society [12].

Reduced Health Inequalities: PHC addresses the social determinants of health, thereby helping to bridge health outcome disparities between different population groups [13]

Stronger Health Systems: A robust PHC system forms the foundation of a well-functioning healthcare system. It establishes a referral pathway for specialized care when necessary and prevents the overwhelming of hospitals and specialized clinics [14].

Emergency Preparedness: Effective PHC systems can respond more efficiently to public health emergencies and disease outbreaks by promptly identifying and managing cases at the community level [15].

PHC is a fundamental approach to healthcare delivery that promotes health, prevents diseases, and provides essential services to communities. It plays a critical role in ensuring equitable access to healthcare, improving population health, and building resilient health systems [15].

The Alma-Ata Conference, also known as the International Conference on PHC, was a historic event held in Alma-Ata (now Almaty), Kazakhstan, in September 1978 [3]. The conference brought together representatives from various countries, international organizations, and health experts to discuss and endorse a groundbreaking approach to health care known as PHC [5]. The Alma-Ata Conference marked a significant turning point in global health policy by emphasizing the importance of PHC as a fundamental strategy for achieving health for all [15]. The conference’s declaration and strategy laid out a comprehensive and holistic approach to health care that went beyond the traditional medical model and focused on addressing the underlying social, economic, and environmental determinants of health [6].

Key Principles and objectives of the Alma-Ata Conference

Equity and Social Justice: The conference underscored the imperative of providing fundamental healthcare services to all individuals, regardless of their socioeconomic status. This approach aimed to mitigate health inequalities and disparities among various population groups [8].

Comprehensive Care: The PHC approach emphasizes the significance of delivering a broad spectrum of health services, encompassing preventive, promotive, curative, and rehabilitative care. It aimed to address the majority of health needs within a community [10].

Community Participation: The Alma-Ata Declaration acknowledged the significance of engaging communities in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of healthcare services. This community involvement ensured that health services were culturally sensitive and customized to local needs [9].

Intersectoral Cooperation: PHC stressed the importance of collaboration among diverse sectors, such as health, education, agriculture, and social welfare, to tackle the broader determinants of health and foster overall well-being [1].

Health Promotion and Disease Prevention: The conference underscored the importance of health promotion and disease prevention as integral components of PHC. This entailed educating individuals and communities about healthy behaviors and lifestyles [16].

Access to Essential Medicines: The Alma-Ata Declaration emphasized the vital role of ensuring access to essential medicines as a cornerstone of primary healthcare services [12].

The Alma-Ata Declaration culminated in the adoption of the “Health for All” goal, which sought to enable every individual to lead a socially and economically productive life by attaining a certain level of health [12]. The declaration called upon governments and international organizations to prioritize the establishment and development of PHC systems as a means to achieve this objective. While the Alma-Ata Conference and the PHC approach received widespread support and recognition, implementing PHC proved to be challenging in many contexts due to various barriers, including limited resources, political obstacles, and competing health priorities [2]. However, the principles laid out in the Alma-Ata Declaration continue to influence global health policies and strategies, emphasizing the importance of a comprehensive, community-based, and equitable approach to health care delivery [12].

Health system in Iran

The health system in Iran is characterized by a combination of public and private sectors, aiming to provide universal access to healthcare services for its population. The Iranian healthcare system comprises public and private healthcare providers, with the public sector being predominant [16]. This sector includes government-funded hospitals, clinics, and health centers. Although the private sector also contributes to healthcare provision, the majority of the population relies on the public sector for their healthcare needs. Iran places significant emphasis on primary healthcare, considering it a fundamental building block of its healthcare system. To cover a large portion of the population, Iran operates a national health insurance system called the Islamic Republic of Iran Health Insurance Organization. This system provides coverage for various health services, such as hospitalization, outpatient care, and prescription medications. The country has made considerable investments in developing a robust healthcare infrastructure, which includes hospitals, clinics, and medical facilities. This infrastructure is intended to facilitate the delivery of healthcare services across the country [17].

Medical education and training in Iran are well-established, with several reputable medical universities and institutions that educate medical professionals, including doctors, nurses, and allied health workers. In addition to conventional medicine, Iran has a rich history of traditional and complementary medicine [18].

Traditional Persian medicine continues to be practiced and integrated into the overall healthcare system. Iran also has a domestic pharmaceutical industry that produces a diverse range of medications. The government has taken steps to encourage domestic pharmaceutical production and reduce dependency on imported drugs. Like many countries, Iran faces various health challenges, including non-communicable diseases, infectious diseases, and disparities in access to health care services, particularly in rural and underserved areas [19].

PHC in Iran and its evolution over the years

In the years following World War II, mobile teams were established in Iran to combat diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and leprosy. These teams primarily consisted of individuals with 6 to 12 years of formal education, who had completed specialized courses. Over time, these individuals were also trained in diagnostic and vaccination practices.

In 1049, the “Tarbit Behdar” project was initiated in Mashhad, to supply manpower to rural areas. After completing a four-year program that encompassed theoretical, practical, and internship training, these individuals would serve in villages and departmental centers.

However, in the 1960s, the Tarbiat Behdar schools ceased their operations, and graduates gradually enrolled in Parashki colleges. Following completion of their rural service, these graduates pursued a minimum of three years of additional training to become doctors.

Since 1964, the health law has been implemented in Iran. According to this law, medical school graduates, graduates of related fields, and a select number of high school graduates who are surplus to the requirements of the army, are mandated to serve in the Ministry of Health. Under the supervision of physicians, diploma graduates are deployed in rural areas to provide medical treatment and ensure public health. Despite the positive impact of these health workers, challenges have arisen due to their unfamiliarity with village culture, incomplete deployment, and inconsistent workforce size. Consequently, the full potential of these health workers has not been fully realized.

In 1972, a research project was implemented in cooperation with the World Health Organization (WHO), the Faculty of Health at the University of Tehran, in West Azarbaijan province, Iran. The project aimed to develop medical and health services by establishing a system for providing services and utilizing non-physician personnel in peripheral units. Concurrently, other similar projects were carried out in different regions of the country. For instance, the village welfare education project at Shiraz University was implemented in Fars Kovar, along with projects by the Social Services Organization in Fars and Tehran, and in Al Shatar, Lorestan.

By 1980, the health and treatment indicators were discouraging. The infant mortality rate stood at 104 per thousand live births, life expectancy was 57 years, and access to clean water and sufficient caloric intake were significantly lower compared to many other countries. However, in the aftermath of the Islamic revolution, the government formulated fundamental policies for health, treatment, and medical education programs. The formation of the first parliamentary government in the middle of 1980 led to the establishment of the Program and Organization Review Council in 1981.

This council, which consisted of several specialized committees, presented its initial report on policies and priorities to the Council of Deputy Ministers in 1982. Despite the imposed war between Iraq and Iran, and despite the heavy bombings of cities, all the necessary rules and relationships required for organizing the components of the network system were explained in detail during the Council of Deputy Ministers meeting. The information was compiled into a book titled “Attitude towards Health, Treatment, and the Training of Medical Manpower” by two diligent experts from the Ministry. This book later became the basis for compiling plans for the expansion of healthcare networks in the country. In this book, the selection of the city as an administrative-geographical scale for the expansion of healthcare networks was emphasized, and with the efforts of these two experts and with the help of the patient and hardworking employees of the provinces, expansion plans were prepared for each city of the country until 1984.

In March 1984, the Islamic Council granted the Ministry of Health a credit equal to 2,500,000,000 Rials to set up a health and treatment network in one city of each province. In order to spend this credit and actually expand the health and treatment networks, the Ministry of Health, Treatment and Medical Education established a unit called the Headquarters for the Development of the Health-Treatment Networks of the country, which continues to operate after many years.

Principles and criteria in the expansion of healthcare networks in Iran

The expansion of the network system in healthcare is guided by several general principles and rules, which are outlined below:

Geographical Access: The aim of ensuring geographical access is to provide all members of society with convenient access to the nearest healthcare unit, regardless of their location. The objective is to limit the maximum distance individuals need to travel to reach a healthcare facility to a one-hour walk. Moreover, healthcare units should be strategically positioned to align with natural patterns of population movement.

Cultural Access: The expansion of healthcare networks should strive to promote inclusivity and minimize ethnic, cultural, and religious conflicts. The objective is to ensure that all designated populations can avail themselves of the services offered by healthcare units in a harmonious manner.

Proportional Resource Allocation: Maintaining a balance between the volume of healthcare services and the availability of trained manpower is crucial. This is important to prevent healthcare providers from being overwhelmed by client demand, while also ensuring that clients do not experience long wait times. Striking an appropriate balance will contribute to controlling service costs as well as preventing service provider unemployment.

Affordable Service Costs: The cost of healthcare services should be designed in a manner that is affordable for individuals, families, and society as a whole. Encouraging people’s active participation, promoting the shared utilization of resources, and harnessing the expertise of multi-professional teams are effective strategies to reduce costs.

Service Leveling: Service leveling refers to the provision of healthcare services in a connected and streamlined manner. This approach significantly reduces the cost of service provision. For instance, in a manufacturing analogy, producing an intricate computer device does not necessarily require thousands of highly skilled engineers. Instead, the process can be simplified and broken down into manageable steps, allowing individuals with appropriate training at each stage to contribute their services efficiently and in a shorter time frame. What is certain is that the design of the service process is the responsibility of the highest specialized ranks. In this way, the heavy costs of education can be reduced. Currently, in the network system, a part of medical science is leveled; the required force is used at each level.

On the other hand, when one of the referrals from the environmental units requires more specialized services, the environmental unit can direct the individual to higher levels of care. For instance, in the fight against malaria, responsibilities at the first level include blood slide preparation, spraying, larvicide application, health education, and patient follow-up. The second level is responsible for slide testing, diagnosis, and treatment initiation, while the third level focuses on epidemiological investigations and environmental improvement.

Currently, in the PHC network system, health centers serve as the first level of service provision in both rural and urban areas, with medical centers occasionally available in cities. It is essential that every population falls within the ambit of the first level, which caters to a specific population. Urban and rural health centers constitute the second level of service provision, while hospitals and specialized polyclinics make up the third level. Some consider academic hospitals offering super-specialized services to be the fourth level.

The delivery of services occurs through a referral system. As highlighted in the section on service provision levels, if the first level encounters cases that require specialized services beyond its capabilities, the unit will refer the client to the second level.

If necessary, the second level will then refer the patient to the third or fourth level for specialized and super-specialized services. This chain of service delivery, starting from the first level and moving to higher levels, is known as the referral system.

Health House

The Health House is a unit primarily located in a village, often covering several other villages known as Qamar villages. Each health center typically serves an average population of 1500 individuals. The health center staff is composed of male and female nurses who play a significant role in ensuring optimal coverage. Key factors for achieving this include the native background of health workers, their constant communication with the community, accurate health information recording, and continuous monitoring of health center activities.

The primary objective of the health center is to provide essential healthcare services to the covered population. The center is responsible for a range of crucial tasks, including:

conducting an annual census of the population within their coverage area;

educating the population and encouraging their active participation in various aspects of healthcare.

C. Providing family health services, such as:

care during pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding;

care for children under five years old;

provision of healthcare for school students:

offering services related to family planning;

administering vaccinations;

conducting home visits to follow up on cases of abandonment or delayed referral.

In addition, the health center performs services related to disease control, which include:

diagnosis of diseases, implementation of prevention standards, and monitoring the treatment of affected cases, such as tuberculosis, leprosy, malaria, among others;

preparation of blood slides from patients suspected of having malaria, monitoring larvicide spraying, and improving the environment to combat disease;

provision of first aid and symptomatic treatment, particularly for specific illnesses like acute respiratory infections and diarrheal diseases.

Furthermore, the health center engages in environmental health activities, such as:

visiting the places of preparation, distribution, storage and sale of food and consumables;

school environment health;

hygiene of the workshop environment;

suggesting basic improvements to the environment;

attention to the collection of solid waste materials and sanitary disposal of waste;

chlorination of drinking water;

participation in the implementation of improvement projects and their maintenance.

In Iran’s service delivery system, the health house serves as an environmental unit managed by community health workers known as health workers. To ensure cultural adherence and efficient service provision, each health house is staffed with both a female nurse and a male nurse. The female nurse primarily oversees internal health house operations, such as client reception, care for covered individuals, vaccination procedures, maintaining vaccination records, providing primary treatment, and administering medication. On the other hand, the male nurse assumes responsibility for tasks outside the health house, including patient follow-up for infectious diseases, diagnosis, environmental health monitoring, and vaccination efforts.

However, it should be noted that this division of responsibilities does not restrict female health workers from considering home visits as part of their core duties, nor does it prevent male health workers from accepting and caring for clients within the health house. Ideally, health workers should be chosen from the same rural area where the health house is located. In cases where this is not possible, individuals from neighboring areas should be considered.

Rural health center

The rural health center is a village-based unit that encompasses one health center located within the same village, as well as multiple health centers from neighboring villages. Within the rural health center, a team composed of doctors, associates, and technicians specializing in family health, disease control, environmental health, oral and dental health, and laboratory work collaboratively. This team, led by a doctor, also includes paramedics and administrative staff.

The primary responsibility of the rural health center is to provide support to health houses, monitor their operations, accept referrals, and establish effective communication with higher-level medical facilities. In addition to their core functions, rural centers are also expected to perform the following tasks:

treating outpatients and individuals referred by health centers;

determining treatment plans for infected cases and providing guidelines for follow-up care in health centers;

monitoring the activities of health centers in the areas of family health, disease prevention, and environmental health;

offering services related to oral and dental health, blood pressure, and diabetes management in selected health centers;

undertaking basic environmental improvements and conducting water sampling;

participating in the implementation and supervision of health projects;

assisting health centers with the procurement of materials, tools, and medications.

Urban health center

The Urban Health Center is a facility located in urban areas, serving an average population of approximately 12,000 individuals. In comparison to rural health centers, urban centers often include additional staff members, such as assistants or radiography technicians. The primary objective of the urban health center is to provide essential healthcare services to the covered population and, when necessary, facilitate patient referrals to hospitals. The center’s responsibilities encompass a wide range of duties, including:

a) Outpatient care: This involves diagnosing illnesses, identifying cases requiring specialized attention or care, and offering health education to patients.

b) Oral hygiene and dental services.

c) Family health: This entails education on health-related matters, such as pre-marriage care, antenatal and postnatal care, breastfeeding guidance, children’s spacing, performing pap smears, and, if necessary, intrauterine device (IUD) placement. The center also takes care of children under the age of five, provides student support, offers specialized care for vulnerable groups like children and mothers, administers vaccinations, conducts home visits to address cases of abandonment or delayed referrals, and provides therapeutic aids.

d) Disease prevention: The center actively promotes health education and implements programs to combat diseases outlined in the national plan. Close monitoring of patients with conditions that require continuous visits and treatment control, such as malaria [20], tuberculosis, and leprosy, is a crucial task [20-23]. Additionally, the center ensures the enforcement of preventive measures concerning environmental cleanliness and the individuals surrounding those affected by infectious diseases. The well-being of students is also an area of focus.

e) Environmental health, food hygiene, and sanitation: Through health education initiatives, the center conducts inspections of public spaces, as well as the preparation, distribution, storage, and sale locations of food and consumables. Regular food and water sampling is carried out to ensure safety standards are met.

The center also monitors the cleanliness of school environments, evaluates the sanitation practices of workshops and factories, measures hazardous factors in work environments, assesses occupational safety factors, paying attention to the sanitary disposal of waste, performing medical diagnostic tests, cooperation in the field of medical manpower training, collecting, sorting, and classifying preliminary investigations and maintaining information and statistics, and preparing reports.

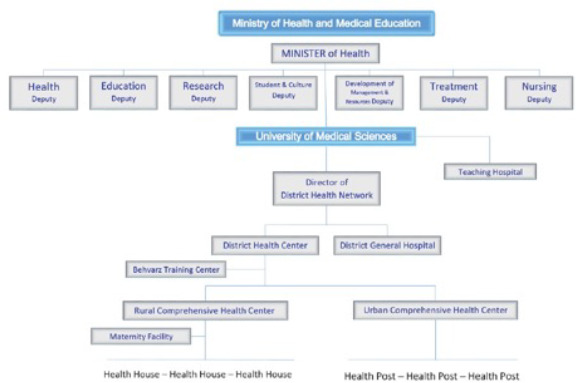

Currently, Iran boasts an extensive network of over 24,000 healthcare facilities, encompassing houses health, urban, and rural health centers. The health system structure in Iran is illustrated in Figure 1 [24].

Iran’s PHC network has made significant strides in healthcare delivery. Firstly, it has vastly improved access to essential health services, particularly in remote and underserved regions, leading to better healthcare equity [25]. Secondly, the PHC network has contributed to a substantial reduction in communicable diseases through widespread vaccination and disease prevention programs. Additionally, it has played a pivotal role in promoting community engagement and health education, fostering a culture of preventive healthcare. Lastly, the network’s emphasis on early detection and treatment has positively impacted health outcomes and life expectancy across the nation. Overall, Iran’s PHC network stands as a model for effective healthcare system development [26].

Conclusions

Iran has made remarkable advancements in the development of its PHC system. By establishing an extensive network of healthcare facilities in both rural and urban areas, the country has successfully enhanced the availability of crucial healthcare services for its citizens.

This expansion has led to improved coverage of preventive care, health education, and fundamental medical treatments. Noteworthy achievements include a decrease in maternal and child mortality rates, increased vaccination rates, and more effective disease prevention initiatives.

The involvement of the community and the integration of traditional medicine have played crucial roles in the success of this expansion. Nevertheless, certain challenges such as disparities in service quality and access between urban and rural regions still persist, demanding continuous efforts to ensure equitable and comprehensive healthcare delivery.

Funding sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for- profit sectors

Informed consent statement

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Authors’ contributions

AR and MB designed the study; MB and MM conceived the study; AR, BDT and MB drafted the manuscript; AR, BDT, MM, MB critically revised the manuscript. AR, SJE, MM performed a search of the literature; furthermore: BDT, SJE: methodology; BDT and SJE: validation and data curation; AR, BDT and SJE: formal analysis; MM and MB final editing. All authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the latest version of the paper for publication.

Figures and tables

Fig. 1.

Health system structure in Iran.

References

- [1].Gharaee H, Azami Aghdash S, Farahbakhsh M, Karamouz M, Nosratnejad S, Tabrizi JS. Public-private partnership in primary health care: an experience from Iran. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2023;24:E5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423622000561 10.1017/S1463423622000561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shahabi S, Kiekens C, Etemadi M, Mojgani P, Teymourlouei AA, Lankarani KB. Integrating rehabilitation services into primary health care: policy options for Iran. BMC Health Serv Res 2022;22:1317. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08695-8 10.1186/s12913-022-08695-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bagheri Z, Dehdari T, Lotfizadeh M. The Preparedness of Primary Health Care Network in terms of Emergency Risk Communication: a study in Iran. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2022;16:1466-75. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.70 10.1017/dmp.2021.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Khatri R, Endalamaw A, Erku D, Wolka E, Nigatu F, Zewdie A, Assefa Y. Continuity and care coordination of primary health care: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2023;23:750. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09718-8 10.1186/s12913-023-09718-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Carneiro Chagas MA, Dos Santos AM, Neves de Jesus N. Nursing care for the transgender population in primary health care: an integrative review. Invest Educ Enferm 2023;41:E07. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.iee.v41n1e07 10.17533/udea.iee.v41n1e07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hanson K, Balabanova D, Brikci N, Erlangga D, Powell-Jackson T. Financing primary health care in low- and middle-income countries: a research and policy agenda. J Health Serv Res Policy 2023;28:1-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01546-X 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01546-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Baker R. Improving life expectancy with primary health care. J Prim Health Care 2023;15:104-5. https://doi.org/10.1071/HC23058 10.1071/HC23058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Alves RFS, Boccolini CS, Baroni LR, Boccolini PMM. Primary health care coverage in Brazil: a dataset from 1998 to 2020. BMC Res Notes 2023;16:63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-023-06323-0 10.1186/s13104-023-06323-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Botes M, Cooke R, Bruce J. Experiences of primary health care practitioners dealing with emergencies – ‘We are on our own’. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2023;15:E1-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v15i1.3553 10.4102/phcfm.v15i1.3553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alzghaibi H, Alharbi AH, Mughal YH, Alwheeb MH, Alhlayl AS. Assessing primary health care readiness for large-scale electronic health record system implementation: Project team perspective. Health Informatics J 2023;29:14604582231152790. https://doi.org/10.1177/14604582231152790 10.1177/14604582231152790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Amihanda R, Odhus CO. Rural health: strengthening primary health care in Kisumu County, Kenya. Rural Remote Health 2023;23:8160. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH8160. 10.22605/RRH8160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Govender I. The role of family medicine and primary health care and its impact on the climate crisis. S Afr Fam Pract 2023;65:E1-2. https://doi.org/10.4102/safp.v65i1.5658 10.4102/safp.v65i1.5658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Freijser L, Annear P, Tenneti N, Gilbert K, Chukwujekwu O, Hazarika I, Mahal A. The role of hospitals in strengthening primary health care in the Western Pacific. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 2023;33:100698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100698 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mei K, Kou R, Bi Y, Liu Y, Huang J, Li W. A study of primary health care service efficiency and its spatial correlation in China. BMC Health Serv Res 2023;23:247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09197-x 10.1186/s12913-023-09197-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Galanakos SP, Bablekos GD, Tzavara C, Karakousis ND, Sigalos E. Primary health care: our experience from an urban primary health care center in Greece. Cureus 2023;15:E35241. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.35241 10.7759/cureus.35241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rezapour R, Dorosti AA, Farahbakhsh M, Azami-Aghdash S, Iranzad I. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary health care utilization: an experience from Iran. BMC Health Serv Res 2022:404. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07753-5 10.1186/s12913-022-07753-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Doshmangir L, Behzadifar M, Shahverdi A, Martini M, Ehsanzadeh SJ, Azari S, Bakhtiari A, Shahabi S, Bragazzi NL, Behzadifar M. Analysis and evolution of health policies in Iran through policy triangle framework during the last thirty years: a systematic review of the historical period from 1994 to 2021. J Prev Med Hyg. 2023. May 16;64:E107-17. https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2023.64.1.2878 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2023.64.1.2878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Moshiri E, Rashidian A, Arab M, Khosravi A. Using an analytical framework to explain the formation of primary health care in Rural Iran in the 1980s. Arch Iran Med 2016;19:16-22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bakhtiari A, Takian A, Ostovar A, Behzadifar M, Mohamadi E, Ramezani M. Developing an organizational capacity assessment tool and capacity-building package for the National Center for Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in Iran. PLoS One 2023;18:E0287743. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0287743 10.1371/journal.pone.0287743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Martini M, Angheben A, Riccardi N, Orsini D. Fifty years after the eradication of Malaria in Italy. The long pathway toward this great goal and the current health risks of imported malaria. Pathog Glob Health 2021;115:215-23. doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2021.1894394 10.1080/20477724.2021.1894394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Canetti D, Riccardi N, Martini M, Villa S, Di Biagio A, Codecasa L, Castagna A, Barberis I, Gazzaniga V, Besozzi G. HIV and tuberculosis: the paradox of dual illnesses and the challenges of their fighting in the history. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2020;122:101921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tube.2020.101921 10.1016/j.tube.2020.101921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Martini M, Besozzi G, Barberis I. The never-ending story of the fight against tuberculosis: from Koch’s bacillus to global control programs. J Prev Med Hyg 2018;59:E241-7. https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2018.59.3.1051 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2018.59.3.1051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Martini M, Gazzaniga V, Behzadifar M, Bragazzi NL, Barberis I. The history of tuberculosis: the social role of sanatoria for the treatment of tuberculosis in Italy between the end of the 19th century and the middle of the 20th. J Prev Med Hyg 2018;59:E323-7. https://doi.org/10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2018.59.4.1103 10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2018.59.4.1103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Doshmangir L, Moshiri E, Farzadfar F. Seven decades of primary healthcare during various development plans in Iran: a historical review. Arch Iran Med 2020;23:338-352. https://doi.org/10.34172/aim.2020.24 10.34172/aim.2020.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lankarani KB, Alavian SM, Peymani P. Health in the Islamic Republic of Iran, challenges and progresses. Med J Islam Repub Iran 2013;27:42-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Behzadifar M, Gorji HA, Rezapour A, Bragazzi NL, Alavian SM. The role of the Primary Healthcare Network in Iran in hepatitis C virus elimination by 2030. J Virus Erad 2018;4:186-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]