Abstract

In a ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO)-deficient mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides, strain 16PHC, nitrogenase activity was derepressed in the presence of ammonia under photoheterotrophic growth conditions. Previous studies also showed that reintroduction of a functional RubisCO and Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) pathway suppressed the deregulation of nitrogenase synthesis in this strain. In this study, the derepression of nitrogenase synthesis in the presence of ammonia in strain 16PHC was further explored by using a glnB::lacZ fusion, since the product of the glnB gene is known to have a negative effect on ammonia-regulated nif control. It was found that glnB expression was repressed in strain 16PHC under photoheterotrophic growth conditions with either ammonia or glutamate as the nitrogen source; glutamine synthetase (GS) levels were also affected in this strain. However, when cells regained a functional CBB pathway by trans complementation of the deleted genes, wild-type levels of GS and glnB expression were restored. Furthermore, a glnB-like gene, glnK, was isolated from this organism, and its expression was found to be under tight nitrogen control in the wild type. Surprisingly, glnK expression was found to be derepressed in strain 16PHC under photoheterotrophic conditions in the presence of ammonia.

Strain 16 of the nonsulfur purple photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides, a ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (RubisCO)-deficient mutant, is devoid of a functional Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) reductive pentose pathway (10). Under photoheterotrophic growth conditions, the CBB pathway is normally employed to balance the redox potential of the cell, with CO2 serving as the major electron sink (25, 35). Thus, an alternative electron acceptor, such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), is required for photoheterotrophic growth of strain 16 in order to dispose of excess reducing equivalents generated from carbon (malate in this case) photometabolism (25, 35). However, strain 16PHC, a spontaneous mutant derived from strain 16, exhibits the ability to grow under photoheterotrophic conditions without the addition of DMSO (35) and is believed to have developed an alternative redox balancing mechanism in the absence of the CBB pathway under photoheterotrophic growth conditions. This strain produces copious hydrogen gas when grown under these conditions. In this and similar CBB pathway-defective mutants derived from Rhodobacter capsulatus (26) and Rhodospirillum rubrum (19), derepression of nitrogenase synthesis was observed, even though high concentrations of extracellular ammonia were present (19, 28). Therefore, it is believed that the reduction of protons by the nitrogenase enzyme complex under photoheterotrophic conditions in the presence of ammonia serves as an alternative redox-balancing mechanism in strain 16PHC. The acquisition of the capacity for hydrogen evolution presumably renders this strain capable of photoheterotrophic growth in the absence of a functional CBB pathway and precludes the need for exogenous electron acceptors, such as DMSO. It was recently established (28) that the nif-encoded nitrogenase, and probably not alternative nitrogenases, is required for optimal photoheterotrophic growth of strain 16PHC. Moreover, nifH transcription was only partially derepressed in strain 16PHC in the presence of ammonia, with deregulation suppressed when cells regained a functional CBB pathway after trans complementation of the missing cbb genes. These results suggest that the mutation in strain 16PHC is of a regulatory nature and has a pleiotropic effect on cellular metabolism. It is thus proposed that there is a molecular link between the cbb and nif systems and that the mutation in strain 16PHC might affect the nitrogen-regulatory cascade (28).

The PII protein, the product of the glnB gene, plays a central role in the signal transduction cascade of nitrogen-regulatory systems in prokaryotes (9, 15, 17, 20). In Escherichia coli, signals influencing the cellular N status are transmitted through the PII-adenylyltransferase-glutamine synthetase pathway to rapidly influence glutamine synthetase (GS) enzyme activity by adenylylation or deadenylylation of the protein (9). In addition, the PII-NtrBC cascade regulates the synthesis of GS (reference 34 and references therein). In some diazotrophic organisms, signal transduction through PII could also be demonstrated at the level of nif transcription. However, in Azospirillum brasilense, a glnB null mutation caused a Nif− phenotype (7, 22), while in Rhizobium leguminosarum, a glnB mutation did not seem to have any effect on nif expression yet the ntr system was influenced (1). In another purple nonsulfur photosynthetic bacterium, R. capsulatus, an organism closely related to R. sphaeroides, point mutations in the glnB gene caused nif derepression in the presence of ammonia (Nifc phenotype) (21). A Nifc mutant was also reported for R. sphaeroides: it is caused by a mutation in the glnA gene, which forms an operon and is cotranscribed with glnB (39), as in many other nitrogen-fixing organisms (1, 7, 18, 21).

Previous studies of the R. sphaeroides glnBA operon led to the proposal that there is only one ς70 promoter (39) in the glnB promoter region; this is unlike the situation in R. capsulatus (13) and Rhodospirillum rubrum (18), where there are two promoters upstream of the glnB coding region which are thought to be differentially regulated according to the cellular N status. Sequence analysis also suggested that glnA might be cotranscribed with glnB in R. sphaeroides (39). However, there is no direct evidence as to whether glnB expression is controlled by the nitrogen status of the cell or even if the expression of glnB is essential for normal cellular nitrogen regulation in R. sphaeroides. Because of the key role played by the PII protein in nitrogen regulation (9, 15, 17, 20), an R. sphaeroides glnB::lacZ transcriptional fusion was constructed to facilitate the analysis of glnB expression in R. sphaeroides strains grown with different nitrogen sources. It was apparent that glnB regulation in the wild type differed from that in the RubisCO-deficient strain 16PHC. In addition, a glnB homolog, glnK, was isolated from R. sphaeroides and was also shown to be differentially controlled in the wild type and strain 16PHC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

R. sphaeroides strains and growth conditions.

The R. sphaeroides strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Photoheterotrophic growth, with either 30 mM ammonia or 5 mM glutamate as the nitrogen source, was described previously (28).

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| R. sphaeroides strains | ||

| HR | Wild type | 36 |

| 16 | RubisCO double deletion mutant; PH−a | 10 |

| 16PHC | RubisCO double deletion mutant; PH+b | 35 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pVKD8 | Tcr; library clone of strain HR containing the glnAB region | This study |

| pUCD84.0E | Ampr; containing the 4.0-kb EcoRI fragment from pVKD8, harboring the glnB region | This study |

| pRK3D11 | Tcr; library clone of strain 16PHC containing the glnK region | This study |

| pUCEBg2.2 | Ampr; containing the 2.2-kb EcoRI-BglII fragment from pRK3D11, harboring the glnK region | This study |

| pHRPglnB | Gmr IncQ glnB::lacZ fusion plasmid | This study |

| pHRPglnK(HR) | Gmr IncQ glnK::lacZ fusion from strain HR | This study |

| pHRPglnK(PHC) | Gmr IncQ glnK::lacZ fusion from strain 16PHC | This study |

| pHRP309 | Gmr IncQ; vector for constructing lacZ transcription fusion | 27 |

| pJG106 | Tcr; cosmid library clone from strain HR containing the cbbII cluster | 14 |

PH−, unable to grow under photoheterotrophic conditions in the absence of DMSO; cbbLS cbbM mutant.

PH+, able to grow under photoheterotrophic conditions in the absence of DMSO; cbbLS ccbM mutant.

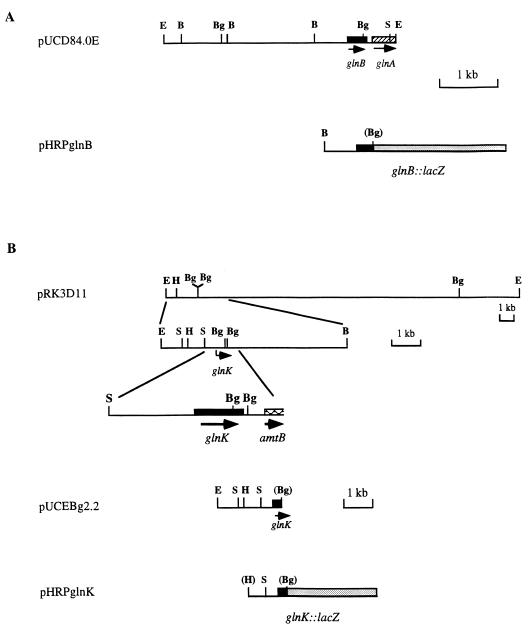

Cloning of glnB and construction of the glnB::lacZ transcriptional fusion.

Primers glnBF (5′ GAGGCGATCATCAAGCCGTTC 3′) and glnBR (5′ GCCGGTGCGGATGCGGATCGC 3′) were designed according to the previously published 5′ and 3′ nucleotide sequences of the glnB coding region of R. sphaeroides 2R (39). Subsequently, an approximately 340-bp glnB-specific PCR product synthesized by these two primers was used as a homologous probe to screen a genomic library of strain HR. The positively hybridizing library clone pVKD8 was isolated, and a 4.0-kb EcoRI fragment, containing the glnB region, was subcloned into pUC19 to generate pUCD84.0E (Fig. 1A). The 0.88-kb BamHI-BglII fragment containing the glnB upstream region and part of the glnB coding region was cloned into the low-copy-number IncQ vector pHRP309 to construct the glnB::lacZ transcriptional fusion plasmid pHRPglnB (Fig. 1A), which is compatible with IncP plasmid pJG106.

FIG. 1.

(A) Physical map and gene organization of the glnBA region of R. sphaeroides. Plasmid pUCD84.0E carries a 4.0-kb EcoRI fragment from cosmid pVKD8, which contains the glnBA region. The glnB::lacZ fusion plasmid pHRPglnB contains a 0.88-kb BamHI-BglII fragment from pUCD84.0E. (B) Cloning of the glnK region of R. sphaeroides and construction of a glnK::lacZ fusion. Plasmid pRK3D11 is the original library clone containing the glnK region from strain 16PHC. Plasmid pUCEBg2.2 contains the region upstream and includes part of glnK on a 2.2-kb EcoRI-BglII fragment. A 1.1-kb HindIII-BglII fragment from pUCEBg2.2 was used to construct a glnK::lacZ fusion [plasmid pHRPglnK(PHC)] from strain 16PHC. E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; Bg, BglII; S, SalI; B, BamHI. Restriction sites in parentheses were lost during cloning.

Cloning of glnK and construction of glnK::lacZ transcriptional fusions from strains HR and 16PHC.

When a genomic library of strain 16PHC (29) was examined with the same glnB probe, a library clone, pRK3D11, was found to hybridize to a moderate extent; this was subsequently isolated and shown to contain the glnK gene (Fig. 1B). A 2.2-kb EcoRI-BglII fragment was subcloned into pUC19 to generate pUCEBg2.2 (Fig. 1B), and the 1.1-kb HindIII-BglII fragment containing the glnK upstream region and part of the glnK coding region was cloned into pHRP309 to construct glnK::lacZ transcriptional fusion plasmid, pHRPglnK(PHC) (Fig. 1B). The same 1.1-kb HindIII-BglII fragment was also isolated from strain HR via PCR procedures, and a glnK::lacZ fusion plasmid, plasmid pHRPglnK(HR) (not shown), was similarly constructed from this strain.

Enzyme assays.

GS levels were determined by the γ-glutamyltransferase assay at pH 7.5 and 30°C with Mn2+ as the divalent cation, as previously described (16, 31) except that the reaction time was 15 min. This time was shown to be well within the linear time response for these assays. β-galactosidase activities were measured as previously described (28).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The sequences for the glnB and glnK regions from R. sphaeroides HR and 16PHC, respectively, have been submitted to the GenBank-EMBL data bank under accession no. AF032116 and AF023909, respectively.

RESULTS

glnBA operon from R. sphaeroides HR.

Nucleotide sequence analysis of the promoter and coding region of the glnB gene from R. sphaeroides HR showed 98.8% identity to the R. sphaeroides glnB sequence previously determined for a different strain, 2R (39) (accession no. X71659). When the deduced amino acid sequences were compared, 98.2% identity between these two sequences was found, with differences at only two residues; the amino acids at positions 50 and 81 in strain HR are glutamate and alanine, respectively, while in strain 2R they are alanine and serine, respectively. These differences are each due to a single base change. The Glu-50 and Ala-81 residues of the strain HR GlnB protein are conserved among other PII proteins and products of glnB-like genes, such as glnK of E. coli (33) and glnZ of A. brasilense (6). A putative NtrC-binding site, 5′ TGCACAAAAATCGGGCG 3′, located at nucleotides 443 to 459 in the glnB (strain HR) sequence, was also found at the same position upstream of the glnB coding region of strain 2R, with only one base pair difference (5′ TGCACAAAAATAGGGCG 3′) (39).

Expression of the glnB::lacZ fusion in R. sphaeroides.

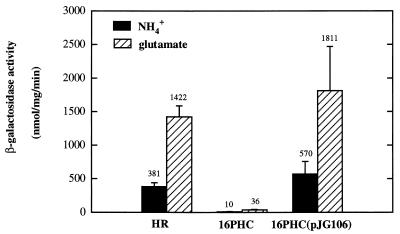

The glnB::lacZ fusion plasmid pHRPglnB was introduced into strains HR, 16PHC, and 16PHC(pJG106). Plasmid pJG106 contains an intact cbbM gene (encoding form II RubisCO), which allows the CBB pathway to be complete in strain 16PHC (14). In the wild-type strain, HR, a high level of glnB::lacZ expression was obtained when ammonia was used as the nitrogen source (Fig. 2), but a further threefold increase was observed under glutamate growth conditions. Thus, glnB transcription appears to be somewhat constitutive in this organism, although there is still a modicum of nitrogen control, which is similar to results reported for R. capsulatus (13) and Rhodospirillum rubrum (18); however, another glnB::lacZ fusion study indicated that glnB expression is constitutive in R. capsulatus (4). In strain 16PHC, glnB expression was extremely low when either ammonia or glutamate was used as the nitrogen source, although there was some indication of nitrogen control even at these low levels of activity. Interestingly, for strain 16PHC(pJG106), which regained a functional CBB pathway, glnB::lacZ expression was restored to wild-type levels (or slightly higher) under both ammonia and glutamate growth conditions. These results indicate that glnB expression was repressed (or not activated) in strain 16PHC and that the presence of a functional CBB pathway suppresses this effect and restores glnB expression to the level observed in the wild type.

FIG. 2.

glnB::lacZ fusion expression in different strains of R. sphaeroides. Strains carrying the glnB::lacZ fusion plasmid pHRPglnB were grown to mid-log phase under photoheterotrophic conditions with either ammonia or glutamate as the nitrogen source. Cells were harvested, and crude cell extracts were used for β-galactosidase activity measurements. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars. Numbers above bars are the means.

Levels of GS in R. sphaeroides.

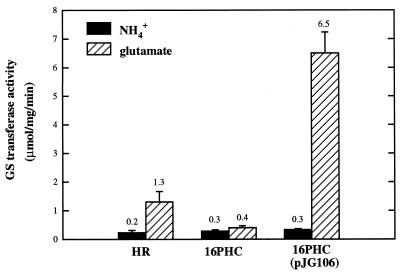

Since there is evidence indicating that glnA is most likely cotranscribed with glnB in R. sphaeroides (39), GS levels were examined in the different R. sphaeroides strains. In the wild-type strain, HR, the levels of GS were lower in the presence of ammonia, with a fivefold increase observed when glutamate was used as the nitrogen source (Fig. 3). These results parallel the glnB expression pattern observed for the wild-type strain. However, for strain 16PHC, although the levels of GS were comparable to that for strain HR in the presence of ammonia, GS activity did not increase further under glutamate growth conditions. When plasmid pJG106 was introduced into strain 16PHC, high levels of GS activity were obtained when glutamate was used as the nitrogen source for growth. Since the genes glnB and glnA (encoding GS) are cotranscribed in R. sphaeroides (39) and glnB is not expressed in the absence of a functional CBB pathway (Fig. 2), it is possible that glnA expression was affected under N-limiting conditions in strain 16PHC. Lower derepression levels of GS activity in glutamate-grown cells were also observed in CBB pathway-deficient strains of R. capsulatus and Rhodospirillum rubrum than in their wild-type CBB pathway-positive parent strains (data not shown). Immunoblot analysis with antisera raised against Rhodospirillum rubrum PII protein (17) and GS did not yield good cross-reactivity with R. sphaeroides crude cell extracts.

FIG. 3.

Levels of GS activity in different strains of R. sphaeroides. Cells grown with either ammonia or glutamate were harvested at mid-log phase, and GS levels were determined by measuring the transferase activity. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars. Numbers above bars are the means.

Sequence of the glnK gene from R. sphaeroides.

During the cloning of the glnBA cluster from R. sphaeroides, a glnB-like gene, glnK, was isolated from a genomic library of strain 16PHC. The gene showed similarity to the deduced sequences of glnB and glnB-like genes from various organisms. The deduced amino acid sequence of R. sphaeroides GlnK showed 64% identity with GlnZ from A. brasilense (6); 62% identity with GlnB from R. sphaeroides (strain HR [this study]), Klebsiella pneumoniae (15), and E. coli (23); 60% identity with GlnB from Herbaspirillum seropedicae (3) and Rhizobium meliloti (2); 59% identity with GlnB from A. brasilense (8) and Rhodospirillum rubrum (18); 58% identity with GlnB from Rhizobium leguminosarum (1) and Bradyrhizobium japonicum (24); 57% identity with GlnB from R. capsulatus (21); 53% identity with GlnB from Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942 (32); only 52% identity with GlnK from E. coli (33); and 50% identity with GlnB from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (19a). In all cases, tyrosine 51, previously shown to be the uridylylation site under nitrogen-limiting conditions, is conserved. A partial open reading frame downstream of glnK was also identified (Fig. 1B); it is very similar to a gene proposed to encode an ammonia transporter (37), amtB, of E. coli, in which it is also located downstream from the glnK gene.

A putative NtrC-binding site (5′ TGCATTAAAATTGGGCG 3′) was found upstream of the glnK coding region; it is similar to the NtrC-binding sites of the Rhodospirillum rubrum (18) and R. sphaeroides glnB regions (data not shown) but not very similar to the glnB region of R. capsulatus (13). Two sets of direct repeats, the functions of which are unknown, were also found. Neither an upstream activator sequence nor a −12/−24-type promoter, both of which are found in the nifH promoter regions of R. sphaeroides (28) and R. capsulatus (37), was observed in the glnK promoter region of R. sphaeroides.

Expression of glnK::lacZ fusions in R. sphaeroides.

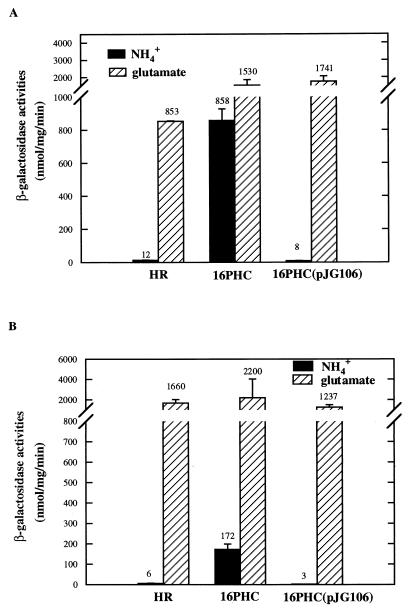

glnK::lacZ transcription fusions were constructed from DNA fragments isolated from strains HR and 16PHC, and the expression levels were examined. In strain HR, a very low level of glnK expression was observed in the presence of ammonia, and it was highly derepressed when glutamate was used as the nitrogen source under nitrogen-limiting growth conditions (Fig. 4A). These results indicated that glnK expression is under tight nitrogen control in wild-type R. sphaeroides, much like nifH expression (28). In strain 16PHC, this tight nitrogen control was abolished and there was a significant level of glnK derepression in the presence of ammonia. Although this depression was significant, the level of glnK expression did not reach the levels attained in this strain under glutamate growth conditions. Strain 16PHC(pJG106), which possesses a functional CBB pathway, suppressed the derepression of glnK expression that was observed in strain 16PHC in the presence of ammonia. Moreover, with glutamate as the nitrogen source, high levels of glnK expression were achieved, even somewhat higher than in the wild type. The fusion plasmid pHRPglnK(PHC), which was constructed from sequences derived from strain 16PHC, yielded approximately the same pattern of gene expression (Fig. 4B), the only difference being a lower level of derepression in strain 16PHC in the presence of ammonia than that with plasmid pHRPglnK(HR). Nevertheless, it is unlikely that the derepression of glnK was caused by a cis mutation in the glnK promoter region in strain 16PHC, since glnK::lacZ fusions from both strains yielded similar results. These findings were quite similar to the pattern of nifH expression in R. sphaeroides strains (28).

FIG. 4.

glnK::lacZ fusion activities in R. sphaeroides HR, 16PHC, and 16PHC(pJG106). Strains carrying glnK::lacZ fusion plasmids pHRPglnK(HR) (A) and pHRPglnK(PHC) (B) were grown photoheterotrophically with ammonia or glutamate as the nitrogen source. Cells were harvested at mid-log phase, and β-galactosidase activities were measured. Standard deviations are indicated by error bars. Numbers above bars are the means.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies demonstrated that nitrogenase derepression occurs when the RubisCO-deficient strain 16PHC is grown in the presence of ammonia, with nitrogenase presumably serving to substitute for the CBB pathway as the means of achieving redox balancing under photoheterotrophic growth conditions (19). The Nifc phenotype of strain 16PHC is unique in that nitrogenase synthesis is only partially derepressed; however, derepression is reversible and suppressed when a functional CBB pathway is introduced by the addition of a RubisCO gene in trans. This suggests that the mutation that caused nif derepression is somehow linked to the nif regulatory system of R. sphaeroides, yet the basis of the Nifc phenotype is undoubtedly different from those of other, previously described Nifc mutants, which are unrelated to CBB function (21, 39, 40). Since a glnB mutation of R. capsulatus resulted in a Nifc phenotype and the PII protein had been previously proposed to be a negative regulator of nif regulation in this organism (20), we examined glnB expression in strain 16PHC. Our results clearly indicated that glnB expression was affected in strain 16PHC. Despite the fact that a previous study showed the presence of a ς70 promoter motif upstream of the glnB coding region in R. sphaeroides (39), glnB expression was nevertheless affected by the nitrogen source supplied to this organism; e.g., the high level of glnB expression found in cells grown in the presence of ammonia was increased threefold when glutamate was used as the nitrogen source. In R. sphaeroides 16PHC, however, there was little or no glnB::lacZ fusion activity when either ammonia or glutamate was used as the nitrogen source. Since it is possible that the PII protein might also function as a nif repressor in R. sphaeroides, the absence of glnB expression in strain 16PHC might lead to the derepression of nitrogenase synthesis in the presence of ammonia. However, repression of glnB expression was relieved by the introduction of a gene which yields a functional CBB pathway, leading to a concomitant suppression of nitrogenase synthesis in the presence of ammonia (19, 28). These results are compatible with a suggested role of a functional CBB pathway in nif expression in strain 16PHC, presumably via the activation and/or inactivation of PII protein synthesis.

It has been shown for many bacteria that the glnB and glnA genes are cotranscribed and are part of a two-gene operon controlled by a glnB promoter(s) (1, 13, 18, 24). Evidence that a third promoter might also be used to specifically regulate glnA expression has been presented (1, 7, 13, 18). In strain 16PHC, GS activity was extremely low and levels were comparable to those obtained from the wild-type strain, HR, in the presence of ammonia. This low, yet constitutive, level of GS activity in strain 16PHC is probably due to the existence of a glnA promoter which may not be controlled by the nitrogen source used for growth. The fact that GS activity is detected in the absence of glnB expression in strain 16PHC might explain why glutamine auxotrophy was not observed in this strain. Similar results were obtained for Rhizobium leguminosarum (1), in which a glnB mutation seemed to affect GS expression only under glutamate growth conditions. In the same study, a glnA::lacZ fusion which was not sensitive to the nitrogen source for growth was constructed. In addition, glnA::lacZ activities were not affected by a glnB mutation. It is thus reasonable to believe that in R. sphaeroides, like Rhizobium leguminosarum, if transcription from a glnB promoter(s) is not possible, glnA may be transcribed from its own promoter, a promoter which is not regulated by the nitrogen source used for growth.

A glnB-like gene, glnK, was also isolated from R. sphaeroides, but glnK expression appeared to be controlled differently from glnB expression in that it was highly regulated by the nitrogen source used for growth. Indeed, glnK appeared to be expressed only under N-limiting growth conditions, e.g., with glutamate as the nitrogen source. Similar results were also obtained from studies of glnB-like genes from E. coli (33) and Bacillus subtilis (38), although the expression of the glnB-like gene glnZ in A. brasilense seemed to be insensitive to nitrogen sources (6). In strain 16PHC, this tight nitrogen control was lost and glnK expression was partially derepressed in the presence of ammonia, similar to nitrogenase synthesis in this strain, suggesting that perhaps nifH and glnK expression might have common regulatory elements. However, in a recent study (28), it was found that the same upstream activation and −12/−24-type promoter sequences that were present in the nifH promoter region did not appear to be present in the upstream region of glnK. Another fact to be considered in the future is that many organisms contain two different types of GS (e.g., in Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 [30] and Rhizobium leguminosarum [1]), which are differentially regulated by nitrogen availability. Why certain organisms possess two such different systems is unknown at this point; however, such findings might relate to potential efficient ways to control nitrogen metabolism under the widest possible range of environmental conditions. It should be noted that glnB-like genes have also been reported for H. seropedicae (3), B. subtilis (nrgB) (38), A. brasilense (glnZ) (6), and E. coli (glnK) (33). Although the syntheses of GlnB and GlnK are differentially regulated in R. sphaeroides, these two proteins are both predicted to be composed of 112 amino acids and have very similar sequences, including a conserved uridylylation site, Tyr-51. It has been shown that purified GlnK from E. coli (33) can activate adenylylation of GS in vitro in the presence of ammonia (even though GlnK is not synthesized under such conditions in vivo). GlnK can also be modified by uridylylation under nitrogen-limiting conditions in vivo, suggesting that GlnK, the PII homolog, might function similarly to the PII protein itself and interact with regulatory proteins in the cell. Therefore, it is possible that the GlnK protein, which is presumably synthesized in the presence of ammonia in strain 16PHC, takes on the role of the PII protein, which presumably is not synthesized in this strain. Thus, if GlnB acts as a negative regulator for nif derepression by binding NtrB, subsequently leading to dephosphorylation of NtrC-Pi, perhaps GlnK is not as efficient as GlnB in binding to NtrB. Perhaps, then, partial derepression of nitrogenase synthesis in the absence of PII is related to the efficiency of GlnK-NtrB binding and/or its relative influence on NtrC dephosphorylation. It appears that the Nifc phenotype of strain 16PHC is different from the phenotypes of other Nifc mutants, because the mutation in strain 16PHC caused a pleiotropic effect on gene expression, including the repression of glnB expression and derepression of glnK and nitrogenase synthesis in the presence of ammonia. It will thus be important to determine if glnK derepression in the presence of ammonia is caused by the absence of PII synthesis in strain 16PHC.

Although the control of nitrogen metabolism and the complicated regulatory cascade have been studied extensively for prokaryotes, our results indicate that carbon metabolism also plays a significant role in regulating nitrogen metabolism. It is apparent that the CBB pathway is linked to PII expression in strain 16PHC. A regulatory link between carbon metabolism and nitrogen metabolism is also suggested for the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942, in which the rate of CO2 fixation through the CBB pathway affects phosphorylation of the PII protein (11, 12). In cyanobacteria, modification by phosphorylation seemingly is the equivalent of uridylylation of the PII protein observed in other prokaryotes (5). The precise mechanism by which the CBB pathway affects gene expression and enzyme activity within the nitrogen assimilatory system remains to be determined. However, it seems apparent that further probing of the link between the two major biosynthetic processes of carbon assimilation and nitrogen assimilation will lead to definitive answers.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stefan Nordlund and Paul Ludden for the gifts of antisera to PII protein and GS, respectively.

This study was supported by Public Health Service grant GM45404 from the National Institutes of Health and by Department of Energy grant DE-FG02-91ER 20033.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amar M, Patriarca E J, Manco G, Bernard P, Riccio A, Lamberti A, Defez R, Iaccarino M. Regulation of nitrogen metabolism is altered in a glnB mutant strain of Rhizobium leguminosarum. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:685–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arcondéguy T, Huez I, Tillard P, Gangneux C, de Billy F, Gojon A, Truchet G, Kahn D. The Rhizobium meliloti PII protein, which controls bacterial nitrogen metabolism, affects alfalfa nodule development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1194–1206. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.9.1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benelli E M, Souza E M, Funayama S, Rigo L U, Pedrosa F O. Evidence for two possible glnB-type genes in Herbaspirillum seropedicae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4623–4626. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4623-4626.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borghese R, Wall J D. Regulation of the glnBA operon of Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4549–4552. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.15.4549-4552.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheah E, Carr P D, Suffolk P M, Vasudevan S G, Dixon N E, Ollis D L. Structure of the Escherichia coli signal transducing protein PII. Structure. 1994;2:981–990. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(94)00100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Zamaroczy M, Paquelin A, Peltre G, Forchhammer K, Elmerich C. Coexistence of two structurally similar but functionally different PII proteins in Azospirillum brasilense. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4143–4149. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4143-4149.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Zamaroczy M, Paquelin A, Elmerich C. Functional organization of the glnB-glnA cluster of Azospirillum brasilense. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:2507–2515. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.9.2507-2515.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Zamaroczy M, Delorme F, Elmerich C. Characterization of three different nitrogen-regulated promoter regions for the expression of glnB and glnA in Azospirillum brasilense. Mol Gen Genet. 1990;224:421–430. doi: 10.1007/BF00262437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engleman E G, Francis S H. Cascade control of E. coli glutamine synthetase. II. Metabolite regulation of the enzymes in the cascade. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1978;191:602–612. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(78)90398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Falcone D L, Tabita F R. Expression of endogenous and foreign ribulose 1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase (RubisCO) genes in a RubisCO deletion mutant of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2099–2108. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.6.2099-2108.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forchhammer K, Tandeau de Marsac N. Phosphorylation of the PII protein (glnB gene product) in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942: analysis of in vitro kinase activity. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5812–5817. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.20.5812-5817.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forchhammer K, Tandeau de Marsac N. Functional analysis of the phosphoprotein PII (glnB gene product) in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. strain PCC 7942. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2033–2040. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.8.2033-2040.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foster-Hartnett D, Kranz R G. The Rhodobacter capsulatus glnB gene is regulated by NtrC at tandem rpoN-independent promoters. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:5171–5176. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.16.5171-5176.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibson J L, Tabita F R. Localization and mapping of CO2 fixation genes within two gene clusters in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:2153–2158. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.5.2153-2158.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holtel A, Merrick M. Identification of the Klebsiella pneumoniae glnB gene: nucleotide sequence of wild-type and mutant alleles. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;215:134–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00331314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johansson B C, Gest H. Adenylylation/deadenylylation control of the glutamine synthetase of Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. Eur J Biochem. 1977;81:365–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johansson M, Nordlund S. Uridylylation of the PII protein in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4190–4194. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4190-4194.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johansson M, Nordlund S. Transcription of the glnB and glnA genes in the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodospirillum rubrum. Microbiology. 1996;142:1265–1272. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joshi H M, Tabita F R. A global two component signal transduction system that integrates the control of photosynthesis, carbon dioxide assimilation, and nitrogen fixation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14515–14520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19a.Kaneko T, Sato S, Kotani H, Tanaka A, Asamizu E, Nakamura Y, Miyajima N, Hirosawa M, Sigiura M, Sasamoto S, Kimura T, Hosouchi T, Matsuno A, Muraki A, Nakazaki N, Naruo K, Okumura S, Shimpo S, Takeuchi C, Wada T, Watanabe A, Yamada M, Yasuda M, Tabata S. Sequence analysis of the genome of the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC6803. II. Sequence determination of the entire genome and assignment of potential protein-coding regions. DNA Res. 1996;3:109–136. doi: 10.1093/dnares/3.3.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kranz R G, Cullen P J. Regulation of nitrogen fixation. In: Blankenship R E, Madigan M T, Bauer C E, editors. Anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1995. pp. 1191–1208. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kranz R G, Pace V M, Caldicott I M. Inactivation, sequence, and lacZ fusion analysis of a regulatory locus required for repression of nitrogen fixation genes in Rhodobacter capsulatus. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:53–62. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.1.53-62.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liang Y Y, de Zamaroczy M, Arsène F, Paquelin A, Elmerich C. Regulation of nitrogen fixation in Azospirillum brasilense Sp7: involvement of nifA, glnA and glnB gene products. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;100:113–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb14028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J, Magasanik B. The glnB region of the Escherichia coli chromosome. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:7441–7449. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.22.7441-7449.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin G B, Thomashow M F, Chelm B K. Bradyrhizobium japonicum glnB, a putative nitrogen-regulatory gene, is regulated by NtrC at tandem promoters. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:5638–5645. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.10.5638-5645.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McEwan A G. Photosynthetic electron transport and anaerobic metabolism in purple non-sulfur phototrophic bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1994;66:151–164. doi: 10.1007/BF00871637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paoli G P. Ph.D. dissertation. Columbus: The Ohio State University; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parales R E, Harwood C S. Construction and use of a new broad-host-range lacZ transcriptional fusion vector, pHRP309, for Gram− bacteria. Gene. 1993;133:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90220-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qian Y. Ph.D. dissertation. Columbus: The Ohio State University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian Y, Tabita F R. A global signal transduction system regulates aerobic and anaerobic CO2 fixation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:12–18. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.1.12-18.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reyes J C, Muro-Pastor M I, Florencio F J. Transcription of glutamine synthetase genes (glnA and glnN) from the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 is differently regulated in response to nitrogen availability. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2678–2689. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.8.2678-2689.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shapiro B M, Stadtman E R. Glutamine synthetase (Escherichia coli) Methods Enzymol. 1970;17A:910–922. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(85)13032-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsinoremas N F, Castets A M, Harrison M A, Allen J F, Tandeau de Marsac N. Photosynthetic electron transport controls nitrogen assimilation in cyanobacteria by means of posttranslational modification of the glnB gene product. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4565–4569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Heeswijk W C, Hoving S, Molenaar D, Stegeman B, Kahn D, Westerhoff H V. An alternative PII protein in the regulation of glutamine synthetase in E. coli. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:133–146. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6281349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Heeswijk W C, Rabenberg M, Westerhoff H V, Kahn D. The genes of the glutamine synthetase adenylylation cascade are not regulated by nitrogen in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1993;9:443–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang X, Falcone D L, Tabita F R. Reductive pentose phosphate-independent CO2 fixation in Rhodobacter sphaeroides and evidence that ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase activity serves to maintain the redox balance of the cell. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3372–3379. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.11.3372-3379.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weaver K E, Tabita F R. Isolation and partial characterization of Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides mutants defective in the regulation of ribulose bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:507–515. doi: 10.1128/jb.156.2.507-515.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Willison J C, Pierrard J, Hubner P. Sequence and transcript analysis of the nitrogenase structure gene operon (nifHDK) of Rhodobacter capsulatus: evidence for intramolecular processing of nifHDK mRNA. Gene. 1993;133:39–46. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90222-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wray L V, Jr, Atkinson M R, Fisher S H. The nitrogen-regulated Bacillus subtilis nrgAB operon encodes a membrane protein and a protein highly similar to the Escherichia coli glnB-encoded PII protein. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:108–114. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.1.108-114.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zinchenko V, Churin Y, Shestopalov V, Shestakov S. Nucleotide sequence and characterization of the Rhodobacter sphaeroides glnB and glnA genes. Microbiology. 1994;140:2143–2151. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zinchenko V V, Kopteva A V, Belavina N V, Mitronova T N, Frolova V D, Shestakov S V. A study of different types of Rhodobacter sphaeroides mutants with derepression of nitrogenase. Sov Genet. 1991;27:695–702. [Google Scholar]