Abstract

As an important antiviral target, HIV-1 integrase plays a key role in the viral life cycle, and five integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) have been approved for the treatment of HIV-1 infections so far. However, similar to other clinically used antiviral drugs, resistance-causing mutations have appeared, which have impaired the efficacy of INSTIs. In the current study, to identify novel integrase inhibitors, a set of molecular docking-based virtual screenings were performed, and indole-2-carboxylic acid was developed as a potent INSTI scaffold. Indole-2-carboxylic acid derivative 3 was proved to effectively inhibit the strand transfer of HIV-1 integrase, and binding conformation analysis showed that the indole core and C2 carboxyl group obviously chelated the two Mg2+ ions within the active site of integrase. Further structural optimizations on compound 3 provided the derivative 20a, which markedly increased the integrase inhibitory effect, with an IC50 value of 0.13 μM. Binding mode analysis revealed that the introduction of a long branch on C3 of the indole core improved the interaction with the hydrophobic cavity near the active site of integrase, indicating that indole-2-carboxylic acid is a promising scaffold for the development of integrase inhibitors.

Keywords: HIV-1 integrase, design and synthesis, indole-2-carboxylic acid, virtual screening, structural optimization

1. Introduction

The high morbidity and mortality associated with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), which is caused by human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1), make this pandemic a major global public health problem [1,2,3]. HIV-1 integrase plays a critical role in viral replication, inserting the double-stranded viral DNA, generated from reverse transcription, into the host genome [4,5], thus leading to the establishment of proviral latency [6]. As an important protein in viral infection, integrase is a particularly attractive antiviral target because there is no host cellular counterpart, and specific integrase inhibitors would not interfere with cellular functions [7]. In addition, since integrases use the same active site (DDE motif) for both the 3′-processing and DNA strand transfer steps, inhibitors targeting integrase benefit from a potentially high genetic barrier to resistance selection [8]. Therefore, extensive efforts have been made to identify effective integrase inhibitors with diverse chemical features [9,10,11,12].

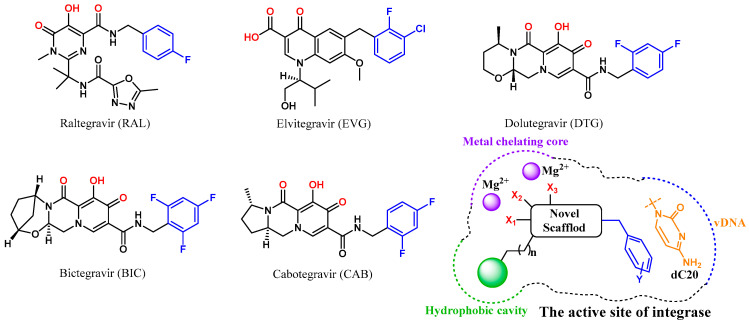

A diketo acid moiety was believed to be essential for the development of integrase inhibitors [13,14,15], and, so far, five integrase antagonists have been approved for clinical use: raltegravir (RAL, Figure 1) [16], elvitegravir (ELV) [17], dolutegravir (DTG) [18], bictegravir (BIC) [19] and cabotegravir (CAB) [20]. All these integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) effectively inhibit the integration of DNA catalyzed by integrase [21,22]. However, drug resistance mutations inevitably emerged during the antiviral therapy and impaired the susceptibility of the virus to the first-generation inhibitors (RAL and ELV) [19,23,24]. The use of the three-ring system in second-generation inhibitors (DTG, BIC and CAB) enhanced the potency against some but not all RAL/EVG resistant HIV variants [25,26]. Therefore, the development of new integrase inhibitors with novel structural scaffolds is still an important research topic.

Figure 1.

Structure of HIV-1 integrase antagonists and design strategy of new integrase inhibitors. The metal chelating heteroatoms and halogenated phenyl groups interacting with dC20 are colored in red and blue, respectively.

Since the high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures of HIV intasome were reported, the mode of action of advanced INSTIs has been well analyzed, including a chelating core with two Mg2+ of integrase and a π-stacking interaction with 3′ terminal adenosine of processed vDNA (dC20) [27,28]. It should be noted that a hydrophobic cavity near the β4-α2 connector was formed by the sidechain of Tyr143 branch and the backbone of Asn117, which is close to the active site of integrase [10,27]. Although the three-ring system associated with the second-generation inhibitors DTG and BIC extended to the location, substantial free space was still observed in this cavity. Thus, improving the interaction with the hydrophobic site might increase the antiviral effects of INSTIs and delay the emergence of drug-resistant mutations.

Herein, a structure-based virtual screening was carried out to find novel chemical scaffolds chelating two Mg2+ cofactors within the active site of integrase (Figure 1). Halogenated phenyls were then added to the chemical structure to form a π-π stacking interaction with dC20, as in previous research [29]. Most importantly, to fill the space in the hydrophobic cavity, a bulky hydrophobic pharmacophore was then introduced to the core of the optimized structure through a linker. Sequentially, structural optimizations were performed to complete SAR study. Through these efforts, potent and effective INSTIs were developed, and the binding mode of the hydrophobic site was also analyzed.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Molecular Docking-Based Virtual Screening

As a rapid and flexible docking module, LibDock was developed as a site feature algorithm for docking small molecules into an active receptor site [30,31], which has been proved to be an effective tool for the discovery of potential chemical entities [32,33,34]. In order to develop potent HIV-1 integrase inhibitors, LibDock-based virtual screening was conducted to find potent INSTIs in this study. The Chemdiv and Specs databases, which include 1.75 million compounds, were selected to be docked into the crystal structure of HIV-1 integrase (PDB ID: 6PUY), and the location of the original substrate (4d) was designated as the docking site [28]. After being sorted by LibDock score in Discovery Studio 3.1, the 175 compounds with highest docking scores were retained. Furthermore, to eliminate molecules with poor drug-like properties, all the selected compounds were then filtered using Lipinski’s rules [35], providing a total of 168 compounds (listed in Supporting Information Table S1).

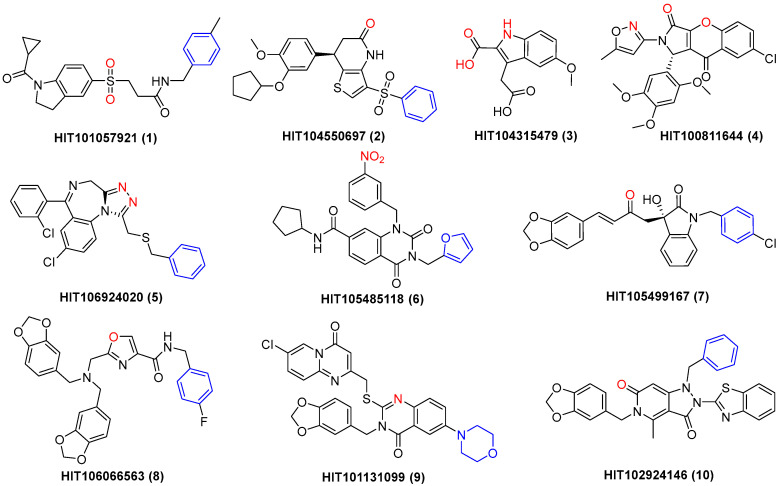

Subsequently, the Autodock Vina program was used to investigate the binding energy of the above 168 compounds with HIV-1 integrase, and the 25 compounds with the lowest binding energy (Table S2) were selected. Chelating with the metal ions of integrase is critical for INSTIs [27,36], and compounds with obvious metal chelating properties and novel structural scaffolds were retained. Therefore, a total of 10 compounds (1–10, Figure 2) were finally left, and the binding modes of these complexes are depicted in Figure S1. The binding results revealed that all these compounds effectively bound with the active site of HIV-1 integrase, with binding energy lower than −12.9 kcal/mol (Table 1). Meanwhile, for most of the compounds (1–5 and 10), the energy needed for the most frequent conformation also manifested in the lowest energy, indicating the reliability of molecular docking results. Specifically, obvious metal-chelating interactions were observed for all 10 compounds, and π-π stacking interactions were formed with dC20 by eight of them (except 3 and 4, Figure S1). Thus, these compounds were further evaluated for their inhibitory effect against HIV-1 integrase.

Figure 2.

Structure of 10 compounds (1–10) chelating with the magnesium ions of HIV-1 integrase. The metal chelating heteroatoms are in red, and phenyl groups interacting with dC20 are shown in blue.

Table 1.

Binding energies and HIV-1 integrase inhibitory effect of 10 compounds from virtual screening.

| Compd. | HIT ID | m.p. (°C) a | Lowest Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Highest Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | Most Binding Energy (kcal/mol) | IC50 (μM) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | HIT101057921 | 173.4–175.3 | −15.8 | −11.4 | −15.8 | 39.06 ± 1.21 |

| 2 | HIT104550697 | 113.0–116.7 | −15.3 | −11.3 | −15.3 | 33.01 ± 1.29 |

| 3 | HIT104315479 | 159.7–163.2 | −15.1 | −14.5 | −15.1 | 12.41 ± 0.07 |

| 4 | HIT100811644 | 271.4–279.0 | −13.4 | −11.0 | −13.4 | 18.52 ± 1.06 |

| 5 | HIT106924020 | 164.7–167.8 | −13.2 | −8.8 | −13.2 | 47.44 ± 1.45 |

| 6 | HIT105485118 | 235.3–241.2 | −13.2 | −11.7 | −13.1 | 22.63 ± 0.58 |

| 7 | HIT105499167 | 147.0–148.2 | −13.2 | −9.4 | −11.9 | 21.45 ± 0.26 |

| 8 | HIT106066563 | 171.5–176.8 | −13.1 | −8.5 | −12.7 | 28.16 ± 1.07 |

| 9 | HIT101131099 | 239.0–240.1 | −13.1 | −9.7 | −11.7 | 32.75 ± 0.83 |

| 10 | HIT102924146 | 139.9–143.6 | −12.9 | −11.4 | −12.9 | 22.25 ± 0.43 |

| RAL | - c | 154.3–157.9 | −13.6 | −8.9 | −12.0 | 0.08 ± 0.04 |

a Melting point. b Concentration required to inhibit the in vitro strand-transfer step of integrase by 50%. IC50 values are average for three independent experiments. c Not applicable.

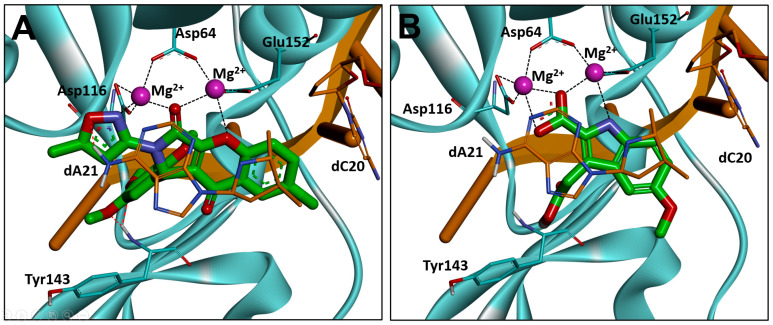

2.2. Evaluation of Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitory Effect

DNA strand transfer is essential for viral replication, and all the clinically used HIV integrase antagonists are INSTIs [37]. Thus, the integrase strand transfer-inhibitory activity was tested for the above 10 compounds using an HIV-1 integrase assay kit, and RAL was used as the positive control [38,39] (Table 1). The results showed that all the molecules clearly inhibited the strand transfer of HIV-1 integrase with IC50s from 12.41–47.44 μM, suggesting the effective hit rates of the former virtual screening. Among them, compounds 3 and 4 manifested the highest integrase inhibition activity, with IC50s of 12.41 and 18.52 μM, respectively. Interestingly, all the clinically used INSTIs effectively interacted with dC20 through a π-π stacking effect; however, this interaction was not observed for compounds 3 and 4, demonstrating the potential for further optimizations. Through analyzing the binding mode of the two compounds, it was found that a bis-bidentate chelation of the Mg2+ ions was established for the chromeno core and 2-isoxazole of 4, and a π-π stacking interaction with dA21 was also found (Figure 3A). For compound 3, a chelating triad motif was found between the indole-2-carboxylic acid scaffold and the two metals within the active site, and a hydrophobic interaction was observed between the indole core and dA21 (Figure 3B). Moreover, the C3 carboxyl group extended to the hydrophobic cavity near the β4-α2 connector, indicating that a structural modification in this position might improve the antiviral activity. Considering the pronounced antiviral activity and potential of the core structure, compound 3 was selected for further optimizations.

Figure 3.

Binding modes of compounds 4 (A) and 3 (B) with HIV-1 integrase (PDB ID: 6PUY). HIV-1 integrase is displayed in cyan, the 3′ end of the viral DNA (dA21 and dC20) is shown in stick representation in orange, and the chelate bond is represented with dashed line in black.

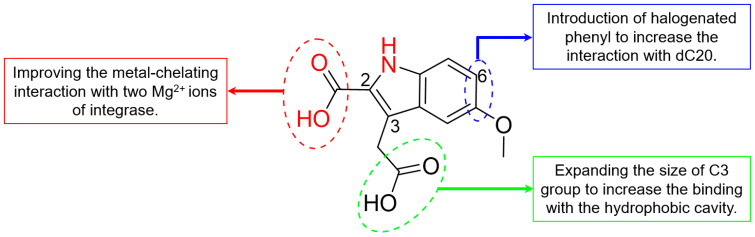

2.3. Optimization Strategies

Through comparing the binding conformation of compound 3 and the second-generation HIV-1 integrase inhibitors [27,40], we speculated that a π-stacking interaction with viral DNA would be formed through the addition of a halogenated phenyl to C6 of the indole core of compound 3 (Figure 4). Meanwhile, we speculated that modifications of the C2 carboxyl group will also be carried out to improve the chelation with metal ions of the intasome core. Most importantly, to enhance the antiviral effect of INSTIs and delay the emergence of drug-resistant mutations, interactions with the hydrophobic cavity near the integrase active site will then be investigated [10,27]. Thus, the length and size of the C3 substituent will be modified to improve the interaction with the backbone residues that form the hydrophobic pocket, such as Tyr143 and Asn117.

Figure 4.

Optimization strategies of compound 3.

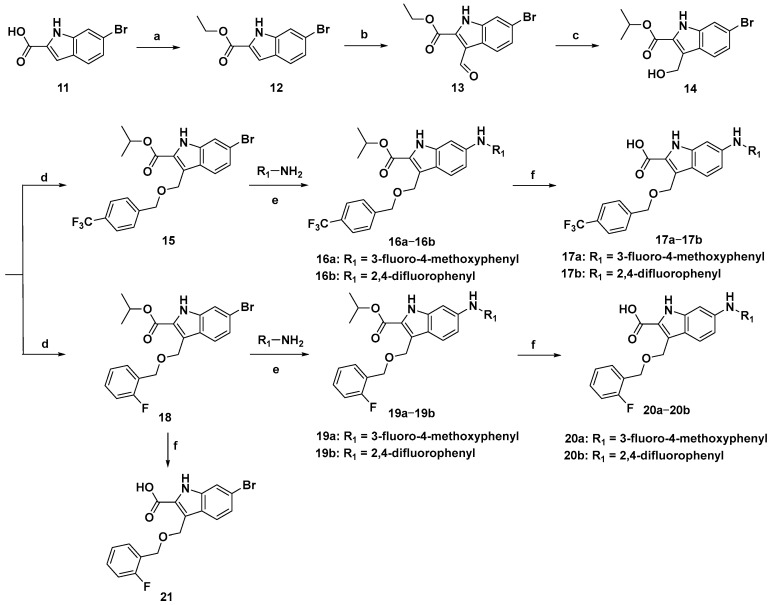

2.4. Synthesis route of Compound 3 Derivatives

To facilitate the introduction of halogenated phenyl groups at the C6 position of the indole core, 6-bromoindole-2-carboxylic acid (11) was used as the initial material, and the synthetic route is described in Scheme 1. The carboxyl group of 11 was esterificated to produce compound 12 in the presence of concentrated sulfuric acid. Due to the electron absorption effect of the C2 carbonyl group, a formyl group was introduced at the C3 position through the Vilsmeier–Haack reaction to provide a high yield of compound 13 (87%), which was then selectively reduced to hydroxymethyl (14) by using isopropanolic aluminium in the Meerwein–Ponndorf–Verley reaction. Interestingly, an ester-exchange product (14) was detected under this condition. Sequentially, compound 14 was condensed with p-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl alcohol and o-fluorobenzyl alcohol to provide compounds 15 and 18 under alkaline conditions, respectively. For compound 15, 3-fluoro-4-methoxyphenyl and 2,4-difluorophenyl were introduced at C6 via the Buchwald–Hartwig reaction catalyzed by palladium acetate to offer compounds 16a and 16b, which were then hydrolyzed to produce 17a and 17b, respectively. Similarly, halogenated phenyls were added to the C6 of compound 18 to provide 19a and 19b as well, which were further hydrolyzed to provide 20a and 20b in the presence of alkaline conditions, respectively.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic route of compound 3 derivatives. Reagents and conditions: (a) concentrated H2SO4, EtOH, 80 °C, 2 h, 65%; (b) POCl3, DMF, rt-50 °C, 4 h, 87%; (c) Al(O-i-Pr)3, i-PrOH, 60 °C, 5 h, 85%; (d) p-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl alcohol or o-fluorobenzyl alcohol, K2CO3, DMF, rt, 3–5 h, 89–93%; (e) Pd(OAc)2, Cs2CO3, Xphos, 1,4-dioxane, 100 °C, 2–4 h, 68–85%; (f) NaOH, MeOH/H2O (3:1 v/v), 80 °C, 1.5 h, 45–52%.

2.5. Evaluation of Biological Activity

The inhibitory effect of compound 3 derivatives against integrase strand transfer was then evaluated. As shown in Table 2, all the synthesized compounds exhibited better integrase inhibitory activities than the parent compound, with IC50s from 0.13 to 6.85 μM. Encouragingly, the introduction of long-chain p-trifluorophenyl (15) or o-fluorophenyl (18) at the C3 position of the indole core indeed significantly improved the activity by 5.3-fold and 6.5-fold, respectively. Meanwhile, the addition of halogenated anilines at the C6 position (16b, 19a and 19b) markedly improved the integrase inhibition effect, with IC50s of 1.05–1.70 μM, probably due to the formation of π-π stacking with viral DNA. Moreover, further hydrolysis of the carboxylate of 16a, 16b, 19a and 19b resulted in clear enhancements in activity. This was especially clear for compounds 17b, 20a and 20b, as the IC50 values were 0.39, 0.13 and 0.64 μM, respectively. The remarkable improvement in inhibition was probably due to the increase in the bis-bidentate chelation between the Mg2+ ions and the free carboxyl group. Among them, the inhibitory effect of 20a was close to that of the positive control RAL (0.06 μM).

Table 2.

HIV-1 integrase inhibitory effect and cytotoxicity of compound 3 derivatives.

| Compd. | IC50 (μM) | CC50 (μM) a | Compd. | IC50 (μM) | CC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 2.34 ± 0.31 | >80 | 19a | 1.05 ± 0.32 | 37.58 ± 3.64 |

| 16a | 3.47 ± 0.82 | >80 | 19b | 1.70 ± 0.15 | 29.37 ± 1.76 |

| 16b | 1.06 ± 0.25 | >80 | 20a | 0.13 ± 0.02 | >80 |

| 17a | 0.93 ± 0.07 | >80 | 20b | 0.64 ± 0.06 | >80 |

| 17b | 0.39 ± 0.09 | >80 | 21 | 6.85 ± 0.66 | >80 |

| 18 | 1.92 ± 0.07 | 45.29 ± 2.73 | RAL | 0.06 ± 0.04 | >80 |

a Concentration that inhibits the proliferation of MT-4 cells by 50%. All data values are the average of at least three independent experiments.

On the other hand, the toxicity of the synthesized compounds to the MT-4 human T-cell line was also assessed (Table 2). The results revealed that no toxicity was observed for most of the compounds at 80 μM except for 18, 19a and 19b, and the CC50 values of these three compounds were all higher than 29 μM, indicating lower toxicities.

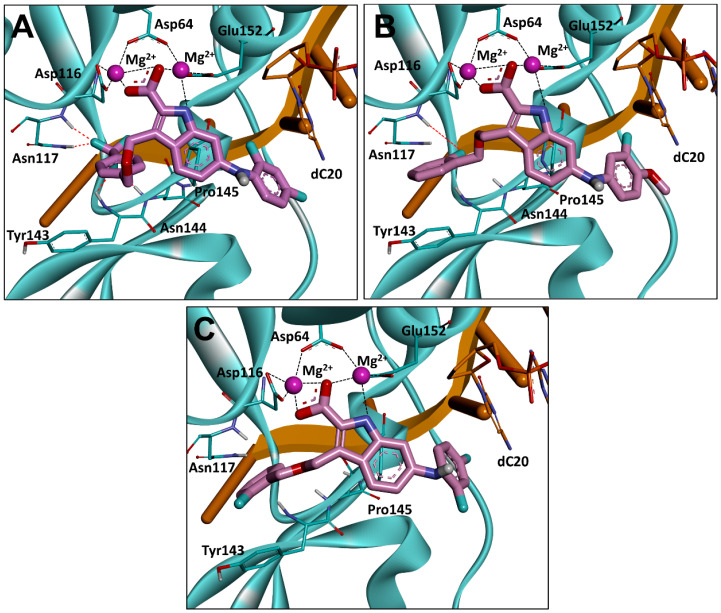

2.6. Binding Mode Analysis

To better understand the structure–activity relationship, the three compounds with best integrase inhibitory effect (17b, 20a and 20b) were selected and further studied for their binding modes with HIV-1 integrase using molecular docking (Figure 5). The results revealed that compounds 17b, 20a and 20b bound to the integrase in a similar binding conformation. Specifically, three central electronegative heteroatoms were observed to chelate with two Mg2+ cofactors within the active site, indicating a strong metal-chelating cluster between the C2 carboxyl indole with the integrase. Furthermore, in agreement with the previous design, π-π stacking interactions were also found in the introduced C6 halogenated benzene with dC20, which increased the binding force with the integrase.

Figure 5.

Binding modes of compounds 17b (A), 20a (B) and 20b (C) with HIV-1 integrase. HIV-1 integrase is displayed in cyan, the 3′ end of the viral DNA (dC20) is shown in stick representation in orange, and the chelate bond is represented with dashed line in black. dA21 and all water molecules are omitted for clarity.

The reason for the difference in activity of compounds 17b, 20a and 20b was then investigated, and it was decided that this was probably because of the long branches at the C3 position of the indole core that extended to the hydrophobic cavity formed by the sidechain of Tyr143 branch and the backbone of Asn117 [10,27]. Compared with compound 3, two hydrogen bonds were observed between the trifluoromethyl group of 17b and Asn117 (Figure 5A), which might contribute to the significant enhancement in the integrase-inhibitory effect. For compound 20a, a similar H-bond was also found (Figure 5B). Moreover, a critical π-π stacking interaction was formed between the benzene of the C3 branch and Tyr143, resulting in an improvement in activity. In contrast, although the above π-π stacking interaction was partially retained in compound 20b, the H-bond with Asn117 disappeared because of a 180° flip in the benzene of the C3 branch, leading to the decline in activity (Figure 5C).

3. Conclusions

In summary, to identify new HIV-1 integrase inhibitors, a set of molecular docking-based virtual screenings were carried out, and 10 molecules were chosen for biological activity study, which obviously inhibited the strand transfer of integrase. Among these compounds, a chelating core with two Mg2+ of integrase was observed in the indole core and the C2 carboxyl group of compound 3. Through optimizations at C2, C3 and C6 of the indole core of compound 3, a series of indole-2-carboxylic acid derivatives were designed and synthesized, and the biological results showed that all synthesized compounds markedly improved the inhibitory effect against integrase. Furthermore, the structure–activity relationship revealed that introducing C6-halogenated benzene and the C3 long branch to the indole core indeed increased the inhibitory activity against HIV-1 integrase. Through the above structural modifications, compound 20a was finally developed, which significantly inhibited the strand transfer of integrase with IC50 of 0.13 μM. Binding mode analysis suggested that the C3 long branch of 20a extended to the hydrophobic cavity near the integrase active and interacted with Tyr143 and Asn117. The above results demonstrated the potential of indole-2-carboxylic acid derivative 20a as a novel HIV-1 INSTI.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. General Methods and Materials

All analytical grade reagents and chemicals were purchased from commercial suppliers. Column chromatography was performed on silica gel (Qingdao, 300–400 mesh) using the indicated eluents. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a JEOL spectrometer (400 MHz) using CDCl3, CD3OD or DMSO-d6 as solvents with the internal standard of tetramethylsilane. HRMS was recorded on a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Plus Orbitrap LC-MS/MS. All prepared compounds were purified to >96% purity as determined by HPLC (Dionex Ultimate 3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) analysis using the following methods. Purity analysis of final compounds was performed through a SuperLu C18 (particle size = 5 μm, pore size = 4.6 nm, dimensions = 250 mm) column. The injection volume was 10 μL, the mobile phase consisted of methyl alcohol and water (80:20) with a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and each analysis lasted for 20 min. The detection wavelength was 280 nm. The retention time of each compound (RT,HPLC) was displayed in the analytical data of the respective compounds. All melting points were obtained with a WRS-2 microcomputer melting point apparatus.

4.2. LibDock Based Virtual Screening

LibDock based virtual screening was used to identify potential HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. The X-ray crystal structure of HIV-1 integrase (PDB ID: 6PUY [28]) was downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org, accessed on 16 December 2022). Then, 1.75 million compounds from the Chemdiv and Specs databases were docked into the crystal structure of integrase using the LibDock module in the Discovery Studio software (3.1); the location of the ligand (4d) was selected as the binding site, 50 conformations were generated for each molecule and the other parameters were set to default. The 175 compounds (1/10,000) with the highest LibDock scores were retained, which were then filtered using the ‘Lipinski’s rule of five’ [41] in Discovery Studio.

4.3. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking of 168 compounds with drug-like property was conducted using Autodock Vina to predict the binding affinity as well as binding modes of the compounds with integrase. The location of the ligand (4d) was used as the binding site with a central coordinate in the X (141.136), Y (159.768), and Z directions (179.84). All the rotatable bonds in the ligands were allowed to rotate freely, and 100 conformations were generated for each molecule. After docking, the best conformation of each ligand was selected and the corresponding score of the ligand was ranked to find the compounds with the highest score. The top 25 compounds with the highest scores were selected for PAINS remover and manual analysis.

4.4. PAINS Remover

False-positive problems might occur during the virtual screening, and PAINS (Pan Assay Interference Compounds) is a compound that interferes with most tests. To avoid the possible false-positive problems in subsequent biological tests, PAINS remover (https://www.cbligand.org/PAINS/, accessed on 2 February 2023) was used to remove the possible PAINS molecule [42].

4.5. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 12–21

4.5.1. Synthesis of Ethyl 6-bromo-1H-indole-2-carboxylate (12)

6-bromo-1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid (100 mg, 0.42 mmol) was dissolved in alcohol (10 mL), and concentrated sulfuric acid (20 mg, 0.21 mmol) was added dropwise to the solution. The mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 2 h (monitored by TLC). The reaction was quenched with a saturated aqueous solution of sodium bicarbonate and extracted with ethyl acetate (30 mL × 3). The combined organic phase was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate before vacuum suction filtration. The crude product was chromatographed on silica gel (1:5 v/v ethyl acetate/petroleum ether) to afford a white solid (91 mg, 82%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3), δ 9.19 (br, 1H), 7.60 (s, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.24 (s, 1H), 7.19 (s, 1H), 4.43 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.43 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.81, 137.38, 128.07, 126.27, 124.37, 123.81, 119.07, 114.77, 108.62, 61.29, 14.38. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C11H10BrNO2 for [M − H]− 265.9817, 267.9796; found 265.9822, 267.9798. RT,HPLC = 12.51 min.

4.5.2. Synthesis of Ethyl 6-bromo-3-formyl-1H-indole-2-carboxylate (13)

Phosphorus oxychloride (572 mg, 3.73 mmol) was added dropwise to a solution of compound 12 (100 mg, 0.37 mmol) in DMF (10 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h and sequentially heated under reflux for 2 h (monitored by TLC). The solution was cooled to room temperature, brought to pH8 by adding anhydrous sodium carbonate, extracted with ethyl acetate (30 mL × 3) and concentrated under reduced pressure to afford the crude product. The residue was applied to silica gel column chromatography (1:4 v/v ethyl acetate/petroleum ether) to provide a white solid (96 mg, 87%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.82 (s, 1H), 10.58 (s, 1H), 8.17 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.72 (s, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 4.47 (q, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 1.41 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 187.92, 160.44, 137.09, 133.86, 127.02, 124.69, 124.23, 119.11, 118.87, 116.15, 62.53, 14.58. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C12H10BrNO3 for [M − H]− 293.9766, 295.9746; found 293.9822, 295.9795. RT,HPLC = 8.37 min.

4.5.3. Synthesis of Isopropyl 6-bromo-3-(hydroxymethyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylate (14)

The synthesized intermediate 13 (100 mg, 0.34 mmol) and aluminum isopropoxide (207 mg, 1.01 mmol) were dissolved in isopropanol (15 mL) and stirred at 60 °C for 5 h (monitored by TLC). After removal of isopropanol using a rotary evaporator, the reaction mixture was applied to silica gel column chromatography (1:5 v/v ethyl acetate/petroleum ether) to provide a white solid (82 mg, 85%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.59 (s, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (s, 1H), 7.18 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 5.21–5.14 (m, 1H), 4.97 (s, 2H), 4.86 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 1.36 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 187.92, 160.44, 137.09, 133.86, 127.02, 124.69, 124.23, 119.11, 118.87, 116.15, 62.53, 14.58. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C13H14BrNO3 for [M − H]− 310.0079, 312.0059; found 310.0086, 312.0061. RT,HPLC = 12.93 min.

4.5.4. Synthesis of Isopropyl 6-bromo-3-(((4-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)oxy)methyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylate (15)

Compound 14 (100 mg, 0.32 mmol), 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl bromide (76 mg, 0.32 mmol) and potassium carbonate (133 mg, 0.96 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (10 mL). The solution was stirred at room temperature for 5 h (monitored by TLC). After the addition of 5 mL of water, the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (30 mL × 3), concentrated under reduced pressure to provide the crude product and applied to silica gel column chromatography (1:5 v/v ethyl acetate/petroleum ether) to afford liquid-oily products (133 mg, 93%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.95 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 5.86 (s, 2H), 5.08 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 5.00 (s, 2H), 1.20 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.36, 143.86, 139.30, 127.18, 125.93, 125.89, 125.66, 125.60, 125.40, 124.56, 124.06, 119.13, 114.00, 69.19, 55.71, 47.90, 21.92. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C21H19BrF3NO3 for [M + Na]+ 492.0398, 494.0378; found 492.0389. 494.0364. The same procedure was also followed for the synthesis of 18.

4.5.5. Synthesis of Isopropyl 6-((3-fluoro-4-methoxyphenyl)amino)-3-(((4-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl) oxy)methyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylate (16a)

3-Fluoro-4-methoxyaniline (60 mg, 0.43 mmol), palladium(II) acetate (14 mg, 0.06 mmol), cesium carbonate (88 mg, 0.64 mmol) and 2-(dicyclohexylphosphino)-2′,4′,6′-tri-i-propyl-1,1′-biphenyl (69 mg, 0.13 mmol) were added to a solution of compound 15 (100 mg, 0.21 mmol) in 1,4-dioxane (30 mL) under the protection of nitrogen. The mixture was stirred at 100 °C for 2 h and monitored by TLC. Upon completion, the solution was concentrated under reduced pressure to provide the crude product, which was purified with silica gel chromatography (1:5 v/v ethyl acetate/petroleum ether) to afford a white solid (104 mg, 80%). mp 142.3–145.6 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (t, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 6.90 (s, 1H), 6.88–6.83 (m, 1H), 6.80–6.76 (m, 1H), 5.74 (s, 2H), 5.12–5.06 (m, 1H), 4.97 (s, 2H), 4.81 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 1.24 (d, J = 6.0 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.75, 153.74, 151.33, 144.23, 142.91, 141.46, 141.35, 140.00, 138.03, 137.95, 128.37, 128.05, 127.37, 126.32, 125.90, 125.86, 123.70, 123.13, 120.90, 115.88, 113.95, 113.82, 113.79, 106.46, 106.25, 95.76, 68.44, 57.12, 56.05, 47.75, 22.10. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C28H26F4N2O4 for [M − H]− 529.1829; found 529.1761. RT,HPLC = 13.01 min. The same procedure was also followed for the synthesis of 16b, 19a and 19b.

4.5.6. Isopropyl 6-((2,4-difluorophenyl)amino)-3-(((4-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)oxy) methyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylate (16b)

White solid, 85% yield. mp 149.7–152.5 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.04 (s, 1H), 7.83 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.29–7.18 (m, 4H), 6.94(t, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H) 6.85(d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.80 (s, 1H), 5.72 (s, 2H), 5.11–5.05 (m, 1H), 4.97 (t, J = 3.6 Hz, 2H), 1.23 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.73, 144.19, 143.25, 139.99, 128.36, 128.04, 127.38, 126.32, 125.87, 123.49, 123.18, 122.34, 120.99, 113.50, 111.83, 111.61, 105.27, 105.04, 104.77, 96.01, 68.44, 56.01, 47.77, 22.07. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C27H23F5N2O3 for [M + Na]+ 541.1527; found 541.1504. RT,HPLC = 16.74 min.

4.5.7. Synthesis of 6-((3-fluoro-4-methoxyphenyl)amino)-3-(((4-(trifluoromethyl) benzyl)oxy)methyl) -1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid (17a)

Sodium hydroxide (28 mg, 0.71 mmol) was added to a solution of 15 (100 mg, 0.24 mmol) in mixed solution of methanol and water (4 mL, 3:1 methanol/water), and the reaction was stirred at 80 °C for 1.5 h. The mixture was then cooled to room temperature, brought to a pH of 6 by adding acetic acid, extracted with ethyl acetate (15 mL × 3) and concentrated under reduced pressure to provide the crude product. The residue was purified with silica gel chromatography (1:2 v/v ethyl acetate/petroleum ether) to afford a yellow solid (44 mg, 45%). mp 134.8–136.3 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.12 (s, 1H), 7.69–7.65 (m, 3H), 7.21 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.00–6.95 (m, 1H), 6.89–6.73 (m, 4H), 5.81 (s, 2H), 4.92 (S, 2H), 3.77 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 163.67, 144.25, 142.74, 141.41, 141.31, 139.75, 138.06, 137.96, 127.41, 125.95, 125.91, 123.04, 121.42, 121.10, 114.24, 113.73, 113.70, 106.37, 106.16, 96.01, 66.03, 57.81, 57.13. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C25H20F4N2O4 for [M − H]− 487.1359; found 487.1303. RT,HPLC = 7.34 min. The same procedure was also followed for the synthesis of 17b, 20a, 20b and 21.

4.5.8. 6-((2,4-difluorophenyl)amino)-3-(((4-(trifluoromethyl)benzyl)oxy)methyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid (17b)

Yellow solid, 50% yield. mp 157.3–160.5 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.66 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 7.22 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 3H), 7.17–7.11(m, 1H), 6.9–6.78 (m, 3H), 5.88 (s, 2H), 4.87 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.63, 165.09, 157.68, 155.41, 155.30, 152.72, 144.83, 141.52, 138.66, 128.77, 128.62, 128.05, 127.73, 127.61, 126.18, 125.82, 125.78, 123.48, 122.15, 120.96, 113.24, 111.71, 111.49, 105.24, 105.00, 104.73, 97.10, 55.68, 47.13. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C24H17F5N2O3 for [M − H]− 475.1159; found 475.1175. RT,HPLC = 13.94 min.

4.5.9. Isopropyl 6-bromo-3-(((2-fluorobenzyl)oxy)methyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylate (18)

White solid, 89% yield. mp 154.6–158.9 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.93 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.86 (s, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.22–7.18 (m, 1H), 7.03 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.49 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.80 (s, 2H), 5.12–5.05 (m, 1H), 4.98 (s, 2H), 1.20 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.36, 143.86, 139.30, 127.18, 125.93, 125.89, 125.62, 125.60, 125.40, 124.56, 124.06, 123.38, 119.13, 114.00, 69.19, 55.71, 47.90, 21.92. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C20H19BrFNO3 for [M + Na]+ 442.0430, 444.0410; found 442.0438, 444.0415. RT,HPLC = 15.44 min.

4.5.10. Isopropyl 6-((3-fluoro-4-methoxyphenyl)amino)-3-(((2-fluorobenzyl)oxy) methyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylate (19a)

White solid, 79% yield. mp 141.2–144.5 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.14 (s, 1H), 7.81 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.31–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.19 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H) 7.07–7.00 (m,2H), 6.94 (s, 1H), 6.89–6.79 (m, 3H), 6.64 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.70 (s, 2H), 5.13–5.06 (m,1H), 4.97 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 4.80 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 1.24 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.71, 161.19, 158.76, 153.77, 151.35, 142.93, 141.48, 141.37, 140.07, 137.92, 129.51, 129.43, 128.39, 128.34, 126.32, 126.11, 125.97, 125.01, 123.62, 123.24, 120.81, 115.81, 115.60, 113.88, 106.58, 106.38, 95.46, 68.36, 57.17, 55.99, 22.06. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C27H26F2N2O4 for [M + Na]+: 503.1758; found: 503.1766. RT,HPLC = 6.33 min, purity > 99%.

4.5.11. Isopropyl 6-((2,4-difluorophenyl)amino)-3-(((2-fluorobenzyl)oxy)methyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylate (19b)

White solid, 68% yield. mp 171.8–175.3 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.89 (s, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.28–7.17 (m, 4H), 7.04 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.95 (t, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 6.85–6.80 (m, 2H), 6.61 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.66 (s, 2H), 5.12–5.06 (m, 1H), 4.97 (d, J = 5.6 Hz, 2H), 4.80 (t, J = 5.6 Hz, 1H), 1.23 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 161.70, 161.18, 158.75, 143.26, 140.02, 129.49, 129.41, 128.36, 128.32, 126.30, 126.09, 125.94, 125.00, 123.42, 123.29, 120.88, 115.78, 115.57, 113.44, 111.85, 111.64, 105.30, 105.04, 104.80, 95.70, 68.38, 55.97, 22.04. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C26H23F3N2O3 for [M + Na]+: 491.1558; found 491.1538. RT,HPLC = 7.32 min.

4.5.12. 6-((3-fluoro-4-methoxyphenyl)amino)-3-(((2-fluorobenzyl)oxy)methyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid (20a)

Yellow solid, 47% yield. mp 169.9–173.7 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.13 (s, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.17 (m, 2H), 7.07–7.00 (m, 2H), 6.91 (s, 1H), 6.86–6.78 (m, 3H), 6.64 (s, 1H), 5.76 (s, 2H), 4.97 (s, 2H), 3.78 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 163.76, 161.22, 158.79, 153.77, 151.35, 142.71, 141.41, 141.30, 139.91, 138.10, 138.02, 128.51, 128.47, 126.17, 126.03, 125.84, 125.00, 123.76, 123.42, 120.85, 115.94, 113.75, 106.44, 106.24, 95.60, 57.19, 55.89. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C24H20F2N2O4 for [M − H]−: 437.1391; found 437.1301. RT,HPLC = 9.81 min.

4.5.13. 6-((2,4-difluorophenyl)amino)-3-(((2-fluorobenzyl)oxy)methyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid (20b)

Yellow solid, 52% yield. mp 178.5–181.8 °C; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3OD) δ 7.71 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.23–7.13 (m, 2H), 7.10–7.04 (m, 1H), 6.98–6.94 (m, 2H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 6.88 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.81–6.77 (m, 2H), 6.63 (t, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 5.79 (s, 2H), 5.09 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD3OD) δ 162.60, 160.17, 144.21, 141.06, 129.88, 129.80, 129.24, 129.20, 127.12, 126.98, 125.53, 125.39, 125.35, 122.90, 122.10, 116.13, 115.92, 114.82, 111.96, 111.74, 105.40, 105.13, 104.89, 96.85, 56.44, 42.42. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C23H17F3N2O3 for [M − H]−: 425.1191; found 425.1117. RT,HPLC = 13.12 min.

4.5.14. 6-bromo-3-(((2-fluorobenzyl)oxy)methyl)-1H-indole-2-carboxylic acid (21)

White solid, 48% yield. mp 174.3–178.0 °C, 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.91 (d, J = 8.8 Hz 1H), 7.86 (d, J = 1.6 Hz 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 8.8 Hz 2H), 7.24–7.19 (m, 1H), 7.01 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.44 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.86 (s, 2H), 4.98 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 163.24, 161.28, 158.84, 139.26, 129.54, 127.93, 127.69, 125.95, 125.81, 125.77, 125.07, 124.24, 123.86, 120.61, 118.83, 115.91, 115.70, 114.19, 65.63, 57.85. ESI-HRMS (m/z): calcd C17H13BrFNO3 for [M − H]−: 375.9985, 377.9964; found 375.9975, 377.9953. RT,HPLC = 6.84 min.

4.6. Biochemistry

4.6.1. Cell Lines, and Culture Conditions

All the reagents and chemicals were purchased from commercial sources. HIV-1 Integrase Assay Kit was purchased from Abnova. MT-4 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 media and equipped with 10% FBS (Gibco, Sidney, Australia), 100 units/mL penicillin and 100 units/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere (5% CO2 and 95% air).

4.6.2. Strand Transfer Inhibition Assay

The strand transfer assay was performed using an HIV-1 integrase assay kit (Abnova, Taipei, CN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Each sample was dissolved in DMSO and diluted to a final desired concentration (80, 40, 20, 10, 5 μM) with reaction buffer. Briefly, 100 μL of DS DNA solution was added to each well and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C, and the liquid was removed from the wells and washed 3 times with wash buffer. Then, 200 μL of blocking buffer was added to each well and incubated for 30 min in a 37 °C incubator. Followed by the aspiration of the liquid, each well was washed 3 times with reaction buffer, and 100 μL integrase enzyme solution was added to each well and incubated under similar conditions. Sequentially, 50 μL reaction buffer containing different concentrations of samples was added to each well and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. To each well was added 50 μL of TS DNA solution, and the reactions were mixed gently and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. Then, each well was washed 3 times with wash solution, incubated with 100 μL HRP antibody and incubated for 30 min at 37 °C. After washing the plate under the same conditions, 100 μL TMB peroxidase substrate solution was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. To terminate the reaction, 100 μL TMB stop solution was directly added to each well and the absorbance of the sample was determined using a plate reader (ELx800UV, Bio-Tek Instrument Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) at 450 nm.

4.6.3. Cytotoxicity Assay

The cytotoxicity of the title compounds was tested through MTT analysis on MT-4 cells. Cells were seeded in 96-well plates with a density of 50,000 cells/well and coincubated with serial diluted compounds (2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 μM) at 37 °C for five days. MTT (Sigma) was then added to each well to a final concentration of 0.5 mg/mL and incubated for 2 h. Subsequently, the medium was decanted, and 150 μL of DMSO was added to each well. The absorbance was obtained using a microplate reader at 570 nm, and all measurements were conducted three times under the same condition. Finally, 50% cytotoxicity concentration (CC50) values were calculated by Graphpad Prism 8.

Acknowledgments

We thank Guizhou Science and Technology Department and Guizhou Medical University for technical support to the project activities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/molecules28248020/s1, Figure S1: Binding mode analysis of HIT101057921, HIT104550697, HIT106924020, HIT105485118, HIT105499167, HIT106066563, HIT101131099, and HIT102924146 with HIV-1 integrase; Table S1: Libdock scores of 168 compounds through ADMET screening; Table S2: Binding free energies (kcal·mol-1) of 25 compounds through autodock vina.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Z. and C.-H.L.; methodology, C.-H.L.; software, G.-Y.Y.; validation, Y.-C.W., and W.-L.Z.; formal analysis, R.-H.Z.; investigation, Y.-L.Z. resources, Y.-J.L.; data curation, S.-G.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.-H.Z. writing—review and editing, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the foundation of Guizhou Science and Technology Department (qiankehejichu [2020]1Z008, qiankehejichu-ZK [2021]yiban551, qiankehezhicheng [2021]yiban425, YQK [2023]031), the project of Guizhou Medical University (21NSFCP44, and 20NSP076), and the Talents Project of Guizhou Provincial Department of Education Science and Technology (qianjiaoji [2022]081).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Yoshimura K. Current status of HIV/AIDS in the ART era. J. Infect. Chemother. 2017;23:12–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pomerantz R.J., Horn D.L. Twenty years of therapy for HIV-1 infection. Nat. Med. 2003;9:867–873. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amariles P., Rivera-Cadavid M., Ceballos M. Clinical relevance of drug interactions in people living with human immunodeficiency virus on antiretroviral therapy-update 2022: Systematic review. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:2488. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics15102488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lesbats P., Engelman A.N., Cherepanov P. Retroviral DNA integration. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:12730–12757. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eid A., Qi Y. Prime editor integrase systems boost targeted DNA insertion and beyond. Trends Biotechnol. 2022;40:907–909. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2022.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruelas D.S., Greene W.C. An integrated overview of HIV-1 latency. Cell. 2013;155:519–529. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hazuda D.J. HIV integrase as a target for antiretroviral therapy. Curr. Opin. HIV AIDS. 2012;7:383–389. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283567309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiu K.T., Davies R.D. Structure and function of HIV-1 integrase. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2004;4:965–977. doi: 10.2174/1568026043388547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gill M.S.A., Hassan S.S., Ahemad N. Evolution of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and integrase dual inhibitors: Recent advances and developments. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;179:423–448. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao X.Z., Smith S.J., Maskell D.P., Métifiot M., Pye V.E., Fesen K., Marchand C., Pommier Y., Cherepanov P., Hughes S.H., et al. Structure-guided optimization of HIV integrase strand transfer inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2017;60:7315–7332. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aknin C., Smith E.A., Marchand C., Andreola M.-L., Pommier Y., Metifiot M. Discovery of novel integrase inhibitors acting outside the active site through high-throughput screening. Molecules. 2019;24:3675. doi: 10.3390/molecules24203675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramkumar K., Yarovenko V.N., Nikitina A.S., Zavarzin I.V., Krayushkin M.M., Kovalenko L.V., Esqueda A., Odde S., Neamati N. Design, Synthesis and structure-activity studies of rhodanine derivatives as HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Molecules. 2010;15:3958–3992. doi: 10.3390/molecules15063958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y., Gu S.-X., He Q., Fan R. Advances in the development of HIV integrase strand transfer inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021;225:113787. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.113787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahajan P.S., Smith S.J., Hughes S.H., Zhao X., Burke T.R. A practical approach to bicyclic carbamoyl pyridones with application to the synthesis of HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitors. Molecules. 2023;28:1428. doi: 10.3390/molecules28031428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rashamuse T.J., Fish M.Q., Coyanis E.M., Bode M.L. Studies towards the design and synthesis of novel 1,5-diaryl-1H-imidazole-4-carboxylic acids and 1,5-diaryl-1H-imidazole-4-carbohydrazides as host LEDGF/p75 and HIV-1 integrase interaction inhibitors. Molecules. 2021;26:6203. doi: 10.3390/molecules26206203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Summa V., Petrocchi A., Bonelli F., Crescenzi B., Donghi M., Ferrara M., Fiore F., Gardelli C., Gonzalez Paz O., Hazuda D.J., et al. Discovery of Raltegravir, a potent, selective orally bioavailable HIV-integrase inhibitor for the treatment of HIV-AIDS infection. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:5843–5855. doi: 10.1021/jm800245z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimura K., Kodama E.N. Elvitegravir: A new HIV integrase inhibitor. Antivir. Chem. Chemother. 2009;20:79–85. doi: 10.3851/IMP1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dow D.E., Bartlett J.A. Dolutegravir, the second-generation of integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) for the treatment of HIV. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2014;3:83–102. doi: 10.1007/s40121-014-0029-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowan-Nash A.D., Korry B.J., Mylonakis E., Belenky P. Cross-domain and viral interactions in the microbiome. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2019;83:10–1128. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00044-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swindells S., Andrade-Villanueva J.-F., Richmond G.J., Rizzardini G., Baumgarten A., Masiá M., Latiff G., Pokrovsky V., Bredeek F., Smith G., et al. Long-acting Cabotegravir and Rilpivirine for maintenance of HIV-1 suppression. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1112–1123. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1904398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Métifiot M., Johnson B.C., Kiselev E., Marler L., Zhao X.Z., Burke T.R., Jr., Marchand C., Hughes S.H., Pommier Y. Selectivity for strand-transfer over 3′-processing and susceptibility to clinical resistance of HIV-1 integrase inhibitors are driven by key enzyme–DNA interactions in the active site. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:6896–6906. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hare S., Maertens G.N., Cherepanov P. 3′-Processing and strand transfer catalysed by retroviral integrase in crystallo. EMBO J. 2012;31:3020–3028. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wainberg M.A., Zaharatos G.J., Brenner B.G. Development of antiretroviral drug resistance. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011;365:637–646. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1004180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tao K., Rhee S.-Y., Chu C., Avalos A., Ahluwalia A.K., Gupta R.K., Jordan M.R., Shafer R.W. Treatment emergent Dolutegravir resistance mutations in individuals naïve to HIV-1 integrase inhibitors: A rapid scoping review. Viruses. 2023;15:1932. doi: 10.3390/v15091932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hurt C.B., Sebastian J., Hicks C.B., Eron J.J. Resistance to HIV integrase strand transfer inhibitors among clinical specimens in the United States, 2009–2012. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;58:423–431. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith S.J., Zhao X.Z., Burke T.R., Hughes S.H. Efficacies of Cabotegravir and Bictegravir against drug-resistant HIV-1 integrase mutants. Retrovirology. 2018;15:37. doi: 10.1186/s12977-018-0420-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook N.J., Li W., Berta D., Badaoui M., Ballandras-Colas A., Nans A., Kotecha A., Rosta E., Engelman A.N., Cherepanov P. Structural basis of second-generation HIV integrase inhibitor action and viral resistance. Science. 2020;367:806–810. doi: 10.1126/science.aay4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Passos D.O., Li M., Jóźwik I.K., Zhao X.Z., Santos-Martins D., Yang R., Smith S.J., Jeon Y., Forli S., Hughes S.H., et al. Structural basis for strand-transfer inhibitor binding to HIV intasomes. Science. 2020;367:810–814. doi: 10.1126/science.aay8015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang C., Xie Q., Wan C.C., Jin Z., Hu C. Recent advances in small-molecule HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Curr. Med. Chem. 2021;28:4910–4934. doi: 10.2174/0929867328666210114124744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Diller D.J., Merz K.M., Jr. High throughput docking for library design and library prioritization. Proteins. 2001;43:113–124. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20010501)43:2<113::AID-PROT1023>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao S.N., Head M.S., Kulkarni A., LaLonde J.M. Validation studies of the site-directed docking program LibDock. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2007;47:2159–2171. doi: 10.1021/ci6004299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu J., Ma Y., Zhou H., Zhou L., Du S., Sun Y., Li W., Dong W., Wang R. Identification of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) inhibitors through De Novo Evoluton, synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular dynamics simulation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;526:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang T.T., Sun M.F., Chen H.Y., Tsai F.J., Fisher M., Lin J.G., Chen C.Y. Screening from the world’s largest TCM database against H1N1 virus. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2011;28:773–786. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2011.10508605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang S., Jiang J.H., Li R.Y., Deng P. Docking-based virtual screening of TβR1 inhibitors: Evaluation of pose prediction and scoring functions. BMC Chem. 2020;14:52. doi: 10.1186/s13065-020-00704-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xue X., Zhang Y., Liu Z., Song M., Xing Y., Xiang Q., Wang Z., Tu Z., Zhou Y., Ding K., et al. Discovery of benzo[cd]indol-2(1H)-ones as potent and specific BET bromodomain inhibitors: Structure-based virtual screening, optimization, and biological evaluation. J. Med. Chem. 2016;59:1565–1579. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang Z., You Q., Zhang X. Medicinal chemistry of metal chelating fragments in metalloenzyme active sites: A perspective. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;165:172–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mbhele N., Chimukangara B., Gordon M. HIV-1 integrase strand transfer inhibitors: A review of current drugs, recent advances and drug resistance. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2021;57:106343. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2021.106343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kapewangolo P., Tawha T., Nawinda T., Knott M., Hans R. Sceletium tortuosum demonstrates in vitro anti-HIV and free radical scavenging activity. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2016;106:140–143. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2016.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang F., Chen W., Yi K., Wu Z., Si Y., Han W., Zhao Y. The evaluation of catechins that contain a galloyl moiety as potential HIV-1 integrase inhibitors. Clin. Immunol. 2010;137:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ivashchenko A.A., Ivanenkov Y.A., Koryakova A.G., Karapetian R.N., Mitkin O.D., Aladinskiy V.A., Kravchenko D.V., Savchuk N.P., Ivashchenko A.V. Synthesis, biological evaluation and in silico modeling of novel integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs) Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;189:112064. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipinski C.A., Lombardo F., Dominy B.W., Feeney P.J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001;46:3–26. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baell J.B., Holloway G.A. New substructure filters for removal of pan assay interference compounds (PAINS) from screening libraries and for their exclusion in bioassays. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:2719–2740. doi: 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials.