Abstract

Inclusion body–associated proteins IbpA and IbpB of MW 16 KDa are the two small heat-shock proteins (sHSPs) of Escherichia coli, and they have only holding, but not folding, chaperone activity. In vitro holdase activity of IbpB is more than that of IbpA, and in combination, they synergise. Both IbpA and IbpB monomers first form homodimers, which as building blocks subsequently oligomerize to make heavy oligomers with MW of MDa range; for IbpB, the MW range of heavy oligomers is 2.0–3.0 MDa, whereas for IbpA oligomers, the values in MDa are not so specified/reported. By temperature upshift, such large oligomers of IbpB, but not of IbpA, dissociate to make relatively small oligomeric assemblies of MW around 600–700KDa. The larger oligomers of IbpB are assumed to be inactive storage form, which on facing heat or oxidative stress dissociate into smaller oligomers of ATP-independent holding chaperone activity. These smaller oligomers bind with stress-induced partially denatured/unfolded and thereby going to be aggregated proteins, to give them protection against permanent damage and aggregation. On withdrawal of stress, IbpB transfers the bound substrate protein to the ATP-dependent bi-chaperone system DnaKJE-ClpB, having both holdase and foldase properties, to finally refold the protein. Of the two sHSPs IbpA and IbpB of E. coli, this review covers the recent advances in research on IbpB only.

Keywords: E. coli, sHSP IbpB, Oligomers of IbpB, Holdase and foldase activities, DnaKJE-ClpB bi-chaperone system

Introduction

The phenomenon of heat-shock response, mediated by heat responsive proteins, was initially observed in Drosophila, a common fruit fly, as consequence of heat stress (Ritossa 1962). Later on, numerous studies on heat responsive expression throughout living systems revealed that every organism develops certain mechanism to overcome various stresses such as exposure to heat or oxidative chemicals and environment. Over-production of heat-shock proteins (HSPs) is one of the most important mechanisms, by which an organism resists such stresses to certain limit (Shan et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2020; Feng et al. 2019). Temperature up-shift promotes expression of heat-shock genes to produce HSPs (Aolymat et al. 2023; Scharf et al. 2012; Akerfelt et al. 2010). HSPs are classified as HSP100, HSP90, HSP70, HSP 60 and sHSPs etc., depending on their MW 100, 90, 70, 60 and 12–42 KDa respectively (Alagar Boopathy et al. 2022; Mogk et al. 2019). Different chaperone systems ‘DnaKJE’ (consisting of chaperone DnaK [HSP70] with its associate co-chaperone proteins DnaJ [HSP40] and GrpE [HSP20]), ClpB [HSP100] and ‘GroELS’ (consisting of chaperone GroEL [HSP60] with its co-chaperone protein GroES [HSP10]) have ATP-dependent holding and folding properties both, whereas sHSPs have ATP-independent holdase property only, but not foldase property (Hibshman et al. 2023; Piróg et al. 2021; Mogk et al. 2019; Bhattacharjee et al. 2015; Singha Roy et al. 2014).

In E. coli, based on functions, HSPs are of two types — (1) chaperones like GroELS, DnaKJE, ClpB, IbpA/B and (2) proteases like Lon, ClpXP, Htra, Hflb, FtsH (Queraltó et al. 2023; Kędzierska-Mieszkowska & Zolkiewski 2021; Faust et al. 2020; Rosenzweig et al. 2019). The purposes of major cytosolic chaperone and protease systems under conditions of heat or oxidative stress are best studied in E. coli (Mogk et al. 2003a, b). The chaperones have holdase property to hold first the proteins (which tend to be denatured, unfolded and finally aggregated under stress) and then to refold them by their foldase property after withdrawal of the stress (Rosenzweig et al. 2019; Zhao et al. 2019; Nunes et al. 2015; Young 2010; Zuehlke & Johnson 2010). The proteases have the ability to degrade the permanently denatured proteins, which are irreversibly damaged and unable to fold back to their native configuration (Pulido et al. 2016; Kirstein et al. 2009; Molière & Turgay 2009; Zheng et al. 2002). In E. coli, majority of heat-shock genes for chaperones and proteases are transcribed by RNA polymerase with the alternative sigma factor σ32 (Miwa & Taguchi 2023; Schumann 2016; Patra et al. 2015; Anckar & Sistonen 2011; Chhabra et al. 2006) and few by another alternative sigma factor σ54 (Roncarati & Scarlato 2017; Sachdeva et al. 2010), instead of the normal sigma factor σ70. The family of sHSPs has been found to be broadly distributed throughout different organisms like bacteria, fungi, plants and also in animals (Bakthisaran et al. 2015; Haslbeck & Vierling 2015). The MW of such sHSPs ranges from 15 to 21 KDa in bacteria, 24 to 43 KDa in yeasts, 20 to 24 KDa in Drosophila, 17 to 26 KDa in plants, and 20 to 27 KDa in vertebrates per monomer, and they form large oligomeric complex structure (Basha et al. 2012; Mymrikov et al. 2011; Lelj-Garolla & Mauk 2005). Each monomer has 60–70% of β strands and few or no α-helix (Bellanger and Weidmann 2023; Augusteyn 2004). In most organisms, the structure of sHSPs is conserved as IgG-type β-sandwich structure with oligomeric assemblies (Bellanger and Weidmann 2023; Klevit 2020; Haslbeck et al. 2005).

E. coli has only two types of sHSPs IbpA and IbpB of 16 KDa per monomer (Guzzo 2012). Purified IbpB form multimers by several subunit assembly and exists in two major oligomeric forms — heavy oligomers of MW 2–3 MDa and light oligomers of 600–700 KDa, which dissociate further to much smaller oligomers during prolonged heat treatment (Singha Roy et al. 2014; Bepperling et al. 2012; Strózecka et al. 2012; Shearstone & Baneyx 1999). IbpA, a co-partner of IbpB, also forms multimers of MW range of MDa (Strózecka et al. 2012); however, there is no report on specific MDa values of IbpA. Moreover, there is no report also on dissociation of IbpA large multimers to smaller oligomers during heat stress. IbpA and IbpB both have holdase, but not foldase, chaperone activity (Hibshman et al. 2023; Piróg et al. 2021; Mogk et al. 2019; Bhattacharjee et al. 2015; Singha Roy et al. 2014). The holding chaperone activity of IbpB is more than that of IbpA, and in combination, they synergise, as observed from in vitro studies on suppression of heat-induced inactivation of few enzymes in presence of IbpA/B (Obuchowski and Liberek 2020; Obuchowski et al. 2019; Singha Roy et al. 2014; Kitagawa et al. 2002). Here, we suggest from reported experimental results that IbpB do exist in poly-dispersed oligomeric forms, and the heavy-sized oligomers of MDa range are less active storage forms, which on heat or oxidative stress dissociate to produce smaller oligomers of KDa range with more holdase chaperone activity. Our on-going experimental results (unpublished) corroborate the suggested view. In this review, we have focused on the oligomeric polydispersity and different oligomer-dependent chaperone activity of E. coli sHSP IbpB.

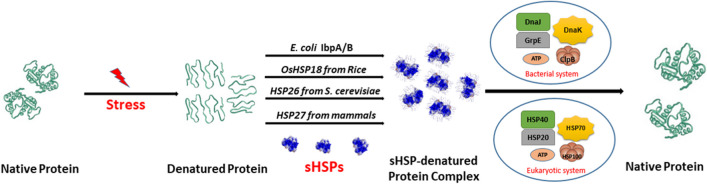

Interaction of sHSPs with their substrates

sHSPs of any organism (IbpA/B of E. coli, OsHSP18 of rice, HSP26 of Staphylococcus cerevisiae, HSP27 of mammals) bind with stress-abused proteins and provide them proper folding-competent state in absence of ATP, and any such bound complex transfers the substrate protein to other ATP-dependent major chaperone systems (like E. coli DnaKJE-ClpB or their homologous HSP70-HSP100 systems in plants, fungus and animals) which fold or folds the substrate in proper conformation (Haslbeck et al. 2019; Janowska et al. 2019; Haslbeck & Vierling 2015), as schematically represented in Fig. 1. It remains still unclear which region or regions of substrate protein bind(s) with sHSPs and whether there exists any common recognition motif. Reports suggest that sHSPs are less effective in suppression of the aggregation of large substrate, indicating that interaction of sHSPs with their substrate is mass dependent rather than molar ratio, charge or hydrophobicity (Haslbeck & Vierling 2015; Basha et al. 2012). Under heat stress, there is increase in the number of active oligomers (through dissociation of large multimeric forms) and also increase in the substrate recognition sites on sHSPs. Phosphorylation and other post translational modifications at serine residues of many sHSPs, viz., HSP25, HSP27 of mouse and human respectively lead to dissociation of inactive to active form and change substrate recognition sites (Haslbeck & Vierling 2015; Lelj-Garolla & Mauk 2005; Gaestel 2002). Sometimes, co-assembly of sHSPs is found to affect chaperone activity and substrate recognition, e.g. E. coli; IbpA or IbpB individually has lower chaperone (holdase) activity, but their co-assembled subunit has more chaperone activity (Obuchowski and Liberek 2020; Obuchowski et al. 2019; Singha Roy et al. 2014; Kitagawa et al. 2002). sHSPs are composed of a conserved α-crystallin domain of 90–100 amino acids (first observed in eye lens protein that defends it from cataract formation), bordered by variable amino- and carboxy-terminal domains (Haslbeck & Vierling 2015; Treweek et al. 2015; Lelj-Garolla & Mauk 2005). The ACD has a signature motif GVLTL (between the β8 and β9 sheets) with seven or eight anti-parallel β strands, which form β-sandwich structure: one with β4, β5, and β6/7 strands and the other with β2, β3, β8, and β9 strands (Bellanger and Weidmann 2023; Tikhomirova et al. 2017). Both N-terminal domain (NTD) and α-crystallin domain (ACD) of sHSPs have been implicated in substrate recognition and chaperone activity, whereas C-terminal domain (CTD) is very important for oligomerization of subunits (Janowska et al. 2019; Strózecka et al. 2012). The increase in temperature and other oxidative stresses perhaps modify both substrate proteins and NTD/ACD of sHSPs in such a way that total hydrophobicity is increased in both cases, which make substrates and sHSPs unstable. Due to increase in hydrophobicity, both sHSPs and substrates interact with each other to make complex assemblies that overcome surrounding hydrophilic environment. The size of such complex of sHSPs and aggregated substrates is smaller than that of stress-induced protein aggregates formed in absence of sHSPs. When stress is removed, these sHSP-bound aggregated proteins are subjected to disaggregating-refolding chaperone system DnaKJE-ClpB in E. coli or HSP70-HSP100 in eukaryotes (Obuchowski et al. 2019; Mogk et al. 2019; Żwirowski et al. 2017).

Fig. 1.

Holding of stressed proteins by sHSPs, followed by folding with the help of heat-shock chaperone systems. sHSPs bind with stress-induced substrate protein aggregates and on withdrawal of stress transfer the aggregated substrate to disaggregating and refolding (DnaKJE-ClpB) chaperone system in bacteria or to its eukaryotic homologue HSP70-HSP100 system, for proper re-folding of cellular proteins

So far as the E. coli sHSPs IbpA/B are concerned, the specific step-by-step molecular mechanism of their interactions entails that (i) under heat or oxidative stress, IbpA first binds with partially denatured, unfolded and aggregated cellular proteins and changes the biochemical properties of the aggregates to shield them from making large aggregates; the size of the IbpA-bound aggregates is much smaller than the substrate aggregate alone in absence of IbpA (Ratajczak et al. 2009). (ii) The complex formation between IbpA and its substrate aggregates facilitates binding of IbpB to the IbpA-embedded aggregated proteins, through interaction with IbpA; (iii) the interaction between IbpB and IbpA results in less stable association of IbpA with the aggregating proteins, generating more IbpA-free aggregates for subsequent processing, on withdrawal of stress, by the DnaKJE-ClpB bi-chaperone system; (iv) DnaKJE first outcompetes the IbpA,B and recruits the chaperone ClpB to activate it, and (v) the protein aggregates are finally subjected to DnaK-ClpB-dependent disaggregation and refolding phenomena (Obuchowski et al. 2019; Żwirowski et al. 2017; Ratajczak et al. 2009; Matuszewska et al. 2005).

Activity and regulation of the E. coli sHSP IbpB

Evolutionary history analysis reports an interesting feature that y-proteobacteria possess only one sHSP IbpA, but IbpA gene duplication in later stage evolved IbpB gene in Enterobacteriaceae (except Erwiniaceae), which progressed faster with distinct role (Obuchowski et al. 2019). Although IbpA has protective role against stress-induced protein aggregates, the ultimate rescue or refold rate of the trapped aggregates is very low; even subsequent DnaKJE-ClpB-mediated disaggregation and refolding substrate aggregate is inhibited. Paralogous IbpB evolved with distinct role as rescuer, which binds with protein assemblies through IbpA and outcompetes IbpA, increasing accession for DnaK (Obuchowski et al. 2019). Nevertheless, IbpA is important against protein aggregation; however, IbpB is also needed to replace IbpA from aggregates and to promote DnaK binding space to the aggregates and finally to disaggregate and refold the trapped proteins by ClpB-DnaKJE bichaperone system. IbpB thus collaborates with the heat-shock chaperone system DnaKJE-ClpB. Deletion or mutation of IbpB does not make any complication in cell growth and survival; the mutant cells become faintly sensitive to heat; however, the effects are boosted by mutation in DnaKJE-system (Matuszewska et al. 2005; Mogk et al. 2003a, b; Kitagawa et al. 2000). Over-expression of IbpB makes E. coli cells impervious to heat shock temperature like 50 °C and also increases cell survival against oxidative/material stress (Cu2+, Ca2+, Cd2+) (Asthana et al. 2014; Kitagawa et al. 2000). Though sHSPs act in ATP-independent manner, it is found that the presence of ATP increases chaperone activity of IbpB (Valdez et al. 2002). At physiological condition, level of IbpB in bacterial cell is very low because of tight regulation at both transcriptional and translational levels. In E. coli, IbpB and IbpA genes are arranged into an operon, controlled by the transcription factor σ32 — the main heat-shock regulator (Obuchowski et al. 2021; Schumann 2016). At normal temperature (30–37 °C), the low level of IbpB protein is regulated by three pathways viz., (1) by hairpin configuration of IbpB m-RNA that blocks the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (conceptualized as RNA thermometer) and consequently stops unnecessary translation of the protein (Gaubig et al. 2011), 2) by the IbpA-mediated inhibition of translation of IbpB m-RNA, due to binding of IbpA protein with the 5’UTR region of IbpB mRNA (Cheng et al. 2023) and (3) by possible degradation of IbpB by Lon protease (Bissonnette et al. 2010). At stress condition, the level of IbpB is increased by the activation of transcription factor σ32, melting of mRNA hairpin, and release of ibpB mRNA from IbpA (Cheng et al. 2023; Obuchowski et al. 2021; Waldminghaus et al. 2009).

Structure and oligomeric forms of the sHSP IbpB

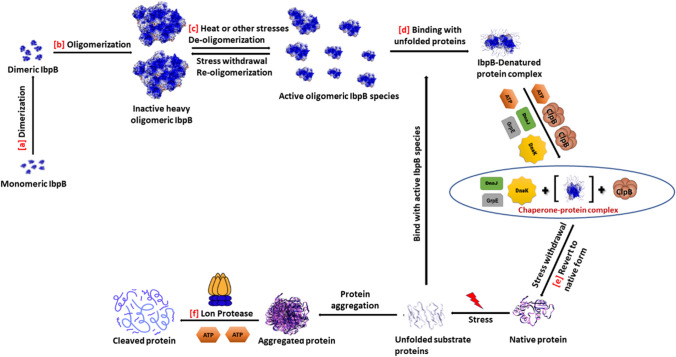

Sequence alignment of all sHSPs including IbpB shows a highly conserved α-crystallin domain (ACD), flanked by the N-terminal and C-terminal domains (NTD and CTD). The NTD and CTD are variable in length and sequence, except for a few conserved stretches (Piróg et al. 2021; Bhattacharjee et al. 2015; Kriehuber et al. 2010; Lelj-Garolla & Mauk 2005). Like α-crystallin protein, sHSPs of many organisms assemble into high molecular weight oligomeric (10–40 mers) complex structure, e.g. α-crystallin domain-containing sHSPs 16.5, 16.9 and 27 from organisms like Methanococcus jannaschii, wheat and human are of 24-, 12- and 30-mers respectively (Sprague-Piercy et al. 2021; Mymrikov et al. 2020; Aquilina et al. 2013; Hilton et al. 2013; Lelj-Garolla & Mauk 2005). Moreover, oligomeric complex of sHSPs like HSP25 and HSP27 of mouse and human respectively vary in the number of monomeric subunits, implying that the oligomers are poly-dispersed in nature, and so, their crystal structure analysis is difficult and limited (Haley et al. 2000). Most of the sHSPs exist in dimeric form, which as building blocks are oligomerized to make large multimers (Hu et al. 2022). The size of oligomers depends on surrounding environment and conditions like pH, phosphorylation and other modifications in the proteins, creating polydispersity. Truncation of the N- and C-terminal sequences reduces polydispersity and facilitates stable oligomer formation and thereby crystallization (Strózecka et al. 2012), signifying that the number of subunits in oligomer depends on NTD and CTD sequences. EM studies on homo-oligomerization of IbpA depict that the IbpAΔC deletion mutant at CTD does not form oligomeric fibrils, while the IbpAΔN deletion mutant at NTD forms fibril structures; this suggests that the C-terminus is involved in filament formation. N-terminus (NTD) is important for substrate interaction (Chernova et al. 2020; Strózecka et al. 2012). IbpA fibril formation occurs either due to its over production at physiologically stable condition or in absence of its co-partner IbpB (Ratajczak et al. 2009). Heat or presence of misfolded proteins promotes dissociation of storage filamentous IbpA to its active form (Strózecka et al. 2012; Lethanh et al. 2005). Size exclusion chromatography result demonstrates that purified IbpB forms multimeric structure, having molecular weight ranging up to 2.0–3.0 MDa, made up of 100–150 subunits. Like IbpB, IbpA is also found to form MDa-sized heavy filament oligomers (Strózecka et al. 2012; Kitagawa et al. 2000, 2002; Kuczynska-Wisnik et al. 2002), but their MW range is not specified. The heavy multimeric structures of IbpB dissociate at high temperature; below 50 °C, either there is no or very slight dissociation, whereas above 50 °C, dissociation takes place to oligomers having molecular masses of 600–700 KDa, which further dissociate to more small-sized oligomers, when the temperature and incubation time are extended (Kitagawa et al. 2002; Shearstone & Baneyx 1999). The dissociated smaller sized oligomers become re-oligomerized to make large and heavy multimers of MDa size on withdrawal of stress (Kitagawa et al. 2002). There is no in vivo evidence of formation of IbpB hetero-oligomers with IbpA in bacterial cells, but in vitro study shows that IbpA may influence in heterodimer and heterotetramer formation with IbpB (Kuczynska-Wisnik et al. 2002). Native mass spectrometry, NMR and molecular dynamics (MD) studies suggest in vitro formation of IbpA-IbpB heterodimer, in the similar way of formation of homodimers (Piróg et al. 2021). NMR titration test strongly indicates that IbpA and IbpB heterodimer construction is preferred over IbpA and IbpB homodimer formation (Piróg et al. 2021). Temperature-induced alteration in the oligomeric state of sHSPs is crucial for their holding chaperone activity (Matuszewska et al. 2005). The smallest particles of IbpB is spherical and 10–20 nm in diameter; they interact to make 100–200-nm particles, which further aggregate within themselves to form 400-nm to 1.7-µm large particles, detected by dynamic light scattering (DLS) study (Shearstone & Baneyx 1999). Increase of temperature triggers dissociation of large-sized sHSP oligomers to smaller forms, having the capability to bind with heat-assaulted substrate proteins and make assemblies of sHSP-substrate complex. Such assemblies are smaller than amorphous aggregates and store substrates in near native conformations, protecting them from further aggregation (Piróg et al. 2021). Figure 2 represents summarized view of the pathway of IbpB action, i.e. (i) heat-induced dissociation of the inactive storage form of MDa-sized large multimers of IbpB to smaller active oligomers, (ii) complex formation of the active oligomers with heat-denatured substrate proteins by their ATP-independent holdase property, followed by (iii) transfer of IbpB-holded substrate protein to the major heat-shock chaperone system DnaKJE-ClpB and subsequent refolding of heat-stressed partially denatured and so, unfolded protein substrate through an ATP dependent pathway, to native functional form.

Fig. 2.

Pathway of holding chaperone action of sHSP IbpB, followed by holding-folding actions of chaperone systems GroELS and/or DnaKJE-ClpB, to protect E. coli proteins tending to be denatured/unfolded, by heat or oxidative stress. (a) Monomer of IbpB, after its synthesis, is first dimerized; (b) subsequently, the homodimers, as building blocks, are oligomerized to make less active, storage form of heavy oligomers with MW range of few MDa; (c) by temperature or stress up-shift, the large oligomers dissociate to make active, small-sized oligomers of KDa range; (d) the active oligomers bind with partially denatured, unfolded proteins and stabilize them by their holdase property with no requirement of ATP; (e) the stabilized complex, after withdrawal of stress, is subjected to ATP-dependent major chaperone system DnaKJE-ClpB, which have both holdase and foldase properties, to bring the stress-induced partially unfolded proteins in native forms; (f) permanently damaged proteins with irreversibly unfolded form aggregates to be attacked and cleaved by different ATP-dependent heat-shock protease system

Conclusion

Expression of sHSPs in cells at normal physiological condition is very low. With occurrence of heat or other oxidative stresses, their expression is increased. It is believed that the monomers of a sHSP form dimers first, which are subsequently oligomerized to form a large multimeric structure, as a storage form, with poor holdase activity. On exposure to stress, the large multimers breakdown to small oligomers, which actually possesses the optimum holding chaperone activity. The interaction between dimeric sHSPs and substrate aggregates is dynamic, but the interaction between oligomeric sHSPs and substrate aggregates is quite stable; the suggested explanation is that the substrate aggregates are tethered by sHSP oligomers at multiple sites (Żwirowski et al. 2017; Cheng et al. 2008; Mogk et al. 2003a, b). However, in case of yeast sHsp26, the homo-oligomeric 24-subunit complex (made of 12 dimers), on exposure to heat stress, does not breakdown to small oligomers, instead gets activated through conformational change that causes binding of the substrate proteins to the complex (Franzmann et al. 2008; White et al. 2006).

Monomers of E. coli IbpA and IbpB first assemble together to form homo or heterodimers in vitro; subsequently, the homodimers further assemble to form multimers of MDa size; however, there is no report about formation of hetero-multimers constituted by IbpA and IbpB both. As confirmed by size exclusion chromatography, large multimers of IbpB (assembly of 100–150 IbpB monomers) of MW 2–3 MDa dissociate on heat stress to small oligomeric structures of size 600–700 KDa, which dissociate further to more small oligomers, if they face prolonged temperature shock (Sprague-Piercy et al. 2021; Mymrikov et al. 2020; Singha Roy et al. 2014; Aquilina et al. 2013; Shearstone & Baneyx 1999). The large multimeric IbpB is considered as less active and as storage form, while their heat-dissociated smaller species are believed to be responsible for chaperone activity (Obuchowski et al. 2021; Piróg et al. 2021; Mogk et al. 2019; Hilton et al. 2013). When the temperature stress is removed, functionally active small IbpB oligomers of KDa range reassemble to functionally inactive large IbpB multimers of MDa range. Studies, using the techniques of dynamic light scattering (DLS) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM), suggest that the smaller oligomers other than 600–700 KDa, the 600–700 KDa functional oligomers and the 2.0–3.0 MDa large multimers appear to be of size 10–20 nm, 100–200 nm and 400–1700 nm respectively (Shearstone & Baneyx 1999). IbpA also form large fibril structures of MDa range at normal condition; however, their specific molecular weight and their dissociation to small oligomers on exposure to heat or oxidative stress are not yet reported.

Experimental investigations are presently being carried out in our laboratory to identify the most active oligomeric form of IbpB as holding chaperone, because our size exclusion chromatography (SEC), gel electrophoresis (Native-PAGE) and atomic force microscopy (AFM) studies identify other smaller oligomers than the 600–700 KDa oligomers (our unpublished results). Through this review, the important queries that come out for future investigations are (i) why the dimers, not the sHSP monomers, are the building blocks for formation of the oligomers and (ii) what is the importance of having heavy multimeric storage and inactive form of sHSPs, while the amount of sHSPs in cells at normal physiological condition is (Sun et al. 2002) very low?

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the Department of Science and Technology and Biotechnology (DSTBT), Government of West Bengal, for financial assistance. We further acknowledge the University Grant Commission, Govt. of India, for the ‘Departmental Research Support (II)’ grant under its ‘Special Assistance Programme’, and the Department of Science and Technology, Govt. of India, for its ‘Funds for Improvement of Science and Technology Infrastructure (FIST)’ to our department of Biochemistry and Biophysics.

Funding

Department of Science and Technology and Biotechnology (DSTBT),Gov. of West Bengal,University Grant Commission-SAP (UGC-SAP),Gov. of India),Department of Science and Technology,Gov. of India for FIST,Department of Higher Education,Government of West Bengal,University of Kalyani,West Bengal,India for their fellowship

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Akerfelt M, Morimoto RI, Sistonen L. Heat shock factors: integrators of cell stress, development and lifespan. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(8):545–555. doi: 10.1038/nrm2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alagar Boopathy LR, Jacob-Tomas S, Alecki C, Vera M. Mechanisms tailoring the expression of heat shock proteins to proteostasis challenges. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(5):101796. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.101796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anckar J, Sistonen L. Regulation of HSF1 function in the heat stress response: implications in aging and disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:1089–1115. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060809-095203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aolymat I, Hatmal MM, Olaimat AN. The emerging role of heat shock factor 1 (HSF1) and heat shock proteins (HSPs) in Ferroptosis. Pathophysiol: Pathophysiol. 2023;30(1):63–82. doi: 10.3390/pathophysiology30010007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilina JA, Shrestha S, Morris AM, Ecroyd H. Structural and functional aspects of hetero-oligomers formed by the small heat shock proteins αB-crystallin and HSP27. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(19):13602–13609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.443812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asthana A, Bollapalli M, Tangirala R, Bakthisaran R, Mohan Rao CH. Hsp27 suppresses the Cu(2+)-induced amyloidogenicity, redox activity, and cytotoxicity of α-synuclein by metal ion stripping. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;72:176–190. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augusteyn RC. α-crystallin: a review of its structure and function. Clin Exp Optom. 2004;87(6):356–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0938.2004.tb03095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakthisaran R, Tangirala R, Rao CM. Small heat shock proteins: role in cellular functions and pathology. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1854(4):291–319. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basha E, O’Neill H, Vierling E. Small heat shock proteins and α-crystallins: dynamic proteins with flexible functions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2012;37(3):106–117. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellanger T, Weidmann S. Is the lipochaperone activity of sHSP a key to the stress response encoded in its primary sequence? Cell Stress Chaperones. 2023;28:21–33. doi: 10.1007/s12192-022-01308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bepperling A, Alte F, Kriehuber T, Braun N, Weinkauf S, Groll M, Haslbeck M, Buchner J. Alternative bacterial two-component small heat shock protein systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(50):20407–20412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209565109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee S, Dasgupta R, Bagchi A. The small heat-shock proteins IbpA and IbpB in E. coli: the small ones with a big role. Curr Chem Biol. 2015;9(2):84–96. doi: 10.2174/2212796809666151022202506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bissonnette SA, Rivera-Rivera I, Sauer RT, Baker TA. The IbpA and IbpB small heat-shock proteins are substrates of the AAA+ Lon protease. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75(6):1539–1549. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G, Basha E, Wysocki VH, Vierling E. Insights into small heat shock protein and substrate structure during chaperone action derived from hydrogen/deuterium exchange and mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(39):26634–26642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802946200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Miwa T, Taguchi H (2023) Self-regulatory function of bacterial small heat shock protein IbpA through mRNA binding is conferred by a conserved arginine. CSH-bioRxiv:538363. 10.1101/2023.04.26.538363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Chernova LS, Bogachev MI, Chasov VV, Vishnyakov IE, Kayumov AR. N- and C-terminal regions of the small heat shock protein IbpA from Acholeplasma laidlawii competitively govern its oligomerization pattern and chaperone-like activity. RSC advances. 2020;10(14):8364–8376. doi: 10.1039/c9ra10172a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chhabra SR, He Q, Huang KH, Gaucher SP, Alm EJ, He Z, Hadi MZ, Hazen TC, Wall JD, Zhou J, Arkin AP, Singh AK. Global analysis of heat shock response in Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J Bacteriol. 2006;188(5):1817–1828. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.5.1817-1828.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust O, Abayev-Avraham M, Wentink AS, Maurer M, Nillegoda NB, London N, Bukau B, Rosenzweig R. HSP40 proteins use class-specific regulation to drive HSP70 functional diversity. Nature. 2020;587(7834):489–494. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2906-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng XH, Zhang HX, Ali M, Gai WX, Cheng GX, Yu QH, Yang SB, Li XX, Gong ZH. A small heat shock protein CaHsp25.9 positively regulates heat, salt, and drought stress tolerance in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;142:151–162. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzmann TM, Menhom P, Walter S, Buchner J. Activation of the chaperone Hsp26 is controlled by the rearrangement of its thermosensor domain. Mol Cell. 2008;29:207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaestel M. sHsp-phosphorylation: enzymes, signaling pathways and functional implications. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2002;28:151–169. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56348-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaubig LC, Waldminghaus T, Narberhaus F. Multiple layers of control govern expression of the Escherichia coli ibpAB heat-shock operon. Microbiology. 2011;157(1):66–76. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.043802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzzo J. Biotechnical applications of small heat shock proteins from bacteria. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44(10):1698–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley DA, Bova MP, Huang QL, Mchaourab HS, Stewart PL. Small heat-shock protein structures reveal a continuum from symmetric to variable assemblies. J Mol Biol. 2000;298(2):261–272. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck M, Vierling E. A first line of stress defense: small heat shock proteins and their function in protein homeostasis. J Mol Biol. 2015;427(7):1537–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck M, Miess A, Stromer T, Walter S, Buchner J. Disassembling protein aggregates in the yeast cytosol. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(25):23861–23868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m502697200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslbeck M, Weinkauf S, Buchner J. Small heat shock proteins: simplicity meets complexity. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(6):2121–2132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV118.002809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibshman JD, Carra S, Goldstein B. Tardigrade small heat shock proteins can limit desiccation-induced protein aggregation. Commun Biol. 2023;6(1):121. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-04512-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton GR, Lioe H, Stengel F, Baldwin AJ, Benesch JLP. Small heat-shock proteins: paramedics of the cell. Top Curr Chem. 2013;328:69–98. doi: 10.1007/128_2012_324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu C, Yang J, Qi Z, Wu H, Wang B, Zou F, Mei H, Liu J, Wang W, Liu Q. Heat shock proteins: biological functions, pathological roles, and therapeutic opportunities. MedComm. 2022;3(3):161. doi: 10.1002/mco2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowska MK, Baughman HER, Woods CN, Klevit RE. Mechanisms of small heat shock proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019;11(10):34025. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a034025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kędzierska-Mieszkowska S, Zolkiewski M. Hsp100 molecular chaperone ClpB and its role in virulence of bacterial pathogens. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(10):5319. doi: 10.3390/ijms22105319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirstein J, Molière N, Dougan DA, Turgay K. Adapting the machine: adaptor proteins for Hsp100/Clp and AAA+ proteases. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(8):589–599. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M, Matsumura Y, Tsuchido T. Small heat shock proteins, IbpA and IbpB, are involved in resistances to heat and superoxide stresses in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;184(2):165–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M, Miyakawa M, Matsumura Y, Tsuchido T. Escherichia coli small heat shock proteins, IbpA and IbpB, protect enzymes from inactivation by heat and oxidants. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269(12):2907–2917. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klevit RE. Peeking from behind the veil of enigma: emerging insights on small heat shock protein structure and function. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2020;25(4):573–580. doi: 10.1007/s12192-020-01092-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriehuber T, Rattei T, Weinmaier T, Bepperling A, Haslbeck M, Buchner J. Independent evolution of the core domain and its flanking sequences in small heat shock proteins. FASEB J. 2010;24(10):3633–3642. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-156992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynska-Wisnik D, Kçdzierska S, Matuszewska E, Lund P, Taylor A, Lipinska B, Laskowska E. The Escherichia coli small heat-shock proteins IbpA and IbpB prevent the aggregation of endogenous proteins denatured in vivo during extreme heat shock. Microbiology. 2002;148(6):1757–1765. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelj-Garolla B, Mauk AG. Self-association of a small heat shock protein. J Mol Biol. 2005;345(3):631–642. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lethanh H, Neubauer P, Hoffmann F. The small heat-shock proteins IbpA and IbpB reduce the stress load of recombinant Escherichia coli and delay degradation of inclusion bodies. Microb Cell Fact. 2005;4(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matuszewska M, Kuczyńska-Wiśnik D, Laskowska E, Liberek K. The small heat shock protein IbpA of Escherichia coli cooperates with IbpB in stabilization of thermally aggregated proteins in a disaggregation competent state. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(13):12292–12298. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412706200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miwa T, Taguchi H (2023) The Escherichia coli small heat shock protein IbpA plays a role in regulating the heat shock response by controlling the translation of σ32, CSH-bioRxiv:534623 10.1101/2023.03.28.534623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Miwa T, Chadani Y, Taguchi H. Escherichia coli small heat shock protein IbpA is an aggregation-sensor that self-regulates its own expression at posttranscriptional levels. Mol Microbiol. 2021;115(1):142–156. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogk A, Deuerling E, Vorderwülbecke S, Vierling E, Bukau B. Small heat shock proteins, ClpB and the DnaK system form a functional triade in reversing protein aggregation. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50(2):585–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogk A, Schlieker C, Friedrich KL, Schönfeld HJ, Vierling E, Bukau B. Refolding of substrates bound to small Hsps relies on a disaggregation reaction mediated most efficiently by ClpB/DnaK. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(33):31033–31042. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogk A, Ruger-Herreros C, Bukau B. Cellular functions and mechanisms of action of small heat shock proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2019;73:89–110. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molière N, Turgay K. Chaperone-protease systems in regulation and protein quality control in Bacillus subtilis. Res Microbiol. 2009;160(9):637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mymrikov EV, Seit-Nebi AS, Gusev NB. Large potentials of small heat shock proteins. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(4):1123–1159. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mymrikov EV, Riedl M, Peters C, Weinkauf S, Haslbeck M, Buchner J. Regulation of small heat-shock proteins by hetero-oligomer formation. J Biol Chem. 2020;295(1):158–169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunes JM, Mayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU, Müller DJ. Action of the Hsp70 chaperone system observed with single proteins. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6307. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obuchowski I, Liberek K. Small but mighty: a functional look at bacterial sHSPs. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2020;25:593–600. doi: 10.1007/s12192-020-01094-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obuchowski I, Piróg A, Stolarska M, Tomiczek B, Liberek K. Duplicate divergence of two bacterial small heat shock proteins reduces the demand for Hsp70 in refolding of substrates. PLoS Genet. 2019;15(10):e1008479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obuchowski I, Karaś P, Liberek K. The small ones matter-shsps in the bacterial chaperone network. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:666893. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2021.666893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra M, Roy SS, Dasgupta R, Basu T. GroEL to DnaK chaperone network behind the stability modulation of σ(32) at physiological temperature in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 2015;589(24):4047–4052. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2015.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piróg A, Cantini F, Nierzwicki Ł, Obuchowski I, Tomiczek B, Czub J, Liberek K. Two bacterial small heat shock proteins, IbpA and IbpB, form a functional heterodimer. J Mol Biol. 2021;433(15):167054. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2021.167054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulido P, Llamas E, Llorente B, Ventura S, Wright LP, Rodríguez-Concepción M. Specific Hsp100 chaperones determine the fate of the first enzyme of the plastidial isoprenoid pathway for either refolding or degradation by the stromal Clp protease in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(1):1005824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queraltó C, Álvarez R Ortega C, Díaz-Yáñez F, Paredes-Sabja D, Gil F. Role and regulation of Clp proteases: a target against gram-positive bacteria. Bacteria. 2023;2(1):1. doi: 10.3390/bacteria2010002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak E, Zietkiewicz S, Liberek K. Distinct activities of Escherichia coli small heat shock proteins IbpA and IbpB promote efficient protein disaggregation. J Mol Biol. 2009;386(1):178–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritossa F. A new puffing pattern induced by temperature shock and DNP in drosophila. Experientia. 1962;18(12):571–573. doi: 10.1007/BF02172188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roncarati D, Scarlato V. Regulation of heat-shock genes in bacteria: from signal sensing to gene expression output. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2017;41(4):549–574. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fux015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig R, Nillegoda NB, Mayer MP, Bukau B. The Hsp70 chaperone network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20(11):665–680. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva P, Misra R, Tyagi AK, Singh Y. The sigma factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: regulation of the regulators. FEBS J. 2010;277(3):605–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf KD, Berberich T, Ebersberger I, Nover L. The plant heat stress transcription factor (Hsf) family: structure, function and evolution. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1819(2):104–119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumann W. Regulation of bacterial heat shock stimulons. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2016;21(6):959–968. doi: 10.1007/s12192-016-0727-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan Q, Ma F, Wei J, Li H, Ma H, Sun P. Physiological functions of heat shock proteins. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2020;21(8):751–760. doi: 10.2174/1389203720666191111113726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shearstone JR, Baneyx F. Biochemical characterization of the small heat shock protein IbpB from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(15):9937–9945. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.15.9937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singha Roy S, Patra M, Nandy SK, Banik M, Dasgupta R, Basu T. In vitro holdase activity of E. coli small heat-shock proteins IbpA, IbpB and IbpAB: a biophysical study with some unconventional techniques. Protein Pept Lett. 2014;21(6):564–571. doi: 10.2174/0929866521666131224094408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprague-Piercy MA, Rocha MA, Kwok AO, Martin RW. α-crystallins in the vertebrate eye lens: complex oligomers and molecular chaperoneS. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2021;72:143–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-090419-121428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strózecka J, Chrusciel E, Górna E, Szymanska A, Ziętkiewicz S, Liberek K. Importance of N- and C-terminal regions of IbpA, Escherichia coli small heat shock protein, for chaperone function and oligomerization. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:2843–2853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.273847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Van Montagu M, Verbruggen N. Small heat shock proteins and stress tolerance in plants. BBA. 2002;1577(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(02)00417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhomirova TS, Selivanova OM, Galzitskaya OV. α-Crystallins are small heat shock proteins: functional and structural properties. Biochemistry. 2017;82(2):106–121. doi: 10.1134/s0006297917020031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treweek TM, Meehan S, Ecroyd H, Carver JA. Small heat-shock proteins: Important players in regulating cellular proteostasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:429–451. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1754-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez MM, Clark JI, Wu GJS, Muchowski PJ. Functional similarities between the small heat shock proteins Mycobacterium tuberculosis HSP 16.3 and human alphaB-crystallin. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269:1806–1813. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.02812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldminghaus T, Gaubig LC, Klinkert B, Narberhaus F. The Escherichia coli ibpA thermometer is comprised of stable and unstable structural elements. RNA Biol. 2009;6:455–463. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.4.9014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HE, Orlova EV, Chen S, Wang L, Ignatiou A, Gowen B, Stromer T, Franzmann TM, Haslbeck M, Buchner J, Saibil HR. Multiple distinct assemblies reveal conformational flexibility in the small heat shock protein Hsp26. Structure. 2006;14:1197–1204. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JC. Mechanisms of the Hsp70 chaperone system. Biochem Cell Biol = Biochim Biol Cell. 2010;88(2):291–300. doi: 10.1139/o09-175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Vecchi G Vendruscolo M, Körner R, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU. The Hsp70 chaperone system stabilizes a thermo-sensitive subproteome in E. coli. Cell Rep. 2019;28(5):1335–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao L, Zheng YG, Feng YH, Li MY, Wang GQ, Ma YF. Toxic effects of waterborne lead (Pb) on bioaccumulation, serum biochemistry, oxidative stress and heat shock protein-related genes expression in Channa argus. Chemosphere. 2020;261:127714. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B, Halperin T, Hruskova-Heidingsfeldova O, Adam Z, Clarke AK. Characterization of chloroplast Clp proteins in Arabidopsis: localization, tissue specificity and stress responses. Physiol Plant. 2002;114(1):92–101. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1140113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuehlke A, Johnson JL. Hsp90 and co-chaperones twist the functions of diverse client proteins. Biopolymers. 2010;93(3):211–217. doi: 10.1002/bip.21292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Żwirowski S, Kłosowska A, Obuchowski I, Nillegoda NB, Piróg A, Ziętkiewicz S, Bukau B, Mogk A, Liberek K. Hsp70 displaces small heat shock proteins from aggregates to initiate protein refolding. EMBO J. 2017;36(6):783–796. doi: 10.15252/embj.201593378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]